making!

The e-magazine for the Fibrous Forest Products Sector

Produced by: The Paper Industry Technical Association

Publishers of:

Volume 10, Number 3, 2024

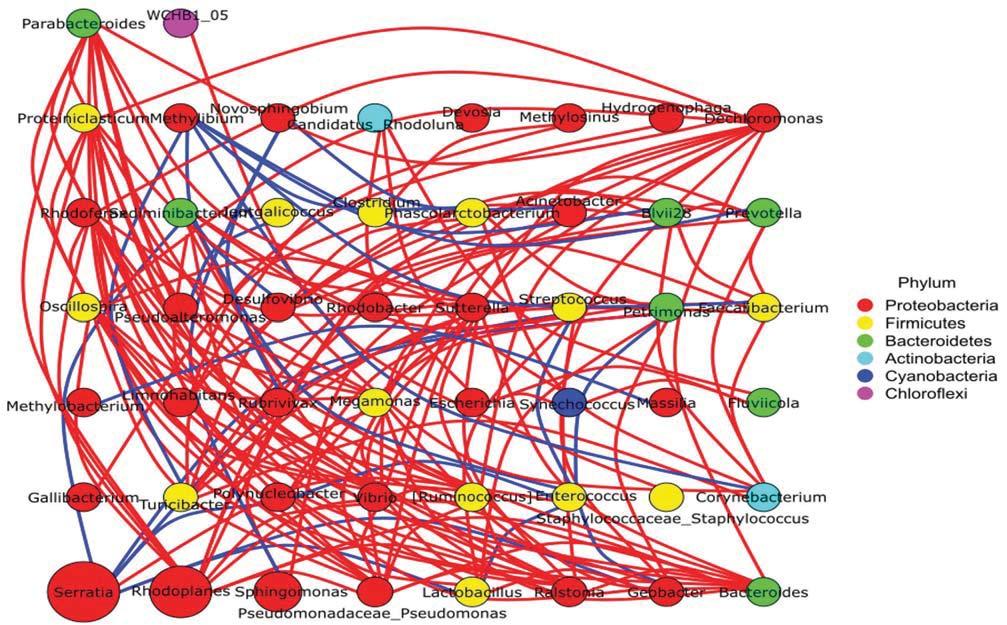

PAPERmaking!

FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF PAPER TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL® R T P O P T

CONTENTS:

FEATURE ARTICLES:

1. Coatings: Functional surfaces, films and coatings with lignin – a review.

2. Nanocellulose: Fit-for-use nanofibrillated cellulose from recovered paper.

3. Chemistry: Boosting inorganic filler retention.

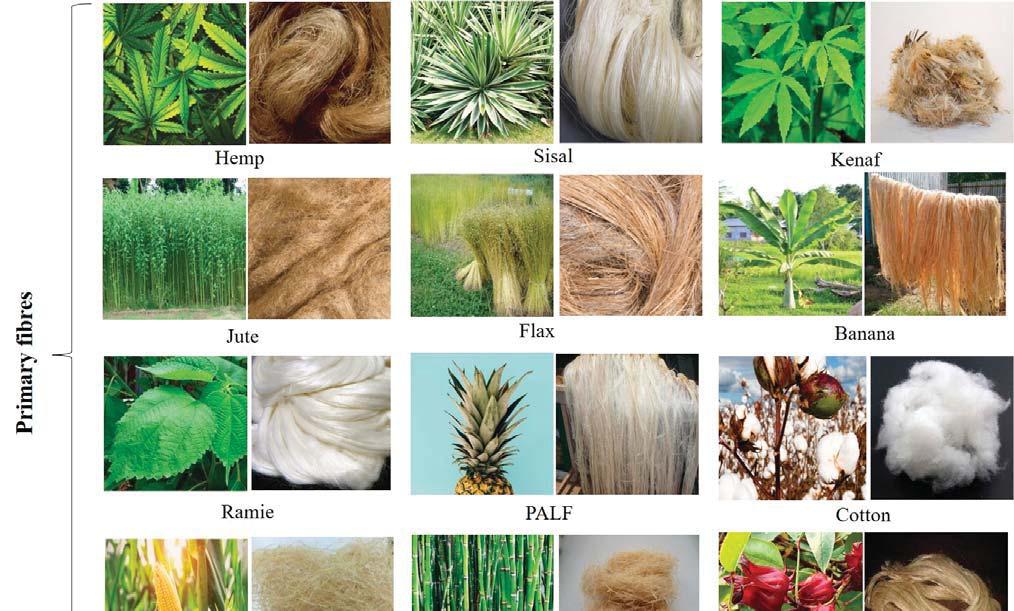

4. Tissue: Evaluation of special pulps for greener tissue paper.

5. Water Treatment: Degradation of lignin-containing wastewaters with bacteria.

6. Sustainability: Which wastepaper should not be processed?

7. Wood Panel: Wood-based panels from recycled wood – a review.

8. Packaging: Recent advances in fibre-based packaging for food applications.

9. Food Contact: Critical review of test methods.

10. Heart Health: Heart-heathy diet – 8 steps to prevent heart disease.

11. Negotiation: Ten simple tips to improve negotiating skills.

12. Computers: Keyboard shortcuts.

SUPPLIERS NEWS SECTION:

News / Products / Services:

Section 1 – PITA CORPORATE MEMBERS

AFT / PILZ / VALMET

Section 2 – PITA NON-CORPORATE MEMBERS ANDRITZ / VOITH

Section 3 – NON-PITA SUPPLIER MEMBERS

BTG / POWER ADHESIVES / SIEGWERK / VISION ENGINEERING

Advertisers: ABB / FINBOW / VAKUO

DATA COMPILATION:

Events: PITA Courses & International Conferences / Exhibitions & Gold Medal Awards

Installations: Overview of equipment orders and installations between Jul. and Nov.

Research Articles: Recent peer-reviewed articles from the technical paper press.

Technical Abstracts: Recent peer-reviewed articles from the general scientific press.

Career Opportunity: Production Engineer at Holmen, Workington Mill

The Paper Industry Technical Association (PITA) is an independent organisation which operates for the general benefit of its members – both individual and corporate – dedicated to promoting and improving the technical and scientific knowledge of those working in the UK pulp and paper industry. Formed in 1960, it serves the Industry, both manufacturers and suppliers, by providing a forum for members to meet and network; it organises visits, conferences and training seminars that cover all aspects of papermaking science. It also publishes the prestigious journal Paper Technology International® and the PITA Annual Review , both sent free to members, and a range of other technical publications which include conference proceedings and the acclaimed Essential Guide to Aqueous Coating.

Volume 10, Number 3, 2024

PAPERmaking!

FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF PAPER TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL® R T P O P T

Functional surfaces, films, and coatings with lignin – a critical review

Paper Technology International® PITA Annual Review

Essential Guide to Aqueous Coating

RSCAdvances

REVIEW

Citethis: RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529

Received22ndDecember2022

Accepted3rdMarch2023

DOI:10.1039/d2ra08179b

rsc.li/rsc-advances

1.Introduction

View Article Online View Journal | View Issue

Functionalsurfaces, films,andcoatingswithlignin

JostRuwoldt,* FredrikHeenBlindheimandGaryChinga-Carrasco

Ligninisthemostabundantpolyaromaticbiopolymer.Duetoitsrichandversatilechemistry,many applicationshavebeenproposed,whichincludetheformulationoffunctionalcoatingsand films.In additiontoreplacingfossil-basedpolymers,theligninbiopolymercanbepartofnewmaterialsolutions. Functionalitiesmaybeadded,suchasUV-blocking,oxygenscavenging,antimicrobial,andbarrier properties,whichdrawonlignin'sintrinsicanduniquefeatures.Asaresult,variousapplicationshave beenproposed,includingpolymercoatings,adsorbents,paper-sizingadditives,woodveneers,food packaging,biomaterials,fertilizers,corrosioninhibitors,andantifoulingmembranes.Today,technical ligninisproducedinlargevolumesinthepulpandpaperindustry,whereasevenmorediverseproducts areprospectedtobeavailablefromfuturebiorefineries.Developingnewapplicationsforligninishence paramount – bothfromatechnologicalandeconomicpointofview.Thisreviewarticleistherefore summarizinganddiscussingthecurrentresearch-stateoffunctionalsurfaces, films,andcoatingswith lignin,whereemphasisisputontheformulationandapplicationofsuchsolutions.

Ligninisthesecondmostabundantbiopolymeronearth,aer cellulose.Naturalligninissynthesizedfromthethreemonolignolprecursors,namely p-hydroxyphenyl(Hunit),guaiacyl(G unit),andsyringyl(Sunit)phenylpropanoid.1 Ligninfrom sowoodconsistsprimarilyofGunits,whereashardwood lignincontainsbothGandSunits.2 Moreover,ligninfrom annualplants,suchasgrassorstraw,cancontainallthree monolignolunits.

RISEPFIAS,Høgskoleringen6B,Trondheim7491,Norway.E-mail:jostru.chemeng@ gmail.com

DrJostRuwoldtisaresearch scientistatRISEPFI,Norway. HegraduatedwithaPhDin ChemicalEngineeringfromthe NorwegianUniversityofScience andTechnology(NTNU)in 2018,andanMScinChemical andBioprocessEngineering fromHamburgUniversityof Technology(TUHH)in2015.His currentworkincludeslignin technology,thermoformingof woodpulp,andbiomass conversionandutilization.InadditiontohisworkatRISEPFI,he isavisitingresearcherandlectureratTUBerlin,Germany.

Technicalligninistheproductofbiomassseparation processesandhencediffersfromnaturalorpristinelignin,asit isfoundinlignocellulosebiomass.3 Thecompositionand propertiesoftechnicalligninarelargelydeterminedbytheir botanicalorigin,extractionprocess,purication,andpotential chemicalmodication.4 Presently,therearesome50–70million tonstechnicalligninavailablefrompulpingorbiorenery operations.Mostisburnedtoproduceenergyinbiorenery processesandonlyapprox.2%issoldcommercially.5 Technical ligninisolatedfrompulpingprocessesincludesKra andsoda ligninfromalkalipulping,lignosulfonatesfromsultepulping, andorganosolvligninfromsolventpulping.6 Thetwomain typesoftechnicalligninarelignosulfonates(approx.1million

DrFredrikHeenBlindheimis aPostdoctoralresearcherat RISEPFI.HereceivedaPhDin OrganicChemistryatthe NorwegianUniversityofScience andTechnology,specializingin medicinalchemistryandthe developmentofsmall-molecule bacterialkinaseinhibitors.In hiscurrentposition,heworks withchemicalmodication, quantication,andcharacterizationoftechnicalligninsfor greenapplicationsinindustry.Hismaininterestsareinorganic synthesisandspectroscopicanalysis.

©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553| 12529

tonsperyear)andkra lignin(<100000tonsperyear).In addition,theadventofhydrolysisandsteam-explosionlignin havecreatednewtypesoftechnicallignin.7,8 Theuseofionicliquidsorsupercriticalsolventshavefurthermoreyieldedthe productsionosolvligninandaquasolvlignin,respectively,with newandinterestingfeatures.9,10

Ligninispolyaromaticandduetothisstructure,itisless hydrophilicthanpolysaccharidicbiopolymers, e.g.,cellulose, hemicellulose,starch,alginateorchitosan.11 Itishence apromisingcandidateinvariousapplications,including:(i) reductionofwettabilityofhydrophilicmaterials,(ii)additionof functionalities,suchasprotectionfromUVlight,antioxidant andantimicrobialproperties,and(iii)tailoringofmaterialsand formulations, e.g.,forcontrolledsubstancerelease,adsorption, orantifoulingmechanisms.12–16 However,chemicalmodicationisrequiredformostapplicationsoflignin.Suchmodicationsfrequentlymakeuseoflignin'shydroxylgroups,for example,bygraingreactionsduringphosphorylation,sulfomethylation,esterication,oramination.17 Thearomatic moietiesinlignincanfurthermorebetargetedfor, e.g.,replacingphenolinformaldehyderesins.18 Atlast,thecarboxylgroups inligninmayalsoserveasreactivesitesforpolyesters.19

Interesthasalsobeenstrongfortheuseoftechnicalligninin polymericmaterials, e.g.,forthermoplasticsorthermosets.20 Processabilityoflignininthermoplasticscanbedonewithout modication,asligninisaninherentlythermoplasticmaterial.21,22 Lignin'sglasstransitiontemperaturecanrangefrom about60–190°Candmaydependonmanyfactors,including thebotanicaloriginandpulpingtype,moisturecontent,and chemicalmodication.23,24 Lignincanalsobechemically modiedtoimprovetheapplicationofligninasspecialty chemicalsorinpolymericmaterials.25–27 Additionally,the utilizationofligninasmacromonomer, i.e.,thermoset precursor,canbedoneaspartofpolyurethanes,polyesters, epoxideresins,andphenolicresins.11 End-usesincludethe productionofrigidorelasticfoams,rigidandself-healing materials,adhesives,biocomposites,andcoatings.19,28–33

DrGaryChingaCarrascowas borninChileandmovedtoNorwayin1987.Hegraduatedwith aCand.scient.degreeincell biology(1997)andDringin chemicalengineering(2002).He wasoneoftworecipientsofthe NorwegianWoodProcessing AssociationAward2019for nanocelluloseresearchand winnerofthe2021 – TAPPI's InternationalNanotechnology DivisionMid-CareerAward.Heis AssociateEditoroftheBioengineeringJournal,andEditor-in-Chief oftheSection – NanotechnologyApplicationsinBioengineering. Currently,heisleadscientistatRISEPFIintheBiopolymersand Biocompositesarea.

Onelong-heldbeliefisthatligninprovideswater-proongin thewoodcellwalltosupportwater-transport.34 Despiteyielding acontactanglebelow90°,whichwouldberequiredtoposeas ahydrophobicmaterial,variousresearchershaveshownthat lignincanreducethewettabilityandwater-uptakeofwoodand pulpproducts.18,35–37 Hence,bothtechnicalandchemically modiedligninhavebeenproposedasadditivesforpackaging materials.38 Reductionofwettabilityof ber-basedpackingis aparticularlyinterestingapplication,consideringenvironmentalandsocietaldriversregardingreductionofsingle-use plasticsandenvironmentalpollution.Lignincouldthusform thebasisofcoatingsorimpregnationblends,providedthatthe lignin-coatingcomplieswithfoodcontactrequirements.One exampleforlignin-blendsisthecombinationwithstarch duringsurface-sizingofpaper,whichcanimproveextensibility andreducewettingofthestarch-matrix.35,39 Layer-by-layer assemblywithmultivalentcationsorpolycationicpolymers hasalsobeendone,whichcanimprovethestrengthand hydrophobicityofcellulose.40,41

Otherapplicationsoflignin,itsderivativesandmixtures includetheuseforcontrolled-releasefertilizers,antifouling membranes, reretardancy,dyesorption,wastewatertreatment,andcorrosioninhibitors.14–16,42–44 Onepublicationeven reportedanunintentionalbutyetadvantageouscoatingofcoir bers,wherethelignindelayedoxidationandthermaldegradationofthe bersinapolypropylenecomposite.45

Majordriversforusingligninareeconomicalaspectsby attributingvaluetoaby-productfrompulpingorbiorenery operations,andsustainabilitybyreplacingfossil-basedmaterialswithbiopolymers.Manyapplicationscanthusbenetfrom theinclusionoflignininfunctionalsurfaces, lms,andcoatings.Themechanismofactionandapplicationmodecan herebydiffergreatly.Thisreviewthereforerepresentsaneffort tostructureandsummarizerecentprogress,whereemphasisis putonboththeprocessand naluseforlignininsurfacesand coatings.

2.Fundamentals

2.1.Structureandcompositionofnaturallignin Ligninispartofthelignin-carbohydratecomplexes(LCC)that arefoundincellwallsofplantsandwoodymaterials,asillustratedinFig.1.Thecellulose bersaretightlyboundto acomplexnetworkofhemicelluloseandlignin,andthethree biopolymersprovidestrengthandstabilitytothecellwalls.In additiontoprovidingstructuralintegrity,ligninhelpsbuilding hydrophobicsurfaceswhichareimportantintransportchannelsforwaterandnutrients.46

Thecomplexligninnetworkconsistsofthethree4-hydroxyphenylpropyleneunits,ormonolignols,formedfromthe parentcompounds p-coumaryl-(p-hydroxyphenyl,H-unit), coniferyl-(guaiacyl,G-unit)andsinapylalcohol(syringyl,Sunit),seeFig.2.47 Themonolignolsdifferonlyinthepresence orabsenceofoneortwoaromaticmethoxygroups ortho tothe hydroxylgroup.Thesearesynthesized invivo fromthearomatic aminoacidphenylalanine,formedintheshikimicacidpathway inplants.48 Theresultantmonolignolsundergoavarietyof

12530 | RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Fig.1 Compositionoflignocellulosicbiomassandthestructuralrolesofcellulose,hemicellulose,andlignin.46

Fig.2 Monolignolstructureandpositionsindicatedbybluenumbersandletters.

radicalcross-couplingreactionswhichresultsinthecomplex, andvaried,ligninnetwork.Theratiosofthethreemonolignols inligninfromdifferentsourcescanvaryquitesignicantly, hardwoodligninscontainG-(25–50%)andS-units(50–70%), sowoodligninscontainmostlyG-units(80–90%),whilegrass lignincontainsmixturesofS-(25–50%),G-(25–50%)andHunits(10–25%).49

Themonolignolcomposition(H:G:Sratio)canalsovary betweentissuetypesinthesameorganism,whichhasbeen illustratedinthecorkoak, Quercussuber.Ligninfromthexylem (1:45:55)andphloem(1:58:41)differlessincomposition thanthetwocomparedtothephellem(cork-part,2:85:13).

Thesedifferencesaffecttheoccurrenceofspecicinterunit linkages,whereanincreaseinS-unitsleadtoanincreasein alkyl–arylether(b-O-4)bonds:68%incork,71%inphloem, 77%inxylem.50

Thedifferenceinabundanceofthethreemonolignolslead tomanydifferenttypesofinterunitlinkagesinlignin,specicallybetweenangiosperm(hardwoodandgrass)andgymnosperm(sowood)lignin.51 Themostcommoninterunitlinkage isthe b-O-4alkyl–aryletherbond(Fig.3),whichoccursbetween 45–50%or60–62%ofphenylpropyleneunit(C9 units)in

©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

sowoodsandhardwoods,respectively.Asthisisthemost commonlinkage,manydelignicationprocessestargetthis speciclinkage.Forsowoods,the5–5linkageisalsoimportant,andhasanabundanceof18–25%per100C9 units,while thislinkageoccursonlyaround3–9%inhardwoods.52

Intheprocessofisolatingtechnicallignins,boththelabile aryl-alkyland b-O-4bondsaremostpronetocleavage.53 This resultsintechnicalligninshavingmorecondensedandvariable structuresthannativelignin,andawidevarietyinmolecular weight(Mw).Massaveragevalues(Mw)of1000–15000gmol 1 forsodalignin,1500–25000gmol 1 forKra lignin,and1000–150000gmol 1 forlignosulfonateshavebeenreported, dependingonbotanicaloriginandprocessconditions.54 Native ligninisavirtuallyinnitemacromerthatisbothrandomlyandpoly-branched.55 Thebondsbetweentheligninand surroundinghemicelluloseandcellulosefoundinLCChave recentlybeenreviewed.56 Allsowoodlignin,and47–66%of hardwoodlignin,isreportedlyboundcovalentlytocarbohydrates,andmainlytohemicellulose.Themostcommontypesof linkagesfoundinLCCsarebenzylether-,benzylester-,ferulate ester-,phenylglycosidic-anddiferulateesterbonds.57 Notethat duetothehighdegreeofvariabilityininter-unitandLCC

Fig.3 Commonlinkagesbetweenmonolignolsidentifiedinlignins.51,52

linkages,Fig.4shouldonlybetakenasanillustrativeexample. Theligninmacromoleculeispolydisperseandmayexhibit variouslinkagesandfunctionalgroups.4 Inotherwords,lignin shouldbeconsideredasstatisticalentitiesratherthandistinct polymers.

2.2.Isolationoftechnicallignin

Lignocellulosicbiomassconsistsofcellulose(30–50%),hemicellulose(20–35%)andlignin(15–30%),wheretheligninactsas a “glue” withintheLCCs.58,59 Theactuallignincontentofthe biomassishighlyinuencedbyitsbotanicalorigin e.g.,28–32%

Fig.4 AdaptationofAdler'srepresentationofsoftwood(spruce)ligninwithcolor-codedmonolignols: p-hydroxyphenyl(H-unit)inblack, guaiacyl(G-unit)inblueandsyringyl(S-unit)inred.55

12532 | RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

isfoundinpineandeucalyptuswood,whileswitchgrass containsonly17–18%lignin,60 andlessthan15%istypically foundinannualplants.61 The rststepinligninvalorizationis biomassfractionation,wherethecellulose,hemicellulose,and ligninareseparatedfromeachother.Severaltechniqueshave beendeveloped,whichcanbegroupedintosulfurandsulfurfreepulpingfromthepaperandpulpindustry,andbioreneryprocessesthataimtoproduceofmaterials,chemicals, andenergyfrombiomass.59 Thelattermayspecicallybe designedtoisolateligninofhighpurityandreactivity,whereas pulpingoriginallyproducedligninasaby-orwaste-product.An overviewisgiveninFig.5.

Thethreeindustrialextractionmethodsforligninarekra, sulteandsodapulping.Inaddition,organosolvpulpinghas beendevelopedtoextractligninandseparatethepulp bers. Commercializationofthisprocesshasnotyetbeendone,but interesthasrisenrecentlyinthistechnology,asorganosolv pulpingproducesatechnicalligninofhighpurityandreactivity.Severalothermethodsalsoexist,butthesearemainly usedinlab-scaleandarereferredtoasbioreneryconcepts,or “pretreatments” 62 IntheKra pulpingprocess,thelignocellulosicbiomassismixedwithahighlyalkalinecookingliquid containingsodiumhydroxide(NaOH)andsodiumsulte (Na2S),atelevatedtemperaturesof150–180°C.Fromthe resultingblackliquor,kra lignincanbeprecipitatedoutby loweringthepHtoaround5–7.5.46 IntheLignoBoostprocess, thisprecipitationisdonebyadding rstCO2 andthensulfuric acid.Kra ligninhasasulfurcontentof1–3%,ishighly condensed,containslowamountsof b-O-4linkages,andis frequentlyburnedforenergyandchemicalrecoveryatthe mills.63–65 IntheKra process,ligninisfragmentedthrough aaryletheror b-aryletherbonds,whichresultsinincreased phenolicOHcontentintheresultantlignin.66 Thesulte processisanotherspecializedpulpingtechnique,whichutilizes acookingliquorcontainingsodium,calcium,magnesiumor ammoniumsulteandbisultesalts.65 Treatmentsaretypically conductedat120–180°Cunderhighpressures,whichgives lignosulfonatesthatcontain2.1–9.4%sulfur,mostlyinthe benzylicposition.67 Lignosulfonatesarecleavedmainlythrough

sulfonationatthe a-carbon,whichleadstocleavageofaryletherbondsandsubsequentcrosslinking.68 BothKra and sulteblackliquortypicallycontainsignicantamountsof carbohydrateandinorganicimpurities.64 Thesodaanthraquinoneprocessismostlyappliedinthepaperindustry onnon-woodymaterialslikesugarcanebagasseorstraw.64 The materialistreatedwithanNaOHsolution(13–16wt%)athigh pressuresandtemperaturesof140–170°C,whereanthraquinoneisaddedtostabilizehydrocelluloses.64,69 Theresulting sodaligninissulfur-freeandcontainslittlehemicelluloseor oxidizedmoieties.Organosolvligninisproducedinanextractionprocessusingorganicsolventsandresultsinseparationof dissolvedanddepolymerizedhemicellulose,celluloseas residualsolids,andligninthatcanbeprecipitatedfromthe cookingliquor.65 Varioussolventcombinationsarepossible, suchasethanol/water(Alcellprocess)ormethanolfollowedby methanolandNaOHandantraquinone(Organocellprocess), whichwillaffectstructureoftheresultantmaterials.51 Common forallorganosolvligninsisthattheirstructuresarecloserto thatofnaturallignins,inparticularcomparedtoKra ligninor lignosulfonates.Theyareadditionallysulfur-freeandtendto containlessthan1%carbohydrates.65

Severalothermethodsofbiomassprocessinghavebeen developedthataretargetedatligninextraction,ratherthan producingcellulose bers,whereligninisasabyproduct.64 Milledwoodlignin(MWL)canbeproducedtocloselyemulate nativelignin,butattheexpenseofprocessyields.70 Thismethod isconsideredgentlebuttimeconsuming,oenrequiringweeks ofprocessing,makingitviableonlyinalaboratorysetting.58 Othertechniquesthataimtoproducenativeligninanalogues includecellulolyticenzymaticlignin(CEL)andenzymaticmild acidolysislignin(EMAL).TheCELprocedurewasdevelopedas animprovementoftheMWLprocess,wherehigheryieldswere obtainedwithoutincreasingmillingduration.46 Byaddingan additionalacidolysisstep,Guerra etal. wereabletoagain improveontheyield,whilestillproducingligninthatclosely resembledthenativestructure.70 Thephysicochemical pretreatmentsaimtoreduceligninparticlesizethrough mechanicalforce,extrusion,orother.Thesetechniquesinclude

Fig.5 Ligninextractionprocessesandtheirproducts.3

steamexplosion,CO2 explosion,ammonia berexpansion (AFEX)andliquidhotwater(LHW)pretreatments.46 Ionic liquidshavealsobeensuccessfullyusedforligninisolation. Fivecationswithgoodsolubilizingabilitieswereidentied:the imidazolium,pyridinium,ammoniumandphosphonium cations,whilethetwolargeandnon-coordinatinganions[BF4] and[PF6] werefoundtodisruptdissolutionofthelignin.46 The chosenextractivemethodwillnotonlyaffectthecharacteristics oftheresultinglignin,butalsotheamountthatisextracted. Severalmethodshavebeendevelopedforthedelignicationof sugarcanebagasse, e.g.,milling,alkalineorionicliquid extraction,whereyieldsof17–32%wereobtaineddependingon themethodofchoice.71

2.3.Chemicalmodication

Chemicalmodicationoftechnicalligninsiswellexploredand includeahugevarietyoftechniques(seeFig.6forillustrative examples).Technicalligninshavebeenmodiedbyamyriadof techniques,suchasesterication,phenolationandetherication.6 Urethanizationwithisocyanateshasbeenexplored towardspolyurethanproduction,72 andallylationofphenolic OHgroupsenabledClaisenrearrangementintothe ortho-allyl regioisomerwhichisofinterestforitsthermoplasticproperties.73 Thesolubilityandchargedensityoftechnicalligninscan beaffectedbysulfomethylationorsulfonation,17,74 andmethylationofthephenolicOHgroupshaveledtoligninwithan increasedresistancetoself-polymerization17 Thethermal stabilityofligninshasalsobeenimprovedbysilylatingthe

hydroxylgroupswithTBDMS-Cl,andtheresultingmaterial couldbeincorporatedintolow-densitypolyethylene(LDPE) blendsformingahydrophobicpolymermatrix.75 Ligninis aversatilescaffoldfordifferentmodicationsdependingonthe desiredapplication.Fortheproductionofepoxyresins,epoxidationwithepichlorohydrinisacommontechnique.This approachhasalsobeencombinedwithCO2 xationresultingin cycliccarbonatesbeingincorporatedinthelignin.76

2.4.Analysistechniques

Techniquestoassessligninsandlignocellulosicbiomasshave longbeenatopicofgreatinterest,bothforquantitativeand qualitativecharacterization.Suchtechniquesarealsocriticalto probeandassesschemicalmodications.Asummaryof commonmethodsisgiveninTable1.

Differenttechniquesareoencombinedtoprovideabetter overallpicture.Forexample,chemicalmodicationoflignin maybeprobedintermsofmolecularweight, i.e.,byusingsizeexclusionchromatography,andabundanceoffunctional groups,asdeterminedbyFTIRor2DNMRanalysis.Thetechniqueofchoicecandependonfactorssuchasthetargetgroups ofinterest,butalsoonavailabilityandcost.Thepolydisperse natureoftechnicallignincansometimesmakeaccurate measurementsdifficult.Thisismanifested,forexample,inthe incompleteionizationofphenolicmoietiesduringtitrationor UVspectrophotometry,asthecongurationandsidechainsof phenolicmoietiesinducevaryingdegreesofresonance stabilization.

Fig.6 Examplesofchemicalmodificationsoftechnicallignin. 12534 | RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Table1 Characterizationtechniquestoassessligninsquantitativelyandqualitatively

MethodDescriptionLimitationsRef.

FTIRspectroscopyPopulartechniquetocombinewith chemometricmethodssuchas principalcomponentregression (PCR)orpartialleastsquares(PLS) regression.Havebeenusedfor successfullydetermininglignin contentinbiomasssamples

1H/13C2DNMRExtremelydetailedinformation aboutinter-unitlinkagescanbe obtained.Hasallowedforthe assignmentandquanticationof over80%oflinkagesinligninoil fromreductivecatalytic fractionationofpinewood

31PNMRDifferentiationofthephenolicOH contentofthethreemonolignolsis possiblefromexperimentsaer derivatizationoftheOHgroups

UV-visspectroscopyCruderdeterminationofphenolic OHcontentispossibleby comparingthedifferencesin absorptionatspecicmaxima betweenneutralandalkaline solutions

Simultaneousconductometricand acid–basetitrations

Sizeexclusionchromatography (SEC)

Gaschromatography – pyrolysis (GC-Py)

Coherentanti-StokesRaman scattering(CARS)microscopy

Time-of-ightsecondaryionmass spectrometry(ToF-SIMS)

Afastandcheapalternativetowetchemicalmethodsfordetermining bothphenolicOHgroupand carboxylicacidcontents

Populartechniqueforobtaining weightandnumberaverage molecularweights, Mw and Mn,and forfurthercalculatingthe polydispersityindex(PI)ofsamples

Analysisofbiomasscomposition, quanticationofvolatiles,bio-oil andbiochar.Canbecoupledwith TGAandFTIR.

Label-freemethodwithhigh sensitivityandchemicalselectivity forimagingofligninin e.g. plant cellwalls

Visualizationofmonolignol distributiononplantsamplecrosssections

3.Formulationsandapplicationsof lignin-basedsurfacesandcoatings

Thecoatingsandsurfacemodicationsinthisreviewmost oenfullloneoftwopurposes.Firstly,theymayseekto protecttheunderlyingsubstrate, e.g.,frommechanicalwear, chemicalattack(corrosion),orUVradiation.Secondly,theyadd functionalitysuchasantioxidant,controlledsubstancerelease, orantimicrobialproperties.Reducedwettingand

©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Calibrationrequiredwithsamples ofknownconcentrations.Large dataset(trainingandtestsets) neededforreliablequantication. Trainingsamplesandprediction samplescannotdiffergreatly.

Analysesaresensitivetosample preparationtechniques

NMRexperimentsareexpensive, instrumentsfoundatspecialized institutionsanduniversities.Both experimentsanddataprocessing canbehighlytime-consuming

FullderivatizationofOH-groupsis essentialforproperquantication. Inversegateddecouplingpulse sequenceneededforquantication: reducedsensitivityandincreases relaxationtimeofanalysis

Lessaccuratethan 31PNMR. Affectedbyincompleteionizationof functionalgroups.Presenceofother ionizablegroupscanaffectresults

HeterogeneityofCOOH-andOHgroupsdistortsinectionpoint. LimitedtoquanticationofCOOHandOH-groups(andpossiblyother ionizablegroups)

Timeconsumingcalibration required.Samplesmustbewithin linearrange.Acetylationisoen usedforincreasedsolubilitypriorto analysis

78and79

78

78and80

81and82

78and83

Variationsininherentmetal contentsgreatlyaffectsthepyrolysis reactionofthebiomass 84and85

Interferencefromotheraromatic compounds(phenylalanine, tyrosine)candistortimage.Not suitedforimagingalltissuetypes 58and86

Pronetoartefact-generationarising fromsamplepreparation.

Fragmentationofligninduring imagingduetohigh-energyion bombardment

hydrophobizationarefrequentlymentionedforlignin,34,77,78 whichwouldnormallyfallintothesecondcategory,unlessthe purposeistoprotecttheunderlyingsubstratefromdegradation bywater.Thedifferentapplicationswillbediscussedmorein detailinthischapter.

Theend-useusuallydeterminesthemanner,inwhich mixturesandcoatingsmustbeformulated.Inprinciple,four differentapproachescanbedistinguished,whichare(1) applicationofneatlignin,(2)blendsofligninwithotheractive

Overviewofdifferentapplicationmodesforproducingfunctionalsurfacesandcoatingswithlignin.

orinertmaterials,(3)theblendingoflignininthermoplastic materials,and(4)theuseofligninasaprecursorforsynthesizingthermosetpolymers.Anoverviewofthedifferent approachesforformulationandapplicationisgiveninFig.7. Thesewillbediscussedinmoredetailfurtheron.

Whilesurfacelayerorcoatingareusuallyappliedonto anothermaterial,therearealsoimplementationsthatinclude ligninaspartoftheoverallbase-matrix.Examplesforthelatter includelignin-derivedbiocarbonparticlesforCO2 captureor wastewatertreatment,polyurethanefoams,andligninasan internalsizingagentinpulpproducts.36,43,79,80 Thepredominant wayofusinglignininfunctionalsurfacesisbyblendingwith othersubstances.Suchformulationsoenincludeagents, whichareestablishedforaparticularapplication, e.g.,starch forpapersizingorclayforcontrolled-releaseureafertilizers.81,82

Formulationsinpolymersynthesisusuallydrawonspecic functionalgroupsthatarefoundinlignin,forexample,the hydroxylgroupsaspolyolreplacementinpolyurethaneorthe aromaticmoietiesasphenolreplacementinphenolformaldehyderesins.18,33

3.1.Surfacesandcoatingswithneatlignin

Applyingtechnicalligninbyitselfisasimpleapproach,asno co-agentsarerequired.Whilesomedegreeofadhesiontothe substrateisoengiven,pressureandheatmaybeappliedin addition.Publicationspertainingtothistopiccanbegrouped intotwocategories, i.e.,fundamentalresearchstudyingthe formationandpropertiesoflignin-based lmsandcoatings,as wellasappliedresearch,whichisusuallyfocusedonaspecic end-use.

3.1.1.Fundamentalresearch. Afundamentalstudywas performedbyBorrega etal.,whopreparedthinspin-coated lmsfromsixdifferentligninsamplesinaqueousammoniummedia.83 The lmsexhibitedhydrophilicitywithcontact

anglesrangingfrom40–60°.Despitewidelydiversecompositions,thesolubilityinwaterwasfoundtobetheparameter governingthepropertiesofthethin lms.Similarresultswere obtainedbyNotleyandNorgren,whofoundthatlignincoatings preparedfromdiiomethaneorformamideyieldedevenlower contactanglesatabout20–30°.34 Theapproachwasfurther renedbySouza etal.,whotreatedthespin-coatedlignin lms via UVradiationorSF6plasmatreatmentinaddition.84 While theUVtreatmentreducedthecontactanglefromabout90°to 40°,theplasmatreatmentproducedsuperhydrophobicsurfaces withcontactanglesexceeding160°.Thelatterwasalsoshownto inducemajorsurfacerestructuringwithastrongincorporation ofCFx andCHx groups,whichwouldaccountforthelarge increaseincontactangle.Coatingswithlignin-basednanoparticlescanalsobemadebyevaporation-inducedselfassembly,whosepropertiesandmorphologyarestronglygovernedbythedryingconditionsandevaporationrate.85 An exampleoftheobtainedmorphologiesisshowninFig.8.Based onthesereports,researchisgenerallyconcurringonthefact thatligninbyitselfisnotahydrophobicsubstance.Harsh treatments,chemicalmodications,or ne-tuningofsurface morphologyarenecessarytoinvokehydrophobicity.

Spin-coated lmsofmilled-woodligninhavefurthermore beeninvestigatedforenzymeadsorption.86 Similarly,the adsorptionofproteinsoncolloidalligninhasbeenstudiedby Leskinen etal.,whoproducedproteincoronasonthelignin particles via self-assembly.87 Theauthorsfurthershowedthat thisdepositionwasgovernedbytheaminoacidcompositionof theprotein,aswellasenvironmentalparameterssuchasthepH andionicstrength.Theuseofligninforprotein-adsorptionis aninterestingimplementation,asitcanprovidedifferent surfacechemistriesthanitslignocellulosiccounterparts.Still, thecompatibilitywith invivo environmentsisquestionable,as biodegradationisnotgivenhere.

Fig.7

3.1.2.Appliedresearch. Anexampleforappliedresearch wouldbepaperandpulpproducts,whichcanberenderedless hydrophilicbysurface-sizing.Applicationofthelignincanbe done via anaqueousdispersionoralternativelybyimpregnationaerdissolutioninasolvent.35,88 Asimilarapproachwas usedtotreatbeechwoodwithligninnanoparticle via dipcoating,whichimprovedtheweatheringresistanceofthe wood.89 Suchdip-coatingmaypreservebreathabilityofthe substrateduetotheporousstructure.Inthiscontext,thepatent applicationWO2015054736A1shouldbementioned,which disclosesawaterproofcoatingonarangeofsubstrates includingpaper.90 Inthisinvention,theligniniscoatedonto thesubstrateaeratleastpartialdissolution,followedbyheat oracidtreatment.However,asdiscussedabove,theligninby itselfisnotahydrophobicmaterial.Whilelignin-nanoparticles mayalterthesurfacemorphologyofpulpproducts,an improvementinlong-termwater-resistancemaybemostly determinedbyaffectingmass-transferkinetics.

Depositionoflignosulfonatesonnylonhasbeendemonstrated,whichimprovedtheultravioletprotectionabilityofthe fabric.91 Thisdepositiontookplacefromaqueoussolutionand underheating,reportedlyyieldingachemicalbondingof lignin'sOHgroupstotheNHgroupsofnylon6.Suchbonding wouldindeedbenecessary,asthelignosulfonatewouldotherwisebeeasilywashedaway.

Zheng etal. coatedmicrobrillatedcellulosewithKra ligninandsulfonateKra lignin,whichpromoted reretardancyofthematerial.42 Atlast,iron-phosphatedsteelwas renderedmoreresistanttocorrosionaerspraycoatingwith lignin,whichwas rstdissolvedinDMSOandothercommerciallignin-solvents.92 Whileproveninthelab,thesetwoapplicationsmustbeconsideredwithcare,asunmodiedligninis abrittlematerial,whichcanlimitthelong-termdurabilityof suchproducts.

3.2.Theuseofchemicallymodiedlignin

Chemicalmodicationofligninisfrequentlydonetoimprove orenabletheprocessabilityinblendswithmaterials.Inaddition,chemicalmodicationmayaddoralterfunctionalitiesas requiredinspecicapplications.

3.2.1.Lignin-esterderivatives. Estericationofligninwith fattyacidshasbeeninvestigatedbyseveralauthors.This approachbearspotential,asitcombinedtwobio-derived (macro-)molecules.Thelignincontributesabackbonefor graingandmayimprovedispersibilityandadhesionofthe fattyacidsonlipophobicsurfaces.Thefattyacidscaninturn rendertheligninmorehydrophobic,improvingthewater barrier, e.g.,onpapersubstrates.Toimprovethereactionyield, reactiveintermediatesarefrequentlyused.Severalpublications havestudiedtheuseofligninesteriedwithfattyacid-chlorides ashydrophobizationagentsforpaperandpulpproducts.78,93 Thecoatingaffectedboththesurfacechemistryand morphology,asillustratedinFig.9.Theresultisusually adecreaseinwater-vaportransmissionrate(WVTR),oxygen transmissionrate(OTR),andanincreaseinaqueouscontact angle.Oxypropylationwithpropylenecarbonatehasbeenused asanalternativeestericationapproach,whichyielded asimilarhydrophobizationandbarriereffectonrecycled paper.94 Adownsideofoxypropylationistheuseoftoxicreactants, i.e.,propyleneoxide,andtherequirementforhighpressureduringthereaction.Whilefattyacidchloridesdonotneed highpressures,thesechemicalsarehighlycorrosiveandrequire theabsenceofwater.Allmentionedaspectscanstandinthe wayofcommercialimplementation.

Hua etal. reactedsowoodKra ligninwithethylene carbonatetoconvertphenolichydroxylunitstoaliphaticones,95 astheseareconsideredmorereactive.Thesampleswerefurther esteriedwitholeicacidandspin-orspray-coatedontoglass, wood,andKra pulpsheets.Theauthorsshowedthathydrophobicsurfaceswithcontactanglesrangingfrom95–147°were possible.Thepulpboardsfurthermoreshowedamoreuniform surfaceaerthecoating.Estericationwithlauroylchloride wasalsousedbyGordobil etal.,whostudiedtheirapplication aswoodveneerbypress-moldinganddip-coating.96

Whilethefeasibilitytotreatwoodandwood-basedproducts wasdemonstratedonatechnologicallevel,thecomparisonto establishedtreatmentagentsisfrequentlylacking.Forexample, linseedoilisanestablishedwood-treatmentagent,which undergoesself-polymerizationinthepresenceofair.Papersizingagentscanbebasedoncompoundsthataresimilarin

Coatingscomprisingligninparticlesproducedbyevaporation-inducedself-assembly(a)andverticalcross-sectionoftheobtainedlayers (b).85 ©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Fig.8

functiontofattyacids,suchasresinacidsoralkenylsuccinic anhydride.Consideringtheseexamples,thequestionsarises whethermodifyingligninbearsanadvantageoverusing establishedcoatingsorsizingagents.Inthelightofthis discussion,theacid-catalyzedtransestericationofligninwith linseedoilshouldbementioned.77 Accordingtotheauthors, asuberin-likelignin-derivativewasproduced,whichintroduced hydrophobicityonmechanicalpulpsheets,whilebeingmore compatiblewiththe bersthanlinseedoilalone.Theproposed processissimpleinsetupandreactants,whichfacilitatesease ofimplementation.Inaddition,theligninisprescribedakey function, i.e.,actingasacompatibilizerbetweenthe bersand thetriglycerides.

Atlast,controlled-releasefertilizerswithlignin-fattyacid gra polymershavebeenproposed.Wei etal. crosslinked sodiumlignosulfonatewithepichlorohydrin,followedby estericationwithlauroylchloride.97 Sadehi etal. reacted lignosulfonatewithoxalicacid,proprionicacid,adipicacid, oleicacid,andstearicacid.98 Themodiedligninwasfurther usedtospray-coatureagranules.Bothimplementations showedenhancedhydrophobicityandtheabilitytocoaturea forslowerreleaseofnitrogen.Still,itwouldbeimportantto comparesuchapproacheswithestablishedcoatingorblendsof ligninandnaturalwaxesortriglycerides,whichdonotrequire anelaboratedsynthesis.

3.2.2.Enzymaticmodication. Enzymaticmodicationof ligninhastheadvantageofcomparablymildreactionsconditions,whichcanhaveapositiveimpactonprocesseconomics. Onthedownside,enzymesarecomparablyexpensiveand imposeshighertechnologicaldemands.Inaddition,thevariety oflignin-compatibleenzymesissomewhatlimited.Enzymatic treatmentcaninduceanumberofchangestolignin,suchas oxidation,depolymerization,polymerization,andgraingwith othercomponents.99 Forexample,Mayr etal. coupledlignosulfonateswith4-[4-(triuoromethyl)phenoxy]phenolusing laccaseenzymes.100 Aersuccessfulcoupling,thelignosulfonate lmsexhibitedreducedswellingandanincreasein aqueouscontactangle.Fernandez-Costas etal. performed laccase-mediatedgraingofKra ligninonwoodasapreservativetreatment.101 Whilethereactionitselfwasdeemed asuccess,thedesiredantifungaleffectwasonlyobtainedaer inclusionofadditionaltreatmentagents,suchascopper.Itis hencequestionableifenzymaticallycoupledligninposesas acompetitivewood-treatmentagent,asthelignincouldalsobe

usedinwood-varnishformulationswithahighertechnological maturity.

3.2.3.Otherapproaches. Avarietyofothermodications hasbeenproposedtodevelopcoatingsfromlignin.For example,Dastpak etal. reactedligninwithtriethylphosphateto spray-coatiron-phosphatedsteelforcorrosionprotection.44 CoatingofaminosilicagelwithoxidatedKra ligninwasperformedbyelectrostaticdeposition,whichimprovedthe adsorptioncapacityfordyesfromwastewater.102 Wang etal. phenolatedlignosulfonate,followedbyMannichreactionwith ethylenediamineandformaldehydetoproduceslow-release nitrogenfertilizers.103 The nalproductexhibitedelevated contactangles,however,anincreasedsurfaceroughnesslikely alsocontributedtothiseffect,asthephenolatedandaminated ligninexhibitednanoparticlestructures.Adifferentapproach wastakenbyBehinandSadeghi,whoacetylatedligninwith aceticacidtocoatureaparticlesinarotarydrumcoater.104 The useoflignininslow-releasefertilizerscanbeuseful,aslignin canhaveasoil-conditioningeffect.However,biodegradability alsomustbeconsidered,whichcanbenegativelyaffectedby chemicalmodication.

Self-healingelastomersweresynthesizedbyCui etal.,who graedligninwithpoly(ethyleneglycol)(PEG)terminatedwith epoxygroups.31 Theauthorsconcludedthatanewmaterialwas developedwithpotentialapplicationforadhesives,butthe ultimatestresswascomparablylowat10–12MPa.Thematerial wasnamedasaself-healingelastomer;however,theappearanceandrheologicalpropertiessuggestathixotropicgel instead.

3.3.Blendsofligninwithothersubstances

Inthecontextofthisreview,thelargestnumberofpublications wasfoundforlignin-blendswithothersubstances.Theadvantageofthisapproachliesintheeaseofimplementation, exibilityforlateradjustments,andpotentialsynergieswithother co-agents.Theligninandotheradditivesmaybemixedright beforeorduringsurfacemodication,hencenotrequiring lengthypreparationssuchasthesynthesisofchemically modiedligninorapre-polymer.Tofacilitatebetteroverview, thissectionwassubdividedintoseveralsub-section,whichwere distinguishedbytheapplicationareaorformulation-approach.

3.3.1.Cellulose bersandotherwood-basedproducts. The useofligninincombinationwithcellulose bers, brils,or derivativeshasreceivedconsiderableattention,asthiscanyield

Fig.9 SEMimagesof(a)uncoatedpaperboardand(b)paperboardcoatedwithlignin-fattyacidester.This figurehasbeenadapted/reproduced fromref.78withpermissionfromElsevierB.V.,copyright2013. 12538 | RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

all-biobasedmaterialsandcoatings.Forexample,eucalyptus Kra ligninandcelluloseacetatewerecombinedinsolution andcastontobeech-wood,whichproducedaprotectivecoating similartobark.37 However,theauthorsdidnotdeterminethe mechanicalpropertiesoftheproduct,whichwouldbeimportanttoaddress,asthepotentialbrittlenesscouldimpartpracticaluse.Ontheotherhand,thebiodegradationofligninis indeedmorechallengingthanthatofcelluloseandhemicellulose,105 whichmayhencecontributetoanimprovedresistanceagainstcertainfungiandbacteria.Inaddition,theligninbasedveneermayaddfunctionalitiessuchaswater-repellence, UV-protection,andimprovedabrasionresistance,106 butstill acomparisonwithestablishedtreatmentagentsislacking.

Cellulosenanobrils(CNF)and(cationic)colloidallignin particleswascastinto lmsbyFarooq etal.,yieldingimproved mechanicalstrengthascomparedtotheCNFalone.107 AschematicoftheproposedinteractionsisgiveninFig.10.The authorsconcludedthattheligninparticlesactedaslubricating andstresstransferringagents,whichadditionallyimprovedthe barrierproperties.Thediscussedeffectscouldalsobeinduced bytheligninactingasabinder,hence llinggapsandproviding anoveralltighternetwork.36,88 Riviere etal. combinedligninnanoparticlesandcationicligninwithCNF,however,the oxygenbarrierandmechanicalstrengthwerelowerthanthe CNFwithoutaddedlignin.108 Thiseffectwaslikelydueto adisruptionofthebindingbetweenCNFnetworks.Thepolyphenolicbackboneofligningenerallyprovideslessopportunitiesforhydrogenbondingthancomparedtothecellulose macromolecule.Theauthorsworkonsolventextractionof ligninfromhydrolysisresiduesisnoteworthy,however,andthe workshowedpromisingpotentialforantioxidantuse.

LCCwerecombinedwithhydroxyethylcellulose,producing free-standingcomposite lms.109 Inthisstudy,theadditionof LCCenhancedtheoxygenbarrierpropertiesandcouldalso improvethemechanicalstabilityandrigidity.Abettereffectof LCCwasnotedthancombininglignosulfonateswithhydroxyethylcellulosealone.Synergiescouldhencearisefromcarbohydratesthatarecovalentlybondontothelignin.

AninterestingapproachwastakenbyHambardzumyan etal.,whoFenton'sreagenttopartiallygra organosolvlignin

ontocellulosenanocrystals.110 Theproductwascastintothin lms,whichshowednanostructuredmorphologieswith increasedwaterresistanceandtheabilitytoformselfsupportedhydrogel-lms.Inanotherpublication,Hambardzumyan etal. simplymixedthecellulosenanocrystalswith lignininsolution,aerwhich lmswerecastontoquartzslides anddriedbyevaporation.111 Theauthorsfoundthatoptically transparent lmswithUV-blockingabilitycouldbeproduced.It wasconcludedthatincreasingtheCNFconcentrationallowed forbetterdispersionoftheligninmacromolecules,dislocating the p–p aromaticaggregatesandhenceyieldingahigher extinctioncoefficient.

Anelaborateworkonlignin-starchcomposite lmswas conductedbyBaumberger.39 The lmswereproduced via oneof twomethods:(1)powderblendingofthermoplasticstarchand lignin,followedbyheatpressingandrapidcooling,and(2) dissolutioninwaterordimethylsulfoxidefollowedbysolventcastingandsolventevaporation.Theauthorconcludedthat theligninactedeitheras llerorasextenderofthestarch matrix,wherethecompatibilitywasfavoredbymediumrelative humidity,highamylopectin/amyloseratios,andlowmolecular weightlignin.Lignosulfonatesformedgoodblendsand impartedahigherextensibilityontothestarch lms,likelydue tobenecialinteractionsbetweensulfonicandhydroxylgroups. Non-sulfonatedlignin,ontheotherhand,improvedwaterresistancetoagreaterextent.

Threerecentstudieshavefoundthatincorporatinglignin intoamoldedpulpmaterialscanreducethewettabilityofthe material,aswitnessedbyanincreaseincontactangleor adecreaseinwater-uptake.8,36,88 Theadvantageofsuchimplementationisthathightemperatureandpressurewillpromote densication,asthelignincan owintocavities.Highdensities ofupto1200kgm 3 werereported,wheretheuptakeofwateris hinderednotonlybylimitingmass-transport,butalsoby conningtheswellingofcellulose bers.88

Variousresearchershaveincludedligninintheformulation ofpaper-sizingagents.Inoneimplementation,Javed etal. blendedKra ligninwithstarch,glycerol,andammonium zirconiumcarbonatetoproduceself-supporting lmsand paperboardcoatings.112 Themechanical lmstabilitywasbetter

Fig.10 SchematicillustrationofproposedinteractionbetweenCNFanddifferentligninmorphologies.107

whenusingammoniumzirconiumcarbonateasacross-linking agent,inadditiontoreducingthewater-transmissionrate.Both theligninandtheammoniumzirconiumcarbonatealso reducedleachingofstarchwhenincontactwithwater.In asecondpublication,theauthorfurtherdevelopedtheformulation'suseinpilottrials.81 Johansson etal. coatedpaperboard, aluminiumfoil,andglasswithmixturesoflatex,starch,clay, glycerol,laccaseenzyme,andtechnicallignin.113 Theauthors foundthattheoxygenscavengingactivitywasgreatestfor lignosulfonates,ascomparedtoorganosolv,alkaliorhydrolysis lignin.Thiseffectwasexplainedbyagreaterabilityofthelaccasetointroducecross-linkingonthelignosulfonatemacromolecules.Inanotherpublication,Johansson etal. also combinedlignosulfonateswithstyrene-butadienelatex,starch, clay,glycerol,andlaccaseenzyme.114 Theresultsshowedthat bothactiveenzymeandhighrelativehumiditywerenecessary forgoodoxygenscavengingactivity.Laccase-catalyzedoxidation oflignosulfonatesfurthermoreresultedinincreasedstiffness andwater-resistanceofthestarch-based lms.Winestrand etal. preparedpaperboardcoatingsusingamixtureoflatex,clay, lignosulfonates,starch,andlaccaseenzyme.115 The lms showedimprovedcontactanglewithactiveenzymeandoxygenscavengingactivityforfood-packagingapplications.Whilethe resultsforpaper-sizingwithadditionofligninshowpromising potential,foodpackagingapplicationsmayimposeadditional requirements.Forexample,stabilityofthecoatingsmaynotbe giveninenvironmentsthatcontainbothmoistureandlipids.In addition,tothebestofourknowledge,nostudyaddressedthe migrationofsizing-agentsintofood.Still,theutilizationof ligninasoxygenscavengerispromising,asthisutilizesoneof ligninsinherentproperties,whicharefoundinfewother biopolymers.

Asanalternativetotechnicallignin,Dong etal. applied alkalineperoxidemechanicalpulpingeffluentinpaper-sizing, whichcomprised20.1wt%ligninand16.5wt%extractives basedondrymatterweight.116 Blendedwithstarch,theeffluent improvedthetensileindexandreducetheCobbvalueofpaper, whileprovidingcontactanglesof120°andhigher.Such implementationcan,however,alsoaggravatecertainproperties

ofthepaper,asagingandyellowingmaybepromotedbythe presenceofacidsandchromophores.

Layer-by-layerself-assemblywasusedbyPeng etal. to producesuperhydrophobicpapercoatedwithalkylatedlignosulfonateandpoly(allylaminehydrochloride).40 Alternatively, Lit etal. depositedsuchlayersoncellulose bersbycombining lignosulfonateswiththedivalentcoppercationinsteadof apolycation.41 Asimilareffectonsurfacemorphologywas noted,whilecontactangleswithinthehydrophobicregime couldbeachieved.Theutilizationoflignosulfonate-polycation assembliesforcellulosehydrophobizationissomewhatcounterintuitive,sincepolyelectrolytecomplexestendtobehydrophilicandcanswellinwater.Thelong-termstabilityofsuch coatingsinwaterishencequestionable,stillforshortcontact timesthemodulationofsurfaceroughnessandchemistrycan bebenecial.

SolventcastingwasemployedbyWu etal.,usingionic liquidstodissolvecellulose,starch,andlignin.117 Thebiopolymerswerecoagulatedbyadditionofthenon-solventwater, furtherbeingprocessedinto exibleamorphous lms.The processappearssimilartotheproductionofcelluloseregenerates.Utilizingotherbiopolymersthancellulose, i.e.,lignin, hemicellulose,andstarch,isaninterestingapproachfor netuningthedesired lmproperties.

Zhao etal. usedevaporationinducedself-assemblyoflignin nanoparticlesandCNF,whichweresubsequentlyoxidizedat 250°Candthencarbonizedat600–900°C.79 Thesenano-and micro-sizedparticlescouldbeusedforCO2 adsorption,where synergisticeffectsbetweentheCNFandligninnanoparticles werenoted.AnillustrationoftheparticlesisshowninFig.11. Agrochemicalformulationswithlignin-basedcoatings predominantlyinvolvefertilizerformulations, i.e.,for controlledreleaseofnutrients.Thelignincanbepartof acoating,whichthenactsasamass-transferbarrierthatdelays thedissolutionofnutrients.82,118,119 Thefocusisusuallyonurea asnitrogenfertilizerorcalciumphosphateassuperphosphate fertilizers.82,118–120 Anadvantageofusinglignin,apartfrom beingbiodegradableandwater-insoluble,isthepotential functionassoilamendment.121

Fig.11 Lignin-basedporousparticlesobtainedbyoxidationandcarbonizationforcarboncapture.SEMimagesofligninparticlescarbonizedat low(a)andhigh(b)pre-oxidationrate,yieldingtwodistinctmorphologies.This figurehasbeenadapted/reproducedfromref.79withpermission fromElsevierB.V.,copyright2017.

12540 | RSCAdv.,2023, 13,12529–12553©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Twoapproachescangenerallybedistinguished,basedon eithertheuseofneatorchemicallymodiedlignin.Properties suchaswater-permeabilityandnitrogenorphosphorrelease canbepositivelyaffected;however,chemicalmodicationmay impairbiodegradation.Withthatsaid,theworkofFertahi etal. shouldbenoted,whocoatedtriplesuperphosphatefertilizers withmixturesofcarrageenan,PEG,andlignin.118 Thelatterhad beenobtainedfromalkalipulpingofolivepomace.Thethree mentionedcoating-materialsareinprincipleallbiodegradable. BlendingligninwithcarrageenanorPEGimprovedthe mechanicalstabilityofthe lmscomparedtoligninalone, whilealsoincreasingtheswellingofthecoatings.Similar blendswerestudiedbyMulder etal.,whofoundthatglycerolor polyolssuchasPEG400couldimprovethe lmformingproperties.120 Thewaterresistance,ontheotherhand,wasimproved byusinghighmolecularweightPEGorcrosslinkingagentssuch asAcronalorStyronal(commercialname).Onthedownside, thebiodegradabilitywillbenegativelyaffectedbysuchcrosslinkingagents,especiallyacrylatesorstyrene-based chemistries.

ChemicalmodicationofligninforcoatingofsuperphosphatefertilizerswasalsoconductedbyRotondo etal., 119 where thetechnicalligninwaseitherhydroxymethylatedoracetylated. Apartfromutilizingtoxicchemicalsinthesynthesis,these modicationsalonedonotposeasadetrimenttobiodegradability.However,theRotondo etal. alsosynthesizedphenolformaldehyderesintocoatthefertilizercores,whichcouldbe troubling,astheauthorsbasicallysuggestedaddingplasticsto thesoil.Zhang etal. furthermoremodiedligninbygraing quaternaryammoniumgroupsontoit.82 Whilethequaternary ammoniummayconvenientlybindanionsandaddnitrogento thesoil,someofitsdegradationproductsarehighlytoxicand henceconcerning,unlessthegoalistoaddbiocidestothesoil. AsimilarapproachwasdonebyLi etal., 14 whosynthesized multifunctionalfertilizers.First,alkaliligninandNH4ZnPO4 weremixedanddissolvedtoproducefertilizercores,which werefurthercoatedwithcelluloseacetatebutyrateandliquid paraffin.Asecondcoatingwasthenappliedasasuperabsorbent,whichwasbasedonalkaliligningraedwithpoly(acrylic acid)inablendwithattapulgite.Boththeparaffinandpoly(acrylicacid)gra shouldhavebeenavoidedduetoenvironmentalincompatibilities.

Atlast,adifferentapplicationwasexploredbyNguyen etal., i.e.,theencapsulationofphoto-liablecompoundswithalignin coatinglayer.122 Inparticular,theauthorsemulsiedthe insecticidedeltamethrininacornoilnanoemulsionwith polysorbate80andsoybeanlectinasemulsier.Thedroplets werefurthercoatedwithchitosanandlignosulfonate.The lignincontributedherebytoboththeUV-protectionofthe emulsiedinsecticide,aswellastoitscontrolledrelease.This approachispositiveinseveralregards,asonlybiobasedagents wereusedintheformulation,thelignosulfonateswerenot chemicallymodied,andtheapplicationdrewonsomeof lignin'sinherentproperties.

3.3.2.Biomaterialsandbiomedicalapplications. A biomaterial, i.e.,amaterialintendedforuseinoronthehuman body,mustcomplywithcertainrequirements.Thisimpliesthat

thematerialshouldbebiocompatibleandshouldnotcausean unacceptableeffectonthehumanbody.123 However,thedenitionofbiocompatibilityhasbeendebatedintheliterature.In additiontoamodieddenitionof “biocompatibility”,Ratner proposed “biotolerability” todescribebiomaterialsinmedicine.124 Biocompatibilitywasdenedby “theabilityofamaterial tolocallytriggerandguidenonbroticwoundhealing,reconstructionandtissueintegration”,whilebiotolerabilitywas proposedtobe “theabilityofamaterialtoresideinthebodyfor longperiodsoftimewithonlylowdegreesofinammatory reactions”.Novelbiomaterialsdevelopedforbiomedicalapplicationscouldbedenedbythesetermswiththetargetof limited broticreactions,125 andligninmaybewithinthisgroup ofbiomaterials.Ligninisamaterialderivedfrombiobased resources,withattractivepropertiesforbiomedicaluse, primarilywithantioxidantandantibacterialcharacteristics. Theantioxidantpropertyofligninisdependentonthephenolic hydroxygroupscapableoffree-radicalscavenging.Theantimicrobialeffectisalsocausedbythephenoliccompounds.126 As expected,theantibacterial,antioxidantandcytotoxicproperties mayalsodependonthetypeoflignin.127,128 Forexample,kra ligninhasbeenfoundtohavelessantibacterialproperties comparedtoorganosolvligninduetothelargermethoxyl contentinorganosolvlignins.127

Severalauthorshaveattemptedtodrawonlignin'santibacterialandantiviralproperties,whichcouldbeusefulinsurfaces forbiomaterialsandbiomedicalapplications.Antimicrobial coatingswere,forexample,preparedbyLintinen etal.via deprotonationandionexchangewithsilver,129 asshownin Fig.12.Jankovic etal. alsodevelopedsuchsurfacesby ashfreezingadispersionoforganosolvligninandhydroxyapatite withorwithoutincorporatedsilver.130 Aerfreezing,the samplesweredriedbycryogenicmultipulselaserirradiation, producinganon-cytotoxiccomposite,whichwerefurthertested ontheirinhibitoryactivity.Asimilarapproachwastakenby Erakovi´ c etal.131 Theauthorspreparedsilverdopedhydroxyapatitepowder,whichwasthensuspendedinethanolwith organosolvligninandcoated via electrophoreticdeposition ontotitanium.131 Thiscompositeshowedsufficientreleaseof silvertoimposeantimicrobialeffect,whileposingnon-toxicfor healthyimmunocompetentperipheralbloodmononuclearcells attheappliedconcentrations.However,theuseofsilverhas causedsomeenvironmentalconcernsthatshouldbe addressed.132 Asanalternative,copperhasbeenreportedwith betterantibacterialeffectthansilver,whichtoourknowledgeis currentlyunexploredinantimicrobiallignincomplexes.133

Lignin-titaniumdioxidenanocompositeswerepreparedby precipitationfromsolutionandtestedfortheirantimicrobial andUV-blockingproperties.134 Theauthorsconcludedthatthe lignincouldfunctionasthesolecappingandstabilization agentforthetitaniumdioxidenanocomposites.Betterperformanceofthenanocompositesforantioxidant,UV-shielding, andantimicrobialpropertieswasreported,ascomparedto theligninortitaniumdioxidealone.

Kra ligninandoxidizedKra ligninwereprocessedinto colloidalligninparticlesandcoatedwith b-casein,whichwas furthercross-linked.29 Thisworkaimedtoproducebiomaterials ©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

Simplifiedschematicoftheproductionofsilver-dopedligninnanoparticles.129

andbio-adhesives,wherethecolloidalligninactedasthescaffoldintendedforthesynthesisofbio-compatibleparticles. However,noassessmentofbiocompatibilityofthegenerated complexeswasperformed.Hence,thequestionremains whetherthisapproachmaybesuitableforbiomedical applications.

AccordingtoDominguez-Robles,therearevariousadditionalbiomedicalapplications,inwhichlignincouldbe promising, e.g.,ashydrogels,nanoparticlesandnanotubes,for woundhealingandtissueengineering.135 Theinterestinlignin forbiomedicalapplicationswasalsoemphasizedbythe increasingamountofpublicationsrelatedtoligninappliedas afunctionalmaterialfortissueengineering,drugdeliveryand pharmaceuticaluse.135,136 However,thereportedstudieson ligninforbiomedicalapplicationsisstilllimitedandvarious challengeswillneedtobeovercometoadvanceinthisarea. Theseareespeciallyregardingrelevantassessmentoflignins toxicologicalproleandbiocompatibility.Nottomentionthe largevariabilityofligninswhenitcomestothesourceoflignin, thefractionationprocessesandposteriormodication,which mayaffectthechemicalstructure,homogeneity,andpurity.

3.3.3.Wastewatertreatment. Differentresearchershave formulatedlignin-basedmaterials,whichweredesignedforthe puricationofdyecontainingwastewater.16,102,137 Suitabilityfor suchapplicationsisprincipallyderivedfromthechemical similarities,whichexistbetweenligninandmanydyes, i.e.,an abundanceofheteroatomsandaromaticmoieties.Such adsorbentscanbeproduced via depositiononsilicagel,102 coatingontocarbonparticles,16 carbonization,43 sorptionand co-precipitation.138 Developmentofsuchmaterialsisgenerally positive,asitdrawsontheuniquecompositionoflignin.

Adifferenttechnologicalapproachwithinthesamearea wouldbemembranes.Layer-by-layerassemblyisafrequently usedtechnique,inwhichpolyanioniclignosulfonatesor sulfonatedKra ligninarecombinedwithapolycation. Multiplebilayersaremadebystepwiseapplicationofthepolyelectrolytes, e.g.,byimmersioninasolutionofpolyanion rst, followedbydryingandimmersioninasolutionofpolycation. ThisapproachwasusedbyShamaei etal. asanantifouling

coatingformembranes,improvingthetreatmentofoily wastewater.139 Gu etal. usedlignosulfonatesandpolyethyleneimineonapolysulfonemembrane,whichsuccessfully repelledtheadsorptionofproteins.15 Whilethepreparationis straight-forward,thelong-termstabilityofsuchcoatingsalso mustbedemonstrated.Boththeligninand(poly-)cationwere water-soluble,sothecoatingwouldbepointlessifwashedaway withtheretentate.

3.3.4.Packagingapplications. Packagingapplicationscan benetfromlignin-containingsurfacesinvariousregards. Improvementsinthewater-resistance,waterandoxygen barrier,andmechanicalstrengthofcellulose-basedsubstrates havebeenreported.35,107,108,140 Amoredetailedsummaryofthese materialsisgiveninSection3.3.1.Theligninmayalsoserveas anoxygenscavenger.Toimplementthis,severalauthorshave formulatedcoatingsthatincludebothligninandlaccase enzyme.113–115 Atlast,theantibacterialandUV-shieldingpropertiesofligninhavebeenmentionedasbenecialcontributors.83,107,110 Whilethestudiesdemonstratefeasibilityon atechnologicallevel,thereareotherfactorsthatmustbe consideredaswell.Long-termstabilityandmigrationofthe coatingsisrarelyaddressed,despitethisbeingacrucial parameterinfoodpackaging.Inotherwords,onemustbesure thatnodetrimentalsubstancesaretransferredtothefood. Somefoodsreleasebothwaterandfat,forwhichligninisin theoryagoodmatch,asitissolubleinneither.Packagingof non-foodsgenerallyposeslessharshrequirements.The requirementsonpricepervolumearegreater;however,the pricingoftechnicalligninshouldbecompetitive.

3.3.5.UV-protection. Thepolyaromaticbackboneoflignin providesextendedabsorptionatsub-visiblewavelengthsof light.UV-shieldingapplicationshencedrawononeofthe intrinsicpropertiesoflignin.Oneexamplewouldbethe developmentofnaturalsunscreens via hydroxylationoftitaniumoxideparticles,duringwhichlignosulfonateswere added.141 Unsurprisingly,itwasconcludedthatthelignin enhancedtheUV-blockingeffectofthetitaniumoxideparticles. Anotherpublicationexploredsunscreens,wherenanoparticlesizeligninwasaddedtocommerciallotionformulations.142

Fig.12

TheUVabsorbancewasimprovedbybothnanoparticle formationandpretreatmentwiththeCatLigninprocess.The latterwasexplainedbypartialdemethylationandboostingof chromophoricmoieties.Whileligninmayconvenientlyreplace fossil-basedandnon-biodegradableUVactives,otherfactors alsoneedtobetestedforsuchaproducttobecomefeasible, e.g.,non-hazardousness,safetyforhumancontact,andskin tolerance.

Otherapplicationsthatcanprotfromthispropertyinclude UV-protectiveclothing,91 packagingmaterials,83,107 agrochemicalformulations,122 andpersonalprotectiveequipment.134 It shouldbementioned,however,thatenhancedUVabsorbance isnotalwaysbenecial,asitcanalsoleadtofasterdegradation ofthelignin-containingmaterials.12

3.4.Ligninaspartofthermoplasticmaterials

Ligninisathermoplasticmaterialwithglass-transition temperaturesintherangeof110–190°C.24 Assuch,itis straightforwardtousetechnicalligninasa llermaterialin, e.g.,thermoplasticsorbitumenadmixtures.38 Potentialadvantagesoflignininthermoplasticpolymercoatingshavebeen discussedbyParitandJiang,21 i.e.,byaddingUV-blockingand antioxidantactivityasrequiredinpackagingapplications.In general,theadditionoflignininthermoplasticscanincrease stiffness,butattheexpenseofextensibility.38 Chemicalmodication(alkylation)mayberequiredtoimprovebothtensile stiffnessandstrengthofolenicpolymers.26 Ontheotherhand, lignin'samphiphilicmake-upcanimpartadvantages, e.g.,by improvingtheadhesionofpolypropylenecoatings.143 Another examplewouldbetheuseoflignininbiocompositesfrom polypropyleneandcoir bers.45 Whilenosignicanteffecton tensilestrengthofthecompositeswasfound,addinglignin reportedlydelayedthethermaldecomposition.

Coatingswithpolymersarefrequentlyusedtoprotectthe mechanicalintegrityoftheunderlyingsubstrate.Foradded lignintobeadvantageous,themechanicalcharacteristicsofthe polymerblendmusthencebeimproved.Whilepublicationsin thisareafrequentlyfocusontheaddedfunctionalities,some alsoreportedimprovementsinthemechanicalstrengthofthe coatings.12,26 Onthedownside,theadditionofligninisoen limitedtolowratiosandchemicalmodicationmaybe required.12 Thesefactorscanlimittheoverallsustainability

gain,whichbiopolymershaveoverfossil-basedpolymersand llers.

Atlast,slow-releasefertilizerscanbepreparedfromthermoplasticsandlignin.Li etal. blendedpoly(lacticacid)(PLA) withKra ligninsamples,someofwhichhadbeenchemically modiedbyestericationorMannichreaction.144 Ureaparticles werethencoatedbysolventcastingordip-coating,wherethe alkylatedligninyieldedimprovedbarrierpropertiesandbetter compatibilitywithPLA.Microscopeimagesofthecoatedurea particlesareshowninFig.13.Whilelignin-PLAblendscan potentiallybemorebiodegradablethanlignin-basedresins,the biodegradationinsoilmaystillbeinsufficient.Ourrecommendationishencetofavorblendsofunmodi edligninwith biopolymers,suchasstarch,cellulose,orcarrageenan,asthis willnotcontributetomicroplasticspollution.

3.5.Ligninasaprecursortothermosets

Thefourmostcommonapplicationsoflignininthermosetsare polyurethane,epoxideresins,phenolicresins,andpolyesters.11 Unsurprisingly,formulationsoflignin-basedthermosetcoatingsareoenderivedfromsuchchemistries.Thelignincan alsoberenderedcompatiblewithotherformulations, e.g.,with polyacrylatesbygraingwithmethacrylicacid.145 Suchgraing reactionsareindeedinstrumentaltoovercomesomeofthe traditionalchallengesoflignin;146 however,theycanalsobe accompaniedbyunwantedside-effects,suchaspoor biodegradability.

3.5.1.Lignin-basedpolyurethanecoatings. Ligninutilizationinpolyurethanesisdoneaspolyolreplacement,where lignin'shydroxylgroupsarereactedwithisocyanategroups actingascross-linker.Theligninmayevenbesolubleinthe polyol,whichaidsstraight-forwardsubstitution.Ligninderivatizationtoimprovethecompatibilityandperformance includeshydroxyalkylation(e.g.,withpropyleneoxide, propylenecarbonate,orepichlorohydrin),estericationwith unsaturatedfattyacids,methylolation,anddemethylation.28

Chen etal. blendedalkaliligninandPEG,whichwerefurther polymerizedwithhexamethylenediisocyanateinpresenceof silicaaslevelingagent.147 Experimentswerelimitedto60wt% lignin,ashigherratiosyieldedanembrittlement.Themixtures wereprocessedinto lms,whichshowedsomepotentialfor biodegradation.Theseresultsindeedcorroboratedbyother authors,whichalsostatethatligninincorporationin

polyurethanesyieldedalimiteddegreeofbiodegradability.148 A differentapproachwasmadebyRahman etal., 149 whosynthesizedwaterbornepolyurethaneadhesiveswithaminatedlignin. ThetensilestrengthandYoung'smodulusimprovedwith increasingratiosofaminatedlignin,whichcouldbeduetoan increasedcross-linkingdensity.Still,theoverallpercentagesof lignininthecoatingswerecomparablylow,astheauthors addedonlybetween0–6.5mol%lignin.Itiscurioustonotethat theauthorsproclaimedbetterstoragestabilityofaminated lignindispersions,yetonlytheweatheringresistanceofthe nalcoatingwasmeasured.

Someofthechallengeswithlignininpolyurethanematerials includereactivityandahighcross-linkingdensity.Duetothe latter,polyurethaneformulationsarefrequentlylimitedtolow percentagesoflignin,typically20–30wt%atmax,ashigher ratioscanyieldbrittleandlow-strengthmaterials.150 One approachistoincreasethedegreeofsubstitutionisdepolymerizationoflignin,butotherchemicalmodicationsorfractionationsmaybeequallyapplicable.Inthiscontext,thework byKlein etal. shouldbementioned,whoreportedpolyurethane coatingswithligninratiosofupto80%.151 Acomparablylow curingtemperatureof35°Cwasused,whichcouldalsoentail incompletereaction.Curiously,thereisnodataonthe mechanicalstrengthofthe lms.Inaddition,theauthors measurementsofhydroxylgroups via ISO14900and 31p-NMR arewidelydivergent.Intwootherpublicationsbythesame author,theantioxidantpropertiesandantimicrobialeffectof such lmswerestudied.13,152 Inadifferentstudy,methyltetrahydrofuranwasusedtoextractthelow-molecularweight portionfromKra lignin.153 Theauthorsusedbetween70to 90wt%lignininthe nalformulationatNCO/OHmolarratios of0.16–0.04.Whileprovidingagoodadhesivestrength,the lmselasticmodulusiswithinthesamerangeofthefractionatedlignin,whereasnoinformationonthematerialstrength wasprovided.Itwouldthusappearthattheelevatedcrosslinkingdensitymaybecircumvented, i.e.,simplybyreacting onlyasub-fractionoftheavailablehydroxylgroupsoflignin. Still,ithasyettobedemonstratedthatsuchcoatingsarealso competitiveinmechanicalstrengthandabrasionresistance.

3.5.2.Lignin-basedphenolicresincoatings. Ligninmay alsobeusedasaphenol-substituentinphenol-formaldehyde resins.20 ThisapproachwasutilizedbyPark etal. toproduce cardboardcompositesbyspraycoating.154 Theauthorsreported thatligninpuricationbysolventextractionyieldedbetter resultsthanbyacidprecipitation.Substitutingwith20–40wt% ligninsurprisinglyacceleratedthecuringkinetics,comparedto thelignin-freecase.Thecoatedcardboardshowedlowerwater absorption;however,thecontactanglewasalsolower,which couldbeduetoachangeinsurfacechemistryandmorphology. Itwouldbeinterestingtostudyevenhigherdegreesofsubstitutionandtodelineatewiththemechanicalstrength.Still,it appearsthatcoatingswithlignin-phenol-formaldehydehaveso farbeenaimedatprovidingawater-barrier.Forexample,the workbyRotondo etal. coatedsuperphosphatefertilizerswith hydroxymethylatedligninresins,119 whichsignicantlyslowed thephosphaterelease.

3.5.3.Lignin-basedepoxyresincoatings. Similartolignincontainingpolyurethanes,epoxyresinsalsotargetareaction withthehydroxylgroups.Inanalogytothat,chemicalconditioningsuchasdepolymerizationcanpotentiallyimprovethe nalmaterial.Forexample,Ferdosian etal. testeddifferent ratiosofdepolymerizedKra ororganosolvlignininconventionalepoxyresinformulations.155 Theauthorsshowedthat largeamountsofligninretardedthecuringprocessparticularly inthelatestageofcuring.Attherightdosage(25%),theligninbasedepoxyexhibitedbettermechanicalpropertiesthanthe neatformulation,whileimprovingadhesiononstainlesssteel. Botheffectsappearplausibleconsideringligninsmacromolecularandpolydispersecomposition.Inthiscontext,arecent patentbyAkzoNobelshouldalsobementioned,which describestheuseofligninandpotentialepoxycrosslinkerfor functionalcoatings.156 AdifferentapproachwaschosenbyHao etal.,whocarboxylatedKra lignin rst,followedbyitsreaction withPEG-epoxy.157 Thecoatingspossessedalignincontentof 47%.Inaddition,theself-healingabilitywasdemonstratedby transestericationreactioninpresenceofzincacetylacetonate catalyst.

Crosslinkingofnanoparticlesisaninterestingapproach,as thecoagulationtonanoparticlesmayfavoradifferentratioof functionalgroupsatthesurfacethaninthebulklignin.In addition,thisapproachcanproducecompositematerials, whichexhibitdifferentcharacteristicsthanahomogeneous polymer.Forinstance,Henn etal. combinedligninnanoparticleswithanepoxyresin, i.e.,glyceroldiglycidyl ether,totreatwoodsurfaces.106 Thecoatingsshowednanostructuredmorphology,whichstillpreservedthebreathability ofthewood,hencedrawingadvantagefromlignin'snanoparticleformation.Zou etal. coprecipitatedsowoodKra lignintogetherwithbisphenol-a-diglycidylethertoproduce hybridnanoparticles.158 Theparticleswereeithercuredin dispersionforfurthercationizationordirectlytestedintheir functionaswoodadhesives.Theuseoflignin-basednanoparticlesincurableepoxyresinsishencepromising,asitcan generatenewfunctionalities,butthematurityofthistechnologystillneedstobeadvanced.

3.5.4.Lignin-basedpolyestercoatings. Whiletheuseof lignininpolyestercoatingsistechnologicallyfeasible,few publicationswerefoundtothistopic.Onereasonforthiscould betheslowreactionkineticsofdirectesterication.Coupled withlignin'sstructureandchemistry,polyester-basedcoatings wouldbelessstraightforwardthanpolyurethanesorepoxy resins,whichinvolvehighlyreactivecouplingagents.Asdiscussedpreviously,chemicalmodicationofligninmayimprove thiscircumstance,forexamplebydepolymerizationorintroductionofnewreactivesites.Assuch,oxidativedepolymerizationandsubsequentmembranefractionationhasbeen suggestedtoproducearawmaterial,whichcanbeutilizedin subsequentpolyestercoatings.159 Asecondexamplewouldbe solvent-fractionatedlignin,whichhasbeencarboxylatedby estericationwithsuccinicanhydride.19 AsillustratedinFig.14, themodiedligninreportedlyunderwentself-polymerization, wherethegraedcarboxylgroupsreactedwithresidual

hydroxylgroupsonthelignin.Developmentinthisareahas potential,aspolyesterstendtoexhibitbetterbiodegradability thanpolyolens.

3.5.5.Lignin-basedacrylatecoatings. Lignin-basedacrylatesrelyonthegraingofacrylatemoieties,asthesearenot inherenttolignin.Forexample,methacrylationofKra lignin wasdonetoproduceUV-curablecoatings.145 Theauthors concludedthatincorporatingligninintotheformulation improvedthermalstability,curepercentage,andadhesive performance.Anelaboratestudyonagingoflignin-containing polymermaterialswasconductedbyGoliszek etal.30 The authorsgraedKra ligninwithmethacrylicanhydrideand furtherpolymerizedtheproductwithstyreneormethylmethacrylate.Lowamountsoflignin(1–5%)showedincorporation intothenetwork,whereashigherconcentrationsshowed aplasticizingandmoreheterogeneouseffect.Highlignin loadingsalsoenhancedthedetrimentaleffectsofaging,which mayseemcounterintuitive,asotherreportsfrequentlystate aUV-protectiveabilityoflignin.Still,increaseabsorptionofUV lightcanalsoamplifythedetrimentaleffectsthereof.A combinationofepoxyandacrylatewasusedtodevelopdualcuredcoatingswithorganosolvlignin.160 Theligninwas rst reactedwithepoxyresinandsubsequentlywithacrylatetoform aprepolymer.Inasecondstep,theprepolymerwasmixedwith initiatorsanddiluenttobecoatedontotinplatesubstrates.All inall,lignin-basedacrylatecoatingsappeartohavereached sufficienttechnologicalmaturity,yettheadvantageofadding ligninissometimesunclear.

3.5.6.Otherapproaches. Szabo etal. graedKra lignin with p-toluenesulfonylchloride,whoseproductwasthengraftedontocarbon bers.161 Theresultssuggestedanimproved sheartoleranceofthemodiedcarbon bersinepoxyor cellulose-basedcomposites.SilylationwasfurthermoreperformedofKra lignin,whichwasfurtherco-polymerizedwith

permissionfromAmericanChemicalSociety,copyright2018. ©2023TheAuthor(s).PublishedbytheRoyalSocietyofChemistry

polyacrylonitrile.162 Theauthorsconcludedthatsilylation improvedthecompatibilityforsurfacecoatingsand lms.

4.Ligninintechnicalapplications –acriticalcommentary

Thedevelopmenthigh-valueproductsfromligninhasbeen atopicofgreatinterestforsomeyears,andisstillgaining popularity.163 Added-valueapplicationsarebeingpursued, rangingfromasphaltemulsiersorrubberreinforcingagents, totheproductionofaromaticcompounds via thermochemical conversion.164 Thequestionarises,however,ifincludinglignin inacoatingcanreallyleadtoabetteroverallproduct? Comparisonwithstate-of-the-artformulationsisfrequently omitted,benchmarkinglignin-basedsolutionsonlytoareferencecasewithlowperformance. “Attributingvaluetowaste” is oneoftheprimarymotivationsbehindlignin-orientedresearch. Forexample,bioethanolproductionfromlignocellulose biomassoengivesrisetoalignin-richbyproduct.Theoverall economicsofsuchbioreneriescouldbeimprovediftheligninrichresiduecouldbemarketedatavalue.Still,toestablish anewproductonthemarket,thisproductalsoneedsto competewithexistingsolutionsintermsofperformanceand price.Thispointisoenoverlookedinliterature,inparticular concerninglignin-basedsurfacesandcoatings.

Harnessinglignin'sinherentpropertiesiskey,asthiscan createsynergiesandyieldanadvantageoverotherbiopolymers. Itcomestonosurprisethatthedominantuseoftechnical ligninisinwater-solublesurfactants,aspolydispersityisakey featurehere.3 Ashasbeenpointedout,theperformanceof surfactant-blendsoenoutperformssinglesurfactantsinrealworldapplications,sincethemixturecanpreserveitsfunction overawiderrangeofenvironmentalconditions.Asecond exampleofkeypropertieswouldbelignin'spolyphenolic

Fig.14 Schematicofproducinglignin-basedthermosettingpolyestercoatings.This figurehasbeenadapted/reproducedfromref.19with

structure,whichisnotfoundincommonpolysaccharides. LigninhashencebeeninvestigatedasaUVblockingadditivein e.g.,sunscreenproductsorpackaging.165 However,compatibilityoftheresultingproductwithhuman-orfood-contactis addressedinsufficientlybymanyauthors.Asimilarsituation wasgivenincaseofligninasantioxidantadditivein cosmetics,166 wherethedarkcolorandsmellmaylimitthe nal use.

Comparedtocelluloseorhemicellulose,ligninhasahigher carbon-to-oxygenratio.Duetothisanditspolyaromaticstructure,itwouldindeedbeabetterrawmaterialforproducing carbonaceousmaterials.Researchonactivatedcarbon, graphiticcarbon,andcarbon bershasindeedbeingconducted.167 Akeysteptowardlignin-basedcarbon berproduction wasidentiedasremovalof b-O-aryletherbonds.60 Inaddition, thecharringabilityofligninhasbeenproposedasabenetin reretardants.168 Still,lignin-based reretardantsoenuse chemicalmodications,suchasphosphorylation.Ifchemical modicationisnecessary,thequestionarisesifsuchchemistriesreallyneedtobebasedonlignin,sinceotherbiomacromoleculesmaypossessahigherreactivityandnumberof reactivesites.

Lignincanbereadilyprecipitatedfromsolutionintonanoparticlesandnanospheres.Variousapplicationshavebeen suggestedbasedonthis,suchasfunctionalcolloidsand compositematerialswithusesin ameretardancy,foodpackaging,agriculture,energystorage,andthebiomedical eld.169 A morespecicexamplewouldbenanoparticulatedligninin poly(vinylalcohol) lmswithincreasedUVabsorption.170 While thistechnologyappearsstraight-forward,its nalusehasyetto beproven.

Atlast,technicalligninisusuallythermoplastic,exhibiting glass-transitiontemperaturesintherangeof110–190°C.24 The useofligninaspolymeric llerorinthermoplasticblendsis hencepromising.Insomecases,chemicalmodicationmaybe necessarytoimprovecompatibility, e.g.,withpolyolens;26 however,theuseassimple llermaterialwouldnotnecessitate modication.Additionalstrengthcouldalsobederivedfrom addedcellulose bers,whichcouldpotentiallybenetfrom addedligninascompatibilizer.

Insummary,oneneedstobuildontheinherentpropertiesof lignin,suchaspolydispersity,poly-aromaticity,ahigherC/O ratiothanforpolysaccharides,andthermoplasticity.Onlyby utilizingcharacteristicsthatsetligninapartfromother biopolymers,cansolutionsbedevelopedthatareinnovative andmarketcompetitive.Chemicalmodicationisausefultool fortailoring;however,eachprocessingstepwilladdan economicalandenvironmentalcosttothe nalproduct.In otherwords,thesimplestapproachisoenthebest – somethingthatisfrequentlydisregardedwhendevelopingcomplex synthesisprotocolsforlignin.

5.Summaryandconclusion

Functionalsurfacesandcoatingscanbeformulatedinavariety ofways,whichincludestheuseofneat,chemicallymodied, blended,andcross-linkedlignin.Thisreviewprovides

asummaryofthecurrentdevelopmentsinresearch,where focuswasplacedontheformulationand nalapplications. Overall,coatingswithneatligninorblendsofligninwith otheractiveingredientsappearthemostpractical.Reduced wettingisherebyachieved,asthelignincanalterthesurface morphology,hindermass-transport,andconneswellingof enclosed bers.Theligninitselfisnotconsideredahydrophobicmaterial,becausethecontactangleisusuallybelow90°. Ontheotherhand,hydrophobicitycanbeinducedbyplasma surfacetreatment,blendingwithotheragents,orchemical modication.Forthelatter,graingorestericationoflignin withalkyl-containingmoietiesisafrequentlytakenapproach. Chemicalmodicationmayalsobeusedtoimprovethe compatibilitywitholenicthermoplastics.Additionoflignin can ne-tunethecharacteristicsthermoplasticsandimprove adhesiontoothermaterials.Onthedownside,embrittlement frequentlylimitsthistechnologytolowpercentagesoflignin. Thermosetcoatingswithlignincanbebasedonchemistries suchaspolyurethanes,phenolicresins,epoxyresins,polyesters, andpolyacrylates.Varioussynthesisrouteshavebeenproposed inliterature,whichcanbenettosomedegreeoftheinherent propertiesoflignin.

Boththeformulationandprocessingdependonthe nal applicationofthecoatingorsurfacefunctionalization.Theuse ofligninwithcellulose-basedsubstratesisfrequentlysuggested,asthiscanyieldall-biobasedmaterials.Lignincan improvetheresistancetowettingofpaperandpulpproducts.In addition,itcanaddUVprotectionandoxygen-scavenging capabilitiesinpackagingapplications.Lignin-basedsurfaces havealsobeenproposedforadsorbentsforwastewatertreatment,woodveneers,andcorrosioninhibitorsforsteel.The biomedical eldhasalsoexploredlignin-basedbiomaterials, whichdrawonitspotentialantimicrobialproperties.Agreat numberofpublicationsalsoreportsonagriculturaluses,where alignin-basedcoatingmayaccountforslowerreleaseoffertilizer.Atlast,general-purposepolymercoatingscanbetailored via theinclusionoflignin,andtheresistancetofoulingof membranescanbeimproved.Allmentionedapplicationswere discussedcriticallyinthisreview,placingemphasisonthe benetthataddingligninmayprovide.Whileintroductionof functionalitiesmaybepossible,publicationsfrequentlydonot comparetoawell-performingreferencecase,hencelimitingthe assessmentofthetruepotential.Inaddition,theratiooflignin inthermosetcoatingsisusuallyquitelow.Higherlevelsmaybe achievedaerchemicalmodication,butsuchsynthesiscan alsohavenegativeimplicationsontheeconomicandenvironmentalcostofthe nalproduct.

Inconclusion,theadvancementoffunctionalsurfacesand coatingswithligninhasyieldedpromisingresults.However, therealsomustbeabenetofusinglignincomparedtoother biopolymersorexistingpetrochemicalsolutions.Onlybyharnessinglignin'sinherentproperties,cansolutionsbedeveloped thatarecompetitiveandvalue-creating.Theseproperties includelignin'spolyphenolicstructure,ahigherC/Oratiothan, e.g.,polysaccharidebiopolymers,itsabilitytoself-associateinto nano-aggregates,anditsthermoplasticity.Thesepropertiesare

utilizedinsomeofthereviewedliterature,henceprovidingthe groundfornewandpromisingtechnologyinthefuture.

Authorcontributions

JostRuwoldt:conceptualization,writingoriginaldra,review, editing&visualization.FredrikHeenBlindheim:writing& visualization.GaryChinga-Carrasco:writing,review,editing, visualization,supervision.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconictofinterest.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorsthanktheResearchCouncilofNorwayforfunding partofthiswork.

References

1W.Boerjan,J.RalphandM.Baucher,LigninBiosynthesis, Annu.Rev.PlantBiol.,2003, 54,519–546,DOI: 10.1146/ annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938

2H.H.Nimz,D.Robert,O.FaixandM.Nemr,Carbon-13 NMRSpectraofLignins,8.StructuralDifferencesbetween LigninsofHardwoods,Sowoods,Grassesand CompressionWood, WoodResTechnol,1981, 35(1),16–26, DOI: 10.1515/hfsg.1981.35.1.16

3J.Ruwoldt.EmulsionStabilizationwithLignosulfonates, Lignin – ChemStructAppl.,2022,DOI: 10.5772/ intechopen.107336.

4J.Ruwoldt,ACriticalReviewofthePhysicochemical PropertiesofLignosulfonates:ChemicalStructureand BehaviorinAqueousSolution,atSurfacesandInterfaces, Surfaces,2020, 3(4),622–648,DOI: 10.3390/ surfaces3040042

5I.F.Demuner,J.L.Colodette,A.J.Demunerand C.M.Jardim,Bioreneryreview:Wide-reachingproducts throughkra lignin, BioResources,2019, 14(3),7543–7581, DOI: 10.15376/biores.14.3.demuner

6S.LaurichesseandL.Av´erous,Chemicalmodicationof lignins:Towardsbiobasedpolymers, Prog.Polym.Sci., 2014, 39(7),1266–1290,DOI: 10.1016/ j.progpolymsci.2013.11.004

7S.Shao,Z.Jin,G.WenandK.Iiyama,Thermo characteristicsofsteam-explodedbamboo(Phyllostachys pubescens)lignin, WoodSci.Technol.,2009, 43(7–8),643–652,DOI: 10.1007/s00226-009-0252-7 .

8Y.Zhao,S.Xiao,J.Yue,D.ZhengandL.Cai,Effectof enzymatichydrolysisligninonthemechanicalstrength andhydrophobicpropertiesofmolded bermaterials, Holzforschung,2020, 74(5),469–475,DOI: 10.1515/hf-20180295.

9T.J.Szalaty, Ł.KlapiszewskiandT.Jesionowski,Recent developmentsinmodicationofligninusingionicliquids

forthefabricationofadvancedmaterials–Areview, J.Mol. Liq.,2020,301,DOI: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112417 .

10J.Gil-Ch´avez,S.S.P.Padhi,U.Hartge,S.Heinrichand I.Smirnova,Optimizationofthespray-dryingprocessfor developingaquasolvligninparticlesusingresponse surfacemethodology, Adv.PowderTechnol.,2020, 31(6), 2348–2356,DOI: 10.1016/j.apt.2020.03.027 .