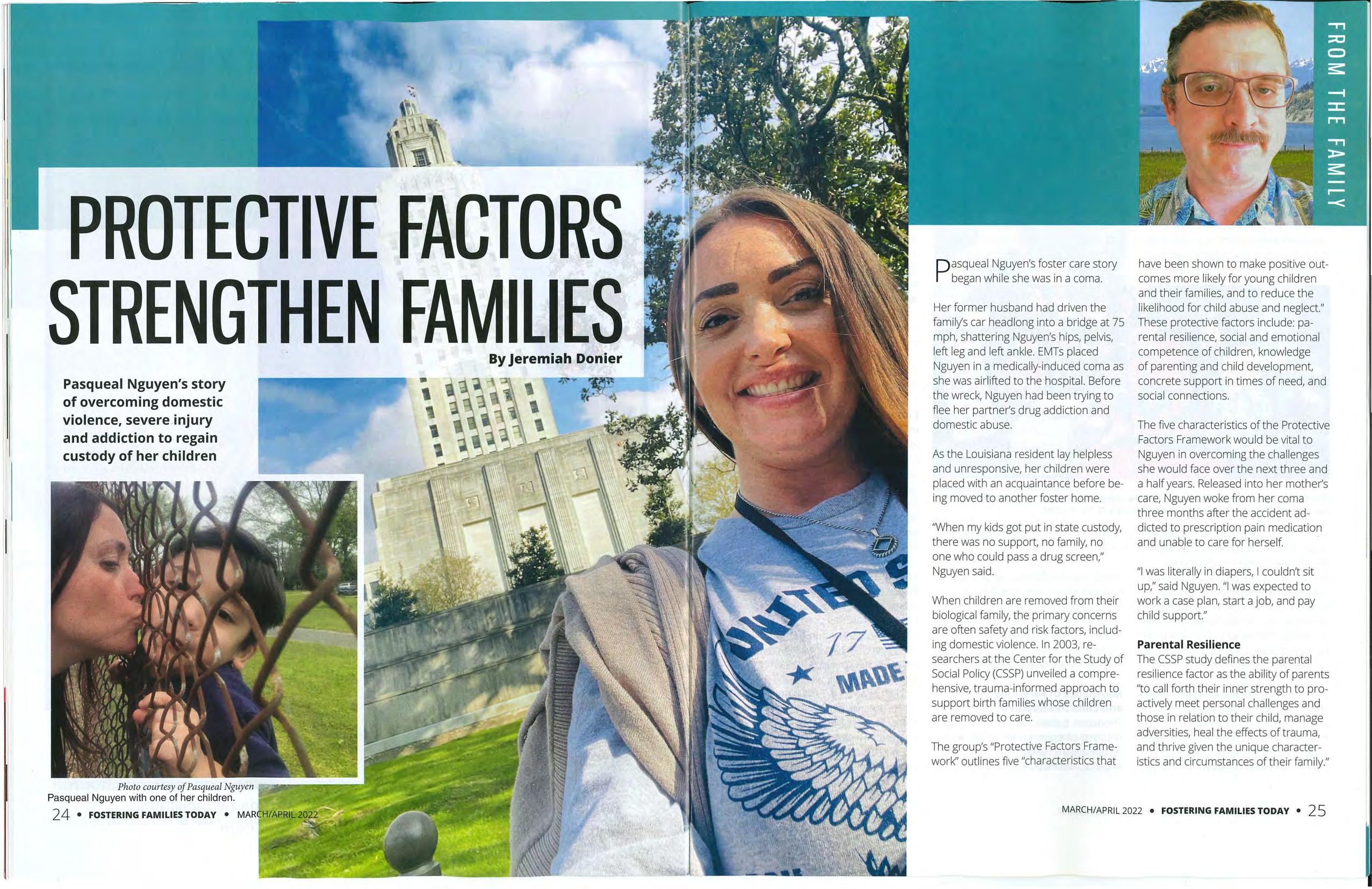

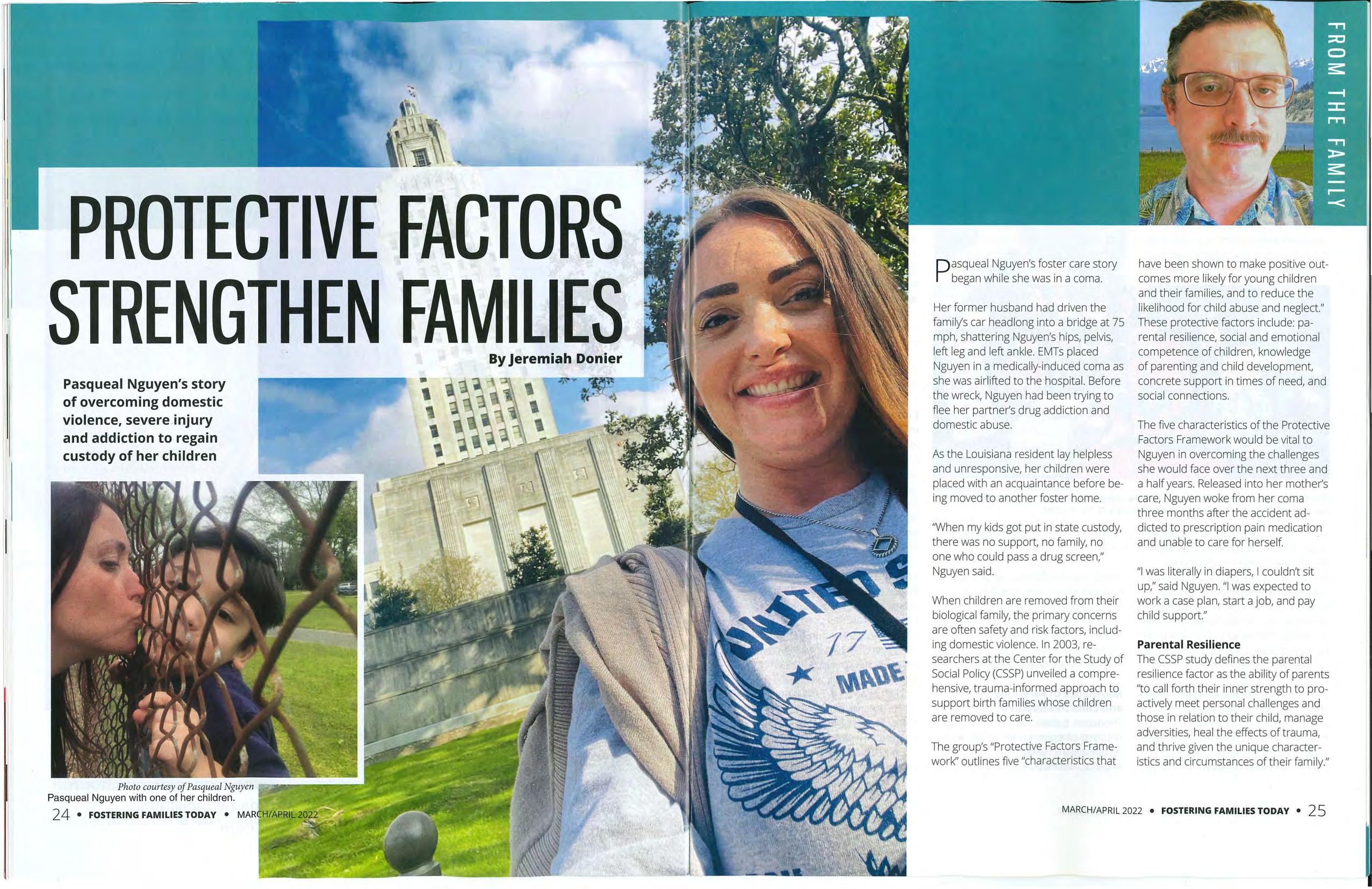

PROTECTIVE FACTORS STRENGTHEN FAMILIES

By jeremiah Donier

By jeremiah Donier

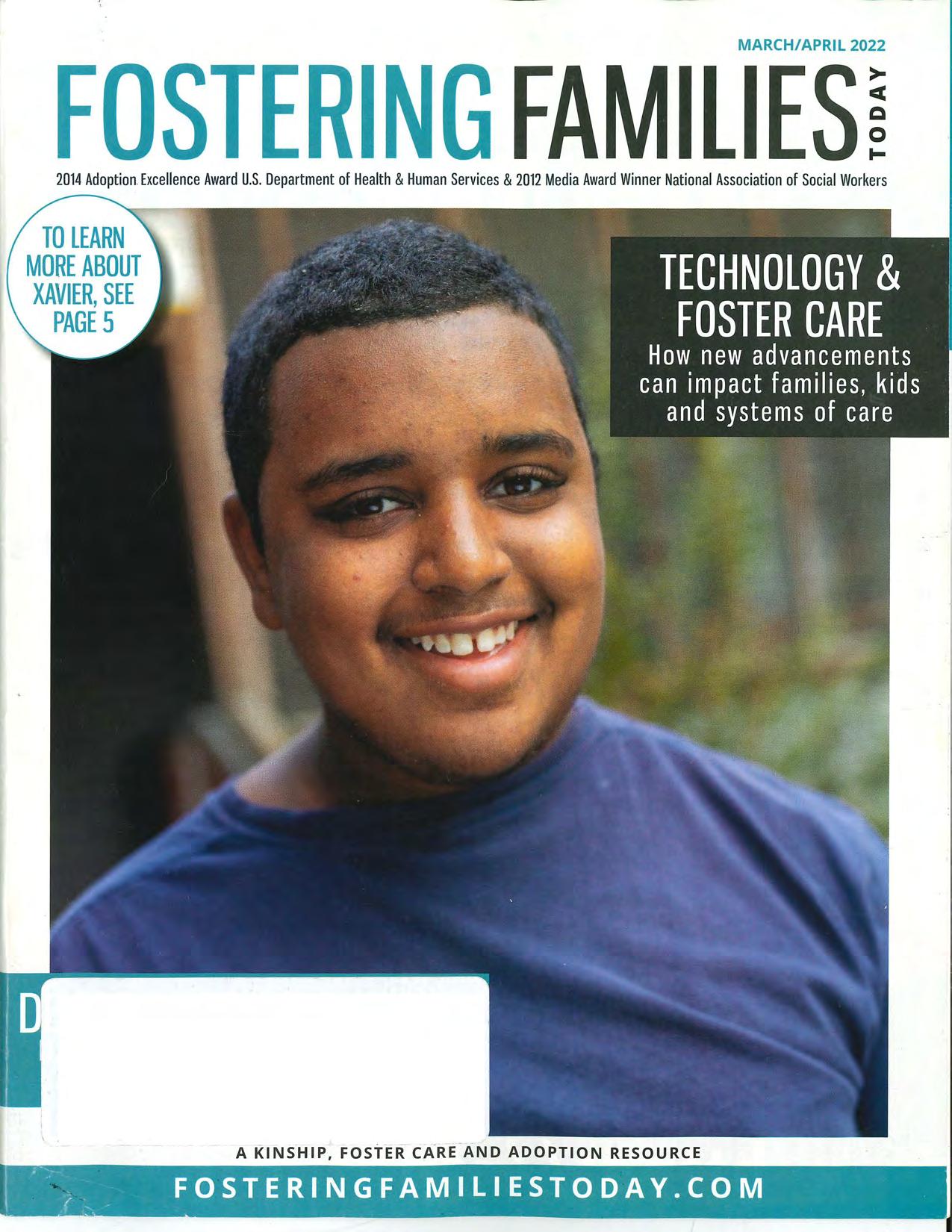

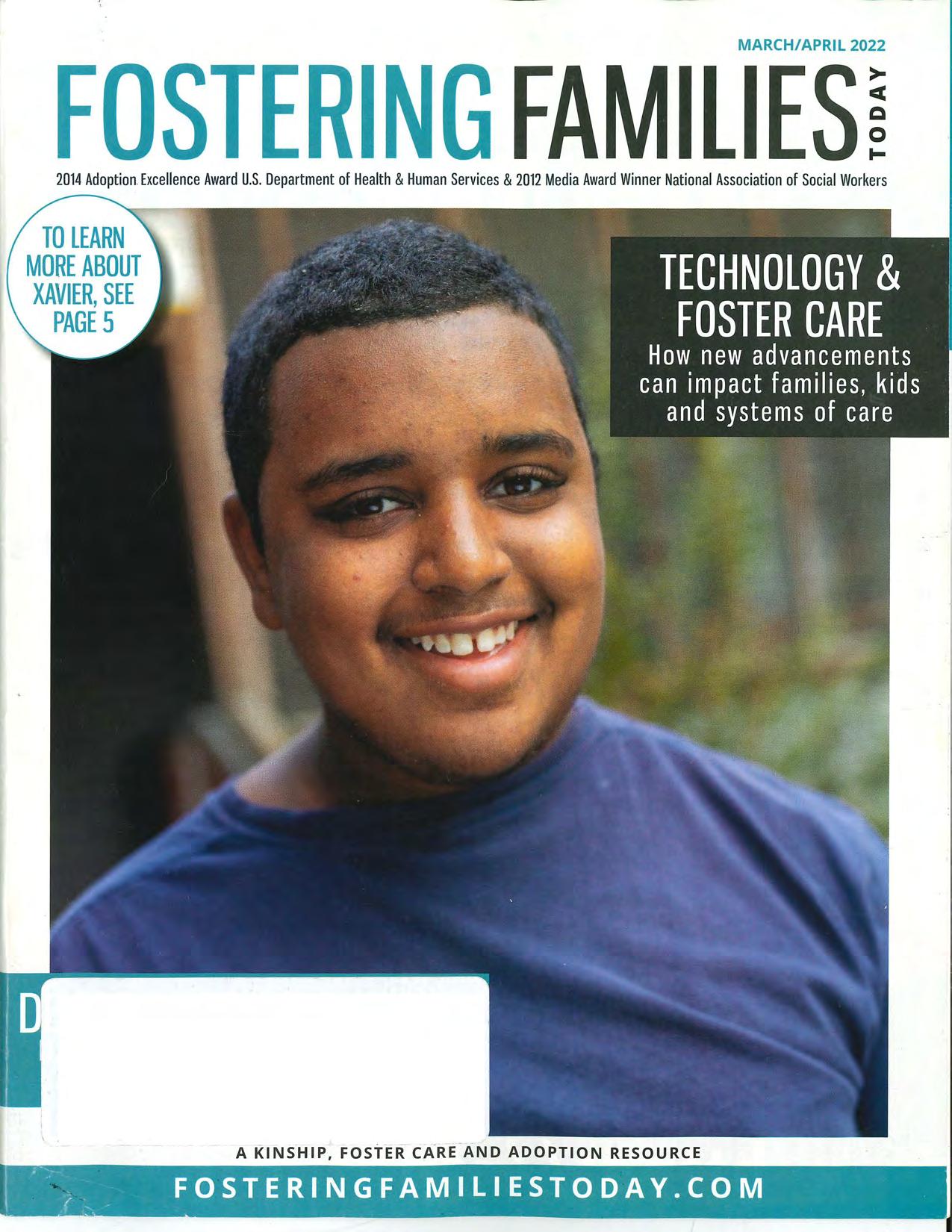

Pasque al Ng uye n's st ory of overcoming domest ic violence , severe -i njury and addiction to regain custody of her children

Pasqueal Nguye n's foster care story began wh il e she was in a co m a.

Her former husband had dr iven the fam ily's car headlong into a bridge at 75 mph, shattering Nguyen's hips, pel v is, left leg and left ankle. EMTs placed Nguyen in a medical ly- induced coma as she was air lifted to the hospital. Before the wreck, Nguyen had been trying to fiee h er part n er's d r ug add ict ion a n d domest ic abuse.

As the Louis iana resident la y help less and unresponsive, her chi ldren w ere placed w ith an acquaintance before being moved to another foster home

"When my kids got put in state custody, there was no support, no fam il y, no one who cou ld pass a drug screen," Ngu y en sa id

W hen children are removed from their biological famil y, the primary concerns are often safety and risk factors, including domest ic v io lence. In 2003, researchers at the Center for the Study of Soc ial Po licy (CSSP) unve iled a comprehensive, tra u ma-informed app r oach to support birth famil ies whose ch ildren are removed to care.

The group's " Protecti ve Factors Framewo rk" outlines five "charac teristics that

have been shown to make positive outcomes more li ke ly f or young children and the ir fam il ies, and to reduce the likel ihood for child abuse and neglect." These protective factors include: parenta l resilience, social and emotional competence of children, knowledge of parenting and chi ld deve lopment, concrete support in t imes of need, and socia l connect ions .

The f ive character ist ics of the Protective Factors Framework would be vital to Nguyen in over coming the chal lenges she wou ld face over the next three and a half yea rs. Released into her mother's care, Ngu yen woke from her coma three months after the accident addicted to prescript ion pain medication and unab le to care for he r se lf.

"I was literal ly in diapers, I couldn't s it up," said Nguye n "I was expected to wor k a case plan, start a job, and pay child support."

Parental Resilience

The CSSP study defines the parenta l resilience facto r as the ab ility of parents "to ca ll forth the ir in ne r st r ength to p r oactively meet personal cha ll enges and those in relation to their child, manage adversities, heal the effects of trauma , and thri ve given the unique characteristics and circumstances of their family."

Nguyen would lean on her personal, inner strength throughout the years it took to regain custody of her children, sharing "It was a hard-won experience."

Social and Emotional Competence of Children

CSSP researchers note early childhood is a time of opportunity and vulnerability. Referencing previous studies, the group found the social and emotional competence factor is connected to cognitive development, language skills, mental health and academic success. They note t h at these are strengthened

"My ex was struggling with addiction, had a lot of control issues and, couldn't accept my son had severe autism," said Nguyen. "So when I started different the r ap ies for my son, I had to sneak around to get help."

Then as she later recovered, Nguyen comp leted the initial fam ily case plan, drug court, and began to put her life back together. She also understood that social and emotional competence was key to her children coming home. The matter became cr it ical when Nguyen learned her o ldest son h ad

However, because Nguyen only had one hour per week with her children, it was difficult for her to demonstrate her parenting knowledge during visits.

'The caseworker's report noted I was runn ing circles," said Nguyen. "Multip le kids were running all over the place, I was trying to get in as much time with each kid as possible . It was horrible ."

Nevertheless, Nguyen was able to demonstrate she understood her children's' deve lopment needs, and her children began com ing home. Then, a week befo r e her case was set to close, Nguyen's li fe began to fa ll apart again.

"I was in relapse. I got involved in another abusive relationship, and similar things started happening," said Nguyen. "However, this time I left. I was clean but I had nowhere to go."

Concrete Support in Times of Need

when children are nurtured by caring adu lts. Th is includes helping ch ildren identify their own feel ings, apprec iate the feelings of others, and guiding chi ldren on what behaviors are appropriate. Conversely, if children lack caring developmental support, they can struggle with feelings of remorse, indifference or insecurity and have d ifficu lty communicat ing with others.

Before her life fell apart, Ng uyen knew strengthen ing her oldest ch ild's social and emotiona l competence was critical. However, circumstances forced Nguyen to seek support in secret, while her partner was working away from home.

been physica lly and sexually abused while in foster care.

"Being severely autistic, my son was non-verbal, but I cou ld tel l he was abused it was horrible. I will never forget the way he looked," said Nguyen. "However, when I saw him, I was so grateful he was with me, I could protect him, and finally be a mom aga in."

Knowledge of Paren t i ng and Ch ild Development

This factor is described as helping parents and caregivers understand what resources are needed during a child's expected developmental stages.

All families need help sometimes. The CSSP describes the concrete factor as assisting parents to find and receive needed support. Strengthening families is about ensuring everyone has what they need to thrive, including hea lthy food, clean water, safe shelter, health care and legal services.

After discuss ing the chal lenges she faced during a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, a co ll eague identified a rundown trailer as potential housing When her social worker inspected it, Nguyen was told it would be acceptable, if it could be made more hab itab le. However, as a food serv ice worker, Nguyen did not earn eno ugh for the necessary repa irs Her "concrete" support from a nearby church's Celebrate Recovery program. The members provided materials and muscle to make the necessary fixes.

Photo courtesy of Pasqueal Nguyen Pasqueal Nguyen with her children du r ing the holidays . She worked to ove rcome addiction and an life-altering accident to regain custody of her children .The group also paid the family's first three months of rent and utilities.

"Within 24 hours, new floors, walls and cei li ng were in p lace. I a lso appl ied for d isability financ ial s u ppo r t fo r my son," sa id Nguyen. 'The church's support and d isabil ity approva l helped my family start to find financial stability."

CSSP researchers say asking for help is not easy. Parents in crisis might fee l ashamed or don't want to be labeled incompetent. Parents a lso m ight not know w h ere to f i nd h elp or fear the st igma associated with services li ke menta l health clinics or homeless shelters. If help is requested, it shou ld be offered in a respectful, caring way.

Although Nguyen did ask for help, her struggles weren't quite over. Fortunately, her growing social network made a diffe r ence.

Social Connections

"Parents need peop le who care about them and their children, who can be good listeners, who they can turn to for well-informed advice and who they can call on for help in solving problems," according to the CSSP. This factor requires quality and available social connections w ith extended fami ly, fr iends, co-workers, community members and service prov iders. Build ing a network and increasing positive support is often a cure for social isolation.

Nguyen's initial connections brought an end to her first husband's abuse When he hurt her again, she returned to the hospita l seek ing he lp. He was arrested when he came to vis it.

Although out of that abusive relationship, Nguyen continued to struggle with her addiction to pain medication, despite spending 90 days in jail. And, despite three years of strong reunifi-

Photo courtesy of Pasqueal Nguyen Pasqueal Nguyen with her current husband Ba ldy

cat ion efforts, social services failed to prov ide her with drug rehab. Her social connections helped change that.

"I had a g r eat re lat io nsh ip with the former foster parents, a great relationship with my (fami ly services) worker," said Nguyen "But then I relapsed again. Unfortunately, at the time I didn't have the strength of not letting people come back into my life who were abusive and toxic to me. I have it now, but not then."

Toward the end of her first reunification efforts, Nguyen began· work ing with Louisiana's Quality Parenting Initiative (QPI). She also talked with the children's' fathers and her foster care connections about rehab. After the birth of her sixth child, Nguyen let them know how and why she needed help.

"I found myse lf trapped in a v icious addiction cycle and realized I could not properly care for my children," said Nguyen. "I made arrangements to temporarily place my chi ldren in more

adequate homes while I worked to better my physical and mental health."

Unfortunately, social services never rece ived th is plan and law enforcement removed her ch ildren . Desp ite these traumatic events, Nguyen found support through her QPI colleagues and entered rehab. Five months later she reunified with her family

'Throughout this period of my life, I saw how it really does take a village to ra ise a family," Nguyen said.

Fol low ing h er f ina l ex it from court, Nguyen met her current husband, Baldy at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting The son and grandson of Vietnamese immigrants, Baldy also previously struggled with substance misuse

Currently, he and Nguyen co-parent seven children and guide other families through recovery. Work i ng with the Ch il dren's Trust Fund Alli ance, Nguyen trains parents and professiona ls in Protective Factors. She also serves as a parent mentor on the Governor's Board for Disability Affairs, and the Extra Mile Parent Advisory Council. • jeremiah Donier serves as a family consultant with more than 15 years of lived expertise in behavioral health child development domestic violence, protective factors, multi-generational adversities and responsible fathering As a volunteer and contracted consultant he serves on dozens of projects to keep children safe, help youth thrive, build strong families and create supportive communities. Donier lives on Whidbey Island with his wife and two children and also works part-time as a library associate In june 2012, Donier was named one the American Bar Association's first Reunification Heroes. In 2019, he was honored with a Casey Excellence for Children Award.