INTRODUCTION The Emergency Department (ED) is the principal front-line service for unplanned acute care. Services are profoundly affected by changes in population health, demographics, access and transportation. Record-breaking numbers of ED presentations are regularly reported across hospitals in Australia. In NSW hospitals, almost 700,000 ED presentations were recorded in the last quarter of 2016, up almost 40% from the previous year (Aubusson, 2017). As emergency care environments are complex and highly specialised, the planning and design of these spaces requires current and upto-date knowledge of research, trends and data. Despite constant pressure on operational capacity across the entire health network, service delivery cannot be compromised. Emergency medicine is a relatively new specialism. This speciality emerged when ‘emergency rooms’ located within clinics and hospitals grew to become entire departments with dedicated nursing and specialist training (AAFP, 2017). It was recognised by the American Board of Medical Specialities in 1979, and in 1984 the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine was founded. The way in which emergency care is delivered is constantly being adjusted and developed, with new models of care emerging around the world. Emergency care is delivered in a wide range of environments, from hospitals, to emergency transports, in urban

4

ENVISION WELLNESS Acute Health Design

We need to question how well we care for people in hospital waiting rooms, as these patients are undiagnosed, untreated and vulnerable. (Sparkes, 2011).

areas and in remote locations. While the hospital ED is at the epicentre of the delivery network, acute patient care must be supported in all possible contexts. Delivering high quality acute care for undifferentiated and unscheduled patients is complex because time and space pressures can limit opportunities to support a patient-centred approach. Often, the focus of EDs is improving access, efficiency and patient flow. The built environment has the potential to encourage a more personal approach to care by providing positive stimuli and operational flexibility. For patients, emergency environments can be traumatic and disorientating, and for staff they can be stressful and potentially dangerous workplaces. This paper seeks to explore some current trends in the planning and design of EDs which help facilitate a high quality person-centred care, as well as safe and efficient staff-centred workplaces.

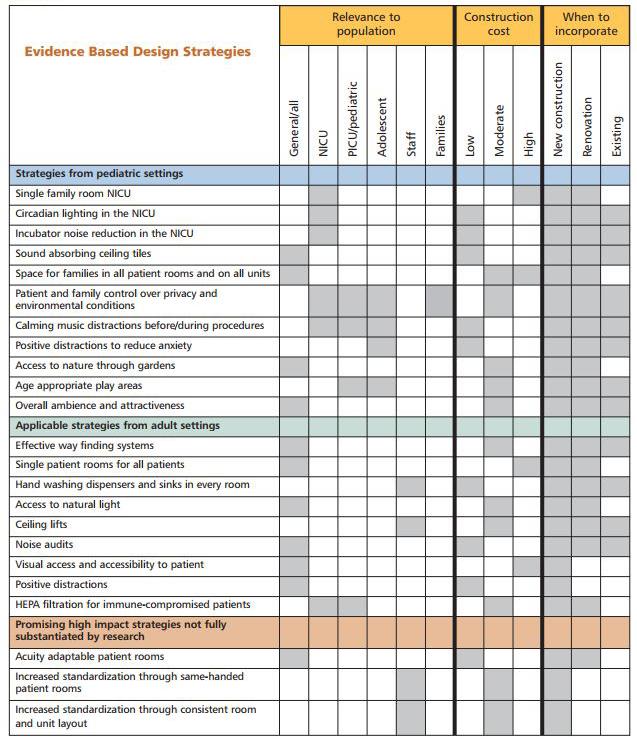

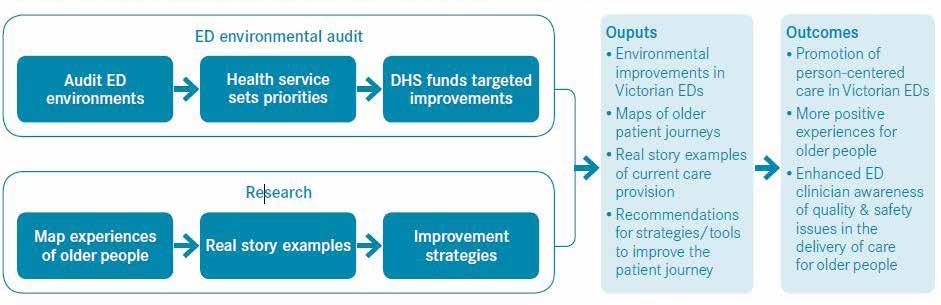

01_ Children & Adolescents In 2004, following a survey of 197 Australian Hospitals, the Association for the Wellbeing of Children in Healthcare (AWCH, 2010, p7) identified EDs as an area within hospitals that needed to be made more child and youth friendly, especially in general hospitals. AWCH research indicated time spent waiting, overcrowding, and lack of supervised play contributed to negative perception of EDs on patients and families. Case Study 01 investigates the experience of children and adolescents in emergency environments and hospital settings in general. The National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions (2008) report outlines a number of design strategies which can guide the design of paediatric EDs. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne provides a striking example of acute spaces designed for interaction and stimulation for children and adults. 02_ Older People Older people make up a large proportion of ED presentations and are more likely to have longer lengths of stay in emergency. This can amplify overcrowding and access block. Furthermore, older people often suffer from cognitive impairment, physical disability and multiple medical conditions. Providing patient centred care for older people therefore requires a specialised approach to avoid missed diagnoses, prevent complications associated with