Oyster. Feminist and Queer Approaches to Arts, Cultures, and Genders

Hongwei

Oyster. Feminist and Queer Approaches to Arts, Cultures, and Genders

Hongwei

Susanne Huber, Änne Söll (Eds.)

Advisory Board

Daniel Berndt, Universität Zürich

Cuneyt Cakirlar, Nottingham Trent University

Jill H. Casid, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Brian Curtin, Chulalongkorn University Bangkok

Henriette Gunkel, Ruhr-Universität Bochum

Lisa Hecht, Philipps-Universität Marburg

Antje Krause-Wahl, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main

Lex Morgan Lancaster, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Zintombizethu Matebeni, University of Fort Hare

Fiona McGovern, Berlin

Christiane Kruse, Mona Behfeld, Ileana Pascalau, Sven Christian Schuch (Eds.)

Printed with the kind assistance of Muthesius University of Fine Arts and Design, Kiel.

ISBN 978-3-68924-215-2

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-68924-036-3

DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783689240363

ISSN 2940-7265

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025935609

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston, Genthiner Str. 13, 10785 Berlin

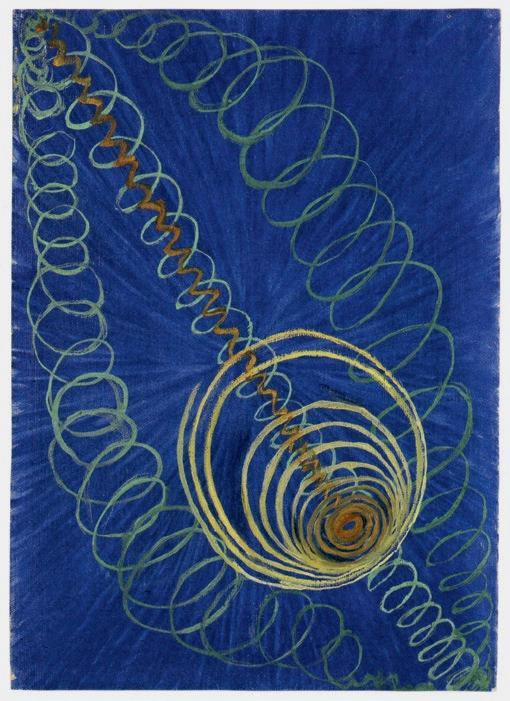

Cover illustration: Mona Behfeld and Florian Péus, Hamburg

Cover design, layout and typesetting: Jan Hawemann, Berlin

Printing and binding: Beltz Grafische Betriebe GmbH, Bad Langensalza www.degruyterbrill.com

Questions about General Product Safety Regulation: productsafety@degruyterbrill.com

Alexandra Ivanciu and Jolanta Nowaczyk

About Flowers and Choice

DA SIND WIR*

DA SIND WIR* – Beginning to Imagine Queer-Feminist Cities

Mieke Bal

Listening and Seeeing as the Foundation of Culture

Mona Behfeld

Sichtbar werden mit den Mitteln der Kunst?

Analyse fotografischer Frauen repräsentationen im Kontext kunstvermittelnder Medien

Julia Meer

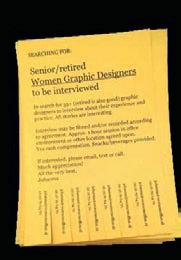

The F*word – Sichtbarmachung eines Krümels

Friederike Nastold / Thari Jungen

Sichtbarkeit als ästhetische Strategie mit politischer Wirkung?

Ileana Pascalau

SA/VOIR. Wisdoms of the peintres-femmes in the context of the French Revolution

Regine Eurydike Hader

Queerer Glanz zwischen Hypervisibilität und zurückgewiesenen Blicken

Mayte Gomez-Molina

You can/’t see me through my avatar. Camouflage, protection and feminist, black and queer resistance techniques in 3D and VR contemporary art

Carmen Kleykens Vidal

Visualization of XR artists*: Issues, trends, and dissident actions in virtual performativity

But most of all, I think, we fear the visibility without we cannot truly live. […] Even within the women’s movement, we have had to fight, and still do, for that very visibility which also renders us most vulnerable, our Blackness. [. . .]

And that visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which is also the source of our greatest strength.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action (1984/2007)

“Visibility” is a keyword in the media-constructed world—getting seen is a prime prerequisite for art and design. Visibility is a struggle for public standing, for media attention, space, recognition, participation—for power. The four chapters of this volume address the complex problem of visibility, taking the perspective of queer feminist art and design from the modernist era to the present. Art-theoretical and art-historical perspectives on the topic are discussed and positions from art and design are shown. The essays are the product of a symposium that took place in June 2023 in the university gallery space of the Muthesius University of Fine Arts and Design in Kiel.

Historically, the visibility of art and design has been secured by the Western artistic canon. This canon was developed over centuries, defined socio-politically as a part of cultural identity, anchored institutionally as well as academically, and passed down through the rituals of art (exhibitions, award ceremonies, etc.). The first chapter of this volume begins with a set of urgent questions: Where does queer feminist art stand relative to the tradition of the artistic canon? What conditions must be met for feminist and queer art and design to become part of the canon? What kinds of queer feminist art can and will get to be part of this canon? Is it even a goal to be or become part of an (expanded) canon?

Queer and feminist art have been overlooked and made invisible well into the twentieth century—marginalized and/or excluded from the art discourse and the establishment. What are the opponents and (public) interests hindering the visibility of queer feminist art? What arguments get introduced to marginalize or suppress art and design by feminist and queer persons? In which social contexts is the reception of feminist and queer art impossible, i.e., suppressed, marginalized, made invisible? Who has defied the marginalization and erasure of queer feminist art and design, and with what arguments?

The Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) and her work offer an example in the history of devaluating women’s art with the aim of excluding it from the canon of abstraction, whose beginning a patriarchal art theory dates with the male “pioneers” at the start of the twentieth century. Christiane Kruse’s essay reveals a dual victimization of af Klint’s art that aims to confine it to the spiritual context of its time in order to exclude it from the historical art discourse and the exclusive circle of the “pioneers of abstraction”. A patriarchally structured art system cements power relations that demand visibility not as a result but as a prerequisite for genius and originality. Feminist art theory has succeeded in making Hilma af Klint’s art internationally visible and successful as a highly original position in abstract art. The next step is to banish exclusive art criteria to the realm of male mystification.

Post-digital environments suggest transparency and limitless connectivity, while subtly creating new mechanisms somewhere between inclusion and exclusion, centre and periphery. What does this mean for a place that exhibits art and creates communal infrastructures? And can a queer feminist artistic and curatorial practice in particular respond to these altered visual relationships by producing, preventing, or changing them? Agnieszka Roguski presents IN:VISIBILITIES, a curatorial program of the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung 2021/22 in Hohenlockstedt (Schleswig-Holstein). Through an interweaving of different formats, media, and spaces, the program explores the visibilities and invisibilities determining art’s becoming public in the post-digital age. The focus is on queer feminist practices and questions of researching, talking, hosting, and showing, which will be presented in the form of two concrete project examples: GOSSIP and EXCLUSIVITIES. The essay reflects on an institutional framework as an ongoing process that emerges from the diversity and intersection of formats and their specific forms of publicity.

Valentina Iancu explores the emergence and significance of queer art exhibitions in Romania, contextualized within a history of LGBTQ+ oppression and religious conservatism. Iancu traces the evolution of queer visibility from initial struggles against criminalization to current art practices that challenge the heteronormative national narrative. Through examining key exhibitions, the essay delves into the question of how queer artists navigate themes of identity, resistance, and representation. Employing frameworks like drag and “freak theory,” the study reflects on the aesthetic and politi-

cal tensions inherent in queer Romanian art as it confronts a history marked by sin, sickness, and erasure.

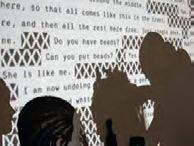

In an interview with Hanna Schaich, Sven Christian Schuch explores her artistic practice as a queer video artist, filmmaker, immersive performance poet, and activist. Schaich’s works, which often contain autobiographical elements, break through patriarchal, neo-capitalist structures and set radical aesthetic and thematic accents. Schaich and Schuch discuss terms such as community and sexuality as concepts that foster identification and act as communicators of social conditions. The key questions here are: How much (in)visibility and transparency do marginalized groups need? What does radicalism mean in art, especially in the context of queer feminist perspectives? And how can the concept of queering as a disruptive artistic practice help develop an open, diverse view of bodily and human images and challenge existing norms?

In the second Chapter, we interrupt the theoretical essays to allow artists and designers to have their say and take the concept of visibility as a starting point for their own artistic productions. Their contributions juxtapose image and word to create a dialogue and expand the theoretical explorations of the first, third, and fourth chapters with a sensual, aesthetic dimension. They are to be understood as deliberate statements independent of the book’s layout.

The performance duo ClaudeHilde , consisting of Margarita Breitkreiz and Julia Thurnau, kicks things off. Their “Mustache Manifesto,” part of the performance Artist at Work. Social Sculpture that was put on as part of the symposium, addresses the downside of visibility and criticizes self-optimization as a reflection of gender inequality and the working conditions of freelance artists by proclaiming a “revolution of lazy women” and providing the “ultimate recipe for laziness.” The artists Stella Meris and Krys Huba each present a graphic re-enactment of their lecture performance Collective Transmutation on a double-page spread. These works explore bodily perception and the potential of collective healing processes within socio-political and patriarchal structures. The double-page spreads link poetic text fragments with visual elements. The artist Almut Linde’s work consists of six photographs and an accompanying text. Linde’s photographs show the actress Juliane Köhler interacting with people from her personal and professional environment, creating moments of forced closeness and revealing the different reactions to intimacy and distance of those involved. Daniela Burger explores the question of whether or not magazine design can be feminist. Using layout examples from Missy Magazine, which Burger co-edited as art director from 2010 to 2023, Burger examines how to anchor queer feminist concerns in design parameters and summarizes the extent to which visual design tools can be used to make power relations visible and create new forms of expression for the

Christiane Kruse

“There is a disjunction between speaking and seeing, between the visible and the articulable: ‘what we see never lies in what we say,’ and vice versa.”1 In Strata or Historical Formations: The Visible and the Articulable (Knowledge), Gilles Deleuze comments on Michel Foucault’s concept of “‘sedimentary beds’ [that] are made from things and words, from the visible and the sayable, from bands of visibility and fields of readability, from contents and expressions.”2 Foucault, Deleuze remarks, noticed in his later works that he

[did] not sufficiently show primacy of the systems of a statement over the different ways of seeing or perceiving. […] For him, the primacy of statements will never impede the historical irreducibility of the visible—quite the contrary, in fact. The statement has primacy only because the visible has its own laws, an autonomy that links it to the dominant, the heautonomy of the statement. It is because the articulable has primacy that the visible contests it with its own form, which allows itself to be determined without being reduced.3

In this text, Deleuze presents a theory of visibility in Foucault’s thought that he considers essential: “Foucault continued to be fascinated by what he saw as much as by what he heard or read, and the archeology he conceived of is an audiovisual archive.”4

In the following, I will take Hilma af Klint as my example to address how, with what arguments, and under what circumstances her art was invisible, how it was only recognized and made visible as autonomous art in late 2013, and, above all, who rendered her art visible or invisible and with what arguments. I have selected an example from non-figurative art in order to exclude as far as possible any (female) gender identifica-

1 Gilles Deleuze: Foucault, trans. and ed. by Seán Hand (Minneapolis and London: Athlone, 1988 [first ed. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1986]), 64.

2 Ibid., 47.

3 Ibid., 49–50.

4 Ibid., 50.

2

Klint, Primordial

perfectly respectable handbooks in the sciences as Kandinsky and the theosophists did.”19 What counts is “the idea that by inner perception the artist is able to reach hitherto untouched levels of reality, even cosmic laws.”20 Yet he nonetheless insists on a distinction with reference to Kandinsky. Kandinsky’s work “is primarily a work of art, and to the majority of us this is the essential thing.”21 The majority of art historians will see Kandinsky’s work as art; he no longer mentions af Klint here, leaving us with the impression that since her works remain essentially in the theosophic context, we are to deny her an identity as artist.

In terms of the pioneering work, an idea widespread in art scholarship that I will discuss later, the rediscovery of af Klint means that she can only be accorded last place due to her medium-induced image-making process. Yet did anyone bother to write in the exhibition catalogue about the foundation courses she completed at the technical

19 Ibid., 150.

20 Ibid., 150.

21 Ibid., 150.

3 Typen von Proto-Elementen, in: Annie Besant und Charles W. Leadbeater: Okkulte Chemie (1908), p. 11

school in Stockholm when she was 18, and did anyone point out that she studied for five years (1882–1887) at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm and graduated with the “best grade”?22 Who mentioned that the art academy in question gave one of its coveted studios to her and two other artists?

In the same exhibition catalogue, the Swedish art historian Åke Fant, known for being the first to bring Hilma af Klint’s work to the attention of scholars,23 is particularly keen to assess the artist’s work as not being autonomous, in order to then deny it its artistic identity. This already begins in the first paragraph: “She neglected the study of languages and is said to have understood only the Scandinavian ones, a factor that may have intensified her subsequent isolation from the artistic movements of Europe.” 24

22 Exh. cat. Hilma af Klint, 278.

23 Åke Fant: “Synpunkter på Hilma af Klints måleri,” in: Studier i konstvetenskap tillägnade Brita Linde, eds. Margaretha Rossholm Lagerlöf, Birgitta Sandström (Stockholm: Stokholms universitet, Konstvetenskapliga instituten, 1985), 45–54.

24 Åke Fant: “The Case of the Artist Hilma af Klint,” in: exh. cat. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, ed. by Maurice Tuchman, Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1986–1987 (New York, NY: Abbeville Press, 1986), 155–162, esp. 155.

Daniela Burger

Editorial / Impressum — 3

Aufschlag

Radar — 8

Banden bilden — 12

Lieblingsstreberin / Konsumfail — 13

Work Work Work — 14

Hä? — 15

Kultur & Gesellschaft

Buch: Nadia Shehadeh — 17

Pop: Fever Ray — 22

Literatur: Eva Tepest — 24

Game: Keiken — 20

Politik & Protest

Real Talk: Sri Lanka — 35

Essay: FLINTA — 38

Reportage: Comicgewerkschaft — 40

Kann Grafikdesign feministisch sein?

Wie funktioniert queere Magazingestaltung?

Welche Möglichkeiten eröffnet unordentliches Gestalten? Kann Design dekolonisiert werden? Wie werden

Gestaltungsprozesse selbstermächtigend?

Und was ist das eigentlich genau, Typografie? Anlässlich des Grafikrelaunchs

Missy stellen wir eurozentristisch, männlich und heterosexistisch geprägte

Dossier

Bisexuell: 15 Seiten Frühlingsgefühle — 52

Sex, Körper & Style

Edutainment

Musik — 77

Podcast — 81

Film und Serie — 83

Theater: Anti War Women — 26

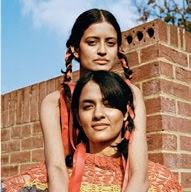

Bildstrecke:

Keerthana Kunnath — 28

Titel

Giulia Becker: Richtig nuts! — 46

Designdiskurse und Praktiken auf den Enjoy the ride!

Konzeption:Daniela Burger,LisaKlinkenberg &StefanieRau Beratung:Anja &Rebecca

Literatur und Comic — 89

Abonnement — 98

Kunst — 103

Missy präsentiert — 104

Kolumne — 106

Leser*innenbriefe / Mitarbeiter*innen — 6 / 7 DIE NÄCHSTE MISSY ERSCHEINT AM 15. MAI

Pillow Princess — 69 Eizellenspende — 70 Styleneid — 72 In the Mood — 73 Bunte Klamotten — 74

Was ist Missy?

Das Missy Magazine ist eine Zeitschrift mit den Themenschwerpunkten Pop & Kultur, Politik & Gesellschaft, Mode, Körper und Sex. Es versteht sich als intersektional und queerfeministisch: alle Menschen, unabhängig von ihrem Geschlecht, ihrer Sexualität und ihrem Körper, sollen dieselben Freiheiten und Rechte haben.

Konkrete Themen in Missy sind zum Beispiel das Infragestellen binär kodierter Geschlechteridentitäten, die Analyse von Privilegien weißer Frauen, wie wir mit Sexismus, Rassismus und einem Rechtsruck in der Gesellschaft umgehen, was sexuelle und reproduktive Selbstbestimmung heute bedeutet, oder auch alles rund um Popkultur.

Missy wurde 2008 gegründet und erscheint im Selbstverlag.

sein? Magazingestaltung? Design ächtigend?

Typo-

Grafikrelaunchs von cisgeprägte den Kopf.

DanielaKlinkenberg RauAnjaKaiser RebeccaStephany

↑ Ressourcen zum Dekolonisieren: Shamma Buhazza

@shamma.buhazza

↑ Queeres Publizieren: Queer Reads Library, Flyer

↑ Heteronormative Symboliken neu denken: Coco Guzman, „genderpoo“, Gendersymbol für Toiletten

↑ Politischen Bewegungen eine Erscheinung g geben: Elisabeth Michel (Elmi Design), Black Lives Matter Berlin ↓ und: Black Panther Party Logo, Ruth Howard & Dorothy Zellner, 1966

→ Eingriff in typ Normen: „Bye bye binary, gender·queer·glyph“, Hélène Mourrier

Heureka!“ Endlich ist es mir klar geworden: Mein lang anhaltender emotionaler Zustand, der mir mütterlicherseits vererbt wurde und sich in meiner Wahlfamilie wiederfindet (Frauen mit und ohne Uterus, Bisexuelle, Uranisten, Prekäre, sich Wandelnde, Jungenhafte, Kindliche, verschieden Ableisierte, unterschiedliche Menschen of Color, von denen ich in diesem Text als „wir“ spreche), hat einen Namen. Die psychologische Fachsprache bestätigt, dass wir das haben, was die Griechen phobos („Angst“) vor chairo („sich freuen“) nannten: eine Abneigung gegen das Glücklichsein. Ja, wir haben Cherophobie, liebe Freund*innen, und es ist ein langfristiges Designprojekt. Das erklärt vieles, u. a. das dumpfe Gefühl, dass etwas Schlimmes passieren wird, wenn wir uns in vollen Zügen amüsieren. Wir sollten stattdessen die Euphorie des Lebens meiden, um seine Folgetragödien zu verhindern. Als eigensinniges weibliches Kind bestätigte sich mir diese Argumentation – „das Unglück folgt dem Glück“ – bereits früh: jedes Mal, wenn ich trotz der „Lachen bringt Tränen!“-Warnung meiner Großmutter, die dieses Motto in ihrem patriarchalen Haushalt ständig unter Beweis stellte, in Gelächter ausbrach. Mit der Zeit hat sich diese erlernte Vorsicht vor dem Glück in einen größeren politischen Fatalismus verwandelt, mit dem Glauben, dass jede Freude, die auf einen Sieg folgt, ein Unglück mit sich bringt: Bevor wir uns an irgendeinem Ort über die Entkriminalisierung der Abtreibung freuen können, geschieht anderswo ein weiterer Femizid oder ein Hassverbrechen; während wir die kollektive Aufdeckung institutionalisierter Schikanen feiern, findet woanders eine weitere Masseninhaftierung Andersdenkender statt; die Überwindung von Grenzen wird von polizeilichen Schießereien überschattet; die Folgen der gewonnenen Sichtbarkeit der einen werden durch die anschwellende Prekarität der anderen ersetzt.

Screenshots from “About Flowers and Choice“

Ileana Pascalau

Arrogant enemies of our sex, you who wish to know everything in order to overwhelm us with the weight of your learning, do you not fear that we, as new Amazons, might avenge the crimes of your selfishness on your descendants? The ignorance to which you would reduce us would excuse our misdeeds, and the astonished nations would shudder but applaud our efforts to regain our self-respect.1

In the year 1789, an artist by the name of Marie-Victoire Lemoine had intentions every bit as revolutionary as her compatriots’. She was working on a painting that would not only highlight the outstanding achievements of women artists in the last quarter of the century, but also flag them up for the whole world to see (Fig. 1). L’intérieur d’un atelier de femme peintre (The Interior of a Woman Painter’s Studio) was first shown in 1796, at Paris’s most important art venue: the Salon of the Academy. Thus, precisely within the very exhibition space that had barred female participation until 1791, Lemoine chose to make a visual statement in which art is depicted firmly in the hands of women, at work in a studio exorcized of any male presence.

The painting offers insights into the dynamics of a studio where a teacher and her pupil have joined forces in the name of art and art education. What has been given to us to reflect upon is a visible expression of the ideals of artistic agency that generations of women have dreamed of: to freely exercise one’s artistic vision, to paint in one’s own studio a historical subject on a canvas of considerable size, to teach art and to benefit from a woman’s artistic training. United by a will to see and a will to know, 2 the protag-

1 Albertine Clément-Hémery, Les femmes vengées de la sottise d’un philosophe du jour, ou Réponse au projet de loi de M. S**—M**. [Sylvain Maréchal] portant défense d’apprendre à lire aux femmes, par Madame ****, Paris 1801, 59.

2 Michel Foucault, La volonté de savoir: Histoire de la sexualité 1, Paris 1976.

1 MarieVictoire Lemoine, The Interior of a Woman Painter‘s Studio, 1789, Oil on canvas, 116.5 × 88.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum, New York, Gift of Mrs. Thorneycroft Ryle, 1957, accession no. 57.103

onists are immersed in the realms of the voir and the savoir actively shaping them. Nothing seems to stand in the way of the femme peintre to whom the title refers. She freely pursues her profession and even extends this liberty through educational practices.

From the moment it was exhibited, the painting sparked curiosity about the identities of the figures depicted. Who could the artist draped à la grecque be? And who was the diligent student concentrated on her drawing? Art historians continue to debate various interpretations: some propose that it might represent Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, the renowned painter whose studio was near the one where Lemoine was studying and who allegedly trained the latter as well, while others believe it could be a self-portrait featuring one of Lemoine’s younger sisters, Marie-Élisabeth or Marie-Denise.3 Never-

3 Joseph Baillio, “Vie et oeuvre de Marie Victoire Lemoine (1754–1820),” in: Gazette des BeauxArts 127, April 1996, 125–163; Mary Sheriff, “Marie-Victoire Lemoine,” in: Dictionnaire Siefar 2005. https://siefar.org/

theless, the ambiguity surrounding these identities strategically shifts the focus to a broader question: what was a woman artist capable of on the eve of the French Revolution? Whoever these figures are, they seem to know very well what they are doing. It’s by no means a coincidence that this artwork was shown in an exhibition space “as political as elections, [where] brushes and chisels are as many tools of the party as the pen”.4 If there were to be a demonstration of female artistic power, it would have to reach the retina of the “master’s eye,” as Mieke Bal has termed the patriarchal model of visual hegemony.5 Such a vision was most eloquently embodied by the Salon. Together with the Academy, it functioned like a cyclopean orb, jealously defending its monocularity against competing female views. Marie-Victoire Lemoine’s visual rhetoric seems to challenge the authority of this “master’s eye” in every way. It is this challenge that my paper seeks to address. I will examine how, by engaging with the artistic discourse and the gender politics of its time, L’intérieur d’un atelier de femme peintre succeeds in shaking off prevailing prejudices about the role of women in art. At the same time, I intend to trace Lemoine’s effort to disorient the coordinates of the existing visual system in order to redraw the chart from another perspective. To connect the dots in the constellation between sight, knowledge, and power is relevant to this type of approach. It would be in the spirit not only of Foucault, who emphasized the interdependence of these concepts, but also of the feminist thinkers of the Enlightenment. The harsh words of the writer Madeleine de Puisieux show an acute awareness of the intrinsic relationship between savoir and pouvoir: “But let the truth speak for once. Why do they [the men] work so hard to keep us away from knowledge to which we have as much right as they do, if not for fear that we might share it with them, or even surpass them?”6

As in I see myself

Marie-Victoire Lemoine deliberately marked her debut at the Academy Salon by depicting a studio inhabited by women whose identities are defined through their artistic professions. This was not her first exploration into the theme of the female artist, but part of a process that had started earlier, with several works presumed to be self-portraits. Let us look at one of these paintings, which shows its subject close-up at work, with a play of light enhancing her intense gaze and active hands, brimming with an en-

mediawiki/fr/index.php?title=Marie-Victoire_Lemoine&oldid=7891 (accessed September 14, 2024); Carole Blumenfeld, “Je déclare vivre de mon art”: dans l’atelier de MarieVictoire Lemoine, MarieÉlisabeth Lemoine, JeanneÉlisabeth Chaudet, MarieDenise Villers, exh. cat. Musée Fragonard Grasse, Montreul 2023.

4 A. Jal, Esquisses, croquis, pochades, ou tout ce qu’on voudra sur le Salon de 1827, Paris 1828, IV.

5 Mieke Bal, “His Master’s Eye,” in: David Michael Kleinberg-Levin (ed.), Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1993, 379–405.

6 Madeleine de Puisieux, La femme n’est pas inférieure à l’homme, London [i. e. Paris] 1750, 64.

Marie-Victoire Lemoine and the quest