9 minute read

Sequential Dissection of

Blade Runner & Metropolis Chapter Three ‘Metropolis’ 09

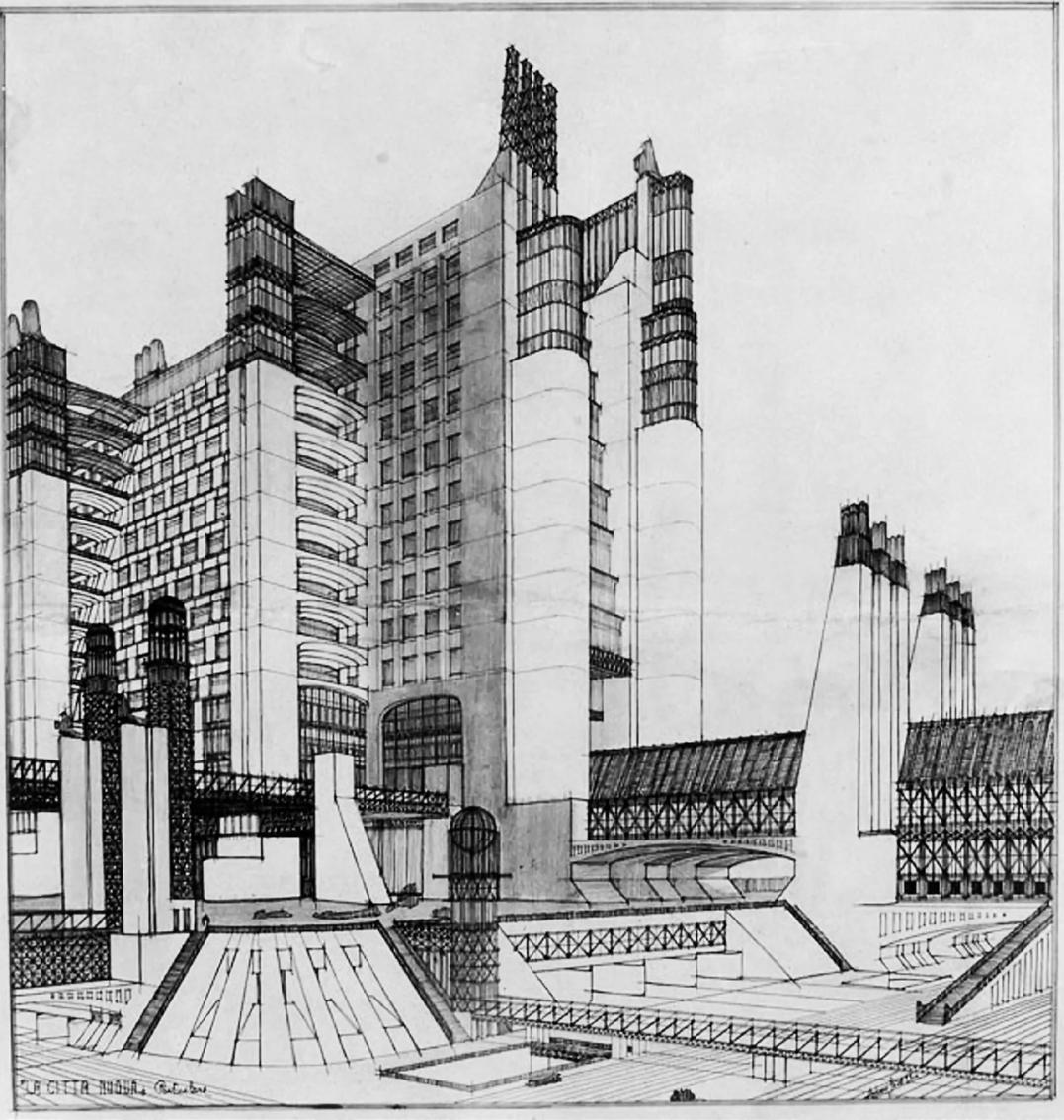

Moving away from modern Afrofuturist cinema to early-stage Futurist cinema focusing on structural set design rather than CGI constructed sets and developing an understanding of the construction process along with the varied mediums used in lower technological filming. Firstly by, considering in increased detail ‘Metropolis’ by Fritz lang from its initial sketching of possible architectural designs to the construction of sets and finally the dissection of its sequence and its architectural influence. Due to the technological restrictions in 1927 the ‘Metropolis’ film had to be designed through rough sketches and careful manipulation of scales. Artist Erich Kettelhut was the lead inspiration for the set artistic style and architectural design of Metropolis; he did so through his rendered sketch drawings of what could be a metropolis of tomorrow. His adaptations of vertical architecture link back to the previously discussed ‘Voisin’ by architect Le Corbusier. Initially Kettelhut entered the designing of metropolis with a vision of expressionist architecture forming skyscrapers around a large central church, to which lang expressed his desire to “scrap the church” and replace it with a larger central skyscraper (Deutelbaum, 1997). Does the final cityscape reflect the desired nature of the futurists? In some ways it could be too dystopian, one could revolt at the thought of vertical cities being classed as a utopia and what Lang and Kettelhut produced far from what a futurist would have wanted. However, if one looks at the futurist Manifesto one can only begin to believe that to them dystopia is utopia, as point seven of the manifestos exclaims “There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character” also saying there is no beauty without hardship or pain a distinguishing characteristic of a dystopian society (Marinetti, 1909). This then could pose question around the intentions and reasoning for the creation of this ‘Metropolis’ anti-utopia; what aspects of late 1920’s initiated Langs desire to produce such a rugged extraction of existing social ideals? Some could consider that lang wanted to create an apt metaphoric representation of the social class divide within the existing society, maybe even using this as a warning of what may come if the issues are not rectified. Within an article written on this question Deidre Bryne voiced their opinion that metropolis’ subdivisions of structure and community is “Metonymic of the class divisions in the urban society” clearly expressing this with strong belief, they continue to discuss their opinions using architectural examination more specifically the style of architecture. When comparing that of the ‘Metropolis’ film to that of early construction Manhattan they begin to dissect the idea of the Chrysler building expressing that it has many paralleled features to the capital building in ‘Metropolis’ stating “It testifies vividly to the dominance of capital over labour and articulates the power of moneyed classes to shape landscape and social spaces” (Bryne, 2003). This could mean then that the film is actively attacking the architectural development of Manhattan and the inevitable social divide that this was creating?

Advertisement

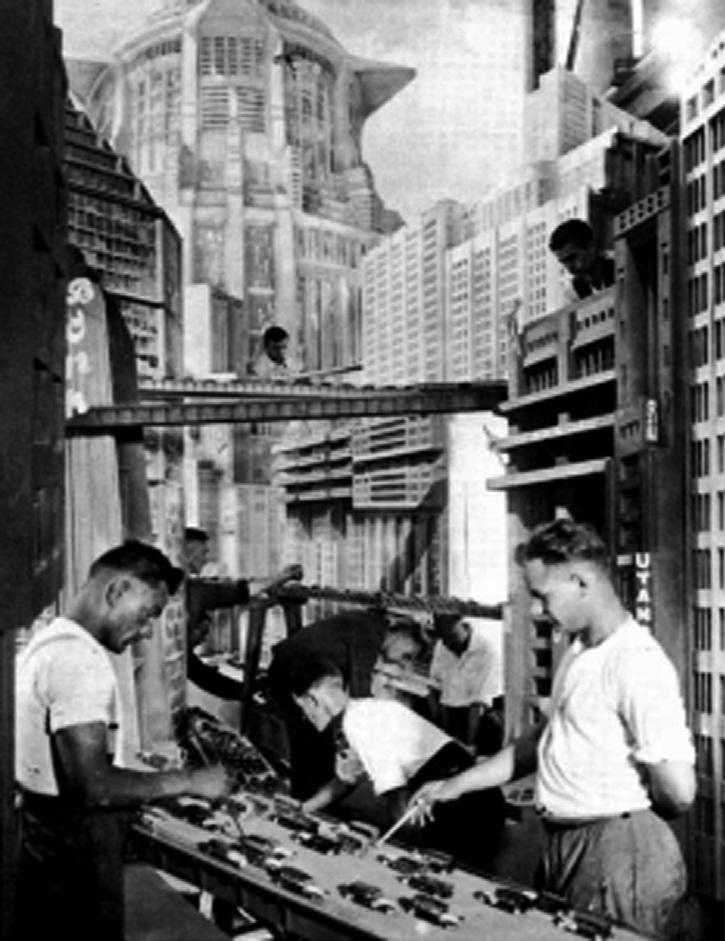

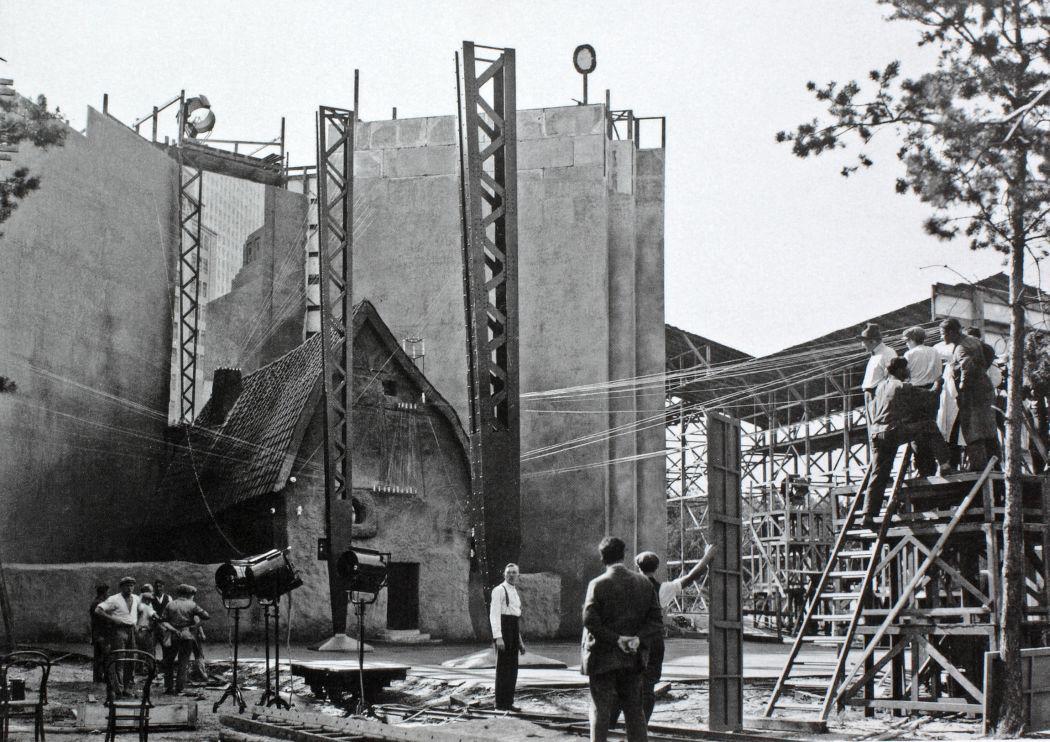

Metropolis, like Thais, was developed during a preliminary period in the 20th century causing the technological possibilities to be limited when filming and curating sets, this is clearly visible when seeing the design and construction of said sets. Their use of smaller scaled models to create scenes of larger objects (figure 10) to create these visuals for the city of tomorrow. It is also interesting to highlight the way in which they used these sets to record the scene, each camera man becomes immersed within the action along with the characters reflecting the skill required for a low technological film. Due to the impossibility of using CGI and other methods of digital adaptations the use of small-scale model work has been used, specifically for the icon shots of the vertical city, the capital building and the diverging roads and planes as seen in figure 11. This highlights the detail required to develop such a scene and sequence as each still of the city vista shots had each car moved one millimetre per frame, creating forty metres of film behind (Minden and Bachmann, 2002). This then impacted the ability of sequential manipulation allowing Lang to adapt and manipulate the city itself.

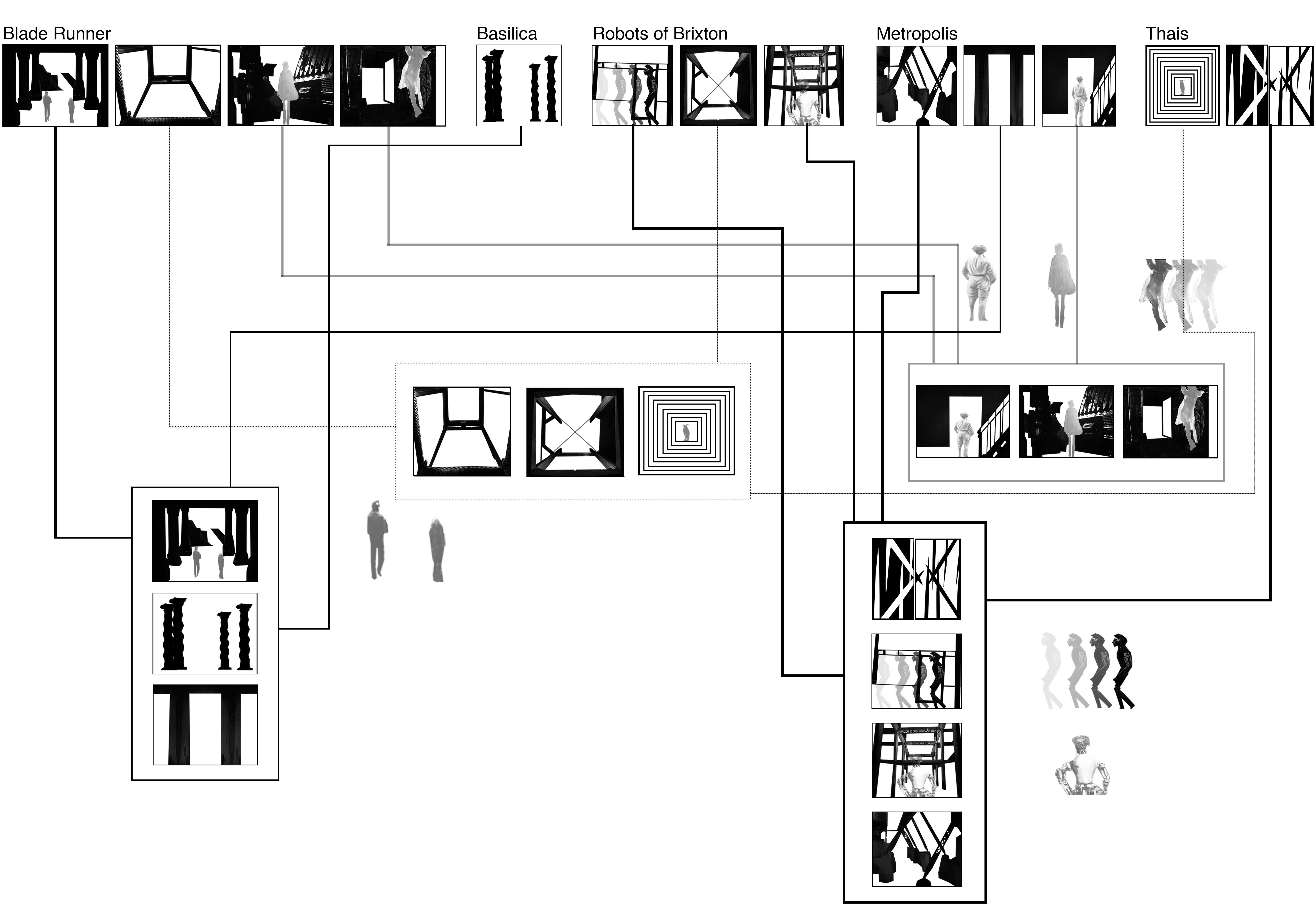

Alongside the smaller model scale sets Lang used larger physical scale sets, the use of fabrics scaffolding, and timber allowed for the temporary structures to become inhabitable spaces from large halls and gardens to small, enclosed rooms, each one dictating how the sequence of the cinema would develop. Like the previously discussed film (Thais and Robots of Brixton) the use of Bernard Tschumis sequence mapping will dissect the use of architecture within ‘Metropolis’.

Focusing on the explored sequence of ‘Metropolis’ (figure 12) it can be clearly realised that lang has used the architecture to induce a highly detailed framework. His use of combined open and enclosed spaces along with narrow and wide create a sequence that captures the witness. Towards the beginning of the film Lang introduces the lower level (home of the workers) in an enclosed narrow tunnel with only artificial lighting. Through using a combination of a large huddle of inhabitants along with the tunnel Lang makes the architecture the controlling factor forcing the inhabitants to follow the tunnel. This also creates the parallel between reality and prediction regarding the social hierarchy. Following the tunnel leads to a small lift shaft in which the characters are lowered into the “City of Workers” a city below ground constructed entirely of stone or concrete with minimal aesthetic to it. Moments later the scene is dropped, and a new sequence emerges now in the higher level of society in clean open garden, with plants that create structures to be inhabited. Creating archways standing on leg like structures (Russell, 2009).

Juxtaposing the garden Lang continues to delve into the smog of the underworld presenting the lead protagonist with a journey of self-reflection when standing at the foot of a large industrial machine. Due to the size of such a structure the scene no longer depicts the human as the focus of the sequence, in fact it demands its own stage, the set becomes the protagonist. The Sequence is cut to an end as the character flees back to the surface allowing for a new frame to begin in which Lang showcases the streets of the city, the vein like roads crossing in between structures he positions a view direct to the capital building which stands in the background this view focused and manipulated by the skyscrapers aligning prospectively in the foreground. Lang’s use of these control factors (foreground) brings structure to a large frame which could have been reflected as weak and liquidated in the eyes of the viewer, again the use of architecture and structure allows for the scene to be focused.

Produced in 1982 and directed by Ridley Scott this futurist dystopian adaptation of Los Angeles during the year 2019. As a production and futurist inspired cinema ‘Blade Runner’ attempts to divulge into the socio-economic issues of the current society in which it was conceived. Many academics have tried to create a clearer picture of the messages in which Scott was trying to relay, Douglas Williams stated his view was that ‘Blade Runner’ emerged to

“teach or worry us about the unprecedented and life-threatening complexities of our technologies, the social and political definition of their deployment and development, and the incoherence of our currently stereotypical attempts to escape from the repercussions of the world we see taking shape before our eyes” (Williams, 1988).

In saying this Williams may be attempting to announce that in his eyes the world he is situated in is controlled by a government who see no issue or fault in their actions and who believe they are doing good. As well as this Williams’ use of the phrase

“our current stereotypical attempts to escape” solidifies his position and ideals that the government are a party he believes the people underestimate in how far their roots go into societal control, that they have become an almost an unstoppable force. Whereas they are only being fuelled by corruption and greed. It could also be interpreted that the ones who are attempting to “escape” from their reality are in fact those who build the society, those who work the machines, like in Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’, those who live on the lower levels are the ones who will have to “escape”.

Ridley Scott’s use of futurist vertical architecture consolidates the idea of a dystopian future society riddled with over population, crime, poverty and economic decline. How then did Scott use the technological possibilities at the time (1982) to allow for larger scale sequences throughout his film? In a not so dissimilar way to how Lang, Scott began his development of the futurist style through early-stage imagery and sketches, the difference being the medium and way in which they were done. Shown in figure 13 is the proposed images by Syd Mead, an artist based out of Michigan USA, his designs had a modern futurist element to them due to the use of curves, dynamic lines and colour (Syd Mead, 2022). Mead’s detail and dedication to the style allowed for Scott to directly develop from sketch to physical model or set, examples can be seen in Deckard’s Kitchen and The Spinner vehicle as seen in the comparative figure 14. Not only then, did Scott use the advantageous technologies but also the modern artistic abilities of his peers to generate mocklife renders of his vision allowing for a more enriched Sci-Fi film. Even though Scott had access to greater technologies to that of Lang, he also adapted the uses of scaled models to create the larger cityscape scenes along with the flying automobiles. In a very similar way to Lang Scott created the city reimagining through large models (Figure 14) in doing this it is clear to see that while the technological advancements in colour film, minor digital animation and artistic rendering are prevalent it has not been further developed to the point of constructing large city scaled sets using

CGI, much like in ‘Robots of Brixton’.

Continuing to the consideration of architectural input on the sequential narrative, figure 15 is a Tschumi influenced breakdown of frames throughout the ‘Blade Runner’ film. Is the architecture an influential part of the sequence produced? While it can be considered that the set design is controlled largely by camera angles and focus due to the abstract and odd close ups used by Scott to highlight facial expressions of each character to convey the emotion within the dark and hazy scene (Kellner et al, 1984, pg. 4). As a counter to this argument however, the sequential mapping does highlight multiple frames in which the architecture has directly controlled the scene. Scott’s use of smaller box like rooms force the frames to be enclosed making the viewer feel as though they are trapped within not just the room but the city. Scott also develops an idea of enclosure within the streets of dystopian Los Angeles through the exaggeratedly tall structures and the narrowing of footways, this also adds to the idea of overpopulation as more structures are required to house more civilians. Architecturally Scott has a combination of frames throughout the two-hour film, in which he uses large scale sets, office and living spaces as well as smaller spaces inside vehicles creating obstruction in the foreground.

The opening scenes of the film are mostly frames moving through the large city controlled by the skyscrapers around while it follows a flying vehicle small in comparison to the buildings. Again, the architecture becomes the solid and the vehicle the character navigating through. Views then shift to the cockpit of the vehicle showing distant images of the exaggerated city around but enclosed and blocked by the control panels of the dashboard. Not only could this create the element of imprisonment but the idea of the impossibility of movement a perception of weakness in comparison to that which stands in the background. Continuing the sequence begins to enter the capitol building, the interior seems to parallel the exaggeration of height as seen in the cityscape, long halls and columns create directional manipulation of the spaces pushing Deckard, the lead protagonist, further into the building and further into the chronological journey, this is further suggesting that the architecture is directing the sequence. Structurally the style of architecture from external to internal changes, the external being futurist, clean lines and Manhattan esc while the interior becomes almost Egyptian through the use of towering ceilings with large columns, the style similar to that of the Mayan pyramids (Yuen, 2000, pg. 8).

Deckard later enters a chase with an antagonist through the tightly packed streets here Scott has used the overpopulating civilians as the main source of control for the protagonist’s path. A decision that differs to that previously seen; this could be suggestive of Scott’s desires to once again express his view of the societal issue seen within major cities such as Hong Kong and Tokyo, both are high on the list of population density causing a huge economic and environmental crisis due to the increase in carbon emissions and rising temperatures (Dukes, 1971). Scott’s use then of the civilian people as the control factor within this frame of sequencing contradicts that of the argument posed in this dissertation, while the city does provide a structural encouragement in the background the foreground manipulation comes from the people. The evidence reviewed suggests that one cannot firmly say all cinema is completely manipulated by the architecture. However, one can suggest that throughout the futurist influenced film the architecture does hold a great deal of power over most of the sequences.