38 minute read

THE FALL OF THE CINEMATIC MUSE by Ryan Perez

MARTIN KERSELS, FLOTSAM (TABLES SKELETON), 2010, COLORED PENCIL ON PAPER, 30 X 22 INCHES ©MARTIN KERSELS /COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY

OBSESSIONS: GET IN BED

Advertisement

DANIELLE HENDERSON

My therapist would tell you that the longest relationship you’ll ever have is the one you have with yourself. She’s wrong. The longest relationship you’ll have is with your bed.

I have a nattering obsession with my bed. It took me three years to find the perfect comfort combination. This, for the record, is a separate pillow topper, electric mattress warmer, the best linen sheets you can afford at any given moment, a king-sized duvet on a queen-sized bed. When the time came to buy a new one, I put more effort into researching mattresses than I did my graduate thesis. I’m now so cozy it takes me three hours to get up every day, which my cat roundly protests by breakdancing on my face until I finally feed him. He always runs back and curls his little body right in the center of the soft comforter, though; even he knows it’s the best seat in the house.

My sex life is the biggest joke I’ve ever told, and my bed has been there through it all. Marriage, divorce, dating women for the first time, that unfortunate mustard incident — my bed was there to soak up the all the fun, the tears, and the Gulden’s.

People love to say that you should not work in bed. Those people are my immediate enemies. Anything I’ve ever written that’s worth a damn was done horizontally, fluffy pillows at my back, laptop propped awkwardly on my chest and typing like a goblin while the heat of the hard drive threatens to burn a hole in my breastplate.

As a child, I was forced out of my slumber every day by my grandmother. A slave to school schedules and cultural propriety, she flipped on the overhead light and bellowed: “Time to get up! Don’t make me come in here again.” Her methods were harsh, which only made me relish the time I spent in bed even more. I used to dream of scenarios that would allow me to stay in bed all day, but they all seemed to involve prolonged illness.

The four-person bed in the original Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is my first memory of obsessing over beds. The grandparents just lived there, all day? Of course, in the movie this was meant to be convey abject poverty but to my young mind, it seemed like an impossible dream. I was actually sad when Grandpa Joe hopped up and joined Charlie in his adventure. Which would you rather do, if given the choice? Staying in bed and complaining with your best friends all day, or whirling around an acid-fueled sugar-coated nightmare town? I would choose staying in bed every single time.

YET ANOTHER LOVE THAT DARE NOT SPEAK ITS NAME

JONATHAN AMES with illustrations by Maureen Selwood

Full disclosure: I was told to write something comedic for this comedy issue.

Full disclosure: I should say I was asked to write something comedic for this comedy issue.

Full disclosure: Surprising myself, I said “yes” immediately. I was in one of those moods where you think it’s good to say “yes” to things.

Full disclosure: But I’m a little out of practice writing prose and to just sort of snap your fingers and write something “funny” isn’t that easy. I’m not regretting saying yes, but yesterday I was. I thought, “Oh, shit, I’m going to have to tell them I couldn’t come up with anything.”

Full disclosure: What I thought I might write about — yesterday — is that sometimes I have feelings for my dog, Fezzik, that verge on the erotic.

But that’s not really accurate. It’s more romantic than erotic.

But one time — in a moment of great admiration and affection for his person and his cute little body — I did brush my hand against his tiny, fur-covered p***s, and I wondered if I would need to bring it up in my analysis.

And would I also have to tell my analyst that more than once when Fezzik has yawned in my face I have wanted, fleetingly, to put my tongue in his mouth?

Full disclosure: So that’s what I thought about writing yesterday, but I didn’t think there was enough there. Not enough story. I love my dog, and one time, and only one time did I touch his genitals. And that one time was almost accidental. Emphasis on almost.

Full disclosure: What happened was this: Fezzik and I had been separated for hours, which is hard on both of us. Often, when I am gone for long stretches, I wonder why I haven’t heard from him. I look at my phone expecting there to be a text. Then I catch myself: “You idiot, he can’t possibly text you!” And yet I’m hurt and bewildered that he hasn’t.

So on the night in question, I came home, eager to be reunited, and Fezzik raced about, stuffing toys in his mouth, which is what he does at his happiest. It’s like he can’t contain himself, his joy, his need, so he has to load up his mouth, which I understand quite well. My mother breast-fed me for only two months and I’m still upset about it.

Anyway, after Fezzik exhausted himself dashing about, he hopped onto our bed, I mean my bed, and he lay on his back, put his paws in the air, and exposed his belly for a soothing rub. This is usually phase two of his welcome home to me.

I looked into his eyes, which are quite beautiful, and I’m not the only one to think so. A Lyft driver, who was ferrying Fezzik and me from a friend’s house in Santa Monica, commented on their loveliness. He said, “It’s like they’re ringed with mascara.” I had never considered this, but it was an excellent and astute observation.

So I lowered my hand to rub Fezzik’s belly, but because I was staring moonily into his eyes, my hand went too low and lit upon his little furpouch, the tiny speed-bump that encases his p***s.

I knew immediately that a mistake had been made, but I let him my hand linger there one second too long, felt risqué and louche and outré, all things French, and then stroked his belly. But that one second makes all the difference in the world. It’s the membrane between heaven and hell, between sin and virtue.

Full disclosure: I should say I have thought of touching him again. But I think I want to touch it only to do something bad and taboo, and then be forced to tell my analyst about it. So it isn’t so much that I’m compelled to touch it again because I want to touch it again, but, rather, I want to get in trouble. I want to be punished. I’m looking to create a drama for myself. My punitive super-ego hasn’t had much to work with lately. I’m sort of old and well-behaved at the moment.

Full disclosure: But I’m not sure if my filter is operating properly, which is perhaps one of the reasons — of the myriad — I’m in analysis four times a week for over three years. You see, I had to go for the old-

fashioned cure to try to change myself before it was too late. But maybe because of a leaky filter, which still hasn’t been fixed, what I’ve touched on here — literally and otherwise — is most likely illegal, and I should have kept my mouth shut!

Yet I also suspect I am not alone with having inappropriate thoughts about my dog. I mean I’m not saying other people are having inappropriate thoughts about Fezzik, though I could see why they would, like the Lyft driver, but what I meant was that I’m sure there are others out there who have strong feelings for their dogs.

And let’s not forget that sometimes this all goes in the other direction. For example, when I was a young boy, maybe six years old, my uncle’s very large and very hairy English sheep dog, Oliver, in a moment of lust and insanity, pinned me violently to the ground — this was in Pennsylvania — and mounted me, missionary style.

I was wearing shorts, it was summer, and he rubbed his horrifying, slick pink thing — one of nature’s mistakes — between my bare legs, like a piston, bathed my face in hot dogbreath, and bit my shoulder, without breaking the skin.

He was a rough lover, but good about the biting, and I sensed intuitively, despite my youth, that something sexual was happening, and I was terrified and screamed for help. My uncle came running, grabbed Oliver by the scruff of his neck, cursed at him viciously, and threw him off me. After that, the memory goes blank, until about my sophomore year in college.

Full disclosure: But about Fezzik. I’ve had him for six months. He’s a rescue. Maybe two years old. He was abandoned, left chained to a fence. He seems to be a mix of beagle, Chihuahua, and basenji. He has floppy ears, a tan body and a white neck, and his firm, little tail is always up and curled, revealing a discreet and fastidious anus. He weighs about 20 pounds and his fur is soft and lush. He’s loving and kind, introspective and silly, soulful and good. Naturally, we sleep together every night.

I get into bed with a book, and he burrows under the blankets and goes down by my feet, though sometimes in the middle of the night, I find him curled against my lower back for warmth, and I feel lucky not to be alone in the world. In the morning, he emerges from beneath the blankets and kisses my face and cleans my eyes. Then I make coffee for us — well, for me — and we go to the backyard, and I read Pema Chödrön, whose books I love, and I think about things, like how the path is the goal, my ugliness is my beauty, and that pain is the great teacher.

Meanwhile, Fezzik sniffs the ground for raccoon urine, buries his bones in the dirt, and sometimes sits in my lap, like a sentinel, turning his head to the left and the right, smelling the breeze.

It’s a soft and delicious existence, and I’m a soft citizen in a troubled time, but in these moments with Fezzik, when I quiet myself, I sense the expansiveness of life beyond the confines of my pinched and noisy mind, and I am not without hope.

Full disclosure: Yesterday, when it seemed that I couldn’t write this piece about Fezzik, I was rooting around in some ancient files on my laptop, looking to find something I could repurpose, and I came across an essay I had written 12 years ago, but never published. In this essay, I had included a journal entry from 1993. I was struck by the entry as something that the LA Review of Books might like because it’s primarily about writers and literary figures, and so I’m going to add it here.

I know it’s a bit odd to pair it with my Fezzik love story, but what the hell? Why not experiment? It’s sort of like saying “yes,” which is how I got into this mess in the first place, a mess which is probably going to lead to my being arrested by the ASPCA or even the Audubon Society, though their concern is primarily for birds. But I imagine they would want to come to Fezzik’s aid if they get wind of this essay.

Full disclosure: Here’s some background to this diary entry: it was written one night while I worked the door at the old Fez (not short for Fezzik, sadly) night club on Lafayette Street in Manhattan. I was 28 and had published one novel, but had gone back to school, to Columbia, to get a degree so that I could teach.

Being a student, I was always low on money and had many little jobs. In this entry, I talk about “running film” at a boxing match in Madison Square Garden. This was before cameras were digital, and so I was employed by a news service to run the film, between rounds, from the ringside photographers to a make-shift dark room in the bowels of the Garden. The idea was for them to start developing the images right away, but I only had to run one time since it was a first-round knock-out.

I got that job because my girlfriend back then, referred to as H. below, was a photographer for Reuters. I remember being with her when the first attack on the World Trade Center happened, about two weeks after this entry was written. We had been out all night and then slept very late, past noon, in her dark, cave-like apartment. It was February and cold, very little sun, and in overheated New York apartments you could almost sleep through a whole winter. Then her boss called, waking us. They needed her to rush down to Wall Street — someone had attempted to blow up the Twin Towers.

Well, here’s the entry:

February 10, 1993

I was hung-over all day, but rallied in the afternoon. Philip Roth lectured at Columbia today. I asked him, “Why are we ashamed to be Jews and how can we get over it?” He didn’t answer, just laughed. But I was serious. He said that he was excited by three cities: Newark, Prague, and Jerusalem. He said that he was intimidated by people with conviction. Me too. I don’t have conviction. He said, “Be ruthless, serve the writing, not the life . . .”

Last weekend: Friday night I was the bartender and waiter at a private party in Turtle Bay for the former ambassador to England. Mayor Koch was there, gave me a penetrating look, like he wanted to make love to me. I heard someone talking about Koch at the party: “He’s a terrible man, dividing the city, I listen to him on the radio still going on about Dinkins abandoning the Jews.” Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. was there for some reason. He wanted a whiskey, “One ice cube, mild.” He still had a thin moustache, his face was jowly but he looked dignified. I could almost recognize in him the young man he once was; I kept comparing him to the black and white vision of him in my mind from “Gunga Din” . . .

When I brought him the drink, he said, “Thank you, you’re too kind,” with great dramatic emphasis, like I had saved his life, and then he said, “I’ll put you in my will.” I said, “I’ll give you my name at the end of the party.” He smiled at me, his eyes twinkled.

When I went up to Mayor Koch to see what he wanted to drink, he extended his hand, he thought I was somebody at the party, I was wearing my blue blazer, but like a good servant I didn’t extend my hand to meet his and said, “Would you like something to drink, Mr. Mayor?”

He didn’t want anything, and then this middle-aged reporter started talking to me, and he gave me the same look that Mayor Koch gave me, and he said that young gay men were not as frightened about AIDS, and then he added, “Sex is back in, you know,” and I said, “I never knew it completely went out.” I was quick with the oneliners that night. Kept sneaking drinks for myself.

Saturday night I ran film at Madison Square Garden for Reuters and the Washington Post at the heavyweight championship fight; it was great. Backstage there were dogs in cages for the dog show the next day, and in the arena there were movie stars, sports stars, gangsters. Fans chanted “bullshit” after the quick knockout. Riddick Bowe was amazing: his long beautiful jab tipped at the end with muscle-like curled bright red glove. Bell tolled ten times for Arthur Ashe.

Child star Macaulay Culkin came backstage to see the dogs in their cages. His hair coiffed, skin pale, very tiny, had private limo, looked at the dogs and smiled like a little boy. His father had a Hollywood ponytail. When they got in the car Macaulay sat up front and his parents in back, it was an odd reversal.

Michael Dokes, the loser, glowering out of the corners of his eyes, in body-length fur coat, leaned on his old handler and went into a limo after Macaulay.

Went to press conference and watched Bowe with the circus of TV reporters. Saw MC Hammer and Joe Frazier – not walking too well; old boxers all damaged, their brains and balance loosened in their heads.

Then Sunday I worked the door here at the Fez for the Neal Cassady memorial radio broadcast, a pathetic sort of tribute with old men trying to recreate lost youth and madness for stylish dead Nineties youth submissive in the audience. Snuck down a few times. Ginsberg was up on stage, trim, looking like a reformed congregation rabbi in his blue blazer and flowered tie and grey beard and wise kindly bald dome, reading his poetry about young boys’ hairless chests and buttocks; then Ginsberg’s old lover, drunken Peter Orlovsky showed up, fat, looking like an Archie Bunker crony, baseball hat, blazer, pocket bulging with pens. “I am a famous international poet,” he said to me, so that I wouldn’t ask him for the cover charge. His name wasn’t on the comp list. I said, “I know who you are. Don’t worry about the money. But for admission can you tell me about Neal Cassady?”

He was happy to talk, drunk, launched into a little monologue, “It was like the sun came into him and gave him energy. You don’t see that kind of energy any more, his arms, the biceps, the triceps, they were beautiful, strong, his belly was flat, and smiling, he was always smiling, always on, took the energy right from the sun . . . “

“What about Kerouac?”

“Too good for words. He lived to write. Not for fame and money, just to write, he died in his bathroom and wrote his last poem in his blood.”

“Him and Elvis in the bathroom. Is it true that Kerouac screwed Neal over?”

“No, they loved each other. It wasn’t a homosexual love. It was a love of souls. Man to man. You see, Jack loved Neal because Neal was a great cocksman and Jack was shy, a gentleman, he was like . . . like Victor Hugo and Neal was Rimbaud . . . and Jack gave Neal life, made him immortal.”

Well, that’s all to report. Look forward to being with H. tonight if she still wants to see me. I’ll bring a bottle of wine.

Full disclosure: So many little things I could mention regarding that entry. Like the time I met Allen Ginsberg in 1986, on Avenue A in the East Village, late at night, and he told me to go to the Naropa Institute to study writing, and so I did, driving some guy’s VW van from New York to Denver, and then taking a bus to Boulder, Colorado, only to discover that the Naropa Institute was really expensive and I couldn’t afford any of the classes. This was before the internet, when you did things like drive cross-country to a school because Allen Ginsberg told you to, not knowing that you couldn’t afford it.

And how years later, I would see Peter Orlovsky, sitting in doorways, in all sorts of weather, always near University Place, and he had completely lost his mind and was quasi-homeless, but somehow, he lived a long time after Ginsberg died.

And how at that same party where I served Mayor Koch and Douglas Fairbanks Jr., I also served Kurt Vonnegut, and I told him that he was the first writer I had ever loved, and he said it was kind of me to say that. But for some reason, I didn’t put that in the diary entry.

And how the people who threw the party took me under their wing and gave me a spare bedroom in their house to use as an office so that I could work on my second novel, since the room I rented, where I lived, was too small for a desk. And how I would look out the window from my “office” and I’d see Vonnegut, who lived across the street, sitting on his stoop smoking, since his wife wouldn’t let him smoke in the house, and how on that same street was this mysterious high-end brothel, which 20 years later sparked the idea for my most recent book, a thriller where a young girl is saved from such a place.

Well, I guess that’s about it. I’m running out of steam. Been writing for a few hours. And if you were here with me in my little house in Los Angeles, you would have heard me call just now for Fezzik, and you would have seen him come trotting into the room, where he is now sitting by my feet. A little yelp of some sort came out of him and he is looking up at me with his quizzical, beautiful eyes. It’s time to take him for a walk.

HOW I FINALLY LEARNED SELF LOVE IN A POST NUCLEAR WORLD

BROTI GUPTA

In this vapid world of Facebook, Instagram, and the pretty big nuclear explosion like an hour ago, it’s been hard for me to take the time to love myself.

Like so many women, my inability to care about myself started when I was a teenager and my self-image was as weak as the level of nuclear warfare we were in at the time. One of these started to grow, and not the one I’d hoped. Every time I looked in the mirror, I judged myself. Are my pants fitting weird? Are my braces the wrong color? Is the Fire and Fury™ Protection Oxygen Mask my parents gave me making my forehead look big?

Today, I dragged myself out of the rubble and to my mirror where I noticed small details on my face I hadn’t noticed before. My sharp, distinct jawline, my eyes that tell a thousand stories, my hair scorched from the explosion we never thought would happen. And I finally realized — there’s so much to love.

Other people saw this in me before I saw it in myself (before all of our retinas burned out of our eyeballs and none of us could see more than just “relative shapes”). In fact, during those teenage years, my friends and I would sit by what were then known as “trees” but now known as “used to be where trees were, before North Korea aimed right,” and just call each other beautiful and amazing, but ourselves ugly and unworthy.

Maybe if we could have treated ourselves like we treat our friends, we could have learned to be less critical of ourselves. And maybe through loving ourselves, we could inspire the country to love itself and stop instigating nuclear bombs over social media. A love of self leads to a love of others, which leads us to stop using names like “Ugly,” “Stupid,” or “Little Rocket Man,” which will inevitably lead to a violent third world war with weaponry like we’ve never seen before.

But just as important as how we see ourselves on the outside is how we treat our bodies — how we end up feeling on the inside. It’s fun to indulge in an ice cream cone or whatever’s left of the bag of flour in the freezer every now and then, but it’s also fun to test the radioactivity of the Farmers Market remains and get those natural nutrients flowing through our bodies. We have to get our bodies moving, so we can feel our blood circulate. Instead of just walking, we can jog…away from another nuclear target, which will help minimize radiation exposure.

So, that’s the kind of woman I want to be from now on. I want to be able to do things for myself, and take care of myself. I want to go to the Ground Zero Spa, or the Ground Zero Acupuncturist, or this one Dave & Buster’s that survived everything. And, while Kim Jongun keeps launching his ICBMs, I’ll be launching my own ICBM campaign: I Care ’Bout Myself.

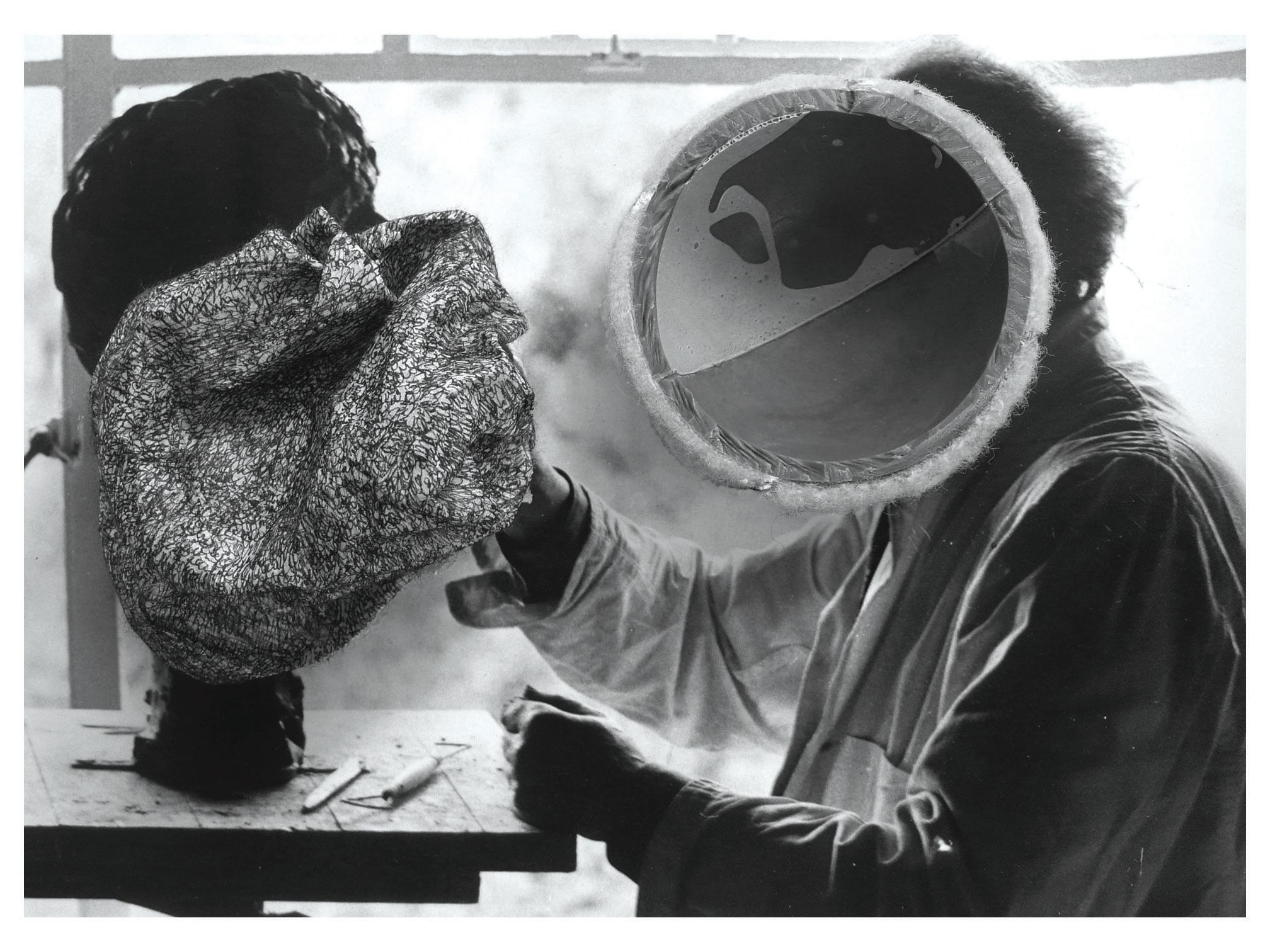

JOHN DIVOLA, 74V03, 1974, GELATIN SILVER PRINT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GALLERY LUISOTTI

ODE TO AN AGING POSTMODERNIST

MARC VINCENZ

You wanted taste. Long stretching lines that held a voice you could hear in your head, the timbre

with a resonance of wit or the sufficiency of time. Something like that clock chiming beneath the stairs,

or a soft, languid, wet voice that tickles the earbones. You wanted to reach in, to feel as the voice, to smell

the herbaceous green on the sill, the clandestine weight of passion or, better yet, the perfume of Paris in autumn— yet, yet, something held you back.

Your reason was a faithful dog whirring in circles around a single tree, snapping at imaginary birds. The line you sought, heavy from all that laundry of words, the sink

filling up with swirling punctuation. And what of the in-between, where there are no words, where there is only space and silence to tell the story.

THE LAST OF THE ZEN POETS

MARC VINCENZ

—for M.

Last night I was blinded by a sharp ray of light. Strange.

In my dream I was trying to catch a squall.

And when I awoke, feeling this urge to dance,

I followed the leaves shaken loose along the riverbank.

As the river pierced the valley with a booming rush,

I found the moon in a fast contented sleep.

It was a perfect moment to let my mind become still—

for when I reached the coast I wrapped myself oyster-tight in the ocean calm

and opened.

JOHN DIVOLA, 74V02, 1974, GELATIN SILVER PRINT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GALLERY LUISOTTI

TOWARD A HUMOR POSITIVE FEMINISM: LESSONS FROM THE SEX WARS

DANIELLE BOBKER

“Laughs exude from all our mouths.” — Hélène Cixous

“Comedy, you broke my heart.” — Lindy West

In a bit about sexual violence in his 2010 concert film Hilarious (recorded in 2009), the nowinfamous Louis C.K. says: “I’m not condoning rape, obviously — you should never rape anyone. Unless you have a reason, like if you want to fuck somebody and they won’t let you.” I was delighted when I first encountered this joke on Jezebel in July 2012 in a post called “How to Make a Rape Joke.” Lindy West was responding to the social media controversy surrounding American comedian Daniel Tosh, who had recently taunted a female heckler with gang rape. West’s insightful essay later led to a 2013 TV debate with comedian Jim Norton as well as her best-selling memoir, Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman, where she describes the fallout of becoming one of the United States’s best-known feminist comedy commentators, including her subsequent, painful decision to stop going to comedy shows.

In “How to Make a Rape Joke,” West wondered whether it is ever okay to approach sexual violence with humor. She wrote that she understood and respected those, like the woman who called out Tosh, for whom it wasn’t, categorically. The sexual assault of women poses a special problem for comedy, she reasoned, because it is an expression of structural discrimination against women. That is, unlike misfortunes such as cancer and dead babies known to befall people at random, if you’re a woman, not only do you face a one in three chance of becoming a target of sexual violence, but you will also likely be held at least partly responsible for it. To illustrate the inappropriateness of jokes about this kind of a situation, she drew a comic analogy between patriarchal society and a place where people are regularly mangled by defective threshing machines and then blamed for their own deaths: “If you care […] about humans not getting threshed to death, then wouldn’t you rather just stick with, I don’t know, your new material on barley chaff (hey, learn to drive, barley chaff!)?” Compassion about a culturally loaded form of suffering would seem, automatically and intuitively, to preclude humor about it. Yet West’s own humorous reframing demonstrated what she ultimately decided: that you could be funny about sexual violence if you “DO NOT MAKE RAPE VICTIMS THE BUTT OF THE JOKE.” In particular, Louis C.K.’s rape joke then earned West’s stamp of approval because, in her words:

[It] is making fun of rapists — specifically the absurd and horrific sense of entitlement that accompanies taking over someone else’s body like you’re hungry and it’s a delicious hoagie. The point is, only a fucking psychopath would think like that, and the simplicity of the joke lays that bare.

Though her recent New York Times piece “Why Men Aren’t Funny” makes it clear that West now regards her defense of Louis C.K. as a relic, her sharp distinction between acceptable and unacceptable jokes in “How to Make a Rape Joke” set the standard for mainstream feminist discussions of comedy for a good five years.

While I find West compelling, in my own efforts to navigate the contemporary feminist ethics of humor throughout this period, I’ve been resisting the impulse to draw limits. Instead, I’ve been looking back to the debates over sexuality that were central to North American feminism in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During the so-called sex wars, feminists agreed that sexuality had always been held in a patriarchal stranglehold but disagreed about what to do about it. The Women Against Pornography saw explicit sexual representations as the very basest mechanisms of female sexual oppression and so focused their energy on educating the public about their harms and prosecuting pornographers. By contrast, sex-positive feminists, as they came to be known, claimed that trying to shut down or cordon off unacceptable expressions of sexuality only exacerbated the problem. They argued that the history of criminalization and widespread fear of any sex but the reproductive, romantic, married kind had not only led to the marginalization of sex workers, lesbians, gay men, trans people, and many other so-called sexual deviants, but also cast sexuality as such into the shadows. Targeting pornography was therefore counterproductive. As Susie Bright, vocal defender of the sex-positivity movement and founder of the first women-run erotic magazine, put it:

porn [can be] sexist. So are all commercial media. [Singling out porn for criticism is] like tasting several glasses of salt water and insisting only one of them is salty. The difference with porn is that it is people fucking, and we live in a world that cannot tolerate that image in public.

Sex-positive feminists actively chose not to contribute to this climate of moral panic, focusing instead on unearthing the deeply embedded mainstream prejudices around sexual practices and fantasies. Instead of turning away, they faced sexuality head on, acknowledging debts to the small minority of people — sexologists, fetishists, queers, sex workers, erotic performers, and indeed pornographers — who had already begun exploring human sexuality in all its complexity, often with little socioeconomic support and at the risk of criminal charges. By many accounts, it was this unabashed approach to sex that led to the development and popularization of safe-sex protocols and consent education later in the 1980s.

There are of course, limits to the comparison of sex and humor, especially given that the impact of hetero-patriarchy on sex is much more immediately visible. Nevertheless, I would suggest that sexuality and humor are not merely analogous, but are in fact overlapping categories of feminist experience. Both are understood to be culturally coded but with powerful bases in the body. Like sex, laughter has historically been considered an unruly instinct, even by the very philosophers who have most rigorously examined it. As scholars like Anca Parvulescu, John Morreall, and Linda Mizejewski have variously shown, the stigma of humor, like that of sex, has been intricately interwoven with its designation as an irrational impulse and with gendered and racialized notions of embodiment. Moreover, there is a shared double standard regarding both laughter and sex: both have been imagined, paradoxically, as things that men have to cajole “respectable” (implicitly white, cisgendered, pretty, heterosexual) women to do and, at the same time, as things that transgressive women instinctively want to do, in excess. The dangers of both sex and humor have been encapsulated in the figure of a woman open-mouthed and out of control. In the early ’80s, the influential sexuality scholar Gayle Rubin observed that the most common symptom of our culture’s general fear of sex, or “sex negativity” as she called it, is the very impulse “to draw and maintain an imaginary line between good and bad sex.” That is, while various mainstream discourses of sex differ from one another in terms of the value systems they deploy and their level of overt misogyny, their views of sex are, ultimately, remarkably uniform: “Most of the discourses on sex, be they religious, psychiatric, popular, or political, delimit a very small portion of human sexual capacity as sanctifiable, safe, healthy, mature, legal, or politically correct” and, once the lines are drawn, “[o]nly sex acts on the good side […] are accorded moral complexity.” Wary of simply rerouting sexual shame, sex-positive feminists instead actively cultivated a nonjudgmental stance.

This might seem the worst possible moment to advocate for an equivalent form of humor positivity, let alone with reference to a joke about sexual violence by Louis C.K. In the wake of the public exposure of numerous celebrity serial sexual abusers such as Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, the viral #MeToo campaign has uncovered thousands of male harassers and abusers, and pointed to millions of others as yet unnamed. Since C.K. confirmed reports of his nonconsensual exhibitionism, some of the feminist anger and despair that was already rippling across popular and social media is being directed specifically at the industry that gave him his power. Many mainstream feminists, not least West herself, feel more prepared now than ever to throw the bathwater of comedy out along with the many baby-men who have been cavorting in it. Yet, as I see it, it is precisely in the context of our well-justified outrage that humor positivity is most needed. Humor is a vital, elusive, and continually evolving aspect of human experience. Like sex, it has repeatedly served oppressive ends, but it is no more essentially or necessarily discriminatory an impulse than sexuality is. It is undoubtedly important that we probe and resist the misogynist culture of mainstream comedy. At the same time I propose a change in the way we personally and collectively engage with the material this industry trades in — that is, the jokes themselves.

How might we ensure compatibility between the jokes we hear or make and the tools and concepts that shape our responses to them? How can we prevent our resistance to certain jokes from reproducing the (historically patriarchal) marginalization and stigmatization of the desire to laugh? If we get used to approaching jokes with trepidation, expecting offense, how might that wariness affect our political movements? In the current feminist conversation, these questions have begun to be raised in, for instance, Cynthia Willett, Julie Willett, and Yael D. Sherman’s “The Seriously Erotic Politics of Feminist Laughter,” Jack Halberstam’s “You Are Triggering Me! The Neo-Liberal Rhetoric of Harm, Danger and Trauma,” Lauren Berlant and Sianne Ngai’s “Comedy Has Issues,” and Berlant’s “The Predator and the Jokester.” My sense is that what we especially need now are some clear and concrete principles and practices for humor-positive feminism. Here are three lines of inquiry that I hope may help us to develop a richer set of responses to comedy going forward.

Can we develop a more complex and flexible view of humor’s power dynamics?

One of the major contributions of sex-positive feminism to our current understanding of sexuality was the recognition of seemingly counterintuitive forms of agency from below. Sexpositive feminists showed us the through line between the patriarchal suspicion of sexuality and certain feminist critiques of sexual exploitation. Though the fear of sex was originally and widely promulgated in medical, religious, and legal discourses, some of the alternative schemas of anti-porn feminists heightened the idea that most sex is inherently terrifying. For instance, Catharine MacKinnon’s view that “the social relation between the sexes is organized so that men may dominate and women must submit and this relation is sexual — in fact, is sex” — while it helpfully exposes sexual violence as a structural problem — also makes it impossible to distinguish consensual heterosexuality from rape. Sex-positive feminists turned to the less moralistic disciplinary frameworks of sexology, sociology, and anthropology. Inspired in part by the subversive theories of power of French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, they insisted that saying yes or no to sexual contact, including sexual domination, was a fundamental

form of sexual participation. Moreover, they saw that the patterns of giving, taking, and sharing power through sex are much more various and unpredictable than — and sometimes run counter to — the arrangements delimited by basic socioeconomic and patriarchal paradigms.

A first step for developing a similarly nuanced take on the power relations entailed in humor could be examining and loosening up our often-unconscious obsession with the cruelty of laughter. In the philosophy of humor there are at least three ways of characterizing laughter, which can help to parse the differences between various jokes, as well as modes of delivery and reception. Today humor philosophers are most convinced by the idea, first fully elaborated in the 18th century, that laughter is a response to incongruity: something familiar suddenly looks strange, and the resulting sense of surprise pleases us. Another branch of humor theory draws on psychoanalytic notions of the unconscious. Relief theorists, most famously Freud, have emphasized the way that jokes, like dreams, trick us into considering ideas that we normally repress: laughter specifically manifests the giddiness of released inhibitions. These two modern theories of humor are largely compatible. In them, amusement does not necessarily degrade its objects but may imaginatively reframe or transform them, circulating power between tellers, laughers, and their objects in any number of ways.

The oldest and still most popular notion of humor, however, is one that presupposes and depends on hierarchical and unidirectional power relations. Superiority theory perceives laughter as the expression of unexpected pleasure at discovering our own excellence relative to the things we laugh at. In Thomas Hobbes’s famous formulation, “Laughter is nothing else but sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others.” Superiority theory initially emerged alongside and is consistent with explicitly elitist political ideologies. It may be the only theory of humor children instinctively grasp: even at an early age, the phrase “That’s not funny!” is understood to mean not what it literally implies — “What you’ve said is not amusing to me and could never amuse anyone” — but rather “That hurts my feelings.” For kids, joking about the wrong thing is an ethical violation; it simply moots the possibility of laughing. These days, distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable jokes seem to put a modern, grown-up face on superiority theory. But jokes labeled as “offensive” or “inappropriate” are determined to be “not funny” in more or less the same way that kids mean it. The tropes that oppose “punching up” to “punching down,” coined in the early 1990s by the feminist satirist Molly Ivins, have been crucial in the popularization and liberalization of superiority theory. Those phrases also put a deceptively simple spatial spin on the relative socioeconomic power of laughers and objects. Reinforcing a David and Goliath moral code, the tropes imply that jokes are crucially aggressive in form, but that in some cases violence is justified. It’s okay — heroic even — to take on a bigger meaner guy, but undoubtedly a bad thing to pick on someone littler and weaker than you.

Of course, jokes can be hurtful, sometimes intentionally so. However, taking cues from sexpositive feminists, we might want to stop simply assuming that they are. Just as consensual sexual relations of domination and submission may look like abuse to those who don’t understand the rules, so might some apparently mean jokes. Think of insult comedy or a roast, where the target welcomes the jokes that really sting. But the larger and more important point is that, more than any other factor, our theories of humor will determine our perception of any joke. Keeping our minds open to the possibility that surprise or relief rather than aggression may be the primary affect or intention will better equip us to see the various, potentially contradictory, facets of any comic provocation. Mainstream feminist critics have specific reasons for rejecting jokes about sexual violence: for some survivors suffering from post-traumatic stress, the power dynamics of humor and of assault can sometimes feel so painfully intertwined that certain jokes are experienced as violations akin to the initial trauma. Yet it is precisely because the very perception of aggression can recharge past suffering that it seems important to remember humor’s other impulses. Recently, artists like Emma Cooper, Heather Jordan Ross, Adrienne Truscott, and Vanessa Place have been turning to humor expressly in an effort to destigmatize the experiences of sexual assault survivors and change the tone of our conversation. How might a more general focus on humor as incongruity or relief also help to reduce the frequency or intensity of fightor-flight responses and open up new aesthetic, therapeutic, and political prospects?

Can we develop a more thoroughgoing and flexible view of the rhetorical and performative aspects of humor?

In recent years, I’ve often been surprised to hear irony or ambiguity denounced in feminist humor criticism, as though it would be possible, if people would just say what they really mean, to be assured of a perfectly direct transmission of ideas or a fully inclusive joke. For example, in her study of the dangers of rape jokes, Lara Cox reiterates the superiority theory view that the pleasure of irony depends on “the idea that there is someone out there who won’t ‘get’ the nonliteral nature of the utterance” — and these dupes are “the joke’s ‘butts’ or ‘targets.’” In his study of race humor, Simon Weaver distinguishes between polysemous jokes, which inadvertently reinforce racism, and clear jokes, whose antiracist message cannot be mistaken. I worry that such arguments seem to disavow the fundamental slipperiness of language. Contributing in their own way to North American sex positivity, French poststructuralist feminists such as Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous underscored that words have never been equipped for transparent representation. While many jokes do depend on linguistic play, comedians are not responsible for the essential arbitrariness of their medium. Words will always interact and impinge on one another; signification will always be subjectively, historically, and politically inflected, by both speakers and listeners, in myriad ways. Reminding ourselves of the basic wildness of language — and the range of meanings and identities that this wildness makes imaginable, especially in jokes — can temper our anxiety about the inevitability of misinterpretation.

At the same time, let’s attend more carefully to the theatricality of humor, including the jokes and quips that bubble up spontaneously as part of ordinary conversation. In particular, stand-up comedians are in character even when they speak as themselves, and many comedians regularly adopt multiple personas, some of whom channel views that they find especially awful or absurd. Very often these views are already in the air, and the comedian, by giving voice to popular perceptions, hopes to draw fresh attention to them. Moreover, comedians tend not to put on and take off these various personas like so many hats, but rather to alternate and layer them, turning some up and others down, as if each one was a different translucent projection on a dimmer switch. These uneven amplifications of characterization actually generate the dialogic structure of comic performance, as stand-up scholar Ian Brodie explains: “The audience is expected to try to determine what is true [that is, closest to what the comedian generally thinks] and what is play. The comedian[’s] […] aim is […] to deliver whatever will pay off with laughter.” Staying conscious of these shifts will help us to recognize that the most challenging moments — those moments when we don’t know quite where to locate a comedian’s values and commitments — are not incidental but central to the interpersonal dynamics of stand-up comedy.