45 minute read

TOWARDS A HUMOR POSITIVE FEMINISM: LESSONS FROM THE SEX WARS by Danielle Bobker

for learning, yet rang with the overtones of folklore, mythology, and hard-earned insights into right living.

That’s why I loved Dick Gregory’s uncensored voice. He wasn’t scared. Sounded black. Wielded humor as weapon, as flashlight. He was political. Entrepreneurial. He would just as soon scold you as shake your hand. Steadfast. Risky. He was also exasperating. Even as a second-year journalism student, learning the value of credible sources in my classes, earning bylines as staff reporter on our campus newspaper, The Hilltop, I wanted Gregory to offer road maps, books to research, and other scaffolding to help us grapple with his incendiary testimony.

Advertisement

I’m not sentimental about his voice, either. I do not consider Dick Gregory my mentor, nor any kind of father figure. I don’t consider myself an uncritical choir member. I groaned listening to him in one interview on YouTube, responding to the Cosby sexual assault vortex. “I don’t know what happened; that’s a police matter,” Gregory said; he then pivoted, asserting that “they” didn’t want Cosby to buy NBC. I can sure understand how difficult it must have been for Gregory to publicly criticize Cosby, who was his peer in many ways. But I’m a father engaged in an active “call and response” dialogue with my own daughter, who was abused as an adolescent by her black step-father. I have no patience for worries about protocol, when it comes to a dude on record as drugging women’s drinks as part of his foreplay. Then again, frankly, even as a teenager, I was temperamentally a loner who gravitated more to a good idea than an actual role model.

Ultimately, even in disagreement, I was imprinted by Gregory’s consistent bravery. He engaged fully in the life of his society, from the 1950s until his death. He walked the front lines during the Civil Rights era. He ran as a long-shot presidential candidate. He traveled to Iran as a citizen-ambassador. He called us out and put his body on the line in fasts and personal protest walk-a-thons. Gregory spoke up and spoke out. A contrarian, he never sounded generic; he delighted in going against the grain, and flexed the punch line as a direct route to what he considered the bottom line.

Dick Gregory emboldened me to trust myself, my imagination, my sense of the needs of my community, my cultural voice(s) — irregardless of the protocol of the moment. I’m laughing now, because the first protocol I had to transcend was my mother’s. Ooooohhh oooooohhhh! My mother was death on words like irregardless and conversating and she’d always assert that only folks without vocabulary used profanity. (Not even mom’s strictures could dampen my evolving aha that the richest communications skill was actually virtuosity — a vital ability to synthesize vocabulary, ideas, and tradition into a distinctive solo voice.)

These days my Moms must turn over in her grave, when I go off on Sir Trump D’Voidoffunk, or the vile hypocrisy of his pitch to those folk who’d still rather be white than American in their defense of clichéd, lame, corny PR-speak about greatness, patriotism, the flag, or the USA as home of the brave. If only she had sat beside me at Cramton Auditorium that evening when Gregory made me take off my sunglasses. She’d give me dap after my rants.

I’m with my two older brothers at Howard’s homecoming in October 2017. Ahh … Cramton Auditorium. I get chills. I actually only met Dick Gregory once, when I interviewed him in 1980 upon his return from Iran. By then I was a reporter at the Wilmington News Journal and we spoke at a hotel outside Delaware’s largest city. No entourage. No bodyguards. He traveled with one dude, Rock Newman, with whom I’d played baseball at Howard, and who’d go on to manage Riddick Bowe to the heavyweight boxing championship. A call to Rock led to my short interview (not to mention some super tasty Iranian pistachios), and I wrote a nondescript article that ran in August 1980. No big bang in this experience, but I was satisfied that I could get access to Gregory and do my job without any whiff of hero worship.

Pausing to take a photo of Cramton’s facade, 43 years melt away. Dick Gregory strides across a stage. He crystalizes the true DNA of my “pursuit of happiness” — my journey into and beyond the United States’s hypocritical contradictions and racial double-standards. Gregory channeled Benjamin Banneker chastising Thomas Jefferson in a 1791 letter for “detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression [which] you professedly detested in others.” Gregory anticipated Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 21stcentury schooling of Trump’s chief “grown-up” John Kelly, who got a Twitter history lesson after he misrepresented the national “compromises” regarding slavery and the Civil War.

From 1974 until this moment, Dick Gregory frees me to step with history as my homeboy and connect with epic reasons for living. Only time will tell if I am destined to speak across the years to posterity.

Irregardless, I lift my voice and sing. I spiral along the genealogy bequeathed by the voices of black men of integrity. Men like Dick Gregory. Yeah, men like Dick Gregory.

DREAM HOUSE

DEMI ADEJUYIGBE

Reader, today I found the house of my dreams.

My husband Roger and I were driving around after Waze took us down the wrong road, and there it was — a large, black, two-story Victorian house, all alone on a large plot of land with nothing around but twisting sinewy trees and a FOR SALE sign, scrawled on a piece of wood in some sort of dripping red marker. A real fixer upper, just like I’d always wanted. Roger was nervous to park because Waze didn’t recognize our location and our phones immediately lost service upon arriving — he’s such a worrywart sometimes!

As we walked to the front door we noticed a gaggle of schoolchildren watching us, playing on swings and singing nursery rhymes very, very slowly. How perfect! A community of kids for our own incoming baby boy! Roger let his paranoia get to him, as always. He wondered out loud where the kids came from if there were no other houses around. Reader, I love this man, but sometimes he acts like he’s never heard of a bus before!

I’ve never wanted to live somewhere surrounded by nature, but as I walked up and saw a murder of crows gawking at us from a dying tree in the front yard, I knew I’d found my paradise. I’ve always loved birds, and I instantly felt a kinship with these crows. They truly spoke to me — at first in a figurative sense, but Roger swears that he heard one whisper “Leave this land or perish” in Latin. Great joke, Roger — you don’t even know Latin.

The house looked old, but looks are deceiving. In fact, all of the doors had been rigged with sensors to open and shut whenever we came near! The front door swung open just as I was going to knock on it, and slammed shut as soon as Roger followed me inside. (While complaining and insisting that we leave, I might add. He never lets me do anything!)

Reader, it was just as gorgeous inside, and maybe even bigger than I thought! There was a dining room with crystal chandeliers and a series of large ornate paintings of people who must have been the previous owners. There was even a player piano in the living room that cycled between two notes over and over with increasing speed! I presume it was battery operated, because it continued playing even afer Roger tripped over the cord. What a klutz! He even tried to play it off by claiming he was spooked by the paintings blinking at him.

I found the nice groundskeeper just outside of a door with 20 locks on it. He was a tiny, tiredlooking old man who went by the name of Vlad. He said his “true name” is unpronounceable by the human tongue. I didn’t even try, I’m SO bad with foreign names. He led me on a short tour of the upstairs, taking me through the master bedroom and the nursery, each of which was decorated by a lovely assortment of Victorian dolls. How quaint! I asked if the dolls belonged to the previous owner, to which he said “the previous owners belong to the dolls.” I didn’t ask him to clarify — no need to embarrass the man for misspeaking in his second language!

I was in love with the place, and told Vlad as much. He said the only requirements he had for the next owners was that they not be priests or allow any priests onto the grounds. Not a problem for me, the only priest I know is Roger’s father, and he passed away 10 years ago (this very night, I believe). Vlad told me the house would treat me with the respect I gave it, and spouted off a very confusing saying about the “blood and bones of the home.” I promised him that Roger and I would come back and make a proper offer once we’d gotten to talk about it, but I knew then and there that this would be the house I wanted to grow old in. I had such a nice time I took a celebratory selfie with Vlad, but I should’ve checked the settings beforehand because Vlad didn’t show up in the photo at all. (Note to self: upgrade your dang phone already, Rosemary!)

After a few minutes with Vlad, I walked down the staircase to find Roger, his shirt torn and caked in sweat. He screamed “Where were you?!” which for me, was the final straw. I knew he was having a rough time since he accidentally broke an ancient Native American artifact in an old woman’s antique store the previous night, but taking it out on me? Ugh, men! I calmly explained to him that Vlad had led me on a tour of the second floor, but he continued to yell things like “I’ve been trapped in the attic for seven hours” and “Who the hell is Vlad?” I calmly walked past him and got back into the car. I didn’t want to tarnish the first memories of our future home with an argument.

As we drove home, our bitter silence was broken by the feeling of our baby’s first kick. Suddenly, our problems seemed so trivial. To hold any grudges against Roger would be petty. We loved each other, and the proof of our love was slowly growing inside of me. I smiled at him, and grabbed his hand to put it over my stomach. He felt the baby’s kick and smiled back. All at once, I saw our future together. Me and Roger, watching our little boy ride his tricycle around in our beautiful Victorian yard, feeling nothing but bliss.

I looked back at the house as we drove away and it faded into a thick layer of summer fog. I couldn’t wait to come back and make a future in that home — for me, for Roger, and for little baby Damien.

YOU BE YOU, AND I’LL BE BUSY

PAIGE LEWIS

chewing five sticks of Juicy Fruit, turning my jaw into a clicking, painpricked mess and reaching for another pack because hard work is defined

by a body’s wreckage, and I want you to know I’m hard at work writing my presidential acceptance speech: A dartboard in every garage!

A prison sentence for anyone caught explaining magic. You be me, and I’ll be the man standing at your fence, expecting compliments

on my new haircut. Now, be you and take this personality quiz. Do you scrape your fork against your teeth? Results are in: You’re the kind

of person who has to stop doing that. You be you, and I’ll be racing across the yard, trying to catch robins to prove how tender I am with

tender things. I’ll be Glenn Gould, hunched and humming at your piano until it suddenly springs a leak—the notes too full to hold themselves

together. I’ll be me again when I open the windows to keep our apartment from flooding. Don’t be the woman on the sidewalk below, drenched

and furious. Instead, take a turn as Gould. An older Gould—wear gloves indoors, tell me you can’t have lovers for fear of harming your elegant

hands, clamber about the bed for an hour being the man who always almost touches me. Then become the man who does.

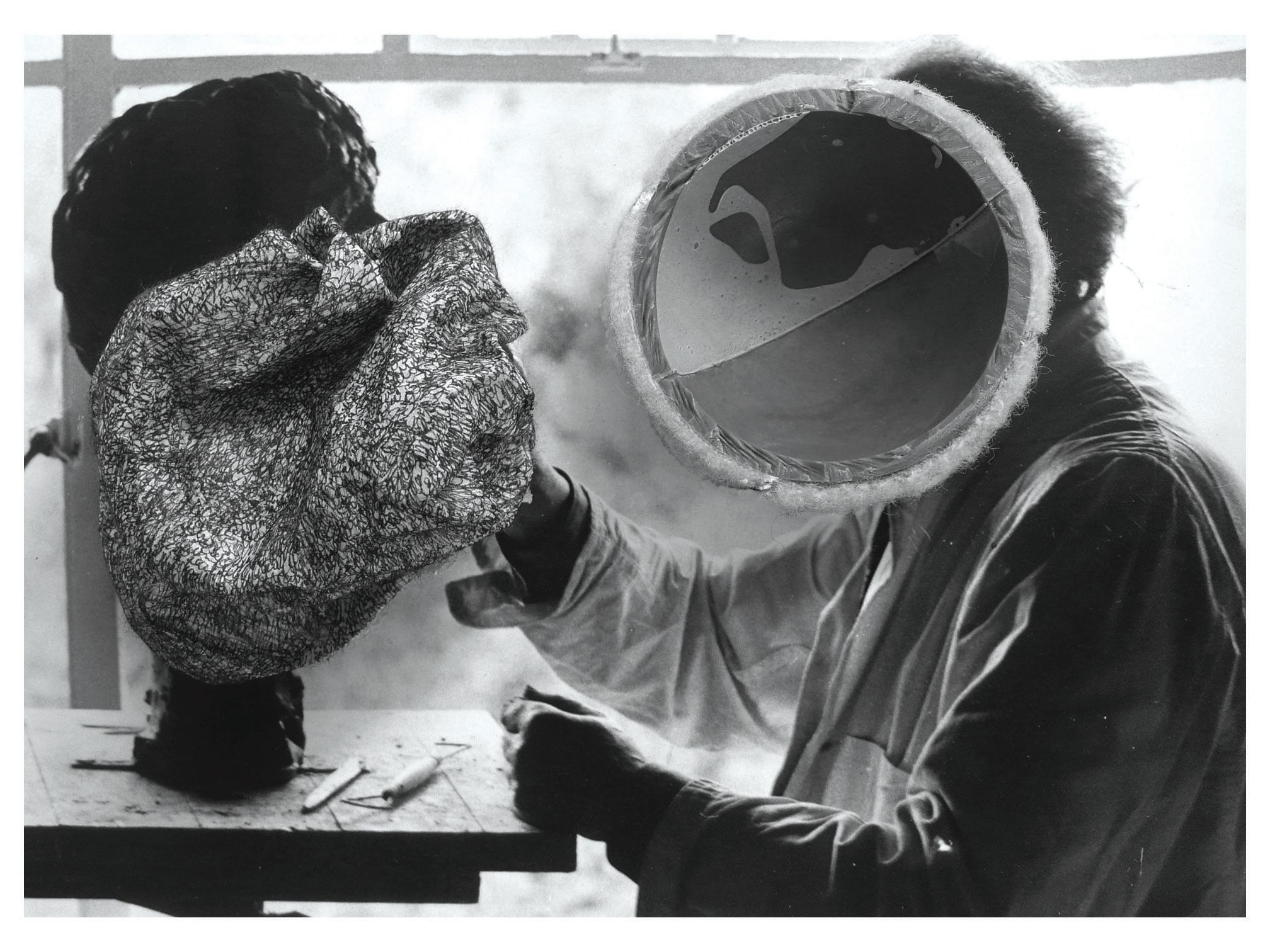

MARTIN KERSELS, FLOTSAM (ARMS SCAPULA),2010, PENCIL ON PAPER, 22 BY 30 INCHES ©MARTIN KERSELS /COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NY

NO ONE CARES UNTIL YOU’RE THE LAST OF SOMETHING

PAIGE LEWIS

Someone squealed about the ivory-billed woodpecker nesting on my back porch, and now there’s a line

of binoculared men holding buckets of mealworms and pushing their way into my home. I let them in

because I’d rather be host than hostage, though really, how could these lovers of red-headed grub-slurpers

be bad when they sport such splendid hiking shorts? They press their noses against my sliding glass door

and ask for the woodpecker’s name. I didn’t give him one—worried that if I named him, he’d never leave,

and honestly, I haven’t been a fan since I watched him raid a blue jay’s nest for breakfast. Well, I didn’t fully

watch—most of what I see, I see through the gaps of my fingers. This sort of looking has turned me

boring—even the sun’s been sighing Not you again when it sees me. And sure, there’s probably an alternate

universe where my gaze is unwavering, where I’m paid to name the newest nail polish colors—Fiddlehead

Green, Feral Red, Geothermal Glitter—where I don’t hate documentarians for letting nature be its gruesome self. Instead I’m here, listening to the demands of birdwatchers—they want post cards and t-shirts,

they want me to build an avian-themed carousel in the middle of my living room. I need them

to leave. At midnight, I turn off the porch light, and they swear they can still see inside his nest.

Someone asks Doesn’t he look happy? Yes, they all agree. Don’t you think he sounds like Fred Astaire with his

tap-tap-tapping? Of course! Dresses like him, too. I don’t know if it’s the hunger, the heat, or the hours

of not blinking that turns them cultish, but I go with it. I ask Shouldn’t he have a break from your

surveillance? Yes, a break. I’m giddy at the thought of being alone. I say It’s time to go home and rest.

They remove their shoes and lie down on countertops, in closets, and underneath my staircase. Wherever

there’s space, they fill it—body against tired body— pressed close as feathers.

OBSESSIONS: BREAKFAST

FRED ARMISEN

I am obsessed with breakfast. I don’t mean the history or art of breakfast cuisine in general. I mean the timing and the content of my own breakfast. Sometimes I think it’s all I ever want in life. For me, it’s ideally this: Grape-Nuts cereal with almond milk and blueberries, and two cups of strong coffee. I think about my breakfast the night before. Do I have enough blueberries in the refrigerator? Did I grind enough coffee? How much time will I have in the morning? I need at least an hour. My preference is to get up really early and have that time to myself. It gives me a moment to think. Once I’ve accomplished this part of the morning, I feel like I’ve already won the day.

I’ve never understood work-related breakfast meetings. I don’t like the idea of being distracted from getting that food and coffee down. I also think I’m a little self-conscious about what I look like when I eat. Eyes down, focused. I have often made sure to eat before a breakfast meeting.

I see the world through the eyes of breakfast. That is the most exotic part of traveling, to me. If someone is telling me a travel story, urging me to visit, let’s say, Serbia, the first thing I picture is me having coffee in a hotel restaurant in Belgrade. I imagine wearing a little jacket because it’s so early that it’s still chilly. Breakfast is when I feel the most like I’m in a foreign country. Even after landing and going through customs and checking in, it’s only the next day, in front of my breakfast, that I’ve said (quietly, out loud), “Wow. I’m in Iceland.”

Sometimes it’s not as easy to find the right kind of place, destination-wise. I have become wary of balmy, tropical resorts. The kind of place where everything is centered on relaxation and spas. They always seem to have long, winding pathways to get from one villa to another. That’s a warning sign to me. I think these places put so much work into their dinners and nightlife that breakfast is an afterthought to them. They assume that everyone is going to want to sleep late. I resent having to walk so far to find the building with the restaurant, and there have been many times where I was met in the morning with “we’re not open yet.” Nothing makes me angrier than those words. I resent it. That’s when I understand wanting to be a dictator. That would be one of my first enacted laws. All food-service establishments will be open at 5:00 a.m. Five. Just as a buffer for people arriving at six. “We’re not open yet” will no longer exist. When I am away from home, I have some reliable options, as substitutes for Grape-Nuts and blueberries. Oatmeal is always a good one. Starbucks usually has a simple little container of that. Toast with peanut butter is pretty filling. I’ve had to do a wheat bagel at various airports. And breakfast tacos! I put an exclamation after that because isn’t that what it’s like? Breakfast tacos! And of course, always the strongest coffee. That’s never a problem to find. That’s one of my favorite things about seeing the world move into the future. Even convenience stores are putting some effort into offering a version of specialty coffee. If I’m shopping for coffee by the pound, I really am a sucker for that D.I.Y. packaging. Where it’s made to look like a paper bag that someone stamped the label on by hand. Even if it’s fake, that’s what I reach for. They really know their customers.

I wrote most of this in the morning, after I had my breakfast. That’s when my brain works best. I am not kidding when I say this: I just washed blueberries in a little strainer and put them in the refrigerator for tomorrow.

OBSESSIONS: SHAKE SHACK IN NUMBERS

KARA BROWN

7/9/11: The most important day of my life until I give birth to someone. (And even then, we’ll have to wait to see how they turn out.) The first time I delighted in the culinary miracle that is Shake Shack was a blistering summer day in Madison Square Park with some friends from out of town. On my own, I likely wouldn’t have waited in the extremely long line because obviously lines are stupid. But when the energy of the Earth combines with the unyielding pull of fate, powerful things happen. I was changed. I was anew. I was Shake Shack.

8: The number of flights I’ve booked specifically through Terminal 4 at JFK Airport because Terminal 4 at JFK airport has a Shake Shack. When I moved to Los Angeles, my vitamin D levels soared, but my soul ached without the essential nourishment that is Shake Shack. From then on, anytime I returned to New York City I flew through Terminal 4 at JFK Airport because that meant I could grab Shack Shack right after I landed and enjoy one last burger before takeoff. Were there perhaps better, cheaper flights to New York that did not fly through Terminal 4 at JFK Airport? Perhaps. Did they have Shake Shack? They did not.

5: Friends and Family events I’ve attended after scamming my way onto the Shake Shack press list. Though, to be fair, I was a legitimate member of the media at the time, so it was less of a scam and more of persistent pursuance coupled with the Paul Ryan–white lie that I covered “food and culture.” 183: The page in the official Shake Shack cookbook where you will find a blurry version of me standing in the background at one of their Friends and Family events. We are forever connected, Shake Shack and I. They literally can’t do anything about it.

2,450: Approximate calories I consumed when, after suffering through a terrible, terrible day, I walked to the Shake Shack on Santa Monica Boulevard — to offset the calories, you see — and ate a ShackBurger, a Chick’n Shack sandwich, cheese fries, and a milkshake in one sitting.

1: The number of complete strangers who have invited me out to Shake Shack because I make my absolute thirst and devotion to this restaurant so publicly known. If I’m being honest with myself, even one person making this offer sort of seems like too many — but in an equally very real way, not nearly enough.

I WOULD DIE TO PLAY HARVARD

KRISTINA WONG

Last March, I was invited to perform my one-woman theater show “The Wong Street Journal” at Harvard. Well, it was more like I was scheduled to perform my one-woman show. Actually, let me put it this way. If playing Harvard was Isaac Mizrahi, me playing Harvard was Isaac Mizrahi for Target.

Usually when I perform at a school, I have a fee, accommodation standards, a contract. I won’t get on an airplane if these basic standards of decency aren’t met. Except if it’s Harvard, in which case I readily become the thirsty side chick crawling on scraped kneecaps at the first flash of Harvard’s 2am “You Up?” text.

Unlike previous Harvard guests like Rhianna and Hillary Clinton, I actually strong armed my “invitation.” I had been begging my friend, Professor Terry Park, who had been adjuncting there, to hook me up with a show for months. Finally, just before he was supposed to leave, he registered my performance as a campus event. He had found a window to get me in but Harvard wasn’t going to make it so easy: they would only pay a tiny fraction of my performance fee — I was essentially volunteering. Doing this show would mean hours of unpaid labor, using airline miles, and sleeping on Terry’s couch. Still, it was Harvard! I would do it. Now, like Terry, I could forever namedrop Harvard University on my resume.

Then, two days before the show, I received a death threat via Facebook:

I’m gonna kill you one day. Count on it. You fucking piece of shit. For harassing the President constantly! I’m also going to terminate your twitter account. YOU ARE FINISHED. March 6th. Coming for you.

It had been only three months since the election — you know, the one where the possibility of Armageddon and getting deported to a concentration camp in our lifetime became very real? I grieved the election results by tweeting at Trump and his family hourly. I gained 20k new Twitter followers in three months. It was like I was becoming someone who was actually invited by Harvard to play Harvard!

I made many enemies via Twitter but this was my first death threat. Unlike other murderers, who generally prefer anonymity, Brian Martin’s face and identity was made plain. His profile said he lived in Southern California. Was Brian Martin actually going to fly across the country — with weapons — to kill me at my March 6th Harvard show when, with much less effort, he could just drive to Koreatown and kill me in my own home?

And that’s when I realized how big I sounded. Brian Martin didn’t want to kill me in Koreatown. Anybody can get killed in Koreatown. Brian Martin also wanted to put Harvard on his resume.

Because this was a potentially life-threatening situation, my first instinct was to tell Facebook. I soon realized that that was a bad idea: nothing deters an audience from attending a one woman show more than the possibility being killed (...and the fact that it’s a one woman show). If Brian Martin saw me panic online, it would give him the satisfaction of knowing he’d won. I’d have to remain silent, as if I never saw the death threat. I would have to proceed as if I had never been deterred.

With my flight 36 hours away, I called Terry. He got us on the phone with the Police.

“This is Saaaahgeant Paaahker of the Haaahvaaard Police Depaaaahrtment.” Sargeant Parker thought this death threat could be a hoax but should be taken seriously. He recommended that I tell my neighborhood police station. For my show, he recommended an armed plain clothes officer escort me to campus and watch from the audience, an armed officer patrol the box office area, and to be extra safe, a third officer scan every audience member for weapons.

“Haaarvard Police Depaahtment doesn’t pay for this. Your depaaahment does.They’ll have a billing code we invoice.” But we didn’t even have a real bed for me to sleep in. This was an Isaac Mizrahi for Target backdoor gig at Harvard, remember?

“So, how much of your fee are you willing to sacrifice for security?” Terry asked me that night. I was already doing this show at a loss and now I had to ask myself: Exactly how much was it worth for me to prevent a potential massacre at Harvard but also say that I played Harvard? How much was it worth to save the lives of the smartest, most potentially useful Americans in this country? And if I cut any corners on security, could I live with myself if someone got hurt?

Before going to the Koreatown police station that night, I googled Brian Martin’s Facebook page and found him on “Encyclopedia Dramatica” — a wiki site that documents internet trolls. Apparently, Brian and his twin brother Kevin notoriously harassed people across the internet. They even once threatened the National Weather Service and posted a video of them clowning the FBI at their house. This website offered up their address.

“Officer, can we bust them? Can you go to this guy’s house and arrest him?”

“A detective will look at this and get back to you in a few days.”

“Will they call me before I leave for Boston?”

Terry called at midnight my time. He had been thinking up Death Threat DIY Security ideas:

“I have found two professors, one is a professor in African American studies. The other is Latino. They are willing to act as our security.”

“Terry we can’t turn the smartest men of color in the country into our bouncers!”

“How about this? We do a fundraiser! From your Boston friends coming to the show!”

“Hey, I’m so glad you are coming, can you chip in $5 so we don’t die in a massacre?!”

We googled the cost of shirts that read “SECURITY” to put on the student ushers. Only $10 with one day shipping on Amazon Prime! And cop costumes were only $22. And bonus: they featured ripaway pants and user reviews like “Great for a wannabe Magic Mike!”

Luckily, a man named Lateif happened to email me right then. Lateif was a friend of a friend who owned a gun range in New Jersey . He had added me to his email list about the monthly “gun basics” classes he offered in Jersey City. Naturally, I wrote Lateif about what was happening.

“Tell me where and when your show is. Send me everything you have on this guy. I will bring my students and make this a project for them. It will be my pleasure to protect you.” Would Lateif really bring an armed militia five hours away from New Jersey to protect me? And that’s when I realized how big I sounded. Lateif also wanted to add Harvard to his resume, so he can forever namedrop that he once stopped a massacre at Harvard.

It was a feverish sleep that night. How was it that doing an engagement at the most wellendowed university in the country would mean putting professors in sexy cop uniforms, crowdfunding for security, and bringing in my own armed militia?

In the morning, Terry called me.

“I talked to the Provost and explained the situation. They’re going to pay for all the security detail. They take this very seriously and said it wouldn’t be an issue.” This was the same Provost who couldn’t cough up the cash for a decent honorarium or flight for my visit. Apparently, they had found the money to prevent a massacre, but this still didn’t make any sense. They had money for security but not the person security was there to protect. We were relieved of course, but Terry had one last request:

“Can you please can go silent on Twitter? Just until the show is over? Then you can go inciting all the death threats you want.” I made him no promises. I refused to let Brian Martin think he won. On the day of the show, I had not heard back from anyone at the Koreatown Police Department (I wouldn’t hear from them until three months later).

As I entered Harvard’s Agassiz theater, I barely recognized what a big deal I looked like. An officer with a shiny gun in a holster patrolled the hallways. Another officer in a yellow safety vest with a metal detector wand pat down every audience member. The undercover officer packing heat was unmistakably the big white guy hunched over in the back of the theater.

I scanned the audience for Brian Martin; I only saw hundreds of Asian faces looked back at me. Then I started the show. The audience loved it; even the plainclothes officer cracked a smile. When I took my final bow, I wasn’t greeted with a hail of bullets, but a standing ovation.

It took me two months to get paid by Harvard. They paid me even less than what Terry helped negotiate, and they somehow docked my check for the cost of the bag check officer. It was, by any measure, the toughest gig ever. But hey, at least I can say that I played Harvard.

STEPHANIE WASHBURN, CONGRATULATIONS, YOU’VE MADE A WONDERFUL DECISION (FLOUR), 2017, ARCHIVAL PIGMENT PRINT, 10 X 8 INCHES

THE PARTICULARS OF BEING JIM

AMY SILVERBERG

For a while, I was sleeping with a man I’d met through a friend. He had a bad reputation for sleeping with women and never calling them again. He wanted to be a stand-up comedian, and though I’d heard jokes like his before, he had a deliberate way of delivering them that tricked you into thinking they were something new. It had to do with timing. Especially when he was up on a stage and the audience was drunk and susceptible — everybody laughed. That’s how I met him. I was listening to him tell jokes at a dive bar called Pete’s that had a rotating globe with multicolored shapes, and my friend said, “Do you wanna meet him? I’ll introduce you.”

This was my friend Tina who can be a real ball-buster. Really, she just talks out of turn but so much so that men need a special name for it. For a few years, she worked as a flight attendant and a lot of men really liked her. She’s a redhead too, which seemed to help. She could tell you stories about those years that would make you never want to leave the house. Or, I guess, they might excite you. It depends.

Anyway, when I met Jim that first night, I was sitting under the rotating globe watching red triangles and green trapezoids float over my hands. He walked over to me and said he’d like to take me home. He had the posture of a man uncomfortable with his weight, maybe with his whole body, his hands placed delicately over his stomach as though to hide it. I knew the posture because I’d recently gone through my own kind of transformation. Was this part of his trick for taking women to bed? Approaching them with a kind of humility he never showed on stage? It worked. Whatever it was, it worked.

I was sure Tina had sent him. She was trying to help. My parents were separating and I was working as an accountant. I’m in my 30s, so their separating shouldn’t have mattered, but it did. I couldn’t explain it. My younger brother wasn’t doing well, mental-health-wise, so there was that too. I spent a lot of time napping and looking at old photo albums. I had this one leather-bound album my parents had given me for my high school graduation, and I studied each photograph as though I were preparing for a test. One in particular, in which my brother had a parrot on his shoulder, and their heads were bent together, as though conspiring.

I went home with Jim that night, telling myself we’d just talk, but there was a corner of my mind — like a light on in the top floor of a dark building — knowing that maybe I’d let him get away with something. He lived in a basement apartment. Through the window, there was only a dirty horizon line, as though the building were sinking into the street. For a moment, I entertained the thought of staying too long and being buried. What I remember most about that night was that fucking Jim was pretty similar to fucking anybody. Nude, I didn’t notice his extra weight — he was like anybody else, an arrangement of skin and body. He moved like an athletic person and he smelled like green chewing gum. It was only afterward when he pulled the covers up to his chin that I remembered the way he looked in clothes, how uncomfortable. I could relate. It was hard to navigate the world in your 30s.

He was a sensitive guy, more than you’d think by the way he told jokes. When he spoke to me that night, it was in a calm, serious tone — like the voice of a recovered addict, of having been through something and survived. He wanted to know about my parents and my brother. He wanted to know because I kept hinting at it, wanting to be asked, the way you want to rub a canker sore with your tongue. The fact that he had a bad reputation made it easier. And he had stories he wanted to tell too. He told me everything — how he gained the weight and why. It’s a funny thing about people, how much they’re covering up. He told the story of his life in the same deadpan delivery he’d used on stage and I said, “That’s it Jim. That’s your stand-up act.” I wasn’t wearing any clothes and we had sex again, this time standing up against the doorway. It was the sort of sex you’d be interested to see yourself having — the kind that rarely looks as good as it feels. After that, we wrapped ourselves in blankets on the cold, tile floor of his kitchen, and I asked what was the worst thing that ever happened to him, and for some reason he told me. I won’t repeat Jim’s story here, but it was the kind of thing that broke your heart even while you were laughing, only you didn’t feel the break until much later. It had to do with a woman.

I felt it that morning during my cab ride home, in the orange wash of dawn, looking into the windows of other people’s cars. The driver wore multicolored beads in his hair and every time he turned to check his blind spot, the beads clicked together.

Jim and I kept sleeping together. We sort of fell into a relationship, the way you slip into warm water. Neither of us seemed to notice how it happened. He often made me this pasta dish. It was nothing special — garlicky red sauce, penne — but he always went to the trouble of carefully grating tiny curls of Parmesan, the same-sized heap on each of our pasta piles. That stuck with me.

Still, it didn’t last. Sleeping with a comedian is not the same as dating one. It was strange to hear a long, terrible fight shrink into one of Jim’s punch lines. Or worse, to hear my own bad qualities — the way I chopped vegetables so loudly that the cutting board rattled, or the highpitched turn my voice took on whenever my father called — tossed off at a bar.

“Don’t worry,” Jim said, when I protested. “The world is full of people having the wrong impression of us,” as though he didn’t have anything to do with it.

After our relationship ended, we became friends, which isn’t something I normally do with people I’ve seen naked. But I’d confided so much in Jim, the confessions felt like entering a series of doors I couldn’t return through. It seemed like there could be nothing worse than letting him loose in the world, suddenly just a stranger filled with my secrets. Plus I assumed he was a still hung up on me. I was still hung up on him, and occasionally I’d walk into a room and smell the same peppery scent of his cologne and that would be enough to unhinge me. It’s strange, when the smell of dinner seasoning is enough to unhinge you.

A few months later, I went to another one of Jim’s shows and I brought Tina with me.

When we arrived, people were waiting in line, stomping out the weather on the sidewalk and exhaling puffs of white breath. People were paying for tickets. When Jim and I had first met, he’d been lucky to get an actual stage, let alone get paid for it. I told the bouncer my name and he waved us in. Tina and I sat in the front row.

As soon as Jim began, I knew his act was worth the money people paid. It wasn’t just his delivery or his timing. He was saying things no one had heard before, the particulars of being Jim. I saw it in the audience’s reaction, which was what Jim had taught me to look for — the way they looked at each other in surprise, as though they couldn’t believe what was happening, being made to laugh this way, like it was being pried from their mouths against their control. Tina kept doing it to me, looking at me with her mouth wide open like a cornhusk doll in which all of the features are exaggerated. In my ear, she whispered, “This is the best he’s ever been.”

Jim took a sip of water and scanned the audience. I could see the shine of sweat on his forehead, slick in the overhead light. He placed his hands over his stomach, the unconscious gesture he made in between thoughts. I felt him pause over me and I wondered if the rest of the audience saw it too — if they knew we’d been in love.

Jim wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and said, “I’m gonna tell you all something I hadn’t planned on saying.”

Tina jutted her elbow into my ribs.

I hoped he would launch into the story he told me, the one about his sister falling into a lake and almost drowning when he was 12, and that night, he’d been so stressed he’d eaten all of the junk food his mother had brought for the trip, until he had to vomit because there was nowhere else for the food to go. Ever since then, he had trouble with eating — a conundrum, he called it. It wasn’t funny the way I said it, but Jim had a way of slanting it differently, you couldn’t help but laugh. I was glad I hadn’t ever repeated the story, especially to Tina, who I’d been tempted to tell. I would have butchered it.

“I want to tell you guys a love story,” Jim began. I felt my pulse quicken. I thought suddenly of the pasta, of the tiny Parmesan curls.

But it was a different love story than the one I had in mind. It was a story about a woman back home, in Nebraska, who had wanted Jim to marry her. “We’d been together a long time,” he said, “before I moved out here. I tried to meet somebody else. I tried to forget about her; I tried to lose myself in other people.” He told jokes about her, about their relationship, but it wasn’t like the jokes he’d told about me. There was a new tenderness in his voice, even the way he said her name, as though the name alone was not just a name, but a feeling.

“Well I thought, why not announce it here? We’re getting married,” he said, and whole room erupted in applause, like a studio audience prompted by a cue card.

I remembered what Jim said about the world being filled with wrong impressions, and I couldn’t decide just then if his bad reputation was wrong, or exactly right. Maybe he’d simply always been loyal to another kind of happiness. It had not occurred to me that he had also been looking for a temporary salve, for a little pain relief in the form of an arrangement of skin and bones, of another body.

Tina and I looked at each other. When I managed to look up at the stage at Jim, his face was grim. I felt Tina’s small hand grip mine. Tina knew my family too, she’d come to the hospital for people with emotional problems to visit my brother, and she was capable of staying on the phone for a long time just listening to me breathe. We knew each other from high school time, which now felt like a few lives ago.

“He’s always been a fucking asshole,” she whispered.

I didn’t wait for anything else. I stood up and walked slowly toward the door, past rows of sitting people, knocking against their knees, feeling everybody’s eyes on me.

It was cold outside. Though I couldn’t feel it, I saw my breath as I hailed a cab. The redfaced driver asked me where I wanted to go. A pigeon careened drunkenly passed the window, and I thought about the parrot my brother used to own. In those last days, it survived eating stale cheerios out of a box it had found wedged beneath the kitchen pantry. It was strange what you could get used to.

Inside the damp smelling taxi, a laminated photo of a smiling woman hung from the rear view mirror.

“Tell me a joke about your ugly wife,” I said.

The driver turned to look at me over the seat, and I saw my own face in the rearview mirror, waiting for my insult, to receive whatever I deserved. He shifted the car into drive.

He said, “Just repeat the address please.”

WHAT IS IT ABOUT VELVET?

RUTH MADIEVSKY

that makes me feel like every hair on my body is running away? This is my least favorite genre of friction, worse even than the screech of tires across pavement or the sound of a knife fucking a plate. What I am trying to say is, the key is widowed without the lock. Sometimes I think revulsion is the only way to know I’m really here. Not everything that moves is alive— not viruses, not wind, not this feeling creeping through me that I should have been left in the womb longer. I shouldn’t have led with the velvet. What I mean is, sometimes little things like touching a pillow the wrong way send me into the wordless, chrome place where my insides are safety pins. At least in there it’s quiet. At least for now the pins are closed.

BORING HEART

RUTH MADIEVSKY

I want to slip inside the tree that faces my bedroom window, to wear its branches like sleeves and to be the tree’s blood, the tree’s liver and throat, to hold photosynthesis on my tongue, the xylem and phloem of it slow-dripping like molasses, dark beer from a tap that started flowing 385 million years earlier, before the dinosaurs, before the first mother held her young to her breast. I want to sleep in the tree’s pocket and have epiphanies about my sexuality. I want to look at literally anything the way my neighborhood raccoons look at each other, the ferocity of their love enough to power a casino, to light all the lamps in all the slot machines the way rods and cones light the eye. Humans have the most boring hearts of any animal. Ours can’t turn popsicle in winter like the wood frog’s, or propel our blood six feet skyward like the giraffe’s. We’re lucky if they can survive our hot dogs and cigarettes, if they can keep the lights on in our brains and kidneys. I feel bad when the banana cream pie I shared with a friend gloops through my arteries like an omen. I feel worse when it doesn’t.

OBSESSIONS: QUIET CAR JUSTICE IN THE AGE OF TRUMP

DAVID LITT

Over the last year, I’ve frequently found myself taking the train from New York (home to media and publishing) to Washington (home, these days, to corruption, incompetence, and my apartment). In other countries, European countries, I imagine train travel means chic surroundings and flirtatious glances at godlike Swedes. In the United States, train travel means the inevitability of delay, the possibility of derailment, and seats that smell faintly but unmistakably of misspent time.

And yet I love it. I look forward to it. The reason? The quiet car.

The uninitiated might assume the quiet car is the railroad equivalent of noise-cancelling headphones. But there’s no soundproofing. No streamlining. The only thing setting it apart from the rest of the train is the sign politely reminding passengers that talking must be kept to a whisper. Without any technology to disrupt the system or bouncer to keep order, the quiet car is quiet only by agreement. It’s a miracle of civilization, not design.

This brings me to my real obsession: quiet car justice. Because sometimes — once every two trips, say — the sanctity of this mobile oasis is violated. Preening finance bros. Drunk Phillies fans. Someone (gasp, shudder, heaven forbid) who decides to take a call.

In that moment, a hush falls upon the quiet car. Every eye rolls in the direction of the offender. A wave of excitement mixed with dread runs through each of us, as though we’re 18th-century Londoners about to witness a public hanging. We hold our breath. Who will step forward? And then a self-appointed executioner rises. Stepping toward the loudmouth — or, more likely, craning over the seat — they prepare to deliver the fatal blow.

“Yeah, hi, excuse me. This is, um, the quiet car?” The tone is a perfect blend of righteous condescension, a cross between the Ten Commandments and NPR. Here’s the thing. It always works. Every time. The talker goes silent. The phone is hung up, the discussion moved to the cafe area. The oasis is blissful and peaceful once again. I’ve always wondered what would happen if someone refused to obey the sign, insisted that they would keep talking and by the way screw you for butting in. But I’ve never found out. I’m not sure I ever will.

A few months after the election, I dispensed quiet car justice myself for the very first time. Nestling in my seat afterward, I felt as if my skin were aglow. Yes, some of it was the returning silence, so rare in the outside world. But it was more than that. The quiet car is a place where norms are upheld. Where popular will is respected, and the whims of selfish egomaniacs are not. For a few brief hours after leaving New York City, the world is fair. The people are good. In the quiet car, justice prevails.

And when the train pulls into Washington, I find it just a little bit easier to live in 2018.

IRONY AND THE NEW WHITE SUPREMACY

SARAH LABRIE

Last December, I flew from Los Angeles to Houston, my hometown, on a work trip for a choral piece commissioned by the Los Angeles Master Chorale. On the trip also were the piece’s composer, Ellen Reid, and our researcher, Sayd Randle, an anthropologist based in New Haven. One night, after a full day of work, we met up to debrief at Black Hole, a coffee shop in the city’s arts district. We each had a glass of wine. It was late, the cafe was half empty and we weren’t paying as much attention as we should have been, perhaps, to the people around us, listening to us talk.

The choral piece was a research-based project whose text I’d been hired to build from archival material and recorded interviews. After the three of us consolidated our data and discussed our plans for the following day, our conversation turned, as it often did, to what it felt like for each of us to navigate our respective male-dominated fields. At one point, I mentioned how exhausting it was to feel as if others thought the progress I’d made as a writer was the result of pity on the part of white gatekeepers, when really, I’d been working hard for years, clawing my way forward across an unforgiving landscape in which it often felt impossible to make any headway.

At some point, I looked up and caught the man sitting one table over from us Googling Confederate flags. I dismissed it — the cafe sat between two local universities and I figured he was working on a project for class. Later, I looked up again and saw that that he’d made the flag his desktop background, angling his screen ever so slightly to face me, as if to make sure I saw. After Sayd and Ellen left for the night, I stayed behind to work. I saw then that the man was wearing a pair of red New Balances that looked recently purchased, weeks after New Balance had been declared the official shoe of the so-called alt-right. I realized that my brain was working overtime to justify what I was looking at. Earlier I’d made eye contact with the man and smiled as he sat down near us and he had not smiled back. I’d spent the past few months reading about the rise of white nationalist groups buoyed by Donald Trump’s election. For some reason, it had not occurred to me that their members might frequent the same coffee shops I did.

I texted my boyfriend who told me to leave. I texted Ellen who also told me to leave, but not before I complimented the man on his shoes. I decided to stay. I’d never seen a white supremacist in the wild before — or at least not one so eager to be identified — and I didn’t think I would again. I had questions.

But before I could walk over to his table, a friend of his arrived at the cafe and greeted him in French. The man in the red New Balances magnified a browser window, blocking his desktop screen. The two continued their conversation, loudly enough for me to overhear, in French, a language I speak fluently, which is not something they could have known.

The man’s name was Thomas. He was a law student at the University of Houston and he was 35. When he was younger, he’d been a student of art history in France at the Sorbonne and then gone on to study film. He’d spent five years trying to become a director and now, he told his French-speaking acquaintance, he regretted those years bitterly. He’d been naïve. He’d had his head in the clouds. Now he had his feet planted firmly on the ground. He felt bad about wasting his youth. It was the biggest regret of his life.

Listening in, I wondered: Had he always been a white supremacist or had he discovered this latent interest after failing to become a filmmaker? If he’d managed to make it in the field of art history or film, would his future have turned out differently? I couldn’t help thinking of Hitler and his two-time rejection from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. I thought about what it means that the all-consuming desire to create can warp itself, in certain people, into the desire to destroy.

Then there were the parts of their conversation I didn’t understand, French words that slipped past me under the pounding beat of the disco music playing over Black Hole’s speakers. Why, for example, did the person Thomas was talking to, suddenly, out of nowhere, reference the flight of the Jews across the desert? Why did he make a point of noting that someone he’d spoken to about a job recently was “part Indian”? And why were they both speaking about the German language and about the Netherlands? Was his friend a neo-Nazi too?

After Thomas’s friend left, I left as well. It was after midnight and I was tired. More than that, I felt wrung out and empty and mad. Nothing about the experience seemed funny or intriguing anymore. I’d been tacitly threatened and made to feel scared in my own neighborhood, near the street where I’d grown up, in a city I loved. I knew people from other parts of the country expected this kind of thing from Texas, but I didn’t.

Houston boasts one of the most diverse metropolitan areas in the country, and is one of the only major American cities that is not majority white. The city has a black mayor who followed on the heels of a two-term mayor who was, at the time, the only openly lesbian mayor in the country. Though my friends from the East Coast tend to assume the South is a backward bastion of racism and ignorance, the first time I’d ever felt blatantly discriminated against was in my 20s