MILK PRODUCER MAGAZINE CELEBRATING 100 YEARS 19 25-2025

JUNE 2025 | THE VOICE OF ONTARIO DAIRY PRODUCERS

MILK PRODUCER MAGAZINE CELEBRATING 100 YEARS 19 25-2025

JUNE 2025 | THE VOICE OF ONTARIO DAIRY PRODUCERS

PUBLISHED BY

DAIRY FARMERS OF ONTARIO

6780 Campobello Road Mississauga, ON L5N 2L8

ADVERTISING

Pat Logan pat.logan@milk.org 519-788-1559

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Katrina Teimo

CONTRIBUTORS

Dairy Farmers of Ontario, Jeanine Moyer, Sean Tarry, Hanne Goetz, Lactanet, ACER Consulting, Dairy Farmers of Canada, Veal Farmers of Ontario, Workplace Safety & Prevention Services

Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Product Agreement No.40063866.

Return postage guaranteed. Circulation: 8,000. ISSN 0030-3038. Printed in Canada.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

For subscription changes or to unsubscribe, contact:

MILK PRODUCER

6780 Campobello Road

Mississauga, ON L5N 2L8

Phone: (905) 821-8970

Fax: (905) 821-3160

Email: milkproducer@milk.org

Opinions expressed herein are those of the author and/ or editor and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or policies of Dairy Farmers of Ontario. Publication of advertisements does not constitute endorsement or approval by Milk Producer or Dairy Farmers of Ontario of products or services advertised.

Milk Producer welcomes letters to the editor about magazine content.

*All marks owned by Dairy Farmers of Ontario.

www.milkproducer.ca www.milk.org

Facebook: /OntarioDairy

X: @OntarioDairy

Instagram: @OntarioDairy

LinkedIn: dairy-farmers-of-ontario

By Mark Hamel, Board Chair, Dairy Farmers of Ontario

There is a meeting room at the DFO head office where copies of every issue of the Milk Producer are caringly displayed, from 1925 to today. One hundred years of serving as the voice of dairy farmers, sharing our stories and expertise to help manage better dairy farms.

Looking through past issues over the last 10 decades, it is remarkable to see the evolution and changes in our sector. Perhaps more remarkable is what has endured, dairy farmers pride in our farms and producing quality milk for Ontarians. It is also amusing to see how advertisements have changed (or not) over the years. In this issue, we are sharing some of those moments and industry stories with all of you, honouring the Milk Producer tradition.

We get caught up in the day-to-day management of the sector and our respective businesses,

distracted by global events, busy with community commitments, and preoccupied with caring for our families.

Our strength as a sector continues to be our commitment to work together as dairy farmers, to sustain not only our individual farms but the sector as a collective. Together we are able to tackle challenges, united we are stronger, and collectively we are responsible for maintaining the trust and confidence of Ontario consumers in Canadian milk.

We need to collectively invest in maintaining the delivery of high-quality, sustainable milk for Canadians. That requires every farm licensed to produce milk in Ontario to meet all policies and requirements to ensure quality, safe milk is collected by DFO and sold to our customers to transform into dairy products. DFO is committed

Vicky Morrison

to working with farmers to ensure we have the right programs and policies to support continued investment on farms, providing access to the tools and information to make responsible business choices for our respective farm operations.

And Milk Producer continues to be an important vehicle to transfer knowledge on best practices, first-hand experience and other tools to support Ontario dairy farmers.

Together, we all have responsibilities and opportunities to help ensure that Ontario dairy continues to be a flourishing sector, nourishing our communities for the next 100 years.

We hope you enjoy this special issue, celebrating 100 years of Milk Producer, our shared history, our farms, our families, our community.

For a century, the Milk Producer has been the trusted voice of Ontario’s dairy farmers — advocating, informing, and inspiring progress. We’re proud to stand alongside the industry it champions, supporting dairy producers, Milk Producer, and the future of Canadian agriculture.

Jordan Bowles, CPA, CGA, Partner 226.775.3033 | jordan.bowles@mnp.ca

Milk Producer magazine is the official publication of Dairy Farmers of Ontario and was launched in 1925 to keep producers and stakeholders informed about the dairy industry. The magazine is celebrating 100 years in production this year!

As the voice of Ontario dairy farmers, Milk Producer has been dedicated to the health and welfare of all aspects of Ontario’s dairy sector – from the animals under farmers’ care, to the farms themselves, to the safe and reliable system that produces high-quality milk for consumers.

Milk Producer has continued to be a key point of contact for the producer community and its stakeholders. The publication reaches dairy farmers, as well as veterinarians, industry organizations, education, government, and other stakeholders.

By Cheryl Smith, Chief Executive Officer, Dairy Farmers of Ontario

It is humbling to celebrate 100 years of Milk Producer with all of you – generations of Ontario producers, DFO team and industry colleagues, past and present.

Since June 1925, Milk Producer has been the voice of Ontario dairy producers, bringing together farmers and industry experts from across Ontario and Canada to share stories and best practices in support of a dynamic and growing dairy sector.

When you read the stories that give voice to the legacy that is Ontario dairy over the last 100 years, resilient, dedicated and hardworking come to mind.

The enduring promise of the dairy sector and unwavering commitment to our community is nothing short of remarkable. It also speaks of the humble, steadfast focus

that has been passed down from generation to generation, throughout the last 10 decades, to produce high-quality milk for Ontarians.

From 1925 to today, Ontario dairy has been a steady, comforting part of Canadians every day, thanks to your commitment and passion. Then and today, Milk Producer is your voice, your community resource to share experiences and best practices, translating research and science into practical applications on your farms. Animal nutrition and herd care, genetics, soil and crop management, farm financials, Milk Producer strives to provide tips to support all aspects of operating a well-managed dairy farm.

Working in dairy is a privilege. The dedicated DFO team are passionate about

working with 10,000+ dairy farmers and your families, our customers and industry partners, to deliver high-quality milk from Ontario’s 3,187 farms.

Together, we provide Canadians with nourishing dairy products, while caring for our communities and investing in Canada.

We look forward to continuing our work with dairy farmers to remain a trusted source for milk and dairy products by Canadian consumers.

To all the farmers who have generously

By Jeff Hyndman, Executive Director, Regulatory Compliance and Quality Assurance, Dairy Farmers of Ontario

DFO HAS ALWAYS BEEN COMMITTED to producing some of the world's highest-quality milk, which is deeply rooted in Ontario's rich dairy history. As part of our shared history, Ontario dairy producers have always pushed for continuous improvement, ensuring they consistently meet their customers' evolving demands.

As a part of that commitment, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA) delegated authority to DFO to administer and enforce the Raw Milk Quality (RMQ) Program under Regulation 761 of the Ontario Milk Act for bovine milk. DFO appoints the Director of Regulatory Compliance (DRC) to oversee this crucial program. As the current DRC, I oversee sampling, milk and water quality testing, farm inspections, penalty applications, and Bulk Tank Milk Grading activities and performance. This responsibility extends to the activities of the Production Division, which was established in the founding year of the Ontario Milk Marketing Board in 1965. The work of this division is central to the quality of milk produced on Ontario farms, a topic my DRC Corner will highlight in this special 100th year anniversary issue of the Milk Producer.

The importance of milk quality was recognized early on in our history. In November 1965, the Ontario Milk Marketing Board (OMMB) established a Quality Committee, tasked with addressing the quality requirements outlined in the Milk Act and its regulations – a matter of great significance for the 11,255 dairy farmers in Ontario at the time. This early focus set the standard for our commitment to milk quality. For example, in 1980, a new Grade A bacteria standard introduced a total plate count limit of 50,000 CFU/mL and limits on coliforms, psychrotrophs, and the absence of Salmonella and Listeria. This standard was further reinforced in 1981 by adopting a single milk quality benchmark requiring all farms to meet Grade A requirements.

Responding to producers' evolving needs, the OMMB launched the Udder Health Management Program in April 1982 to improve milk quality by reducing somatic cell counts (SCC) and mastitis. This program provided on-farm technical support to producers on a partial cost-recovery basis.

This proactive approach was further strengthened by adopting a fresh milk sampling and testing program on March 1st, 1985, followed by implementing a penalty program for high somatic cell counts on August 1st, 1989. The OMMB's commitment to ensuring the highest quality milk was evident in the gradual reduction of the acceptable bulk tank SCC limit from 800,000 cells/mL in August 1989 to 500,000 cells/mL by August 1995, and further to 400,000 cells/mL in 2012, demonstrating the industry's readiness to meet increasingly stringent quality standards.

The evolution of the RMQ program continued with DFO assuming responsibility for the program from Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (now OMAFA) in 1998. This transition was supported by a dedicated team of Field Service Representatives (FSRs) within DFO's Production Division.

In 2003, the Ontario Dairy Quality Assurance Program requirements were finalized, encompassing crucial aspects like the Livestock Medicines Certificate, potable water, timetemperature recorders, and Standard Operating Procedures. This program evolved into the national Canadian Quality Milk (CQM) program in 2010, with full producer compliance required by 2014. CQM subsequently formed the basis for Dairy Farmers of Canada’s proAction initiative, which was launched in 2015 and remains a cornerstone of the national quality assurance framework.

Continuous improvement in testing methodologies has also played a vital role in our history. Starting June 1, 2010, a new lab testing contract provided producers with more comprehensive data for farm management, including composition, SCC, freezing point, and weekly bacteria testing using Bactoscan. The recent implementation of the Enhanced Lab Services program in 2024 further enhances this by providing producers with timelier and more actionable Bactoscan results for each bulk tank, typically within two days of sampling.

As we look towards the future of milk quality in Ontario, our history underscores our enduring dedication to producing some of the highest quality milk in the world. The continued hard work, innovation and commitment of Ontario's dairy producers, building upon this rich history, will continue to raise the bar on milk quality.

PACKED WITH A HIGHER CONCENTRATION OF IGG, IMMUNOLIFE | 200 IS THE ULTIMATE CHOICE FOR YOUR CALVES' HEALTH AND VITALITY.

FUTURE PERFORMANCE IS: 100% CANADIAN SKIM TO SUPPORT THE CANADIAN DAIRY INDUSTRY

Patrice Dube began his distinguished career with Dairy Farmers of Ontario in 2008 as an Economist, bringing with him a wealth of experience and knowledge in the Canadian dairy industry honed through previous roles with the Canadian Dairy Commission and Les Producteurs de lait du Québec.

As Chief Economics & Policy Development Officer, Patrice played a critical role in shaping DFO’s policy and economic strategies, working closely with the DFO team and Board, provincial partners, and industry stakeholders to address pressing dairy issues.

Patrice’s depth of knowledge and unwavering commitment to the dairy industry has created a lasting impact. His contributions helped shape the future of provincial and national dairy policy, and his leadership supported the development of those who have had the privilege to work with him.

Dairy Farmers of Ontario (DFO) has an annual scholarship program that offers up to six $5,000 scholarships to high school students entering a post-secondary degree or diploma program in agriculture.

To be eligible for these scholarships, an applicant must:

• be the son or daughter of a DFO licensed producer;

• be entering semester one of an agricultural degree program or a diploma program with a demonstrated tie back to agriculture (up to one scholarship will be available from a non-traditional degree or diploma program);

• have achieved an average of 80 per cent or greater in Grade 12 credits (best six to be averaged).

Selection criteria will be based on:

• academic achievement;

• future career plans;

• demonstrated leadership in secondary school and community activities.

How to Apply:

• Application forms are available on DFO’s website at new.milk.org under Industry Login. On the left-hand side, go to Documents > Forms > Application for DFO Scholarships.

• Dairy Farmers of Ontario must receive complete application forms by Aug. 30, 2025, to be considered.

For details: contact Robert Matson at robert.matson@milk.org or 905-208-7981

On behalf of DFO, we extend tremendous gratitude to Patrice for 17 years of dedicated service.

Q: Over the last 35 years, as you worked on policy to support growth and advancement of the Canadian dairy industry, what was your primary motivation to persevere through the challenges?

A: It has been a privilege and an honour to represent Ontario dairy farmers over the last 17 years and to work for the Canadian dairy industry for over 35 years. Throughout the years, surveys have consistently shown that Canadians recognize the importance and have trust in dairy farmers. During my career, I always admired dairy farmers’ personal and family values, for being hard workers and their natural sense to have the common good prevail over the individual interest.

Q: Looking back, what changes stand out for you? Looking forward, what do you hope to see as the next policy goal?

A: The Canadian dairy industry has certainly evolved over the last three decades. In this world full of uncertainties, what stands out is that supply management is an amazingly resilient system.

However, there remains a lot to do. Supply management must be a dynamic model, not a static one, and it should be treated like a national treasure. It needs to be cherished and nourished so that it can continue to grow and evolve. An integrated national pool, where not only revenue, but also all fluid and industrial markets and costs can be fully pooled in a fair and equitable way amongst producers across the country, is, in my view, a goal that is within reach in the foreseeable future. Such an achievement would be the ultimate recognition that there is only one national dairy market. That is my most sincere wish for the future of the industry.

Q: Over the last few months as you’ve shared stories, they always center around the people that you’ve met and worked with along the way, and the impact that had on your career.

A: I am thankful to have worked with Cheryl and Kristin and all their support. I am grateful for the DFO and national staff, and their dedicated work for the good of the industry and their friendship. I also thank Peter Gould and Phil Cairns for giving me the opportunity to work at DFO. It is a great organization that is steadfast in its commitment to Ontario dairy farmers.

‘‘ All future tankers I’m going to add to my fleet will be outfitted with this new suspension. ’’

Yvon Guérard Forfait Somerset, Plessisville, QC

‘‘ Over rolling hills, even little bumps, it’s smooth working with a tanker fitted with the XT suspension. The tanker is independent from the tractor and its draw bar is no longer rigidly attached to the tractor. It is flexible and it actually follows the contour of the terrain. There’s a customer that we go to and there’s a 1-and-a-half-foot drop we need to drive through and there’s only one tanker that I will go there with, the one fitted with the XT suspension. ’’

BRITISH COLUMBIA

Mountain View Electric Ltd.

Enderby — 250 838-6455

Pacific Dairy Centre Ltd.

Chilliwack — 604 852-9020

ALBERTA

Dairy Lane Systems

Leduc: 780 986-5600

Blackfalds: 587 797-4521

Lethbridge: 587 787-4145

Lethbridge Dairy Mart Ltd.

Lethbridge — 888 329-6202

Red Deer — 403 406-7344

SASKATCHEWAN

Dairy Lane Systems

Warman — 306 242-5850

Emerald Park — 306 721-6844

Swift Current — 306 203-3066

MANITOBA / NW ONTARIO

Penner Farm Services Ltd.

Blumenort — 204 326-3781

Thunder Bay ON – 800 461-9333

Tytech

Grande Pointe — 204 770-4898

ONTARIO

Claire Snoddon Farm Machinery

Sunderland — 705 357-3579

Conestogo Agri Systems Inc.

Drayton — 519 638-3022

1 800 461-3022

County Automation

Ameliasburg — 613 962-7474

Dairy Lane Systems

Komoka — 519 666-1404

Keith Siemon Farm Systems Ltd.

Walton — 519 345-2734

Lamers Silos Ltd.

Ingersoll — 519 485-4578

Lawrence’s Dairy Supply Inc.

Moose Creek — 613 538-2559

McCann Farm Automation Ltd.

Seeley’s Bay — 613 382-7411

Brockville — 613 926-2220

McLaren Works

Cobden — 613 646-2062

Melbourne Farm Automation

Melbourne — 519 289-5256

Watford — 519-876-2420

Silver-Tech Systems Inc.

Aylmer — 519 773-2740

Dunnville — 905 981-2350

ATLANTIC PROVINCES

Atlantic Dairy Tech.

Charlottetown, PE — 902 368-1719

Mactaquac Farm Equip. Ltd.

Mactaquac, NB — 506 363-2340

Sheehy Enterprises Ltd.

Shubenacadie, NS — 902 758-2002

Sussex Farm Supplies

Sussex, NB — 506 433-1699

YEARS of dairy by

1925

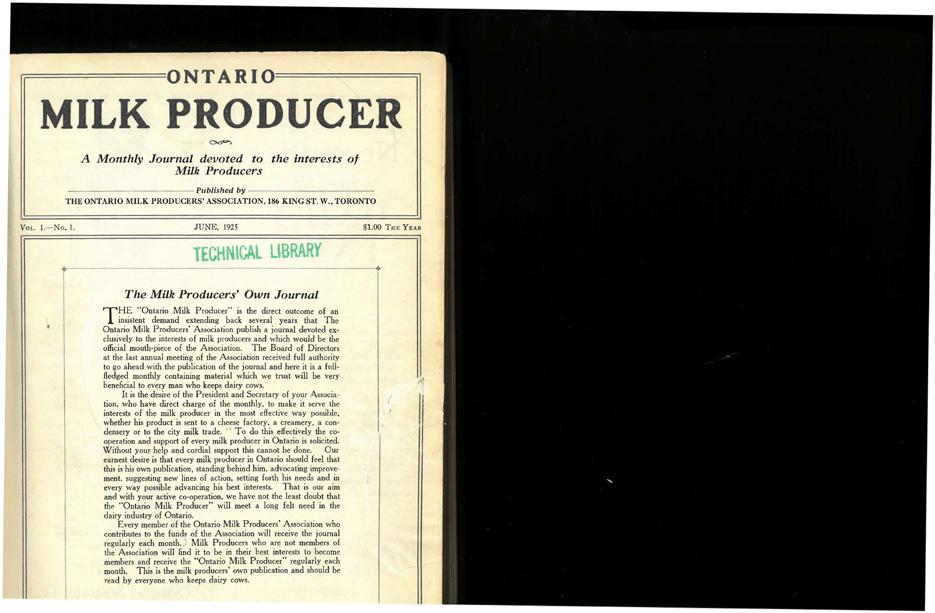

Ontario Milk Producer's first issue in June 1925 clearly stakes out the magazine's turf as an advocate for family dairy farms.

The Ontario Milk Producer is the direct outcome of an insistent demand extending back several years that The Ontario Milk Producers' Association publish a journal devoted exclusively to the interests of milk producers and which would be the official mouth-piece of the Association.

1926

Ice provides the only source of cooling on the vast majority of farms. Change is in the wind as Frigidaire introduces a new electrical powered cooling device. This early cooler has a brine tank that holds up to six 10-gallon milk cans. Outside the immediate vicinity of towns and cities, however, many farms lack electricity.

In the latter half of the 1920s, a prosperous economy sets the stage for higher fluid milk prices. Issue after issue of the magazine calls for better returns to producers.

1928

The Canadian Creamery Association of Ontario votes to support pasteurization of all cream made into butter. By November 1929, the magazine reports the majority of fluid processors favour pasteurization.

The magazine also provides tips for on-farm quality improvements. For example, many producers still milk by hand into pails. A 1925 report on tests at Ottawa's Central Experimental Farm notes that poorly cleaned pails are the chief source of bacterial contamination.

The Depression years bring a battered economy and low milk prices. Producers band together and develop associations to help negotiate for better prices.

1930

The Dairy Products Act comes into effect. It regulates milk sampling and handling in processing facilities.

1932

The Depression hits producers hard. Prices for farm products are lower than the values of the same products in 1913.

1933

Ontario Milk Producer editorial says, "Without effective organization there is no hope of stabilizing the fluid milk market." In May, the Ontario Whole Milk Producers' Association meets for the first time.

1933

A quota system is introduced in Toronto for the fluid market.

The Ontario Whole Milk Producers' Association board asks the provincial government to enact laws requiring all distributors of milk for public consumption to be licensed. This is to protect producers by maintaining prices, guaranteeing payment and standardizing butterfat content.

1934

The concentrated milk producers form an association to help them negotiate minimum prices with processors.

1936

Milk consumption is higher in rural areas than in cities, says a study by the federal government. Per capita consumption per day in Ontario was 0.9 pints (500 mL) in rural areas compared to 0. 71 ( 400 mL) pints in the city surveyed.

1937

Labour costs in milk production are published. A typical wage might be a dairyman paying $25 a month plus board valued at $20, a total monthly wage of $45. "With 30 working days during the month, of 10 hours each, this would resolve itself into a rate of 15 cents per hour."

Researchers interview 1,500 dairy producers. The project says the average return per cow unit of livestock is $79 in the fluid milk zones and $56 in the processed milk zones.

The industry continues to call for pasteurization of all milk. Laws making pasteurization compulsory in all parts of Ontario are in effect by the end of 1938. Artificial insemination (Al) in cattle is developing. In Canada, the practical application of Al had begun in Manitoba in 1932. The first unit is organized in 1938.

Throughout most of the war years, the Wartime Prices and Trade Board dictates legal prices for many commodities at all levels. The war effort encourages dairy farmers to produce as much milk as possible. But farmers are compensated at much lower levels than industrial workers.

1940

Britain appeals for all the cheese Canada can produce. Ontario, the nation's biggest cheese producer, is seen as the major supplier. Cheese factories gear up to increase production 25 per cent.

1942

After the government freezes fluid milk prices, some fluid shippers threaten to kill off their herds for beef. The magazine points out that farm prices are just 43.5 per cent of the prices received in 1926. Yet industrial wages are 19.6 per cent higher than wages in 1926. Intensive lobbying later brings farmers modest increases.

1945

As the end of the war nears, the June 1945 Milk Producer reflects on dairy industry changes in the past two decades: "The last 20 years have seen tremendous advances in farm organizations, not so much for educational or social purposes, not at all for political reasons, but to ensure for the farmer a fair deal on the market."

Anti-margarine sentiment characterizes the Ontario dairy industry in the 50s, as the less costly product and cuts into butter sales. Quebec bans the manufacture and sale of margarine. The Premier says, 'The government will do all that is within its power to strengthen measures against such competition against the dairy industry."

Dairy Farmers of Canada launches its first national promotion campaign in the 1950s. Slogans from that campaign include: "Make Mine Milk;" "Pass the Butter, Please;" "OK, But Where's the Cheese?" and "Let's Have Ice Cream-Everybody Likes Ice Cream."

1951

Artificial insemination continues to make strides. Canadian farmers and cattle breeders have accepted it and organized breeding units are operating in every province. Some are large, carrying fifty or more bull studs.

1953

Bulk milk collection begins. Ideal Dairy in Oshawa runs a small pilot project, the first of its kind in Canada. Producers in the project replace their ordinary coolers with bulk tanks. Proponents of bulk collection say the method promises lower transport costs, higher butterfat tests, more accurate weighing without milk losses, and reduced handling costs at the farm and dairy.

Canada's first Dairy Day is held at a farm near Alma, Ont. in the summer of 1953. Eight thousand people attend

Organizations such as the Toronto Milk Producers Association have well-developed policies on quotas for individual producers. The association takes on responsibility for selling, placing and hauling of milk for its members.

1949

The industry as a whole starts to come to grips with other challenges. Margarine becomes a legal product by the end of the decade, creating competition for butter. About the same time, the magazine starts carrying regular reports about disease threats-particularly the rise of brucellosis.

Insemination gets a further boost. The federal experimental farm services establish a frozen semen laboratory at the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa for shipping frozen semen to herds at branch farms across Canada. This new technique offers breeders a wider bull selection. 1956

Dairy research needs to be funded by both government and dairy farmers. 'There is a crying need for the organizations of this country to not only provide more of their own funds but to promote the use of a greater portion of public for dairy research in all its phases.

Towards the end of the decade, a magazine editorial worries about the effect the advent of 2 per cent milk is having on sales and producer quotas.

During the first half of the 1960s, the Ontario dairy industry focuses much of its energy on debating what kind of marketing plan it needs. Halfway through the decade, a new marketing plan is devised and the industry spends the rest of the 1960s implementing it.

1961

The magazine reports two political appointments that would eventually loom large in the industry's future. William Stewart is named Ontario agriculture minister and Everett Biggs, his deputy minister. This dynamic duo set in motion a process that eventually ends the debate with the establishment in 1965 of the Ontario Milk Marketing Board (OMMB).

The magazine ensures dairy farmers are well-informed about the process leading up to the board's formation. From September 1963 until June 1964, it covers the Ontario Milk Industry Inquiry Committee hearings held across the province.

1965

The magazine excerpts five pages from the new Milk Act. By August, it reports that George McLaughlin is chair of the new OMMB.

In the 1960s, producers begin replacing their bucket milkers with pipeline milking systems.

As the OMMB moves forward with reform of transportation, producer payment and other key policies, the magazine is there to explain it. As the decade draws to a close, reports and editorials promote a strong and united industry in the face of a challenge to pooling by the Channel Island Breeds. The OMMB wins. It then turns its attention to raising returns for beleaguered milk shippers and begins to talk about a national supply management plan.

In addition to updating dairy farmers about OMMB policies, the magazine alerts them to threats to milk consumption. Nuclear bomb testing, for example, heightens public fears about Strontium 90, a radioactive isotope, getting into milk. However, numerous articles declare milk is safe. Another danger to milk consumption, the magazine warns, is the growing popularity of soft drinks. In January 1963, it reports the Dairy Farmers of Canada promotional budget is $350,000. In February, it notes Coke and Pepsi are likely to spend $30 million each to promote their soft drinks in North America.

1967

Milk bags make their debut.

1968

Group I Price Pooling commenced March 1st

The 1970s bring dairy supply management and the metric system. The OMMB begins making payments on behalf of plants as the Industrial Plan comes into effect in 1970. While initial producerprocessor relationships stay the same, the board plans to reorganize transport routing to improve efficiency.

1970

Transport charges are pooled and milk pricing by end-use classification comes in. Also in 1970, the plate loop count comes in as new method for testing raw milk for bacteria, replacing the resazurin test.

1972

The two-colour milk logo in use today starts to be used in displays and promotional materials.

1974

One farm family fed itself and 50 other people, four times as many as in 1944, notes Ontario Milk Marketing Board chair George McLaughlin.

The first milk calendar is printed and distributed to Canadian households.

1975

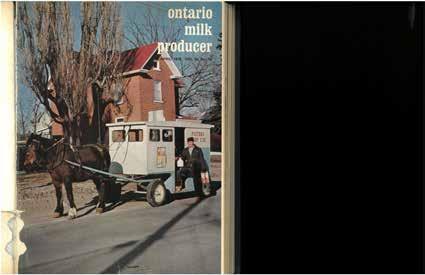

Ontario Milk Producer magazine features the last known horse-drawn milk wagon operating in Ontario on its magazine cover.

Industrial shippers are invited to apply for graduated entry into the fluid pool. The industrial pool begins for southern Ontario.

1976

Federal researchers can now determine calf sex nine months before birth, the magazine reports, describing this as a first in world breeding. Agriculture Canada veterinarians can now determine the sex of a twoweek-old calf embryo taken from its natural mother's uterus.

World trade is under scrutiny. Exports are not the bulk of a producer's cheque, Richard Tudor-Price, director of marketing for the Canadian Dairy Commission, says in 1976. "World trade in dairy products is extremely small relative to total production. No more than five per cent of world dairy production is traded outside the trading entity in which it is produced."

1977

A skim-off levy is introduced as a way for compensating MSQ shippers for lost market share. As the decade wraps up, the editor runs a series about using personal computers to help run a farm business, foreshadowing the importance of computers as a dairy management tool.

The move to bulk tanks continues as industrial shippers are required to have a bulk tank large enough to hold two days of production. Fluid shippers still using cans convert to bulk tanks by the end of 1977.

Quota transfers become an issue as producers say the system creates additional expense. Staff propose a quota exchange as a way of transferring quota. Quota prices are a topic at Geneva Park in 1977. Alternate methods of transferring quota are discussed and assessed as the decade closes.

1978

The OMMB converts to metric April 1. Milk is now officially measured in hectolitres.

Expanding markets and quota increases mark the beginning of the decade. But controversy arises just after the OMMB launches its new quota exchange. Quota values start to climb. Numerous studies conclude that freely negotiable values for quota are in the best interests of producers, consumers and the economy in general. Yet the high quota value debate never goes away.

1982

Udder Health Management Program commences in April.

1983

DFO opens a new head office in Mississauga following inaugural years in downtown Toronto.

National Milk Marketing Plan, part of Canada's supply management system, was developed. The primary goal was to manage milk supply and prices to ensure a stable and predictable dairy market for both producers and consumers.

1985

A welcome report announces that Canada, including Ontario, is now declared brucellosisfree. Eradicating the disease had taken decades.

The following year, OMMB chair, Ken McKinnon, steps down after nine years at the helm to become vice-chair of the Canadian Dairy Commission. Grant Smith assumes the mantle of leadership, becoming only the third chair in the OMMB's 20-year history. Among the bigger issues he must tackle is trade. When Canada enters free-trade negotiations with the U.S. in the mid-1980s, producers grow increasingly concerned about Ottawa trading away our dairy industry.

The February issue reports Agriculture Minister John Wise's announcement that a new import control list will cover key dairy products. The new free trade agreement won't affect supply management.

1989

Penalty program for high somatic cell counts introduced August 1st.

Dairy farmers now turn to their General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations. Article XI of the GATT, which permits a country to restrict imports of a certain commodity, is seen as crucial to supply management's future. An interim GATT agreement is signed in 1989 to prevent escalation of trade-distorting subsidies in Europe and the U.S. Canadian dairy farmers are unfairly penalized when Ottawa caps industrial milk prices in response. Producer concerns escalate, and in May, the magazine reports that Ottawa is sending mixed signals about its intentions in the trade negotiations.

Consumer preoccupation with low-fat foods flavours the 1990s. One per cent milk is approved by Ontario Farm Products Marketing Commission in 1990. The OMMB, concerned with skimoff, increases the skimoff levy.

In the 1990s, product promotion includes Toronto Blue Jays Joe Carter and Toronto Maple Leafs Doug Gilmour in two highly memorable advertising campaigns. Also, the Ontario Dairy Princess Program ends mid-1990s, replaced by the Ontario Dairy Education Program.

1991

Food Bank Program for fluid milk products is initiated. Producers donate a portion of their shipments to the program. Milk transporters transport the donated milk free of charge. Participating dairy processors process and package the donated milk free of charge. The resulting products are donated to the Food Bank.

The P5 Agreement is established involving Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec, and will pool markets and revenues to rebalance producer bargaining power.

MSQ is issued in kilograms of butterfat rather than in hectolitres of milk. Multiple component pricing begins.

1992

Starting in 1992, separate prices for the kilograms of fat, protein and other solids determine milk cheque payments. The system now allows for prices to change as consumer preferences for milk components change.

Farmers swarm Parliament Hill on February 21st at an Ottawa rally, the climax of a month-long lobbying campaign. The rally shows support for supply management and asks for a clarified Article XI in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

The national pooling plan brings special class prices. As well, six provinces strike a deal on promotion spending.

Stiffer milk quality regulations come in January. Producers with continued high somatic cell counts can now be shut-off from market.

1993

The Lifetime Profit Index shifts to emphasize protein.

In 1993, cream producers have been allowed to convert 100 per cent of cream quota to milk.

1994

The GATT agreement is signed. It will allow the Canadian dairy industry to continue using supply management in an altered form, but deems producer levies to be export subsides. Price pooling is allowed.

Canada’s first organic dairy products are launched in Ontario. First on-farm dairy processing plant established in Ontario.

Single pool, payment and quota system implemented August 1st

Graduated entry for industrial shippers, in place since 1971, is cancelled to help integrate industrial and fluid shipping completely. The single-quota payment system comes in August 1st. The province's four pools each had their own quota, payment, allocation, and transportation policies. These four pools merge into one.

1995

Dairy Farmers of Ontario (DFO) is formed from the OMMB and the Ontario Cream Producers Marketing Board.

The Ontario government allows butter-coloured margarine to be sold.

Microfiltered milk is introduced. The new technology has an extended 60-day shelf life.

Free Trade Agreement dispute with the U.S. about access to ice cream and yogurt markets in 1996.

Daily quota begins in Ontario.

DFO commences participation in the interprovincial quota exchange with Quebec and Nova Scotia.

DFO assumes responsibility for the raw milk quality program. DFO switches to BactoScan from plate loop count test for bacteria testing.

Butteroil-sugar blends, an import problem since mid-1996 occupy DFC.

Pooling of transportation costs across the P5 commences August 1st

Major ice storm affects milk pickups and processing in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec. Many producers and plants without power for days, and some for weeks. Ontario transports milk to Michigan for processing and re-import to Canada.

The first commercial automatic milking system (AMS or ‘robotic milking system’) in Ontario is introduced.

Debate over the use of rbST in milk production continues over the decade. Health Canada decides not to approve the product.

Scientific technology advances rapidly. One major development is successful animal cloning research, leading to calf clones.

A short-lived interprovincial exchange ends after Nova Scotia pulls out in early 1999. Ontario pulled out in 1998. Quebec was the other participating province.

The United States and New Zealand launch a WTO challenge against Canada. The legitimacy of the commercial contracting systems for export milk that were implemented by all provinces following the 1999 WTO Ruling against Canada on special classes 5(d) and 5(e) was challenged. The essence of the challenge was that the commercial export contracting, like special classes 5(d) and 5(e), still constituted an export subsidy. The WTO Compliance Panel ruled in favour of the United States and New Zealand.

2001

DFO receive a $2 million grant from the Ontario Government’s Early Years Challenge Fund to support the expansion of the DFO Elementary School Milk Program.

2003

Requirements for Ontario Dairy Quality Assurance Program finalized by DFO Board in May. Program requirements (Livestock Medicines, Certification, Potable Water, Time Temperature Recorders, Standard Operating Procedures) to be phased in and fully implemented by January 1, 2007.

2004

CMSMC takes steps to limit the production of solids-not-fat within the available butterfat quota. The policy measures were designed to limit the size of the structural surplus to what can be readily marketed through low valued internal markets and within Canada WTO limits for subsidized dairy exports.

2005

DFO introduces a policy to cap the solids-non fat production of producers at 2.35 with the ratio being administered on a cumulative dairy year basis. Ontario producers become subject to a zero payment policy for within-quota SNF production in excess of the ratio.

2006

Characterized by growth, investment, and evolution, the dairy system faces tough trade challenges, but dairy farmers and sector partners feel the support of the Canadian government and consumers for a system that works.

2010

After working through issues for several years with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), DFO and the Ontario Dairy Council (ODC) sign a five-year contract with the University of Guelph to be its laboratory services provider. Under the new contract, all producer milk samples are tested for composition, SCCs and freezing point estimates, and one sample is tested weekly for bacteria.

2011

The Ontario Court of Justice reaffirm that the sale, delivery or distribution of unpasteurized milk or milk products is prohibited.

2013

CMSMC takes the decision to create a more competitively priced milk class (Class 3d) for mozzarella cheese used on fresh pizzas. The main purpose of this new milk class is to provide restaurants access to mozzarella cheese at a reduced price for pizza prepared and cooked onsite.

DFC's proAction is launched.

TTP negotiations conclude.

In times of milk surplus, DFO begin skimming milk where only the cream is retained by the plant and the skim milk is non-marketed. This is in response to increases in demand for butterfat only without a corresponding requirement for protein.

DFO makes a number of changes in producer quota polices to curb and limit the escalation in quota prices and values.

2009

The P5 Harmonized Quota Policy, which includes the New Entry Quota Allocation Program (NEQAP) is adopted. This policy aims to harmonize dairy quota practices among the five provinces involved in the P5 Agreement. NEQAP was a key component, allowing new entrants to the dairy industry to acquire quota.

New Producer Program (NPP) is developed which allow new producers to enter the dairy industry, via means other than through the purchase of an existing farm operation or NEQAP.

Opening of Dairy Facility at the Elora Research Station. The $25-million, 175,000-square-foot research facility is completed in May. It is a joint project of the Agricultural Research Institute of Ontario (ARIO), the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), the University of Guelph and the Ontario dairy industry represented by the Dairy Farmers of Ontario. The Dairy Facility is managed by the University of Guelph through the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance, a collaboration with OMAFRA. The facility enables world-class research that helps keep the Ontario and Canadian dairy sectors innovative, competitive and sustainable. World dairy prices and the tariff wall international dairy product prices drop substantially. The sharp drop in prices comes after the biggest importer of dairy products, China, cut imports, and the second largest importer, Russia, banned imports from the US and the EU. This led to the sharp drop in prices to clear the excess supply in the market.

The National Ingredients Program is designed to provide greater opportunity for growth, innovation and investment by providing a more competitive market for domestic dairy ingredients.

The Ontario Ingredient Program is implemented, which includes the creation of a new competitively priced ingredient class, Class 6. The Ontario ingredient program creates an environment for dairy processors to invest in new processing of dairy ingredients, which is required for future growth in the dairy industry.

Newly designed dairy barn at the Canadian National Exhibition includes more focus on education and gives visitors an opportunity to engage and learn more about the dairy industry.

Along with a number of other dairy operations producing biogas for electrical generation, Stanton Farms, of Ilderton, later became the first dairy farm to supply agriculture-based renewable natural gas in Ontario to Enbridge Gas Distribution network.

Monthly quota calculation is introduced and assumes responsibility by the CMSMC.

DFO assumes the responsibility for developing a promotion program.

2019

The federal government announces $1.75 billion in financial compensation to be distributed to Canadian dairy producers over an eight-year period for the market loss associated with the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) trade agreements.

The federal government releases an updated version of Canada’s Food Guide. Dairy is removed as a category and included as part of the broader protein group, which includes plant-based alternatives to dairy.

First Milk and Cookies campaign “Big Believers”. DFO launches first Milk and Cookies campaign with mass media and donates $500K to Ontario Children’s hospitals, as part of our corporate social responsibility programming.

First Nutritional Campaign — “What Can’t Milk Do?”

In a year of uncertainty, Ontario’s dairy farmers find a way to stabilize and even thrive. It was both challenging and rewarding.

Following the 2020 Spring Policy Conference, a new world of lock downs, remote work, school cancellations, health and safety protocols, supply chain disruptions, and grocery store line-ups.

Global pandemic hits Canada – DFO continues to pick up milk and deliver milk to processors while following protocols. Strong demand for milk in early months of COVID as consumers were staying at home and baking/ preparing more foods at home using dairy ingredients.

The new national P10 Pooling Agreement is a landmark development that will enable the fair sharing of revenues and markets across Canada.

Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) implementing legislation is swiftly approved in the House of Commons and Senate before Parliament of Canada is suspended in response to the COVID-19 global shutdown. Canada is the last of the three signatories to ratify the agreement, though several issues remain to be finalized during the implementation phase. CUSMA, which replaces the North American Free Trade Agreement, includes a calculated 3.9 per cent market access to the Canadian dairy industry, the elimination of milk ingredient Class 7 and export threshold limits on the amount of milk protein concentrate, infant formula and skim milk powder the industry can export.

First Dairy Education Gaming Platform — “DairyCraft.”

Lactanet takes over the responsibility of conducting proAction validations and reviewing self-declarations on behalf of DFO.

First ever post-to-pay Pop Up in Canada — MilkUp.

The government of Canada release their 2022 Fall Economic Statement announcing that it intends to offer dairy producers extra funding of up to $1.2 billion over six years under the Dairy Direct Payment Program to account for the impacts of CUSMA.

Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the content in this timeline; however, no guarantees are made regarding its completeness, correctness, or timeliness. Sources of information include, but not limited to, previous Milk Producer editions and Dairy Farmers of Ontario (DFO) annual reports, DFO 60th anniversary commemorative book, and DFO staff. The contributors and publisher disclaim any liability for any errors or omissions and accept no responsibility for any loss or damage that may arise from reliance on the information provided.

CUSMA first dairy TRQ panel — final public report is made public on January 4th. On May 16th, Canada published new CUSMA dairy TRQ allocation and administration policies. The new policies end the use of processor-specific pool, addressing the Panel’s finding that it was inconsistent with the agreement.

First logo ever on the Toronto Maple Leafs’ Sweater. The “milk” logo becomes the first brand to appear on the iconic Toronto Maple Leafs sweater, building on the two organizations' multi-year partnership to support healthy active living, community programming and access to hockey for players and fans everywhere.

The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair celebrates its 100th anniversary. DFO is one of the title sponsors.

First Milk Fan Zone at the Ottawa Senators Arena — Joining forces with the Ottawa Senators results in many innovative marketing executions: a Milk-branded soft-serve ice-cream and chocolate milk stand, Milk-branded penalty box, and our very own Milk Zone.

Milk Masters — First Culinary Cooking Competition is launched, highlighting milk’s irreplaceability and delicious taste.

CUSMA second dairy TRQ panel — final public report is made public on November 24. All four principal categories of claims made by the U.S. are rejected by the panel.

2023/24 school year is successful with 46 educators visiting 1,003 schools, delivering 8,624 engagements and interacting with 213,319 students. The education team produces 18 new teaching resources.

Federal government launches the Dairy Innovation and Investment Fund on September 29. The fund will provide up to $333 million toward processing investments in new capacity and increase competitiveness. Of the $333 million, $127 million is allocated to Ontario.

DFC’s advocacy efforts help advance Bill C-282, an Act to Amend the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act, which will prohibit the government from negotiating market access concessions in future trade negotiations.

DFO enters a partnership with the Professional Womens Hockey League (PWHL) with both the Toronto Sceptres and the Ottawa Charge.

99 per cent of Ontario producers are registered under proAction.

To maintain the highest standard of milk quality on March 1st, DFO launches Enhanced Sample Testing, which marks a significant advancement in the industry and aims to provide dairy farmers with improved testing and reporting frequency.

2025

We commemorate milestones that tell the story of our collective efforts: 60 years of Dairy Farmers of Ontario and our commitment to dairy excellence, 30 years of Dairy Education programming and 100 years of Milk Producer magazine.

The Werry family of Loa-De-Mede Farms has spent over a century blending innovation, tradition and community commitment to grow a thriving multigenerational dairy operation just outside Oshawa, Ont.

By Jeanine Moyer

AS ONE OF ONTARIO’S LONGEST-STANDING DAIRY FARM FAMILIES, the Werry’s of Oshawa, Ont. embody the evolution of the dairy industry itself – living proof of how dedication, resilience, a commitment to succession planning, and a deep-rooted passion for farming can thrive through generations of change.

Clarence Werry founded Loa-De-Mede Farms in 1922 after buying the farm from his uncle. Since then, four generations of the Werry family have built on each other’s successes to become what it is today, a progressive Ontario dairy farm.

Today, Loa-De-Mede Farms Ltd. is managed by a father and son team, Dennis and John, along with their wives, Cindy and Heather. Due to urban sprawl, the farm moved locations in 2015, to a new facility just north of the original home farm where they are now protected inside the greenbelt.

The family milks 75 cows with two GEA robots in a compost bedded pack barn and manage 400 acres of field crops.

It’s always a pleasure to work with the Werry family, whose dedication to excellence shines in everything they do. Known for being progressive leaders in the industry, they consistently go above and beyond to ensure their farm is clean, efficient and in top shape. Their legacy of breeding exceptional cows speaks volumes about their commitment and passion for dairy farming. The Werry's have every reason to be proud of their success, and it's inspiring to see how their hard work and innovation continue to set a standard for others.

– Blythe Mackie, FSR

Innovation through generations

“We’re fortunate to have a long line of innovators in our family,” says John Werry, great-grandson of Clarence. During the 1930s, Clarence helped start the Ideal Dairy processing co-operative in Oshawa. In 1952, he installed one of the first bulk milk tanks in Canada. This changed the

way the Werry family, along with many others, shipped milk, and the transition from milk cans carried by horse drawn wagons meant more milk could reach more consumers.

John’s grandfather, Bill Werry, inherited the farm from Clarence and quickly earned a reputation for pioneering soil conservation techniques. He introduced strip tillage on the farm’s rolling fields – a forward-thinking move that significantly reduced soil erosion. Bill’s innovative approach drew widespread attention, even inspiring bus tours of fellow farmers eager to learn from his methods.

Bill had four sons, and for four decades the brothers farmed together until they had enough of the encroaching pressure of the surrounding city. That’s why, in 2015, some of the brothers retired, leaving Dennis and John to form a new multigeneration Werry partnership and move the cows to a new farm location away from the city fringe.

“I missed out on milking cows by hand, but I’ve done it every other way,” quips Dennis, reflecting on the multitude of changes the farm has seen in technology and innovations throughout the recent decades. In fact, like many other Ontario dairy farms, the Werry’s changed their milking systems over the years, switching from a tie stall set up, to a parlour and then to robots as new technology became available. “I’m proud that we’ve kept our farm’s Loa-De-Mede prefix and business structure through the family and farm location transition. Loa-De-Mede is Cornish for low meadows. The name was brought from England with the original settlers of the home farm and has stayed with the farm. We’ve made a lot of changes over the years, but we maintain our spirit and success as dairy farmers,” he says.

Tradition with a vision

Generations of the Werry family have been involved in the 4-H program, and have enjoyed showcasing their animals in the show ring.

The Werry family roots run deep within Ontario’s dairy industry. In addition to the family branch that created Loa-De-Mede Farms, two other arms of the family continue to milk cows today, including Werrcroft Farms and Loka Holsteins.

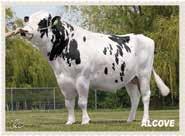

Over the years, the family has also achieved countless accolades for their commitment to dairy farming and herd genetics, including nine All-Canadian nominations in the last three years and regional herd management awards. John notes that the family also sets a goal to achieve the milk quality gold seal every year.

"Hard work pays off, and sharing the positive results with family makes it even better," says John.

The family’s accomplishments, combined with their close proximity to the city, an international airport and the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair, means that they regularly attract visitors and bus tours.

“We’re the first dairy farm you reach when you drive out of the city,” says Heather, explaining that over the years their family farm has hosted public tours from schools, retirement homes, scouting groups, along with 4-H clubs and events.

Given their unique location, the farm has been exposed to a steady flow of traffic, and with that can come public scrutiny. The Werry family has always been ahead of their time, maintaining a tidy farm –inside and outside the farm buildings. “Welcoming people to our farm has and continues to be a tradition we are proud of,” says Dennis, recalling stories about his grandfather hosting visitors and noting how neighbours loved to visit the farm because it was well-kept, and one of the first homes that offered indoor plumbing in the area.

Community involvement is also another family tradition the Werry’s are passionate about. Dennis’ father, Bill, was involved with Boy Scouts, dedicating nearly half his life to volunteering with the organization.

Over the years, Dennis has committed his time to the dairy industry, volunteering with Holstein Canada, Holstein Ontario, along with local county clubs. Multiple family members have also been 4-H members, leaders and volunteers, and have been invested in supporting future generations of rural leaders.

Clarence Werry was a pioneer among Ontario dairy farmers, installing one of the first milk tanks in Canada. This helped him get dairy onto more tables across Ontario.

Now his great-grandson is continuing that same family legacy, producing high-quality local milk for Oshawa and the rest of Ontario.

I hope our industry can keep family farms like ours sustainable and profitable because dairy farming in Ontario is a rewarding lifestyle.

— John Werry

The family has also been a long-time supporter of local agricultural societies and fairs in the area. Right now, John and Heather are spending their spare time supporting the next generation of their family by volunteering with local minor hockey teams, school events and their local dairy producer committee.

Paige and Tate, John and Heather’s children, represent the fifth generation of the Werry family to be raised on the Oshawa dairy farm. They are both involved in the farm, and like generations of their family before them, they share an appreciation for the unique and rewarding lifestyle the family dairy farm provides.

“A family farm is never really yours to sell,” says John, explaining his outlook on maintaining and building on the family legacy. “We are always expanding with the hope the farm will carry on to the next generation, but this life requires a deep commitment and love for what we do.”

Both John and Heather have made it clear there is no pressure for their children to continue with the family farm legacy, saying they are grateful the option is available, but it must be a choice their kids make for themselves.

For now, Dennis and John are happy to work together as the third and fourth generations of the family. They continue to upgrade their technology, herd management and cropping practices as new technologies and innovations become available. The switch to robotic milking has been a game-changer for them, increasing flexibility and eliminating the need to rely on outside labour. They also outsource a significant amount of field work to multiple custom operators, including fellow dairy farmer and custom operator, Parbro Farms. This management transition has reduced the reliance on labour and capital investments in equipment.

“There’s tremendous value in partnerships,” says Dennis, pointing out the changes from relying solely on family labour to outsourcing tasks and responsibilities to technology and business suppliers that have evolved throughout the generations and recent decades.

The Werry family roots run deep within Ontario’s dairy industry. In addition to the family branch that created Loa-De-Mede Farms, two other arms of the family continue to milk cows today, including Werrcroft Farms and Loka Holsteins, and a fourth branch of the Werry family dairy legacy is involved in breeding and showing dairy cattle under the Werrhurst prefix.

Reflecting on the scope of changes his family has experienced on the farm, John states that he’s most grateful for the ability to continue the tradition of dairy farming at a similar size and scale as his predecessors. “I hope our industry can keep family farms like ours sustainable and profitable because dairy farming in Ontario is a rewarding lifestyle,” he says.

By Sean Tarry

IN A RAPIDLY EVOLVING WORLD IN WHICH MOST BUSINESSES are driven to consistently pivot in response to shifting market demands, tradition is often neglected and ignored. Yet nestled in the heart of Campbellford, Ont., Empire Cheese has not only endured for nearly 150 years, it has flourished, thanks in large part to its steadfast commitment to traditional cheese-making and its deep roots within the local agricultural community.

Founded in the late 1870s, the original Empire Cheese Factory was built on the farm of John Haig, who also served as its first cheesemaker. From these modest beginnings, the company has undergone significant transformations, but never at the expense of the traditions that shaped its foundation.

By the mid-20th century, Empire had become a fixture in the local dairy economy. In 1953, following the devastating fire that consumed the Kimberley Cheese Factory, Empire and Kimberley amalgamated to form what is now the Empire Cheese & Butter Co-operative. That same year, a new factory was constructed, with Les Shillinglaw as head cheesemaker — continuing a legacy of artisanal craftsmanship passed down through generations. Les was succeeded by Don Pollock, and today, the cheese-making baton rests in the capable hands of Mark Erwin.

“Empire has throughout its history remained dedicated to preserving the things that helped establish the company nearly 150 years ago,” says company representative, Vicki McMillan. “The quality of our product is a result of time-honoured cheese making traditions that we still adhere to today. And, what’s more, we don’t add any artificial flavour or additives to enhance the flavour, with all of our cheese aged naturally.”

Empire Cheese is now the only cheese manufacturing facility in Northumberland County and the first one located east of Toronto. Operated as a co-operative, it is owned by local dairy farmers who elect a Board of Directors annually to guide the company's direction — a model that emphasizes community involvement and shared success.

What sets Empire apart from larger, industrial producers is its unwavering dedication to making cheese the old-fashioned way. Cheese is still crafted in open-style vats using only whole milk, microbial enzyme instead of rennet, and natural ingredients. No preservatives, no artificial flavours — just pure, authentic cheese.

Today, Empire's products can be found throughout Ontario at local farmers’ markets and retail outlets. Their factory store has become a destination in itself, offering not just cheese but curated gift baskets featuring local delicacies like jams, honey and candy.

Empire has throughout its history remained dedicated to preserving the things that helped establish the company nearly 150 years ago. The quality of our product is a result of time-honoured cheese making traditions that we still adhere to today.

Balancing tradition with modern needs

Despite its nostalgic approach, Empire Cheese isn’t stuck in the past. The company has made concerted efforts to integrate modern efficiencies into its operations. They are HACCP registered, a recognition of their adherence to the highest food safety standards, and have recently implemented new software to improve process flow, inventory control and overall efficiency.

But staying competitive in today's market is no easy feat. The very values that define Empire — small-batch quality, hand-crafted products and local ownership — also create unique challenges, particularly when it comes to production costs and attracting skilled labour.

“The most significant trend currently impacting our business and opportunities for continued growth and success is the state of the economy,” McMillan explains. “Unfortunately, our processes and commitment to the highest standards of quality lends itself to a higher cost of production.”

And when it comes to staffing, Empire faces another uphill battle. “The shortage of skilled labour is always a problem for businesses looking to sustain success and growth,” she says. “But that challenge seems amplified for us because of the way we do things.”

Yet, in the face of adversity, the Empire Cheese Co-op continues to move forward with purpose. This past winter, the company completed a remodel of its factory store and is now expanding parking and greenspace to better accommodate visitors and bus tour groups. The aim is to enhance the factory’s role not just as a producer, but as a tourist destination and community hub.

“The Board of Directors is dedicated to ensuring the company thrives into the future,” McMillan affirms. “We’re always working on ways to improve while staying true to the traditions that have made Empire what it is.”

From a single vat on a family farm to a community-run co-op with province-wide reach, Empire Cheese’s story is one of dedication, craftsmanship and commitment — proving that sometimes, the best way forward is to look back and honour the past.

Where the science of nutrition meets accurate feeding for a sustainable future

The Franco-Ontarian manufacturer of cheese continues growing its legacy as a leader within the industry

By Sean Tarry

IN THE COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE OF CANADIAN DAIRY, where large processors dominate and niche players jostle for shelf space, few companies can claim the heritage, community support, and cross-cultural appeal of St. Albert Cheese Co-op Inc. For more than a century, this Eastern Ontario-based cooperative has not only survived — it has thrived — by staying true to its roots and maintaining its unwavering commitment to traditional cheesemaking methods.

Established on January 8, 1894, the original St. Albert Cheese Factory was the vision of founding president, Louis Génier and his nine partners. Little did they know their small enterprise would become one of Canada’s oldest cooperatives and an iconic institution in the region. Known originally as Cheese Factory #743, the co-op began shaping the identity of the surrounding village from the moment it opened its doors.

“We’re sort of a hybrid company,” says Eric Leveille, Business Development Director at St. Albert Cheese Co-op. “Because we’re a Franco-Ontarian company, we serve a significant portion of the market in Eastern Ontario, as well as the western part of Quebec. That dual identity has always given us a unique perspective and allowed us to connect deeply with customers in both provinces.”

Like many long-standing institutions, St. Albert has had its share of trials. In 1931, the factory was sold to a private owner, only to be bought back by

its members in 1939 for $8,500 — a move that reestablished it as a true cooperative enterprise. The new era led to the construction of a modern facility in 1950, marking a turning point in production and community impact.

That community spirit has defined St. Albert for generations. When the co-op celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1994, it did so with many festivities and a commemorative book — Souvenances de la Fromagerie #743. Successes were celebrated again in 2019, with their 125th anniversary.

But perhaps the greatest test of St. Albert’s strength came in 2013, when the factory was devastated by a fire. In a moment of profound crisis, the surrounding community stepped in to help the company rise from the ashes — literally. "When the fire destroyed the building, the entire community of St. Albert lent their support in whatever way they could,” says Leveille. “The elementary school opened its classrooms, the presbytery provided meeting rooms, and every-

In 2014, as the Co-operative was ready to mark its 120th anniversary, it emerged from its ashes, stronger than ever, with modern facilities, increased production capacity and an iron will, with but one goal in mind: to continue the tradition by producing the best cheddars and dairy products in the country.

one pitched in. There’s not much in St. Albert — barely anyone lives here — but every single person contributed something to help us rebuild.”

Within two years, on February 3, 2015, a new, state-of-the-art facility opened its doors. It was a rebirth rooted in resilience, made possible by cooperation, determination and the deep loyalty of St. Albert’s supporters.

Through it all, the guiding principle of St. Albert Cheese Co-op has been quality. The co-op is now Canada’s largest producer of cheddar cheese curds, and its products are found in over 2,000 points of sale across Ontario and Quebec — and increasingly across the country.

“We still make thermized cheddar,” Leveille explains, “a process using milk heated just below pasteurization. It’s a technique that requires skill and precision, and there are only a few of us left in Canada still doing it. That’s the kind of tradition we’re proud to maintain.”

This dedication to old-world methods has earned St. Albert numerous accolades, including awards from the Toronto Winter Fair, Spencerville Fair, the British Empire Cheese Show, and the Canadian Cheese Grand Prix.

Today, the co-op employs more than 200 people and remains grounded in the principles established by its founders: integrity, craftsmanship and cooperation.

“The company has thrived, and continues to thrive, as a result of the way we see the world,” Leveille says. “Above everything else, St. Albert wants to make sure that the cheese we produce continues to be as good as it’s been throughout our history.”

As competitors yield to cost pressures and mass production, St. Albert Cheese Co-op stands firm in its identity — a cooperative with a conscience, a craftsman’s touch and a community behind it. For 131 years and counting, it has proven that tradition, when respected and nurtured, can be a powerful foundation for innovation, growth and enduring success.

By Jeanine Moyer

CANADIAN DAIRY GENETICS HAVE ADVANCED IN LEAPS AND BOUNDS over the past century. It’s hard to point to one innovation that’s made the greatest contribution, but rather it’s been a combination of achievements and milestones that have shaped the industry to what it is today – a global genetic powerhouse.

“The ability for farmers to adopt and implement new breeding methods has contributed to the superior herd genetics we have here in Canada today, and our respected reputation around the world as global leaders,” says Jamie Howard, sales director at EastGen Inc., noting one of the greatest changes over the decades has been the increasing accessibility of genetic advancements and innovations to Canadian dairy farmers and breeders.

Brian O’Connor, general manager of EastGen Inc. believes that every milestone through the genetic journey has been utilized and adopted into Canadian dairy farms to deliver individual advancements for each herd. “Genetics are one of the key components to production, and when combined with good nutrition and herd management, producers have been able to accelerate the genetic potential of Canada’s dairy herd,” he says.

Here’s a look at five key milestones that have shaped the dairy genetics industry in Canada and contributed to the rapid increase of genetic improvement.

Frozen semen was first commercialized in 1953 in Canada, opening doors to new genetic potential and innovations on farms.

“The ability to freeze and transport semen broadly is arguably one of the most significant achievements because it made genetic improvement easily accessible to dairy producers,” says Howard.

Utilizing the ability to collect and freeze semen from young bulls with high genetic promise and breed them to multiply offspring enabled the industry to increase the speed and reliability of genetic progress in Canada and around the world.

The capacity to produce more daughters across more herds allowed the industry to identify high reliability proven young bulls. Assessing the daughters of these bulls (using information like milk recording and classifications) provided remarkable reliability to the sire genetics, adding proof and confidence of sire performance.

“The resulting higher reliability of proven bulls and the development of young sire indexes allowed AI co-ops to find and identify younger genetics and prove their performance,” explains O’Connor. “The result was faster, more reliable genetic progress across Canada and the world. Leveraging this new ability to prove young sires was a significant step along Canada’s journey to becoming an international dairy genetic powerhouse.”

This genetic milestone and the resulting data also led to the development of advanced genetic evaluation modeling by the University of Guelph. Throughout the 1960s to the 1990s, the University of Guelph became a world leader in the field of developing evaluations and creating sire rankings that directly served to help producers make genetic rankings and decisions to progress their herds. O’Connor notes that during this period of genetic advancements, the University of Guelph also worked alongside farmer genetic co-ops in Canada to share the benefits of daughter and progeny proving to help the industry make accurate genetic evaluations and compare bulls.

Thanks to the advancements in progeny proving and the focus on evaluating and selecting sires, the male side of the genetics equation was advancing at a rapid pace in Canada. It wasn’t until embryo transfer was first commercialized in 1972 that the focus shifted to speed up the enhancement of female genetics.

Embryo transfer allowed producers to multiply the offspring of their top cows and speed up genetic results within a herd. This technology also allowed exports of frozen embryos, opening up additional revenue streams for producers and breeders.

In vitro fertilization was commercialized in the late 1990s thanks to Boviteq, accelerating female genetic improvements even faster.

“We’ve made extraordinary improvements through in vitro that have allowed our industry to reduce genetic intervals significantly,” notes O’Connor, explaining that this technology has advanced so far that today, it is possible to take a genetic biopsy of an embryo to accurately identify the genetics and sex of a calf before it is born.

Sexed semen was first commercialized in the U.S. in 2003 by Sexing Technologies (ST). Since then, this genetic innovation has been a game changer for dairy producers and has quickly become the basis of many breeding decisions. Sexed semen allows producers to breed their top performing females to produce daughters that are collapsing genetic generations and enhancing cow performance and efficiencies. The ability to select gender has also increased beef on dairy breeding that is opening new revenue streams for producers too.

“Genomics have accelerated traditional progeny proving, creating a new era for bull ‘proofs’ that is delivering higher reliability and more confidence for producers making genetic decisions,” says O’Connor.

The ability to reliably calculate the performance of younger bulls thanks to DNA testing is changing the way producers make breeding decisions, like selecting the highest performing animals to accelerate genetic gain within their herds.

The ability to reliably calculate the performance of younger bulls thanks to DNA testing is changing the way producers make breeding decisions, like selecting the highest performing animals to accelerate genetic gain within their herds.

– Mark Carson

A legacy of innovation

“The vision of our Canadian dairy producer forefathers continues to benefit the industry significantly,” says O’Connor, noting that it’s thanks to the more than 20 genetics and artificial insemination (AI) producer owned co-ops that were formed across Canada between the 1940s and 1960s that shaped our country’s genetic improvement journey.

Mark Carson, genetic solutions manager with Semex points out that the individuality of every Canadian dairy farm means that every producer can leverage any or all of these technologies and innovations to build the best genetics that fit their operation and management system.

“Today, we have the ability to tailor our herd genetics to fit our climate, barns, feed conditions, on-farm technology, and surrounding environments that are unique to every province

and individual farm,” he explains. “And that’s pretty amazing.”

Genetic enhancement has also allowed producers to deliver more milk with fewer animals that has ultimately improved efficiencies in milk production, feed requirements, inputs, and the overall environmental footprint of the Canadian dairy industry.

“We’ve come a long way in advancing the production of such a superior milk product,” says Howard, noting that the past 100 years of genetic evolution in Canada has enabled dairy farmers to produce the most valuable, safe and nutritious milk products more efficiently than ever before. “There have been so many people over the years that have contributed, and I’m so grateful to be a part of this amazing industry.”

By Jeanine Moyer

From sexed semen to DNA testing, the last few decades have brought game-changing advances in dairy genetics – and the momentum isn’t slowing down. In fact, for some early adopters, the “future” is already part of their herd management, thanks to cutting-edge technology and smart breeding strategies that are reshaping dairy herds across Canada.

Behind these breakthroughs are dedicated individuals who’ve spent their careers turning genetic innovations into practical results on the ground. Mark Carson, genetic solutions manager with Semex, Jamie Howard, sales director at EastGen Inc., and Brian O’Connor, general manager of EastGen Inc. share their take where things are headed next – what to expect, what to get ready for and what could change how we think about breeding in the years ahead.

Embryo transfer is already in use on Canadian dairy farms and is expected to grow, especially with the rise of in vitro fertilization (IVF). By selecting topperforming females and replicating their genetics through IVF, farmers will be able to accelerate the improvement of female genetics in their herds at a faster pace.

Data collected on Canadian dairy farms is giving farmers powerful new tools for smarter genetic and herd management decisions. As robotic technology becomes more common, new types of data are predicted to emerge, paving the way for artificial intelligence to support genetic modeling and production forecasting in the near future.

Thanks to Immunity+, incorporating health traits into genetic decisions is a reality today. What’s expected to change is the increased focus on boosting dairy herds' natural disease resistance, recovery and immune response with the wider adoption of this genetic innovation. Healthier cows mean better fertility, higher productivity, greater efficiency, and longer-lasting animals.

Genomic testing, already common on Canadian dairy farms, is set to grow. By using DNA insights to add more precision to breeding and management decisions, farms can enhance the speed and reliability of their progress – and this trend shows no signs of slowing down.

Polled genes are already being widely adopted on Canadian dairy farms. Incorporating polled genetics into dairy herds not only improves the welfare and well-being of the animals by eliminating the need to dehorn cattle but also reduces labour requirements and increases farm worker safety.

For years, researchers have been digging deeper into the real power of milk – not just as a source of nutrition, but as a valuable contributor to human health. By understanding what’s in milk and how it impacts health, farmers can play a key role in producing milk tailored to tomorrow’s health-conscious market – meeting consumer demand and marketplace needs.

To meet the stronger demand for fresh dairy products in the fall, specifically yogurt and fresh cheese, the P5 Boards announce one additional incentive day to be issued on a non-cumulative basis in each of the months of August and September for conventional producers. Organic producers are issued one additional incentive day on a non-cumulative basis in September. This adjustment aims to maintain the production level forecasted for the period.

The P5 provincial boards’ primary objective is to continuously monitor the milk market situation and meet demand in the most optimal way and will continue to adapt production signals to address market changes, as required.