16 minute read

WELCOME TO MY STUNNING AIRBNB! by Mitra Jouhari

“Four miles is short.” In Brooklyn, Ruth walks a mile, which is 20 blocks, in 15 minutes. “It’ll be fine.”

Ruth continues down the trail. She feels light and easy in the sand, likes the feeling of being more hardcore than Casey for at least a minute. Maybe she can make up for her silence last night.

Advertisement

For the first half-mile they cross a broad, sandy valley. Rocky shores rise on either side, peppered by yellow flowers and palm fans with muscular leaves surging directly out of the ground. There’s a distant hill with so much scrub and cactus that it looks like a pile of washedout toys. Lizards scatter wherever they walk and finally they see the king: an overgrown, tarcolored toy with a rusty belly. He smiles, his arrow-shaped head rising.

As they traipse along, the sun floats to the top of the sky. Even with a hat and sunglasses, nylon shorts and a tank top, Ruth is starting to feel the heat. “Can I have more water?”

Casey passes her a warning look with the re-appropriated coke bottle. Her CamelBak and Klean Kanteen are both already used up.

“How many miles have we gone?”

“One.”

Ruth can’t visualize eight times the hike they’ve just completed. They make their way over a hill. There are skinny red bushes with hummingbirds sucking them. There’s a family of mule deer with comically shocked expressions.

“I love the off-season,” says Casey. “No one’s afraid out here.” They pass an antique mine, a pile of wood planks so fresh it could have been dumped yesterday. They see cottontails and a jackrabbit. Ruth pauses to rest every half hour, even though she’s not carrying anything. There’s no shade and she has to squat in low shadows. Sometimes shade is painted on the ground but isn’t there, really.

They walk for what seems like hours, though they don’t have a way to track the time. If Ruth goes more than a few minutes without taking a slug of water she’s dizzy and disheartened, can’t keep her path straight. But whenever she asks for more she tries Casey’s patience.

“Just a little farther,” says Casey. “You can do it.”

Ruth pees alarmingly often. At first she ducks behind boulders and cactuses in case they run into another group. But eventually she starts going right on the trail, barely bothering to squat, leaving puddles steaming behind them.

“If we draw this out,” Casey says, “we’ll run out of water.”

“I thought you brought enough,” says Ruth.

Casey sets her jaw. “I did. For a reasonable pace.”

“Good thing you have all those rocks. Maybe we can squeeze some water out of those.” Ruth is used to talking like this at literary parties in New York, but not to Casey. With Casey, she tones it down.

Casey just tightens the straps on her pack. Ruth doesn’t know why Casey always has to be so dour. She can’t even admit she’s offended, that’s how stoic she is. There’s something about her that’s so self-satisfied, with all her willful rugged-ness. The way she’s tramping ahead, lifting her feet high on the air, her shoulders clenched. Ruth can feel the words bubbling out before she’s even formed them in her mind. “I probably should have held out.”

Casey stops short and Ruth almost shaves her heel with the tip of her hiking boot. “Held out for what?”

She means for Natalia. There’s a picture online that she looks at occasionally, even now, of Natalia and Lezz B Friends at a table in a dark restaurant. Probably it’s no place special — Natalia never had cash — but the winking colors in the background make it seem more magical than any restaurant Ruth’s ever been to. Natalia wears a high-necked blouse, red with gold embroidery. Lezz B Friends has crashed in her lap, mid-laugh, like a goofy little boy. But it’s Natalia’s hand in Lezz B Friends’s hair that gets Ruth. Those slim fingers just barely resting, so that Lezz B Friends might never have known, were it not for the picture, that she’d been touched.

“You know what I mean,” Ruth says. Once she starts she can’t help it. “Like a girl girl.”

Ruth watches Casey trying to separate her words into boast, threat, passive aggression. She shakes her curls like a horse, marches on.

They scale a rocky outcrop and move across an area with the mystical name of Fried Liver Wash. Then they come upon a ridge that’s part of a crater. Across the valley, on the matching ridge, is a palm stand. That must be the oasis, but it looks like a median strip in LA.

They work their way along the long ridge of crater. When they finally arrive, the trek makes sense. Lost Palms Oasis is a whole different habitat, sandy and full of shade. Slabs of rock lie under palms that are stories tall, leathery and fire-scarred. Ruth cools instantly.

They set up lunch on a rock slab. Casey lays out the food, and the liter and a half of water they have left. Ruth eats her sandwich, the bar, and several handfuls of nuts. Casey doesn’t talk. She only wants half her sandwich and none of her bar, so Ruth eats that, too. Casey allows small sips of the remaining water.

After eating, Casey lies in the sand. Once her eyes are closed, Ruth can’t stop herself from reaching for the last bottle. She tells herself it’s okay; she’ll just have a little. But once the neck’s in her mouth she can’t help swallowing in great heaving gulps, dragging the liquid into her throat.

She feels much better. She lies down, allowing her face to stick in the sun.

When they wake, it’s time to go. The minute they cross out of the shade, Ruth’s sweating again, burns prickling around the borders of her sunscreen. Somehow it’s even hotter. Within minutes she’s asking for water, weak on her feet. Casey takes the bottle from the bag, holds it up to the sun.

“Jesus Christ,” she says.

“There’s some left,” says Ruth. A patty of water stirs at the bottom, mostly spit.

“Ruth. Do you realize this is actually a dangerous situation?”

“Fine. I won’t have any, then.”

Casey storms ahead. Ruth’s throat feels like a length of dry rubber pipe. “Wait. Casey. Why don’t we cut across the valley?”

The distance across the crater is far shorter than the perimeter. She doesn’t know why she didn’t think of that before.

“It’s too steep,” Casey says. “And wild.”

“It’s just a bunch of kindling. It’s not like we’re in the forest.” She imagines a sweaty bear popping out of nowhere, lazily chewing the air.

Ruth takes the edge of Casey’s waistband, tugs her close. Casey’s poof of curls only hits her chin.

“Okay. Fine.” Casey bows away. “But I would never do this if we weren’t low on water.”

They walk straight down the ridge. It’s only 15 feet to the valley, but the ledge is sheer. Ruth’s feet move faster than her body — too fast to foresee stones and dips in the dirt. They reach the bottom in seconds. In the basin of the wash, the vegetation is denser than it looked. Prickles lodge in Ruth’s ankles and she removes the thicker ones as they go. The distraction is good. Ruth forgets she’s thirsty, tired, burned.

Halfway through the crossing, the valley explodes with an atonal blast of sound. Ruth thinks it’s a cougar coming down from the hills, tongue vibrating in its teeth. Or maybe that bear is here, heartier than she pictured.

There’s a gunshot and a dead snake leaks on the desert floor. She follows the carcass up the barrel of the gun, which Casey is still aiming straight at it.

Then, though Ruth can’t be sure if she’s imagining it or not, the barrel levels upward, higher by the millimeter, until the holes in the tubes face Ruth as perfect circles, Casey’s pupil centered in the sight.

The snake snaps its rattle once more. Casey drops the weapon to her hip.

The walk back to the tent is easy. Ruth can’t believe they ever worried about water or the heat with everything else out there. She tries not to think about how she insisted on the overlong hike. How she drank all the water and led them through a ditch full of poisonous snakes. She was an idiot to be worried about Casey out there with the fireproof pouch. Casey didn’t even drop the extra rocks she was carrying, and she only got about a quarter of the water. Ruth is the incompetent one. She can’t see herself facing the dangers ahead. The broken-down Bronco, the thousands of miles of highway, more camping, her shaky relationship. If she were a better journalist, she’d go for the story, whip up some emotionally laden and geographically diverse stinger. She’s a chicken, probably, but she can’t face it.

At the campground Ruth touches Casey’s arm, but Casey pushes past and disassembles the tent. Ruth covers the hole in her arm from the cactus prick, which is deeper than she would’ve thought possible. She tries not to watch Casey’s muscular back, rolling the skin of the rain fly.

They leave the park by the southern entrance and return to LA via faster, uglier roads. Ruth is on a standby flight a few hours later, on her way to Brooklyn via Tucson, Cincinnati, and Newark, the best she could do.

In the airport, Ruth hugs Casey. They say they’ll give it a chance when they’re back in New York, on even ground, but they won’t. Ruth will go back to typing at cafes, trying not to masturbate, actually alone this time instead of pretend alone. She might have to face herself, then, without protection.

DIABOLIQUE

MARY-ALICE DANIEL

Aftershocks of The Great Mexico City Earthquake rocked me asleep in utero:

As a statuette of Mary nodded YES, seizing against the wall before falling, my mother predicted I would bring fortune. (80% of divination starts with shit falling to the ground.)

After a childhood watching Skeletor, not really understanding the Will to Power:

I miracled into this city, breezing past Death Valley, Devil’s Slide, Mount Diablo—figuring with eyelashes harvested from unanswered letters. (Every gift unrepaid harbors a curse within itself.)

The letters I’d sent to my favorite actress—curiously, opened and then returned:

…I’m sorry for predicting your exit—to prophesize death is to wish for it: the up-lighting and the whimper. Only because I was tired of watching you escape fate as if you alone were born under a lucky star...

Personally, I suppose I can quarrel with all applicable gods—

(I hold death in my pouch: I can not die.)

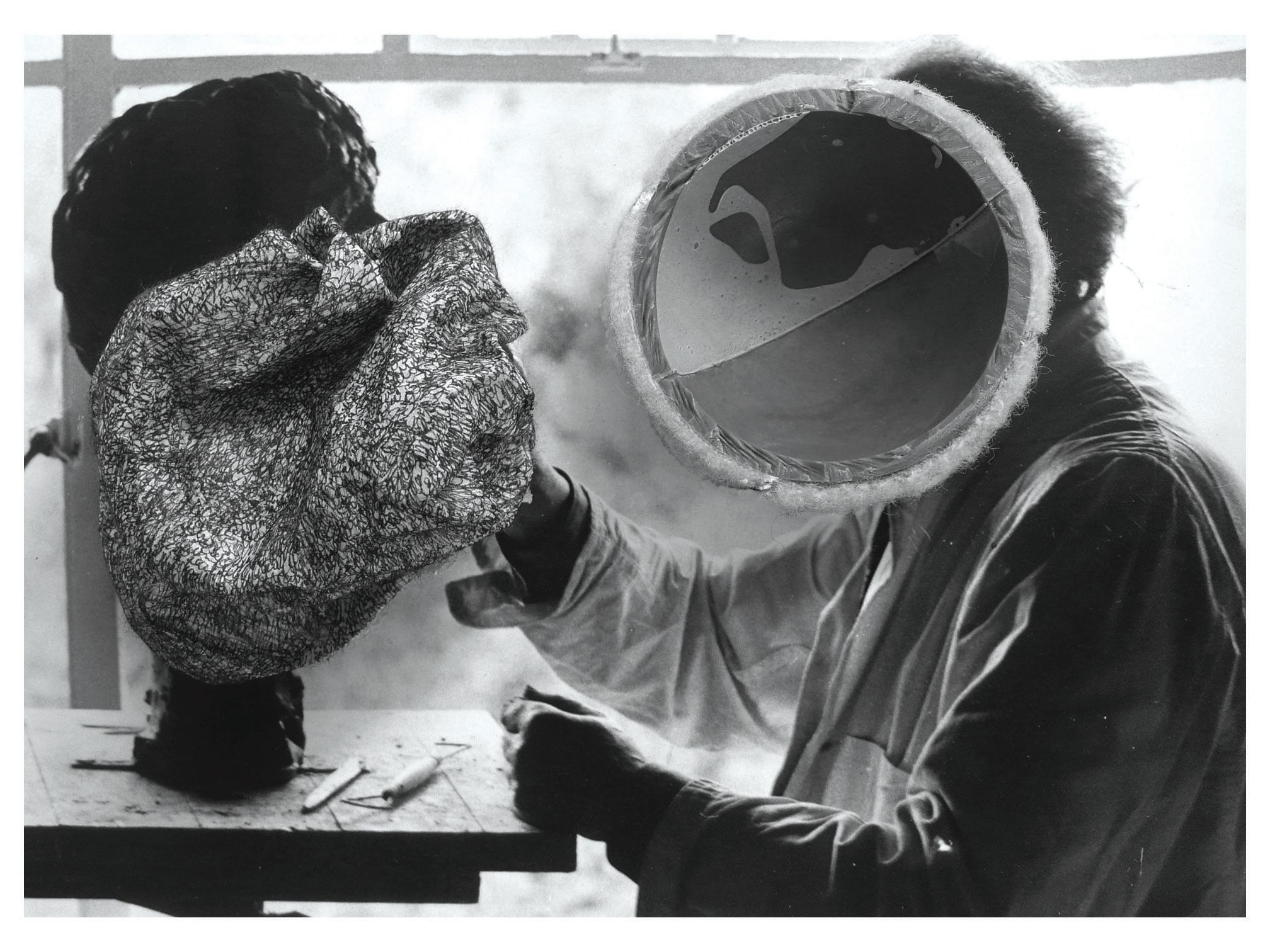

ALI PROSCH, HUMPING CHAIR, 2007, GRAPHITE ON PAPER, 6 X 9 INCHES

ADIOSLA.COM

MARY-ALICE DANIEL

Please publicize how I joked with the dead through dance. How I wrote obsessively about bodies as if they are objects of death study.

Memorialize me using cinemagraphs: otherwise-still photos in which a minor, repeated movement occurs:

(tiny movement) (endless loop) (Tantalusian)

In a single frame: (me playing with a rose in my teeth) (welcoming you into the machine of light)

Meaningful graffiti in the background: <3 sky flowers up in heaven <3 DEATH WILL BE YOUR SANTA CLAUS Suffer the frustration of photographing something amazing knowing thousands of similar photos already exist

Wherever I die, name that place after me— something loosely translating to:

“death trundling along in a ramshackle purple line, out to Fukushima-tainted waters”

AMANDA ROSS HO, BLACK RAGS (I HATE FRIDAYS), 2013, DYED JERSEY AND RIB, THREAD, 83 X 44 INCHES © AMANDA ROSS-HO / COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY.

OBSESSIONS: A GOOD FEEL

AMY ANIOBI

Cookies. You’ve been with me since I could chew. Happiness is a warm nest of chocolate chips melting into slick gold on the bed of my tongue, relaxing into a bitter river of darkness that burns its sweet path around every taste bud. Because yes, I ate you hot, right out the oven. A sliver of salt atop a pillow of dough, puckering and crunching for my teeth, for my joy. You were baked, for me, by me. Take a seat on my lips, because I need you.

Social media. From airports to bathrooms to dark clubs and awkward parties, to the evening hours right before I drift toward Sleeptown, you massage my brain, you keep me relevant, you keep me warm. The light of the love from you, saying, “I like you because you liked me,” is the simplest form of self-adulation, and sweet Insta, am I ready to be adored. I refresh you as I fall asleep, I wake you up when I wake up. In fact — what have I missed, you’ve been up all night? Aww baby, you’re watching over me? We’ve reached hashtag goals, together. I feel sad with you yet unsafe without you and fuuuck, how I missed you when I was in Cuba.

Fear. Oh, is that you? Of course it is ha. Always with me, always within me, filling me up like a blooming rose or a good dick — lol, my stomach is in knots because you. What if every moment in life becomes triggering? I sense you kissing my neck, curling over my mind, when I walk home alone on a dark street, or when I sleep in my warm bed, in my locked apartment, in my once-safe neighborhood that now has a “break-in problem” — a woman was raped two doors down — I need a new lock on my door, but when do I get the lock, and what kind of lock and ugghhh, there you are, you’re back. Like sex with a stranger, I know you. The quiet anxiety, the threat of today’s America keeping my spine arched and tense. L.A. is a city, America is a melting pot, and I’m scared no one wants me here, melting. I’m also scared I mentioned “good dick” — like, what if my parents read this? What if their new priest reads this? Oh god, what if you’re always here, feeding me, crushing me? What if you never get off me?

THE MAGIC — FLOATING — MOUNTAIN: NOTES ON AN ALASKAN CRUISE

KARAN MAHAJAN

The Alaskan cruise from Vancouver to Skagway and back covers 3,000 kilometers. To undertake this brave journey, my family traversed some 20,000 kilometers — my parents coming from Delhi, my brother from San Francisco, my girlfriend and I from Austin.

We, as a family, are perfect candidates for a cruise. Far-flung, restless, bullying, strongwilled, we can rarely make decisions without devolving into arguments and shouting. Taking a weeklong cruise was a way of neutralizing our tempers by making one big decision upfront and letting the cruise ship, with its copious overfull buffets and set itinerary, do the rest.

We arrived in Vancouver in shifts, on a gloriously cloudy Saturday afternoon — glorious, because the clouds in Vancouver play the same role they do over the Dal Lake in Srinagar, adding a dash of white boiling unreality to an already-perfect scene, giving the blue deep crystal waters of the mountain-ringed harbor something to reflect. We were stunned by Vancouver’s effortless San Francisco–like prettiness. Swatches of sunlight revealed picturesque houses on the hillsides, and the harbor was animated with seagulls and lifting seaplanes, which, from a distance, with their silent smooth takeoffs, looked like seagulls themselves. We were almost disappointed to give up on the city and board the ship, the Zuiderdam, at noon.

The Zuiderdam, a stately black and white vessel, holds 1,900 people. It is owned by the Holland America Line, which once transported hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the Netherlands to the New World. Like the other cruise ships, we could see the Zuiderdam from the window of our hotel, one of a cluster of floating buildings pressing up against downtown with its glassy Hong Kong–like emerald skyscrapers (Vancouver, for a Western city, has a distinctively South East Asian city feel — this may have something to do with the city’s huge Asian population which, in turn, has attracted a lot of investment from China and Taiwan). Boarding a cruise ship is a horrific process. You are packed into a warehouse that looks like a cleaner cousin of what one imagines Ellis Island was like and slowly propelled toward the US customs booth, where, if you have our luck, you will run into a frat-boy customs agent who cracks jokes as he stamps your passport.

America! It begins with wisecracks.

The ship immediately impressed us with its gaudiness: gold railings, red carpeting, elevators with glass doors imprinted with purple flowers — what the ship’s brochures called a “Venetian theme.” “It looks like a floating casino,” my girlfriend Francesca said. The premise of a cruise is that it will cost less than booking a hotel and paying for meals and that, in a sense, planning will be taken care of. “But they charge a lot for booze,” friends warned us. “Try smuggling some in if you can.”

Our first surprise on the cruise was how cheap everything was — cocktails for $6.95 (with a second free for $1 at happy hour) and $10 per head to eat a three-course Italian meal at the Canaletto, one of four restaurants on the ship.

Our next surprise was how cheap everything looked, despite the initial impression. A cruise ship advertises luxury, but it does not appear luxurious. There is something scruffy and used-looking about it. Francesca’s first impression was of a casino; mine, in the dining hall, with its shuffling old people, the obsessive instructions about sanitizing one’s hands, the food sequestered behind buffet screens, was of a hospital cafeteria. As for the general decor, it reminded me of what you may find beneath a tent at a Punjabi wedding. There was a flimsiness to the fixtures, a dank depression of reds, golds, and maroons.

Our barely functional room was done up in dull browns. But this didn’t matter because our balcony gave us a view along the very front of the ship. The swift gliding movement of the ship — which only entered truly choppy water on two or three occasions — was relaxing. Vancouver and British Columbia, with its pine-covered hills, soon gave way to open sea.

On our first full day on the ship — Alaska still a distant dream of whales and eagles — my father and I met for breakfast in the main restaurant, one of the more formal dining options. We waited an hour for our omelets to show up, and then, giving up, took an elevator up to the dining hall, where you can drink all the coffee you want and dictate your omelet from behind a buffet counter. An Indonesian staffer dipped a spoon into the largest pot of yellow egg ooze I have ever seen. In keeping with the colonial past of cruising, the staff is all “ethnic.”

The rest of the day — as it was to be on the days to come — was a haze of eating and drinking. We tucked away a big lunch; we sipped cocktails; we regrouped for dinner, attired in formalwear, as per the fussy rules of the ship; we loaded our plates with second helpings of cake. We were happy and satisfied. But then, as the days piled on, I began to feel, amid the rich plates of trout and the groups of cackling septuagenarian travelers from Australia, that I was on The Magic Mountain — narcotized by food as I drifted toward old age and death.

In Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel about … um … death, a young man goes up to a sanatorium in Davos for two weeks to visit his cousin, who is recovering from tuberculosis, and ends