2 minute read

introduction

1| UNDERSTANDING THE CITY AS A LINGUISTIC CONSTRUCT

Introduction

Advertisement

In the introduction of The City in History, Lewis Mumford asked: “What is a city? How did it come into existence? […] What purposes does it fulfil?” (Mumford, 1969) From, Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), Le Corbusier’s Contemporary City for Three Million inhabitants (1922), The city in the city manifesto (1977) or Aldo Rossi’s Architecture of the city (1984), the city has always been an “idealized reality for the projection of a society’s ideology” (Mumford, 1969). For More, it is an egalitarian city, one shaped and functioning like a machine governed by reason for Le Corbusier. A city composed of adaptable polycentric urban landscapes to Ungers and Koolhaas (Oswald Mathias Ungers and Rem Koolhaas with Peter Riemann, n.d.). and, an architectural typological reality of objects subjugated to perpetual transformation for Rossi (Rossi, 1984). Across theoretical literature, the ideal modern city –the one of a new order, was a proposed scientific effort, one that tasked the architect to find rational solutions to contemporary urban queries.

With the advent of the industrial society- in the late nineteenth century, modernism attempted to simulate and solve realism through reason (Eisenman, 1984). Therefore, implying that the research for universal rational values could not be attained through the representation of previously valued architectural expression (Eisenman, 1984). Rather, it needed to simulate the meaning of truth, thus reasserting that rational architecture was not just a simulation of reality but also the organisation of the latter. Despite the articulated rupture in both ideology and style associated with Modernity; according to Eisenman the three fictions (reason, representation, history) have never been questioned and therefore remain intact. This is to say that architecture since the mid-fifteenth century aspired to be an epitome of the classic, of that which is timeless (through the fiction of history), meaningful (through the fiction of representation), and true (rational). Hence, the concept that personifies the rational mind as the agent of the production of timeless architecture is unenforceable. With Post-modernism came the recognition of Architecture as a linguistic construct. Ultimately, the comprehension of the latter determines the limits, organisation, stylistic manifestation, and scales of the production of urban environments. Ergo, restrictions -in the conceptual and tangible development of the urban landscape - occur upon the proclaimed supremacy of a fiction (reason for the rationalist) in the continued discourse of architecture.

As highlighted in the abstract, restrictive practices are not sorely exclusive to the spatial manifestations, nor the volumetric elements of design - they are transcendental to the real limitations that take place in the rational mind. The priorly stated is the point of rupture between modernists the likes of Le Corbusier and post-modernist architects, such as Eisenman. To facilitate the discussion of the subject matter, the essay has been structured into two parts: the Rational city (an exploration of Ville Contemporaine, the rational mind, and its fiction) and the notion of Architecture as a language. One will reveal the concrete and abstract limitations of modern city planning, whilst the other will liberate the city. Successful comprehension of the notion of a Restrictive city commences with the analysis of the Rational city: its theories, extremism, historical context and need for order.

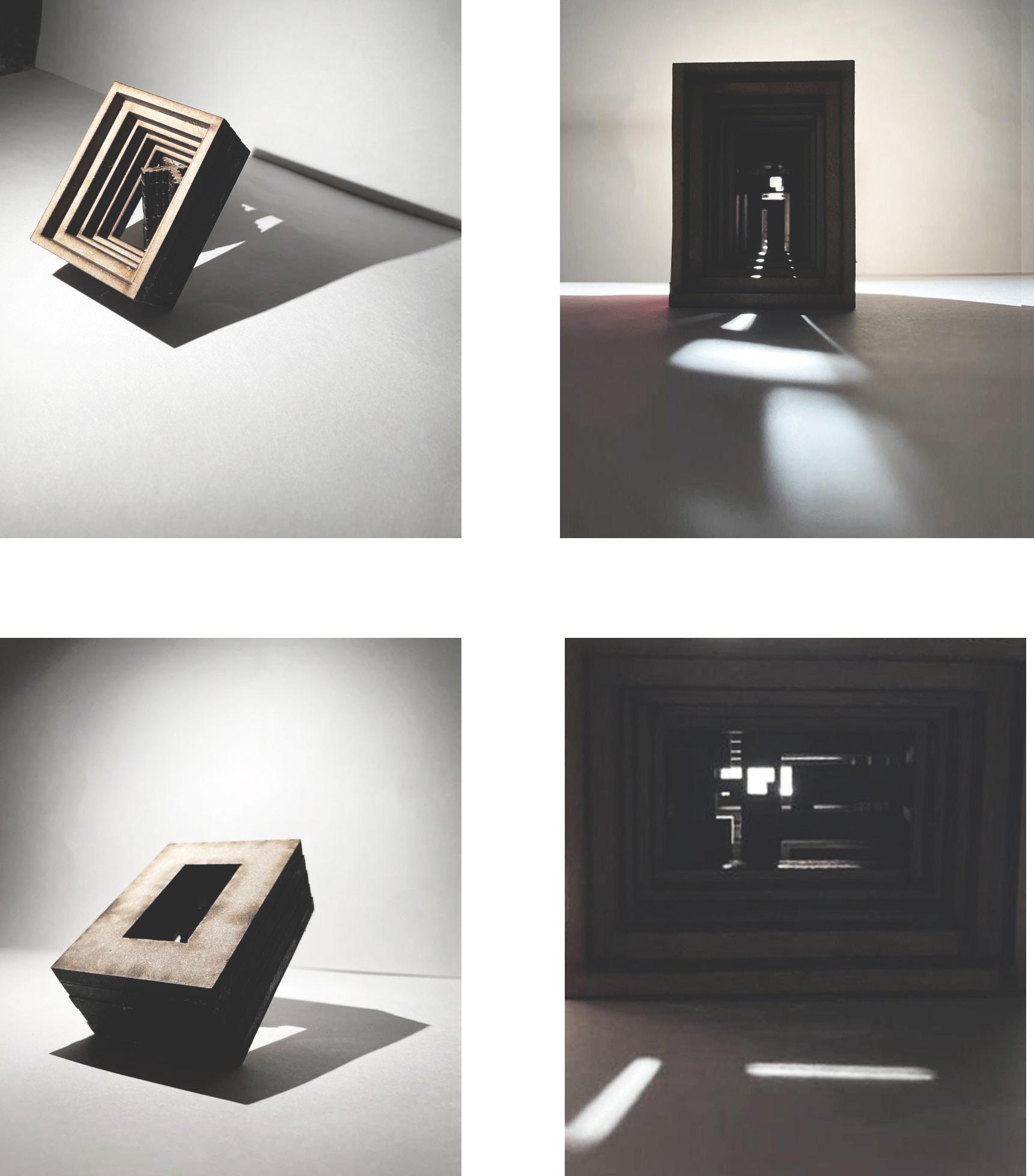

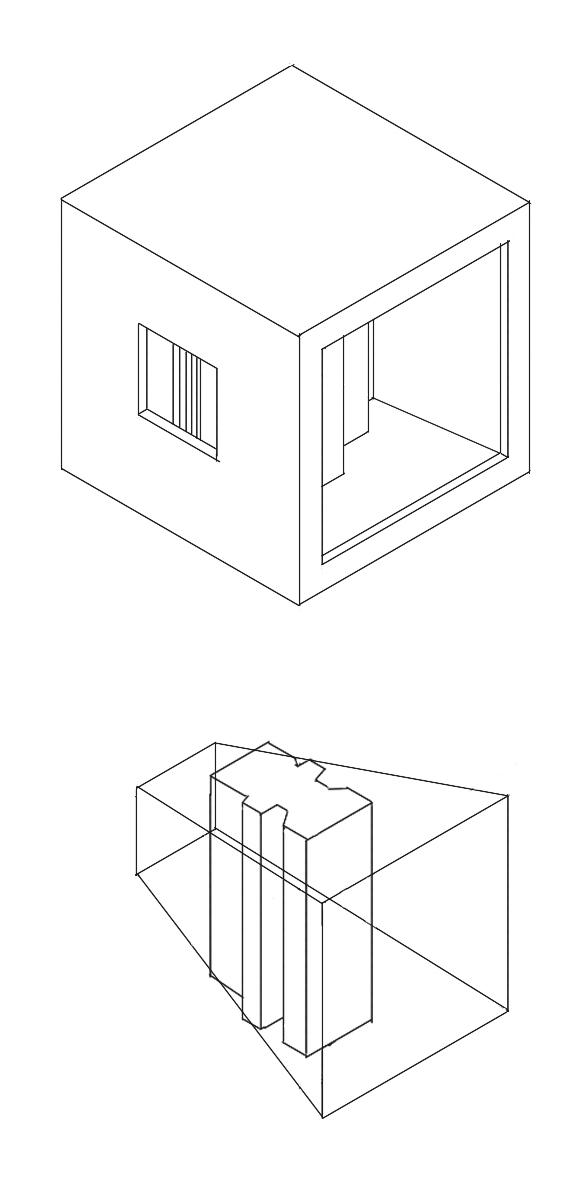

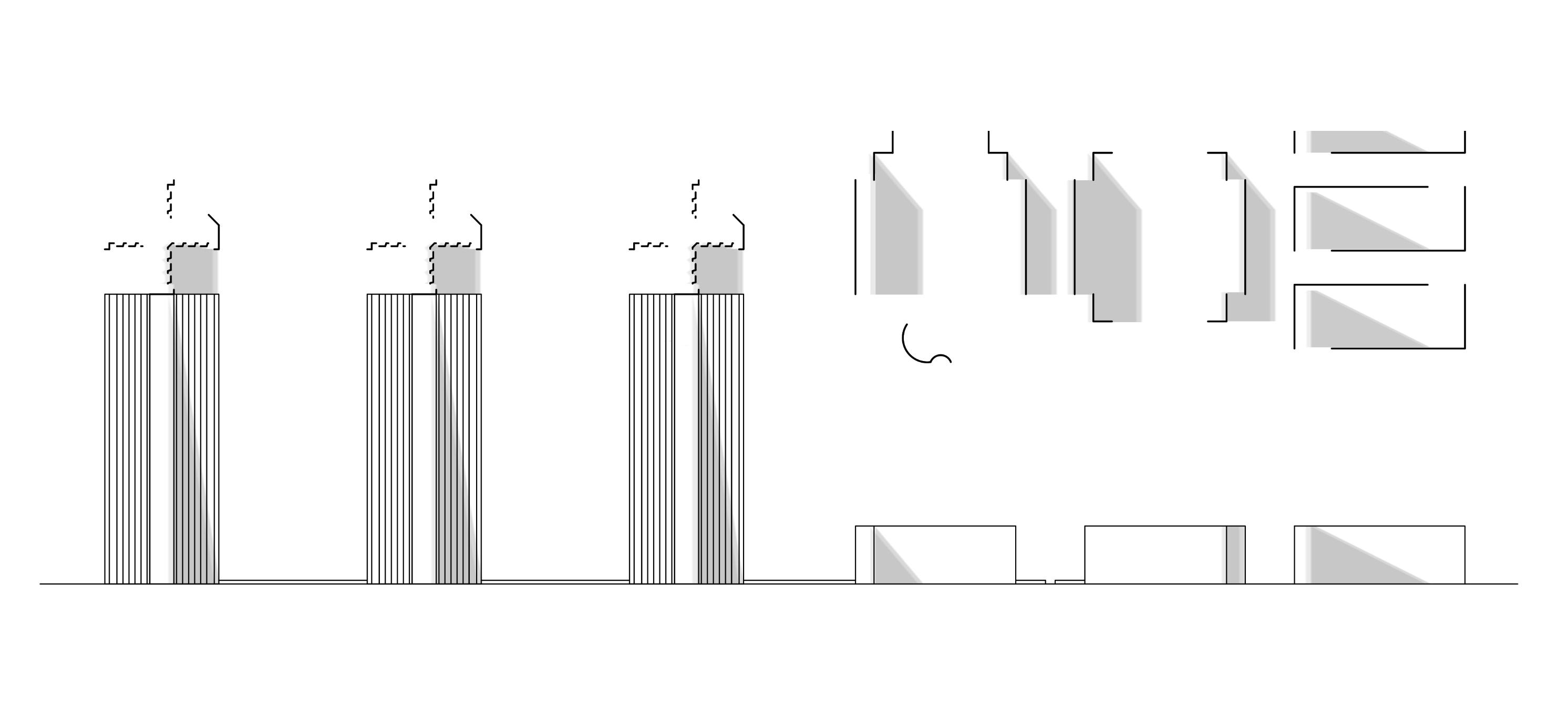

Extrapolating order through line drawings.

PART 1

Ville Contemporaine -absence of order.