A note from the editor

Vanessa Byrne / Managing Director

At last 2021 is here! With a clear Covid endgame insight, this a scientific fact.

Now to get ourselves back on track, full of enthusiasm and positively tackle the many opportunities that 2020 has created. It has forced us to reappraise our values and way of life. It has given us an opportunity to adjust the way we do things and demonstrated what we can achieve when we set our minds to it.

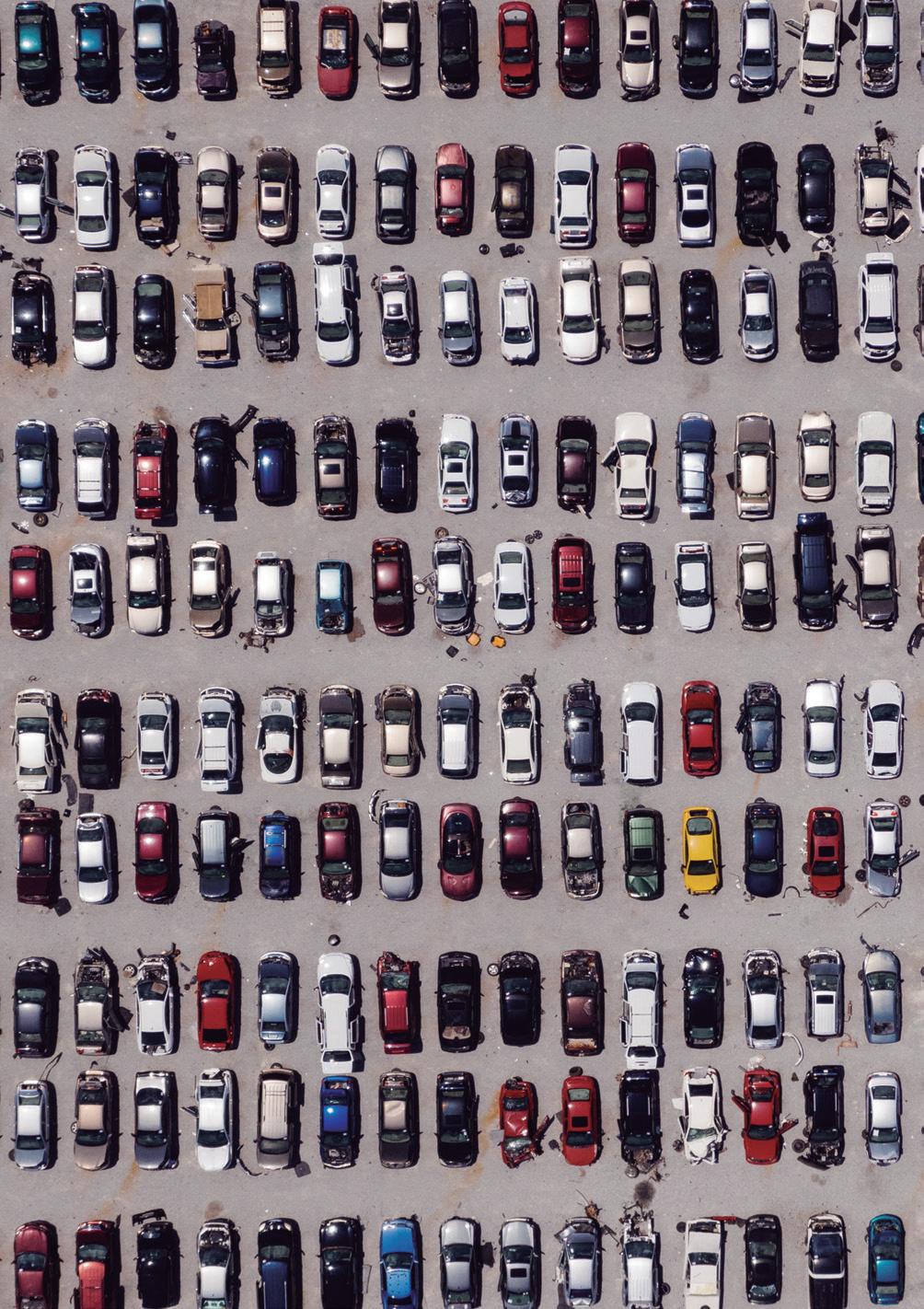

This can-do attitude that 2020 has highlighted is the same that we need to apply to changes we would like to see in the future. Our article on Cars and Roads focuses on one of our worst and most complex local issues; that of traffic management and

Por fin 2021 ya está aquí! Con una visión clara del fin de Covid, es un hecho científico.

Ahora hay que encarrilarnos llenos de entusiasmo, y abordar positivamente las variadas oportunidades que ha creado 2020. Nos ha obligado a revaluar los valores y nuestros modos de vida. Nos ha dado la oportunidad de ajustar la forma en que hacemos las cosas y demostró lo que podemos lograr juntos cuando nos lo proponemos.

Esta actitud positiva que ha resaltado 2020 es la misma que debemos aplicar a los cambios que nos gustaría ver en el futuro. Nuestro artículo sobre automóviles y carreteras se centra en uno de nuestros

pollution. This topic is a very sensitive one which has to be faced and cannot be ignored, this magazine will continue to apply focus on this and promote all sustainable modes of transportation.

Quality in products and services are an essential part of sustainability. As promised, in 2021 we will launch our very own OTWO Cave web shop. This should bring to you a wide choice of quality artisan products and services created around the area. Our article on “The Parque Natural de Andalucia trademark, a commitment to sustainability” explains the efforts and mechanisms which we are working with to achieve this goal. We are also working to ensure there are similar standards applicable in Gibraltar with a development of our CSR product.

Publications will be another important aspect of our services. In this edition we finish the series of Narrowing the Straits from the stunning Juanlu Gonzalez and on the February edition we will commence with his second volume. We have the pleasure of announcing we will exclusively publish on our online shop his digital book “Narrowing the Straits” which will include all chapters covered by Juanlu Gonzalez in all our past editions. We are working with other writers and will soon have a unique collection, all with the quality and care that we lavish on our productions.

Jessica Leaper’s excellent article “The Bigger Picture” also gives us an insight on the impact our life experiences has in shaping us all, our attitudes and customs. 60% of the mammals on Earth are livestock (predominantly cattle and pigs), 36% are humans, and just 4% of the living mammals on the planet are wild animals…. Does this feel right to you? We are the keys that will unlock solutions, if we are brave enough to face the issue. Never underestimate the power of the consumer.

2021will now also see the start of our exciting Green Week - more on this soon.

Keep safe and don’t despair.

Peace and love to all.

peores y más complejos problemas locales: el de la gestión del tráfico y la contaminación. Este tema es una cuestión muy delicada que hay que afrontar y que no se debe ignorar, esta revista seguirá enfocándose en esto y promoviendo todos los modos de transporte sostenibles.

La calidad en los productos y servicios es una parte esencial de sostenibilidad. Como hemos prometido, en 2021 lanzaremos nuestra propia tienda web OTWO Cave, ofreciéndote una amplia variedad de productos y servicios artesanales de calidad y creados en la zona. Nuestro artículo sobre «La Marca Parque Natural de Andalucía, una apuesta por la sostenibilidad» explica los esfuerzos y mecanismos con los que estamos trabajando para conseguir este objetivo.También estamos esforzándonos con el desarrollo de nuestro producto CSR para asegurar que existan estándares similares aplicables en Gibraltar.

Las publicaciones serán otro aspecto importante de nuestra oferta. En esta edición terminamos la serie «Narrowing the Straits» del deslumbrante Juanlu González y en la edición de febrero comenzaremos con su segundo volumen. Tenemos el placer de anunciar que publicaremos en exclusiva y en nuestra tienda online su libro digital “Narrowing the Straits” que incluirá todos los capítulos cubiertos por Juanlu González en todas nuestras ediciones pasadas. Estamos trabajando con otros autores y pronto tendremos una colección única, todo con la calidad y el cuidado que le damos a nuestras ediciones.

El excelente artículo de Jessica Leaper «The Bigger Picture» también nos da una idea del impacto que nuestras experiencias de vida tienen en moldear las actitudes y las costumbres.

El 60% de los mamíferos de la Tierra son ganado (predominantemente bovinos y porcinos), el 36% son humanos y solo el 4% de los mamíferos vivos del planeta son animales salvajes. ¿Le parece bien? Somos las llaves que abrirían soluciones si somos lo suficientemente valiente para enfrentarnos a este problema. Nunca subestimes el poder del consumidor.

2021 verá ahora el comienzo de nuestra emocionante Semana Verde (Green Week Gibraltar); pronto ofreceremos más información sobre este evento.

Mantente a salvo y no te desesperes. Paz y amor para todos.

10 11

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

ILLUSTRATION: JUANJO TRUJILLO

JANUARY / Enero

Collection “The flower of the month”

salvaje o Durillo Laurustinus

Viburnum tinus

Dr Keith Bensusan Director

Gibraltar Botanic Gardens, The Alameda.

The Laurustinus is a large shrub that is very common in horticulture and extremely well known in cultivation in Central and Northern Europe, including the UK. However, it is native to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic island of the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands, but it can withstand temperatures below freezing and this makes it tolerant of colder climates. The Lauristinus has very attractive white inflorescences – tightly bunched groups of pretty flowers. Its evergreen leaves are dark and glossy green, whilst its berries are a curious metallic blue. All of these features contribute to its horticultural appeal. The species does not grow wild in Gibraltar but is fairly common in the Cork Oak woodlands of nearby southern Iberia and North Africa, including the vast forest of ‘Los Alcornocales’ that lies on the Rock’s doorstep. The Lauristinus flowers early in the year and produces its bright and attractive berries during the Spring. It is a very important food source for Robins breeding in woodlands of southern Spain and the distribution of breeding pairs tends to match that of Laurustinus shrubs. In Gibraltar it has become an increasingly common garden plant. It can be seen in the Gibraltar Botanic Gardens and in Commonwealth Park, as well as other landscaped areas.

El Durillo o Laurentino, es un arbusto grande y común en la jardinería, muy recurrente en los cultivos del norte y centro de Europa, incluyendo el Reino Unido.

A pesar de que su origen es Mediterraneo - ubicándose en las Islas Azores, Madera y Canarias - soporta temperaturas bajo cero lo que le permite sobrevivir en climas bastante más fríos.

El Laurentino, produce eflorescencias blancas muy atractivas. Estas inflorescencias agrupan las flores sobre la rama o el tallo, de forma seductora. Sus hojas perennes son de un verde oscuro y brillante,mientras sus frutos son de un curioso azul metalizado. características que contribuyen a su encanto ornamental para la jardinería.

La especie, no crece silvestre en Gibraltar, pero es bastante común en los alcornocales del sur ibérico y norte de Africa, incluyendo por supuesto el Parque Natural de Los Alcornocales, muy cercano a Gibraltar.

Este Durillo o Laurel salvaje, florece a principios de año y produce bayas brillantes y atrayentes, durante la primavera. Estas, son una fuente de alimento muy importante para los petirrojos que se reproducen en los bosques del sur de España y l reparto de las parejas reproductoras, tiende a coincidir con la de los arbustos de Laurentino. En Gibraltar, se ha convertido en una planta de jardín cada vez más común. Pueden disfrutarse en sus Jardines Botánicos y en el Commonwealth Park, al igual que en diversas zonas ajardinadas.

tinus 12

Viburnum

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

Laurel

The Royal Gibraltar Post Office has become the first public Postal Service in the world to have a fully electric delivery fleet.

The Government made the announcement in early December and added that the new electric postal fleet was in line with manifesto commitments for a Green Gibraltar.

A total of thirteen zero-emission vehicles have been leased and will replace the seventeen-year-old fuel vehicles that were not EURO 6 standard.

The Government announcement went on to say, “The all-electric postal vans are being rolled out as from this week and will deliver mail across all areas of Gibraltar. The electric vehicles will allow the Postal Service to deliver letters and parcels safely and efficiently in the most environmentally friendly way possible and help preserve the beauty of Gibraltar, both in terms of carbon emission and noise.”

“Although the top motivation to go electric is the environment, the second biggest driver is the lower total cost of ownership when you factor in both direct and indirect costs and the savings over the life of the vehicle. The electricity charge is around one fifth as much per kilometre as buying petrol.”

The post office fleet announcement followed the news that electric buses were trialled in Gibraltar in late November. If the trial is successful it is hoped that Gibraltar’s buses can be swapped for ZERO-emissions vehicles over the next few years.

La flota de la oficina de correos gibraltareña se vuelve ecológica

La Royal Gibraltar Post Office, ha conseguido ser el primer servicio postal en el mundo que ha cambiado toda su flota por vehículos de reparto que utilizarán únicamente el suministro eléctrico para realizar su trabajo.

El Gobierno así lo anunció a principios de diciembre, añadiendo que la nueva flota postal eléctrica es coherente con los compromisos del manifiesto por un Gibraltar Verde.

Trece han sido los vehículos de emisión cero alquilados que van a sustituir a los de combustible que durante diecisiete años no fueron acordes al modelo EURO 6.

El anuncio del gobierno añadía: “La totalidad de las camionetas eléctricas para el servicio postal, se irán implementando a partir de esta semana y entregarán el correo en todas las zonas de Gibraltar. Los vehículos eléctricos permitirán al Servicio Postal entregar cartas y paquetes

de forma segura y eficiente con la fórmula más ecológica posible ayudando a preservar la belleza de Gibraltar, reduciendo tanto las emisiones de carbono como de ruido”.

“Aunque el principal motivo para esta decisión es el medioambiental, el segundo factor decisivo, es el descenso del coste total del servicio teniendo en cuenta los costes directos e indirectos y el ahorro final durante toda la vida útil del vehículo. El precio del suministro eléctrico ronda la bajada de una quinta parte del precio por kilómetro comparándolo con el coste de la gasolina”.

Al anuncio del cambio de los vehículos de la oficina de correos, se añadió la noticia de que en Gibraltar también se probaron a final de noviembre, los autobuses eléctricos. Si la prueba tiene éxito, se espera que los autobuses de Gibraltar puedan cambiarse por vehículos de cero emisiones en los años próximos.

COCA-COLA, PEPSICO AND NESTLÉ NAMED WORLD’S WORST PLASTIC POLLUTERS OF 2020

For the third year in a row, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestlé have been named the world’s worst plastic polluters and have been accused of making no progress in reducing plastic waste.

The Break Free from Plastic annual audit surveyed 55 nations and ranked Coca-Cola as the No1 plastic polluter in the world. The brands drink bottles were the most frequently found littering beaches, parks and rivers. Its reach is so widespread that Coca-Cola branded litter is worse than PepsiCo and Nestlé combined.

15,000 volunteers from around the world took

part in the annual audit to identify which plastic products from global brands are the most found in the highest number of countries. This year, they collected 346,494 pieces of plastic waste, with Coca-Cola branding found on 13,834 pieces, PepsiCo branding on 5,155 and Nestlé on 8,633.

In March 2020, another study by NGO Tearfund found that Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé and Unilever were responsible for half a million tonnes of dumped or burnt plastic pollution each year in just six developing countries: China, India, the Philippines, Brazil, Mexico and Nigeria. Campaigners also criticized Coca-Cola when the drinks giant announced that it would not abandon plastic bottles.

The global audit also found that the most commonly found type of plastic item is single-use sachets. The second is cigarette butts and the third plastic bottles.

Coca-Cola has disputed the claim that it is making no progress to tackle waste, stating that “Globally, we have a commitment to get every bottle back by 2030, so that none of it ends up as litter or in the oceans, and the plastic can be recycled into new bottles."

PepsiCo also stated that it has set plastic reduction goals and that they are tackling packaging through “partnership, innovation and investments."

A statement from Nestlé said it was making progress but acknowledged more was needed and aim to make 100% of packaging recyclable or reusable by 2025.

14 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 15

GIBRALTAR

POST OFFICE FLEET GOES GREEN

A 2017 study published in Science Advances, revealed that up to 91% of all plastic waste ever generated has not been recycled, ending up incinerated, in landfill or the environment.

Coca-Cola, PepsiCo y Nestlé nombrados como los mayores contaminadores de plásticos del mundo en 2020

Por tercer año consecutivo, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo y Nestlé han sido nombrados los peores contaminadores plásticos del mundo y han sido acusados de “progreso cero” en la reducción de residuos plásticos.

La auditoría anual Break Free From Plastic encuestó a 55 países y clasificó a Coca-Cola como el mayor contaminante de plástico a nivel mundial. Las botellas de esta marca de bebidas, fueron las que se encontraron con mayor frecuencia en playas, parques y ríos. Su volumen es tan extenso que supera a la basura plástica de PepsiCo y Nestlé juntas.

15.000 voluntarios de todo el mundo participaron en la auditoría anual identificando qué productos y de qué marcas comerciales son los que más se identifican en el mayor número de países. Este año, recogieron 346,494 piezas de plástico, de las cuales 13,834 piezas pertenecían a Coca Cola, 5,155 a Pepsi y 8,633 a Nestlé.

En marzo de 2020, otro estudio de la ONG Tearfund descubrió que Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé y Unilever eran responsables de medio millón de toneladas de contaminación plástica vertida cada año en tan solo seis países en desarrollo: China, India, Filipinas, Brasil, México y Nigeria. Los activistas, también criticaron a Coca-Cola cuando el gigante de las bebidas anunció que no abandonaría las botellas de plástico.

Esta auditoría global, también detectó que el artículo de plástico más usado y desechado comúnmente, son las bolsas de un solo uso. El segundo, son las colillas de cigarrillos y el tercero, las botellas de plástico.

Coca-Cola ha cuestionado la afirmación de que no está haciendo ningún progreso para abordar el desperdicio, afirmando que “a nivel mundial, tenemos el compromiso de recuperar todas las botellas para 2030, de modo que ninguna termine como basura o en los mares, reciclando el plástico para nuevos envases".

PepsiCo también declaró que ha establecido obje-

tivos de reducción de plástico y que están abordando el canal de embalaje a través de "asociaciones, innovación e inversiones".

En sus declaraciones, Nestlé dijo que estaba progresando, reconociendo que se necesita más y que el objetivo es conseguir que el 100% de los envases sean reciclables o reutilizables para 2025.

Un estudio de 2017 publicado en Science Advances, reveló que hasta el 91% de todos los desechos plásticos jamás generados no se han reciclado y terminan incinerados, en vertederos o en el medio ambiente.

GIBRALTAR’S AIR QUALITY AT BEST LEVELS SINCE RECORDS BEGAN

The Gibraltar Government has released 2019 air quality figures which reveal that even before the COVID-19 crisis, air quality is still showing signs of improvement and was at its best levels since records began.

The data also shows that 2019 was the second year in a row in which Gibraltar met EU air quality requirements. The improvements include levels of the harmful gas, nitrogen dioxide, which only reached EU required levels in 2018 for the first time since 2007.

Concentrations of particulate matter (PM), both PM10 and the smaller and more dangerous PM2.5, continued to fall. The latter is now approaching the WHO levels that are stricter than those of the EU. Benzene levels were also down.

The Governments statement went on to say "the Government considers that the issue of pollution as a result of the temporary generators in the South District is now almost totally resolved and will shortly be moving the monitoring station to the North District. The Rosia Road station will remain in place. Both these stations will now largely be picking up emissions from traffic which is now considered to be the top challenge in tackling air quality of Gibraltar."

Minister for Environment John Cortes commented, “In 2011 we set out to tackle the different strands affecting our air quality. We were up against high levels of pollution and fanning the possibility of high-level fines from the EU. We have successfully dealt with all of that and attained recorded levels

16

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

Photography: Tomáš Malík

that we must be very pleased with. Air pollution from power generation has now been dealt with almost entirely. I am of course, still not happy with our air quality. Traffic and, on occasions, shipping, are now the main contributors, and we must all work together to tackle these

El aire de Gibraltar en los mejores niveles desde que comenzaron los registros

El Gobierno de Gibraltar ha publicado cifras de calidad del aire de 2019 que ponen de manifiesto que incluso antes de la crisis del COVID-19, la calidad del aire mostraba signos de mejora y actualmente, se encuentra en sus mejores niveles, desde que comenzaron los registros.

Los datos también demuestran que 2019 fue el segundo año consecutivo cumpliendo con los requisitos de calidad del aire que exige la UE. Las mejoras incluyen niveles de dióxido de nitrógeno, gas dañino, que solo alcanzó los niveles requeridos por la UE en 2018, desde 2007.

Las concentraciones de las partículas más dañinas y minúsculas, (PM) tanto PM10 como PM2.5, continuaron cayendo. Este último baremo, se está acercando ahora a los niveles de la OMS, más estrictos que los de la UE. Los niveles de benceno también bajaron.

El comunicado del Gobierno continuó diciendo, "el ejecutivo considera que el problema de la contaminación como resultado de los generadores temporales en el Distrito Sur, está casi resuelto actualmente y en breve trasladará la estación de monitoreo al Distrito Norte. La estación Rosia Road permanecerá en su lugar. Ambas estaciones, serán las que recojan en gran medida las emisiones del tráfico, que ahora se considera el principal desafío para abordar la calidad del aire de Gibraltar".

El ministro de Medio Ambiente, John Cortes, comentó: “En 2011 nos propusimos abordar los diferentes aspectos que afectan la calidad del aire. Nos enfrentamos a altos niveles de contaminación y albergando la posibilidad de recibir elevadas multas por parte de la UE. Podemos indicar que hemos abordado con éxito toda esta cuestión y alcanzando niveles con los que debemos estar muy satisfechos. La contaminación del aire provocada por la generación de energía se ha abordado casi en su totalidad. Por

supuesto, aún no estoy plenamente satisfecho con la calidad del aire. Actualmente, el tráfico y, en ocasiones, el transporte marítimo, son los principales causantes, y debemos trabajar juntos para abordarlos y mejorar aún más en ello".

Las cifras preliminares para 2020 muestran que la calidad del aire continúa mejorando.

DENMARK ENDS ALL NEW OIL AND GAS DRILLING IN THE NORTH SEA

In a landmark decision, the Danish government voted to cancel all new North Sea oil and gas exploration as part of the country’s plan to phase out fossil fuel extraction by 2050.

Denmark's existing platforms will continue extracting fossil fuels, but all new future licensing will not go ahead. This momentous move will ultimately end the country's oil and gas production. Over the last decade, the country has focused on clean energy, including offshore wind farms built by Denmark’s former state oil company

Since it began oil and gas exploration in 1972, Denmark’s North Sea revenues have helped it become one of the richest nations in Europe. The Danish government estimates that the decision to phase out fossil fuel production means that the country will lose £1.6bn in revenue.

In 2017, France became the first country in the world to phase out exploration and production by 2040. New Zealand followed in 2018 by cancelling all new fossil fuel extraction permits.

But as Europe’s biggest oil producer, Denmark’s decision will have a global impact, and hopefully, apply pressure on other nations to make similar moves to bring an end to the fossil fuel era.

Dinamarca pone fin a todas las nuevas perforaciones de petróleo y gas en el Mar del Norte

En una decisión histórica, el gobierno danés votó para cancelar todas las nuevas exploraciones de petróleo y gas en el Mar del Norte, como parte del plan para eliminar gradualmente la extracción de combustibles fósiles en todo el país, para 2050.

Las plataformas existentes en Dinamarca, continuarán extrayendo combustibles fósiles pero,

se paralizarán todas las licencias a futuro. Esta trascendental decisión terminará con la producción de petróleo y gas del país. Durante la última década, Dinamarca se ha centrado en las energías alternativas, incluidos los parques eólicos marinos construidos por la antigua compañía petrolera estatal de Dinamarca.

Desde que comenzó la exploración de petróleo y gas en 1972, los ingresos del Mar del Norte de Dinamarca la han ayudado a convertirse en una de las naciones más ricas de Europa. El gobierno danés estima que la decisión de eliminar gradualmente la producción de combusti -

bles fósiles significa que el país perderá 13 mil millones (£ 1,6 mil millones) en ingresos.

En 2017, Francia se convirtió en el primer país del mundo en eliminar gradualmente la exploración y producción para 2040. Nueva Zelanda siguió en 2018 cancelando todos los nuevos permisos de extracción de combustibles fósiles. Pero como el mayor productor de petróleo de Europa, la decisión de Dinamarca tendrá un impacto global y, con suerte, ejercerá presión sobre otras naciones para que tomen medidas similares para poner fin a la era de los combustibles fósiles.

19 18

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

“Gibraltar’s rich heritage is one of its greatest assets and it is imperative that it is preserved and managed in a sustainable way to continue to benefit future generations”

The bigger picture

El

panorama completo

Author: Jessica Leaper - AWCP

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 25 24 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

Brazil, January 2019. The drive from Rio de Janeiro to the university town of Viçosa was hair-raising on so many levels, not least for the creeping realisation of the full impact of our global obsession with meat.

Like many, I had been a vegetarian back in my University days, even touching on vegan for short stints. I settled into a ‘flexible diet’ when I first came to Gibraltar to live (my penchant for Iberian ham was more than I could overcome full-time). I also found it difficult to find the foods I had become accustomed to in the UK. At the time I was busy raising a family but also ‘raising a zoo’. The Wildlife Park in Gibraltar became an obsession like no other. For no fathomable reason I felt insanely driven to ‘make it work’, maybe because it was the job I was paid to do, but I also had a strong sense of responsibility for improving the lives animals in my care.

I have always thought about the bigger picture. I guess that’s the part of me that promts me take the lead. I started off my post-school career as a foundation arts ‘painter’ at St Martin’s College of Art. It didn’t suit me. It never was my vocation or calling, but my painting process revealed my approach to most things in life. Sketching out the bigger picture whilst manically trying to fill in the details so the picture looks complete rather than an embarrassing mess. I see in detail, but a painting is nothing without the bigger picture.

So what is the bigger picture with conservation? I don’t think I fully felt sure of that until I travelled to Brazil. I was there to take part in a conservation planning workshop. The aim of the Mountain Marmoset Conservation Project (MMCP) is to save two critically endangered marmosets from extinction. It was early days for the project and the workshop was designed to kick-start the planning process. Admirable work by some really impressive conservationists and professional zoologists from around the world. It was my first real exposure to species conservation planning and it was a real eye-opener.

I first started to feel uneasy on the drive from Rio, but the alien roads and outrageous road ‘etiquette’ of the Brazilian drivers preoccupied me. The next sinking feeling was whilst being driven by Sally, the projects lifeline/coordinator/facilitator, to Ipanema, a small village where we hoped to locate the ‘elusive blonde’ the stunning buffy-headed marmoset on the brink of extinction.

Brasil, enero de 2019. El viaje desde Río de Janeiro a la ciudad universitaria de Viçosa fue espantoso a muchos niveles, sobre todo por la progresiva comprensión del impacto completo de nuestra obsesión global por la carne.

Como muchos, yo había sido vegetariana en mi época universitaria, incluso tocando lo vegano durante cortos periodos. Me acomodé en una "dieta flexible" cuando llegué a Gibraltar a vivir (mi inclinación por el jamón ibérico era más de lo que podía superar).

También me resultó difícil encontrar los alimentos a los que me había acostumbrado en el Reino Unido. En ese momento estaba ocupada criando una familia pero también "criando un zoológico". El Parque de la Vida Silvestre de Gibraltar se convirtió en una obsesión como ninguna otra. Por alguna razón incomprensible, me sentí impulsada a "hacer que funcionara", tal vez porque era el trabajo por el que me pagaban, pero también tenía un fuerte sentido de la responsabilidad para mejorar la vida de los animales a mi cargo.

Siempre he pensado en el panorama completo. Supongo que esa es la parte de mí que me impulsa a tomar la delantera. Empecé mi carrera post escolar como pintora en el St. Martin's College of Art. No me encajaba. Nunca fue mi pasión o mi vocación, pero mi trabajo como pintora me reveló mi enfoque sobre la mayoría de las cosas de la vida. Dibujando el cuadro completo mientras trataba maniáticamente de rellenar los detalles para que el cuadro se viera entero en lugar de un vergonzoso desastre. Veo los detalles, pero un cuadro no es nada sin el panorama completo.

Entonces, ¿cuál es el panorama completo de la conservación? No creo que estuviera completamente segura de eso hasta que viajé a Brasil. Fui allí para participar en un taller de planificación de la conservación. El objetivo del Proyecto de Conservación del Tití de Montaña (MMCP, del inglés Mountain Marmoset Conservation Project) es salvar de la extinción a dos titíes en peligro crítico. Era el comienzo del proyecto y el taller estaba diseñado para iniciar el proceso de planificación. Un trabajo admirable de algunos conservacionistas y zoólogos profesionales realmente impresionantes de todo el mundo. Fue mi primera exposición real a la planificación de la conservación de especies y me abrió los ojos.

Empecé a sentirme incómoda al conducir desde Río, pero las carreteras extrañas y la escandalosa "etique-

26 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

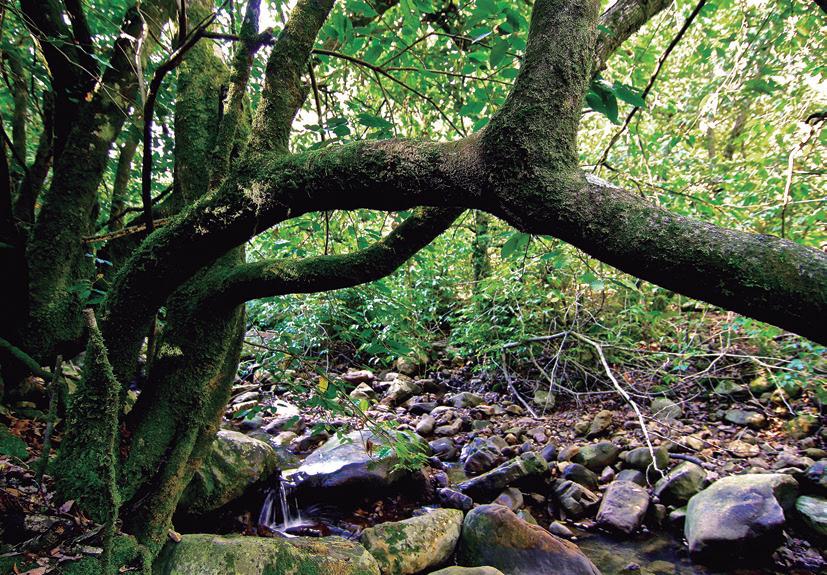

As we drove though villages and out onto the open road, the surrounding countryside reminded me, in parts, of the summertime in Kent, where I grew up. As much as I love the British countryside, I craved to see and feel the wild, exotic, steamy forests of the Amazon. I was, after all, in Brazil. There was something not quite right about the scenery, something deeply disturbing about the neatly fenced green fields, bordered by the odd patch of trees in the distance. As I looked closer, these clumps of trees were actually insanely tall trees, they looked so odd, like a wall of abandoned Giacometti sculptures, standing alone, exposed and forlorn. As the clumps grew closer to the road I could see the twisted lianas, a jungle of vines. It was ‘a jungle’. A rainforest, but not. A rainforest cut short, deleted and cut off.

The striking, lush green fields were filled with cattle, as far as the eye could see, rather cute cattle with endearingly large floppy ears, an adaptation that helps them cope with the heat of the day. It dawned on me at that moment, that this patchwork of fields was the graveyard of pristine Atlantic rainforest. It also soon dawned on me that the comforting patchwork of fields and hedgerows, I grew up thinking of as ‘British wildlife,’ was actually the very same scene of destruction and devastation that I was witnessing here.

On the next refuel, I asked Rodrigo, our characterful primatologist/geneticist/host about his thoughts on the cattle ranching and the impact it was having on the forests and the habitats of the species he was studying. “But what can we do?” he shrugged, whilst tucking into his Brazilian meat buffet lunch. “The cattle ranchers own half the land in Brazil, they have so much power”.

This seemed to be the theme throughout most of the trip. Conservationists tucking into Brazilian barbeque food, whilst discussing tactics for saving small marmosets in tiny patches of rainforest. As much as I respect and completely value the work these conservationists do, I couldn’t help but feel there was a better way.

We had already been running our Cut Meat Not Trees and Conscious Eating Gibraltar campaigns at the AWCP for a few years and it had been hardgoing. It’s never easy to change people’s perceptions on something as personal as food. One of the aims

ta" de los conductores brasileños me preocupaban. La siguiente sensación de hundimiento fue cuando Sally, la coordinadora y promotora del proyecto, me llevó a Ipanema, un pequeño pueblo donde esperábamos encontrar a la "rubia escurridiza", el impresionante tití cabeza de chorlito al borde de la extinción.

Mientras conducíamos por los pueblos y salíamos a la carretera, el campo circundante me recordaba, en parte, al verano en Kent, donde crecí. Por mucho que me guste la campiña británica, ansiaba ver y sentir los salvajes, exóticos y húmedos bosques del Amazonas. Después de todo, estaba en Brasil. Había algo que no estaba del todo bien en el paisaje, algo profundamente perturbador en los verdes campos cercados, bordeados por un extraño parche de árboles en la distancia. Al mirar más de cerca, estos grupos de árboles eran en realidad árboles increíblemente altos, tenían un aspecto muy extraño, como un muro de esculturas Giacometti abandonadas, en pie, expuestas y desoladas. A medida que los grupos se acercaban a la carretera podía ver las lianas retorcidas, una jungla de vides. Era "una jungla". Una selva, pero no. Una selva tropical acortada, borrada y cortada.

Los llamativos y exuberantes campos verdes estaban llenos de ganado, por lo que el ojo podía ver, un ganado bastante lindo con grandes y simpáticas orejas caídas, una adaptación que les ayuda a hacer frente al calor del día. En ese momento me di cuenta de que este mosaico de campos era el cementerio de la prístina selva tropical del Atlántico. También pronto me di cuenta de que el reconfortante mosaico de campos y setos, del que crecí pensando que era la "vida salvaje británica", era en realidad la misma escena de destrucción y devastación que estaba presenciando aquí.

En la siguiente gasolinera, le pregunté a Rodrigo, nuestro primatólogo/genetista/anfitrión sobre sus ideas sobre la ganadería y el impacto que estaba teniendo en los bosques y los hábitats de las especies que estaba estudiando. "¿Pero qué podemos hacer?" se encogió de hombros, mientras se comía su almuerzo de carne brasileña. "Los ganaderos son dueños de la mitad de la tierra en Brasil, tienen mucho poder". Este parecía ser el asunto durante la mayor parte del viaje. Ecologistas comiendo barbacoa brasileña, mientras discutían tácticas para salvar pequeños titíes en pequeños trozos de selva. Por mucho que respete y

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 29 28 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

was to show meat eaters how they can easily substitute meat in their diets. Calentita was an ideal place to start. How difficult could it be for a group of zoo keepers, who spent their days catering for so many difficult species? Actually it was a riot, and the foods we served were a hit, with most. Okay, so Beyond Meat burgers are not Angus steak, but as a substitute once a week, surely everyone can manage that? After Calentita Beyond Meat products popped up in supermarkets and restaurants throughout Gibraltar and have become a staple alternative for many.

Since 2015, there has definitely been a change and a move towards healthier and plant-based diets in Gibraltar. I don’t feel it has the same stigma it had before, it is definitely more of a trend. Perhaps that’s just natural inertia, but I like to think our campaign has found its way into peoples consciousness and conscience, one way or another.

I even presented to the British Zoo Directors at the British Zoo Association AGM, urging them to highlight the consequences of what we eat, particularly meat and dairy farming on species habitats to their zoo visitors and suggested we lead by example at events, restaurants and cafeterias. I hoped we could create a zoo-wide campaign to try to change attitudes and lead the way. But it seemed to fall on deaf ears. Five years on and the sustainability actions for British zoos still neglect to mention the impact of meat and dairy on species habitats. Perhaps Sir David Attenborough will have a better chance of spurring change.

One of the delegates who did champion the cause and had been vocal for many more years on the subject, was Dom Wormell, Head of Mammals at Jersey Zoo and an integral member of the Mountain Marmoset Conservation Project (MMCP). Dom is mostly a staunch vegetarian/vegan, except when faced with yet another omelette with hidden ham and cheese, which it seems is the staple way with eggs in Brazil. During the workshop in Brazil, we had many an evening chat about ‘the bigger picture’. Dom has worked on many important primate species conservation projects all over South America For many. He has seen firsthand, the destruction our meat habits are having throughout most of South America’s precious habitats. Not just cattle ranching, but also soy production for European farm animal feed.

valore el trabajo de estos conservacionistas, no pude evitar sentir que había un modo mejor de hacerlo. Ya habíamos estado llevando a cabo nuestras campañas "Cut Meat Not Trees" (Corta el Consumo de Carne, No Cortes Árboles) y "Conscious Eating Gibraltar" (Comiendo Conscientemente en Gibraltar) en el AWCP durante unos años y había sido muy duro. Nunca es fácil cambiar la percepción de la gente sobre algo tan personal como la comida. Uno de los objetivos era mostrar a los consumidores de carne cómo pueden sustituir fácilmente la carne en sus dietas. Calentita era un lugar ideal para empezar. ¿Cómo de difícil puede ser para un grupo de cuidadores de zoológico, que pasan sus días atendiendo a muchas especies difíciles? En realidad, fue un alboroto, y los alimentos que servimos fueron un éxito, con la mayoría. De acuerdo, las hamburguesas Beyond Meat no son un bistec Angus, pero como sustituto una vez a la semana, seguramente todos pueden hacerlo. Después de Calentita, los productos Beyond Meat aparecieron en supermercados y restaurantes en todo Gibraltar y se han convertido en una alternativa básica para muchos.

Desde 2015, definitivamente ha ocurrido un cambio y un movimiento hacia dietas más sanas y basadas en plantas en Gibraltar. No creo que tenga el mismo estigma que antes, es definitivamente más una tendencia. Tal vez sólo sea inercia natural, pero me gusta pensar que nuestra campaña ha encontrado su camino en la conciencia de la gente, de una manera u otra. Incluso me presenté a los directores de los zoológicos británicos en la AGM de la Asociación Británica de Zoológicos, instándoles a resaltar las consecuencias de lo que comemos, en particular la cría de carne y productos lácteos en los hábitats de las especies a sus visitantes de los zoológicos, y les sugerí que diéramos ejemplo en los eventos, restaurantes y cafeterías. Esperaba que pudiéramos crear una campaña en todo el zoológico para tratar de cambiar las actitudes y mostrar el camino. Pero pareció caer en saco roto. Cinco años después, las acciones de sostenibilidad de los zoológicos británicos siguen sin mencionar el impacto de la carne y los lácteos en los hábitats de las especies. Tal vez Sir David Attenborough tenga una mejor oportunidad de provocar el cambio. Uno de los delegados que sí defendió la causa y se hizo oír durante muchos años más con respecto al

30 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

One of the workshop field trips took us to a small village just outside of Viçosa, where student Brazilian primatologist, Orlando Vital had been studying a small group of pure Buffy-tufted-ear marmosets. A coach load of delegates, we arrived together and waited expectantly under a large tree on a dirt patch behind the Barber's Shop owned by friends of Orlando. The patch of forest was no bigger than an ice rink. Orlando set up the playbacks, recordings of wild marmosets used to entice these inquisitive creatures forwards. After a short while, they began to contact call, moving closer to the expectant group, who stood silently, cameras poised. High pitched screams, almost inaudible, like bird calls but not melodic. They had been there all the time. Another stomach-wrenching moment of realisation. These animals were trapped, there was absolutely nowhere for them to go. So close to the human habitation, they had already become habituated to the locals and regularly came down for scraps of food. The forest patch was probably unable to support the group for much longer. This tiny patch of rainforest, smaller than many backyards, was a death sentence for these charismatic little creatures. These were patches of impotent and disconnected forest, barely supporting distressed and cut off species with little to no hope.

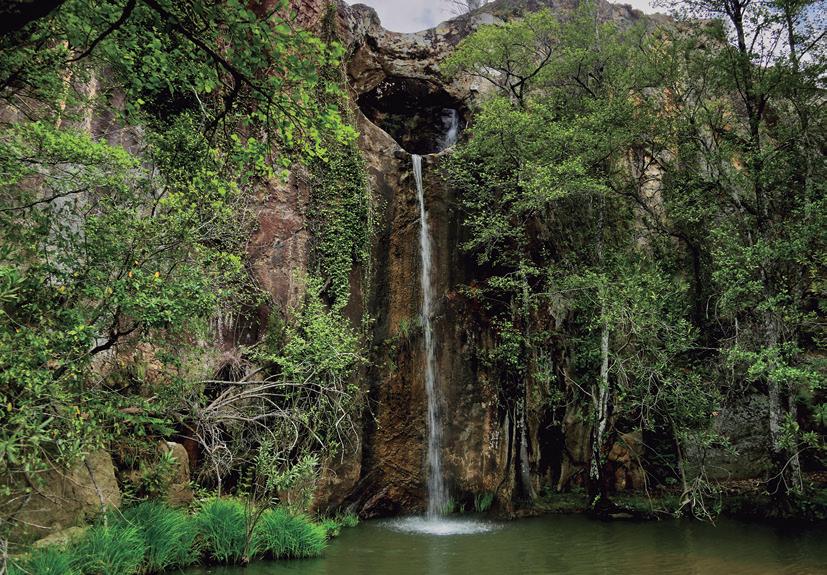

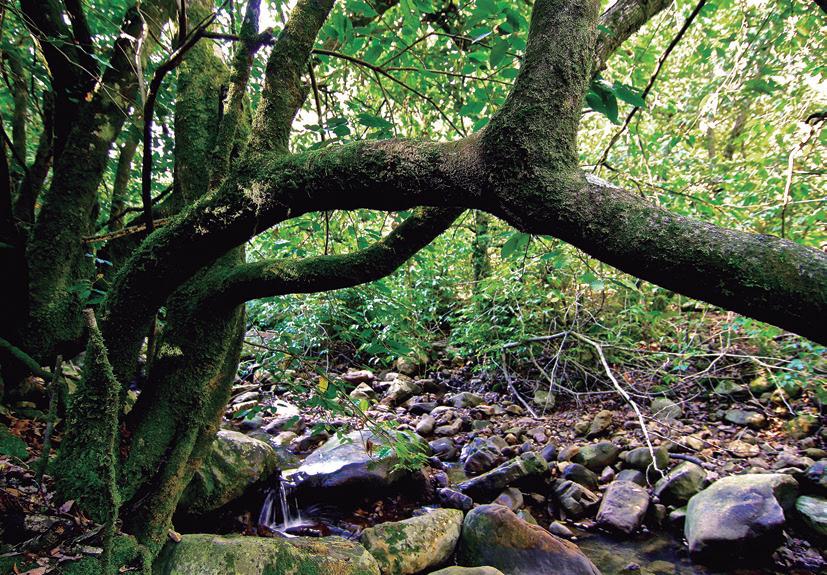

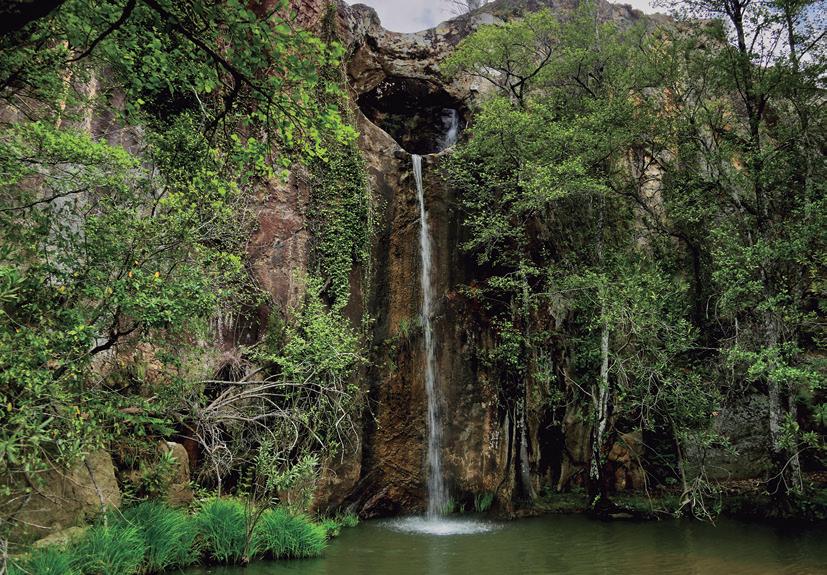

We ended the trip at the home and rewilding project of one of Brazil’s richest men. Comuna do Ibitipoca in Lima Duarte is a stunning 5000 hectare site with its own sustainable community, helipad (a slight deviation from the plan), forests, waterfalls and species reintroduction projects well underway. Our penultimate, blissful evening was spent at sunset at the highest point of the land, with the spectacular but disturbingly poignant statues that seem to reach out and pray to the Gods. Deep down, each of knew what they were praying for.

Single species conservation has its place and has undoubtedly saved many species, but I realised then and there that something bigger needs to happen and soon. Just like in my A level art exam days, when I would hide my painting until I could fill in all the details. Sometimes I would not manage to fully finish in time, but at least I had a painting with all its parts there and ready, a joined up image that can become a whole even if it’s not quite perfect. I guess in

tema, fue Dom Wormell, Jefe de Mamíferos del Zoológico de Jersey y miembro integrante del Proyecto de Conservación del Tití de Montaña (MMCP). Dom es principalmente un vegetariano/vegano incondicional, excepto cuando se enfrenta a otra tortilla de huevos con jamón y queso ocultos, que parece ser la forma básica de los huevos en Brasil. Durante el taller en Brasil, tuvimos muchas charlas nocturnas sobre "el panorama completo". Dom ha trabajado en muchos proyectos importantes de conservación de especies de primates en toda Sudamérica durante años. Ha visto de primera mano la destrucción causada por nuestros hábitos cárnicos en la mayoría de los preciosos hábitats de Sudamérica. No sólo la ganadería, sino también la producción de soja para la alimentación de los animales de granja europeos.

Uno de los viajes de campo del taller nos llevó a un pequeño pueblo a las afueras de Viçosa, donde un estudiante de primatología brasileño, Orlando Vital, había estado estudiando un pequeño grupo de titíes de orejas blancas puros. Un autobús lleno de delegados, llegamos juntos y esperamos expectantes bajo un gran árbol en un parche de tierra detrás de la panadería de los amigos de Orlando. El bosque no era más grande que una pista de hielo. Orlando preparó los playbacks y las grabaciones de titíes salvajes usadas para atraer a estas curiosas criaturas hacia allá. Después de un corto tiempo, comenzaron a comunicarse, acercándose al grupo expectante, que permanecía en silencio, con las cámaras preparadas. Gritos agudos, casi inaudibles, como los de los pájaros, pero no melódicos. Habían estado allí todo el tiempo. Otro momento de realización que me destrozó las tripas. Estos animales estaban atrapados, no había absolutamente ningún lugar para ellos. Tan cerca de la presencia humana, que ya se habían habituado a la población local y bajaban habitualmente a por restos de comida. La mancha forestal probablemente no pudo mantener al grupo por mucho más tiempo. Este pequeño trozo de bosque, más pequeño que muchos patios, era una sentencia de muerte para estas carismáticas criaturas. Eran parches de bosque impotentes y desconectados, que apenas soportaban especies en peligro y aisladas con poca o ninguna esperanza. Terminamos el viaje en el hogar y con el proyecto de reforestación de uno de los hombres más ricos de Brasil. La Comuna do Ibitipoca en Lima Duarte es un

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 33 32 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

conservation, that’s rewilding or habitat restoration. Creating the whole picture, not just a finished part of the whole. An ecosystem, like a painting, works together, as a bigger picture. The more pieces there are across the whole, the more complete it becomes. Like a complex jigsaw puzzle.

My journey over the years at the wildlife park; the animals, the people and the process have taught me many things, but mostly it has, in a convoluted and somewhat messy way, revealed to me the bigger picture, the final piece that I want to help to paint. A picture where every single colourful detail is included.

As we commence the UN’s ‘Decade on Ecosystem Restoration’, a “call for the protection and revival of ecosystems all around the world” these are just some of the reasons why I think it’s worth each of us trying Veganuary this year, planting a tree and supporting the restoration of our planet.

impresionante sitio de 5.000 acres con su propia comunidad sostenible, helipuerto (una ligera desviación del plan), bosques, cascadas y proyectos de reintroducción de especies en marcha. Nuestra penúltima y feliz tarde la pasamos al atardecer en el punto más alto de la tierra, con las espectaculares pero inquietantes estatuas que parecen alcanzar y rezar a los Dioses. En el fondo, cada uno de ellos sabía por lo que estaba rezando.

La conservación de especies individuales tiene cabida y sin duda ha salvado a muchas especies, pero me di cuenta en ese momento de que algo más grande tiene que suceder y pronto. Como en mis días de examen de arte de nivel A, cuando escondía mi pintura hasta que pudiera rellenar todos los detalles. A veces no lograba terminar a tiempo, pero al menos tenía un cuadro con todas sus partes y preparado, una imagen unida que puede convertirse en un todo aunque no sea del todo perfecto. Supongo que en la conservación, eso sería volver a silvestrar o la restauración del hábitat. Creando la imagen completa, no sólo una parte terminada del todo. Un ecosistema, como una pintura, trabaja en conjunto, como una imagen más grande. Cuantas más piezas haya en el conjunto, más completo será. Como un complejo rompecabezas. Mi viaje a lo largo de los años a lo largo de los parques de vida silvestre, los animales, la gente y el proceso me han enseñado muchas cosas, pero sobre todo me ha revelado, de una manera enrevesada y algo desordenada, el panorama completo, la pieza final que quiero ayudar a pintar. Un cuadro en el que se incluyen todos y cada uno de los detalles coloridos.

Al comenzar la "Década de la Restauración de los Ecosistemas" de la ONU, un "llamado a la protección y revitalización de los ecosistemas de todo el mundo", estas son algunas de las razones por las que creo que vale la pena que cada uno de nosotros intentemos el Veganuary de este año, plantando un árbol y apoyando la recuperación de nuestro planeta.

34 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

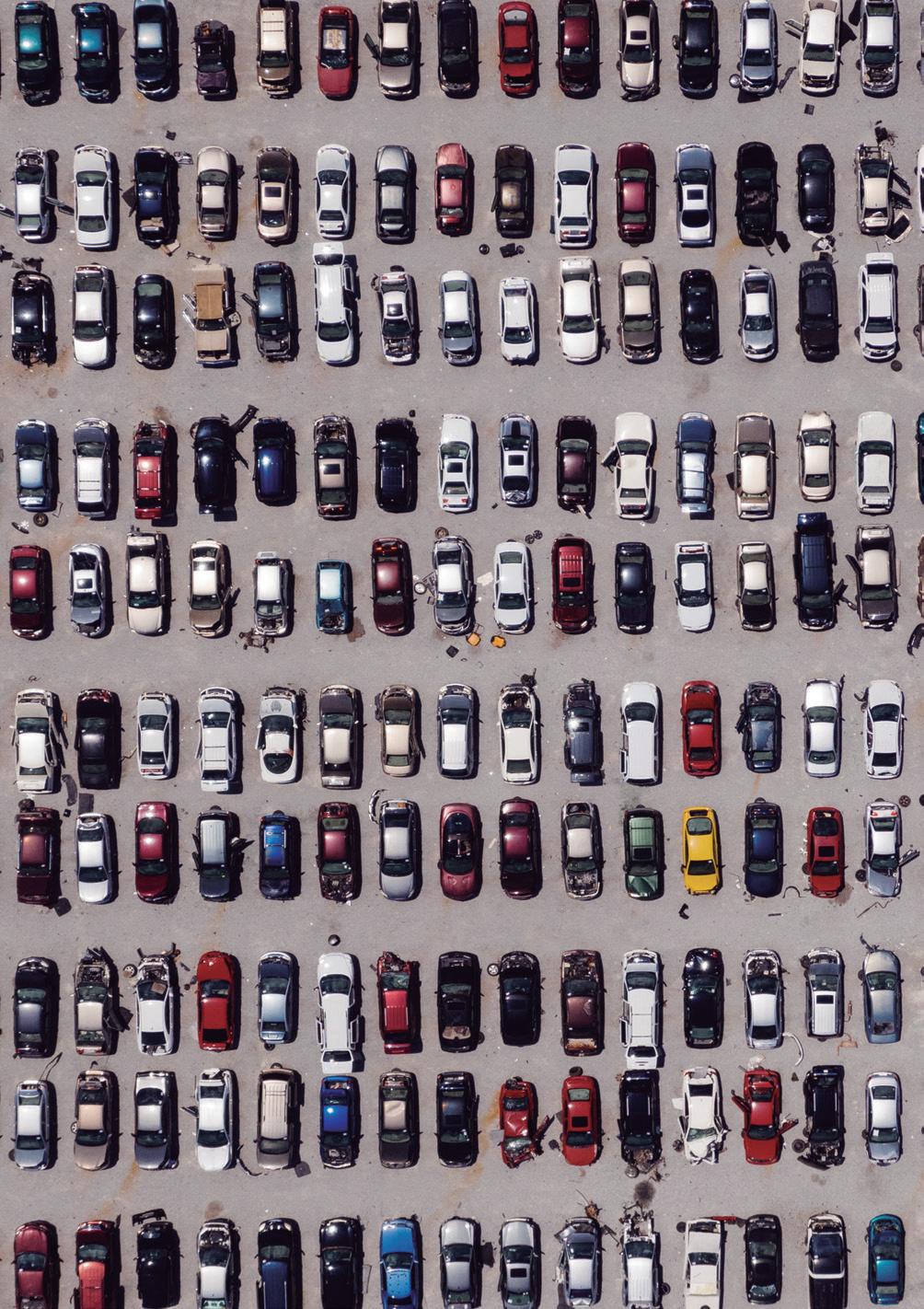

ROADS

The future of our cities

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 39 38 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

Sarah Birch

Coches y carreteras. El futuro de nuestras ciudades

There is no doubt that we have a car problem in Gibraltar, with simply too many cars packed into too small-a-space. You may think that this mounting issue, together with increased public awareness of its implications would incite people to support much-needed change. However, it seems that car culture is so deeply embedded, that very few are willing to give it up.

Figures from 2015 show that there were 32,637 vehicles registered in Gibraltar at that time. More recently, during the four years between 2016 to March 2020, new vehicle registrations came in at a rate of 200-300 per month. So even when allowing for scrappage, it is probably safe to say that up to the first quarter of this year there were more than 40,000 registered vehicles in Gibraltar. And with the import duty embargo earlier this year that included petrol and diesel vehicles, that number could well have risen.

These numbers are just not conducive with our minuscule 50kms of road-network in terms of space and impacts everything from our severe levels of air pollution, lack of green spaces, our well-being and quality of life. It is estimated that there are 654 vehicles per kilometre of road, making Gibraltar the country with the highest number of cars per kilometre in the world.

With the majority of modern city streets designed and created to accommodate cars, the task at hand is a difficult one. There are, however, several urban centres around the world shifting towards strict anti-car policies or modern urban planning solutions to tackle congestion, pollution issues and climate change. After all, transportation in all its forms accounts for a quarter of all global CO2 emissions.

European cities are making the greatest strides towards curbing car use by using smart urban planning methods to transform their streets. Barcelona recently announced a radical scheme to create ‘superblocks’ within the heavily congested and polluted city centre by grouping nine blocks together and closing them off to traffic, making large areas unsuitable for cars. Intersections will be converted into public squares to ensure that all citizens are no more than 200 metres from a small park.

Copenhagen is now the cycling capital of the world. Following heavy investment into creating innovative cycling infrastructure as well as hefty parking and fuel cost hikes, many citizens have turned away from using their cars daily with an estimated

No cabe duda de que en Gibraltar tenemos un problema de sobreabundancia de vehículos, habiendo demasiados en un espacio tan pequeño. Podría pensarse que este problema, unido a la concienciación general respecto a las complicaciones que deriva, animaría a la ciudadanía a apoyar un cambio muy necesario. Sin embargo, parece ser que la cultura del coche está arraigada hasta el punto de que en realidad muy pocos quieren dejar de usarlo.

Las cifras de 2015 indican que en aquel entonces había un total de 32.637 vehículos registrados en Gibraltar. De forma más reciente, durante los cuatro años transcurridos entre 2016 y marzo de 2020, el registro mensual de nuevos vehículos osciló entre las 200 y 300 unidades. De modo que aun teniendo en cuenta los desguaces, resulta realista considerar que en el primer trimestre de este año había más de 40.000 vehículos registrados en Gibraltar. Y con la demora aplicada al impuesto de importación aplicada a principios de este año, tanto sobre los vehículos de gasolina como para los de gasoil, la cifra bien podría ser aún mayor.

Estos números reflejan una desproporción respecto a nuestra minúscula red viaria de 50 kilómetros en relación al espacio existente así como un impacto integral sobre los severos niveles de contaminación del aire, la falta de zonas verdes, nuestro bienestar y nuestra calidad de vida. Se calcula que hay 654 vehículos por kilómetro de carretera, lo que sitúa a Gibraltar como el territorio con la mayor tasa de vehículos por kilómetro del mundo.

Estando la mayoría de las calles urbanas modernas diseñadas y creadas para dar sitio a los coches, la tarea que se presenta es ardua. Existen, no obstante, numerosos centros urbanos por el mundo en los que se ha maniobrado contra la presencia de coches así como para enconttar soluciones modernas en planificación urbanística destinadas a abordar la congestión del tráfico, la contaminación y el cambio climático. A fin de cuentas, el transporte motorizado representa una cuarta parte de las emisiones globales de CO2.

Las ciudades europeas están llevando a cabo importantes avances de cara a reducir el uso de los coches a través de planes urbanísticos que vienen transformando sus calles. En Barcelona se anunció de forma reciente un drástico programa para crear 'superbloques' dentro del muy congestionado y con-

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 41 40 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

60% of the local population opting to cycle instead.

Going back to 1998, Pontevedra in Galicia did what no other city had done before and ambitiously banned all cars entering the city centre. Over 20 years on, only a quarter of the town allows car access. Although initially met with a lot of criticism from its citizens, most now agree that there is no going back and are in fact, requesting more restriction. Through incrementally introduced measures and good planning, the town has been transformed into a haven for pedestrians. 90% of adults now traverse the small city on foot, and 80% of children walk to school. CO2 emissions have also reduced by nearly 70%.

Over the last few years, other cities have followed suit. London continues to increase congestion charges to deter drivers. Mexico City has introduced car-less days (although this has not been altogether successful with many circumventing the restrictions by using taxis and car shares). New York, Paris, Oslo, Madrid and many more have also introduced measures such as car-free zones, car-free days, private car restrictions and bans on old vehicles.

But renewed urban planning is a difficult task in Gibraltar and cannot be compared entirely with the above cities. There is no room for new road infrastructure, and even expanding and modifying the little roads we have is a challenge, leaving little option but to work with what we already have. Also, as we are surrounded by water on three sides, we do not have an outer city perimeter to limit drivers to the outskirts. Unfortunately, the only way is through, which made closing Line Wall Road one of the few options to try and reduce traffic.

With that in mind, the simplest solution is for our car-centric population to use their cars less and to make conscious changes towards alternative modes of transport or to walk more. This does not imply that people should not own or use a car at all if they choose to, but to make mindful decisions to use them less frequently. People often use the above argument that our limited space means that removing road infrastructure to make way for cycle lanes or green spaces is just not feasible. And whilst that is true under the current levels of car use, it also implies that our small size also means that getting from A to B on foot or via public transport is much easier and quicker than in larger cities (much

taminado centro urbano y ello consiste en agrupar nueve zonas para cerrarlas al tráfico, de modo que grandes áreas urbanas quedan inasequibles a los coches. Las intersecciones serán convertidas en plazas públicas para garantizar que cada ciudadano esté a una distancia máxima de 200 metros del parquecito más cercano. Copenhage se ha convertido en la capital ciclista del mundo. Después de una fuerte inversión para desarrollar una infraestructura saludable promoviendo el uso de bicicletas así como un incremento en los precios de los parkings y el combustible, muchos ciudadanos han optado por dejar de usar sus coches de forma diaria y se calcula que un 60% de la población prefiere desplazarse en bici.

Allá ppr 1998, en la ciudad pontevedresa de Galicia se acometió la pionera iniciativa de prohibir el tráfico de coches en el centro urbano. Más de 20 años después, sólo se puede acceder en coche a una cuarta parte del núcleo urbano. Aun siendo muy criticada inicialmente por la ciudadanía, la mayor para de la misma coincide en que las medidas no tienen vuelta atrás y requiere, de hecho, más restricciones. A través de medidas introducidas de forma progresiva y de una buena planificación, la ciudad ha sido transformada en un remanso para los peatones. El 90% de los adultos se mueve ahora a pie por la ciudad y el 80% de los niños van al colegio andando. Las emisiones de CO2 se han reducudo en casi un 70%.

Durante los últimos años, en otras ciudades se ha actuado de manera similar. En Londres siguen aumentando las tarifas por congestión del trráfico de cara a reducir el número de vehículos. En Méjico DF se han introducido días de menor uso de coches (aunque la medida no ha sido del todo exitosa debido a que muchas personas usan taxis y coches compartidos). En Nueva York, París, Oslo, Madrid y otras urbes se han decretado otras medidas como la designación de zonas libres de tráfico, días líbres de tráfico, restricciones a los vehículos particulares y la prohibición de vehículos con una cierta antigüedad. Pero la renovación de la planificación urbanística constituye una tarea complicada en Gibraltar y no se puede comparar del todo a lo sucedido en las ciudades antes mencionadas. No queda espacio para nueva infraestructura viaria y hasta la expansión y modificación de las pequeñas carreteras que tenemos constituye un reto, quedando así poco margen

42 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 43

like Pontevedra). If in the short term, more people sought to bring about a renewed culture of walking, cycling or using public transport, perhaps modifying our existing roads would become an easier task, met with much less resistance in the long term. What needs to change is peoples often unnecessary reliance on cars and attitudes towards their daily use. But as recently demonstrated with the attempted changes here in Gib, the biggest barrier preventing changes in urban mobility is entrenched habits and behaviours. Appealing to peoples pockets, conscience, health concerns, and even the promise of improved quality of urban life does not seem to be enough of an incentive to break a lifetime of habit and convenience. Resistance to change has never been more evident than in 2020. We have all experienced our fair share of it in the last year, most of which has been difficult, with some embracing it with more dignity than others. The psychology of change is a mountainous subject in itself, but we all know how hard it is to kick a lifetime worth of habits, no matter what they are. So, when Line Wall Road was temporarily closed (whether you feel it was planned well or not), the public outcry against the changes showed that Gibraltar is not prepared for them, leaving two options. There either has to be a 'grin and bear it' approach when feasible plans are implemented, with people acclimatising over time, or there needs to be a sustained hearts and minds campaign to convince enough people to break longstanding habits. But to be honest, how to do the latter, or how long it will take, is beyond me.

Ideally, it should be both. Compared to 10 years ago, there are more and more people cycling in Gibraltar, and there is an improved and more frequent bus service (with electric buses in the pipeline). It seems though that relying on individuals alone will not solve the problem, at least not in the short term. But at the same time, the Government does not seem completely prepared for the onslaught of criticism it faces when making radical changes. Engagement, together with well-planned actions need to come together, much like other cities are trying to do.

However, I am not so naïve as to think that all cars should go. Car priority should primarily go to those who are unable to walk, cycle or use public transport, whether due to disability, illness or age.

más allá de trabajar sobre lo que ya tenemos. Asimismo, al estar rodeados de agua por tres partes de nuestra geografía, carecemos de un perímetro urbano exterior que pudiera limitar el tráfico rodado a las afueras. Lamentablemente, la única manera es actuar por dentro, lo cual conllevó el cierre de Line Wall Road como una de las pocas alternativas existentes para intentar reducir el tráfico.

Con ello en mente, la solución más simple consiste en que los usuarios de coches que viven en el centro reduzcan el uso de sus vehículos y emprendan nuevos hábitos encaminados al empleo de modos de transporte alternativos o a caminar más. Ello no implica que los ciudadanos no puedan poseer o usar un coche si así lo desean, sino más bien que tomen decisiones razonadas de cara a usarlos con menor frecuencia. Hay quien utiliza estos argumentos para señalar que nuestra limitación de espacio implica que reducir la infraestructura viaria para habilitar carriles bici o zonas verdes no resulta materializable. Y siendo eso cierto a tenor del índice actual de uso de coches, también significa que nuestra reducida dimensión urbana conlleva que desplazarse de un lugar a otro bien a pie o usando el transporte público constituye una solución mucho más sencilla y rápida que en ciudades más grandes (caso de Pontevedra). Si a corto plazo más personas optaran por acogerse a una renovada cultura de caminar, usar la bici o el transporte público, puede que la modificación de nuestras carreteras se convirtiera en una tarea más sencilla y con menos obstáculos a corto plazo. Lo que debe cambiar es la frecuente dependencia de los ciudadanos respecto a sus coches así como su determinación de usarlos a diario. Pero según se ha demostrado recientemente a través de los intentos de introducir cambios en Gibraltar, la mayor barrera que impide esas modificaciones en la movilidad urbana proviene de hábitos y comportamientos muy consolidados. Apelar a la economía personal, la consciencia, la preocupación por la salud e incluso a promesa de disfrutar de una mayor calidad de vida urbana no parece ser suficiente incentivo para romper con toda una vida de costumbres y conveniencia. La resistencia al cambio nunca resultó tan evidente como en 2020. Todos hemos experimentado un cambio de hábitos en el último año, la mayor parte del cual ha resultado complicado, y el resultado es que

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 45 44 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

For those of us who want to see fewer cars on our roads and a greener Gibraltar for all, the frustration lies with individuals who are capable of using cars less but choose not to, as well with those who express revulsion and offence at the mere suggestion of using their car less. And then, there are those that resort to nasty and offensive hyperbole towards those trying to enact positive change.

Another problem lies with the fact the most of us view 'progress' through the lens of convenience. The last century has brought about endless innovations, most of which have made daily tasks such as travelling, access to information, goods and services much easier, efficient and accessible. As much damage as transport has created, we cannot deny that cars have afforded those with mobility issues freedom and independence that most of us take for granted and permitted millions of people who live in areas with little employment and infrastructure to travel and work.

Nonetheless, we are now reaching a point where we must address the negative impact some of these convenient innovations have. We need to begin viewing new progress differently, not just as convenient or inconvenient, but as a way to rectify some of the mistakes we have made, to make our cities healthier, cleaner, smarter and enjoyable places to live in the long term. This might mean sacrificing some of the things we know for alternatives that will ultimately be better for everyone.

Many issues need to be tackled in Gibraltar, there is the part its citizens can play, but there is more that our Government can do to nudge people in the right direction. Some attempts (other than Line Wall) have been made, such as increased parking fees, buses and parking zones, but other issues could be addressed such as cross border traffic, longer bus hours, expanded bus service and the number of cars per household. Increased electric vehicle incentives for both businesses and private buyers will also help.

For those of us who can, we need to ask ourselves what it is we want for the future. Gibraltar is already beautiful and unique, but it could be even more so. What we do now could transform our streets, air quality, and our overall health and well-being over the next decade, much like many other cities around the world are trying to do. But as things currently stand, we will not keep up.

algunos ciudadanos lo han asumido de mejor manera que otros. La psicología del cambio constituye una cuestión de enormes dimensiones por sí misma, pero todos sabemos que trabajar duro consiste en dejar atrás una vida de costumbres, con independencia de cuáles sean. De modo que cuando Line Wall Road fue cerrada temporalmente (con independencia de que se pensara que la medida resultara adecuada o no), la reacción ciudadana contra la medida demostró que Gibraltar aún no estaba preparada para la misma, dejando ello dos alternativas. O bien se afronta la aceptación de la misma cuando se implanten planes realizables, con la ciudadanía acostumbrándose con el tiempo, o debe de producirse una campaña ciudadana encaminada a convencer a gente para que se modifiquen los viejos hábitos. Pero para ser sincera, el tiempo y la manera de cómo materializar esa segunda alternativa es algo que me supera.

En un escenario ideal, ambas premisas debieran cumplirse. En comparación con hace diez años, cada vez hay más ciudadanos que usan la bici en Gibraltar y el servicio de autobuses, incluyendo el de modelos eléctricos, se ha incrementado. Parece que confiarlo todo a los ciudadanos no solucionará el problema, al menos no a corto plazo. Pero paralelamente, el gobierno no parece estar lo suficientemente preparado para afrontar la ola de críticas que le coi+nllevaría el acometer cambios radicales.Se precisa por tanto el compromiso conjunto de llevar a cabo actuaciones bien planeadas en la misma línea que se está intentando ejecutar en otras ciudades.

Sin embargo, no soy tan ingenua como para contemplar que todos los coches deberían desaparecer. La prioridad en el uso de los mismos debería encaminarse a aquellas personas que no pueden caminar, usar la bici o emplear el transporte público, sea por discapacidad, enfermedad o edad. Para aquellos de nosotros que queremos ver menos coches en nuestras carreteras y un Gibraltar más verde para todos, la frustración se dirige a aquellos que pueden reducir el uso del coche pero deciden no hacerlo así como hacia aquellos que expresan rechazo y molestia ante la sola sugerencia de que usen menos sus coches. Y finalmente están las personas que recurren a una respuesta excesiva y desagradable respecto a la introducción de cambios positivos.

Otro problema reside en el hecho de que la mayo-

46 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 47

ría de nosotros contemplamos la idea de progreso a través del filtro que más nos conviene. En el último siglo se han producido innumerables innovaciones, la mayoría de las cuales han facilitado actividades como el viajar, el acceso a la información, los productos o los servicios, dotando a todas ellas de mayor eficiencia. Por mucho daño que haya causado el transporte, no podemos obviar que los coches han proporcionado libertad de movimiento e indepedencia que ahora la mayoría damos por sentadas, permitiendo que millones de personas que viven en zonas con bajo índice de empleo e infraestructuras se desplacen y trabajen. En cualquier caso, estamos llegando a un punto en el que debemos abordar el impacto negativo causado por algunas de estas innovaciones. Hems de empezar a contemplar el progreso de forma diferente y no sólo desde el prisma de lo que nos conviene o no nos conviene, pero como forma de rectificar algunos de nuestros errores está el convertir nuestras ciudades en lugares más saludables, limpiar, elegantes y disfrutables en las que vivir a largo plazo. Ello puede conllevar el sacrificio de algunos de nuestros hábitos a cambio de alternativas que resultarán mejores para todos.

Hay varias cuestiones que abordar en Gibraltar. Por un lado, el rol que pueden desempeñar los ciudadanos, por otro actuaciones a adoptar por el Gobierno para encaminar a la ciudadanía a la dirección acecuada. Algunos intentos (aparte del de Line Wall) ya se han acometido, caso del incremento del pago por aparcar, del número de autobuses y del número de plazas de parking, pero podrían abordarse otras cuestiones como las del tráfico transfronterizo, la ampliación de los horarios de los autobuses, el incremento del servicio de autobuses y el número máximo de coches por vivienda. También contribuirían a este objetivo el incremento de incentivos para el uso de vehículos eléctricos tanto para empresas como para particulares.

Aquellos que podemos hemos de preguntarnos qué es lo que queremos para el futuro. Gibraltar es ya un lugar bello y único, pero podría serlo aún más. Lo que hagamos ahora podría transformar nuestras calles, mejorar la calidad del aire así como nuestra salud y bienestar en general a lo largo de la próxima década del mismo modo que se está intentando en otras muchas ciudades del planeta. Pero en el actual estado de las circunstancias, no podremos mantener el ritmo.

48 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 49

THE MYSTERIOUS CAVE PAINTINGS OF THE TASSILI N'AJJER PLATEAU, CENTRAL SAHARA (ALGERIA).

LAS MISTERIOSAS PINTURAS RUPESTRES DE LA MESETA DE TASSILI N’AJJER, SAHARA CENTRAL. (ARGELIA).

Hugo A. Mira Perales.

Photographs: www.roundheadsahara.com

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 53 52 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021

The great Tassili Plateau is located in the heart of the Sahara Desert, it is considered one of the warmest places in the world. With a total surface area of more than 9,400,000 km2 it occupies practically most of North Africa. It's size is comparable to that of the United States. The Tassili N’Adjjer Natural Park is located in the southeast of Algeria. The closest city to the park is Djanet, just 10 kilometres southwest of the mountain range. The rocky plateau reaches a maximum height of 2,158 metres above sea level, with the peak of Adrar Afao visible from a great distance.

The rocky landscapes that make up the Tassili Natural Park are extremely arid. Erosion has shaped the surface of the rock, creating the most curious formations, such as rock arches, canyons between mountains, etc. The current surface of the Tassili plateau is very similar to that found on Mars. This strange landscape, which in the past housed a natural garden, where water was a predominant part of its scenery, has been reduced to one of the driest areas on the planet. Among the rocks, lying in silence due to the passage of time, is one of the most important and lesser-known prehistoric rock art complex’s in the world. Human settling in this part of Algeria and its neighbouring countries can be framed at a time when the Sahara was reoccupied due to climate change at the beginning of the Holocene, during the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene era. This abrupt change made the Sahara a more humid place, displacing the population to the unpopulated areas of the mountains, due to the formation of rivers and lakes. This is where most of the rock enclaves can be found. We can estimate that the rock manifestations have a chronology of between 9,0003,000 years B.P., using the lithic industry found in the area as reference, which also took place during these time periods. It is currently difficult to calculate the total number of motifs or scenes that were recorded and painted in the area. We estimate that only 25% of them are preserved today, with erosion that devastated the plateau the main cause of their disappearance.

In the Tamashek (Tuareg) language, Tassili n’ajjer means “The Plateau of Rivers”, due to how easy it is to detect the marks formed by the great riverbeds of the past. At present, human existence here is prac-

La gran Meseta de Tassili, situada en pleno desierto del Sahara, considerado el más cálido del mundo, con más de 9.400.000 km² de superficie, ocupa prácticamente la mayor parte de África del Norte, con una extensión equiparable a los Estados Unidos. El Parque Natural de Tassili N’Adjjer, se ubicada en el sudeste argelino. La ciudad más próxima al parque es Djanet, a tan solo 10 kilómetros al sudoeste del circuito montañoso. La meseta rocosa llega a alcanzar alturas máximas de 2.158 m.s.n.m. con el pico de Adrar Afao, visible a grandes distancias. Los parajes rocosos que conforman el Parque Natural de Tassili, son de una aridez extrema, la erosión ha moldeado a capricho la superficie de las rocas, creando formaciones de lo más curiosas, arcos de roca, cañones entre montañas, etc. La superficie actual de la meseta de Tassili es muy similar, a las que se encuentran en el planeta marte. Este extraño paisaje que en el pasado albergo un vergel natural, donde el agua era parte predominante del panorama, quedado reducido a una zona de las más áridas del planeta. Entre las rocas yacen silentes por el paso del tiempo, uno de los conjuntos prehistóricos de manifestaciones rupestres más importantes y menos conocido del mundo. La ocupación de esta parte de Argelia y países limítrofes, se puede enmarcar en un momento de reocupación del Sahara, por el cambio climático producido a principios del Holoceno, en la transición del Pleistoceno al Holoceno. Este cambio brusco hizo del Sahara una zona más húmeda, desplazando población a las zonas despobladas de las montañas, por la formación de ríos y lagos. Apareciendo en estos lugares rocosos la mayoría de los enclaves rupestres. Con lo cual podemos estar hablando de una cronología para las manifestaciones rupestres de entre los 9.000-3.000 años B.P., tomando como referencia la industria lítica, aparecida en la zona, que se ha situado en esos periodos de tiempo. Actualmente es difícil de contabilizar el número total de motivos o escenas que se grabaron y pintaron en la zona, podríamos hablar de que hoy en día solo se conserva un 25% de su totalidad, siendo la principal causa de su desaparición, la erosión que devasta la meseta.

En la lengua Tamashek (Tuareg), Tassili n’ajjer significa “La Meseta de los Rios”, pues es fácil localizar las marcas de los grandes cauces de los ríos que se formaron en el pasado. En la actualidad la vida

OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 55

tically impossible, due to extreme temperatures and scarcity of water.

The Tassili n'ajjer area became known in the 19th century, when European military expeditions in their quest to dominate and control the African continent, identified the different areas of the Sahara Desert. These expeditions were accompanied by adventurous individuals, who discovered the existence of paintings and engravings in the rocks of the great plateau. One of the first explorers was the German Heinrich Barth, but it was not until 1930 that the historical community began to give importance to Saharan rock art. While Algeria was under French rule, several expeditions were carried out across the Sahara to some of the most challenging and inaccessible areas, such as the great plateau of Tassili n’ajjer located in Central Sahara. During one such expedition in 1932, a soldier from said contingent with an adventurous spirit named Brenans entered the steep canyons within the rock formations where he discovered a series of animal engravings within its walls. There he observed elephants, giraffes, rhinos, antelopes, lions, and countless human motifs. This spectacular discovery garnered a lot of interest from the European historical community. But it was not until 1956 that the Swiss, Yolande Tschudi, first produced a publication about this cave enclave. That same year, the Frenchman Henri Lhote organised a yearlong expedition to the Sahara for the exploration, study and documentation of the paintings and engravings distributed on the rocky walls of the Saharan plateau. The team comprised of painters, to make copies of the motifs, and a photographer, and was also supported by the participation of the Tuaregs of the area, who are perfectly familiar with the complex passages to access the different rock enclaves. One of the main guides and specialists of the area was Mechar Jebrine. (Figure 1).

Here is the text that Henri Lhote wrote in his journal, in which he describes the difficult ascent to reach the enclaves of the great plateau:

“The beasts are breathless from the effort; the climb is becoming increasingly steep and the mass of boulders ever more imposing. Some camels collapse under their load which then rolls down the cliffside; men must assist with everything. Traces of blood can be seen on the pebbles, since without

humana es prácticamente imposible, debido a las temperaturas extremas, y la escasez total de agua. La zona de Tassili n’ajjer se empezó a conocer en el siglo XIX, cuando las expediciones militares de países europeos en su afán de dominar y controlar el continente africano, reconocían las diferentes zonas del desierto del Sahara, siempre acompañados de personas aventureras, dando estos a conocer la existencia de pinturas y grabados en las rocas de la gran meseta. Uno de los primeros exploradores fue el alemán Heinrich Barth. No siendo hasta 1930 cuando se empezó a dar importancia por la comunidad de historiadores al arte rupestre sahariano. Estando Argelia bajo el dominio Francés, se llevaron a cabo varias expediciones, que recorrieron el Sahara, llegando a las zonas más complicadas y de difícil acceso, como la gran meseta de Tassili n’ajjer, situada en la zona del Sahara Central. Siendo en una de las campañas expeditivas en el año 1932, cuando un militar de aquel contingente con espíritu aventurero, llamado Brenans, se adentró entre los escarpados cañones de formaciones rocosas, para descubrir una serie de grabados de animales entre sus paredes, observo elefantes, jirafas, rinocerontes, antílopes, leones, e infinidad de motivos humanos. Este espectacular hallazgo levantó mucho interés en la comunidad histórica europea. Pero no fue hasta 1956 cuando la suiza Yolande Tschudi realizo la primera publicación sobre este enclave rupestre. Siendo ese mismo año, cuando el francés Henri Lhote, organizo una expedición al Sahara que duro casi un año, para la prospección, el estudio y la documentación de las pinturas y grabados que se encontraban distribuidas en paredes rocosas de la meseta sahariana. Contando en el equipo con pintores para realizar copias de los motivos, un fotógrafo, y todo ello apoyado por la participación de los Tuaregs de la zona, conocedores a la perfección de los complicados pasos para acceder a los diferentes enclaves rupestres. Uno de los principales guías y conocedores con exactitud la zona, fue Mechar Jebrine. (Figura 1).

A continuación el texto que Henri Lhote anoto en su diario, en el cual describe el ascenso tan complicado para llegar a las zonas de los enclaves en la gran meseta:

“Las bestias tienen cortado el aliento por el esfuerzo, la rampa es cada vez más empinada y la mole de pedruscos se va haciendo más imponente. Algunos camellos se desploman bajo la carga que cae

56 OTWO 18 / JANUARY 2021 57

Figure 1. Henri Lhote tracing.

one exception, all have skinned legs and hooves that have been damaged on the sharp edges of rocks. The animal that carries the big boxes with the drawing boards has just collapsed under its load, it has hit a rock and it is clear that it will never be able to get up. I order the boards to be removed and I make the decision that we must carry them on our shoulders. Each one receives his share and from here begins the ordeal for us all, because the top is still not visible, and the path becomes more and more steeper under our feet ... "

H. Lhote came to document and duplicate almost four hundred scenes throughout the course of the expedition. All the collected materials were displayed in an exhibition that opened in Paris in 1957, which was a great success due to the uniqueness of the motifs. Due to all of this, he was considered the great discoverer of Saharan rock art.

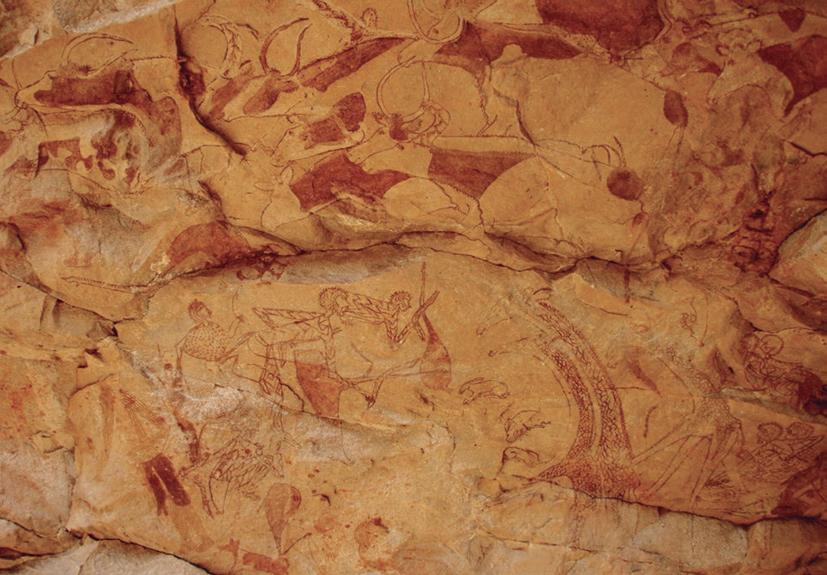

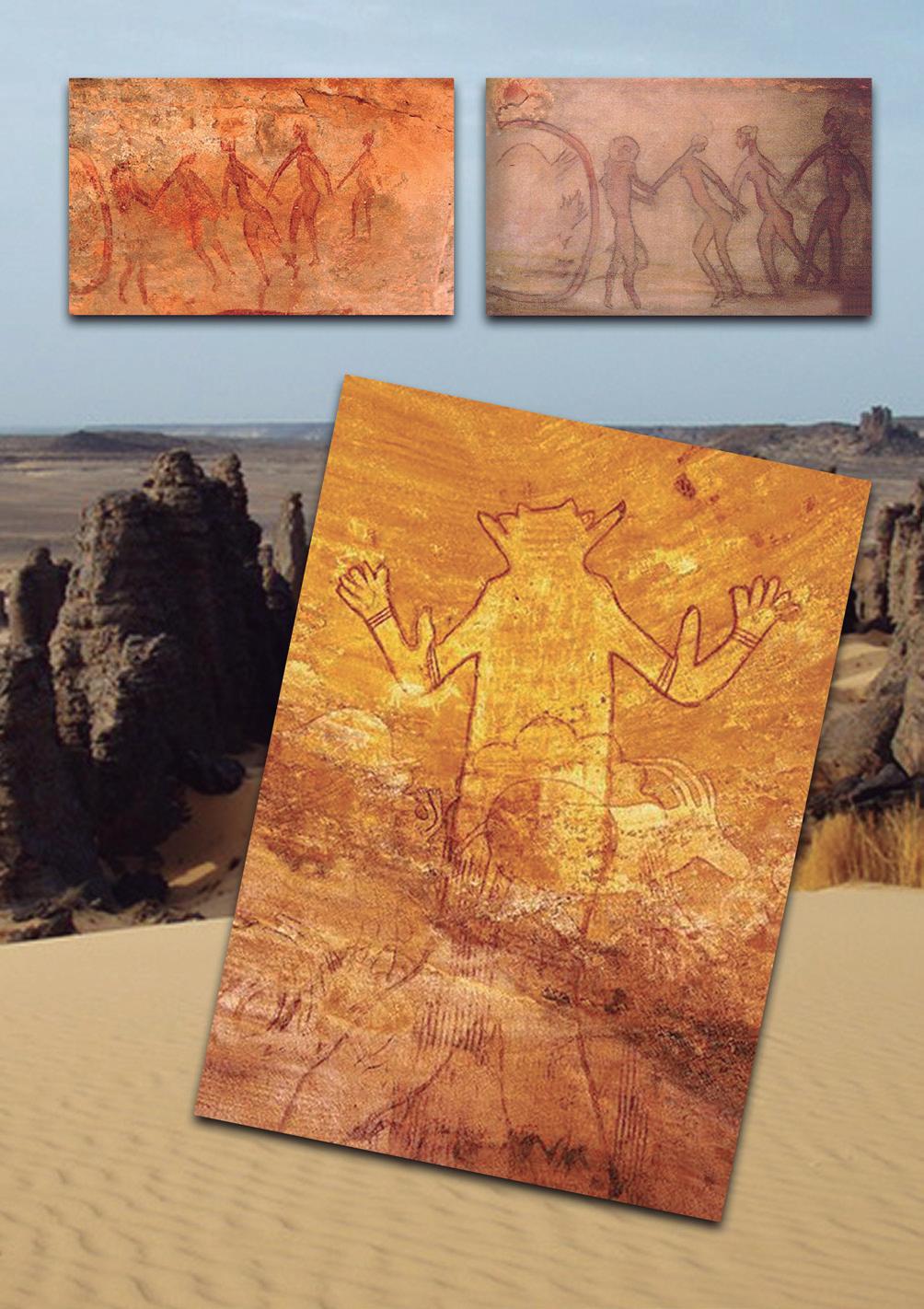

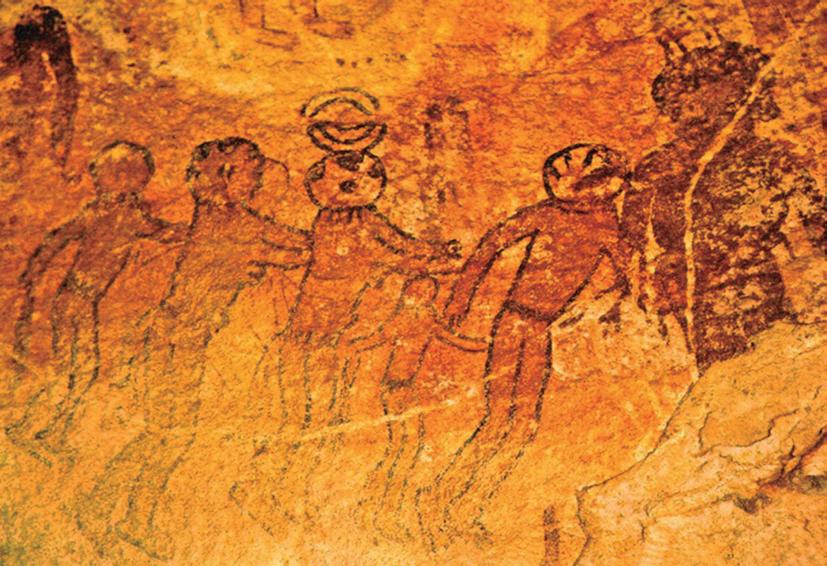

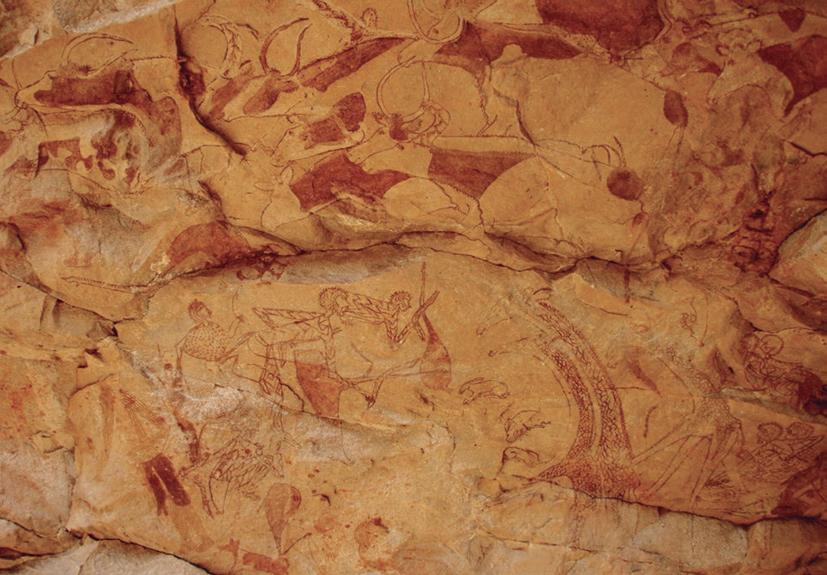

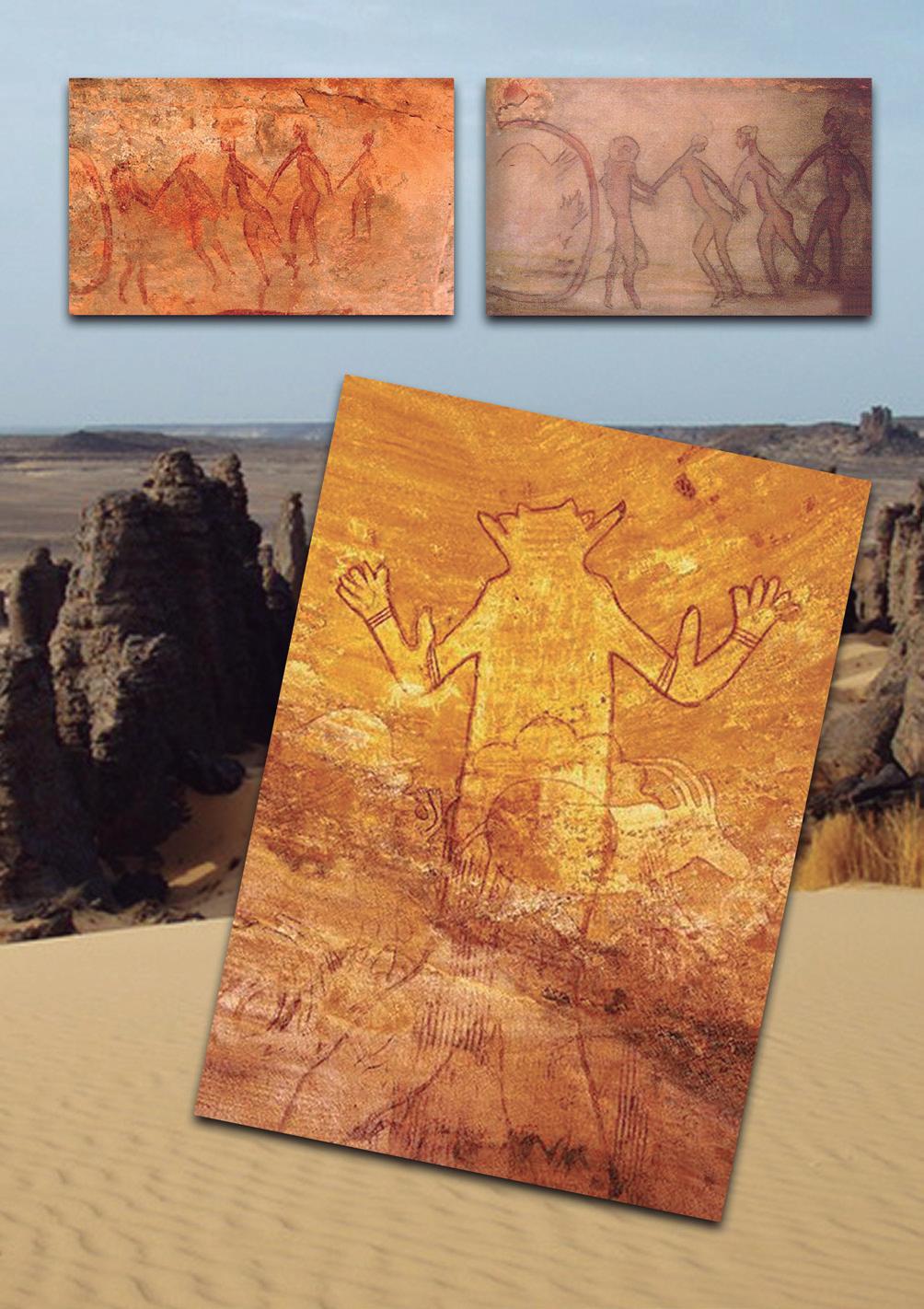

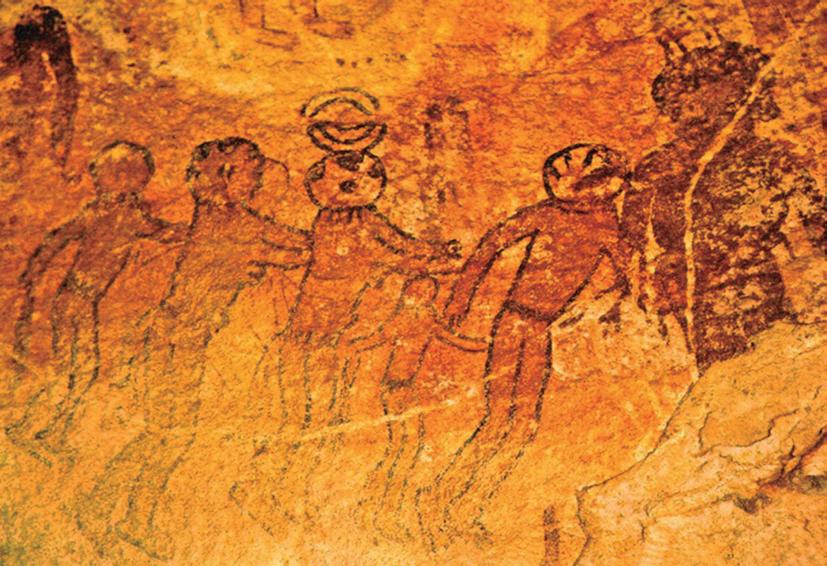

The rock art of the Tassili plateau is made up of engravings, isolated motifs and pictorial scenes, with most of the paintings found in very specific areas. The entire rock complex extends to the Tadrart Acacus area in Libya. Saharan cave paintings are represented on the rocky walls, in the open air, in barely protected shelters and vertical walls. The motifs and scenes that are considered the oldest in Tassili, are the anthropomorphic paintings called "Round Heads", a human form with a circle attached directly to the body, where in most, there is no neck present. (Figure 2).