By Stuart Chase

By Stuart Chase

A Yoluntary Association Incorporated under the Laxos of the District of Columbia

800 21ST STREET, N. W., WASHINGTON 6, D. C.

NPA is an independent, nonpolitical, nonprofit organization established in 1934. Those who particípate in the activities of NPA believe that the tendency to break up into pressure groups is ene of the most grave, disintegrating forces in our national life. America's number-one problem is that of getting agriculture, business, government, labor, and the professions to work together for common objectives: opportunity, security, rising standards of living, and respect for human rights. Oniy through joint democratic efforts can programs be devised which support and sustain each other in the national interest.

NPA's Standing Committees—the Agriculture, Business, and La bor Committees on National Policy and the Committee on International Policy—and other working committees are assisted by the permanent research staff. Whatever their particular interests, members have in common a fact-finding and socially responsible attitude,

The results of NPA's work will not be a grand solution to all our ills. But the findings, and the process of the work itself, will provide programs for action, planned in the best traditions of a people's functioning democracy.

NPA's publications—whether signed by its Board, its Standing Committees, its staff, or by individuáis—are issued in an effort to pool different knowledges and skills, to narrow areas of controversy, and to broaden areas of agreement.

All reports published by NPA have been examined and authorized for publication by the Executive Committee, under policies laid down by the Board of Trustees. Such action does not imply agreement by NPA Board or Committee members with all that is contained therein, unless such indorsement is specifically set forth.

JoHN Mncra: Assistant Chairman and Executive Secretary

Charles Tyroler 2nd: Assistant Chairman

Virginia D. Parker: Editor of Publications

Stuart

BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

The publication o£ this document as a report o£ the Business Committee is authorized in compliance with a request made in a Business Com mittee resolution o£ July 31.

NPA has long recognized this country's responsihility £or assisting in the efforts o£ other countries to improve their economies and living standards. We have stressed throughout cur studies that such developmental programs require a comhination o£ appropriate private and governmental action. Although Puerto Rico does not quali£y £or Point Four assistance, the experience on that small island in recent years provides an excellent case study o£ ways in which an advanced industrial economy can assist in the economic progress o£ an underdeveloped area.

We are glad to make this report availahle in the helie£ that it will provide guideposts £or types o£ relationships hetween government and busi ness and hetween industrialized and less developed economies.

August 1951

H. Christian Sonne

This study by Stuart Chase was undertaken on the initiative of the Nacional Planning Association under the sponsorship of its Business Committee on Nacional Policy. Funds required for che sCudy were provided by Che Economic Developmenc Administración of che Puerto Rican Governmenc on Che request of che Na cional Planning Association. The conclusions and impressions are encirely Mr. Chase's own.

The Business Commiccee of che Nacional Plan ning Association is happy to presenc chis Report of Progress on "Operación BootsCrap" Co all who are interesCed in evolving business-government relacionships in an increasingly complex world of interdependenc human beings.

Beardsley Ruml

July 1951

The NPA Business Committee on National Poliqf has considered "Operation Bootstrap" in Puerto Rico—Report of Progress, 1951, by Stuart Chase. Without necessarily passing on the details of Mr. Chase's report, the Committee finds this a competent presentation of crucial questions in connection with national and international economic development programs.

The Business Committee believes that industrialization of many underdeveloped areas throughout the ■world is of concern to Americans. Mr. Chase reviews Puerto Rico's efEorts to solve some of its difficulties growing out of underindustrialization and points to lessons which he believes tvill be valuable to government and business leaders in both lo;w-income and highincome societies.

In the hope that this report will contribute to public uriderstanding, we recommend to the NPA Board of Trustees that this document be published as a report of the Business Committee, signed by its author, Mr. Chase.

BEARDSLEY RUML, Chairman New York City

GRAHAM ALDIS Aldis and Company

S. C. ALLYN President, National Cash Register Company

FRANK ALTSCHUL

Chairman of the Board, Gen eral American Investors Com pany

ROBERT F. BLACK President, The White Motor Company

HAROLD BOESCHENSTEIN President, Owens-Corning Fibergias

HARRY A. BULLIS Chairman of the Board, Gen eral Milis, Inc.

ARDE BULOVA Chairman of the Board, Bulova Watch Company

ALEXANDER CALDER

Chairman of the Board and President, Unión Bag and Paper Corporation

DAVID DuVIVIER New York City

ROBERT HELLER President, Rohert Heller & Associates, Inc.

H. M. HORNER President, United Aircraft Cor poration

JAMES ROWLAND LOWE President and Director, Cala veras Land and Timher Cor poration

T. G. MacGOWAN Manager, Marketing Research Department, Firestone Tire and Ruhber Company

AUGUST MAFFRY Vice President, Irving Trust Co.

COLONEL E. W. PALMER President, Kingsport Press, Inc.

DR. CHARLES F. PHILLIPS President, Bates College

C. S. REDDING President, Leeds and Northrup Co.

ELMO ROPER Elmo Roper, Marketing

HARRY J. RUDICK Lord, Day and Lord

H. CHRISTIAN SONNE President, Amsinck, Sonne and Co.

VERNON B. STOUFFER President, Stouffer Corporation

FRANK SURFACE Standard Oil Company (N. J.)

CHARLES J. SYMINGTON Chairman of the Board, Symington-Gould Corporation

ROBERT C. TAIT President, Stromberg-Carlson Co.

J. CARLTON WARD, JR. Farmington, Connecticut

RALPH J. WATKINS Director of Research, Dun & Bradstreet, Inc.

IRWIN D. WOLF Vice President, Kaufmann De partment Stores, Inc.

JOHN ORR YOUNG

John Orr Young and Associates, Inc.

by Stuart Ghase

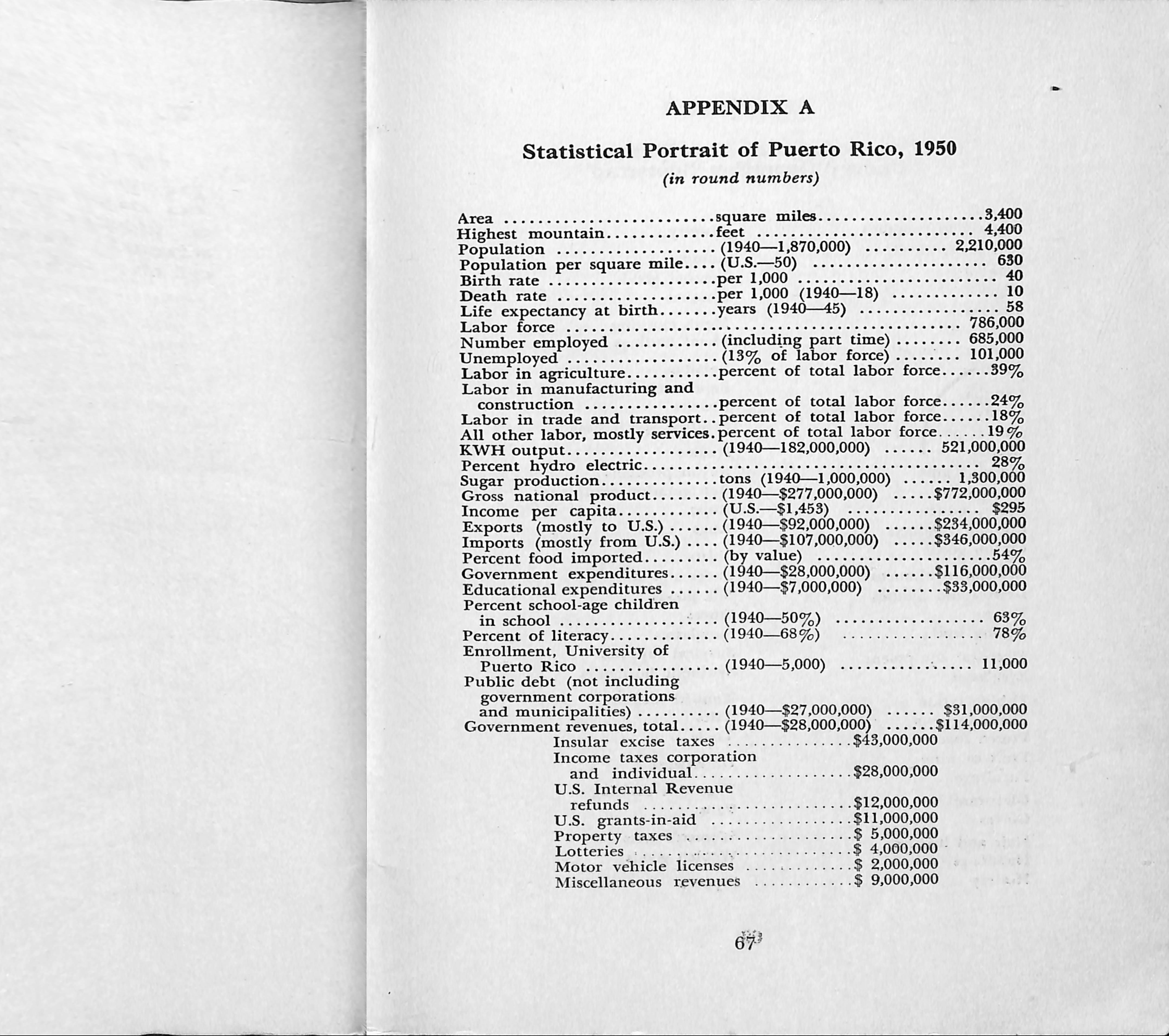

Economists are fond of using Robinson Crusoe and his island to illustrate their theories. Here in Puerto Rico we have a much larger island, about two-thirds the size of Connecticut, with more than two million Crusoes, Mrs. Crusoes, little Crusitos apon it. Instead of an imaginary laboratory for economic reactions, we have an actual one, filled to overflowing with healthy and active consumers, who are also American citizens. Crusoe's island had two inhabitants; Connecticut has fewer than 400 persons to the square mile; Puerto Rico has almost 650.

One can fly around the island in about two hours, following the coastline, with an occasional detour to see a power dam or irrigation project. Here below us lie spread the pieces of the story: San Juan, the capital, with its oíd Spanish forts, its skyscrapers,slums, and vast new housing developments. Across the harbor mouth to the west are fields of sugar cañe and presently the tall white chimneys of sugar milis. Streams wind through the sugar fields, the pineapple

and coconut plantations. All these are on the flat shelf of the coastal plain, with the ocean on one side and the wall of mountains behind. Here and there the mountain wall has spilled giant green cobbles right down to the shore—a curious tumbled formation of limestone hummocks. Along the coast we pass cement plants with their scarred quarries, towns, a salt wbrks. White villages nestle in the bilis beyond, with terraced fields, cofiee plantations, woodlands, motor roads, lakes, and reservoirs.,

As we swing around to follow the south shore, the backbone of mountains looks steeper and less green. Here and there a rocky peak rises above 4,000 feet. The sun bums in a blue sky, and all around, as far as the eye can see, lies the wrinkled, white-flecked ocean. Where the Atlantic joins the Caribbean is anybody's guess.

When Isabella asked Columbus what Puerto Rico looked like, he is said to have crushed a sheet of paper in his hand, then laid it on the royal table. His model was about right^ provided he smoothed it along the coasts, where the sugar fields now are. The crumpled ridges take up more than half the island's area, and little cultivation can be done on their slopes, although some is bravely attempted. The mountains also sharply affect the rainfall. It is estimated that about half the island has soil good enough for crops, but some of this must be irrigated. Our guide points out the course of a new irrigation tunnel which will pierce the mountains to the dry plains of the southwest. Fertilizer is needed, too, for sheet erosión takes a heavy toll.

We come to land's end again in the northeast, and look down on the tropical rain forest of El Junque, where tree ferns grow thirty feet high, under a rainfall of almost 200 inches a year. Snow and ice are of course unknown; Puerto Rican farmers need never worry about frost damage but everybody grows a little apprehensive in September, when hurricanes may come boiling out of the surrounding seas. The last bad one was twenty years ago.

We see no mining operations beyond limestone, clay, and sand. No oil has been found, though there has been some searching. There is little timber worth the cutting, and hardly a dependable supply of firewood. We ask to see reforestation ateas, and are told that they have only recently been started.

From a height of 6,000 feet one can look all over the island, follow every indentation of the coast line, see almost every cultivated field and mountain top. This.is all the land there is; a couple of small islands to the east, and be yond them the Virgins. Even the seas are niggardly in their yield to the commercial fisheries, because of the great depths around Puerto Rico.

The climate remains soft and refreshing throughout the year, and the people grow more healthy and more numerous. Under the pressure of their fertility the island shrinks. They cannot feed themselves from these fields. On the basis of agriculture alone they are doomed with the doom of Malthus. Better yields, diversification, tractors, irrigation projects, any agricultural improvement will soon be overwhelmed by more bables. Puerto Rico must run faster and faster to stay in the same place.

This charming, sun-drenched island appears to have the fastest rate of natural population growth in the worldl The birth rate is about 40 per thousand; the death rate is down to 10, which means a net increase of 30 people per thousand per year. "We have an agricultural birth rate and an in dustrial death rate," says Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. If this continúes for twenty-five years. Puerto Rico will have twice as many people as there are todayl The island of Ceylon comes next, with a rate which will double her popu lation in 26 years; then Japan, doubling in 33 years; the Philippines in 35.

Indeed, the whole planet is suffering from what has been called a "population explosión." Unchecked it could be as disastrous in the long run as the atomic bomb. Like the bomb it is due to science. Western medicine has lowered death rates everywhere by controlling plagues, malaria, typhus, tuberculosis; but it has not been permitted to do much about birth rates. The two rates grow farther apart; and through the widening gap, population surges.

In societies using much mechanical power, birth rates have been falling for a century, pulling down the rate o£ population increase. It goes on increasing, but more slowly. But most of the inhabitants o£ the earth live in handicra£t societies, and it is these which are now exploding, with Puerto Rico leading the detonation. In the last year or two the island's birth rate has lallen a little.^ But the local medical authorities and the U.S. Public Health Service have done such a superlative job en the death rate—bringing it down from 31 in 1899 to less than 10 today—that so £ar the birth-rate decline counts for little.

Primitivo peoples had crude methods for keeping popula tion in line with the food supply, such as the exposure of girl babies and the ceremonial sacrifice of the aged. Plagues and droughts also took their toll. In this day and age there are three possible humane solutions:

1. A shift from agriculture to industry.

2. Birth control clinics and educational campaigns.

3. The emigration of surplus workers.

Puerto Rico is concentrating on the first, which has a double effect. Not only does industrialization raise living standards but, when well under way, statistics show indus-

1 See Population Bulletin for November 1950, published by the late Guy Irving Burch.

trialization is accompanied by a falling birth rate. People's wants are enlarged—a radio, an icebox, a better house, a college education for Jaime—and the number o£ babies declines. The critical income o£ Puerto Rico is $1,500 a year. Above that, the birth rate tends to £all.

And so the £arm people, many o£ them, must come down £rom the hills, and £rom the sugar fields. They must go into £actories, and into the occupations which serve industry. I£ Puerto Rico is to avoid the doom o£ Malthus, it must.do what the United States, Britain, Western Europe, have done, and reduce the proportion o£ £armers in the total o£ gain£ully employed to 30 percent or less. (In the United States the ratio now stands at about 16 percent.) This means mechanization, technology, inanimate energy £rom oil, coal, £alling water; and a large increase in capital investment. It took the West a century to make the transfer. Russia has been struggling with it £or a generation without too much success. Puerto Rico has hardly more than begun.

Why not concéntrate on trying to reduce the birth rate? In one way or another birth-control knowledge should be spread. But at the present time there are cultural, religious, and also technical diíEculties.

Why not step up emigration? This has been tried, but Harlem does not testily to its success in human terms. Selective emigration is indicated until industrialization really takes hold, and it should be carelully planned.

The Malthusian dilemma has been abundantly clear in Puerto Rico £or a generation. At first it was thought that better yields o£ sugar cañe might solve it. By 1940 it was becoming evident that industrialization was the way out. But a delibérate lostering o£ industry requires technicians and administrators o£ a high order, and training takes time. So talented young Puerto Ricans were sent north to get degrees £rom Penn State, M.I.T., Colombia, Harvard.

Rexford Guy Tiigwell, while he was Govemor, energetically promoted the program. He was one of the first to see that no plan can be better tban tbe men wbo administer it, but be ran inte mucb political opposition.

Governor Muñoz today is carrying on tbe industrialization program in tbe ligbt of lessons learned. He bas named it Operation Bootstrap," and so far be bas practically tbe wbole island bebind bim, including tbe business and banking community. Even tbe insignificant radical parties daré not oppose bis main objective of more jobs and bigber living standards. I need an opposition party," tbe Governor said to me. All democracies need at least two strong parties. Wbere sball I find it? Everybody likes our programl" Tbe aim was admirably stated by tbe Governor in bis message to tbe Legislature in February 1950;

Tbe economic goal of Puerto Rico is to increase production as effectively as possible so tbat tbe greater number of Puerto Ricans tbat tbere are each year, will bave fewer days of unemployment, a bigber standard of living, and depend less and less eacb day on aid and privileges wbicb are not tbe result of tbeir own productivo activities.

To go from Washington to San Juan in tbe early part of 1951, as I did, was an enligbtening experience. Not only did tbe weatber cbange from bitter sleet to sunny trade winds, but tbe political climate sbifted from bitter partisan recriminations to a clear, human goal, supported by almost tbe entire community. Nobody was calling anybody a communist sympatbizer, an appeaser, a reckless spender, or a Wall Street monopolist.

But clear as tbe community goal may be it is not easy to attain. It means large amounts of new capital, it means training in new skills, above all, it means cbanging tbe cul tural patterns of four centuries. If Puerto Rico can accomplisb tbis, and offer a lucid record of just bow it is done, all tbe world will come to watcb and benefit.

For the dilemma o£ Puerto Rico is the world's dilemma. If it can be resolved in this land of severely limited natural resources, one is tempted to say that it can be resolved anywhere—in Ceylon, Java, India, China, the Congo. I£ Puerto Rico can find an answer which, with due modification, can be applied to other lotv-income societies, it will have made a major contribution to one o£ the £undamental problems in the world today—the relation o£ £ood supply to population.

The oíd imperialism, in spite o£ the shouts £rom Moscow, is gone £orever. What will replace it £or the necessary international productivity, investment, and trade? Here again. Puerto Rico may have some valuable lessons for the rest o£ US. It provides, indeed, a kind o£ pilot plant for the Point Four Program. Puerto Rico is not technically a Point Four area, because it is an integral part of the United States. It can help, and is helping, to show other nations how to proceed.

In the pages to follow we shall describe briefly Governor Muñoz's "Operation Bootstrap"—how it began, what it has accomplished to date, and its prospects for ultimate success. Finally, we will speculate upon the lessons for other lowincome societies, and for high-income societies too. For Puerto Rico now operates at least three pilot plants, as well as Point Four training, which any modem industrial community might study to advantage:

1. Its honest, devoted, well-educated, and responsible top echelon in government.

2. Its unusual relationship between government and business, where each group respects the other, acknowledges the other's function, and is ready to cooperate with it.

3. Puerto Rico's experience in the techniques o£ overall planning for new utilities and industries, and the system of priorities used. It is not without significance that Dr. Rafael Picó, who heads the Planning Board, is also president of the American Society of Planning Officials.

Industrialization, birth control, emigration, are all needed if Puerto Rico is to break out of its dilemma. But the first is the most important, for in the end it controls the other two.

The visitor from the mainland is usually preparad by rumors he has heard and accounts he has read, for a pretty grim picture of poverty, misery, and despair in Puerto Rico.^ Both my wife and I felt that the slums of the cities and the hovels of the countryside were going to be hard to take, even comparad with West Virginia mining towns, and sharecropper areas in the Deep South.

We found slums and shacks and poverty right enough, but the general impression, compared with our expectation, was not one of misery or despair. For all one afternoon driving along the south and west coasts, I looked carefully at people's feet on the roadside. It is a rara stretch of highway in Puerto Rico which does not have pedestrians upon it, usually taking the ínost appalling chances with the traffic.^ I notad that only small children were barefoot, and by no means all of them. Compared with México, the contrast was striking. Most women and girls wore factory-made cotton dresses in vivid colors. I noticed no sick or crippled people, such as one constantly seas in Egypt, and no beggars.

1 See, for instance, Human Fertility, by Robert C. Cook. 'The accident rate ¡s high in the cities, but modérate in the country, I am toid by the Planning Board.

Puerto Ricans at heme are healthy and comely to look at, some of them strikingly handsome. They walk with their hpds up; they have natural politeness and much human dignity. In Hariem, the same people would probably feel defensive, and this would show in their bearing. At any rate, this is the hest way I can account for the difference which the visitor is sure to notice. It is an arresting differ ence.

Arresting, too, is the contrast with the Virgin Islands, thirty-five minutes by air to the east. The people there seem taller than Puerto Ricans, equally healthy and perhaps even more dignified, but far more leisurely. Few of them seem to take much interest in doing anything about their economic problems, which are considerable.

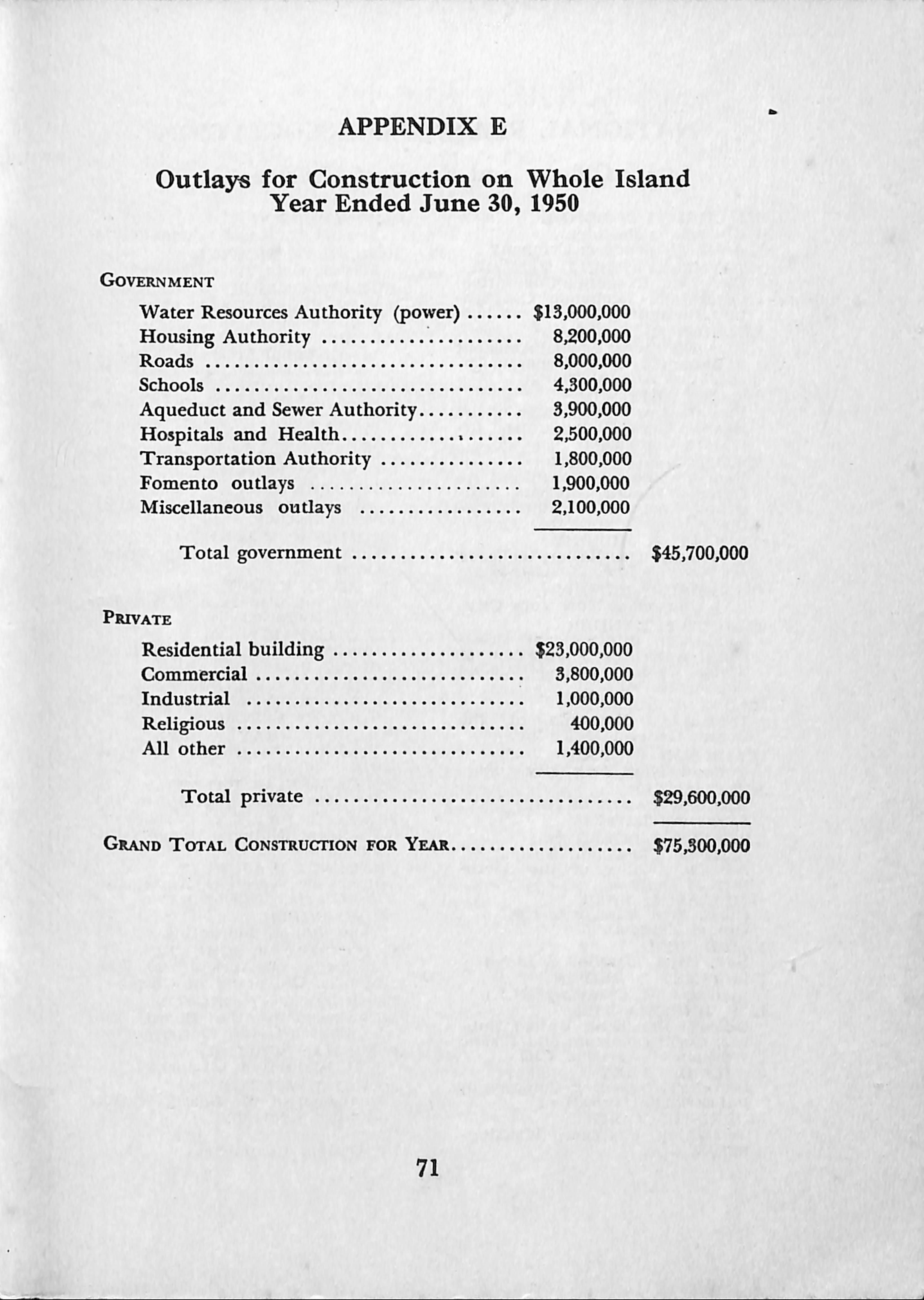

How different in Puerto Ricol Everywhere one goes, even in the high mountains, he sees new enterprise, new construction, new hope. One must constantly detour because of the new roads. Wherever he looks there is a new housing development, a new skyscraper, factory, airfield, concrete baseball park, renovated church, new hospital, school, or market. This rush of physical activity suggests a new determination, the antithesis of degradation and despair. It is not the declining slums that the visitor remembers, had as they still are, hut the new vocational school at Ponce, the new library at the University, the amazing new botéis, the Textron plant, the new hóuses which the government is huilding for the people of the slums.

Indeed, nearly all the stereotypes which people in the North cherish about Puerto Rico tend to dissolve on first hand inspection. They are not a lazy, ill, despairing, mendicant people at all; they do not sing sad, sentimental songs to the accompaniment of the guitar—their music sounds more like excavations in a suhway—and they never go to hullfights, hut to baseball games. Even a Dodger fan would be alarmed at the passion generated hy béisbol!

Puerto Rico is a curious political hybrid. Its people are U.S. citizens, subject to the draft, and entitled to all regular forms of grants-in-aid for public health, roadbuilding, and so on. They use dollars and have no tariffs or trade restrictions in sending goods to the mainland. They do not pay U.S. income taxes, but have an income tax of their own. The excise tax on rum made in Puerto Rico is rebated by the Treasury, on the theory, among others, of "no taxation without representation." It is very helpful to the insular budget.

The President used to appoint the Govemor, but now the island elects its own Governor, and the chief U.S. official remaining is an auditor. There is a right of appeal to the federal courts on the mainland.

Beside the Governor's party, the Partido Popular, there is a Nationalist Party, whose members do not number over 500. Its leaders are now in jail following the attacks on the Governor and President Truman in the fall of 1950. There are Independentistas, a tiny party also favoring a sepárate nation, but by legal methods instead of violence. Communists, a handful, lie low. There is a vigorous ^oup working for statehood, as in Alaska and Hawaii, but it has no great popular following at present.

A new constitution is shortly to be submitted to the voters, which will help to clarify the political structure. The Governor calis it a new social invention, a compact between the mainland and the island, of a structure never before tried. It will be something like the Dominión status of Ganada. It will make Puerto Ricans feel independent and important, while still in the Unión as American citi-

Meanwhile the people turn out and vote in far higher ratios than on the mainland. They elect the Governor, a Senate, a House, and local mayors and officials. The In-

sular Governnient has wide powers over local towns and districts. It nins the public schools, for instance, and all the fire departments—including the ene in Ponce, a historie gem of architecture in red brick, which looks like a giant firecracker at the moment of explodingl

The executive arm includes the Planning Board and various government corporations, fumishing power, water, agricultural research, help to businessmen, as well as the usual cabinet departments of Treasury, Justice, Interior, Health, Education. It includes also the Economic Development Administration, better known as Fomento, which engineers "Operation Bootstrap."

Governor Muñoz and Fomento gave a party to open the one hundredth new industrial plant on the Bootstrap program. Many visitors flew down from the States, and peopie came from all over the island. We attended this ceremony, and it remains one of our most vivid recollections. It dramatizes the efiEort which Puerto Ricans are making to break out of their Malthusian dilemma.

We drove due east from San Juan along the coast, through suburbs and then coconut groves; past the stupendous new airport under construction, dodging the heavy pedestrian traffic which had come out to view the parade. Motorcycle policemen wheeled in and out, their sirens screaming. Puerto Rico has a decibel rate to eoual its birth rate.

On our right, the fields climbed up the mountain sides, and higher up rain squalls obscured the summits. wé were approaching the heavy rainfall area. We passed shacks, villas, sugar cañe waving like corn and planted right up to the back door, tiny ill-stocked shops along the roadside, girls in bright frocks, one naked youngster in a doorwayi cows, goats, an iron bridge crushed in by an overloaded truck.

At the town of Palmer we turned south toward the mountains and soon carne to the new mili of Beacon Textiles Incorporated,® marked by banners, cars, and a record crowd. The mili had been built by the Industrial Development Company. Beacon specified the kind of mili it wanted built, and is buying it on a long-term contract.

The exercises are ábout to begin. The Govemor's wife, officials of both Fomento and the Beacon Company, Congressman Crawford from the States, the Bishop of San Juan, and other dignitaries are gathered bn the broad pórtico, while the Army band roars out a welcome. Hundreds of guests sit in rows below the platform, with school girls in uniform lined up behind.

The building is white cement, bine tile, steel, and glass, very modem and efficient, with a big power installation and panoply of converters. A water main comes charging down from the mountains in a deep ditch between coconut palms. The output is to be rayón cloth and blankets. Spinning and weaving machinery has already been installed, and later we shall observe it in action, tended by Puerto Rican workers.

A sprinkle of raindrops comes down, and the sun burns out again—a regular Caribbean day. The Puerto Rican flag waves beside the Stars and Stripes. We rise as the band plays the national anthem.

Salvador Tió of Fomento opens the meeting, and pre sides with a genial grace which sets the keynote. English is spoken throughout. Next day, at the opening of the new steam plant, Spanish will be spoken throughout. All educated Puerto Ricans know both languages, though it would

® Since this report was written, Beacon Textiles has been bought by Fomento, for original cost plus improvements, and leased to Puerto Rico Rayón Milis o£ Vega Alta, for tbree years witb option to buy witbin ten years. R. E. McDonald, manager of tbe mili, will remain.

be incorrect to say there is no communication problem. Tió introduces Bishop Davis, who makes some appropríate remarks, recites some Latin with a strong Yankee accent, and gives the new undertaking bis official blessing.

Then the manager of the mili, R. E. McDonald, tells us of his early negotiations. He calis Fomento "the most helpful government agency I have ever known .. . we should not be here today without its constant and intelligent aid."

The chairman of Beacon's local board of directors, Jorge Luis Córdova Díaz, a lawyer in San Juan, corroborates McDonald's experience. Although he himself does not happen to belong to the Governor's political party, he has found Fomento an inspired group," excellent to cooperate with, and completely free from political bias in its relations with the business community. Córdova Díaz explains these new plants do not profit because of sweated labor, that an insular wages-and-hours law protects the workers. He hopes that wages will gradually rise. He pays a moving tribute to the 65th Regiment in Korea, composed of Puerto Ricans, and says We are trying to build a community for them to come back to, worthy of their valor." The crowd stands up and roars its applausel

Next comes the head of Fomento, Teodoro Moscoso. His English is perfect, and his vitality great. "Puerto Rico is going to get clean away from subsidies and handouts," he says. "We are building a strong self-supporting economyl We are also conducting a testing ground for political and economic experiments in the atomic age. We have a hard decade ahead of us as we shift from an agricultural society to an industrial one, but we will win throughl" Looking from Mr. Moscoso's earnest face to the solid steel and cement of the new plant which surrounds him, one feels that he will win through. There is already so much solid physical achievement behind his words.

Congressman Crawford, an ultra-conservative Republican in Michigan, warms up in this tropic clime. Long a good friend of Puerto Rico, he does not hesitate to cali "Operation Bootstrap" the "most significant economic operation under the American flag today."

Señora de Muñoz, who speaks for the Govemor, goes immediately to the human level."We are doing this for the people," she says. "This beautiful plant, this concentrated effort, this planning, are all for them ... They will come here to work on Monday- moming, in this light and sunshine, and begin to have new hope; we shall all have new hope. But we Puerto Ricans must be very strong and work very hard." Her voice is warm and compassionate, and one feels that she realizes just how hard it is going to be for some of her fellow citizens to change their age-old customs.

She refers solemnly again to the 65th Regiment, which has obviously become a profoundly moving symbol for the people of the island. Then the chairman announces the death on a Korean battlefield of a young Fomento official, in whose honor the band will now play the Puerto Rican anthem, "La Borinqueña." So we stand through these nostalgic strains, as earlier we heard the Star Spangled Banner, and grieve for the fallen hero.

The whole ceremony is moving. It represents no sham achievement, no synthetic, publicity-inspired unity, but the real thing. Church, state, workers, farmers, professional people, local businessmen, bankers and industrialists from the mainland, even a Republican congressman, are all involved in it. The air is vibrant with it.

Columbus found Puerto Rico covered with a fine tropical forest, the home of a handful of Indians. The Spaniards enslaved the Indians and put them to work digging gold out of stream beds. Some $4 million in ore was shipped to Europe before the beds—and Indians—^were washed out.

Sugar cañe was introduced in 1515, coco palms in 1525, the first manufacturing plant, a sugar mili, in 1548. The forests were slashed away as agriculture expanded. Coffee was brought in from Santo Domingo in 1736, and for many years Puerto Rican coffee was considered by Europeans to be the finest in the world.

Long before the coming of Fomento, the great needlework industry around Mayagüez on the West Coast was flourishing, including both factory and home work. "I have 80 people in my factory and 2,000 sewing for me at home," one employer told me. Other industries included the distillation of rum, cigar making,fumiture, iron work. Indus trial skills were not created de novo by Fomento; many thousands of skilled workers were already on the island.

The idea of accelerating this process, and getting away from dependence on a one-crop sugar culture, had been discussed for years. Incidentally, the United States was primarily responsible for making Puerto Rico a sugar island. While the Spaniards grew and ground cañe, it was not more important than tobáceo and coffee. Says Walter E. Packard, a land expert, after an on-the-spot investiga-

By the end of the first 40 years of United States sovereignty (about 1940), the pressure of people upon resources in Puerto Rico had been ^eatly intensified. The population had doubled. The limited area of good land was more highly concentrated in the hands of a few than it had been under Spanish rule. The number of seasonally employed landless farm laborers had increased greatly. The economy was still predominantly agrarian.

*"The Land Authority in Puerto Rico," Inter-American Economic Affairs, Summer 1948.

Agriculture accounted for 70 percent o£ Insular net income "oríginating in commodity-producing industries." . . . Approximately three-fourths of the agricultura! group were landless farm laborers.

Mr. Packard thus sharpens the outline o£ the dilemma. It is the farm laborer, mostly the wielder o£ the hoe and machete in the sugar fields, working only part o£ the year, who constitutes the heart o£ the problem. His is the "largest single economic group, the poorest and the most prolific in Puerto Rico." He and his £amily exist in unpainted oneand two-room shacks without conveniences o£ any kind. "A large percentage of the farm laborers live as squatters on land that is not theirs. ... Their children crowd into the slums o£ San Juan, Ponce, Arecibo, where the humdrum monotony of isolated living is replaced by the brighter gaiety of city Ufe, even in the slums. The social costs incident to existence of this underprivileged group are incalcul able."

There is no place on the land for all of the many chil dren of these agregados, and they come crowding into the slums; later they may crowd into Harlem. Their low stake in society makes them reckless about the birth rate. It is when people have enough income to plan for a better future, that they become responsible for keeping the birth rate down.

Side by side with the Fomento program of industrialization an agpricultural program has developed. Indeed, some reformers thought that the latter could alone resolve the dilemma. In 1900, shortly after Puerto Rico had been taken over by the United States, Congress passed a law restricting the land which a corporation might hold to 500 acres. The law, however, carried no penalties and was largely disregarded.

An effort to enforce it could have been made by the Attorney-General ... but the authorities weie apparently reluctant to proceed on this basis, both because there was no agreement as to what type of tenure or size of holding should be adopted in the event that the large corporate holdings were to be because there was no existing administrative agency authorized to undertake the job.

By 1940, 41 corporations were operating illegally 249,000 acres of land—an average of 5,000 acres per company. Nevertheless, if sugar is to be grown at all it must be done in units much larger than 500 acres, using modern methods, or costs become prohibitive. So when the agricultural reformers brought about the enforcement of the 500-acre law after 1940, plans had to be ready to adjust the sugar industry to the change.

Luis Muñoz Marín was in the Puerto Rican Senate at the time, and he directed the planning. A "Land Authority" was set up in the form of a govemment corporation, empowered to buy the illegally held land, and to work out new patterns for its cultivation. After some experimenting with farmers' cooperatives, which turned out badly, the Land Authority determined upon three major policies, as follows:

1. Sugar lands were purchased at a fair price from the big estates and converted into what were called "proportional-profit farms" — another social invention. The people of Puerto Rico, through their gov emment, owned the farm. An expert was hired to manage it according to the most up-to-date largescale methods. The workers who had worked on it before continued to do so at their regular wages now under a Mínimum Wage provisión. At the end of the year, profits if earned were shared between

management and workers, after rent had been paid to the government, and reserves set aside.

Mr. Packard cites the case o£ Cambalache, a sugar estáte of some 10,000 acres, with a modern mili grinding 7,000 tons a day. The land cost the government $1,325,000. In 1947, after paying rent and interest, the workers had a profit distribution which amounted to a fifteen percent increase in their wages for the year. Management, too, had a nice bonus.

2. The Land Authority purchased lands to be set aside for new rural villages, where the squatters might have a little cottage and a garden plot to cali their own. To date, almost 200 of these "resettlement villages" have been established, housing more than 25,000 families. They give the farm laborer a social life he has lacked, a small stake in the land, better education, health and sanitation, an alternative to the slums of the cities.

3. The Land Authority also purchased land from the big estates, which, when conditions were right, was divided into family-size farms, and sold to enterprising individual farmers on reasonable terms.

By and large, this three-point program has worked well. It has eased some of the tensión in the agricultural problem, raised yields per acre, improved the status of farm laborees. But it has not made, and cannot make, many more jobs. Indeed, the tendency is toward fewer jobs, as output per man-hour increases.

Ramón Colón Torres, chief of the Insular Department of Agriculture, now has this program in charge. He is a Cornell gradúate, with flashing blue eyes, and enormous enthusiasm for bis job. He told me that one of his major goals is diversification of crops, to get away from too much dependence on sugar, and produce more milk, more coffee, fruit, vegetables, and more land crops as raw material for

Fomento's factories. Only a few of the new plants, he said, use local raaterials, such as coconut fibers and bambeo. "We work closely with Fomento, testing, researching, developing new crops for possible use."

How much of the food that Puerto Ricans eat comes - from the island?" I asked.

In 1940, it was 60 percent by volume, 50 percent by valué, but the ratios are going down. Our goal is to reverse this trend, to grow more at home. The resettlement villages can help here."

If the people of Puerto Rico are to consume more, they must produce more. It is just as simple as that. How can they produce more?

1. By putting the unemployed to work.

2. By making part-time workers full-time workers.

3. By exerting greater individual skill and energy.

4. By bringing in machines, inanimate energy, and managerial skills to help the worker increase his output— which means capital investment.®

The agricultural program can help with the first three, but only Fomento can do a real job with the fourth, the industrialization of the economy.

As a component of the above, we should emphasize the development of local managerial talent. If Puerto Rico is to be saved, her own managers must form the permanent stafiE which carries on over the years.

In 1942 a government corporation was organized, called the Puerto Rican Industrial Development Company,

® From "Labor Cost in the Puerto Rican Economy," Simón Rottenberg, University Press, 1950.

PRIDCO for short, with a capital of $500,000, later increased to $22 million. (The RFC started with $500 million, by way o£ contrast). It was to promote manufacturing on the island, and conduct research into natural resources, into marketing methods and export possibilities. It was empowered to issue bonds, make loans to private businessmen, and if need be, opérate its own industries. Its powers tbus were wide, subject to no regulations by the insular government, except a tborougb annual audit and conformity to the general development program of the govemment's Planning Board. Observe we bave bere in PRIDCO's orig inal cbarter tbe elements of cooperation with private busi ness, and working to a long-term plan, wbicb cbaracterize tbe program today.

Since 1942, Fomento has passed tbrougb two major pbases.

First, tbe agency acquired a cement plant, and built modern faetones to turn out clay products, glass, paperboard, and sboes, all badly needed on tbe island. It operated all five as nationalized industries. Taken as a package, tbey made money, but under analysis it appears tbat tbe cement plant made enougb to more tban cover tbe losses of tbe otber four.

Fomento's second period began immediately after tbe War in 1945 witb a sbift of policy toward building plants for lease or sale to private enterprise, and no new experiments in nationalization. Some large projects were included bere, sucb as tbe $7 million Caribe Hilton Hotel in San Juan, and tbe big Textron plant in Ponce. Private business was invited to assume tbe beadacbes of management and operation.

Fomento s accent now is on making it attractive and easy for prívate enterprísers to do business in Puerto Rico, with various services to aid them, as well as constructing plants to their specifications. The nationalization períod has been Kquidated by the sale of all five government plants to businessmen the shoe plant to Joyce, Inc., of Pasadena; the cement, clay, glass, and paperboard plants to the local Ferré brothers, who already have an iron works and a cement plsnt in Ponce, and much managerial experience.

Among the policies pursued in the present períod are these: ®

Tax exemption for all new enterprises until 1960 —scaling down toward the end. Puerto Ricans pay a local income tax on corporations and individuals. Tax-exempt enterprises do not pay this, and are also free of local property taxes. No U.S. federal income tax is collected in Puerto Rico.

Technical research and assistance provided without cost by Fomento, which offers to recruit the necessary workers and give them a series of modern scientific tests IQ, aptitude, physical condition, and so on.

The retaining by Fomento of a competent publicity agency to let U.S. businessmen and bankers hear about Puerto Rico.

A special campaign to improve the quality and publicize the virtues of Puerto Rican rum.

"On July I, 1950, PRIDCO was merged into the Economic Development Adminístration. ^

A special program to encourage tourists, o£ which the construction of the Caribe Hilton is the most conspicuous result to date. Other hotels are being built or enlarged, beach resorts and deep sea sport fishing developed, roads improved, mountain re sorts opened, casinos encouraged.

The establishing o£ offices in the States £or negotiations with business prospects, many o£ which have sent officials down to Puerto Rico to look over the situation on the spot.

In the next chapter we will appraise the results o£ "Operation Bootstrap" to date, and try to look a little way into the £uture.

, Fomento has been chiefly responsible for 106 new plants, employing 15,000 workers, with a total pubhc and prívate investment of|33 millíon. At capacity operation, these plants are expected to produce about $65 imihon worth of goods a year, most of which will be sent to expected to create at least 10,000 new jobs in the service trades—truck drivers telephone operators, airplane personnel, mail clerks, répair crews, and the rest. ^

Assuming an addition, then, of 25,000 new jobs all toid how does this compare with the number of new workers coming on the Job market during the same period? In such a comparison, "Operation Bootstrap" is still far behind. It has been in forcé for about three years, during which time it is estimated that 60,000 new workers have come on the market looking for jobs. But, according to Harvey S. Perloff about half of these hopefuls have emígrated-or more preSS emigration 'has absorbed about half of the increase in the labor forcé...." This cuts the 60,000 to 30,000 job seekers remaining in Puerto Rico, and is not too far out of line with 25,000 new jobs, direct and indirect, due to "Operation Bootstrap." ^

1 As of July 1951, Fomento records show 121 plantó establíshed directly, and assístance gíven, princípally tax exemption, to 41 more.

The necessity for emigration during the transition period is very clear. A bilí has passed the legislatura to help emigrants going to the mainland, and especially to steer them away from New York. Venezuela is reported to be a good possibility for emigration, as its man-land ratio is abnormally low.

The town of Vega Baja used to live almost exclusively on income from sugar—canefields and mili. It did not live well. Mayor Angel Sandín persuaded Fomento and the Grane China Corporation to lócate their new plant in the town. A recent study shows that the net income of the community has increased almost $800,000 a year, which is a lot of money in Puerto Rico. The factory pays $500,000 to its workers, employing 500 steadily, and 200 more in the busy season. It buys local supplies amounting to $150,000, food for the cafetería, and so on. This new flood of purchasing power, moreover, reverses the emotional climate of the community,from resignation to ambition.

Some skeptics do not think much of Fomento's hopes for the tourist trade. Hamilton Wright, Jr., does not think much of the skeptics. "I have helped put many resorts across," he said to me,"and none of them can beat Puerto Rico. Look at those mountains! Look at the colors in that

Some o£ these have gene out of business due to bad management,labor dif&culties, raw material shortages. No figures are available to show the exact number of employees now, or at capacity operation. Plans are developing under Dr. Richard Behrendt, a capable social scientist, to conduct a perpetual audit of new plants, the workers, and investment involved, together with reasons for success or failure. Nothing could be more helpful to all concerned.

seal Feel the temperature of that water!"

Certainly the Caribe Hilton Hotel venture is beginning to pay out. Every ene of its 300 rooms bas a balcony looking out to sea, and tourists and visiting businessmen keep tbem ful!, wbile tbe Casino, tbe restaurants, tennis courts, pool, and cabanas are beavily patronized by local citizens. Tbe hotel operated at a profit in its first year, 1950, and in 1951 profits are running 60 percent bigber.^ Tbe Hilton Company and Fomento sbare tbe profits. My wife and I encountered several tourists beaded for otber resorts in tbe Caribbean, wbo later returned to tbe Caribe Hilton as tbe most comfortable resort of all. Tbe Hilton management is optimistic, but it is still early to tell wbetber anotber Riviera is in tbe making. Deep sea fisbing for sportsmen sbould be developed and expanded. Nigbt club entertainment sbould not. "Give tbem sometbing different from wbat tbey get at borne," is tbe idea of tbe Hilton manage ment.

An impressive beginning bas been made towards tbe industrialization of Puerto Rico. Factories, botéis, and trade will continué to expand, if for no otber reason tban tbat some are now tbere. Tbe island is an integral part of tbe United States, witbout serious currency or tariff barriers, and tbere is little danger now tbat it will relapse into a one-crop sugar culture. Witbout careful steering, bowever, industrialization could be an ugly process. Tbe early days of tbe factory system in England, and New England for tbat matter, are npt a picture one cares to recall.

2 Profits, first six months of 1950 j 97,000 First six months of 1951 154,000

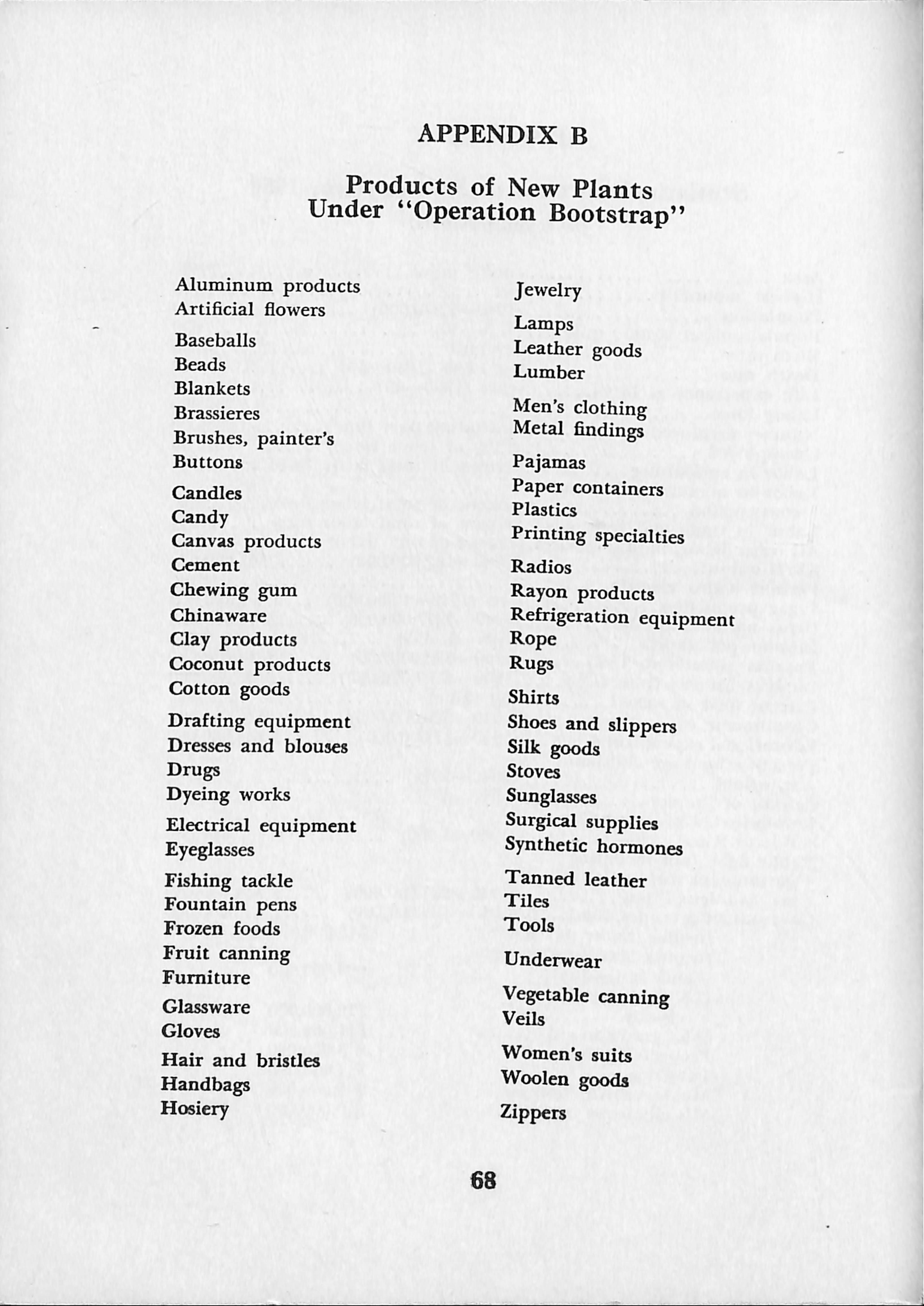

As one runs over the list of new plants (see Appendix B) certain questions arise. Many of the enterprises are small, requiring little capital equipment, engaged in producing novelties for which the market is capricious. Their roots do not run deep into the economy. Such industries are in evitable, indeed welcome, in the experimental stage, but for an enduring economy the more solid type of industry is needed—such plants as Puerto Rico Rayón, Textron, the cement works—with a relatively high investment per worker, high productivity, and potentially high wages. While Fomento deliberately discourages industries that seek permanent low wages, the very considerable wage difEerential between the mainland and Puerto Rico naturally attracts concems looking for low-cost hand labor. The mínimum wage in the needlework industry, for instance, is 18 cents an hour. In the long run, low-wage industries mean a low standard of living which would defeat the Govemor's goal.

More "core industries" are needed, too. This is Fomento's term for plants which furnish vital services to other indus tries, and so save shipment back to the mainland for processing. They include machine shops, tool and die establishments, printing and dyeing shops for textile goods, and the like.

When a young Puerto Rican wants to get married, a frequent practice is to borrow a few hundred dollars from his prospectivo father-in-law and open a retail store. Everywhere one goes on the island one sees tiny, inefficient, unsanitary shops, sliding into bankruptcy. Costs of distribu tion are too high even on the mainland, despite the A & P, Macy's, and supermarkets. In Puerto Rico they are fantastic. Fomento is well aware of this leakage, but is now too busy with new factories to do much about it. Sooner or later it must be tackled seriously. Retail stores in the Hawaiian islands average twice the size of Puerto Rican

stores. Says Perloff:

The large number of workers'employed in wholesale and retail trade is a reflection of the extreme ineiSdency of distribution in the island, as well as of the need on the part of many Puerto Ricans to find some source of income and employment no matter how unrewarding. Xiny shops, some no larger than oversized packing crates, are stretched along highways and mushroom in towns and villages, often several to a block. Xhe total inventory is frequently no more extensive than a well-stocked pantry in a U.S. middle-class home. Xhe prices of retail products, which are uniformly high, reflect the ineSiciency of distribution rather than the type of competitivo situation which might normally be expected....

I talked to many businessmen, both local and conti nental, and most of their answers fell into a regular pattern. It went like this:

Question: What do you think of the Fomento program?

Answer: Excellent; the only thing to be done.

Question: Will it succeed, in your judgment?

Answer: Xhere is too much momentum now to stop it. Xake a look around you; see all the new construction. Where else in the world is the skyline changing so fast?

Everybody I talked to was concerned about the population problem, and almost nobody felt that industrialization was the solé answer to it. Some advocated birth control some emigration; most people advocated both.

3 Puerto Rico's Economic Future, p. 65. 83,000 out of a total labor forcé of 687,000 in 1948.

The outlook is clouded by world history. Will the huge new defense outlays on the mainland cut oS essential ma taríais needed on the island, both for the skyline, and for manufacturing? A rug manufacturar told me that i£ a real wool shortage developed, he would have to cióse down and throw soma 400 people out of work. (Incidentally, he was enthusiastic about the speed and intelligence with which his people learned their work.)

On the other hand. Puerto Rican industries may receive soma substantial defense orders—several have already been placed for Army clothing. Will mobilization deflect tourists from Europa and the Pacific to the Caribbean, as happened in World War II? Will Army, Navy, and Air Forcé bases in Puerto Rico be expanded substantially? Soma ex pansión is already taking place.

Meanwhile the young administrators in Fomento, in the Planning Board, the Development Bank, and elsewhere in government,continua their overtures to mainland capital and enterprise, as well as to local investors. They have allowed me to look over their files of prospects.

For the fiscal year andad June 30, 1951, the legislatura appropriated $2 million to be used by Fomento in the construction of industrial facilities for new businesses. These include one million for a cigar factory to be operated by the Consolidated Cigar Company; $284,000 for an extensión of the Textron plant to make tricot cloth; $250,000 for a factory to make children's shoes; $150,000 for a rug plant, and so on. (Sea Appendix C.)

For the fiscal year ending June 30, 1952, the legislatura has appropriated $8.7 million for helping new industries. These include textiles, jute bags, men's clothing, prínting and dyeing of cloth (a core industry), tuna fish canning, shoes, perfumes.

Beyond this, some $15 million of prospective investment is in a preliminary stage of negotiation, coveríng an oil refinery, a radio assembly plant, and faetones to make pharmaceuticals, paints, tools, lamps, wall board, wire springs, handbags, hosiery, and biscuits.

The total under construction and negotiation is cióse to $25 million for the next two years. This represents only govemment investment, buildings constructed, and loans. "In some cases, private capital woiild invest an amount equal to, or larger than, our investment," Fomento reports. This means that we are considering projects which would add more than $50 million of industrial investment to our economy."

What one considers promising, and what one actually receives, do not always coincide. But certainly the prospects for more industry, and even for a higher-investmentper-worker type of industry, are encouraging. Compared with the mainland, or even with such a country as Vene zuela at the present time, the actual and prospective invest ment is small. Compared with the past history of Puerto Rico it is very considerable.

Is the investment sufficient really to shift the base from agriculture to industry? It is too early to be sure, but to me it looks better than a fighting chance.

I was talking to a public relations man in San Juan who promotes a Puerto Rican product. He said that two salesmen on their Caribbean rounds had called on him the week before, one after another. They both asked him: "Whom do I see? What do I pay?"

"I told the boys whom to see, but that you didn't pay anything. They nearly fell dead! ... Why, they said, we know Latin América; it's where we do most of our business. Of course we pay somebody.... Not here, I said, you don t pay here. Later they came back and admitted it was true, and what the hell was the reason? ... That s a tough question when you get right down to it. W^hat is the reason patriotism, pride, mainland habits coming in ^what is it?

He did not know, ñor do I, though I have a theory or two to develop presently. But almost nobody disputes the fact. In the window of a downtown shop near the Forta leza, among samples of native handicraft, baskets, pottery, and the like, is displayed a coconut carved into a likeness of the Governor, with rumpled hair and hard-bitten inustache. Under it a neatly printed card reads in Spanish: "Not for sale at any price."

By way of contrast, the London Times reports on the recent troubles in Irán: "There is a widespread gulf between Government and people. Nepotism is rife. No tra-

dition of disinterested public service exists. Corruption is widespread."

No program such as that of Fomento, or Point Four or the Marshall Plan, even if drafted by archangels, is wórth the ink to pnnt it unless competent and trustworthy managers are ready to administer it. The managers are always human beings. Not only must they be honest and devoted they must be intelligent, efficient, and trained for their new tasks—a combination to put quite a strain on any human bemg. A workable plan for leadership is just as important as the project itself.

Long before Fomento, ideas for economic and social reform were stirring in Puerto Rico. In the middie thirties for instance, the legislature voted to establish birth-controí dimes all over the island—which were later abandoned under pressure. Agricultural reforms were widely advocated, and in this connection R. Menéndez Ramos, Deán of the University's College of Agriculture at Mayagüez arranged to send talented students to Penn State and other American colleges for training in technology and leader ship. Muñoz Marín and Rexford Tugwell, as government officials, followed a similar course. They picked the young administrators, gave them a visión of public service, and sent them to universities and technical schools on the ínainland for training.

Some of the young government leaders who come from oíd and wealthy families could be far more secure and affluent in the family business. Said one of them: "My brother is making all the money; but I am having all the fun." It is more than fun. It may be twelve or fourteen hours a day, with as many crises as a Madison Avenue advertising agency—except that the crises are real, not synthetic.

Beardsley Ruml told the Committee for Economic Development in 1949 that he had inquired with particular

care about graft and favoritism in Puerto Rico. He said that "the testimony is unanimous that neither squeeze ñor hite has been found. ... The higher ofi&cials o£ the gov-' ernment are well aware that the program would be destroyed by corruption, or by even the suspicion of corruption."

Two years later I can only confinn Mr. Ruml's report. I heard of a case or two where local officials had been apprehended, as when a suburban mayor tried to divert some funds to house a lady friend, and was promptly fired by the insular government. I heard no case, ñor rumor, ñor whisper, against the top echelon in government. I did however hear its integrity praised in unexpected quarters. The president of a large bank, with branches all over the island, told me that he would trust the leaders of Fomento, "anywhere with anything." I tried to imagine the head of the First National on the mainland saying that he would trust the Administration at Washington anywhere, with anythingl

Luis Ferré, the leading local industrialist, assured me the government group was absolutely honest, and their overall program praiseworthy. The owner of a large needlework concern in Mayagüez, María Luisa Arcelay, said the same. The president of the Polytechnic Institute at San Germán and members of bis faculty with whom I talked reported a government beyond suspicion.

When the program started in 1942 Esteban Bird was with a prívate bank, and like nearly all the businessmen and bankers he knew, opposed the program. Six years later he was working for it as a high executive of the Government's Development Bank. I interviewed him there. "Today," he said, "these men have become convinced of the integrity of the administration and the soundness of the Fomento idea. I've been here two years now, and no political pressure of any kind has ever been put on this

office." ^ The office, be it noted, is the RFC of Puerto Rico, a bank to help enterprisers who cannot get loans from regular banking sources because of the risks involved. To date, the Development Bank has paid its way and earned substantial profits.

The young men in govemment are organized on five major fronts, cooperating not only to serve their community, but with the hope of transforming it.

1. Political—The Governor supplies ideas and inspiration, and helps to keep the occupational groups— farmers, workers, businessmen—in line behind the program. This is an indispensable function, for the ablest group of technicians would fail in this situation without an astute political hand to lead them.

2. Planning Board—Dr. Picó and his staff perform another essential function. They figure out the ma jor variables as the economy swings from agriculture to industry, and try to guard against duplication, waste, and blind-alley developments. They yisualize the total situation, and establish priorities in new investment and construction. Shall it be a hospital or a hall park? Nothing substantial can be built, either by prívate capital or by Fomento, with out a license from the Board.

3. Fomento Under Moscoso this is the powerhouse, the line organization which takes ideas from the Governor, the Planning Board, its own staff, or wherever else ideas can be found, and translates them into cement, steel, machinery, and skilled working forcé.

1 Mr. Bird has recently retumed to prívate banking, though not because of friction.

The Agriculture Department—This agency, under Ramón Colón Torres, is responsible for the improvement of land use and crop yields, and for the rural reforms and resettlement villages described earlier. Agriculture is still a most important economic activity, and must be closely geared to the industrial program, in respect to both labor supply and raw materials.

Finance and the Budget—This important function needs clear-headed direction. The relatively low interest rate for money borrowed in the States, which is so cardinal to the program, depends in turn upon the integrity, and the strong balance sheet position, of the Water Resources Authority, the Power Authority, and other govemmental units. Puerto Rico must maintain its high credit rating in mainland money markets. The Budget has not been out of balance for many years, and the public debt stands at only $31 million—against annual government revenues of more than $100 million. (See Appendix A.)

All the major government agencies, including the Water Resources Authority, Housing Authority, and other utilities, try to conduct some research as an aid to policy making. So does the University of Puerto Rico, under Chancellor Jaime Benítez, and this would be the logical place for much of it.

Here on the island is one of the most interesting social and economic experiments in the world, a veritable gold mine for social science research. Instead of concentrating on víhat Jeremy Bentham thought about the island of Britain a hundred years ago, economics classes might concén trate on the industrialization of the island of Puerto Rico

in 1951. A whole new pattern of economic relationships is obviously in the making. It deserves intensive study, and also a wide-ranging, imaginative view, which sees into the futura as well as into the past, to give the transformation a theoretical framework.

Changas are occurring in months, which in the Britain of the last century required decades. There the worker was defenseless against the onrush of the factory system; here he has the govemment solidly hehind him. In Britain business interests fought social legislation with unparalleled bittemess, while on this island today, businessmen often cooperate in such programs. In Britain, too, big land owners fought the coming of factorías, but not in Puerto Rico.

What an opportunity to develop fresh new economic and social theory! The University has started on this course, but I think it could do a good deal more. How is "Operation Bootstrap progressing; what dangers are developing; what cultural changas and tensions are occurring; how does industrialization affect people? Here is a chance for a "San Juan School" of political economy to go down in history with the Manchester School.

Motivation

Where did all these young leaders—I would guess their average age at 40—acquire their motivation? Whence cama all this energy, idealism, and integrity which so puzzled the two salesmen?

One hypothesis is that the energy infiltrated from the mainland, as Puerto Rico was gradually made an integral part of the United States, with its people U.S. citizens. They caught the Yankee get up and go.

Again a whole generation of young Puerto Ricans were born U.S. citizens. They studied economics at the Uni versity under Professor Cordero during the 1930's, when

new ideas were in the air, including the Chardón plan for reforming the island economy. They went on to get degrees on the mainland, worked very hard, and returned ready to reform and to build. New Dealers talked about one-third o£ a nation forgotten on the mainland; in Puerto Rico it was nearer nine-tenths—which made the challenge all the greater.

But perhaps the outstanding motivation came from Governor Muñoz. He had a hand in the Chardón plan; he was President of the Senate when the reform movement was mounting, with a strong pólitical party already behind him. For years he had gone up the mountains and down the valleys, talking to the farmers, building a mass movement. He gave the young men a place in that movement and a way to focus their energy. Also he had spent some years in the States, worked on American newspapers, learned how mainlanders opérate.

When President Roosevelt was leading the crusade against unemployment and depression, young men came to help him from all the universities, and idealism ran high. San Juan in 1951 reminded me in some ways of Washing ton in 1935. But on the mainland World War II brought prosperity and full employment back with a rush. The for gotten man was presently drawing down $60 a week in shipyards and aircraft factories. Economic idealism faded out. In Puerto Rico, on the contrary, the Malthusian dilemma continued unabated, and economic idealism and economic solutions were still badly needed.

In the city of Ponce, cióse by the plaza, is a fine, dignified farmacia with high ceilings, mahogany panelling, and rows of multicolored bottles. The shop and the large build ing which houses it belong to the Moscoso family, which has been in the wholesale and retail drug business for fifty

years or more. Teodoro Moscoso was brought up to carry on the business, and was sent to the States to study pharmacy. A secure and not too strenuous life lay before him, supported by the approval of family and friends.

Then, like many another young man, he caught a visión. He took a leave o£ absence from the family business, went to work for the Housing Authority, and began doing something about the slums of Ponce, in which unemployed agricultural workers from the hills had gathered.

Presently he initiated a scheme to make the limited funds reach a lot more slum dwellers. Instead of buying land and building new houses, he installed a "utility unit" for every four slum shacks, consisting of four showers, washtubs, and sanitary toilets, together with a hydrant for puré drinking water. He opened up roads so that services could readily get in and out of the area. This lifted the worst curse of slum living—foul water and terrible sanitation. People could now wash their clothes and themselves. Things did not look much better architecturally, but the sickness rate went down. Soon people began to plant flowers, paint their shacks, spruce up.

A man with such enterprise should have a wider field. Moscoso was invited by the Governor to come to the capital and join Fomento. He has been there ever since, an inspiring forcé as well as a competent administrator. One sees him all over town, as busy as a corporation vice president, horn-rimmed spectacles, briefcase, and all. A distinguished engineer from the mainland said to me: "Ted is not only good at stopping things which shouldn't be done, he is even better at figuring ways to do things which people say can't be done. He's positive electricity."

The contrast with the government in Washington today is so pronounced that it tends to cloud one's critical faculties. It is a refreshing novelty to find leaders of a com-

munity all going in the same general dirección, with che people (save for a handful of fanatics) right behind them. One encounters plenty of criticism of the government, of Fomento, the Planning Board—though never in respect to integrity, or in respect to the goal and the over-all program.

One careful student, for example, thinks that Fomento should have retained the five government plants for another year or two. By that time, he believes they would all have been out of the red, and would have fetched a better price. It is true that losses were declining. The same careful stu dent feels that not enough use is made of new findings in social science.

Said one man high in the Administración: "Yes, we are doing pretty well, I'll admit, but we are not as young as we were, and we have no second team."

"Isn't somebody trying to develop a second team?" I asked.

"No. Furthermore, we have worked out no techniques to hold US together over the really tough places which are surely coming. We need more research by the University into human relations. We need an opposition party, too. Sometimos I wonder if we aren't growing stale, and a bit smug."

"Maybe," I suggested, "yon should have a Congressional investigación, U. S. Senate model."

"Heaven forbid," he said, "and besides we have no tele visión."

I met several highly placed officials who were skeptical about the tax eliminación features of"Operación Bootstrap." They say it gives industry a false base, and they predice an upheaval in 1960 when the law runs out. Here is an other excellent research project—to figure probabilities on chis dour predicción, and develop a new tax plan which will maintain business incentives.

Puerto Rico is not only ín an industrial boom; she is half in and half out o£ the mañana tradition of Latin América. Her executives move faster than in México, but not so fast as in Manhattan. I found that it takes appreciably longer to make contacts and get information than it does at home. The climate, of course, is a factor, but less, I think, than the culture. There is far more red tape than there needs to be. I heard a case where an application for tax exemption took three weeks, which should have been cleared in three hours.

A New England concern, ready to open a branch plant in Puerto Rico, was held up for more than a month, first by the Burean of the Budget, then by the Planning Board. Officials of Fomento complain that they have "responsibility without authority," while other arms of the govemment which clear Fomento's new plants have "authority without responsibility." This is a difficulty due apparently not to personalities, but to structure. There are experts in administration in the States who could analyze the situation and design a better structure, where authority goes with responsibility. Maybe the answer is weekly policy meetings of top ofiicials, with Muñoz in the chair; maybe some system of rotation; maybe practice in the new technique of role-playing, to put oneself in the other fellow's place.

Some critics believe that Fomento gives too much attention to mainland enterprisers and not enough to local talent. There are good men and women in local business enterprise—iron works, textiles, commercial fisheries, food manufacturing, distilling—and in the long run, of course, it is they who will chiefly have to manage and be responsible for an industrialized island.

I am reminded of two hotels in this connection, the Caribe Hilton in San Juan and the Virgin Isle in St. Thomas. The former, except for a few key positions, is staffed by native help; the latter by a shipload of employees

from New York. Some say the service in the Virgin Isle is better than in the Caribe Hilton—now. But a year or two from now, this advantage will probably be reversed. It takes longer to train the local staff, but it will be a permanent asset when trained, operating in its own culture and its own country.

In this transition period, a great deal of capital, talent, special skills must be drawn from the mainland. Ultimately, Puerto Rico must roll its own.

No Utopia, surely. But where else in the jangled world of 1951 will one find a community so united, so well and truly led? Devotion, honesty, competence—even these are not enough to account for what is actually being done.

The American engineer I mentioned earlier put his finger on the other essential ingredient. "They haven't any ideological principies," he said, "or if they have, they don't show. Their only commitment, as far as I can see, is the well-being of the whole island. They are not tied up in either Marxian or free-enterprise strait jackets. They can think without looking it up in the book; they are flexible and mentally free to think out what needs to be done. If business can meet a need, fine. But if business cannot, then let the government do it, or a cooperativo or a nonprofit association. The main thing is to get it done."

*In other words," I said, "they have achieved what you might cali ideological immunity; not theories but results count."

"That's about it," he said.

Which brings us to the relations between government men and businessmen in Puerto Rico, relations pretty unusual in North América today.

If you are thinking of establishing a branch plant in Puerto Rico, here are the services which Fomento is prepared to fumish:

1. Round up, screen, test, and train your prospective workers.

2. Plan your transportation problems—ocean, highway, and air.

3. Arrange to connect you with all public utilities— power, water, telephone, etc.

4. Help with housing, schools, hospitals for your work ers; also for any managers and technicians brought down from the mainland.

5. Relieve you of all taxes until 1960.

6. Fumish economic research for your production and marketing problems, also chemical research if you need it.

7. And perhaps most important of all; assume that you are a friend, rather than a suspicious character with profiteering designs on the people.

The testimony we have already seen shows that the busi ness community, both local and continental, has accepted Fomento, often with enthusiasm. I have heard American businessmen at breakfast, after their night flight by clipper from New York, damn Washington and all its works with

theír grapefruit, and praise Fomento with their scrambled eggs and coffee. Their whole ideological mechanism goes suddenly into reverse.

Thís is a strange but cheerful shift of gears. It means, does it not, that neither the structure o£ modern business, ñor that of govemment, necessarily has to prevent friendly cooperation £or common goals? I am afraid it means, too, that Puerto Rico is farther ahead in such a relation than the mainland.

The Puerto Rican situation is the more surprising because the Governor's political party, when it rose to power a decade ago, was frankly socialistic. No good socialist is disposed to trust businessmen, any more than good businessmen trust socialists. The early reforms were along socialist lines. Govemment corporations were sét up in both agriculture and industry, and plans £or nationalization were widely advocated. These plans, however, contemplated buying out owners at a £air price, never expropriation such as communists advócate. There was no agitation £or the "dictatorship o£ the proletariat," only £or more schools, more literacy, more democracy.

At the same time, i£ certain essential utilities, industries, and services were to function on the island, the govemment, as we have noted, obviously had to be the enterpriser. For one thing, it could get capital cheaply; for another, the risk was too great for prívate business to assume. Venture capi tal and management had to come from the govemment if they were to come at all.

So the cement plant was acquired, and the clay, glass, shoe, and paper plants were built, all to be operated by Fomento. In agriculture also, various projects were organized and put under govemment operation. A broad program in democratic socialism was launched.

Before long, however, the program began to get into difficulties. Some of the agricultural corporations were badly managed and began to show losses. The cement plant did well, but the other four factories started in the red, which was to be expected, and stayed there, which was not.

Part of the trouble was due to the labor unions. Other countries experimenting with government ownership have had similar troubles, and the relationship is a thorny one. A socialist government is supposed to be on labor's side, but to stay in oflBce it must represent all major groups. Government by a single special interest is intolerable for the long run. One answer is to get out of the role of a large employer of industrial labor, and that Fomento did.

So the initial experiments in government ownership were modified, first by the policy of building plants for prívate businessmen to lease, and then by tax abatement, and all the other services listed above.

Also, Fomento tried to encourage local capital to invest in the new industries. A half million in Textron stock has been sold on the island, for instance. Moscoso told me of a plumber who put $200 in a rope factory. This would have been impossible a few years ago, he said, because the plumber would have been afraid of such an unusual venture; furthermore he probably would not have had the $200. One of the críticisms of government policy is that more of this is needed, and especially more local managers.

So far as I can find out, this shift toward cooperation with business was primarily the result of experience, some of it reasonably bitter. No theories were involved. The Governor and his top command were flexible enough to move over under the pressure of facts, provided that their funda mental goal was advanced. They cared more for the wellbeing of Puerto Rico than they did for dogma, and they took the whole staff along with them as they changed. Some went willingly, some went haltingly, perhaps some are still

afraid o£ "wicked capitalists" and profiteers. Mostly the staff is entertaining the wicked capitalists; taking them around to factory sites, and showing them how they can make more profits.

"The legitimate object of government," said Lincoln, "is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, hut cannot do for themselves." Once this idea is grasped, economic ideologies fall by the wayside. In Sweden we cali such an approach the "middle way." A better designation might be "a new dimensión." The economy of Puerto Rico is a" new dimensión economy, using all available functions—business, government, labor, nonprofit organizations—to further the welfare of the whole community. From another point of view, the new dimen sión is delibérate promotion of managerial talent to do what the community wants done.