28 minute read

Background information for adopting a policy encouraging earmarked tobacco and alcohol taxes for the creation of health promotion foundations

from P&E

The use of “sin taxes” to fund heath promotion foundations: introducing the debate addressed in Karen Slama’s article

Commentary by Michel O’Neill

Advertisement

Finding ways to fund health promotion infrastructures and interventions is a constant and major problem, most countries devoting an extremely low percentage of their health budget to these endeavors. In order to alleviate this problem, a few innovative countries have decided to earmark certain tax monies for health promotion purposes, these monies being sometimes channeled into public Foundations totally or partially dedicated to health promotion interventions. The Australian state of Victoria led the way, followed by other Australian States and after that by several other countries as diverse as Switzerland, Thailand or Poland, to name but a few. These foundations are now organised in the International Network of Health Promotion Foundations <www.hpfoundations.net/>. These public foundations are quite different from private ones, like the Melinda and Bill Gates Foundation for instance <http://www.gatesfoundation.org/defaul t.htm>, which can work rather independently <http://www.gih.org/usr_doc/2003_Co nversion_Report.pdf> or in close partnership (see the Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon for instance <http://www.fondationchagnon.org>) with governments. In many instances, these public foundations get their funding through mechanisms involving the utilization of taxes levied on products potentially harmful to health like tobacco or alcohol, often labeled “sin taxes”.

In order to reflect on this complex topic and eventually take a position on these issues, the Board of Trustees (BOT) of the International Union for Health Promotion and Health Education (IUHPE) has commissioned an important paper1 which has been presented to its executive in Paris in December 2005. Looking at several countries, the paper first documents how the taxation of alcohol and tobacco can be utilized as a policy instrument to promote the health of populations, reviewing the potential harms and benefits of doing so and showing that the impact of taxing tobacco is quite different than taxing alcohol. The paper then goes on to discuss the issue of earmarking (i.e. specifically dedicate) taxes for health purposes and some of the ethical, social justice and economic dilemmas that this practice can raise. Finally, the question of channeling earmarked taxes into Health Promotion Foundations is treated and lessons learnt in doing so over the past decade are exposed.

The paper has generated significant interest and debate at the IUHPE Executive Committee meeting of December 2005. Even if it is of common use in certain quarters, the expression “sin taxes” seemed very moralistic, culturally specific and inappropriate to many. The fact that the paper was commissioned to make the case that earmarking and health promotion foundations were appropriate mechanisms, rather than asking in a less committed way if we had sufficient evidence to actually make the case, was questioned by others. Finally, the fact that the utilisation of taxation as a policy instrument to promote health was covered in the same paper than earmarking taxes for health promotion foundations seemed a bit confusing to some.

Consequently, it was decided that two sets of reactions would be sought on the paper in order to provide additional input to IUHPE Board of Trustees, for discussion and eventual adoption of a position. On the one hand, under the guidance of IUHPE Vice-President for Advocacy Marilyn Wise, a more internal discussion would be undertaken on the BOT electronic discussion list. On the other hand, and it is what we are doing here, a call would be made to the general membership of IUHPE to contribute its reflections and reactions through Reviews of Health Promotion & Education Online – RHP&EO (www.rhpeo.org). IUHPE members are thus invited to react, using the usual guidelines to do so that can be found in the RHP&EO website. Even if you do not want to react, reading this paper is surely a very useful endeavor for anybody concerned with funding health promotion infrastructures and interventions, because it raises quite successfully most of the issues and dilemmas involved in using tobacco and alcohol taxes (and eventually the taxation of other products with a high detrimental potential to health like fastfood, weapons, etc.) to do so.

Websites of Health Promotion Foundations

Austrian Health Promotion Foundation: www.fgoe.org BC Coalition for Health Promotion: www.vcn.bc.ca/bchpc/ Health 21 Foundation (Hungary): www.health21.hungary.globalink.org Health Promotion Switzerland: www.promotionsante.ch Health Promotion Foundation (Poland): www.promocjazdrowia.pl Healthway: www.healthway.wa.gov.au ThaiHealth: www.thaihealth.or.th

VicHealth: www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/

Michel O’Neill Editor in Chief, RHP&EO Laval University Quebec, Canada Email: Michel.ONeill@fsi.ulaval.ca

1. Slama, K. (2006) “Background information for adopting a policy encouraging earmarked tobacco and alcohol taxes for the creation of health promotion foundations” Promotion & Education. XIII (1): 30-35.

Karen Slama

z There are a number of ways to examine the issues involved in a) raising taxes on specific products to influence health and b) the dedication of a proportion of those taxes to specific purposes, in this case, earmarking taxes for the creation and maintenance of a health promotion foundation. This background paper will examine some of the common considerations of fiscal policy in relation to alcoholic beverages and tobacco products, look at the impact of raising prices on changes in consumption and the corresponding health and social consequences, examine more specifically the pros and cons of earmarking a portion of alcohol and tobacco taxes for health promotion, and look at some aspects of successful creation of health promotion foundations based on earmarked taxes.

A basic economic truth is that the price of a product is linked to the demand for that product, and an increase in price is expected to lower demand, other things being equal. Those other things can be legal, cultural, normative or related to characteristics of the product, such as its addictive potential (Cook & Moore, 2002). Price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in consumption resulting from a 1% increase in price. As long as the price elasticity of the demand is less than a value of -1, an increase in taxes will result in a net gain in total tax revenues. This is the case for tobacco.

Taxes on tobacco products are important for generating revenue. The major criteria for choosing a revenue-generating tax are equity and efficiency. Equity in taxation means that there should be an equal tax burden among tax payers, either through taxes based on individual benefit received from services provided by the government or through taxes based on an individual’s ability to pay. So-called «sin» taxes apply the benefit principle; that individuals pay for the use of government-provided services in proportion to the benefits they derive from them. Alcohol abuse and tobacco consumption generate an economic burden that affects all individuals in the society and not just the users, so the total tax revenue collected should be equal to the total societal costs. Because consumption decreases even with inelastic products, policy can also have public health objectives. If a price policy has as its goal to reduce consumption of dangerous products such as alcoholic beverages or tobacco products, it is usually excise tax that is raised (Chaloupka et al, 2002); the cost is passed on to consumers in the form of higher retail prices. A 10% increase in tobacco prices reduces consumption by 4% on average in developed countries, and by 8% in low and middle-income countries (WHO, 2002). In Thailand for example, price elasticity for tobacco is estimated to be 0.7 (Siwraksa, no date).

Raising alcohol taxes may not generate substantial revenue; there appears to be no consensus on the size of effect and there is disagreement as to the responsiveness to price of the heaviest drinkers. Nevertheless, economists agree that even small variations in price have an impact in reduced consumption (Cook & Moore, 2002).

Tobacco can be taxed more heavily than products with elastic demands (Hu et al, 1998). But for both alcohol and tobacco, many countries have not raised taxes to keep up with inflation and thus do not benefit from either the revenuegeneration or public health benefits of raised taxes. In 11 out of 42 countries investigated in a recent study, tobacco prices in 2000 were more affordable than they had been in 1990, and in Iran, Egypt, and Viet Nam, prices had decreased by more than 50% (Guindon et al, 2002). In the US external costs for alcohol were over three times the tax rate in the 1980s (Cook & Moore, 2002). With decreased taxation, consumption rises. For example, in 1999, Switzerland reformed its spirits markets in line with World Trade Organisation agreements, decreasing prices and encouraging market competition. Alcohol consumption increased significantly, particularly among young people and there were corresponding increases in alcohol-related problems (Mohler-Kuo et al, 2004). When Canada reduced tobacco taxes in 1994 to counteract increased smuggling, consumption rose dramatically as did youth prevalence of smoking. With trade liberalisation, low income countries that previously had tobacco monopolies are subjected to competition and general price decreases. In the 1990s, opening their markets resulted in net increases in tobacco use in Japan, Korea and Taiwan. (Chaloupka & Corbett, 1998).

Karen Slama, PhD. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Paris, France Email: kslama@iuatld.org Benefits of price policy for tobacco and alcohol control

Tobacco taxes protect health, deter uptake, promote quitting and reduce exposure to secondhand smoke pollution (Wilson & Thomson, 2005). Raising taxes on tobacco products is considered to be one of the most effective components of a comprehensive tobacco control policy. Even when prevalence rates have decreased significantly, price increases remain a strong economic disincentive, as shown in a recent study of the effects of continued price rises in California (Sung et al, 2005). Indeed, cigarette prices are higher and have become less affordable over time in many countries with strong national tobacco control programmes. Appropriate tax levels for tobacco according to the World Bank are the equivalent of 2/3 to 4/5 of retail price.

The potential impact of a 10% increase in price is 40 million people quitting (4% of all smokers) and 10 million deaths

Keywords

•earthmarking taxes • fiscal policy • health promotion foundation

averted (3% of all expected deaths from tobacco). Of deaths averted, the greatest effect would be among younger smokers (Ranson et al, 2000).

For alcohol, consumers drink less and have fewer problems if alcohol prices are raised. Beer is often found to be the least responsive, spirits the most (Chaloupka et al, 2002), but price elasticity for alcohol is highly influenced by social values about drinking. Unlike for tobacco, alcohol consumption is highly concentrated in the top 10% of users, who consume more than half of all alcohol consumed. According to the “Single Distribution Theory”, the whole population is associated with drinking patterns. To reduce consumption among heavy drinkers, the entire population needs to decrease consumption (Cook & Moore, 2002). An increase in price reduces alcohol morbidity, mortality and adverse social events among light, moderate and heavy drinkers, and consequently reduces the number of rapes, robberies, incidents of maternal child abuse, spouse abuse, episodes of sexual misconduct, property damage and involvement in violence. And these effects are largest for those under 21 years of age. (Chaloupka et al, 2002). Youth are disproportionately represented in alcohol-related problems; the major cause of death among those under 35 in rich countries is fatal vehicle accidents, about half of which involve alcohol. Alcohol abuse in adolescence is related to later abuse (Ludbrook et al, 2001). So policies to reduce drinking among youth probably are the most effective in reducing drinking in the entire population. Price measures have been shown to reduce the percentage of youths who drink heavily, and to reduce binge drinking (Cook & Moore, 2002).

Potential harms caused by raising tobacco or alcohol taxes

There is no evidence that individuals or communities experience harmful health consequences from reduced consumption of tobacco products or alcoholic beverages. There may be a possible but unlikely reduction of the protective effect of very moderate alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease risk.

Increased taxes do, however, have the potential of causing harm in contributing to financial hardship among individuals who do not change their consumption.

Low income populations spend a greater percentage of disposable income on tobacco products, so tobacco taxes are regressive. In many countries the tobacco use prevalence and consumption rates are higher in low income groups than other income groups, increasing the hardship. But some see a «self-control» value of taxes in the extent to which the higher taxes help people to quit at some time in the future. The self-control element is probably more useful to low income people, so tobacco taxes can be beneficial overall to them (Lav, 2002). In other words, even if taxes on tobacco are regressive, tax increases can be seen as progressive in that they have more effect on low income groups and lead to reduction in health inequalities. Studies have found that price responsiveness is inversely related to social class and education. Smokers from lower income groups are more likely to quit in response to price rises rather than reduce consumption (Guindon et al, 2002). In addition, there are a number of possible remedies for hardship exacerbated by consumption taxes, such as providing tax relief or using earmarked revenues for health promotion in these populations. Tax changes in Australia resulted in decreases in consumption in both blue and white collar groups and the proportion of heavier smokers has declined. There has been more of an effect among low income groups, who are targeted by quit campaigns and mass media campaigns (See:http://www.quit now.info.au/tobccamp3.html)

Despite the clear advantage for public health of increased tobacco and alcohol taxes, structural barriers remain. In most countries, policy-makers are attuned to the short-term benefits and costs of policy. In countries with underdeveloped health sectors, most of the external costs of tobacco or alcohol are not assumed by governments so there is less of an impetus to recuperate costs. In both these situations, the short term perceived costs seem high in relation to tobacco or alcohol control policy: pressure from industry not to act, identifiable job losses if consumption drops regularly, (unfounded) fear of reduced tax revenues. (Chaloupka et al, 2000). Raising prices through taxation, however, can raise new revenue in the short-term, while enabling the full effect of taxes after many years as related disease incidence drops and higher prices reduce recruitment of new heavy drinkers or smokers. One of the best uses for a proportion of newly generated revenues from price policies to reduce consumption of unhealthy products is to legislate a funding mechanism for programmes through a health promotion foundation.

Earmarking

Government policy-makers should consider using price policy to reduce the damage caused by tobacco and alcohol. Overall, tobacco and alcohol taxation is justified, and there are many steps that can be taken to reduce harms and injustices (Wilson & Thomson, 2005). More and more countries are using earmarking of tobacco taxes to do this, and some add alcohol taxes. Earmarking a part of tobacco and alcohol taxes to finance health promotion foundations would provide the means for greater benefit for health than occur by only raising taxes. And yet concerns remain. The process of advocating for the creation of health promotion foundations from earmarked funds includes understanding and countering the arguments against earmarking. In this section, the arguments put forward to reject earmarking are assembled and followed by the reasoning and justifications for using earmarking.

Arguments concerning earmarked taxes can be grouped into the following categories, fiscal and governance issues, ethical issues, health and social consequences, justice and equity and economic issues. Arguments against earmarking are presented in italics, and are followed by possible rebuttals or evidence of advantages accruing to earmarking for health promotion.

Fiscal and governance issues

•Not all fiscal specialists are convinced about the equity and efficiency justifications made for tobacco taxation and earmarking. Instead of looking at the benefits, some look at the loss of consumer surplus, the loss of producer surplus, and dead-weight loss (the excess burden) on society. Some may object to transferring the costs of people smoking in past generations to younger current smokers. And depending on the methods

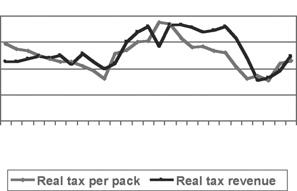

Figure 1 Taxes and revenues in Zimbabwe

1970 1973 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994

of establishing cost, some see possible medical and retirement cost savings due to tobacco-related early death.

The public generally supports special taxes on dangerous products for revenue needs and social goals. Because consumption of tobacco and alcohol impose public costs across communities, citizens accept that excise taxes do not broadly distribute the tax burden for public services (Hu & Mao, 2002). A major public relations flop occurred when the public rejected the conclusions of the Philip Morris International study funded for the Czech government which found the government would save on pensions because of deaths at younger ages among smokers. Once potent, this accounting procedure is no longer acceptable.

•There is greater flexibility for finance if all revenues are in a single pile.

Earmarking means that appropriation choices are removed from the legislature or the government ministry; this is generally contrary to government fiscal practices of allocation. Some feel that earmarking undermines financial discipline and introduces budgetary

rigidity in face of competing needs. Earmarking eases pressure on general revenue finance for particular public goods or services when users or beneficiaries of these sources can be easily identified. (Earmarking serves as a sort of replacement for direct charges for services). The reality of funding in competitive allocation is that prevention and promotion are discounted in light of needs for hospital and treatment services. If taxes are raised for earmarking, this creates additional funds, so regular tax revenues are not disrupted.

With earmarked taxes, the income stream is separated from the main budget. Resources are generated to reach those not reached by the tax itself through media or special programmes.

This is an appealing policy instrument for tobacco control or health promotion policy makers.

•Accepting the concept of earmarking taxes for health foundations may be blocked by the fear that if there is one extra-budgetary programme, that may be the beginning of a slippery slope of other special-interest programmes funded by earmarked taxes.

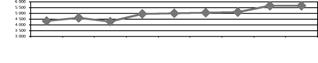

Figure 2 Revenues from tobacco taxation, Australia, 1995-2004

1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-2000 2000-2001 2001-2002 2002-2003 2003-2004 Earmarking allotted for a health promotion foundation is clearly in the public’s best interests. Experience shows that this does not lead inexorably to copycat proposals for earmarking (eg., fears at the creation of ThaiHealth have since been allayed.).

•On the other side of the issue, some fear that earmarking carries the possibility of instability of revenues over time. That is, as consumption declines, revenues in the long term also decline and the functioning of a health promotion foundation would be disrupted

There is no documented loss of government revenues upon raising tobacco taxes anywhere in the world. Examples of this are presented in the figures.

Ethical issues

•The major ethical issue is found in receiving funds directly from the industry involved and the conflict of interest that can be created. In the

United States, the Master Settlement

Agreement between 46 states and major tobacco companies specified that up to $206 billion would be allocated over 25 years to the states, depending on future sales to compensate for health costs due to smoking-related diseases. Conflict of interest arises when the fiscal health of the source of the money, the tobacco companies, influences decisions about the uses of that funding (Sindelar &

Falba, 2004). Declines in tobacco consumption have already reduced payments to states by 10% (-$1.6 billion) from what was initially projected, and the shortfall is estimated to rise to 20%. (Lav, 2002). Many states have invested little or none of this money into tobacco control. More generally, conflict of interest arises when funders can censor the content of health promotion programmes. The source of funding for health promotion from government allocation through earmarking or any other fiscal measure removes conflict of interest, for the revenue is what is paid by consumers, it is not taken from the profits of the producers; there is no impetus to help these industries to retain

their profit margins. Health promotion in general and tobacco control in particular are chronically under-funded. The tobacco industry works against the public good, and tobacco and other industries (alcohol, food etc) can use their money to distort public health priorities, far outspending anything that health promotion can fund. Resources are required to initiate alcohol and tobacco control programmes; price policy alone is not sufficient (Hu et al, 1998). By earmarking a portion of taxes for health promotion funding, all additional strategies will mutually increase the total impact for the public good and health promotion can make up for the shortfalls of price effects.

Health and social consequences

•Higher prices could enhance smuggling which would add additional costs and impede revenue generation. The expected beneficial effect on consumption and health may not occur if consumers have access to lower cost products, thereby subverting the purposes of the tax (Hyland et al, 2004).

Smuggling is more related to the degree of corruption in a country than the price of the product. Control of tobacco smuggling with internationally coordinated and unambiguous technical solutions is currently on the international agenda, through work with the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Earmarked funds could be used for this as well.

Justice and equity

•Taxes are a blunt policy tool that reduces the welfare of tobacco users who choose to use these products with a clear understanding of the consequences of their addiction.

Even though the risks of tobacco use are generally understood in some populations, tobacco users are consistently shown to underestimate the extent of risk, which indicates that prevalence is higher than it would be if users were well informed about the risks. Raising and earmarking taxes helps to make risk information more resonant to users, with benefits to youth that are considerably larger than losses to adults.

Health promotion foundations would

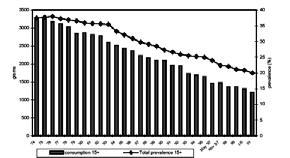

Figure 3 per head tobacco consumption vs smoking prevalence

ensure that earmarked taxes are used for health promotion programmes to reduce health inequalities. Earmarking can be consistent with an overall system of taxes and transfers that promotes equity as many of the activities funded by earmarked tobacco taxes significantly reduce the welfare losses resulting from tobacco tax increases (Hu et al, 1998). Smoking is harmful to health, leading to increased health care costs, placing a burden on all, including non-smokers.

•Governments may be reticent to increase taxes on alcohol because they fall not only on abusers but light drinkers who do not abuse alcohol and do not need to be discouraged from drinking.

Alcohol price increases reduce alcohol morbidity, mortality among drinkers, even light drinkers, and reduce adverse social events related to abuse that are a burden on all of society. Raising alcohol taxes produces benefits that are much superior to the costs.

Economic issues

•If tax increases for earmarking reduce consumption of tobacco, this would bring about job losses creating an extra burden on society.

While jobs directly related to tobacco growing and manufacturing would decline, the impact on employment in other sectors would increase, as exsmokers spend their money on other goods and services, with the net macroeconomic impact of higher tobacco taxes being negligible or positive.

•The amount of funding provided by earmarking could be inappropriate in relation to changing social environments or economic conditions and distort government spending

Even if there is earmarking, politicians can intervene. In Australia and California, large tax increases led to capping of funds available for health promotion from earmarking (but this did create some budgetary instability). Overall, earmarking reduces budgetary fluctuations in the long term. In Australia, the current system of annual review with indexation at around yearly cost of living increases means that continuous and substantial funding is available from consolidated funds for health promotion. In California in the early 1990s, the budget for health promotion was the equivalent of 25% of tobacco industry spending. After government intervention capping revenues attributed to tobacco control, the equivalence dropped to 12% (Sung et al, 2005). This is nevertheless a considerable amount of money that would not have otherwise been available for tobacco control.

Creating and running health promotion foundations: best practices and lessons learned

Health promotion foundations do not have to be funded by earmarked taxes. But, where these do not exist, there is usually little impetus to create and assure funding for them despite universal agreement “in principle” with the concept. But if policy-makers can be persuaded by the arguments for raising taxes for earmarked funds, this is probably the best guarantee that a health promotion foundation will be funded.

This section will look at some of the important issues relating to the creation and funding of health promotion foundations.

Finances

In Australia, tobacco tax collections have continued to increase over time, despite prevalence decreasing and prices increasing. However it is important that the price of tobacco is indexed and adjusted to the consumer price index. Health promotion foundations in Australia are now funded by direct allocation from consolidated revenue, at rates similar to capped hypothecated funding indexed to inflation. A fixed rate from taxes for funding is better than a ceiling: VicHealth’s budget dropped as ceilings on funds from earmarking were changed. There is always the potential for politician interference, but whatever the conditions of earmarked funds, they tend to be better than general government allotments.

Allocations can be earmarked. At VicHealth, 30% of funds are used for sports promotion, 30% for health promotion. Priority is given to fight health inequalities for indigenous people, rural communities, the impoverished and the disabled, through cultural activities as well as health promotion.

According to the International Network of Health Promotion Foundations, Health Promotion Foundations must be created through specific legislation that specifies the long-term recurrent funding mechanism and administration of funds. They should be set up to distribute funds for health promotion. They should be overseen by an independent Board that represents all stakeholders; but the organisation should be able to exercise a high level of autonomous decision making. The Health Promotion Foundation would have an obligation to be non-partisan and to work with other sectors and organisations at all levels of society (Phipps R, 2003).

Goals

Health promotion foundations generally allocate funding for health promotion programmes, tobacco prevention programs, health promotion and prevention research, replacement of tobacco and alcohol sponsorship, and services for smokers and problem drinkers. Earmarking makes sustained, sophisticated, public and school health promotion and education campaigns feasible. In Australia, the Health Promotion Foundation model was developed to replace tobacco sponsorship in light of new bans on tobacco advertising, and support for tobacco control strategies also in light of new legislation; secondary to this, additional funding was secured for health promotion and research. Health Promotion Foundations would be the most apt source of programmes to reduce health inequalities.

Lessons learned

The experiences of VicHealth (Carol A, 2004; Sheehan C & Martin J. private communication) and Healthway (Cordova S. 2003) in Australia, ThaiHealth (Siwraksa P) in Thailand and the Korean Health Promotion Fund (Nam EW, private communication) show that earmarking of health promotion foundations or funds can greatly improve the health promotion activities in a country. They were created after intense and long-term effort from health promotion advocates. Here are some of the lessons learned in advocating for earmarking tobacco (and alcohol) taxes for health promotion funds or the creation of a health promotion foundation.

•The Finance Ministry, in particular, needs cogent logic on the economic benefits and public health good of raising and earmarking taxation. •An extensive community support network should be created, with high profile, articulate spokespersons, probably already part of bureaucracy.

All actors should have agreed and common goals. •Evidence should be available of the expected positive effect on health and the cost-benefit effectiveness of those effects in the local context. All expert information should be readily available. The main message is always that the extra tax will protect the community and strengthen public health. •Surveys should be undertaken to show public support for the initiative. •Draft legislation should be prepared, including the exact mechanism for collecting the levy and for managing it. •Lobbying should involve arguments to

convince the government that it must act, that such action is a bi-partisan, visionary step that will mark history. •It is important to find common ground with those who might have economic losses, e.g., those who would lose tobacco sponsorship. Proponents of

VicHealth stressed its goal of using funds to replace tobacco advertising and were thus able to win over potential adversaries. •Lobbying activity should keep the time period short, for the tobacco industry has money and will use it to subvert support if given the time. •ThaiHealth followed the model of

VicHealth, feeling it was a more flexible and adaptable structure with legislative backing and a guaranteed source of income so as not to have to fight for its budget each year. •From the experience of lobbying for

ThaiHealth, it is suggested that a twostep process may be useful: first get cigarette tax increases, then go for earmarking for a health promotion foundation. •The basic context of the creation of a

Health Promotion Foundation has been seen to be strong leadership, stable government and a commitment to health. Evaluation once in place is essential for continued support •There is a danger in the Master

Settlement Agreement approach: direct agreement with the tobacco industry meant that there was no restriction on the tobacco industry’s ability to promote tobacco products; in 2001 in the US, the tobacco industry spent $11.2 billion on advertising, the effect of which partially offset the effects of the higher prices. •Alcohol taxation issues appear more complex than those for tobacco. While reducing consumption, they may not generate excess revenue. If large alcohol tax increases are politically unacceptable, one approach could be a progressive application of tax according to the amount of alcohol in the purchased item. (Ford, 2004) •Other information concerning creation and administration issues is available from the Health Promotion

Foundations Network (http://www.hpfoundations.net).

Conclusions

Price policy can be an important part of tobacco and alcohol control. The

evidence is strong that the use of tax for health promotion and disease prevention produces public good. Effects on health promotion from earmarked taxation are higher than for taxes alone and are an important tool to promote public health. This could be even more widespread and equitable if used in the context of a health promotion

References

Carol A. The Establishment and Use of Dedicated Taxes for Health. WHO Western Pacific Region. 2004. Chaloupka FJ, Grossman M, Saffer H. The effects of price on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Res Health 2002; 26:22-34. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh261/22-34.htm

Chaloupka FJ, Hu T, Warner KE, Jacobs R, Yurekli A. The taxation of tobacco products. In Jha P, Chaloupka F (eds). Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2000; pp237-272. Chaloupka F, Corbett M. Trade policy and tobacco: Towards an optimal policy mix. In Abedian I, van der Merwe R, Wilkins N, Jha P. (eds). The Economics of Tobacco Control. Towards an optimal policy mix. Capetown: Applied Fiscal Research Centre, University of Capetown. 1998; pp129-145. Cook PJ, Moore MJ. The economics of alcohol abuse and alcohol-control policies. Health Affairs 2002; 21:120-133. Cordova S. Best practices in tobacco control earmarked tobacco taxes and the role of the Western Australia Health Promotion Foundation (Healthway). WHO Tobacco Control Papers. 2003. http://repositories.cdlib.org/tc/whotcp/WAustr alia2003

European Report on Tobacco control policy (WHO regional office) WHO European Ministerial Conference for a Tobacco-free Europe 2002. Ford S. letter. Alcohol evidence and policy. BMJ 2004; 328:1202-1203. Guindon GE, Tobin S, Yach D. Trends and affordability of cigarette prices: ample room for tax increases and related health gains. Tob Control 2002; 11/35-43. Hyland A, Higbee C, Bauer JE, Giovino GA, Cummings KM. Cigarette purchasing behaviours when prices are high. J Public Health Manag Pract 2004; 10:497-500. Hu TW, Mao Z. Effects of cigarette tax on cigarette consumption and the Chinese economy. Tob Control 2002; 11:105-108. Hu T. Xu X. Keeler T; Earmarked tobacco taxes: Lessons learned. In Abedian I, van der Merwe R, Wilkins N, Jha P. (eds). The Economics of Tobacco Control. Towards an optimal policy mix. Capetown: Applied Fiscal Research Centre, University of Capetown. 1998; pp102-118. International Network of Health Promotion Foundations website accessed 10/10/2005 http://www.hp-foundations.net/new/ehpf_ earmarking_taxes.html Lav IJ. Cigarette tax increases: cautions and considerations. Revised 2002 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. http://www.Cbpp1\data\media\michelle\postin gs\7-3-02sfp-rev.doc Ludbrook A, Godfrey C, Wyness L, Parrott S, Haw S, Napper M, van Teijlingen E. Effective and cost-effective measures to reduce alcohol misuse in Scotland: A literature review. Scottish Executive, 2001. For the final report: http://www.alcoholinformation.isdscotland.org/ alcohol_misuse/files/MeasureReduce_Full.pdf Mohler-Kuo M, Rehm J, Heeb JL, Gmel G. Decreased taxation, spirits consumption and alcohol-related problems in Switzerland. J Stud Alcohol 2004; 65:266-73. Phipps R. Report on the 3rd Meeting of the International Network of Health Promotion Foundations, Budapest, April, 2003. Ranson K, Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Nguyen S. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco-control policies. In Jha P, Chaloupka F (eds). Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2000; pp427—447. Sindelar J, Falba T. Securitization of tobacco settlement payments to reduce states’ conflict of interest. Health Affairs 2004; 23:188-193. Siwraksa P. English version translated by V. Isarabhakdi. The Birth of the ThaiHealth Fund (published by ThaiHealth) http://www.thaihealth.or.th/en/download/TheBi rthOfTheThaiHealthFund.pdf Sung H-Y, Hu T-W, Ong M, Keeler TE, Sheu M-L. A major state tobacco tax increase, the Master Settlement Agreement and cigarette consumption: the California experience. AJPH 2005 95:1030-1035.

Wilson N, Thomson G. Tobacco taxation and public health: ethical problems, policy responses. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61:649-59. Wilson N, Thomson G. Tobacco tax as a health protecting policy: a brief review of the New Zealand evidence. NZ Med J 2005 118:U1403.

foundation. Earmarking additional tax revenues for the creation and funding of a health promotion foundation will create the means to implement a full arsenal of programmes for the public good and to fight health inequalities. The various experiences of creating health promotion foundations from earmarked taxes converge on these points. It takes solid data, perseverance and long-term planning. There will be set-backs and opposition from not only the tobacco (and alcohol) industry, but other sectors of society. Misperceptions will need to be dispelled regularly. But the potential health benefits for society are enormous and make the endeavour well worth the effort.