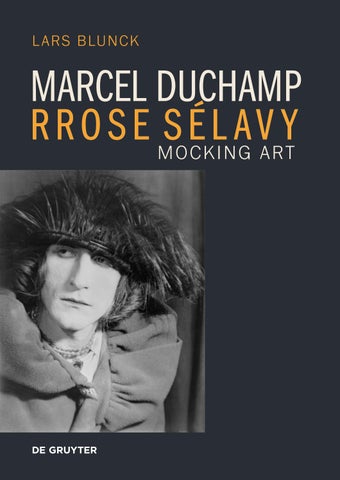

MARCEL DUCHAMP RROSE SÉLAVY

MOCKING ART

LARS BLUNCK

MARCEL DUCHAMP RROSE SÉLAVY

MOCKING ART

ISBN 978‑3‑68924‑248‑0

e ISBN (PDF) 978‑3‑68924‑042‑4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025944223

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin / Boston, Genthiner Straße 13, 10785 Berlin

Copyediting: Ian Copestake

Cover illustration: Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, 1921, modern print from glass plate negative, 12.0 × 9.0 cm, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, courtesy Man Ray Trust, Pierre Yves Butzbach © Man Ray 2015 Trust / VG Bild Kunst, Bonn 2025

Cover design: Rüdiger Kern, Berlin

Typesetting: Savage Types Media GbR, Berlin Printing and binding: Beltz Grafische Betriebe GmbH, Bad Langensalza

www.degruyter.com

Questions about General Product Safety Regulation: productsafety@degruyterbrill.com

10 AU‑CUL‑ISM

12 A Hot Ass

15 Rrose’s Birth

18 Chaste Passion and Ennui

30 ARROSER R(R)OSE

33 An‑artist vs. Au‑culist

39 Detached and Solitary

44 Duchamp = Marcel + Rrose

62 Jeux de mots

65 An Étiquette for Ettie

67 Lucubrations 74 MAKING WINDOWS

75 A Mocking Memorial

83 A French Window

176 UNDER THE NAME RROSE SÉLAVY

177 Drawing on Chance

182 Wanted: Rrose Sélavy

185 The Authentic Work of Rrose Sélavy

190 RROSE HERSELF

195 The Sky of Flying Foxes

200 Appearance: Rrose Sélavy

210 Bibliography

238 Photography Credits and Copyrights

“Sélavy et Rrose qui appellent un examen spécial.”1 (Sélavy and Rrose who require special examination.)

André Breton, “Marcel Duchamp,” Littérature 5 (October 1922), pp. 7–10, here p. 10.

AU‑CUL‑ISM

On the morning of November 10, 1961, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) had an appointment at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. 1 It was the beginning of the very decade in which Duchamp would rise to become one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century at the age of retirement, nearly half a century after at times of the avant‑gardes his most significant works had been created in private. At MoMA, Duchamp now encountered the photographer Marvin Lazarus (1918–1982), a full‑time lawyer and passionate portrait pho‑ tographer. Lazarus had been engaged in a photographic project for more than three years. Adopting a chronicling approach, he portrayed US‑American art‑ ists. In December 1959, he had already photographed Duchamp in his New York studio apartment.2 Now, on one of the final days of the exhibition The Art of Assemblage, 3 Lazarus seized the opportunity to photograph the elderly artist surrounded by some of his works in the Museum of Modern Art.

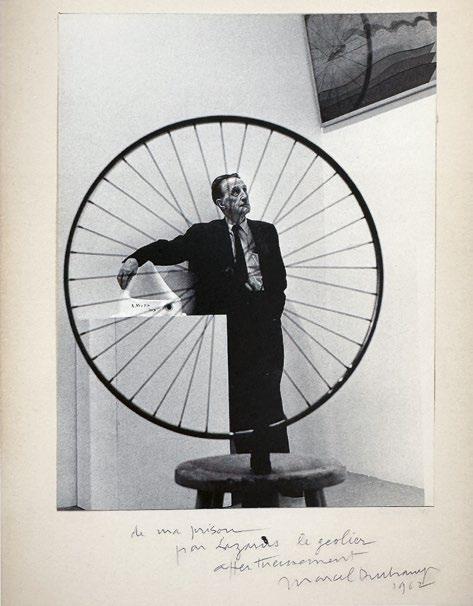

Among the photographs taken that Friday morning, one particular portrait stands out (fig. 1). The photograph depicts Duchamp, seen through the rim of his Bicycle Wheel (1913/1951).4 He has positioned himself adjacent to a museum pedestal, resting his arm in an almost chummy manner on a replica of his uri nal Fountain (1917/1950)5 and looks up at his last painting Tu’m (1918).6 In the following months, Duchamp would dedicate a print of this photograph to his portrait photographer, with the inscription: “de ma prison [/] par Lazarus le geôlier [/] affectueusement [/] Marcel Duchamp [/] 1962.” As indicated by the humorous phrase “from my prison by Lazarus the jailer,” Duchamp is literally trapped ‘behind bars’ (allusively visualized by the spokes of the wheel). Jokingly, Duchamp identifies himself as a prisoner in the museum. Almost trapped with those works that were initially, in the 1910s, not supposed to be “‘art’”7 at all: not, as he would com‑ ment in 1962, “art with a capital ‘A.’”8 But, as we know, things turned out differently: With a delay of almost half a century, Duchamp’s works of the 1910s, origi‑ nally located in his private sphere, had been conse‑ crated in ‘art.’ From then on, their replicas were sol‑ emnly exhibited in museums. The self‑proclaimed “an‑artist”9 had become arguably the most influential artist of the twentieth century.10 C’est la vie!

1. Marvin Lazarus, Marcel Duchamp, 1961, gelatin silver print on paper, 25.4 × 20.3 cm (10 × 8 in.), Roberta Fast Lazarus

Marcel Duchamp’s dedication of this particular photographic print to Marvin Lazarus was presum‑ ably a response to an earlier inscription that Lazarus’ wife Roberta had placed under another photograph (fig. 2).11 It depicts Duchamp in half profile behind a display case containing the famous reproduction of the Mona Lisa, 12 to which Duchamp had added a moustache and a goatee in 1919 and which he had

2. Marvin Lazarus, Marcel Duchamp at Museum of Modern Art with moustache and goatee, 1962, gelatin silver print on paper, 23.8 × 15.1 (9⅜ × 55⁄6 in.), Philadelphia Museum of Art

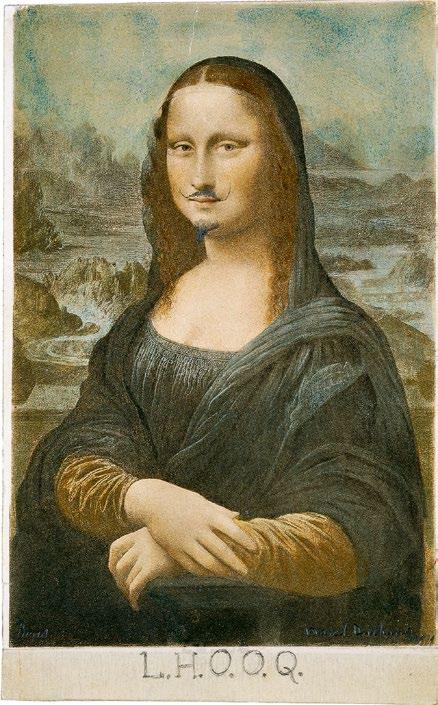

3. Marcel Duchamp, L. H. O. O. Q., 1919, pencil on chromolithography, 19.7 × 12.4 cm (7¾ × 4⅞ in.), private collection, Geneva

subtitled “L. H. O. O. Q.” (fig. 3).13 According to Duchamp, the “meaning” of the French letters was “to read them phonetically,”14 because “reading the letters is very amusing. … By reading the letters … some astonishing things happen.”15 In doing so, the letters “L. H. O. O. Q.” become the phonetic sequence él ache o o qu, which semantically become: Elle a chaud au cul16 (She has a hot ass).17

A Hot Ass

One can imagine Marcel Duchamp explaining to his portrait photographer at the Museum of Modern Art in the fall of 1961 why the Mona Lisa had “a hot ass” in 1919. This chromolithographic reproduction, to which he had merely added a moustache and goatee as well as the short letter code, may have been intended in that year to serve a memorial function. It may have been created as an ironic epitaph for the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who had died the previous year at an early age:18 “[A] pun on Apollinaire,”19 as Duchamp put it in another context.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) was a close companion and, to some extent, a friend of Duchamp’s in the 1910s. However, they had parted ways

when Duchamp had moved to New York in the summer of 1915, after the start of the First World War. Duchamp had resided in New York since then, but departed for Buenos Aires in August 1918, leaving works in New York behind such as his major work, the so‑called Large Glass (1915–1923),20 which then was still in progress; he subsequently returned from Argentina home to Paris in the summer of 1919, though not for an extended period. By the time he returned in Paris, Apollinaire had already passed away from the Spanish flu the previous fall.

In 1919, Duchamp purchased an art print of the Mona Lisa on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris, not far away from the Louvre. Likely in commemoration of Apollinaire. In fine strokes he applied a moustache and goatee to the Gioconda, signing the work with his name and adding the phrase “L. H. O. O. Q.” at the bottom of the card. It was not done for exhibition purposes, rather it was a personal, private matter. “I haven’t shown it anywhere,”21 Duchamp would later explain. Consequently, L. H. O. O. Q. has not be exhibited until a decade later, in Paris in 1930.22 We must bear this in mind: Duchamp’s works of the 1910s were generally not conceived as “exhibition art”.23 They were meant to remain private.

The onomatopoetic inscription, implying that the Mona Lisa has a “hot ass,” may be interpreted as a reference to Apollinaire’s criticism of the Louvre’s negligent fire prevention measures. In the days after the infamous theft of the painting on August 21, 1911, Apollinaire publicly denounced the Louvre’s “laisser‑aller” in the daily newspaper L’Intransigeant. In particular, he criticized the museum’s “indifference” and “carelessness,” and complained that “the guards” have “never had any fire drills.”24 A somewhat far‑fetched, if not petty accusation, given the pressing problems that the museum’s management was facing at the time because of the theft. From Apollinaire’s perspective, however, the Mona Lisa was at risk of literally getting a “hot ass” in the event of a fire (at the latest after her expected future return). Indeed, it was Apollinaire himself who became unexpectedly hot, both literally and figuratively speaking, in the aftermath of the crime.

It is possible that in 1919, when Duchamp purchased and altered the print, he recalled that in the late summer of 1911 in the tumultuous weeks following the theft Paris was suffering from an enormous heat wave.25 It seems more probable, however, that he recalled Apollinaire getting into trouble; getting hot, so to speak. In early September 1911, Apollinaire abruptly found himself in the crosshairs of the investigation. On the evening of September 7, he was arrested and incarcerated for five days in the legendary La Santé prison.26 His acquain‑ tance with a Belgian scoundrel named Honoré Joseph Géry Piéret put him in this situation. The latter had worked as a secretary for Apollinaire and earlier had occasionally stolen statuettes from the Louvre.27 Consequently, in connection with the theft of the Mona Lisa, it seemed conceivable that the investigating au‑

thorities would suspect Apollinaire of the theft. This suspicion, however, would not be corroborated.28

Immediately following his release the investi gation against Apollinaire was not officially con‑ cluded until early 1912 the evening newspaper Paris Journal published an article entitled Mes Prisons, in which Apollinaire reported on “sadness,” “loneli‑ ness,” and “a sensation of death”29 during his period of imprisonment (and we recall Duchamp’s dedica‑ tory inscription on his photographic portrait half a century later: “de ma prison”). Additionally, in September 1911, Apollinaire’s poem A la Santé pre‑ sents a further parallel to the 1961 photo shoot, as he likens himself to the biblical Lazarus: “Lazarus de‑ scends into the tomb [/] Instead of leaving it.” And in another verse it says: “Before entering my prison cell [/] I had to undress [/] What sinister voice howled [/] Guillaume you have fallen.”30

There is no better way to put it: in the fall of 1911 Guillaume Apollinaire was in serious trouble. In those truly remarkable days, the press was relentless in its pursuit of him. Apollinaire was fearful of being threatened with deportation, and he had great difficulty clearing himself of the allegations.31 During a police interrogation, Pablo Picasso, who had previously been deeply implicated in the theft of statu‑ ettes by Piéret, is said to have denied even knowing Apollinaire. The friendship deteriorated. Even Apollinaire’s lover, Marie Laurencin, turned her back on him while he was still in prison.32 In the fall of 1911, in connection with the theft of the Mona Lisa, Guillaume Apollinaire had reached a low point in his life.

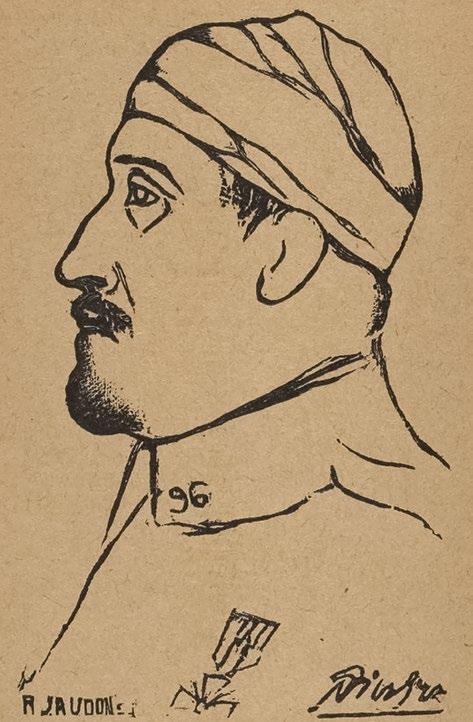

4. Frontispiece (detail) of Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligrammes, Poèmes de la paix et de la guerre (1913–1916) (Mercure de France, 1918), n.p (p. 8)

Upon returning to Paris in the summer of 1919 after an extended absence, Duchamp could have reflected on all these events. With the distance of time, mild irony and certainly not without sympathy for the recently deceased Apollinaire, he could have distilled his memories into a concise, onomatopo‑ etic formula: “L. H. O. O. Q.” At the very least, it makes sense to relate this caption not only to the Gioconda, but also, implicitly, to Apollinaire,33 espe‑ cially, since the Gioconda’s exaggerated, literally sharpened moustache and chin beard can be associated with a portrait of the flamboyant poet by Pablo Picasso (fig. 4),34 although (or even because) Apollinaire looks a little scruffy.

Duchamp may have discovered this image in the summer of 1919 in the book of poems Calligrammes, which Apollinaire had published the previous year, shortly before his demise. The portrait depicts the war‑wounded Apollinaire in profile, in uniform with a medal of merit on his lapel and a bandaged head, but above all with an unkempt beard. More than four years earlier Duchamp had

last met Apollinaire in person, but now, in 1919, on the frontispiece of this book, the deceased friend could have encountered him ‘in effigy.’ Contrary to expectations, with a moustache and chin beard. At the same time, the Mona Lisa’s facial hair might also allude to Apollinaire’s influential play Les Mamelles de Tirésias, which premiered in 1917. In the play, the character of Thérèse aspires to transcend her role as a woman and become a man. She allows her breasts to float away like balloons and grows a beard, which is not only a “chin beard,” as Apollinaire writes, but also a “moustache.”35 It appears that Duchamp by inter‑ vening in Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa visually realized Apollinaire’s literary fiction, as the Gioconda is depicted wearing a “moustache and a beard.”36

Such references to L. H. O. O. Q. can only be assumed, not proven, since Duchamp himself did not make any specific statements regarding his inten‑ tions. Many possibilities, but hardly any certainties. This constitutes a herme‑ neutic problem. Conversely, it presents a delightful interpretive challenge. Duchamp’s works frequently rely on a complex network of references that are often difficult to identify with certainty from a historical distance. Even for uninitiated contemporaries of Duchamp and hardly anyone was initiated in the 1910s they were difficult to decipher. In particular, the ‘Duchamp method,’ as we shall see, involved evoking a multitude of associations: “All associations are permitted,” Duchamp would later explain, “the more the better.”37 We shall return to this intended multiplicity of associations several times in this book. It is a kind of leitmotif, with which “Rrose Sélavy” is also closely connected. However, there is another hint. Duchamp is said to have informed his pho‑ tographer during the shoot at the Museum of Modern Art in November 1961 that the deeper meaning of the caption “L. H. O. O. Q.” had to do with mockery: “Don’t let anybody fool you,”38 Duchamp revealed to Lazarus. It is possible that this explanation prompted Lazarus to seize the opportunity a year later, in 1962, to “make a fool” of Duchamp for the sake of amusement. Lazarus’ wife Roberta, also an artist, added a moustache and goatee to the Duchamp portrait photo (fig. 2) very similar to Duchamp’s L. H. O. O. Q., and on March 12, 1962, inscribed a mocking caption: “Dear Rrose, [/] Here’s one on you, oui? Regards, [/] Juan Ennui.” The fact that here, in 1962, Marcel Duchamp was explicitly addressed as “Rrose” and thus as his enigmatic, if somewhat at the time already mature ‘alter ego’ (Rrose Sélavy), indicates a close familiarity with the artist, but above all with his ironic and fundamentally mocking attitude.

Rrose’s Birth

“Rrose Sélavy née en 1920 in N. Y.,”39 Marcel Duchamp noted in a handwritten, undated memorandum. As his metaphor of a ‘birth’ suggests, Duchamp may have been intellectually ‘pregnant’ with Rrose as early as 1919 in Paris,40 exactly at the point in time when L. H. O. O. Q. was created. However, Rrose was not

actually ‘born’ until 1920 in New York. This “birth” to stay with Duchamp’s metaphor coincided with the artist’s anew residence in New York. It also marked a recurrent turning away from the European, the French, and especially the Parisian art scene.

Duchamp departed Paris at the beginning of 1920 and returned to New York. Perhaps with new plans, but certainly with a radicalized attitude. As far as the Birth of Rrose is concerned, he aspired to cultivate “just two identities” as an ‘artist,’ “that’s all.”41 For his second “identity,” his first impulse was “to get a Jewish name, but I didn’t find one.”42 In retrospect, Duchamp would make repeated reference to this “Jewish name.” 43 Furthermore, he frequently re counted the ironic conversion from his ‘religion’ to another (which can be understood as a shift from an an-artist to what I will refer to as an au-culist). In 1920, his duplication of identities was intended to extend his artistic attitude, analogous to a transition between related but not identical professions of faith. “Then the idea jumped at me,” he would later recall, “why not a female name? Marvelous! Much better than to change religion would be to change sex.”44 In 1920, Duchamp’s initial concept of employing the metaphor of changing reli gion to achieve a broadening of artistic attitudes gave way to the idea of intro‑ ducing a complementary “female name.” Thus, as it were, of “changing sex,”45 or rather establishing coexisting genders. “So the name Rrose Sélavy came from that.”46 And that name, of course, was an “effortless pun,”47 “a phonetic game,”48 a game with the homophony of different words: “Sélavy, of course, was C’est la vie.”49 As we will see, Rrose stemmed from life.

In the 1920s, Duchamp, operating under the name Rrose Sélavy, engaged in a highly enigmatic and ironic mockery that was already evident in the 1910s in works such as L. H. O. O. Q.50 The name was first spelled with one ‘R’ (Rose) and then, from the summer of 1921 onward, with two (Rrose). In the name of R(r)ose, a range of individuals and groups, including friends and acquain ‑ tances, art patrons, and entire artistic movements were subjected to ironic mockery. This included, for example: in 1920 and 1921, Guillaume Apollinaire as well as the painter Robert Delaunay and the so‑called peinture pure with Fresh Widow and La Bagarre d’Austerlitz (see the chapter “Making Windows”); the insistent claim to an ‘art of touch’ by some modern artists such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti with Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? in 1921 (see the chapter “An Ominous Sugar Cage”); also in 1921, the Parisian art critic Maurice Raynal and, once again, pure painting with Belle Haleine, and in the same year Tristan Tzara and Dadaism with New York Dada (see the chapter “Beautiful Breath”); in 1924, the wealthy collector Jacques Doucet with the Rotative dèmi-sphere; 51 and finally, André Breton and Surrealism with Rrose’s contribution to the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in 1938 (see the chapter “Rrose Herself”).

In essence, Rrose Sélavy ironically mocked fellow artists, and art movements since 1920. Though, mostly in Duchamp’s private sphere, and rarely in the

context of exhibitions. Once again, in the 1910s and 20s, neither was Marcel Duchamp an exhibition artist nor was R(r)ose Sélavy exhibiting at all.

Except for Francis Picabia’s L’ŒIL CACODYLATE of 1921, works associ ated with the name R(r)rose Sélavy were not exhibited publicly until the 1930s. These include the label of the perfume bottle Belle Haleine (1921) and one of the Obligations de Monte Carlo (1924), first exhibited as late as Spring 1930;52 half a decade later Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921) in 1935;53 the following year, 1936, La Bagarre d’Austerlitz (1921);54 then, in 1938, the Rotative demi-sphère (1924);55 and only much later, in 1945, Fresh Widow (1920), as well as a replica of the WANTED poster (1923) in 1963, and the Belle Haleine bottle itself (1921) in 1964 (we will return to all these works in detail). 56 In conclusion: R(r)ose Sélavy’s ‘works’ were not exhibited in the 1920s. Even though Duchamp’s short film Anémic Cinéma from 1926 (“COPYRIGHTED [/] BY [//] Rrose Sélavy” in the last frame) premiered on August 30, 1926, in a screening room at 63 Avenue des Champs‑Elysées, and was shown for the first time in the US a few months later, on December 22, 1926, at New York’s Fifth Avenue Theatre,57 these are the only public screenings we know of until the mid 1930s. And publications directly related to Rrose Sélavy, such as the magazine New York Dada from 1921 or the anthology SOMEFRENCHMODERNSSAYSMCBRIDE published the following year, were too limited in circulation and too minimal in distribu‑ tion to stimulate a further public reception of the concept of Rrose Sélavy (which, as we will discuss, means to act as an au-culist).

In this regard, even attentive contemporaries from the art milieu of the 1920s would not have known the name R(r)ose Sélavy in connection with the works mentioned above. Rather, they would have associated it primarily with onomatopoetic aphorisms, sharp‑tongued rhymes, and sardonic bêtises pub‑ lished in avant‑garde magazines such as Francis Picabia’s 391 or André Breton’s Littérature, both with a comparatively limited circulation. Subsequently, in July 1924, the cover of Picabia’s 391, for example, featured a crude pun dating back to Duchamp’s time in New York in 1920 or ’21, or perhaps from his first weeks in Paris in the summer of 1921: “Du dos de la cuillère au cul de la douair‑ ière [//] ROSE [sic] SÉLAVY” (From the back of the spoon to the dowager’s ass).58 The phrase itself seems to indicate a kind of development in its combination of elevated expression and vulgarity: “Du dos” (From the back or from the ‘rear’) “de la cuillère” (of the spoon) or, sounding similar, “de la cul‑ier” (of the assist) “au cul” (to the ass) “de la douairière” (of the dowager’s arse or of the wealthy widow). Of course, it is questionable what exactly this was supposed to mean. And just that the specific meaning of puns and wordplays often remains Duchamp’s secret (if a specific meaning was intended at all)!

But this much can be stated with some certainty: Rrose Sélavy deliberately and with great pleasure engaged in disruptive actions. Actions that may be described as “coups de pieds en tous genres” (kicks of all kinds). At least, this is

how Rrose’s profession was recorded in one of Duchamp’s undated notes and later in one of his publications: as “Oculisme de précision” (fig. 5).59 This phrase can be understood phonetically as “au‑cul‑isme de precision” (which is essentially un‑ translatable but roughly means “precision ass‑ism”). From the early 1920s, Marcel Duchamp, who was well known for rejecting all isms,60 permitted himself his own ironic and mocking ism: an “au‑cul‑ism,” performed under the name Rrose Sélavy. We must realize that the phrase “Rrose Sélavy” represents both a name and a mode of action through which Duchamp permitted himself to transgress boun‑ daries and engage in clandestine mockery.

In 1962, Roberta and Marvin Lazarus appear to have referred to this matter. Their own inscription clearly states what the retouching of the photograph Duchamp himself with moustache and goatee (fig. 2) really was: a joke at Duchamp’s ‘expense’ (“one on you”). The joke was, however, ironically covered up by the Duchampian technique of onomatopoetic wordplay. The name of the fictitious signatory “Juan Ennui” and the interroga‑ tive sentence “one on you, oui?” are phonetically ‘mirrored.’ In a manner that is both sympathetic and ironic, as well as clever, Marvin and Roberta Lazarus engaged in a form of mockery very much in the style of Duchamp. At his ‘ex‑ pense.’ And this was thoroughly consistent with the spirit of Rrose Sélavy. Furthermore, the fictional author’s surname “Ennui” appears to allude to Duchamp’s non-artistic attitude, which is essential for Rrose Sélavy. Presumably, Duchamp, during the photographic sessions in the museum, had informed his portrait photographer about his unwillingness to create art, about his artistic ennui. This very ennui was the source of his motto in 1920: Éros, c’est la vie!

Chaste Passion and Ennui

5. Frontispiece of Marcel Duchamp, Rrose Sélavy (GLM, 1939), n. p.

Duchamp’s ennui was exactly the opposite of a common artistic urge to create. It was the antithesis of the classical concept of the artist driven by desire, which posits that the artist’s sexual passion is directed toward artistic creation and his libidinal desire toward his artistic work. This notion of the virile, fertile artist had emerged during the early modern period around and after 1500 with the establishment of the emphatic concept of art. It was accompanied, if not actually determined by, a metaphorical conflation of creativity and procreation, an equation of artistic potency with sexual procreative power.61 Duchamp’s motto Éros, c’est la vie was the exact counter‑concept!

According to an anecdote, Michelangelo Buonarotti is said to have de‑ scribed painting as a “jealous one” that would not allow a “rival.”62 The notion of painting as a feminine person! Michelangelo, as documented by his first biographer, Ascanio Condivi, attempted to refrain from sexual intercourse in order to dedicate his full attention on his artistic work.63 This notion of the painter’s asceticism, sexual restraint, and even abstinence in pursuit of artistic excellence has persisted throughout history, including the era of Duchamp.64 Friedrich Nietzsche writes of a physical power of procreation and of “a certain overheating of the sexual system” without which “a Raphael is unthinkable.”65 Nor a Michelangelo. Even before Michelangelo (and before Nietzsche’s Raphael), the Florentine painter Cennino Cennini in his Libro dell’arte from around 1400, advised against “frequenting too much the company of ladies,” since this makes the artist’s “hand” so unsteady “that it will tremble and flutter more than shaken leaves by the wind.”66 Cennini, Michelangelo, and Nietzsche posit that eros is to be found not in love, but in art. Through true sexual absti‑ nence.

In the nineteenth century, the figure of the celibate painter had its literary origins in the novel Manette Salomon written by the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt. In 1867, the Goncourts ascribed a celibate disposition to their protagonist Coriolis: “Celibacy, according to him, was the only state that left the artist his freedom, his strength, his mind and his conscience.”67 This artis‑ tic ideal was subsequently adopted by Émile Zola in his 1885 novel L’œuvre, in which the fictional character Claude Lantier, a painter, voluntarily chooses to remain celibate. Lantier renounces his marital obligations on the grounds that “the genius must be chaste, he must sleep only with his work.”68 Through as‑ ceticism, Lantier aspires to enable himself to create a true masterpiece of paint‑ ing. He is completely obsessed with painting, displaying a fervor that recalls the mythological figure of Pygmalion. Simultaneously, Lantier experiences despair regarding his inability to successfully achieve sublimation: “His excite ment was growing,” Zola notes, “it was his chaste passion for the flesh of woman, a mad love of nudity desired and never possessed, an impotence to satisfy himself, to create from this flesh as much as he dreamed of embracing it, with his two desperate arms. These girls he chased out of his studio, he adored in his paintings, he caressed and violated them, desperate to the point of tears that he couldn’t make them beautiful enough, alive enough.”69

In Zola’s novel the painter’s passion becomes a pathological obsession. Although a fictional character (though based on Paul Cézanne), Zola’s Lantier is not the only painter unconditionally devoted to the nude on his canvas. One might consider, for example, Master Frenhofer in Honoré de Balzac’s 1831 novel Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu. 70

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, it was none other than Vincent van Gogh who, in the summer of 1888, encouraged his friend Émile Bernard

that both of them, as painters, had to maintain “our creative juices:”71 “Painting and screwing a lot are not compatible; it weakens the brain.”72 This is written in accordance with the tenets of Nietzsche’s philosophy. Already Nietzsche had advised artists to maintain a state of “chastity,” and not to “spend” oneself physically or sensually: “It is one and the same power that one expends in the conception of art and in sexual acts [Actus]: there is only one kind of power. To succumb here, to waste oneself here,” Nietzsche asserts, “is treacherous for an artist: It reveals a lack of instinct, of will in general, it can be a sign of décadence at least it devalues his art to an incalculable degree.”73 Correspondingly, Nietzsche posits that only “chastity” is “merely the economy of an artist.”74

Accordingly, also van Gogh advocated abstinence. The art historian Matthias Krüger aptly paraphrases van Gogh’s almost monastic precept of ab‑ stinence: “The artist who still wants to ‘get one up’ in painting must stay away from women. … Van Gogh believes that such abstinence is necessary to make painting couillard (from the noun couille, testicle).”75 In the case of van Gogh and many others, male potency is channeled into virile painting, into a “peinture couillarde,” into testicular painting. This notion can be discerned in the French discourse on painting, at least until the publications of the Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard. In his writings on Cézanne, Vollard referred to “peinture ‘bien couillarde,’”76 and “peinture ‘bien couillarde’ celle qu’il rêvait de ‘réaliser.’”77 Again, Krüger comments: “In peinture couillarde the impasto becomes the artistic ejaculate, the artistic working process becomes the act of procreation.”78 We know from anecdotes that numerous painters likened their brushes (from the Latin penellus / penicillus) to the penis (derived from the Latin penis). This in‑ cluded figures such as Pierre‑Auguste Renoir. Additionally, there are accounts of painters equating the creative process of painting with sexual intercourse. One notable example is Adolphe Monticelli, who celebrated the act of applying paint as a form of ejaculation.79 Even though these are only anecdotes, neverthe‑ less, they should be taken seriously in terms of their potential to perpetuate stereotypes such as the sexist idea of the virile painter. Of course, Marcel Duchamp fundamentally rejected, ridiculed and mocked these very ideas.

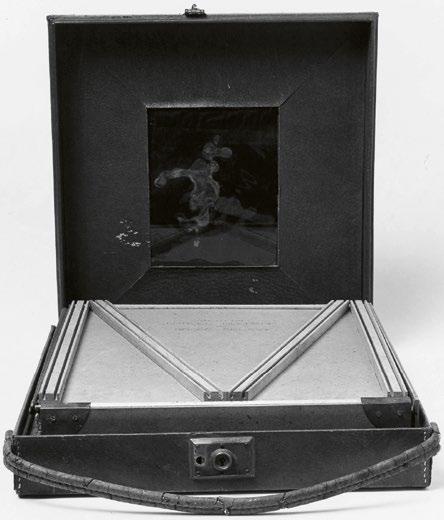

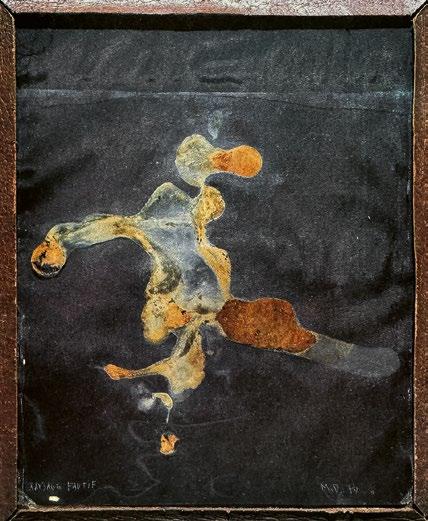

In this context, it is not mere coincidence that Duchamp, in one of his undated notes, considered the use of “the ejaculation.”80 Consequently, al‑ though as late as 1946, at the age of nearly 60, he even employed (his) ejaculate in a unique work included in one of his Boîte-en-valise (fig. 6). It is noteworthy that he gifted this copy of his Boîte to his long time lover, the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins.81 On a transparent plastic plate (of the type known as astralon, which was used at the time in printing technology, especially in cartography), the body fluid creates a surface of irregular shape and color. Comparable to a landscape map, with clearly defined contours against the background of dark satin fabric (fig. 7). This abstract “landscape” is inscribed at the bottom as “PAYSAGE FAUTIF,” that is, as a false or guilty landscape.82

6. Marcel Duchamp, De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîteenvalise), 1946, series A, no. XII/XX, valise: 41.0 × 38.0 × 10.2 cm (16⅛ × 15 × 4 in.), The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama

7. Marcel Duchamp, Paysage fautif, 1946, seminal fluid on astralon with black satin, 21.0 × 16.5 cm (8¼ × 6½ in.), The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama

In turn, this landscape painting and its title may allude to Paul Cézanne’s distinctive ‘passage’ painting technique. The Post‑Impressionist painter and after him especially the Cubists organized the transitions between traditionally linearly contoured areas of color with parallel brush strokes, the so‑called ‘pas ‑ sage’ (phonetically similar to “paysage”). But more than that, of course, Duchamp’s ejaculation painting mocked the constant “masturbation”83 of paint‑ ers. Duchamp appropriated the creative metaphor of the virile painter and transformed it into a literally handmade production of his Paysage fautif. He literally spent out himself sexually: as ‘art’! And as a conscientious reader of Nietzsche, Duchamp knew that in philosophy since Aristotle, the expenditure of male sperm has been understood as a loss of vital and creative power.84 No wonder that many artists throughout history have analogized the act of creation to intercourse, claiming to transform their sexual energy into art.

On the one hand, the preparation of Paysage fautif in 1946 no longer had much to do with ‘Rrose Sélavy.’ But it had everything to do with the creative eros that artists have traditionally claimed for themselves and with the fact that Duchamp had consistently rejected this notion since the 1910s. To such an extent that in the 1920s he playfully, ironically and always mockingly con‑ trasted the concept of artistic eros in his persona of Rrose Sélavy. Even in Apollinaire’ book Calligrammes Duchamp could have read the euphoric claim: “La grande force est le désir.”85 ‘Rrose’ served as his antithetical figure to the artistic topical eros that manifests itself as the almost libidinal creative force of the virile male artist and is constantly oriented toward the artist’s own work.

In the case of Duchamp (i. e. for Rrose Sélavy, with a rolled ‘R’), eros did neither refer to art and artistic creation nor sexual desire and procreation. 86 For Duchamp, eros was not related to the painter’s desire, his libido, his sexual abstinence (which would somehow be sublimated in art and through which artistic creation would somehow be eroticized). Duchamp did not subscribe to the notion of the sexual drive being sublimated through art and in art.87 For him, eros was life itself! Life itself was “a great pleasure,” but with constant “omission.”88 In contrast to the traditional and conventional artistic “desire to produce,”89 which Duchamp regarded as a form of repression, he espoused an “intense desire to live,”90 a desire for nothing but life. In a late interview, Duchamp would reveal: “For me, to live with pleasure is the first of the arts.”91 Éros? C’est la vie!92

If we now return to Marvin and Robert Lazarus, we understand that the invention of the name “Juan Ennui” in their dedication (fig. 2) was probably no coincidence. Ennui represented a fundamental tenet of Duchamp’s artistic in‑ activity. In his youth, Duchamp may have read in Nietzsche’s “Book for free spirits” with the title Human, All-too-human, that Nietzsche defines boredom/ ennui as a deficient absence of work.93 According to Nietzsche, people work excessively only to escape boredom. They work beyond their limits, but pre‑ cisely to avoid boredom: “Necessity,” says Nietzsche, “compels us to work, with the product of which the necessity is appeased; but the ever new awakening of necessity accustoms us to work. But in the intervals when necessity is appeased and asleep, as it were, we are attacked by ennui. What is this?” asks Nietzsche, only to answer: “In a word it is the habituation to work, which now makes itself felt as a new and additional necessity ….”94 Work to avoid boredom?

In the case of Duchamp, the situation was reversed: Ennui was presented as a means of evading the demands of work and as a fundamental aspect of one’s life. Throughout his lifetime, Marcel Duchamp consistently demon ‑ strated a lack of inclination towards the “necessity” for “the habituation to work” (Nietzsche). Conversely, even during his formative years, Marcel had exhibited a tendency to disengage from work, particularly artistic work. From an early age, he had shown a pronounced aversion to any form of artistic urge or creative pathos, and throughout his life he categorically had rejected the notion of work, particularly work as an end in itself! Duchamp recognized that human beings were perpetually engaged in a state of “travaux forces.”95 In his later years he would assert, “[t]hat’s our lot on earth, we have to work to breathe.”96 No one can “afford to be a young man who doesn’t do a thing. Who doesn’t work? You can’t live without working, which is a terrible thing.”97

In his lament, Duchamp explicitly cited the French socialist Paul Lafargue as a key witness to his own idleness and ennui. Lafargue’s demand for a “Right to be Lazy” is, in fact, precisely the antithesis of the obligation to work under capitalism. In his polemical pamphlet, Le Droit à la Paresse in 1880, Lafargue

polemicized against the capitalist “dogma of work” and especially the notion of the “passion of laborers for work.” He proposed an alternative approach to regulating labor, namely, rationing. Lafargue posited that, if work is “wisely regulated and limited to a maximum of three hours a day,” it could become an incidental matter for the proletariat: “a mere condiment to the pleasures of idleness.”98

In 1963 in the consumerist fashion magazine Vogue, Duchamp expressed regret that such a “[r]ight to be lazy” as advocated by Lafargue, “doesn’t exist now. You have to work to justify your breathing.”99 Work to legitimize breathing! This is to say that work is the reason and the justification for existence in capitalism. In contrast, Duchamp cultivated the comfort of inactivity, espe‑ cially as an artist. And with Duchamp, as we shall see, ‘artist’ means: “an‑artist” and, with Rrose Sélavy, it even means non-artist, something, again, I will call au-culist.

From an early age, Marcel Duchamp cultivated an almost complete aversion to any artistic “duty” and to the notion of the artist’s obligation to hard work. He rejected the notion of “faith” in “work,” espoused by the Parisian art publi cist and writer Émile Zola in his renowned text À la jeunesse, published in 1893. Zola commends the “enormous effort” that the artist must exert in order “to advance one step each day in one’s work.”100 It is evident that Zola, an author with whom Duchamp was undoubtedly familiar, did not espouse a capitalist work ethic. Nevertheless, his assertion appears to be predicated on the prom ise of artistic fulfilment, as evidenced by his demand that artists’ must “occupy their existence with some enormous toil, the end of which”101 is not even fore‑ seeable. In the view of Zola, work is “the only law of the world.” He proceeds: “Life has no other meaning, no other reason for being …. Life cannot be defined in any other way than by this movement which it communicates, which it re‑ ceives and bequeaths, and which, in short, is nothing but work, for the great final work, to the end of all time.”102 Obviously, Zola presents himself as the messiah of an artistic creative ethos.

Duchamp’s position on this matter was unequivocally opposed to this idea. He lacked any understanding of the pathos of creation (though he lacked it with amusement and indifferent serenity). Such an act of creation was a wide‑ spread attitude in the art of his time. But from an early age, Duchamp disagreed with the notion of making a sacrifice of life for the sake of an unending artistic work, on what Zola calls “la grande œuvre finale” (the great final work). Duchamp vigorously challenged Zola’s assertation that the purpose of life is to pursue artistic work exclusively. He also questioned Nietzsche’s premise that boredom is contingent on labor. In contrast, from the 1910s onward, Duchamp reha‑ bilitated a positive, independent form of boredom and idleness: his very own ennui (and once again: Roberta and Marvin Lazarus’ dedication “Juan Ennui” most likely alludes to this).

For Duchamp, however, ennui did not signify mere boredom, nor mental fatigue or spiritual solitude. It did not indicate listless heaviness, nor an ago‑ nizing “meaninglessness” or an oppressive “time suffering.”103 Conversely, for Duchamp, ennui signified in effect ‘the pleasure of time.’ For him ennui was the state of conscious inactivity. In contrast to Nietzsche’s concept of boredom, which is contingent upon work, Duchamp’s ennui was a lifelong enjoyment of inactivity. While in the 1920s it was personified by Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp would later repeatedly elucidate this concept with eloquence in his advanced years. 104

In 1967, for instance, Duchamp reminisced about his “truly bohemian life,”105 and offered the following summary: “Chess, a cup of coffee 24 hours are taken care of.”106 In a comprehensive interview with the journalist Pierre Cabanne in 1966, he elucidated that “basically I’ve never worked for a living.” 107 In a 1965 New York Times article, Duchamp was quoted as saying that it had always been “an occupation” for him to “sit in a chair and meditate.”108 The no‑ tion that the artist “feels obliged to make something”109 was abhorrent to him. Duchamp conceded, that work is probably our “lot on earth.”110 Nevertheless, one “can do anything but the same profession from the age of twenty until his death.”111 In lieu of pursuing a gainful employment, he claimed to have devoted his time to the expansion of “the way you breathe.”112 Preferring the act of living, Duchamp stated: “I like living, breathing, better than working.”113 (And this sentiment will be revised in detail in the context of Belle Haleine in the chapter “Beautiful Breath”).

To conclude and to get to the point: Duchamp’s lifelong attitude was encap ‑ sulated in his motto Éros, c’est la vie, which was expressed in his homophonic name Rrose Sélavy. However, as we shall see, Rrose Sélavy was not merely a sobriquet, it was also a mode of his au‑culistic (in)activity. From 1920 onward, Duchamp continued living out his resolute lack of ambition and his unre‑ strained inactivity under the alternative name Rrose Sélavy. Conversely, he employed his ennui, his “aversion” to art and his “mood of displeasure”114 to ac‑ tivate his motto Éros, c’est la vie in a distinctly au-culistic manner: as Rrose Sélavy.

Notes

1 Jacques Caumont and Jennifer Gough‑Cooper, Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy. 1887–1968 (Bompiani, 1993), n. p. (entry for November 10, 1961).

2 Ibid., n. p. (entry for December 11, 1959).

3 See William C. Seitz, The Art of Assemblage (Doubleday & Co., 1961). See also Stephan Geiger, The Art of Assemblage. The Museum of Modern Art, 1961 (Verlag Silke Schreiber, 2008).

4 Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1951 (replica based on the lost models from 1913 and 1916), metal wheel mounted on painted wood stool, 129.5 × 63.5 × 41.9 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

5 Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1950 (replica based on the lost model from 1917), urinal, 30.5 × 38.1 × 45.7 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art.