1 COMEDY ISSUE LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS NO . 17 QUARTERLY JOURNAL

2 3 stanfordpress.typepad.comsup.org Living Emergency Israel’s Permit Regime in the Occupied West Bank Yael Berda BRICS or Bust? Escaping Middle-Incomethe Trap Hartmut Elsenhans Salvatoreand Babones Te Limits of Whiteness Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race Neda Maghbouleh ArabAmerica’sRefugees Vulnerability and Health on the Margins Marcia C. Inhorn 125 YEARS OF PUBLISHING STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Stanfordbriefs Anchor Babies and the Challenge of Birthright Citizenship Leo R. Chavez What Is a Border? Manlio Graziano From Seagull Books Taste Giorgio Agamben Agamben is the rare writer whose ideas and works have a broad appeal across many fields, and with Taste he turns his critical eye to the realm of Western art and aesthetic practice. Cloth $20.00 DrillingHardthroughBoards 133 Political Stories Alexander Kluge Kluge unspools more than one hundred stories, through which it becomes clear that the political is more often than not personal. Not just his newest fiction, Drilling through Hard Boards is a masterpiece of political thought. Cloth $30.00 Lions Hans Blumenberg Lions collects thirty-two of Blumenberg’s philosophical vignettes to reveal that the figure of the lion unites two of his other great preoccupations: metaphors and anecdotes as non-philo sophical forms of knowledge. Cloth $27.50 Collected Poems Thomas Bernhard “This unprecedented (in the English language) collection of Bernhard’s poetic output now offers an entirely new vantage on what made Bernhard such a classic writer. A major book, and a long awaited one, this should not be missed.”—LitHub Cloth $40.00 Distributed by the University of Chicago Press www.press.uchicago.edu

EXECUTIVE EDITOR: BORIS DRALYUK MANAGING EDITOR: MEDAYA OCHER

CHAD HARBACH , author of The Art of Fielding “It is always shocking to read something this good. . .Lisa Halliday is an amazing writer. Just open this thing, start at the beginning.”

CHARLES BOCK , author of Beautiful Children and Alice & Oliver “A beautiful reflection of life and art.” Kirkus Reviews (starred review) Also available as an ebook and an audiobook. SimonandSchuster.com

—LOUISE ERDRICH , National Book Award–winning author of The Round House “Lisa Halliday’s debut novel starts like a story you’ve heard, only to become a book unlike any you’ve read. . . Asymmetry is a profoundly necessary political novel about the place for art in an unjust world.”

MANAGING DIRECTOR: JESSICA KUBINEC AD SALES: BILL HARPER BOARD OF DIRECTORS: ALBERT LITEWKA (CHAIR), REZA ASLAN, BILL BENENSON, LEO BRAUDY, BERT DEIXLER, MATT GALSOR, ANNE GERMANACOS, SETH GREENLAND, GERARD GUILLEMOT, DARRYL HOLTER, STEVEN LAVINE, ERIC LAX, TOM LUTZ, SUSAN MORSE, CAROL POLAKOFF, MARY SWEENEY, MATTHEW WEINER, JON WIENER, JAMIE WOLF COVER ART: MARTIN KERSELS front: TOSSING A FRIEND (MELINDA 3) , 1996, C-PRINT, 26 1/2 X 39 1/2 INCHES ©MARTIN KERSELS /

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: TOM LUTZ

45

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY Te Los Angeles Review of Books is a 501(c)(3) nonproft organization. Te LARB Quarterly Journal is published quarterly by the Los Angeles Review of Books, 6671 Sunset Blvd., Suite 1521, Los Angeles, CA 90028. Submissions for the Journal can be emailed to editorial@lareviewofbooks org. © Los Angeles Review of Books. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Visit our website at www lareviewofbooks org

Te LARB Quarterly Journal is a premium of the LARB Membership Program. Annual subscriptions are available. Go to www lareviewofbooks org/membership for more information or email membership@lareviewofbooks org Distribution through Publishers Group West. If you are a retailer and would like to order the LARB Quarterly Journal call 800-788-3123 or email orderentry@perseusbooks.com. To place an ad in the LARB Quarterly Journal, email adsales@lareviewofbooks org QUARTERLY JOURNAL : COMEDY ISSUE

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS NO . 17 NEW FROM THE WHITING AWARD WINNING AUTHOR “Asymmetry is a novel of deceptive lightness and a sort of melancholy joy. Lisa Halliday writes with tender laugh-aloud wit, but under her formidable, reckoning gaze a world of compelling characters emerges.”

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY; back: TOSSING A FRIEND (MELINDA 2), 1996, C-PRINT, 26 1/2 X 39 1/2 INCHES ©MARTIN KERSELS /

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: CELESTE BALLARD, SARAH LABRIE, ELIZABETH METZGER, MEGAN NEURINGER, ERIKA RECORDON, JANICE RHOSHALLE LITTLEJOHN, ALEX SCORDELIS, MELISSA SELEY, LISA TEASLEY ART DIRECTOR: MEGAN COTTS DESIGN DIRECTOR: LAUREN HEMMING ART CONTRIBUTORS: MEL BOCHNER, JOHN DIVOLA, MARTIN KERSELS, ALI PROSCH, AMANDA ROSS-HO, CASSIDY ROUTH, MAUREEN SELWOOD, STEPHANIE WASHBURN PRODUCTION AND COPY DESK CHIEF: CORD BROOKS

7 ESSAYS 17 THE FALL OF THE CINEMATIC MUSE by Ryan Perez 32 YET ANOTHER LOVE THAT DARE NOT SPEAK ITS NAME by Jonathan Ames 46 TOWARDS A HUMOR POSITIVE FEMINISM: LESSONS FROM THE SEX WARS by Danielle Bobker 74 THE MAGIC — FLOATING — MOUNTAIN by Karan Mahajan 86 DICK GREGORY...IRREGARDLESS by Peter J. Harris 100 WOULD DIE TO PLAY HARVARD by Kristina Wong 112 IRONY AND THE NEW WHITE SUPREMACY by Sarah LaBrie 125 BINGESPEAK by Alexander Stern FICTION 34 WELCOME TO MY STUNNING AIRBNB! by Mitra Jouhari 40 HOW FINALLY LEARNED SELF LOVE IN A POST NUCLEAR WORLD by Broti Gupta 59 ARCHES AND LAND BRIDGES AND PILES OF ROCK by Lydia Conklin 80 JOKE BETWEEN SOLDIERS by Carmiel Banasky 90 DREAM HOUSE by Demi Adejuyigbe 104 THE PARTICULARS OF BEING JIM by Amy Silverberg POETRY 28 TWO POEMS by E.J. Koh 43 TWO POEMS by Marc Vincenz 68 TWO POEMS by Mary-Alice Daniel 82 SCHRÖDINGER’S CAT by Megan Amram 92 TWO POEMS by Paige Lewis 108 TWO POEMS by Ruth Madievsky 120 THREE POEMS by Sharon Olds 137 TWO POEMS by Timothy Donnelly OBSESSIONS 31 GET IN BED by Danielle Henderson 73 A GOOD FEEL by Amy Aniobi 85 HEARTTHROBS by Zan Romanoff 96 BREAKFAST by Fred Armisen 98 SHAKE SHACK by Kara Brown 110 QUIET CAR JUSTICE IN THE AGE OF TRUMP by David Litt 134 SHELFISHNESS by Todd Strauss-Schulson COMICS by Lydia Conklin, Liana Finck, Charlie Hankin, and Jason Adam Katzenstein NO 17 QUARTERLY JOURNAL : COMEDY ISSUE CONTENTS

8 9 See why The New York Times calls Ploughshares “THEMINNOWS”AMONGTRITON Subscribe today! PSHARES.ORG Get a one year subscription for $35. C OLLEGE OF L IBERAL A RTS AND S C IEN C ES P ROGRAM H IG H LIG H TS Complete the 30-unit program at your own pace and earn your master’s degree in two years or fewer. Benefit from a comprehensive curriculum that explores everything from literature to composition studies to literary criticism to creative writing. Enjoy a versatile graduate program, designed to enrich students’ lives, solidify their passions, and prepare them for career opportunities. Access opportunities for editorial experience with Christianity & Literature the flagship journal housed within APU’s Department of English. P ROGRAM UNITS 30 A VERAGE C OM P LETION TIME 1 ½ –2 years L O C ATION Azusa, CA A PP LY BY J UNE 15 AND S TART T H IS F ALL ! apu.edu/english 21838 Engage Literary Culture from a Christian Perspective Azusa Pacific University’s M ASTER OF A RTS IN E NGLIS H equips graduate students with advanced knowledge in the field of literary studies. Emerging from an active dialogue between Christianity and literature, graduates are prepared as scholars, writers, and teachers for cultural engagement through the lens of faith. C ULTIVATING D IFFEREN C E M AKERS S IN C E 1899

FROM THE EDITOR

“A satisfying book and a way for readers to understand how performance and confession got from there to here.” —Popmatters.com

1011 Dear Reader, We went back and forth about whether this should be the “Comedy” or the “Humor” issue and eventually, as you can see, landed on the former. Comedy, after all, has connotations that humor doesn’t have. It implies a certain professionalism — it can of course, be a job and a big job at that; it also has an implicit goal. Comedy is meant to be funny or entertaining. Comedy also evokes its opposite — tragedy — and, in that evocation, lets its audience hope for a happy ending. It goes beyond something as amorphous as a sense. A sense of humor is certainly a good thing to have, more people should consider acquiring one, but right now the concrete seems more interesting. If humor is tragedy plus time, then comedy is humor plus politics, plus current events, plus social and economic circumstances. Comedy is humor plus the business of the world.

The range of pieces in this issue of the Los Angeles Review Of Books Quarterly Journal demonstrates the diversity of implications in that word. Here, we’ve included many short, funny stories as well as two different critical takes on the current state of irony. Jonathan Ames considers his inappropriate love for his dog, Fezzik, while a number of comedians and comedy writers consider their own obsessions. You will also find pieces here that are not very funny. Comedy and tragedy go hand in hand, no sense in ignoring that. But don’t worry about those yet because this issue also has comics, which you won’t find in any other edition of the LARB Quarterly Journal. You should, as is the custom, flip through and read those first.

something for every readerreader

—Publishers Weekly A companion to the highly successful What Works for Women at Work A workbook for women with practical tips, tricks, and strategies for succeeding in the workplace.

LETTERMedayaYours,

Coming soon! Avidly Reads: a series of short books about how culture makes us feel. NYU Press + Avidly nyupress.org/series | avidly.lareviewofbooks.org @nyupress nyupress.org

How the internet has transformed television, allowing for more diverse storytelling from voices like Issa Rae and other independent producers Intertwined stories of a famous map and its curious maker, offering new insights into the creation of empire in North America Poems that reveal a plucky, headstrong, yet intensely socially committed figure who infuses his verse with proverbs, maxims, and words of wisdom “A well-researched argument that offers a vivid perspective on a literary giant."

The Hatred of Literature William Marx TRANSLATED BY NICHOLAS ELLIOTT “[Marx] turns poets and novelists into eternal resistance f ighters defending from the margins an art without faith or law, a practice that has no stable de f inition or real place in society...It is thus a secret war that Marx describes, with humor and erudition worthy of Umberto Eco.” Marianne Belknap Press | $29.95

★ A Times Literary Supplement Book of the Year “[Kiberd] is as superb on Máire Mhac an tSaoi and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill as he is on Seamus Heaney and Derek Mahon. His erudition in both languages makes his essay on Michael Hartnet...a beautiful meditation on double-mindedness.”

12 13

KRIS COHEN 20 illustrations, incl. 16 in color, paper, $23.95

—Fintan O’Toole, Financial Times $39.95

The Fateful Triangle Race, Ethnicity, Nation Stuart Hall EDITED BY KOBENA MERCER FOREWORD BY HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

★ An Artforum Reading Selection

Politics with Beauvoir Freedom in the Encounter LORI JO MARSO 46 illustrations, paper, $25 95 Domestic Economies Work, and the American Dream in Los Angeles SUSANNA ROSENBAUM paper, $24 95 Ezili's Mirrors Imagining Black Queer Genders

Abject Performances Aesthetic Strategies in

LETICIA ALVARADO Dissident Acts 69 illustrations, including 10 in color, paper, $24.95

The Right to Maim Debility, Capacity, Disability JASBIR K. PUAR ANIMA 18 illustrations, paper, $26 95 A New Trilogy from FRED MOTEN: consent not to be a single being Black and Blur paper, $27 95 Stolen Life paper, $26 95 Available March 2018 The Universal Machine paper, $25 95 Available March 2018 Latino Cultural Production

Women,

OMISE'EKE NATASHA TINSLEY 8 photographs, paper, $25 95

The Benefciary BRUCE ROBBINS paper, $23.95 Unconsolable Contemporary Observing Gerhard Richter PAUL RABINOW paper, $22 95 Now that the audience is assembled DAVID GRUBBS 7 illustrations, paper, $19 95

Althusser, The Infnite Farewell EMILIO DE ÍPOLA Translated by GAVIN ARNALL Foreword by ÉTIENNE BALIBAR hardcover, $89.95

★ A Seminary Co-op Notable Book “Essential reading for those seeking to understand Hall’s tremendous impact on scholars, artists, and f ilmmakers on both sides of the Atlantic.”

—Glenn Ligon, Artforum W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures $25.95 After WritingIrelandtheNation from Beckett to the Present Declan Kiberd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS www.hup.harvard.edu new books from dukeupress.edu | 888 651 0122 | @DukePress | @dukeuniversitypress Never Alone, Except for Now Art, Networks, Populations

14 15 A Library of Laughs TO LEARN MORE: WWW.UCPRESS.EDU A landmark publication in American literature. The bestselling Autobiography of Mark Twain is an essential addition to the shelf of his works and a crucial document for our understanding of the great humorist’s life and times. “It feels like a form of time travel. One moment you’re on horseback in the Hawaiian islands—or recovering from saddle boils with a cigar in your mouth—and the next moment you’re meeting the Viennese maid he called, in a private joke, ‘Wuthering Heights.’” —New York Times “Twain is incapable of going more than a few paragraphs without making you laugh or think hard. Don’t loan this book out: you’ll never see it again.”—Bloomberg Pursuits ofAutobiographyMarkTwain Volumes 1–3 Editors of The Mark Twain Hardcover,Project $45 each Jack Benny and the Golden Age of American Radio Comedy Kathryn H. FullerPaperback,Seeley $34.95 Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture Rob Paperback,King $34.95 Also available as a free Open Access ebook Mock Classicism Latin American Film Comedy, 1930–1960 Nilo Paperback,Couret$34.95 Funnybooks The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books Michael Paperback,Barrier$34.95 Read Tidalectics. Buy at mitpress.mit.edu/larobUnboundbyLand-BasedModesTheoceanscovertwo-thirdsoftheplanet,shapinghumanhistoryandculture,hometocountlessspecies.Yetwe,asmostlyland-dwellinghumans,oftenfailtograsptheimportanceofthesevastbodiesofwater.Climatechangedestabilizesnotionsofland-basedembedded-ness,collapsestropesoftimeandspace,andturnsourfuturemoreoceanic. Tidalectics imagines an oceanic worldview, with essays, research, and artists’ projects that present a different way of engaging with our hydrosphere. Unbound by land-based modes of thinking and living, the essays and research in Tidalectics reflect the rhythmic fluidity of water. Edited by Stefanie Hessler Foreword by Markus Reymann

17 www.nupress.northwestern.edu “A new benchmark in Marx scholarship.” Four of the MusketeersThree The Marx Brothers on Stage Robert Bader Los Angeles Times Only a Joke Can Save Us A Theory Comedyof Todd McGowan “...a master class in comedy.”amasqueradingpsychoanalysisasmasterclassin—AnnaKornbluh STEPHANIE WASHBURN, CONGRATULATIONS, YOU’VE MADE A WONDERFUL DECISION (GRAPEFRUIT), 2017, ARCHIVAL PIGMENT PRINT, 16 X 22 INCHES

19

This scene is of course from James Cameron’s Titanic , and it crystallizes a certain romantic ideal: a strong-willed woman has been won over and she is finally revealing her most vulnerable (i.e., fully naked) self to the scrappy artist, inspiring a work that transcends the impending chaos. In the film, the scene takes place in 1912 around the inception of filmmaking itself, but it evokes a truly ancient dynamic: the artist and his muse. The artist may not always be so boyish, but he is almost certainly male. The muse is inevitably a woman and also an object of sexual attraction. Oh, which reminds me, this scene is soon followed by that other iconic scene: minutes after Jack draws Rose, the two lovebirds fuck in a car.

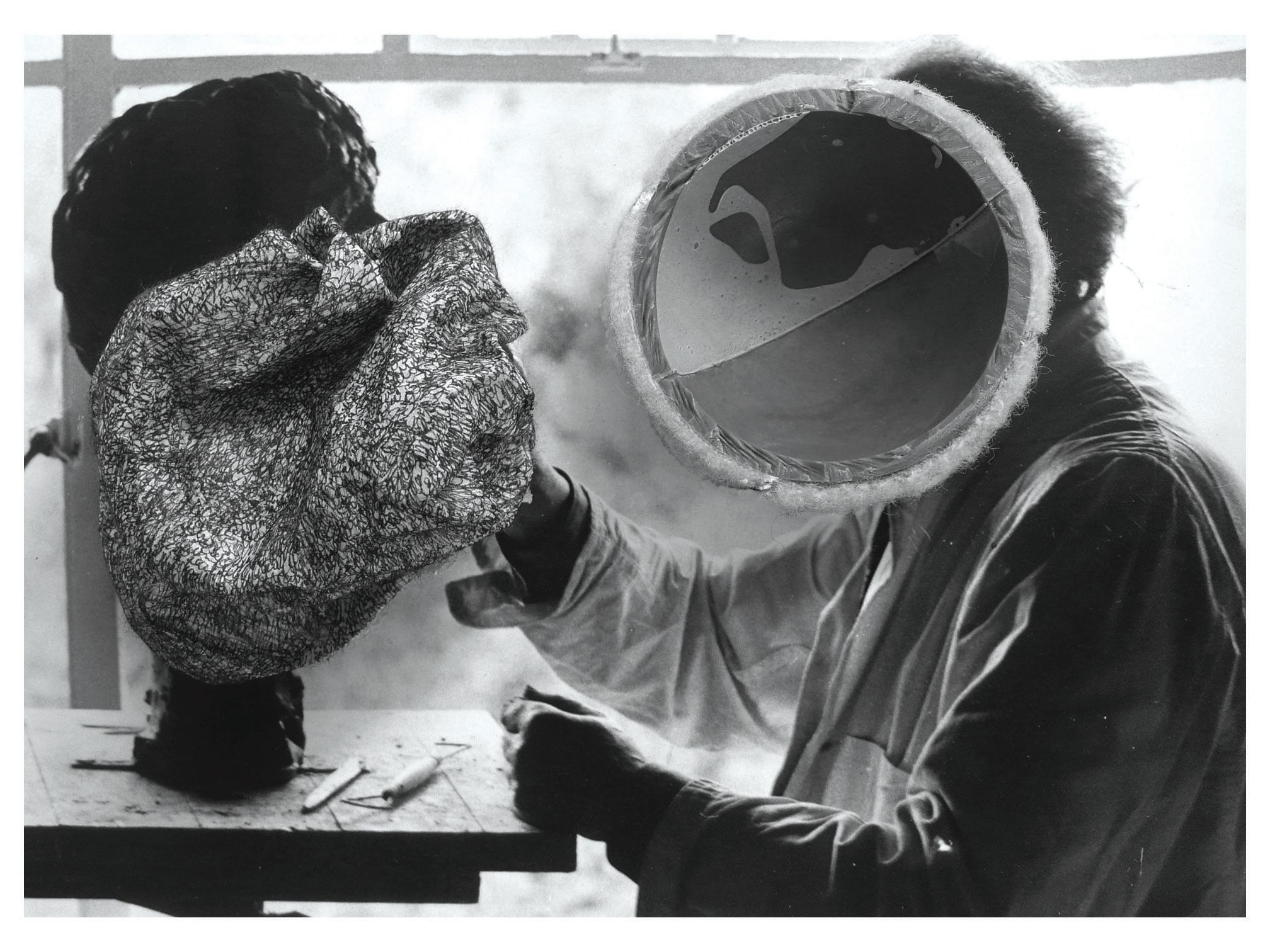

ALI PROSCH, BOXING MYSELF, 2010, LARGE-SCALE VIDEO PROJECTIONS, WITH SOUND, DIMENSIONS VARIABLE

The charcoal-based foreplay in Titanic is now 20 years old, but it has aged exponentially in the wake of the news around Weinstein, Toback, Haggis, Lasseter, Affleck, Affleck, Franco, Ansari, C.K., et al. If girls posing for boys once evoked the distant stench of skeeviness, it now outright reeks of it. “The history of cinema is boys photographing girls. The history of history is boys burning girls at the stake,” said Jean-Luc Godard, seemingly unaware that the cinema has as many burning stakes as history does, the worst of which is being the director’s muse. Finally however, it seems like the director-muse dynamic is not just

THE FALL OF THE CINEMATIC MUSE RYAN PEREZ

The scene is familiar, approaching iconic: “I want you to draw me like one of your French girls,” says the young woman. She reclines nude on a sofa. A delicate man-boy eyes her body, sheepishly requests a few adjustments to her pose and begins to sketch her. At first he draws slowly, then rather vigorously, all set to a tender musical score. When he reveals his achingly tasteful work, the woman and the audience are meant to swoon. As is written in the screenplay’s action line: “Rose gazes at the drawing. He has X-rayed her soul.”

Never mind the difficulty of navigating years of rejection, the Movie Actress must also clutch to their original passion for the craft through a Sea of Pervy Gatekeepers. Participation in Hollywood also implies a lust for money and fame, and so we tacitly accept this abuse as punishment for the terrible crime of wanting to be in pictures. We treat women auditioning for movies as if they were mercenaries smuggling nitroglycerine across the jungle: in the likely event of an explosion, they were warned it was a dangerous job. Before an actress even steps foot on her first professional set, the stage has been set for her abuse. Director and former actress Sarah Polley wrote one of the steeliest accounts of on-set harassment in her invaluable New York Times piece “The Men You Meet Making Movies,” observing the first wave of change in the industry with a keen wariness. Polley noted: “The only thing that shocked most people in the film industry about the Harvey Weinstein story was that suddenly, for some reason, people seemed to care.”

20 21 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

need not descend to the Ninth Layer of Hacks, where the likes of Victor Salva and Brett Ratner wander, to see the muse grift in action. The upper ranks of cinema history have seen all manner of cruel manipulation. Tippi Hedren long ago revealed the full spectrum of Alfred Hitchcock’s sexual obsession with her, from handsiness to outright assault (the abuse was well-corroborated by Hedren’s co-stars in both The Birds and Marnie). Bernardo Bertolucci outright admitted to tricking Maria Schneider into a non-consensual sex scene on the set of Last Tango in Paris for the sake of his own pretension. Schneider later said the experience left her feeling “a little raped.” Roman Polanski’s statutory rape began as a “photo shoot.” Even further back, Hollywood’s Golden Age has innumerable accounts of sexual intimidation, though much of it is still hidden in euphemism. In 1945, however, Maureen O’Hara gave an interview to The Mirror in which she stated, with an Irish kick: “Because I don’t let the producer and director kiss me every morning or let them paw me, they have spread word around town that I am not a woman — that I am a cold piece of marble statuary.”

If nothing else, Seduced & Abandoned shows how utterly full of shit most of these directors are. It’s enough to make you want to purge cinema history of all its shrimp-chomping ogres and expel the muse mythos once and for all. Yet the muse mythos persists precisely because it is perpetuated from within cinema itself.

For me, there’s one film that captures the skeeziness of directorial entitlement better than any other and it is, not surprisingly, a documentary James Toback made about himself. If you were unfortunate enough to catch 2013’s Seduced and Abandoned before HBO locked it in their vaults, you’ll recall the phantasmagoria of Toback lumbering around the French Riviera, rubbing elbows with fellow creeps at the Cannes Film Festival. With a gassy Alec Baldwin by his side, Toback interviews Bertolucci, Ratner, and Polanski, who laments that his movies are harder to finance these days (Hm, wonder why?). Toback and Baldwin are ostensibly there to pitch an ill-conceived remake of Last Tango in Paris to leathery tycoons, but they spend much of the movie extolling the virtues of Woody Allen and inhaling yacht buffets. Spoiler alert: Their horrible idea never gets financed and its proposed lead, Toback’s “muse” Neve Campbell, is thankfully spared having to be in another James Toback movie.

The common term for a female actor is of course, actress, a quirk of the English language that sets her apart and ever so slightly beneath her male peer. Though we’re often encouraged to take film seriously as an art form, the Movie Actress is rarely to be taken seriously as an artist. We even find the belittlement of her ambition funny. Even the most abused and exploited woman is said to be “eager to advance her career” or “get the part.” We’ve also long used the nauseating idiom “the casting couch” to suggest a business-minded exchange between producer and performer, an arrangement more like prostitution and less like rape.

Why is this mysterious art form so dependent on complete adoration and sexual submission to the artist? Though victims and perpetrators can be of any gender or job position, there is clearly a mindset that enables male filmmakers — especially the “complicated” or “troubled” ones — to abuse female collaborators.

patina, the remaining boundaries are crossed with minimum force. But it’s for my art, you Onesee.

There is simply no question more fascinating to the filmmaker than What inspires my creative genius? (Answer: A naked woman.) It’s a romantic theme at the heart of some masterpieces, like Fellini’s 8 1/2 and Godard’s Contempt . It also lurks in both self-aware Woody Allen ( Sweet and Lowdown) and no-insight Woody Allen ( Manhattan ). But it also stubbornly persists to this day in movies like Me and Earl and the Dying Girl and The Edge of Seventeen , both millennial bildungsromans in which teenage girls revere their male classmate’s mediocre filmmaking. In just the last six months, we’ve seen multiple tales of women-as-inspiration, from Angela Robinson’s P rofessor Marston and the Wonder Women , Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread , Louie C.K.’s I Love You, Daddy (gulp), to the most obvious of all, Darren Aronofsky’s mother!

Even as we decry abuses of power, we limply accept that abuse is part and parcel of the system, the result of craven careerism in an ultra-competitive field. In that acceptance, we diminish the humanity of the artistic professional who aspires to a means of self-expression.

And lo, by order of Essay Law, I must discuss mother! just because I’ve mentioned it and aso because I want to. Aronofsky’s movie was a lot of things: a blunt-edged eco-thriller, a totally sick diss of organized religion, and ultimately, the set where Darren Aronofsky RYAN PEREZ going through a rough patch; it is being upended completely. Just as 2008 brought the collapse of the housing market, perhaps 2018 will be remembered as the year the bubble around the Hollywood male ego had to burst. Perhaps we are finally witnessing the Fall of the Cinematic Muse. As a male writer (a cherished rarity to behold) with tangential links to The Industry (impressive of me), I’m privy to the scuttlebutt that indicates seismic shifts in systemic sexism. Even the most banal meeting now opens with five minutes of jittery persiflage about which powerful man will be the next to “go bye-bye.” But after months of meditating on conveniently vague notions of “industry culture” and “power dynamics” that enable sexual abuse, it seems like high time to specifically question the creative muse mythos in cinema.

Though Weinsteinian methods of sexual violence are obviously rampant, the preferred method of domination in the Age of Violence, as Jean Renoir once wrote, has been “to conquer by persuasion.” For those of the vaguely creative stripe (including the in-nameonly “creative executive”), the “muse” is a convenient trope. The woman in your crosshairs becomes “inspiration” rather than prey. Being a muse offers women greatness via association. It carries the divine, poetic connotation of Greek myth and allows men a direct link to the role of Artistic God. He is Pygmalion: art is a woman’s body, ownership of that body is a form of artistic practice. Once the pretense of sex-as-inspiration has an antique, European

22 23 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS RYAN PEREZ found a girlfriend. Mostly it is a corny-as-hell allegory where the auteur is elevated to the role of God and his much younger muse, played by Jennifer Lawrence, is denigrated to the status of a horror movie victim. The resulting spectacle is admittedly, supremely skillful, but stubbornly rooted in the traditional male perspective of women and art. The weird assumption at the center of mother! is that the sexual essence of a woman can be transmuted into a perfect artwork and that sexual and artistic potency are in lockstep. Observe the truly cringe-worthy scene in which Javier Bardem’s character impregnates his wife and then runs naked into his workspace inspired to create! mother! eventually resorts to grotesquery to get its point across (the film was hailed as “punk rock” by the likes of Aronofsky himself), but its view of artist and muse is just the same shit, different day. Are we supposed to give Aronofsky credit for realizing that women get abused in the artistic process? Okay, but any woman in Hollywood could have told you that, given the chance. In coincidental (but nothing is coincidental) fashion, it’s worth noting that Harvey Weinstein’s last public statement before his humiliation metastasized was a full-throated exaltation of mother! in serious film criticism journal Deadline.com . Weinstein spent his last breath defending a movie where a woman is betrayed, brutally pummeled, and replaced so that her abuse may be repeated on another female body. Is it possible that the helplessness and disposability of Lawrence’s character somehow fell in line with how Weinstein views the role of women on a film set and in his life at large? I am not a psychologist…but yes, definitely. The muse is a dying breed and not just because fighting creeps have become a cause célèbre. As female filmmakers find increased opportunity, a Muse Gender Gap has become painfully apparent. If muses are so important, why don’t female artists require a supple male body to drive their work? Who are the hunks that keep the Nicole Holofcener Inspiration Factory chugging along? Where are Jane Campion’s boy toys? Who has Tina Fey blocked the door and masturbated in front of? As of press time, none of these women appear to thrive on abusing their power. If there is such a thing as a Female Toback, we have not yet met her. Meanwhile, Lady Bird director Greta Gerwig has managed to crawl out of her Baumbachmuse pigeonhole to become one of the year’s most celebrated creative forces. “I did not love being called a muse,” said Gerwig in a recent Vulture interview, evoking the tone of a recently freed convict. The spiraling economics of the industry have also caused a natural erosion of the male filmmaker’s rock star status, greatly endangering his sense of entitlement to multiple muses. Director, producer: these were once the venerated titles of Important Men We Are Trusting With Millions of Dollars. They are now claimed by the entire Vimeo Generation. Film crews are the new garage bands: there is less money at stake, less power to wield, and, fortunately, less to lose by speaking out against abuse. Filmmakers, far from being invincible, are becoming expendable. The once-mysterious alchemy of cinema is bound to lose some of its sexual luster when crew lunch is Baja Fresh. As movies inch into the dainty realm of the fine arts, the muse mythos might follow — but with the same lack of authority it currently wields in sculpture, poetry, and (shivers) live comedy. (I should note here that the music industry cesspool remains relatively unstirred; R. Kelly is still enjoying a busy touring schedule and his victims — mostly women of color — are, not coincidentally, ignored for another year.)

24 25 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

RYAN PEREZ

Of all film genres, Noir ages best because futility never goes out of style. So naturally the most fatalistic warning against the old muse-artist dynamic can be found in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place . The story is based on a hard-boiled novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, one of the genre’s most successful female writers. Humphrey Bogart plays one of cinema’s great losers, a down-on-his-luck writer named Dixon Steele. Steele meets the love of his life, Laurel Gray, played by Gloria Grahame, on the same night he comes under suspicion for murder. Their ensuing relationship lasts long enough for him to crawl out of his alcoholic stupor and finish a script, but not long enough for the movie to find a happy ending. (It’s worth looking up the real-life marriage between Grahame and Ray, which was equally Bogart’sdoomed.)long-broken hack is momentarily mended by the love of a patient woman. For an instant, he can write. But she can’t keep him writing forever, partly because she never could in the first place. The muse is a mirage that vanishes when real life takes hold. In the throes of love, Steele writes a line of dialogue that doubles as the film’s crushing refrain: “I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me.” On the timeline of cinema, the few weeks are over. Death is underway.

Lest my pessimistic attitude help incite an industry-wide Gender War — a fate I’d like to avoid because I fear dying in it — let’s imagine a brighter future both off and onscreen. If cinema is to survive, it might very well be on a new kind of playing field, where professionals act professional out of pure survival instinct. Or, more fancifully, maybe even “tough” and “temperamental” artists can evolve away from a patriarchal muse dynamic to one where inspiration goes to and from every which way. There are, after all, precedents for it. One particularly heartening example is the professional and personal relationship between the brilliant Gena Rowlands and her spouse, John Cassavetes. Cassavetes was no woke bae by 2018 standards, but nonetheless, he directed his wife with respect. Part of their secret was to work outside the Hollywood studio system where Cassavetes was able to follow Rowlands from ingénue to middle-age, their work growing richer through the years. Similarly, Paul Newman directed his wife Joanne Woodward in four films from 1968 to 1987, the best of which was their first, Rachel, Rachel . Newman and Woodward were enormous movie stars with actual creative muscle and intellect (an unfathomable combination today). Both of these filmmaking partnerships were forged in the comfort of long marriages, but they exemplify a messy creative volatility that simply has no time for abuse. These were not sober, sexless ascetics. They were as challenged by love, lust, and fame as any of their contemporaries, and of course, their work reflected that. The heritage of cinema is theirs too. If we look back far enough, we can see the movies themselves warning us about the eventual demise of the muse. Martin Scorsese’s Life Lessons, the first part of the 1989 triptych New York Stories, is loosely based on Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler . It tells the story of a painter named Lionel Dobie, played by Nick Nolte, who is feeding off an angsty, mostly sexless relationship with his protégé and former lover, Paulette, played by Rosanna Arquette. She’s frustrated by his temperamental elusiveness but even more so by his gutless equivocation that her paintings are “nice.” Eager to know if she’s being strung along, she asks, “Can you just tell me if you think I’m any good?” Scorsese allows for Dobie to be a genuine talent, but also thirsty, manipulative, and far more trouble than he’s worth. Paulette is no wilting flower, but every bit as mercurial as her mentor. Once she drops him, Dobie cycles to a new muse. Life Lessons is impressive considering Scorsese distills these themes into a brisk, understated 45 minutes, exploring with greater honesty the same themes mother! needs over twice as long and 500 more day players to explore. In recent years, the showbiz partnership story I most often revisit is A Star Is Born . There are three versions of it already (and we face the eminent threat of a new one starring Bradley Cooper and Stefani Germanotta a.k.a. Lady Gaga) but it’s the 1954 George Cukor version that stands the test of time. Aging star Norman Maine, played by James Mason, discovers promising singer Esther Blodgett, played of course, by Judy Garland, and endeavors to make her a film star. As the years pass, her career skyrockets, while his founders. Their genuine chemistry is offset by a toxic jealousy that creeps into the film like poison gas. Cukor’s A Star Is Born is perhaps a better film about show business partnership, Hollywood power dynamics, and substance abuse than practically anything in movie history. It shows the need of a powerful man to lay claim to a woman’s brilliance, while also showing that a woman’s brilliance operates independent of a man and his needs or desires. It points to a tragic risk inherent in all artist and muse dynamics (or any “I can fix you!” relationship) — the muse might just take on a life of her own. Or, the artist might discover, to his chagrin, that she’s always had a life of her own.

A little about me: your host. I’m Katrina! I’m blonde, I don’t know what oceans are, and I have a million dollars physically on my person at all times. Since nothing bad has ever happened to me, I’ve devoted my life to various foundations and charities. Most recently, I sponsored a multi-billion dollar effort to turn all the little M&Ms at the Times Square store into the big M&Ms that can walk and talk! It didn’t work but I assure you, I’ve pulled scientists off of cancer research so they can work around the clock to figure out how to bring M&Ms to life. Currently, I’m on a three-month-long mission trip where I’m learning how to make blood diamonds. Every day, my shaman puts a bunch of loose blood in my asshole and I squeeze as hard as I can all day, every day. Pretty soon the pressure will turn it into a diamond! Someone call the police, because I’m smart! Architecture buffs, buckle up! This house is amazing. It was designed by Frank Lloyd Left, not to be confused with Frank Lloyd Wright. Frank Lloyd Left was trying to design an Arby’s but then they rejected his concept and now I live here! So if you’re wondering why the place is filled with the oppressive stench of roast beef, that’s why. The house is “minimalist” which is why it is so small and has no furniture. If you’re looking for the lightbulbs, there are two of them but you have to find them. Fun!

My name is Katrina, and if you’re reading this letter, it means you’re staying inside of my stunning AirBnB, located at the heart of an Urban Outfitters in Williamsburg. For the low, low price of $8,000 dollars a second, you too, can soak in the sights of Brooklyn as I, a white woman with absolutely no struggles behind me or ahead of me, experience it! But before you settle into my gorgeous chateau, please give this letter a scan for some ground rules, charges, and hot tips you can use along the way as you experience MY Brooklyn!

2627 MITRA JOUHARI

WELCOME TO MY STUNNING AIRBNB! MITRA JOUHARI with illustrations by Cassidy Routh

28 29 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

Some quick house rules — I hate to be “that guy” but you know the deal! First of all, no talking in my apartment. I consider my house to be a sentient being and based on her reaction to me practicing my scat-singing as loud as I can for four hours a day, she is scared of human voices and particularly hates mine. If you feel the need to speak, please do so only in the bathroom with the shower running so my house feels safe. It costs $15 to open a window and $40 to close it. Coffee is free unless you drink it! I’ve hidden a bullet inside of one of my Keurig pouches, so if you find that, please head over to the police station and turn yourself in for the murder that I committed.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, time for The Fun! If you’re in the mood to laugh, my poisonous Caucasian boyfriend’s improv team is performing every single night in different basements around the city! His team is incredible — it’s him, 25 tall men who look exactly like him, and one terrified, silent woman. He is SO talented and absolutely hates me. I know he’s going to make it big because he yells his standup jokes at me and I find them funny sometimes. If you’re feeling artsy, take a class on ME! My close, personal friend Rachel Dolezal will treat you to a painting lesson where you’ll learn colors the way she sees them: black is black and white is black! She’s incredible! And finally, if you’re feeling indoorsy, set my apartment on fire and wind down with my self-made candles. They all smell like spaghetti and will ruin your life. Oh crap, also! Before I forget — I told my college friend Brenton that he could come shoot his student film in my apartment at night while you’re sleeping. This is non-negotiable. He is doing a modern twist on the movie Whiplash (2014) where instead of hitting drums, the main character wants to get really good at henna tattooing. Everything else is exactly the same as Whiplash , except for they also added nine sex scenes and they will all be loud and graphic and MUST be filmed at my apartment while you are there trying to sleep.

MITRA JOUHARI

That being said, your deposit of $10,000 is non-refundable and I will give your deposit to ISIS under your name if you are not there for the entire night while they film. SO New Okay,York! I think that about wraps it up. If you have any questions, please feel free to never contact me. I will not help because I don’t want to. If you live through the night, you will get a personalized text message from one of the Real Housewives of Akron, Ohio! You’re KatrinaBest,welcome!!

3031

TODAY HAPPENEDNEVER E.J. KOH I’m getting my imagination’s tubes tied in Cancun. I’ve wanted to since 2008. No more sentences like: a school of stingrays dry out on the line; washed shoes grieve in the sink; my ovaries are meteorites turning, eventually they do explode; or girls talk in Technicolor at a circus in Jeju and they say, We’re not people, we’re sheeple. Before marry the whale-like quiet and pave over all obligation. Before I avoid murderous self murder, I leave you brown baby daschunds and a fact: if you’re near a crematorium and smell fresh-baked cake, it’s not cake.

RESIDENCE E.J. KOH The Denver museum shows a drinking bowl— peach-shaped porcelain, mother-of-pearl linework, glazed white ribbons—from the Joseon Dynasty of Korea’s ash-dry land roamed by bleary-eyed logs called grandmothers who search for their dead thirsty sons and the missing gourd and the drinking bowl. Water, they say, please. Why take residence here? The glass case has been cleaned. The light is fluorescent. On a card stand, it reads: Donated by Mr. America.

People love to say that you should not work in bed. Those people are my immediate enemies. Anything I’ve ever written that’s worth a damn was done horizontally, fluffy pillows at my back, laptop propped awkwardly on my chest and typing like a goblin while the heat of the hard drive threatens to burn a hole in my breastplate.

MARTIN KERSELS, FLOTSAM (TABLES SKELETON), 2010, COLORED PENCIL ON PAPER, 30 X 22 INCHES ©MARTIN KERSELS /COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY

My therapist would tell you that the longest relationship you’ll ever have is the one you have with yourself. She’s wrong. The longest relationship you’ll have is with your bed.

I have a nattering obsession with my bed. It took me three years to find the perfect comfort combination. This, for the record, is a separate pillow topper, electric mattress warmer, the best linen sheets you can afford at any given moment, a king-sized duvet on a queen-sized bed. When the time came to buy a new one, I put more effort into researching mattresses than I did my graduate thesis. I’m now so cozy it takes me three hours to get up every day, which my cat roundly protests by breakdancing on my face until I finally feed him. He always runs back and curls his little body right in the center of the soft comforter, though; even he knows it’s the best seat in the house.

As a child, I was forced out of my slumber every day by my grandmother. A slave to school schedules and cultural propriety, she flipped on the overhead light and bellowed: “Time to get up! Don’t make me come in here again.” Her methods were harsh, which only made me relish the time I spent in bed even more. I used to dream of scenarios that would allow me to stay in bed all day, but they all seemed to involve prolonged illness. The four-person bed in the original Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is my first memory of obsessing over beds. The grandparents just lived there, all day? Of course, in the movie this was meant to be convey abject poverty but to my young mind, it seemed like an impossible dream. I was actually sad when Grandpa Joe hopped up and joined Charlie in his adventure. Which would you rather do, if given the choice? Staying in bed and complaining with your best friends all day, or whirling around an acid-fueled sugar-coated nightmare town? I would choose staying in bed every single time.

33

OBSESSIONS: GET IN BED DANIELLE HENDERSON

My sex life is the biggest joke I’ve ever told, and my bed has been there through it all. Marriage, divorce, dating women for the first time, that unfortunate mustard incident — my bed was there to soak up the all the fun, the tears, and the Gulden’s.

Full disclosure: I should say I was asked to write something comedic for this comedy issue.

Full disclosure: What happened was this: Fezzik and I had been separated for hours, which is hard on both of us. Often, when I am gone for long stretches, I wonder why I haven’t heard from him. I look at my phone expecting there to be a text. Then I catch myself: “You idiot, he can’t possibly text you!” And yet I’m hurt and bewildered that he hasn’t. So on the night in question, I came home, eager to be reunited, and Fezzik raced about, stuffing toys in his mouth, which is what he does at his happiest. It’s like he can’t contain himself, his joy, his need, so he has to load up his mouth, which I understand quite well. My mother breast-fed me for only two months and I’m still upset about it. Anyway, after Fezzik exhausted himself dashing about, he hopped onto our bed, I mean my bed, and he lay on his back, put his paws in the air, and exposed his belly for a soothing rub. This is usually phase two of his welcome home to me. I looked into his eyes, which are quite beautiful, and I’m not the only one to think so. A Lyft driver, who was ferrying Fezzik and me from a friend’s house in Santa Monica, commented on their loveliness. He said, “It’s like they’re ringed with mascara.” I had never considered this, but it was an excellent and astute observation.

So I lowered my hand to rub Fezzik’s belly, but because I was staring moonily into his eyes, my hand went too low and lit upon his little furpouch, the tiny speed-bump that encases his p***s.

Full disclosure: I should say I have thought of touching him again. But I think I want to touch it only to do something bad and taboo, and then be forced to tell my analyst about it. So it isn’t so much that I’m compelled to touch it again because I want to touch it again, but, rather, I want to get in trouble. I want to be punished. I’m looking to create a drama for myself. My punitive super-ego hasn’t had much to work with lately. I’m sort of old and well-behaved at the moment.

Full disclosure: But I’m a little out of practice writing prose and to just sort of snap your fingers and write something “funny” isn’t that easy. I’m not regretting saying yes, but yesterday I was. I thought, “Oh, shit, I’m going to have to tell them I couldn’t come up with anything.”

Full disclosure: But I’m not sure if my filter is operating properly, which is perhaps one of the reasons — of the myriad — I’m in analysis four times a week for over three years. You see, I had to go for the oldAMES YET ANOTHER LOVE THAT DARE NOT SPEAK ITS NAME

3435 touch his genitals. And that one time was almost accidental. Emphasis on almost.

I knew immediately that a mistake had been made, but I let him my hand linger there one second too long, felt risqué and louche and outré, all things French, and then stroked his belly. But that one second makes all the difference in the world. It’s the membrane between heaven and hell, between sin and virtue.

Full disclosure: Surprising myself, I said “yes” immediately. I was in one of those moods where you think it’s good to say “yes” to things.

Full disclosure: What I thought I might write about — yesterday — is that sometimes I have feelings for my dog, Fezzik, that verge on the erotic. But that’s not really accurate. It’s more romantic than erotic. But one time — in a moment of great admiration and affection for his person and his cute little body — I did brush my hand against his tiny, fur-covered p***s, and I wondered if I would need to bring it up in my analysis. And would I also have to tell my analyst that more than once when Fezzik has yawned in my face I have wanted, fleetingly, to put my tongue in his mouth?

Full disclosure: I was told to write something comedic for this comedy issue.

Full disclosure: So that’s what I thought about writing yesterday, but I didn’t think there was enough there. Not enough story. I love my dog, and one time, and only one time did I with illustrations by Maureen Selwood

JONATHAN AMES

JONATHAN

36 37 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

In the morning, he emerges from beneath the blankets and kisses my face and cleans my eyes. Then I make coffee for us — well, for me — and we go to the backyard, and I read Pema Chödrön, whose books I love, and I think about things, like how the path is the goal, my ugliness is my beauty, and that pain is the great teacher.

JONATHAN AMES

And let’s not forget that sometimes this all goes in the other direction. For example, when I was a young boy, maybe six years old, my uncle’s very large and very hairy English sheep dog, Oliver, in a moment of lust and insanity, pinned me violently to the ground — this was in Pennsylvania — and mounted me, missionary style. I was wearing shorts, it was summer, and he rubbed his horrifying, slick pink thing — one of nature’s mistakes — between my bare legs, like a piston, bathed my face in hot dogbreath, and bit my shoulder, without breaking the skin. He was a rough lover, but good about the biting, and I sensed intuitively, despite my youth, that something sexual was happening, and I was terrified and screamed for help. My uncle came running, grabbed Oliver by the scruff of his neck, cursed at him viciously, and threw him off me. After that, the memory goes blank, until about my sophomore year in college.

fashioned cure to try to change myself before it was too late. But maybe because of a leaky filter, which still hasn’t been fixed, what I’ve touched on here — literally and otherwise — is most likely illegal, and I should have kept my mouth shut! Yet I also suspect I am not alone with having inappropriate thoughts about my dog. I mean I’m not saying other people are having inappropriate thoughts about Fezzik, though I could see why they would, like the Lyft driver, but what I meant was that I’m sure there are others out there who have strong feelings for their dogs.

Meanwhile, Fezzik sniffs the ground for raccoon urine, buries his bones in the dirt, and sometimes sits in my lap, like a sentinel, turning his head to the left and the right, smelling the breeze. It’s a soft and delicious existence, and I’m a soft citizen in a troubled time, but in these moments with Fezzik, when I quiet myself, I sense the expansiveness of life beyond the confines of my pinched and noisy mind, and I am not without hope.

Full disclosure: Yesterday, when it seemed that I couldn’t write this piece about Fezzik, I was rooting around in some ancient files on my laptop, looking to find something I could repurpose, and I came across an essay I had written 12 years ago, but never published. In this essay, I had included a journal entry from 1993. I was struck by the entry as something that the LA Review of Books might like because it’s primarily about writers and literary figures, and so I’m going to add it here. I know it’s a bit odd to pair it with my Fezzik love story, but what the hell? Why not experiment? It’s sort of like saying “yes,” which is how I got into this mess in the first place, a mess which is probably going to lead to my being arrested by the ASPCA or even the Audubon Society, though their concern is primarily for birds. But I imagine they would want to come to Fezzik’s aid if they get wind of this essay.

Full disclosure: Here’s some background to this diary entry: it was written one night while I worked the door at the old Fez (not short for Fezzik, sadly) night club on Lafayette Street in Manhattan. I was 28 and had published one novel, but had gone back to school, to Columbia, to get a degree so that I could teach.

Full disclosure: But about Fezzik. I’ve had him for six months. He’s a rescue. Maybe two years old. He was abandoned, left chained to a fence. He seems to be a mix of beagle, Chihuahua, and basenji. He has floppy ears, a tan body and a white neck, and his firm, little tail is always up and curled, revealing a discreet and fastidious anus. He weighs about 20 pounds and his fur is soft and lush. He’s loving and kind, introspective and silly, soulful and good. Naturally, we sleep together every night. I get into bed with a book, and he burrows under the blankets and goes down by my feet, though sometimes in the middle of the night, I find him curled against my lower back for warmth, and I feel lucky not to be alone in the world.

“No, they loved each other. It wasn’t a homosexual love. It was a love of souls. Man to man. You see, Jack loved Neal because Neal was a great cocksman and Jack was shy, a gentleman, he was like . . . like Victor Hugo and Neal was Rimbaud . . . and Jack gave Neal life, made him immortal.”

Saturday night I ran film at Madison Square Garden for Reuters and the Washington Post at the heavyweight championship fight; it was great. Backstage there were dogs in cages for the dog show the next day, and in the arena there were movie stars, sports stars, gangsters. Fans chanted “bullshit” after the quick knockout. Riddick Bowe was amazing: his long beautiful jab tipped at the end with muscle-like curled bright red glove. Bell tolled ten times for Arthur Ashe. Child star Macaulay Culkin came backstage to see the dogs in their cages. His hair coiffed, skin pale, very tiny, had private limo, looked at the dogs and smiled like a little boy. His father had a Hollywood ponytail. When they got in the car Macaulay sat up front and his parents in back, it was an odd reversal.

“What about Kerouac?”

“Him and Elvis in the bathroom. Is it true that Kerouac screwed Neal over?”

I got that job because my girlfriend back then, referred to as H. below, was a photographer for Reuters. I remember being with her when the first attack on the World Trade Center happened, about two weeks after this entry was written. We had been out all night and then slept very late, past noon, in her dark, cave-like apartment. It was February and cold, very little sun, and in overheated New York apartments you could almost sleep through a whole winter. Then her boss called, waking us. They needed her to rush down to Wall Street — someone had attempted to blow up the Twin Towers. Well, here’s the entry: February 10, 1993 I was hung-over all day, but rallied in the afternoon. Philip Roth lectured at Columbia today. I asked him, “Why are we ashamed to be Jews and how can we get over it?” He didn’t answer, just laughed. But I was serious. He said that he was excited by three cities: Newark, Prague, and Jerusalem. He said that he was intimidated by people with conviction. Me too. I don’t have conviction. He said, “Be ruthless, serve the writing, not the life . . .”

JONATHAN AMES

Last weekend: Friday night I was the bartender and waiter at a private party in Turtle Bay for the former ambassador to England. Mayor Koch was there, gave me a penetrating look, like he wanted to make love to me. I heard someone talking about Koch at the party: “He’s a terrible man, dividing the city, I listen to him on the radio still going on about Dinkins abandoning the Jews.” Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. was there for some reason. He wanted a whiskey, “One ice cube, mild.” He still had a thin moustache, his face was jowly but he looked dignified. I could almost recognize in him the young man he once was; I kept comparing him to the black and white vision of him in my mind from “Gunga Din” . . .

Well, that’s all to report. Look forward to being with H. tonight if she still wants to see me. I’ll bring a bottle of wine.

Being a student, I was always low on money and had many little jobs. In this entry, I talk about “running film” at a boxing match in Madison Square Garden. This was before cameras were digital, and so I was employed by a news service to run the film, between rounds, from the ringside photographers to a make-shift dark room in the bowels of the Garden. The idea was for them to start developing the images right away, but I only had to run one time since it was a first-round knock-out.

“Too good for words. He lived to write. Not for fame and money, just to write, he died in his bathroom and wrote his last poem in his blood.”

He was happy to talk, drunk, launched into a little monologue, “It was like the sun came into him and gave him energy. You don’t see that kind of energy any more, his arms, the biceps, the triceps, they were beautiful, strong, his belly was flat, and smiling, he was always smiling, always on, took the energy right from the sun . . . “

He didn’t want anything, and then this middle-aged reporter started talking to me, and he gave me the same look that Mayor Koch gave me, and he said that young gay men were not as frightened about AIDS, and then he added, “Sex is back in, you know,” and I said, “I never knew it completely went out.” I was quick with the oneliners that night. Kept sneaking drinks for myself.

Full disclosure: So many little things I could mention regarding that entry. Like the time I met Allen Ginsberg in 1986, on Avenue A in the East Village, late at night, and he told me to go to the Naropa Institute to study writing, and so I did, driving some guy’s VW van from New York to Denver, and then taking a bus to Boulder, Colorado, only to discover that the Naropa Institute was really expensive and I couldn’t afford any of the classes. This was before the internet, when you did things like drive cross-country to a school because Allen Ginsberg told you to, not knowing that you couldn’t afford it.

Michael Dokes, the loser, glowering out of the corners of his eyes, in body-length fur coat, leaned on his old handler and went into a limo after Macaulay. Went to press conference and watched Bowe with the circus of TV reporters. Saw MC Hammer and Joe Frazier – not walking too well; old boxers all damaged, their brains and balance loosened in their heads. Then Sunday I worked the door here at the Fez for the Neal Cassady memorial radio broadcast, a pathetic sort of tribute with old men trying to recreate lost youth and madness for stylish dead Nineties youth submissive in the audience. Snuck down a few times. Ginsberg was up on stage, trim, looking like a reformed congregation rabbi in his blue blazer and flowered tie and grey beard and wise kindly bald dome, reading his poetry about young boys’ hairless chests and buttocks; then Ginsberg’s old lover, drunken Peter Orlovsky showed up, fat, looking like an Archie Bunker crony, baseball hat, blazer, pocket bulging with pens. “I am a famous international poet,” he said to me, so that I wouldn’t ask him for the cover charge. His name wasn’t on the comp list. I said, “I know who you are. Don’t worry about the money. But for admission can you tell me about Neal Cassady?”

38 39 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

When I brought him the drink, he said, “Thank you, you’re too kind,” with great dramatic emphasis, like I had saved his life, and then he said, “I’ll put you in my will.” I said, “I’ll give you my name at the end of the party.” He smiled at me, his eyes twinkled.WhenIwent up to Mayor Koch to see what he wanted to drink, he extended his hand, he thought I was somebody at the party, I was wearing my blue blazer, but like a good servant I didn’t extend my hand to meet his and said, “Would you like something to drink, Mr. Mayor?”

4041 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

And how years later, I would see Peter Orlovsky, sitting in doorways, in all sorts of weather, always near University Place, and he had completely lost his mind and was quasi-homeless, but somehow, he lived a long time after Ginsberg died. And how at that same party where I served Mayor Koch and Douglas Fairbanks Jr., I also served Kurt Vonnegut, and I told him that he was the first writer I had ever loved, and he said it was kind of me to say that. But for some reason, I didn’t put that in the diary entry. And how the people who threw the party took me under their wing and gave me a spare bedroom in their house to use as an office so that I could work on my second novel, since the room I rented, where I lived, was too small for a desk. And how I would look out the window from my “office” and I’d see Vonnegut, who lived across the street, sitting on his stoop smoking, since his wife wouldn’t let him smoke in the house, and how on that same street was this mysterious high-end brothel, which 20 years later sparked the idea for my most recent book, a thriller where a young girl is saved from such a place. Well, I guess that’s about it. I’m running out of steam. Been writing for a few hours. And if you were here with me in my little house in Los Angeles, you would have heard me call just now for Fezzik, and you would have seen him come trotting into the room, where he is now sitting by my feet. A little yelp of some sort came out of him and he is looking up at me with his quizzical, beautiful eyes. It’s time to take him for a walk.

BROTI GUPTA

A love of self leads to a love of others, which leads us to stop using names like “Ugly,” “Stupid,” or “Little Rocket Man,” which will inevitably lead to a violent third world war with weaponry like we’ve never seen before. But just as important as how we see ourselves on the outside is how we treat our bodies — how we end up feeling on the inside. It’s fun to indulge in an ice cream cone or whatever’s left of the bag of flour in the freezer every now and then, but it’s also fun to test the radioactivity of the Farmers Market remains and get those natural nutrients flowing through our bodies. We have to get our bodies moving, so we can feel our blood circulate. Instead of just walking, we can jog…away from another nuclear target, which will help minimize radiation exposure. So, that’s the kind of woman I want to be from now on. I want to be able to do things for myself, and take care of myself. I want to go to the Ground Zero Spa, or the Ground Zero Acupuncturist, or this one Dave & Buster’s that survived everything. And, while Kim Jongun keeps launching his ICBMs, I’ll be launching my own ICBM campaign: I Care ’Bout Myself.

4243

HOW I FINALLY LEARNED SELF LOVE IN A POST NUCLEAR WORLD BROTI GUPTA

In this vapid world of Facebook, Instagram, and the pretty big nuclear explosion like an hour ago, it’s been hard for me to take the time to love myself. Like so many women, my inability to care about myself started when I was a teenager and my self-image was as weak as the level of nuclear warfare we were in at the time. One of these started to grow, and not the one I’d hoped. Every time I looked in the mirror, I judged myself. Are my pants fitting weird? Are my braces the wrong color? Is the Fire and Fury™ Protection Oxygen Mask my parents gave me making my forehead look big? Today, I dragged myself out of the rubble and to my mirror where I noticed small details on my face I hadn’t noticed before. My sharp, distinct jawline, my eyes that tell a thousand stories, my hair scorched from the explosion we never thought would happen. And I finally realized — there’s so much to love. Other people saw this in me before I saw it in myself (before all of our retinas burned out of our eyeballs and none of us could see more than just “relative shapes”). In fact, during those teenage years, my friends and I would sit by what were then known as “trees” but now known as “used to be where trees were, before North Korea aimed right,” and just call each other beautiful and amazing, but ourselves ugly and unworthy. Maybe if we could have treated ourselves like we treat our friends, we could have learned to be less critical of ourselves. And maybe through loving ourselves, we could inspire the country to love itself and stop instigating nuclear bombs over social media.

JOHN DIVOLA, 74V03, 1974, GELATIN SILVER PRINT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GALLERY LUISOTTI

45

You wanted taste. Long stretching lines that held a voice you could hear in your head, the timbre with a resonance of wit or the sufficiency of time. Something like that clock chiming beneath the stairs, or a soft, languid, wet voice that tickles the earbones. You wanted to reach in, to feel as the voice, to smell the herbaceous green on the sill, the clandestine weight of passion or, better yet, the perfume of Paris in autumn— yet, yet, something held you back. Your reason was a faithful dog whirring in circles around a single tree, snapping at imaginary birds. The line you sought, heavy from all that laundry of words, the sink filling up with swirling punctuation. And what of the in-between, where there are no words, where there is only space and silence to tell the story.

ODE TO AN POSTMODERNISTAGING MARC VINCENZ

THEopened.LAST OF THE ZEN POETS

46

JOHN DIVOLA, 74V02, 1974, GELATIN SILVER PRINT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GALLERY LUISOTTI —for M. Last night I was blinded by a sharp ray of light. Strange. In my dream was trying to catch a squall. And when awoke, feeling this urge to dance, I followed the leaves shaken loose along the riverbank. As the river pierced the valley with a booming rush, I found the moon in a fast contented sleep. It was a perfect moment to let my mind become still— for when I reached the coast I wrapped myself oyster-tight in the ocean calm and MARC VINCENZ

DANIELLE BOBKER “Laughs exude from all our mouths.” Hélène Cixous “Comedy, you broke my heart.” Lindy West In a bit about sexual violence in his 2010 concert film Hilarious (recorded in 2009), the nowinfamous Louis C.K. says: “I’m not condoning rape, obviously — you should never rape anyone. Unless you have a reason, like if you want to fuck somebody and they won’t let you.” I was delighted when I first encountered this joke on Jezebel in July 2012 in a post called “How to Make a Rape Joke.” Lindy West was responding to the social media controversy surrounding American comedian Daniel Tosh, who had recently taunted a female heckler with gang rape. West’s insightful essay later led to a 2013 TV debate with comedian Jim Norton as well as her best-selling memoir, Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman, where she describes the fallout of becoming one of the United States’s best-known feminist comedy commentators, including her subsequent, painful decision to stop going to comedy shows. In “How to Make a Rape Joke,” West wondered whether it is ever okay to approach sexual violence with humor. She wrote that she understood and respected those, like the woman who called out Tosh, for whom it wasn’t, categorically. The sexual assault of women poses a special problem for comedy, she reasoned, because it is an expression of structural discrimination against women. That is, unlike misfortunes such as cancer and dead babies known to befall people at random, if you’re a woman, not only do you face a one in three chance of becoming a target of sexual violence, but you will also likely be held at least partly responsible for it. To illustrate the inappropriateness of jokes about this kind of a situation, she drew a comic analogy between

Sex-positive feminists actively chose not to contribute to this climate of moral panic, focusing instead on unearthing the deeply embedded mainstream prejudices around sexual practices and fantasies. Instead of turning away, they faced sexuality head on, acknowledging debts to the small minority of people — sexologists, fetishists, queers, sex workers, erotic performers, and indeed pornographers — who had already begun exploring human sexuality in all its complexity, often with little socioeconomic support and at the risk of criminal charges. By many accounts, it was this unabashed approach to sex that led to the development and popularization of safe-sex protocols and consent education later in the 1980s.

TOWARD A HUMOR POSITIVE FEMINISM: LESSONS FROM THE SEX WARS

4849 patriarchal society and a place where people are regularly mangled by defective threshing machines and then blamed for their own deaths: “If you care […] about humans not getting threshed to death, then wouldn’t you rather just stick with, I don’t know, your new material on barley chaff (hey, learn to drive, barley chaff!)?” Compassion about a culturally loaded form of suffering would seem, automatically and intuitively, to preclude humor about it. Yet West’s own humorous reframing demonstrated what she ultimately decided: that you could be funny about sexual violence if you “DO NOT MAKE RAPE VICTIMS THE BUTT OF THE JOKE.”

In particular, Louis C.K.’s rape joke then earned West’s stamp of approval because, in her words: [It] is making fun of rapists — specifically the absurd and horrific sense of entitlement that accompanies taking over someone else’s body like you’re hungry and it’s a delicious hoagie. The point is, only a fucking psychopath would think like that, and the simplicity of the joke lays that bare.

Though her recent New York Times piece “Why Men Aren’t Funny” makes it clear that West now regards her defense of Louis C.K. as a relic, her sharp distinction between acceptable and unacceptable jokes in “How to Make a Rape Joke” set the standard for mainstream feminist discussions of comedy for a good five years. While I find West compelling, in my own efforts to navigate the contemporary feminist ethics of humor throughout this period, I’ve been resisting the impulse to draw limits. Instead, I’ve been looking back to the debates over sexuality that were central to North American feminism in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During the so-called sex wars, feminists agreed that sexuality had always been held in a patriarchal stranglehold but disagreed about what to do about it. The Women Against Pornography saw explicit sexual representations as the very basest mechanisms of female sexual oppression and so focused their energy on educating the public about their harms and prosecuting pornographers. By contrast, sex-positive feminists, as they came to be known, claimed that trying to shut down or cordon off unacceptable expressions of sexuality only exacerbated the problem. They argued that the history of criminalization and widespread fear of any sex but the reproductive, romantic, married kind had not only led to the marginalization of sex workers, lesbians, gay men, trans people, and many other so-called sexual deviants, but also cast sexuality as such into the shadows. Targeting pornography was therefore counterproductive. As Susie Bright, vocal defender of the sex-positivity movement and founder of the first women-run erotic magazine, put it: porn [can be] sexist. So are all commercial media. [Singling out porn for criticism is] like tasting several glasses of salt water and insisting only one of them is salty. The difference with porn is that it is people fucking, and we live in a world that cannot tolerate that image in public.

DANIELLE BOBKER

DANIELLE BOBKER

One of the major contributions of sex-positive feminism to our current understanding of sexuality was the recognition of seemingly counterintuitive forms of agency from below. Sexpositive feminists showed us the through line between the patriarchal suspicion of sexuality and certain feminist critiques of sexual exploitation. Though the fear of sex was originally and widely promulgated in medical, religious, and legal discourses, some of the alternative schemas of anti-porn feminists heightened the idea that most sex is inherently terrifying. For instance, Catharine MacKinnon’s view that “the social relation between the sexes is organized so that men may dominate and women must submit and this relation is sexual — in fact, is sex” — while it helpfully exposes sexual violence as a structural problem — also makes it impossible to distinguish consensual heterosexuality from rape. Sex-positive feminists turned to the less moralistic disciplinary frameworks of sexology, sociology, and anthropology. Inspired in part by the subversive theories of power of French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, they insisted that saying yes or no to sexual contact, including sexual domination, was a fundamental

50 51 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS correct” and, once the lines are drawn, “[o]nly sex acts on the good side […] are accorded moral complexity.” Wary of simply rerouting sexual shame, sex-positive feminists instead actively cultivated a nonjudgmental stance. This might seem the worst possible moment to advocate for an equivalent form of humor positivity, let alone with reference to a joke about sexual violence by Louis C.K. In the wake of the public exposure of numerous celebrity serial sexual abusers such as Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, the viral #MeToo campaign has uncovered thousands of male harassers and abusers, and pointed to millions of others as yet unnamed. Since C.K. confirmed reports of his nonconsensual exhibitionism, some of the feminist anger and despair that was already rippling across popular and social media is being directed specifically at the industry that gave him his power. Many mainstream feminists, not least West herself, feel more prepared now than ever to throw the bathwater of comedy out along with the many baby-men who have been cavorting in it. Yet, as I see it, it is precisely in the context of our well-justified outrage that humor positivity is most needed. Humor is a vital, elusive, and continually evolving aspect of human experience. Like sex, it has repeatedly served oppressive ends, but it is no more essentially or necessarily discriminatory an impulse than sexuality is. It is undoubtedly important that we probe and resist the misogynist culture of mainstream comedy. At the same time I propose a change in the way we personally and collectively engage with the material this industry trades in — that is, the jokes themselves. How might we ensure compatibility between the jokes we hear or make and the tools and concepts that shape our responses to them? How can we prevent our resistance to certain jokes from reproducing the (historically patriarchal) marginalization and stigmatization of the desire to laugh? If we get used to approaching jokes with trepidation, expecting offense, how might that wariness affect our political movements? In the current feminist conversation, these questions have begun to be raised in, for instance, Cynthia Willett, Julie Willett, and Yael D. Sherman’s “The Seriously Erotic Politics of Feminist Laughter,” Jack Halberstam’s “You Are Triggering Me! The Neo-Liberal Rhetoric of Harm, Danger and Trauma,” Lauren Berlant and Sianne Ngai’s “Comedy Has Issues,” and Berlant’s “The Predator and the Jokester.” My sense is that what we especially need now are some clear and concrete principles and practices for humor-positive feminism. Here are three lines of inquiry that I hope may help us to develop a richer set of responses to comedy going forward. Can we develop a more complex and flexible view of humor’s power dynamics?

There are of course, limits to the comparison of sex and humor, especially given that the impact of hetero-patriarchy on sex is much more immediately visible. Nevertheless, I would suggest that sexuality and humor are not merely analogous, but are in fact overlapping categories of feminist experience. Both are understood to be culturally coded but with powerful bases in the body. Like sex, laughter has historically been considered an unruly instinct, even by the very philosophers who have most rigorously examined it. As scholars like Anca Parvulescu, John Morreall, and Linda Mizejewski have variously shown, the stigma of humor, like that of sex, has been intricately interwoven with its designation as an irrational impulse and with gendered and racialized notions of embodiment. Moreover, there is a shared double standard regarding both laughter and sex: both have been imagined, paradoxically, as things that men have to cajole “respectable” (implicitly white, cisgendered, pretty, heterosexual) women to do and, at the same time, as things that transgressive women instinctively want to do, in excess. The dangers of both sex and humor have been encapsulated in the figure of a woman open-mouthed and out of control. In the early ’80s, the influential sexuality scholar Gayle Rubin observed that the most common symptom of our culture’s general fear of sex, or “sex negativity” as she called it, is the very impulse “to draw and maintain an imaginary line between good and bad sex.” That is, while various mainstream discourses of sex differ from one another in terms of the value systems they deploy and their level of overt misogyny, their views of sex are, ultimately, remarkably uniform: “Most of the discourses on sex, be they religious, psychiatric, popular, or political, delimit a very small portion of human sexual capacity as sanctifiable, safe, healthy, mature, legal, or politically

In recent years, I’ve often been surprised to hear irony or ambiguity denounced in feminist humor criticism, as though it would be possible, if people would just say what they really mean, to be assured of a perfectly direct transmission of ideas or a fully inclusive joke. For example, in her study of the dangers of rape jokes, Lara Cox reiterates the superiority theory view that the pleasure of irony depends on “the idea that there is someone out there who won’t ‘get’ the nonliteral nature of the utterance” — and these dupes are “the joke’s ‘butts’ or ‘targets.’” In his study of race humor, Simon Weaver distinguishes between polysemous jokes, which inadvertently reinforce racism, and clear jokes, whose antiracist message cannot be mistaken. I worry that such arguments seem to disavow the fundamental slipperiness of language. Contributing in their own way to North American sex positivity, French poststructuralist feminists such as Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous underscored that words have never been equipped for transparent representation. While many jokes do depend on linguistic play, comedians are not responsible for the essential arbitrariness of their medium. Words will always interact and impinge on one another; signification will always be subjectively, historically, and politically inflected, by both speakers and listeners, in myriad ways. Reminding ourselves of the basic wildness of language — and the range of meanings and identities that this wildness makes imaginable, especially in jokes — can temper our anxiety about the inevitability of misinterpretation.

Can we develop a more thoroughgoing and flexible view of the rhetorical and performative aspects of humor?

Of course, jokes can be hurtful, sometimes intentionally so. However, taking cues from sexpositive feminists, we might want to stop simply assuming that they are. Just as consensual sexual relations of domination and submission may look like abuse to those who don’t understand the rules, so might some apparently mean jokes. Think of insult comedy or a roast, where the target welcomes the jokes that really sting. But the larger and more important point is that, more than any other factor, our theories of humor will determine our perception of any joke. Keeping our minds open to the possibility that surprise or relief rather than aggression may be the primary affect or intention will better equip us to see the various, potentially contradictory, facets of any comic provocation. Mainstream feminist critics have specific reasons for rejecting jokes about

DANIELLE BOBKER form of sexual participation. Moreover, they saw that the patterns of giving, taking, and sharing power through sex are much more various and unpredictable than — and sometimes run counter to — the arrangements delimited by basic socioeconomic and patriarchal paradigms. A first step for developing a similarly nuanced take on the power relations entailed in humor could be examining and loosening up our often-unconscious obsession with the cruelty of laughter. In the philosophy of humor there are at least three ways of characterizing laughter, which can help to parse the differences between various jokes, as well as modes of delivery and reception. Today humor philosophers are most convinced by the idea, first fully elaborated in the 18th century, that laughter is a response to incongruity: something familiar suddenly looks strange, and the resulting sense of surprise pleases us. Another branch of humor theory draws on psychoanalytic notions of the unconscious. Relief theorists, most famously Freud, have emphasized the way that jokes, like dreams, trick us into considering ideas that we normally repress: laughter specifically manifests the giddiness of released inhibitions. These two modern theories of humor are largely compatible. In them, amusement does not necessarily degrade its objects but may imaginatively reframe or transform them, circulating power between tellers, laughers, and their objects in any number of ways.

52 53 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS