CLINICAL

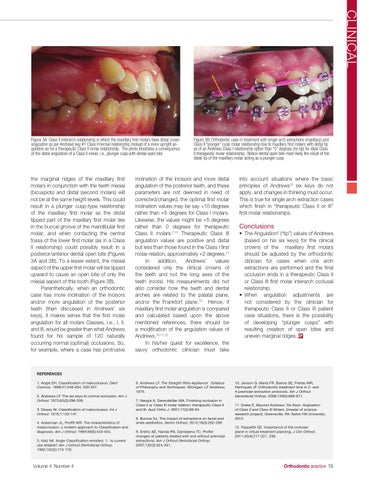

Figure 3A: Class II interarch relationship in which the maxillary first molars have distal crown angulation as per Andrews key #1 Class I/normal relationship instead of a more upright angulation as for a therapeutic Class II molar relationship. The photo illustrates a consequence of the distal angulation of a Class II molar; i.e., plunger cusp with dental open bite

the marginal ridges of the maxillary first molars in conjunction with the teeth mesial (bicuspids) and distal (second molars) will not be at the same height levels. This could result in a plunger cusp-type relationship of the maxillary first molar as the distal tipped part of the maxillary first molar lies in the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar, and when contacting the central fossa of the lower first molar (as in a Class II relationship) could possibly result in a posterior/anterior dental open bite (Figures 3A and 3B). To a lesser extent, the mesial aspect of the upper first molar will be tipped upward to cause an open bite of only the mesial aspect of this tooth (Figure 3B). Parenthetically, when an orthodontic case has more inclination of the incisors and/or more angulation of the posterior teeth (then discussed in Andrews’ six keys), it makes sense that the first molar angulation for all molars Classes, i.e., I, II, and III, would be greater than what Andrews found for his sample of 120 naturally occurring normal (optimal) occlusions. So, for example, where a case has protrusive

Figure 3B: Orthodontic case in treatment with single arch extractions (maxillary) and Class II “plunger” cusp molar relationship due to maxillary first molars with distal tip as of an Andrews Class I relationship rather than “0” degrees (no tip) for ideal Class II therapeutic molar relationship. Notice dental open bite most likely the result of the distal tip of the maxillary molar acting as a plunger cusp

inclination of the incisors and more distal angulation of the posterior teeth, and these parameters are not deemed in need of corrected/changed, the optimal first molar inclination values may be say +10 degrees rather than +5 degrees for Class I molars. Likewise, the values might be +5 degrees rather than 0 degrees for therapeutic Class II molars.7,11 Therapeutic Class III angulation values are positive and distal but less than those found in the Class I first molar relation, approximately +2 degrees.11 In addition, Andrews’ values considered only the clinical crowns of the teeth and not the long axes of the teeth (roots). His measurements did not also consider how the teeth and dental arches are related to the palatal plane, and/or the Frankfort plane.12 Hence, if maxillary first molar angulation is compared and calculated based upon the above mentioned references, there should be a modification of the angulation values of Andrews.10,11,12 In his/her quest for excellence, the savvy orthodontic clinician must take

into account situations where the basic principles of Andrews’2 six keys do not apply, and changes in thinking must occur. This is true for single arch extraction cases which finish in “therapeutic Class II or III” first molar relationships.

Conclusions • The Angulation2 (“tip”) values of Andrews (based on his six keys) for the clinical crowns of the maxillary first molars should be adjusted by the orthodontic clinician for cases when one arch extractions are performed and the final occlusion ends in a therapeutic Class II or Class III first molar interarch occlusal relationship. • When angulation adjustments are not considered by the clinician for therapeutic Class II or Class III patient case situations, there is the possibility of developing “plunger cusps” with resulting creation of open bites and uneven marginal ridges. OP

References 1. Angle EH. Classification of malocclusion. Dent Cosmos. 1899;41:248-264, 350-357. 2. Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am J Orthod. 1972;62(3):296-309. 3. Dewey M. Classification of malocclusion. Int J Orthod. 1915;1:133-147. 4. Ackerman JL, Proffit WR. The characteristics of malocclusion: a modern approach to Classification and diagnosis. Am J Orthod. 1969;56(5):443-454. 5. Katz MI. Angle Classification revisited. 1: Is current use reliable? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102(2):173-179.

Volume 4 Number 4

6. Andrews LF. The Straight-Wire Appliance: Syllabus of Philosophy and Techniques. Michigan: LF Andrews; 1975. 7. Nangia A, Darendelilier MA. Finishing occlusion in Class II or Class III molar relation: therapeutic Class II and III. Aust Ortho J. 2001;17(2):89-94. 8. Burrow SJ. The impact of extractions on facial and smile aesthetics. Semin Orthod. 2012;18(3):202-209. 9. Erdinc AE, Nanda RS, Dandajena TC. Profile changes of patients treated with and without premolar extractions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(3):324-331.

10. Janson G, Maria FR, Barros SE, Freitas MR, Henriques JF. Orthodontic treatment time in 2- and 4-premolar-extraction protocols. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5):666-671. 11. Drake E. Beyond Andrews’ Six Keys: Angluation of Class II and Class III Molars. [master of science research project]. Greensville, PA: Seton Hill University; 2012. 12. Paquette DE. Importance of the occlusal plane in virtual treatment planning. J Clin Orthod. 2011;45(4);217-221, 236.

Orthodontic practice 15