Alireza Karimi Moghaddam, Charles B. Wordsmith, TUTU, John Sephton, Kevin Morris, Seth, Artur Zienko, Andrea Mbarushimana, Piotr Jakubczak, Michał Zabłocki Jarosław Krawczak, ChemiS, Krzysztof Łozowski, WOSKerski, Danylo Movchan, Agata Dębicka, Agnieszka Traczyńska, KAWU, Iwona Siwek-Front, Parvati, Yaryna Movchan, Allan Murrell, Agnieszka Litwin, Ola Haydamaka, Maximiliano Bagnasco, Pieksa, Seth Globepainter, MyDogSighs, Paweł Wąsowicz, Yurii Ivantsyk, JenksArt, Christian Guémy, SEF, John D’oh, Voytek Glinkowski, Ilya Kaminsky, Juliusz Wątroba, George Wright, Maggie Hall, Bogna Jarzemska-Misztalska, Muhammad Khurram Salim, Krzysztof Wiśniewski, Radek Ruciński, Tatiana Averina, Piotr Kamieniarz, Renata Cygan, Matthew Dover, Katarzyna Zygadlewicz, Marcin Zegadło Ula Dzwonik, Julija Musakowska, , Ija Kiwa, Anna Ponomarenko, Elżbieta Isakiewicz, Ryszard Kupidura, Ołeksandr Kłymenko, Aleksey Kislow Joanna Nordyńska, Karol Maliszewski, Paweł Kuczyński, Ewa Klonowska, Haśka Szyjan, Ted Smith Orr, Ann Lovelace, Maggie Hall, Loraine Saacks, Nick Alldridge, Robin Pilcher, Kateryna Michalicyna

SPECIAL

POST SCRIPTUM INDEPENDENT MAGAZINE OF LITERATURE & THE ARTS PROSE POETRY VISUAL ARTS ARTICLES INTERVIEWS 4 / 2022 (18)

EDITION

www.postscriptum.uk www.postscriptumfundacja.com fb: post scriptum

CONTENT:

Marcin

Dzwonik

Krzysztof Łozowski

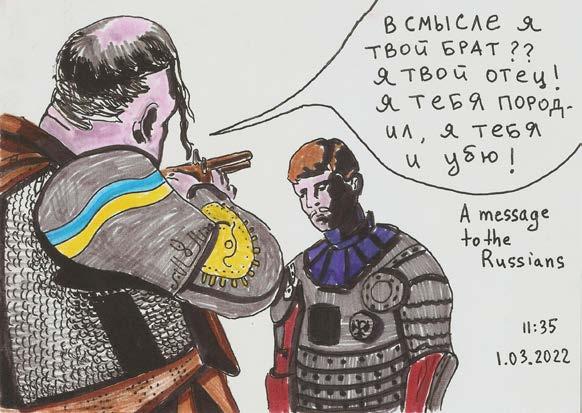

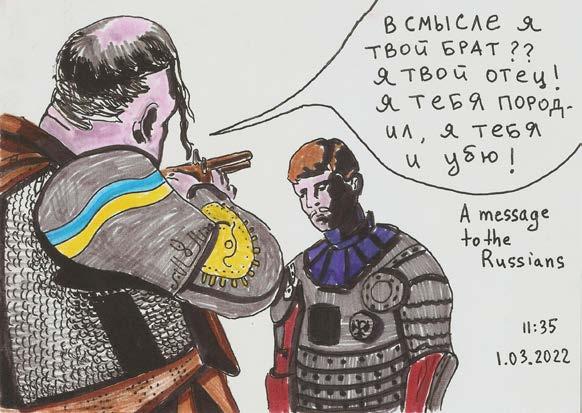

Krzysztof Łozowski – drawings

John Sephton, Kevin Morris – poetry

Andrea Mbarushimana – poetry

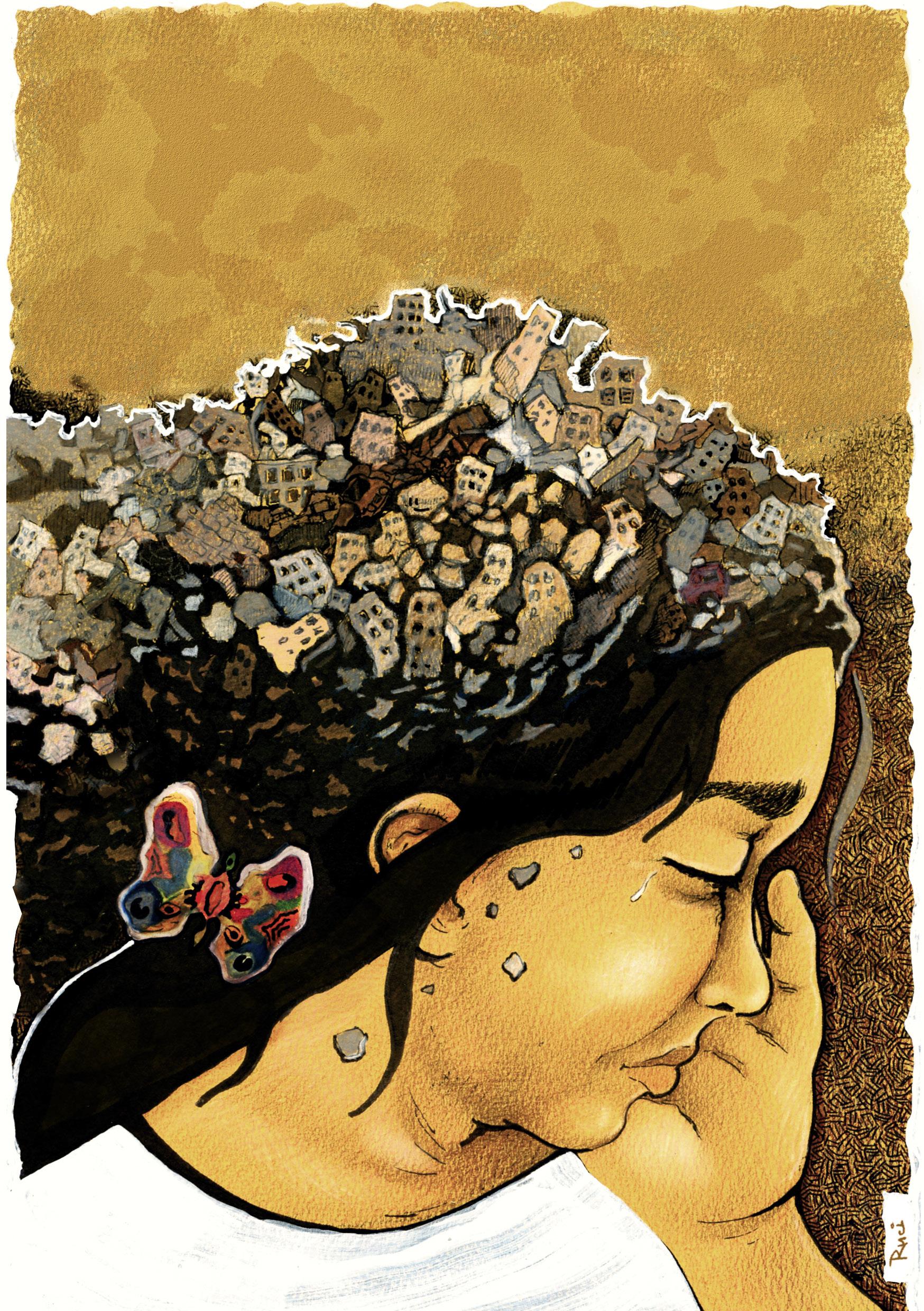

Paweł Wąsowicz – illustration “Hope”

Danylo Movchan – paintings, interview

Michał Zabłocki – poetry

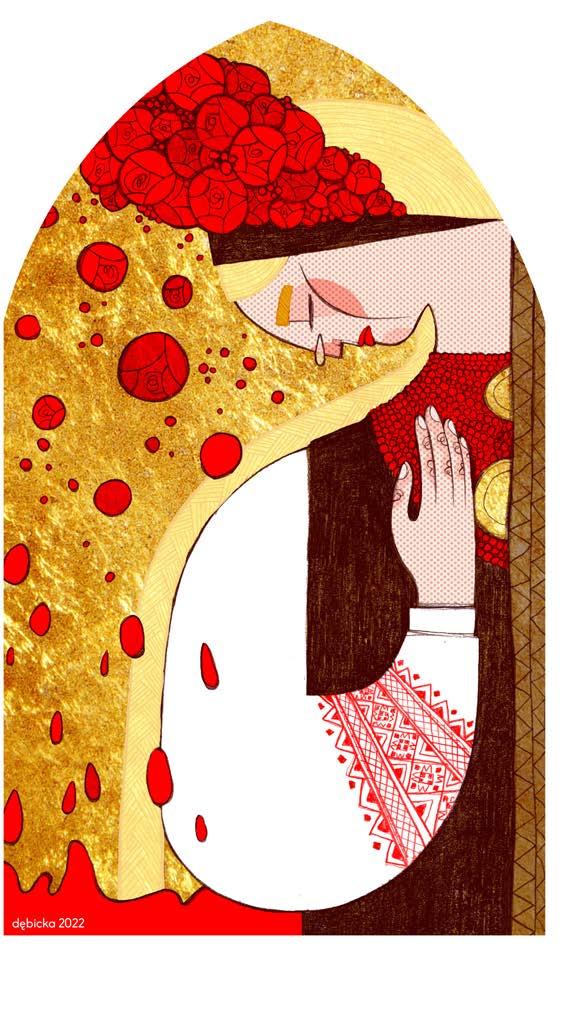

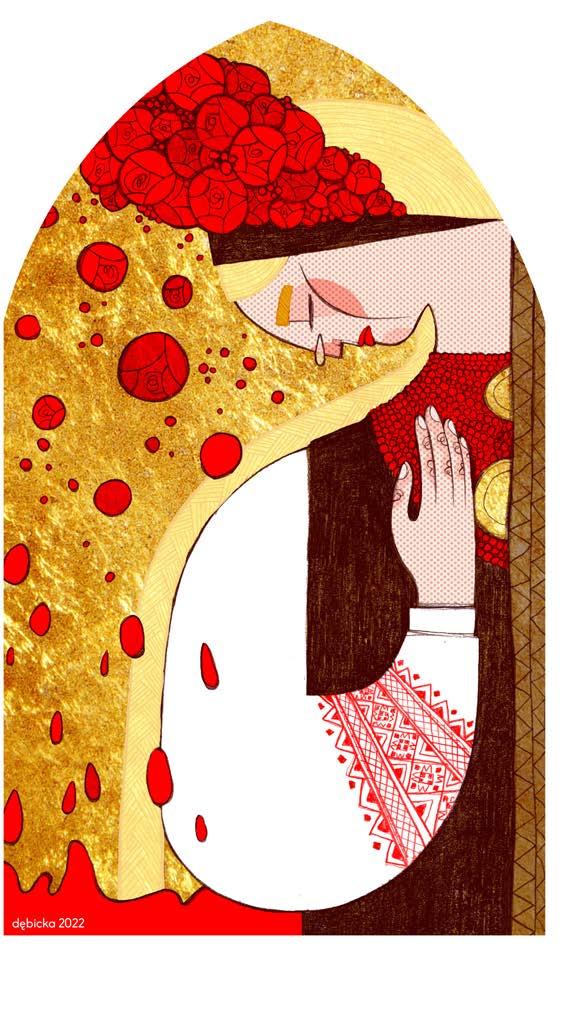

Agata Dębicka – illustrations

Juliusz Watroba – people to People (?)

Paweł Kuczyński – illustrations

Haśka Szyjan (Ukraine) – poetry

Kateryna Michalicyna (Ukraine) – poetry

Street Art – graffiti artists from all over the world for Ukraine

Allan Murrell – poetry

Radosław Ruciński – painting

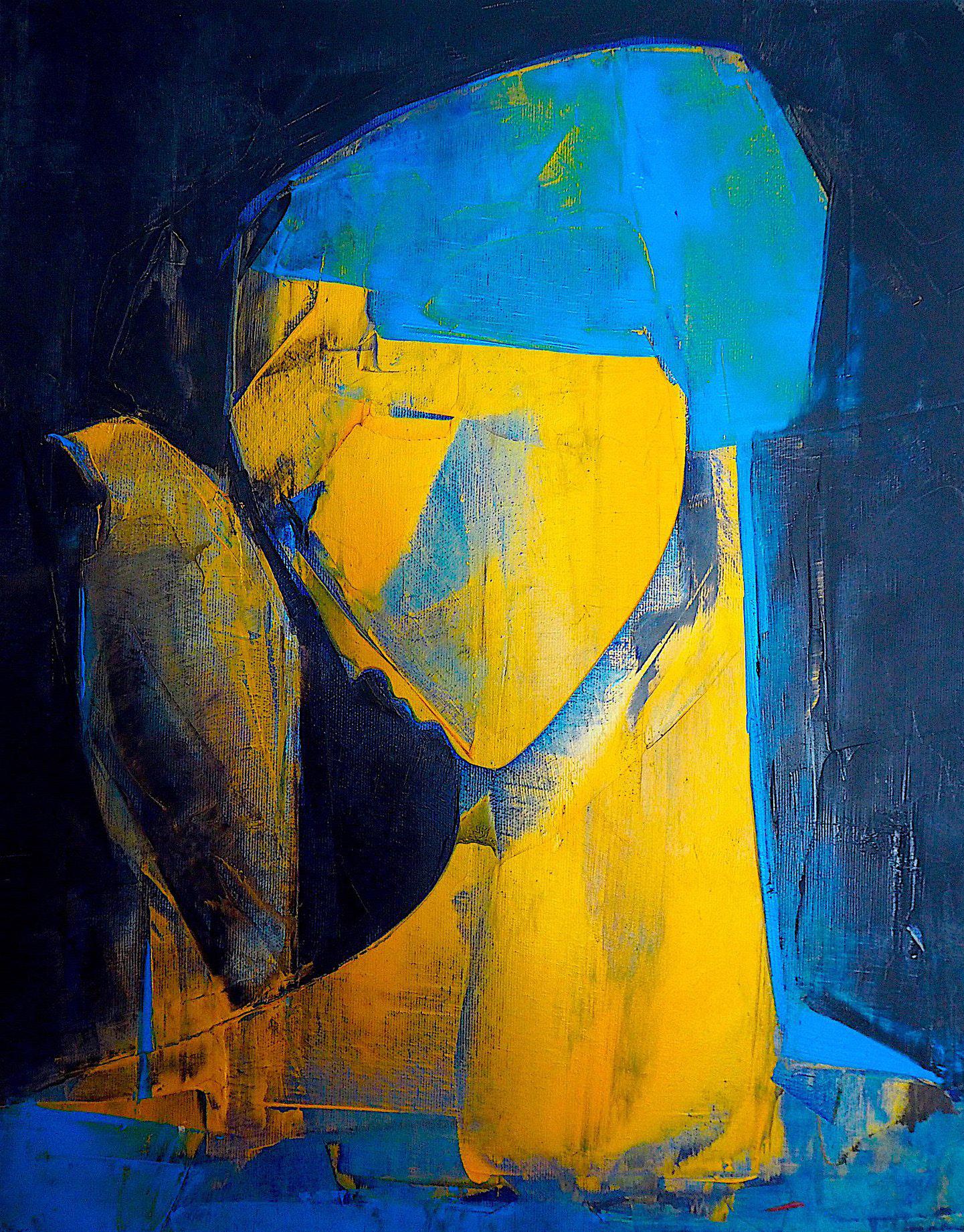

Voytek Glinkowski – painting “Conqueror”

Ilya Kaminski – essay

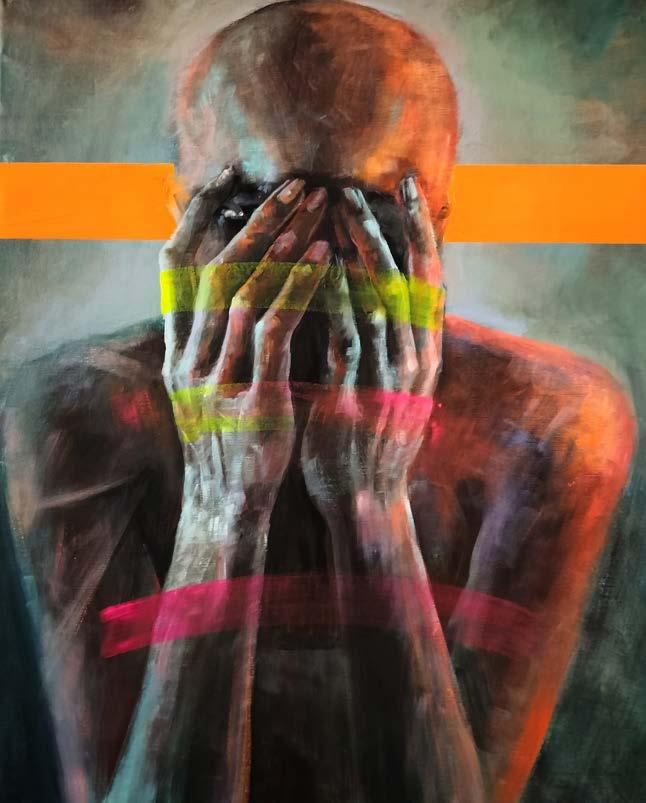

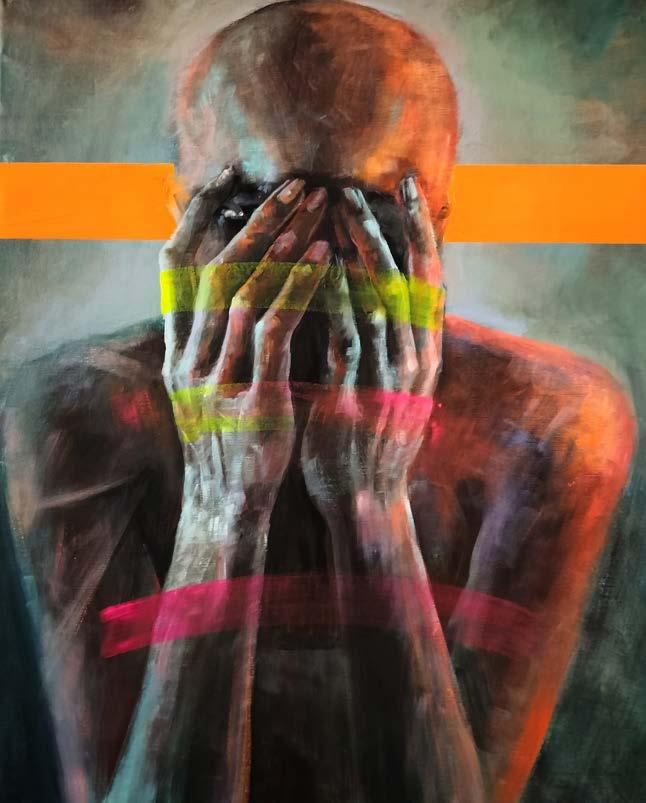

Piotr Kamieniarz – painting “In the Cage”

George Wright – poetry

Tatiana Averina (Ukraine) – photography

Bogna Jarzemska-Misztalska – painting “Three Wishes”

Maggie Hall – poetry

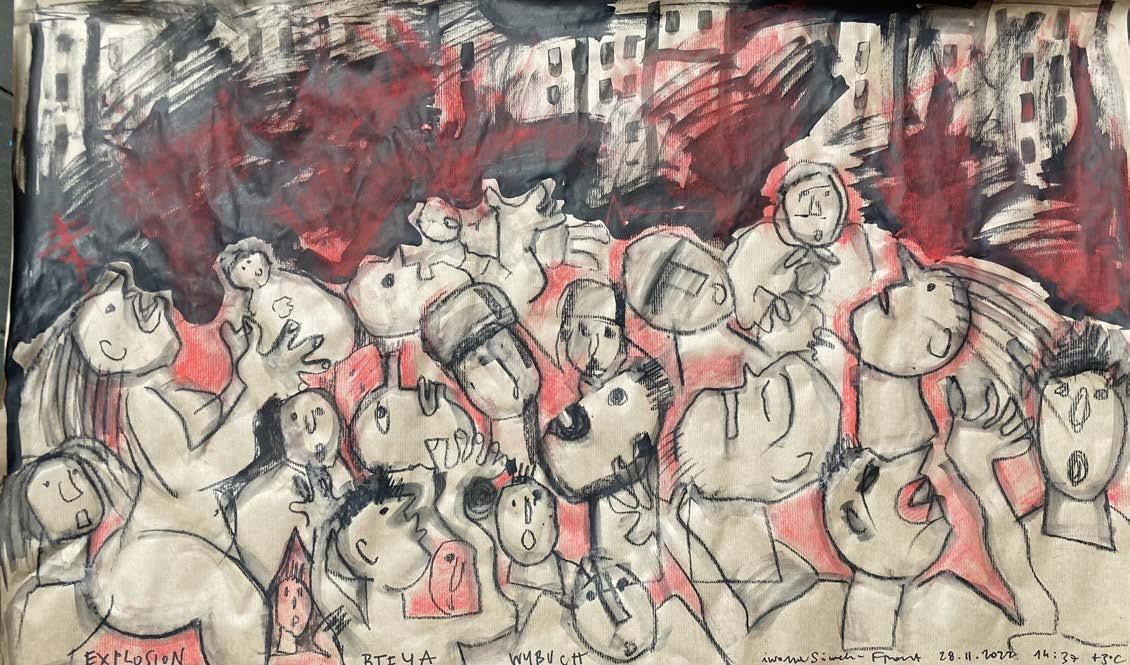

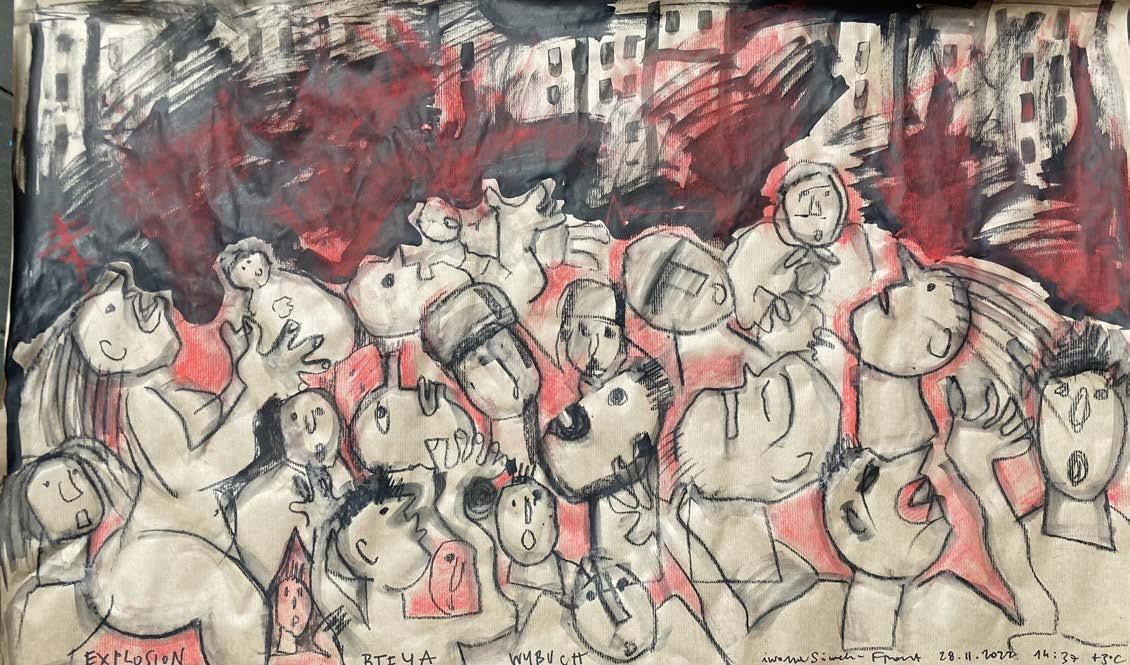

Iwona Siwek-Font – “Exodus” - paintings

Ewa Klonowska – painting “Exodus”

Muhammad Khurram Salim – poetry

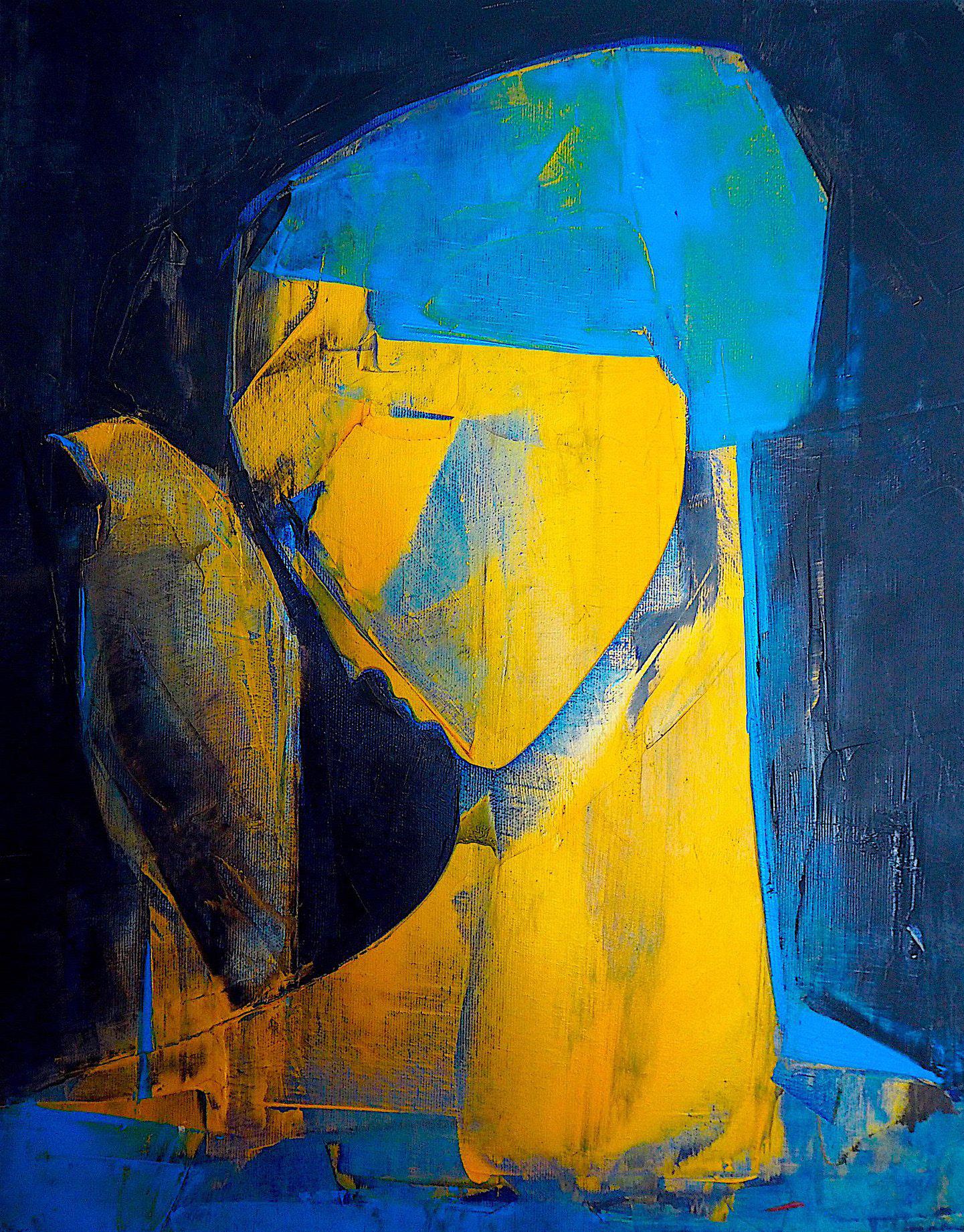

Artur Zienko – paintings

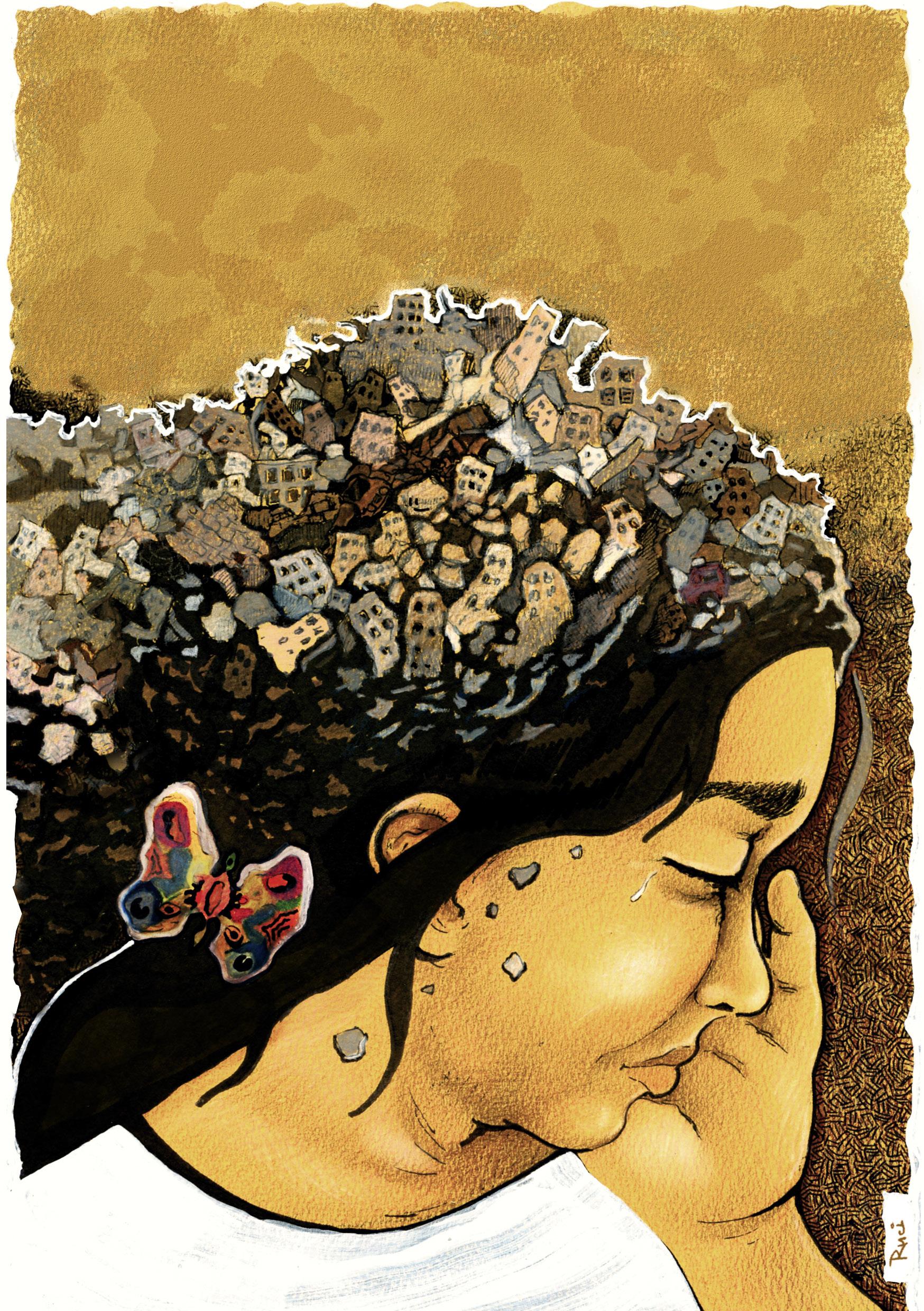

Alireza Karimi Moghaddam (Iran) – paintings

Loraine Saacks – poetry

Matthew Dover – Illustrations

Yaryna Movchan (Ukraine) – paintings

Anna Ponomarenko (Ukraine) – paintings

Ryszard Kupidura – essay

Katarzyna Zygadlewicz – painting

Nick Alldridge – poetry

Piotr Jakubczak – “War” – paintings

Robin Pilcher – poetry

Agnieszka Traczyńska – paintings

Radek Ruciński – painting

Elżbieta Isakiewicz – fragment of book

Agnieszka Litwin – illustration

Ted Smith Orr – poetry

Yurii Ivantsyk (Ukraina) – illustrations

Ann Lovelace – poetry

Jarosław Krawczak – photography

Joanna Nordyńska – Passers by – essay

Krzysztof Wiśniewski, Ola Haydamaka - paintings

EDITORIAL TEAM :

PRINT ON DEMAND: 24,95 zł

https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/ read/67230303/post-scriptum-4-2022-18-spe cial-edition-ukraine-eng https://www.wyczerpane.pl/wy dawnictwo-post-scriptum,dBA-0io.html

MEDIALNI

Renata Cygan (Editor-in-Chief), Katarzyna Brus-Sawczuk (deputy editor), Joanna Nordyńska (deputy editor), Juliusz Wątroba, Anna Maruszeczko, Izolda Kiec, Wanda Dusia-Stańczak, Renata Szpunar, Robert Knapik, Iza Smolarek, Alex Sławiński, Paweł Krupka.

Guest appearances: Ryszard Kupidura, Ilya Kaminski, Maria Karwowska, Marcin Zegadło, Elżbieta Isakiewicz

Proof readers: Liz Draper, Andrea McDowell, Arco Van Ieperen, Benjamin Becula, Monika Cygan, Ania Cygan

Translations from Polish language: Renata Cygan, Olga Sawczuk, Arco Van Ieperen, Katarzyna Krawiecka, Monika Cygan, Ania Cygan Composition and graphic design: Renata Cygan

ORDERS: PARTNERZY

https://issuu.com/post.scriptum/docs/post_scrip tum_4_2022_18_special_edition_ukraine_en FREE ELECTRONIC VERSION: 4. Charles B. Wordsmith – poetry 5. Piotr Jakubczak – painting “Golgota” 6.

Zegadło – 2 essays 6. Ula

– paintings 8.

– painting “Water” 10.

11.

12.

13.

15.

22.

23.

24.

26.

28.

29.

30.

48.

49.

50.

52.

55.

56.

58.

60.

61.

62.

66.

67.

68.

70.

72.

73.

74.

78.

80.

81.

83.

84.

86.

88.

90.

91.

91.

92.

94.

96.

97.

98.

110.

„You should praise the crippled world” - Adam Zagajewski

In the March issue of Post Scriptum, we devoted a lot of space to topics that arose as a re sult of war circumstances. Artists from all over the world, in a gesture of solidarity with the fighting Ukraine, rebel against the unjustified, criminal aggression of Putin’s Russia, against the senseless shedding of blood and give vent to their emotions by creating works of art, whether as a sign of protest against the war or as a material form for helping fighters and victims. We are talking about a new art of humanism, which is to help discover the truth about ourselves, stimulate reflection, but most of all cause a change in our way of thinking.

In most cases, these works are earmarked for auctions, the profits of which are donated to people affected by the war.

We received a lot of materials from all over the world, so there was a need to create this special, historical edition, which has been already published in Polish and now we are pre senting the English version. War is a time of trial and truth – hearts grow when we see so many people of good will, when we pass the test of humanity in various ways. Together we have the power! Every form of protest, every brick of help, brotherhood and spiritual sup port unites us, creating a strong voice against aggression and hatred. Ukraine is not alone, and we express this also in the pages of Post Scriptum, because evil, harm and lies cannot be tolerated.

Why was this special issue created? Because it was worth collecting these wonderful works in one place to please our eyes and hearts and to cheer up the victims. People are losing homes, but they are not losing us. We are here to help them survive the war.

We present you an anti-war gallery of paintings, photographs, and murals, as well as a lot of strong, moving poems and prose. In both versions of the special edition, we have man aged to collect the works of almost one hundred artists from all over the world! The genre weight of this release, the enormity of its emotions and sensitivity of the creators are really impressive!

We contacted graffiti artists – including those from the most distant corners of the planet (e.g., Argentina, Indonesia, America, Iran), who wear blue and yellow colors to show that we can still coexist beyond divisions in certain areas of life. We also invited many contempo rary Ukrainian artists, such as: Danylo Movchan, Haśka Szyjan, Kateryna Michalicyna, Chrys tia Wenhryniuk, Ija Kiwa, Ilya Kaminski, Tatiana Averina, Anna Ponomarenko, Yurii Ivantsyk, Yaryna Movchan. The power is with us!

Let me quote an extraordinary poetess Papusza: „I am coming so that you do not make the dark night in broad daylight”.

3POST SCRIPTUM Editor-in-Chief Publisher: Post Scriptum LTD, Watford, UK account number: IBAN: GB82 LOYD 3096 2657 4181 60 UK: SORT CODE: 309626 ACC Number: 57418160 Picture on the cover: Parvati EDITORIAL www.postscriptum.uk, fb: post scriptum, e-mail: redakcja@postscriptum.uk

ODE TO A RUSSIAN HOOLIGAN

Dedicated to Marina Ovsyannikova

Just another news broadcast

About Russia’s special military operation And then this crazy lady walks across the set, Carrying a banner, which reads ‘Don’t believe the propaganda, They’re Lying to you here’, Signed ‘Russians against the War’. ‘

What I wonder will the babushkas say In the ocheret to buy kalbaca, “She must be mentally unbalanced”, “Or maybe a stooge for those Ukrainian fascists”, “Surely our great leader Putin wouldn’t lie to us”. The babushka at the end of the line keeps silent. Her eighteen year old grandson Is currently sitting in a tank Outside the city of Kyiv.

“She’s just been fined, They should chuck her into prison and throw away the key, That’s what such traitors deserve”. Behind the sausage counter A young woman wraps up the meat For her rather disgruntled customers. She wants to tell them about the text Her boyfriend sent her, Showing pictures of bombed out buildings, People fleeing their homes, And how the Ukrainian soldier he captured, The same age as himself Wanted to know why Russia Seemed so intent On destroying and killing fellow Slavs.

She wants him home. They were going to get married in the summer, But who knows now, when, if ever, Her handsome groom will return. She wants to scream at the babushkas Don’t believe what the national state TV tells you. In Russia these days, the only people You can rely on to tell the truth Are those they call ‘hooligans’.

After all, who should really be thrown into prison? A brave lady, who could no longer stand all the lies, And risked her career and freedom to let the people know What was really happening in Ukraine,

Or our strong leader, who happens to be Guilty of mass murder?

WHO IS THE REAL FASCIST?

If you want to make a person seem evil and frightening Call him or her a fascist

If you want to make people seem scary and threatening Call them fascists. So easy to call people names, To obscure the truth, To hide the facts, To paint yourself as the virtuous hero And your enemy as a terrible villain.

Looking at the newsreels from Mariupol, At the flattened buildings and deserted streets, Hearing about the 300.000 civilians still trapped Inside their besieged, broken city, Still bravely refusing to surrender, Despite their enemy’s awful ultimatum, I find I have to ask myself Who, here, is the real fascist?

Fascists believe they have the right, Due to their strength and power, To impose their will on those lesser nations, Who do not have the honour or good fortune To be born of the right nationality. Fascists like to invade other countries, To show who is boss, to pretend That they are destroying peoples’ lives For some greater nationalist glory.

Fascists are very good at lying, Good at locking up or killing Those that dare to tell the truth. According to Putin, the war in Ukraine Is merely a special military operation, And anyone who says otherwise Is guilty of treason.

Underneath the bombed and flattened Mariupol theatre In the shivering uncertain safety of the basement, The victims of Putin’s special military operation, Try to work out how they might get some water. Unlike this poet, their only focus is survival, But, if some do survive, if perhaps One day some act in a future play, Called ‘The Siege of Mariupol’, I think we know, who the evil criminal will be And which side will appear as fascists.

4 POST SCRIPTUM

Charles B.Wordsmith POEMS

ARTISTS FOR UKRAINE

5POST SCRIPTUM

PIOTR JAKUBCZaK GOLGOTA 22

MARCIN ZEGADŁO

Mindfulness’, such a fashionable word. Like a hashtag. Instagram is full of mindfulness linked to similarly named posts. I urge you, though, to take it seriously and to focus on the here and now, especial ly when a script from World War II movies is playing out not so far away. Or something that reminds you that the Balkan War thirty years ago was a conventional conflict in Europe, the bloodiest since 1945, which also hap pened when we lived normal lives, while in some pits in the forest the corpses of women and children were covered with layers of loose earth.

So, mindfulness. After all, the last few days have been devastated by a real ity in which most of us have deigned to have delusions. Mindfulness, which I understand as squeezing the entire content out of the „here and now”, sucking the flesh from everyday life, touching the surface, feeling the fla vours, inhaling the icy air.

Go for a walk with or without a dog and focus on the fact that you are tak ing step after step. That you may have the cold honey of the March sun on your face, or leaving the metaphori cal, be glad to hear traffic, that peo ple around you are not only talking about the war, that perhaps the rain and snow have just caught you and that is the greatest discomfort at the moment. That no sniper would shoot your skull on the way to the store, and that a volley of bullets from a hand gun would not softly pierce the bus your child was taking to school.

I don’t want to pretend this doesn’t apply to me, although I cut myself off from it to some extent. I try to run away from it a bit, although I know it’s not entirely fair. I’m at an age when I’m not driven by adrenaline, which stems from the extraordinary nature of events. I know this is not entirely fair, but I still have a breath of a quite specific depression on my back, from which I am recovering and my fears are soothed into peace with phar macological support. Anyway, thanks to my friends, I had and have the op portunity to participate in real help for those who need it, so my escape is more symbolic than real. Perhaps I just need it so as not to overdo it. I don’t know.

So I take Homer for a walk and we just keep walking. I am glad that I am walk ing, that I exist and breathe. That I can still expect that in the evening I will read my books, and my lovely Wi will read hers next to me. That the kids will argue and scream, but eventually, at night, I will hear their breaths - steady and deep. That Homer’s snoring will cease when I cluck my tongue and the hamster no longer bothers us when, between one and four in the morning, it tries to prove that it can tear apart its cage and it will never die.

I am writing this tearful text because I think about all those for whom these trifles ended a few days ago, and for whom the blocks of flats and city cen tres they know so well have become a battlefield.

Nothing makes more of an impres sion on me than a prefab skyscrap er hit by a missile. Exactly the same as the ones that filled my childhood and my youth in the neighbourhood, which kept growing like a blur, flow ing into the next units.

Now I can see, whether I want to or not, how bomb craters are steaming after my neighbourhood was hit by missiles that blew whole blocks into the air. I see it in the undefined fu ture, and the spark is this high-rise building made of the material that I run into on the web.

I don’t want to look at myself this way, but I know that I owe it a lit tle to those who experience it, and I owe it a little bit to these images imprinted by a narrative well-known from stories about what happened once – how the Germans came, then the Russians – because I heard it hundreds of times while eating a crispy cake at my grandparents’ house.

So, I count on mindfulness and focus on what I can still get from a reality where some Kremlin prick placed a question mark. I walk and feel. I try to feel as much as possible. Homer is once behind me, once in front of me.He watches me carefully as if he was about to say: „ Let’s go back for dinner, man. Your two legs may hurt – I’ve got four! Get it? “ [MZ]

6 POST SCRIPTUM

PAINTINGS Ula Dzwonik

The experience of the war triggers in me a series of family stories, all family myths from two wars which, separated by twenty years, left a mark of trauma on my relatives.

That is why the bombs falling on Ukrainian cities bring back memories of my grandfather in bombed Lublin. On that September day, he was sev eral tenement houses away from the place where the poet Józef Czechow icz died in a barber’s chair, in a build ing hit by a German bomb. Photo graphs of refugees remind me of my great-grandmother and her daughters on the train to the east, where the families of professional Polish officers fighting at the front were evacuated from Częstochowa. Ligia and Krysty na. The first will be my grandmother, the second will be murdered by the Germans in Auschwitz, where she will be sent for issuing false documents to Jews from the Częstochowa ghetto.

And also my grandfather on the Bu chenwald assembly square and my mother’s mother suffering from ty phus in the hospital in Sandomierz, when the thunder of the Soviet offen sive can be heard outside the window.

And my mother’s father, who want ed to join the partisans, to Jędrusia,

but ultimately did not go, and a few years later watched the operation of “Vistula” as a conscript. I see him in the photograph in a faded blouse of a field uniform, by a radio station.

In this sense, there is no escape from what has been happening in Ukraine. It is already inside me, and it works at full speed with images, series of associations, sequences of myths, imprinted fears that they will come, burn, drive us away. And yet, these are stories that do not stick into one reality with a smartphone, Facebook, Instagram, and the world available at your fingertips. It doesn’t connect with pictures of Ukrainian teenagers with knee and elbow pads and Kal ashnikovs hanging from their necks. They are wearing the same clothes from the same chain stores as their peers in Poland. The only difference is the presence of a gun and some one teaching them how to shoot.

And yet those in the photos of the Warsaw Uprising were so similar to these Ukrainian boys and girls. We have just got used to the fact that the war is black and white, and the photos are in poor resolution. War in colour does not match the picture we know. A tank pulping a car with

living people inside is a false image even when we see it live. Our brain can’t process it yet. My brain was promised a completely different real ity. The war was supposed to be an increasingly distant memory.

At the same time, there is an unu sual social activation. Help is coming. People I know are doing fantastic things for those that have already been affected by the war. It embar rasses me. I presume there is more evil in man than good. I think this way because I know the history of this planet quite well. And that’s ex actly what I’m going to stick to, be cause it is what leads a man to aim at a maternity hospital and drop bombs on it or shoot missiles at it.

I can’t help it that, looking at the sky above my city, I imagine some ghostly raid on it. In my mind the neighbour hood burns then. And after a while, I say hello to my colleagues, and everything disappears. It’s March 2022 and where I live it is still ‘before the war’.

7POST SCRIPTUM

[MZ]

Krzysztof

Łozowski wATER

9POST SCRIPTUM

DRAWINGS

KRZYSZTOF ŁOZOWSKI

POEMS

John Sephton

HARD RAIN

dark knights in armour

mad bears marching on to war longbowmen at the border

a hard rain’s gonna fall

Kevin Morris

On my way To eat breakfast

In a café

On an ordinary Saturday, I heard birds. While in Ukraine’s Kiev Birdsong was drowned Out by bombs.

11POST SCRIPTUM

Mbarushimana

Andrea

TODAY (FOR UKRAINE)

There’s a bomb in my tumble dryer the cars are full of streets, collected in panic I look around our home at photos that we hung against today and hope the walls can keep the faces of my babies safe

Today I’m busy shedding all my pages re-learning trust like puppy in a house full of strange hands I have given my passport details out to strangers sung lullabies to men with firearms

It makes me laugh that last week if you’d asked I would have sworn I’d rather starve than eat out of a rubbish can

Today I am packing my children into brown cardboard like Amazon parcels hoping to be delivered into safe hands only, the roads are knotted people are gathered into murmurations we are a wailing vortex of unmoored plans

Today we chose between our wants and needs Tell me, where is that tutorial livestreamed? My mind keeps running back, over the scarf left on the back of the cupboard door my lost mother gave me

I have no language suitable for today My tongue is a shoe, I’m licking miles that taste like pitch, I’m pitched out of my life I’ve swallowed my pride so many times when a stranger serves us soup I look into the bowl and vomit tears

12 POST SCRIPTUM

12

13POST SCRIPTUM HOPE Paweł Wąsowicz 13

ДАНИЛО МОВЧАН

DANYLO MOVCHAN

15POST SCRIPTUM

UKRAINE

DANYLO MOVCHAN is an Ukra inian artist born in 1979 who li ves and works in Lviv, Ukraine. His works are mainly located in churches but also in private col lections in Ukraine, Belarus, Po land, Western Europe, Canada and USA. Danylo studied at the Lviv Decorative and Applied Art College named after I. Trush in its restora tion department after that he was studying Sacred Art at Lviv Natio nal Academy of Arts. In Danylo’s works, he turns to topics that can open the path to God for him. Mo vchan is looking for images of new Christian symbols, where a person with their problems stands in the centre.

16 POST SCRIPTUM

17POST SCRIPTUM WAR IN UKRAINE

There is not enough peace to continue art

In your works you draw on aesthetics and mysticism be longing to the icons of eastern literature. In our world, contemplating an icon is both a path to God as well as a miracle, and the iconographer, i.e., its author, breaks away from the habit of expecting specific cognitive con tent. (So – to an extent – the splendour of the creator is diluted.) The piece becomes a mere tool – a message. Meanwhile, your painting is unique. How do you explain this discrepancy?

For my part, I do my best to listen to my inner voice. I can’t appraise my unique relationship with God and actually I don’t want to. Ideas come to me and spark new composi tions, new images. I think this is an inherent part of every artist’s experience. But as an artist, I’m also a product of the environment and culture I live in and I draw inspiration there too. As you delve deeper into your environment, ide as begin to stream towards you. Notwithstanding, aspects of Christianity serve as additional fuel for my art. They give me food for thought.

The characters in your paintings seem to approach the viewer. They wouldn’t look out of place illustrating chil dren’s fairy tales; many of them feature a stark white background. Is this how you bridge religious and sec ular worlds because those from a secular world might not necessarily know how to interpret Byzantine icons? Don’t you sometimes feel like you are straying near the limits of the established canon?

I approach this topic very carefully and creatively. This is a direction I’ve chosen deliberately. In portraying the sa cred, one shouldn’t just take a topic and duplicate it. I see this clearly when considering centuries of iconography. New forms are always needed for a contemporary under standing of the truths of Christianity.

Is it easier to be an iconographer today in an increasing ly black and white world – a world with binary views of good and evil? Is this not in synergy with the traditional iconographic palette’s depictions of good and evil?

18 POST SCRIPTUM

My artistic language the way of my communication with the world has changed since that war

19POST SCRIPTUM

I don’t agree with that idea. I can’t say that the world has turned black and white. Our emotions have become in creasingly nuanced and fundamental to our understanding of the world around us. If anything, colours have gained definition and become more vivid, rather than becoming blacker and whiter. We’re surrounded by many colours, quite a few of them representing various forms of good. The evil in my paintings, however, remains black.

There has been a war in your homeland for over a month. You have stayed in Kiev, a city under siege. We’re observ ing the war from behind the safety of our own borders. Above all, we are filled with admiration for the incredi ble attitude shown by Ukrainians defending their country. You have demonstrated remarkable dignity and restraint with respect to the wrongs and suffering inflicted on you; no complaints, no self-pity It’s extraordinary. This attitude shares similarities with the contemplation of an icon, with full awareness of the meaning of what is happening.

In the beginning, there were a few days of shock. For me, for my family, for everyone. Eventually however, I realized that I had to create new work – to show a new reality. Naturally, many questions arose – from my artistic point of view, there was a seeming dearth of colours and words to express this tragedy. I have noticed that my own artistic language, the way I communicate with the world, has changed since the

start of the war.

For several years I have been drawing on paper with water colors. Recently, this has proved to be a particularly useful technique, as it gives me the ability to bring my ideas to life quickly.

In the visual sphere, we are dealing with real images of death again, not metaphorical ones. Images of dying kings, saints, and knights who fell in combat against evil; images of the slaughter of innocents; medieval memes are all making a return. It seems that the work of iconographers has par ticular significance and meaning today.

In this terrible time of war for Ukraine, does art provide a reprieve - for its creator, the creator’s family, and the audience - from self-doubt and crushing despair?

It’s impossible to say at this point. We’re under constant risk of death. We’re in danger of witnessing the destruc tion of our entire culture and heritage. I’m still making new work, just to survive these nightmarish days and nights. But since the onset of the war, I’ve stopped painting icons. There is not enough peace in my heart to continue this sacred art. [MK]

20 POST SCRIPTUM

21POST SCRIPTUM

The work of an icon painter has a special meaning and message today

poem: MichaŁ ZabŁocki

ONE RUSSIAN WARSHIP

sailing and sailing for very many years our good big brother, the best of all our friends people are looking and waving hands at him may he stay far out and never enter in

from land to land now, across so many seas sailing and sailing until it’s near our place! through the loudhailer they’re shouting on and on hello there! wake up! your time has also come!

one Russian warship will do with super heroes aboard one Russian warship will do give in or we’ll take a shot!

how can it be then, we’re crying bitter tears! it can’t be dreamt of in all our wildest dreams! some white flags flying, you see them flapping white I know this feeling, I know it inside out!

we’ve feared too long now to send that warship down because it should have been sunk so long ago! before it’s shooting to kill just all of us people will surely surrender many times

one Russian warship will sink let’s start the fight and do well one Russian warship will sink one shot and… go fuck yourself!

Translated by Zdzisław Zabierzewski

22 POST SCRIPTUM

GRAPHICS: AGATA DĘBICKA

23POST SCRIPTUM

people(?) to People

People who act inhumanly are no longer human

1.

There are moments in life when there is nothing you can say, when whatever you say is insufficient, as the burden of misfortune is just unimaginable. This has repeated it self throughout history, since Cain. What connects that biblical murderer with contemporary ones? The urge to dominate, enslave, abuse, humiliate ... In other words: power, the lust for which releases all moral restraints. It causes hearts to shrink into deadly stones, and con sciences to pale and fade into maddened minds at the whispers of the devil himself. The vision of absolute pow er, over family, state, and the world, is blinding. Power re gardless of the costs, without taking anyone or anything into account.

It might seem that humankind, having seen millions of victims perish and suffer in successive wars over the cen turies, would have reached a stage of development that would allow them to focus on making the world safer and its inhabitants better. To deal with diseases and epidem ics and be able to save their dying nature. Surprisingly, the caveman mentality has not changed at all. It just that the props are becoming more and more perfidious – clubs have been replaced by rockets. Regardless, the effect re mains the same: tears, blood, and senseless deaths. This has been happening shockingly close to us, with death among both the attackers and the defenders, old and young. We are not talking about toy soldiers, but people of flesh and blood, wanting to live ordinary lives. The evil that is born in insane minds is unimaginable.

All dictators ended badly, a faith awaiting the current ones sooner or later. What hurts the most is the fact that, before they end up in the darkest corners of hell, they will instigate so much evil and start fires that will not be extin guished by the rain of oblivion. These are people without hearts and consciences.

2.

I was in Ukraine some years ago and I still remember some things vividly about that stay: a glass of strong vod ka drunk in one gulp with the owner of the hotel just be fore dinner, which, despite being different from “Europe

an” standards, had an aura of deliberate cordiality. Faith locked in churches, with beautiful icons and baroque altars; with the silent wisdom of cemeteries; wandering around castles with a common history. Meetings with Poles who have lived there for generation. Kids expecting sweets from us. Singing Polish-Ukrainian songs by a bon fire. The Lvov opera, filled with angelic voices. Stories that mix heroism with cruelty. Vast expanses of fertile land. An arduous journey towards Europe after regaining their independence. Later, I met Ukrainian poets who sang and recited their own poems.

I brought a beautiful, though small, icon in a silver dress back from that trip, bought at the market with all the money I had because I liked it so much. This Ukrainian (or perhaps Polish) Mother of God with Child, hanging above my desk, greets me every single day, invoking tears for sixteen days.

3.

Something unimaginably cruel has just happened, some thing you might connect with nightmares or disaster films, the directors of which expose us to unimaginable horrors. However, this isn’t a bad dream, nor a violence-infested movie. This horror is happening as we speak, much too close for comfort. War, a word that for some might con jure up glory and heroism, but which all too often con ceals the vastness of misfortunes of children and old peo ple, men, and women, entangled in a terrible machine launched by mentally ill individuals. Would someone in their right mind consciously condemn masses of innocent people to death, cause inhuman suffering and tear up the lives of millions of innocent people? Not to mention sending their own people to death in the name of crimi nal ideologies to enslave entire nations?

As if “ordinary” misfortunes were insufficient to cause suffering – as if cancer, heart attacks, diabetes, depres sion, and hundreds of other diseases that plague people were not enough. It is difficult to discount victims of car accidents, or the aftermath of a pandemic that we still have to come to terms with.

24 POST SCRIPTUM

By in what categories do people who cause wars think? It is simply beyond my imagination. Don’t they have their own precious loved ones, or have they perhaps never been loved? How is it that they behave as if they were without conscience, without heart, without humanity? They tend to addict their closest associates and even entire nations with their inhuman charisma. The world saw some clear examples of this phenomenon in Hitler and Stalin. Although it seemed that history would not repeat itself, the truth is there for all of us to see. Why does so much evil breed in cra zy minds, turning insanity into reality, making it measurable in the number of casualties, wound ed, people made homeless, hopelessly trying to cross borders, seeking sanctuary? Their world has literally collapsed on them – so many ruined cities, villages, houses, hospitals, and schools. Pregnant women giving birth in bombarded hospitals, people terrified every time they hear alarms, horrific photos of heartbroken people saying their last goodbye to loved ones covered in blood – all manifestations of cruelty without any limits!

How will those who survive ever function nor mally again, their minds haunted by traumatic memories that cannot be erased? Will they be looked after abroad by some good-natured peo ple? Will they be able to return to their demol ished houses so they can painstakingly rebuild them?

Nobody will be able to undo the injustice suf fered, nor the cruelty that was unleashed. The only possible remedy, as always, might be time – pain may slowly fade, although it might take a generation or two before these deep wounds might be healed.

4

Even those of us lucky enough to have been born after World War II, able to live our lives without armed conflict, still inherited it from our parents. It seems that the stories of those who experienced the war have somehow been passed on in our genes. People who survived the war wit nessed how the world was turned upside down. There were victims in almost every family, including my grand mother Zofia, beaten to death by the “liberating” Russian soldiers; my father, who died prematurely of a heart con dition, after five years of captivity and forced labour in the mines in Wałbrzych; my mother, who heard the whis tle of bullets around her head for the rest of her life. They never got the most beautiful years of their youth back. I can still see the helmets, bomb fragments, unexploded shells, the nameless graves in the forest, bayonets found in a garbage can.

We were naïve to think that, believing in humanity, our advanced civilization, the exchange of goods, technology, and labour, would effectively protect the peaceful coex istence of nations, even if they believe in different polit ical systems. We were wrong to turn a blind eye to sub sequent annexations and ever greater claims that were made by a delusional leader – claims that rendered hu man life worthless, aiming to achieve more power. These

sickly ambitious fantasies were realized bloodily, using the most perfidious types of weapons.

The only comfort in all of this is that is has united the ma jority of a largely divided world. Most nations strongly dis approves of this and steps are being taken to try to stop the madmen – this time no longer through appeals and empty words, but through concrete joint actions of states.

Actions aimed at making life worth living, rather than re sort to war games, which would require sacrifices in casu alties and destroyed houses that would need to be rebuilt. However, there would be no way to resurrect the fallen.

I am constantly bothered by the question: how is it possi ble that in people’s minds house such insane visions (that later, unfortunately, are implemented)? This is more proof of the existence of evil, which is so difficult to overcome with goodness, of the existence of the devil trying to rule the world in various ways.

“People prepared this fate for people,” wrote Zofia Nałkowska at the beginning of the shocking „Medallions”. Nevertheless, I do not agree with this statement of the writer, since people who act inhumanly are no longer hu man. [JW]

25POST SCRIPTUM

Paweł Kuczyński Illustrations

26 POST SCRIPTUM

Crown

A r t i s t s F o r U k r a i n e

Ukraine

27 Together Strong

Haśka Szyjan

Haśka Szyjan (1980) – Ukrainian writer, poet and translator. She lives in Lvov and Kiev. One third of her debut novel, “Hunt, Doctor, Hunt”, was written on a mobile phone. Her second novel, “Za spynoju”, published in 2019, was the first Ukrainian novel to be given the European Union Li terature Award and it also won prizes in Ukraine: the Espresso television readers’ award and the LitAccent of the Year award. She translated DBC Pierre’s “Lights out in Wonderland”. Szyjan also created the ‘Batrachomiomachia Art Project. Her poetry has been published in Poland in Ba biniec Literacki and Slaska Strefa Gender, translated by Aneta Kaminska.

Slippers on high heels at the humanitarian post by the borderline, amongst children’s clothes and hardly worn UGGs, standing, the last ones in the line, so inadequate and lost, as if they were listening to the distant echo of interrupted shelling and want to escape but lack the courage –perhaps it’s right here, just like the fortune-telling on St. Andrew’s Day: the first across the threshold should be ready to get married. They are as inadequate as human sensuality, locked within monastery walls, where every opportunity to focus on yourself is a sin. Like a summer job as a cashier at a public toilet, a girl – a teenager, with the looks for a Vogue photoshoot. She licks her fingers, counts the banknotes that a while ago fell to the floor and looks, like a frog-like dame she adjusts the band in front of the mirror, licking her fingers again, the same that dropped the banknotes and picked them up. She lost her golden earrings on her birthday, of all days –she suspects it was a relative, although in fact the children accidentally wrapped them in a napkin and threw them in the rubbish bin. An old man plays the Lambada on his violin, accompanying this inadequateness, underlining that in the modern world it is easy to combine a kippah and wireless headphones, a Ukraine t-shirt and a taped forehead, a girl in a uniform and a civilian boy. However, here the slippers have no idea what to stick to, to cover the eyes with an arm, a watch on the wrist, and then the ears because they don’t know whether behind the door to which they so desperately want to run there’ll be barking dogs, if people argue, whether the noise is from dust cars, ice rinks, or military equipment.

28 POST SCRIPTUM

***

Kateryna Michalicyna

(SIMPLE THINGS)

children knock down the last apples from a naked tree someone knocks down a plane for some it’s easier that way because they’ve forgotten: apple stick in the transparent orchard where there is nothing but wind and naked trees and the most natural motion: throw and catch

you can’t catch a plane even the Earth is powerless and the angels let alone little you you can’t catch a plane can’t catch it in the naked sky there are no branches to get stuck in

children are laughing and knock down red-cheeked wormy sun-dried apples

Translated by Arco Van Ieperen

Kateryna Michalicyna (1982) – poet, trans lator, editor. Born in the Rivne region, she now lives in Lvov. She has a degree in biology from Rivne University and English philology from Lvov Ivana Franki University. Michali cyna works as assistant-editor at Old Lvov Publishing. She has published volumes of po etry: Powiń (2002), Pilihrym (2003) and Tiń u dzerkali (2014), as well as books for children: Babusyna hospoda, Łuhowa liryka, Chro ro ste u parku, and Pro drakoniw i szczastia. She has translated books by J.R.R. Tolkien, Oscar Wilde, and Sylvia Plath. She has translated Tomka w krainie kangurów (2011) by Alfred Szklarski from Polish. Her work has been pu blished in Poland in “Radar” and the antholo gy “East-West. Poems for Ukraine”

29POST SCRIPTUM

CARDIFF MyDogSighs

STREET ART for UKRAIne

JenksArt

31POST SCRIPTUM

LLANELLI OLD CASTLE

JenksArt

PORT TALBOT, SOUTH WALES 32

33

Maximiliano Bagnasco

34 POST SCRIPTUM ARGENTINA

Zdjecie z prywatnych zbiorów Maximiliano Bagnasco

No to

War!

35POST SCRIPTUM

Seth Globepainter & Aleksey KislowKIEV

36 POST SCRIPTUM

©Julien_Malland

Seth Globepainter PARIS

AGAINST WAR

37POST SCRIPTUM

ART

©Julien_Malland

KAWU

Poznań Poland

38 POST SCRIPTUM

stop war!

WOSKerski

39POST SCRIPTUM

SHOREDITCH, LONDON, UK

D’OH

40 POST SCRIPTUM CLEVEDON, UK BRISTOL, UK JOHN

Pieksa KRAKÓW POLAND

41POST SCRIPTUM

Christian Guémy

42 POST SCRIPTUM

PARIS

U

U Indonesia

43POST SCRIPTUM T

T

Paul Kneen Art

44 POST SCRIPTUM

STAMFORD, UK

Los

SEF

45POST SCRIPTUM

Angeles, California Venice Beach

ChemiS PRAGUE

DMITRY PROŠKIN (1986, Uralsk, Kazakhstan), performing under the pseudonym Chemis, is a Czech street art artist with Kazakh roots, main ly creating murals, i.e. large-format colorful paintings on walls.

His street-art work, like many of to day’s leading Czech artists of this gen re, began with graffiti, from which he gradually turned to creating murals. One of his greatest achievements was the invitation to showcase his work on the main wall of the Hall of Fame in New York, the place where the graffiti culture was born.

Chemis became well-known to Czech audiences thanks to the iconic image of crying President Masaryk.

The artist created many murals in which he criticized world politics or depicted current burning topics. On his wall paintings he portrayed, amongst others, President Trump in front of a broken wall.He fiercely op posed terrorist attacks in France and also condemns racism. [PS]

47POST SCRIPTUM

He stood petrified in the town square, facing south, facing the pending invasion. Unflinching he waited as all around artillery fire destroyed buildings, plumes of black acrid smoke billowed from walls and windows, debris lay scattered in the streets. In defiance he stood his ground as all around was turned to smoke and dust.

Inhabitants had long gone, shops emptied, contents smashed, wrecked, or strewn. The town no longer in turmoil, just desolate, yet he still stood waiting. Then it came, with one almighty explosion, he was gone, all that remained was a crater surrounded by scattered rubble, his remains now just twisted metal in the dust. Ten metres away his sculpted head lay in the settling dust, no longer a monument to the history of this once proud town. Defiantly he still looked south, watching as the tanks rolled past, followed by Putin’s marauders.

POEMS

Allan Murrell

Allan Murrell

UKRAINE

We see walking and running legs, rubble lying on the ground, smoke swirling, a glimpse of railings, ash and scorch marks. The camera image swinging, legs running in a park and on paving, bomb craters. Army fatigued figures stand motionless, mobile phones in hands. Women and children queuing to get on trains, their only possessions an overnight bag. These images beamed around the planet to every household TV, we sit watching in stunned incredulity, then we quietly start to weep.

DEFIANTLY

foto: Pixabay

Spring

49POST SCRIPTUM

Cleaning Radosław Ruciński

Voytek

GlinkowskiConqueror

P o l i s h A r t i s t s f o r U k r a i n e

51POST SCRIPTUM

ILYA KAMINSKY on Ukrainian, Russian, and the Language of War

1.

My family huddled by the doorframe at 4 am, debating whether or not to open the door to the stranger wear ing only his pyjama pants, who’d been pounding on the door for at least five minutes, waking the whole apartment complex. Seeing the light come on, he began shouting through the door.

“Remember me? I helped you haul your refrigerator from Pridnestrovie. Remember? We talked about Paster nak on the drive. Two hours! Tonight, they bombed the hospital. My sister is a nurse there. I stole someone’s truck and drove across the border. I don’t know anyone else. Can I make a phone call?”

So, the war stepped its shoeless foot into my childhood two decades ago, under the guise of a half-naked man gulping on the phone, victim of an early post-Soviet “humanitarian aid” campaign.

2.

During a recent visit to Ukraine, my friend the poet Boris Khersonsky and I agreed to meet at a neighbourhood café in the morning to talk about Pasternak (as if he is all anyone talks about, in our part of the world). But when I walked up the sidewalk at 9 am, the sidewalk tables were over turned, and rubble was strewn into the street from where the building had been bombed.

Living many hundreds of miles from Ukraine, away from this war, in my comfortable American backyard, what right do I have to write about this war? — and yet I cannot stop writing about it.

A crowd, including local media, was gathered around Boris as he spoke out against the bombings, against yet another fake humanitarian aid cam paign of Putin’s. Some clapped; oth ers shook their heads in disapproval. A few months later, the doors, floors, and windows of Boris’s apartment were blown up.

There are many stories like this. They are often shared in short, hurried sentences, and then the subject is changed abruptly.

“Truthful war books,” Orwell wrote, “are never acceptable to non-com batants.”

When Americans ask about recent events in Ukraine, I think of these lines from Boris’s poem: people carry explosives around the city in plastic shopping bags and little suitcases.

3.

Over the last twenty years, Ukraine has been governed by both the Rus sian-speaking East and the Ukraini an-speaking West. The government periodically uses “the language is sue” to incite conflict and violence, an effective distraction from the real

problems at hand. The most recent conflict arose in response to the in adequate policies of President Ya nukovych, who has since escaped to Russia. Yanukovych was univer sally acknowledged as the most cor rupt president the country has ever known (he’d been charged with rape and assault, among other things, all the way back to Soviet times).

However, these days, Ukraine’s new government continues to include oli garchs and professional politicians with shrewd pedigrees and question able motivations.

When the standoff between the Ya nukovych government and crowds of protesters first began in 2013, and the embattled President left the coun try shortly thereafter, Putin sent his troops into Crimea, a Ukrainian terri tory, under the pretext of passionate ly protecting the Russian-speaking population. Soon, the territory was annexed. In a few months, under the pretext of humanitarian aid, more Russian military forces were sent into another Ukrainian territory, Donbas, where a proxy war has begun.

All along the protection of Russian language was continually cited as the sole reason for the annexation and hostilities.

Does the Russian language in Ukraine need this protection? In re sponse to Putin’s occupation, many Russian-speaking Ukrainians chose to stand with their Ukrainian- speak ing neighbours, rather than against

52 POST SCRIPTUM

„How can one speak about, write about, war”

them. When the conflict began to ramp up, I received this e-mail:

I, Boris Khersonsky, work at Odes sa National University where I have directed the department of clinical psychology since 1996. All that time

I have been teaching in Russian, and no one has ever reprimanded me for “ignoring” the official Ukrainian lan guage of the state. I am more or less proficient in the Ukrainian language, but most of my students prefer lec tures in Russian, and so I lecture in that language.

I am a Russian language poet; my books have been published mostly in Moscow and St. Petersburg. My scholarly work has been published there as well.

Never (do you hear me—NEVER!) did anyone go after me for being a Rus sian poet and for teaching in Russian language in Ukraine. Everywhere I read my poems in RUSSIAN and nev er did I encounter any complications.

However, tomorrow I will read my lectures in the state language— Ukrainian. This won’t be merely a lecture—it will be a protest action in solidarity with the Ukrainian state. I call for my colleagues to join me in this action.

A Russian-language poet refuses to lecture in Russian as an act of solidar ity with occupied Ukraine. As time passed, other such emails began to arrive from poets and friends. My cousin Peter wrote from Odessa:

Our souls are worried, and we are frightened, but the city is safe. Once in a while some idiots rise up and an nounce that they are for Russia. But we in Odessa never told anyone that we are against Russia. Let Russians do whatever they want in their Mos cow and let them love our Odessa as much as they want—but not with this circus of soldiers and tanks!

Another friend, the Russian-speak ing poet Anastasia Afanasieva, wrote from the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv about Putin’s “humanitarian aid” campaign to protect her language:

In the past five years, I visited the Ukrainian-speaking Western Ukraine six times. I have never felt discrimi

ILYA KAMINSKY is the author of the acclaimed poetry collection Deaf Republic , which was called a work of “profo und imagination” by The New Yorker and was a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award in Poetry. He is also the author of DancingInOdessaand Musica Humana . His poems have been translated into numerous languages and his books have been published in many countries. In the late 1990s, Kaminsky co-fo unded Poets For Peace, an organization that sponsors poetry readings in the US and abroad. He currently holds the Bourne Chair in Poetry and is Director of Poetry@Tech at Georgia Tech.

nated against because I spoke the Russian language. Those are myths. In all the cities of Western Ukraine I have visited, I spoke with everyone in Russian—in stores, in trains, in cafes. I have found new friends. Far from feeling aggression, everyone in stead treated me with respect. I beg you, do not listen to the propagan da. Its purpose is to separate us. We are already very different, let’s not become opposite, let’s not create a war on the territory where we all live together. The military invasion which is taking place right now is the ca tastrophe for us all. Let’s not lose our minds, let’s not be afraid of non-ex istent threats, when there is a real threat: the Russian army’s invasion.

As I read the letter after letter, I couldn’t stop thinking about Boris’s refusal to speak his own language as an act of protest against the mili tary invasion. What does it mean for a poet to refuse to speak his own lan guage?

Is language a place you can leave? Is language a wall you can cross? What is on the other side of that wall?

4.

Every poet refuses the onslaught of language. This refusal manifests itself in silence illuminated by the mean ings of poetic lexis—the meanings not of what the word says, but of what it withholds. As Maurice Blan chot wrote, “To write is to be abso lutely distrustful of writing, while en trusting oneself to it entirely.”

ments like this one are put to the test. Another writer, John Berger, says this about the relationship of a person to one’s language: “One can say of language that it is potentially the only human home.” He insisted that it was “the only dwelling place that cannot be hostile to man… One can say anything to language. This is why it is a listener, closer to us than any silence or any god.” But what happens when a poet refuses his lan guage as a form of protest?

Or, to put this question in broader terms: what happens to language in wartime? Abstractions very quickly attain physical attributes. This is how the Ukrainian poet Lyudmyla Kher sonska sees her own body watching the war around her: Buried in a hu man neck, a bullet looks like an eye, sewn in. The poet Kateryna Kalytko’s war is also a physical body: War of ten comes along and lies down be tween you like a child / afraid to be left alone.

The language of poetry may or may not change us, but it shows the changes within us: the poet Ana stasia Afanasieva writes using the first-person plural “we,” showing us how the occupation of a country af fects all its citizens, no matter which language they speak:

The language of poetry may or may not change us, but it shows the changes within us. Ukraine today is a place where state

when a four-wheeler with a mortar passed down the street we didn’t ask who you are whose side are you on we fell down on the floor and lay there.

53POST SCRIPTUM

5.

On another visit to Ukraine, I saw a former neighbour of mine, now crippled by war, holding his hand out on the street. He wasn’t wearing any shoes. As I hurried by, hoping he wouldn’t recognize me, I was sud denly brought up short by his empty hand. As if he were handing me his war.

As I walked away from him, I had an eerie feeling of recognition. How similar his voice, the voices of the Ukrainian poets I’ve been speaking with, to the voices of people in Af ghanistan and Iraq, whose houses my own tax money has destroyed.

6.

In the late 20th century, the Jewish poet Paul Celan became a patron saint of writing in the midst of crisis. Composing in the German language, he has broken speech to reflect the experience of a new, violated world. This effect is happening again—this time in Ukraine—before our very eyes.

Here is the case of poet Lyuba Yakim chuk, whose family are refugees from Pervomaisk, the city which is one of the main targets of Putin’s most recent “humanitarian aid” ef fort. Answering my questions about her background, Lyuba responded:

I was born and raised in the war-torn Luhansk region and my hometown of Pervomaisk is now occupied. In May 2014 I witnessed the beginning of the war . . . In February 2015, my parents and grandmother, having survived dreadful warfare, set out to leave the occupied territory. They left under shelling fire, with a few bags of clothes. A friend of mine, a [Ukraini an] soldier, almost shot my grandma as they fled.

Discussing literature in wartime, Yakimchuk writes: “Literature rivals with the war, perhaps even loses to war in creativity, hence literature is changed by war.” In her poems, one sees how warfare cleaves her words: “don’t talk to me about Luhansk,” she writes, “it’s long since turned into hansk / Lu had been razed to the ground / to the crimson pavement.”

The bombed-out city of Pervomaisk “has been split into pervo and maisk” and the shell of Debaltsevo is now her “deb, alts, evo.” Through the prism of this fragmented language, the poet sees herself:

I stare into the horizon . . . I have gotten so very old no longer Lyuba just a –ba.

Just as Russian-language poet Kher sonsky refuses to speak his language when Russia occupies Ukraine, Yakimchuk, a Ukrainian-language poet, refuses to speak an unfrag mented language as the country is fragmented in front of her eyes. As she changes the words, breaking them down and counterpointing the sounds from within the words, the sounds testify to a knowledge they do not possess. No longer lexical yet still legible to us, the wrecked word confronts the reader mutely, both within and beyond language.

Reading this poem of witness, one is reminded that poetry is not merely a description of an event; it is an event.

the changes within us. Like a seis mograph, it registers violent occur rences. Miłosz titled his seminal text The Witness of Poetry “not because we witness it, but because it witness es us.” Living on the other side of the Iron Curtain, Zbigniew Herbert told us something similar: a poet is like a barometer for the psyche of a nation. It cannot change the weather. But it shows us what the weather is like.

8. Can examining the case of a lyric poet really show us something that is shared by many—the psyche of a nation? the music of a time?

How is it that a lyric poet’s spine trembles like a barometer’s needle? Perhaps this is because lyric poet is a very private person: in her or his privacy this individual creates a lan guage—evocative enough, strange enough—that enables her or him to speak, privately, to many people at the same time.

what rightdo I have to write about this war?

9. Living many hundreds of miles from Ukraine, away from this war, in my comfortable American backyard, what right do I have to write about this war? — and yet I cannot stop writing about it: cannot stop mulling over the words by poets of my coun try in English, this language they do not speak. Why this obsession? Be tween sentences is the silence I do not control. Even though it is a dif ferent language, the silence between sentences is still the same: it is the space in which I see a family still huddled by the doorframe at 4 am, debating whether or not to open the door to the stranger, wearing only his pyjama pants, who is shouting through the doorframe.[IK]

7.

What exactly is the poetry’s wit ness? The language of poetry may or may not change us, but it shows

54 POST SCRIPTUM

CAGE

55POST SCRIPTUM IN THE

Piotr Kamieniarz

George Wright

“War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determined not to sup port any kind of war. I am also determined to work for the removal of the causes of war” The pledge of the Peace Pledge Union

ABUSES OF POWER

A DREAM WORTH HAVING

Let’s invent some weapons of peace Fill grenades with apple blossom Make bullets of Turkish delight And the only gas would be laughing gas So we’d laugh into the night

Let’s invent some weapons of peace Mines in the road made of liquorice Knives would be of balsa wood Drones fashioned from sherbet saucers To give just hiccups would be good

Let’s invent some weapons of peace Declare all other types illegal We might just permit gob stopper stones Chocolate bombs and cola gas warfare Bomb shelters become candy floss homes

Let’s invent some weapons of peace Put the best minds to work, none to shirk Are my suggestions so terribly mad? Just look at the money invested in death Don’t you feel incredibly sad?

***

A wise hawk would know That it cannot snatch up an Eagle in its beak

The money mogul’s hold their fire, Not so the Russian troops, They turn a home to a funeral pyre While we dither and jump through hoops. ‘We’ll calibrate our response’ we say, We wont hurry to cut off SWIFT cash, As the oligarchs hide their wealth away And the tanks continue their dash. The only calibration comes from their guns And when we finally wake up to the tyrant’s game It’s too late for a nations daughter’s and son’s. We should hang our heads in shame

THE WINTER SOLDIER

The winter soldier has ice in his heart, He will do whatever he’s told, He’s not complete, he’s just a part, Of a machine to take and to hold. The winter soldier will aim his rifle At whatever stands in his way Opposing voices he will stifle, Only his orders have any sway.

The winter soldier has no guilt, No sense of right or wrong, No concern for any blood that’s spilt Or of being where he doesn’t belong.

The winter soldier aims the rocket That splinters family home’s He holds many lives in his pocket, Not bothered by their burning bones. The winter soldier isn’t called to account, He’s only doing as he’s been told, And all his dark deeds he will discount As being daring, brave and bold. The winter soldier feels no fright But there’ll be visits in the years ahead, Ghosts will point their fingers in the night, And he will meet the many dead.

56 POST SCRIPTUM

RC 57

58

TATIANA AVERINA

59

Ukraine 59

Three

60 POST SCRIPTUM obraz olejny 80x100

wishes BOGNA JARZEMSKA-MISZTALSKA

maggie hall

Voices of War

Weaponry powered through political fear.

A dark forest lost people. Shifting built spaces, as guided paths trick. Commitment to task, controlled nature. Outcome handing death to chaos. Training minds to hate and follow, an unordered order of jackals.

Words of deconstructing fear. Propagating monster, rape and pillage, a system betrayed by raged violence. Blood meridian meteor showers. War the highest art canvassing death. Blood turns, life cycles, telephone lines escape. Baron lands divide peeling away toughened skin, veiled behind violence. Where does it begin and end? As the justice of truth lies in pain.

A political cold case; Summary; Resolution; Intelligence. In a database of fingerprints, agenda and resolutions. Evidence of investigation collected and assessed. This last phase of speech hung by wars gate. Working to pay off another life, timing out the clock strikes nine. Beds left unmade for the final visit.

Trust as the postman waits Trust as communications cut Trust as the knife breaks innocent skin

Nine black angels in a warning of fire. Dancing in a threaded waltz, touching each other. A beautiful murder under the rain, a passage into the next day. A warning that yesterday is still awake. Today I witnessed the beginning of the last end. A woman nine months pregnant, an intravenous drip. Synthetic locks, gold sheathing the wanton chest. There in a solitude stands the lady looking down. filtering light through a purple haze, indigo dreams weave her into a day from past-future shades of grey. Silently another arm turns to cradle, touching the place where her child may once have been. Washing away the ghost of nine months. A collection of memories final play, a statue pink and grey. Nameless although named.

61POST SCRIPTUM

Antiquity

62 POST SCRIPTUM 62

Iwona Siwek-Front

63POST SCRIPTUM

63

EXODUS

64 POST SCRIPTUM

Iwona Siwek-Front

65POST SCRIPTUM

Serce mi pęka.

66 POST SCRIPTUM Ewa Klonowska Exodus

Malowałam ten obraz i niejedna łza spadła na paletę, mieszając się z farbami...

NEVER THIS MUCH EVIL

The Russian aggressors

Pretend to be like American heroes

In their own right

Their hatred drips Like flowing sweat And their blades and fire Stun innocents

Many Ukrainians have died Many have been displaced Since foggy February And that year last year They could not call Any Russians heroes Because the invaders Only ripped and tore The Russian troops Are as far from being heroes

As Earth is from the farthest stars And children weep in fear The Russians have struck And drawn blood

There has never been This much evil

Muhammad Khurram Salim

IN PAIN SOME LAUGHTER

Those kids in the Ukraine

They were laughing in the rain They had their toys Little cars for boys

Their mothers wiped tears They were born to care Children running among ruins Loving what they were doing Those little feet And eyes to greet Saw a sky of blue They wanted to fly up to Those children of war

Under the silver stars Dreamt of heaven And played again

SITTING ON OUR HANDS

The rest of the world Sits on its hands

Doing nothing for Ukraine

THE MAN ON HIS FACE

Lying in disgrace

The man on his face

With his hands tied behind his back

His breath gone for good A glimpse of him And a stifled scream

Make it real that death Is reigning in Ukraine

For all those who died Our eyes have cried

We’ve clung on to hope For the others More slaughter continues Every day in the news

That man reminds us Of how freedom cries

We watch the world’s suffering

With no heed for woes

We only like ourselves

Our hearts are hardened

By the harsh realities of life We can’t see beyond Our everyday cares

And headaches … the stuff

The devils spit at us We sit on our hands

As the victims’ hands burn We protect our hands

As they have theirs mangled One day we will sit up And take notice

When our skies will signal The invasion of evil

67POST SCRIPTUM

68 POST SCRIPTUM

Things haven’t been right since last summer

69POST SCRIPTUM

We are not talking to the bear ARTUR ZIENKO

Symphony of the Love

Colors vs War

ALIREZA KARIMI MOGHADDAM

71POST SCRIPTUM

IRAN

LORAINE SAACKS

BEYOND THE CAVES

I’m deep underground in Chislehurst Caves, With Messerschmitts raining their bombs down in waves. Tea trolleys and bunks and medical teams, Air Raid Wardens, some clergy, a few frantic screams.

Huddled up in our haunt while the harsh Heinkels taunt I’m three and I think it’s good fun. How would I know, that while I’m lying low, My cousins are killed by the Hun?

My Grandpa is silent, he’s too shocked to speak My sorrowing Grandma has tears on her cheek. I’m of immigrant stock, barely four decades, Half my family in Poland are shunted by raids.

Yet, one lifetime later, I’m asked to embrace, To forget and forgive the supposed Master Race. I’ve inherited photos; viewed the Shoah website It’s my ‘living memory’ that I’m asked to blight. Should future millennia institute change,

And mind-sets of violence be spurned, Maybe such a truce would serve to diffuse, Warring factions where memories still burned. But while I’m still alive, my bloodline will hear,

Poems

How their forbears were smitten with fear. Historical footnotes, a tapestry yarn, airbrushing out wails in the wind, Will never erase the actions so base, of the inhuman tyrants who sinned

NO VICTORY IN CHISLEHURST

The war was over, victory ours, Soldiers welcomed home with flowers.

But were we whole? Were we content? We children knew not what grief meant.

Our dear beloved matriarch Became reclusive, lost her spark. Her kith and kin could not take flight, For Bergen-Belsen was their plight.

Grandma knew, by letters vanished, Her loved ones to the camp were banished. No word was heard – her heart bore pain; Who could conceive whole families slain?

We saw our grandma’s weeping eyes, We heard her moaning, anguished cries. But we were small, all fours and fives, No-one explained about smashed lives.

76 72

Matthew Dover

7377

78 74

Yaryna Movchan

75POST SCRIPTUM UKRAINE

79 Icons 75

A wheel is a form in which I feel good. A body in a circle is relaxed, frozen in happiness.

An artist with a brush, recre ating the world during the war uses sharper shapes War is bad. It is the result of human weakness –a soul shortage.

76 POST SCRIPTUM

YARYNA MOVCHANUKRAINE

77POST SCRIPTUM

Anna

Ponoma renko

79POST SCRIPTUM

Ukraine

Ryszard Kupidura, expert on Eastern Eu rope, translator, assis tant professor at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Faculty of Modern Language Studies and Literatures, Institute of Russian and Ukrainian Studies, De partment of Ukrainian Studies. Collaborating with the ANAGRAM Publishing House on an ongoing basis

About literature and the war in Ukraine Ryszard Kupidura

We simply cannot conceive of war. We cannot recreate or reenact the emotions that accompany a human being during war. The war in Ukraine, as we know, has been raging for eight years. Re porters who write about the conflict in Donbas were somewhat surprised to discover that, in regions located not far away from military activities, e.g. in Kramatorsk or Siewierodonieck, people tried to lead normal lives. However, if we really think about it, it ceases to surprise us. There actual ly is beauty in the fact that in places where people are able to find just a little free space, even the smallest piece of land without the aura of war, then they immediately get back to their daily affairs, children start to go to playgrounds again. Because war is just something completely inhumane, it creates an environment in which a human does not naturally exist.

After 24 February, I have noticed different attitudes among readers. Some were unable to reach for litera ture during those days. There were at least two reasons for this. The most obvious one was being unable to fo cus on a book. Some, however, de

cided not to read due to the feeling of guilt. According to them, reading a book when other people are fighting or hiding from bombs would be igno ble. It is worth remembering, how ever, that staying within the world of literature does not necessarily mean we are ignorant. Quite the contrary – it can be our manifestation of hu manity.

This is supported by the words of Bogdan Kolomiychuk, who, as a cur rent member of the Lviv Territorial Guard, wrote on Facebook that it had become extremely important for him that people still read his books and shared their thoughts on social media. He treats it as a reminiscence of his former life he already longs to and wants to come back to as soon as possible.

I reckon the Ukrainian culture has become important for at least sev eral reasons. On one hand, we nat urally want to know more about the country and people who are going through this tragic time of their histo ry. On the other hand, I think there is more to this specific Ukrainian case. As the Polish nation, we are a part of this history. At least because we have

opened the doors to our homes for Ukrainians who are fleeing from war. Have you noticed that people who take in Ukrainians often do not refer to them as “refugees”, but instead as “guests”? They will say: “I’m hav ing guests from Ukraine”. This is ex tremely significant. Language starts to react to the changing reality. A very special bond is now develop ing between Poles and Ukrainians. I would even say “brotherhood”, only if I did not remember what the Sovi et and then Russian propaganda had made of the term “brother nations”. I expect that the language – I hope it will be the language of poetry at first – will find new metaphors to describe what is currently happening between us and Ukrainians. I am convinced that literature will soon react to these new intercultural phenomena that are full of very positive energy. En ergy we have been needing so much and have waited for. I am very glad that the Anagram Publishing House I have the pleasure to collaborate with is actively taking part in popularising the literary embrace of all these phe nomena. May this cruel war end as soon as possible. We can handle the rest.

80 POST SCRIPTUM

[RK]

81POST SCRIPTUM KATARZYNA ZYGADLEWICZ

Destroyed things. Burnt things. Remembered things.

RC

Nick Alldridge POEMS

BLACK RUSSIA

Russia bleeds her black oil blood

Running through her pipelines

Laden on her tankers

In the bellies of her tanks.

She breaths in her own gas

As though it was air on fire

With her glorious pride

And all that comes after:

Pride in conquest leads to defeat, Pride in victory leads to despair, Pride in greed leads to suffering, And the pride of a bully leads to his fall.

Russia is capitalism gone mad

It is Gazprom and Rosneft

Unfettered and unchecked.

Corporate greed controls the state Uncaring, unfeeling, less human than hate.

She lies and dissembles to any who will listen.

Pity the humans caught in her webs

As Mother Russia eats her children

We look on in disbelief. And her neighbours suffer more Than words can relate.

VLAD

Two motes of darkness meet your gaze. A man who lives and breathes control unafraid of power plays and desperate measures can still, and always will, manifest his own downfall but not before he rips the world apart, thrashing against his own inevitable fate. His cancer spreading to the edges, collapsing to the centre, before another’s fingertips pull down the lids to separate his darkness from this Earth.

LOST THINGS

Things. So many things. Only things. Suddenly gone things. Snatched away things. Destroyed things. Burnt things. Remembered things. Things holding memories. Things holding dreams. So many things. Only things. Home things. Homes are things. Lost things. Burnt things. A Bromley house fire. A city in Ukraine.

Accident or negligence or a deliberate act. Things. So many things. Not only things. Fire fighters, warnings, or none of that. And not just things, much more than that. But also things. Remember that.

83POST SCRIPTUM

Piotr Jakubczak

84 POST SCRIPTUM

85POST SCRIPTUM WAR

Robin Pilcher

CELLAR

To young minds in happier times a place of adventure, Aladdin’s cave: bare bulb casting dancing shadows into cobwebbed corners, a modest stash of wine, stored potatoes, onions, apples, all fragrancing the chilly air, assuring us of times of plenty, a continuity.

Now, a different reassurance, as life crumbles above our heads: we wait in darkness now, listen for the whine and crump of shells as dust of ages, dislodged, sprinkles our faces in mockery of benedictions seemingly beyond our reach.

And yet, like sown seeds, we will emerge from the dark and broken earth, vines pushing through cracked concrete, to thrive again.

86 POST SCRIPTUM

87POST SCRIPTUM

Agnieszka

88 POST SCRIPTUM

Traczyńska

89POST SCRIPTUM

Radek Ruciński A Girl From Kiev

90 POST SCRIPTUM

illustration:

AGNIESZKA LITWIN

YOU JUST NAMED THE WAR

ELŻBIETA ISAKIEWICZ

Hurricanes born of Atlantic lows tear off Eu rope’s rooftops, rip trees from soil (their exhumed roots exposed to the light), and evoke lament for losses amongst the rubble. Beyond the Polish border, a dictator strikes a sovereign state. As if the plague precipitated an avalanche of phenomena and events delivering knock-out blows to the world.

And we look on powerless and, with white-knuck led panic, scoop bits of earth – once our land –into a sack.

My mother, a borderlandist, repeats what she said at the beginning of the pandemic. As long as the young survive. On television, she watches images of war sweeping through the land of her youth yet again, a hair’s breadth from her birth place. The coronavirus has lost its crown, it no longer reigns supreme in the media, it has been pushed from the podium by the bloody assault. -

I dreamt it - nods her head as she scratches the cat’s belly.- I saw a swamp with splinters of broken tables and chairs, rags streaked with mud. Wilt ed, tarnished flowers. A crowd was clamoring at a nearby hunting shop at the end of the street. They were Ukrainians, residents of Warsaw. They were buying weapons for their brothers. I dropped some money in the collection jar they had propped up.

For the first time ever I’m paying for a rifle that will be aimed at someone’s chest in instinctive self-defense – I don’t hesitate. After all, I am a woman.

This is how history arrived at my doorstep. The street outlet will never be the same. The word „later” lingers, spanning its interval. [EI]

A fragment of the new book „Moments”, prepared for printing – by Elżbieta Isakiewicz.

91POST SCRIPTUM

Ted Smith-Orr

The Beginning

The steel blanket casts it’s red shadow, Shrouding the ragged line of bodies, Escaping to a hopeful freedom

Refugees in their own country. Some driving, until the petrol is gone Or engines break down, From the eternal waiting. Waiting for the road to clear.

Others walking: walking on sole-less shoes

Carrying only shopping bags Crammed with small but sacred possessions. Soulful hearts leading them forwards.

Babies swaddled in soft linen And parents’ jackets. Some invent games and quizzes To occupy their children And join in the Ukrainian National anthem. The spirit of war cannot defeat Their spirit of humanity.

The imperial rainfall of sickles hammer the ground Destroying deserted buildings and the red steel blanket Follows the hunched shoulders And a sea of woollen hats silhouette Against the ashen red sky.

92 POST SCRIPTUM

Illustration: Renata Cygan

Illustration: Renata Cygan

94 POST SCRIPTUM

Yurii

Ivantsyk Ukraine

95POST SCRIPTUM

Ann Lovelace

CORPORAL DIXON REMEMBERS

Nearly half a million soldiers stranded on Dunkirk sands.

Nothing to eat and fearing we were trapped and in enemy hands

Stukka planes screeching over us, flames and smoke all around

Exhausted by thirst and hunger, bombarded by the bombs’ blasting sound.

What would be the outcome? We lay there awaiting our fate.

Hoping for some respite and for the nightmare to abate.

And then it came – the miracle, gradually over several days

A diverse means of transport appeared through the smoky haze.

Fishing smacks and pleasure craft, boas of every kind,

All braving the dangerous journey with one plan only in mind.

To transport we thousands of soldiers back to the British shore

Ferrying their passengers to safety, before going back for more.

Passengers like me, Douglas Dixon a corporal in the Medical Corps.

Who like thousands of others thought nothing was solved by war.

But knowing that Hitler was determined to overrun our land

With reluctance saw it as my duty to lend a helping hand.

Now I am past my nineties, married for seventy years

I still so vividly remember how my desperation turned to cheers.

After five days of near starvation was the best sight I’d ever seen,

The famous paddle boat of its day, the popular Medway Queen.

One of hundreds of other craft manned by bands of men

Who not only volunteered once, but again, again and again.

Crossing the English Channel, leaving frightened children and wives

In the biggest transport operation, saving half a million lives.

My heart bleeds for the trapped in Ukraine, with its all too familiar story.

The suffering and terror and all for no more than Putin’s glory.

inspired by Corporal Dixon

96 POST SCRIPTUM

97POST SCRIPTUM JAROSŁAW KRAWCZAK Photography

passers by

The hustle and bustle of the street. Cars pass each other, disperse; people skulk by and disappear into the alleys. Most don’t know each other. We don’t know where they came from nor where they’re going. They carry their bags, their problems. Feel some joy. It’s us, PEOPLE.