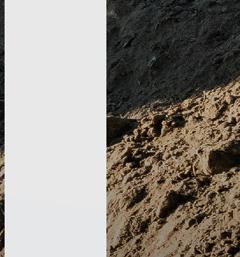

This photo depicts backfilling between the new retaining wall and wingwall on the south end of the new northbound Tower Hill Road Bridge. Crews transitioned from multiple fill types with peastone directly at the backwalls, then reinforced stone backfill under the approach slabs, then pervious fill up to the existing abutment that remains in place.

By Lori Tobias CEG CORRESPONDENT

A $38.5 million project on one of Rhode Island’s most traveled routes to the state’s beaches is wrapping up.

The Tower Hill Road project includes the replacement of the 57-year-old Tower Hill Road Bridge, which carries both southbound and northbound lanes of Tower Hill Road over

Route 138 in North Kingstown, as well as resurfacing of 6.5 mi. of Tower Hill Road — US-1 — from the Route 4 split in North Kingstown to the Oliver Stedman Government Center in South Kingstown.

“The main part of the project was rapid bridge construction,” said Charles St. Martin, spokesman of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT). “Route 1,

Massachusetts’s roadways are at a “critical inflection point” with aging assets, a surge of new funding from Fair Share and an urgency to deliver safer infrastructure faster, according to Jonathan Gulliver, the state Department of Transportation’s highway administrator.

Gulliver spoke recently at a Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce forum on the “State of the Highways & Bridges,” the chamber’s latest meeting in its “Transportation First” series, according to StreetsblogMASS.

Jim Rooney, president and CEO of the Greater Boston

Chamber of Commerce, opened the session with a framing of the Transportation First series by highlighting housing, climate, economic mobility and regional competitiveness. He emphasized that transportation is not a “standalone” issue, but rather the “thread that ties everything else together.”

Gulliver reflected on MassDOT’s focus over the past year, from modernizing project delivery and cutting red tape, to making design safer, faster and more transparent.

Sales Auction Company hosted its annual Fall Industrial Equipment Sale Oct. 10 and 11, 2025, at its headquarters in Windsor Locks, Conn.

The two-day event again proved to be a major draw for contractors, dealers and equipment enthusiasts across New England and beyond.

The sale featured a wide variety of earthmoving and heavy construction equipment, along with fleet vehicles, trucks, trailers, aerial and material handling machinery, plus an assortment of land care and farm equipment. The auction lineup included a large inventory of super-clean, late-model surplus machines from area contractors, rental stores, municipalities, local dealerships and private consignors.

Bidding activity was strong, with nearly 1,900 online bidders and 1,000 onsite bidders — some participating from as far away as Pakistan and Peru. Sales

pe an XP L L erformancerobustdesignan n integrated, innovative mach Power® is the new generatio - L Powwer® 550 X o o heel L iebherr W

s large wheel loa ’s n of Liebherr Powwer® 586 X o

hine concept that sets new st

ndcomfortTheXPower®po

r. re dle more, faster wheel loaders adjusts the p , whatever the applica y,fficiency -split driveline combines r-

splitdrivelinecombines r ower y, ds in terms of r andar eliability ders. Liebherr XPower® is to the job for fuel savings of up r--Efficiency r- The Liebherr-Power ostatic with mechanical dr hydr obust design an performance, r cent - so you hand p to 30 per (LPE) System of the XPower® es maximum ef re rive and ensur nd comfort The XPower® po

Eager to receive a share of the $67.9 million in match-free disaster recovery grants that Vermont will be handing out to flood-ravaged communities, applicants submitted requests by the Sept. 30 deadline totaling $121 million, almost double the amount of available funds.

The Bridge, an independent central Vermont online news service, reported Oct. 23, 2025, that the state’s Community Development Block Grant — Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) applicants include cities, towns, planning commissions, nonprofits and private companies, with Barre City applying for $27.5 million, the largest of the requests.

Managed by the state’s Agency of Commerce and Community Development (ACCD), the funding program is designed to help Vermont communities recover from a devastating series of floods in July 2023.

Most of the money requested by Barre City would go toward repairs and construction for affordable housing, the types of projects expected to get the bulk of the available grant funding.

The capital city of Montpelier submitted four requests, including two for dam removal, totaling $9.6 million. It did not apply for housing-related projects but plans to request several million dollars for

infrastructure improvements related to developing Country Club Road; however, that is contingent on any money left over as well as a second round of funding available this winter, according to The Bridge.

Other local disaster recovery grant applicants included Downstreet Housing, Good Samaritan Haven and at least two private companies: Execusuite LLC, which recently bought the Goddard College campus; and Elliot LLC, which hopes to build affordable apartments near the bottom of Northfield Street in Montpelier.

Most of the funding, totaling $54.3 million, has been designated for Washington County as well as the towns of Johnson and Cambridge, with the rest earmarked for other flood-damaged areas of the state.

State staff members are reviewing the applications and will make recommendations to the Vermont Community Development Board, which meets Nov. 20, according to Nate Formalarie, deputy commissioner of the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development.

“The board will make a final recommendation to Secretary of Commerce Lindsay Kurrle, who has the final say,” he told The Bridge. “I predict there will be an announcement by mid-December.”

Barre City’s applications include $10 million to build 48 affordable apartments at 355 North Main St., and $5.4 million for a 91unit project at Prospect Heights that could include a variety of housing types. The city already has almost $4 million in resources for that project.

Barre also asked for $8 million for Gateway Park, where the funds will be used for a variety of purposes, including elevating some houses and buying out others. In addition, the city requested $2.8 million for a Willey Street bridge upgrade and $856,000 for work on the Harrington Avenue floodplain and debris racks, which Barre already has $1.2 million available.

In addition, its neighboring community, Barre Town, is seeking $2.8 million for the Wildersburg Common ravine bank stabilization; it already has $400,000 for the project.

In Montpelier, city officials asked for $3.5 million to prevent flooding at the city’s wastewater treatment plant by elevating Dog River Road, $2.9 million to replace three culverts on Elm Street that failed in the 2023 flood, $2.3 million to remove the Bailey Dam on Main Street, and $917,000 for the removal of the Pioneer Street dam and 5

Home Farm Way mitigation. A total of $2.3 million has already been obtained for that last project.

Downstreet Housing requested three grants for projects in Barre and Montpelier. The firm asked for a little over $2 million for Barre, which would be added to the $16 million already obtained for the developer’s 31unit Steven’s Branch mixed-income housing project. The new money would be used to buy two parking lots from the city, according to Nicola Anderson, Downstreet’s director of real estate development.

If things go according to plan, construction could begin in the spring of 2026, she said.

The project will feature a mix of studio, one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments designed to meet the diverse needs of the community. With flood mitigation measures incorporated into its construction, the building will provide safe, resilient housing in a central location close to employers, schools and services, The Bridge noted.

Another pair of Downstreet projects in Montpelier are on the application list as well.

One request is for another $300,000 to complete funding for the construction of two energy-efficient duplexes on Heaton Street. see FLOOD page 12

Sometimes a highway construction project does not go with the flow.

After a years-long study, the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) has narrowed down the possible design options for a long-term overhaul of the congested, crash-prone interchange of Interstate 84 and Connecticut Highway 8 in Waterbury, known as the Mixmaster. Both alternatives, the Modern Crossover Interchange and the Naugatuck River Shift, would involve unstacking a series of highway bridges, reducing the number of ramps and opening access to the river, among other changes, according to Jonathan Dean with CTDOT’s Bureau of Engineering and Construction.

A key difference between the two options, which will now go through the environmental review process, is that one calls for the adjacent Naugatuck River to be moved eastward to create space for Conn. 8 to be unstacked and reconstructed on the river’s west bank.

It would not be the first adjustment of the river: CTDOT officials said it was moved once before when the Mixmaster was first built in the 1960s.

Kevin Carifa, the agency’s director of environmental planning, told CT Insider for an Oct. 16 article that moving a river or stream involves building a new channel and redirecting the existing watercourse to the new one. The process, he added, is more common than some may think.

“It is typical for a transportation project to relocate a watercourse,” he said.

One example, Carifa noted, was the realignment of sections

of the Mad River and Beaver Pond Brook as part of a project several years ago to widen and straighten out a stretch of I-84 in Waterbury, not far from the Mixmaster.

“We put this river system into some really crazy configurations,” he said. “That had to be done with a lot of hydraulic review.”

Shifting the Naugatuck River would be a much larger effort, Carifa acknowledged, and CTDOT will not be able to say whether it is the best option until it is vetted through the National Environmental Policy Act process, which is expected to take two to four years.

And exactly how the river could be moved has yet to be determined.

Either the Naugatuck River Shift or Modern Crossover Interchange would cost an estimated $3 billion to $5 billion, in 2022 dollars. Dean said the river shift would be the “slightly more expensive” option.

Actual construction work to rebuild the interchange’s core is not expected to begin for at least a decade, CT Insider learned.

During the environmental permitting process, Connecticut’s transportation agency must show federal and state regulators how it will mitigate impacts to a natural resource like a watercourse, according to Carifa.

For the I-84 widening project in Waterbury, crews used sandbag cofferdams — or barriers — to isolate construction areas and prevent pollution in the river, he said. CTDOT also worked with the state’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) to install features for fish, including “root wads.”

Carifa described root wads as tree trunks that are cut or salvaged from construction sites and placed in a river system.

“And essentially what they do is create habitat for the fish [to] go underneath, to have shading, have an area of refuge [and] to take breaks as they’re meandering up [or down] the streams,” he said.

At another Connecticut project — the replacement of a bridge over Strongs Brook in East Haddam — brook trout were physically moved from the stream.

“Before the contractor started work, (DEEP) came out and they did this technique called ‘electrofishing,’” Carifa said.

“They shock the fish — it’s safe, it doesn’t kill the fish or anything like that. [Then] they collect and … move those fish out of the way so they’re not impacted by the construction.

“The success story afterwards is that the site is definitely seeing some migration of the native brook trout back into the stream,” he said.

The East Haddam project also involved a bypass pump system that took water from an area upstream of the construction site and discharged it downstream.

During the design process, CTDOT will specify which materials a contractor will use when reconstructing a watercourse, Carifa said. Rounded stones, for example, may be preferred over crushed rocks because they look more natural.

The goal is to not just recreate a stream but add improvements, he explained.

For instance, invasive vegetation could be replaced with native plants. An old dam could be removed to allow more fish passage upstream. Boulders could be placed in a stream to help create pools for fish or shelves could be built into the riverbank to provide shade.

“When it comes to relocating a river, we need to prove to the agencies that we’re going to make a betterment,” Carifa said.

ROADS from page 1

The discussion then turned to what Gulliver called the “program disruptors” — the four forces shaping how MassDOT manages projects statewide: safety, congestion, climate and aging infrastructure.

Crash data indicates that Massachusetts ranks as the safest state in the country but still averages roughly one roadway death per day. During the pandemic, that number spiked to nearly 400 deaths a year, underscoring how fragile progress can be.

Gulliver emphasized MassDOT’s shift toward a “safe system” approach, or designing roads that anticipate mistakes rather than punish them. Weekly fatality reviews are now standard in helping the agency respond to patterns more quickly.

He pointed to Worcester’s “peanut” roundabout at Kelley Square, which has reduced crashes dramatically, and new wrong-way ramp detection systems that trigger alerts and send notifications directly back to MassDOT operations.

Climate change also continues to prove itself to be a particularly costly and harmful disruptor. Gulliver cited the recent historic flooding in Leominster — where 10 in. of rain fell in just six hours — as a warning sign of what is still to come.

In addition, he noted that MassDOT is exploring fleet electrification, solar installations over park-and-rides and even pilot projects using low-embodied-carbon concrete to ensure the state is “not just reacting to climate [but] trying to get ahead of it.”

Notably, beyond brief mentions of walking trails like the Emerald Necklace, and a case study regarding encouraging drivers to use the Blue Line and commuter rail during the Sumner Tunnel shutdowns, Gulliver did not mention any concerted efforts to shift more trips to walking, biking and transit — things that will be necessary for the state to meet its climate goals.

Finally, Massachusetts has the oldest bridge inventory in the nation, with 34 closed bridges (up approximately 27 percent in the last decade) while others are propped up by shoring systems or hindered by restricted loads, StreetsblogMASS reported.

The urgency this creates is pushing new programs and expediting funding to speed up repairs, modernize standards and support cities and towns that cannot meet these needs on their own.

Gulliver also delved into the potential of the state’s capital program, noting that the Transportation Finance Commission helped fund critical transportation projects over the last few years.

In this capital program, the value of construction projects is slated to grow from $4.7 billion to $7.9 billion — a 69 percent jump.

When he turned to the positive impact of Massachusetts’s Fair Share Amendment, Gulliver praised how working at the state level for funding has made it much easier and faster to put money into motion on infrastructure projects. By borrowing against future Fair Share revenues, the state has been able to issue $1.85 billion in bonds for transportation work.

He also suggested that the new Fair Share funding could let the state finance and build projects more quickly as well.

“We can be faster at putting some of this money out [and] we don’t have to have all the strings attached that we do with our federal highway money, [which] slows things down,” Gulliver said.

In addition, he talked about an upcoming pilot program that will leverage prefabricated bridges for smaller, closed community bridges across the state, and updating the more than 20,000 culverts across Massachusetts that protect against flooding.

These funding streams also will be used to address unpaved roads, which are particularly salient in the Berkshires, Cape Cod and the North Shore.

This program, set into motion by state Rep. Natalie Blais after adding it to legislation over the last couple years, will provide cities and towns with best practices and funding so that they can ensure the roads are safe and “preserve the character of the roadways.”

Gulliver then addressed how the changing federal funding landscape and escalating construction costs have changed the way Massachusetts implements large infrastructure projects.

MassDOT’s plans to replace the Sagamore and Bourne bridges on Cape Cod are only partially moving forward. The state has financing lined up to build a new Sagamore Bridge, but the Bourne Bridge still needs billions of dollars before it can proceed.

The Allston I-90 project, as previously reported by StreetsblogMASS, is in an even more challenging spot. After losing $335 million due to the federal government’s grant slashing, its design process was put on hold.

To sustain some momentum, though, MassDOT plans to shrink the Allston project’s core, move forward with a study to find opportunities to keep the work in motion, and prioritize smaller projects like Boston’s Cambridge Street Bridge and the Grand Junction Railroad Bridge.

While it will be some time before transportation becomes a federal priority again, Gulliver is hopeful for the return of grant opportunities like the Reconnecting Communities program.

After his presentation, Gulliver, Rooney and Diana Szynal, the president and CEO of the Springfield Regional Chamber, engaged in a moderated discussion and audience questionand-answer session.

The panel acknowledged how Fair Share “unlocks projects that don’t fit neatly into federal buckets,” which helps fund everything from local bridges and intersections to walking trails and climate resiliency.

When looking at diversifying funding streams, Gulliver said Massachusetts is not actively pursuing public-private partnerships, as they are in a “good place for now” due to Fair Share bonding and stable federal formula funds, but may revisit the idea if the need arises. He also noted that United States material costs are expected to rise due to the new tariffs, pushing up steel and concrete prices.

Szynal spoke about the needs of western Massachusetts, including I-90’s Exit 41 in Westfield, the North End Bridge replacement in Springfield, the Longmeadow Curve on I-91 and improvements to Massachusetts Highways 2 and 9.

In closing, Gulliver offered his vision of a bright transportation future for Massachusetts — one “where cars, trains and other modes are fully interconnected and equitable so people in every town can move quickly and efficiently.”

from page 8

The company already has $1.8 million set aside for this project and had hoped to start construction this past summer, but its permits were appealed and the case is now before the Environmental Court, Anderson explained.

The second Montpelier Downstreet project is the conversion of the Washington County Mental Health Services office building on Heaton Street to a structure dedicated to housing. Anderson said that originally this project was aimed at providing “permanent supportive housing” with on-site services, but federal funding for these types of homes has now dried up.

As a result, the project is currently planned to be a mixedincome apartment building similar to other Downstreet properties in Montpelier, she noted. The developer is asking for $5.7 million to go along with $5.9 million in resources it already has for the project.

Another developer, Elliot LLC, has requested $4 million from the Vermont ACCD to build 18 to 28 affordable apartments at the lower end of Northfield Street in Montpelier. The firm’s owner, Jacob Walker, bought two acres of vacant land there a couple of months ago, he told The Bridge.

“This location is near bus service and downtown and is out of the flood plain,” he sad.

If the grant does not come through, Walker still plans to build something, “though it will not be as cost effective,” he said.

Among the other CDBG-DR applicants:

• Good Samaritan Haven, which supplies shelter to homeless individuals and families, has asked for $3.5 million for “emergency shelter relocation and floodway site restoration” in Barre. It already has $565,000 in resources for the project.

• The town of Plainfield wants $9.7 million for its East Village expansion to go along with $1 million in resources already obtained.

• Execusuite LLC, a Lebanon, N.H., redevelopment company, requested $2.2 million to convert the Plainfield Inn on 15 School St. in Plainfield into 12 apartments; it has already lined up $2.4 million for the project.

• Waterbury is seeking $4.3 million for the Randall Meadow mitigation project.

• Waitsfield has asked for $940,000 for its Carroll Road storm water mitigation project.

• Cabot wants $1.3 million for a flood mitigation project on the Winooski River’s North Tributary.

• Hardwick requested $1.5 million for a floodplain restoration project in the town.

• The Central Vermont Regional Planning Commission asked for $2.5 million for emergency communication upgrades for the Capital Region to add to $2.6 million already designated for the work.

In addition to the “implementation” grants listed above, four local applicants asked for planning grants, mostly of smaller sizes: the Central Vermont Regional Planning Commission, Barre City, East Montpelier and Waterbury.

SALES from page 4

Auction Company’s hybrid live-and-online format has continued to expand its international reach while keeping the lively in-person auction atmosphere.

Among the many highlights, a Metso model LT-106 track jaw crusher brought $300,000, a 2019 John Deere 950K crawler dozer sold for $237,500 and a 2024 Cat 315-2D excavator went for $139,000.

The sale also included a charitable component: a 125thanniversary premier box of Mack truck die-cast collectibles sold for $500 to benefit the Shriners Hospital, and a sheet of 10 uncut $5 bills raised $400 for the Wounded Warrior Project. CEG

(All photographs in this article are Copyright 2025 Construction Equipment Guide. All Rights Reserved.)

Many wheel loaders were available; of note, was a 1998 Cat 966F that brought $66,000.

2026, which it is on target to meet.

which sees peak volumes of about 36,000 vehicles per day, is a main thoroughfare through southern Rhode Island for summer tourism. If anyone’s coming from the north and they’re going to Newport or they’re going to our beaches in the region we call South County, it’s a very popular route. The bridge was structurally deficient, and we needed to attend to it. The bridge is critical to the whole southern Rhode Island area, so the consequences of having a closure or weight restrictions would be fairly significant for that part of the state.”

The project was first identified and added to the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) in 2018. Both bridges were rated in fair to poor condition in 2021. The paving of Tower Hill Road was included in the project due to its deteriorated condition. RIDOT chose to have one single project address multiple aspects of the corridor at the same time. It went into design in 2022. Contractor J.R. Vinagro Corp. got the go-ahead to proceed with the job in November 2023 with a scheduled finish of May

The bridge work was structured to get long weekend closures completed before Memorial Day when traffic on the road increases greatly, St. Martin said. Crews reduced Route 1 to one lane for the duration of the work. RIDOT was granted the space within the project limits to allow for the use of Self-Propelled Modular Transports (SPMT).

“This allowed the contractor the ability to build both bridges over Route 138 next to the existing bridges,” said Heidi Gudmundson, RIDOT spokeswoman. “Both bridges were constructed on support towers and then later transferred to the SPMT’s and rolled into place. This method allowed us to demolish and move two bridges into place over two 57-hour extended weekend closures, thus significantly limiting the traffic impacts as compared to conventional construction.”

The new bridge is approximately half the size of the original bridge, now 80 ft. in length compared with the old bridge’s 167-ft. span. The shorter footprint was the result

of a change in the scope of bridge design over the years.

“When the bridge was originally constructed many years ago, there were potential plans to extend the highway farther to the west connecting it to the Interstate,” St. Martin said. “So, some of the widths and the spaces as the bridge were constructed to allow for that future expansion. But the expansion hasn't happened and it’s not going to happen. So long term, it’s less infrastructure for us to maintain, and there is a savings there.”

The RhodeWorks plan to repair roads and bridges was approved by the Rhode Island General Assembly and signed into law by Gov. Gina M. Raimondo on February 11, 2016, according to the RIDOT website. The legislation creates a funding source allowing the transportation department to repair more than 150 structurally deficient bridges and make repairs to another 500 bridges to prevent them from becoming deficient, bringing 90 percent of the state’s bridges into structural sufficiency by 2026.

(All photos courtesy of RIDOT.)

www.equipmenteast.com

61 Silva Lane

Dracut, MA 01826

978-454-3320

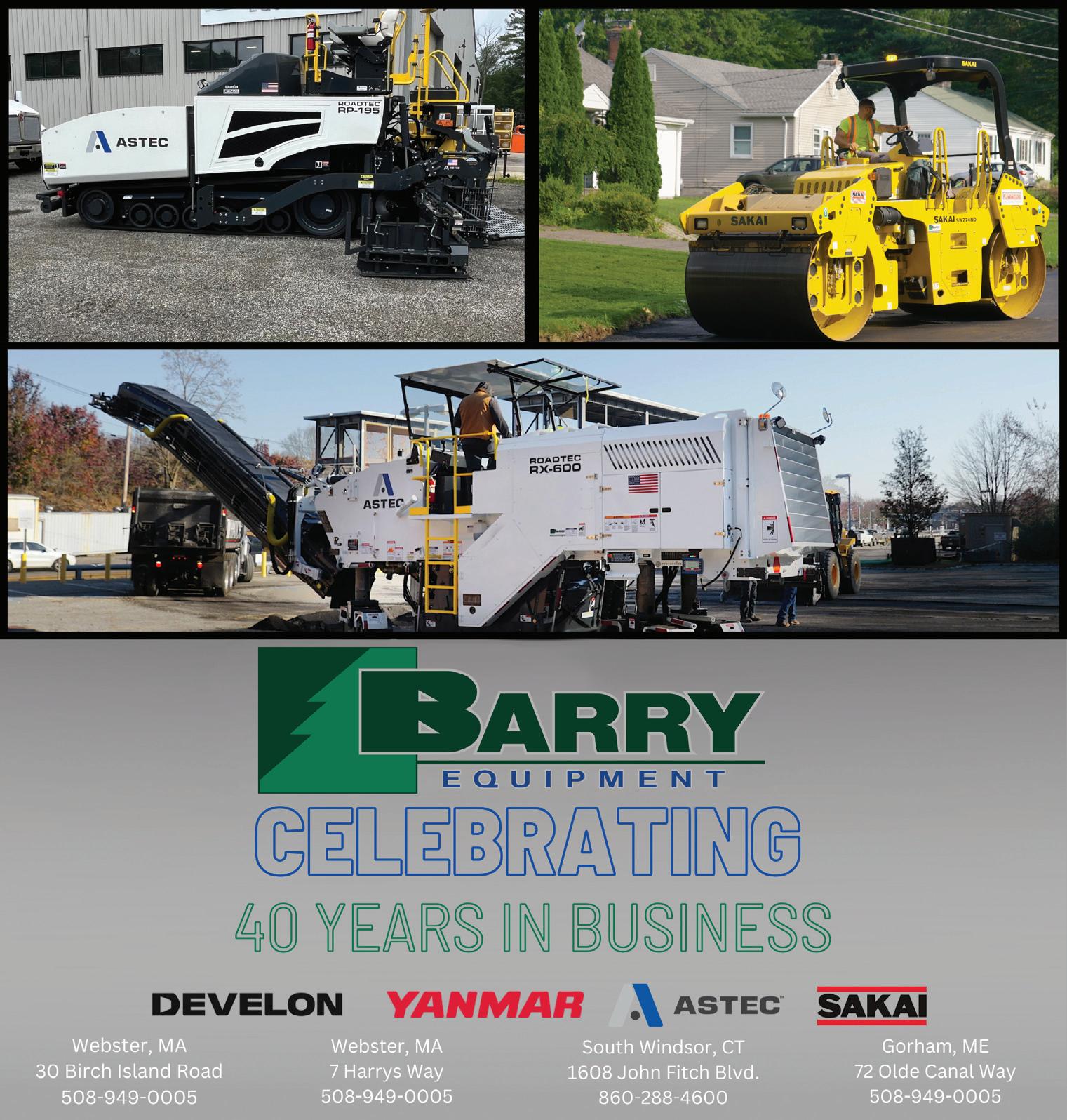

www.barryequipment.com

30 Birch Island Road Webster, MA 01570

508-949-0005

508-949-0005 Equipment East, LLC

196 Manley Street Brockton, MA 02301

508-484-5567

1474 Route 3A Bow, NH 03304

603-410-5540

7 Harry’s Way Webster, MA 01570

508-949-0005

72 Olde Canal Way Gorham, ME 04038

508-949-0005 1608 John Fitch Blvd South Windsor, CT 06074

860-288-4600 Rhode Island

The General Sullivan Bridge in coastal New Hampshire, a 90-year-old steel truss highway span that permanently closed in 2018 after being deemed unsafe for use, will finally be demolished sometime during winter 2025.

The structure stretches 1,585 ft. over Little Bay between the towns of Newington and Dover. Until 1984, the bridge carried traffic along U.S. Highway 4/N.H. 4/Spaulding Turnpike both north and south. It was shuttered to motor vehicles because of its deteriorating condition, the result of its age and the area’s harsh coastal climate.

After that, the General Sullivan Bridge was repurposed as a pedestrian walkway and a popular fishing spot in the area. By 2010, however, specific areas of the structure were closed due to its poor condition before repairs were made in 2011. It continued to serve as a crossing for pedestrians and bicyclists for the next seven years.

A temporary crossing for pedestrians and bicyclists since August 2019 has been provided within the easterly shoulder of the Spaulding Turnpike.

New Hampshire’s Executive Council voted Oct. 15, 2025, to award a $28.4 million contract to Reed & Reed in Woolwich, Maine, to demolish the bridge. Eighty percent of its funding will come from the federal government, while state turnpike toll credits will pay for the remaining 20 percent.

The New Hampshire Department of Transportation (NHDOT) needed three attempts to solicit a contractor for the bridge removal, and the latest effort was the only bid the state received, according to InDepthNH.com, the online news outlet for the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism.

NHDOT Commissioner William Cass told the council that the earlier bids were not awarded due to their exceedingly high cost projections. He feared that if the project went out to bid for a fourth time, contractors would begin to lose faith in the state and its bidding process.

Prior to the vote, an effort by Executive Councilors John Stephen and David Wheeler to table the request failed at the Oct. 15 session.

However, their fellow council members, Joe Kenney and Janet Stevens, said during the meeting that the work needed to be done now and agreed with Cass that the decaying bridge could be a hazard to navigation and the public, as well as a liability, if was left to stand.

Cass also warned the council that any delays in the demolition could result in cost escalations. Given the political climate in Washington, he noted, the state also ran the risk of losing its federal funding if the bridge demolition was tabled.

Stephen countered that much of the $28.4

million could instead be used for other projects in the state’s upcoming 10-year highway plan through 2037, which is $400 million short of the funds needed without an increase in toll fees. He also noted that about $18.5 million in federal funds could be redirected for the bridge’s repair.

Cass insisted that the General Sullivan Bridge’s demolition is one of the state’s top road priorities and must be done.

“It can’t sit there indefinitely,” he said.

Kenney said he was more apt to move the contract along because “ultimately it is the right thing to do.”

After hearing all the arguments for and against the bridge’s removal, the council agreed to completely raze the old and rusting structure.

The General Sullivan Bridge project has been on New Hampshire’s Red List of deficient bridges since 1979, InDepthNH.com reported.

“This project will remove the superstructure of the bridge to address safety concerns for marine users that cross underneath the bridge,” the demolition contract reads.

That superstructure consists of a nine-span Warren truss with a total length of 1,528 ft. It is made up of six deck truss approach spans (three spans on each approach) that flank a three-span partial through-arch truss centered over the federal navigational channel, according to its specifications.

In addition, eight granite-faced concrete piers and two reinforced concrete abutments support the General Sullivan’s superstructure. The bridge originally carried two lanes of vehicular traffic, but in 1984, with the widening of the Spaulding Turnpike and construction of the Northbound Little Bay Bridge, all vehicular traffic was removed from the General Sullivan. It continued to serve as a crossing for pedestrians and bicyclists until its closure in September 2018.

“This project involves complete removal of the superstructure of the General Sullivan Bridge. Select components of the bridge will be salvaged and installed for display as part of the agreed to mitigation,” noted the construction agreement. “At the Dover approach, the superstructure of the existing pedestrian access bridge will be fenced off. At the Newington approach, the approach path will be fenced off at the path junction with Shattuck Way.”

Without a pedestrian/cyclist bridge at the site, enthusiasts have been forced to take a 25mi. detour to travel between Newington and Dover.

A future contract, Cass said, will study alternatives to provide permanent pedestrian access across Little Bay.