Christina Bartosch

Christina Bartosch

Strategies in the Propagation of an Avant-garde 1908–1915

Research results from: Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P29997-G24

Published with the support of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): 10.55776/PUB 1058-G.

ISBN 978-3-11-075584-8

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-075590-9

DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110755909

This publication is licensed, unless otherwise indicated, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and source, link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate any modifications.

The images or other third-party material in this publication are covered by the publication’s Creative Commons license, unless otherwise indicated in a reference to the material.

If the material is not covered by the publication's Creative Commons license and the intended use is not permitted by law or exceeds the permitted use, permission for use must be obtained directly from the copyright holder.

Despite careful editing, all information in this publication is provided without guarantee; any liability on the part of the author, the editor, or the publisher is excluded.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2025 the author, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. This book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com.

Copyediting: Lance Anderson

Cover illustration: Installation view of so-called ‘Cubist room’ (Salle XI) at the Salon d’Automne exhibition of 1912. Copyright: L’Illustration, Paris. Layout and typesetting: Andreas Eberlein, aromaberlin

Printing and binding: Beltz Grafische Betriebe, Bad Langensalza www.degruyter.com

Questions about General Product Safety Regulation productsafety@degruyterbrill.com

9 Acknowledgements

11 Note to the Reader

13 Introduction

13 Questioning the ‘fathers of abstraction’

17 The interpretation of behaviours as strategies

18 Data-based: The method explained

21 Abstraction as ‘symbolic capital’, the exhibition as ‘field of cultural production’?

22 The structure of the book

27 The Form and Function of Modern-Art Exhibitions in the Early Twentieth Century

27 Quantifying exhibition history

28 The development of avant-garde exhibitions and the launching of abstract art on the public (1908–1915)

34 Strategies in the Presentation of an Avant-Garde

34 Target the audience

39 Experimenting at the periphery

41 The artist group as incubator

44 Dimensions speak: statements expressed by the inch

46 Chromatic coordination

50 The Impact of Exhibiting Abstraction: The Propagation of an Avant-Garde

50 Boronali and the hoax of abstraction

52 One consequential Salon: the exhibition as propeller

54 Successful strategies?

56 Conclusion

61 Introduction & Disclaimer

62 Tentatively Exhibiting Abstraction: Balla’s Behaviour with Di erent Audiences

62 Introduction

62 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

69 Balla’s exhibition strategy

74 Conclusion

76 Boccioni: The Coexistence of Figuration and Abstraction

76 Introduction

77 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

83 Boccioni’s exhibition behaviour

89 Conclusion

91 Kandinsky Strategizing: How to Target Various Audiences at Once

91 Introduction

92 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

98 Kandinsky’s exhibition strategy

103 Written support: Kandinsky’s publication strategy

105 Conclusion

106 When Less Is More – Kupka’s Concentrated Exhibition Activity

106 Introduction

107 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

113 Kupka’s exhibition behaviour

117 Conclusion

119 Suprematist Exhibition Behaviour: Malevich at the Centre of Attention

119 Introduction

120 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

127 Malevich’s exhibition strategy

133 Conclusion

134 Mondrian’s Consistency towards Abstraction

134 Introduction

135 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

141 Mondrian’s exhibition strategies

145 Conclusion

147 Picabia: Ambassador of Abstraction

147 Introduction

147 Exhibitions: statistics and geographical distribution

155 Picabia’s exhibition strategy

158 Conclusion

160 Women Artists Exhibiting (Abstraction?)

160 Introduction

162 Quantitative analysis

168 Conclusion

169 Première for Abstraction: Kandinsky at the Sonderbund in Düsseldorf, 1910

169 Introduction

170 Context: the Sonderbund and Kandinsky

171 The 1910 exhibition of the Sonderbund: content and abstraction

176 Reception of Kandinsky’s works at the Sonderbund exhibition, 1910

177 Conclusion

179 Kandinsky Continues: The NKVM’s Ausstellung II, Turnus 1910/11 in Munich, 1910

179 Introduction

180 Context: the NKVM and Kandinsky

182 Ausstellung II, Turnus 1910/11: content and abstraction in Munich in 1910

187 Artist’s writings and reception

188 Conclusion

190 From Munich to Moscow: Kandinsky’s Abstraction at the Jack of Diamonds Exhibition, 1910

190 Introduction

191 Context: Jack of Diamonds and Kandinsky

193 Jack of Diamonds: content and abstraction

196 Artist’s writings and reception

198 Conclusion

199 Picabia as Kandinsky’s First Follower at the Salon de Juin, Rouen 1912

199 Introduction

200 Context: the Société Normande de Peinture Moderne and Picabia

201 Salon de Juin: content and abstraction

205 Artist’s writings and reception

206 Conclusion

208 Abstraction Double Bill: Kupka and Picabia at the Salon d’Automne,Paris 1912

208 Introduction

208 Context: the Société du Salon d'Automne, Kupka and Picabia

209 Salon d’Automne, 10e exposition: content and abstraction

212 Artists’ writings and reception

215 Conclusion

216 Total Abstraction: The First Fully Abstract Exhibition: Picabia in New York, 1913

216 Introduction

216 Context: Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and Picabia

217 An Exhibition of Studies Made in New York, by François Picabia, of Paris: content and abstraction

221 Artist’s writings and reception

224 Conclusion

226 Famous Last Words – So What?

227 A1: Exhibitions and Exhibited Artworks

313 A2: Comparative Table of Exhibition Statistics for the Seven Male Artists

315 A3: Table of Exhibitions by the 13 Women Artists

323 A4: Methodology Extended: Coding the Dataset

333 Register of Artist Names

336 Table of Figures and Tables

339 List of References

349 Illustration Sources

359 Full List of Exhibitions and Exhibited Artworks

In this study, I repeatedly use the terms ‘work’ and ‘catalogue entry’. While ‘work’ stands for the individual work of art, the ‘catalogue entry’ stands for its presentation at exhibition and thus it having an entry in the exhibition catalogue. (‘Catalogue entry’ should therefore not be confused with catalogue raisonné number.) erefore, if shown in more than one exhibition, a single work can result in several catalogue entries.

Avant-garde

I am aware that the term ‘avant-garde’ and its derivatives (such as ‘avant-gardist’) has had contested meanings over the course of the twentieth century. In fact, the term ‘avant-garde’ has led to an oversimplified understanding of certain aspects of art history, particularly Modernism. Despite its shortcomings, ‘avant-garde’ and its derivatives will still be used in this book, partly for lack of a better term. It is, however, a concept that I nevertheless wish to challenge to some degree in the present publication by showing that it is impossible to clearly demark the limits between the ‘avant-garde’ and less radical or even conservative art styles. eir actors cannot be neatly separated into just one camp; there is de facto regular overlap between them, as some of the results of my study will show.

Nevertheless, in the present context, the terms ‘avant-garde’ and ‘avant-gardist’ are mostly used in the sense of an art practice that distinguishes itself from the general practice en vogue at the time to create a kind of art that is unprecedented and consciously pushes the boundaries of what is known and accepted at the time of its creation.

Art-historical discourse has made the time around 1910 the moment that abstraction was ‘invented’. I am aware that this sentence is highly problematic in many ways, not least because of its imprecision. Numerous publications repeat this (mis)conception, from entire exhibitions and their catalogues dedicated to the topic (for example, MoMA’s 2013 show Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925), to monographic works about the various actors– first and foremost the artists themselves– seen as responsible for this (by all means certainly ground-breaking!) ‘invention’.¹ As Raphael Rosenberg has repeatedly shown since 2007,² abstraction was not in fact invented around 1910. Abstract images– or to use Rosenberg’s more precise term, amimetic images– existed long before Kandinsky’s abstractions or Malevich’s Quadrilatère (better known today as his Black Square), only they were not always considered art, let alone exhibited (at least not as such). Rosenberg claims that it was Kandinsky who, mainly through his writings, elevated (his own) amimetic images to the level of (capital A) Abstract Art, thus paving the way for the reception of this (not quite so new) innovation. Immediate predecessors who had produced abstract images in the nineteenth and early twentieth century were, for example, Hilma af Klint and Leopold Stolba. Slightly older examples of abstraction can be found in Georgiana Houghton’s works, or in drawings by JMW Turner and the writer Victor Hugo, among others, as Rosenberg convincingly shows. e innovative nature of some of these artists’ works has recently been acknowledged by respected international museums in the form of specially dedicated exhibitions. Hilma af Klint was granted a large exhibition (2018–2019) at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, while the Lenbachhaus in Munich simultaneously presented the art of Georgiana Houghton and Hilma af Klint (and that of Emma Kunze– irrelevant in the present context). Why have we never– or rather only very recently– come into contact with the names of artists that preceded the largely overtold story of the ‘invention of abstraction’, as approved, retold, and enshrined by the canon? Had the so-called ‘fathers’ of abstraction (Kandinsky & co.) even heard of these names and seen the pictures that these earlier artists had created?

e process I have just described anticipates the very concept to which this book is dedicated: the importance of exhibitions for the visibility and propagation of new ideas in art. Were these abstract artworks, by the so-called ‘fathers’ of abstraction as well as their predecessors, exhibited publicly around the time of their creation? If so, what impact did that have on the still-ongoing process of ‘invention’? Focussing on the years 1908 to 1915,

1To name just a few examples: Duchamp 1957, pp. 156–157; Lemoine 2003; Maloon 2010; Dickerman 2012. 2Rosenberg 2007, 2011, 2015, 2017.

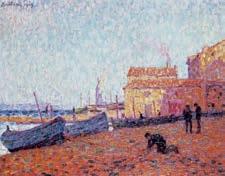

Boronali and the hoax of abstraction

In 1910 abstract art was not yet established in the visual arts or among artist circles, and many artists who were part of modern-art movements and the avant-garde did themselves not necessarily agree with this move towards the non-figurative.5² A famous episode from an exhibition is particularly telling: the case of the picture titled Et le soleil s’endormit sur l’Adriatique, exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1910 and, according to the catalogue, supposedly the work of the Italian painter J-R Boronali (see fig. 8).5³ e canvas presents the viewer with a largely non-representational image in which the coast of the title would appear to be recognizable from the blue lower third of the painting, which can be interpreted as depicting the sea, while the upper part, dominated by yellow, orange, and red, may be identified as a glowing sunset. Much reported and commented on by the contemporary national and international press, Et le soleil s’endormit sur l’Adriatique was not, however, painted by J-R Boronali but by, or at least in part by, the donkey of the owner of the cabaret Au Lapin Agile,54 a famous cabaret bar in Montmartre, much frequented by modern artists, among them the young Picasso. e exhibition of the painting was obviously intended as a joke, mocking the new abstract tendencies in art by apparently showing that even a donkey could produce such images as these.55 It is important to note, however, that none of the artists included in the present study had shown abstract works before 1910, the year of the Boronali coup. is means that other artists, not canonized in the art historical discourse, had already shown abstract works before that date, or that there was a general awareness of a move towards abstraction in art but without any such images going on public view as yet. I believe the former option is the likelier of the two.

If the discussions in the press can be interpreted as reflecting public opinion of the piece itself and of abstract tendencies in general, they give a good impression of the

52Hülsen-Esch 2012, p. 218.

53Société des Artistes Indépendants 1910, p. 50. is episode also inspired Russian avant-garde artist Mikhail Larionov and his fellow artists to name their artist group ‘Donkey’s Tail’ a few years later (Petrova and Schröder 2016, p. 300).

54As I was able to determine, Brionne 1910, Claude 1910, and La Tour Du Villard 1910, among others, reported on the painting’s exhibition in French newspapers. In Germany, for example, KE Schmidt 1910 reported the story in Kunstchronik: Wochenschri für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe

55Such mocking of modern art was not new at the time. Indeed, caricatures mocking abstract art have existed since the seventeenth century, as Rosenberg 2011 demonstrates (pp. 28 .). What makes the Boronali case different to these, however, is that here the intention was to fool the public by exhibiting the object as a serious work of art in the prestigious context of an established art exhibition, instead of in a humoristic newspaper or magazine.

reception with which abstraction was met around 1910. e anecdote, also known across the border in Germany, clearly shows the extent to which abstract art was ridiculed and not taken seriously, even by fellow modern artists. It is therefore all the more noteworthy that the first public presentation of abstract artworks by one of the artists selected for this study took place in the summer of 1910, just a few months a er the mockery at the Salon des Indépendants. In July 1910, Kandinsky showed the non-representational Improvisation 4, Improvisation 5 (Variation I), and Improvisation 7 at the Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler exhibition in Düsseldorf (see A1, exh. 9, p. 241). According to the collected data, this exhibition marks the first time that abstract art was presented to the public with serious intent.56 It might be due to the negative reception of abstract art in general and these three works in particular (see chapter‘Premiere for Abstraction: Kandinsky at the Sonderbund in Düsseldorf, 1910’, p. 169) that Kandinsky then chose to combine abstract and figurative works at his next exhibition in Munich, as mentioned above.

56 Again, the fact that the supposed first public display of abstract art happened a er the Boronali mockery does suggest that Kandinsky’s was not the very first showing of abstract art a er all, and that abstraction must have been somehow visible – or at least around in some form – beforehand.

Table 3: Number of catalogue entries shown by Balla per category, per year (1908–1915), in absolute numbers, and as percentage share for each year.

p. 309), all others were group exhibitions. In fact, Balla was o cially part of the Italian Futurists from April 1910 onwards, when he signed the manifesto ‘La pittura Futurista: Manifesto tecnico’.75 However, he only started exhibiting with the group a few years later, in February 1913 in Rome, when they had an exhibition in the foyer of the Teatro Costanzi. From that moment on, ‘only’ half of the exhibitions he participated in until 1915 were exhibitions of the Futurists as a group. is indicates that he relativized his allegiance to the Futurists by continuing to exhibit in other contexts, too. I argue that he did so in order not to depend too heavily on his association with the Futurists alone and to continue appealing to di erent audiences.76 Before committing to the Futurist group, however,77 Balla had already played important roles in another association, for he had been ‘a member of the acceptance committee for the 1905 Amatori e Cultori exhibition’ and was, additionally,

75Barnes Robinson 1981, p. 80.

76Barnes Robinson 1981 explains this gap by his ‘geographical separation’ from the group which was located in Milan (while Balla lived in Rome) and furthermore argues that for personal and financial reasons Balla had no rush to adopt and incorporate Futurist ideas into his work (p. 82).

77Balla joining the Futurists is treated in detail in several publications, among others in Barnes Robinson 1981 and Lista 1982.

‘also on the hanging committee’.78 In 1910, he ‘was once again on the jury’.79 Furthermore, he was ‘a member of the board of directors for the exhibition’ of the Secessione Romana, held in the spring of 1913.80 Although Balla never founded any artist groups himself, such activities as these do suggest that he was engaged and interested in being part of artist communities and their corresponding social circles, possibly also because of the exhibition opportunities they provided.

Geographically speaking, Balla had a markedly international profile, with works on view not only in six countries in Europe and the Russian Empire (Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and the Netherlands) but also in the USA and even in Argentina, where he exhibited twice. is gave him exposure in eleven cities in eight countries (see table 2): Berlin, Buenos Aires, Florence, London, Milan, Naples, Odessa, Paris, Rome, Rotterdam, and San Francisco. Interestingly, Balla exhibited just once in Paris, despite being part of the Futurist group who started their touring exhibition across Europe in Paris in 19128¹– in a series of exhibitions of which Balla, however, was not yet part. In most cities Balla’s works were presented only once. ere were just two exceptions: Rome– which is hardly surprising given that this is where he lived and worked throughout his adult life– where he featured in ten exhibitions, by far the largest number of exhibitions in any one city, and Buenos Aires, where he showed twice in the years 1908 to 1910. Rome was consequently also the city where he showed by far the highest number of works: 46 catalogue entries could be recorded for the Italian capital, whereas the next highest number is four catalogue entries in Paris and Rotterdam each, and even fewer in all other cities. Overall and despite this strong focus of his activities in Rome, in geographical terms he managed to spread his exhibition activity exceptionally wide, with presentations as far away as South America and the west coast of the United States. In San Francisco, he was invited to exhibit with the rest of the Futurist group at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition.8²

Balla’s exhibition strategy

What is immediately noticeable in Balla’s exhibition behaviour is that a large part (about half) of the pieces presented between 1908 and 1915 predate that period, with one even dating as far back as 1897. As mentioned earlier, he only started exhibiting his latest or most contemporary works in 1910. As he himself explained when talking about possibly joining the first Futurist touring exhibition, which started in 1912 in Paris at the Bernheim Jeune gallery, he felt his art still needed to mature a little before exposing it alongside the other, in his opinion, more advanced works by his fellow Futurists. Although his name

78Barnes Robinson 1981, p. 44.

79Ibid., p. 68.

80Ibid., p. 107.

81Weissweiler 2009 dedicated her book to this Futurist touring exhibition (see note 68 above).

82See Schneede 1994, p. 205.

Introduction

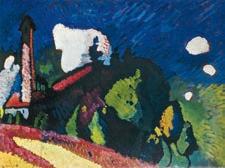

Kandinsky himself declared his first abstract oil painting to be Bild mit Kreis, painted in 1911.³65 For Bild mit Kreis, the catalogue raisonné lists the exhibition e Year 1915 in Moscow (April 1915) as its first public appearance. Meanwhile, Untitled from 1913 is widely acknowledged as Kandinsky’s first abstract watercolour.³66 e catalogue raisonné of watercolours states that it was first exhibited in Amsterdam in 1947, several decades a er its creation.³67 is would appear to suggest that the first time an abstract work by Kandinsky went on view at exhibition, and was thus seen by a larger public, was the spring of 1915 in Moscow.

However, the data collected for this study and the subsequent coding (see Appendix A4, p. 323 for details on the coding process) paint quite a di erent picture. According to the expert coding, at least two pieces in fact preceded Bild mit Kreis and Untitled as ‘non-representational’ images, not only in terms of date of production but also in terms of public presentation: Improvisation 4 (1909) and Improvisation 7 (1910) (see A1, exh. 9, p. 241). Both Improvisations were coded as ‘non-representational’ and, as the catalogue raisonné states, both were first exhibited together at the exhibition of the Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler in Düsseldorf from 16 July to 9 October 1910.³68 In the context

365 See Roethel and Benjamin 1982, no. 405. As the artist specified in ‘Selbstcharakteristik’ from 1919: ‘1911 malt er sein erstes abstraktes Bild’ (Kandinsky 1980c, p. 60). Rosenberg 2007, pp. 314–315, critically discusses Kandinsky’s claim.

366See Endicott Barnett 1992, no. 365. e catalogue raisonné itself notes that ‘[…] although this work is wellknown as “the first abstract watercolour”, there is no evidence that either Kandinsky or Münter called it by this name’, Endicott Barnett 1992, p. 327.

367Endicott Barnett 1992, p. 327.

368 e 1910 exhibition Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler has so far been given little attention in art-historical research in general and in scholarship on modern art in particular. While several publications are dedicated to its exhibition of 1912 (the most extensive probably being Schaefer 2012), they do not cover the 1910 edition at all. Nevertheless, the following publications deserve mention. Moeller 1984b is dedicated to the early history of the association, including detailed biographical accounts of the persons involved in its founding as well as a presentation of the precursor to the Sonderbund. Moeller gives important information regarding Düsseldorf’s historical context, with a specific focus on its artistic traditions, by presenting other modern artist associations from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and exhibitions that the city had hosted in the years between 1902 and 1909. Although providing some detail on the first exhibition of the Sonderbund from 1909, Moeller only briefly announces the following ones, including the 1910 edition, in the outlook of the book. Peters, Schepers, and Wiese 1984 give insight into Düsseldorf’s development into a Modernist city. ey compile several articles about the status of the arts in Düsseldorf between 1900 and 1914 and the figures active in the local scene. e compiled articles include Hülsewig’s close look (Hülsewig 1984) at the gallery landscape in the city at the time, of which Alfred Flechtheim was part, and Moeller’s account of the history of the Sonderbund (Moeller 1984a). Here, she summaries its 1910 exhibition

Première for Abstraction: Kandinsky at the Sonderbund in Düsseldorf, 1910

of this study (specifically among the selected artists and within the time-frame studied), these two works can thus be identified as the very first ‘non-representational’ works shown in public.

In the early twentieth century, a group of artists and art enthusiasts tried to re-position Düsseldorf and the Rhineland in general as the cultural hub in western Germany. Founded in 1909, the art association Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler mounted exhibitions of international modern art with the goal of confronting local audiences with the latest developments in art and the questions they posed. In doing so, it rendered them comprehensible to the public.³69 Indeed, the catalogue of the association’s 1910 exhibition explicitly declares that, given its cultural and geographic proximity to the cultural traditions of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, ‘der Rheinische Westen […] vorzugsweise berufen ist, die Provinz der malerischen Kunst in Deutschland zu sein.’³70 is goal justified supporting the newest trends in art and, by extension, the presentation of those trends in exhibitions, as was also the case in the summer and fall of 1910. e Sonderbund counted among its members not only artists but also collectors and art enthusiasts from various fields of activity, such as lawyers, dealers, and museum directors.³7¹ is in turn facilitated the organization, funding, and discussion of exhibitions. Furthermore, many of the members themselves had su cient funds at their disposal to buy the exhibited artworks for private and public collections. Membership to the Sonderbund was upon invitation only and limited to 100 regular members and 300 associate members (‘außerordentliche Mitglieder’). e person responsible for acquiring new members was Alfred Flechtheim, a then very young gallerist in Düsseldorf and fervent supporter of the avant-garde.³7² Flechtheim was well connected, among others to two gallerists in Munich, Heinrich annhauser and Franz Josef Brakl. ese in turn had connections with Kandinsky, ever since he had organized the Neue Künstlervereinigung München’s (NKVM) Ausstellung I,Turnus 1909/10 at annhauser’s Moderne Galerie in

by focusing on the inclusion of French artists and the first presentation of Cubism to the Düsseldorf public, without, however, mentioning Kandinsky’s contributions. Meanwhile, the second volume of Aust 1984 is in large part dedicated to collections and exhibitions in Düsseldorf between 1900 and 1914. However, the Sonderbund exhibition of 1910 is not given any attention whatsoever. Although the authors mentioned above have studied the context and prehistory of the exhibition and organizing body, the 1910 exhibition itself and particularly the first presentation of abstract artworks by Kandinsky are addressed in a very unsatisfying manner, if at all. e exhibition catalogue (Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler 1910) is therefore the primary souce that informs this chapter.

369Moeller 1984b, p. 149.

370Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler 1910, p. 15.

371 As listed in the exhibition catalogue, the members of the Sonderbund’s board and of its exhibition committee included museum directors, gallerists, dealers, lawyers, authors, editors, teachers, and conservators (Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler 1910, p. 54).

372Dascher 2013, p. 52.

Kandinsky Continues: The NKVM’s Ausstellung II, Turnus 1910/11 in Munich, 1910

makes clear the associations’ intention to explain its objectives as thoroughly as possible. As Lüttichau 1992 already observed,4¹7 the choice of authors reflects the international orientation of the entire exhibition, by including French and Russian artists as well as a text by Kandinsky, then living in Munich. e texts themselves express a pan-European unity in art as well as their authors’ (and by extension their nations’) common practices, heritage, and goals regarding contemporary art, thus rendering them as universal as possible. e authors all share a view of the importance of combining external observation with inner experiences and sensations in their art. I would further argue that through its geographic position as the midpoint between France/the West and Russia/the East, and by having Kandinsky’s text sandwiched between the other four, the organizers were keen to stress that Munich– and by extension the NKVM and Kandinsky himself– occupied the very centre of avant-garde endeavours in art.

Ausstellung II, Turnus 1910/11: content and abstraction in Munich in 1910

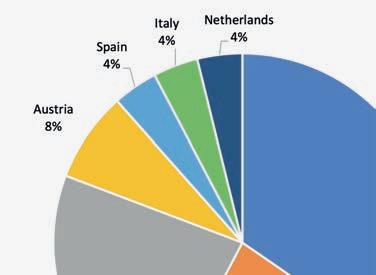

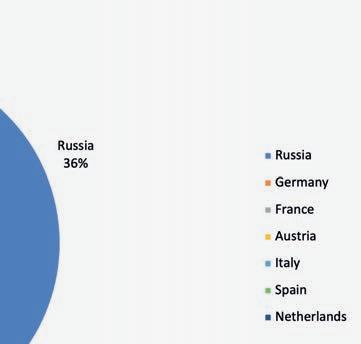

e NKVM’s Ausstellung II,Turnus 1910/11 included 132 artworks by 29 artists, most of whom were living in Paris or Munich at the time.4¹8 According to the catalogue, the show included painters from seven countries: Austria (including Czech artists), France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire (including Ukrainian artists), and Spain.4¹9 is reflects the internationality already represented by the authors of the numerous prefaces in the catalogue. is internationality is highlighted in the catalogue by listing the city of residence a er each artist’s name. Statistically, the majority of the artists are Russian, making up 34 percent of the participants (see fig. 42). German and French artists comprise 23 percent each– or about a quarter– of the exhibition. All other nationalities participate with just one artist, equivalent to 4 percent each. is means that Kandinsky and his compatriots form the largest group of exhibitors at annhauser’s gallery.

Looking at the distribution from the point of view of catalogue entries (fig. 43), the majority, or 36 percent, of the paintings are unsurprisingly also by Russian painters, followed by 25 percent by German and 16 percent by French painters. Each of the other nationalities represents no more than 13 percent of the paintings on view. Kandinsky thus belongs to the nationality submitting the most works. e reasons for this demographic in all likelihood lie in Kandinsky’s German and Russian networks, combined with Girieud’s e orts to get artists from Paris to commit to the show.

417 ‘Mit den einleitenden Texten im Ausstellungskatalog von Le Fauconnier, den Brüdern Burljuk, Odilon Redon und ihm selbst hatte Kandinsky seine programmatische Orientierung nach Frankreich und nach Rußland gleichermaßen festgelegt und die von ihm immer wieder postulierte Synthese aller Künste untermauert’, Lüttichau 1992, pp. 300–301.

418Neue Künstlervereinigung München 1910, pp. 12–36.

419Given the political map of Europe in 1910, countries that formed part of the Russian Empire at the time are counted as Russian (for example, Ukraine and Belarus). Similarly, the modern-day Czech Republic then fell under the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Ausstellung II, Turnus 1910/11: content and abstraction in Munich in 1910

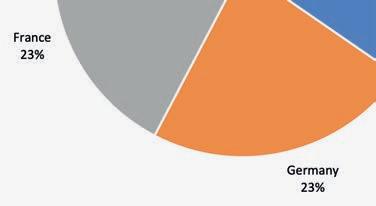

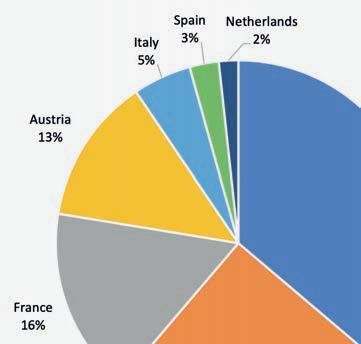

Figure 42: Distribution of nationalities of artists participating at NKVM’s II. Ausstellung, Turnus 1910/11, at Moderne Galerie, Munich, September 1910.

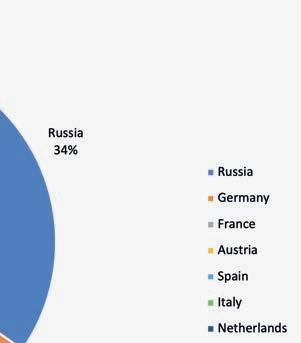

Figure 43: Distribution of catalogue entries by nationality of artist at NKVM’s II. Ausstellung, Turnus 1910/11, at Moderne Galerie, Munich, September 1910.

17–31 Mar 1909, Paris, Galeries Georges Petit

Picabia, Pêcheurs à la ligne, 1904, no. 122, naturalistic

Picabia, Bords du Loing à SaintMammès, e et d’automne, 1908, no. 351, naturalistic

Picabia, Bords du Loing, Seine et Marne, e et de soleil, 1908, no. 354, naturalistic

Picabia, L’église de Montigny, e et de soleil, 1908, no. 357, naturalistic

Picabia, E et d’automne au bord du Loing, Saint-Mammès, 1905, no. 172, naturalistic

Picabia, Soleil de novembre, e et d’automne, 1908, no. 352, naturalistic

Picabia, L’église de Montigny, e et d’automne, 1908, no. 355, naturalistic

Picabia, Le canal de Moret, e et d’automne, 1908, no. 358, naturalistic

Picabia, Bords du Loing à Moret, e et de soleil, 1908, no. 349, naturalistic

Picabia, E et d’automne, soleil du matin, 1908, no. 353, naturalistic

Picabia, Soleil du matin au bord du Loing, 1908, no. 356, naturalistic

Picabia, Bords du Loing à Montigny, e et d’automne, 1908, no. 359, naturalistic

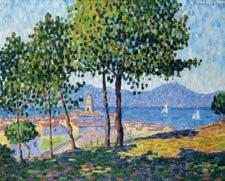

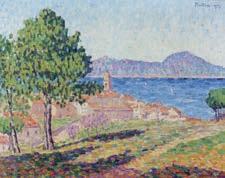

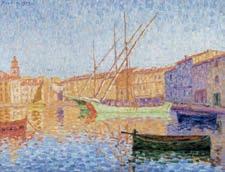

3. Exposition de tableaux par F. Picabia

Picabia, La femme aux mimosas, Saint-Tropez, 1908, no. 360, stylized – partially

Picabia, Les oranges, 1909, no. 367, stylized – partially

Picabia, Les pommes, nature morte, 1908, no. 362, stylized – partially

Picabia, Untitled, 1909, no. 368, naturalistic

Picabia, Nature morte, 1909, no. 371, naturalistic Picabia, La Pointe du port, e et de soleil, Saint-Tropez, 1909, no. 372, naturalistic

Saint-Tropez, e et de soleil, 1909, no. 374, naturalistic

Picabia, Untitled, 1909, no. 364, naturalistic

Picabia, Untitled, 1909, no. 370, stylized – partially

Picabia, Le port de Saint-Tropez, e et de soleil, 1909, no. 373, stylized – partially

Picabia, Le port de Saint-Tropez, temps gris, 1909, no. 377, uncoded

1 Oct–8 Nov 1909, Paris, Grand Palais des Champs Elysées

Balla, Il mendicante, 1902, no. 125, naturalistic

Balla, La pazza, 1905, no. 122, naturalistic

Balla, I malati, 1903, no. 123, naturalistic

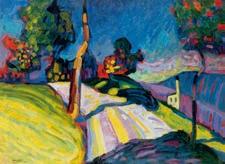

Kandinsky, Murnau – Strasse mit Frauen, 1908, no. 207, stylized – partially

Balla, Il contadino, 1903, no. 124, naturalistic

Kandinsky, Murnau –Kohlgruberstrasse, 1908, no. 252, stylized – wholly

1–15 Dec 1909, Munich, Moderne Galerie (Heinrich Thannhauser)

Kandinsky, Murnau – Strasse mit Frauen, 1908, no. 207, stylized – partially

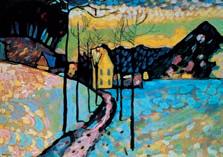

Kandinsky, Winterlandschaft I, 1909, no. 262, stylized – partially

Kandinsky, Skizze (Reiter), 1909, no. 280, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Murnau – Landschaft mit Turm, 1908, no. 220, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Reifröcke, 1909, no. 263, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Riegsee – Dorfkirche, 1908, no. 225, stylized – partially

Kandinsky, Bild mit Kahn, 1909, no. 268, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Die Hügel, 1909, no. 573, no visual evidence

28. Der Sturm. Kandinsky Kollektiv-Ausstellung. 1902–1912. Siebente Ausstellung

Kandinsky, Komposition I, 1910, no. 327, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Komposition II, 1910, no. 334, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Landschaft mit Bewegten Bergen, 1910, no. 342, stylized – partially

Kandinsky, Improvisation 13, 1910, no. 355, non-representational

Kandinsky, Improvisation 5 – Variation II, 1910, no. 331, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 10,1910, no. 337, non-representational

Kandinsky, Landschaft mit Fabrikschornstein, 1910, no. 343, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Komposition III,1910, no. 359, uncoded

Kandinsky, Improvisation 7,1910, no. 333, non-representational

Kandinsky, Improvisation 11,1910, no. 338, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Herbstlandschaft mit Baum, 1910, no. 350, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 16,1910, no. 360, uncoded

28. Der Sturm. Kandinsky Kollektiv-Ausstellung. 1902–1912. Siebente Ausstellung

Kandinsky, Lyrisches, 1911, no. 377, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, St Georg II,1911, no. 382, non-representational

Kandinsky, Impression V (Park),1911, no. 397, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 25 (Garten der Liebe I), 1912, no. 428, non-representational

Kandinsky, Winter II, 1911, no. 380, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Araber III (Mit Krug), 1911, no. 388, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Studie für Landschaft mit zwei Pappeln, 1911, no. 403, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 26 (Rudern), 1912, no. 429, non-representational

Kandinsky, Herbstlandschaft, 1911, no. 381, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 20, 1911, no. 394, stylized – wholly

Kandinsky, Improvisation 24 (Troika II), 1912, no. 427, non-representational

Kandinsky, Schwarzer Fleck I,1912, no. 435, non-representational