Edited by Claudia Banz

Volume 1

Edited by Claudia Banz

Volume 1

Tabita Rezaire and Her Cosmological Tales of Connection

Edited by Claudia Banz

Preface

Claudia Banz

Deep Constellations

Léa d. Allexandre

Tabita Rezaire’s Mamelles Ancestrales in the Context of Technoshamanism

Inke Arns

Calabash Transmissions and Cosmotechnics: World-Making in Tabita Rezaire’s Des/astres

Holly Bynoe

Sacred Plants at the Heart of Afro-Amazonian Cosmogonies

Marc-Alexandre Tareau The Life Aquatic and Beyond or Stories

Anja Melina Wegner

The Weltmuseum Wien’s new publication series WMW Now brings curatorial practice, research, and artistic reflection into open dialogue. This will expand the range of opportunities for discourse beyond the confines of collection and exhibition galleries. The series is intended as an invitation to engage with current issues in museum work from different perspectives. The first volume is dedicated to the artist, activist, and farmer Tabita Rezaire on the occasion of the exhibition Calabash Nebula: Cosmological Tales of Connection at the Weltmuseum Wien in 2025/26. Based in French Guiana, the artist presents a poetic and critical reconfiguration of knowledge, combining indigenous cosmologies, African spirituality, ecofeminist perspectives, and scientific findings into a visually and conceptually dense practice.

Working between the poles of collection, exhibition, and the present, Rezaire negotiates central themes that also challenge our curatorial practice: postcolonial continuities, global resource dynamics,

environmental crises, the relationship between technology and nature, and questions of memory and identity. Calabash Nebula is an excellent example of how art can be understood as an energetic space of knowledge – and the museum as a place of active engagement.

Five authors accompany this project with contributions from their respective fields: curator Inke Arns, environmental activist and writer Holly Bynoe, ethnobotanist Marc-Alexandre Tareau, marine biologist and behavioural scientist Anja Melina Wegner, and artist Léa d. Allexandre. Their texts open up multi-layered approaches to Rezaire’s work and allow us to experience how knowledge, practice, and aesthetics intersect in productive ways. I would like to thank them all for their precise, committed, and insightful contributions.

Claudia Banz Director, Weltmuseum Wien

Léa d. Allexandre

I’ve spent a fair amount of my life watching the Atlantic Ocean, facing my hometown in the French département of Finistère in northern Brittany. Here the coast is shaped by the winds and the sea; the trees have a hard time growing, leaving space to a wide, endlessly morphing sky. Guided by the tides, it follows atmospheric motions and cosmic rhythms. I’ve barely reached my 30s, and in my lifetime I’ve already witnessed changes in climatic phenomena. Winds which once blew from the north have been cast astray, now blowing from the south and other directions. Algae blooms have changed colouring in some parts of the estuaries. Black tar from the Amoco Cadiz1 covers the giant granite stones. And in these uncertain and saturated environments, I’ve met with many marine creatures, trying to adapt and become

1 Amoco Cadiz is the name of a ship that caused one of the biggest oil spills in the late 70s in France, at the north-western coast of the Finistère.

themselves in changing conditions that they do not control. I think they taught me one of the most invaluable aspects I hold dear, the ability to experience wonder.

The ocean depths and the infinite expanse of the cosmos have fuelled countless stories, oral tales, historical projections, sci-fi books, local myths, scientific research papers, prayers, and dreams.

In the acceleration of technological prowess these ‘last frontiers’ have been breached, and physical exploration have been possible for a few.

In her work Des/astres, Tabita Rezaire manifests her inquiry into megalithic architecture, cosmogonies, counter narratives, and aquatic journeys, which all coexist on the ceiling of a carbet,2 the maluwana.3

2 In French, a carbet is an open structure with a palm leaf roof. It is part of the vernacular architecture of French Guiana.

3 The maluwana is a decorated and revered piece of a tukusipan, a hanging ceiling inside the home, recounting traditional stories of the Wayana people in the French Guiana Amazonian basin.

Articulated in constellation, her film invites us to envision expansive stories about the cosmos, surrounding ourselves by the digital and spiritual sky. Organized non-hierarchically, the chapters in the film explore the links between the colonial legacies of French Guiana and its relations to space expansion, the indigenous tales of the Kapok tree in the Amazonian forest, the scientific space community of the

Kourou space centre, water tales of the Busunki,4 and many other timely encounters.

In Des/astres we meet with Joel Vacheron, researcher and writer in media and visual anthropology.

Part of his research has been to unravel the colonial heritage that today still impacts space exploration and expansion. Our skies, as imagined by Western scientific consensus, often appeal to the idea of an available void, an unexplored territory waiting to be elucidated by humankind.

‘There is reason, after all, that some people wish to colonize the moon, and others dance before it as an ancient friend.’5 During its lifetime, the Hubble telescope amassed a vast number of pictures of the cosmos. Launched in the 90s by NASA, it has spent 35 years photographing our cosmic skies, and made 1.6 million observations.

The final satellite pictures it produced have gone through intense procedures of selection, editing and post-processing. Through Dr. Elizabeth Kessler’s6 work, we see that the final published image of the Hubble Telescope is in fact the by-product of multiple stages of precise adjustment, resulting in a somewhat curated experience. As she explains, to highlight certain zones or create more spectacular images, scientists intentionally choose saturated colours and romantic tones, resembling very much the composition and colouring of the

4 Busunki is the water spirit of the Boni people in French Guiana.

5 Baldwin 1972.

6 Dr. Elizabeth Kessler is a visual culture researcher and author of Picturing the Cosmos.

nineteenth-century depiction of landscapes of the Midwest in North America.

The aestheticization of the depths is not a neutral affair.

When we approach the bottom of our ocean floors, colour disappears. As water absorbs sunlight, the idea of visibility is transformed. Red is the first to disappear to us at around 5 to 10 metres below sea level, orange next, fading at about 20 metres. Yellow and green also become invisible at around 50 metres. In this abyss of colour, creatures of the sea floor use bioluminescence and other senses to navigate the depths. For humans to ‘see’ the depths, however, bright floodlights mounted on submersibles or remotely operated vehicles and other strong artificial lighting is required. Our physical presence in the depths, aqueous or cosmic, is mediated through sophisticated technological instruments.

The exploration of these worlds through these technologies has resulted in the production of a colossal amount of images that has shaped our imagination about these ‘final frontiers’.

The Hubble images alone have led to the production of 21,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers, making it the most scientifically ‘productive’ telescope. We might question whether or not science is in need of imagery to produce valuable research data.

The presence of these sublime images in human media has shaped the collective consciousness far beyond the astronomical scientific community.

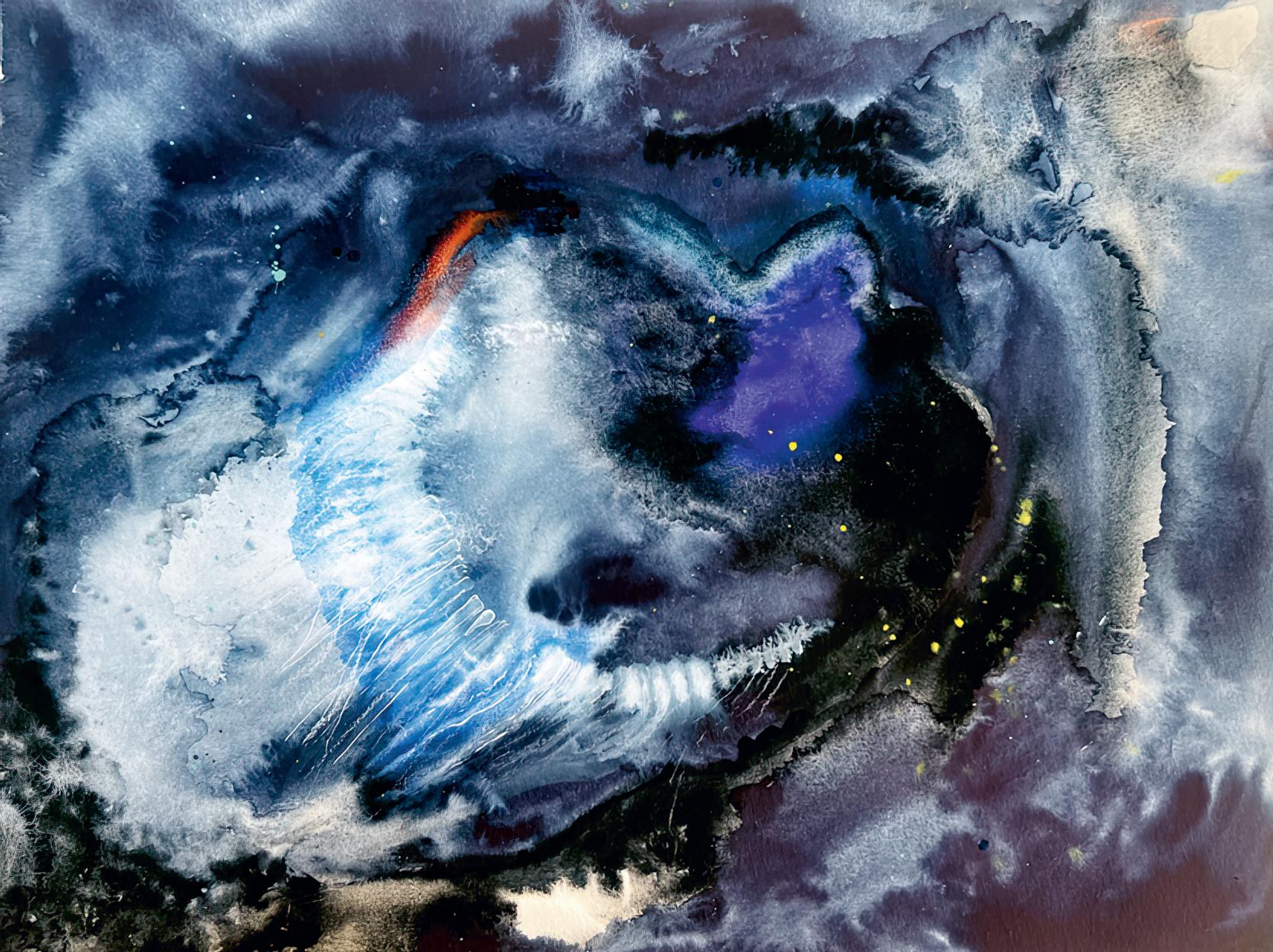

fig. 2 This visualization provides a three-dimensional perspective on Hubble’s 25th anniversary image of the nebula Gum 29 with the star cluster Westerlund 2 at its core.

The sudden appearance of deep-sea creatures in human media has created a strange paradox.7 Left ‘unexplored’ for most of human history, every scientific expedition has allowed for physical encounters with beings never met before. Because the deep sea is still largely unknown to science, we could say that we ‘know’ more about the moon than our seas. Less than 1 per cent of the oceans has been explored by scientists. But what does it mean to meet with new species, in the context of mass extinction?

In parallel with our skies being populated by 5G satellites from Starlink, we realise that our deep seas are attracting a worrying amount of attention, specifically from mining industries. More than half of the highly specialized deep-sea biology research expeditions are financed by governments and mining industries.8

Why are we going down into the depths? To cope with our demand for energy and technological objects like phones, laptops, electrical cars: we need cobalt, zinc, nickel, gold, silver, copper, and other rare minerals. In July 2025, the ISA (International Seabed Authority) will decide on the fate of life of the abyss, by providing final regulations on commercial operations in international waters.

Across the skies and the depths, a similar imperial logic operates: to conquer what is unknown, to extract what is valuable, and to ignore what cannot be monetized. These processes are still orchestrating planetary dispossession.

7 See Alaimo 2025.

8 See Ashford et al. 2025.

Across the layers of our universes, capitalism always finds ways to take.

Many of us in the West are made to believe in a universal human destiny of exploration whether among the stars or the depths, which leads to conceal the techno-capitalist infrastructures and political agendas that make them possible. In the depths, like in the cosmos, the concept of the unknown, the void, the obscured, the dark, the threatening, between fascination and menace, is part of a language that mirrors the rhetoric once used to justify the control of non-Western bodies and lands. These colonial continuities reveal a shared imperative to master and extract.

One day in the Finistère, a siphonophore9 made its ways to the shores, puzzling humans with its odd composite looks. Something between a jellyfish and an inflated cushion.

What does it mean to live in the age of extinction and still be ‘discovering’ creatures from the depths?

9 A siphonophore is an underwater organism made up of many individual, specialized organisms called zooids, which work together to function as a single entity.

How can we learn from their deep and slow aquatic ways? Without verbal

communication, how do we communicate knowing the risks of anthropomorphising them?

The siphonophore are beings composed of different bodies. Some species, like the Portuguese man o’ war, live near the surface. However, many siphonophores, including deep-sea species like Marrus orthocanna inhabit the midwater and deep-sea zones. Other species, like those in the genus Erenna, are found even deeper, between 1,600 and 2,300 metres. They function as a super-organism, composed of different parts, that decided to form a synchronized chorus. One breathes, another digests, one floats, another stings. A choreography of selves that stay together. Siphonophores do not compete with their own parts. As a plural being, they contribute to a body that floats and pulses with shared intention.

‘And what could I tell you that would help you remember how necessary you are in time of disposability?’10

Each part is as necessary as the other, each fulfilling a role and a vision that is carried within them. When language limits us, our bodies speak. When I’m floating on the surface of the ocean, my back faces below, and my chest is connected to the sky. I lie on the salty aqueous bed and it carries me, allowing me to let go of my weight. There is depth beneath me and so much is contained to this connecting body. If I open my eyes, I will feel a layer of sky blue gently dazzling my senses, accompanying the drifting current. I weigh in that connection. Right here. Now. When my body dissolves, I can finally feel the grief of 10 Gumbs 2020.

living in a crumbling world: where my breath and thirst are inhabited by molecules I will not process. What is the scale of our grief?

My womb is contaminated and my community is surviving unjust systems of exploitation. Do you feel how cold capitalism is?

I remember that I am held. She, salty water connects my pores, this only body that I have, a body with water as the main element. It remembers.

I remember the encounters, the marine creatures that inhabit the same land and seas.

I remember their curious ways, their playful attitude and the trust they put in me when they decide to stay in presence.

I remember that I am held.

Inke Arns

We are entering a circle formed by twelve massive stones. A video is projected onto the floor in the centre of this stone circle. In her video installation Mamelles Ancestrales (figs. 1, 2), Tabita Rezaire traces the megalithic stone circles in Senegambia, West Africa, erected between the third century BCE and the sixteenth century CE. Most of these over 1,000 stone circles are located within a strip along the Gambia River that is 100 km wide and 350 km long. Rezaire travelled to the stone circles of Sine Ngayène and Wanar in Senegal as well as Wassu and Kerr Batch in Gambia.1 In her video work, the

1 These four stone circles were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2006.

artist brings together stories from the guardians of these sites, observations from the local population, and other findings from astronomers, archaeologists, and theologians in order to uncover the secrets of the stone circles: her various sources see them as everything from petrified brides, burial sites, ancient observatories and ceremonial sites to spirit places and even sources of spiritual energy. At any rate, these stone circles have become the centre of Rezaire’s scientific, mystical, and cosmological research.