A dissertation aiming to dissect futurist architects influence on cinematic sequences through control of structure on film sets and the metaphoric influence of societies social issues, within the last century, on futurist cinema.

Matthew Coyne

Tutor - Sarah Mills

Architectural Context

C3588555

Word Count: 6245

How has futurist architecture been used as a tool to manipulate and enhance sequencing in cinema? Since the idea of film became a commodity to the population, directors and artists have tried bringing fantasy to almost reality. This began during the futurist revolution in the early twentieth century, when artist began to express their predictions of what may be, depicted in a manner of their choosing. Many architects who found solace in futurism began to push the boundaries of reality to break the societal norms of the current day and build a world like no other. Futurist ideals appear as though they are divided. One side of this vision saw the current society progressing towards a cold brutalist future in which structure is king and space is a luxury, whereas the other half held fascinations with speed and aerodynamics with a desire to produce forms that work in addition with nature to produce a new world partnership between the person, the building and the atmosphere. These two sides can be considered utopian and dystopian. However, both can

be seen to be heavily influenced by architecture and the role it will play in creating the new world. Architecture can be the powerhouse behind the futurist ideologies as it allows for the viewer to become immersed in the environment and creates a better understanding of the space along with a more relatable impression (James Stevens Curl, 2018).

The medium of cinema allowed architects to begin exploring how it would feel to be within a utopian or dystopian society. By using sets and stages the sequence of film can be manipulated, the field of view can be distorted or directed by the context it is performed in. Works from Fritz lang during the 1920s does this through its use of narrowing spaces and exaggerated halls, allowing for the scene to feel compact and intense or freeing and calming yet almost daunting. In doing these architectural producers and designers began to re-invent cinema as a process to pull the viewers in to become more than just an element of the third person. Two ways in which they did this were, architecturally constructing

rooms and or spaces that were not too dissimilar from that of the real world, allowing for the viewer to relate to what they are seeing, as discussed briefly above. The second being the magnification and exaggeration of current (to the time in which filmed) social issues such as class hierarchy or racial division. Kibwe’s Robots of Brixton, which is later dismantled in this dissertation, is a perfect example of futurist exaggeration of current racial issues in Brixton.

During the production and creation of these spaces artists and architects relied heavily on their ability to express their visions through drawing. The use of sketches gave the futurist the ability to convince the script writers and directors that what they had envisioned could become reality. Within the early stages of cinema sets were created through temporary foreground structures to mimic that in which the actors would be standing, with large canvas paintings in the background creating the illusion of a large city scape or a never-ending horizon. Could it then be considered that the art of cinema must rely on the art of the architect? Due to the

use of foreground structures this then magnifies the importance of architectural influence within the set, meaning the structures must be designed in such a way that the sequence of events does not become broken and disorientated the journey is clear and impactful. The modern interventions of cinema are empowered due to the availability of digital technologies, the use of AI depictions allows for architects to have high resolution images of the scenes they wish to create. In having this the architect can produce mock reality visuals unlocking the ability to predesign the sequences of cinema, giving an unobstructed landscape to mould and control. However, many of the futurist inspired cinema discussed were produced before the development of such technologies. Anton Giulia Bragaglia’s film Thais, filmed in 1917, relied heavily on set design alone therefore relying on the architecture alone. Could it still be the case that for modern cinema architecture plays such a crucial role even with the ability of CGI and other digital rendering software’s?

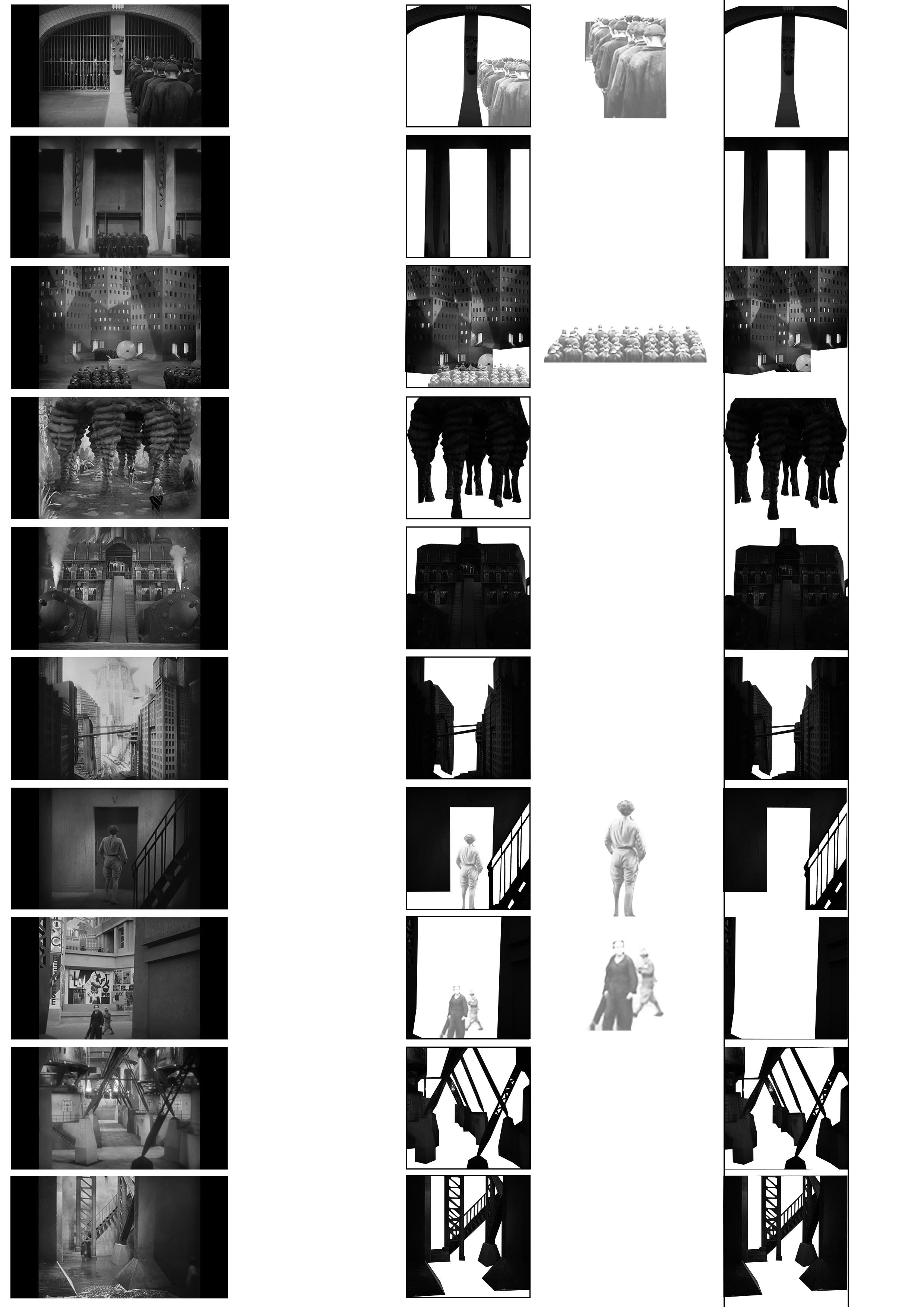

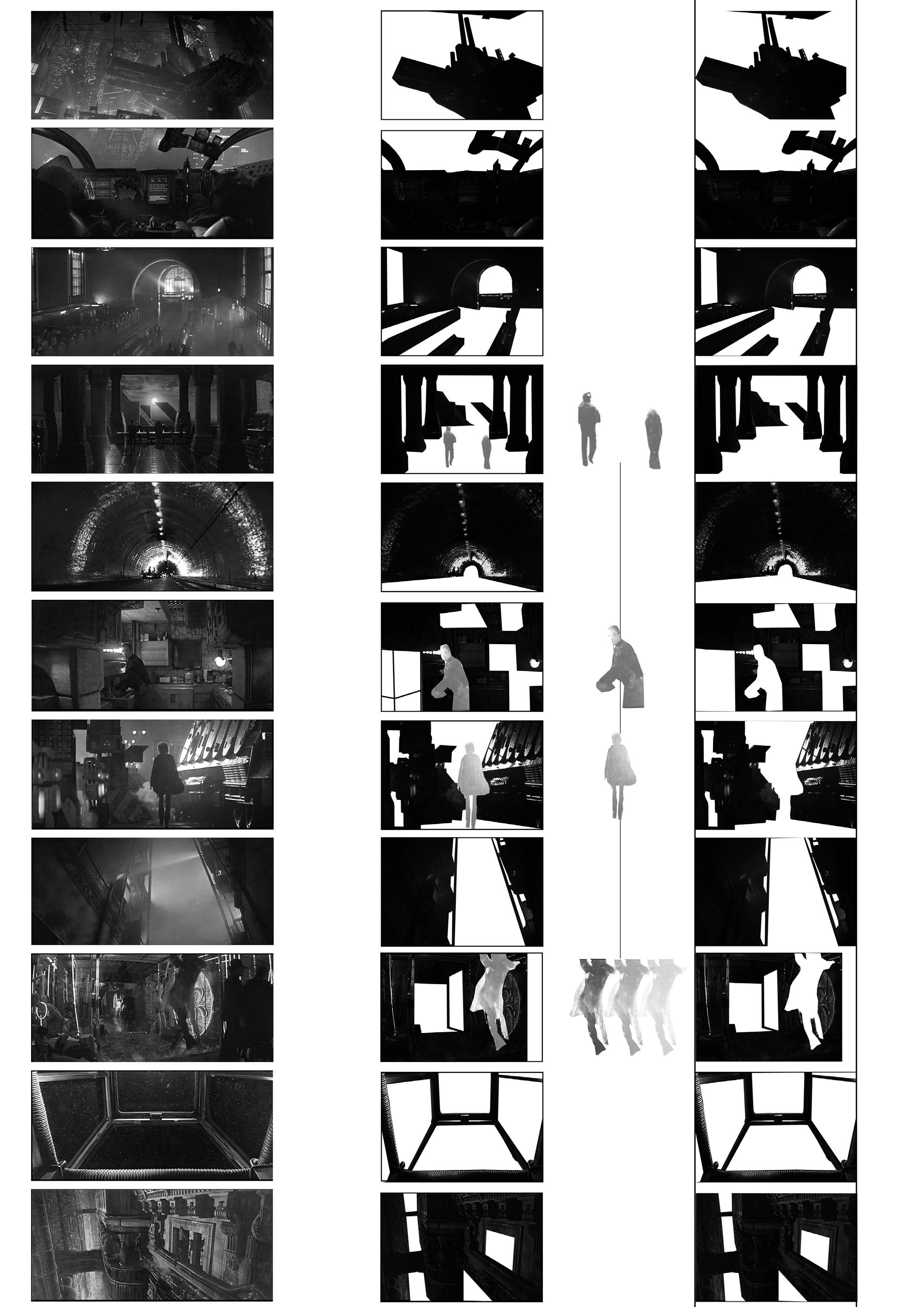

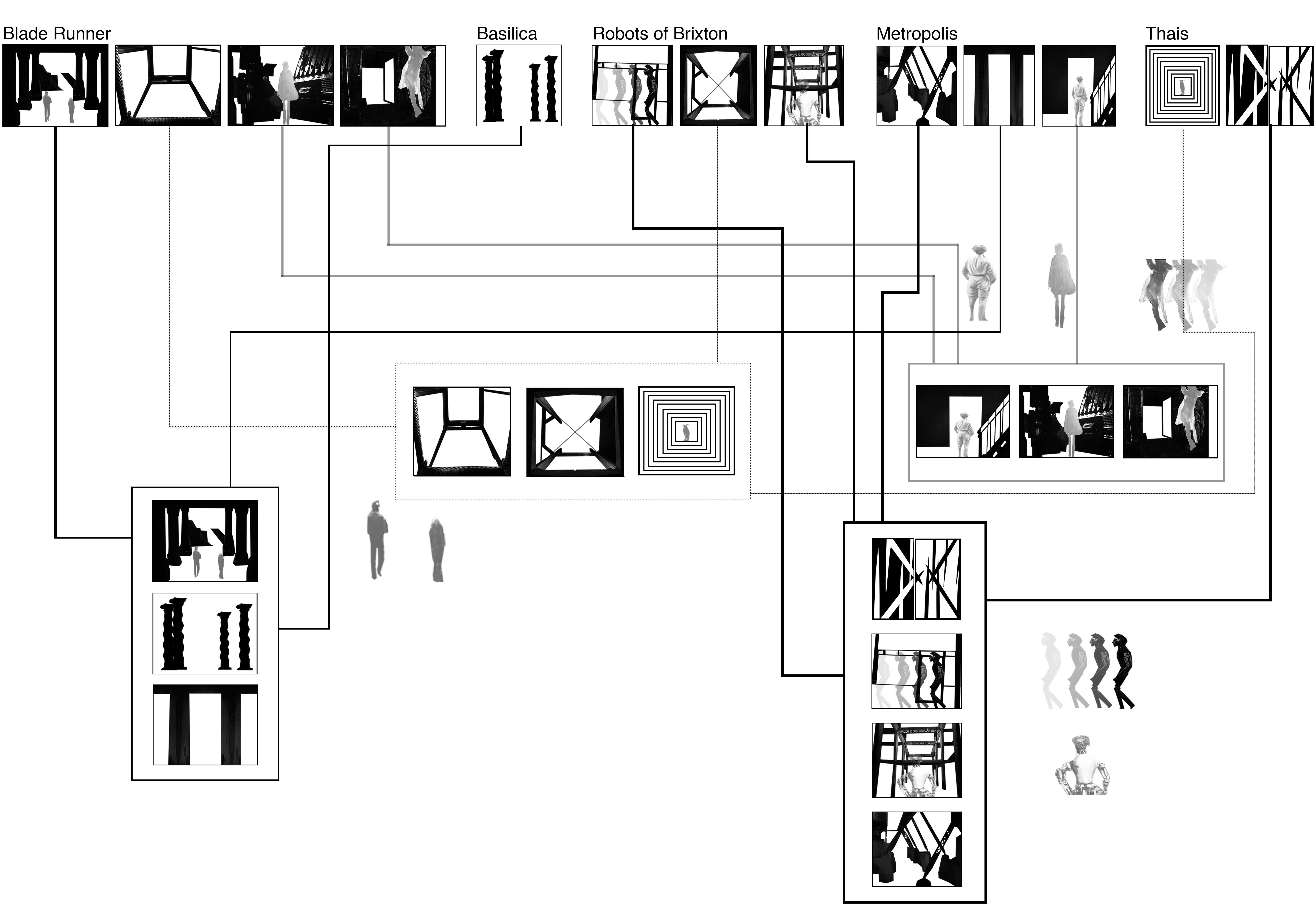

Throughout this dissertation multiple forms of futurist architectural cinema were diagnosed and dismantled to gain a better understanding of how architecture has been used as an influential factor in filmic sequence. By witnessing each form of cinema visible points within each one’s sequence began to appear to heavily involve the architecture surrounding it. This then led into research on sequencing within reality through Carla Molinari’s paper Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces. A fascinating paper aiming to develop and understanding on architecture and how it was manipulated by sequence at its core. It was then possible to compare Molinari’s statements to that of the futurists with the opposing views of the relationship between architecture and sequence. Expanding on this further dissection was done into the different films using noted architect Bernard Tschumis method of mapping sequences. Viewing each film and recording frames in which the architecture becomes an impactful part of the journey. The mapping then

tore the subject from the frame to leave the structures behind leaving visible evidence of sequential manipulation. As a final method of consolidation to the found evidence a comparative combination map was developed finding moments of similar architectural influence between each of the researched cinema.

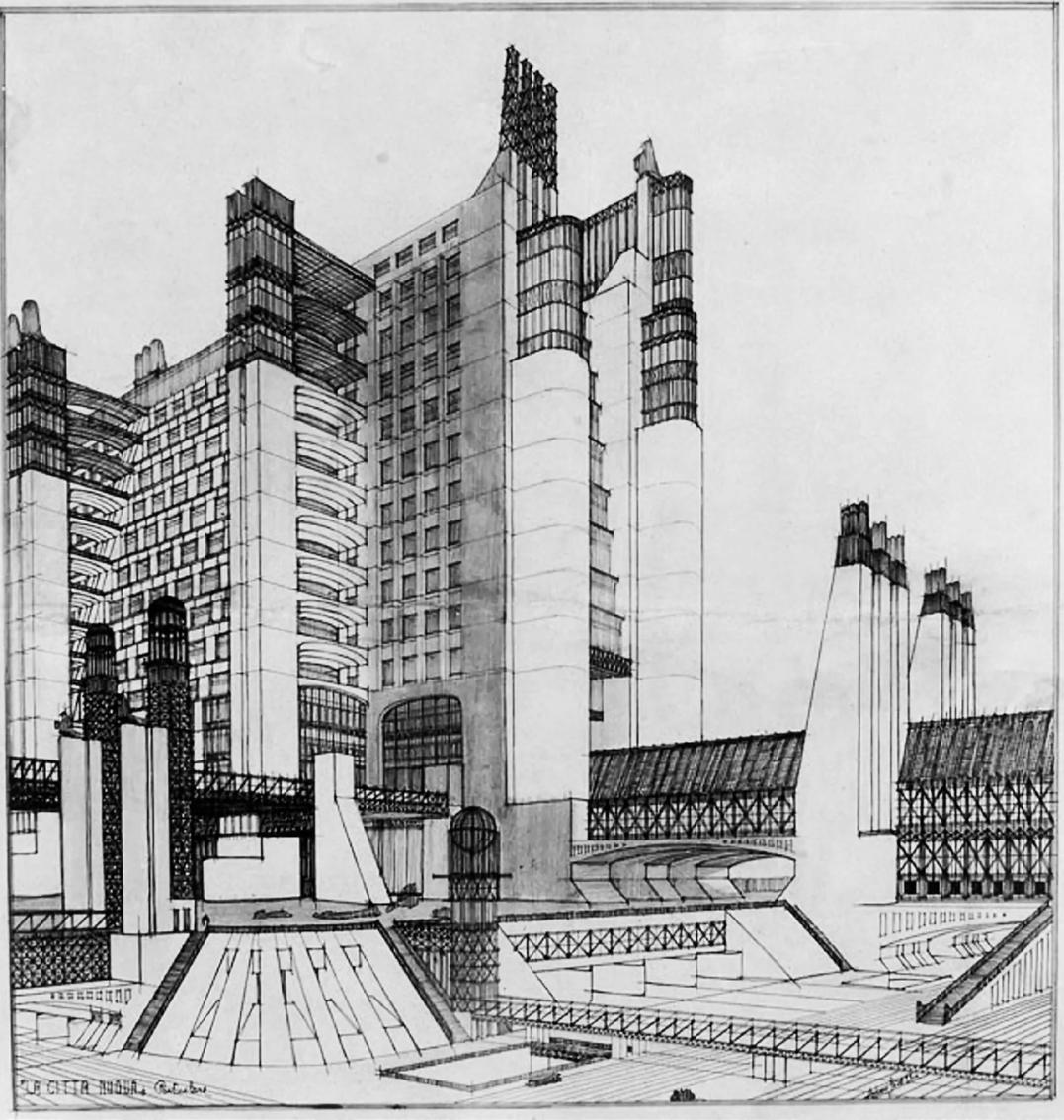

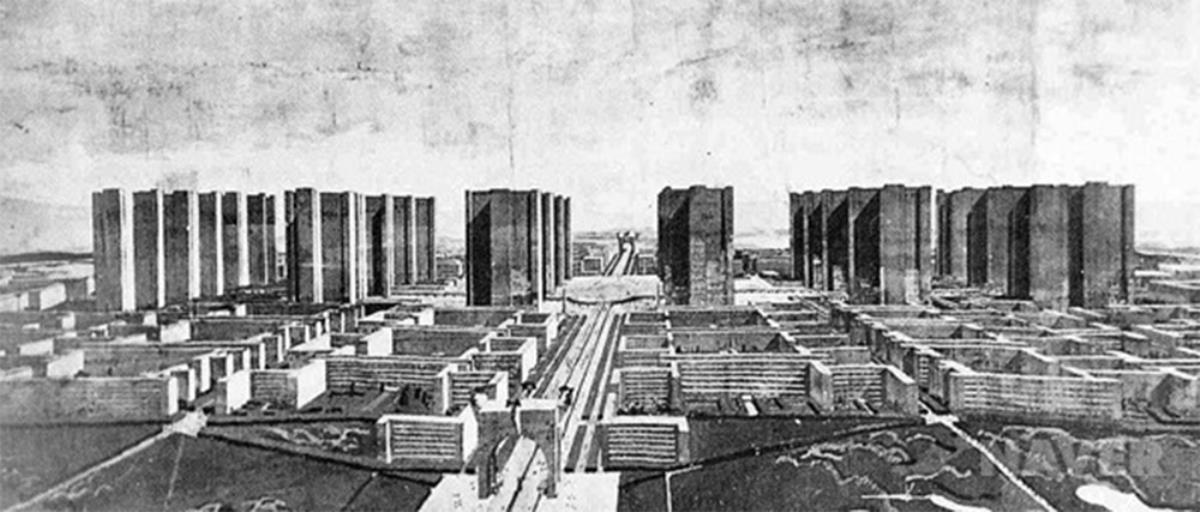

At the turn of the 20th century Italian artists and architects began to form a group solely aiming to define and plan for the new world. Their main aims were to take what is and begin to redefine it in a utopian or a dystopian manner. Using architecture and film allowed for the creation of influential and powerful representations of their view that can still be seen today. By developing moving pictures artists were able to develop more immersive experiences as it was originally considered that photography alone was “Cold” (Luzzi and Carey, 2020). A prime example of this was the reimagining of cities by architect Antonio Sant’Elia in his artwork, Housing with external lifts and connection systems to different street levels from La Città Nuova, 1914 (figure1). Aiming to conceptualise the inhabitation of people into the industrial plain by exaggerating the cities vertically. Sant’Elia’s depictions of the large housing block is a clear example of a dystopian view of the future due to its massiveness, and its lack of coherence with the natural landscape around. Le Corbusier later began to design through

the medium of futurism with his plan for the reimagination of Paris (Ma, 2017). Could Le Corbusier have been right through his reimagination? His aim being to redefine Paris as a utopia or a way of “Looking for a suitable decomposition of a control problem by creating a hierarchal decentralization of the society” this quote demonstrates the idea that the power would become shifted to the community as there would no longer be a single form of control. Architecture allowed this to become reality through the largescale redefinition of current public and private inhabited spaces much like Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin (figure 2 and figure 3) (Mauro and Di Taranto, 1990). Would this have created a brighter more community-based utopia or a darker more solemn dystopia, “Societies and or places worse than the ones we live in” (Moylan and Baccolini, 2013). One could not say for certain whether it would have been a utopia/dystopia due to the conceptual nature of the designs. Would it not then be better to discuss whether the plans would be compatible with nature, or would they become disassociated with it?

Figure 1: Housing with External lifts and Connection Systems, Antonio Sant’Elia (Image has been desaturated)

Figure 2: Model Voisin by Le Corbusier

Figure 3: Render of Voisin by Le Corbusier

Figure 1: Housing with External lifts and Connection Systems, Antonio Sant’Elia (Image has been desaturated)

Figure 2: Model Voisin by Le Corbusier

Figure 3: Render of Voisin by Le Corbusier

In Le Corbusier’s reimaging of Paris, a key visible element is the number of vertical structures emerging in a grid like formation. As mentioned previously, it is interesting to consider how architecture can develop the environmental cues of a utopian/dystopian future. With the use of architecture one can control the film, the emotion, focus and scale of each scene with its adaptations of the structural orientations. Films such as Fritz Lang’s metropolis uses vertical scale to create an adaptation of societal hierarchy by introducing a physical division in height as seen in figure 4 and figure 5. Placing the rich at higher floors than the poor, a concept and societal norm that can be seen in today’s cities (Sadowski, 2016). This theory supports the idea that architecture is an influential party in the development of cinema as the way in which utopian/dystopian futures are represented in films exaggerates what can be clearly seen in societies over the last century as metropolis’ have developed and grown, Contextualised in Lang’s film Metropolis (1927)

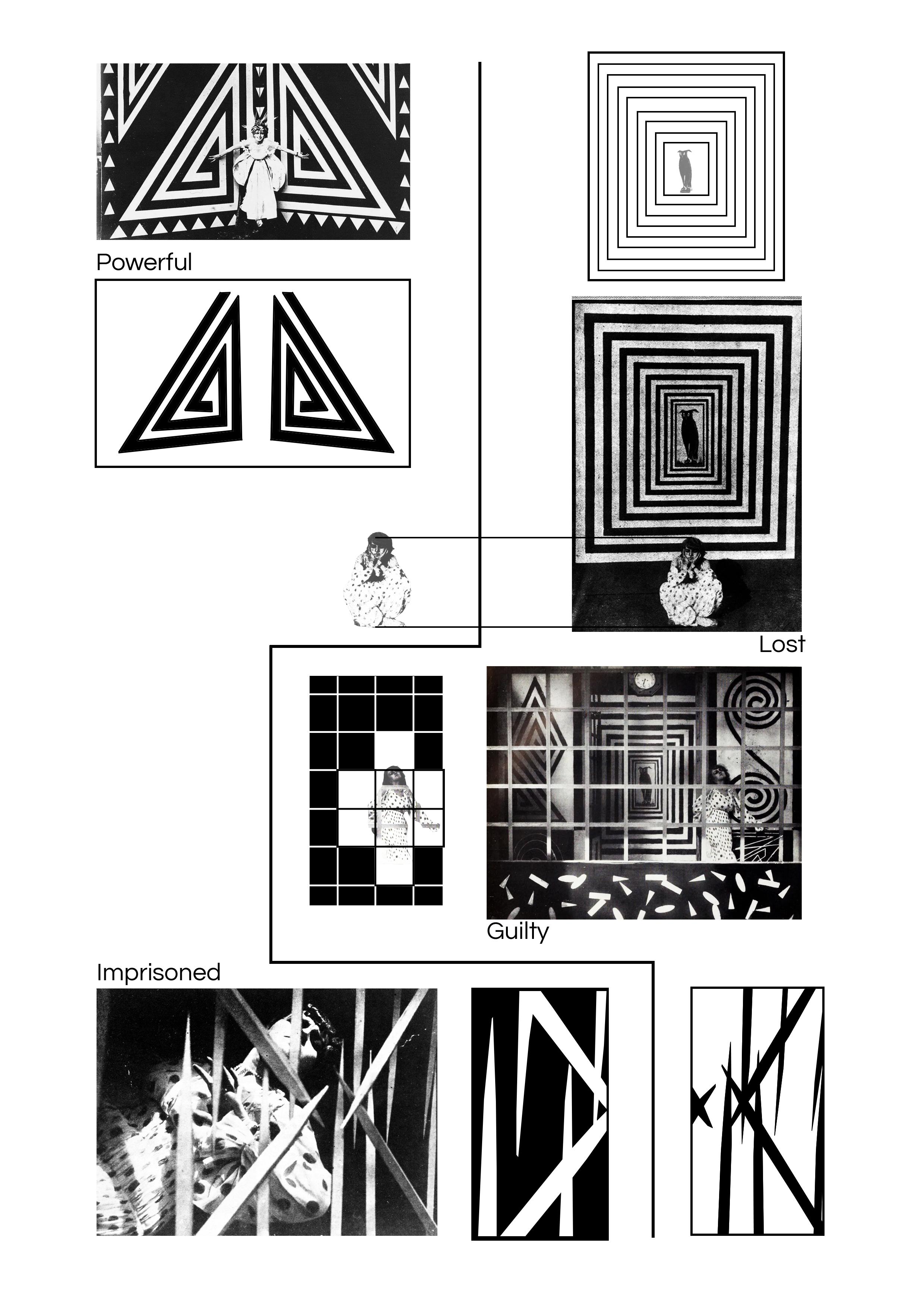

How Does the film set influence the sequence? Looking back into the idea of futurism allows for the question of sequence and influence to be answered. Anton Guilia Bragaglia’s film Thais, filmed in 1917, used a different approach to cinema in which architecture influences film through focus and sway of where the watcher places their attention. The use of doorways, corridors or windows draws the viewers’ attention to the smaller details creating a more intense sense of emotion. The sequencing techniques can be seen in Bragaglia’s film, the only existing futurist film, which throughout its cinematic progression begins to increase the focus of attention from the wider story to the main character through changes in set design and layout and the position of the character followed using camera positioning and zoom allows the viewer to become immersed in the film (Re, 2008).

Enrico Prampolini was tasked with the curation of each set; his desire was to use the movement of futurism to enable him to abstractly redefine the way cinema

Figure 4: Visual Extract from ‘Metropolis’, Fritz Lang Figure 5: Set image of Capital Building ‘Metropolis’, Fritz Lang

Figure 4: Visual Extract from ‘Metropolis’, Fritz Lang Figure 5: Set image of Capital Building ‘Metropolis’, Fritz Lang

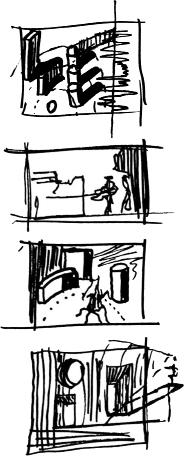

is perceived. (Berghaus, Pietropaolo and Sica, 2018) Through the progression of geometric architecture Prampolini begins to add elements of chaos aiming to highlight the descent of the Slavic Duchesses mental state. He uses this abstraction of shapes to create depth within each scene carrying more and more intensity along with them. figure 6 represents this use of geometry and depth as it maps the final stages of the film, articulated in a style influenced by Bernard Tschumis sequence mapping. As the film progresses the sharpness of these geometric shapes begin to appear more powerful and impactful on the scene. Referring to figure 6 and comparing the first scene, containing art deco inspired triangles, and the final scene, composed of sharp jagged steel framework, it can be seen that Prampolini was influencing the narrative and sequence with his composition of set design. One could reflect on this change in materiality to mean a change in mental state, the Duchess appears calming and ‘regular’ much like the triangular shapes. However, by the final scenes she could be considered to have evolved into something harsh, cold and erratic much like the collapsed steel framework. Following on from the previously

discussed idea, the steel bars used by Prampolini can be seen to be acting as a form of imprisonment for the duchess. As the set design can be considered a metaphorical tool these ‘prison bars’ may have been used to express a physical solidification of the Duchesses guilt and her underlying desire to be held accountable for what she has done. Slowly the sequential progression then sees the ‘prison bars’ beginning enclosing upon her trapping and killing her.

Finally, when looking at Giulio’s film, due to the lower access to technology, the sets themselves must be reduced in scale. This could have acted as a barrier disabling any opportunity for larger scenes and therefore reducing what could have been contained in each space. One side of this view is that the film suffered because of this however, another side of the argument see this as Prampolini’s saving grace. Due to the reduced size the intensity and quality of artworks forged one of the most influential movies in cinematic history showing true skill to control such a small space in such a way (Marcus, 1996).

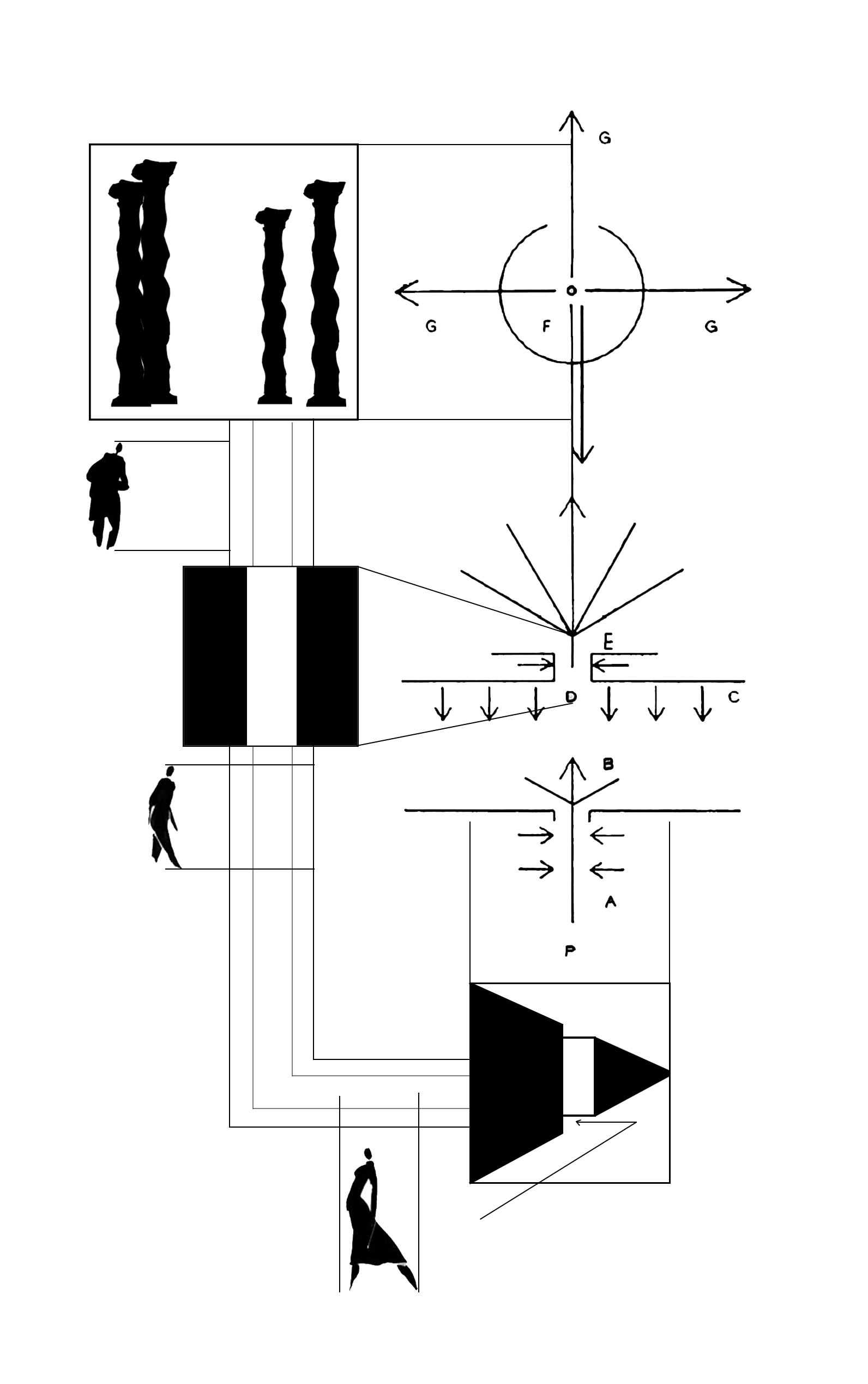

Figure 6: Sequential Mapping of ‘Thais’, Anton Giulia Bragaglia.Sequencing as discussed by Carla Molinari within her research article Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces is determined through montage and imagery which is described as “a key theme in modern architecture” (Molinari, 2021). Where then can this ‘Key’ factor of architecture be influential in relation to cinema and sequence. Molianri focuses on more traditional architecture when dissecting the art of montage by looking at noncinematic forms of architectural montage, initially engaging with Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Baldachin in the basilica of Saint Peter. While beautiful architecturally, the Baldachin forms a journey with its adaptation of eight images or stills. Molinari aimed to use this as evidence to support the idea that architecture can be manipulated by the sequence. This creates an opposing view, in a manner, to that of the futurists who aimed to use architecture as an influence on the sequence. Early within the article, research into other architectural opinions of montage began to be cut apart specifically that of luigi Moretti, who

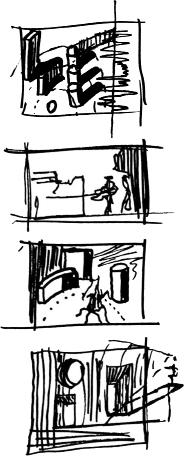

looks at the idea of architectural forms as aids to that of montage by saying: “Architecture is understood through the different aspects of its form, that is in the terms of which it is expressed…. structure of internal spaces, density and quality of materials, geometric relationships of surfaces” in his paper Structures and spaces (Moretti, Bucci and Mulazzani, 2002). Morettis listing of architectural expressions highlights the use of “internal spaces” and “Geometric relationships” both of which could be considered as aspects of cinematic architecture. As discussed previously in considerations with Bragaglia’s Thais the visible use of geometric surfaces and internal spaces are key visual and physical constructs that aided in his representation of a classic opera. Continuing in the breakdown of montage and sequence Molinari begins to consider representations of movement through the Basilica. Using Morettis diagram of sequence (figure 7) she could be wanting to define the movement through a sequential space the path around which architecture is erected,

Figure 7: Sequential mapping of the Basilica, Luigi Moretti with intergration of Bernard Tschumi

Figure 7: Sequential mapping of the Basilica, Luigi Moretti with intergration of Bernard Tschumi

backing the claims that structure bends to the will of the sequence. Morrettis use of the term “Form” combined with the use of “reality” shows that his mapping of the journey is a considered approach to the viewers interactions within a given space. The process from entry to exit is defined by contextualised by what forms are presented to the subject, a doorway or a turning for example. Something similarly discussed by Bernard Tschumi in his article ‘Sequences’ in which he discusses that the “The route is more important than any one place along it” he is clearly stating that the journeys “route” is the influential factor of the sequence (Tschumi, 1981). Could this idea then be considered as Tschumi declaring the movement of the character through a scene to be the crucial factor within the journey? If so, then it may be said that the architecture that influences the direction of movement is in fact more significant than that of the route through, almost consolidating the theory that the architecture commands the sequence.

Later within the ’Sequences’ text Tschumi

continues his breakdown of the narrative by discussing the implementation of “Frames” into the sequence. He expresses that “the content of congenial frames can be mixed, superimposed, dissolved or cut up giving endless possibilities to the narrative sequence” by saying this he is making comment on the ability of physical or imaginary parameters that can be used to change the direction of the narrative (Tschumi, 1981). One could consider the conceptual idea of “frames” to be that of the physical architecture, the implementation of architecture becomes the solid that controls the sequence. Exploring further Tschumi’s theory of mapping it can be said that it is possible to sequence through the use of physical architecture, figure 8 shows an example of his mapping technique. If this is a strategy of mapping the sequences in reality, could it then be used in an effective way to map the sequential processes of film?

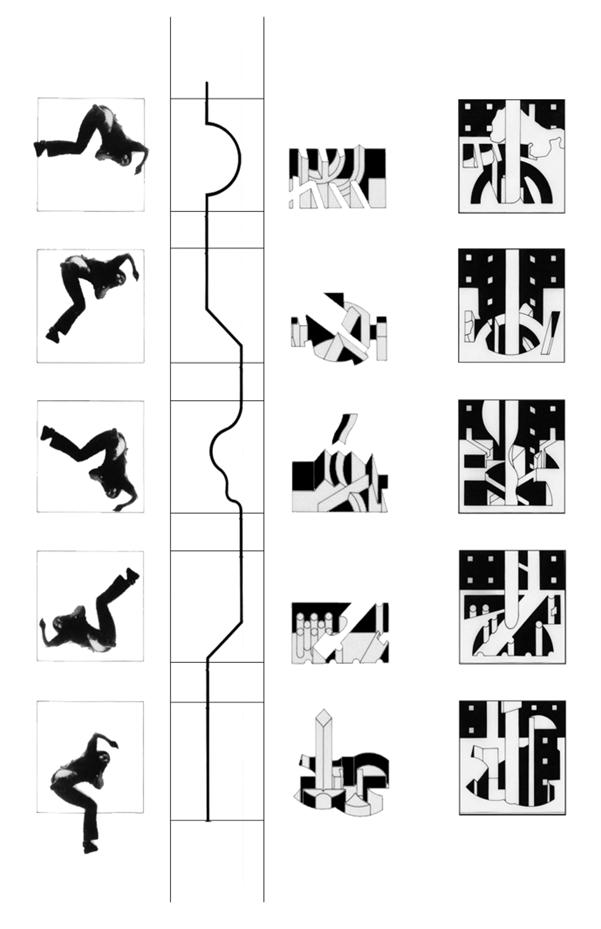

Furthering the idea of Tschumis sequential mapping and its possible implementation into film, one must investigate other futurist inspired filmography and dissect

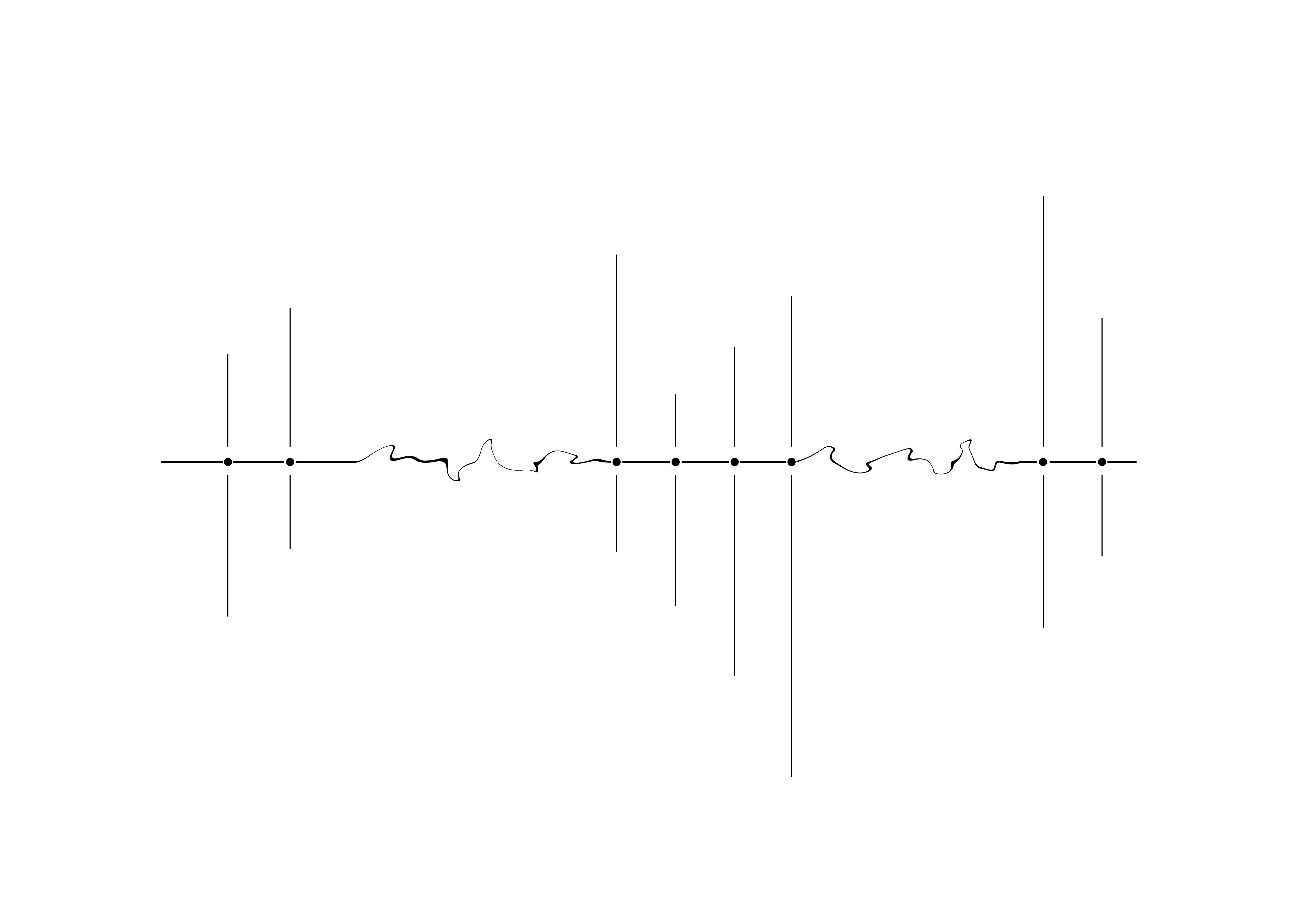

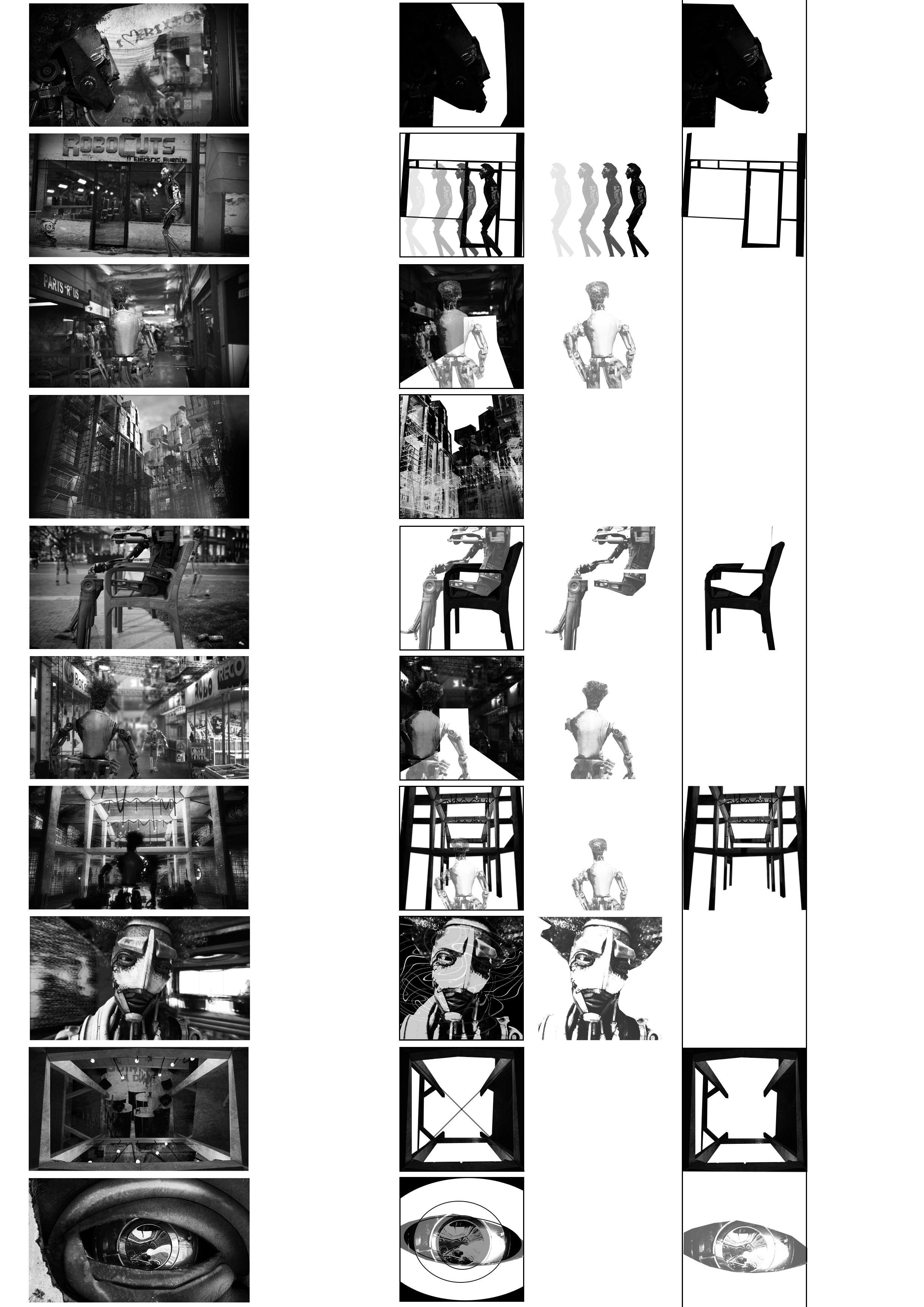

Figure 8: ‘The Fall’ Bernard Tschumihow the architecture has dictated the directional movement of the sequence. Directed by Kibwe Tavares in 2011, the Afrofuturist film ‘Robots of Brixton’ became a highly discussed representation of the future, that aims to forge a dystopian representation of the poverty and disassociated social hierarchy of London life (Bould, 2019). Throughout the sequence it begins to pan to and from historic outbreaks of racism and discriminatory rioting within the community of Brixton. Kibwe uses interpretations of futurist brutalist architecture that looks to be parasitic in its technological nature, possibly imitating the implied governmental view towards the black community of Brixton. Figure 9 Shows a narrative breakdown of the cinema previously discussed in which Kibwe begins his narrative sequence through an aspect view of the main protagonist, who navigates through the architectural narrative. To fully study how Kibwe has generated this sequence one must tear the character from the journey to fully understand sequential make up of each scene, to view the architectural factors of the set. Robots of Brixton as a narrative follows that of a lead protagonist embodied through a “skinny and dully looking” humanoid robot who walks the streets of the new Brixton. Kibwe uses the architecture of the set to influence where the character moves, the diversity of camera angles, zooms and frames allowing the watcher to experience this journey for

themselves. To open the narrative Kibwe generates a close zoomed focus of the lead robotic protagonist peering from an enclosed bus in transit, passing in the background shows glimpses of the dystopian decayed Brixton and its “retrofit architecture” (Bould, 2019). Continuing the journey the figure enters an enclosed market corridor, structures running either side shrinking the possibility of directional change, forcing them to move forward through the narrative. Furthering on and moving past this junction to an open park in which the camera focuses on the solid void of a bench on which a robot sits, thus forcing the scene to freeze behind this blockade, creating a juxtaposition between the background (open park) and the foreground (solid void). Once through the park they enter a large skeletal concrete framed structure, a large empty space controlled by the architecture. As a set it allows possibilities for the protagonist to travel around the space as a framework, the position they move to will be supported or manipulated by the architecture. As the concluding frame to this sequence of narrative Kibwe forces the frame into the robotic eye of the protagonist enclosing all room for sequential change and forcing the journey to an end. In reflection of this sequence, the design of the architecture is the clear boundary throughout, the solid dictates the spatial void.

Figure 9: ‘Robots of Brixton’ Sequence Mapping

Figure 9: ‘Robots of Brixton’ Sequence Mapping

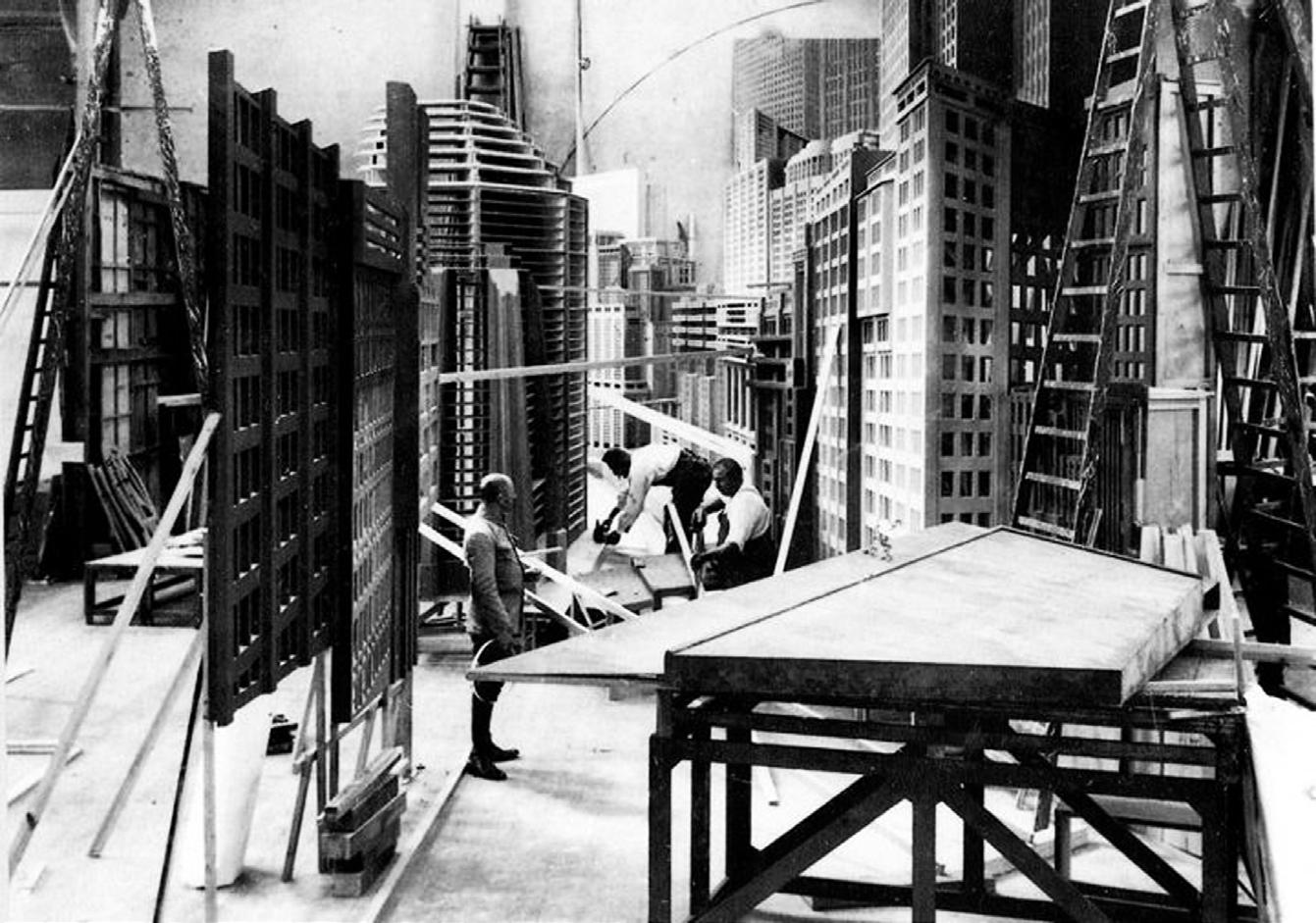

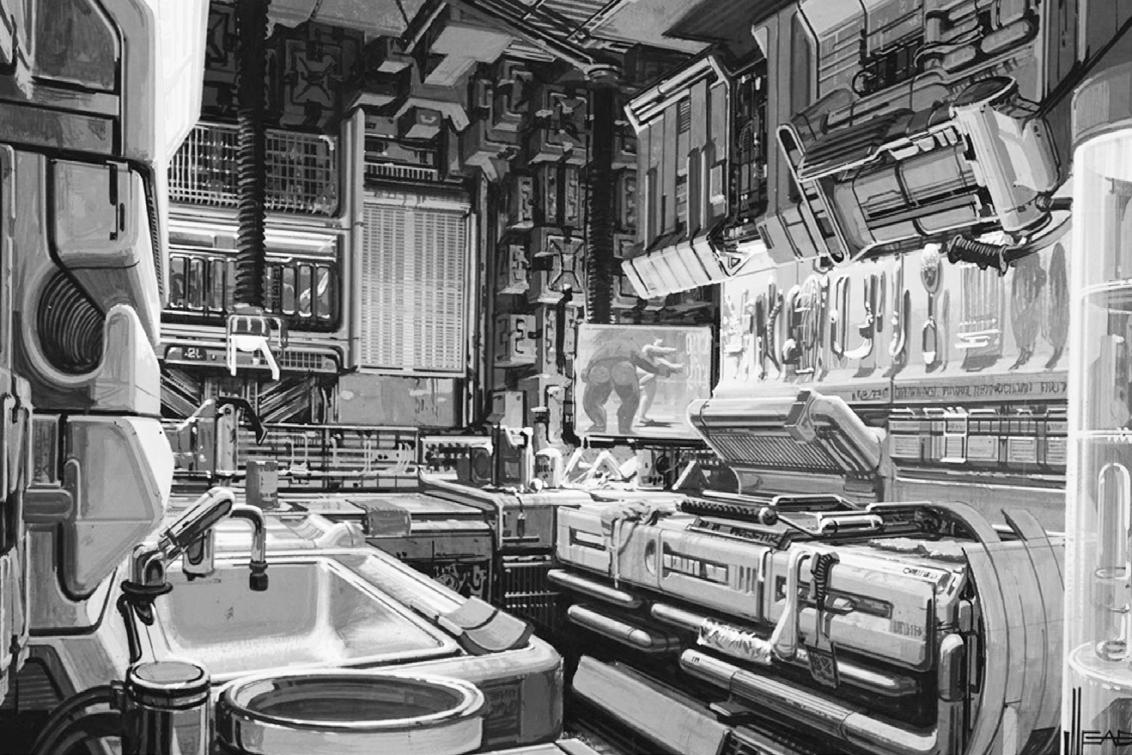

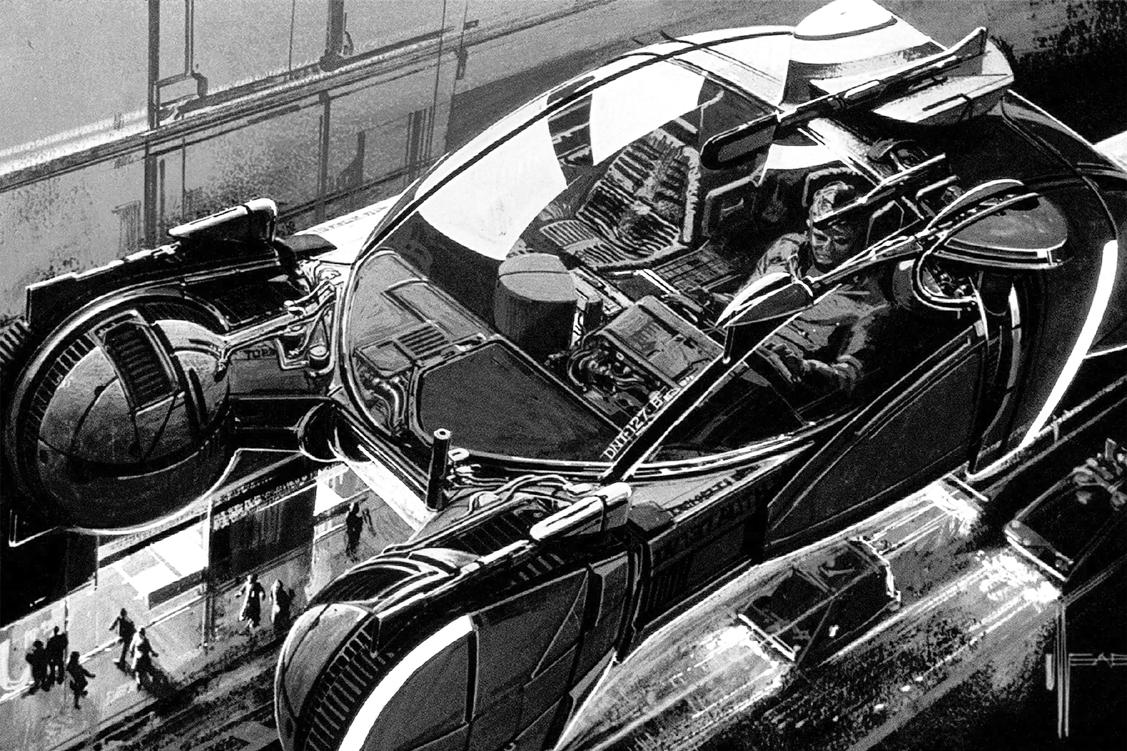

Moving away from modern Afrofuturist cinema to early-stage Futurist cinema focusing on structural set design rather than CGI constructed sets and developing an understanding of the construction process along with the varied mediums used in lower technological filming. Firstly by, considering in increased detail ‘Metropolis’ by Fritz lang from its initial sketching of possible architectural designs to the construction of sets and finally the dissection of its sequence and its architectural influence. Due to the technological restrictions in 1927 the ‘Metropolis’ film had to be designed through rough sketches and careful manipulation of scales. Artist Erich Kettelhut was the lead inspiration for the set artistic style and architectural design of Metropolis; he did so through his rendered sketch drawings of what could be a metropolis of tomorrow. His adaptations of vertical architecture link back to the previously discussed ‘Voisin’ by architect Le Corbusier. Initially Kettelhut entered the designing of metropolis with a vision of expressionist architecture forming skyscrapers around a large

central church, to which lang expressed his desire to “scrap the church” and replace it with a larger central skyscraper (Deutelbaum, 1997). Does the final cityscape reflect the desired nature of the futurists? In some ways it could be too dystopian, one could revolt at the thought of vertical cities being classed as a utopia and what Lang and Kettelhut produced far from what a futurist would have wanted. However, if one looks at the futurist Manifesto one can only begin to believe that to them dystopia is utopia, as point seven of the manifestos exclaims “There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character” also saying there is no beauty without hardship or pain a distinguishing characteristic of a dystopian society (Marinetti, 1909). This then could pose question around the intentions and reasoning for the creation of this ‘Metropolis’ anti-utopia; what aspects of late 1920’s initiated Langs desire to produce such a rugged extraction of existing social ideals? Some could consider that lang wanted to create an apt metaphoric representation of the social class divide within the existing

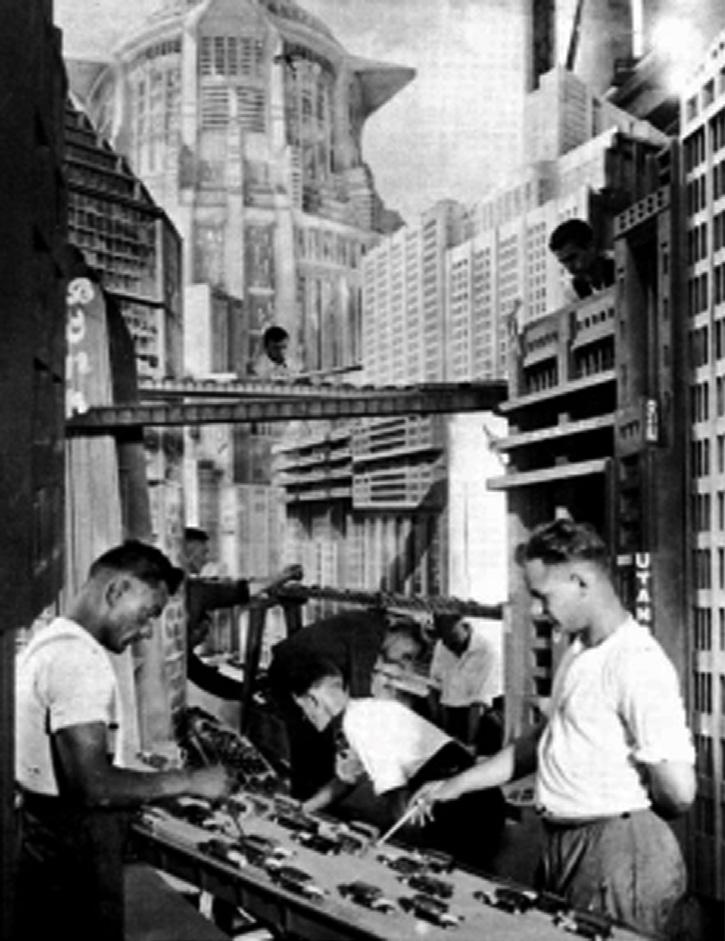

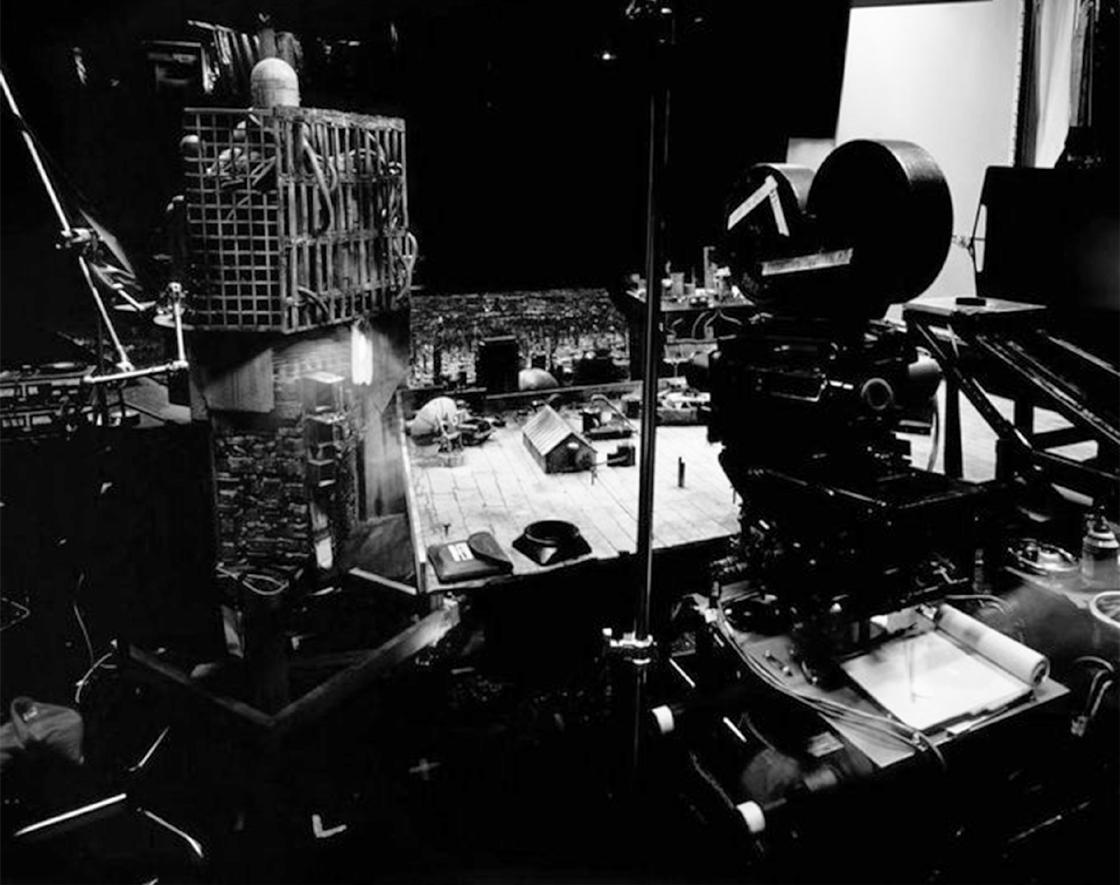

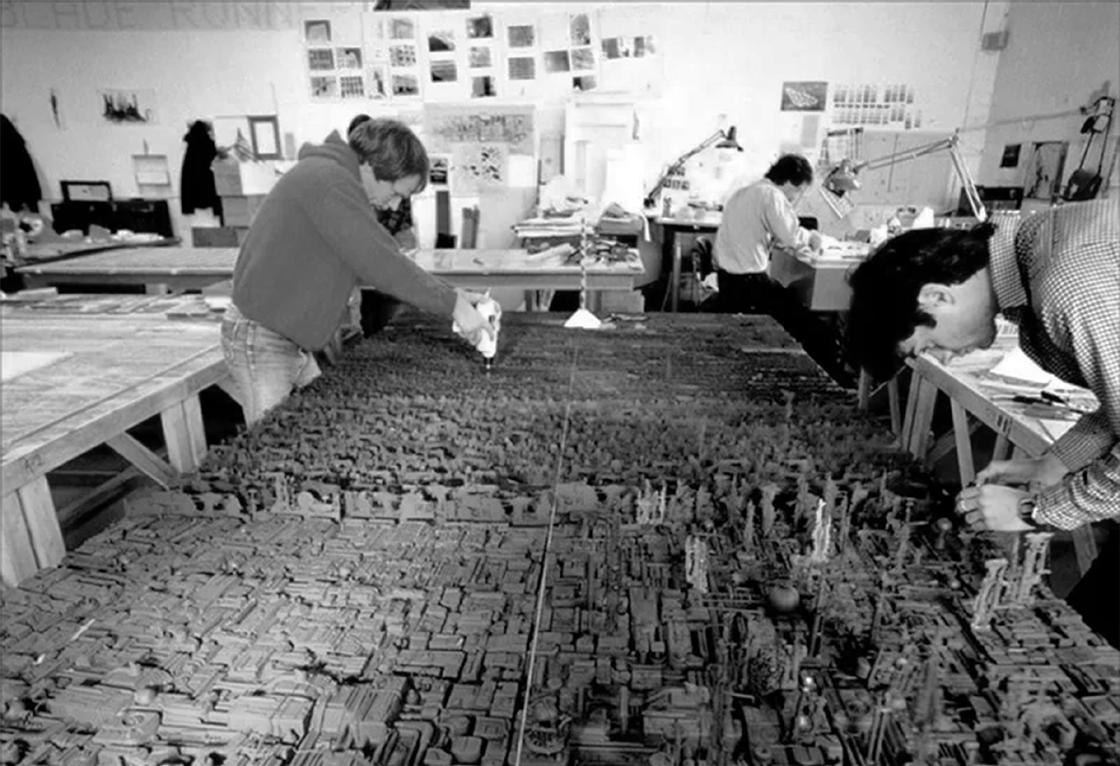

Figure 10: Set Construction, ‘Metropolis’

Figure 11: Scale Model detailing and construction, ‘Metropolis’

Figure 10: Set Construction, ‘Metropolis’

Figure 11: Scale Model detailing and construction, ‘Metropolis’

society, maybe even using this as a warning of what may come if the issues are not rectified. Within an article written on this question Deidre Bryne voiced their opinion that metropolis’ subdivisions of structure and community is “Metonymic of the class divisions in the urban society” clearly expressing this with strong belief, they continue to discuss their opinions using architectural examination more specifically the style of architecture. When comparing that of the ‘Metropolis’ film to that of early construction Manhattan they begin to dissect the idea of the Chrysler building expressing that it has many paralleled features to the capital building in ‘Metropolis’ stating “It testifies vividly to the dominance of capital over labour and articulates the power of moneyed classes to shape landscape and social spaces” (Bryne, 2003). This could mean then that the film is actively attacking the architectural development of Manhattan and the inevitable social divide that this was creating?

Metropolis, like Thais, was developed during a preliminary period in the 20th

century causing the technological possibilities to be limited when filming and curating sets, this is clearly visible when seeing the design and construction of said sets. Their use of smaller scaled models to create scenes of larger objects (figure 10) to create these visuals for the city of tomorrow. It is also interesting to highlight the way in which they used these sets to record the scene, each camera man becomes immersed within the action along with the characters reflecting the skill required for a low technological film. Due to the impossibility of using CGI and other methods of digital adaptations the use of small-scale model work has been used, specifically for the icon shots of the vertical city, the capital building and the diverging roads and planes as seen in figure 11. This highlights the detail required to develop such a scene and sequence as each still of the city vista shots had each car moved one millimetre per frame, creating forty metres of film behind (Minden and Bachmann, 2002). This then impacted the ability of sequential manipulation allowing Lang to adapt and manipulate the city itself.

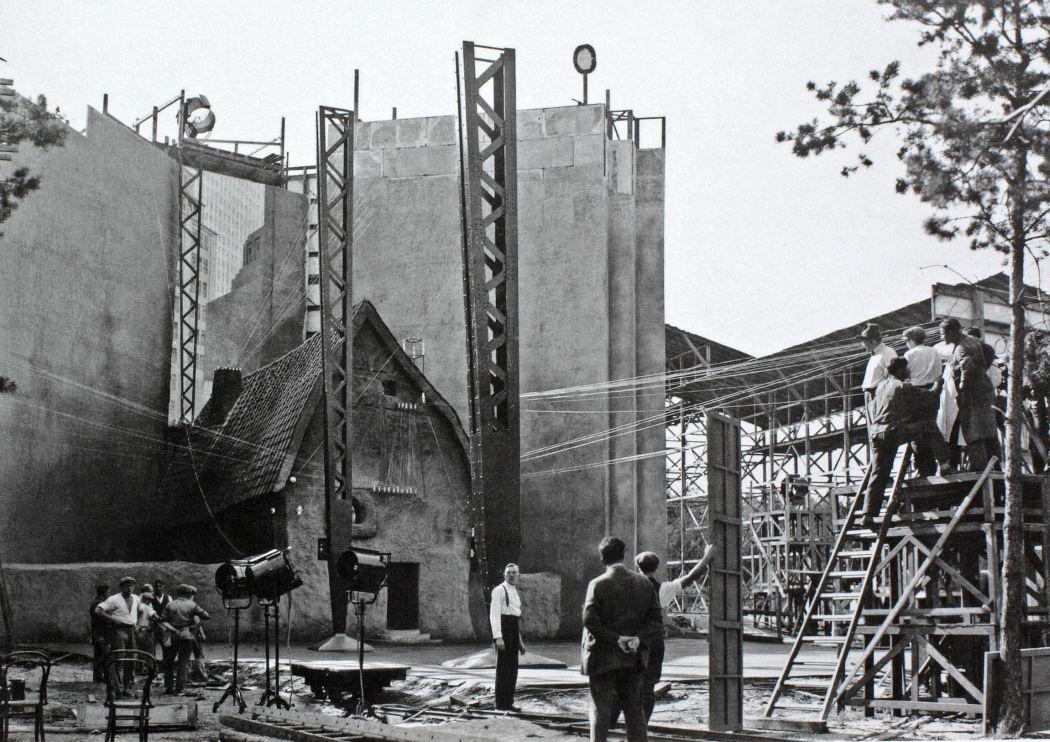

Figure 12: Sequence Mapping of ‘Metropolis’

Figure 12: Sequence Mapping of ‘Metropolis’

Alongside the smaller model scale sets Lang used larger physical scale sets, the use of fabrics scaffolding, and timber allowed for the temporary structures to become inhabitable spaces from large halls and gardens to small, enclosed rooms, each one dictating how the sequence of the cinema would develop. Like the previously discussed film (Thais and Robots of Brixton) the use of Bernard Tschumis sequence mapping will dissect the use of architecture within ‘Metropolis’.

Focusing on the explored sequence of ‘Metropolis’ (figure 12) it can be clearly realised that lang has used the architecture to induce a highly detailed framework. His use of combined open and enclosed spaces along with narrow and wide create a sequence that captures the witness. Towards the beginning of the film Lang introduces the lower level (home of the workers) in an enclosed narrow tunnel with only artificial lighting. Through using a combination of a large huddle of inhabitants along with the tunnel Lang makes the architecture the controlling factor forcing the inhabitants

to follow the tunnel. This also creates the parallel between reality and prediction regarding the social hierarchy. Following the tunnel leads to a small lift shaft in which the characters are lowered into the “City of Workers” a city below ground constructed entirely of stone or concrete with minimal aesthetic to it. Moments later the scene is dropped, and a new sequence emerges now in the higher level of society in clean open garden, with plants that create structures to be inhabited. Creating archways standing on leg like structures (Russell, 2009).

Juxtaposing the garden Lang continues to delve into the smog of the underworld presenting the lead protagonist with a journey of self-reflection when standing at the foot of a large industrial machine. Due to the size of such a structure the scene no longer depicts the human as the focus of the sequence, in fact it demands its own stage, the set becomes the protagonist. The Sequence is cut to an end as the character flees back to the surface allowing for a new frame to begin in which Lang showcases the streets of the city, the vein like roads crossing in

between structures he positions a view direct to the capital building which stands in the background this view focused and manipulated by the skyscrapers aligning prospectively in the foreground. Lang’s use of these control factors (foreground) brings structure to a large frame which could have been reflected as weak and liquidated in the eyes of the viewer, again the use of architecture and structure allows for the scene to be focused.

Produced in 1982 and directed by Ridley Scott this futurist dystopian adaptation of Los Angeles during the year 2019. As a production and futurist inspired cinema ‘Blade Runner’ attempts to divulge into the socio-economic issues of the current society in which it was conceived. Many academics have tried to create a clearer picture of the messages in which Scott was trying to relay, Douglas Williams stated his view was that ‘Blade Runner’ emerged to

“teach or worry us about the unprecedented and life-threatening complexities of our technologies, the social and political definition of their deployment and development, and the incoherence of our currently stereotypical attempts to escape from the repercussions of the world we see taking shape before our eyes” (Williams, 1988).

In saying this Williams may be attempting to announce that in his eyes the world he is situated in is controlled by a government who see no issue or fault in their actions and who believe they are doing good. As well as this Williams’ use of the phrase

“our current stereotypical attempts to escape” solidifies his position and ideals that the government are a party he believes the people underestimate in how far their roots go into societal control, that they have become an almost an unstoppable force. Whereas they are only being fuelled by corruption and greed. It could also be interpreted that the ones who are attempting to “escape” from their reality are in fact those who build the society, those who work the machines, like in Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’, those who live on the lower levels are the ones who will have to “escape”.

Ridley Scott’s use of futurist vertical architecture consolidates the idea of a dystopian future society riddled with over population, crime, poverty and economic decline. How then did Scott use the technological possibilities at the time (1982) to allow for larger scale sequences throughout his film? In a not so dissimilar way to how Lang, Scott began his development of the futurist style through early-stage imagery and sketches, the difference being the medium and way in

which they were done. Shown in figure 13 is the proposed images by Syd Mead, an artist based out of Michigan USA, his designs had a modern futurist element to them due to the use of curves, dynamic lines and colour (Syd Mead, 2022). Mead’s detail and dedication to the style allowed for Scott to directly develop from sketch to physical model or set, examples can be seen in Deckard’s Kitchen and The Spinner vehicle as seen in the comparative figure 14. Not only then, did Scott use the advantageous technologies but also the modern artistic abilities of his peers to generate mocklife renders of his vision allowing for a more enriched Sci-Fi film. Even though Scott had access to greater technologies to that of Lang, he also adapted the uses of scaled models to create the larger cityscape scenes along with the flying automobiles. In a very similar way to Lang Scott created the city reimagining through large models (Figure 14) in doing this it is clear to see that while the technological advancements in colour film, minor digital animation and artistic rendering are prevalent it has not been further developed to the point of constructing large city scaled sets using

CGI, much like in ‘Robots of Brixton’.

Continuing to the consideration of architectural input on the sequential narrative, figure 15 is a Tschumi influenced breakdown of frames throughout the ‘Blade Runner’ film. Is the architecture an influential part of the sequence produced? While it can be considered that the set design is controlled largely by camera angles and focus due to the abstract and odd close ups used by Scott to highlight facial expressions of each character to convey the emotion within the dark and hazy scene (Kellner et al, 1984, pg. 4). As a counter to this argument however, the sequential mapping does highlight multiple frames in which the architecture has directly controlled the scene. Scott’s use of smaller box like rooms force the frames to be enclosed making the viewer feel as though they are trapped within not just the room but the city. Scott also develops an idea of enclosure within the streets of dystopian Los Angeles through the exaggeratedly tall structures and the narrowing of footways, this also adds to the idea of overpopulation as more structures are required to house more civilians. Architecturally Scott has

Figure 15: ‘Blade Runner’ Set Model Construction

Figure 15: ‘Blade Runner’ Set Model Construction

a combination of frames throughout the two-hour film, in which he uses large scale sets, office and living spaces as well as smaller spaces inside vehicles creating obstruction in the foreground.

The opening scenes of the film are mostly frames moving through the large city controlled by the skyscrapers around while it follows a flying vehicle small in comparison to the buildings. Again, the architecture becomes the solid and the vehicle the character navigating through. Views then shift to the cockpit of the vehicle showing distant images of the exaggerated city around but enclosed and blocked by the control panels of the dashboard. Not only could this create the element of imprisonment but the idea of the impossibility of movement a perception of weakness in comparison to that which stands in the background. Continuing the sequence begins to enter the capitol building, the interior seems to parallel the exaggeration of height as seen in the cityscape, long halls and columns create directional manipulation of the spaces pushing Deckard, the lead protagonist, further into the building and further into the chronological journey, this is further suggesting that the architecture is directing the sequence. Structurally the style of architecture from external to internal changes, the external being futurist, clean lines and Manhattan esc

while the interior becomes almost Egyptian through the use of towering ceilings with large columns, the style similar to that of the Mayan pyramids (Yuen, 2000, pg. 8).

Deckard later enters a chase with an antagonist through the tightly packed streets here Scott has used the overpopulating civilians as the main source of control for the protagonist’s path. A decision that differs to that previously seen; this could be suggestive of Scott’s desires to once again express his view of the societal issue seen within major cities such as Hong Kong and Tokyo, both are high on the list of population density causing a huge economic and environmental crisis due to the increase in carbon emissions and rising temperatures (Dukes, 1971). Scott’s use then of the civilian people as the control factor within this frame of sequencing contradicts that of the argument posed in this dissertation, while the city does provide a structural encouragement in the background the foreground manipulation comes from the people. The evidence reviewed suggests that one cannot firmly say all cinema is completely manipulated by the architecture. However, one can suggest that throughout the futurist influenced film the architecture does hold a great deal of power over most of the sequences.

This Dissertation aimed to explore how futurist architecture has influenced the sequencing and journey of cinema through its manipulation and control of film sets by introducing factors to direct the movement of characters within each frame. The deconstruction of futurist inspired film throughout time has realised a clear indication that the architecture influences the sequence more so than the sequence influencing the architecture as previously discussed by Carla Molinari. A plethora of Evidence based research supports these claims found from the dissection of framing from various films through a sequential mapping in the style of Bernard Tschumi. Thus, creating the possibility for a comparative analysis of technological inputs and their impact on the dynamic and scaled possibility of the narratives. A further discussion also occurred into the ideological issues each director wished to metaphorically tackle through the futurist re-imagining of each of their current societal position in time.

Throughout this dissertation the ideas of futurist architecture have been analysed

confronting the impact they have made onto cinema over the past century. Not only by the input of architectural style but architectural ideals and metaphoric manipulation. Research into the concept of vertical architecture and previous examples of worked plans allowed for the realisation of futurist opinion on utopia and dystopia, one would assume the desires of futurists would aim to create a utopian civilisation which aims to merge all levels of society and create harmony. However, based on findings within this dissertation it could be considered that futurists aimed to design anti-utopias in which they began to dismantle and highlight the reality of where their current societies could be heading. As if the true purpose of the movement was to force a civilization wide realisation of the deep rooted societal issues supported by the government. The contributing factors leading to this conclusion came from the inspection of futurist inspired film and the referral of relevant literature from established resources by other academics.

Continuing from the deconstruction of

the futurist movement investigation into the makeup and construction of film sets from Thais (1917) to Blade runner (1982) began to define and understand how the use of structure in cinema controlled the way in which sequencing was presented. Considerations for technological development as a factor for intensity of abstraction throughout the films plus the possibility to create larger more interactive scenes with the use of CGI, like in ‘Robots of Brixton’, were made when discussing how each film differs and whether these differences have improved or restricted cinema. As a concluding note to this point the original futurist film, while influential in its content, is extremely limited to smaller sets causing the scenes to become more enclosed. However, one could then say that due to this factor it allowed for Prampolini to increase the power of his abstracted geometric shapes to form a greater level of futurist influence over the sequences. The journey it proposes is so involved with the architecture the viewer becomes lost in the spiralling decent of structure. That is not to say the films that followed lacked in their abstraction or connections to futurism, on the contrary, they allowed for the witness to become just as immersed if not more so within the spaces no matter how restricted or controlled they became by the architecture.

A Further way in which the sequencing was explored was through a comparative combination mapping of all films discussed within this dissertation (figure 16). By creating figure 16 it allowed

for a direct comparison of both the scale of architectural input but also the similarities through which each director has used structure. Taking a closer look, it can be seen that ‘Robots of Brixton’, ‘Thais’ and ‘Metropolis’ all used a similar sharp solid void within their sequencing to show entrapment or control. This also allowed for a further evidenced physical view of the similarities between each of them highlighting the side in which this dissertation has leant after critical analyses of the cinema. That side would be towards the idea that architecture does influence the sequencing in film. However, it cannot conclude on the fact that it influences all aspects and parts of the sequences as evidenced in Scott’s Blade Runner due to the frame controlled by the overpopulated streets of civilians. One could then also begin to form a passive argument when comparing the arguments of Carla Molinari in her paper Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces of architecture being the aspect influenced by the sequence, she discussed this when breaking down the Baldachin standing within the Basilica and the journey of faces it creates. While it can be seen as evident that architecture may be influenced or may have been influenced by the architect’s vision of sequence it does not seem to parallel that of filmic architecture. Cinematic architecture due to the evidence researched can be concluded to be manipulating the sequence of which it sits.

Berghaus, G., Pietropaolo, D. and Sica, B. (2018). 2018. [online] Google Books. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/2018/YK9VDwAAQBAJ?kptab=editions&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi8sPCW1Pb7AhXTnFwKHXpyALoQmBZ6BAgJEAc [Accessed 9 Dec. 2022].

Bould, M. (2019). Afrofuturism and the archive: Robots of Brixton and Crumbs. Science Fiction Film and Television, [online] 12(2), pp.171–193. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/105/article/729411/pdf [Accessed 12 Dec. 2022].

Byrne, D. (2003). The Top the Bottom and the Middle: Spaces, Class and Gender in Metropolis. [online] Gale Literature Resource Center. Available at: https://go-gale-com.leedsbeckett.idm.oclc.org/ps/ retrieve.do?tabID=T001&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&hitCount=1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=1&docId=GALE%7CA117772762&docType=Critical+essay&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=ZLRC-MOD1&prodId=LitRC&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CA117772762&searchId=R1&userGroupName=lmu_web&inPS=true [Accessed 14 Dec. 2022].

Deutelbaum, M. and Neumann, D. (1997). Review of Film Architecture: Set Designs from Metropolis to Blade Runner. Film Criticism, [online] 21(3), pp.115–119. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/ pdf/44018889.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A54c2a4b2a88616d71aecd3d1b2b0d723&ab_segments=&origin=&acceptTC=1 [Accessed 13 Dec. 2022].

James Stevens Curl (2018). Making Dystopia. Oxford University Press.

Jukes, T.H. (1971). Overpopulation. Science, 173(3996), pp.475–475. doi:10.1126/science.173.3996.475.b. Kellner, D., Leibowit, F. and An, M. (1984). "Blade Runner J MP C A REVIEW OF CONTEMPORAR MEDIA Blade R nner A diagnostic critique. Jump Cut, (29), pp.6–8.

Luzzi, J. and Carey, S. (2020). Italian Cinema from the Silent Screen to the Digital Image. [online] Google Books. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=sKTODwAAQBAJ&lpg=PT275&ots=zHsLO2ldGb&dq=Thais%20Anton%20Giulia%20&lr&pg=PT275#v=onepage&q&f=false [Accessed 5 Dec. 2022].

Ma, N. (2017). Emergence of a utopian vision of modernist and futuristic houses and cities in early 20th century. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 61, p.012033. doi:10.1088/17551315/61/1/012033.

Marcus, M. (1996). Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s ‘Thais’; or, The Death of the Diva + The Rise of the Scenoplastica = The Birth of Futurist Cinema. South Central Review, 13(2/3), p.63. doi:10.2307/3190372.

Mauro, V. and Di Taranto, C. (1990). UTOPIA. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 23(2), pp.245–252. doi:10.1016/ s1474-6670(17)52678-6.

Minden, M. and Bachmann, H. (2002). Fritz Lang’s Metropolis: Cinematic Visions of Technology and Fear. [online] Google Books. Camden House. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=oyOO_HNw0KQC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=metropolis+set+construction+fritz+lang&ots=i_XJihwns3&sig=u7r6K4KqaRv_HDxUK-EMpmttSXY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Set%20&f=false [Accessed 16 Dec. 2022].

Molinari, C. (2021). Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces. The Journal of Architecture, 26(6), pp.893–911. doi:10.1080/13602365.2021.1958897.

Moretti, L., Bucci, F. and Mulazzani, M. (2002). Luigi Moretti: Works and Writings. [online] Google Books. Princeton Architectural Press. Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Luigi_Moretti/mCv5duNe2-kC?kptab=editions&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj-iee34_b7AhV4TkEAHQaeBScQmBZ6BAgHEAo [Accessed 11 Dec. 2022].

Moylan, T. and Baccolini, R. (2013). Dark Horizons: Science Fiction and the Dystopian Imagination. [online] Google Books. Routledge. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=YoREAgAAQBAJ&lpg=PA233&ots=0Qs4cm6RTH&dq=What%20is%20dystopia%20&lr&pg=PR4#v=onepage&q=What%20 is%20dystopia&f=false [Accessed 7 Dec. 2022].

Notaro, A. (2000). Futurist Cinematic Visions and Architectural Dreams in the American Modern(ist) Metropolis. Irish Journal of American Studies, [online] 9, pp.161–183. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/ pdf/30002693.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A4efba75ebc57436f9f976d6678c8df9c&ab_segments=&origin=&acceptTC=1 [Accessed 13 Dec. 2022].

Official Syd Mead Website 2021. (2020). Biography 1933-2019. [online] Available at: https://sydmead.com/ biography/.

Re, Lucia. (2008). Futurism, Film and the Return of the Repressed: Learning from Thaïs. MLN, 123(1), pp.125–150. doi:10.1353/mln.2008.0054.

Russell, E. (2009). Trans/forming Utopia: Looking Forward to the End. [online] Google Books. Peter Lang. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=f9z0DYQV6G8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA175&dq=Metropolis+fritz+lang+garden+&ots=mvJg-ravdc&sig=G4ZInIVWwVopgijeiR6ii4LxlBI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=garden&f=false [Accessed 18 Dec. 2022].

Sadowski, P. and Lang, F. (2000). Film and high-rise architecture: the vertical metaphor in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) THE FUTURISTIC TOWER OF BABEL. [online] Mansell Publishing, pp.1890–1940. Available at: http://www.tara.tcd.ie/bitstream/handle/2262/79222/Sadowski%20Metropolis%20poster.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 8 Dec. 2022].

Umbro Apollonio (2001). Futurist manifestos. Boston, Ma: Mfa Publications. Williams, D.E. (1988). Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade Runner. International Political Science Review, [online] 9(4), pp.381–394. doi:10.1177/019251218800900406.

Yuen, W.K. (2000). On the Edge of Spaces: ‘Blade Runner’, ‘Ghost in the Shell’, and Hong Kong’s Cityscape. Science Fiction Studies, [online] 27(1), p.8. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4240846. pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A069675c0742758c9c7886ded5af139eb&ab_segments=&origin=&acceptTC=1 [Accessed 15 Dec. 2022].

Company, T.L. (1982). Model Sets. vanity Fair. Available at: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/photos/2017/09/inside-the-making-of-ridley-scott-blade-runner [Accessed 16 Dec. 2022].

Corbusier, L. (1925a). Model of the Plan Voisin. 99% Invisible. Available at: https://99percentinvisible.org/ article/ville-radieuse-le-corbusiers-functionalist-plan-utopian-radiant-city/ [Accessed 14 Dec. 2022].

Corbusier, L. (1925b). Render of the Plan Voisin. 99% Invisible. Available at: https://99percentinvisible.org/ article/ville-radieuse-le-corbusiers-functionalist-plan-utopian-radiant-city/ [Accessed 14 Dec. 2022].

Harbou, H.V. (1927). Set Photograph from ‘Metropolis’. Art Blart. Available at: https://artblart.com/tag/erichkettelhut-and-fritz-lang-set-design-for-the-nibelungen/ [Accessed 14 Dec. 2022].

Lang, F. (1927a). Metropolis: Backstage. Monovisions. Available at: https://monovisions.com/metropolis1927-behind-the-scenes-silent-film/ [Accessed 14 Dec. 2022].

Lang, F. (1927b). Views of Metropolis. Tboake. Available at: https://www.tboake.com/dystopia/patterson/social_dystopia_1.html [Accessed 13 Dec. 2022].

Mead, S. (1982). Blade Runner Concept Artworks. Vanity Fair. Available at: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/photos/2017/09/inside-the-making-of-ridley-scott-blade-runner [Accessed 16 Dec. 2022].

Sant’Elia, A. (1914). Housing with external lifts and connection systems to different street levels. Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-futurist-architect-that-inspired-blade-runner-and-metropolis [Accessed 5 Dec. 2022].

Tschumi, B. (1981). The Fall. The Manhattan Transcripts.