5 minute read

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Emergency Department (ED) is the principal front-line service for unplanned acute care. Services are profoundly affected by changes in population health, demographics, access and transportation. Record-breaking numbers of ED presentations are regularly reported across hospitals in Australia. In NSW hospitals, almost 700,000 ED presentations were recorded in the last quarter of 2016, up almost 40% from the previous year (Aubusson, 2017). As emergency care environments are complex and highly specialised, the planning and design of these spaces requires current and upto-date knowledge of research, trends and data. Despite constant pressure on operational capacity across the entire health network, service delivery cannot be compromised.

Advertisement

Emergency medicine is a relatively new specialism. This speciality emerged when ‘emergency rooms’ located within clinics and hospitals grew to become entire departments with dedicated nursing and specialist training (AAFP, 2017). It was recognised by the American Board of Medical Specialities in 1979, and in 1984 the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine was founded.

The way in which emergency care is delivered is constantly being adjusted and developed, with new models of care emerging around the world. Emergency care is delivered in a wide range of environments, from hospitals, to emergency transports, in urban

We need to question how well we care for people in hospital waiting rooms, as these patients are undiagnosed, untreated and vulnerable. (Sparkes, 2011).

areas and in remote locations. While the hospital ED is at the epicentre of the delivery network, acute patient care must be supported in all possible contexts.

Delivering high quality acute care for undifferentiated and unscheduled patients is complex because time and space pressures can limit opportunities to support a patient-centred approach. Often, the focus of EDs is improving access, efficiency and patient flow. The built environment has the potential to encourage a more personal approach to care by providing positive stimuli and operational flexibility. For patients, emergency environments can be traumatic and disorientating, and for staff they can be stressful and potentially dangerous workplaces. This paper seeks to explore some current trends in the planning and design of EDs which help facilitate a high quality person-centred care, as well as safe and efficient staff-centred workplaces. 01_ Children & Adolescents

In 2004, following a survey of 197 Australian Hospitals, the Association for the Wellbeing of Children in Healthcare (AWCH, 2010, p7) identified EDs as an area within hospitals that needed to be made more child and youth friendly, especially in general hospitals. AWCH research indicated time spent waiting, overcrowding, and lack of supervised play contributed to negative perception of EDs on patients and families.

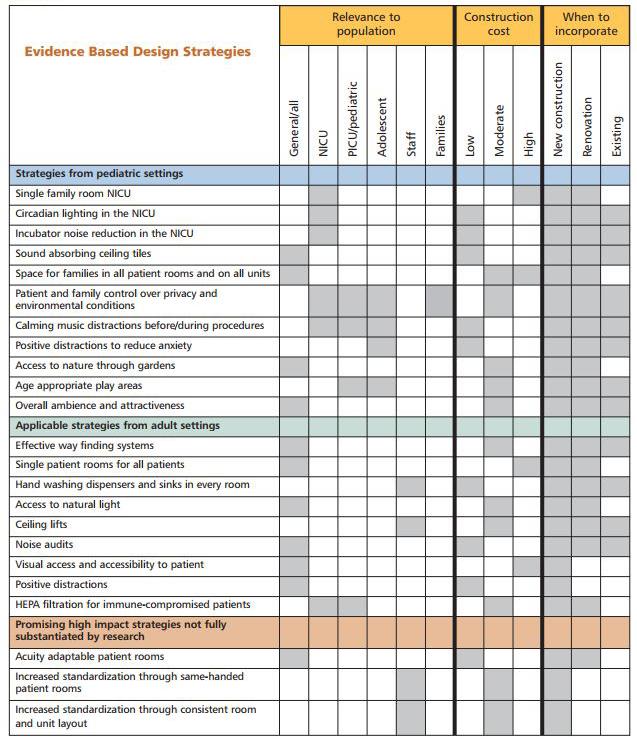

Case Study 01 investigates the experience of children and adolescents in emergency environments and hospital settings in general. The National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions (2008) report outlines a number of design strategies which can guide the design of paediatric EDs. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne provides a striking example of acute spaces designed for interaction and stimulation for children and adults. 02_ Older People

Older people make up a large proportion of ED presentations and are more likely to have longer lengths of stay in emergency. This can amplify overcrowding and access block. Furthermore, older people often suffer from cognitive impairment, physical disability and multiple medical conditions. Providing patient centred care for older people therefore requires a specialised approach to avoid missed diagnoses, prevent complications associated with

frailty, and ensure seamless care and discharge (Gray, 2013).

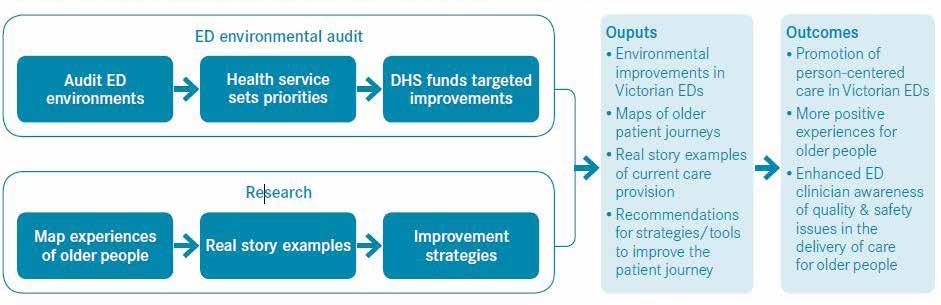

Case Study 02 reviews the care of older people in EDs with a focus on innovations documented at Westmead Hospital in Western Sydney. A combination of specialist streams has improved flows in ED at Westmead in line with NSW Health emergency models of care. In Victoria, environmental audits of EDs provide insight into the specific needs of older people in hospital settings and how to create more ‘older person friendly’ environments. In the United States, senior EDs are emerging as specialist services to provide environments that are more suited to older people attending emergency.

03_ Behavioural Health EDs are often used as a first point of care for mental health services for a number of reasons. This includes first time incidents, after hours, during psychotic episodes and overdoses. Mental health-related principal diagnoses have been reported in 3.7% of all Australian public hospital ED presentations in 2015-16. 60% of these presentations were recorded as being resolved without the need for admission or referral. Most of the remaining presentations resulted in hospital admission (MHSA, 2016).

Case Study 03 discusses approaches to dealing with mental health presentations at emergency, including specialist units such as psychiatric

emergency care centres, safe assessment rooms, behavioural health units and crisis management units. These services need to be supported by a range of specialist staff including mental health professionals and nursing. Despite the pressures of emergency environments and space constraints, high quality therapeutic design must be ensured in areas for mental health care.

04_ Patient Stress & Wayfinding

Besides ever-increasing demand and long wait times, violence and aggression has been identified as a major problem within EDs, with increased media spotlight on a number of violent incidents against staff in Victorian hospitals (Medew, 2017, Powley, 2017). Root causes of violence and aggression include patients who are alcohol or drug affected; stressed, frustrated and impatient; or presenting with acute mental illness or other behavioural health conditions. Case Study 04 explores how wayfinding, guidance and training can be used to reduce incidents of violence and aggression in EDs. “A Better A&E” is a design solution developed to provide a cost-effective method for improving safety and security, supporting staff wellbeing, and increasing patient satisfaction (Frontier Economics, 2013, p5). This approach can be adapted to support the NSW Health Emergency Department Models of Care (2012) and implemented state-wide in EDs dealing with high incidents of violence.

Patient stress, mental health crisis, and the experience of old and young are just some of the elements addressed in this research. Together, they provide insight into the diverse issues that need to be considered when addressing existing departments, optimising and refurbishing services, or building new. A deeper understanding of the people attending emergency can inform our approach to emergency care and the built environment in which it is delivered.

Emergency health care of the future must operate more efficiently and effectively to accommodate both the growth in demand and the introduction of new clinical technologies which expand the scope of acute care. (Fitzgerald, 2012).