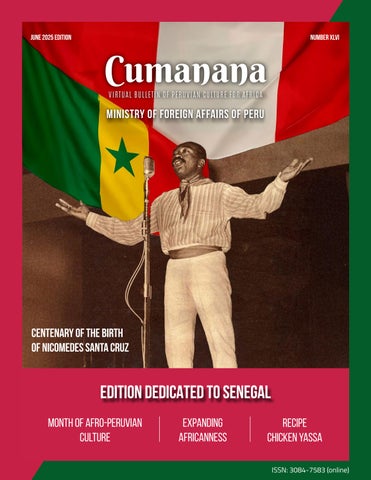

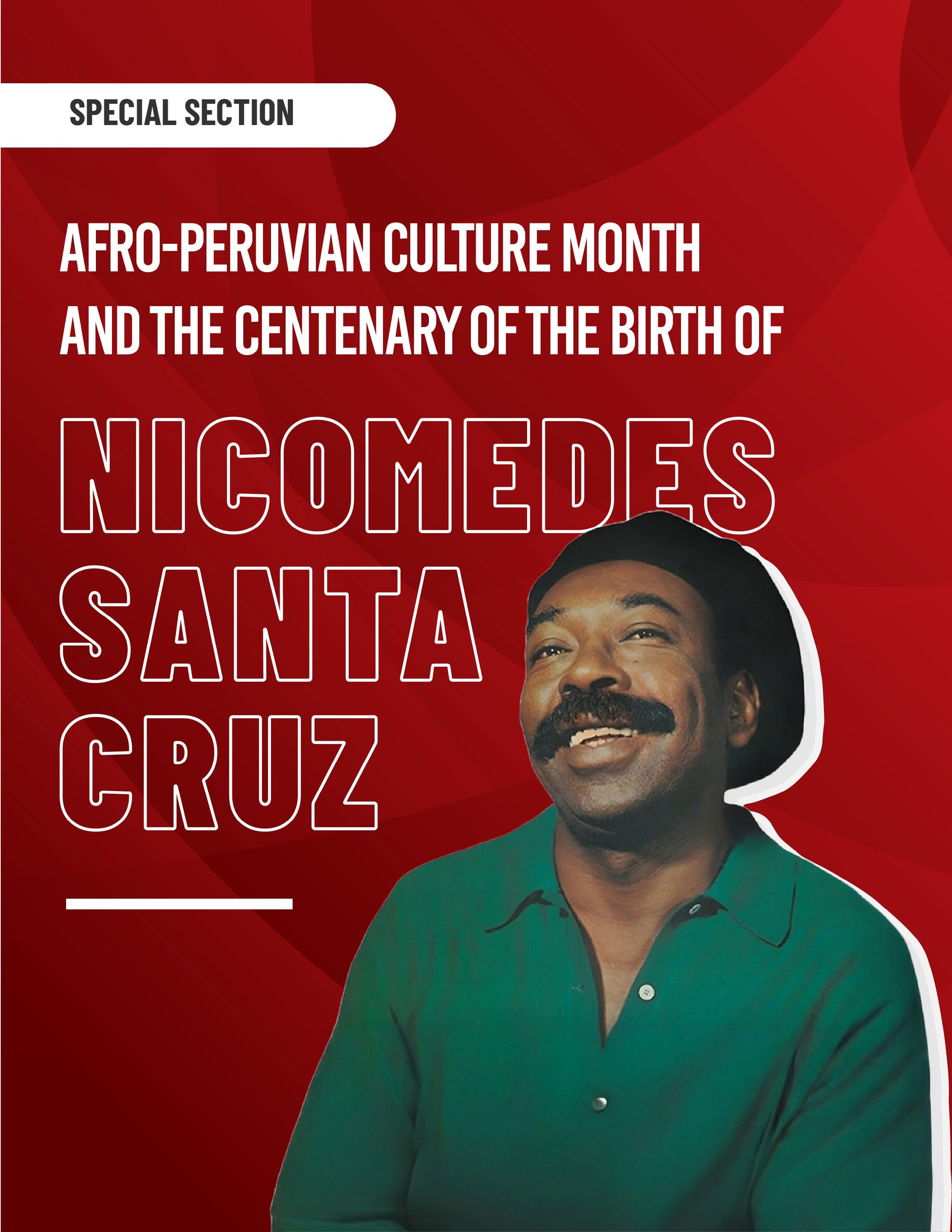

CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF NICOMEDES SANTA CRUZ

EDITION DEDICATED TO SENEGAL

MONTH OF AFRO-PERUVIAN CULTURE

EXPANDING AFRICANNESS

RECIPE CHICKEN YASSA

CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF NICOMEDES SANTA CRUZ

MONTH OF AFRO-PERUVIAN CULTURE

RECIPE CHICKEN YASSA

Coffee is more than just a traditional beverage: it represents a social act, a symbol of identity, and a story in every cup. As such, coffee takes on particular characteristics in each country, reflecting the culture and ingenuity of its communities. This is the case in both Senegal and Peru, where coffee has become a central element of cultural expression. In Senegal, Touba Coffee is a legacy of spirituality and inventiveness, a manifestation of the Mouride heritage; whereas in Peru, coffee is synonymous with agricultural tradition, national pride, and potential for economic development. It is therefore of great interest to delve into the history of Senegal’s most popular coffee and contrast it with the Peruvian experience in the coffee sector, with a view to promoting the global dissemination and commercialisation of this distinctive beverage.

To understand the unique origins of Touba Coffee, it is essential to delve into the history of a mystical Islamic brotherhood derived from the Sufi order. Sufism is an ascetic dimension of Islam in which devotees seek unity with God through devotion, meditation, and purification of the soul. In fact, Senegal has the highest number of Sufi Islam followers among all Muslim-majority countries (Mbacke, 2016). One of the main branches of Sufism in Senegal is Muridism, which comprises nearly 28% of the country’s population (Le Journal International, 2015). This brotherhood merges the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad with Wolof culture, which has preserved traditions from pre-colonial Senegalese kingdoms long before European colonization.

Source: flickr.com/jbdodan

In the 19th century, the Mouride leader Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba founded the city of Touba, which would later become the capital of Muridism (Filicori, 2022). According to Senegalese accounts, between 1883 and 1902, when coffee was already widely consumed in the country, a severe shortage led to symptoms of dependency among the population. True to their philosophy of hard work and discipline as forms of devotion to God, the Mourides refused to succumb to the crisis. Ahmadou Bamba devised an alternative by creating a beverage that, while still containing imported coffee, used it in smaller quantities and was enriched with readily available spices. This gave it a distinctive spiced flavor and a spiritual connotation, leading to the creation of Touba Coffee. Today, the coffee beans, either Arabica or Robusta, are imported from Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and Togo. The key spices, such as cloves (guedj) and Selim pepper (djar), come from Guinea. The preparation process is unique because the coffee beans are roasted along with the spices, then ground and filtered through hot water. This results in a one-of-a-kind beverage that stands as a testament to Senegalese ingenuity.

The consumption of Touba Coffee is often associated with enhancing focus and devotion, providing mental clarity for meditation and prayer. For much of the 20th century, it played a central role in the religious ceremonies of the Mouride brotherhood. Additionally, its preparation and consumption are deeply tied to the philosophy of community service as an expression of hospitality Recent scientific studies suggest that Touba Coffee also has medicinal properties. Its ingredients aid digestion and stimulate the production of endorphins, which is why it is also considered a natural antidepressant.

Although it was originally a religious and communitybased beverage, the expansion of Touba Coffee throughout Senegal has turned it into a highly successful commercial product, widely available in street stalls and supermarkets. However, outside its borders, it remains a niche product, especially in France, where the Senegalese diaspora has begun to popularize it. This presents an opportunity to expand its international market reach, particularly by implementing strategies like those used by other coffee-producing nations that have successfully positioned their products in global markets.

In Peru, coffee is one of the country’s main traditional agricultural export products, serving as an economic pillar that generates employment throughout its value chain for more than two million Peruvians

(Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego del Perú, 2022). Its coffee-producing regions, such as Cajamarca, Junín, and San Martín, have developed an industry that exports to international markets. Peru is the world’s ninth-largest producer of Arabica coffee (Promperú, 2023) and is a member of the International Coffee Organization (ICO), which allows it to participate in the regulation, trade promotion, and sustainability of the global coffee sector. For these reasons, despite Senegal not being a natural coffee producer and offering a semi-manufactured product, Peru’s model provides valuable lessons in terms of commercialization and positioning in global markets. Applying these insights could enable Touba Coffee to transcend its local consumption and achieve a stronger presence in the international market.

In 2024, Peru’s roasted coffee bean exports reached USD 850 million, maintaining its position as a key player in the global market thanks to its diversification strategy, which has allowed it to establish itself in high-value niches. One example of this diversification is its leadership in the production and export of organic coffee, a category in which it shared the top position worldwide with Ethiopia in 2022 (Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego del Perú, 2022). Additionally, the strengthening of Peruvian coffee quality has positioned it in the gourmet segment, with strategic alliances with international roasters and coffee shops. This experience makes the Peruvian model a valuable reference for Senegal, as it demonstrates strategies that could position Touba Coffee in new markets and leverage its history and uniqueness to attract consumers beyond the Senegalese diaspora.

Given Peru's extensive knowledge and experience in coffee production, commercialization, and export, it would be interesting if, in the near future, it provided technical cooperation to Senegal through a specialized training program focused on coffee trade and promotion. This program could emphasize diversification strategies, quality certifications, and access to global markets. Additionally, to facilitate

implementation, the training sessions could be conducted in English. This initiative would benefit both parties: Senegal would gain key tools to expand its coffee globally, while Peru would strengthen its position as a provider of technical cooperation by increasing its influence in Africa and promoting awareness and consumption of Peruvian coffee in new markets.

In conclusion, both in Peru and Senegal, coffee transcends its status as a mere beverage to become a social phenomenon, a reflection of deep cultural identities, and a commercial opportunity with great potential. Despite their cultural differences, both countries share a sociological dimension in which coffee serves as a space for gathering and tradition. The cultural value of Peruvian and Senegalese coffee paves the way for a bilateral relationship where trade, cooperation, and mutual learning can strengthen the existing bonds of friendship. Senegal, with its rich cultural heritage and vibrant identity, reminds us that the history of coffee is also the history of the people who cultivate it, share it, and transform it into a living legacy. Let the aroma of coffee be a bridge between these two nations, a call to brotherhood, and a testament to the greatness of both cultures.

REFERENCES:

C. (2016). Touba Coffee: A traditional beverage of Senegal. In Cultural studies of African coffee (pp. 329-345). Routledge. https://books.google.es/s?hl= es&lr=&id=RHROn5OHgk4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA329&d q=Caf%C3%A9+Touba&ots=R4OMFLBsB8&sig=YLD fpMim9W2ClovXHrFpsNgKxe8#v=onepage&q=Caf% C3%A9%20Touba&f=false

Filicori, L. (2022). Un café con pimienta en Senegal: El Café Touba. https://filicorizecchini. com/es-es/blogs/magazine-fz-el-blog-dephilicori-zecchini/un-cafe-con-pimienta-ensenegal-el-cafe-touba?srsltid=AfmBOopXsrM6n99TmW7YQQUR1s-iXMSVfuRfObPWuFuTvE3mIGQk7n

Fritzon, V. (2016). Religion and business: The Mourides of Senegal. The Perspective https:// www.theperspective.se/2016/02/25/africa/ religion-and-business-the-mourides-of-senegal/

Gueye, A. (2001). De la religión en los intelectuales africanos en Francia. Cahiers d’études africaines, 162, 267-292. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.87

Junta del Café. (n.d.). El café de Perú. Recuperado de https://juntadelcafe.org.pe/el-cafe-de-peru/

Mbacke, I. (2016). The Mouride Sufi order. Berkley Center. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/ publications/the-mouride-sufi-order

Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego (MIDAGRI). (2023, noviembre 27). Perú es el primer productor y exportador mundial de café orgánico junto con Etiopía. Gobierno del Perú. https://www.gob.pe/ institucion/midagri/noticias/647409-peru-es-elprimer-productor-y-exportador-mundial-de-cafeorganico-junto-con-etiopia

Perfect Daily Grind. (2023). ¿Qué es Café Touba y cómo se prepara? https://perfectdailygrind.com/ es/2023/01/07/que-es-cafe-touba-como-seprepara/

Piermay, J.-L., & Sarr, C. (Eds.). (2008). La ciudad senegalesa. Una invención en las fronteras del mundo. https://www.persee.fr/doc/ outre_1631-0438_2008_num_95_358_4336_ t1_0351_0000_1

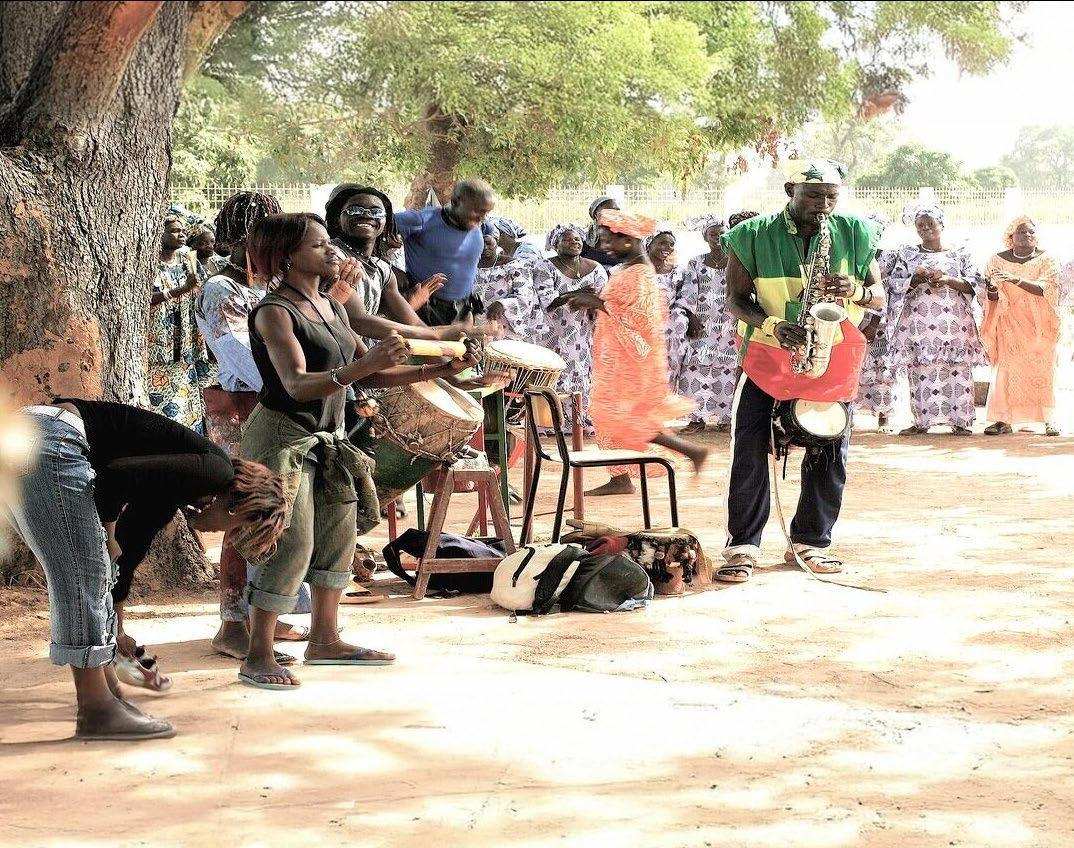

On the coasts of Senegal, a griot sings while playing the kora, a traditional African harp. Thousands of kilometers away, on the northern coast of Peru, a cumananero improvises verses that captivate his audience. Though separated by an ocean, these guardians of memory share a mission: to keep the history of their people alive.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Peru and Senegal, an occasion to rediscover the connection between two communities that have turned oral tradition into an invaluable record of their identity. In both nations, the spoken and finely crafted word has withstood the test of time and transcends mere communication: it is a bridge between generations, a living archive of stories, and a testament to cultural resilience.

In Senegal, griots are far more than mere storytellers, they are the living custodians of the past, recording every significant moment in the life of their communities. As Ngary Niang, a griot from the village of Ndiebene in the Saint-Louis region of Senegal, explains: “We are the masters of the art of speech: our pockets are filled with secrets, names, and deeds, ensuring that the stories of our people do not fade into oblivion” (Feal, 2020).

Historically, griots played crucial roles beyond storytelling—they served as ambassadors and heralds for rulers, mediated conflicts, led ceremonies, and advised sovereigns. Today, following the transformations brought by colonization, their role has evolved. As Niang describes: “(…) our role is to connect people, to tell them who they are and what binds them to their land and to one another, to weave anew the network that unites us” (Feal, 2020). Through their verses, these bards construct a communal chronology, bridging the past with the present.

Among the most memorable chronicles preserved by the griots, the Battle of Safilème on September 4, 1826, stands out; an episode that Niang recounts with particular pride: it was the day the people of Gandiol inflicted France’s first defeat on African soil (Feal, 2020). This story, like so many others, not only preserves historical events but also nurtures pride and provides insight into the destiny of the people.

Despite social and political changes, griots adapt their narratives to modern times while maintaining their role as guardians of history. As Oliver (1970) notes, “(…) [the griot] must also possess the ability to improvise on current events, incidental occurrences, and everything that surrounds him.”

Thanks to their keen insight and deep knowledge of local history, griots have played a crucial role in guiding their communities. Their storytelling art, known in Senegal as guewel, also conveys fundamental values such as solidarity and unity.

In Peru, cumananeros play a similar role through poetic improvisation. In the regions of Tumbes, Piura, and Lambayeque, another oral tradition has flourished over the years: the cumanana. This poetic art form, whose name traces its roots to the African Kikongo language, represents the confluence of the Spanish heritage of the décima espinela and AfroPeruvian creativity (Romero, 1988).

The Cumananeros, true popular minstrels, have transformed poetic improvisation into an art form with its own distinct nuances. Without relying on written records, these masters of words craft cumananas through verses that capture the essence of everyday life, love, social critique, and popular wisdom. As the renowned cumananero Belardo Alzamora (2018) puts it:

“Sir, i do not know how to read or write, with my memory i create, with my thoughtS i Speak, what thiS cheSt feelS here”.

Cumananas cover a wide range of themes and can sometimes take on a duel-like nature. They are neither written nor recorded; they are spontaneous, emerging in social gatherings as playful exchanges of wit. At times, they become mischievous duels in which two individuals improvise verses in response to one another.

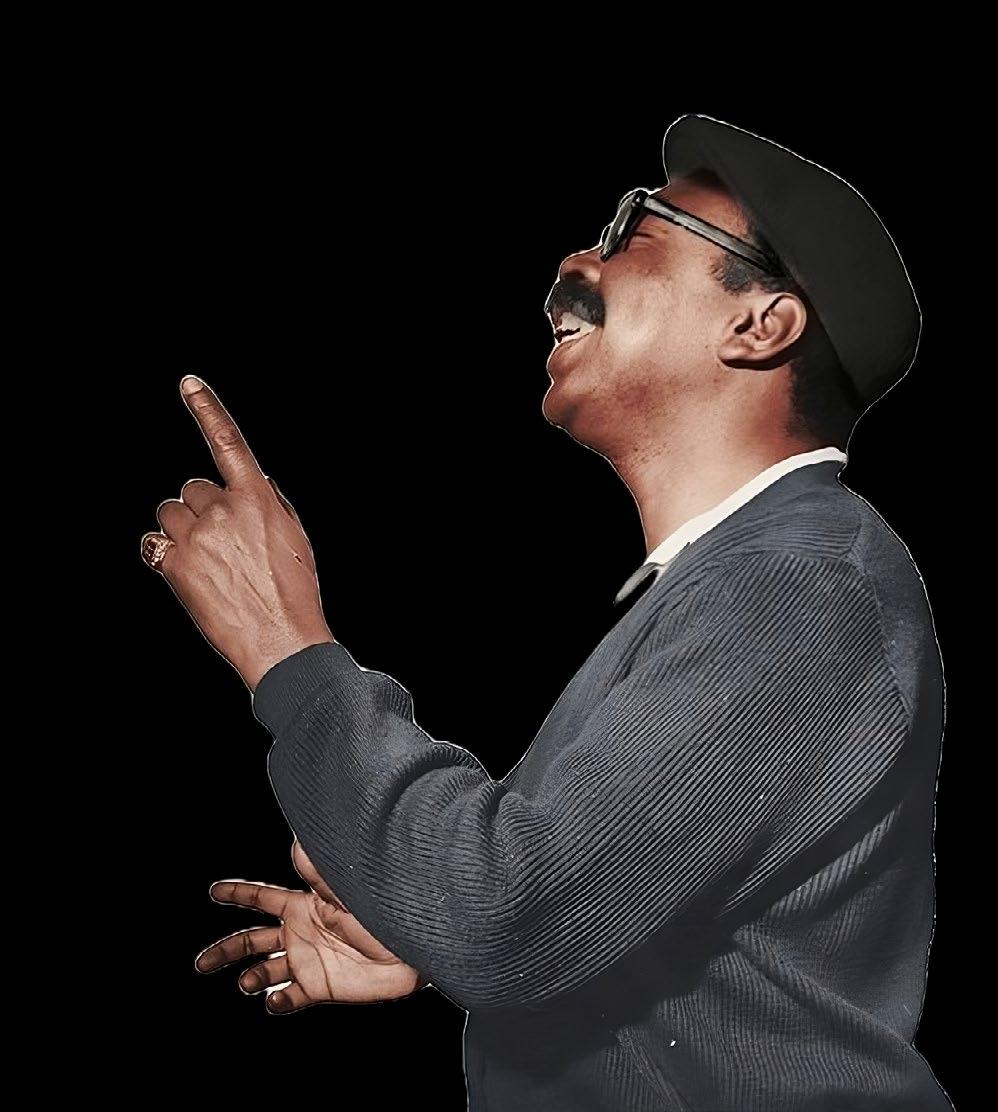

However, beyond mere entertainment, the cumanana is fundamentally a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Afro-Peruvian people. During times of slavery, they found in oral tradition a way to transform their pain into art. The esteemed Nicomedes Santa Cruz (1960) immortalized this tradition with verses that celebrate the skill of these artists:

“minStrelS of darkened Skin, amid Sugarcane fieldS So wide, recounted deedS with SteadfaSt pride of don Vicente eSpinel. no palm, no laurel to their name, nor marble hallS nor bronze acclaim. with Subtle wit and rum’S embrace, they found their Voice, their Sacred Space the black poetS of that time.”

Source: Andina.

Due to its significance, the cumanana was declared part of Peru’s national cultural heritage on November 26, 2004. Today, in addition to its transmission within families, governmental efforts are underway to document and teach this art to new generations, ensuring that this cultural expression is not lost over time.

Griots and cumananeros are the guardians of our memory. Oral tradition has been a refuge against oblivion. In Senegal, griots resisted the loss of identity following colonization. In Peru, cumananeros, descendants of enslaved Africans, used poetry to express their reality and preserve their legacy.

Recognizing these connections presents an opportunity to strengthen intercultural dialogue and revalue the richness of our shared traditions. By observing this similarity between our peoples, we understand that geographical distance fades in the face of our reflected heritage in intangible cultural expressions.

In a globalized world, where marginalized voices struggle to be heard, these traditions remind us that collective memory is not only written, but also sung, recited, and improvised.

Words are the invisible thread that weaves our histories together.

Source:centerforworldmusic.org/

PRODUCTIONS NUITS D'AFRIQUE PRÉSENTE SIAKA DIABATE

Source:lepointdevente.com

Alzamora, B. (2018). Voces Ancestrales: Poesía y Cánticos, Literatura oral afroperuana. Ministerio de Educación. https://hdl.handle. net/20.500.12799/7184

Anadolu Agency. (2023). Famous Senegalese Ablaye Cissoko plays the traditional kora instrument, in Saint-Louis, Senegal. Source: Daily Sabah.https:// www.dailysabah.com/arts/music/kora-dyinginstrument-fading-with-oral-history-of-westafrica

Andina. (2015). Nicomedes Santa Cruz recitando. Source: Andina. https://andina.pe/agencia/noticiacongreso-peruano-rendira-homenaje-a-culturaafroperuana-559034.aspx

Feal, L. (9 de enero de 2020). Los juglares africanos se llaman ‘griots’ y aún ejercen un oficio milenario. El País. https://elpais.com/elpais/2020/01/08/ planeta_futuro/1578477784_297707.html

Oliver, P. (1970). Savannah syncopators. Studio Vista.

Romero, F. (1988). Quimba, fa, malambo, ñeque: Afronegrismos en el Perú. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Santa Cruz, N. (1960). Décimas. Editorial Juan Mejía Baca.

luiS Miguel rodríguez chacón MiniSter in the diPloMatic Service of the rePublic of Peru

During the last decade, Peru’s foreign policy has evidenced a renewed interest in strengthening its ties with Africa, within the framework of a broader strategy of diversifying economic relations and consolidating international cooperation. In this context, Senegal has emerged as an important partner in West Africa, not only due to its political stability and regional leadership, but also because of its openness towards South-South cooperation and its commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals.

At the same time, the Senegalese government has shown interest in Latin American experiences, particularly Peruvian ones, in areas such as sustainable rural development, food security and the transition towards licit economies in vulnerable zones. Although the bilateral relationship is still in an initial phase, there are clear opportunities to articulate a strategic agenda that would allow the linking of lessons learnt by Peru in alternative development with Senegalese priorities in territorial inclusion and sustainable agriculture. These convergences represent a solid foundation for the formulation of a more robust, coherent and long-term bilateral agenda.

The establishment of diplomatic relations between Peru and Senegal responds to a Peruvian policy of geopolitical diversification and strengthening of ties with sub-Saharan Africa. This orientation is inscribed within the guidelines of South-South cooperation, which promotes the exchange of experiences between developing countries with similar challenges and contexts.

Despite not having a resident embassy in Dakar, Peru maintains concurrent diplomatic relations through its embassy in Rabat, Morocco. From Lima, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, through the General Directorate for Africa, the Middle East and Gulf Countries, has been promoting a cooperation agenda with Senegal centered on key sectors such as rural development, resilient agriculture and food security.

For its part, Senegal has shown sustained interest in Latin American models of inclusive social development, participating actively in multilateral forums organized by bodies such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), where it has had the opportunity to exchange experiences with Peru on matters of alternative development and the fight against illicit economies. This politicaltechnical dialogue has laid the foundations for greater bilateral articulation on issues of common interest.

Trade exchange between Peru and Senegal is still limited and asymmetrical. In 2023, Peruvian exports to Senegal reached an estimated value of USD 646,000. Whilst this amount is modest in absolute terms, it constitutes a starting point for building a more dynamic commercial relationship. Amongst the main exported products are dyes of vegetable or animal origin, certain processed foods and some manufactured goods of low added value.

In contrast, Peruvian imports from Senegal are practically non-existent, which reflects low integration between both economies. This situation is explained by structural factors such as geographical

distance, the lack of bilateral trade agreements, scarce logistical connectivity and the low reciprocal knowledge of the characteristics and opportunities of both markets.

One of the main challenges is the absence of direct logistical routes, which considerably increases transport costs. Added to this is the lack of institutional platforms that facilitate business rapprochement and investment. Overcoming these barriers requires a proactive strategy of economic diplomacy, accompanied by trade promotion mechanisms adapted to the African context.

One of the most significant contributions that Peru can offer to Senegal lies in its experience in comprehensive and sustainable alternative development (DAIS), implemented since the 1990s as a response to the expansion of illicit crops, particularly coca, in the San Martín Region and in the Monzón Valley, which are internationally recognized. This model, promoted by the Peruvian State with the support of international partners such as USAID, UNODC, Germany and the European Union, sought to structurally transform the rural economy through the progressive substitution of illicit crops with licit and sustainable alternatives such as cocoa, coffee and oil palm.

The Peruvian approach is characterized by a combination of technical assistance, institutional strengthening, market access and community participation. The National Commission for

Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA) leads this effort, which has made it possible to improve the livelihoods of thousands of rural families, whilst contributing to the consolidation of a licit and resilient economy.

Although Senegal does not face the same pattern of illicit economies as Peru, it does present challenges linked to subsistence agriculture, informality and illegal activities associated with smuggling and human trafficking in certain border regions. In this regard, the Peruvian model can offer valuable methodologies adaptable to the Senegalese context. Participatory planning, the development of rural value chains and the empowerment of local communities are replicable components that could enrich Senegalese territorial development programs in vulnerable areas.

The cultural sphere represents a strategic tool for strengthening ties between Peru and Senegal, especially at a stage where economic relations are still of low intensity. Cultural diplomacy, understood as the use of artistic expressions, historical heritage and shared traditions to foster mutual understanding, can play a key role in creating a common narrative between both nations.

Both Peru and Senegal possess rich and diverse cultural heritage, internationally recognized for its historical, symbolic and spiritual value. In the case of Peru, Andean-Amazonian diversity is manifested in a fusion of indigenous, Afro-descendant and mestizo traditions, expressed in its gastronomy, music, dances, popular art and community rituals. For its part, Senegal possesses a vibrant culture, in which African, Islamic and francophone influences are interwoven, with musical expressions such as "mbalax", a strong oral tradition and a cuisine based on local products such as millet, fish and groundnuts.

These elements can become points of convergence. For example, gastronomy as a cultural and economic product offers fertile ground for exchange. Peruvian cuisine, recognized for its fusion of techniques and

diversity of ingredients, could dialogue with Senegalese cuisine within the framework of gastronomic events, cultural festivals or culinary diplomacy programs. This type of activity allows not only the promotion of cultural identity, but also the positioning of local products, the fostering of tourism and the opening of spaces for creative industries.

Likewise, opportunities exist for educational and artistic cooperation. Cultural institutions and universities from both countries could develop academic exchange programs, art workshops, residencies for artists or joint research projects on heritage and development. This type of initiative not only strengthens ties between people but also contributes to building a shared vision of development from the Global South, based on the recognition of diversity and intercultural respect.

Culture, in this sense, should not be considered a decorative element of the bilateral relationship, but a central component of integration between Peru and Senegal, capable of generating trust, symbolic cohesion and a sense of belonging between both peoples.

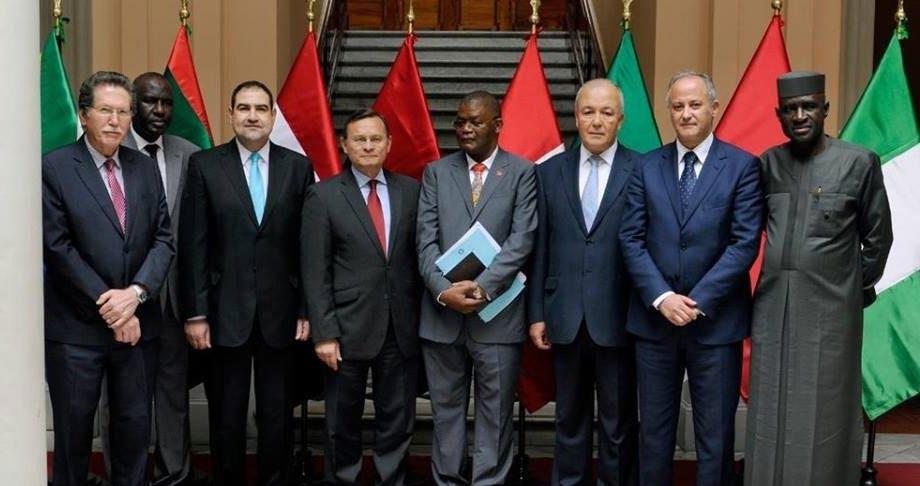

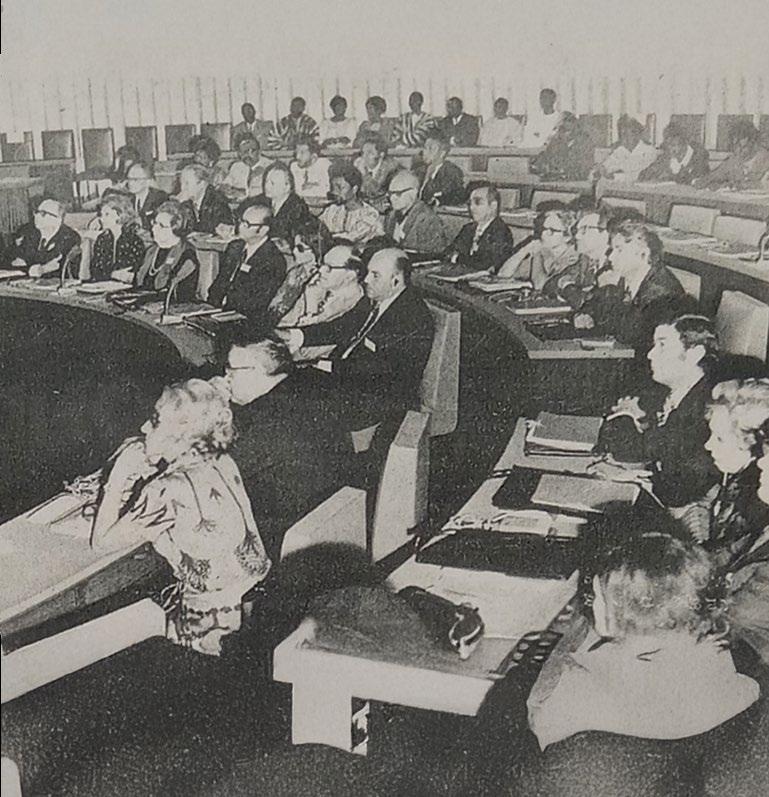

PERU-AFRICA FRIENDSHIP DAY WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF THE AMBASSADORS OF ANGOLA, ALGERIA, EGYPT, MOROCCO, MAURITANIA, NIGERIA, SENEGAL AND SOUTH AFRICA.

Source:Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peru

The potential deepening of relations between Peru and Senegal must be framed within a strategic vision of South-South cooperation, based on reciprocity, solidarity and mutual learning. Bodies such as the Peruvian International Cooperation Agency (APCI) and the Senegalese Cooperation Agency (SenCoop) can play a key role in identifying joint projects, especially if they are articulated with multilateral partners such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) or the UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime).

Likewise, the insertion of both countries in multilateral platforms can generate additional synergies. For example, Peru could integrate as an observer country in African Union forums related to agricultural development and climate change, whilst Senegal could participate more actively in the Pacific Alliance, promoting interregional dialogue. These instances would allow the sharing of successful policies, attracting responsible investment and exploring areas such as biotrade, renewable energies or community tourism, with a view to greater economic diversification.

Although still modest in quantitative terms, economic relations between Peru and Senegal are at a crucial stage of qualitative expansion. Mutual interest and affinity in sustainable development objectives open opportunities to build a deeper and more strategic alliance, underpinned by technical cooperation and the exchange of experiences.

Peru's trajectory in alternative development offers a conceptual and methodological framework adaptable to Senegal's challenges, whilst this African country represents a gateway for Peru to West Africa, a region of growing geoeconomic relevance.

Nevertheless, for these opportunities to materialize, it is essential to institutionalize cooperation and trade mechanisms through specific agreements, sustainable financing schemes and joint evaluation frameworks. Only in this way can a lasting economic

relationship be consolidated, one that contributes to greater economic justice between regions of the Global South and to the strengthening of more inclusive, resilient and sustainable development models.

DEVIDA. (2024). Memoria Institucional 2023. Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo y Vida sin Drogas.

Intracen (2023) Cooperativas agrícolas en Senegal impulsadas por insumos subvencionados y desarrollo organizativo productivo.

Trade Map / ITC (2023) Bilateral Trade Statistics between Peru and Senegal.

FAO (2022) Cooperación Sur-Sur y Triangular de la FAO 2022- 2025.

Miguel fernando córdova cuba MiniSter counSelor of the diPloMatic Service of the rePublic of Peru

"True revolution is not that which destroys, but that which builds"

The Human Being or "Homo Sapiens", as our species is known scientifically, appeared on the face of the Earth some 200,000 years ago [1], as the oldest remains found in Africa, more specifically in Morocco, would show thus far. This demonstrates that the origin of our species is undoubtedly the African continent, cradle of humanity, but not only of "Homo Sapiens" but of the numerous hominids that preceded it or that at some point came to coexist with it, in the long and impressive evolutionary process. Thus, the oldest remains, dated to about 2.5 million years ago [2]. Africa, indisputable cradle of humanity, not only saw the emergence of Homo sapiens, but also of its most remote ancestors.

These antecedents cannot be set aside when referring to this extraordinary continent, and observing the current reality of its inhabitants, their social and cultural, political and economic situation, amongst others, referring on this occasion to one of the westernmost countries of the African continent: Senegal.

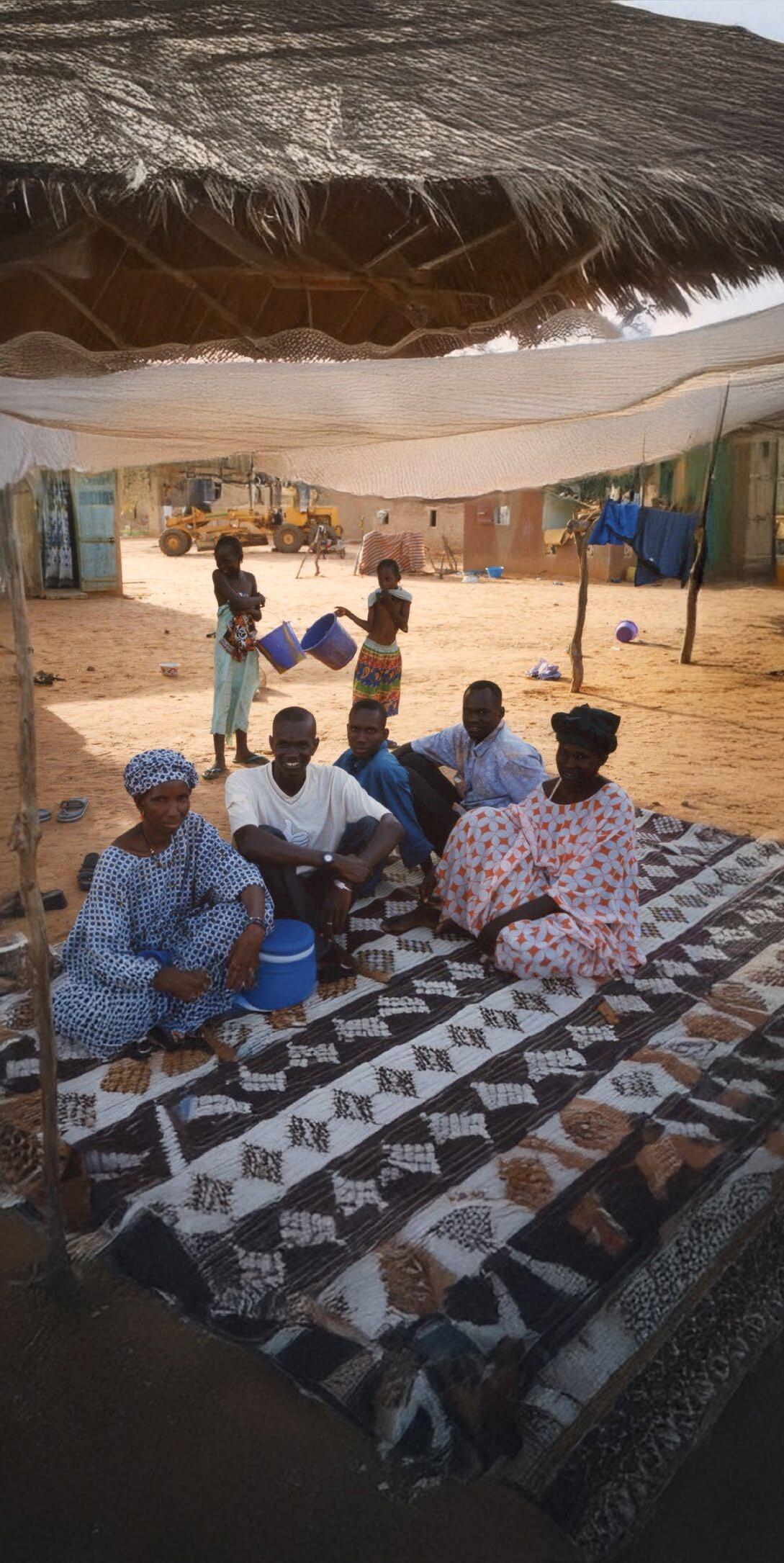

And when dealing with Senegal, reference will be made to a very particular cultural expression of its people: Senegalese hospitality or in Wolof, the language most spoken by its population: "Teranga". This cultural manifestation, deeply rooted in its population, is rather a philosophy of life, simple and not at all cumbersome, but very practical in its application by these friendly and hospitable people.

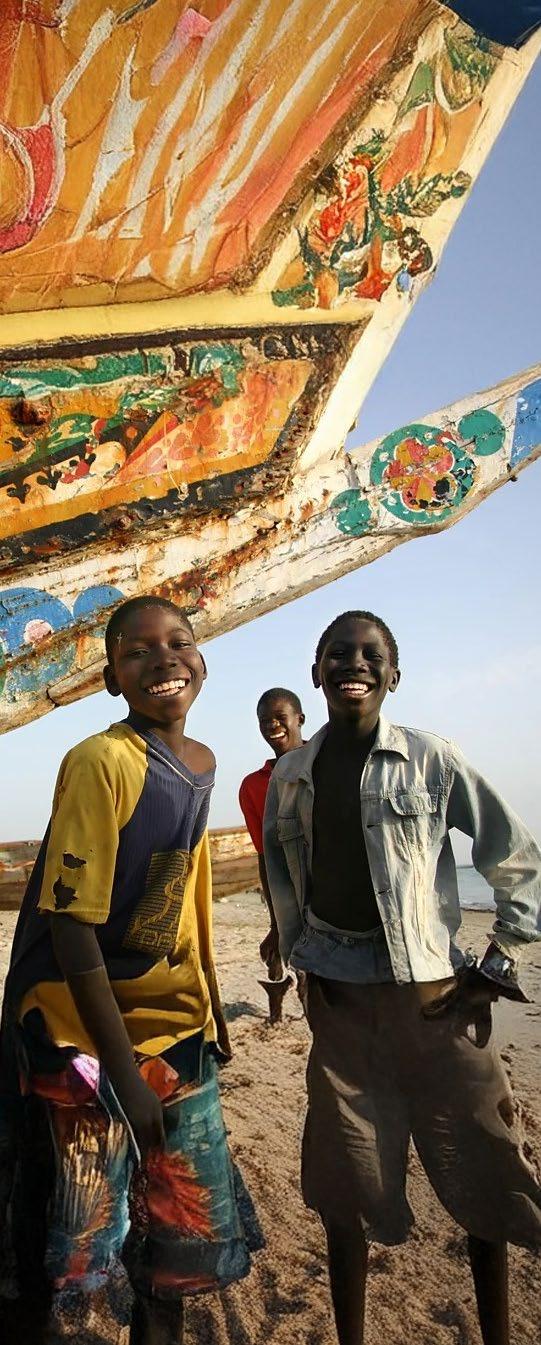

So, what is "Teranga"? [3] Well, it is an aptitude of this people, characterized by the warmth shown in their treatment of each other and which extends to visitors and foreigners, regardless of their origin. Strangers are treated as friends, and this aptitude goes beyond mere courtesy. It is a way of living that shows the generosity and community spirit of the Senegalese people.

Source: flickr.com

In every corner of that country, the visitor will be able to find a very particular warmth, with authentic smiles and displays of kindness. This hospitality manifests itself in different forms, thus, for example, offering their food, but it is not just a matter of giving the foreigner a place at the table, but rather seeking to make them feel almost like part of the family and in general this attitude manifests itself in every interaction with the visitor.

A series of verbal expressions make us see how deeply rooted “Teranga” is in the perception of the Senegalese inhabitant, which often surpasses in courtesy the usual expressions of politeness in the Western world. Thus, instead of thanking another person for a favor received with the familiar "you're welcome" of Western speech, the Senegalese use instead the expression "ngoko bokk", which means in their language: "we are together".

The welcome phrase to the home, translated from Wolof, would be: “today you are the owner of my house”, an expression of courtesy that surpasses any other from Western culture. This feeling of hospitality is not limited to the domestic sphere but extends to all spaces of Senegalese social life.

“Teranga”, a cultural manifestation, deeply internalized from childhood and transmitted generationally, constitutes an essential foundation of the educational and moral formation of the Senegalese people.

Source: visatravelcenter.com

A characteristic that makes “Teranga” unique is that it makes no distinction between people. It is practiced with family, with friends, with acquaintances and with complete strangers. In the Senegalese worldview, the other does not exist: all form part of the same community. If a foreigner travels through the most populated cities such as Dakar or Saint Louis and requests help from a local, they usually deviate from their path to ensure that the visitor reaches their destination. It is even possible to encounter a street vendor who offers you an infusion whilst patiently explaining the correct route.

“Teranga also manifests itself strongly in small villages, such as those in Bassari Country or in the Casamance region, where hospitality acquires an even closer and more intimate character [3]. In these environments, the visitor can be welcomed as another member of the community, invited to share traditional meals, participate in daily activities and even attend local ceremonies.

Being invited to a home and sharing the table with their typical meals is one of the most usual practices of “Teranga”. And what are these traditional meals like? [4] Well, first of all, it is important to specify that Senegalese cuisine is one of the best in West Africa, having a fusion of influences from France, Portugal, the Middle East and America. It is characterized by being a spicy, flavorful and very tropical cuisine. The most used ingredient is fish, which makes sense due to this country's proximity to the sea. The most consumed species vary considerably, from tuna, sole, grouper, barracuda, swordfish, amongst other marine species.

Source: planesconduende.com

The Senegalese are not particularly fond of consuming meat, although they do eat chicken as the most popular food of animal origin, though they also eat lamb, veal and goat. On the other hand, many of their dishes contain cereals such as rice, millet or fonio; or vegetables such as carrots, tomatoes, aubergines, cabbage, black-eyed peas (beans); as well as abundant fruit: mangoes, papayas, guavas, coconuts, pineapples, bananas, avocados, mandarins, dates, amongst others.

Regarding gastronomy or typical dishes, Thieboudinne is considered the Senegalese national dish, prepared with fresh and dried fish; but there is also Chicken Yassa, originating from the Casamance region; Caldou, Bassi Salte, Mafe, Lakhou Bissap, originating from central and western Senegal; Firire or Domoda, amongst the best-known dishes. Likewise, their pastries filled with fish stand out in this country's confectionery. Bissap is the most popular drink amongst the Senegalese.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org

This culture of hospitality has a historical origin, unfortunately linked to a dark and tragic period for the Senegalese people: colonization and the transatlantic slave trade. Like many other African populations, the ancestors of this nation were victims of that inhumane system. For approximately 315 years, European traffickers captured and traded men and women from various African regions, transporting them in ships through harrowing journeys, in which many did not manage to survive.

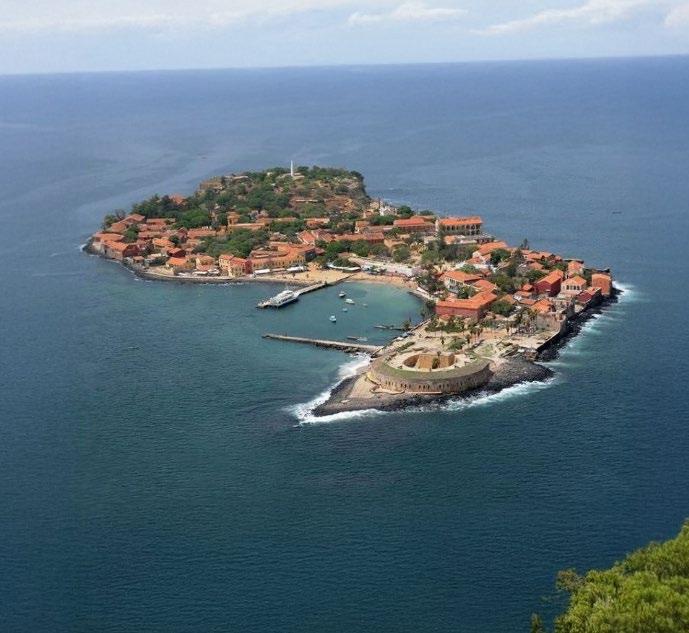

As a relevant witness to that era, the island of Gorée [5] is found in Senegal, situated less than four kilometers from the coast of Dakar and converted into a symbol of the transatlantic trade. From there, numerous ships departed with slaves towards America. The socalled "House of Slaves" is today a site of memory visited by hundreds of Afro-descendant tourists who seek to learn more about that tragic past. Thanks to studies such as those by Andrew Kahn and Jamelle Bouie, we now have a deeper understanding of this painful heritage.

After having been a French colony, Senegal achieved its independence in 1960. At the moment of constituting itself as a republic, the country presented notable internal diversity, marked by religious, ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences. In this context emerges the figure of its first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, who promoted the practice of "Teranga" as a social tool designed to build a national identity and foster solidarity amongst the different groups that make up the nation. Although this form of hospitality was not a creation of Senghor, his merit lies in having rescued and revalued this ancient custom—conceived in times of slavery—to integrate it into the republican project. That purpose appears to have been fulfilled successfully, as "Teranga" continues to be a living practice in contemporary Senegalese society.

As a legacy of the disastrous period of slavery, in Senegal there emerged a profound sense of communion and a willingness to share suffering as a form of collective resistance and cultural resilience. Far from feeding resentment towards the Europeans responsible for that drama, the Senegalese people responded with generous hospitality: they transformed pain into celebration, resentment into affection and injustice into solidarity. This hospitality is not only a cultural virtue, but a lesson in humanity and a philosophy of life made practical from which the West can still learn.

Furthermore, Teranga has been recognized not only as a popular virtue, but also as a diplomatic tool and means of international projection. Senegal has managed to build a positive image abroad, partly thanks to this cultural tradition that attracts travelers, researchers and multilateral organizations. In a world marked by polarization, the Senegalese model of welcome represents an alternative based on dignity, mutual respect and recognition of the other as an essential part of the community.

In conclusion, "Teranga" is not only a hospitable custom, but a profound expression of the history, philosophy of life and national identity of the Senegalese people. Born from pain, strengthened in diversity and projected as an example of coexistence, this Senegalese social fabric of hospitality embodies ancestral wisdom that invites the world to rethink the way we relate to others.

REFERENCES:

[1] National Geographic (2022), “¿Cuál es el origen de la humanidad según la ciencia?”. In Historia, National Geographic Society. Washington, DC.

[2]Harari, Yuval Noah (2022), “Un animal sin importancia”. In De animales a dioses - Breve Historia de la humanidad (p. 16). Buenos Aires: Debate.

[3] Website: Planes con duende (2025). “Senegal”. In agencia de viajes Planes con Duende, Sevilla.

[4] Website: Senegal.es (2023), “Sabores de Senegal: Gastronomía y recetas tradicionales”.

[5] UNESCO (2024), “Gorée, la isla de la memoria”. In El correo de la Unesco, Paris.

Julio Antonio ubillús RAmíRez Counsellor of the DiplomatiC serviCe of the republiC of peru

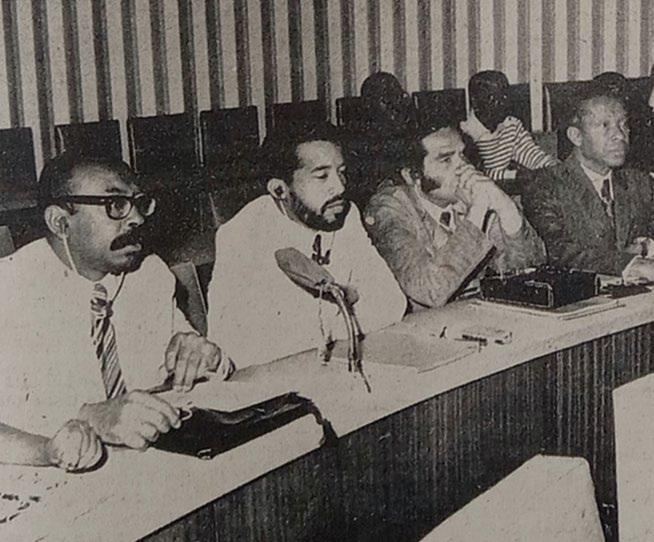

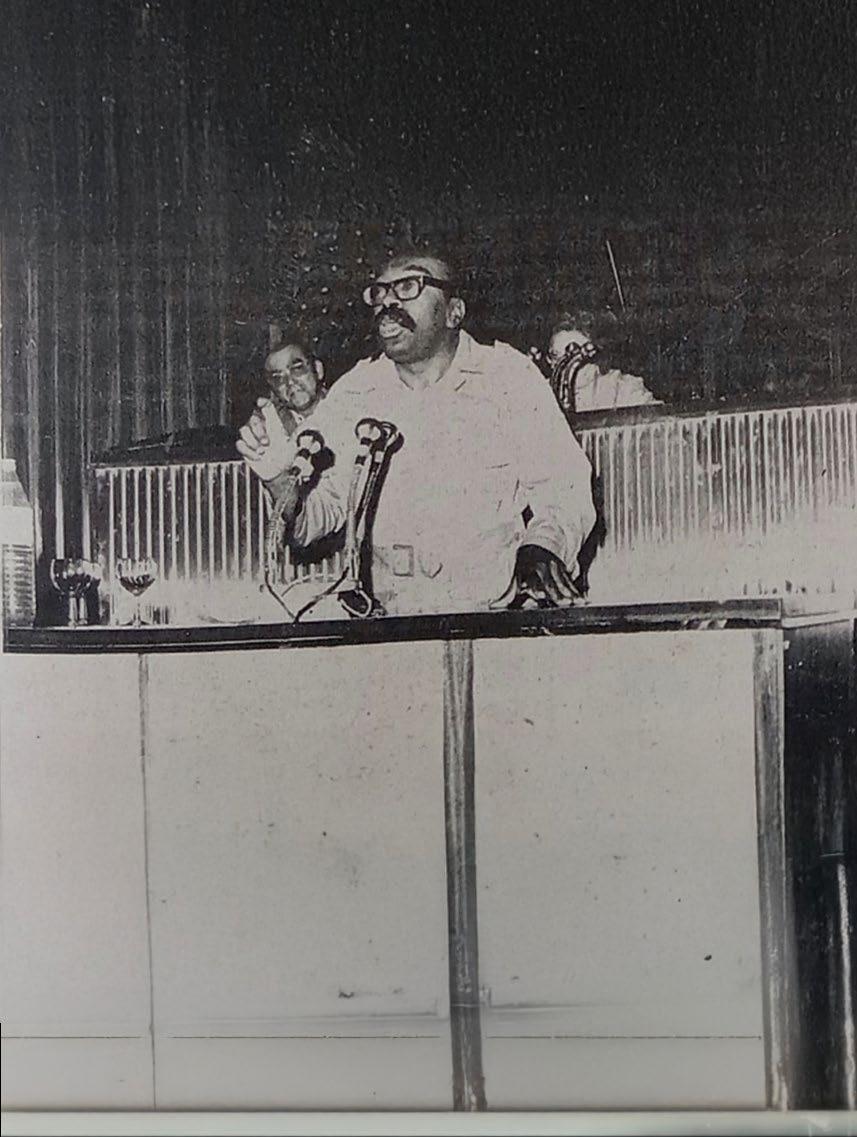

In January 1974, the distinguished poet and writer Léopold Sédar Senghor, then President of Senegal, promoted from his government the initiative to celebrate in the city of Dakar the international conference entitled “Négritude et Amérique Latine” (Negritude and Latin America). The event, the first of its nature held in Africa, was organized by the Centre for Afro-Ibero-American Higher Studies of the University of Dakar and represented at that time an innovative effort to link Africa and Latin America through common bonds in the historical, cultural and intellectual spheres, fostered thanks to the contributions of the Afrodescendant diaspora.

The thematic proposal of the conference, animated by the concept of "negritude", whose definition would evolve and be presented in 1980 by President Senghor himself as "the ensemble of values of the black world... which surpassed its initial literary approaches to become a form of culture, in the authentication, in the identification of black culture" (Ansón, 1980), generated great interest in Latin America particularly amongst thinkers and artists specialized in the subject.

In this way, the conference “Négritude et Amérique Latine” sought to promote shared reflection and vision on the extensive cultural legacy inherited from Africa by Latin America, as well as on the sensitive historical process of slavery and its effects on both sides of the Atlantic, with the objective of generating a new space for cohesion and strengthening of the already historic and broad ties existing between both continents and their countries (Bournot, E. 2022. Pp. 77 & 78).

Some of the most distinguished Latin American attendees were Nobel Prize for Literature winner Miguel Ángel Asturias from Guatemala, Leopoldo Zea from Mexico, Angelina Pollak-Eltz from Venezuela, Luis Adolfo Siles

Salinas from Bolivia, Manuel Zapata from Colombia, Pablo Mariñez from the Dominican Republic, Clóvis Moura from Brazil and Benjamín Pinto Bull from Guinea-Bissau (Devés, E. 2023).

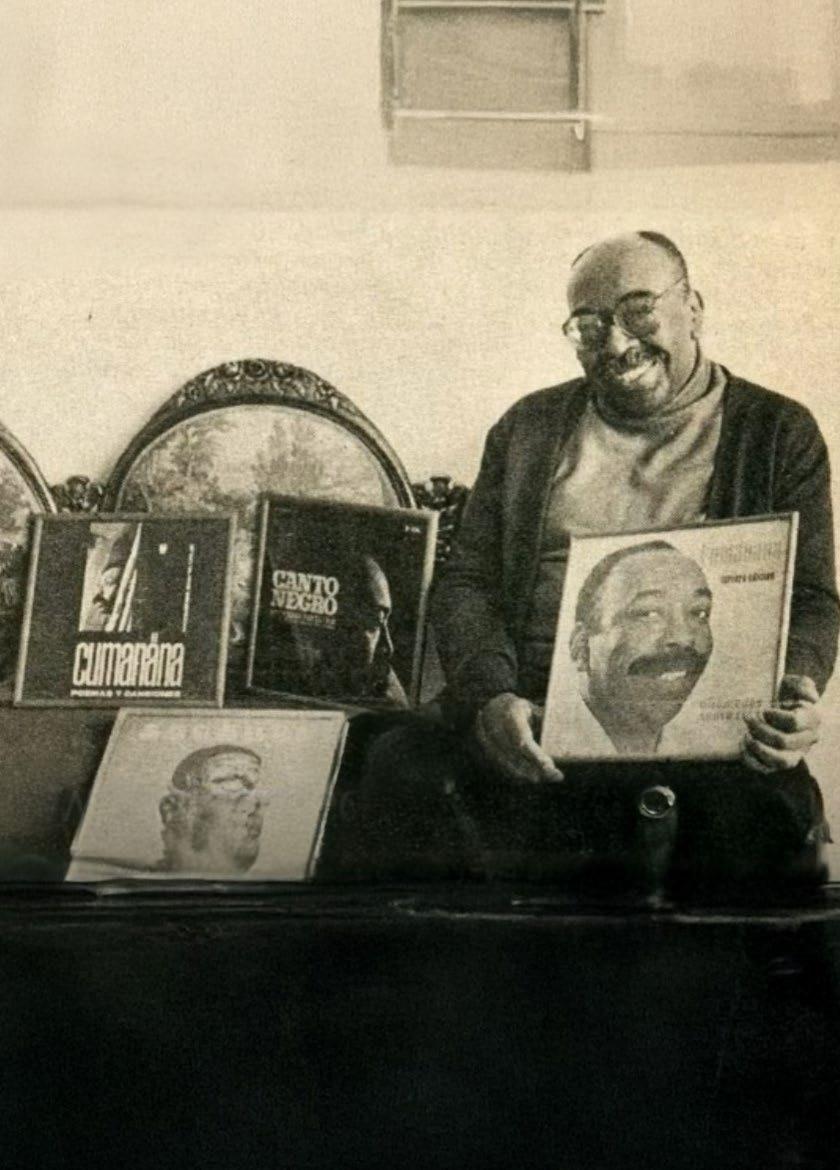

The conference, which lasted five days, reserved a space for Nicomedes Santa Cruz, through his presentation “Contributions of African Civilizations to Peruvian Folklore”, to present in Senegal outstanding elements of our AfroPeruvian culture, and share his reflections on the African origins and influences in its gestation, development and consolidation.

The beginning of his intervention could perhaps illustrate the motivations for his journey to Dakar and his presence at the meeting. In this regard, and according to what is gathered from his intervention, the value of the conference, rather than serving as a framework for presenting a list of facts and speculations about the African heritage present in Peru, went beyond and rested rather on the opportunity that the colloquium had to serve as a space to evaluate precisely the significance of this linkage, both within African culture, as well as from its influence on our culture (Santa Cruz, N. 1974, p. 370).

With that objective, Nicomedes Santa Cruz presents reflections and arguments that highlight the worth of cultural and artistic manifestations inherited from Africa and transmitted to Peru through the Afro-descendant community. Likewise, he highlights with concrete examples the determining role that this played in various historical processes developed in our country in the demographic, political and economic sectors, as well as in the spheres of dance, music, gastronomy and faith, amongst others.

Regarding the objective of his speech, that is to say, to sustain the validity of African cultural influence in living cultural traditions in Peru, Nicomedes Santa Cruz shares with the attendees documented accounts, oral traditions, historical facts, records of the use of musical instruments, and uses and customs related to dance and music, collected from the mid-17th century (Santa Cruz, N. 1974, pp. 375, 376 & 377).

Based on these, Mr. Santa Cruz refers to the presence in the mid-17th century of African-origin dance practices present in Zaña —in northern Peru— and amongst which he highlights the lundú, to share his reflections on the processes that generated its disappearance, giving way to the emergence of the tondero as its heir. Similarly, he presents a set of arguments about a similar evolution that develops in the case of the landó and the influence that it had, together with other musical traditions already present in our country, in the gestation of the zamacueca, which would later be renamed as marinera [1] (Santa Cruz, N. 1974, pp. 379 & 380) (Rocca Torres, L. 2024, pp. 153 to 155).

Nicomedes Santa Cruz also made sure to make known to the attendees of the event in Senegal the importance that the locality of Zaña and its population had in the development of Afro-Peruvian culture in our country, a locality that years later —precisely in 2017— would be the first in the Pacific Ocean to be recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a “Site of Memory of Slavery and African Cultural Heritage” (Ministerio de Cultura, 2017).

The work “Nicomedes Santa Cruz, Zaña y África” by Peruvian sociologist Luis Rocca Torres, contains a set of interviews and testimonies that present an idea of the importance that the journey to Dakar had in the life of Nicomedes Santa Cruz (Rocca Torres, L. 2015, pp. 40 to 45).

Regarding the conference “Négritude et Amérique Latine”, it could be highlighted that it would represent for Mr. Santa Cruz a valuable opportunity to share, in a conference held symbolically in Africa and before a distinguished audience of international personalities expert in the subject, a Peruvian reading of the strong historical and cultural ties that united Africa and Peru in the past, as well as his reflections on the validity of these ties in various cultural representations still alive in our country, specifically in the musical and dance arts.

The work of Nicomedes Santa Cruz to make known in our country the relevance of the conference should also be highlighted.

In this regard, through the column “La Página de Nicomedes” in the newspaper “La Nueva Crónica”, Mr. Santa Cruz himself would publish four instalments entitled “Coloquio sobre la Negritud y América Latina” (20 January 1974), “Negritud y América Latina” (27 January 1974), “Negritud y América Latina (III)” (3 February 1974) and “Negritud, Toma de Conciencia (IV)” (10 February 1974). In these publications, he would present to his national readers personal assessments of his journey to Senegal, also reporting on the details of the conference’s evolution, and sharing fragments of the speech he presented representing Peru (Santa Cruz, N. 1974).

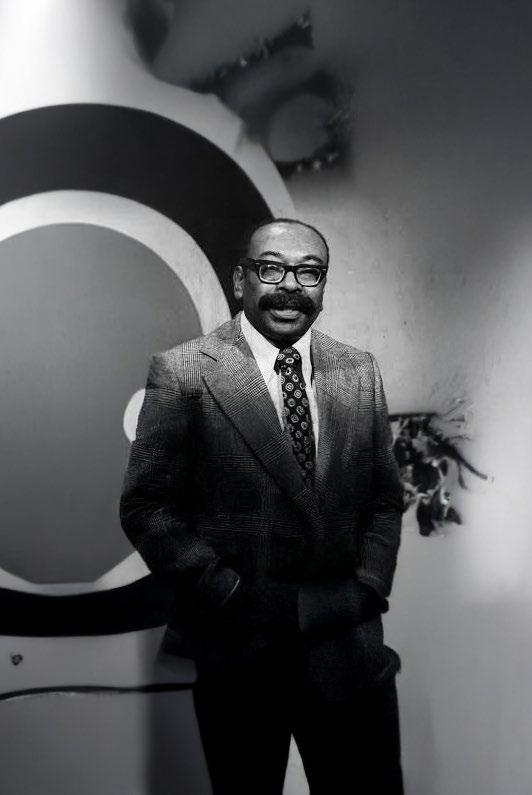

Nicomedes Santa Cruz undoubtedly represents one of the most relevant voices and personalities in our recent history. His active and committed work executed through cultural action, poetry, music, journalism and archival work, amongst others, has helped to recover, understand, revalue and disseminate valuable elements of our AfroPeruvian heritage.

From a broader perspective, and in the context of Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor's initiative to establish new bridges of dialogue and intellectual and cultural exchange between Africa and Latin America, Nicomedes Santa Cruz’s participation in the international conference “Négritude et Amérique Latine” represented a unique opportunity to make known in Africa relevant cultural elements of our Afro-Peruvian heritage.

Thus, Mr. Santa Cruz took advantage of the space granted to him at the conference in Dakar to address the attendees, and speak to them of the lando, the tondero and the marinera, of the donkey’s jaw and the cajón, of the Lord of Miracles and San Martín de Porres, all valuable elements that form part of Peru’s culture. This act represented a valuable cultural contribution, generating at that time a renewed link between Peru and —through Senegal— Africa.

Having recently celebrated —on 4 June 2025— AfroPeruvian Culture Month and the Centenary of Nicomedes Santa Cruz’s Birth, it is worth highlighting the posthumous recognition “Order of the Great Masters of Peruvian Culture” [2] that was granted to him by the Peruvian State, as testimony and recognition of his “legacy as an indispensable reference for new generations and a powerful tool for public policies in matters of memory, justice and diversity” (Ministerio de Cultura, 2025).

[1] In his work “Malambo: Historia y Artes del Primer Barrio Afroperuano de Lima”, Luis Rocca Torres explains the transition process from zamacueca to marinera, citing in detail the variations and adaptations of instruments, styles and dance steps, as well as the campaign carried out by Mr Abelardo Gamarra “El Tunante” during the last third of the 19th century, to change the name from zamacueca to marinera in the context of the War of the Pacific.

[2] In 2024, the Government of Peru through the Ministry of Culture created the recognition “Order of the Great Masters of Peruvian Culture”, with the purpose of rewarding and distinguishing those personalities in our history who have committed their lives to promoting and revaluing various elements that form part of the Nation’s Cultural Heritage.

REFERENCES:

Ansón, L (1980, 12 November). Leopold Senghor: “Negritude is the ensemble of values of the black race” [online]. Retrieved 4 June 2025 from https://elpais.com/diario/1980/11/12/internacional/342831608_850215.html?event=go&event_ log=go&prod=REGCRART&o=cerrado

Bournot, E. (2022). Négritude et Amérique Latine: From the Black South Atlantic to the Third World. Comparative Literature Studies, Volume 59, Number 1 (pp. 77-93). Pensilvania, Estados Unidos: Penn State University Press.

Devés, E (2023). Redes intelectuales Sur-Sur: trayectorias y propuestas hacia el futuro [online]. Retrieved 4 June 2025 from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/9048592.pdf

Ministerio de Cultural de la República del Perú (2025). Resolución Suprema Nº 012-2025-MC: Otorgan, a título póstumo, el reconocimiento Orden de los Grandes Maestros de la Cultura Peruana al señor Nicomedes Santa Cruz Gamarra, en la subcategoría promoción de los derechos del pueblo afroperuano. 4 June 2025.

Ministerio de Cultura de la República del Perú (2025). Nota de prensa “Zaña es reconocido por la UNESCO como Sitio de Memoria asociado a La Ruta del Esclavo: resistencia, libertad, patrimonio” [online]. Retrieved 6 June 2025 from https://www.gob.pe/institucion/cultura/noticias/5159-zana-es-reconocido-por-la-unesco-como-sitio-de-memoria-asociado-a-la-ruta-del-esclavo-resistencia-libertad-patrimonio

Rocca Torres, L. (2015). Nicomedes Santa Cruz, Zaña y África. Lima, Perú: Centro de Desarrollo Étnico – CEDET

Rocca Torres, L. (2024). Malambo: Historia y Artes del Primer Barrio Afroperuano de Lima. Lima, Perú: Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Santa Cruz, N. (1974). Aportes de las Civilizaciones Africanas al Folklore del Perú. Ponencia presentada en el coloquio “Négritude et Amérique Latine”. Dakar, Senegal [online]. Retrieved 4 June 2025 from https://www.nicomedessantacruz.com/ponencias.

Santa Cruz, N. (1974). La Página de Nicomedes. En La Nueva Crónica. Lima, Perú [online]. Retrieved 5 June 2025 from https://www.nicomedessantacruz.com/ponencias.

WAlteR AndRés zumARán dávilA

seConD seCretary in the DiplomatiC serviCe of the republiC of peru

On 4 June 2025, the centenary of the birth of Nicomedes Santa Cruz Gamarra (1925-1992) was celebrated, one of the most distinguished Peruvian intellectuals of the 20th century—perhaps the greatest representative of Afro-Peruvian identity of his time. A multifaceted thinker, his career was marked by a constant inquiry into and dissemination of African roots in Peru, in dialogue with other forms of popular identity. From the 1950s onwards, Nicomedes developed a role that, without renouncing humor or the rhythm of the décima, brought into national debate the racial and cultural situation in which the Afrodescendant population in Peru found itself.

Taking advantage of the fact that this edition of Cumanana magazine is dedicated to the Republic of Senegal, I would like to highlight Nicomedes Santa Cruz’s participation in the Coloquio Négritude et Amérique latine, convened by the then President of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor; which took place in the city of Dakar between 7 and 12 January 1974. This event, in the words of researcher Estefanía Bournot (Négritude et Amérique latine: From the black south Atlantic to the Third World), “originated an international cultural diplomacy articulated around the idea of 'racial fraternity' and Third World solidarity”.

As the first international gathering of such magnitude in his career, the Colloquium represented a milestone for him. In Dakar, Santa Cruz not only shared his research on Afro-Peruvian culture with representatives from Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, but also witnessed a space where the African element was not merely another contribution, but a living and recognised presence: the central axis.

In these lines we shall examine Nicomedes’s path to Dakar, the cultural and international significance that this colloquium held for him, and how this experience consolidated in him a more transnational vision of négritude.

To understand the vital and intellectual origins of Nicomedes Santa Cruz, I shall refer to a column by Hugo Neira Samanez published in the newspaper Expreso (6 April 1964), entitled Otra sorpresa en Nicomedes: A lo universal por lo negro:

"We all know that the Santa Cruz Family is a phenomenon due to the variety of artistic personalities it has offered the country [...] Nicomedes, the youngest of all these family geniuses, was a blacksmith for 18 years of his youth and maturity. But the family fire forged a temperament whose simple and felicitous handling of [language] required no academies [...], and when the opportune moment arrived, Nicomedes the blacksmith became, without upheavals, Nicomedes the decimist."

Nicomedes Santa Cruz, born on 4 June 1925, was the ninth of ten children of Nicomedes Santa Cruz Aparicio and Victoria Gamarra Ramírez. The passion for Afro-Peruvian culture and art, we know, came to him from home.

Nicomedes senior was a playwright and, once the family was settled, earned his bread as an industrial mechanic—a trade he had learnt during his prolonged stay in the United States. Regarding Doña Victoria Gamarra, Nicomedes junior recounts that, whilst working as a washerwoman, she would spend the day singing various musical genres of Afro-Peruvian origin, amongst them the décima.

Having completed five years of primary education, in 1936, at the age of eleven, Doña Victoria introduced him to master locksmith Nicanor Zúñiga to learn the blacksmithing trade; an occupation he would pursue for twenty years. Nicomedes — the son — even opened a workshop in the family home in 1953, which he would leave in charge of his family three years later.

It was at the end of the 1940s that Nicomedes met Porfirio Vásquez, “The Patriarch of Black Music.” It was Don Porfirio who introduced him to the world of décimas, a literary-musical genre whose tradition was already becoming extinct, and to which he had already been exposed in his childhood through his mother's voice.

Nicomedes, from that point onwards, became a disciple of Porfirio Vásquez, even coming to surpass his master— this in Santa Cruz’s own words. Thus, in 1956, he decided to leave the blacksmith's workshop he had established himself and travel throughout the country to "find his destiny." Nicomedes recounts that he would go from village to village improvising poems and, incidentally, collecting the oral traditions of said villages.

It was in 1957 when Nicomedes began to carve out a place for himself in the Peruvian arts. First, participating with the "Pancho Fierro" Company in performances in Lima, Arequipa and Chile. Then, in October, he participated in the record "Gente Morena." And in November, he made his début on radio.

It was barely a year later, in 1958, that he achieved national recognition through his participation on radio and television, combined with a text that Sebastián Salazar Bondy wrote about him. That same year, Nicomedes established himself as a cultural promoter and disseminator of Afro-Peruvian arts by founding the "Cumanana" Ensemble, which would mark the beginning of his sister Victoria's career.

Already by reason of the publication of his book Décimas in 1959, the newspaper El Comercio (25 December 1959) noted:

"As for the content, Santa Cruz’s verse is unnecessary to praise them anew: this is an artist consecrated directly by the people."

Amidst the debate between a cultural affirmation or a political vindication of négritude—a debate that would also be reflected in the Dakar Colloquium—Nicomedes drew from both Source:s. Recognizing the structural inequality of the Afro-descendant, he dedicated himself to rescuing the influence of African culture in Peruvian society, whilst continuing to engage in social criticism, even in his literary compositions.

The 1960s would mark a political inclination towards protest in Nicomedes Santa Cruz's production, which would even generate a fleeting foray into politics and discontent within him. This led him in 1963 to make the decision to go to Brazil, where he met the writer and ethnologist Edison de Souza Carneiro, who specialized in Afro-Brazilian culture. Two months later, in August, he returned to our country with all the experience and knowledge acquired in Brazil.

In Cumanana (1964), in keeping with his early texts, Nicomedes vindicated Afro-Peruvian history with accessible and direct language. In this regard, the newspaper Expreso (4 April 1964) highlighted:

"Who does not know Nicomedes? Who has not heard one of his décimas at some point? Perhaps he is the only Peruvian writer who can afford to print 10,000 copies of a book of verses, as he has just done. Verses are not usually for the great masses, but Nicomedes—a popular poet— writes them for the masses and knows how to make them reach them."

Nicomedes positioned himself as an intellectual, artist and disseminator of Afro-Peruvian culture through his research, his décimas, and his stage productions, as well as his participation on radio. Indeed, together with his sister Victoria, he reconstructed an Afro-Peruvian heritage that had until then been largely ignored. From what we can appreciate in his texts, his worldview began to be constructed from the combination of vindication and integration: he defended Peruvian mestizaje from a critical approach, in which he underlined the importance of recognizing the contribution of the Afro-Peruvian population.

The invitation to the Colloquium found, therefore, Nicomedes Santa Cruz at a stage of intellectual maturity and with recognition from Peruvian society for his contribution. Dakar signified, in these circumstances, not only a geographical destination, but the beginning of a civilizational dialogue that would contribute to defining his place in the world.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz was first contacted in 1973 by Dominican sociologist Pablo Maríñez, who between 1971 and 1975 resided in Peru dedicated to university teaching—years later he would represent his homeland as Ambassador to Mexico and Chile—to present him with the opportunity to participate in the Colloquium Négritude et Amérique latine: an encounter between intellectuals, artists and academics of African descent from Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa. This invitation and their joint participation in Dakar would mark the beginning of a relationship that would extend over the years: not only did they maintain epistolary contact throughout Santa Cruz's life, but Maríñez would also write the book Nicomedes Santa Cruz; decimist, poet and AfroPeruvian folklorist (Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima, 2000).

Let us first situate ourselves in time and space: In Peru, since 1968 we found ourselves in the so-called Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces headed by General Juan Velasco Alvarado—a government that would come to an end in August 1975 following the Tacnazo of General Francisco Morales Bermúdez. In Senegal, Léopold Senghor governed, having been elected first president of the nascent republic in 1960—a government that would extend until 1980. Both countries had in common, amongst other things, their membership of the Non-Aligned Movement, whose Conference of Foreign Ministers would take place in Lima in August 1975.

Precisely, Senghor forms part, along with intellectuals Aimé Césaire and Léon Damas—and drawing upon contributions from personalities such as the sisters Paulette and Jeanne Nardal— of the creation of the concept of négritude in 1930s France, as a project that sought to forge a common identity for the Afrodescendant population.

It is thus that one can understand President Léopold Senghor's convening of the colloquium Négritude et Amerique latine as the first opportunity in Africa in which the Afro-descendant intelligentsia of Latin America and the Caribbean would meet with representatives of the African continent to establish a dialogue between both peoples.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz thus narrates his expectations for the journey (La Página de Nicomedes: Coloquio sobre la Negritud y América Latina. Diario La Nueva Crónica, 20 January 1974):

“Aboard the 'jet' that was taking us from Rio to Dakar, my travelling companion, Pablo Maríñez, sociologist, professor at the University of San Marcos and black like me, was pondering taciturnly. [...] we both knew perfectly well what the other was thinking: The return to the Motherland! ... To set foot on African soil again after four centuries. To have departed by caravel and returned by aeroplane. Slave ships with five decks [...] Suddenly,

the air hostess passes us each a glass of orange juice and as we stretch out our arms, we see our wrists free of shackles, although the jingling of chains persisted in our ears.”

On that occasion Nicomedes presented the paper "Contributions of African Civilizations to Peruvian Folklore", in which he defended with clarity and conviction the centrality of the African component in Peruvian culture, particularly in the realm of coastal folklore. Through a historical survey, he identified the African presence in musical genres such as the marinera, the landó, the panalivio and the zamacueca. He pointed out that many of these elements, deeply rooted in the daily life of the Peruvian people, were the direct result of the contribution of Afro-descendant communities brought to Peru in conditions of slavery. His paper was not only descriptive in character, but also vindicatory: Santa Cruz claimed full recognition of these expressions as part of the country's cultural heritage and of the legacy of African civilizations in America.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz's participation allowed for the establishment of bridges between Afro-American experiences and their cultural origins in Africa, articulating the cultural heritage originating from the "Motherland"— an expression that Santa Cruz himself used to refer to the African continent—with Afro-Peruvian dances. Thus, he reaffirmed his position not only as a poet and folklorist, but also as an Afro-Peruvian intellectual with an active voice in debates about négritude, cultural identity and historical memory on the American continent.

Taking as a basis the creation of the “Association of AfroLatin American Studies”, approved by the participants in the Colloquium, Nicomedes, as soon as he returned to Peru, sought to establish an "Institute of Afro-Peruvian Studies" in Lima, a project he would reformulate as a "Journal of Afro-Peruvian Studies". Both ideas were decidedly supported by his new friend Pablo Maríñez, although regrettably neither came to fruition.

Nevertheless, the impact of Dakar on Nicomedes was lasting. From then onwards, his intellectual and artistic production took a turn towards a more international view of Afro-descendant culture. The experience in Africa led him to reaffirm the existence of a common trunk in Afro-American cultural expressions, beyond their local particularities. This transnational perspective impelled him to establish new links with artists, researchers and activists from different parts of the world, enriching his vision of négritude and its place in historical development.

Nicomedes never ceased to allude to that experience in Dakar as a transcendental moment. The paper he

presented in 1974 was, in that sense, a taking of position: the African legacy should not be merely a matter of folkloric study, but an active part of reflection on history, politics and identity in Latin America.

The Dakar Colloquium, therefore, marked for Nicomedes Santa Cruz not only international recognition of his work, but a personal and political reaffirmation of his commitment to the history and culture of Afro-descendant peoples. In it were interwoven his biography, his cultural activism and his vocation as a bridge between continents. It was, in sum, the meeting point between a personal search—for one’s own identity—and a collective project of dignification and memory.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz dedicated himself to many things throughout his life: He was a writer, radio announcer and presenter, decimist, promoter of the arts, academic researcher, and activist for Afro-Peruvian identity. All of this revolved around an aspiration that guided him throughout his life and professional experiences: the vindication and resurgence of Afro-Peruvian culture.

Nicomedes’s work has enabled us to continue speaking today of African influence in our country. By linking the past with the richness of the present, Nicomedes not only made visible a marginalized heritage: he set it dancing with force at the center of our national imagination.

It is also important always to remember, alongside Nicomedes, the valuable contribution that his sister, Doña Victoria Santa Cruz, made to Peruvian culture through the rescue of AfroPeruvian dances and cultural expressions, which enabled these to reach our present day.

This document could not conclude without acknowledging the valuable contribution of Nicomedes Santa Cruz’s descendants: Mercedes, Luis Enrique and Pedro, who through the website www.nicomedessantacruz.com have bequeathed us an extensive and detailed bibliographical collection about their father’s life.

claudia giuliana betalleluz otiura MiniSter in the diPloMatic Service of the rePublic of Peru.

“FROM AFRICA CAME MY GRANDMOTHER DRESSED IN COWRIE SHELLS, THE SPANIARDS BROUGHT HER IN A CARAVEL SHIP. THEY BRANDED HER WITH FIRE, THE CARIMBA WAS HER CROSS. AND IN SOUTH AMERICA TO THE BEAT OF HER SORROWS THE BLACK DRUMS GAVE RHYTHMS OF SLAVERY”.

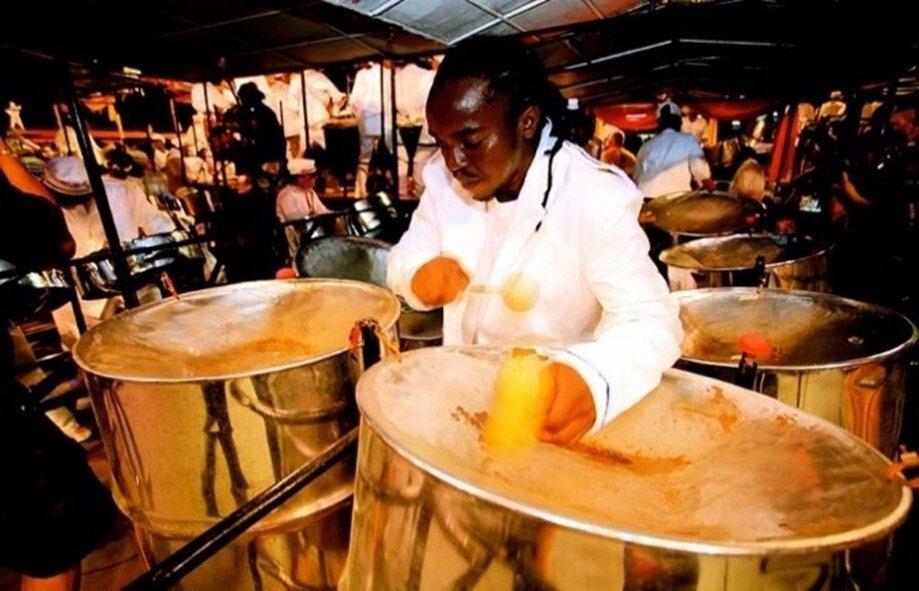

In America, there exist musical instruments whose history dates to the slaves brought from Africa between the 15th and 19th centuries, and to the subsequent prohibitions of their drums. One of them is the steelpan, or metal drum of Trinidad and Tobago, a symbol of the Caribbean Island that has transcended the musical sphere to become a cultural ambassador of its country to the world.

The drums used by enslaved people not only accompanied their long working days but also played a fundamental role in their religious ceremonies and cultural expressions. Furthermore, they had a crucial impact on the revolts that arose in America from the 8th century, when slaves fought against abuses and yearned for freedom. The Stono Rebellion, which occurred in September 1739 in the English colony of South Carolina, was one of the most representative: in it, slaves used drums as a tool for communication and coordination. Other uprisings also occurred in various regions of the continent.

In the Caribbean, European colonial authorities, aware of the power of drums and other African instruments as tools of communication and unity, prohibited their use on various islands to reduce the risk of insurrection. Similar restrictions were implemented in Brazil, suppressing musical practices of African origin, including percussion and rhythms linked to religious ceremonies. In the Spanish colonies, it was the Catholic Church that prohibited the use of drums by slaves. A similar situation occurred in the French colonies, especially in Saint-Domingue (presentday Haiti), where in August 1791 a coordinated uprising began which, after a twelve-year struggle, led to Haiti's independence.

In response to slave uprisings, colonial authorities implemented a series of restrictions to limit the use of drums and other African cultural expressions. These prohibitions sought to prevent drums from being used as an effective means of communication amongst enslaved Africans, avoiding the transmission of complex messages over long distances. They also aimed to suppress African cultural practices and identities, cutting slaves' links with their heritage, their traditions and their social cohesion,

which facilitated their control and assimilation into the dominant culture. Another motive behind these restrictions was the fear of unity. Drumming sessions were community events that brought enslaved Africans together, even though they came from different ethnic groups, fostering shared identity. Slaveholders feared that these gatherings could inspire revolts.

However, these prohibitions spurred creativity and adaptation within the population of African origin, generating new forms of creating music and preserving their cultural heritage. In response, body percussion emerged, such as clapping and foot stamping, a practice widely spread throughout America. New musical instruments were also developed. Despite the restrictions, Afro-Americans continued using music as a tool for resistance, communication and cultural preservation. The legacy of African percussion, with its rhythms and community meaning, endured and evolved, profoundly influencing the music and cultural identity of the African diaspora throughout America.

In Trinidad and Tobago, towards the end of the 19th century, disturbances that occurred during carnival celebrations led colonial authorities to re-establish the prohibition on percussion instruments. Faced with this measure, the population of African descent resorted to using bamboo tubes instead of drums, since striking them against the ground produced similar sounds. This practice continued in carnival festivities until the end of the 1930s, with the characteristic Tamboo-Bamboo ensembles, which paraded in street processions accompanied by brass and string instrument bands.

Over time, new elements were incorporated into these groups, such as biscuit tins used as percussion instruments. These rudimentary metal drums marked the path towards the development of the steelpan, the emblematic national instrument of Trinidad and Tobago, which has since evolved, giving rise to a variety of instruments with different tonal ranges that make up modern steelbands.

Musicians discovered that by striking the tins, originally convex, they produced musical notes but soon noticed that they could expand the sound register by making them concave.

The first steelpans had a limited range and were played with sticks or with bare hands. However, the search for innovation led to the discovery of the steel drum, a more durable and versatile instrument. Initially used to store petroleum, this drum evolved until it became the most representative musical symbol of Trinidad and Tobago.

In July 2024, the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago unanimously approved the Act for the designation of the steelpan as the national musical instrument of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. In February of this year, the steelpan officially replaced the three caravels on the national coat of arms, consolidating its place as a cultural emblem of the country.

Although the steelpan was developed in the 20th century, its essence goes far beyond its era. It stands as a symbol of rebellion, resilience and creativity, reflecting the indomitable spirit of African descendants in Trinidad and Tobago. Its sound is an echo of the past, recalling the harsh reality of slavery, but also the strength of those who, despite oppression, never lost their cultural roots.

LEARN THE ART OF PLAYING THE STEEL PAN IN TRINIDAD

Source:tripjive.com/learn-the-art-of-steel-pan-drumming-in-trinidad/

REFERENCES:

History of the Steelpan. (s.f.). En Caribbeanz. Recuperado de www.caribbeanz.org/history-of-thesteelpan

Steelpan & Slavery: A Story of Rhythm, Rebellion, & Resilience. (2023, 31 de julio). En Exceptional Caribbean. Recuperado de https:// exceptionalcaribbean.com/2023/07/31/steelpanslavery-a-story-of-rhythm-rebellion-resilience

Mintz, S. (s.f.). Historical Context: Facts about the Slave Trade and Slavery. The Gilder Lehrman Institute. Recuperado de https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ history-reSource:s/teacher-resourcs/historicalcontext-facts-about-slave-trade-and-slavery

Santa Cruz, N. (1971). Ritmos Negros del Perú. Buenos Aires. Editorial Losada.

Smith, C.D. (2024). History and Impact of Drum Bans on African American Music. Patterson’s Community.

Warner-Lewis, M. (2007, marzo). African Heritage in the Caribbean (2nd Part). National Library, Trinidad and Tobago. Recuperado de www.africaspeaks.com

La prohibición eclesiástica de los tambores africanos en el Perú que dio como resultado la creación del cajón flamenco. (s.f.). En Marchena Secreta. Recuperado de https://marchenasecreta.com/la-prohibicioneclesiastica-de-los-tambores-africanos-en-peruque-dio-como-resultado-el-cajon-flamenco

luiS Miguel rodríguez chacón MiniSter in the diPloMatic Service of the rePublic of Peru.

Alternative development has positioned itself as a fundamental tool to address complex issues such as drug trafficking, rural poverty and environmental degradation, particularly in regions where illegal economies have taken root due to a lack of viable opportunities. In this context, Africa and Peru offer contrasting yet similar scenarios in their challenges: rural areas vulnerable to illicit economies, rich in biodiversity and with a strong agricultural and culinary tradition.

This article examines the impact of inclusive and sustainable alternative development in Africa and Peru, with a focus on how these policies have contributed to curbing drug trafficking, reducing poverty and strengthening local gastronomic cultures. Through the analysis of concrete experiences—such as the substitution of illicit crops for cocoa in Ghana, coffee in Ethiopia and quinoa in Peru—parallels are established between both contexts in terms of social, economic and cultural transformation. The implementation of these models has had a direct impact on improving living conditions and has incentivized the valorization of traditional agro-food products, acting as catalysts for gastronomic renaissance. In this way, alternative development is configured not only as an effective strategy against the drug trafficking business model, but also as a platform for the affirmation of culinary identity and the promotion of sustainable economies based on local knowledge and resources.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), alternative development constitutes a long-term strategy aimed at promoting sustainable rural development in regions affected by illicit drug cultivation. Its main objective is not limited to substituting illegal crops but seeks to transform the socio-economic structures that sustain such activities.

In general terms, alternative development comprises a set of policies and programmes designed to offer licit and sustainable livelihoods as an alternative to illegal or environmentally harmful practices, such as the cultivation of coca, poppy or cannabis. This approach is comprehensive, as it incorporates economic, social, environmental and cultural dimensions, with the purpose of generating structural conditions that favor long-term sustainability.

When oriented in an inclusive and sustainable manner, alternative development transcends purely economic indicators and incorporates aspects such as gender equity, environmental protection and the revalorization of local cultures. The active participation of communities in the

design, implementation and evaluation of these programmes is fundamental to guaranteeing their effectiveness and legitimacy.

In its most inclusive conception, this strategy recognizes local communities not as passive recipients, but as key actors in transformation processes. The comprehensive and sustainable alternative development strategy has four key components: i) reconstruction of the social fabric that is reflected in the State's presence in territorial security, ii) comprehensive intervention that promotes diversification of livelihoods, job creation and the promotion of entrepreneurships, iii) sustainable licit economies that contribute to closing socio-economic gaps and reducing coca-growing areas and iv) sustainable markets based on the circular economy approach that promotes products and services friendly to the ecosystem.

Source: chocolopolis.com

In West Africa, alternative development has focused on strategic agricultural sectors such as cocoa, coffee and other high value-added crops. Countries such as Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia and Nigeria have implemented policies aimed at strengthening these sectors not only from a productive perspective, but also as axes of social, economic and cultural transformation.

Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, the world's main cocoa producers, have promoted sustainable transformation processes through policies designed to improve product quality, guarantee fair prices for farmers and encourage domestic consumption. In Ghana, for example, the Cocoa Life programme, implemented by Mondelēz International in alliance with governments and non-governmental organizations, has linked environmental sustainability, community empowerment and economic diversification (Mondelēz, 2020). This initiative has promoted responsible agricultural practices, nutritional education and training in gastronomic entrepreneurship, encouraging the transformation of cocoa into value-added products. The growing presence of artisanal chocolate shops in cities such as Accra and Kumasi is a tangible reflection of these efforts.

In Ethiopia, arabica coffee transcends its commercial value to become an identity element of profound cultural roots. Programmes promoted with the support of the Food and Agriculture Organization of

the United Nations (FAO) have contributed to improving production, promoting tourist routes linked to coffee and facilitating the integration of rural communities into more inclusive value chains. These actions have generated an increase in rural income, strengthened cultural identity and stimulated domestic consumption. An emblematic case is the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Ethiopia, proposed as World Heritage by UNESCO, which demonstrates how agricultural production can be articulated with territorial, cultural and gastronomic development.

Nigeria, for its part, has promoted alternative development initiatives centered on crops such as ginger and pepper, promoted by the African Development Bank. These projects have adopted an inclusive approach by promoting womenled cooperatives, which articulate sustainable agriculture, gender empowerment and local culinary entrepreneurships.

Collectively, these cases illustrate how alternative development can generate positive impacts when integrated with broader objectives of sustainability, equity and cultural valorization. The articulation between agriculture, identity and gastronomy allows not only to diversify rural economies, but also to strengthen the social fabric and promote more just and inclusive forms of development.

In Peru, alternative development has been historically linked to anti-drug trafficking strategies. Since the 1980s and 1990s, the country has implemented various crop substitution programmes in areas traditionally dedicated to coca leaf cultivation, such as the Alto Huallaga valley and the Valley of the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers (VRAEM), where this activity constituted the main economic livelihood for numerous rural communities.

Thanks to programmes promoted by the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), alternative crops such as coffee have managed to consolidate not only as competitive export products, but also as symbols of an emerging culinary culture. Initiatives such as the “Cup of Excellence” competition have incentivized the improvement of Peruvian coffee quality, positioning it in international markets and generating, at the same time, a renewed sense of pride and local identity among producers.

Cocoa follows a similar trajectory. Through the articulation between local governments, producer organizations and private companies, promoted by alternative development programmes, their incorporation into haute cuisine circuits has been facilitated, both nationally and internationally. These crops, previously associated with regions stigmatized by drug trafficking, have become drivers of economic, territorial and cultural transformation.