6 minute read

Case Study 02: Older People

Australia’s aging population is a significant challenge across the health system and is recognised as having a disproportionate effect on EDs. Older people require emergency care more often than other populations, as well as experiencing longer lengths of stay and higher admission/readmission rates. The rapid triage and care process of EDs is often inadequate to manage the needs of older people with multiple medical conditions, a long list of medicines, communication challenges, and slowly evolving problems that impair effective understanding of the patient’s current need (Adams, 2003).

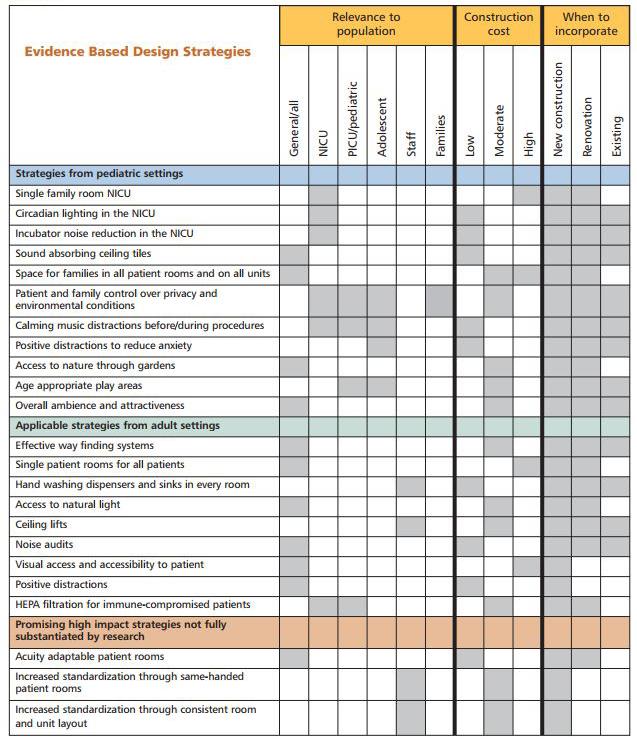

The appropriate care for older people needs to be integrated into the design of EDs. Functional decline reduces the ability for some older people to navigate the physical environment, communicate effectively, and maintain a level of independence in EDs (Fisk, A, Rogers, W, Charness, N, Czaja, S & Sharit, J, 2004, as cited in State Government of Victoria, 2009).

Advertisement

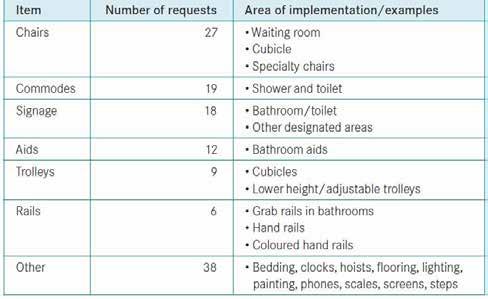

A 2008 initiative by Victoria Health focused on improving the experiences of older people in ED as part of a broader Patient Experience Program. An environmental audit of 21 major hospitals was used to identify and fund high priority items necessary to create more ‘older person friendly’ hospital environments (State Government of Victoria, 2009, p6). This audit revealed that there was a range of simple physical changes that could make considerable difference to older

patients. Supporting sensory and physical impairment with mobility aids; volume-adjustable phones; improved lighting, signage and visual contrast supported better patient experiences. The opportunity for clinicians to be involved in the audit also increased their awareness and understanding of the issues experienced by older people.

In 2013, the Aged Care Emergency (ACE) model of care was developed by the Emergency Care Institute NSW. The ACE Service model aims to support RACF staff to better manage residents experiencing acute onset symptoms within their facilities and avoid unnecessary transfer to ED. This includes providing telephone triage, and educational support for RACF. A collaborative working relationship between GPs, the community, RACFs and hospital care providers is required to ensure strong care continuity and case management.

Medical Assessment Units (MAU) have been established as an ED model of care in NSW since 2008. They are intended as inpatient short stay units co-located with emergency to provide care for the elderly, as well as those with chronic conditions, and as an alternative to treatment in ED. These services can deliver reductions in length-of-stay and waiting times for transfers to medical beds. Direct referral to MAU can improve a hospital’s ability to manage patient flow and reduce the number of complex non-critical medical patients presenting to ED (ACI, 2014). These services

provide specialist care to adults, and especially older people, who have a chronic and/or complex condition, or issues that may take time to assess and require a range of clinical expertise to diagnoses and treat.

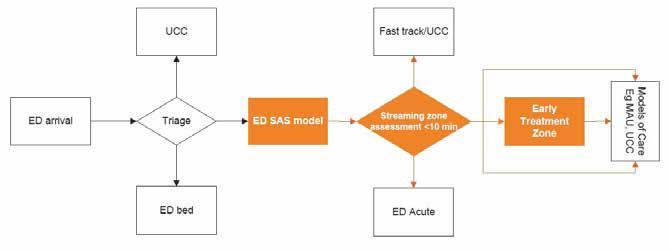

Westmead Hospital in Western Sydney has developed a comprehensive model for aged care within hospital settings which has expanded over more than 10 years. A particular focus on ED streaming has led to innovations in the models of care. In 2005, the Older Persons Review and Assessment (OPERA) Unit was established as a patient-centred short stay unit. In 2008, Health Care for Older Persons Earlier (HOPE) strategy was established to better manage the increasing numbers of older people presenting at hospitals and reduce access block in emergency.

A small rapid assessment unit known as HOPE_ED is located within the emergency apartment, providing initial assessment and treatment within 4-8 hours. Patients are then transferred to the HOPE/OPERA unit which provides a ward-based medical unit and allied health unit along with cardiac monitoring. Specialist assessment and management plan development occurs over 24-72 hours. The design of these units is focused around the specific needs of older patients including; delirium management, wandering patients, frailty and risk of falls, and the ‘trauma of admission’ (Loh, 2017).

The HOPE/OPERA strategy is able to provide better specialist care within comprehensive aged care service;

“The chief complaint-centred, single-encounter emergency visit typical of modern EDs is not an optimal setting for delivery of care to many complex geriatric patients.” (Burton, Young, & Bernier, 2014) Fig. 8

5. Victorian Emergency Departments Audit - Improving Experienced for Older People in ED. State Government of Victoria, 2009. 6. Frequently Requested Items in ED. Ibid.

stream older patients out of the ED, and support improved linkages with community care and Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACF) (Westmead Hospital, 2008). This is well aligned with the ED Senior Assessment and Streaming Model of Care and Toolkit (known as ED-SAS) was developed by NSW Health (2012 (2) ).

Alongside the Westmead HOPE-ED Unit, the Emergency Short Stay Unit (ESSU) was built in 2010 and expanded in 2016 to include 6 beds and 4 chairs. The ESSU is a discharge-stream model for patients with an expected length of stay of 4-24 hours and a high likelihood of discharge. The model of care is designed to support ED patient flow and the NSW Emergency Treatment Performance (ETP) commitment of 4-hours to transfer/discharge for 81% of all patients. It provides an alternative to inappropriate early discharge, while reducing length of stay for patients who would otherwise be admitted into a hospital ward. In order to ensure that the ESSU is not simply a ED overflow area, strict admissions criteria must be enforced to confirm suitability for admission. HOPE, OPERA and ESSU models of care at Westmead Hospital represent innovations in ED flow by targeting those presentations that are most likely to cause access block and overcrowding.

A new adult and paediatric ED is currently under construction at Westmead Health Precinct as part of a new acute services building, due to be

Health carers need to be trained in dealing with the issues of the ageing population, and we need to be able to identify appropriate models of care that reflect the whole person’s needs. (Parker, 2017).

completed in 2020. The design of this facility will incorporate the models of care developed in the existing department.

Increased understanding into the experience of older people in emergency and the complexity of their care has led to specialist geriatric emergency rooms in the U.S. The Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland, commissioned the first Senior Emergency Department in 2008 with dedicated facilities and specialised nursing, emergency services, and social workers. This trend has responded to the demographic change in the U.S. The focus of the Holy Cross Hospital senior ED is on making patients more comfortable through increased privacy, natural lighting, acoustic separation and calming environments. Specialised nursing and social workers are provided training and support to prevent falls, assist with mobility, and support continuity of care. Screening for problems such as memory impairment and risk of

falls occurs at registration to support nursing during the visit (Noonan, 2012).

In 2017, a Senior Emergency Center was established at Atrium Medical Centre in Middletown, Ohio. The renovation of the 8-bed unit focused on safety features for older adults; adjustable temperature and lighting, private rooms, and specialist training (Schwartzberg, 2017). Warm tones, material selection and contrast have been considered in the design to provide a restful environment. The seniors unit operates as a specialist stream out of the core ED, improving patient flow and providing extra support for older people.

Streaming services, specialised nursing, support and approaches to design are combined in these examples to address the needs of older people in emergency. The increasing proportion of older people in emergency will likely lead to more EDs developing specialist branches to address demand. Cost effective renovations are possible even within existing services, but these need to be supported with improved training and knowledge of geriatric emergency care.

Fig. 10 Fig. 11

Atrium Medical Center - Senior Emergency Center.

Location: Cincinnati, Ohio. Completed: 2017 7. Emergency Department Senior Assessment and Streaming. NSW Health, 2012. 8. Atrium Medical Center’s Senior Emergency Center front desk and nurse station. WCPO, 2017. 9. Atrium Medical Center’s Senior Emergency Center private single room. Ibid.