RESTRICTIVE CITY

Onoseta Felix-Ilemhenbhio | ofelix-ilemhenbhio@uclan.ac.uk

PAGE OF CONTENTS

Abstract Page 04

introduction Page 06

The Rational City Page 10

History as fiction Page 12

The fiction of Representation Page 10

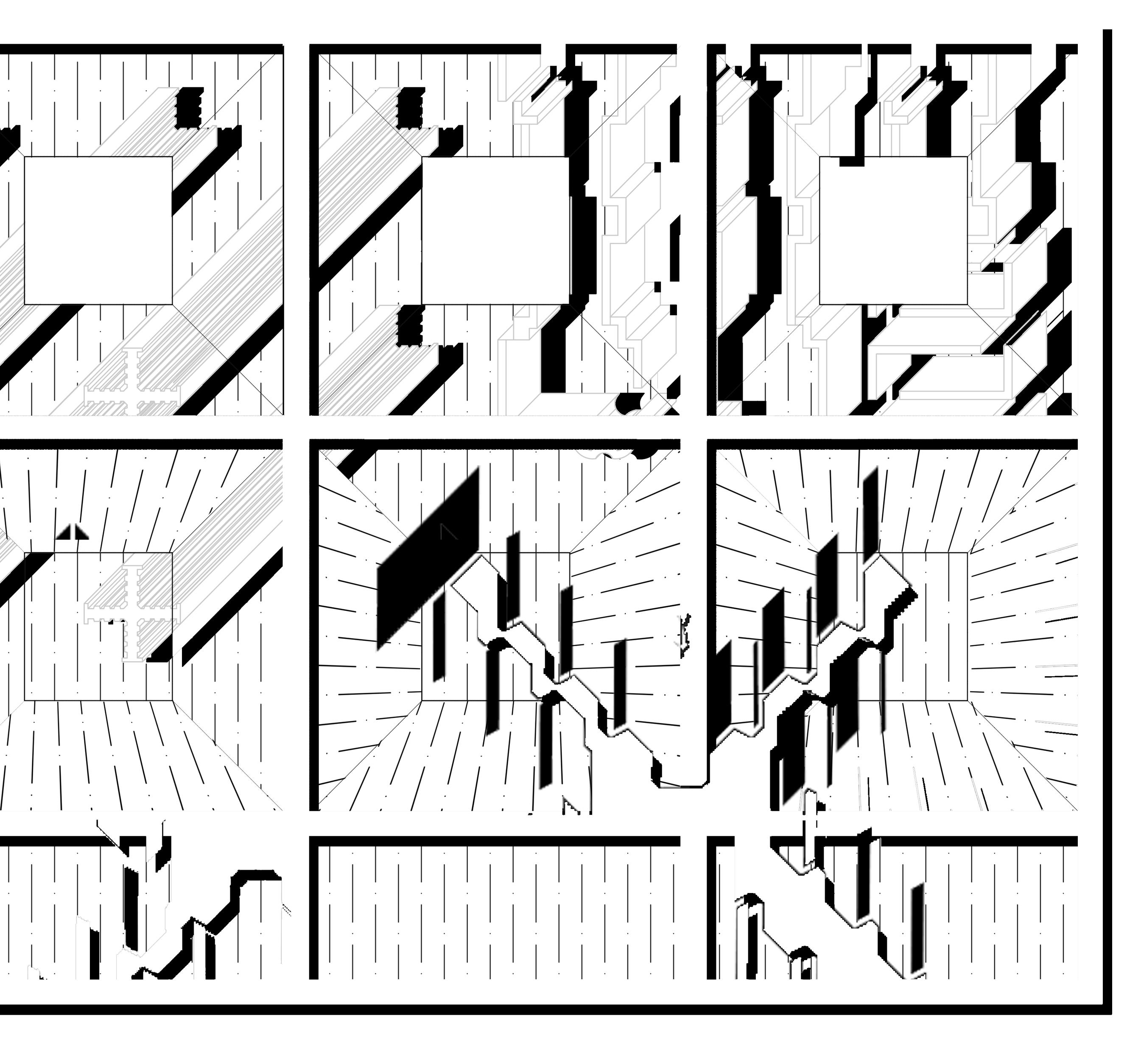

Suite of analytical drawings Page 11

Replicas of replica Page 20

Final artefact Page 26

Dissimulation Page 30

Architecture as languange Page 32

Conclusion Page 34

Bibliography Page 36

RESTRICTIVE CITY

Abstract

The architectural object of this analysis is the urban design of Le Corbusier, this essay intends to analyse Ville Contemporaine through Eisenman’s fictions, which are the following: Repre sentation, Reason, History, and ultimately through the defini tion of Architecture as language. The title of the following es say is ‘Restrictive city’. A restricted city is an ideal city in which order is derived from the fiction of reason, it is a city that has renounced its history, and has alluded to timelessness. The restrictive city views every component- including mankind, as an object that needs to be placed within its context. With a focus on the exploration of the notion of restrictive spatial designs within the city, this paper aims to discuss the post-modern ist ideology of architecture as a linguistic construct. Further more, it will discuss Eisenman’s philosophical notion of the classical in relation to what was designed to be its antonym.

UNDERSTANDING THE CITY AS A LINGUISTIC CONSTRUCT

Introduction

In the introduction of The City in History, Lewis Mumford asked: “What is a city? How did it come into existence? […] What purposes does it fulfil?” (Mumford, 1969) From, Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), Le Corbusier’s Contemporary City for Three Million inhabitants (1922), The city in the city manifesto (1977) or Aldo Rossi’s Architecture of the city (1984), the city has always been an “idealized reality for the projection of a society’s ideology” (Mumford, 1969). For More, it is an egalitarian city, one shaped and function ing like a machine governed by reason for Le Corbusier. A city composed of adaptable polycentric urban landscapes to Ungers and Koolhaas (Oswald Mathias Ungers and Rem Koolhaas with Peter Riemann, n.d.). and, an architectural typological reality of objects subjugated to perpetual trans formation for Rossi (Rossi, 1984). Across theoretical litera ture, the ideal modern city –the one of a new order, was a proposed scientific effort, one that tasked the architect to find rational solutions to contemporary urban queries.

With the advent of the industrial society- in the late nineteenth century, modernism attempted to simulate and solve realism through reason (Eisenman, 1984). There fore, implying that the research for universal rational val ues could not be attained through the representation of previously valued architectural expression (Eisenman, 1984). Rather, it needed to simulate the meaning of truth, thus reasserting that rational architecture was not just a simulation of reality but also the organisation of the latter. Despite the articulated rupture in both ideology and style associated with Modernity; according to Eisen man the three fictions (reason, representation, history) have never been questioned and therefore remain intact.

This is to say that architecture since the mid-fifteenth cen tury aspired to be an epitome of the classic, of that which is timeless (through the fiction of history), meaningful (through the fiction of representation), and true (rational). Hence, the concept that personifies the rational mind as the agent of the production of timeless architecture is un enforceable. With Post-modernism came the recognition of Architecture as a linguistic construct. Ultimately, the com prehension of the latter determines the limits, organisa tion, stylistic manifestation, and scales of the production of urban environments. Ergo, restrictions -in the conceptual and tangible development of the urban landscape - occur upon the proclaimed supremacy of a fiction (reason for the rationalist) in the continued discourse of architecture.

As highlighted in the abstract, restrictive practices are not sorely exclusive to the spatial manifestations, nor the volu metric elements of design - they are transcendental to the real limitations that take place in the rational mind. The pri orly stated is the point of rupture between modernists the likes of Le Corbusier and post-modernist architects, such as Eisenman. To facilitate the discussion of the subject matter, the essay has been structured into two parts: the Rational city (an exploration of Ville Contemporaine, the rational mind, and its fiction) and the notion of Architecture as a lan guage. One will reveal the concrete and abstract limitations of modern city planning, whilst the other will liberate the city. Successful comprehension of the notion of a Restrictive city commences with the analysis of the Rational city: its theories, extremism, historical context and need for order.

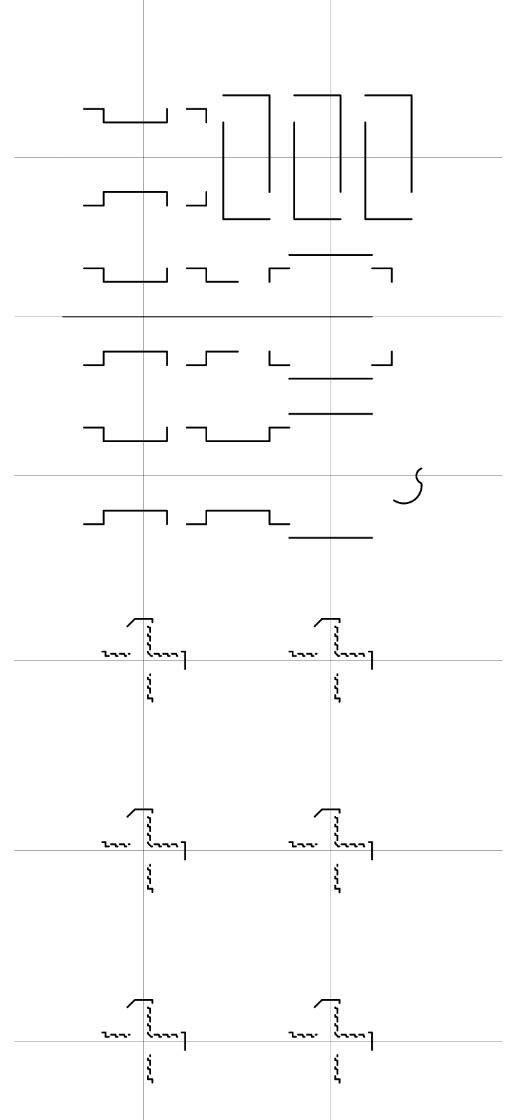

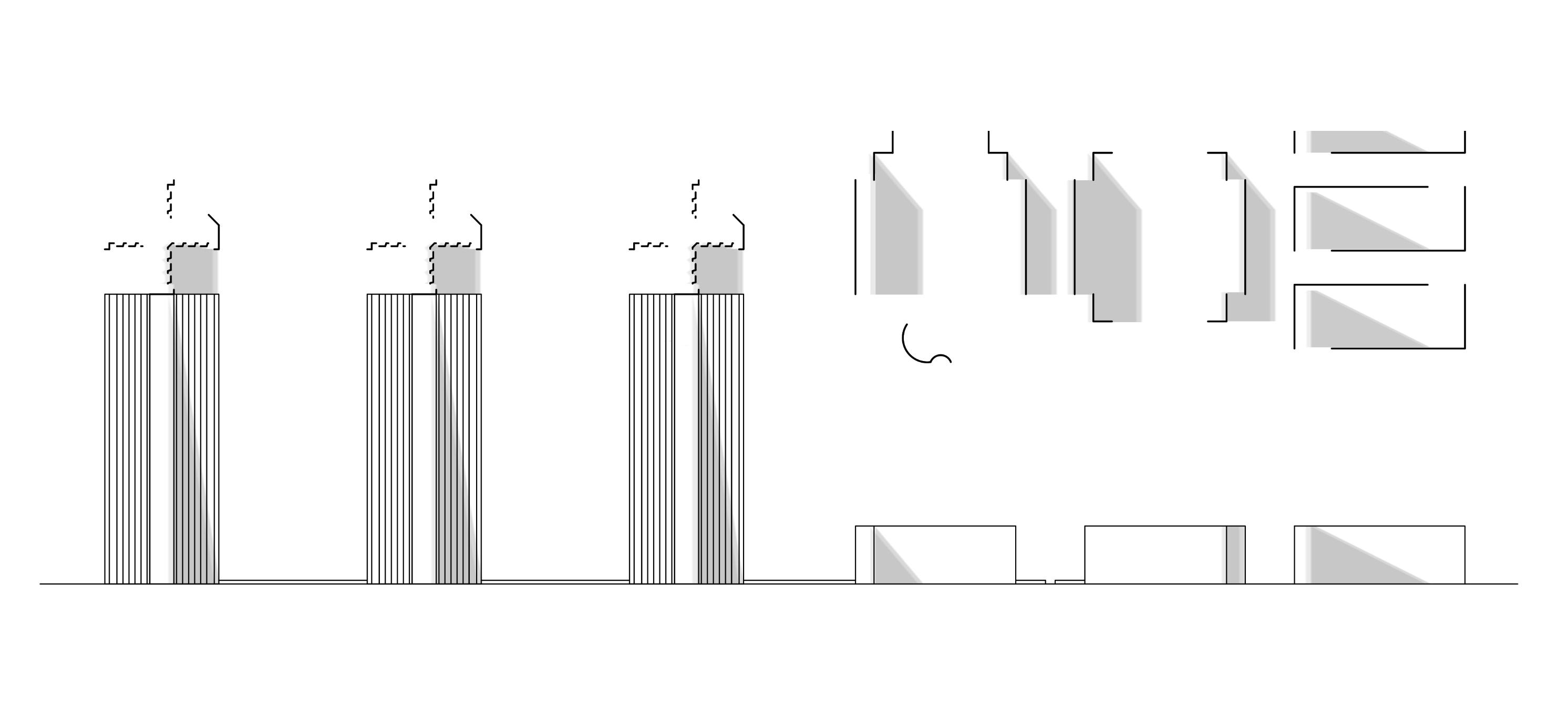

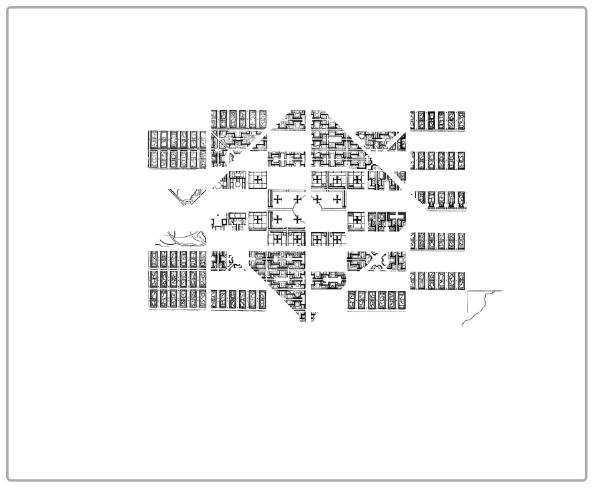

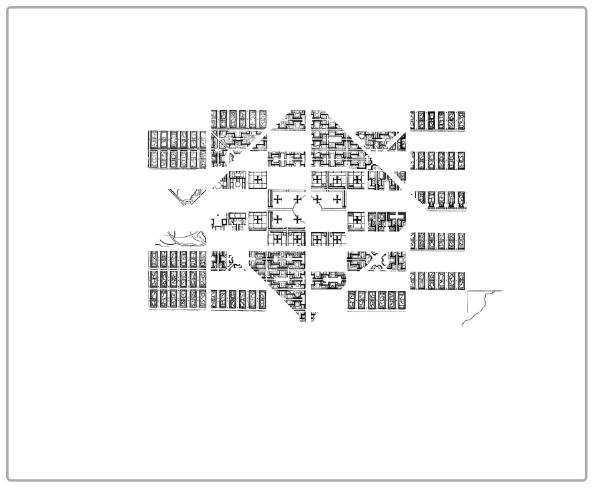

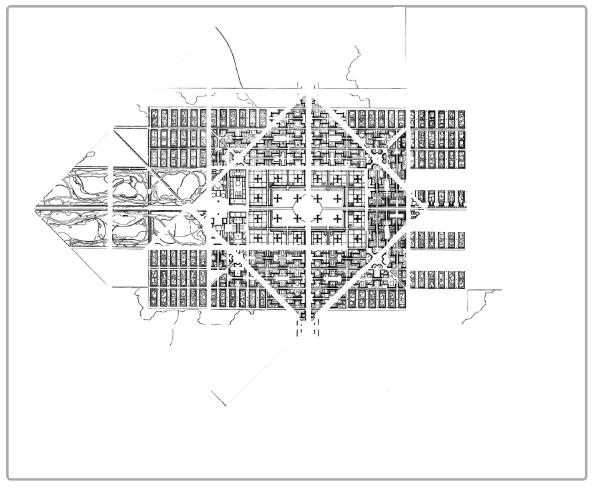

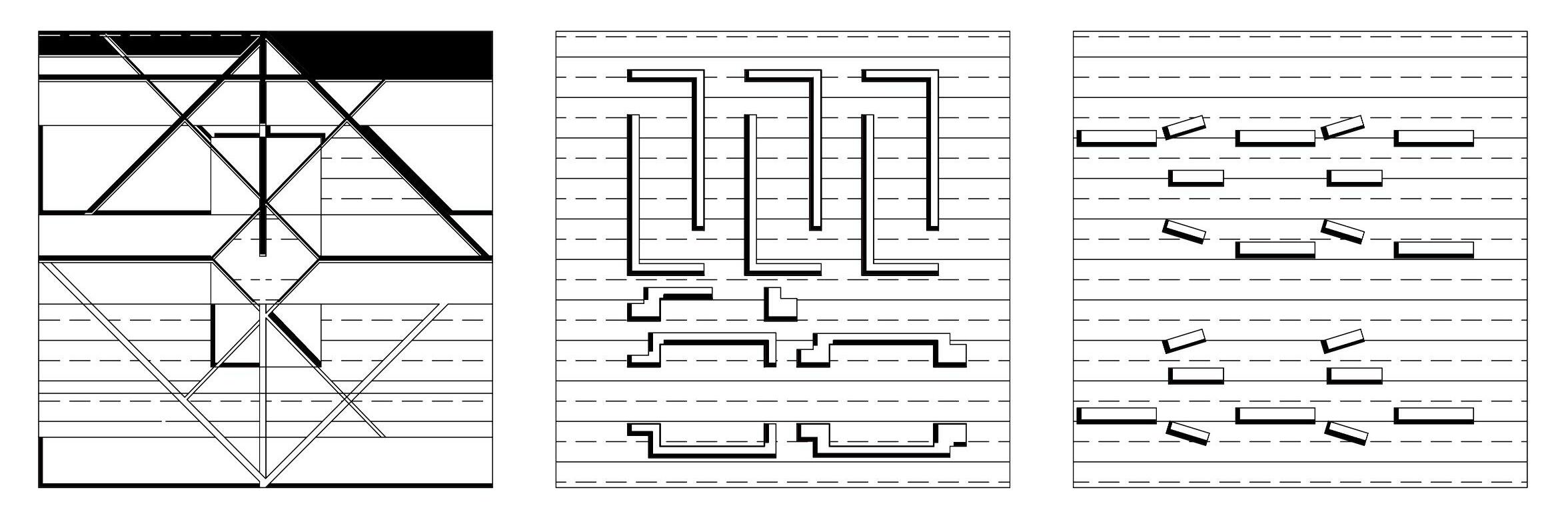

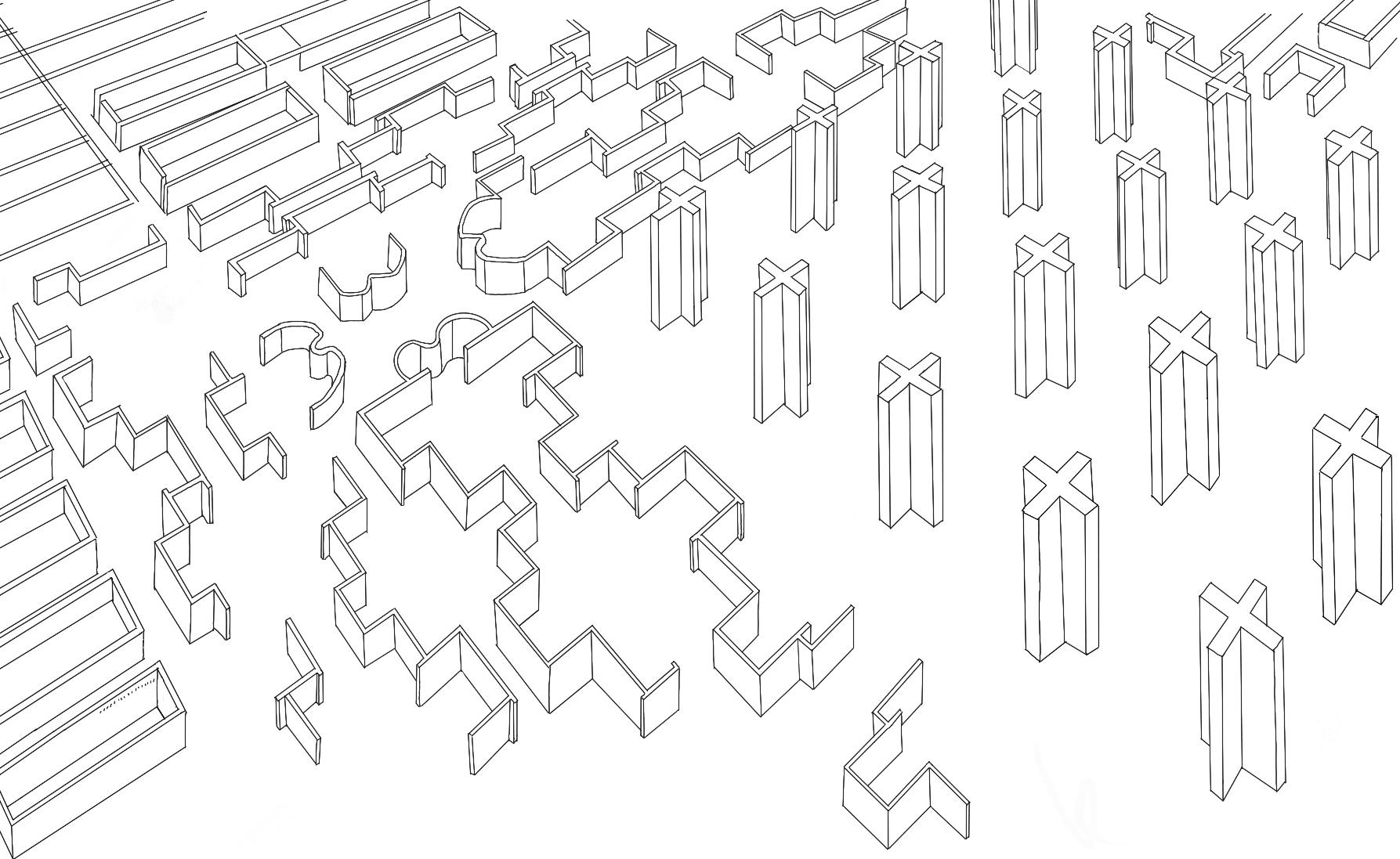

Extrapolating order through line drawings.

Ville Contemporaine -absence of order.

Architecture and urban planning subservient to the rational mind

Chaos is the birthplace of the rational city (Etchells, 1971). Le Corbusier diagnosed and devised a treatment for the urban conditions: the City of tomorrow and its planning is an archetype. Perhaps it is better to align the birth of the rational city with the Modernist’s quest for the origin of ar chitecture, as they shared the same intention: to produce a logical secular autonomous urban reality. The city, a com plicated machine “can only adequately function on a basis of strict order” (Etchells, 1971). Corbusier‘s order commenced with classification (Tafuri, 1969). Such for instance the need to subdivide the population into classes to facilitate the al lotment of the three sections and the delimitation of their boundaries (Etchells, 1971) The residential blocks were en closed auto-sufficient cellular systems in which geometry and spatial designs were conceived toward the manage ment of urban growth. A similar modus operandi was then applied to street planning, where types of streets were devised and classified to ensure uninterrupted movement. The city, a dynamic landscape, needed to be interconnect ed and free of congestion. Ville Contemporaine is a utopic manifestation of Le Corbusier’s rationalism which aim was to produce a democratic, free urban landscape. The ratio nal city is a city of objects, and its architect is the organiser of such objects. The project compromised of four main ob jectives (visible at multiple planes): geometry, framework, hierarchy, and function. The latter is the tools of spatial and analytical organisation of the four objects: the tower block and the green spaces, the residential spaces (sub divided into 3 classes), the street and protected spaces.

Tafuri suggests that Le Corbusier gradually tested and de veloped the most in-depth system of rational plans at var ious scales and implemented them in other projects (Tafuri, 1969). Plan Voisin is the case in point, where the assimilation and rejection of American architectural geometry were in corporated into the Parisian mechanical modernity. Tafuri saw his project as the rationalization of the total organi zation of the urban machine using the technique of organic unity. It was a cellular idealistic organisation like Ville Con temporaine; that resulted in Tafuri concluding in his critique that rationalism and its obsessive repetition have reduced the urban organism into a useless machine (Tafuri, 1969). Eisenman’s theory of fiction partially supports this concept. The fiction of reason provides a fragmented expression of the totality of the concept of urban. The city as described by Rossi is a unified element of architecture, a synthesis of permanent and temporary parts. In this, the rational city, and the restricted city alike- fail in their totalism. The ex pressed fictional supremacy further cements the displace ment of the progressive plan in the topos of architecture. The restricted utopia has no intrinsic value, its meaning and essence are bestowed upon the promise of order and like its streets, it becomes a nonstop ‘no place’. Nevertheless, the ‘no place’ should not be completely discarded as it is an endeavour pivotal to the discernments of extremist ur ban configurations and theories alike. The restrictions are similarly applied to the grid and the city’s ability to prog ress; as order, and therefore perfection has been obtained.

The Rationale is not the real limitation; it is the ideology that sorely through reason can the architect produce an atemporal universal architecture. It is in the certainty and imposition, that reason fails to recognise the other narra tives at play. Whether the restrictive city is a type of ra tional city or a continuation of the latter, it is subjected to the formal referential representations of modernism. This is not to say that what is designed to be logical or beautiful is restrictive per se, but it is to recognise that in the attempt of distinguishing oneself, the expression of each stylistic movement has enclosed its phenotyp ical expression to what was the zeitgeist of its time is.

Simulation of the timeless.

The rejection of all or any history is a phenomenon traceable to the 19th-century modernist (Eisenman, 1984). To further highlight the enclosures of a restrictive utopia, the fiction of history needs to be discussed. On the right, is a picture of Statue of Pasquino (Rome), a fragment of a statue whose function is other than any representational historical monu ment (Rossi, 1984). The Pasquino statue is one of six series of talking statues of Rome. The statue is referred to as talking as it was and still is an outlet dedicated to satirical or dissi dent narratives for the city of Rome. The base is where the notes are attached, the place where collective memory is formed. The collective memory is fostered by a place where, according to Rossi, resides the consciousness’ of the city (Rossi, 1984). The urban artefact, a permanent unit of the city sum, is the locus of reconciliation of past and present ur ban impressions. it is where the idea of place and time com mune and are expressed rationally. In the case of the sculp ture, the function of the statue has mutated and therefore speaks of an in time, in the now of its time. Paradoxically, the modern commitment to the anti-historical was a failed attempt toward timelessness (Houdrouge, 2018). Ville Con temporaine (VC) was an ideation of the new city, therefore, ought not to take the configuration of what was known. The new modern man, the one who walks in a straight line in an orderly manner (Etchells, 1971), could only inhabit a new city, one that matched the efficiency and innovations of industrialisation (Eaton, 2002). In efforts of rationaliz ing the irrational, the fundamental working of perception and memory were foregone. The rational symmetry and repetitive patterns of objects might suggest another type of space: the labyrinth. The philosopher Hubert Daminsch, referred to the lack of perception and use of the labyrin thian in the urban landscape as absurd (Houdrouge, 2018).

The absurdity is cemented in the lack and refusal of histori cal representations and the derived locus. Without the locus, the integral parts of the whole are displaced. Hence, the idea of a tabula rasa was perceived by other theorists as a dis placement of place and building and incapable of attributing enduring value to the fabric of the city. The deracinated in habitants, already isolated in three sections, are suspended in large terraces at the sight and sound of zooming vehicles, at the mercy of the two-hundred meters tall tower blocks. Consequently, the utopia and its inhabitants are tethered to the regressive illusion, in an ironic surrealist extreme reality.

Rational order is embedded within the grid, and it defines the arrangement of the other object.

1. asymmetry 2. The abstract grid 3. Void 4. Residential

FICTION OF REPRESENTATION

Rational order is embedded within the grid, and it defines the arrangement of the other object.

1. Composition 2. Exception 3. Nucleus 4. Repetition

THE FICTION OF REPRESENTATION

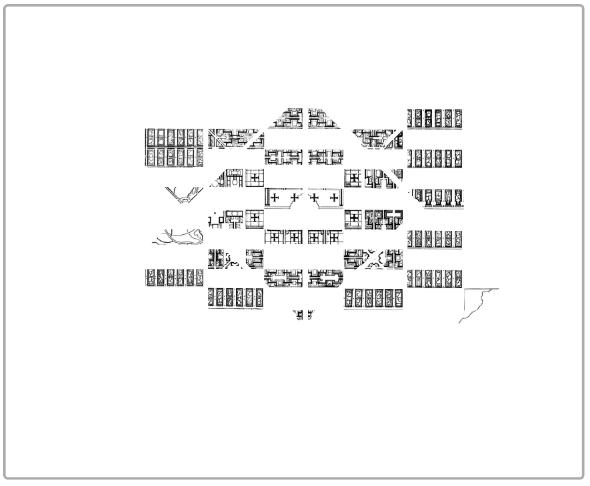

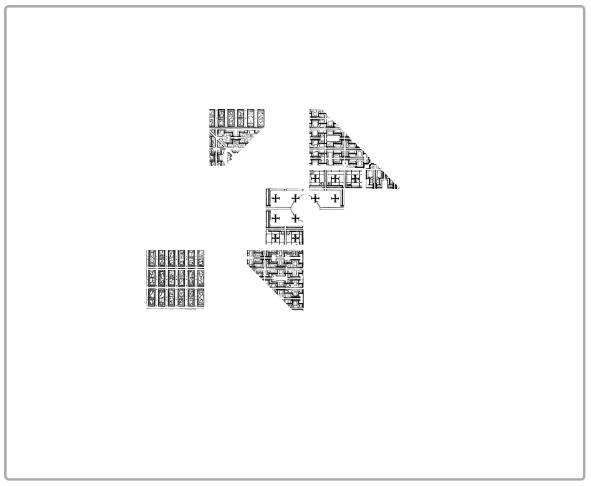

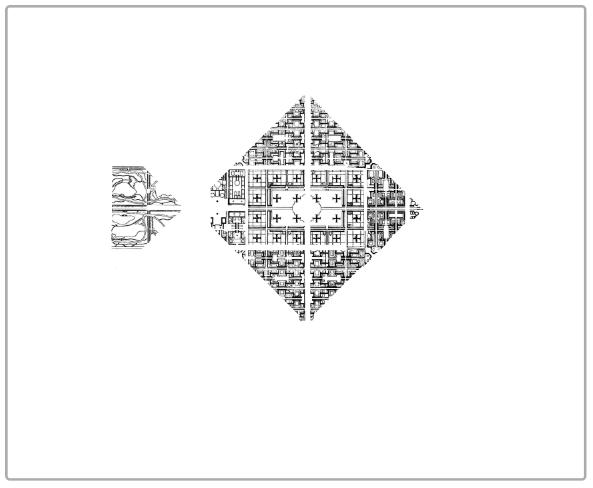

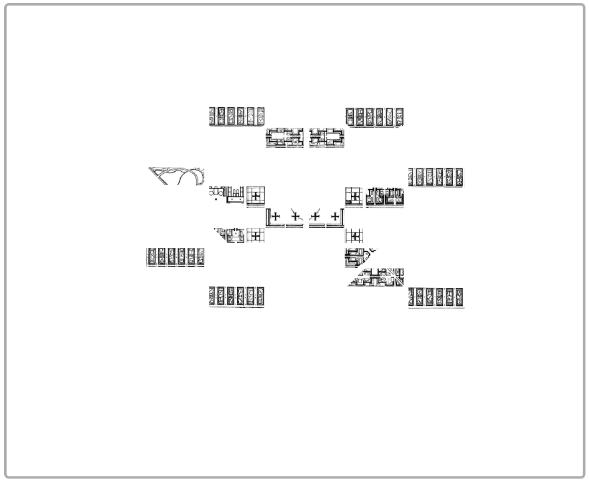

Replicas of replica

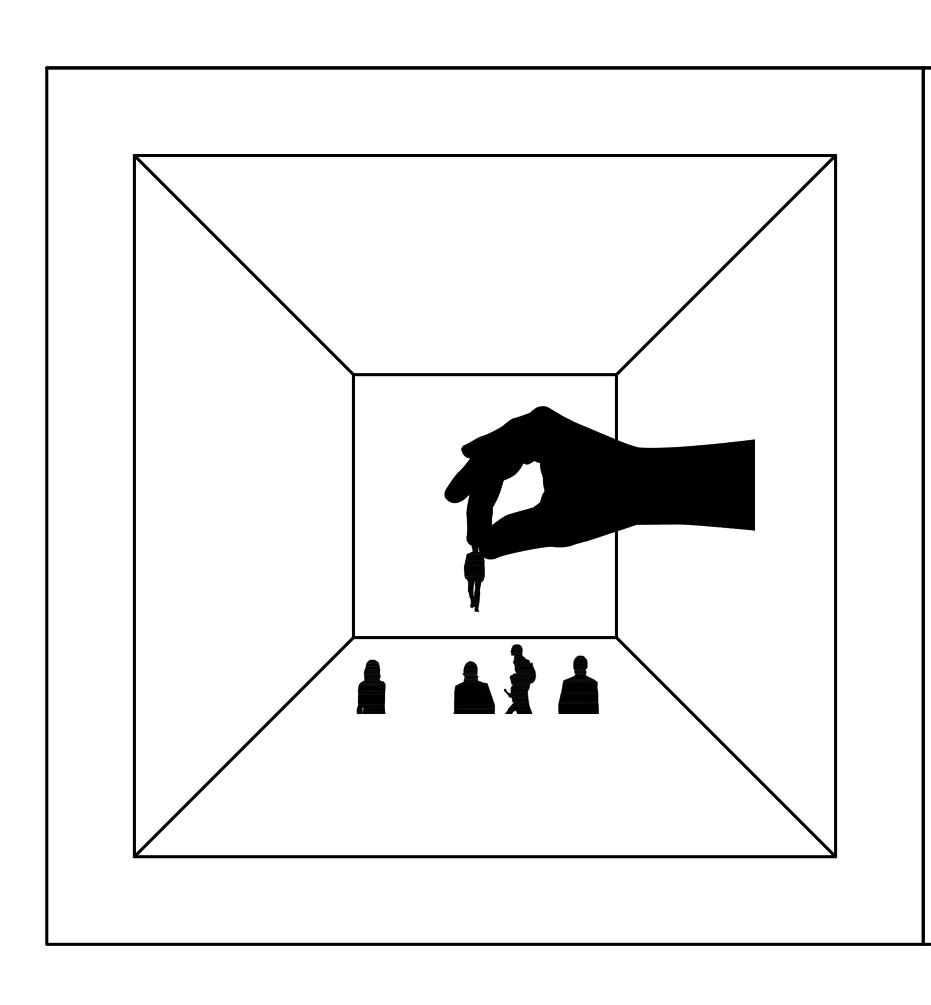

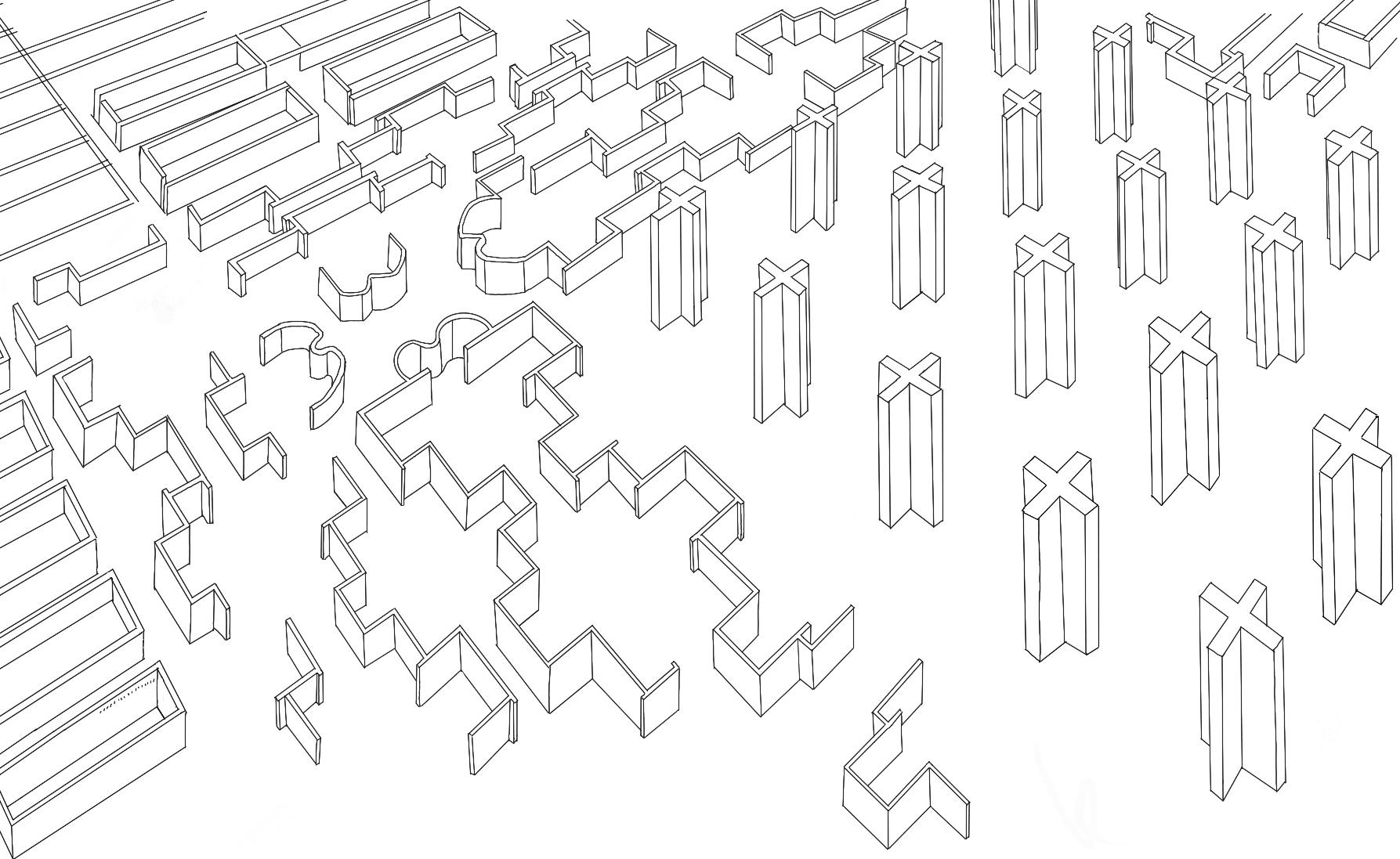

1.Enclosing the subjects

2. identifying the object within the city.

Replicas of replica

"Every architectural work is created on the principle that includes the meaning, and then this work is read like an artefact of the particular meaning. Resources by which the meaning is built primarily, susceptible to transforma tion, as well as routing of understanding (decoding) mes sages carried by a work of architecture, are subject of se miotics and communication theories, which have played a significant role for the architecture and the architect."

Genesis chapter eleven narrates the failed project of build ing a great city and offers the story of the Tower of Babel, the biblical version of the origins of linguistic variability. This story reflects a vivid awareness of the multiplicity of mean ings contained within language and the movement of these meanings about the world (Darroch, 2010). The story of the aborted tower is linked to the varieties of human speech and the dispersion of idioms. The linguistic diversity is analogue to that of the typological objects present in the city. The tower is symbolic and symbolically place at the nucleus of the city. As the object of the organisation, it embodies the function of the city at multiple social, and transportation levels. The vertical development is an allegory to the tower of babel.

“Linguistic variation stands in relation to the city, to its very foundation, and in essence to all its forms, is an ancient idea.”

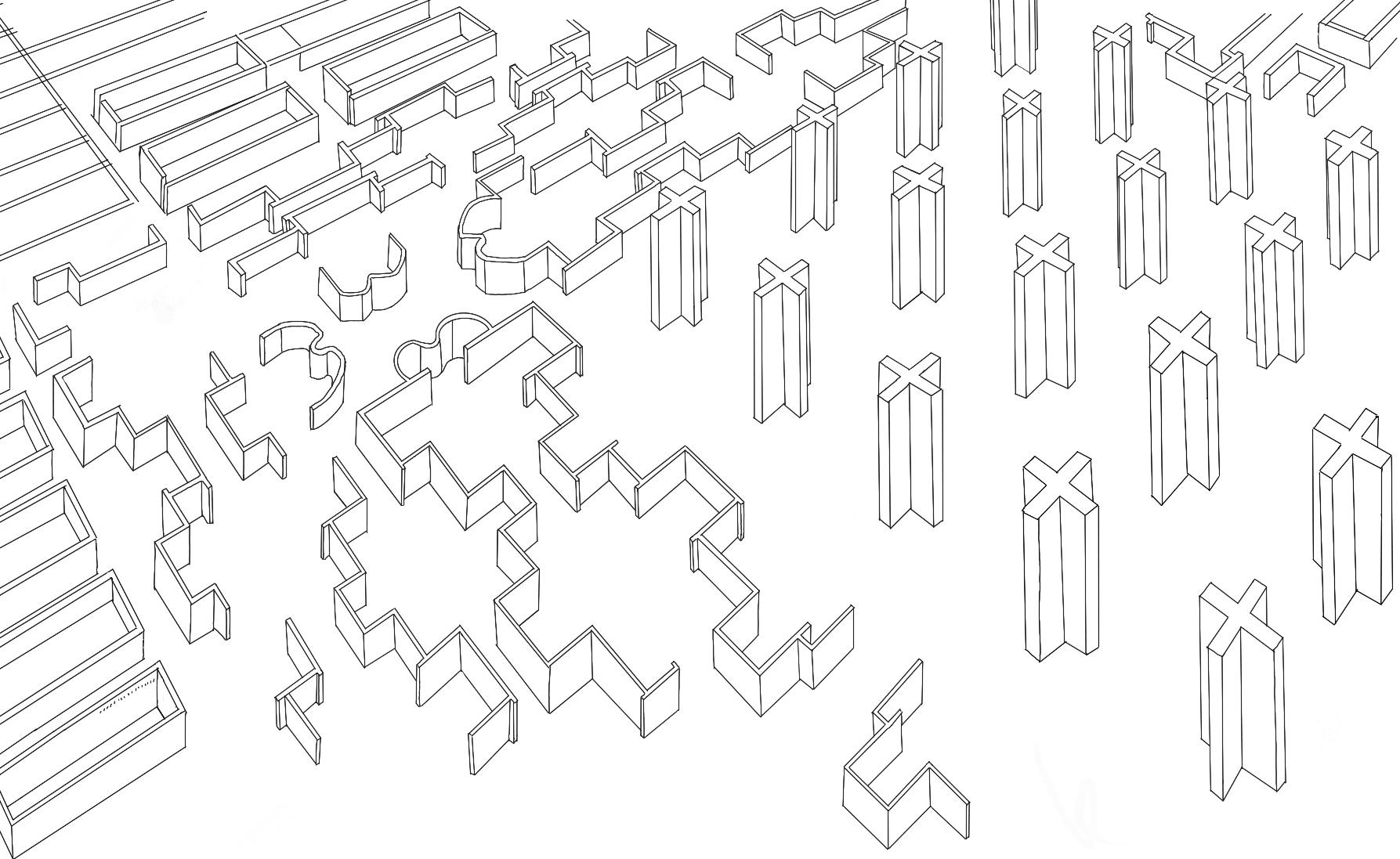

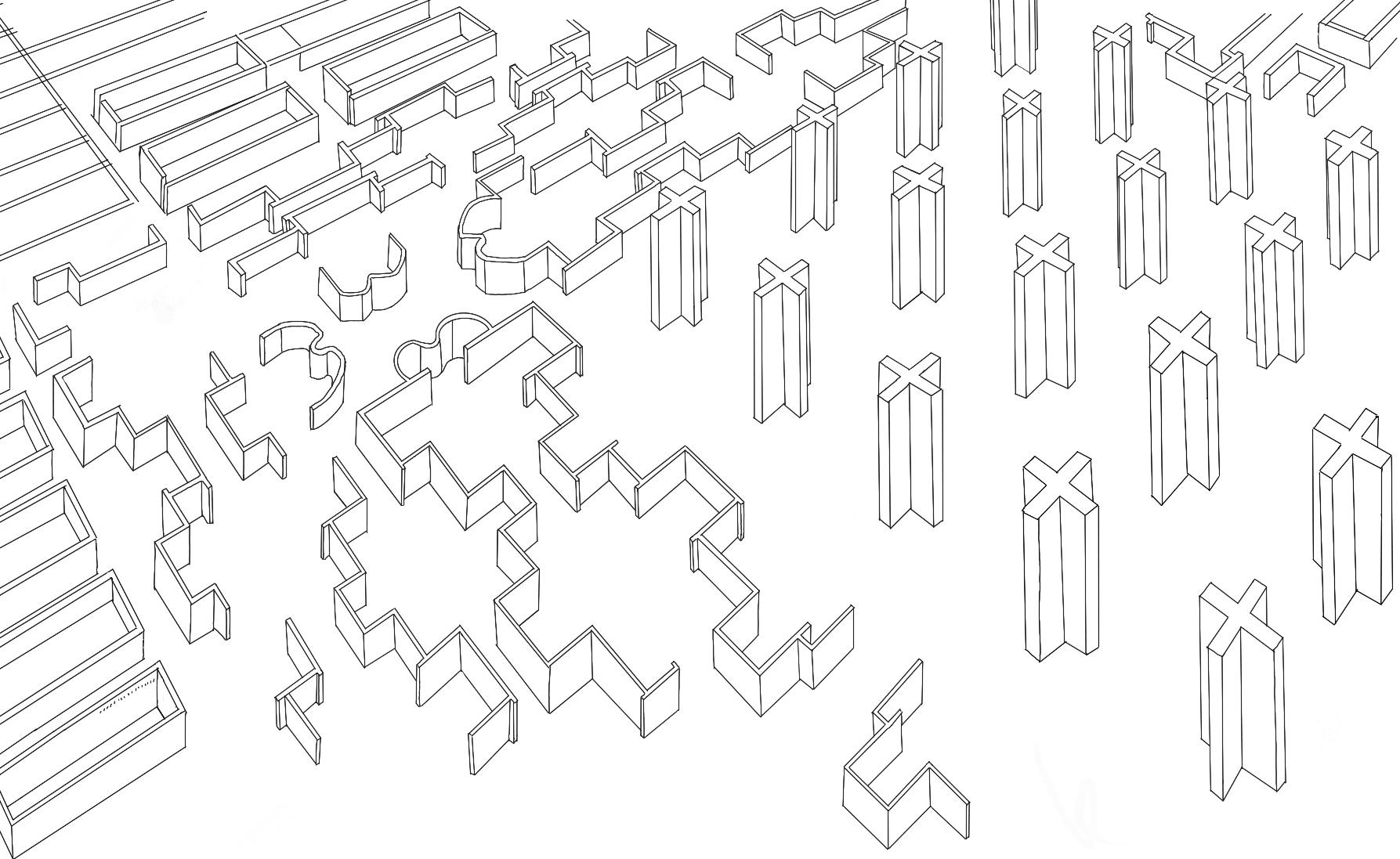

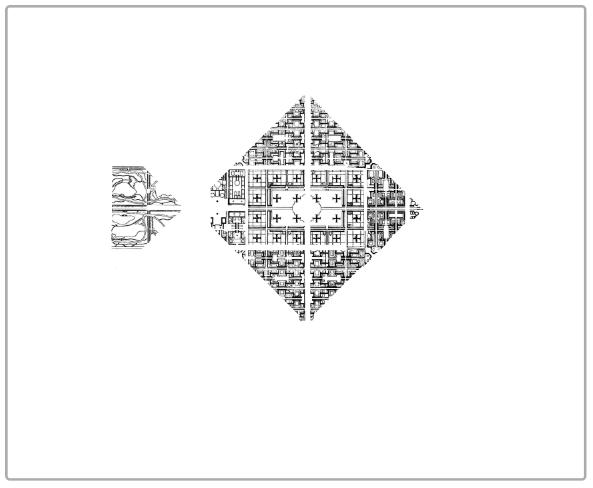

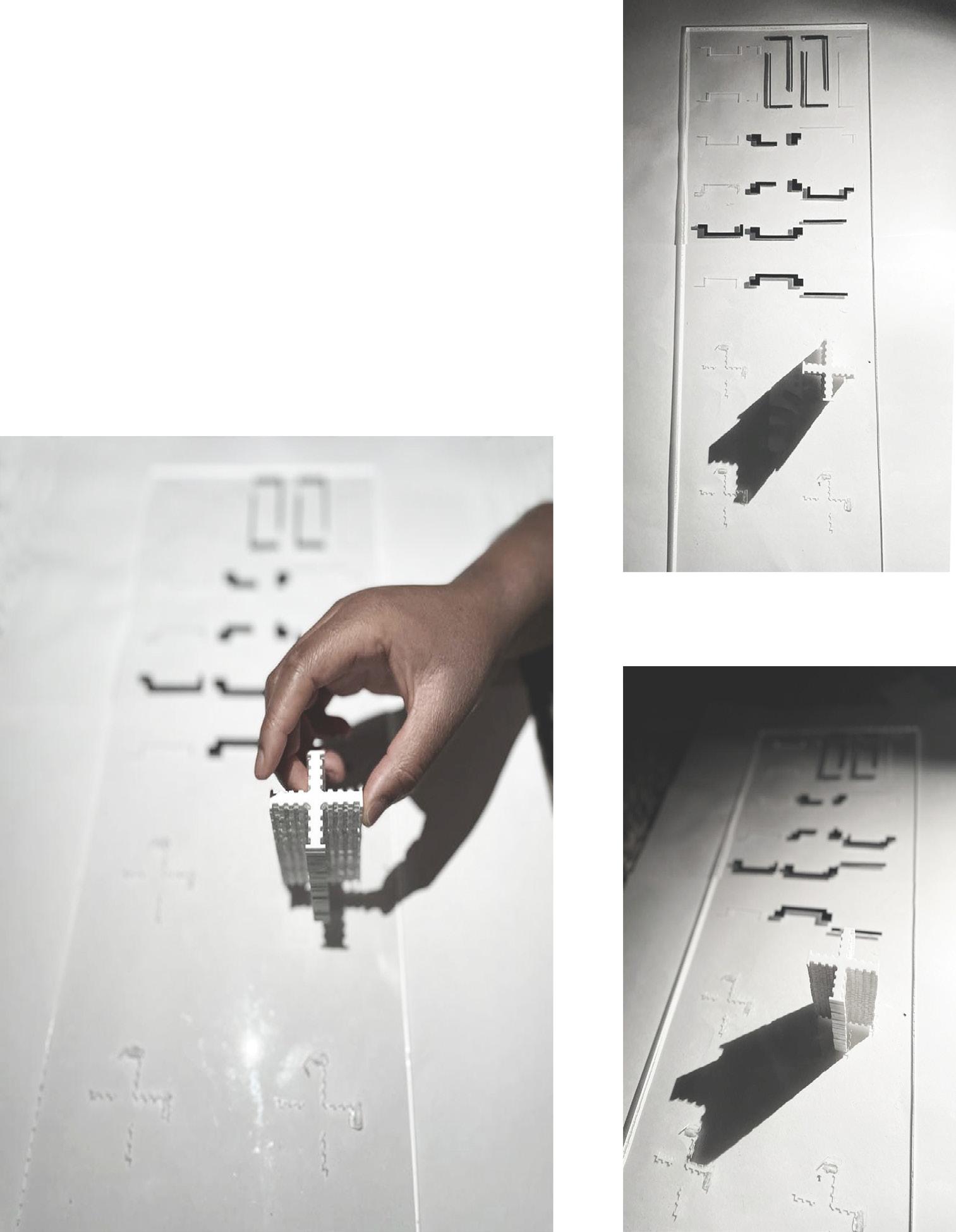

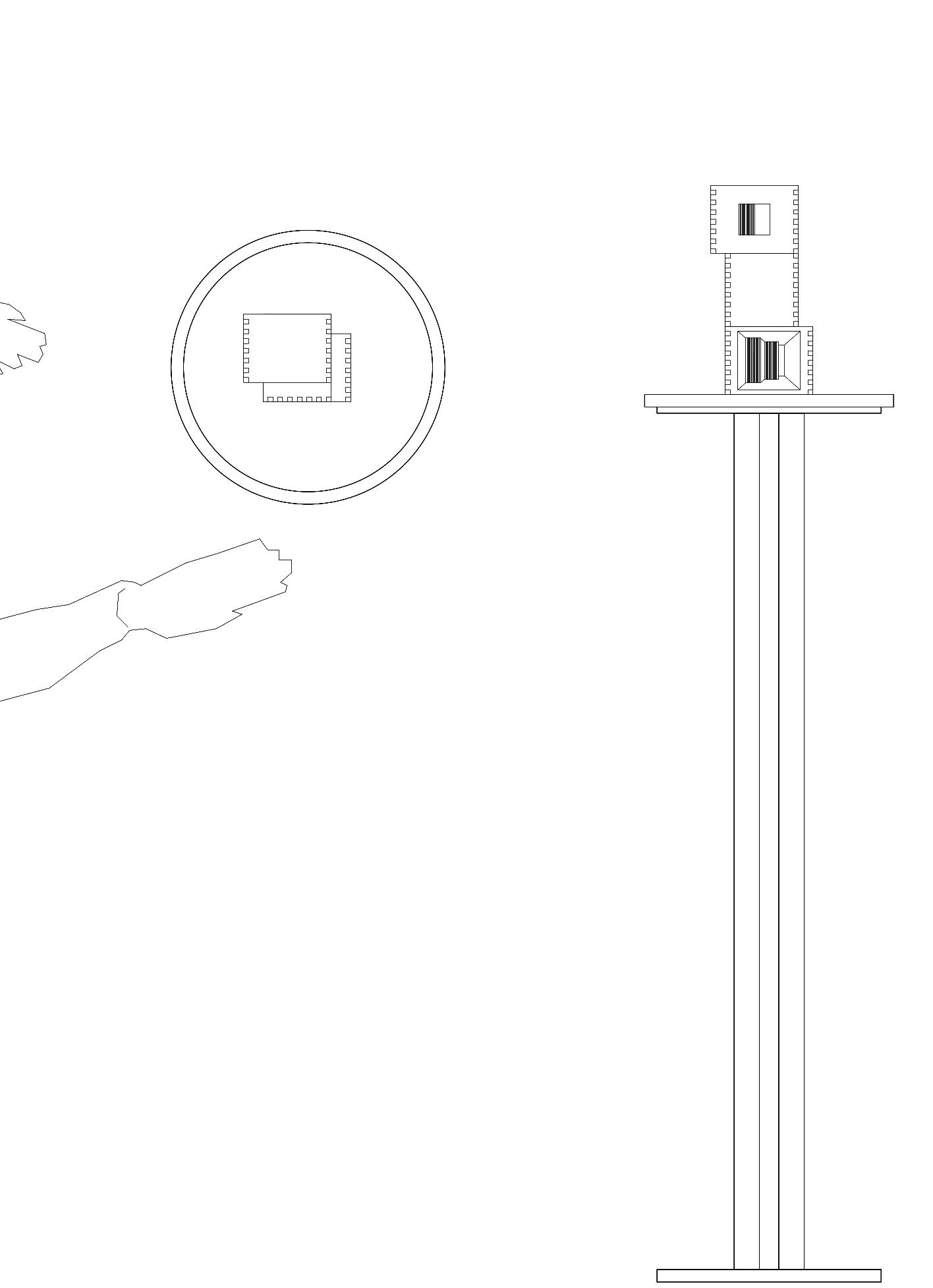

Endeavours towards the construction of a city that could exceed the human conditions have never faded (Dar roch, 2010). Therefore, through the creation of an arte fact, the restrictions correlated to the research of the ideal city will be represented. The object of art is a repli ca of the restricted city. The three fictions will serve as sections plane and will dissect the cross-shape built form to investigate and attest to the modus of Operandi, defi nition, and ultimately the analogical representation.

In reference to the city, the terms restrictive and re stricted are used interchangeably to attest to the in terdependency of force and cause in the discourse of the comprehension of the city and city planning.

FRAGMENTED PERSPECTIVE

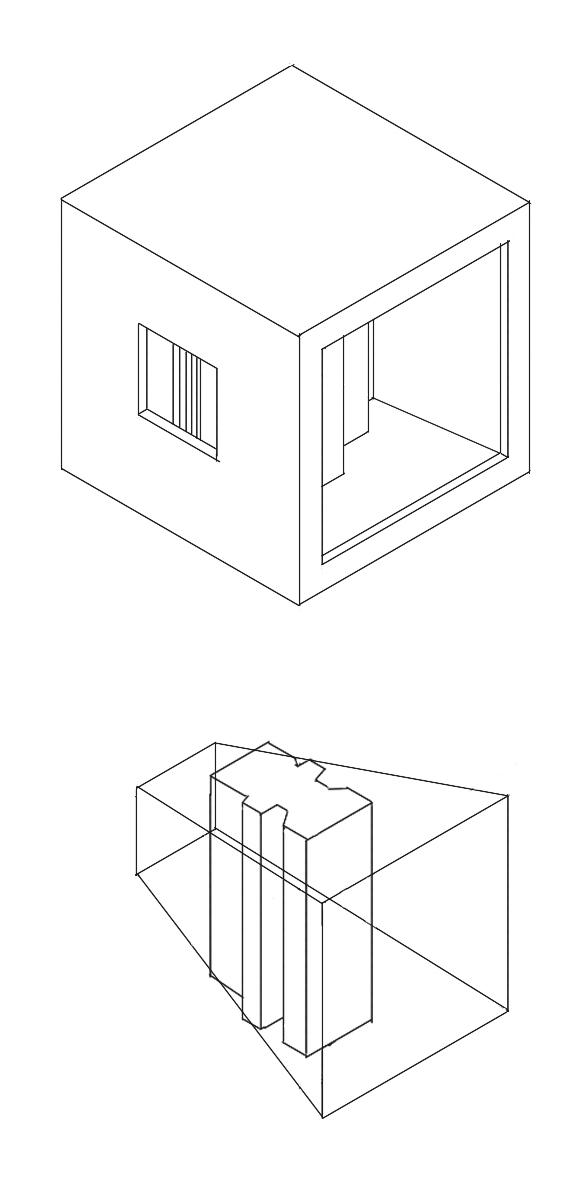

A three-dimensional translation of the restrictive linguistic expression of the tower block.

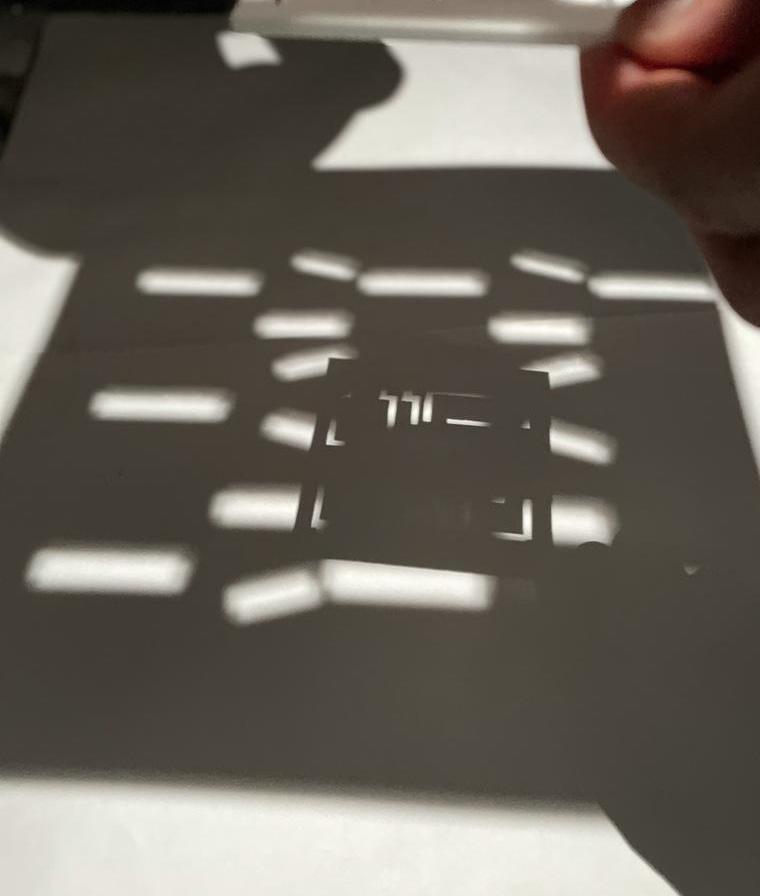

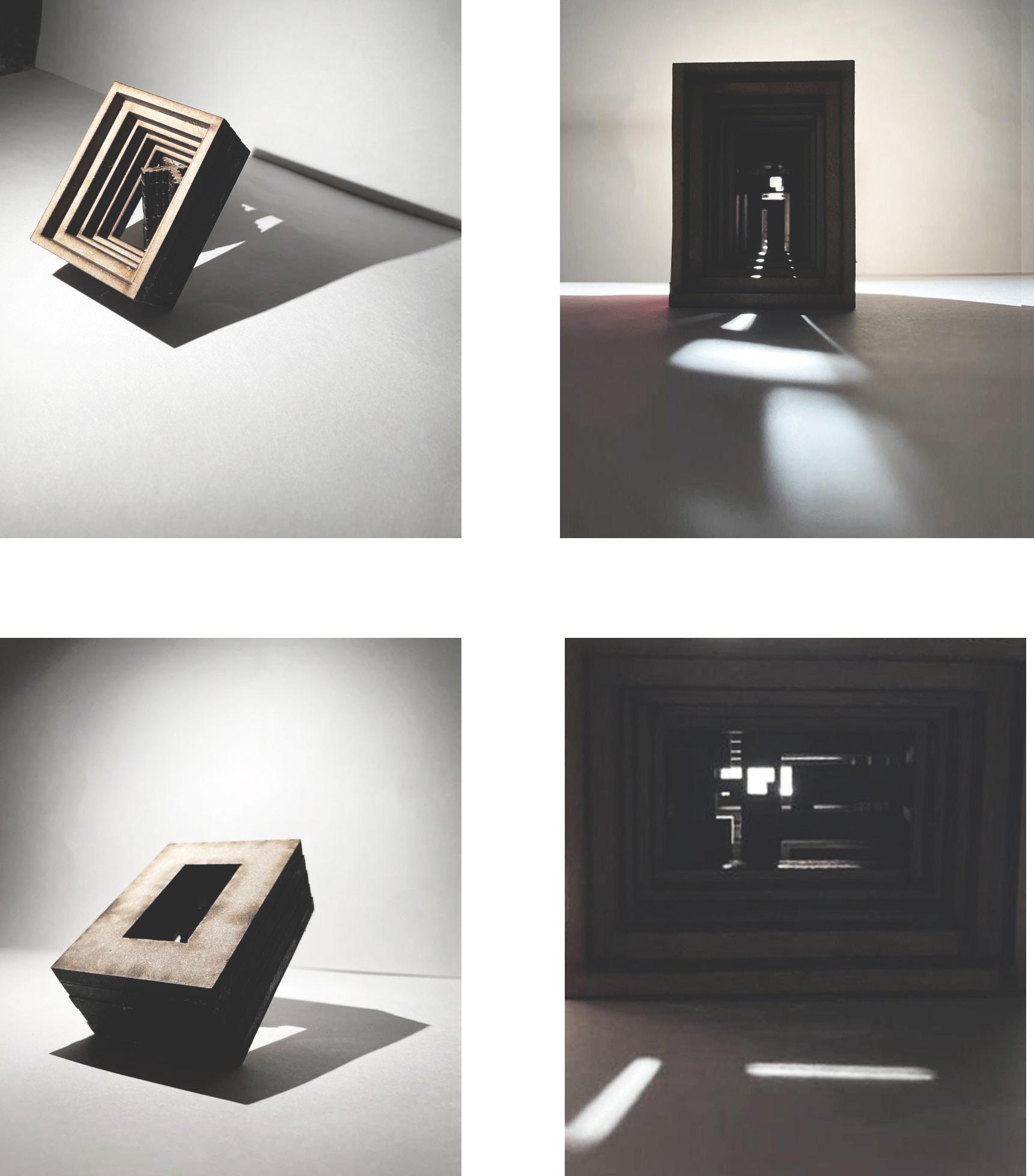

Exploitative models, where the concept of light was synonym of reson . The object of the city are simulcra of the Rational city.

Fictions.

Viewing the city through the fictions of history, reason, representation, is viewing enclosed openings of tangible and intangible past, present and future urban landscape. The City is free from spatial and organisational restrictions when its conceptual form, material, function are perceived as the language of expression of a transitional Architecture. The artifact per se, is enclosed in wooden boxes . The enclosures are metaphor for the fictions present in the restricted city.

A three-dimensional translation of the restrictive linguistic expression of the tower block.

A series of boxes that conceal a fiction of the utopic Restrictive city. The artefacts, explores the notion of representation as memory, the absence of history and absolutism of the rational mind. Like the inhabitants of the restrictive city, the viewer of this ar tefact can only operate within the limits set by the author.

Ville Contemporaine -absence of order.

The end of the beginning and the beginning of the end of fiction.

Following the discussion on the different fictions at play in the rational city and ultimately in the restrictive city, the comprehension of the subject matter at hand can be at tained when all opposing theoretical methods of translation are considered. The antonym de facto is found in Eisenman’s theory of the narratives, which aim is to facilitate the com prehension of architecture in its entirety, liberating from the restrictive formality of the zeitgeist. This process is defined by Eisenman as ‘the end of the beginning and the beginning of the end’ (Eisenman, 1984). It is a cathartic process where the fictions are acknowledged as replica and thus causes the process of dissimulation. An effort towards the compre hension of the organic unity of the city, as the architecture. Through dissimulation, the quest for an origin and its pre meditated end - in the continued research of universality - is repudiated. Specifically, the efforts towards identifying the genesis of a timeless architecture- reason for the ratio nalist- must end, as the search for these beginnings coincide with the origins of replicas (Eisenman, 1984). With the end of the end, what was formerly the process of composition surceases to be a casual strategy, in favour of an open-end ed tactic (Eisenman, 1984). The previously discussed re strictive fictions are present and active unless discredited.

Corbusier’s intent for Ville Contemporaine was envi sioned through reason (Etchells, 1971), organised by reason, and limited by its origin. Whilst Eisenman’s theory liberates the mind from notions of formali ty and facilitates one’s diachronic understanding of the city. The strategy utilised shared some similar ities as they collectively imply reduction or loss of some kind, where one critical assessment of the ur ban is restrictive and restricted, whilst the other is free.

This is not to diminish the modernist contribution; it is to give prominence to the hindrance that fiction may pose to the analytical study of the city. Yet, even a rationalist plan can be reinterpreted and thus gain its freedom, as observed in the case of the Cannaregio project. Inspired by Le Corbus ier’s 1965 Venice Hospital project, Eisenman superimposed the historical site plan on Venice to plot out the project (Eisenman, 2013). Although History is highlighted as one of the fiction, it ought not to be renounced, as Corbusier’s plan was the historical trace utilised for the Venetian project. In an interview for the Architectural Review, the post-modern ist architect shared his Freudian belief: the city is built over traces of history (Eisenman, 2013). Therefore, establishing that the design process can occur when the architect digs -through the unconscious- and encounters such sediments. Proving that ultimately a ‘free’ architectural expression can take the shape of the past without seeking meaning from the past. This is not to say that every stylistic expression ought to be in accordance with another, but it is to recog nise and read each phenomenon as a syntax of narratives, stories to be told. Khan’s Adler house was another prece dent of the syntax of past and present (Eisenman, 2008). The superimposed plans are obtained through a series of analytical drawings where the precedent (the classical ninesquare grid) and the ‘modern objective’ (asymmetry and dynamism) were equally demonstrated. With Adler house, the synthesis of styles was a composition (concerning the structural plans) synonym of architectural text in a dia chronic space. According to Eisenman such results are con ceivable when the art of design no longer depends on or represents the zeitgeist of its time (Eisenman, 1984). Even Rossi recognised with his initial definition of the city as ar chitecture, the importance of recognising architecture as a discipline that has self-determine autonomy (Rossi, 1984).

Concerning the notion of the Architecture of the city (Ros si) and that of Architecture as language, commonalities are shared for the progressive state of the urban and its ob jects. The abstract theoretical ideas, critiqued 19th-centu ry Functionalism, the machine-like ideations, in favour of an open-end diachronic and synchronic study alike of the history and conceptual translation of the urban landscape.

Cannareggio project

Cannareggio project

Progression of the city of fictions or restrictions entails the progression of a futureless future, a present of inventing and an artificial past (Eisenman, 1984). The post-modernists set to reform the stage of ideas and translations by changing the basic tool of architecture, from that of representation to that of communication. The analogy between Architecture and language - is not exclusive to the post-modernist- “it is as old as Vitruvius, as Horace’s comparison between po etry and painting, and Aristotle’s poetics” (Vasilski, 2012). In the chapter ‘This will kill that’ of the book Notre Dame in Paris, Victor Hugo reiterates that architecture has and will always be a prominent bearer of every human thought, and symbol of that which is spiritual and social (Hugo, 1985). Re search upon the relationship of architecture and language foisted at the beginning copious queries. To attest to the validity of this ideology, the architectural method of con veying meaning, its ability to speak, and its definition were all attributes that need to be discussed (Vasilski, 2012). The first logical definition of the analogy of language and ar chitecture was found in the shared intrinsic semiotic and semantic qualities. A new distinction, therefore, must take place. One that in relevance to verbal methods of commu nication posed arbitrary accuracy to the meaning of archi tecture (as defined by Haideger ). Therefore, when defining architecture as a linguistic construct, written text is most conducive as its content is comprehensible to the collective (semantics) and is profitable for educational intentions.

Another analogy is formulated by Vasilski regarding the ar chetypal building elements (material, ornaments, structural components etc) and linguistic fundamentals (words, vo cabulary, grammar, rhetoric etc). “Each architectural object should tell us something,” Botero and Venturi alike, over thrown the organicist ideology of the supremacy of func tion, placing the architectural intentions to communicate top rank. Despite the ‘universal’ post-modern contribution towards the rampant idea of the “talking architecture”, the application of the latter differed. In relation to reading the architecture of the city, Bruno Zevi produced seven codes (semiotic) that provided a liberal interpretation of the works of modern architects. The concepts of codes were then used to abstract the meaning, and read the content and functions of the analytical object. Others, like Tafuri, believed that architecture had the right to “meditate and to express the one (the city in its entirety) and only itself”, thus emphasizing the possibility of a language of silence (as in the case of Minimalism). Oppositely, Bernard Tschumi’s work defined Architecture as a cultural facility, where the reading of the city occurred through essential socio-historical forms of language. Others of the likes of Lefebvre approached the subject at hand antithetically, as the space was envi sioned and translated by virtue of linguistics and seman tics. Ultimately, the idea – that is of decoding past, present and conceptual forms- remained unmutated (Vasilski, 2012).

Though the focus of the research and results differs, Tschumi’s philosophical translation of architecture and Le febvre’s semiotic dimension are comparable. Unlike the re search of the fictional city, the strategy utilised towards the understanding of the vocabulary of architecture and the city is open-ended. The initial idea and aim are therefore the same and oriented in relation to the comprehension of reali ty. Individuality per se is rampant, humanism is re-proposed as the architect navigates the narratives of architecture.

Where rationalist have speculated that to free the city is to organise it, upon further investigation true liber ation of the utopic city and the methods of investiga tion happen when every component of the city is con sidered, and preconceived notions on the strategy of analyse and translation of the built forms are removed.

The restricted city is a “no place” city, a conceptual thought, a sum of abstract simulated reality. The expression of the restricted architecture is a simulation of parts, devoid of meaning, or accurate historical context and unable to rep resent the truth. An imitation of other formal architec tural vocabulary is the utopia’s mere way of expression. Ultimately, according to Eisenman, texts are as import ant as the building project. Yet, in the discourse of archi tecture, logic, and language: drawing is a form of writ ing, and a form of reading what is it written. There is not any difference. To Eisenman drawing is not making pretty things or making representations. It is not rep resenting anything; it is the incarnation of the thing. It is the realization of the concept. This theory will open into Eisenman’s formalism and into the vast discussion of aesthetics in relation to the form (Eisenman, 1986).

Axonometric drawing exploring possible sectional plane .

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Darroch, M., 2010. “Language in the City, Lan guage of the City.” Circulation and the City: Es says on Mobility and Urban Culture.. s.l.:Eds. Eaton, R., 2002. “Introduction” in Ideal Cities: Utopianism ad the (un)built environment. London: Thames and Hudson. Eisenman, P., 1984. The End of the Classical: The End of the Beginning, the End of the End. In: Perspecta, ed. The End of the Classical. 21 ed. s.l.:The MIT press, pp. 155-73. Eisenman, P., 1986. An Architecture of Absence. s.l.: Architectural Association (Great Britain). Eisenman, P., 2008. From Plaid Grid to Diachronic Space, Louis I. Kahn, Adler House and DeVore House. In: A. Lourie, ed. Ten Canonical Buildings: 1950-2000. New York: Rizzoli, pp. 102-127. Eisenman, P., 2013. Interview- Pe ter Eisenman [Interview] (26 April 2013). Etchells, L. C. a. F., 1971. In: The city of tomorrow and its planning. London: Architectural Press, pp. 11-285. Graafland, A., 1996. Architectur al Bodies. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers . Houdrouge, J., 2018. An Ideal City?. s.l.:s.n. Hugo, V., 1985. This will kill that. In: No tre dame de Paris. s.l.:https://www.gutenberg. org/files/2610/2610-h/2610-h.htm, pp. 192-193.

Mumford, L., 1969. “Village and Stronghold” in The City in History: Its. New York: A Harvest Book. Oswald Mathias Ungers and Rem Koolhaas with Peter Riemann, H. K. a. A. O., n.d. The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Archipel ago. Journal of Landscape Architecture, Volume 9, pp. 18-37. Rossi, A., 1984. The Architecture of the City. s.l.:MIT press. Tafuri, M., 1969. Toward a Critique of Ar chitectural Ideology. s.l.:Contropiano 1. Vasilski, D., 2012. Minimalism in Architec ture: Architecture as a languange of its iden tity. Belgrade: University Union Nikola Tesla.

Work cited

Colquhoun, A., 2002 . Organicism versus Classicism: Chicago 1890-1910. In: Modern architecture. s.l.:OUP Oxford, pp. 35-57. Corbusier, L., 1967. The Radiant City. New York: Orion Press. Dahabreh, S. M., 2014. Intellectual Form: Understanding Ar chitecture as a Logical. Amman: Research India Publications.