Facial Reconstructive Surgery in humanitarian missions

Cover: Self portrait by a patient

The original text, wrote in english by the autors, wasn’t correct or review.

The author thanks Riccardo Braglia for the precious consults and comments for this book and Helsinn for the valuable sponsorship for the realization of this important scientific activity. The author also appreciate the common interest of the Foundation New Flower in Africa for supporting the population of these countries.

The author thanks Mr Gerard Depardieu for his unwavering support

Drawings by Elisabetta Rosales

Photographs by Nicolás Bruant

Graphic design and composition: Giulio Castellazzo - WellComm

Mission support: Renata Babini Cattaneo - Fondazione Uriele

In the early 1990s, my husband Alfredo Cuomo and I met the young Dr Daniel Cataldo in Paris. We were introduced by mutual friends and were impressed by his energy, enthusiasm, and rising reputation as a reconstructive surgery expert. Through Daniel, we later met renowned medical surgeon Professor Jean Marie Servant and learnt more about their combined work at the University of Paris' Saint Louis Hospital. In 1996 they had formed ‘Operation Servant’, a humanitarian mission to work with the National Niamey Hospital in Niger to perform life changing facial reconstructive surgery on infants, children and adults afflicted with Noma disease, birth defects, cancer and severe facial burns. The missions were organized by the Saint Louis Hospital and Medicin du Monde. These transformative lifechanging actions moved both my husband and myself so deeply that we decided to act as private benefactors and financed and raised additional funds to support Operation Servant in its early initial actions. We travelled to Niger over several years and witnessed first-hand the remarkable transformations made possible by the committed ‘Operation Servant’ team.

Alfredo and I founded the Cuomo Foundation in 2001, with the primary goal of assisting the underprivileged in gaining access to education and securing brighter futures.

From the early days of support for ‘Operation Servant’ our professional paths have grown in different directions yet the core objective of providing tools to create confidence, pride and a sense of belonging remain the same.

I was invited to write this additional foreword in memory of Professor Jean Marie Servant and my late husband Alfredo Cuomo. The Cuomo Foundation has agreed to fully support the printing and global distribution of this special edition to selected medical centres and professionals in honour of both of these outstanding men.

Although the Cuomo Foundation is not responsible or able to endorse the medical assertions contained in this book, we support emotionally the aims of Dr Daniel Cataldo and his desire to teach and share his formidable knowledge and experience with the next generation of specialists in this vital field of medicine.

Maria Elena Cuomo

President of Cuomo Foundation

March, 2022 - MONACO

Is essencial that a plastic surgeon has a full training in general surgery including the knowledge of the chest and vascular surgery to become a true surgeon able to cope with challenging situation and to resolve complications

To:

My mother: Maria Laura Aguero;

The memories of my father and grandfather: Carmelo Cataldo and Natale Cataldo;

The memories of Silvia Onofri and Jacqueline Dufour.

Daniel Cataldo

Surgeon College of Medecine Hopital Saint Louis Paris

Surgeon Operation Servant Paris

Surgeon General and Plastic surgery university of Buenos Aires

Daniel Marchac assistant Hôpital Enfants Malades Paris

Surgeon Maxillo-facial Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière Paris

Surgeon Nation Heart Hospital London

Surgeon Favaloro foundation Buenos Aires

Jean Marie Servant

Surgeon of Paris Hospitals

Professor of Paris University

Head of Plastic Surgery Hospital Saint Louis University of Paris

President of the National Commision for Qualification in plasic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery

Professor, Tokyo University

Dr Jean Philippe Binder Certificates

-French National Board of Medical Doctor -French Board of General Surgery -French Board of Plastic Surgery -Chief Resident Plastic Surgeon, departement of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Prof. J. M. Servant, at the Saint Louis Hospital, Paris -Plastic reconstructive and aesthetic surgery Saint Louis Hospital, Paris - France. Professor Marc Revol

Dr Maria Goffredi

-Professor of Embryology and Histology, University of Milan -Research at the Human Morphology Sacco Hospital, Univerity of Milan -Author of Computerized morphometry in liver cirrhosis Author of Microscopic and ultrastructural morphology Author of Microscopic Histology and Anatomy -Italian Board of Anathomy an Histology -Italian College of Histology and Embriology

Dr. Mercedes Portas

-Head of Surgical Department, Burns Hospital of Buenos Aires -Head of the Radiopathology Committee -Active member of the Argentina Radiation Protection Society -Active member of the Argentine Association of Trauma -Authority in the specialty of radiation-induced burns for Latin America

Institut du Fer à Moulin Université Pierre et Marie Curie.

Ralph Diaper and Sophie Huber. Technical assistance.

Aknowledgements

• Médecins du Monde - François Fousadier: without their work in organising humanitarian missions, the operations could not be performed;

• all the anaesthetists, Gabriela Vilain, Jérôme Landru, Christian Troje, Suzanne Reysz, photograph Gérard Mateo and secretary Monique Nadal from Saint Louis Hospital Paris;

• Abdoul Toure, chief of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Niamey National Hospital Niger and Issa Hamady;

• Rabi Tahirou, head nurses Zinder National Hospital Niger; Robert Roux and Dominique Comandou heads nurses Saint Louis Hospital in Paris.

• Sentinelles for their professionalism essential for the development of the mission. Manon Louanne Chatelan;

• Professeur Jean Paul Monteil, Catherine Martinaud, Sylvain Harbon, Alain Danino, from the Saint Louis hospital Paris and Satoshi Yoza from the University of Tokyo, for their collaboration;

• Loretta Forelli, President of the Industrial Association of Brescia and Red Cross for her support of the mission for many years.

Niamey National Hospital - Niger

This book is dedicated to:

Daniel Marchac: one of the foremost surgeons in France and former staff of Saint Louis Hospital, who taught me cranio-facial and aesthetic surgery as his assistant for two years at Necker Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris.

Rene Favaloro, inventor of the coronary artery by-pass, who allowed me to perform open heart surgery, crucial for my surgical progress.

Jean Yves Neveux, who taught me his skill and technique, a major influence in my development.

Elias Hurtado Hoyo, President of the Argentine Medical Association, for giving me the attitude and approach needed to resolve complications in general surgery.

Sir Magdi Yacoub, the world’s leading heart-transplant surgeon, who gave me strength, and taught me technique and surgical tactics.

Luis de la Fuente, a recognised doctor with a world-wide reputation.

My thanks to Daniel Cataldo for offering me the opportunity to write this foreword to a book which is written on the foundations of huge experience and a long career in medicine. It was an honour to accept because I was his first teacher in general and particularly thoracic surgery. I should start by saying that after striving and showing great intellectual ability, he has gained national and international recognition. He has crossed the threshold of wisdom enabling him to engrave in these pages the ideas gained as a result of the combination of knife and intellect.

After graduating as a doctor, the young Daniel chose surgery as his speciality. His career has been long and particularly rich in experience. His first post was as Registrar in General Surgery at University Hospital Carlos G Durand in Buenos Aires where I guided him to thoracic surgery together with Rene Favaloro, inventor of the coronary artery bypass. Under our support he worked in some of the most prestigious hospitals in Europe under the direction of Sir Magdy Yacoub and Jean Yves Neveux. He made a stunning impression in a very specialised speciality, not just because of his surgical skills but also because of his humanitarian frame of mind.

He developed great skill working in delicate and narrow areas in patients at very high risk. As a very young doctor interested in learning everything about surgery, he decided to switch to plastic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery. He became the only fellow of Daniel Marchac at the prestigious hospital of Necker-Enfants Malades in Paris. Later he worked for many years at the Saint Louis Hospital at the University of Paris beside Professor Jean Marie Servant, learning about all techniques of reconstruction. The experience gained with a large number of patients with complicated problems led him to develop high ethical and moral values to operate on the poorest and weakest patients.

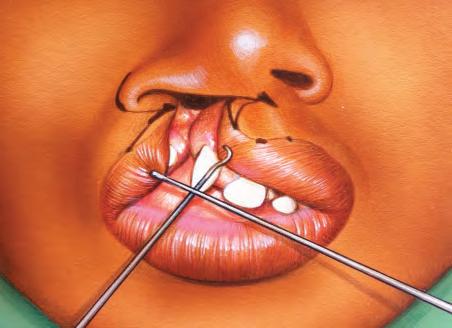

The title of this book, Facial Reconstruction, is the perfect definition of a concentration of ideas about this subject, providing a description of each tool available, and giving the author’s personal position after years of rigorous hard work. The ideas develop giving a clear message to the reader, professional of the speciality or not, culminating in the importance of the ability to make decisions quickly. To reach a satisfactory level of knowledge it is essential to read the chapters on specific techniques. Those described were developed for congenital diseases like hare lip as well as for the gangrene of the face known as cancrum oris, or Noma, at the Saint Louis Hospital with surgeons such as Prof Jean Marie Servant.

The specialist surgeon must be able to give clear answers to challenges presented by the individual patient at the time of consultation. The way in which the selection of patients is made at the first consultation is evidence of the ethos of the organisation, and is the result of experience and much careful thought.

Surgical interventions on the face are performed in order to improve functionality and anatomy, together with an aesthetically pleasing outcome. Achieving these outcomes requires adapting techniques and tactics to each individual patient. The procedure has enormous consequences for the patient – on personal and social levels, and for employment opportunities. The symmetry of the exterior appearance is fundamental to the judgement of health, beauty or normality in human relationships. Improvements to the appearance mean an improvement in quality of life even in countries where scars have a different value to those of occidental regions. Many of these ideas are set out in the chapter on Psychology – an unusual inclusion in a book about surgery, but one which imparts a high quality to these pages. The plastic surgeon is much more exposed than other surgical specialists to the judgement of the public. He must live with the difference between the result wanted and the result actually obtained. The book is written with the intention to be instructive, but also to be easy to read and to understand. The photographs and drawings facilitate these aims. The bibliography at the end allows amplification of the information given. All things considered, this will remain a consultative book.

Professor Dr Elias Hurtado Hoyo Consultant Professor at the University of Buenos Aires; Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Moron and foundation Barceló; Consultant Professor, Military Hospital of Buenos Aires; Member of the Argentinian Academy of Surgery; Member of the Scientific Medical Association of Córdoba; Member of the Medical Academy of Paris Member of the National Medical Association of Argentina and Paraguay on Medical Ethics; President of the Argentine Medical Association.

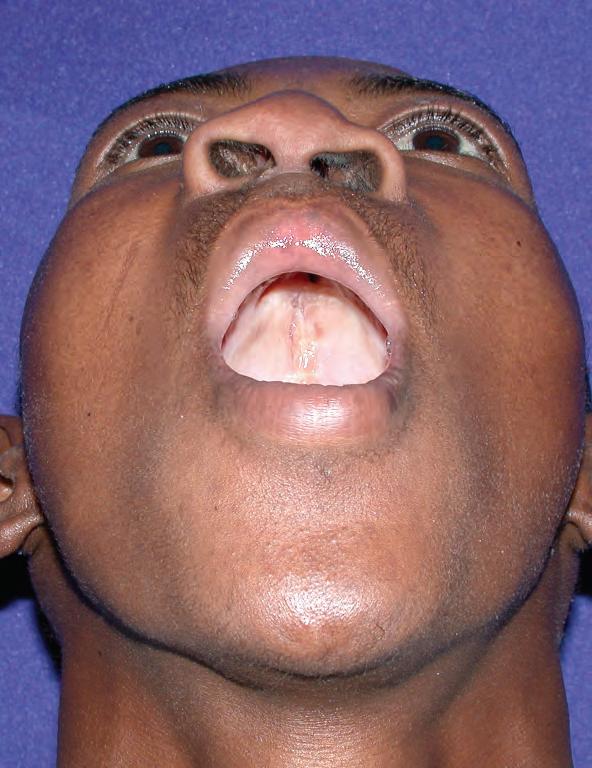

Noma Cancrum oris

Child (one of 11 siblings)

Noma (cancrum oris, derived from the Greek nomein, “to devour”) is an opportunistic disease associated with malnutrition, poverty and/or lack of hygiene. In most cases the causal pathogens are Fusobacterium necrophorum and Prevoltella intermedia. The disease mostly affects children under the age of six (95 - 98% of cases). Those with poor buccal hygiene and severe malnutrition, especially with protein and vitamin A deficiency, are at high risk. The different disease each have their own periodicity: most cases of Cancrum oris occur in the dry season, which results in months of famine.

Unfortunately, malnutrition is often associated with malaria, measles, chicken pox, rubella, scarlet fever, herpes, typhoid and tuberculosis further increasing the risk of Noma infection. Taking all these factors into consideration, it can be seen that Noma (especially in children) is a disease of extreme poverty.

In adults, the incidence is low (less than 5% of cases), and associated with HIV infection (see Bacteria sand virus chapter), other diseases (e.g. tuberculosis, hepatitis A, B, C and E) or cytotoxic drugs used in the management of tumours (e.g. Burkitt’s lymphoma).

Cancrum oris occur in the dry season, which results in months of famine.

Malnourished child suffering from Noma

Symptoms and progression

Death occurs when the infection reaches Point 0 (the dura mater).

Noma begins as necrotising gingivitis and rapidly spreads through the mouth disrupting anatomic barriers. It involves soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity (except the tongue), para-oral structures, and the orbit. It is a serious orofacial gangrene originating intra-orally in the gingivaloral complex before spreading extra-orally, destroying other tissues. In most cases the disease is unilateral but bilateral lesions are sometimes observed. The disease demolishes soft tissues, bone and cartilage, and if not promptly treated, leads to death within two weeks in most cases. Aspiration pneumonia, sepsis or diarrhea may worsen the clinical condition. Death occurs when the infection reaches Point 0 (the dura mater) Sequelae of Noma depend on the extent of tissue disruption and include oral incontinence, trismus, speech problems and social exclusion due to facial disfigurement.

Fever, grey gums, excessive production of saliva and lymphatic node enlargement are symptoms suggestive of a Noma infection.

Early diagnosis, before the disease becomes clinically apparent, is essential in limiting the effects of the disease: fever, grey gums, excessive production of saliva and lymphatic node enlargement are symptoms suggestive of a Noma infection.

At the start of the infection the tissues become swollen, hard and hot: the mucosa become orange and the skin loses its pigmentation. Then quite quickly, a black area appears with a boundary marking the limit of the necrotic area to be eliminated. I just a few days the scar falls off without bleeding, sometimes leaving the bone exposed. The destruction of the bone is often followed by the destruction of the dental germ.

The lesion is often larger inside than out, so the mucosal damage is more important than the cutaneous. At the time of cicatrization, the destroyed mucosa become fibrotic and prone to retraction of tissue, particularly the jaw. The gangrene often spreads to the eyelid, palate, nose, ear and mastoid region.

Classic noma lesion involving molars, canines and external incisors (three superiors and one inferior)

Differential diagnostic:

• malignant infection

• Vincent disease

• Burkitt’s lymphoma

• Leishmaniasis

Historical references

Africa is the continent where most cases of disease are reported, particularly in Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal, but people in Asia and South America are not safe from the disease.

Noma was known during the time of Hippocrates, Galen, Celsus and Aretaeus of Cappadocia. The first clear description of Noma as a clinical entity appeared in 1595 in the Handboeck der Chirurgijen by Carolus Batus. In a chapter on corrosive ulceration of the mouth in children, the author underlined the rapidly progressive nature of the disease, advising practitioners on the risks of a misdiagnosis. At the beginning of the 17th Century, Noma started to appear in the European medical literature and Arnoldus Boot mentioned it in his book Observations Medicae de Affectibus Omissis (1649). In this text the Latin words cancer oris and cancrum oris were adopted for the first time. The Dutch surgeon Cornelius van der Voorde used the word “Noma” indicating a rapidly spreading gangrene of the mouth in the humid soft tissues of children in 1680. In 1848 it was described by Tourdes as a “gangrenous infection”. The word Noma was used by Lund in 1762 to describe a gangrena of the mouth in two children.

In the 18th Century several authors in Northwest Europe observed that Noma was associated with poverty, malnutrition and measles.

Classic mid-face lesion. Infection at superior canine has spread to molars and external superior incisors

During the Second World War (19391945), Noma was seen in Europe after infectious diseases, such as chickenpox, herpes, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, gastroenteritis and bronchopneumonia.

Occurrence - Europe

Noma has been present in Europe from medieval times. In the early 1900’s it was observed in the USA in a 3-year-old child with acute myeloid leukaemia, in Germany in two adults with lymphoid leukaemia and in a child with agranulocytosis. Eckstein observed 40 cases, all in children, in Ankara, Turkey, over a period of only 3 years (1936/38). Twenty-two of these cases were observed during a malaria epidemic in 1938. During the Second World War (1939 - 1945), Noma was seen in Europe after infectious diseases, such as chickenpox, herpes, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, gastroenteritis and bronchopneumonia. At the end of the war, several cases were reported in the concentration camps of Belsen and Auschwitz.

In the decades after the war, the reduction of extreme poverty and starvation, even among the poorest sections of society, resulted in a decrease in the number of cases.

More recently Noma has been described in immunocompromised adults in more developed countries, especially in patients with blood dyscrasia. Similar features have lately been described in patients with Aids.

With improvements in hygiene and nutritional status, and the decline in outbreaks of measles and other eruptive fevers, Noma disappeared from more developed countries: in the last three decades of the 20th Century the world paid little attention to Noma.

Occurrence - worldwide

Today, the disease is almost entirely confined to developing countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is one of the poorest parts of the world. In this zone, known as “The World’s Noma Belt”, millions of people are affected by hunger and the infection has an incidence as high as 140,000 cases per year, with a mortality rate of 80 - 90% and 900,000 survivors suffering disfigurement. A medicinal cure usually only becomes available in a later stage, when the sequelae of Noma are already present. Unfortunately, treatment of the infection is too expensive for developing countries so the economic support of the Western world is of paramount importance. This aid is often too late and subsequent on the dissemination by the media of pictures of undernourished children. The cornerstone of the treatment of Noma is antibiotic therapy (sulphonamides and penicillin) and the surgical treatment of the sequelae. However, these treatments remain inaccessible to the majority of patients due to their extreme poverty. In Niger, with a population of almost 15 million people, the vast majority are malnourished and poor.

The disease is confined to developing countries, particularly in SubSaharan Africa, which is one of the poorest parts of the world. In this zone, known as “The World’s Noma Belt”

Cancrum oris. Three years evolution. Infection of superior molars, canine and two incisors. Evolution on his own, without medical neither surgical toilette.

Young patient suffering cancrum oris with sequestration of the superior and inferior maxillary and zigomatic bone, following the granulation tissue and wound contracture

It is rare in adults, although we have seen it in a patient with HIV undergoing treatment for immunodepression.

Moreover, the high birth rate (7 children per mother), perpetual drought, rising food prices and the lack of land suitable for farming (only 15% of the country) further worsen the people’s condition, facilitating the spread of Noma.

In fact the highest incidence of the infection is during times of famine, while the lowest incidence is after the harvest.

Most of the patients in Niger come from the desert areas, and many of these from a town called Zinder (800km east of the capital Niamey). In Nigeria, the majority are from rural areas around Sokoto.

At least 70% of cases are children of farmers. It is difficult to obtain reliable statistics but in some areas of northwest Nigeria it occurs in 6.4 of 1000 children and up to 12 per 1000 in the worst affected communities. In Niger the occurrence is between 8 and 10 per 1000.

Some research shows that the maximum incidences of the disease occurs between the ages of 2 and 5 years, when children are weaned. It is rare in adults, although we have seen it in a patient with HIV undergoing treatment for immuno-depression (see Bacteria and virus chapter).

Lack of access to hospitals remains one of the main problems: because Noma often occurs in remote and marginalized communities, death may occur before medical care can be accessed.

It is clear that the most effective approach to Noma remains prevention. Fighting extreme poverty with measures leading to economic progress would eradicate Noma completely. Failing prevention, a prompt recognition of the disease allows to treat the gangrene aggressively, avoiding disfigurement.

In conclusion, the most likely chance of survival for patients affected by Noma in Africa is support from doctors in developed Western countries. Therefore, surgical treatment in such patients is more than a mere medical approach and provides an alternative to patients lacking a future. The doctors’ efforts are completely repaid by the immense gratitude shown by the patients.

Epidemiology

Although Noma has been known for at least seven centuries, only in 1994 was it designated as a priority, we started studying it extensively in the 1980’s. The social impact of the disease is undeniable, given the high mortality rate in children and the low chance of social integration for survivors.

The countries most affected by the disease are those of the Sahel region, one of the poorest in the world - such as Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso and Senegal. There is a huge difference between rural and urban areas. Outside Africa, Noma is described in a few children living in Latin America, India and China.

The mortality is around 80% in 15 days, due to infectious complications like pneumonia, diarrhea and septicemia. When the scar falls, the general conditions improve.

Antibiotics therapies produce a fall in mortality in patients under treatment to about 10%. Also hyper-protein and multivitamin nutrition, local hygiene, transfusion (rare) are very importantly in order to lower mortality rate.

The mortality is around 80% in 15 days, due to infectious complications like pneumonia, diarrhea and septicemia.

Cancrum oris. 3rd week post infection.

Noma. Malnourished eight years old boy, thirty five days post infection.

In the acute phase of the disease, family and medical personnel are often unable to give a diagnosis.

Cancrum oris is easily misdiagnosed as Burkitt’s lymphoma, leishmaniasis and Vincent’s angina, among other malignant and infectious diseases. Malnourished children in poor socio-economic conditions are susceptible to a variety of pathologies and Cancrum oris often develops after herpes, malaria and chickenpox infections

In some villages the patients are hidden because the disease is considered to be “evil” or “from hell”.

The true incidence and mortality rate of Noma are unknown for the following reasons:

• Noma wasn’t registered as a disease before 1992, and no cases were officially reported by the governments of the less developed countries before 1994;

• As many cases occur in desert and remote rural areas, the mortality rate is underestimated, although it is believed to be as high as 90%;

• Most of the affected children live in small villages or in nomad families with little contact with outsiders, therefore it is hard to register the mor tality and eventual outcome;

• In African countries certain diseases like Noma are considered shameful and affected children are hidden in gloomy rooms or even with animals.

Just 10% of patients seek medical care in an early stage, even though we make as much effort as we can to facilitate communication - informing, giving telephone numbers and providing ambulances to collect patients.

Symptoms

Cancrum oris starts with an exanthematous fever or debilitating disease with the following symptoms;

• soreness of the mouth;

• tender facial swelling;

• excessive salivation;

• painful lip or cheek;

• a foul-smelling purulent secretion, a bluish-black discoloration of the skin in the affected area, and a characteristic putrid odour are usually early signs.

The mortality rate in the first years of this century was 95% for the African countries where treatment was not available. On the other hand, in countries in which penicillin, sulphonamide and ascorbic acid are routinely used (without forgetting better health conditions than in Africa) the mortality rate (%) decreases to:

• 48% in Afghanistan;

• 25% in Madagascar;

• 12% in Vietnam;

• 8% in Turkey;

• 6% in the Philippines.

Protein-energy malnutrition is related to atrophy of the lymphoid tissues in the T-dependent areas of the thymus, spleen, Waldeyer’s ring and lymph nodes. The number of all lymphocytes and of CD4 and CD5 T-cells drops, impairing the production of immunoglobulins. In fact antibody production requires the presence of antigen-presenting T-lymphocytes. This condition, especially in malnourished children, leads to a state of inflammation of gingival and periodontal tissue, increasing the susceptibility to gingivitis and Noma.

A study of 100 Nigerian children at risk of Noma found low plasma concentrations of zinc, retinol and essential amino acids, and an increased concentration of cortisol due to adrenal hyper-function. The concentration of this hormone in malnourished children is double that of those that are well-nourished.

In malnourished children, leads to a state of inflammation of gingival and periodontal tissue, increasing the susceptibility to gingivitis and Noma.

Tooth hygiene practice.

In Niger just 2% of children brush their teeth.

Cancrum oris.

Seven years old boy, infection at superior and inferior incisors and superior canine teeth.

The disease of the child whose brother will come soon.

Other characteristics of starvation are the presence of important anaerobic flora, in particular of Gram-negative rods. 88% of undernourished children had spirochaetes which were not found in well-nourished children.

African children are breastfed for a long time (1 to 2 years), then weaned abruptly, and the lack of a proper substitutive diet leads to a deficiency of vitamins, immunoglobulins, amino acids and minerals. This in turn makes them susceptible to malaria, measles, herpes, chickenpox, AIDS, hepatitis and Noma. This sudden cessation of breast feeding and subsequent weakness in Africa is called “the disease of the child whose brother will come soon.”

The reticulate endothelial system characterizing chronic malaria causes the lowering of immunity that could pave the way to Noma.

There is some discussion about whether the most important risk factor for Noma is infection rather than malnutrition: in fact, there are children in the early stages who are not malnourished. Probably malnutrition is a predisposing factor. The effects of malnutrition on the immune system are well known. For example, lack of iron is associated with anaemia, reduced neutrophils and lymphocyte activity, and decreased response to certain antigens, such as those of the herpes simplex virus. Zinc deficiency leads to atrophy of lymphoid tissues, diminution of cell-mediated immunity and phagocytosis, and tissue-repair processes.

Lack of hygiene is another important factor in the development of Noma. There are studies showing just 2% of children in Niger use a tootbrush to clean their teeth, and those are exclusively in urban centres. In the rural and desert areas, they normally use their fingers or chew sticks. None of the children operated on for Noma brushed their teeth.

Other diseases associated with Noma are malaria and measles. The reticulate endothelial system characterizing chronic malaria causes the lowering of immunity that could pave the way to Noma.

Measles was considered by some authors (e.g. Tempest) to be the most important debilitating disease preceding Noma.

In Niger just 25% of children are vaccinated. Children with measles have lower than normal energy intake and show low mobilization of hepatic vitamin A.

In poor countries this disease can rapidly turn moderate under-nutrition into a fatal condition in the majority of patients. Most of the children present ulcerative lesions of the oral mucosa which can be so impressive that they have been termed “Noma-like post-measles ulceration.”

Other infective diseases can be debilitating and can facilitate the progression of buccal lesions into Noma, such as chickenpox, diphtheria, typhus, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, AIDS, leishmaniasis, agranulocytic angina, malignant oral lesions and some manifestations of syphilis. The leishmaniases are caused by several species belonging to the genus Leishmania, a flagellate protozoan transmitted by the bite of the female phlebotomine sandfly. Extensive destruction of mucosal membranes of the nose, mouth and throat can occur in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. The physiopathology of these necroses with their sharp boundaries are ischemic features with localized arterial thrombosis or capillary micro-thromboses which are probably secondary to infection.

First line treatments are - high protein diet, rehydration, administration of vitamins (particularly vitamin A), and antibiotic therapies with amoxicillin and metronidazole.

These are broad spectrum agents active against periodontal and oropharyngeal flora, used to limit the tissue destruction and to induce satisfactory wound healing. Surgery at this stage is contra-indicated but necrotic regions of the face should be cleaned (soft tissue and bony sequestration) and any loose teeth extracted. All areas of necrosis are completely excised using tepid water, under local anaesthesia if necessary.

Tempest found 4 cases without buccal lesions, but with lesions of the scalp (mastoid area), neck, thorax and extremities.

Noma lesion at 3 and 6 months showing healing after regular toilettes

Infective diseases can be debilitating and can facilitate the progression of buccal lesions into Noma.

Acute necrotising gingivitis

Acute necrotising gingivitis is one of the most significant manifestations and sometimes the first symptom of the disease. It could be generalized or localized. It begins with gingival oedema and sudden necrosis, with decapitation of the interdental papillae, rapidly followed by bleeding and pain. Pathognomonic signs like foetid odour, fever, greyish pseudomembranes and hypersialorroea are often present. Protein-energy malnutrition or vitamin deficiencies can lead to an increase in permanent tissue damage and the entry of oral pathogens.

Acute necrotising gingivitis. It begins with gingival oedema and sudden necrosis, with decapitation of the interdental papillae.

Pathognomonic signs like foetid odour, fever, greyish pseudomembranes and hypersialorroea are often present.

Toilette.

Hemi face necrosis evolving posteriourly.

Ear compleat necrosis. Infection start at molars (4), canines and external incisors (2).

Little is known about the prodromic phase of Noma and its duration. The absolutely first symptoms, fever and apathy, are usually misdiagnosed as malaria by the family, and medical care is extremely rare in this stage. The first signs of Noma are oedema of the cheek and gingiva. Necrotising stomatitis may be seen at the alveolar margin spreading very quickly to the cheek mucosa in just a couple of days. In the following days, discoloured, black areas appear on the external surface of the cheek. These necrotic tissues remain defined, making a clear frame of the lesion and take a typical cone shape, described by the first clinicians who observed the disease. Necrosis often causes soft tissues and bone/cartilage to rapidly slough away, destroying the mandible, maxilla and palate, exfoliation of teeth and obvious external loss of skin.

Onset of Noma infections

In 1999, Falkler described 62 children in groups: 68% of malnourish children with ANG also had herpes infection, against 10% in malnourish children without ANG. The herpes virus favours the progression of ANG in malnourished children. For other authors, like Enwonwu, some viral infections, for example herpes or cytomegalovirus, can lower the buccal mucosal defenses and facilitate the development of ANG. On the other hand, some authors think a minor lesion of the mucosa is sufficient to initiate the disease.

Malnourish can alter the viral genotype, making it much more aggressive.

The bacterial flora in malnourish children is quite different, and perhaps an infectious agent, particularly Fusobacterium necrophorum, can start the infection. Noma starts as a gum infection at one or more teeth. The severity, extent and progress of the disease are associated with which, and how many, teeth are involved. When the infection reaches the dura mater through the frontal sinus ostium the mortality rate is almost 100%.

Involvement of different types of teeth Canines

Canines are involved in 83% of cases: in 12% of cases it is the only type of tooth involved. In massive, acute manifestations of Noma, incisors and molars are usually involved as well. Because of its position, the canine has less protection from the oral mucosa, is deeper in the bone and has more gum covering than other teeth: these features facilitate the onset of the infection.

Once the infection has started, the position of the canine, close to the maxillary sinus and the lateral wall of the nose, allows the infection to involve at least the maxillary sinus mucosa and the inferior turbinate.

When the lesion is localised at a canine, it can damage just its own root or alveolar process, or spread upwards, damaging the sub-cutaneous tissue: it is extremely difficult for the infection to reach the superior turbinate or orbit floor. On the other hand, it may advance towards the skin and spread to the base of the nostril, lateral wall of the nose, inferior turbinate, inferior maxillary sinus mucosa and even spread backwards, damaging the hard palate.

The infection often spreads in combination with incisors, in which case the damage can easily reach the base of the nose and columella.

These necrotic tissues remain defined, making a clear frame of the lesion and take a typical cone shape, described by the first clinicians who observed the disease.

Once the infection has started, the position of the canine, close to the maxillary sinus and the lateral wall of the nose, allows the infection to involve at least the maxillary sinus mucosa and the inferior turbinate.

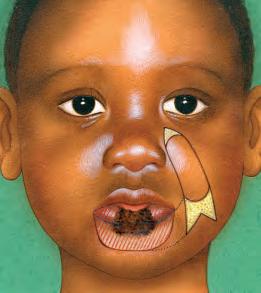

Canine ifection starting with destruction of lateral wall of the nasal pyramid and maxillary sinus.

In this patient infection spread to three incisors and molars.

This can be completely destroyed as far as the tip of the nose and the inferior inter-cartilaginous septum (see Columella chapter).

When in combination with molars, the infection can rise to the orbit floor through the posterior and superior walls of the maxillary sinus, damaging the cartilage and mucosa of the sinus, and even the temporo-mandibular articulation (extra- or intra-capsular), badly damaging it.

In patients where the infection is stronger because of the combination with incisors or molars, then Point 0 is easily reached, and the mortality is higher.

Inferior canines are less frequently involved in the disease than the superior ones, accounting for around 20% of cases, and are often associated with incisors. As the lower lip is thin, especially the cul-de-sac where the mucosa joins the chin, damage occurs right through the wall, sometimes destroying the lip completely.

Incisors.

Incisors are involved in 65% of cases, either one or two in combination with canines, less frequently with molars. Incisor only infections account for 10% of cases. The gangrene spreads upwards, damaging the base of the nose, nostril, columella (which can be completely destroyed), inferior septum, tip of the nose and often the lips. When this happens the lip is badly damaged, with important retraction of the mucosa, making reconstruction even more challenging.

Incisors: infection can damage the base of the nose, columella (can be completely destroyed) and often the lips.

When the infection starts at a canine, with the involvement of at least one or two incisors, the lower lip incurs extensive damage. Due to its thinness, infection arising from the inferior incisors can easily go all the way through it, causing severe damage to the mucosa. When a couple of incisors are involved with an inferior canine, the infection can be severe enough to lead to total destruction of the lower lip, sometimes including the chin. Reconstruction then requires the use of neck flaps and possibly free flaps: however, these are not the first choice in humanitarian missions (see Surgery of Cancrum oris chapter). In all the cases described here, the tongue is usually not affected.

Superior molar can spread to the superior wall of the maxillary sinus, the orbit, inferior eyelid and temporomandibular articulation.

Quite often, canines are also involved, in which case the infection becomes more severe. Damage is caused to the whole of the upper lip (sparing the commissure stump) and the columella, which is badly damaged as far as the tip of the nose, the inferior aspect of the maxillary sinus, often the inferior (and sometimes the medium) turbinate, and the hard palate. The infection can progress through the cheek, the internal wall of the orbit as far as the superior turbinate and the sphenoidal bone, and eventually the dura mater or Point 0. When this happens, death occurs very quickly.

Molars

Molars in isolation account for just 15% of cases. In molar-only cases, the disease can destroy the whole thickness of the cheek, sometimes without damaging the surrounding tissues, but it can reach the temporomandibular articulation (intra - or extra-capsular) harming the coronoid processes.

Molars are always involved when trismus is present. The path of the infection starting in molars, damage the posterior-superior wall of the sinus, orbit floor, 3rd turbinate, eyelid and eye causing loss of sight.

When combined with canines the incidence becomes 25%, provoking serious necrosis of the cheek. In these cases, the infection can easily reach the maxillary sinus, destroying it and destabilising the orbit floor, often leading to loss of the eye. Frequently the infection reaches the superior turbinate and Point 0.

Cancrum oris. One week post infection of inferior molars. Necrotising stomatitis started at molars.

Toilette.

Cancrum oris.

Six years old boy, infection of superior canine, two incisors and one molar. with severe damage of maxillary sinus and lateral wall of the nose. Seven weeks and two months later.

The damage caused by infection starting at different combinations of

can be summarised

Canine;

Lips

Nostril base

Lateral wall of the nose

Inferior sinus and mucosa

Anterior palate

Cheek

follows:

Noma after toilette 2 months post infection

Turbinate (inferior and medium)

Incisors;

Lip (up to 90% of its thickness)

Columella

Nostril base

Inferior septum and mucosa

Tip of the nose

Anterior palate

Lower lip: until completely destroyed

Incisors associated to a canine;

Lips leaving just a commissure stump

Destruction of the columella

Tip of the nose

Whole thickness of lateral wall of the nose

Inferior sinus almost totally

Turbinates up to the superior

Orbit, floor and lateral wall

Point 0

Molar;

• Cheek

Coronoid processes

Inferior eyelid

Maxillary sinus

Orbit floor

Turbinates

Point 0

Cancrum oris. Infection localized at first superior molar.

Molar associated to a canine;

The whole cheek

Coronoid intra-articular process

Lateral wall of the nose

Palate

Destruction of maxillary sinus

Septum

Turbinates (3)

Point 0

Observations

Even when the infection is severe enough to badly damage muscle, skin and cartilage, it does not necessarily destroy the capacity to grow a new tooth.

In some patients the lesions are purely internal – to the palate, maxilla, orbit floor, septum or sinus – with the muscle and skin remaining undamaged. In these cases the infection is rarely severe and could have started from any tooth. We divide the infection into four categories, depending on the severity:

1 localized on one or more teeth without affecting surrounding tissue; 2 limited to internal lesions of mucosa or cartilage;

3 internal and external lesions but without compromising functions (bite, containment ability of the mouth, ectropion)

4 damage to the orbit, the maxillary articulation, destruction of part of the nose or cheek, and the upper and lower lips.

The damage caused depends primarily on the extent and severity of the infection, but the direction that it takes – anterior, posterior, up or down – is also important. When the infection starts at inferior incisors or canines, it always progresses anteriorly, seriously damaging the inferior lip, which is thin, especially at the cul-de-sac where it meets the chin. It never travels posteriorly, as we never notice damage to the tongue or the floor of the mouth. When inferior molars are involved, the path could be towards the skin, resulting in a lesion which, in a few cases, perforated all the layers as a “localized hole” ; more frequently, it is associated with an upward spread towards the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus or the temporomandibular articulation.

An infection starting at superior incisors most frequently spreads to the base of the nose and columella: if a canine is involved it can easily reach the floor of the maxillary sinus and lateral wall of the nose. If the infection starts at a superior molar alone, it can spread to the superior wall of the maxillary sinus, the orbit, inferior eyelid and temporomandibular articulation. In a few cases it penetrates all the layers including the skin as a “localized hole” like inferior molar.

Picture of the skull showing the thinness of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus. Through which point 0 is easy reach.

Thanks to the Institute of Fer à Moulin - University Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris, for the research collaboration.

Noma symptoms

Simple gingivitis: symptoms

Gums liable to bleed easily

Hyper-salivation

Gum inflammation

Pain Anorexia

Necrotizing gingivitis: symptoms

Fever

Swollen face

Oedema of the face

Halitosis

Gum ulceration

Pain

Spontaneous gum bleeding

Hyper-salivation

Anorexia

Bony sequestration

Necrosis: symptoms

Fever

Halitosis

Scar boundary

Bony sequestration Jaw constriction

Foetid smell Pain Gum ulceration Anorexia

Necrosis: treatment

Amoxicillin

Metronidazole

Multi-vitamins

Painkillers

Rehydration

Management of other pathologies

Bandaging to avoid fall of the flap during transfer

Simple gingivitis: treatment

Clean the mouth with tepid salt water

Buccal hygiene

Follow the progress of the disease

Necrotizing gingivitis: treatment

Amoxicillin

Metronidazole

Multi-vitamins

Painkillers

Management of associated disease

Follow the progress of the disease

Rehydration and feeding (balanced diet) Hygiene (frequent cleaning) of the mouth and teeth

Bacteria and virus

Due to the necrosis and putrid odour of the wounds a bacteriological aetiology of Noma has long been postulated.

In the last fifteen years, several studies have allowed us to identify and characterise the bacteria present in Noma. Among the hundreds of species isolated, the most important are Fusobacterium necrophorum, Prevoltella intermedia, Prevoltella melaningogenica, Bacillus cereus, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Corynebacterium pyogenes. Bacteroides fragilis are associated with Noma in a lower percentage of cases.

The commonest bacterium is Fusobacterium necrophorum. This bacterium is present in some cases of foot rot of domestic animals, in the gut of herbivores as a commensal, in human and animal faecal remains and has occasionally it has been isolated from periodontal lesions. The infection usually arises from contamination of damaged mucous membrane or skin as it is unable to invade intact epithelium directly.

The bacteria are Fusobacterium necrophorum, Prevoltella intermedia, Prevoltella melaningogenica, Bacillus cereus, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Corynebacterium pyogenes.

Child in the 7th weeks. The infection has spread from 3 superior incisors, a canine and molars.

Fusobacterium necrophorum is an opportunistic pathogen that can invade oral tissues.

The microorganisms associated with necrobacillosis, especially Fusobacterium nucleatum, are opportunistic pathogens that can invade oral tissues when there is a local weakening of defences such as abrasions, debilitating conditions, or trauma related to, for example, the eruption of molar teeth. Necrobacillosis has many features in common with cancrum oris: in fact both are associated with painful skin ulcers, disabling conditions of the lower part of the body due to skin abrasions, with a higher incidence in malnourished children and where there is faecal contamination.

Infection with herpes virus could lower local immunity, increasing the susceptibility to bacterial flora and cytomegalovirus. Both viruses are frequently associated with periodontal diseases and release of several inflammatory cytokines. In particular interleukin 1B, a potent bone-resorptive cytokine, may play a pivotal role in periodontal diseases. On the other hand, herpetic oral lesions are involved in either damage to the mucosal barrier or reduced local immunity, leading to the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and the development of Noma in an undernourished child.

All patients we treated contracted the disease at young age (between 2 and 7 years old), cancrum oris is not frequent in teenager and is exceptional in adulthood, but could be possible in HIV patients under immunodepression treatment (see patient below).

Noma in adult is exceptional. Patient with HIV under immunodepression treatment.

Management

The coexistence of malnutrition, small lesions of the gum due to malaria or chickenpox, along with a debilitated immune system allows Noma to invade the mouths of undernourished children leading to death in as many as 90% of patients in a few weeks. Among those who survive the gangrene, the formation of granulation tissue anticipates a period of re-epithelialisation and wound contracture.

However, symptoms like gum inflammation, fever, foetid smell, bony sequestration, gum bleeding easily provoked by touch or brushing, high volume of saliva, painful gum and anorexia usually come first. The treatment of the inflammation, in this early stage, consists in cleaning the mouth with hot salt water and general hygiene, bearing in mind that the disease spreads extremely fast. Because the infection and necrotic tissues must be eliminated before reconstruction, it is necessary to wait for re-epithelialisation. This is a slow process which can take a long time – from a minimum of 6 months to more than 1 year in patients in whom the general clinical conditions are poor. Necrotic inflammation of the gum is treated with antibiotics (amoxicillin and metronidazole), multi-vitamins and analgesics. Early reports mention the use of sulphonamides, penicillin and chloramphenicol. When the gangrenous process has involved the cheek, the antibiotics significantly decrease the risk of death but cannot reverse the damage. Related to the rapidity of the spread of the infection, the first 24-hours are crucial and the treatment includes hydration, a balanced diet and careful dental hygiene. In the next stage, swelling and severe oedema of the face are added to the fever, halitosis, gum ulceration and bleeding, bony sequestration, pain and anorexia, further complicating the clinical scenario. At this time surgery is contraindicated. When necrosis and scarring around the tissues appear, the treatment is the same as in the previous step. However the patient should be properly bandaged and taken to a hospital as soon as possible, even if is not a risk of bleeding in this step of the disease. There are still no indications to for surgery at this point and the aim of the treatment is the control of sequestration.

When the gangrenous process has involved the cheek, the antibiotics significantly decrease the risk of death but cannot reverse the damage.

Cancrum oris. Five years old boy. Lack of buccal hygiene. Molars bacterial infection. Lesion spread through all layers to the skin.

Noma. eight years old girl, two month post infection Fusobacterium necrophorum and Prevoltella intermedia.

Necrosis often causes soft tissues and bone/cartilage to rapidly slough away, destroying the mandible, maxilla and palate, exfoliation of teeth and obvious external loss of skin. Nutritional rehabilitation, oral disinfection and antibiotic treatment started in an early stage can halt the disease.

Only during granulation and re-epithelialisation there be an indication of a skin graft to accelerate healing, but very few surgeons would recommend it as a routine procedure. Noma is a life-threating disease, therefore it is crucial to keep the patient alive with antibiotic therapy and proper nutrition preparing them for reconstructive surgery. The triad of nutritional rehabilitation, oral disinfection and antibiotic treatment started in an early stage can halt the disease. Unfortunately very few patients have access to appropriate medical care in this phase, and generally it is difficult to follow them until the resolution of the clinical picture. Even if they are followed up for a long period, rehabilitation remains a major problem in countries where there are no trained doctors or infrastructure. In fact, functional problems require a long period of specialist care, especially when trismus occurs (see Trismus chapter). Other conditions like incontinentia oris may require a second operation, and there could be speech difficulties to deal with.

Attainment of the desired results takes a long time, patience and the correct programme. The social stratum from which Noma patients come contributes to making follow-up harder. In many cases, patients are unable to understand the risks and complications of surgery. The aim of surgery is always to improve functionality and aesthetically.

Surgeons must be aware that the tissue loss could be much more extensive than initially assessed because the wound has healed by contraction. In order to release contracture, correct the defect and open the mouth.

In future the goal of the surgeon must be to close the hole in the face as quickly and as simply as possible, avoiding complications and giving more attention to functional problems like trismus, rather than just the aesthetic side of the disease. However, the patients are much more interested in the aesthetic results than the functional recovery, due to the need to be accepted by a tribal society. Taking into account the previous considerations, the duty of the surgeons is to balance aesthetic results with functional improvements.

Post-operative functional rehabilitation is the cornerstone of the clinical recovery although in some cases it can be really challenging. For example, trismus has to be treated as soon as possible, otherwise the patients are not able to eat normally without a nasogastric tube. Unfortunately, if the trismus fails to improve despite the surgery, the problem can become worse, affecting the ability to swallow. Surgery immediately after the gangrene should be avoided due to the poor clinical condition. Therefore, a long programme of proper nutrition must be guaranteed in order to build up the immune defences and make the patients fit enough to endure surgery.

Cancrum oris. Four years old girl. Seven and nine weeks post infection without toilette. Proper nutrition must be guaranteed in order to build up the immune defences.

Cancrum oris.

Five years old boy. Bacteria especially fusobacterium necrophorum provoque infection of superior and inferior molars.

In nearly every case it is important not to rush the reconstructive surgery (see Surgery of cancrum oris chapter), even when it is known that it may help the patient’s growth. Patients must be well nourished, in the best possible condition and ready to cooperate before reconstruction can be attempted. For these reasons it is extremely unusual to perform surgery on children under the age of seven. Only in cases of sequestration, where release of contraction permits better conditions for healing and growth, should surgery be indicated.

Anaesthesia is one of the most important factors to consider when the decision to operate has been taken. The better the clinical conditions, the higher the chances of enduring two or more hours of anaesthesia, and of surviving the postoperative period. The anaesthetist has to consider alternative methods of intubation, especially when trismus is present. It is recommended to avoid tracheotomy, blind intubation or high pressure ventilation. The anaesthetist’s equipment and skills must be as good as possible, to allow management of the whole clinical scenario, with infrastructure which can often be inadequate (see Anesthesia chapter).

Especially in longer interventions, a lack of material must sometimes be compensated for by the anaesthetist’s knowledge and experience. As a general rule, before the surgery, it is mandatory to check the availability of the necessary technology and of an adequate blood supply. The stratification risk is crucial: in fact, although the vast majority of patients have an uneventful post-operative course, major bleeding may occur in many. In the case of a severe haemorrhage, a lack of training and experience of the medical personnel, along with the absence of immediately available intensive care, may lead to death. Nurses must be trained and instructed to follow certain patients closely, and to recognise potentially fatal complications, especially during the night shift. In conclusion, to guarantee a good outcome it is essential that expert doctors, skilled nurses and trained physiotherapists work together during the whole perioperative course, which lasts at least two months, trying to minimize the most common complications.

Embryology of the face and buccal cavity

To understand the pathological alterations to the face and buccal cavity some knowledge of the embryology around this area during development is necessary. The events in question are recognised at the 4th week after fertilisation:

• At this time the bilaminar embryonic disc is converted into a trilaminar embryonic disc: each of three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) gives rise to specific tissues and organs. The notochord separates the ectoderm from the endoderm, except in two small circular areas: these are the oropharyngeal membrane at the cephalic region and the cloacal membrane at the caudal region.

• The development of the central nervous system, which started at the 3rd week, has reached the neural tube stage. As the neural tube closes, some ectoderm cells from the edges of the neural tube are left out and develop into the neural crest. These cells migrate in the developing embryo and differentiate into many types of tissue including the mesenchyme. In the head and neck region the mesenchyme from the neural crest or ectomesenchyme will take part in the development of cartilage, bones and connective tissue in the facial and tooth regions.

• The development of the ectoderm and the formation of the neural tube cause a deformation or folding in two embryonic areas: one in the cephalic region close to the oropharynx and the other in the cloacal region. During this process the oropharyngeal membrane covers part of the ventral face of the cephalic fold. It separates the stomodeum (the primitive oral cavity) from the developing pharynx. The growth of the cephalic fold is due to the migration of neural crest cells to the anterior part of the face.

• Following the appearance of cephalic and caudal curvatures, the embryonic disk undergoes a lateral folding amending the embryo into a cylindrical entity . The roof of the yolk sac folds ventrally to form the primitive gut and the embryonic disc lifts dorsally so that the ectoderm goes to coat the outer surface of the embryo that over looks the amniotic cavity. Then the embryo, which is a flattened tridermic disk, becomes a three-dimensional structure (fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2 Drawing of stomodeum (modified after Ten Cate)

Fig. 3 A and B the cells of the neural crest slide under the ectoderm in the facial region. C in each pharingeal arch the cells of the neural crest become the boundary of the central mesoderm region still present (modified after Ten Cate)

Face development

At the end of the 4th week the stomodeum is framed cranially by the cephalic fold and caudally by the heart prominence (fig. 2). The oropharyngeal membrane, which forms the floor of the stomodeum, begins to be absorbed, allowing communication between the stomodeum and the cranial extremity of the anterior intestine or foregut: the pharynx.

In the same period cells from the neural crest migrate (fig. 3):

• To the frontal part of the prosencephalon creating the definitive placode of the frontonasal prominence.

• To the lateral surface of the head where they invade the mesoderm, giving rise to the branchial or pharyngeal arches.

The frontonasal prominences and the pharyngeal arches will take part in the shaping of the face and the oral cavity

Pharyngeal apparatus

At the end of the 4th week of embryonic development, the branchial or pharyngeal arches appear at the level of the most cranial part of the anterior intestine or foregut. They grow in a cranio-caudal direction with lateral mesoderm enclosed between the ectoderm and endoderm: altogether there are six pairs of arches. These mesodermal arches are separated from each other by deep divisions where ectoderm and endoderm are in contact.

The external part of the division on the outer surface of the embryo (ectodermal) is called the pharyngeal groove and the internal part at the lateral wall of the pharynx (endodermal) forms the pharyngeal pouch.

Each segment consists of three components:

• Ectodermic – pharyngeal groove;

• Mesodermic – pharyngeal arch;

• Endodermic – pharyngeal pouch.

The derivatives from the pharyngeal apparatus are quite complex (fig. 4).

Each pharyngeal arch has a cartilaginous and a muscular component, a nerve and an artery. In the skeletal segments, the arch cartilage is formed from the mesenchymal cells of the neural crest, while the mesoderm of the arches produces the striated muscle.

Fig. 4

Pharingeal grooves: ectoderm and pharingeal pouches: endoderm.

Lateral views showing the development of the pharingeal apparatus.

The muscle fibres migrate in different directions and the nerve passes through to the interior of the arch of the adjacent rhombencephalon.

The motor component of the nerve spreads through the muscular tissue of the arch while the sensory branch is in the superficial epithelium coming from the arch. The arches give rise to specific nerves as follows:

• 1st arch: V pair – trigeminal nerve;

• 2nd arch: VII pair – facial nerve;

• 3rd arch: IX pair – glossopharyngeal nerve;

• 4th, 5th and 6th arches: X pair – vagus nerve.

Fig. 5

A. Lateral picture of the human hembrio of 32 days.

B. Micrography of SEM of the cranial facial region of the human hembrio of 32 days (modified after Moore).

Fig. 6

Drawing of facial prominences (modified after Duplessis) In the 5th week of development, the stomodeum is surrounded by five mesenchimal swellings called prominence.

The lower part of the face, and a large amount of the medial part, are formed from tissues from the first pharyngeal arch (also called the mandibular arch), while the other pairs of arches, together with the pharyngeal groove and the pharyngeal pouch are involved in building the neck region (fig. 5) above.

Facial prominences

In the 5th week of development, the stomodeum is surrounded by five mesenchymal swellings called prominences (fig. 6). These are:

• A frontonasal prominence: surrounds the ventrolateral part of the forebrain

• Paired maxillary prominences;

• Paired mandibular prominences.

Both maxillary and mandibular prominences derive from the first pair of pharyngeal arches.

They are initially separated by grooves which fill up progressively.

Facial growth depends on the influence of organisers from the prosencephalon and rhombencephalon. In particular the face is formed from a mesodermal mass arising between the cranial extremity of the developing brain and the heart prominence: in the centre is the depression which is the stomodeum or primitive oral cavity.

Since the 4th week the stomodeum has been closed posteriorly by the oropharyngeal membrane.

As the telencephalon develops, the frontonasal prominence becomes the roof of the stomodeum: the frontal part of this prominence forms the front while the nasal part becomes the facial border of the stomodeum and the nose (fig. 6).

Both mandibular prominences rapidly merge along the medial line to form the floor of the stomodeum. This represents the anterior extremity of the 1st pharyngeal arch (mandibular arch). Both maxillary prominences are derived from the first arch and shape the lateral walls of the stomodeum.

The maxillary and mandibular prominences result from the proliferation of the cells of the neural crest. The facial prominences are active growth areas of the underlying mesenchyme. This embryonic connective tissue is active from one process to another.

Facial development proceeds rapidly between the 4th and 8th week. The first parts to develop are the mandible and lower lip: they arise from the merging of the medial extremity of the mandibular prominence and the medial prominence.

At the end of the 4th week, bilateral oval structures appear on the surface of the frontonasal prominence. These ectodermal swellings are the nasal placodes, which will give rise to the olfactory epithelium. A horseshoe shaped part of the mesoderm rises up and transforms the nasal placodes in olfactive showers which are driven in an anterio –posterior direction on the stomodeum. The nasal placodes remain to develop the floor of the depression between these processes (fig. 6).

The proliferation of mesenchyme in the maxillary prominences causes them to expand and grow towards each other medially, pushing the nasal placodes closer together. The lateral nasal prominence fuses with the maxillary prominence forming the nasolacrimal duct between them.

Spreading in a ventral direction the maxillary prominence closes the lower edge of the nasal fossa and merges with the medial nasal prominence. The entrances to the nasal fossa become the primitive external nose. The medial nasal prominences, inside on the medial line, together with the proliferation of mesenchyme from the medial nasal prominence on the stomodeum give rise to the pre-maxillary regions of the face.

These regions give rise to the philtrum of the upper lip and to the medial part of the alveolar process which produce the incisor teeth and the primitive palate. The upper lip is built from both maxillary branches and the two medial nasal placodes.

The mandibular prominences penetrate deeply to form the lower lip and the lower part of the cheeks; the upper part of the cheeks is derived from the maxillary prominences. At this point however the lips and cheeks are not yet separated from the deeper tissues of the mandibular area.

The external nose is developing from the nasal prominences: the lateral prominences give rise to the lateral wings of the nose and the medial prominences to the medial part.

The medial nasal prominences, inside on the medial line, together with the proliferation of mesenchyme from the medial nasal prominence on the stomodeum give rise to the pre-maxillary regions of the face.

The upper lip is built from both maxillary branches and the two medial nasal placodes.

Fig. 7

Drawing of the primary palate (modified after Ten Cate)

Development of the nasal cavity and palate

The mesenchyme of the nasal prominences continues to grow and the nasal pits become deeper, shaping the primitive nasal cavity. The epithelial wall at the blind end of the primitive nasal cavity makes contact with the epithelium of the stomodeum roof making the oronasal membrane. This membrane ruptures and then the nasal cavity communicates with the stomodeum through a new channel called the primordial choana (pl. choanae).

The development of the palate occurs in different stages:

At the beginning of the 6th week the primary palate starts to form as a medial projection from the medial nasal prominence, and the nasal septum appears as a medial vertical structure originating from the frontal prominence (fig. 7).

Fig. 8

Drawing of the primary palate to secondary palate (modified after Duplessis)

Two mesenchymal projections arise from the deep superficial part of the maxillary prominence; these become the lateral palatine processes which grow each side of the tongue in a medial direction.

As they grow towards each other this causes the lowering of the tongue.

The free edges of the palatine processes fuse with each other and with the primary palate between them. This forms the secondary or definitive palate: the boundary between the secondary and primary palates on the medial line is marked by the incisive foramen (fig. 8).

The formation of the nasal septum and the secondary palate complete the division of the stomodeum into definitive nasal and oral cavities.

These processes take place between the 8th and 12th weeks of development.

Clefts of the lip and palate are common craniofacial anomalies. The defects are usually classified according to developmental criteria, with the incisive fossa as a reference point. These clefts are especially conspicuous because they result in an abnormal facial appearance and defective speech. There are two major groups of cleft lip and cleft palate. (See Tessier classification in “Cleft lip and palate” chapter).

• Anterior cleft anomalies include cleft lip, with or without cleft of the alveolar part of the maxilla. A complete anterior cleft anomaly is one in which the cleft extends through the lip and alveolar part of the maxilla to the incisive fossa, separating the anterior and posterior parts of the palate. Anterior cleft anomalies result from a deficiency of mesenchyme in the maxillary prominence(s) and the median palatine process.

• Posterior cleft anomalies include clefts of the secondary palate that extend through the soft and hard regions of the palate to the incisive fossa, separating the anterior and posterior parts of the palate. Posterior cleft anomalies result from defective development of the secondary palate and growth distortions of the lateral palatine processes, which prevent their fusion. Other factors such as the width of the stomodeum, mobility of the lateral palatine processes (palatal shelves), and altered focal degeneration sites of the palatal epithelium may also contribute to these birth defects.

A cleft lip, with or without a cleft palate, occurs approximately once in 1000 births; however, the frequency varies widely among ethnic groups; 60% to 80% of affected infants are males. The clefts vary from incomplete cleft lip to ones that extend into the nose and through the alveolar part of the maxilla. Cleft lip may be unilateral or bilateral.

A unilateral cleft lip results from failure of the maxillary prominence on the affected side to unite with the merged medial nasal prominences. This is the consequence of failure of the mesenchymal masses to merge and the mesenchyme to proliferate and smooth out the overlying epithelium. This results in a persistent labial groove. In addition, the epithelium in the labial groove becomes stretched and the tissues in the floor of the groove break down. As a result, the lip is divided into medial and lateral parts. Sometimes a bridge of tissue, called a Simonart band, joins the parts of the incomplete unilateral cleft lip.

A bilateral cleft lip results from failure of the mesenchymal masses in both maxillary prominences to meet and unite with the merged medial nasal prominences. The epithelium in both labial grooves becomes stretched and breaks down. In bilateral cases, the defects may be dissimilar, with varying degrees of defect on each side. When there is a complete bilateral cleft of the lip and alveolar part of the maxilla, the median palatal process hangs free and projects anteriorly. These defects are especially deforming because of the loss of continuity of the orbicularis oris muscle, which closes the mouth and purses the lips.

Anterior cleft anomalies result from a deficiency of mesenchyme in the maxillary prominence(s) and the median palatine process.

Posterior cleft anomalies result from defective development of the secondary palate and growth distortions of the lateral palatine processes, which prevent their fusion.

Facial bipartition type 0/14 of prof. Tessier P. classification. Operated with prof. D. Marchac. Hôpital Enfants Malades Necker.

A median cleft lip is a rare defect that results from a mesenchymal deficiency. This defect causes partial or complete failure of the medial nasal prominences to merge and form the median palatal process.

A median cleft lip is a characteristic feature of the Mohr syndrome, which is transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait.

A median cleft of the lower lip is also very rare and results from failure of the mesenchymal masses in the mandibular prominences to merge completely and smooth out the embryonic cleft between them.

A cleft palate, with or without a cleft lip, occurs approximately once in 2500 births and is more common in females than in males. The cleft may involve only the uvula; a cleft uvula has a fishtail appearance, or the cleft may extend through the soft and hard regions of the palate. In severe cases associated with a cleft lip, the cleft in the palate extends through the alveolar part of the maxilla and lips on both sides.

A complete cleft palate indicates the maximum degree of clefting of any particular type; for example, a complete cleft of the posterior palate is a defect in which the cleft extends through the soft palate and anteriorly to the incisive fossa. The landmark for distinguishing anterior from posterior cleft anomalies is the incisive fossa.

Unilateral and bilateral clefts of the palate are classified into three groups:

• Clefts of the primary or anterior palate (clefts anterior to the incisive fossa) result from failure of mesenchymal masses in the lateral palatal processes to meet and fuse with the mesenchyme in the primary palate.

• Clefts of the secondary or posterior palate (clefts posterior to the incisive fossa) result from failure of mesenchymal masses in the lateral palatine processes to meet and fuse with each other and the nasal septum.

• Clefts of the primary and secondary parts of the palate (clefts of the anterior and posterior palates) result from failure of the mesenchymal masses in the lateral palatine processes to meet and fuse with mesenchyme in the primary palate, with each other, and the nasal septum.

Most clefts of the lip and palate result from multiple factors (multifactorial inheritance), including genetic and nongenetic, each causing a minor developmental disturbance.

Several studies show that the interferon regulatory factor-6 (IRF-6) gene is involved in the formation of isolated clefts.

Some clefts of the lip and/or palate appear as part of syndromes determined by single mutant genes. Other clefts are parts of chromosomal syndromes, especially trisomy 13.

A few cases of cleft lip and/or palate appear to have been caused by teratogenic agents (anticonvulsant drugs). Studies of twins indicate that genetic factors are of more importance in a cleft lip, with or without a cleft palate, than in a cleft palate alone.

A sibling of a child with a cleft palate has an elevated risk of having a cleft palate, but no increased risk of having a cleft lip. A cleft of the lip and alveolar process of the maxilla that continues through the palate is usually transmitted through a male sex-linked gene. When neither parent is affected, the recurrence risk in subsequent siblings (brother or sister) is approximately 4%.

Other Facial defects

Congenital microstomia (small mouth) results from excessive merging of the mesenchymal masses in the maxillary and mandibular prominences of the first pharyngeal arch. In severe cases, the defect may be associated with underdevelopment (hypoplasia) of the mandible. A single nostril results when only one nasal placode forms. A bifid nose results when the medial nasal prominences do not merge completely; the nostrils are widely separated, and the nasal bridge is bifid. In mild forms of bifid nose, there is a groove in the tip of the nose.

By the beginning of the second trimester , features of the foetal face can be identified sonographically. Using this imaging technique, facial defects such as a cleft lip are readily recognizable.

Facial clefts

Various types of facial clefts occur, but all are rare. Severe clefts are usually associated with gross defects of the head.

• Oblique facial clefts are often bilateral and extend from the upper lip to the medial margin of the orbit. When this occurs, the nasolacrimal ducts are open grooves (persistent nasolacrimal grooves).

• Oblique facial clefts associated with a cleft lip result from failure of the mesenchymal masses in the maxillary prominences to merge with the lateral and medial nasal prominences.

• Lateral or transverse facial clefts run from the mouth toward the ear.

• Bilateral clefts result in a very large mouth, a condition called macrostomia. In severe cases, the clefts in the cheeks extend almost to the ears.

Cleft lip and palate

Cleft lip and palate are congenital malformations resulting from a failure of tissues to fuse, and are the commonest congenital facial deformities. The occurrence in the Western world is about 1 in 700, but higher in Central Africa at about 1 in 550. Paul Tessier listed 15 varieties of cleft (see drawing pag. 47) affecting different parts of the face such as the nose, cheeks, ears, eyes and forehead.

The cleft can be uni - or bilateral, and can vary from a small gap or incomplete cleft to a complete cleft into the nose.

Cleft palate occurs when the two parts of the hard palate fail to join completely so the roof of the mouth remains open making one cavity with the nasal cavity and could be complete (soft and hard palate) or incomplete (soft palate only).

The pathology is much more distressing for children who may develop psychosocial problems due to peer relationships, particularly for girls. At an early age the problem is not as hard as in later life.

The deformity with the resultant speech impediments, gives the perception that suffers are less attractive and intelligent. In addition the extremely poor social, cultural and economic conditions found in some parts of Africa result in a situation, rarely seen on other continents,

Young girl with unilateral cleft lip on the left side, before and after reconstruction.

Surgery: the nutritional status has to be as good as possible.

Boy with unilateral incomplete cleft lip on the left side, before and after reconstruction.

whereby human being are condemned to suffer their entire life with malformations and consequent disfigurement. So most patients, suffer from lack of confidence and become unhappy and angry. Moreover, African families are often large, so they, usually, have less parental care than their siblings further worsening their psychological development.

Surgery for the correction of these kinds of congenital malformations is complicated and to increase the chances to have an uneventful perioperative course, the nutritional status has to be as good as possible.

We often have to wait several months before we can proceed.

Self portrait by a patient.

Cleft lip Classification

• Unilateral: one nostril is involved and becomes lower;

• Bilateral: the nose becomes wider and shorter.

The cleft could be complete or incomplete, depending on whether or not it extends into the nose.

A cleft lip can affect every function of the face, disrupting growth of the maxillary and malar bones, leading to malnutrition, malocclusion, ear disease such as Eustachian tube malfunction, reduced air conduction to the middle ear, naso-respiratory obstruction and deafness.