Summer 2023

True Grit

A Story about Courage, Conscientiousness, Endurance and Resilience.

Summer Training: Shooting in the Off Season

Mentorship: Under The Wing

Aaron James

Find your place Outdoors Subscribe: www.huntandfieldmag.com/subscribe

Contents Publisher’s Note: What’s the Why? 5 12 16 6 Contributors 8 Guiding the New Hunter: Where are the Birds Summer Focus: Shooting in the Off Season Summer Focus: Summer Training for Hunt Dogs 20 Training: Foundations for Every Puppy 24 Females in the Field: Field Trial Jitters 28 Females in the Field: The Ladies of Duckhill Kennels

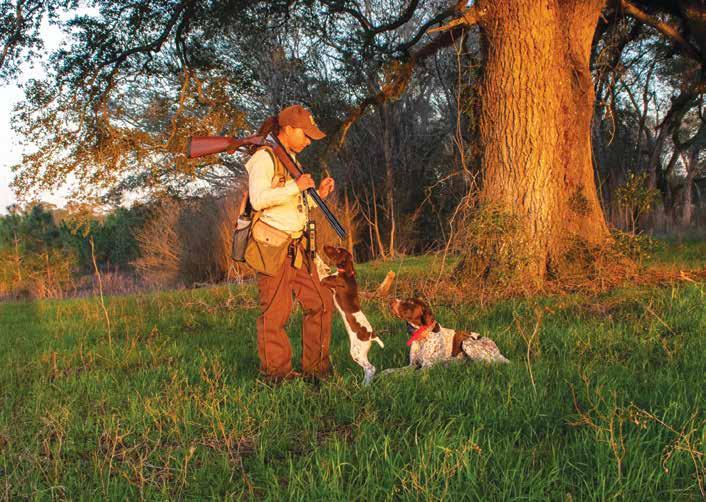

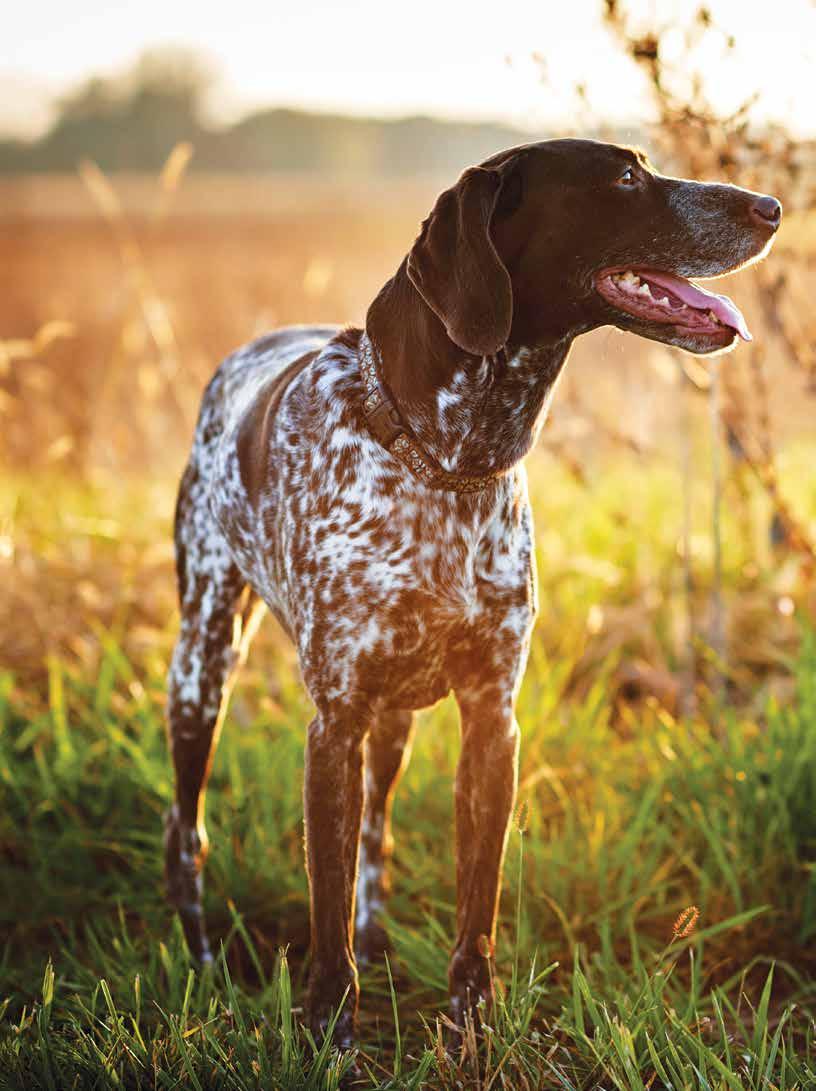

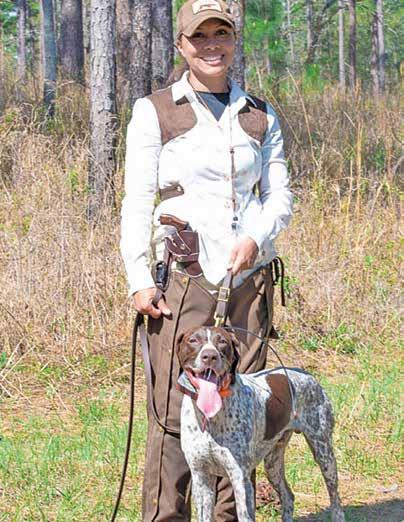

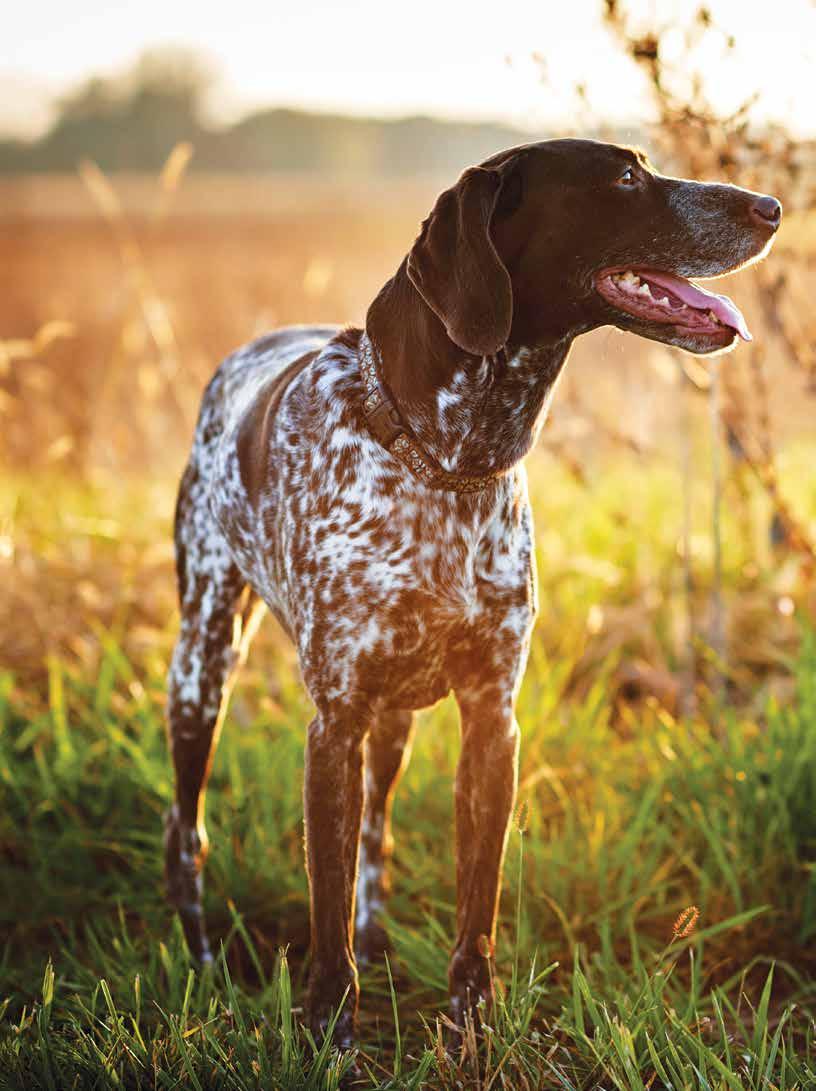

On the Cover:

“Benny,” a German Shorthair Pointer, is owned by Manda and Brian Michaelis. Manda is the first female member of the Georgia Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club. She made history this past March when she competed Benny in their annual Field Trial.

by Brian Michaelis

Feature: What Does it Mean to be a Dogman? 32 36 Feature: Under the Wing 40 Feature: True Grit 44 Art Gallery: American Soil | American Soul

Photo

Summer 2023

Volume 1, Issue 2

Publisher & Editor-In-Chief

Lauren Pigford Abbott

Lauren@huntandfieldmag.com

901- 279- 4634

Assistant Editor & Writer

Alicia Johnson

Office & Accounts Manager

Andrea Winfrey

Advertising & Sponsorships info@huntandfieldmag.com

Contributing Writers & Photographers

Durrell Smith

Josh Brown

Kenton Bryant

Manda Michaelis

Brian Michaelis

Hunt & Field is published four times a year by Ford Abbott Media, LLC. Subscriptions are $45 US for one year, $80 for two years. To subscribe visit www.huntandfieldmag.com/subscribe or email info@huntandfieldmag.com

Mailing address: P.O. Box 594 | Arlington, TN 38002 Office Phone: 901-279-4634

To submit articles, artwork and press releases please email: info@huntandfieldmag.com

We cannot guarantee publication or return of manuscripts or artwork. reproduction of editorial content, photographs or advertising is strictly prohibited without written permission of the publisher, Ford Abbott Media, LLC. ©Ford Abbott Media, LLC www.huntandfieldmag.com

4

& Field

Hunt

What’s my Why?

out your horse stalls while the herd is eating their morning breakfast, I believe it is the right assumption that you are driven every day by the love of animals. And one thing we animal lovers have ingrained in us, regardless of being a dogman or horseman, is how to listen to our intuition and instincts. Our animals teach us how to listen to our gut. Perhaps they train us how to do that so we can better train them.

My “why” is pretty simple, I am first and foremost a horse and dog woman. I have thrived in the outdoors since I was born. When I was too young to ride horses I wondered about open horse pastures. I explored in the woods and sat by ponds scooping minnows out with my tiny hands. The barn dogs would walk with me on my adventures to watch over my steps and keep me company. I connected with nature and with that wild freedom as a young six, seven and eight year old, and I still do in my 40s.

It was another day in my office. I was sorting through articles, photography, checking ad revenue, brainstorming on future issues and setting time aside with my team to help where I could and catch up on their stories, sales, and conversations. I received an email from a business owner that I connected with after publishing our first redesigned and branded Hunt & Field. He wanted to talk over a virtual call. During that virtual call, he encouraged me to find my “why” and to find “what makes Hunt & Field different” from other gun dog and hunting publications. It was advice from a business owner to a business owner and from a creative professional to a creative professional.

In the last six months I have been asked repeatedly as to “why” I wanted to transition the old Field Trial Review into Hunt & Field. My gut response has been, “Because it felt right.” Most people don’t understand that response. Business owners and professionals have thoroughly well thought out strategies behind a rebrand to their business. I am no different. Every decision I make is calculated and with a very specific reason and purpose; however, my decisions are influenced by my first initial gut instinct. And the truth is, “because it felt right” to shake up this publication and reach for new readers and subscribers.

You see, I am an artist, and I have been since I could hold a crayon in my hand. Most of the time I am able to see the finished piece of art in my mind before I sit down to draw. It is the same way with this magazine. I could see a finished product in my hands, and I knew if I could see it, then I could create it. The power of that confidence doesn’t live in this great ego of mine, but in my instincts and intuition.

I feel you, as a reader, probably understand that gut instinct feeling. We are animal lovers at the end of the day. Whether you wake up and feed one dog, or a kennel full of hunting dogs, or you pick

I suppose what makes my “why” different from other publishers and their industry magazines is simple: the experiences I have had throughout my life, in the great outdoors. The experiences I have had are not of the elite. I have never been the best equestrian or even considered trying to train dogs. I have never had the top fancy horses or dogs. I have never won national championships or traveled to the most sought after hunting lodges or destinations in the country or world. I’m like you, just an animal lover that thrives in the outdoors. I can’t afford the top priced horses or dogs. I can’t afford the top branded equipment, gear and attire. I make do, and my love and passion have allowed me to meet the best. At the end of the day, I am not trying to be something or someone I am not. I am trying to be the authentic, down to earth horse woman my mother taught me to be.

The stories in this magazine are told for the everyday outdoorsman and woman. The everyday dogman and woman. The everyday horseman and woman. Perhaps you are like me and have been an animal and outdoors lover since birth. Perhaps your love of horses led you down the path of Field Trials and bird dogs. Perhaps you are a fourth generation upland hunter and your love of the hunt behind your bird dogs led you to following their lead by horseback. Perhaps your dad taught you all about shooting and fishing and your love of the outdoors led you here, wanting to learn more about hunting with dogs and horses.

No matter if you are a fourth generation bird dogger, or a first generation outdoorswoman, the stories we publish in Hunt & Field are for the ordinary novices, amateurs, and outdoor lovers. We are here to help attract you to the outdoors. We are here to help you find your place outdoors. If we can make upland hunting, field trialing, and a life full of bird dogs and horses more attainable and relatable then we are accomplishing our goals and our “why.” I hope you follow our journey, and it helps you thrive outdoors with your dogs or horses, or both.

Lauren Pigford Abbott Publisher & Editor-in-Chief

Hunt & Field 5 Publisher’s Note

Contributors

Alicia

Johnson

Assistant Editor & Writer

Alicia Johnson is a registered nurse turned stay-at-home mom to two wonderful children, Mason and Madison. She and her family live an active lifestyle and can be found outside on most days. In addition to writing, Alicia also enjoys being a personal trainer and helping residents of her community reach their fitness goals.

From an early age, Alicia’s dad had her outdoors educating her on gun safety, teaching her how to shoot, and instilling a love and respect for both hunting and fishing. Through shooting, fishing, and hunting (squirrel, dove, and deer), she and her dad were able to establish a lifelong bond through their shared affinity for the outdoors.

Residing in West Tennessee, outside of Millington Tenn., there are plenty of ways for Alicia to continue this passion for the outdoors with her own children. From shooting, to horseback riding, to just enjoying being in the woods, Alicia strives to infuse in her kids the same outdoor values and heritage her dad passed down to her. In fact, on their very first mother-son deer hunt (also Mason’s first hunt) last November, Mason harvested his first deer, a big-bodied 5pt. buck. Alicia’s daughter, Madison, shares her love of horses as well.

Durrell Smith Writer

& Artist

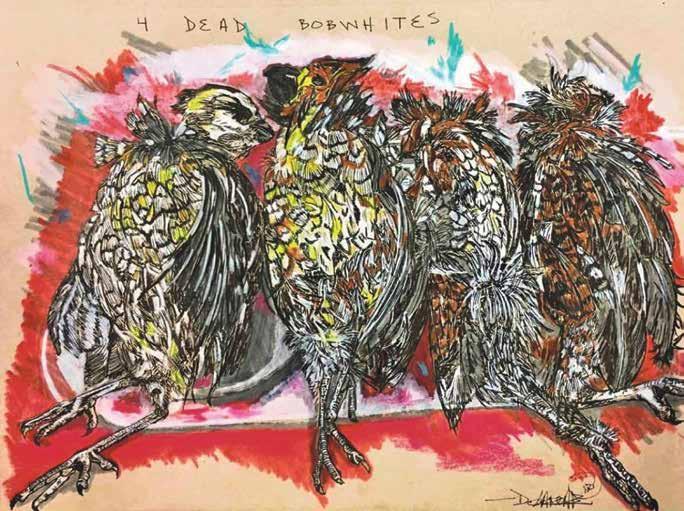

Durrell Smith is a 33 year old Atlanta, Georgia native, visual artist, conservationist, Ambassador for Beretta USA, Orvis Endorsed Wingshooting Guide, bird dog handler/trainer, and podcast host.

While creating compelling abstract assemblage or commissioned india ink and watercolor illustrations based on his field experiences and hunting dogs, he also runs a podcast called The Sporting Life Notebook, along with his nonprofit, the Minority Outdoor Alliance, co-founded with his wife Ashley.

Durrell is also the recipient of the 2021 Orvis Breaking Barriers Award, which honors individuals or organizations going above and beyond to bring new communities into fly fishing or wingshooting. As a first generation hunter, Durrell seeks to learn with and contribute to the active outdoor community by connecting with visionaries within the visual arts and bird dog community who are willing to share stories and knowledge about the various breeds and practices, creating a bridge to welcome aspiring dog men and women to the bird dog community.

Kenton Bryant Writer

Kenton Bryant is an avid bird hunter and field trialer from Nashville, Tennessee. Kenton works as a songwriter in Nashville and had songs recorded by Luke Combs, Kip Moore, Randy Rogers Band, and many more. Aside from field trialing, Kenton enjoys fly fishing, cooking, and spending time with his wife, Rachel, and daughter, Emerson.

6 Hunt & Field

Josh Brown Writer

Josh is a 5th generation hunter, handler and dog trainer from Burlington, North Carolina. He has a rich history on his father and mother’s side of the family in hunting, guiding, training, breeding and raising fine hunting dogs.

Josh has a passion for hunting and the outdoors that is like a fire that burns on the inside of him. He was given his first pair of hunting dogs by his grandfather, Buster, when he was in the 4th grade, and his pack and string of dogs grew from there.

Josh owns and operates P&B Farms and Kennel along with P&B Guide Service. His farm has been in his family for five generations, where they grew tobacco, other crops, along with cows and hogs. When not farming they were hunting and offering hunts for others to come enjoy a day behind birds dogs, a rabbit chase with beagles, or when night fell, treeing coons.

During the spring and summer Josh spends countless hours training dogs for others and training his personal string, preparing them for hunting season. During the fall and winter months Josh guides at his family’s farm, plantations, and hunting preserves.

Josh has two children, Anderson and Addyson, and he is sharing the tradition and rich heritage of hunting and dogs with them both. Hunting, guiding, training and handling dogs is a way of life for Josh and his family.

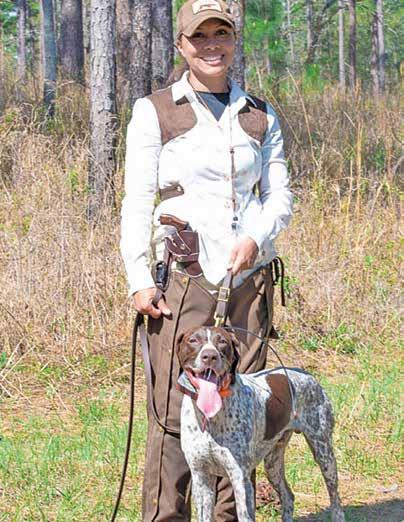

Manda Michaelis Writer

Manda Michaelis lives in the Red Hills of North Florida where she has served her community as a Deputy Sheriff for over 20 years. She is a wife to Deputy Sheriff and Freelance Photographer Brian Michaelis, mother to Caira and Brice and stepmother to Ethan and Sarah. As a first-generation hunter, she is passionate in her pursuit of wild birds and is joined by her two German Shorthair Pointers, Benny and Grit. Through the help of her mentors, she has learned to train and handle her dogs for the hunt as well as for Field Trials.

The purchase of Benny, her now 3-year-old GSP, set her on a course to learn to do with him what he loved most, which is to hunt birds. Her quest for knowledge led her to the doorstep of the legendary Dogmen of South Georgia where she was taken under their wing and taught “The Art of Dog Work.” Working alongside these men, Manda has heard stories and gained firsthand wisdom and insight into what it means to be a dog man or a dog woman.

As a woman who is a wife, mother and someone who has a career outside of the bird dog community she is intentional about meeting the needs of those she loves. They say ingenuity is, the mother of all invention; she often gets creative to meet the training needs of her dogs, as well as much needed time with her family. A self-proclaimed connoisseur of all things Southern, Manda enjoys the things that make the South, The South. From the traditions and customs, land and people, food and drink, history and stories, Manda loves to explore and to share her adventures.

Hunt & Field 7

www.huntandfieldmag.com

Where are the Birds?

A guide for the new upland hunter

Written by Alicia Johnson

Upland, Wingshooting, and Field Trialing, these are the bird dog sports that are often passed through family generations and run through hunters’ blood. The world of bird dogs and their sports can seem so unfamiliar and unattainable for a new enthusiast. But here we explore the regions, the birds, and the dogs that lead the hunt during peak seasons throughout the US.

Quail, pheasant, grouse, chukar, and several other bird species are considered upland game birds. This term refers to non-waterfowl game birds that live above the wetlands in groundcover-rich ecosystems throughout the United States. Traditionally hunted with gun/ bird dogs, upland birds provide one of the most thrilling and enjoyable hunts. Staying on the move with a bird dog, walking or riding through prime habitat, searching for virtually invisible birds is irresistible to many hunters. Found throughout the country, but localized in ideal regions nationwide, it is important to distinguish where these upland game birds’ native habitats and ranges are located in order to know where to pursue them.

The Dusky Grouse is the prominent upland game bird found in this region. New Mexico and Arizona create the southern edge of this bird’s range. Dusky Grouse live in higher elevations than the Ruffed Grouse and can be found in the mixed conifer and aspen forests above 8,500 feet. For traveling hunters, there are numerous destinations in the Southwest that provide a pursuit of these mountain birds, including the North Kaibab mountains and the San Francisco Peaks in Arizona.

Dusky Grouse Season typically runs from September 1stthe first week of November in the Southwest region.

Mearns Quail, Gambel’s Quail, and Scaled Quail are also found in this region. These desert birds offer quail hunters a unique and challenging hunt. Hunters can expect to traverse many miles over rough terrain through thick cedar bushes and native brush, such as catclaw.

Consistently winning more grouse field trials than any other breed, once again the English setter is the most commonly used bird dog to hunt grouse and quail in this region. The Vizsla is also used, as it is a lightly-built, energetic breed that both points and retrieves.

Hunt & Field 9

Northeast:

most common upland species found in this region, al though the American Woodcock calls the Northeast home as well. This region attracts grouse hunters because of bird populations and the tradition that accompanies the hunt. The Gordon Setter is a popular bird dog here. Pheasantsforever.org states, “They are not generally fast but are patient and have very good stamina. They exhibit natural abilities to point and retrieve and are well suited to hunt in adverse weather conditions.”

Maine specifically provides an extensive habitat for quail and grouse with its forestry and healthy timber in dustry. The last two weeks of October is a great time for hunters to plan to be in the woods in Maine. Most of the leaves have made it off the trees and onto the ground at this point, and there is a break between the state’s big game firearm seasons during this time. A liberal bag limit of four grouse per day also attracts hunters to the state.

10 Hunt & Field

South: The main upland game bird in this region is the Bobwhite Quail. With its beloved namesake call, the Bob white is an excellent upland bird to pursue for both the novice and experienced hunter in the South. There is hardly anything more exciting than the explosive flush of a covey of quail. In fact, the thrill of success is what draws most upland bird hunters to pursue them. According to quailforever.org, “Quail hunting is both an American pastime and outdoor tradition which renews its roots every fall as countless individuals and families set out to pursue America’s original game bird.”

Pointing breeds such as the American Brittany and German Shorthaired Pointer (GSP) are common versatile bird dogs used to hunt quail. “The Brittany is a close-working pointing dog with natural hunting and retrieving ability,” as quailfor ever.org states, and the GSP “should range and hunt within a comfortable distance from the hunter. They work well with other dogs in the field and should honor instinctively.” En glish cockers are also finding favor on southeastern US quail plantations as flushing dogs. However, the favorable bird dog athlete leading quail hunts in the south are the English Point ers. Known for having a tremendous amount of speed, they are true competitors. The English Pointer champions over others at Pointing Field Trials.

Great places to hunt quail, pheasant, grouse, chukar, and other upland birds exist all over the country. State Wildlife Agencies can be a plethora of information when it comes to deciding where and what to hunt. With a little effort, research, and travel, a thrilling and successful upland hunt is within reach throughout the fall and winter, so start planning your hunts now.

Hunt & Field 11

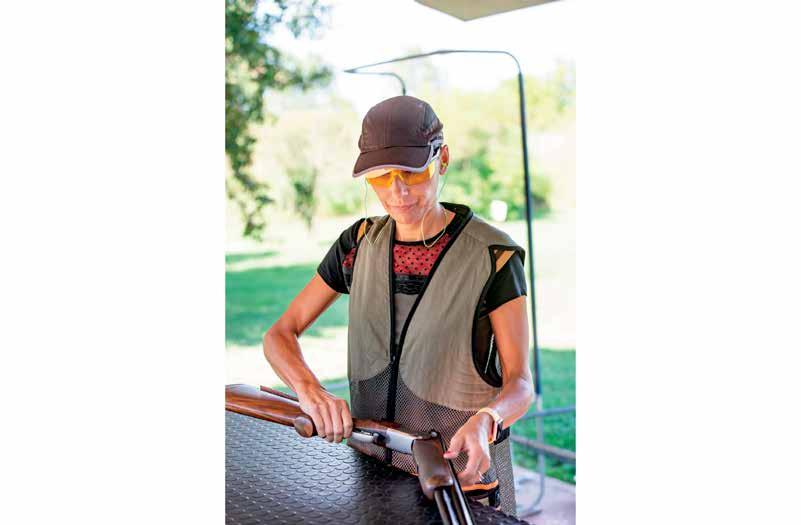

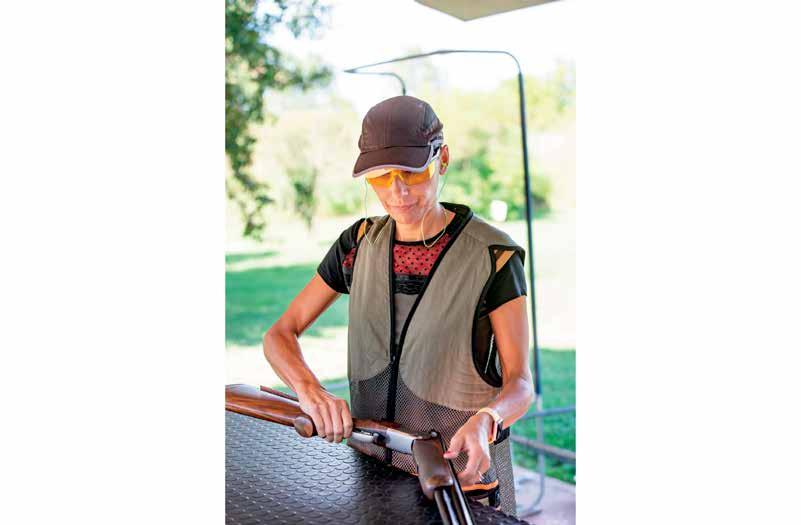

Upland bird hunting is arguably one of the most thrilling types of hunting. Virtually invisible game birds hiding in their cover until they are abruptly flushed by a well-trained bird dog gives the anticipating hunter a jolt of adrenaline, regardless if he or she is a novice or expert wingshooter. Unfortunately, accurate shooting is not like riding a bike- practice is needed to maintain and improve precision. Hunters must keep their shooting skills honed in during the off season if they expect to have successful upland hunts this fall and winter.

If we expect to keep our bird dogs sharp in between seasons, as hunting partners, we should keep ourselves sharp as well. Shooting a gun is a skill that can be improved with practice, and clay pigeon shooting is the best way to get this practice for upland hunters. There are three main types of clay pigeon shooting: trap shooting, skeet shooting, and sporting clays. These kinds of practice shooting can be found at shooting and sporting facilities around the country.

Trap shooting is the most commonly practiced form of clay pigeon shooting in sporting and shooting clubs today. Dating back to the 18th century, this is the original way to practice wing shooting. In trap shooting, the clay pigeons are launched at a consistent angle from a single machine or “trap house” located in front of the line of shooters, lowered into the ground. There are five shooting stations, and the trap shooters are re-

Shooting in the Off Season Sharpening Skills for Upland Success

Written by Alicia Johnson

quired to take five shots at each station before moving right to the next station.

Improvement of fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination, strengthening of the shoulders, arms, and core muscles, and improved balance and coordination are just a few of the benefits of trap shooting this summer. Plus, trap shooting is a fun way to practice as well as socialize with fellow hunters in friendly competition. Considered beginner-friendly, it is a great way to develop and keep shooting skills on point.

Skeet shooting was developed in the 1920’s by a grouse hunter. Differing from trap shooting in the way two clay pigeons are launched, each from a separate house, at a variety of angles and heights, skeet shooting is designed to mimic more precisely the shots upland bird hunters encounter on the hunt. A wider variety of possible hunting scenarios is attainable when shooting skeet rather than trap.

One benefit of skeet shooting is that it can be done relatively inexpensively at home, provided the space, safety, and local regulations allow. There are multiple skeet throwers in a wide price range available on the market, from manually-operated clay throwers, to automatic throwers, to handheld manual throwers. Other benefits include the sharpening of the shooter’s reflexes and increased ability to adapt shots to varying angles and speed.

Shooting sporting clays is the closest thing to an actual hunt

12 Hunt & Field

Summer Focus

Hunt & Field 13

from skeet and trap where the clays are thrown from some what standardized heights, distances, and angles, targets may be thrown from any, yes any, height, distance, speed, or angle on a sporting clay course. Using multiple throwers, the course designers are able to play with scenarios that simulate the actual flushing of upland birds. Different sizes of targets are thrown as well, giving the shooter the most accurate experience of what he or she may encounter on the hunt.

Besides the ability to most accurately simulate an upland bird hunt, perhaps one of the biggest benefits sporting clays offers is

explains on a sporting clay course like Hollywood Farms, the course guide can even call “rooster” or “hen,” and the shooter better be ready to hold for a hen. This development of mental discipline required in upland bird hunting is what sets shooting sporting clays apart from trap or skeet.

According to Chuck, “No matter what skill level you are, beginner to advanced, summer clay shooting will help your shooting skills.” First and foremost, he cautions all hunters and shooters to remember to be safe when handling guns. “Shotguns are wonderful tools and beautiful to look at, but in the

Hunt & Field 15

Summer Focus

Summer Training Tips

Written by Josh Brown

Summertime training… Where do we start? Do we have the time? What do we work on?

I believe that summertime training is vital and important in dogs’ development and readiness for fall and winter hunting.

I know during the summer it is time for family fun, vacations and trips. It is hot and humid most days, and in reality most really don’t feel like fighting the heat. But we must have determination, discipline, sacrifice and commitment. If we don’t have these qualities our dogs will certainly not be all we want them to be. I recently designed a t-shirt that simply said “It’s not how good they are, but it’s how good we want them to be.” So during these summer months what are some basic things we can work on?

All dogs are different and are at different stages in their life and development, so all dogs will be different in what we work on with them. But I believe what we want out of our dogs in the field is what we should work on during the summer. Whether you have a solid, broke dog or a new puppy, keep them working during the summer.

You may say “I don’t have a place or farm to work on.” Well, you can use your yard for the basics such as obedience, whoa training, socialization and recall training. These things do not take much space, just the commitment to do so.

Also our dogs’ health status is just as important, and it’s very easy for our hunting companions to lay around and get fat and lazy. Summer training needs to include the right nutrition for

our dogs, environment for our dogs, and the physical fitness for our dogs. These elements are vital in the summer training process. Just as much as humans need to eat correctly, exercise, and hydrate during hot months, so do our hunting buddies! Providing cut offs and boundaries for your dog is all on you as an owner and trainer.

In the elements of summer training do not overdo it. Take 10 to 15 minutes each day per dog and work on the things you need to work on to make your dog field ready. And if your dog is not physically able to work certain times of day, or at certain temps, do not work them, period. Your dog’s health is of first and foremost importance. So as we are training this summer, make sure to pay close attention to your dog’s actions and physical behavior. You may think 10 to 15 minutes is not a long time, but in my experience, those minutes will bring lasting results in your hunting season and help save your dog’s life in the summer months.

Another good way to keep your dogs in shape and working this summer is through an obstacle course or agility training. This will help your hunting companion mentally and physically. I use this method for exercise and bonding with the dogs. We have to remember our hunting companions are athletes, and summertime training and conditioning will help them get to where they need to be. Heat control is very important as you work during these hot months, so make sure to carry plenty of water.

I personally start early in the morning and take all the dogs

scheduled to work in the morning with me to the field or to the water. This saves time from driving back and forth to the kennel. The dogs I work with in the morning will have had their sessions by midday. Then, I take the dogs scheduled to work in the afternoon out during the late afternoon hours to work them. This allows dogs a good 15 minutes each in a session and allows all dogs to be worked daily.

Summer training is a great way to spend bonding time with your hunting companions. Especially young pups that may be coming up on their first hunting season. You want to make sure you have bonded and socialized with them well before hunt season.

As much as training is important, make sure your dog has fun, especially your pups! You want training to stay positive at all times. As long as things stay positive your dog will look forward to the next step and next session of training.

What you do with your dog now has a direct impact on your dog’s readiness for fall. We cannot wait until a week or a month before hunting season to think about whether our dog will be ready. There is no way to cram all these summer training tips into a week or two. It will not end well, nor will we get the results we need from our hunt dogs.

18 Hunt & Field

Make sure you invest the time into your dog’s training this summer. As we invest this time, make sure you take each dog at the pace they are ready for and need to go. A dog’s progress is not always accomplished at a fast pace. My grandfather used to say, “Slow and steady will get you there.” I can hear him now, “Don’t rush the dog!”

So as we train during this off season, make sure not to rush, and let your dogs develop and come into the dog they were bred to be. If it’s in them it will come out as you work them and put that training time in.

Last but not least, as we are out in the yard, in the fields, or on the water with our dogs, make sure they have been treated with flea and tick prevention, along with any snake aversion. I believe this is vital during these peak summer months. Check your dog daily for fleas and ticks as they come in from training. Be aware of your surroundings, as snakes are also bad during this time of year. If possible, teach your dogs how to avoid snakes. There are many snake aversion clinics that are held during summertime, so that can be good training for you and your dog too.

The best thing you can do this summer is keep your dogs active, happy, and focused! Fall and the cooling temperatures are not that far away.

Hunt & Field 19

The Foundations Every Bird Dog Puppy Needs

Written by Alicia Johnson

Written by Alicia Johnson

Strong drive, athletic, willing to please, loyal, easily trained… these are just a few traits every dogman and woman hopes to see in his or her bird dog. Yes, most of these attributes begin with a breeding program, bloodlines, and good genetics, but how do playful, energetic bird dog puppies transform into magnificent partners? The foundation the puppy receives is key.

Like all puppies, bird dog puppies learn through play from a very young age. The dam has taught her pups social cues and behavioral norms through play and nips early on. Once weaned, the siblings continue to learn dominance, socialization, and manners through play and exploration. Instinctively, its dam and littermates begin building the bird dog pup’s foundation in the form of confidence and respect before the owner even meets it.

Most professional trainers will not accept a puppy until it is 6-7 months or has all of its adult teeth, so there will be a period of several months in which socialization and exposure to different environments should continue. If the puppy is not sent to a professional trainer, it should continue learning through socialization and other experiences as well until it is old enough to begin formal training at home. Still considered puppies until 2 years old, there is plenty of time in these formative years to establish cooperation and trust with the puppy.

Differentiating between breeds, certain bird dogs will need to be exposed to specific things as they grow older and trained differently than other bird dog breeds. For example, a Labrador Retriever needs to learn how to be steady. Essentially, this means the dog will not break, or retrieve, until the hunter sends him. Specifically in bird hunting, being steady is a safety issue. Other dogs may be sent out and other hunters may be shooting, but the retriever has to remain sitting by the hunter, listening and waiting, until he is sent. Not only is breaking an undesirable behavior in a lab, it can be dangerous as well.

To begin teaching the foundation of steadiness (among other things), Heather Vazquez of DuckHill Kennels in Somerville, TN, teaches a Head Start Program for the kennel’s British labrador puppies. This program starts at just eight weeks of age and begins with placeboarding to learn the “sit” command. A placeboard is a tool used in achieving certain training behaviors, such as “sit/stay” and “wait,” going to a specific area on command, recall, and more. It allows appropriate behaviors to be reinforced until a consistent response is reached and helps keep the retriever puppies (and other gun dogs) focused and calm while training.

As far as the setters and pointers go, these dogs will silently search for game by scent. Methodically and systematically hunting until prey is encountered, these canines are expected to go motionless, rather than

chase game, to alert the hunter. As the name suggests, setters will take on a distinct stance, similar to a crouch, or “set” upon locating its quarry. A pointer will freeze in place, straightening its nose, lifting its tail, and staring intently in one direction; almost robotically, it lifts its front foot slightly off the ground and bends in a point. A hunter needs his or her setter or pointer to remain calm, smoothly relocate, and navigate through the woods stealthily as it searches to pick up the scent.

Using ground scent to catch wind of air scent to find birds is the hallmark of hunting with a setter or a pointer; therefore, trainers and handlers specifically work on scent tracking with these two breeds of puppies. To develop and hone in on this skill, trainers will create a scent trail for the puppies to practice with. This can be done by rubbing training scents on a dummy or using the actual bird itself to create a trail. Soaking the bird in water before dragging it on the trail will intensify the scent. Making the trail as pungent as possible encourages the puppy to rely on its nose and build up its confidence. On the hunt, other game, the environment, and humans get mixed in with the scent being tracked, potentially causing confusion for the setter or pointer. However, if a strong foundation in scent tracking is developed as a puppy, the setter and pointer will be able to keep its nose on the desired scent, thus creating a successful hunt.

A flushing dog is a bird dog trained to locate and flush game birds by provoking them into flight so the hunter can take a shot. These dogs differ from setters and pointers in that they do not keep still after locating the bird. They work cover close

to the hunter- within shotgun range. Therefore, beginning to establish range with a flushing breed is an essential component of a solid foundation in a flushing puppy.

Understanding an established range that requires the dog to stay quite close to the handler is paramount with flushers. Trainers must begin drilling puppies with those fundamentals in obedience, “heel,” “place,” “hup,” etc., before range work can be established in flushing breeds. Going hand-in-hand with the obedience training, whistle training is also a precursor to establishing range. To establish this foundation, the handler teaches the flushing puppy a voice command (i.e. “sit”), then overlays the whistle with the voice command, and then finally uses the whistle by itself. Ultimately, the whistle will be used to establish the flusher’s range as an adult dog.

With each of these breeds, it is imperative to remember training should be fun for the pup. Developmental, age-appropriate exercises working towards simple commands are the basis for a strong hunting foundation, regardless of breed. The goal in this stage of training is to ignite the puppy’s instincts it was bred for. The amount of desire in the pup achieved in this early training will better prepare it for the difficult task of finding, retrieving, and flushing birds in the wild. Setting a good foundation with a bird dog puppy will not only expedite the development of reaching its full potential, but it will begin the process of creating an invaluable hunting partner as well.

22 Hunt & Field

Females in the Field

DuckHill Kennels

Two Ladies Leading the Positive Way

Written by Alicia Johnson Photography courtesy of DuckHill Kennels

The two ladies and new owners of DuckHill Kennels in Somerville, Tennessee, Mauri Jourdan and Heather Vazquez, filled some big shoes in January 2023, when they acquired the business from legendary dog trainer and handler, Robert Milner. Having trained and worked under Milner for several years, the transition into co-owning DuckHill was a natural one for these ladies. More than qualified to step up to the challenge, these women of the Gun Dog World are continuing Milner’s tradition and vision of achieving British Labrador excellence through their breeding and training programs.

Only after retiring from the first kennel Robert established in 1972, Wildrose Kennels, was he introduced to a game-changing, innovative way of training his labs: positive training. Robert was so enticed by these new and exciting positive methods that he felt compelled to come out of retirement and try these techniques himself; he founded DuckHill Kennels in 2007 for that sole purpose. Realizing how successful these positive methods were, Robert recruited an industrious team to pass his knowledge, drills, and methods onto as he approached his second retirement from the dog training industry. His work is still carried on today.

24 Hunt & Field

Mauri, Heather, and their two other trainers, Cayley Garland and Courtney Baker (also the kennel’s photographer), work together in a joint effort to continue Robert’s training techniques daily at DuckHill. It is an all positive training facility: no coercion, no force. Positive training is a part of operant conditioning, which means the dog learns to associate its behavior with positive actions. With this type of training, dogs increase the frequency of behaviors with pleasant consequences (a treat, pat on the head, praise from the trainer) and decrease the frequency of behaviors with negative consequences (no treat, no pat or rub, no praise).

In contrast to most kennels, no e-collars (electric collars) are used. “We use the dog’s natural instincts, rather than force, to train,” Mauri states. The ladies of DuckHill believe the e-collar is simply not needed. “These dogs have the natural instinct to retrieve- it’s what they were bred to do. There’s no reason to force them. I feel like the e-collar takes the fun away for the dog. He already knows what to do- we just have to positively reinforce it,” Mauri explains.

Traveling to England in 1983 in search of examples of original English labs, Robert imported the first British Labradors, whose pedigrees trace back to 1837 with the Duke of Buccleuch (one of the last St. John’s Water Dogs that became the foundation of the British lab breed), to Wildrose. He was intrigued by their great hunting initiative and trainability. The breeding program continues today with these bloodlines and focuses on breeding for good drive, trainability, calm temperament, natural delivery to hand, and, for DuckHill canoe labs, compactness.

A canoe lab is one bred to be a smaller size, typically 35-50 pounds. As Mauri explains, this means a smaller lab with all the same qualities you would expect to find in a British lab that can jump in and out of a canoe without risk of capsizing it. Also due to their smaller size, less water is brought back into the canoe on the return.

Besides breeding, DuckHill Kennels also offers a Head Start program for their puppies, Search and Rescue training, Good K-9 Citizen program, and, of course, the Gun Dog program.

Hunt & Field 25

The facility includes an agility obstacle course and a recreated disaster scene, complete with tunnels for the handlers to hide in, to aid in the Search and Rescue training.

Heather mostly works with the puppies and outside client dogs. DuckHill puppies do not leave the kennel until they are 10-12 weeks old. This allows the dam to wean them on her own schedule and decreases separation anxiety. At 8 weeks DuckHill puppies begin formal training. Heather uses clicker training and placeboarding to teach them to sit. This is an important foundational skill as they begin drills and methods in steadiness, an attribute that is imperative in the blind. Duck dogs must be reliably steady as they are asked to sit for long periods of time while other dogs are worked, calls are blown, shots are fired, and ducks are dropped.

The puppies are worked in ten minute increments about three times a week, and progress notes are taken. Client dogs are worked with every day. With both, consistency is key, and Heather always ends on a positive note. She says, “You can never have too much repetition in training.” In fact, 150 successful repetitions are needed for a skill like deliver-to-hand to be considered concrete.

Although it’s not duck season, “Training-wise, there is no off season,” Mauri states. “These dogs are athletes, and it’s similar to a marathoner who

really never stops running,” she explains. Although they can’t work as hard with the intense southern heat and humidity, the DuckHill trainers continue to drill year-round. Building muscle memory is just one specific skill that can be strengthened in the summer months.

Another reason DuckHill Kennels stands out in the Gun and Duck Dog industry is these ladies do not market “finished” gun dogs. Instead, the goal of the Gun Dog Program is to give the dogs the foundation and skills they need to enable them to go back to their owner (or to their new home) and begin the journey of working together. Once trust is established with the owner, the process of working towards a truly finished gun dog can begin. DuckHill wants the average novice trainer to be able to successfully work with his or her dog using the gentle positive training methods the dog has already become accustomed to while at the kennel.

Building on this continuation of training, the women of DuckHill believe in sharing their training methods with dog owners and other trainers as well. Mauri states, “We aren’t training to be the best; we’re training to be our personal best.” Mauri, Heather, Cayley, and Courtney believe that sharing training “secrets” doesn’t take away their strengths as trainers. “The more positive dog trainers we have out there, the better these dogs’ lives are,” Mauri adds.

Hunt & Field 27

Field Trial Jitters

Written by Manda Michaelis

Photography by Brian Michaelis

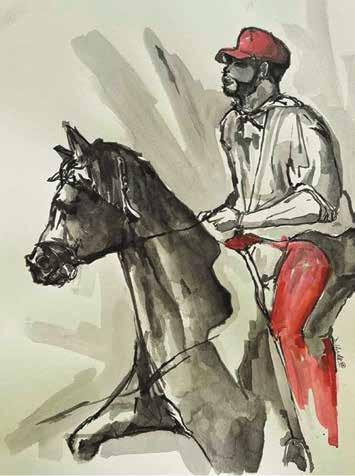

It was the much anticipated first Monday of the month of March for the members and fans of the Georgia Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club. It was our annual Field Trial, and I was sitting on the back of a deep brown Tennessee Walker. I felt bad because I did not know his name, having borrowed him from a friend who promised he would have something for me that day, and true to his word, the horse was delivered to me just prior to the start of our Field Trial. I am certain the scout told me his name when he handed me the reins, but my mind was too preoccupied with the excitement of what was ahead, and I was busy getting my own dogs settled inside their boxes on the wagon that I did not listen, so I just called him “Horse.”

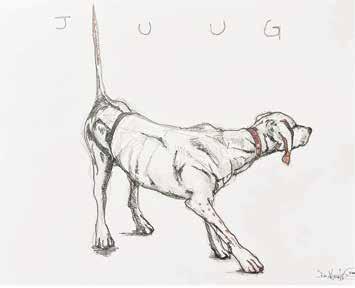

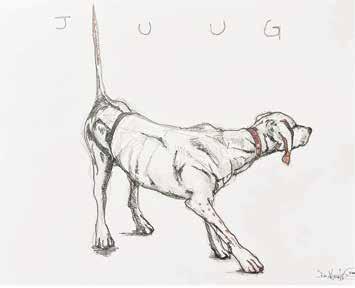

I was riding alongside Durrell Smith and his horse, Bossman, when the elephant in the room, the question of the hour

came up. Would I run Benny, my German Shorthair Pointer, in the Trial if Durrell pulled his dog, Jughead, due to an injury to his paw just two days prior? I had been asked multiple times leading up to this day if I would run him if the opportunity presented itself, and I always said, “No, I just want to watch.” Having seen last year’s Field Trial from the back of a Mule Wagon I did not feel I knew the tricks of the trade, so I did not feel confident; anyway, club rules dictate that a new member must sit out his or her first year. I was new, having only been a member since October. However, if someone must drop out a new member can take his or her place, and this looked to be the situation I had found myself in.

Unbeknownst to Durrell, I had already decided that morning that if he had to scratch Jug I would step in having been convinced by my husband that the experience would be “great”

28 Hunt & Field Females in the Field

for both Benny and I. This did not mean that I did not believe that there was not a chance for an epic disaster, it just meant that I was willing to take that chance to learn what I could from the experience. I told Durrell I would do it, and he immediately agreed to be my Scout, making me feel a little better that the situation would not get too out of hand.

It was a hot day in Thomasville, Georgia; too hot for it to be just the beginning of March and not ideal in the least for Benny, who easily gets warm and had been riding in the wagon all morning. I was filled with so much apprehension, I could feel my heart pounding. My hands were shaking, and dang it if I did not have the sudden need to use the restroom. The woods would have to do. I hate feeling like I am unprepared. I am a person who hates to fail, so to make myself feel better I like to over prepare. The truth is, I was ready. Benny and I had put the

work in, we had hunted all season and gone to the club training days; he looked good. On several of those training days he had more finds than his bracemate, and I knew that he could do it. There really was not anything more to do than to jump on the back of “Horse” and do what we had been training for. After making myself more comfortable, I pulled Benny out to water him while Durrell let our mentor and club president, Neal Carter Jr, know that he would not be running Jug, and I would be filling in.

Neal was pleased to hear that I was running Benny. He had a big ole grin on his sweet old face, and I was feeling like I was about to vomit. Neal proudly announced to everyone that the first woman in the club and in the history of the Field Trial, was about to run a dog. You would have thought by then I would be comfortable with all eyes being on me because I am

always the one and only woman, but this time I was breaking new ground for real. I heard cheers and received well wishes and encouragement from many of the members and onlookers. There were also those that regarded me with curiosity, and others, I could tell, thought Neal had lost his mind. Nevertheless, I did not have time to ponder who was for me or against me because it was go time.

As my trembling hands put my tracking collar on Benny, I could hear Neal whispering to me softly, “Just do it like we

always do. There is no one else here but me and you. Listen for my voice.” I looked into his eyes and felt a slight settling of my nerves. “I can do this.” I got on “Horse,” and Neal was leading Benny to the front. I handed my handset over to the Judge and paused to look at the sight of my beloved mentor carefully getting Benny settled out in front of my horse for me. When he looked up we locked eyes, and he gave me a slight head nod, his eyes saying, “You can do this.” We were given the green light to go, and my bracemate and I blew our whistles simultaneously, sending both of our dogs flying through the woods. Neither needed encouragement, and certainly not Benny, who had been whining and eager to go all morning.

Thirty minutes! Thirty minutes was how long we had to go, and I prayed Benny could hang in there in that heat. The last thing I wanted was to be told by a judge to pick my dog up. I was so nervous. I was in a place I love, doing what I love, and I was so anxious I could not relax enough to enjoy it. Benny was running hard, and I could already tell he was hot. Rookie move on my part, I was riding hard right behind him. I heard Neal call out to me “Manda, slow down let your dog work, you are pushing both dogs.” I must be honest, I was not overly concerned about my bracemate who did not look all that thrilled to be paired with me in the first place, but Neal wanted me to slow down, so slow down I did. I paused to water Benny, who appreciated the break under Neals watchful eye. “That’s enough,” he said, “Don’t give him too much.” I jumped back on “Horse” and sent Benny back out. I caught a glimpse of Durrell and Bossman way out in the woods like a pair of ghosts parallel to us. Not very noticeable like a good scout, but in place just in case.

I thought I saw Benny getting “birdie,” and in hindsight, I knew he was. He had caught a scent and was trying to work it out in all that heat. My bracemate saw it too. Benny was circling around in his “birdie trot,” tail looking like a little propeller. If I knew then what I know now, this may be a different story, but we will chalk this up to lessons learned. My bracemate went to laying on that whistle, blowing it for all it

was worth: hacking, singing, calling out, you name it. Benny looked so confused. My lack of experience was working against me because I did not even realize my dog was being “stolen” from me. Benny moved on, and I doubted myself. I doubted what I saw, and I doubted my dog, forgetting Neal’s advice of, “Always trust your dog,” or “Know your dog.”

Benny and I went on to finish the brace with no finds. You would think I would have felt like I failed, but I did not. My bracemate had no finds either; I think he may have been too worried about being beat by a girl that he forgot to run his own race. I was satisfied that we finished and not told to pick up. I was proud of myself for trying and proud of Benny for finishing. We took with us the experience and the lessons; next time we will be better. That will be the last time my dog is taken from me. I am not bitter, that is part of it, and I am smarter and more educated for having been there and done it. There is always next year, and the year after, and one year, this girl seeks to win and be the first woman to win, not just compete. No matter what, my first-year jitters are behind me, and with every year that passes, I hope to be as cool and collected as my mentors who know that it is not just about finds, but also about showmanship. They strike a nice balance of sitting back, enjoying the ride, and knowing when it is time to go to work. It is all class with those two, and I am blessed to have them.

Hunt & Field Hunt & Field 31

What Does it Mean to be a Dogman?

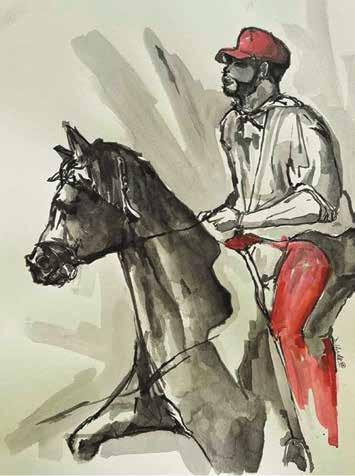

Written by Durrell Smith

Morton

Written by Durrell Smith

Morton

32 Hunt &

Field

Historic Photography Courtesy of Billy

(*read in your best Thor voice*).

In some stories, there are rumors in the South of men who find their peace and solace in the early, waking hours of the day, greeted with the chops, barks, and howls of pointers and setters and the quieter stomp of a Tennessee Walking Horse’s hoof pounding the stable stall dirt. They reply to each by name, with a kind heart and a giving hand and a spirit filled with an ever-deepening kind of gratitude. There comes with it a sad song of a dying lore. The men and women who live the lifestyle know that there is no guarantee that Bob White will be tomorrow morning’s opening act, and so they live for today, following the whistle, always present for the moment. Being a Dogman is inherent to a life of stewardship and care for the land, the trees, the clay, and the critters that follow the annual fires. Singing through the longleaf for the Dogman is Worship in a cult of fire.

I’m chasing the Dogman’s song, living to traverse the sanctuaries of South Georgia’s Red Hills and Alabama’s Black Belt. We, as Dogmen, are called to be disciples of The Way and The Art of handling a class bird dog and unbeknownst to me, through the definition of my own journey I would find myself among a collective group of guys and gals who also carry

the mantle, spreading the Good News and magic of another big move, great cast, or jaw-dropping find, way out on a limb and seemingly impossible. Wild bobwhite quail are known to hold even the greatest of bird dogs accountable for the working relationship between their nose and brain.

Dogmen are masters not only of the kennel but horsemanship as well. Their craft has always been the story of their lives. It was my adoption into the fold that revealed true meaning for my own life’s work, continuing to develop a voice to my own gospel, pulling from the wisdom of men who came before me and did it way better, under greater odds. This wisdom has since exposed me to life- giving truths that have brought me much closer to God. There’s nothing but time and space in the pineywoods, time to reflect on that which is bigger than any of us.

Becoming a Dogman is a somatic and ethereal journey and brings us closer to our higher selves. Watch a dog on point and it then becomes evident that there are universal powers supremely at play. Confirmation that The Spirit lives in us, enlivens the world around us, and rests between the dog and the birds, and you’d be best to learn how to walk the aisle, flushing and disrupting the sanctity of cover, and at the same time, closing the circle, bringing man, dog, horse and bird to communion.

Becoming a dogman declares a commitment to truly molding and developing class bird dogs and seeing them as works

Hunt & Field 33

There is a great Gospel that we profess as men of the dog

of Art, performative by way of showmanship. A dogman might seek some finality in his work, as dogs matriculate through their program, but we learn through this process of our own imperfection. There are years of hardship and heartbreak, and sometimes the best of our strings are gone too soon, yet their performances live forever, buried within the caverns of our hearts. The path to becoming a dogman later informs an existential curiosity born of innate passion. Every day, we answer our desire for more. The dog over The next Hill and through The pines A pointed metaphor. These are just a few of the Dogmen who continue to color my story:

WILLIE & BIG C

And I walked the land with these old men, cutting dogs loose from my cable gang one by one, bird by bird, those early August and September mornings a gathering of sculptors, artists of a time tested trade.

On those mornings Willie Sims laughed dastardly because he knows what he got. On those mornings, our curriculum was determined for the heart, not just for A bird dog but for The men and women themselves. If there ever was a school for dogmen, ain’t not one gon’ graduate because there’s always something to do, something to learn and it’s a year round job. But never have I found it to be thankless.

There is a proud feeling when you can swing your horse sideways and show a dog right and proper. To feel it in your spirit when the dog is about to make that big cast is unforgettable. So I guess being a dogman leans on trusting your intuition and the work that should’ve been done, a great deal of the work is contingent on trust. “Trust the dog, be his friend first,” is what Big C told me about my Jughead

34 Hunt & Field

dog when he presented him to me in the back of that old horse trailer. And till this day, I can argue that was the most profound piece of wisdom I took from him, simple enough and even more effective in practice.

DAVID

Being a dogman is being self aware and still stepping up to the stage and being open to what variables may not be in your control, and adapting to change, and knowing the changes in the dog’s patterns. I spoke to David Johnson once about some of his fondest memories during The heyday of the American field, and what he told me I found awe-inspiring. As a scout for legendary hall of fame bird dogs and being elected to the Hall of Fame this year, David knows the habits, traits, physical and mental characteristics of his dogs so intimately that he could track a dog that got off course through paw prints in the dirt and mud. That takes time, but most importantly, a hand that molds that dog from the time it’s a puppy until the day it’s called finished.

BILLY & MAN

I spoke with Billy Morton of the Alabama black belt and he spoke about his dear friend Ben “Man” Rand, one of the greatest dogmen of all time, WHO scouted for Billy Morton. Both historic figures in this community, but my conversation with Billy Morton years back call to answer some of what it means to answer such a large question. Dogmen like “Man” came

real clever at an early age, skipping school out the schoolhouse window and hopping on the dog wagon with Mr. Holloway, who trained bird dogs for Sedgefields Plantation. What was it that made him so special? Mr. Billy Morton replied “patience.” He trained young dogs as if they were all in his classroom where no pup was left behind. No one progressed until everyone was up to speed. He worked those young puppies together and created a sense of camaraderie with them and them amongst each other. He was different from most because he cared to take his time and “Man,” like David, was a good horseman and alternatively, a good houndsman as well.

Hunt & Field 35

Under the Wing

Written by Kenton Bryant

No one is born a dog man.

The journey down the path that is bird dogs, horses, and field trials is well-traveled from those that came before us and was well-worn by those that came before them. From mentor to mentee, our sport is passed down much like a treasured heirloom. We carefully hand off traditions, trade secrets, and “ the way things are done” so that everything we hold dear is able to be gifted to the next generation that shows up with an affinity for the poetry in motion that is birddogs and horseback field trialing.

My journey was like many. My Father had a penchant for Ruger red label shotguns, english setters, and pointers. That meant I spent many crisp winter mornings in Kentucky shuffling behind my father, in coveralls two-sizes too big, antici-

Hunt & Field 37

pating the moment that the racing white blip on the edge-row horizon froze like a statue. Those moments undoubtedly set the course for my life-long addiction to birddogs. I’ve been blessed to have gained many mentors over the years that played various roles in furthering my pursuit in birddogs, horses, and field trials. Each one of them adding a new and exciting color to the palette that is bird dog knowledge.

I remember the first time hearing about field trials. It sounded like something from a novel, and in many ways, it is. I had spent some time working some gun dogs with my friend, George Hickox, and he convinced me there was more to all of it. A lot more. Unveiling all of the unknown began with George offering a place to lay my head and a horse to ride at his summer camp in Mott, North Dakota. I didn’t know it at the time, but that trip to the prairie with my trial prospects kicked open the door to the world of horses, field trialing, field trial dogs, and many people I now call friends and mentors. That all began because one person took the time to take me “Under The Wing.” That is what a great mentor does. They guide, direct, and shorten the learning curve. George did just that for me.

Anyone that’s spent much time training trial dogs will gladly tell you all of the places that they’ve messed up. That’s part of it! I distinctly remember calling my friend, Sean Derrig, of Erin Kennels at the end of last year with a plight for help, and quick! I was very proud of my all-age caliber setter derby out of Erin’s Wild Atlantic Way that I had raised from a pup, but as Sean later put it, “He is a whole lot of dog for your first trial dog.”

My setter derby, Rip, had won an open horseback derby stake that fall, but during many trials he didn’t mind going rogue and getting lost out the front and wasn’t finding birds in trials like he had done in times past. I knew I needed help! Sean graciously invited me to come down to his Covey Pointe Plantation to diagnose my mishaps and put my setter and I back on the right track. Within five minutes, Sean pointed out that I had little control over my dog, and

38 Hunt & Field

he was mechanical around his birds. Sean isn’t one to sugar coat things, but he’s one of the best mentors and teachers if you can take the heat! After he pointed out where I went wrong, we went to mending the broken links in the chain. Sean showed me how to let the dog run free, but with a handle. My dog went from running wild, for himself, to running deep, with a handle and purpose. I quickly learned from Sean that this is the key to a top-tier, all-age dog.

Sean also pointed out the lack of bird finding was something of my doing. My setter was dead broke, but lacked the “fire in the belly” that I had seen before. This is where experience and mentorship come in very handy. By myself, I probably would’ve trudged along, keeping him dead broke and accepted the sub-par performance as the new norm. Sean did the opposite. He took my big setter out to the quail recall pen, let 50 birds loose, and allowed that big white and black setter to bump and chase as many birds as he wanted for an hour. It was amazing to see the dog remember THIS IS FUN! I had spent so much time worrying about bird manners that I forgot to remember the dog needs to be enjoying themselves to give you 100%. There’s no doubt if I didn’t have that guiding hand, I would’ve probably lost out on a nice trial dog. Fortunately, I didn’t. We came back from that trip and won two more horseback derby stakes and placed in both shooting dog and all age horseback

stakes this spring.

I recently asked my friend, Tommy Rice Jr., pro trainer and winner of the 2020 National Shooting Dog Championship, about his journey, being “under the wing” of others, and his thoughts on mentorship.

“A good mentor is someone who will willingly give honest advice when asked, and someone who does what they give advice on in the field. I was blessed to have many mentors and be around the best in the game. I’ve been around birddogs all my life with my dad being a dog trainer for a south Georgia plantation. So, I learned the foundation there. With trialing, I worked for Jamie Daniels and was surrounded by the who’s who of field trialing. I was able to work alongside them, and I made it a point to watch how all of those guys did things, and when they did things in both training and handling. I tried it all, but I took things that worked for me and my style.”

The old saying goes,

“There are a million ways to skin a cat.”

That is true as ever when it comes to training bird dogs, horses, and running field trials. The one common thread we have in this sport is that it takes a mentor passing down the tradition, experience, and “the way things are done” to turn new, aspiring dog trainers and field trialers into dog men and women.

Hunt & Field 39

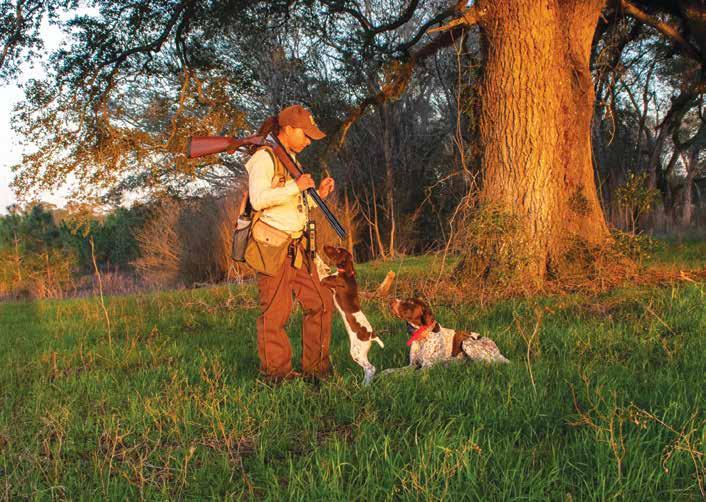

We were huddled together on the floor of Bradfordville Animal Hospital Room three. Our grief was blinding, choking out any other emotion as well as the air we were trying to breathe. The moment was surreal as we watched Huck gently patrol the room, sniffing and scouting all the cracks and corners then coming back to us for chin scratches and rubs. We could not believe that in a matter of minutes we were going to have to say goodbye to this very much alive and very muchloved little guy whom we had so many plans and dreams for. Twenty-two weeks, one hundred and fifty-four days- that is how long we had with him before we learned of a birth defect that could not be remedied without major emergency surgery that may or may not give us the results we were hoping for. The only thing guaranteed were some long, dark days ahead.

Huck was 6 months old and was looking at us with piercing green eyes that had a depth of understanding far beyond his 6 months. The expression on his face communicated complete love and trust. I am not one that likes to humanize a dog, but I

know that he knew something was up, and I know that despite him clearly not feeling well, he was content because his family was with him and therefore, everything must be all right. So, he continued to go about his business checking things out in the room, frequently returning to us for “loves.”

Grit is a concept I had been toying with and exploring for months. It has been a common theme that, like it or not, my husband, Brian, and I had been forced to come back to repeatedly in our work and in our marriage. Grit was something that we were choosing at that moment on the floor as we knew that our hearts were about to break into more pieces than we could gather up afterwards, and grit helped us keep our commitment to be there for Huck and for each other. Grit gave us the strength and courage to give him the send-off he deserved and to stay present in a moment when two people who are the biggest avoiders of emotional pain would have normally opted to avoid. Our grit is God- given and has been honed through a life of service to others, and that day it served us well.

Grit is defined as courage and resolve, strength of charac-

40 Hunt & Field

ter; the characteristics of grit are courage, conscientiousness, endurance and resilience. The morning after our goodbye to Huck, Brian and I were sitting at our dining room table trying to unpack our emotions in the healthiest way possible and the topic of grit came up, as it always is a common thread in our lives. We explored and honored the grit we managed to display at the animal hospital and then realized all the grit that Huck had displayed over his short life. We now knew that due to the medical issues he had he could not have felt well much of the time, yet he was always ready to go wherever the family was going, always trying to be the first one at the door or out of the tailgate to get into the field. Huck would leap and bound, running through the woods in a way that I never once suspect-

True Grit

Written by Manda Michaelis

ed he might be in pain. He loved his birds, intensely pointing at them, hardly able to stand in one place. He retrieved with deliberate intensity and joy, as if he could not say no and was often found carrying around a random sock or shoe. Huck had exceeded all our training goals for his age, and we had big plans for him. We realized that this must have taken grit for him.

Isn’t this what we want from all our bird dogs? Haven’t we all had the experience on a hunt where we call our dog back to us only to discover they have been hurt, are bleeding or are limping, and all they want is to get back out there? We talk about the dog with no quit in them; that no matter how tired or how hurt they are, they are laser- focused on the task ahead and want nothing more than to

Hunt & Field 41

Photography by Brian Michaelis

“Grit is defined as courage and resolve, strength of character; the characteristics of grit are courage, conscientiousness, endurance and resilience.”

42 Hunt & Field

complete it. We as hunters/handlers want to be the ones to call our dogs off, letting them know when the job is complete, not have them quit on us. We want a courageous, conscientious, resilient dog who endures.

Huck was all these things, and coincidentally, he brought out another deeper level of grit in us. We have always known that we could do the hard things, our jobs require a tremendous amount of courage and ability to stand strong and firm in the face of danger and pain, and our marriage has required us to dig deep and to choose who and what we value the most as the world tends to throw so much unnecessary pain and strife at us. Love and pain go hand-in- hand, anyone who has spent any time on this earth knows this, and it is impossible to have one without the other. As we sat at our table talking and sometimes crying, we shared with each other the joy he brought and how much we loved our lives with both of our bird dogs. We shared the lessons we have learned and surprisingly, a desire to try it again. As I have already explained, we are massive avoiders of emotional pain, always preferring physical to emotional, and even though we have had a deposit on another dog for months, I was not sure what we would do when that time came. Yet we agreed that we wanted to try again, fully knowing that with more dogs there are more goodbyes.

Prior to the passing of our Huck, I came to my husband and asked him what he thought about the name “Grit” for our next pup. I saw his eyes light up. He grinned, gave a nod of ap-

proval, and said, “You have a way of coming up with names that are relevant to me unbeknownst to you.” As a boy, my husband grew up idolizing John Wayne. He has always fancied himself a man’s man and loved the movie True Grit, even though I have never seen it. The idea of naming a dog Grit was of great interest to him, though the meaning of the name came from a variety of places for the both of us. It is the grit that he and I display everyday as we serve the people in our community and each other; it is the grit that Huck displayed until his last breath, and it is the well-loved movie that defined, for my husband as a youth, what it means to be a man.

Huck’s name came from my husband’s love of Huckleberry Bear Claws found at the Polebridge Mercantile in Polebridge, Montana. It also came from a mutual love of the movie Tombstone and Doc Holiday’s character. We named him “Doc Holiday’s Huckleberry” with the call name “Huck” and felt sad at the loss of the name with the passing of Huck. To honor our sweet boy, the lives we have lived as individuals and as a couple, and to honor our past and our future, we have chosen to name our next pup “Huck’s True Grit,” call name “Grit.” There is no replacing Huck. We would not even try and nor do we want to. There is only a creation of space in our hearts and in our lives for who and what Grit will be. Every dog has something to teach us, even if all you get is one hundred fifty-four days.

Hunt & Field 43

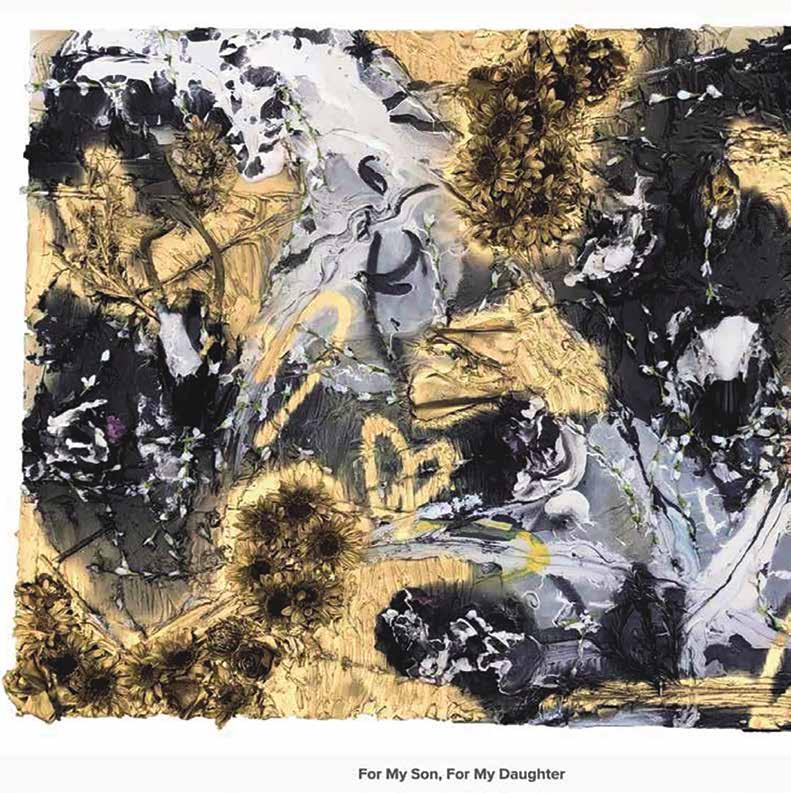

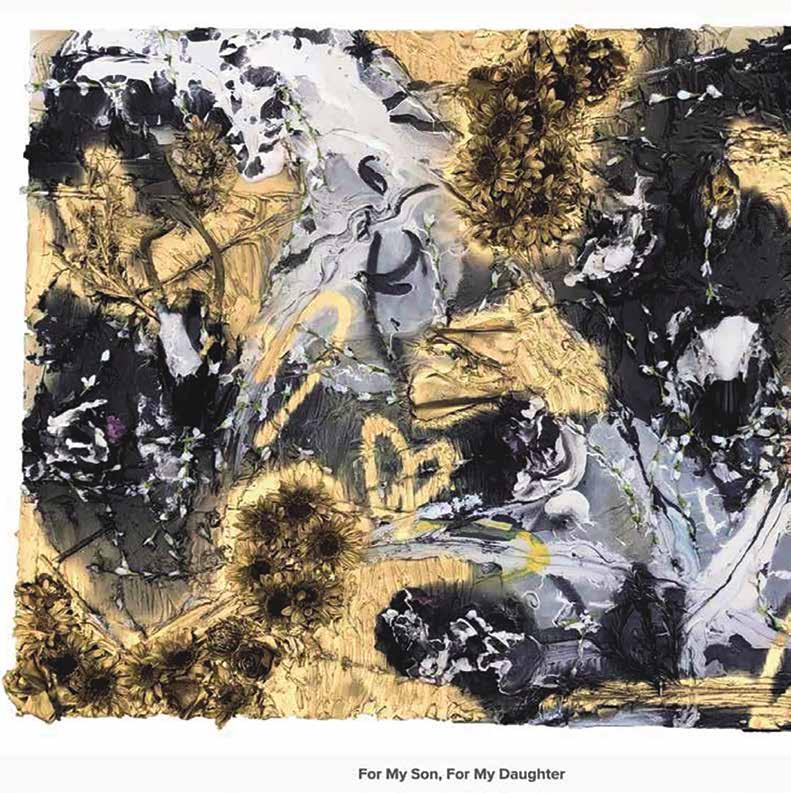

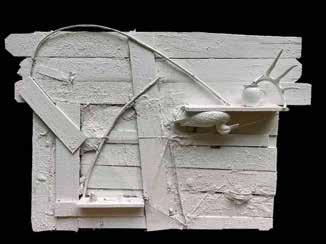

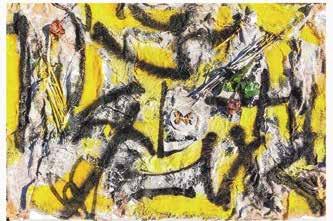

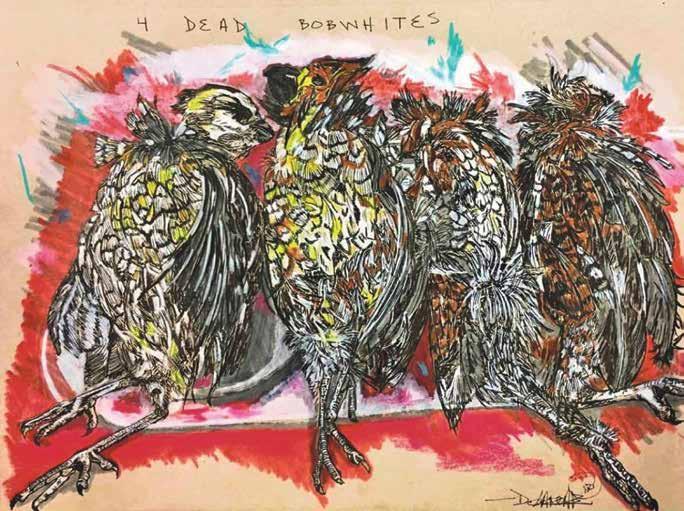

American Soil |

44 Hunt & Field

American Soul

Uncovering and Expanding America’s Conservation Story

Artists: Durrell and Ashley Smith

Hunt & Field 45

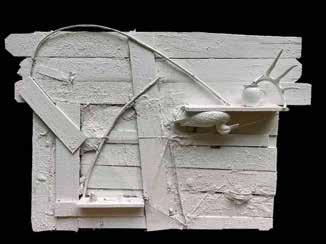

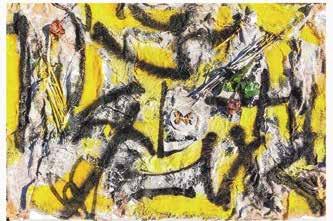

In the heart of the quaint Vinings neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia, a powerful and thought-provoking fine art experience awaits art enthusiasts, sporting folk, and conservationists alike. “American Soil | American Soul” is a collaborative art show presented by Durrell and Ashley Smith, two artists deeply connected to the soil of America and committed to healing the soul of the nation through their work in the great outdoors. On August 26th, 2023, the doors of Overlook III will open to welcome visitors into a realm of captivating visual representation by Durrell Smith, complemented by an evocative oratorical expression by Ashley Smith.

The creative minds behind “American Soil | American Soul” invite their audience on a journey that delves into the profound relationship between humanity and nature. Durrell Smith’s assemblages embody the essence of the South, capturing its rich heritage, natural beauty, and distinctive charm. His found objects and pieces indicate a love for primitive and indigenous cultures, a fascination with the great outdoors, and an exploration of humanity’s connection to the natural world within a contemporary context.

Through his bold brushwork, gritty line work, vibrant colors, and meticulous attention to detail, Smith’s watercolor, Goache, and india ink paintings transport viewers

46 Hunt & Field

to picturesque Southern vistas, evoking a sense of tranquility and nostalgia.

What sets Durrell Smith apart as an artist is his ability to infuse his creations with a sense of Southern storytelling. Each piece carries a compelling narrative, drawing viewers into the emotions and experiences depicted. From portraying local characters to glimpses of daily life and tradition in the region, Smith’s art celebrates the spirit of the South and establishes a powerful connection between the horses, the bird dogs, and its reverent audience.

His artistic process is equally intriguing, as each work begins and concludes outdoors, allowing the elements to transmit a spirit and vitality to every piece. The artworks serve as visual interpretations of communication, capturing, analyzing, and juxtaposing the auditory with the metaphysical senses. Smith uses culturally familiar forms of mark-making, instinctual bodies of line, emotional connections, and sensory perception to convey his artistic vision.

Complementing Durrell Smith’s visual artistry is Ashley Smith’s oratorical expression, which adds depth and context to the art show. Ashley’s words will transport the audience to a place of reverent understanding of the human relationship with nature, inspiring them to recognize the urgency of environmental stewardship.

The central theme of “American Soil | American Soul” revolves around the inextricable link between the health of nature and the health of humanity. As society has modernized, an undeniable chasm has emerged between human society and the natural world. The growing disconnection between humanity and nature lies at the heart of our present-day environmental issues. This art show serves as an artful, yet rallying, invitation to heal this separateness and unite as responsible and compassionate stewards of the Earth.

Durrell and Ashley’s commitment to honoring their calls as artists has led them to find boundless inspiration for sharing joy through the outdoors with others. Their works also raise collective awareness of the need for everyone to become conservationists. Through their art, they explore the confluence of joy and responsibility that comes with environmental stewardship and how finding a connection point with the outdoors positively impacts the internal ecology of individuals and communities, enabling collective progress.

By attending “American Soil | American Soul,” the audience is reminded that environmental stewardship is not a choice; it is a collective responsibility. The fate of our planet rests in the hands of each individual, and the urgent need to act requires immediate and sustained efforts to reverse the damage caused by human activities. Preserving ecosystems, protecting biodiversity, and addressing climate change are paramount to securing a sustainable future for generations to come.

Through the lens of art, Durrell and Ashley Smith deliver a compelling message that resonates with visitors on a profound level. The art show not only showcases the beauty

of America’s landscapes, but also serves as a poignant reminder of the urgency to protect them. By embracing environmental stewardship and making conscious choices in our daily lives, we can pave the way towards a more sustainable and harmonious coexistence with nature.

“American Soil | American Soul” is an artful masterpiece that goes beyond aesthetics and delves into the core of America’s conservation story. Durrell and Ashley Smith’s artistic expressions serve as a powerful medium to inspire

change, foster empathy, and instill a sense of responsibility towards the environment. Their art invites us to reflect on our interconnectedness with nature and the imperative to act as stewards of the Earth. As visitors leave the art show, they carry with them the seeds of environmental awareness, ready to grow and bring about positive change for the planet we all call home.

48 Hunt & Field

DEVELOPED BY EXPERTS. TRUSTED BY LEGENDS.® SPORTSMANSPRIDE.COM HANDLER, STEVE HURDLE BACK HOME KENNELS • HICKORY FLAT, MS COLDWATER THUNDER 2 021 NATIONAL FIELD TRIAL CHAMPION

Written by Durrell Smith

Morton

Written by Durrell Smith

Morton