10 minute read

Research Methodology 02

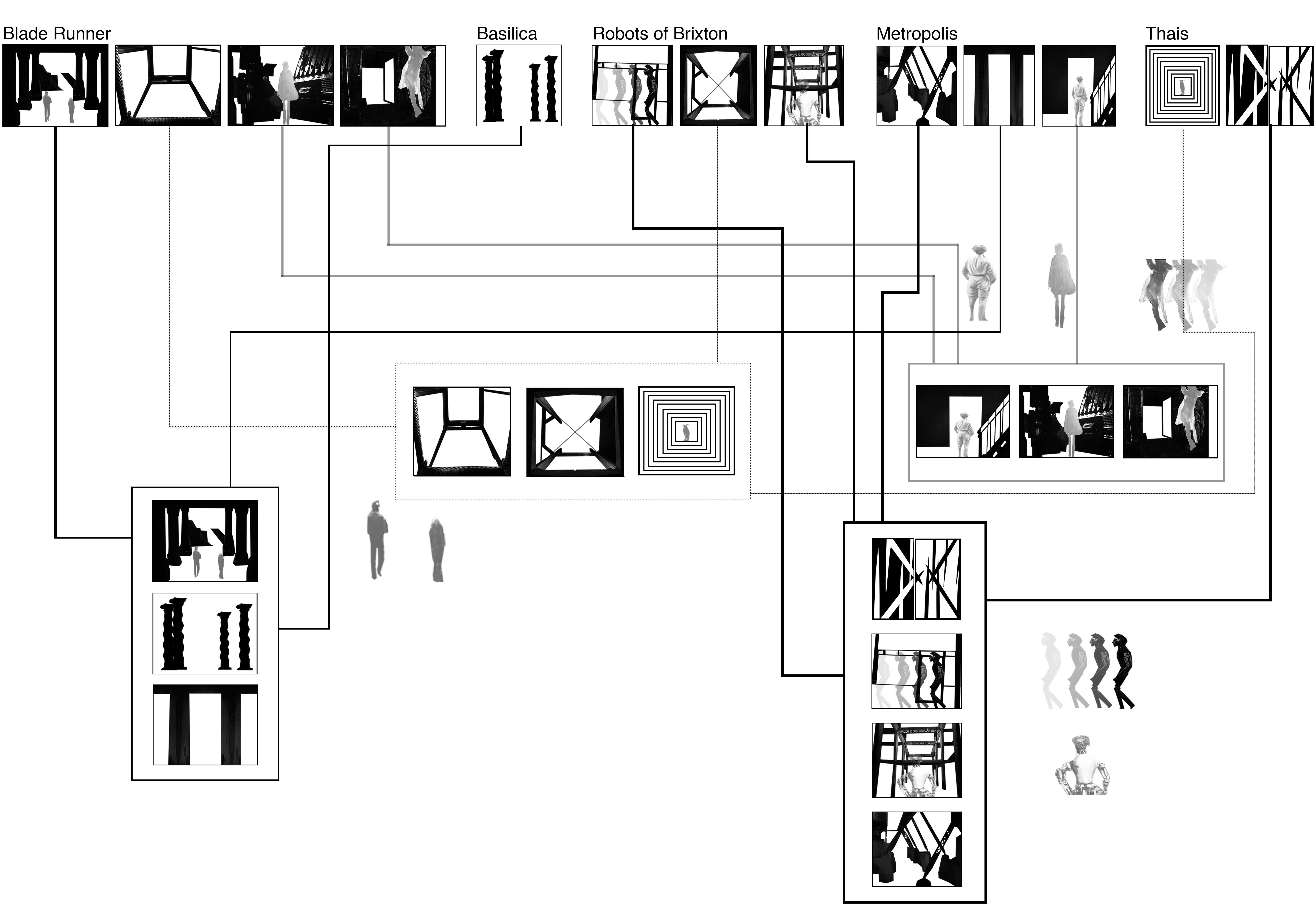

Throughout this dissertation multiple forms of futurist architectural cinema were diagnosed and dismantled to gain a better understanding of how architecture has been used as an influential factor in filmic sequence. By witnessing each form of cinema visible points within each one’s sequence began to appear to heavily involve the architecture surrounding it. This then led into research on sequencing within reality through Carla Molinari’s paper Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces. A fascinating paper aiming to develop and understanding on architecture and how it was manipulated by sequence at its core. It was then possible to compare Molinari’s statements to that of the futurists with the opposing views of the relationship between architecture and sequence. Expanding on this further dissection was done into the different films using noted architect Bernard Tschumis method of mapping sequences. Viewing each film and recording frames in which the architecture becomes an impactful part of the journey. The mapping then tore the subject from the frame to leave the structures behind leaving visible evidence of sequential manipulation. As a final method of consolidation to the found evidence a comparative combination map was developed finding moments of similar architectural influence between each of the researched cinema.

Vertical Architecture & the Birth of Futurist Film Chapter One 03

Advertisement

At the turn of the 20th century Italian artists and architects began to form a group solely aiming to define and plan for the new world. Their main aims were to take what is and begin to redefine it in a utopian or a dystopian manner. Using architecture and film allowed for the creation of influential and powerful representations of their view that can still be seen today. By developing moving pictures artists were able to develop more immersive experiences as it was originally considered that photography alone was “Cold” (Luzzi and Carey, 2020). A prime example of this was the reimagining of cities by architect Antonio Sant’Elia in his artwork, Housing with external lifts and connection systems to different street levels from La Città Nuova, 1914 (figure1). Aiming to conceptualise the inhabitation of people into the industrial plain by exaggerating the cities vertically. Sant’Elia’s depictions of the large housing block is a clear example of a dystopian view of the future due to its massiveness, and its lack of coherence with the natural landscape around. Le Corbusier later began to design through the medium of futurism with his plan for the reimagination of Paris (Ma, 2017). Could Le Corbusier have been right through his reimagination? His aim being to redefine Paris as a utopia or a way of “Looking for a suitable decomposition of a control problem by creating a hierarchal decentralization of the society” this quote demonstrates the idea that the power would become shifted to the community as there would no longer be a single form of control. Architecture allowed this to become reality through the largescale redefinition of current public and private inhabited spaces much like Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin (figure 2 and figure 3) (Mauro and Di Taranto, 1990). Would this have created a brighter more community-based utopia or a darker more solemn dystopia, “Societies and or places worse than the ones we live in” (Moylan and Baccolini, 2013). One could not say for certain whether it would have been a utopia/dystopia due to the conceptual nature of the designs. Would it not then be better to discuss whether the plans would be compatible with nature, or would they become disassociated with it?

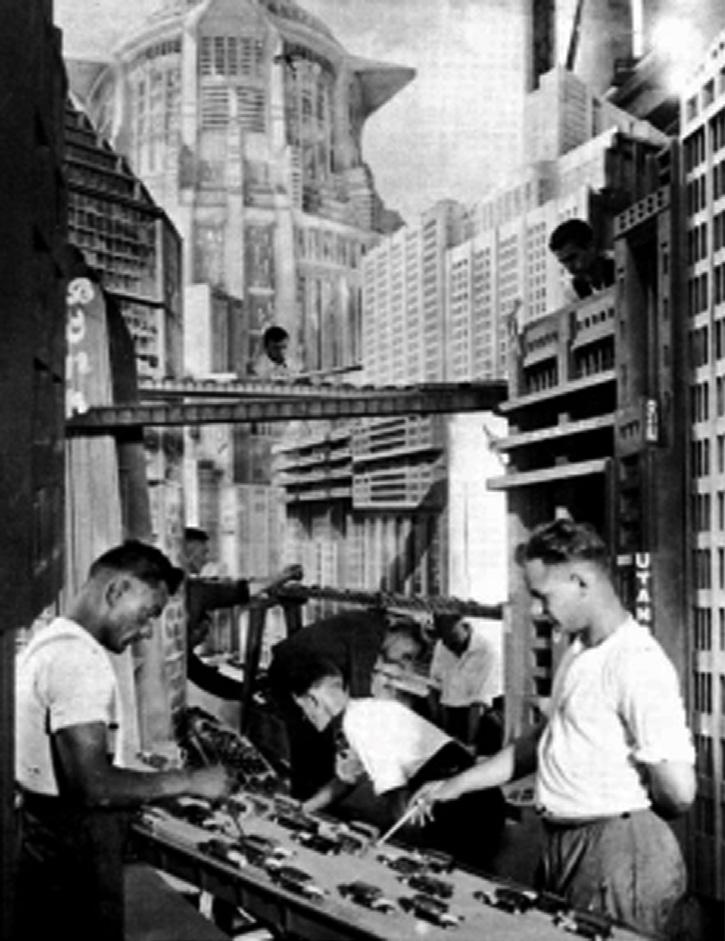

In Le Corbusier’s reimaging of Paris, a key visible element is the number of vertical structures emerging in a grid like formation. As mentioned previously, it is interesting to consider how architecture can develop the environmental cues of a utopian/dystopian future. With the use of architecture one can control the film, the emotion, focus and scale of each scene with its adaptations of the structural orientations. Films such as Fritz Lang’s metropolis uses vertical scale to create an adaptation of societal hierarchy by introducing a physical division in height as seen in figure 4 and figure 5. Placing the rich at higher floors than the poor, a concept and societal norm that can be seen in today’s cities (Sadowski, 2016). This theory supports the idea that architecture is an influential party in the development of cinema as the way in which utopian/dystopian futures are represented in films exaggerates what can be clearly seen in societies over the last century as metropolis’ have developed and grown, Contextualised in Lang’s film Metropolis (1927)

How Does the film set influence the sequence? Looking back into the idea of futurism allows for the question of sequence and influence to be answered. Anton Guilia Bragaglia’s film Thais, filmed in 1917, used a different approach to cinema in which architecture influences film through focus and sway of where the watcher places their attention. The use of doorways, corridors or windows draws the viewers’ attention to the smaller details creating a more intense sense of emotion. The sequencing techniques can be seen in Bragaglia’s film, the only existing futurist film, which throughout its cinematic progression begins to increase the focus of attention from the wider story to the main character through changes in set design and layout and the position of the character followed using camera positioning and zoom allows the viewer to become immersed in the film (Re, 2008).

Enrico Prampolini was tasked with the curation of each set; his desire was to use the movement of futurism to enable him to abstractly redefine the way cinema is perceived. (Berghaus, Pietropaolo and Sica, 2018) Through the progression of geometric architecture Prampolini begins to add elements of chaos aiming to highlight the descent of the Slavic Duchesses mental state. He uses this abstraction of shapes to create depth within each scene carrying more and more intensity along with them. figure 6 represents this use of geometry and depth as it maps the final stages of the film, articulated in a style influenced by Bernard Tschumis sequence mapping. As the film progresses the sharpness of these geometric shapes begin to appear more powerful and impactful on the scene. Referring to figure 6 and comparing the first scene, containing art deco inspired triangles, and the final scene, composed of sharp jagged steel framework, it can be seen that Prampolini was influencing the narrative and sequence with his composition of set design. One could reflect on this change in materiality to mean a change in mental state, the Duchess appears calming and ‘regular’ much like the triangular shapes. However, by the final scenes she could be considered to have evolved into something harsh, cold and erratic much like the collapsed steel framework. Following on from the previously discussed idea, the steel bars used by Prampolini can be seen to be acting as a form of imprisonment for the duchess. As the set design can be considered a metaphorical tool these ‘prison bars’ may have been used to express a physical solidification of the Duchesses guilt and her underlying desire to be held accountable for what she has done. Slowly the sequential progression then sees the ‘prison bars’ beginning enclosing upon her trapping and killing her.

Finally, when looking at Giulio’s film, due to the lower access to technology, the sets themselves must be reduced in scale. This could have acted as a barrier disabling any opportunity for larger scenes and therefore reducing what could have been contained in each space. One side of this view is that the film suffered because of this however, another side of the argument see this as Prampolini’s saving grace. Due to the reduced size the intensity and quality of artworks forged one of the most influential movies in cinematic history showing true skill to control such a small space in such a way (Marcus, 1996).

Architecture as the Influence of Sequence or Sequence as the Influence of Architecture

Chapter Two 06

Sequencing as discussed by Carla Molinari within her research article Sequences in architecture: Sergei Ejzenštejn and Luigi Moretti, from images to spaces is determined through montage and imagery which is described as “a key theme in modern architecture” (Molinari, 2021). Where then can this ‘Key’ factor of architecture be influential in relation to cinema and sequence. Molianri focuses on more traditional architecture when dissecting the art of montage by looking at noncinematic forms of architectural montage, initially engaging with Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Baldachin in the basilica of Saint Peter. While beautiful architecturally, the Baldachin forms a journey with its adaptation of eight images or stills. Molinari aimed to use this as evidence to support the idea that architecture can be manipulated by the sequence. This creates an opposing view, in a manner, to that of the futurists who aimed to use architecture as an influence on the sequence. Early within the article, research into other architectural opinions of montage began to be cut apart specifically that of luigi Moretti, who looks at the idea of architectural forms as aids to that of montage by saying: “Architecture is understood through the different aspects of its form, that is in the terms of which it is expressed…. structure of internal spaces, density and quality of materials, geometric relationships of surfaces” in his paper Structures and spaces (Moretti, Bucci and Mulazzani, 2002). Morettis listing of architectural expressions highlights the use of “internal spaces” and “Geometric relationships” both of which could be considered as aspects of cinematic architecture. As discussed previously in considerations with Bragaglia’s Thais the visible use of geometric surfaces and internal spaces are key visual and physical constructs that aided in his representation of a classic opera. Continuing in the breakdown of montage and sequence Molinari begins to consider representations of movement through the Basilica. Using Morettis diagram of sequence (figure 7) she could be wanting to define the movement through a sequential space the path around which architecture is erected, backing the claims that structure bends to the will of the sequence. Morrettis use of the term “Form” combined with the use of “reality” shows that his mapping of the journey is a considered approach to the viewers interactions within a given space. The process from entry to exit is defined by contextualised by what forms are presented to the subject, a doorway or a turning for example. Something similarly discussed by Bernard Tschumi in his article ‘Sequences’ in which he discusses that the “The route is more important than any one place along it” he is clearly stating that the journeys “route” is the influential factor of the sequence (Tschumi, 1981). Could this idea then be considered as Tschumi declaring the movement of the character through a scene to be the crucial factor within the journey? If so, then it may be said that the architecture that influences the direction of movement is in fact more significant than that of the route through, almost consolidating the theory that the architecture commands the sequence.

Later within the ’Sequences’ text Tschumi continues his breakdown of the narrative by discussing the implementation of “Frames” into the sequence. He expresses that “the content of congenial frames can be mixed, superimposed, dissolved or cut up giving endless possibilities to the narrative sequence” by saying this he is making comment on the ability of physical or imaginary parameters that can be used to change the direction of the narrative (Tschumi, 1981). One could consider the conceptual idea of “frames” to be that of the physical architecture, the implementation of architecture becomes the solid that controls the sequence. Exploring further Tschumi’s theory of mapping it can be said that it is possible to sequence through the use of physical architecture, figure 8 shows an example of his mapping technique. If this is a strategy of mapping the sequences in reality, could it then be used in an effective way to map the sequential processes of film?

Furthering the idea of Tschumis sequential mapping and its possible implementation into film, one must investigate other futurist inspired filmography and dissect how the architecture has dictated the directional movement of the sequence. Directed by Kibwe Tavares in 2011, the Afrofuturist film ‘Robots of Brixton’ became a highly discussed representation of the future, that aims to forge a dystopian representation of the poverty and disassociated social hierarchy of London life (Bould, 2019). Throughout the sequence it begins to pan to and from historic outbreaks of racism and discriminatory rioting within the community of Brixton. Kibwe uses interpretations of futurist brutalist architecture that looks to be parasitic in its technological nature, possibly imitating the implied governmental view towards the black community of Brixton. Figure 9 Shows a narrative breakdown of the cinema previously discussed in which Kibwe begins his narrative sequence through an aspect view of the main protagonist, who navigates through the architectural narrative. To fully study how Kibwe has generated this sequence one must tear the character from the journey to fully understand sequential make up of each scene, to view the architectural factors of the set. Robots of Brixton as a narrative follows that of a lead protagonist embodied through a “skinny and dully looking” humanoid robot who walks the streets of the new Brixton. Kibwe uses the architecture of the set to influence where the character moves, the diversity of camera angles, zooms and frames allowing the watcher to experience this journey for themselves. To open the narrative Kibwe generates a close zoomed focus of the lead robotic protagonist peering from an enclosed bus in transit, passing in the background shows glimpses of the dystopian decayed Brixton and its “retrofit architecture” (Bould, 2019). Continuing the journey the figure enters an enclosed market corridor, structures running either side shrinking the possibility of directional change, forcing them to move forward through the narrative. Furthering on and moving past this junction to an open park in which the camera focuses on the solid void of a bench on which a robot sits, thus forcing the scene to freeze behind this blockade, creating a juxtaposition between the background (open park) and the foreground (solid void). Once through the park they enter a large skeletal concrete framed structure, a large empty space controlled by the architecture. As a set it allows possibilities for the protagonist to travel around the space as a framework, the position they move to will be supported or manipulated by the architecture. As the concluding frame to this sequence of narrative Kibwe forces the frame into the robotic eye of the protagonist enclosing all room for sequential change and forcing the journey to an end. In reflection of this sequence, the design of the architecture is the clear boundary throughout, the solid dictates the spatial void.