Session 7

COMPASSION IN ACTION

WHAT MOVES US?

Let’s return to the emotion regulation systems. On the one hand, we refresh what was covered at the beginning of the course, and on the other hand, we now highlight the theme from the perspective of motivation. To gain a better understanding of what moves us and how we take action in our daily lives. We are often under the impression that we know why we do what we do. We believe that we are consciously motivated and choose for ourselves which motives move us. We believe that we are “sensible” enough not to be guided by reflexes and emotional reactions. Yet the opposite is true and our motivation is usually unconsciously driven by old brain instincts that take our new brain in tow. What moves us are automatic reactions rather than a conscious response. We now know that mindfulness practice can help us become aware of the autopilot and our tendencies to grasp one and fend off the other. Deeper insight into how our motivation is influenced by the emotion regulation systems can further help us to make conscious and healthier choices.

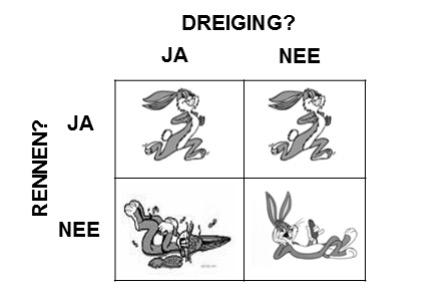

The following decision diagrams can help you recognize which system motivates you in a given situation: the danger system, the hunting system, or the care system.

We already know the first diagram from session 2.

Motivation from the danger system: get out!

Yes No RUN? No Yes

Session 7

When the alarm bell rings, the hare (and the hare in us) quickly runs away, because then he has the least to lose, he plays it safe. If he doesn’t run and the threat turns out to be real, there is a good chance that he will lose a lot, namely his life. If he does run, he may only lose a tasty snack. The danger system therefore quickly trumps the hunting system. In times when we still lived close to nature, this mechanism was indispensable for daily survival and therefore our memory still has a preference for remembering threatening events. It is said that memory is like Velcro for negative events and has a Teflon coating for positive events. Also in case of internal threat (due to a feared thought or unpleasant emotion) the same old brain mechanism can come into play.

Once we are quite shocked in a certain situation, the memory of it acts as a strong motivator to flee in similar situations (or fight or freeze, whichever gives the best chance of salvation). Because of the signals from the danger system, our new brain becomes focused on what is threatening. The preoccupation with what threatens leaves little room for our attention and thoughts to be focused elsewhere. This is characteristic of people who suffer from anxiety and panic disorders. This preoccupation with the threat can spread like an oil slick from remembering and reliving a frightening situation, through the concern for repetition of that situation, to the focus on the accompanying physical sensations, feelings and thoughts, and all possible stimuli that can provoke them. And so fear of fear can arise: the feared expands to more and more signals that can indicate fear. The preoccupation with what threatens also turns inward: how do we escape unpleasant sensations, feelings and thoughts that make us feel threatened? In the case of an external threat, we can literally flee the situation, but in the case of an internal threat, this is not possible. Often we try to do that by looking for distraction, numbing the experience, and also... brood. That is a kind of mental ‘running’, an escape from those ‘life-threatening’ phenomena in our inner world. As long as we worry a lot, we are busy with our head and we don’t have to descend into our body where there is so much nasty to feel. It can also be the aggressive component that dominates: we ‘fight’ against the part of ourselves that makes us feel threatened and bombard ourselves like an inner bully with reproaches and punitive comments. And our behavior is mainly characterized by fearful avoidance or aggressive defense. The danger system can also be the most important motivator in our relationships with others. This may be justified when we are physically threatened, but much more often our danger system only sounds a false alarm because something in the other person – appearance, attitude, tone or use of words – is a trigger for what is stored in our memory. Also, just the image we have of the other person can be the trigger. There is no connecting communication possible, we avoid contact or keep the other person at a distance through unfriendly words or body language.

Session 7

REWARD?

Motivation from the hunting system: hunting?

Motivatie vanuit het jaagsysteem: jagen!

When the coast is clear, the motivation of the hunting system can come to dominate. That happens as soon as we feel a need that wants to be satisfied quickly, whether it’s physical needs for food, sex, and physical comfort, or mental needs for success, wealth, status, or power. We only need to experience the pleasure of good food, a sexual climax, or a feeling of being praised a few times, and we would like more of it. Even though we miss the desired ‘prey’ time and time again, our desire can be so strong that we try again and again to get it. When we’re not hunting, feelings of unfulfillment, dullness, and boredom can set in, or we may be plagued by an unbearable thought that we’ll miss out on the coveted reward if we don’t do anything. The excitement of striving for a reward dispels the feeling of emptiness (which is at least a small immediate reward) and we take the risk of frustration after a failed hunt into the bargain. If it doesn’t work this time, we’ll just try again, until it does. Being rewarded once in a while, in between all the failed attempts, is enough to keep us motivated. There seem to be few disadvantages in the short term, on the contrary: we would rather be excited than bored. And we always have a chance – no matter how small it may be –to suddenly collect that big reward. A single ‘score’ can be enough to maintain an addiction. That’s why gambling, gaming, and expensive stimulants are so addictive. But also working hard to be admired by others or surpassing your colleagues, or constantly looking for new stimuli in the field of relationships can become an addiction. Also then, no connecting communication is possible, as long as we can only see the other person as a rival or someone we need to fulfill our needs. It is not uncommon for the ‘pleasure’ that is being hunted for to be not so very pleasant at all, but it is mainly the disappearance of an unpleasant condition that is sought. Easily accessible substances such as alcohol, tranquilizers, nicotine, weed and all kinds of comfort foods can be allowed into daily life unnoticed to dispel dissatisfaction and other unpleasant feelings and thus lead to unhealthy habits.

Either way, our new brain is unwittingly focused on one theme by the old brain’s drive to hunt: the focus is on the preoccupation with what is desired. This is characteristic of people with addiction problems. The stronger the dependence, the more the thoughts and behaviors are controlled by obtaining the desired substance. There is little room for anything else, unless the hazard system sounds the alarm.

Session 7

When nothing moves us anymore...

The choice to hunt is made easy when the threats are low and the temptations are strong. If there is constant danger and the hunting system is constantly being shouted down by the danger system, this can lead to more and more withdrawal. We eventually lose interest when we forget the taste of the reward. We are no longer motivated by the chance of reward, but by the ‘certainty’ of the lack of it. A prolonged persistence of an overactive danger system and an underactive hunting system is an unhealthy combination that can lead to a severe depressive state, especially when our caring system is also underdeveloped. We feel safer to stay where we are. There is more and more lethargy and inactivity. This is very different from the beneficial calming of the caring system, this is a form of chronic stress. We are no longer motivated to move because we are afraid of what will happen when we do, and we are no longer stimulated by a positive expectation. A withdrawal from social relationships can also go hand in hand with this.

We enter a state of powerlessness, helplessness, and hopelessness that people prone to depression know all too well. When there is no longer a positive expectation of reward in the outside world and the inner world becomes increasingly unpleasant, then it is also worrying here that occupies our new brain. A preoccupation with loss and failure arises. Worrying becomes rumination, a mental rumination, we constantly recall thoughts about what went wrong, is wrong or will go wrong. If we worry about that, it gives us a distraction from feeling the horrible sensations of emptiness and depression. When these come up again and again as soon as we stop worrying for a while, we soon learn to continue with them. And besides, worrying – at least in the initial phase – gives us the idea that we are at least doing something to find a way out. Or, in the case of the more aggressive form of self-criticism and selfreproach, we at least engage our inner bully to hold ourselves accountable and punish. But the longer we continue to worry, without finding a way out, the more hopeless it becomes. If there really is no way out, we keep going around in the same circles. We get stuck in increasingly negative judgments and beliefs, which lead to more depressive feelings, which in turn give rise to even more worrying; And so we get stuck in a vicious circle. In the long run, we can no longer see the negative thoughts about ourselves, others and the world around us, as thoughts that can be exchanged for other thoughts, but they solidify into hard mental constructs that we identify with. We have fallen into a mental prison that keeps us firmly in place. We might call it “stiffening” or “freezing” mentally. In our behavior, we may first show a restless pacing. Until we are exhausted and literally come to a standstill. When we are convinced that change is out of the question, what can motivate us?

Session 7

Motivation from the healthcare system: care!

Motivation from the danger system or the hunting system goes hand in hand with an active pursuit of rapid change. The stress level is relatively high and our body reacts accordingly: the sympathetic nervous system (the neural ‘accelerator’) dominates, more stress hormones are released, breathing becomes faster and shallower, the heart rate and blood pressure increase, the digestive organs receive less blood supply, the muscles more, so that they can perform more. A healthy body can tolerate this extra load for a short period of time, but chronic stress is harmful to health. We are not built to be under constant heightened tension. It is therefore not healthy to be driven by our danger or hunting system for a long time. The care system makes it possible to relax and tune in to our needs for safety, security and social connectedness. The body calms down and is able to recover and strengthen: the parasympathetic nervous system (the neural ‘brake’) predominates, stress hormones decrease, breath becomes slower and deeper, heart rate and blood pressure decrease, and blood flow to the muscles decreases in favor of blood flow to the digestive organs. In mammals that live freely in nature, this happens automatically. Once the danger system is extinguished and the needs for food and sex are satisfied, there is time for lazing around, playful rapprochement, and social bonding.

In humans, this is less obvious. Due to the enormous possibilities of our new brain to see dangers and shortages where there are none, our danger or hunting system unnecessarily works overtime and the stress level remains high. They are shouting out the caring system that could lower our stress levels. The danger system and hunting system are focused on short-term advantage, quick solutions and a cure for a problem by the shortest route: warding off the feared or getting hold of the desired. These are mechanisms that are important for immediate survival. This narrows the focus of our new brain. Our attention and thought processes automatically focus on that which threatens or that which is missing. The care system is focused on care, on recovery, pain relief, promotion of well-being and connection with others.

These changes occur much more slowly and cannot be enforced. They arise ‘automatically’ when they are simply given space. Our new brain adapts to this: our attention opens, our thoughts no longer need to be focused and can flow freely so that there is room for playfulness, wonder, new discoveries and creativity. The focus is not on defensiveness or grasping reactions, but on acceptance and a benevolent letting what comes and go. There can be deeper attunement to the needs of ourselves and others, so that social connection and trust can grow in a secure foundation. We could say that the healthcare system is focused on sustainability and long-term survival. From the point of view of the danger or hunting system, in the short term there are mainly disadvantages of the care system, such as allowing pain and allowing desire to be left unsatisfied.

Session 7

The care system requires acceptance that no quick fixes can be enforced. It requires giving up our need for control and surrendering to processes we cannot control. Before we get to care, we often have to go through discomfort first. Only when the danger and hunting system have raged out, can we fully experience the beneficial tranquility of the care system.

Paradoxically, it can be liberating to realize how the very attempts we make to solve our problems have only led to more problems and we have become stuck. We come to understand that striving for a cure for our problems is itself the biggest problem. Then the way of care opens up. Once we see how we allow ourselves to be motivated by the automatic reactions of grasping, deflecting or judging, then the possibility of freeing ourselves from those ‘demons’ dawns and we can return to the experience of the present moment, where nothing is fixed and everything is in motion. Then we return to the sensation of the ever-changing stream of phenomena; of physical sensations, feelings, and tendencies arising and extinguishing; of thoughts that come and go. Instead of striving for cure and holding on to beliefs about how it can and cannot be achieved, we can consciously choose care. In doing so, we let go of the attachment to quick results and open ourselves with warm, gentle attention to what comes and goes, with the courage to let ourselves be touched, even by the painful. Then we are moved by compassion.

If we don’t do care, there may be a small chance that we won’t be bothered by it because a cure will unexpectedly fall out of the sky. However, if we have already taken all reasonable paths to achieve cure, it is more likely that we are not one of those lucky ones, and then we get the short end of the stick: we get neither cure nor care. We feel alone in our suffering and deprived of the care we need so much when there is no cure. If we do opt for care, we really only have to gain. If the cure does come, care only adds to its success. And if the cure doesn’t come, then at least there is the extenuating circumstance of warm attention and loving care and we can bear the pain that is there more easily. From the point of view of the caring system, the choice for care is therefore self-evident: we have nothing to lose and only to gain.

Session 7

Motivation and freedom of choice

We have previously established that our emotion regulation systems are separate from a moral ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The motivation mechanisms described are also not right or wrong, they are rooted in our old brain and have developed to increase our chance of survival. They therefore all have a right to exist. The question is: do they come into effect in the right situation and do we have any influence on that? The motivation from the caring system is often just as unconscious and automatic as other old brain reactions, even though this system is evolutionarily part of a younger layer than that in which the danger and hunting system are rooted. A desire for peace, security and social connection can motivate us just as much unconsciously as fleeing from what threatens or chasing what is desired does.

Here, too, we can only make a conscious choice when we first notice the tend and befriend reaction, and the desire and phenomena that accompany it. When we recognize the automatic reaction, we can choose whether to go along with it or not and conscious motivation can arise.

Thanks to our new brain functions, we can learn to consciously choose what motivates us and the decision diagrams can help us with that. Thanks to our innate capacity for mindful self-inquiry, which can be further developed with practice, we can observe the processes in our bodies and minds from moment to moment. In this way, we can learn to distinguish between beneficial and harmful reactions and gain more insight into what is the best motivator in a given situation. Sometimes it’s the danger system, sometimes it’s the hunting system, and sometimes it’s the care system. In general, we can say this: since we live in relatively safe societies and the acute dangers of the wilderness are far away, the danger and hunting system no longer have to be as dominant as it was when we were cavemen. Yet they often are, exposing us to unnecessary stress, with all the detrimental consequences for our long-term health and well-being, both for individuals and for society as a whole. In general, there is a greater need for the calming influence of the care system. We might feel freer when we are less controlled by convulsive grasping, deflection, or rumination, which perpetuates chronic stress.

The excessive activation of the danger and hunting system leads to a restless drift in the same patterns over and over again and narrows the field of vision to what threatens and what is missing. The calming influence of the healthcare system can free us from the preoccupations with what is threatening, what is missing or has failed, and opens up the prospect of new possibilities. While the danger and hunting system limit the choice, the care system leads to more freedom of choice.

Session 7

When you encounter motivational and choosing dilemmas in the near future, ask yourself the following questions:

Which emotion regulation system do I tend to choose from?

From the danger, hunting or care system?

And do I want to follow that inclination or could a different choice perhaps be healthier?

Practicing compassion and self-compassion is a conscious choice that can have a major impact on our emotion regulation and what moves us. Not only during formal practice, but – much more importantly – also in our daily lives.

FROM FORMAL TO INFORMAL PRACTICE

Of course, practicing compassion is not just a formal matter, it continues in all facets of our daily lives. The breathing spaces as we learned them in the mindfulness course have a bridging function between formal and informal practice. We may very well enrich them with the practice of loving-kindness and compassion. We can wish for what we need in such a moment of reflection on ourselves. If we are restless, we can wish ourselves calm, if we feel threatened, that can be safety. And again, it’s not about a feel-good remedy. It is not about striving for results, but about the intention of the loving or compassionate desire for ourselves (or someone else who is present at that moment) and the emotional tone that accompanies it. We already knew the breathing space-normal and the breathing spacecoping, now we can practice further to deepen them into breathing space-compassion.

Next, there are numerous opportunities for informal practice to practice the self-transcending emotional qualities. (The log examples in this course may help with that.) Consciously noticing a situation of giving compassion and receiving compassion. A certain mindset or old scheme, noticing the inner bully with compassion. Imagining how our compassionate companion would approach this situation. Reacting to a situation from compassion mode. A moment of equanimity when we become aware that we are being carried away by the reactions of our danger or hunting system in a situation where patience is required. A moment of sympathetic joy when we see someone happy and well. A compassionate wish when we witness emotional pain, in ourselves as much as in others. A wish of loving-kindness to a random passerby on the street, whether it arouses our sympathy or antipathy. Everyone can be included in our practice: those with whom we wait in a line, fellow passengers on the bus, the postman, the cashier, the cows in the meadow, the guard dog in a residential area, the ants on a forest path... etc. We can consciously embed our words and actions in warmth and kindness, and express that with our posture, our smile, our glance, our voice.

Session 7

PRACTICAL ETHICS

Every thought we consciously express, every word, every action has consequences and is therefore in fact an ethical choice. Not in the sense of a normative ‘right or wrong’ or a moral ‘right or wrong’, but in the sense of more or less beneficial. Compassion practice can make us more aware of the consequences of our speech and actions and more sensitive to the ethical dimension of our daily lives. Practical ethics is aimed at having as much beneficial effect as possible and causing as little harm as possible to as many people involved as possible. An understandable reaction to that definition is: ‘That’s no way of doing it, weighing in everything we think, say or do.’ However, this is not a rational assessment. The mind cannot judge what an ounce more or less beneficial effect or a gram more or less damage means. Nor can the mind calculate how far the consequences of a decision extend and how much others will suffer from it. Our minds can help us make ethical decisions, but they need the compass of the intuitive wisdom of our heart. We only develop that compass when we learn to open our hearts and feel the consequences of our decisions. All qualities of compassion are important and we develop them with ongoing practice, formally and informally. Ethics in practice requires sensitivity to pain, our own and that of others, and sensitivity to needs and wants, our own and those of others, and to the emotional messengers who inform us about the quality of the connection with each other. It is difficult, if not impossible, to make ethical decisions when we are controlled by our danger system or our hunting system. That is why people in wars or in a crazy economy often become unscrupulous and do cruel things without even wanting to. Ethical decisions are made from a caring mindset. That is why it is so important to make decisions that can have far-reaching consequences from a place of calmness and to give ourselves time to open our hearts. It can be helpful to take a breather before we take action, before we speak, before we act. We can also deepen the breathing space action with compassion.

THE FACE-MODEL

The American psychologist Christopher Germer uses the so-called FACE model for the application of compassion in daily life.

The four letters F.A.C.E. stand for four specific ingredients that together provide a wise and compassionate way of dealing with something difficult:

F = Feel; feel what’s going on.

A = Accept, acknowledge, allow or affirm; This refers to the acknowledging, permitting aspect of awareness.

C = Compassionately note; witnessing the pain or suffering we experience and being present with compassion and understanding.

E = Expect skillful action; Expect a skillful, wise course of action that results from the first three.

Session 7

Sometimes the E of FACE can manifest itself as a courageous and active step, for example to no longer postpone a difficult conversation. Sometimes, too, the E can mean that we are only aware that there is pain or sadness; We can then understand with serenity that nothing can be changed, but at the same time we do not have to suffer from the adversity.

DISCOVERING COMPASSION IN DAILY LIFE

We do a lot of our activities on autopilot. An exercise in awareness of compassion in daily activities is the following:

Divide a sheet of paper into 3 columns, the left column wide, the middle and right columns narrower. In the left column, write down your daily activities of an average day, just like you did with the exercise ‘energy givers and energy guzzlers’ of the mindfulness course.

Now indicate in the middle column with a number 1-5 for each activity to what extent you do that activity out of kindness/compassion for yourself, where 1 = not at all and 5 = completely yes. Now indicate in the right column with a number 1-5 to what extent you do the activity out of kindness/compassion for another or others.

When you’re done, reflect on the list and notice your reactions.

What does this say about your activities, what does it say about you and about how you stand in daily life? What would you like to wish for yourself and what can you do to bring more kindness/compassion into your daily life? Would it help if your activities changed? Or would it help if your intention, motivation, and attitude changed in what you do? How could you practice that?

EXERCISE: A SIGNALING PLAN

If you have made a signaling plan at the time of the mindfulness basic course, you can use it again. Maybe you don’t have one (anymore) and you think it’s a good idea to make one (again). Take another look at the instructions for the session in question. What are the warning signs that your health is becoming unbalanced and a relapse is imminent?

Session 7

So what could you do to help yourself? And how would you like to adjust this signaling plan when you look at it from your compassionate self (or: your compassionate companion)? Keep in mind that stress and crisis situations mainly trigger our danger system.

However, reacting from there is usually much less helpful than consciously reacting from compassion mode. Are there any warning signs (signals from the inner bully, old unhealthy patterns, schemes) that you would like to add? Are there any physical, emotional, or mental cues, or behaviors that you would like to add, now that you may notice them earlier from the sensitivity of the caring mindset?

Are there any activities, besides the things you usually enjoy or are good at, that you would like to complement out of kindness and caring? Are there any exercises from the mindfulness and now compassion training as well, that you would like to include in the plan, because they could help you in a difficult moment? Are there any treasured objects, texts, or perhaps a compassionate letter that you would like to keep with the plan so that they help you remember what you easily forget in a difficult moment?

EXERCISE COMPASSION FOR THE BODY

“I want to invite you to sit down.... in a tense way. As if you’ve had a terrible day, with a lot of fights, conflicts, stress, and all kinds of nasty messages you’ve received... And maybe that’s true. You can tighten all your facial muscles, your neck, your shoulders, your arms, your stomach and abdominal area are as tight as a house, so that you can hardly breathe. Your glutes, the muscles in your legs, even your feet are as tense as a door. And you realize that this exercise is also going to take a while, so you’re going to be even more cramped, and you’re holding all that tension. Until you remind yourself that it’s okay to be kind and compassionate to yourself. There are all kinds of reasons for this. For example, it turns out that it is not easy to live in a hectic society like ours. An English scientist has found that the average Western person tries to process about as many stimuli in one day as Neanderthals used to do in a year. So there is a huge demand on our brains, while they are barely equipped to process all stimuli. In addition, it turns out to be quite an art to deal with all those basic instinctive emotions and urges that can arise in us. And to live with a body that can show all kinds of limitations... with all kinds of character traits that we usually have not consciously chosen at all.... There are plenty of reasons to have compassion for yourself. Just as all beings want to be happy and free, you can also allow yourself to do the same... and be kind to yourself, and to your own body. Kindness and compassion can also be connected to our bodies. This way you can soften all those tightened muscle groups one by one ... from your head down... up to and including your feet. Maybe you can create a very slight smile at the corners of your mouth ...

Session 7

Maybe the breath can take place again and be soft, and you can let yourself thaw into a posture that feels relaxed, so to speak. Now make contact with a body part that you can easily look at with satisfaction. Because you think this is a beautiful body part, or because it is always a faithful companion in your life who has never let you down... Look at it with kind eyes and attach a wish to it. For example, ‘May you be healthy’, ‘May you be soft or beautiful’ or ‘May you be relaxed’. Just see what is a suitable wish. The wish does not have to be realistic at all, but it does have to express something of kindness towards this body part. To then make contact with one or a few body parts that are very neutral to you, or because you hardly feel them or because they rarely show pain or pleasure. You may also be able to treat this body part with a kind, kind wish. To then think of a body part that you consider difficult to deal with. Maybe because you usually think it’s an ugly body part, maybe because it hurts a lot and is quite vulnerable, maybe because it has let you down in the past or right now by not functioning properly. And then begin by gently repeating a kind or compassionate wish for this troublesome or less-loved part of the body, to the rhythm of the breath or detached from the breath.104 If you find resistance or sadness coming on, you may be able to acknowledge this and move on when there is more space, or possibly return to a part of the body that evokes less turmoil. To finally place the whole body under a shower of warm, kind wishes: ‘May you be at peace’, ‘... experience sufficient rest’, ‘... function well’, ... cooperate in a friendly way’ or any other wish that has a binding effect. There are several healing components to this simple exercise. There is an element of giving or generosity, giving yourself something. And maybe it can also be received, faced, appreciated. Sometimes the first aspect is clearer, sometimes the second. But both components are hidden and coincide in this exercise, which has been done for centuries. It turns out that practicing this meditation regularly as a training for a few minutes is conducive to the ability to concentrate and the inner calming system, and contributes to greater gentleness and tolerance towards ourselves and our environment. So continue for a while with the very light repetition and letting the desire or aspiration flow through you, to the rhythm of the breath, or detached from the breath... until you hear the bell.”

Four Friends of Life’ : Equanimity

Sit comfortably, relaxed, upright. You can close your eyes if you feel comfortable and notice whatever is happening in or to you. And if there is nothing obvious to notice, then you can make contact with the breathing movements, in the abdomen or in the chest....

We are now going to do an exercise in which equanimity or generosity can be developed. To make contact with the atmosphere of equanimity, you can reflect as follows: ‘All people are the heirs of their own actions. I can give people advice, but their well-being depends on their own choices and actions.

Session 7

Everyone is ultimately responsible for the choices he or she makes.’

As with the mildness meditation, you can first think of someone who is quite neutral to you: a vague acquaintance or a casual passerby. You can then gently repeat inwardly a wishful thinking or a reflection, a phrase that expresses or invites an equanimous attitude.

We can give some suggestions. For example, “May you (or you) accept things as they are.” “May you experience calmness and not be distraught by life’s vicissitudes.” “May you be able to reconcile yourself with the comings and goings of things.” ‘I want you to have balance and peace in the face of joy and sorrow.’ Or “May you be carefree.” If the wish or reflection is short, it can flow with the inhalation and exhalation; Otherwise, the wish can be gently repeated at a leisurely pace without coinciding with the breath.

If thoughts or other sensations come up sometimes, you can greet them as an experience in the now. Sometimes the exercise can evoke sadness or indifference, then this can be noticed with recognition and equanimity. If you feel the space for it, you can then gently repeat the reflective phrase or wish, to the rhythm of the breath or separately from it. You can stick to one neutral person or include a few vague acquaintances in the exercise.

To then take a wish or reflection to heart. For example, “May I keep calm in the face of life’s vagaries and unpredictability.” Or, “May I be balanced at the highs and lows of life.” If you know that it is easy to get overly involved in the problems of others, then the following reflection can also be very striking: ‘I can give others advice but not make choices for them.’ Or, “I can only do what I can.”

See what connects well and let the equanimous atmosphere resonate in your heart. The same applies to this exercise: whatever you experience with it, you can acknowledge it as it is and selflessly notice it as an experience or state of mind in the now.

You can now include a close friend in the practice, or someone who means a lot to you in some way. You can put it in front of you in a figurative sense and then attach an equanimous wish to this dear person. For example, “May you accept things as they are.” Or, “May you find inner balance in good times and in bad.” Or any other wish that has or evokes an equanimous atmosphere.

Session 7

You can also, if you wish, include one or more other close friends in the practice, and treat them to an equanimous wish or a balancing reflection. If it is someone who experiences a lot of suffering and about whom you are quite worried or for whom you feel responsible, you can also reflect as follows: “I can care about you but I cannot prevent your suffering.” Or let a wish flow along the lines of ‘I wish you a lot of good and wisdom but can’t make choices for you’. See what fits well.

If you want, you can also include someone you are having difficulty with in the exercise and let them be the subject of an equanimous wish or reflection. For example, a wish such as ‘May you deal wisely with the vicissitudes in life’. If you notice that this is difficult for you, you can also connect the equanimous wish or wish phrase with your own attitude towards it. For example, you can wish yourself ‘May I experience inner balance in the face of criticism’. Or let the following reflection run through your mind: ‘I can’t change others, but I can take care of myself as wisely and compassionately as possible’.

To finally let a wish or reflection flow to the whole world. ‘May all people and animals experience peace in the vulnerability and finiteness of life.’ “May all be carefree and deal in a balanced way with sickness and health, old age and death, good times and bad times, fame and obscurity, happiness and sorrow, wealth and poverty, fame and blame.” ‘May all accept the vicissitudes of life without prejudice’. “May all beings rest in the power of equanimity and generosity.”

You can sit like this for a few more minutes, reflecting on equanimity and generosity in the face of life’s wondrous twists and turns, until you hear the bell.

Session 7

FOR INSPIRATION

If you live in connection with what is, there will come an intelligence in your life that is much bigger Than the knowledge the conscious has collected. If you bring a Yes to the present moment you will get access to the source of true creativity.

Eckhart Tolle

A water bearer has to go to the river every day to get water for his master. On both sides of his body hung a jar on a wooden yoke. One jar was as good as good, flawless and not leaking, the other jar was old and cracked and losing water permanently. At coming home, half of the jar seems to be empty already and that really hurt the old jar.

One day he could not stand it any longer and told the water bearer: “Master I am so ashamed”.

“But why?”, asks the water bearer. “Because I can not stand in the shadow of the other jar. He delivers the full amount of water every day, while I keep losing water on the way.”

“Oh, but I knew this all along”, answers the water bearer. “And yet I have wanted to use you all this time. Did you not notice the beautiful flowers along the road? They only grow on your side. A while ago I planted seeds there, you watered them every day and now I can pick a beautiful bouquet for my master every time.

PRACTICE SUGGESTIONS

FORMAL EXERCISE:

1. Practice the advice for the guided mildness meditation without using the guidance. See which exercises suit you well at the time you want to practice. And in any case, don’t skip yourself as a subject for the kindness practice. Let your experience be your experience, without having to judge. In session 8 we will evaluate the exercise. Choose a time when you are open to practicing. Mention each time you do the exercise on the homework form. Also, write down any specifics so you can talk about them at the next session.

2. Connect regularly with the safe place, your compassionate companion, and/or compassion mode.

3. Work out the Compassion practice in daily life and practice the Signaling Plan when you find the space to do so.

4. Listen to the Compassion for the Body exercise a few times this week.

5. Pay attention to the (parts) of the exercises of session 6 that you haven’t gotten around to yet: The Four Life Friends, Forgiveness and Discovering what contributes to happiness.

6. Follow a mindfulness exercise of your choice as needed, supported by compassion towards yourself (body scan, lying or standing yoga or sitting in attention) from the MBSR/MBCT course

PRACTICE SUGGESTIONS

INFORMAL PRACTICE:

1. Regularly practice the breathing space with compassion at a time of your choosing, while embodying compassion mode. And practice the breathing space compassion – coping and the self-compassion mantra as often as you like when you sense unpleasant feelings or are experiencing stress.

2. Be aware of acting or speaking compassionately on a daily basis while this is taking place. At a later date, fill in the diary ‘Acting/speaking from compassion’ once a day. Use this as an opportunity to become aware of bodily sensations, thoughts, and feelings associated with that one event.

3. Take half an hour once to reflect on the training with mild attention. Do this based on the following themes: - What were your expectations? What did you learn? - What was the price? What did you find difficult in this training? - What can help you keep practicing? - What would you like to say to your fellow students or the supervisor?

4. Reflect a few times on the fact that the compassion training is going to stop. What do you notice in yourself in terms of body signals, thoughts and feelings? How do you deal with this? Pay attention to any avoidance reactions; Notice them with compassionate attention. What would you gain if you did actively think about it?

5. How can you take care of yourself after training? How do you put what you have learned into practice in your daily life?

6. Bring a symbol that expresses what has been most important to you in the training.

6. Zou je iets nieuws of anders kunnen uitproberen

PRACTICE SUGGESTIONS

PRACTICE SHEET – AFTER SESSION 7

Write down each time you practice on the practice sheet and make notes of anything that comes up during practice at home, so we can talk about it next time.

Day/date

_____day

Date:

_____day

Practiced: Formal:. . minutes. Informal:. . minutes.

Formal:__min

Informal:_min.

Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

Comments:

- What exercises did you do? - What were the specifics of the practice?

_____day

Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

_____day Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

_____day Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

_____day Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

_____day Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

_____day Date: Formal:__min

Informal:__min

Additional details

PRACTICE SUGGESTIONS

JOURNAL ACTING AND SPEAKING WITH COMPASSION

Diary

What was the event?

Were you aware of the acting and speaking with compassion while it was taking place?

How did your body feel precisely during this experience?

With what moods and thoughts was this event accompanied?

What’s going on inside you right now?

Example

At work I ran into a colleague who has been home sick a lot lately. Before his illness he bothered me quite a bit. I asked with genuine interest, “How are you?” .

At first there was a desire for revenge, but when I realized this and figured out that he turns out to be quite seriously ill, this changed

First tense, then I smiled, then my body softened

Inner softness and kindness. I thought, ‘I hope he’s recovering and has less pain.’ I was able to connect with him easily and noticed that he was even a little shy towards me. It was the first time I had an open contact with him. “May you be healthy, just as I would like to be healthy.”

Day 1

PRACTICE SUGGESTIONS

Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6