200 minute read

BILAG

Studie I

I dare to be myself. The value of peer communities in adapted physical activity interventions for young people and adult people with cerebral palsy

Andersen, M.M. & Winther, H. Submitted to: Clinical Rehabilitation

Studie II

Moved by Movement. A phenomenological study of how young people and adults with cerebral palsy experience participating in the challenging adapted physical activities at a sports camp

Andersen, M.M. & Winther, H. Submitted til: Journal of Sport and Development

Studie III

You learn to believe more in yourself. Experienced development processes after attending a resilience-based sports camp for young people and adults with cerebral palsy

Andersen, M.M. Anmodning om publicering i en special edition i: Disability and Rehabilitation.

Studie IV

The Red Zone – The psychology of significant mastery experiences. A grounded theory study based on challenging and adapted physical activities

Andersen, M.M. & Winther, H. Submitted til: New Ideas in Psychology.

Studie I

Camp is freedom for me. Huge freedom. Because I am together with people who are a bit like me. They are in the same situation and can’t make their arms and legs do as they like. It has just been so great. (…) I feel more comfortable with myself in some way. You dare to show who you are. I might be a little shy, but when I'm with you, it's actually not that bad.

I dare to be myself The value of peer communities in adapted physical activity interventions for young people and adult people with cerebral palsy

Mie Maar Andersen¹ ², Helle Winther³

1 Elsass Foundation, Charlottenlund, Denmark 2 Department of Neuroscience, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 3 Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Keywords

Disability Social community Sports camp Peers

Rehabilitation

Corresponding author:

Mie Maar Andersen Elsass Fonden Holmegårdsvej 28 DK - 2920 Charlottenlund Mail: mma@elsassfonden.dk Phone: (+45) 30489048

I dare to be myself The value of peer communities in adapted physical activity interventions for young people and adult people with cerebral palsy

Abstract

Research literature has shown that being a part of a disability peer community are highlighted as one of the most motivational and meaningful aspects in many adapted physical activity settings. Nevertheless, this focus is seldom found in the predominant rehabilitation intervention strategies and recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. This study investigated how people with cerebral palsy experience being a part a community with equal peers at a four-day resilience-based sports camp. Two semi-structured interviews with 16 participants from four of the camps were carried out. The first interview aimed at getting a sense of the participants and their life situation, and the second at getting a sense of their experiences at camp. We identified social dimensions that encouraged the participants to believe in themselves, dare to be vulnerable and participate in challenging activities. These dimensions included an experience of belonging, social security, empowering group-synergy, symmetry in perceived abilities, a sense of being a resource and a feeling of being seen and understood. The findings indicate that a community with peers can improve the self-perception and situated participation of young and adult people with cerebral palsy. Therefore, future clinical

recommendations and strategies for people living with cerebral palsy could consider including this aspect.

Keywords: Disability; Sports camp; Peers; Social community; Rehabilitation

1. Introduction

This paper proposes that healthcare systems would benefit from an increased understanding of the meaning and value for young people and adults with cerebral palsy of being a part of a peer movement community. This might enable healthcare systems to better integrate social dimensions into intervention and rehabilitation strategies and guidelines for young people and adults with cerebral palsy. In this paper we elucidate how young people and adults with cerebral palsy (CP) experience being a part of a peer community at a four-day sports camp for people with CP. Furthermore, we discuss how peer communities can enhance a rehabilitation process.

Research literature reports that being a part of a disability peer environment and community is one of the most motivational and meaningful aspects in diverse movement settings. In a systematic review, Powrie et al. (2015) investigated the meaning of leisure activities for children and young people with disabilities. All the included studies reported the importance of social themes consisting of friendships, feelings of belonging and social connectedness as a positive factor in meaning creation for children and young people with disabilities. Furthermore, the study concludes that “Friendship, being with others, and a sense of belonging to a social group often seemed to be more important to CYP [children and young people] than the leisure activity itself” (Powrie et al., 2015 p. 1006-1008). The study also emphasizes the value of segregated settings such as camps, as they provide a special sense of connectedness with others with disabilities (ibid.). In this regard, Standal & Jespersen (2008) focus on the learning potentials associated with being in a peer community in a rehabilitative movement camp setting. In the study the most prominent finding is that the participants learn a lot by observe and model each other. Furthermore, it is valued in the learning situation that the peers truly understand each other. Finally, the discussions, negotiations of meanings, and shared experiences in the group of peers helps the participants forming a realistic interpretation of their possibilities in everyday life. In other camp studies the value of the peer element is highlighted too. Thus, Dawson & Liddicoat (2009) describe the experiences from a summer camp for adults with CP and found that being a part of a supportive community was the most prominent theme. Many of the participants described the camp and the other members to be like a loving home and a family that had great respect for each other. Such a sense of belonging, respect and acceptance caused by shared life experiences and a deep understanding are seen in several other studies that investigate the experience of being at a camp for people with disabilities (Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Michalski et al., 2003; AshtonShaeffer et al., 2001; Nyquist et al., 2019; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017; Goodwin et al., 2011; McAvoy et al., 2006; Devine and Dawson, 2010; Devine et al., 2015). In some of these studies, other elements of the peer community are also emphasized. Thus, a common finding is that being in a peer community at camp helps the participants expressing one’s true self and additionally develop an empowered sense of self (ibid.). This perspective is in Nyquist et al. (2019) and Goodwin et al. (2011) linked to being able to help and teach others. In other studies, this perspective is related to a sense of not being an outsider (Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Goodwin et al., 2011) and from speaking with and observing peer participants (Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Goodwin et al., 2011; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017).

Despite the many benefits of peer movement communities for people with disabilities, such communities are seldom built into the predominant intervention strategies and recommendations for people with CP (Novak et. al., 2013; Wang & Yan, 2018, Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2014). The absence of peer movement communities may be linked to the most used definition of CP, and to traditions in the health care system. Cerebral palsy is defined as “a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain.” (Rosenbaum et al, 2007, p. 9). This definition refers to limited motor functions as the main adversity and as the main explanation for activity limitations. This correlation between physical factors and human behavior is reflected in clinical practice, guidelines and strategies for rehabilitation and treatment of CP in the health care system (Novak et. al., 2013, Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2014). For treatment and rehabilitation in relation to CP, the most used methods in the health care system are standard physiotherapeutic and occupational training and therapy, orthopedic surgery, and antispastic medical treatment (Wang & Yan, 2018). These interventions rest on the hypothesis that the improved motor control and function provided by such methods leads to better functioning (Barnes, 2001). This concept of functioning stems from the definition in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) created by the World Health Organization (WHO), and includes a person’s body structure and anatomy, activity, and participation (ICF, 2001). Despite this correlation between motor function and functioning, research has shown that improvements of physical aspects do not have a strong clinical effect on participation and activity in daily life (Sheean 2001; Pandyan et al. 2005; Aisen et al. 2011, Novak, 2013). This indicates that improvements in physical functions can be beneficial to some extent, but cannot alone accommodate the complexity related to living with CP. According to Martiny (2015), psychosocial challenges related to people with CP, such as fundamental bodily uncertainty rooted in self-doubt and pervasive social anxiety, also need to be addressed. If we recognise that the functional challenges of people with CP are grounded in both physical and psychosocial factors, we need intervention strategies that address and accommodate both groups of factors. To better understand how these factors can be helpful in rehabilitative practice, this paper aims to gather more insights on the meaning of peer communities at a camp for young people and adults with cerebral palsy. Furthermore, we discuss how dimensions of the peer community can provide benefits in a rehabilitation context by reflecting on theories that link social and environmental

factors with how people behave and become motivated (Deci & Ryan, 1985;2000; Bandura, 1977;1995;1997; Goffman, 2009; Smith & Sparkes, 2006).

1.1 Theoretical background

Deci & Ryan’s (1985; 2000) Self-Determination Theory (SDT) describe what makes people thrive, and what motivates people to explore the world and seek interaction and fellowship with the outside world. They conclude that three basic psychological needs must be fulfilled for people to thrive and be motivated for the activities they are involved in. These are the needs to experience autonomy, competence and relatedness. That is, a person needs to experience a degree of free will and personal initiative (autonomy) to manage the tasks they meet (competence), and to experience community and fellowship with others (relatedness). The third psychological need, relatedness, is central to our perspective in this paper. Another relevant theoretical point is Bandura’s (1997) concept of self-efficacy. This concept is “(…) concerned with how people judge their capabilities and how, through their self-percepts of efficacy, they affect their motivation and behavior.” (Bandura 1982, p. 122). Expectations of selfefficacy can thus determine whether a person will be able to exhibit coping behavior and how much effort they will put into the process. A high level of self-efficacy will typically motivate someone to make a sufficient effort and create potential for success, whereas people with low levels of self-efficacy often be demotivated and cease efforts early and fail. A high level of selfefficacy will thus potentially stimulate more active and engaging behavior in people with CP. In a social and environmental perspective, Bandura states that self-efficacy is highly influenced by the social relations we interact with and are surrounded by. Besides the importance of having mastery experiences and positive affective/physiological feedback, Bandura (1997) also proposed two social factors that people look at when evaluating their levels of self-efficacy – vicarious experiences and verbal persuasion. Vicarious experience refers to learning through observations of the actions of others. A related point is that observing a person who successfully engages in an activity is more likely to increase self-efficacy, if the person is perceived as being similar to the observer – especially in cases where other personally salient barriers are similar, e.g., if a chronic condition is shared. Verbal persuasion means that our social relations can strengthen our beliefs in our self. Being persuaded that we possess the capabilities to manage and master certain activities thus means that we are more likely to put in the effort when problems arise. In accordance with Bandura, Goffman’s (2009) theory of stigma focuses on the meaning of being in an environment with ‘like-situated individuals’, who are fellow-sufferers. In Goffman’s terminology, similar persons are referred to as ‘the own’. Furthermore, a group of people who

carry the same stigma is known as an ‘in-group’. This in-group is a group of people who, unlike much of the rest of society, are seen as sympathetic, as they through their own experiences know exactly what it means to be a person who carries the same stigma. According to Goffman, this relationship between relatable people can enhance the creation of a safe environment where a sense of acceptance and understanding can be achieved (ibid.). Such social experiences contrast with many other social situations in which the stigmatized person will often be labeled as different and will feel socially excluded. A further perspective that highlights the importance of social community for our identity and behavior is provided by the two narrative researchers Smith & Sparkes (2006). They argue that environmental input is central to our identity and behavior, as “[…] the stories that people tell and hear from others form the warp and weft of who they are and what they do” (Smith & Sparkes, 2006, p. 169). This means that the stories people with CP hear about themselves will influence their self-stories and direct their actions. A social community that tells empowering stories can thus potentially stimulate more optimistic and action-orientated behavior.

2. Method

2.1 Phenomenological approach and method

The present study uses a phenomenological inspired approach to elucidate the meaning of peer communities, as the phenomenological approach allows us to study how people create meaning from their experiences in their lifeworlds (van Manen, 1997;2016; Jacobsen et al., 2015; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003;). In a phenomenological perspective, the lifeworld represents the individual’s subjective way of perceiving and being in the world. The lifeworld in focus in this paper is the world the participants experience in a first-person perspective when participating in the peer community at a sports camp. This approach is chosen for four reasons. First, this study wishes to shed light on the underprioritized area of peer communities in interventions for people with CP. Second, a qualitative descriptive approach can help us understand the significant nuances in peer communities that can influence interventions. Third, this study wishes to give a voice to the people with CP, and hereby an insight into how the participants experience being a part of a peer community when participating in a sports camp. Finally, the phenomenological approach can uncover aspects of peer communities that researchers have not been aware of before. As Van Manen (2016) states “Even the most ordinary experience may bring us to a sense of wonder” (p. 31). Such insights

can hereby lead to new perspectives that can broaden our understanding of how interventions in the health care system can be strengthened. With these elements in focus, this study can bring new insights on how peer communities can be of value when living with CP.

2.2 Context - sports camp

The context of this study has been four separate 4-6-day long sports camps for people with CP developed and arranged by the Elsass Foundation of Denmark (Andersen, 2016). The Elsass Foundation offers camps for people with CP in the age range from 5 – 60+ years and with different levels of disability. The participants are gathered at different camps in relation to age and level of physical ability. In this study, we have included four camps, which are presented in Table 1.

Participants Location

Camp 1 20 Elsass Foundation

Camp 2 16 Elsass Foundation

Camp 3 11 Egmont Folk Highschool

Camp 4 10 Club La Santa Table 1. The four Elsass Foundation camps included in this study

Age

10 - 13 14 - 18 10 - 17 30 - 60

Condition

Able to walk Able to walk Using wheelchair Able to walk

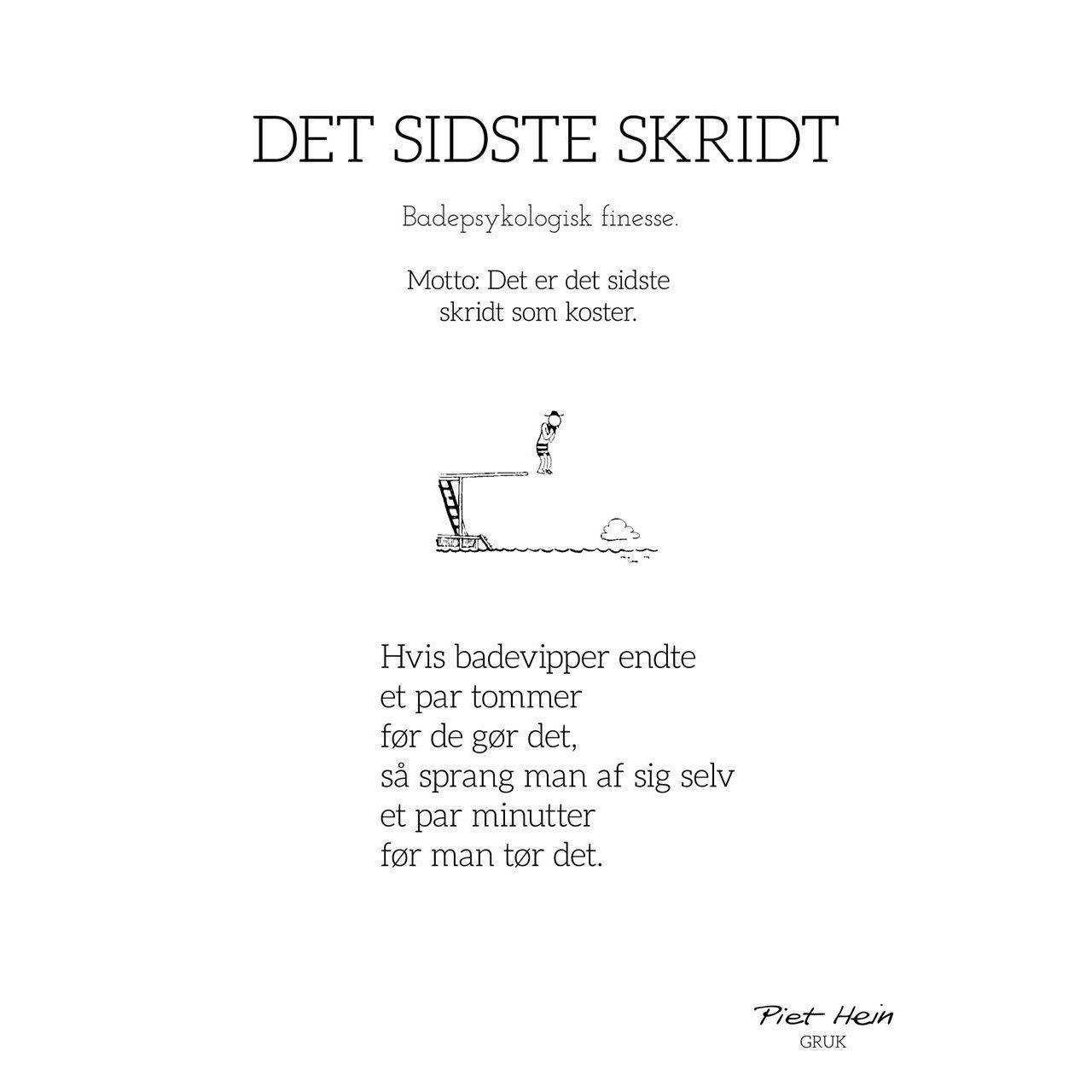

Despite a great range in age and physical abilities, all camps are basically designed in the same way. All camps include accommodation, the participants share rooms with one to three other participants, everybody participates in all meals and follows the same activity program. The location of the camps differs, and each participant at the camp for wheelchair users is accompanied by their private helper. The activity program can differ from camp to camp but follows the same structure. This structure builds on three models of psychological resilience (the protective, compensatory and challenge models) (Garmezy et al., 1984; O’Leary, 1998; Borger, 2010). First, there is a focus on social games and teambuilding activities, to create a good trustful atmosphere and help the participants get to know each other (protective model). Second, the participants are presented with different activities such as martial arts, stand up paddle board or trampoline, to let them experience that they can participate and manage in many activities as long as they have a flexible and creative mindset (compensatory model). Finally, the participants are presented with adventure activities such as climbing, kayaking or jumping from a diving board in the swimming pool (challenge model). These activities aim to challenge the perceived abilities of the participants.

Confrontational and successful experiences that can have the potential to (re)frame their perspective on themselves and their possibilities. In addition to the adapted physical activities, two group talks are arranged every morning and afternoon. The talks aim to stimulate reflection and create a bridge between the participants’ personal stories, expectations and experiences at camp. For a further elaboration of theoretical and methodological design of the camp see the ‘Camp handbook’ (Andersen, 2016).

2.3 Participants

After the registration period, the professional team that was in charge of the camps reviewed each participant’s information. Four participants at each camp (16 in total) were selected and asked to participate in the study. Every participant chose to accept the invitation and parents and participants more than 18 years old signed a form of consent. The participants were selected to achieve a group that displayed the greatest diversity in gender, age, level of ability/disability and camp-experiences. All 16 participants had cerebral palsy, and 12 of them (camp 1, 2 and 4) were classified as level I and II on the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) (Palisano et al, 2008). This ensured that they could perform gross motor skills such as walking, running and jumping. The last four participants (camp 3) were classified as level III and IV. While two of them could walk with assistance, all used a wheelchair most of the time, and needed support in many activities. The communicative abilities of the 16 participants were very different; levels I – IIII of the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) (Hidecker et al, 2011) were represented among the participants. This meant that some participants spoke clearly, while others spoke slowly and were difficult to understand. In the article every participant is anonymized. The names used in the paper are created by the authors.

2.4 Data creation

All participants engaged in two individual semi-structured interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009; Smith & Sparkes, 2018). The first interview took place a month before camp and focused on the participant’s lifeworld to get a first-person insight on how the participants experience their own lives. In the interview the participants were asked to describe their background, themselves, their interests, everyday routines, social relationships, values and personal resources and challenges. The second interview was a camp-experience interview, held at the latest a week after camp to ensure a fresh memory of the camp. From a phenomenological point of view, we were interested

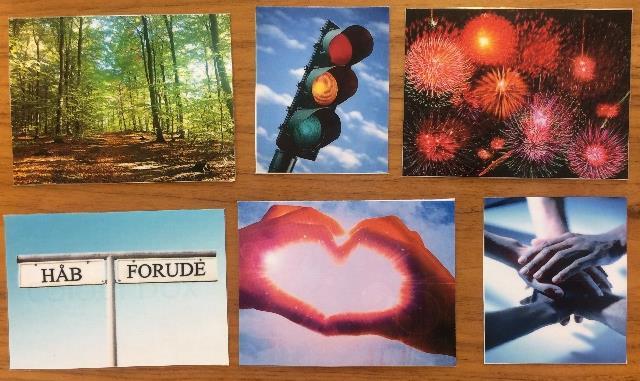

in studying how the participants experienced, perceived and interpreted being a part of the peer community at camp (Jacobsen et al, 2015; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003; van Manen, 1997;2016). When planning the interviews, our personal experience from our previous work with people with CP were taken into consideration. For example, some people with CP find it difficult to reflect in a nuanced manner on open and abstract questions related to experiences and perceptions. To accommodate this perceived challenge, we used coaching cards that displayed many different

kinds of situations, emotions and symbols. The cards were used to help the participants talk about metaphors that described their experiences of the camp, which provided participants with another way to express their feelings and bodily experiences (Stelter, 2012). The cards were used as a bridge for meaning making and understanding between us and the participants, as metaphors are used to understand one thing through another (Miles & Hubert, 1994). Figure 1 shows the cards chosen by one of the participants during an interview. Figure 1. Example of chosen coaching cards

2.5 Analysis strategy

A thematic analysis using the three-step method described by Braun and Clarke (2006) was conducted to identify patterns and key themes in the data. First, all the interviews were transcribed and read to obtain an impression of the data as a whole. Second, the words of the core message of each response were identified and a data-driven code was added. Third, a final reduction was made that grouped all similar initial data-driven codes into key themes that were to represent the essence of the phenomenon “being a part of a peer community at camp”. The themes presented in the following findings section describe how the phenomenon is present for the participants.

3. Findings

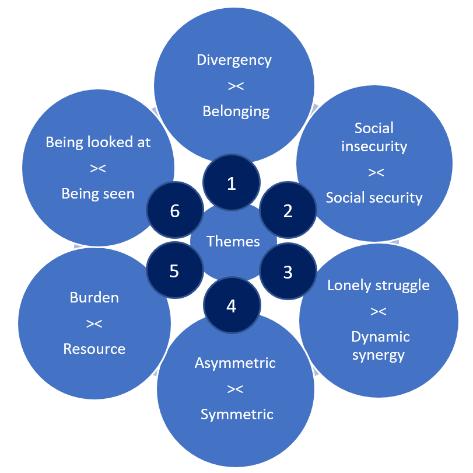

Teenagers in wheelchairs who are laughing and screaming while bouncing into each other in a chaotic ball game, a nervous woman trying to stand up on a stand-up paddle board as her camp-friends support her on both sides of the board, and children cheering for each other when climbing a large wall on an obstacle course – these are all episodes from the sports camps where the social context has been a major part of the experience. In this section we elaborate on how the participants experience being a part of the peer community at camp. Our thematic analysis identified five themes central to the participants’ experiences of the peer community (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The six themes

3.1 Divergency >< Belonging. ‘You don’t have to adapt – you already fit in’ Most of the participants experience themselves as someone who diverges from the norm at school or at work. A role and position in society which many participants connect with either their struggle to try to fit in or their struggle to explain themselves to their surroundings. At camp this is different. At the camps, they found themselves among peers. This gave them an experience of belonging, which Margrethe (42 years old) expresses as: At camp you don´t have to adapt – you already fit in, because that is how it’s made. In everyday life you must adapt all the time. In contrast to the participants’ everyday life, the divergent component, CP, is what makes them fit in at camp. Using a metaphor of a gospel choir, Amanda (30 years old) describes this condition of belonging as:

I have taken a picture of a gospel choir that just goes completely crazy. They are in the same jerseys and that kind of shows what I feel the camp is for me - unity and equality somehow. There isn’t anybody who is violently sticking out of the crowd, and if we do, we all do it together. And it may well be that one doesn’t follow the beat completely, and it may well be that one sings a little false, but when you are enough, no one will ever notice.

What Amanda is indicating in the quote above is a paradox about experiencing being similar and equal as a result of total divergence. Everybody is different, nobody is following the exact same beat, but that is exactly what stimulates the great harmony. If everybody is different, nobody stands out alone. This element affects many of the participants in very valuable ways, as several connect the feeling of belonging with a sense of social security. A sense of social security, which will be elaborated in the following theme. Nevertheless, one experience by Mathilde (16 years old) was very different from the others. Mathilde was at one of the camps the only girl who did not know any participants prior to the camp. This made her feel alone, uninteresting and ignored by the other girls. At the end of the four days, Mathilde felt she had become a part of the group, but it is worth noticing that she felt: it could be a little tough to be there.

3.2 Social insecurity >< Social security. ‘You dare to show who you are’ Many of the interviewed participants describe how they often take a passive role in social contexts because they feel shy, insecure, left behind or find that this is what is expected of them. An example of this is Paul (60 years old), who struggles with insecurity related to talking because of his speech impediment. He explains that he gets nervous when speaking to people he does not know, and even at family parties rarely speaks. Nevertheless, he finds the courage to show his most vulnerable side at camp. He dares to speak up and even gives a talk in front of the entire group about his life — a performance he credits the social security: you feel so damn safe here.

The feeling of social security and support that gives many of the participants the courage to be vulnerable is closely connected to a sense of freedom, which the participant Sofie (16 years old) described as:

Camp is freedom for me. Huge freedom. Because I am together with people who are a bit like me. They are in the same situation and can’t make their arms and legs do as they like. It has just been so great. (…) I feel more comfortable with myself in some way. You dare to show who you are. I might be a little shy, but when I'm with you, it's actually not that bad.

We can see that the theme of social security is central to Sofie’s reflections when she uses the word “dare” when she describes showing who she is. This suggests that she, like Paul, experiences how a feeling of social security stimulates social courage. In addition, it may indicate

that she usually hides and limits herself. For both Paul and Sofie, social security sets them free and stimulates a more authentic and engaging behavior in contrast to how they both describe their usual more unsociable passive behavior. The experiences of Paul and Sofie are representative for many of the participants, but not all. Despite everybody mentioning the unity of the group as unique, secure and valuable, three of the teen boys did not find themselves being braver than they were used to. They appear as confident, talking about believing in themselves and having a good social community at home. For them the camp is a good experience, but they do not describe it as significant for them in their personal development.

3.3 Lonely struggle >< Dynamic synergy. ‘Ten individuals and then we just become one’ A common reflection from the everyday lives of the participants is an experience of being alone with their struggles. In this context, the symbol of the holding hands, which was chosen by 13 out of 16 participants, is interpreted by the participants in a more dynamic way. The holding hands do not exclusively reflect social security but becomes a metaphor for a unit that collaborates closely and creates the energy and synergy to lift and push the participants to another ability level. As Margrethe (43 years old) explains:

Together we are stronger and can do virtually anything. (…) That's how it is when you are in a community where you feel like you are one, even if you are ten. Perhaps you can really say it like that - ten individuals and then we just become one.

The synergy of the group as a unit working together is described by many of the participants as crucial for the things they accomplish and manage at the camp. The synergy creates a significant group strength that influences the participants’ actions and belief in themselves. Margrethe reflects on the meaning of the group in relation to the time after camp as follows:

Well actually, there is also a great contrast. Because you get the feeling that you can handle the whole world, but at the same time the world becomes very big when you come home again. Suddenly you stand alone. So, if you are in a challenging situation, there is nobody to give a high five and say, "you can do it".

This statement from Margrethe indicates that the loneliness struggle back at home may be perceived as even bigger than before engaging in the camp. This perception is grounded in the experience about how struggles and challenges can be managed differently than she used to

manage them. In addition, the perception leads to frustration because she cannot transfer the feeling of unity to her everyday life. Nevertheless, Margrethe concludes that she (in accordance with many of the other adults with CP) identifies the other group members as her CP family, and she would not miss that for the world.

3.4 Asymmetric >< Symmetric. ‘If they do it, I can do it too’ Some of the participants attend special-needs schools that cater for people with disabilities, but most school-age participants attend normal schools. Attending a normal school leads to many participants experiencing an asymmetric relationship between their own and their school peers’ abilities. This asymmetry and confrontational comparison cause self-doubt and limits the social life of people with CP, as many of them opt out of physical education classes and active breaks during the school day. At camp, this is different, which Oliver (14 years old) reflects on:

It is much easier to do things together because we are at the same level. You can easily play games, run and play soccer because people have the same problems as yourself.

The experience of being able to participate as a result of the same ability level is shared by all participants. Furthermore, this symmetry in abilities seems to have an additional valuable affect when participants find themselves in a challenging situation. This is described by Oliver when he recounts an experience from the climbing track:

That was why I signed up to be in the back of the climbing track. Because it always gives me some inspiration when I see how the others do it. It helps me a lot. Because if they do it, I can do it too.

This statement shows that a challenge managed by the others is experienced as transferable to Oliver’s own perceived abilities. It creates a belief in himself as a result of a mirror effect, which is an effect he does not benefit from in his everyday life where he perceives himself as less capable in relation to his classmates. This enhancement in perceived abilities and readiness to participate caused by a mirror effect are reflected in many of the stories, the participants tell about their experiences in the challenging adapted physical activities.

3.5 Burden >< Resource “I can make a big difference” While many of the participants are the ones who need the most help and adjustments in their everyday lives, they find that the symmetry in their camp relationships changes their social position. Suddenly they do not only get help, they are also in a position where they take responsibility and offer their help to the other participants. This reciprocal relationship prompts Margrethe (43 years old) to say: “Here [at camp] is someone who needs you. I can make a big difference, and I think that is great.” This is a feeling of being needed, contributing to the other participants’ victories and making a difference, which both have an effect in terms of a self and relational reward. Thus, helping others is described as valuable for the self, as Paul (60 years old) says: “when I give five cents, I feel I'm getting a million back”. Furthermore, the stronger relational bond between the helper and the one receiving help is described by Catharine (13 years old):

(…) we [Catharine and another participant] were not that close before that incident where we wanted to jump [from the stool in the swimming pool] and I thought “Okay, we have to help each other”.

The statements from Paul and Catharine indicate that being a resource for other people, can both positively affect the self-feeling, and additionally stimulate stronger relational bonds between the helper and the one who gets help.

3.5 Being looked at >< Being seen. ‘That deep deep understanding’ Another consequence of being the only one with a disability, is the feeling of not being able to share common bodily lived experiences. Amanda (30 years old) describes this perspective as:

People in my everyday life are very kind to respect when I say how it is and what I feel, but it is not that they know it themselves. Or “we have also tried…” or “we have seen others who also…” or something. There is never really anyone who has seen it, done it or tried it before in my everyday life, but at camp there are. You as leaders of the camp have seen it many times before. You have seen the patterns and experienced the reactions, but the other participants have tried something similar before, and that is cool.

While Amanda experiences the respect and sympathy of the people she is surrounded by in her everyday life, she still experiences a distance between herself and them, because they lack experience with people who are living with CP. At camp this is different. Here she meets

professionals who have an academic and practical knowledge of CP that creates an understanding between them. Nevertheless, she experiences the relation to her peers at camp as the most valuable relation, because of their shared lived experiences and deep understanding. These experiences are described by many of the participants as meaningful in relation to mainly three aspects. First, being able to have a dialogue about everyday circumstances with somebody who can reflect on matters in relation to their own lived experience are perceived as very beneficial. When the other participants have the same story and experience, such dialogues make them feel mutually understood and affiliated. In addition, these dialogues allow the participants to ask questions, get advice and share recommendations.

Second, a shared humor is mentioned as a thing that makes the atmosphere more joyful. This is an intra-group humor that hinges upon common struggles and misunderstandings that are turned into a shared inside joke, instead of a serious mistake or failure that should be pitied. Finally, the deep understanding between the participants, causes the them to accept and understand each other without any explanations. This is in great contrast to when the participants are among people without disabilities. Here they describe how they often feel observed and forced to explain or legitimize themselves and their struggles. This understanding makes the participants feel that the relationship between them and their peers at camp is strong and heartfelt. In addition, this understanding makes many feel relaxed about their circumstances at camp.

We noted that the participants who participate in sports associations for people with CP have experienced this symmetry in ability level and lived understanding before. An example is given by Christopher (10 years old), who compares the reciprocal relationship at camp with his soccer

team:

Well I've tried it before. That's how it is when I go to soccer. There we also struggle a bit more than others. (…) You feel like you understand each other and so.

4. Discussion

Our analysis showed that the camp comprised two social dimensions that were valued by the participants. One dimension was the sense of a unique unity. The other was the sense of a reciprocal relationship between the participants.

We will discuss our findings in relation to the two social dimensions ‘the value of the unique unity’ and ‘the value of the reciprocal relation’, and elaborate on how knowledge of these dimensions can be beneficial for designing and implementing rehabilitation interventions and

programs.

4.1 The value of the unique unity

The value of the unique unity is described by the participants as a sense of belonging, security and synergy. This is a new social community that makes them behave, act and participate differently. This change in behavior is a key effect of the camps, and reveals a connection between the participants’ social community and the way they act. We believe this connection can be understood by looking at aspects presented by Goffman (2009) and Ryan & Deci (2000). When referring to Goffman’s (2009) theoretical framework, the participants’ central experiences of a sense of security and relatedness, make good sense. Thus, their experiences can be explained by the construct of an in-group of participants who relate to each other as fellow-sufferers. A group construct, which according to Goffman is the one to which the individual naturally belongs and find comfort. This sense of belonging and comfort is not only seen in this study, but is also seen in many other camp studies (Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Michalski et al., 2003; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Nyquist et al., 2019; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017; Goodwin et al., 2011; McAvoy et al., 2006; Devine and Dawson, 2010; Devine et al., 2015). How these social experiences furthermore can influence the way the participants act and behave can be elucidated through Ryan & Deci’s Self Determination Theory. Here they expand on how human nature can be described in a variety of ways that reflect how an individual reacts to their social community:

“The fact that human nature, phenotypically expressed, can be either active or passive, constructive or indolent, suggests more than mere dispositional differences and is a function of more than just biological endowments. It also bespeaks a wide range of reactions to social environments” (Ryan & Deci, 2000 p. 68)

In a further elaboration of the influence of the social environment, Ryan & Deci states that people are more likely to be motivated, engaged and to act “[…]in contexts characterized by a sense of security and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 71). These social motivational aspects indicate

that the participants at camp do not act differently because they become something more, better, or extraordinary. At camp, they simply just dare to become and show who they already are. They experience development and growth because they dare to be vulnerable and let go of their avoidance behavior. They become a brave version of themselves that makes them engage and take risks. This approach unfolds their potential and leads to successful actions, an enhanced selfperception and inner power they can bring back home. The same causality between social security and being brave enough to act despite fear of failure is also presented in Nyquist et al. (2019) and Goodwin et al. (2011). This suggests that rehabilitation programs should focus on establishing a peer community that stimulates a sense of social security so that participants dare to open up and place themselves in perceived risky situations. This focus on social environmental factors correspond with several other studies that too highlight these elements as important for participation (Anaby et al., 2014 Maxwell et al., 2012; Steinhardt et al., 2019; Colver et al., 2012). Thus, we propose paying more attention to the causality between social security and participation. This view on causality stems from what (at the sports camp) is perceived as the primary obstacle to participation. Many cases from the camp thus indicate that what mostly impedes the participants is not a lack of motor functions that makes them unable to act, but that a lack of motor functions makes them too uncertain to act. Nevertheless, they find the courage to confront this uncertainty when they have the appropriate social support and security. This feeling of belonging and the effect of the powerful group synergy described by participants indicates that teams of peers can form a valuable part of a rehabilitation program. Nevertheless, we should be aware that the four-day camp may not be the best way to structure the intervention, if it stands alone. Even though the four days seem to affect the participants in very meaningful ways, the findings also indicate that the time after camp can be challenging and lonely. In this sense, the power of the unity can backfire and cause emotional pain if there is no transfer of this power to the participants’ everyday lives. This indicates that camps have great potentials but should be complemented and followed by more continuous programs and interventions that form a more structured part of the participants’ daily lives – in the same way as traditional physiotherapy and occupational therapy can be available on an ongoing basis.

4.2 The value of a reciprocal relation

The findings presented in the last three themes show how relationships can affect the way we perceive ourselves and how we act. The participants describe significant relationships that are

different to the relationships in their everyday lives. This difference stimulates a new perception of themselves, their abilities and disability, which is interesting to discuss in relation to the theory of self-efficacy presented by Bandura (1977; 1995;1997) and narrative thinking presented by Smith & Sparkes (2006).

Perceived self-efficacy refers to beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations. Efficacy beliefs influence how people think, feel, motivate themselves, and act. (Bandura, 1995, p. 2)

With this definition in mind, a strong sense of self-efficacy is crucial for people to develop a life in which they actively take charge and make the choices and decisions they find meaningful. Four main factors influence how people perceive their self-efficacy: (1) Mastery experiences, (2) vicarious experiences, (3) verbal persuasion and (4) emotional arousal (Bandura, 1977). In relation to the social themes identified in our analysis the factor ‘vicarious experiences’ is the most relevant. The power of vicarious experiences comes from the idea that “Seeing people similar to oneself succeed by sustained effort raises observers' beliefs that they too possess the capabilities [to] master comparable activities to succeed.” (Bandura, 1994, p. 3). Unfortunately, in the participants everyday lives, this factor has either been absent, or have stimulated the participants’ self-efficacy beliefs in an unfortunate way. In contrast, many participants at camp talk about how they find the courage and belief to act by observing the other participants act. “If they can do it – so can I” is a common phrase used by the participants, which indicates that the success of their peers is interpreted as transferable and hereby enhances their self-efficacy beliefs. This beneficial effect of observing peers was also one of the most prominent themes in the study by Standal & Jespersen (2008). Furthermore, this phenomenon is also seen in several other camp studies (Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Goodwin et al., 2011; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017). In accordance with the findings in this study, the former studies also report how modelling of peers can stimulate an increasement in self-perception. Hence the observations of equals can additionally change our self-story. In line with narrative thinking (Smith & Sparkes, 2006) the environmental input can change how we tell about our self. A story which at the camp shifts from “I cannot”-story to a more positive “I can”-story. A change in self-story is also seen in the theme “Burden >< Resource”. The new position as a person who can help others, make some of the participants change the character they occupy in the storyline. In these stories they do not take the place as the “victim” who needs help and support – as they often do in everyday life – but becomes det “hero”, who helps and makes a big difference. 119

Despite a great turn in story a potential challenge is that this story might be limited to the camp setting, if the participants do not have a community of equal peers in their local environment. This indicate that we should develop local rehabilitation programs that allow participants to engage in teams of peers. Such teams should comprise participants of comparable ability levels and should allow the participants a sense of lived connection and understanding, thus allowing them to support each other and benefit from each other’s achievements and hereby develop and grow together.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

A critical point can be connected to the role of one of the researchers, who has been closely involved in the camp and with the participants doing the camp. This means that the participants and the researcher have developed a strong relational, that may result in the participants not being critical in the interviews. Or it may be that the interviews would not have the descriptive depth sought because of a shared camp experience that could motivate the interviewees not to share experiences as they seemed too obvious to the researcher. To accommodate this the researcher began each interview with a briefing that encouraged the interviewees to be honest, critical and tell about their experiences as they would tell them to someone who had no camp experience. Despite these potential limitations there is also an advantage connected to this point. Due to the trustful relationship between the interviewee and the researcher, the experience of the researcher was that the interviews resulted in very detailed and honest descriptions and stories from the participants. Finally, it is a sign of trustworthiness that the unique findings, contributing with new nuances to the use of peer communities in rehabilitation for people with CP, resonate with the research literature presented in the introduction (Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Gill, 1997; Michalski et al., 2003; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Nyquist et al., 2019; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017. This resonance and new findings presented in this article can provide a valuable contribution and furthermore be transferred to other target groups and contexts.

5. Conclusion

We have shown how young people and adults with CP experience being a part of the peer community at a sports camp. The participants describe a very different social community compared to the communities they are used to in their everyday lives. At camp they felt they

belonged instead of being an outsider. This sense of belonging gave them a feeling of social security, an empowering group energy and support, which made them dare to confront many of the challenges they were presented with. Furthermore, the symmetry in perceived abilities, the feeling of making a different and the internal lived understanding of being a person with CP were key factors that enhanced participants’ beliefs in themselves. Our findings indicate that the different dimensions of the peer community can stimulate a stronger self-efficacy and -story and thereby make the participants dare to become and show who they are — a brave version of themselves that makes them engage and take risks. This approach unfolds their potential and leads to successful actions, and an inner power they potentially can take back home. Our findings indicate that a focus on peer communities could be included in recommendations and interventions for people living with CP. Furthermore, our findings also indicate that the camp concept would benefit from a complementary continuous follow-up program or intervention, which could support the participants in their transfer to everyday life. For future research, it would be interesting to explore the meaning of peer communities in regular rehabilitation program for people living med CP.

Acknowledgements

First, we would like to thank all the participants who engaged in this study. Furthermore, we thank you the Elsass Foundation and Innovation Fund for financial support. Finally, would also like to thank Jens Bo Nielsen and Kristian Møller Moltke Martiny for fruitful discussions and feedback on the article.

References

Aggerholm, K. & Moltke Martiny, K.M. (2017). Yes We Can! A Phenomenological Study of a Sports Camp for Young People with Cerebral Palsy. Adapted physical activity quarterly. 34(4): 362-381.

Aisen, M. L. et al. (2011). Cerebral Palsy: clinical care and neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurology, 10, 844-852.

Anaby D, Law M, Coster W, et al. (2014). The mediating role of the environment in explaining participation of children and youth with and without disabilities across home, school, and community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 95: 908–17.

Andersen, M.M. (2016). Camp-håndbog: Praksis-teoretisk håndbog for fagpersoner - En aktivitetsintervention for målgrupper med udfordringer. Elsass Fonden

Ashton-Shaeffer C, Gibson H, Autry C. (2001). Meaning of Sport to Adults with Physical Disabilities: A Disability Sport Camp Experience. Sociology of Sport Journal. 18:95-114.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. American Psychologist. 37(2), p. 122-147

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy, the Exercise of control, W. H. Freeman and Company New York.

Barnes, M. P. (2001). An overview of the clinical management of spasticity. In Barnes M. P. & Johnson G.R. (eds.), Upper motor neuron syndrome and spasticity: Clinical management and neurophysiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1 – 11.

Borge, A. I. H. (2010). Resiliens: Risiko og sunn utvikling. (2) Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

Braun V. & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 3:77-101.

Colver A, Thyen U, Arnaud C, et al. (2012). Association between participation in life situations of children with cerebral palsy and their physical, social, and attitudinal environment: a cross-sectional multicenter European study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 93: 2154–64.

Dawson, S., Liddicoat, K. (2009). "Camp Gives Me Hope": Exploring the Therapeutic Use of Community for Adults with Cerebral Palsy. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 43(4): 9-24

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Plenum.

Devine, M.A., Piatt, J. & Dawson, S. L. (2015). The Role of a Disability-Specific Camp in Promoting Social Acceptance and Quality of Life for Youth With Hearing Impairments. Therapeutic Recreation Journal 49(4) p. 293–309

Devine, M.A. & Dawson, S. (2010). The Effect of a Residential Camp Experience on Self Esteem and Social Acceptance of Youth with Craniofacial Differences. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 44(2) p. 105–120

Garmezy, N., Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, A. (1984). The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55: 97-111.

Giorgi, A. & Giorgi, B. (2003). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. I: Camic, P., Rhodes, J. & Yardley, L. (red.) Qualitative research in psychology – Expanding perspectives in methodology and design. p. 275-297. Washington, Dc: American Psychological Association Press.

Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Om afvigerens sociale identitet. København: Gyldendal.

Goodwin D. L. & Staples K. (2005). The Meaning of Summer Camp Experiences to Youths with Disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 22(2):160-178.

Goodwin, D.L., & Lieberman, L.J. (2011). Connecting Through Summer Camp: Youth with Visual Impairments Find a Sense of Community. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28(1), 40-55.

Hidecker, M.J.C., Paneth, N., Rosenbaum, P.L., Kent, R.D., Lillie, J., Eulenberg, J.B., Chester, K., Johnson, B., Michalsen, L., Evatt, M., & Taylor, K. (2011). Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) for individuals with cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 53(8), 704-710.

ICF (The International Classification of Functioning) (2001). Disability and Health. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Jacobsen, B., Tanggaard, L. & Brinkmann, S. (2015). Fænomenologi. I. Brinkmanm, S. & Tanggaard, L. (red.) Kvalitative metoder en grundbog. 2. udgave. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Kvale, S. & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterView. Introduktion til et håndværk. 2. udgave. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Martiny, K. M. (2015). Embodying Investigations of Cerebral Palsy: a Case of Open Cognitive Science. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen.

Maxwell G, Alves I, Granlund M. (2012). Participation and environmental aspects in education and the ICF and the ICF-CY: findings from a systematic literature review. Dev Neurorehabil. 15: 63–78.

McAvoy, L., Holman, T. Goldenberg, M. & Klenosky (2006). Wilderness and Persons with Disabilities Transferring the Benefits to Everyday Life. International Journal of Wilderness. 12(2): 23-35.

Michalski, J. H., Mishna, F., Worthington, C., & Cummings, R. (2003). A multi-method impact evaluation of a therapeutic summer camp program. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 20(1), 53-76.

Miles, M.B. & Hubert A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis – An expanded sourcebook. London: Sage Publications.

Novak, I. et al. (2013). A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 55: 885–910.

Nyquist A., Jahnsen R.B., Moser T. & Ullenhag A. (2019). The coolest I know - a qualitative study exploring the participation experiences of children with disabilities in an adapted physical activities program. Disability Rehabilitation. P. 1-9.

O’Leary, V. E. (1998). Strength in the face of adversity: Individual and social thriving. Journal of Social Issues, 54, 425-446.

Palisano, R. J.; Rosenbaum, P. L.; Bartlett, D. J.; Livingston, M. H. (2008). Content validity of the expanded and revised gross motor function classification system. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 50: 744-750.

Pandyan A. D. et al. (2005). “Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement.” Disability and Rehabilitation, 27, 2-6.

Powrie, B., Kolehmainen, N., Turpin, M., Ziviani, J. & Copley, J. (2015). The meaning of leisure for children and young people with physical disabilities: a systematic evidence synthesis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 57: 993–1010

Rosenbaum, P. et al. (2007). “A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006.” Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 109(suppl 109), 8-14. Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychological. 55(1), 68-78.

Sheean, G. (2001). “Botulinum toxin treatment of spasticity: Why is it so difficult to show a functional benefit?” Current Opinion in Neurology, 14:771 – 776.

Smith, B. & Sparkes, A.C. (2006). Narrative inquiry in psychology: exploring the tensions within, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:3, 169-192.

Smith, B. & Sparkes, A. (2018). Interviews: qualitative interviewing in the sport and exercise sciences. In: B. Smith and A.C. Sparkes, eds., Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 103-123

Steinhardt, F., Ullenhag, A., Jahnsen, R., Dolva, A-S. (2019): Perceived facilitators and barriers for participation in leisure activities in children with disabilities: perspectives of children, parents and professionals, Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Stelter, R. (2012). Tredje generations coaching – en guide til narrativ-samskabende teori og praksis. Dansk Psykologisk Forlag.

Sundhedsstyrelsen (2014). National klinisk retningslinje for fysioterapi og ergoterapi til børn og unge med nedsat funktionsevne som følge af cerebral parese – 9 udvalgte indsatser.

van Manen, M. (1997). Researching lived experiences: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London, Canada: The Althouse Press.

van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of Practise. Meaning- Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. London and New York. Routledge.

Wang, H. & Yan, Q. (2018). A review of the treatment of cerebral palsy in children. TMR NonDrug Therapy. 1(4): 151-158.

Studie II

“then the other trainer said: "try if you can jump alone". And I just thought "fuuuuuck alone" (laughs). But then I tried it alone and thought “I can actually do this”. (…) I became very proud of myself because I had never believed I could do that. It wasn't because I was insecure about it, it was just… Wow.”

Moved by Movement A phenomenological study of how young people and adults with cerebral palsy experience participating in the challenging adapted physical activities at a sports camp

Mie Maar Andersen¹ ², Helle Winther³

1 Elsass Foundation, Charlottenlund, Denmark 2 Department of Neuroscience, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 3 Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Keywords

Adapted physical activity Camp Holistic

Disability Rehabilitation

Corresponding author:

Mie Maar Andersen Elsass Fonden Holmegårdsvej 28 DK - 2920 Charlottenlund Mail: mma@elsassfonden.dk Phone: (+45) 30489048

Moved by Movement A phenomenological study of how young people and adults with cerebral palsy experience participating in the challenging adapted physical activities at a sports camp.

Abstract

Using physical activity in rehabilitation programs for people with cerebral palsy has a long and strong tradition. In this tradition physical activity primarily has been considerate as a method for treatment purposes mainly to improve and restore lost function. As a contribution to this important field of practice and research, this paper investigates how a phenomenological approach can be used to elucidate how people with cerebral palsy experience being a part of the multiple adapted physical activities at a four-day sports camp. In doing so, we examine the ways in which adapted physical activities can be used to enhance the psychosocial development potential of people living with cerebral palsy. Two rounds of semi-structured interviews with 16 participants at four camps were carried out. The first round aimed at getting a sense of the participants’ daily lives, and the second at getting a sense of their experiences at camp. The participants experienced the camp and adapted physical activities as different and challenging compared to their daily lives and traditional rehabilitation measures. Participating in the activities gave them new and enhanced perspectives on themselves, their disability and abilities. This study shows that a more holistic, diverse and challenging approach to adapted physical activity could be included in rehabilitation interventions for people living with cerebral palsy.

Keywords: Adapted Physical Activity; Camp; Holistic; Disability; Rehabilitation

1. Introduction

Using physical activities in rehabilitation programs for people with cerebral palsy (CP) has a long and strong tradition. In this tradition, physical activity has primarily been considered as a treatment method that aims to improve and restore lost function (Normann et al., 2004; Kissow, 2006). Alternatives to this traditional approach have emerged over the last fifty years that embrace more holistic movement rehabilitation interventions for people with disabilities. Especially the use of Adapted Physical Activity (APA) (Sherrill, 2004) has become an important component in holistic rehabilitation of people with disabilities (Standal & Kissow, 2007). Additionally, the use of Outdoor Experiential Therapy (OET) (Ewert et al., 2001) has expanded. It can be said that OET

is a discipline within APA, but in this paper, we choose to divide the two concepts as they come from different traditions. This paper is motivated by a wish to argue for a more holistic orientation toward using APA and OET in rehabilitation programs for people with CP. Despite the increased use of holistic approaches and the promising research findings related to them, the arguments for why movement and physical activity are beneficial, and the recommendations on how they should be practiced in relation to people with CP are still mainly dominated by arguments related to the biological physical body (Verschuren et al. 2008; 2016; Novak et al., 2013; Wang & Yan, 2018). These arguments and recommendations draw on research that demonstrates the benefits of physical activity for people with CP, including studies that show how physical activity for people with CP can reduce the impact of fetal or infant brain damage on the person living with CP (Damiano, 2006; Lorentzen & Nielsen, 2012). Furthermore, physical activity can help improve motor control and local bodily functions (Nupo, 2011; Kitago & Krakauer, 2013; Nielsen et al., 2015), reduce the risk of developing lifestyle diseases (Nsenga et al., 2013; Unnithan et al. 2007; Verschuren etal, 2007; Slaman et al., 2014) and improve cognitive development (Kramer & Erickson, 2007; Hilman et al., 2014). As can be seen in the above development potentials, the use of physical activity is a rehabilitation strategy that can be beneficial in various ways. However, practice and rehabilitation recommendations also need to pay attention to the value of more holistic development potentials that take account of psychosocial factors in the lives of people living with CP. This holistic perspective is relevant, as people with CP per definition will carry a stigma (Goffman, 2009), which most likely will have a devaluating psychosocial influence. Research studies have demonstrated that people living with CP often have a sense of not trusting their own body, feel different and unaccepted, and find it difficult to be in uncontrolled and challenging situations (Sandström, 2007; Horsman et al., 2010; Brunton & Bartlett, 2013; McLaughlin & ColemanFountain, 2014; Martiny, 2015). Furthermore, people living with CP often find it difficult to form important relationships with peers and to participate in social situations (Shikako-Thomas et al. 2008; Bottcher, 2010; Michelsen et al., 2006), and have clear challenges related to coping with school, work and cohabitation (Michelsen et al., 2014; 2017).

This paper therefore aims to contribute to the psychosocial arguments for and recommendations on how movement can be beneficial in a rehabilitation process for people with CP. This is done by using a phenomenologically inspired approach to elucidate how young people and adults with CP experience being a part of the adapted physical activities at a four-day sports camp, and we discuss how the activities can be understood as valuable in a rehabilitation process. The sports

camp was designed to stimulate resilience processes (Luthar, 2003; Rutter, 2008; Ungar & Liebenberg, 2013). More specifically, the sports camp aimed to enhance the participants’ motivation for sports and movement, their social relationships, self-perception and perceived future possibilities (Andersen, 2016). This was done by using a combined APA and Outdoor Experiential Therapy (OET) approach to the movement activities in an overall resilience-based framework. This approach will be expanded on in the methods section, while we in the following elaborate on APA, OET and relevant findings made in these fields.

Adapted Physical Activity (APA) and Outdoor Experiential Therapy (OET)

The term APA is used in different areas, including the professions of education, disability sport, recreation and rehabilitation (Sherrill & DePauw, 1997). When using APA in this paper, we refer to a movement approach used in relation to recreational and rehabilitative programs. In this context, all movement activities can be included in APA. What is important is that the activity and context around the activity must be adapted to the participants’ needs and not the other way around (Sherrill, 2004). The term OET can be interpreted as a discipline within APA. However, OET is highlighted independently in this article as this concept plays a central role in the intervention sports camp that this study is based on. In this context, OET is used as an umbrella term that encompasses the different, but related, modalities of wilderness therapy and adventure therapy (Ewert, McCormick & Voight, 2001). These approaches are characterized by a structured movement program that utilizes an outdoor setting and direct experience (ibid.). In a rehabilitation setting, both the APA and OET approaches acknowledge the physical health and physical well-being benefits of movement programs, while also emphasizing movement as a psychological, pedagogical or socio-cultural therapeutic method. According to APA, this holistic use of movement can empower and help to stimulate self-actualization (Sherrill, 2004), and in an OET perspective, movement can enhance an individual's physical, social and psychological wellbeing (Ewert et al., 1999). In a rehabilitative setting for people with CP, the APA approach, has especially been used with water activities (Sutthibuta, 2014) and horse riding (Rosenbaum, 2009). However, there are no clear and reliable conclusions about effectiveness and clinical applications (Sutthibuta, 2014; Rosenbaum, 2009). This does not mean that APA disciplines are not valuable. On the contrary, a review focusing on the meaning of APA leisure activities for children and young people with disabilities found that these activities stimulated valuable elements such as feelings of fun, freedom, fulfillment of potential and social connectedness (Powrie et al., 2015). Additionally,

studies find that participating in both spontaneous and more structured forms of leisure activities and therapeutic programs focusing on leisure improve the quality of life of children with

disabilities (Shikako-Thomas et al., 2012; Dahan-Oliel et al., 2011). Finally, Kissow & Singhammer (2012) found a significant correlation between people with disabilities who participated in sports or movement activities and employment, educational status, volunteerism, leisure time schooling and membership in a disability organization.

In rehabilitative settings for people with CP and other disabilities, camp programs that integrate multiple movement disciplines have also used an APA approach, an OET approach, or a combination of these approaches (Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Michalski et al., 2003; Devine and Dawson, 2010; Devine et al., 2015; McAvoy et al., 2006; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Goodwin et al., 2011; Nyquist et al., 2019; Røe et al., 2018; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017). All these studies highlight the significant contribution of a social community with equals to rehabilitative outcomes. Nevertheless, in relation to the present study, we are more interested in the findings associated with movement activities. In this regard, many associated themes related to movement activities are highlighted in the aforementioned studies.

Firstly, the activities lead to many new skills, learning situations and an opportunity to discover new activities available to them (Nyquist et al., 2019; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009, Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; McAvoy et al., 2006; Goodwin et al., 2011; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017). Furthermore, the accomplishments in the activities

stimulated increased self-confidence and an opportunity to create new identity alternatives (ibid.). Another common finding in the studies is that many participants associated the activities with great enjoyment and fun. (Nyquist et al., 2019; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009; Ashton-Shaeffer et al., 2001; Goodwin et al., 2011). Finally, some studies highlight how the accomplishments in the activities encouraged greater independence (Dawson & Liddicoat, 2009; Goodwin & Samples, 2005), and additionally, inspired some of the participants to make changes in their everyday life, as the experiences provided an opportunity to realize their potential (Nyquist et al., 2019; Goodwin & Samples, 2005; Aggerholm & Moltke Martiny, 2017; McAvoy et al., 2006) These findings appear important in relation to accommodating some of the psychosocial challenges many people with CP experience. Furthermore, these five components can be understood as important mediators that also promote physical benefits. This corresponds with studies that show how personal factors, such as intrinsic motivation and having an identity as a

physically active person, are a greater indicator of physical activity participation for people with disabilities, than environmental factors or factors related to functioning (Saebu & Sørensen, 2011; Martin, 2006; Sørensen, 2006). In a similar fashion, Steinhardt and colleagues (2019) found that children with disabilities primarily identify their own preferences, enjoyment and friendship as the factors that motivate them to participate in leisure activities.

Despite the research findings described above, holistic movement approaches still do not have a strong voice in rehabilitation practice and recommendations for people with CP in most countries (Verschuren et al. 2008; 2016; Novak et al., 2013; Wang & Yan, 2018). This study aims to provide new perspectives and insights that can further substantiate a holistic movement approach in rehabilitation programs for people with CP. This is done by giving a voice to young people and adults involved in a sports camp, and hereby elucidating in a first-person perspective how they experience being a part of the challenging adapted physical activities.

2. Method

2.1 Phenomenological approach and method

The present study uses a phenomenological inspired approach to elucidate the meaning of participating in the adapted physical activities at the sports camp. Through this phenomenological approach, we are interested in looking at how people create meaning from their experiences in their lifeworlds (van Manen, 1997;2016; Jacobsen et al., 2015; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). The lifeworld in this context will be the world the participants experience in a first-person perspective when participating in the adapted physical activities at camp. This approach is chosen for mainly two reasons. First, there is a need for phenomenological insights on the effects of adapted physical activities in interventions for people with CP, as little research has been carried out on this aspect of interventions. Second, a qualitative descriptive approach can uncover aspects of the activities that have not been elucidated before. These insights can thus create various understandings of how adapted physical activities can create meaning and stimulate development. Such insights could lead to new strategies and recommendations in rehabilitation for people with CP.

2.2 Context - sports camp

This study investigated four 4-day residential sports camps run in Denmark, each of which comprised two-three daily activities, two daily group talks, and three meals. The sports camps were developed and arranged by the Elsass Foundation of Denmark (Andersen, 2016) and was

designed to stimulate resilience processes. The conceptual framework of the camp is inspired by three models of psychological resilience (the protective, compensatory and challenge models) (Garmezy et al., 1984; O’Leary, 1998; Borger, 2010).

1. The protective model of resilience, posits that an environment that is

perceived as protective, safe and secure can enhance competence development and selfesteem. Establishing such an environment formed the foundation of the camp and is therefore in focus from the first day. The participants must experience being part of an inclusive and tolerant environment that is characterized by collaboration, unity, optimism and support. This foundation must be established so that the participants can dare to risk themselves when their competences, safety limits and boundaries are challenged towards the end of the camp. The activities in the first part of the camp will therefore always be inclusive games, exercises and activities with a focus on trust, fun and teambuilding.

2. The compensatory model of resilience, implies actions that can

support and accommodate elements that are missing in a person’s life. In relation to the camp activities, there is a great focus on a flexible and optimistic mindset where collaborative and creative solutions are in focus when activities and surroundings are adapted to fit the participants. To accomplish this in practice, many of the chosen activities are formed as communities of individual action. The individual focus means that a participant’s chance of success is not dependent on the other participants as it would be in team sports. At the same time, they participate side by side, and therefore still get an experience of shared participation. Examples of such activities are trampolining, martial arts or stand-up paddle board.

3. The challenge model of resilience,

argues that people will be stronger and more able to cope with new challenges, if they are adequately challenged and experience to manage this kind of situation. At the camp, it is vital that the professional team dare to invite the participants into scenarios which cross the boundary of their perceived possibilities and abilities. This is a crucial point, as participants’ level of experienced success and belief in their own abilities will often grow in line with the level of perceived challenge, if the challenge is satisfactorily managed (Ewert, 1999; Herbert, 1996; Henriksen et al., 2008). Depending on the weather the activities chosen often will be in –or outdoor adventure activities such as climbing, jumping from a diving board in the swimming pool, mountain biking, going through a military obstacle course or kayaking.

The four sports camps involved in this study can be seen in the table below:

Participants Location

Camp 1 20 Elsass Foundation Camp 2 16 Elsass Foundation Camp 3 11 Egmont Folk Highschool Camp 4 10 Club La Santa Table 1. The four Elsass Foundation camps included in this study

Age

10 - 13 14 - 18 10 - 17 30 - 60

Condition

Able to walk Able to walk Using wheelchair Able to walk

Despite diversity in age, camp location and level of disability, the activity program was similar at

every camp. At all camps, a team of professionals from the Elsass Foundation from the fields of sports psychology and pedagogy, physiotherapy and occupational therapy were involved. The role of the professionals was to create a safe and trusting environment, by engaging in a personal, equal and collaborative relationship with the participants. In addition, the role of the professionals was to seek solutions, show belief in the participants, push and support them in challenging situations, and have reflective conversations continuously during the activities in relation to the subsequent narrative interpretation.

2.3 Participants

The professional team in charge of the camps reviewed data on the registered participants to select four participants at each camp (16 in total) who were then asked if they could agree to participate in the study. Participants were chosen in a manner that achieved the greatest possible diversity in gender, age, camp experience and degree of disability. All participants asked to participate chose to accept the invitation and parents and participants more than 18 years old signed a form of

consent.

All 16 participants had CP, and 12 of them (camp 1, 2 and 4) were classified as level I and II on the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) (Palisano et al, 2008). This ensured that they could perform gross motor skills such as walking, running and jumping. The last four participants (camp 3) were classified as level III and IV. While two of them could walk with assistance, all used a wheelchair most of the time, and needed support in many activities. The participants represented a diversity of circumstances in their daily lives. While some

participants attended normal schools without extra support or were employed under normal conditions, many participants had special arrangements at school or work. Several participants participated in spare time activities such as sport, while some did not. Some had many friends with or without CP, while some felt very lonely. Some had strong cognitive abilities, while some struggled to find a sense of coherence.

In the article every participant is anonymized. The names used in the paper are created by the authors.

2.4 Data creation