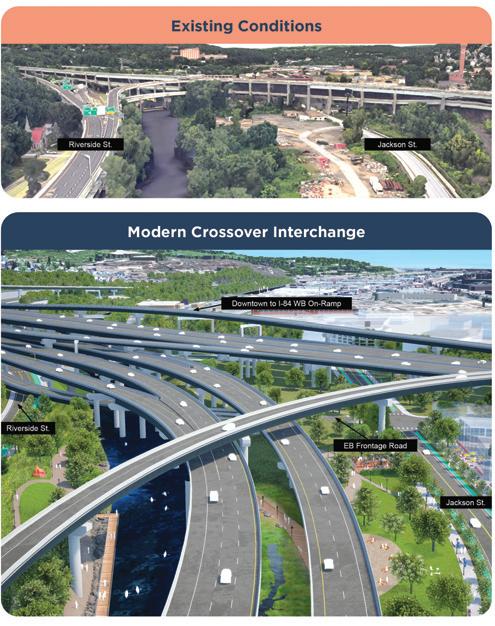

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) is evaluating two options for replacing the so-called “Mixmaster” interchange of highway bridges in Waterbury following a $223.7 million rehabilitation of the crossroads of Interstate 84 and Connecticut Highway 8.

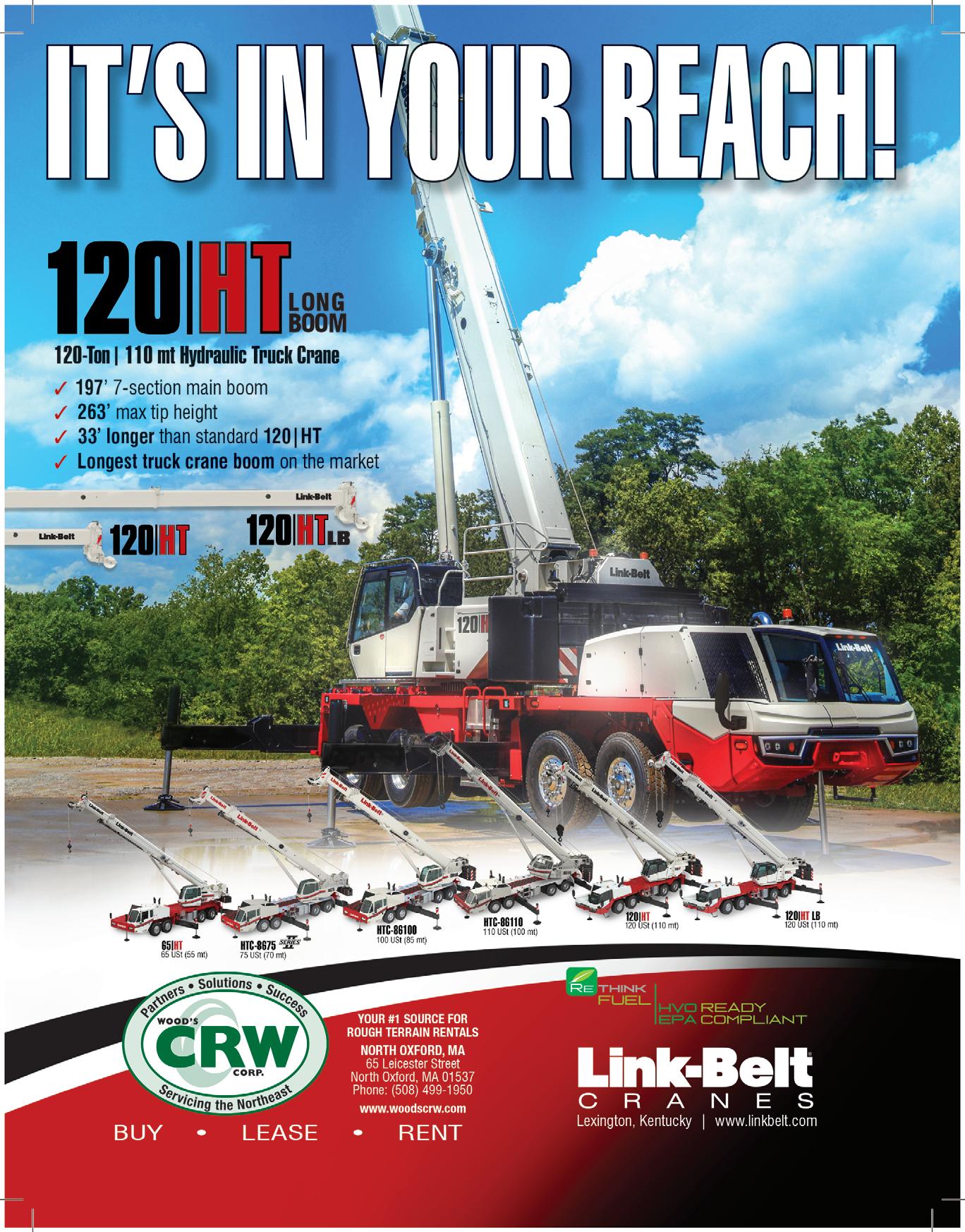

The first option for the “New Mix” program, or the Modern Crossover Interchange, would involve reconstructing Conn. 8 ramps and bridges to the east of the Naugatuck River.

The second alternative is known as the Naugatuck River Shift and would move the river toward the east to provide space for unstacking the series of Conn. 8 ramps and bridges.

On Aug. 26, 2025, CTDOT officials unveiled the two options after reviewing and analyzing potential designs for the permanent replacement of the interchanges that carry I84 and Conn. 8 over both downtown Waterbury streets and the river. The chosen alternatives are projected to cost $3 billion to $5 billion in 2022 dollars.

Built in 1968, the intricate network of stacked, overlapping bridges and elevated ramps was dubbed the Mixmaster after a trademarked kitchen mixer made by Sunbeam Products.

At that time, the interchange was considered innovative because the stacked bridges allowed the crossroads

One day, the 18 acres along Kossuth Street on the lower east side of Bridgeport, Conn., could be the site of a minor league soccer stadium, a hotel and more than 1,000 housing units.

But first, developer Andre Swanston and his Connecticut Sports Group (CTSG), per the state’s environmental regulations, need to exorcise — or at least safely contain — the ghosts of Bridgeport’s industrial past as ground contamination left behind by manufacturers and other operations that, beginning in the

1880s, at one time or another occupied that same piece of land.

According to a recently-released environmental site assessment, obtained by the Connecticut Post in Bridgeport, among the former companies that used the property were an iron works, a coal yard, the American Graphophone Co., the Frisbie Pie Co., textile and corset makers, a marine engine works business, the Bridgeport Paper Box

SENNEBOGEN, in kee philosophy to maxim created UPTIME Kits

eping with their mize uptime, has Whether you are a service technician i road, these kits have need for every service and PM task in one p created to save you t Managing hundreds o parts, from belts and and special tools bec single part number to n-house or on the everything you e, maintenance place. They were ime and money. of related service d nuts to O-Rings omes easy with a o order and stock

They are:

• Easy to order and ea t d t stock asy to s l

components and too

• Ideal for stocking se and trucks

Choose from the follo

• Central lubrication

• Preventive mainte

• O-Ring kits

• Electrical service k

• Hydraulic service k And the best thing is in stock and ready to built to match your m and series. Count on in-house. For more in UPTIME Kits, scan th s that these kits, go, are custommachine model SENNEBOGEN nformation on he QR code.

Hydraulic service k :kits shops ols ervice owing kits system kits nance service kits its kits

NO North our in parts com with customers maxim commitment h about more Read ontract Demolition C st in parts repair the have virtu and I machine another in If back. to front every come t a have They echnician machine, wntim warehouse. American ready-to-ship of inventories plete for uptime izes aftersale Machine” he “Beyond our ow , Bloomfield Hills, MI or quickly. back unit the g I k they Since do no lose ally bring just [they] situation, a have I over go to month a once through wntime… ock. get theSENNEBOGEN

When the axe fell in early 2025 on $882 million in federal funding aimed at helping communities prepare for future flooding, it came paired with a critique of the program’s very purpose.

The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program “was yet another example of a wasteful and ineffective FEMA program,” an unidentified Federal Emergency Management Agency spokesperson asserted in an April 4 press release. “It was more concerned with political agendas than helping Americans affected by natural disasters.”

Emily Granoff, the deputy director of housing community and development in Chelsea, Mass., was assisting another town with smaller-scale grant work before the BRIC cuts were announced. Upon hearing the news, that community reached out to Granoff see if Chelsea’s funding was impacted, and she assured them that it was not.

But both of the Boston suburbs of Chelsea and Everett had money on the line — a $120 million flood resilience project for the Island End River that included a storm surge barrier, a storm surge control facility and wetland restoration set to begin construction in 2026.

“I looked up the press release,” Granoff said. “And then I cried for a bit.”

The local toll would not be fully felt for two weeks, when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts estimated that some $90 million in funding and potential grants would be pulled, almost $50 million of which was dedicated to the Chelsea and Everett endeavor.

Overnight, project managers overseeing resilient park and stormwater flooding projects, updating drinking water and watershed regulations and preparing for the best ways to hold rising waters at bay rushed to triage.

Granoff was among them as the project manager for Chelsea in a partnership with Everett.

Roughly between and beneath the ground of the two Gateway Cities — both historic industrial midsized urban centers — passes the Island End River. This tributary of the Mystic River generates dramatic flooding during serious coastal storms, sending ft. of water rushing over nearby roadways as well as commercial and industrial sites, noted CommonWealth Beacon, a Boston-based nonprofit and non-partisan news service, on Aug. 24.

The risk of worsening storm surges is difficult to overstate, Granoff said as she walked the border of the proposed project site around the spot where the river dips into a massive culvert to pass beneath her city.

By 2081, the kind of one-in-100-year storm surge events proportional to Hurricane Sandy could be annual occurrences, accord-

...the Commonwealth of Massachusetts estimated that some $90 million in funding and potential grants would be pulled.

ing to a 2022 study from the Woodwell Climate Research Center.

Within the 2070 flood risk zone sits Chelsea High School, a Market Basket, U.S. Highway 1, Massachusetts Highway 16, commuter rail and freight rail tracks, a Federal Bureau of Investigation building and the New England Produce Center that distributes produce to 8 million people across the Northeast.

“Basically 10 years ago, the cities of Everett and Chelsea were evaluating their flood vulnerability and found that Island End River was a huge one — not just for us, but for those 8 million people and for anyone who drives into Boston from the North Shore,” Granoff said.

She added that those highways and the

produce center will be flooded from a coastal rainstorm, and because it is not feasible to move them, they must be protected.

When Chelsea and Everett were first developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, wetlands became the site of a heavily industrial district full of critical infrastructure.

Over the past decade, though, local planners determined that defending that infrastructure would require a barrier to prevent water coming up from the culvert beneath the island and spilling into its old riverbed and marshland path.

Part of the solution is a 3,000-sq.-ft., $42 million underground storm surge control

facility that would sink 8-10 ft. below ground and rise as much as 8 ft. above ground next to the small M&T bank building near the outlets of the Market and Beacham street culverts.

Because the river flows beneath the area, an above-ground storm barrier that stops water from washing over the land would not stop the surge from blasting through the large culvert tunnel and flooding out through storm drains. If built, the control facility would manage the flow of water under Chelsea and Everett while the barrier would keep most of the water from flooding the cities.

Walking along the path where the 4,460 linear-ft. storm surge barrier would go involves weaving in and around city and private land as the wall includes gates to allow people and vehicles to pass though when the area is not flooded. The barrier’s path has changed over the years to avoid crossing rail tracks or to make sure the businesses along the nearby port can access the water on which they depend.

On the Everett side, the barrier would wind around commercial sites to higher ground, ending roughly where 2070 estimates expect just 1-ft. of flooding in intense

18

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) and the City of Boston have “tentatively” agreed to eliminate a major source of delays on the Green Line with a new dedicated transitway that will run down the middle of Huntington and South Huntington avenues in the city’s Mission Hill neighborhood, StreetsblogMASS reported Aug. 25.

In early August 2025, the MBTA issued a “request for qualifications” for engineering firms to prepare shovel-ready plans for “accessible station designs for Mission Park, Riverway and Heath Street stations [as well as] new transitway and track improvements” on the Green Line’s E branch.

In an update posted to the city’s website, Boston officials confirmed that “based on what we have learned in our conversations with community members, with the MBTA and with other stakeholders, such as the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the project will be moving forward with a centered Green Line track with dedicated lanes for trains and buses. Stops will be served by side platforms.”

The E branch between Brigham Circle and the end of the line at Heath Street constitutes the only part of the MBTA’s rapid transit system where trains still share a roadway with motor vehicles.

Those streets — Huntington and South Huntington Avenues — currently have four lanes for moving vehicles, with Green Line tracks in the center lanes and two parking lanes along the curbs.

Besides forcing transit riders to wait in traffic, this design also directs passengers to board and disembark in the middle of a busy street.

Both Huntington and South Huntington Avenue have been flagged as high-crash streets under the City of Boston’s Vision Zero prioritization plan.

The proposed center-running transitway would mitigate both of those problems by keeping cars and trucks off the Green Line tracks and building new, Americans with Disabilities Act-accessible boarding platforms alongside the new transitway — similar to the Green Line’s C branch stops on Beacon Street in Brookline.

Converting the center lanes to a dedicated

transitway would consolidate private vehicle traffic into a single lane in each direction — a roadway layout that is considerably safer. The new boarding platforms would require additional roadway space and might require the removal of some on-street parking zones.

The Mission Hill project also could benefit two of the MBTA’s frequent-service bus routes, the 39 and the 66.

Officials from both the MBTA and the city confirmed that the transitway concept is being designed for both trains and buses, and bus passengers would share the same stops as Green Line riders at the new Mission Park, Riverway and Heath Street stations.

During peak hours, buses on those two routes operate with average speeds below 12 mph, according to data from the Boston Transportation Department.

Besides meeting accessibility requirements, the MBTA also needs to redesign many of its Green Line stations to accommodate its new “Type 10” trains, which are currently scheduled to enter service in 2027. Because those trains are longer, the agency has been consolidating some Green Line stops to lengthen the platforms that the new trains will require.

In previous presentations, MBTA officials have indicated that Fenwood Road, which is only approximately 500 ft. from the Brigham Circle stop, and Back of the Hill, 400 ft. away from the Heath Street transit stop, would be eliminated.

MBTA officials told StreetsblogMASS that the new E Branch transitway and stations are currently scheduled to begin construction in the fall of 2027; the agency hopes to open the new facilities before the end of 2029.

Plans also are being advanced by the MBTA to improve accessibility on two other Green Line branches before the end of the decade.

One that would rebuild and consolidate several stops along the C branch through Brookline is currently under contract and has an expected completion set for next year. The other will upgrade 10 stops on the B branch along Commonwealth Avenue through Brighton. It, too, is slated to begin in 2026, with a finish date likely in late 2027, StreetsblogMASS noted.

With a vote of 1,374-402, residents in Longmeadow, Mass., south of Springfield, chose to fund a $151.59 million combined middle school on the town’s existing Williams Middle School campus.

The project, more than a decade in the making, became controversial in 2024, when abutters to the site at 410 Williams St. opposed the location. The next step in the process is a townwide ballot vote on Sept. 30 to approve the debt exclusion for the construction effort.

Voters, many of whom attended with their children, packed into Longmeadow High School to weigh in on whether to fund the middle school project.

Set in the geographical center of the town, Williams Middle School was built in 1959 as part of a massive upsurge of school construction nationwide needed to accommodate the post-World War II baby boom. Nine years later, a second school was needed in Longmeadow, leading to the building of Glenbrook Middle School.

In the 57 years since then, the condition of the two structures has deteriorated, while the academic and security needs of the school community have changed, according to The Reminder, a daily news source in nearby East Longmeadow, on Sept. 10.

In 2007, Longmeadow officials first began exploring solutions for its middle schools.

After the town’s high school was renovated in 2013, Longmeadow once again turned its focus to the middle schools and applied to participate in a Massachusetts School Building Authority (MSBA) program that reimburses municipalities for a

portion of eligible costs associated with the renovation or construction of school buildings. The state’s sales tax helps fund the MSBA.

The town was finally accepted into the program in 2022, and local voters approved a feasibility study shortly thereafter.

While the study looked at options for renovating or building new construction for both Williams and Glenbrook, the MSBA would only fund one new school, and it was determined that Glenbrook was in the greatest need of replacement.

However, the state agency did allow for a combined middle school as a solution, according to The Reminder.

The cost of new construction also was found to be slightly less expensive than the $159.27 million it would cost to repair both middle schools and bring them up to code without any improvements.

The MSBA has agreed to reimburse the town for $54.8 million of the project, leaving taxpayers to fund $96.8 million. By

using a debt exclusion, taxpayers would pay the cost of the debt service for the life of the bond, without it permanently increasing the levy limit.

Longmeadow’s Finance Committee, Select Board, and School Committee each unanimously recommended the project in the months leading up to the vote. Finance Committee Chair Erica Weida said she was “confident” that the project was “financially optimal” for the town.

Prior to Longmeadow residents overwhelmingly approving the combined school proposal, Nicole Choiniere, a school committee member, emphasized that a vote against the middle school project was not a vote for renovating the existing middle schools; instead, she noted the process with the MSBA would come to a halt.

If that were to happen, the town would be forced to fund repair work for the schools while it waited several years to be accepted back into the MSBA’s program. Even then, she said the state agency would

only fund one of the two middle schools and renovating one school over the other would be unfair.

M. Martin O’Shea, the superintendent of Longmeadow Public Schools, said traffic and safety have been built into the design for the combined school. A traffic signal would be installed at the east driveway of the new site, and a turn lane would relieve congestion along Williams Street.

In addition, he noted, the middle school’s driveway would allow more than 100 cars to queue for student drop-off and pick-up without the line backing up onto the street. Meanwhile, a sidewalk on Williams Street and a raised crosswalk with a lighted beacon would make walking to school safer than it is currently. The location maximizes the number of students that can travel to the school on foot or by bike, O’Shea said. A start and end date for the construction of the proposed middle school in Longmeadow has not yet been determined.

Nearly two years after a pair of ferocious, wind-driven winter storms pummeled Maine’s coastline, steps are finally being taken to protect one of the state’s most visited historic sites.

A permit has been filed and a $1 million matching grant requested to address severe erosion along the bluff at Pemaquid Point Lighthouse Park in Bristol.

While structural repairs to the 19th-century-built lighthouse and surrounding buildings have already been completed, park officials say one final — and critical — project remains: reinforcing the eroded bluff beneath the main parking area.

“They are going to cut back to the retaining wall to make it a more gradual slope,” said Shelley Gallagher, the lighthouse park’s director, in speaking with WMTWTV in Portland.

On Jan. 11, 2024, the lighthouse’s bell house, which was constructed in 1835 at the tip of the Pemaquid Neck, was largely destroyed by the first of two tempests over three days. A full restoration of the light-

house and bell house was completed 8 months later.

The bluff upon which the two coastal structures rested, however, also suffered significant damage as a result of last year’s storms, and engineers warned it could eventually collapse into the ocean if left unaddressed.

WMTW-TV noted recently that a damage survey has been completed, and a repair plan is in place, but Gallagher told a station reporter that the process is especially complicated due to the sensitive nature of the location.

“There’s a lot to get through. It’s coastal. We have to go through the [Maine Department of Environmental Protection] and through all of the environmental regulations but it’s also going through the historic regulations,” she said.

The project will be partially funded by

the proposed $1 million matching grant, though the final cost could vary depending on what is discovered during the next phase of the project. Until all necessary permits are approved and a full damage assessment is completed, the timeline for repairs remains uncertain.

The long-awaited repairs are aimed at preserving both the historic value and natural beauty of the park for future generations.

Pemaquid Point Lighthouse Park is both an environmentally protected area and a site listed on the National Historic Register. In addition, the land is home to migrating bird species, which are protected by federal law. Due to that, no further testing or construction work can begin until the birds leave for their winter migration. Gallagher said that she expects the bluff’s repair work to start shortly after that.

Officials at Waterville, Maine’s Colby College announced Sept. 9, 2025, that the school had received a $150 million lead commitment for a new science complex that will catalyze a half-billion dollars of investment in science and technology. The anonymous gift is the largest in the school’s history and one of the most generous for any liberal arts college.

The new funding will elevate Colby’s role in Maine’s burgeoning science ecosystem, create new engineering and public health programs to enable faculty and students to lead in new and emergent fields, and make it possible for the college to build a new science complex, according to a news release on the school’s website.

The new facility and programs promise to deepen opportunities for students and faculty to identify solutions for some of the most vexing health and environmental issues facing the state of Maine and the country.

In addition, the funding will allow the Colby to build on its collaborations with science research organizations, support the Maine’s K-12 STEM education, create the right environment for rural areas to compete in science and technology and generate 21stcentury jobs in a fast-paced innovation economy.

“Colby has long had outstanding science programs,” said David A. Greene, the college’s president,. “And that work has been deeply connected to other scientific organizations across the state and around the world. These investments will allow us to take that work to a new level, ensuring that science education and the application of scientific knowledge and discovery are addressing the needs of Maine.

“Importantly, it allows Colby to be at the forefront of educating the next generation of science and technology leaders who will carry with them a deep understanding of the human dimensions of science and the need to ensure that the power of science is used for a broader societal good,” he said.

At the core of this overall investment is the development of a $300 million science complex and the expansion of the science curriculum to include more applied science and engineering.

The new facility, which is expected to open in 2030, will address current and future science educational and research needs and lead to the creation of academic programs that address the dramatically and rapidly changing fields of science and technology. To that end, Colby will significantly expand its science faculty and introduce a suite of forward-looking and solutions-oriented engineering and applied science programs.

These will likely include biomedical engineering, environmental engineering, materials engineering and public health, and will

build on recently-created majors and minors in fields that include data science, computational biology, marine science and environmental computation.

School officials believe the new science complex will support the radical changes in how science is practiced today and in the future. Its square footage will provide enough room for new teaching and research laboratories, classrooms, offices, fabrication labs, specialized equipment, computing infrastructure and gathering spaces.

Colby College also has explored a number of different conceptual models for organizing the space in the new building to blur disciplinary boundaries, encourage relentless collaboration and integrate research and teaching across all areas of the facility. A key part of this effort will be creating a set of shared areas with specialized equipment and instrumentation (e.g., imaging technology, sophisticated computation resources, etc.) in the new complex that bring researchers into spaces shared among disciplines.

“Students who join the Colby community with an interest in STEM get the best of both worlds, in the sense that they directly engage in leading-edge scientific research as collaborators with Colby faculty and our incredible network of partner research institutions, with all the advantages of a holistic liberal arts education,” said Colby College Provost Denise Bruesewitz. “Our students will be

prepared to be the next generation of science and tech leaders.”

Over the last few years, Colby has made a number of strategic investments that are part of its focus on the sciences.

Most recently, the school announced the establishment of a Center for Resilience and Economic Impact, which will employ scientific approaches to strengthening communities across Maine.

In addition, in an initiative designed to support broader state efforts, Colby partnered with the Central Maine Growth Council on the planning and development of a high-performance computing hub in Waterville that is under final consideration for federal support.

Among the school’s other science-based investments are:

• the Davis Institute for Artificial Intelligence, the first of its kind at a liberal arts school;

• the development of a 500-acre coastal research campus via the acquisition of Maine’s Allen and Benner islands; and

• the launch of the McVey Center for Computational and Data Sciences.

Colby College also has created a series of programs to support creativity, research and innovation, including the Buck Lab for

Climate and Environment, the Linde Packman Lab for Biosciences Innovation and the Halloran Lab for Entrepreneurship.

Another key part of the school’s science initiative has been its commitment to building and expanding partnerships with leading science and technology organizations in Maine, including the Harold Alfond Center for Cancer Care, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, The Jackson Laboratory and MDI Biological Laboratory.

This latest investment in science and technology programs will be developed to complement and strengthen the work at these and other organizations in the state, according to Colby officials.

“We’ve worked closely with Colby College for 15 years to introduce students to cutting-edge research in the marine and environmental sciences,” said Deborah Bronk, president and CEO of Bigelow Laboratory in East Boothbay, Maine. “This major new investment will build on that foundation, catalyzing innovation and opening new opportunities in marine resources, climate resilience and sustainability.

The college also will direct these new investments to areas that are explicitly designed to address the challenges that have become endemic to Maine — from having one of the highest rates of cancer in the country to a legacy of harmful pollutants impacting soil and water quality.

Kenco

Curb Lifts

Concord, NH Berlin, CT

Middleboro, MA

Scarborough, ME

Zero percent financing for 60 months on JCB skid steers including wheeled, tracked, and even the revolutionary Teeleskid!

Zero percent financing for 60 months on JCBcompact excavators including the 19C, 50Z, 55Z, 85Z, and 86C!

Zero percent financing for 72 months on JCB35Z!

Zero percent financing for 60 months on the JCB3CX and 4CX backhoe loaders!

Zero percent financing for 60 months on JCB411, 417, 427, 437, and 457wheel loaders!

Oh... and don’t forget to ask about our 5-year/3,000 hour warranty!

A municipal building boom is officially in full swing in Amherst, Mass., as dirt is flying on three important projects in the community: a new elementary school, an expansion and renovation of the Jones Library and a new track and field at the high school — all of which went through years of discussion before breaking ground.

At 70 South East St., next to Fort River School, construction that began in March of 2025 on the new $97.5 million elementary school that will house 575 K-5 students remains on schedule for a completion just in time for the 2026-2027 school year, the Daily Hampshire Gazette in Northampton reported Aug. 10.

Meanwhile, in the center of Amherst, work on the $46.1 million Jones Library expansion and renovation is getting under way, even though most of the activity is not yet visible from the outside.

And at Amherst Regional High School, large piles of dirt can be seen for the $4.11 million track and field overhaul.

Future work in the city’s pipeline could include a new Amherst Department of Public Works headquarters and south Amherst fire station, as well as $2.8 million in improvements to the Bangs Community Center.

Helping to oversee each of the three ongoing construction efforts is Bob Peirent, the city’s special capital projects coordinator, who recently provided an update that indicated there are no major concerns with the timelines for completing each project.

For the three-story, 105,750-sq.-ft. elementary school building, the prime contractor, Waltham, Mass.-based CTA

Construction Managers LLC and its subcontractors should have work finished around mid-August 2026.

“The project is going well,” Peirent told the Daily Gazette.

Though complicated by a delay earlier in its construction, which necessitated CTA crews getting on site in the middle of last winter rather than in the fall, the expectation remains that the school building will be fully functional for the entire 2026-2027 school year.

Early site work began in February 2024 using a technique known as pre-loading in which the soil is compacted to provide the base for raising the building, according to the Northampton news source.

Peirent noted that all of the structure’s steel is in place, the concrete floors have been poured and the exterior walls are being finished. He added that crews are now beginning to tackle the school’s mechanical and electrical work. Approximately half of the more than 80 geothermal wells that will provide heating and cooling to students, teachers and staff are already dug as well.

Until the new school is ready for occupancy, students will continue attending Fort River School for the fall of 2025 and spring of 2026. After they move into the building, the old one will be closed and eventually demolished prior to the site being repurposed for playing fields and other amenities associated with the new facility.

At the Jones Library at 43 Amity St. in Amherst, where the construction is fully mobilized, the most obvious change to the property is the installation of a construction fence around the perimeter, a number of con-

struction trailers and portable toilets and the removal of two large trees from the neighboring Amherst History Museum grounds, which will ease the expansion and renovation work for Fontaine Brothers Inc., located in Springfield.

The trees were taken down at the request of the Amherst Historical Society, which had originally intended to preserve them, before opting instead to ask Fontaine to carry out the work.

Inside the historic 1928 portion of the Jones Library is where most of the renovation is happening, the Daily Gazette reported, with floors, stairs, woodwork and fireplaces carefully protected from any damage as a result of the work.

Peirent told the newspaper that a lot of time is being invested in ensuring the historic building remains intact during the demolition of the 1990s-era addition.

Once that is done, razing the library’s addition also will be completed with care, he said, with excavators pulling down that part of the building that includes the atrium and the Woodbury Room.

“Everything gets taken apart piece by piece,” said Peirent.

The other reason for performing a careful demolition is that 75 percent of the debris that is generated must be repurposed, and will include separating the metals, the concrete and the drywall. A typical industry procedure, the City of Amherst also requires the practice, along with the stipulation that any asbestos and lead paint be disposed of properly, he said.

Once the library addition is razed, the new expansion’s foundation will be poured this fall and its steel structure erected, with the entire project slated to be finished by December 2026.

The Jones Library is currently operating from temporary quarters at 100 University Dr. Colliers, as the owner’s project manager, has met with neighboring businesses to ensure that The Drake performance venue, next door to the library, has an emergency exit and space for its dumpster and that the nearby CVS Pharmacy is not losing any of its parking spaces.

The other major project currently moving along in town is the track and field next to Amherst Regional High, a project under the supervision of M.J. Catalado Inc., a landscaping and construction company in Littleton, Mass.

According to the Daily Gazette, the eightlane track is beginning to take shape with its gravel base ready to be graded and finetuned to a certain elevation before the first layer of asphalt is put down later in August. Following that, a second layer of asphalt will be placed on top of the first, and a urethane product will be applied as the top coat.

The high school may be able to host track meets next spring for the first time since 2018, when it was determined that the current track was no longer suitable for competition.

Plans call for a natural sodded field to be installed inside the track, with an additional seeded field also set to be built.

The Northampton news source also noted that the new high school track could possibly be used by athletes and the public this fall, though it is not expected that any sports events or practices would be allowed on the playing fields until the fall of 2026 at the earliest.

MIXMASTER from page 1

of the two highways over the Naugatuck River to be constructed in a smaller footprint. It originally had a life span of 50 years.

“The Mixmaster was once a modern engineering marvel, but today it no longer meets the needs of travelers and the greater Waterbury community,” CTDOT Commissioner Garrett Eucalitto said in a statement. “We’re excited to move this plan forward, which was based on what we heard directly from residents and businesses. This transformative initiative will change how people safely and conveniently travel through and around Waterbury.”

The Mixmaster was originally designed to accommodate approximately 100,000 motor vehicle trips a day, but that number has now nearly doubled to 190,000 daily trips. In another 20 years, the state agency expects the number to approach 225,000.

As a result, the wear and tear from all that use across the interchange required multiple major rehabilitation projects over the years.

In November of 2024, CTDOT completed its multi-million-dollar effort to structurally rehabilitate the interchange and extend its life span for another 25 years while plans for a permanent replacement are made. Work on the renovations first began in 2018.

The project included replacing decks on 21 spans along southbound Conn. 8, 36 spans in the northbound lanes and building a temporary bypass and a U-turn. Major structural repairs consisted of strengthening the girders, columns and beams to address fatigue and corrosion.

The plans for I-84 eastbound and westbound included deck patching, paving and joint installation, steel repairs and strengthening, painting and substructure repairs and the installation of sign support structures.

Interstate 84 in Connecticut serves as a critical east-west transportation link between Massachusetts and I-90 to the east, and New York State and beyond to the west. Conn. 8 extends from Bridgeport and the I-95 corridor on the south coast, north to the Massachusetts state line. In Waterbury, the highway parallels the Naugatuck River.

The two replacement options announced by CTDOT aim to improve safety and mobility on I-84 and Conn. 8 as well as upgrade the multimodal connections within the surrounding roadway network. In both alternatives, known as the Modern

Crossover and the Naugatuck River Shift, the I-84 and Conn. 8 structures would be unstacked and reconstructed with an expected life span of more than 75 years.

“Progress takes patience, and while this work will take decades to fully complete, we are committed to improving lives through transportation by implementing — and completing — certain projects within the next five years,” Eucalitto said.

His agency’s announcement noted that the two design options originated through the New Mix Planning and Environmental Linkages Study (PEL). Over the last several years, strategies for improving transportation for all users were identified in alignment with Waterbury’s economic and developmental goals. The PEL study also involved public outreach and participation.

In addition to the pair of replacement

not be able to address the interchange’s operational and safety standards.

Another alternative that CTDOT dismissed, according to CT Insider, was constructing a tunnel within the project’s footprint because the projected construction and maintenance costs would be considered unreasonable and impractical due to the channel length needed to construct a functioning interchange. The topography also presented limitations because of the required depth for such a tunnel.

CTDOT noted that the Modern Crossover alternative plan would result in a configuration that satisfactorily addresses the needs of the interchange. Not only would it reduce the potential for crashes but provide substantial benefits for the surrounding community while minimizing effects on environmental and community resources.

In addition, this option would allow for riverfront access along both riverbanks of the Naugatuck River.

The plan would replace the Mixmaster with a full system interchange, using elevated structures that would cross over or under one another. Under this option, I-84 near the core of the interchange would be located just south of the existing alignment, while Conn. 8 would be relocated east of both the existing alignment and the river, just south of I-84. The state highway also would remain on the west side of the Naugatuck River north of I-84.

Likewise, the Naugatuck River Shift alternative also would meet the interchange’s requirements, CTDOT concluded.

options, CTDOT reported that the analysis also identified breakout projects, including some that have been constructed and several that are in various stages of conceptual development and design.

These breakouts are independent projects designed to improve safety and mobility for the surrounding transportation network, while the state and federal environmental continue to review and design the interchange, CT Insider reported.

State transportation officials ruled out an in-place reconstruction due to the construction difficulties involved, in addition to another rehabilitation of the Mixmaster in 2045 because it would not substantially improve the interchange’s functionality, nor would it extend its lifespan relative to the cost of a full replacement. They also concluded that continued rehabilitation would

The option anticipates the river’s path could be shifted east to a more favorable position for the Conn. 8 roadway. Moreover, this design choice would allow for ample opportunities for riverfront access along the eastern bank of the Naugatuck and would benefit transportation, safety and environmental and community resources.

Like the Modern Crossover plan, the Naugatuck River Shift option also would replace the Mixmaster with a full system interchange that would be built in an unstacked configuration.

Under this particular scenario, though, I84 would be located just south of the existing alignment near the interchange core and Conn. 8 would be reconstructed on the west bank of the Naugatuck River. To accommodate the unstacked Conn. 8 configuration, the river would require partial relocation. The width, river flow and capacity of the shifted portion would be maintained in the final condition.

FEMA from page 4

storm events, an annoying but manageable height.

In Chelsea, plans call for creating a new high ground where the barrier can taper off behind a revamped riverwalk and restored salt marsh that are part of the 18,000 sq. ft. of nature-based resilience improvements that include wetland upgrades.

The Island End River project was the largest chunk of the $90 million in Bay State BRIC cuts, but the impact of the federal action will be felt throughout Massachusetts.

“The Trump Administration has suddenly ripped the rug out from under cities and towns that had been promised funding to help them upgrade their roads, bridges, buildings and green spaces to mitigate risk and prevent disasters in the future,” Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey said in April. “This makes our communities less safe and will increase costs for residents, municipalities and businesses.”

In dramatically re-orienting FEMA — the federal agency responsible for coordinating the country’s disaster relief efforts — the White House cancelled all BRIC applications from Fiscal Years 2020-2023, imperiling states from New England to the Gulf Coast. Any undistributed funds would be immediately returned either to the Disaster Relief Fund or the U.S. Treasury, according to FEMA.

Two major Boston resilience projects — Moakley Park in South Boston and Tenean Beach in Dorchester — are either having millions in funding pulled or their grant applications cancelled, the CommonWealth Beacon noted. Funding for culvert projects in Acton, Brockton, Grafton, North Adams and Taunton also were eliminated.

More than two dozen Democratic members on Capitol Hill sent a letter to the acting FEMA administrator on April 23, urging the administration to reconsider the cuts.

“Ending the FEMA BRIC program is a terrible mistake and marks a huge setback for many climate-vulnerable cities and towns in my district,” wrote Mass. Rep. Seth Moulton, who helmed the letter.

Newburyport Mayor Sean Reardon told the CommonWealth Beacon that his town was expecting to receive a BRIC grant to protect its watershed and drinking water supply, but “will now need to find other resources to do this important work.”

Ironically, project proponents point out that slicing away BRIC funding in the inter-

“Municipalities aren’t built to do this kind of huge infrastructure project.”

Emily Granoff Housing Community and Development

ests of shrinking the federal budget could actually cut the other way. Projects must go through a cost-benefit analysis to compare the upsides of a resilience project to what it would cost to build. If disaster washes up to a municipality’s doors due to flooding, FEMA gets the call and bears the cost.

Or, at least, that was how the system worked for decades before Trump signed an executive order in March directing state and local governments to “play a more active and significant role” in resilience and preparedness. The administration has since denied some federal funding to disasterstruck areas.

Along with the $50 million BRIC funding, Chelsea and Everett expected to contribute $10 million in combined local funds. Planners have been working with the state to secure $45 million in funding and seeking the remaining $14.8 million through additional state and private foundation grants.

“We’ve had warning signs and storms where we’ve seen how disruptive it can be to have even a foot or two of flooding,” Granoff said, standing alongside a roadway that sees hundreds of trucks roll through on a daily basis with produce and other goods, just a short walk from the culvert. “One of the great things about this project was that we were gonna prevent it from ever happening. We saw a risk, … we all agreed it was a risk, and we were gonna say we can fix this.”

Now, officials in each city are looking at whether it would be possible to break the project into pieces, but due to Chelsea and Everett each having a high proportion of low-income residents, neither town has the budget to support projects of this scale.

“Municipalities aren’t built to do this kind of huge infrastructure project,” Granoff said. “But even with all that, we were gonna do it. We’ll still have to do it.”

Loved for the features. Trusted for the performance.

Hyundai wheel loaders have the power and performance, not to mention top-notch interiors, accurate onboard weighing system, industry proven drivetrain durability, clear sightlines, and handy tech that make life on the jobsite easier. So you can do more without feeling it. No wonder so many first-time Hyundai users become longtime fans.

Co., a typography and printing operation, trucking outfits, a maker of gauges and valves, a dump and, most recently, a greyhound racing track and betting facility.

Plus, there is currently “urban fill-material” made up of “varying amounts of asphalt, brick and coal/coal ash” buried on the property, the Post noted.

Those details and much more are outlined in the Bridgeport property’s 6,711-page environmental analysis, prepared by Shelton, Conn.-based engineers Tighe & Bond.

Commissioned by the area’s Metropolitan Council of Governments (MetroCOG), a regional planning organization, the massive document lays out what CTSG must do to clean up and/or contain the site’s pollutants.

The recommendations are not unusual for such contaminated locations, commonly known as brownfields, and include “limited”“ excavation of “hot spots” of pollution for off-site disposal, and “capping” the remaining soil “beneath proposed buildings and structures, asphalt-pavement, clean-fill material of sufficient thickness and/or brightly colored demarcation barriers/liners.”

But cleanups of this type can prove complicated, as the developers of Steelpointe learned when they had to similarly address industrial pollutants before breaking ground on an apartment complex at their site, a short distance from the proposed stadium. Currently under construction, that harborfront housing project was delayed by the remediation.

MetroCOG referred the Post’s questions concerning the results of Tighe & Bond’s report to CTSG. In a statement for this article, CTSG did not respond to specific inquiries about the impact on its project timeline and budget, saying only, “The latest environmental assessment ... validates the significant amount of infrastructure work required to develop the stadium and residential aspects of the project.”

The statement confirmed a previous announcement that its minor league soccer team, Connecticut United, will instead “start playing in 2026 in a temporary location that we will announce this fall.”

Swanston has already received some state financial help for the stadium’s site preparation. Last year, a total of $16 million was awarded for the ground remediation effort, with Connecticut officials emphasizing that even if the soccer arena does not move forward, the money will be well-spent in readying the prime acreage for another future redevelopment.

Whether Swanston and CTSG are able to get any more of their requested subsidies remains a key question.

He first went public with his plans in late 2023 and unveiled Connecticut United in January 2024 with an ambitious goal of having the stadium built for 2025’s soccer season.

And while Swanston has boasted that the majority of his $1.1 billion redevelopment vision will be privately financed, his efforts to secure around $127 million from the state have so far proven unsuccessful, with Gov. Ned Lamont in June calling it “a pretty big ask.”

In response, Swanston and other proponents have attempted to place the emphasis not on the stadium but on the project’s housing component at a time when Connecticut desperately needs more housing.

During the legislative session, which concluded in early June, Bridgeport’s representatives to the Connecticut General Assembly in Hartford accomplished two things to further the stadium’s chances.

First, they got language passed that would allow the city to use incremental tax financing to help pay for up to $190 million of the sports venue and infrastructure construction. A portion of any new real estate taxes generated by the project would pay off the debt rather than going directly into Bridgeport’s municipal coffers.

Secondly, the legislature called on the Connecticut departments of Economic and Community Development (DECD) and Revenue Services to conduct an economic assessment of the impact of the proposed stadium by Oct. 1. The belief was that the anticipated positive results of that review could then help better make the case for the $127 million in state aid, the Post reported.

However, with only six weeks left before the deadline, the DECD said in mid-August that it had not begun that study and offered no additional comment.

In response, state Rep. Christopher Rosario said, “I would assume they would start it soon,” and planned to contact the agency. He acknowledged that there was no funding attached to the assessment request. Connecticut Sports Group, in its statement to the Post, alluded to the pending assessment and did not respond to the revelation that the work had yet to begin.

“We look forward to the state completing its review of the economic impact and revenue generation so we can commence with the next stage of this project,” CTSG noted.