2 minute read

Architecture as languange

5| ARCHITECTURE AS A LANGUAGE

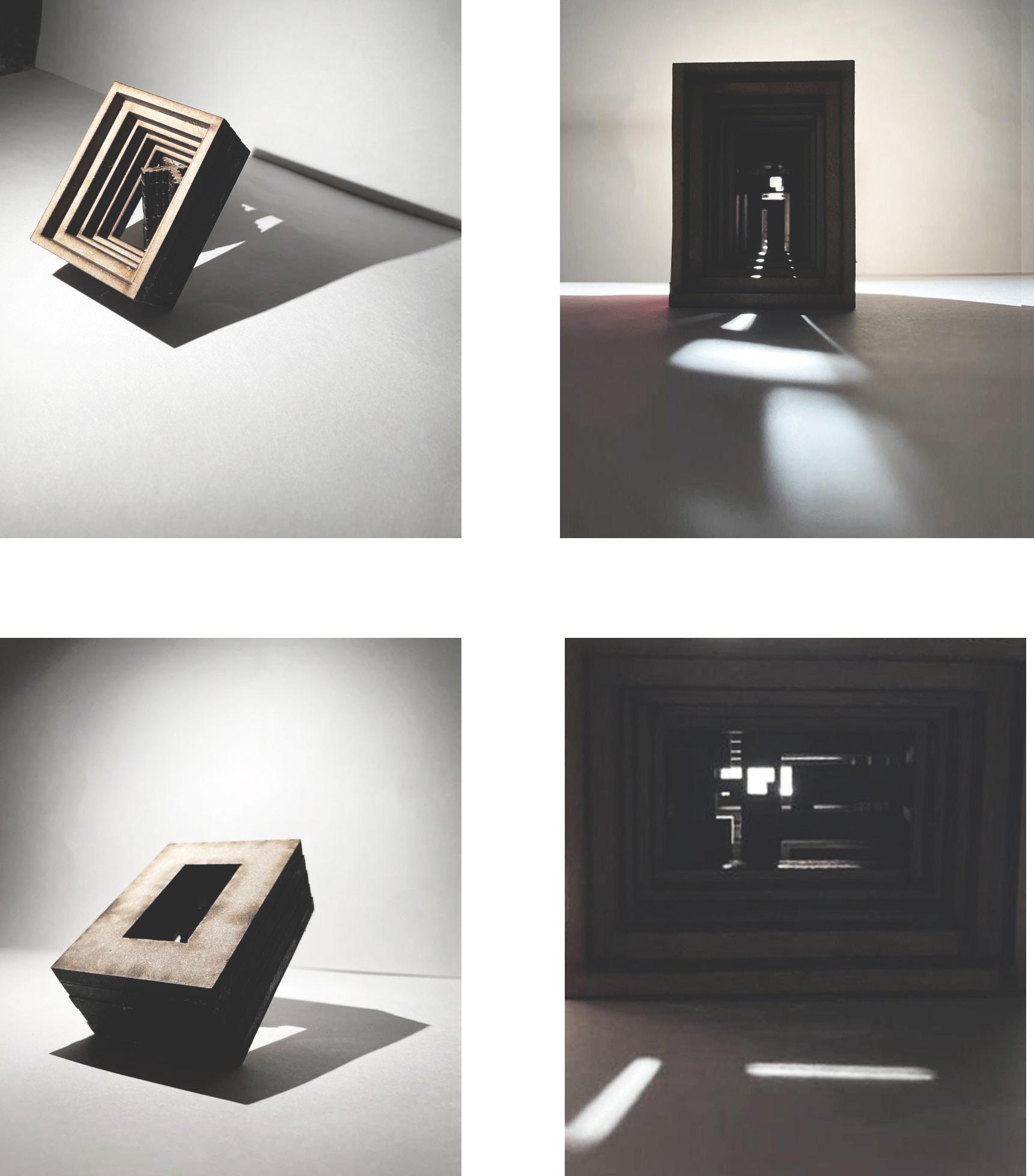

Progression of the city of fictions or restrictions entails the progression of a futureless future, a present of inventing and an artificial past (Eisenman, 1984). The post-modernists set to reform the stage of ideas and translations by changing the basic tool of architecture, from that of representation to that of communication. The analogy between Architecture and language - is not exclusive to the post-modernist- “it is as old as Vitruvius, as Horace’s comparison between poetry and painting, and Aristotle’s poetics” (Vasilski, 2012). In the chapter ‘This will kill that’ of the book Notre Dame in Paris, Victor Hugo reiterates that architecture has and will always be a prominent bearer of every human thought, and symbol of that which is spiritual and social (Hugo, 1985). Research upon the relationship of architecture and language foisted at the beginning copious queries. To attest to the validity of this ideology, the architectural method of conveying meaning, its ability to speak, and its definition were all attributes that need to be discussed (Vasilski, 2012). The first logical definition of the analogy of language and architecture was found in the shared intrinsic semiotic and semantic qualities. A new distinction, therefore, must take place. One that in relevance to verbal methods of communication posed arbitrary accuracy to the meaning of architecture (as defined by Haideger ). Therefore, when defining architecture as a linguistic construct, written text is most conducive as its content is comprehensible to the collective (semantics) and is profitable for educational intentions. Another analogy is formulated by Vasilski regarding the archetypal building elements (material, ornaments, structural components etc) and linguistic fundamentals (words, vocabulary, grammar, rhetoric etc). “Each architectural object should tell us something,” Botero and Venturi alike, overthrown the organicist ideology of the supremacy of function, placing the architectural intentions to communicate top rank. Despite the ‘universal’ post-modern contribution towards the rampant idea of the “talking architecture”, the application of the latter differed. In relation to reading the architecture of the city, Bruno Zevi produced seven codes (semiotic) that provided a liberal interpretation of the works of modern architects. The concepts of codes were then used to abstract the meaning, and read the content and functions of the analytical object. Others, like Tafuri, believed that architecture had the right to “meditate and to express the one (the city in its entirety) and only itself”, thus emphasizing the possibility of a language of silence (as in the case of Minimalism). Oppositely, Bernard Tschumi’s work defined Architecture as a cultural facility, where the reading of the city occurred through essential socio-historical forms of language. Others of the likes of Lefebvre approached the subject at hand antithetically, as the space was envisioned and translated by virtue of linguistics and semantics. Ultimately, the idea – that is of decoding past, present and conceptual forms- remained unmutated (Vasilski, 2012).

Advertisement

Though the focus of the research and results differs, Tschumi’s philosophical translation of architecture and Lefebvre’s semiotic dimension are comparable. Unlike the research of the fictional city, the strategy utilised towards the understanding of the vocabulary of architecture and the city is open-ended. The initial idea and aim are therefore the same and oriented in relation to the comprehension of reality. Individuality per se is rampant, humanism is re-proposed as the architect navigates the narratives of architecture.