Summer School of Albanian Alps II carries out the first detailed mapping of a upland settlement in Albania

“To Remember, One Must First Record” — Community Day in Nikç, Kelmend, Albanian Alps

“Hut to Hut” Family Tour in Kelmend Nature Before Man, and Man Before Nature –and Himself. Reflections and Notes from an Inspiring tour through the High Pastures of Kelmend

A Journey Through the History, Soul, and Pride of the Kelmend High Pastures

Once among the most remote and least urbanised villages in the region, Nikç is now emerging as the most comprehensively documented settlement in Kelmend—a progression driven by nearly two years of dedicated fieldwork led by GO2Albania.

The initiative began with a series of exploratory visits aimed at familiarizing the team with the terrain. During these visits, GO2Albania invited professionals from a range of disciplines—including architects, archaeologists, conservators, architectural historians, journalists, anthropologists, GIS experts, biologists, and forest engineers, representing universities and research centres across Albania, Kosovo, Italy, Germany, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Peru, and the United States. Through this multidisciplinary team, in addition to technical reports in their respective fields, the visits produced detailed archaeological observations, documentation of vernacular architecture and settlement patterns, as well as extensive audio-visual interviews with local residents for ethnographic and anthropological studies. Aerial drone photography conducted at altitudes of 50–200 meters has resulted in a high-resolution orthophoto of the village, captured in the spring of 2024. This orthophoto now serves as a foundational layer for ongoing data collection and analysis, which GO2Albania experts are continuously updating within a Geographic Information System (GIS) database. This foundational data has also been presented and discussed with international experts during GO2Albania’s working visits to universities and research centres in the United States, Belgium, Italy, Kosovo, Portugal, and other countries. The purpose of these exchanges was to draw on global experience with similar approaches in upland settlements across various continents—including the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia—in order to design a transdisciplinary methodology for mapping the cultural landscape of Nikç. This methodology is intended as a pilot that could later be extended to other villages throughout the Albanian Alps. The drafting and development of this methodology required several months of collaboration and refinement, incorporating the various layers of information necessary to construct a comprehensive database structure for the area. As a result, the methodology integrates intensive architectural survey, including primary data collection through measurement and photographic documentation of buildings, structures and cultural landscape elements. It also includes interviews with local residents, GPS-based mapping through field walks, and the 2024 orthophotos as a spatial reference.

This being said, over a year of preparatory work was required to organize the Second Edition of the Summer School of the Albanian Alps, held under the theme “Mapping the Cultural Landscape.” The school took place in Nikç, in the Cem Valley of Kelmend, from July 11th to 21st, 2025.

In addition to applying the methodology and collecting data, the school aimed to provide non-formal education to a new generation of young professionals through handson fieldwork and laboratory-based activities. The goal was to help participants understand the evolution and formation of a settlement—specifically, a mountainous one in the Albanian Alps.

continued from page 1

The young professionals who participated in this Summer School came from the Polytechnic University of Tirana (AL), the Agricultural University of Tirana (AL), the University of “Hasan Prishtina” in Prishtina (KS), Polis University in Tirana (AL), the Polytechnic University of Turin (IT), the University of Genoa (IT), and the Federico II University of Naples (IT). Their profile included urban planning and architecture, doctoral researchers in architecture and landscape archaeology, lecturers in genetics, as well as GIS experts and specialists in protected areas and natural landscapes. Depending on their field of expertise, participants were supported by Dr Hartmut Müller, the German expert who played a decisive role in the inclusion of Albania’s natural heritage sites—such as the Gashi River and Rrajca—in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

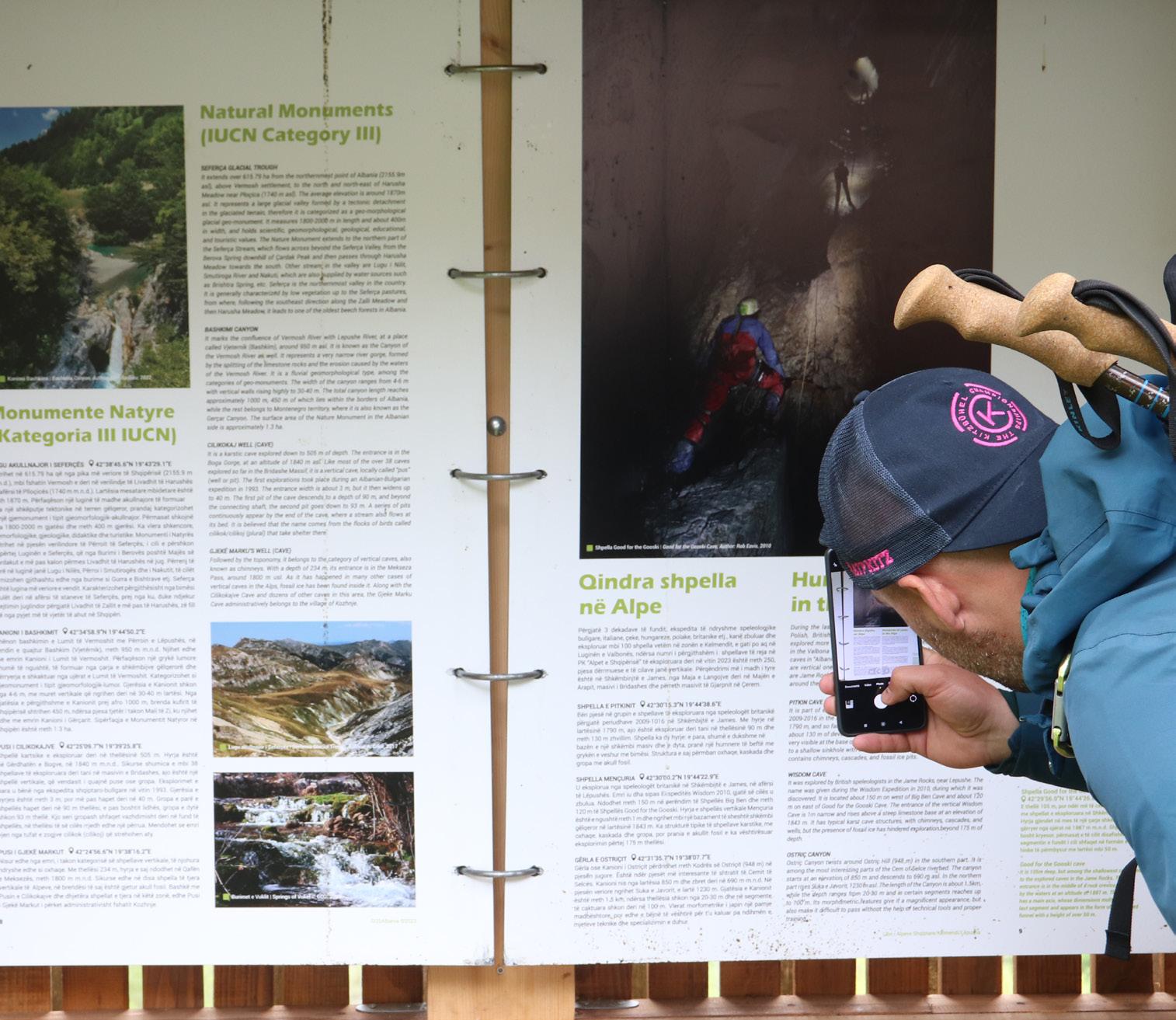

Alongside the intensive training on cultural landscape documentation methods, participants had the opportunity to engage with the experiences of peers working in various areas of architecture and restoration. These included projects developed through broad international partnerships in which several Albanian institutions play leading roles. Participants were also introduced to an extensive visual anthropological study of the Kelmend area, presented as part of an open-air cinema. Supported by the GO2Albania team—who, alongside local residents, have become deeply familiar with the area—participants were divided into groups and equipped with the necessary tools for documentation. They undertook intensive data collection in a highly rugged and mountainous terrain, dominated by stone and rocks of various sizes—a defining feature of the village of Nikç.

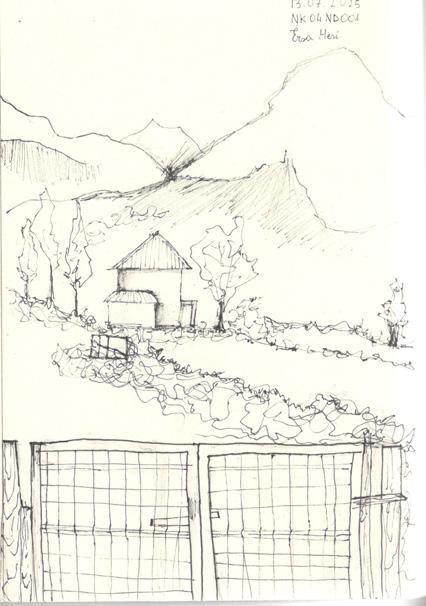

The role of local residents proved essential. Despite the comprehensive design of digital survey forms and the training provided to participants, no database could have been complete without the community’s collaboration. This is due in part to the fact that historical data—held in the archives of several national-level cultural institutions—has often been fragmented and shaped by the research priorities of specific periods, rather than offering a holistic picture. Welcomed and guided by locals—both in navigating the physical terrain and in accessing the village’s collective memory—each group, over the course of ten days in the field, completed hundreds of digital survey forms. These involved measuring, recording coordinates, and collecting detailed data on three of Nikç’s central neighbourhoods: Rranxa, Preldakaj, and Lekndrecaj, which together cover an area of approximately 60 hectares. Although these neighbourhoods make up roughly half of the village’s total area, they account for around two-thirds of its residential and service-related buildings, representing the most densely populated part of Nikç up until 2-3 decades ago. Other neighbourhoods—such as Llac and Ryec—and smaller settlements like Shipezhna and Dërdhena, are located at greater distances and in even more challenging terrain. These areas are planned to be documented in a second phase. Therefore, the practical component of the Summer School II focused on mapping the lower part of the village, located at 600–680 metres above sea level. During this phase, detailed data was collected for approximately 122 structures, representing a variety of functions, sizes, and structural conditions. Additional data was gathered for a wide range of other landscape elements, including land parcels, current agricultural crops, fences, boundaries, terraces, grain storage huts, reservoirs, and irrigation canals.

As a point of convergence for several scientific disciplines—a virtually unknown approach in Albania (recently introduced to professionals and the wider public through the extensive publication Cultural Landscape: A Guide to Understanding, Valuing and Preserving in the Highlands of Albania and Kosovo, GO2Albania, 2025)—and still relatively new even among international experts, the concept of the cultural landscape is both fascinating and demanding. Documenting its countless elements requires long-term commitment. Activities such as building measurements, GPS coordinate collection, photography, and the gathering of quantitative and qualitative field data represent only a small portion of the overall work. For this reason, each long day of fieldwork by the working groups was followed by even longer hours dedicated to data entry into the database system— what can be considered the laboratory component of the process. Enriched further by layers of information on traditional lifestyles—gathered through numerous audio-video interviews with local residents—this data will be processed via GIS to enable analysis of various aspects of interest, not only within the scope of cultural landscape studies but also more broadly.

This is the pathway through which Nikç is making the transition from oral history into the documented historical record of Albania—as the first village where not only every building has been precisely documented,

on page 4

The Albanian Alps National Park (IUCN Category II) was established by Decision of the Council of Ministers No. 59, dated 26 January 2022, and is currently the largest national park in Albania, covering an area of 82,844.65 hectares.

Located in the northernmost part of the country, the park spans across the municipalities of Shkodër and Malësi e Madhe in Shkodër County, and the municipality of Tropojë in Kukës County.

To the south, the park borders three other natural parks:

“Nikaj-Mërtur” (established in 2014), “Shala Valley” (2022), and “Shkrel” (2016). To the north, it adjoins “Prokletije” National Park (2009) in Montenegro, and to the northeast, “Bjeshkët e Nemuna” National Park (2012) in Kosovo. Together, these protected areas form the broader ecosystem of the Albanian Alps, located at the southeastern extremity of the Dinaric Alps.

The Albanian Alps represent the most majestic and culturally rich region of the country—a land of myths and legends, of the Songs of the Frontier Warriors and the Kanun customary law, of warriors who go to battle singing the kângë mâjekrahu (the song over the arm) and are honoured with the gjamë (lament) of men, of sacred oaths (besa) and legendary women known as burrnesha. This mountainous territory is also the ancestral homeland of most of the ten historic northern Albanian tribes (fis), whose influence has extended across history from the Danube to the Aegean, and from the Apennines to beyond the Atlantic.

The traditional way of life of the inhabitants—living from river valleys up to the most remote and rugged mountain streams—has evolved very slowly over the past 3,000 years, shaping what we now understand as the cultural landscape of the region.

This landscape holds invaluable historic, anthropological, archaeological, ecological, and intangible heritage—much of it at risk due to depopulation, modernisation, and the growing impacts of climate change. To document and better understand this heritage, the Second Edition of the Summer School of Albanian Alps is organised under the theme: “MAPPING THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF SETTLEMENTS IN THE ALBANIAN ALPS” continued on page 5

For thousands of years, since humans first domesticated the dog - and later the sheep, cow, goat, pig, horse, and others - the breeding of these animals, which fundamentally changed the lifestyle of their domesticators, has remained one of the most sustainable and harmonious relations between humans and nature. Threatened today by urban uniformity, pastoral life still endures across six continents, including in the northern mountains of Albania. Historically known as a tribe of shepherds and warriors, the highlanders of Kelmend must now struggle to keep this tradition alive. To explore the distribution of seasonal upland settlements in the pastures of Kelmend, GO2Albania organised the family tour “Stan m’stan” (Hut to Hut) on May 23rd–25th, 2025. The tour brought together professionals from diverse backgrounds - journalists, biologists, agronomists, explorers, tourist guides and other actors interested in this heritage. As one of the organisations that has worked for years in the three major valleys of the “Albanian Alps” National Park - Valbona, Shala, and most recently, Cem - GO2Albania continues to build a comprehensive database on almost every aspect of the natural and cultural landscape of the “Albanian Alps” Protected Area. Owing to this background on the context, participants received rich and detailed information about the cultural landscape and people of the Alps throughout the tour, especially on transhumance, now on the list of UNESCO as Intangible World Heritage. Regarding the alpine pastures within Core Zone B and the Traditional Sustainable Use Zone, as stipulated by the Law on Protected Areas (Law no. 21/2024) and the park’s internal zoning (Decision of the Council of Ministers no. 59, dated January 26, 2022), human

activity in these areas is linked to the efforts of the Protected Areas Administration (RAPA) of Shkodër. Elements of this genuine relationship of trust, alongside broader issues regarding the protection of the country’s largest national park, were tackled in an engaging open discussion between highly interested attendees and Mr. Tonin Macaj, a forest engineer representing RAPA Shkodër.

On the second day, despite the less-thanfavourable spring alpine weather, the group visited many shepherds’ huts in the meadows of Koprisht, located south of Gropat e Selcës, located at elevations ranging from 1,450 to 1,800 meters above sea level. As centuriesold highland pastures, these settlements bear historical layers: traces of old huts shaped like pits with dry-stone walls, kilometres-long pasture boundaries also marked by similar drystone walls, basic tools testifying to pastoral life, and alpine graves of ancestors, shepherds and martyrs of neighbourly greed. But the real-life experience of today’s shepherdsfollowing their grandfathers’ footsteps, leading their flocks from Grabom and Kalca of Brojë to Koprisht and Pajë - was shared firsthand on the third day of the trip. Spontaneous, openminded, eloquent, and full of joy, Lush and Gazmend were captivating with their stories and life advice about life in the uplands, and singing the song over the arm. After cutting the season’s first hay as food for the long alpine winter, they are now making final preparations to ascend to the highlands. From the beginning of June to the end of September, they will bring life to the alpine meadows with the laughter of their beautiful children and the cheerful bleating of their sheep.

When we set off as Reality Escapers Albania towards Malësia e Madhe, we had no idea we would return not just with memories, but with a piece of the soul of this ancient land. Under the guidance of GO2Albania, we followed the trails of the highlands on a journey that was far more than a simple hike — it was a step back in time, an embrace of history, and a deep encounter with the very essence of Albania.

Along the way, we were accompanied not only by the untamed beauty of nature, but also by vivid scenes from the film “The Collapse of Idols” (Shembja e Idhujve), shot in Kelmend — a film not for the faint of heart, as each stone and each path holds echoes of resistance, memories of war, and unwavering love for the homeland.

We walked where once highlanders lived with dignity and survived with pride. Here, the land is not just land — it is history. The graves at Koprisht Pasture are not simply a memorial — they are a living wound in our collective memory, where 73 men were massacred by Montenegrin forces in 1913. Not for any crime, but simply because they were highlanders — people who never bowed, who never laid down their arms, and whose pride could not be broken.

In these same high pastures, we met two individuals who carry something increasingly rare today — an unbreakable bond with the land. Lush Turkaj and Gazmend Bikaj, two shepherds who still spend their summers in the mountains, just as their forebears did decades ago. In a time when so many say, “I’m leaving,” they simply smile and respond with quiet certainty: “Better in my own highlands than at the end of the world.”

This is the philosophy of resilience — proof that no distance can replace the warmth of your homeland. This journey was both a remembrance of the past and an inspiration for the future. A call to never forget our roots, to hold tight to our connection with history, with nature, and with the real people who are still here — guardians of the soul of the mountains.

“Stan m’Stan” (Hut to Hut) was not merely a physical journey. It was an emotional experience — one that reminded us how much wealth lies in simplicity, in endurance, and in the love for the place you call home.

2025. “Kelmend through the colours of Kinostudio” was received with curiosity by the tour operators who were on the family tour. Photo: GO2

I first encountered Lepushe a decade ago, during an annual event aimed at drawing public attention to the region’s natural wonders and cultural traditions—an effort towards what we now like to call, in a very fashionable term, “revitalisation”.

The three-day “Stan m’ stan” (Hut to Hut) tour, introduced by a respected entity as is GO2Albania organization—whose work I have followed for years—offered a long-awaited opportunity to delve into the deeper layers of this area’s heritage. Even more so because this western stretch of the “Albanian Alps” National Park remains relatively unknown, especially when compared to more familiar names like Theth or Valbona.

The weather was overcast. Thick clouds and fog limited our view of the mountain vistas and muted the awe such landscapes usually evoke. Yet, intentionally or not, this drew our attention more deeply towards the local culture1) and the pressing challenges of preserving it.

Much of this came through our conversations with local people. We began with our passionate guide, Mëhill2); then there was the Çeka family, who hosted us and set generous tables with traditional dishes from the region. I spent two nights with the family of Tomë Dragu, who is associated with a beautiful local legend celebrating besa (oath)—the Albanian code of honour and hospitality, which stands as a distinguished cultural tradition here3). We met shepherds Lush and Gazmend, who are building their livelihoods in the pastures, diversifying with guest accommodation and food services for mountain trekkers4). And of course, we spoke at length with the dedicated organisers of the tour—tireless and deeply passionate advocates for this land5)—as well as with representatives of the project’s donors. What has already happened in other parts of the Alps—both the positive and the negative—is slowly making its way here too.

The “guesthouse-ification” of local homes is on the rise. Modern alpine-style cabins are sprouting up across Lepushe. Yet, at the same time, the distinctive features of traditional local dwellings are vanishing. The only one somewhat preserved is Tomë’s house, though even he has built two wooden alpine huts for guests—similar to those found anywhere else in the world.

On another front, the rearing of small livestock—a timehonoured occupation in this region—is proving increasingly profitable. Locals are becoming more skilled and professional in this area. To the traditional activity of shepherding, they’re now adding hospitality, welcoming both Albanian and international visitors drawn by the spellbinding beauty of the highland pastures.

continued on page 6

1) This refers to a broad and profound understanding of the word “culture.” According to anthropologist E. B. Tylor, culture is “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.”

2) I’m not entirely certain whether the name should be written “Mhill” or “Mëhill” – with a schwa (ë). The same uncertainty applies to the name “Tom” (as seen in current media) or “Tomë” (as it appeared on the signpost of the family guesthouse). And you think to yourself: “Knowledge and ignorance are both infinite and omnipresent.”

3) The original surname of Tomë’s clan (fis) is Gjerkaj, though over time it was changed to Dragu, in honour of a solemn moment in which a blood feud between this family and a Montenegrin adversary was reconciled. “Dragu” evokes the root of the word for “beloved” – a direct antonym of “enemy.”

4) Showcasing the potential for the development of this type of activity by local residents was, in fact, one of the main objectives of the event.

5) “Tash po e shofim nesër” (We’ll see to it tomorrow) – a powerful local expression that prepares the mind to view the present from the perspective of the future. We heard this phrase from Eltjana, a doctor of science, during her insightful explanations throughout our tour. I also learned the word “tëbanë”, which, as often happens in the Gheg dialect, is pronounced “t’bán” in this region. It turns out this is an Albanian word used for “stan” (seasonal shepherd’s hut), the latter being of Slavic origin.

Data entry into the system takes a lot of time.

continued from page 2 but also every stone deposit (locally called gumile), every gate, every electricity pole, and every man-made intervention in this otherwise inhospitable mountainous terrain.

In this way, the integration of fieldwork with laboratory-based analysis, the close collaboration with dedicated experts who possess in-depth local knowledge, the deepened understanding of a settlement model that, fortunately, still preserves a living material and spiritual culture, and the opportunity for engagement and exchange among young professionals from diverse fields—all contribute to making the Summer School of Albanian Alps II a profoundly valuable experience for its participants, whether they are students from various disciplines or other professionals.

More than the data collected so far, the database model that has been developed represents a national asset—one that can be replicated in other upland settlements across the country. It serves both as an archival testimony to a specific historical moment—namely, the end of a 35-year transitional period during which such field documentation was absent—and as a tool for capacity building among Albanian professionals. It offers substantial support in aligning local efforts with international expertise in this field. Moreover, this model can form the basis for sustainable, evidence-based planning aimed at the preservation and conservation of vernacular architecture and locally rooted typical elements—at a time when, with conviction, we hope our institutions will open up to the legal protection of the cultural landscape.

continued from page 2

Location: Nikç, Kelmend, Cem Valley, Albanian Alps

National Park

Dates: 11–20 July 2025

Organised by: GO2Albania

Partners: Tramontana Network, Regional Protected Areas Administration

Shkodër

Funded by: Prespa Ohrid Nature Trust (PONT), the European Union, and the “CLOE” project under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions.

This 10-day summer school will take place in one of the most remote and best-preserved settlements in the Albanian Alps. It offers a unique, in-depth field experience focused on the recognition, documentation, and mapping of its cultural landscape—contributing to a deeper understanding of rural civilisation in the highlands of northern Albania (Gegni).

The programme provides an interdisciplinary space for field-based exploration, critical reflection, and the collective production of knowledge about upland settlements in northern Albania.

Objectives

• To explore and identify the cultural landscape of a upland settlement through field-based research;

• To document the physical elements of the cultural landscape using interdisciplinary methods and interpret their meaning;

• To raise awareness about the values and threats facing mountain cultural landscapes, which represent a significant heritage with anthropological, historical, cultural, and environmental importance.

Working with local communities has remained one of the core pillars of GO2Albania’s mission for over 13 years since its founding. Direct engagement with communities—their challenges and capacities—and their involvement at every stage of project development has created a vital foundation for initiatives that aim to empower and support local populations, seeking to strike a balance between the sustainable use of natural resources and the preservation of collective memory. Over the years, such community-based projects have extended across both urban and rural areas—from city neighbourhoods to the most remote mountain valleys. One of the most secluded of these is Cemi i Vuklit, a valley that begins in Nikç, a village that has long welcomed research teams dedicated to documenting its rich natural and cultural landscape—both tangible and intangible heritage. While tangible heritage is more readily identified, aspects of intangible heritage—such as the making and performance of traditional musical instruments like the lahuta and çifteli, or the distinctive kanga maje krahu (heroic epic song over the arm)—require a visit to one of the region’s most skilled and treasured tradition-bearers: the rhapsode and master craftsman Luigj Gjerkaj. Depending on their specific research interests, working teams have visited different parts of the village, meeting with individual families to explain the purpose of their work. However, documenting an entire village requires the participation of every household, as each member—especially the older generations—has a story to tell. This was particularly important during the mapping of the cultural landscape, when research teams entered every home and relied on the local knowledge of residents. To bring everyone together and create a shared space for dialogue, GO2Albania organised a Community Day under the motto: “To Remember, One Must First Record.” The event aimed to present the people of Nikç with the progress made so far and to explain the broader purpose of the organisation’s work in the village. The goal was to offer residents a clearer understanding of the ongoing research, raise awareness about the importance of heritage documentation in all its forms, and to foster a sense of shared ownership in the process. Despite the logistical challenges posed by the remote location, the Community Day featured an open conversation with residents and a multi-part exhibition that included architectural sketches of village homes, field notebooks used by the research teams, a dedicated section for local expressions and phrases recorded during the fieldwork, a pavilion showcasing medicinal and aromatic plants of the area, a detailed map of the “Albanian Alps” National Park and the screening

of a short documentary highlighting the heritage of Kelmend.

As residents gathered in the courtyard of the Catholic Church “Zemra e Krishtit” in Nikç, many remarked that it was the first time in more than three decades that the entire community had come together for a reason unrelated to religion, politics, or family events. Instead, this was a cultural gathering—an occasion to reflect on the many elements that shape the identity of their village. Although the village neighbourhoods are spread across steep terrain, with homes rising 300 to 450 metres above one another and separated by significant distances, everyone who could attend made the effort to be there—despite the intense heat of July.

The organisers opened the event with a few welcoming words, followed by a heartfelt exchange of mutual respect and appreciation for one another’s work—particularly for the remaining residents of Nikç, who continue to preserve a traditional way of life that is disappearing elsewhere in the mountains. During the exhibition, locals had the opportunity to view, touch, browse and read through the materials collected by the Summer School of Albanian Alps II working teams: architectural sketches, site plans, notes on agriculture, observations, and various other data gathered over the course of the documentation work. In doing so, they became the very first audience for a project still in progress. Speakers from the community expressed their appreciation for GO2Albania’s thoughtful decision to choose Nikç as the first village in the Albanian Alps to undergo such detailed documentation of both its tangible and intangible heritage. They also affirmed their willingness to continue collaborating in future phases of the project. It was this spirit of cooperation—and, above all, the extraordinary hospitality shown by the people of Nikç—that inspired the creation of a poem. Delivered by a student named Adela Alku, the poem moved the audience deeply and earned a heartfelt round of applause as a gesture of gratitude. Another highlight of the day was the screening of the film project “Kelmend through the Colours of Kinostudio”—an audiovisual anthropology study documenting the evolution of dwellings and settlements in Kelmend, as well as traditional clothing, customs, and the local population itself, extending to the impacts of climate change that now also affect the Albanian Alps. As the film was screened, many in the audience recognised familiar places, people, and events they had lived through up until the late 1980s. Upon leaving the improvised cinema space in Nikç, they paused to write their thoughts on the impressions board—where their reflections merged with those of the Summer School participants.

continued from page 4

All of this represents a vast potential for economic and social development—enough to sustain interest in staying among the few residents who remain, and perhaps even attract back some of those who’ve left.

But the reality tells a different story: depopulation is palpable here too. Across the area, you don’t see many people, while many have already left, and more continue to do so. Tonin, from the National Park Regional Administration, confirms this with a weary nod. And with essential services like healthcare and education fading or disappearing altogether, the prospects for staying are becoming increasingly bleak.

Shepherds Lush and Gazmend are preparing to spend the summer in the high pastures with their families and livestock. Each has six or seven children. Will their children want to stay and build lives here among the mountains? Will they be able to? And the one who’s already in Canada—will he return, as he once promised? And with that in mind: what will the Kelmend Highlands look like ten years from now?

Many answers to this—and even more questions—are tied to the outcomes of the recently adopted “Mountain Package”, a new law aimed at stimulating investment in mountainous regions. This package is open to all interested parties, whether emigrants or local residents, who have both the desire and the vision to build on their “own land”. At the same time, it seeks to resolve the long-standing issue of unclear land ownership6). According to its stated goals, “The package aims to

create a balanced and sustainable framework for the development of mountain tourism, agriculture, industry, and eco-innovation. It is intended to support economic growth in priority highland areas, while safeguarding the natural landscape, preserving cultural heritage, and protecting the local identity and traditions of these regions”7). It all sounds promising. But experience has taught us to be cautious— too often there’s a wide gap between the ambitions stated in a law and the reality of its implementation.

Will the “Mountain Package” succeed in reviving the desire to live in these remote areas, while also respecting and nurturing local traditions? Will Lepushe evolve into a sustainable tourist destination, as other parts of the Alps have done—this time avoiding the mistakes made elsewhere? Will the lessons be learned before the tide of mass tourism sweeps in, often leaving irreversible damage in its wake?

How will we balance the unchecked drive for profit with the natural, human aspiration for a dignified and modern way of life? How can the highlands become attractive places to live, without losing their essence?

6) Law 7501, which introduced the principle “Land to the one who works it”, has never been applied in this area.

7) [Link to official government statement]: https://www.kryeministria.al/newsroom/paketa-e-maleve-nje-thirrje-per-kedo-qe-kerkon-te-investojene-token-e-te-pareve/

8) I recently witnessed an inspiring example of “revitalisation” in Gibellina, Sicily – a town entirely rebuilt after being destroyed by an earthquake. The goal there is to use artistic creativity from around the world as a catalyst for economic and social development, as well as for repopulation. A museum has also been established to showcase Mediterranean culture, which has long been rooted in Sicilian history. The MonArt project (Monasteries of Art), supported by the European Union under the Creative Europe programme, aims to further develop these efforts.

The challenges, the opportunities, and the risks are all there—different in some ways, yet strikingly similar to those we face as an organisation working in the south of Albania. There are lessons to be shared—good and bad— alongside valuable international experiences8). And this is precisely where the value of activities like this lies. No. 38, August 2025