votre référence en formation des adultes

votre référence en formation des adultes

In this issue, we wanted to explore the theme of the common good, a notion that encompasses what is desired for the development and well-being of a community, with a set of values, common aims and ideals that guide collective actions and whose benefits are to be shared by all members of this community.

For this exploration, we called on the expertise of the Institut de coopération pour l’éducation des adultes (ICÉA). By reading the articles of its adult education researcher, Émilie Tremblay, you’ll learn more about the common good and the commons.

The reason we wanted to bring you an issue on the common good has a lot to do with the links between this notion and lifelong learning. Several UNESCO publications in recent years have focused on the notion of the common good, not only in terms of the right to education, but also in terms of a collective commitment to education as a common good of humanity.

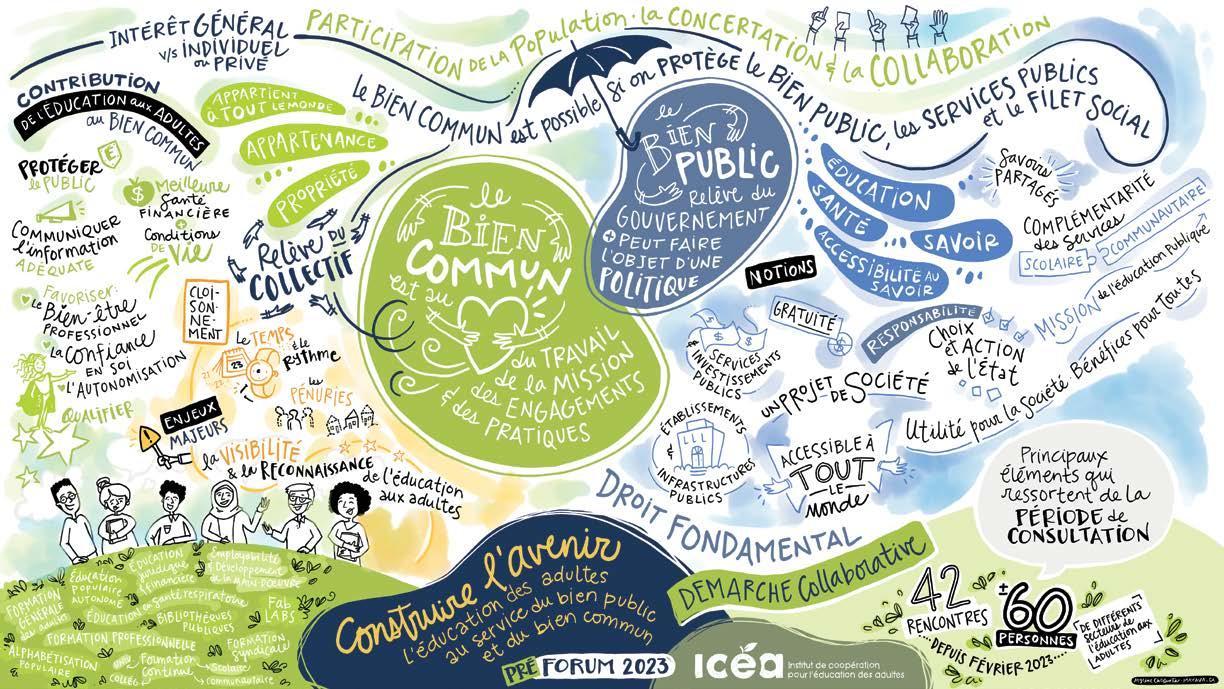

This was also the theme of the last ICÉA Forum in June 2023. Émilie Tremblay recounts how participants at this forum called “Construire l’avenir : l’éducation des adultes au service du bien public et du bien commun” collectively reflected on ways to foster and strengthen the common good in adult education.

But this thinking isn’t limited to Canada. Have you heard of UNESCO’s Global Network of Learning Cities? Its aim is to promote equity and social inclusion, economic development and sustainable development through lifelong learning for the citizens of participating cities. According to the World Bank, 70% of the world’s population will be urban by 2050, so cities have an important role to play in finding solutions to their common challenges and, more broadly, to the future of humanity. You’ll be able to find out how three of the Network’s cities elsewhere in the world are finding innovative or traditional ways to encourage their citizens of all ages to learn and keep on learning, as they grapple with their own particular challenges.

Finally, we looked at the links between community literacy and the common good. Isabelle Coutant, Adult Education Research and Development Agent at ICÉA, makes the links in her articles between community literacy, the common good and Francophone minority communities, and illustrates with concrete examples how literacy-building activities within communities also contribute to the common good.

An issue, then, whose mission is to challenge the utilitarian model that limits education to a mere individual socio-economic investment. We hope you’ll find it an inspiring and optimistic read.

We would like to thank Émilie Tremblay and Isabelle Coutant of ICÉA for their essential contribution to this issue.

Photo: Mélanie ProvencherThis article includes excerpts from one of her articles published in 2023 in the magazine Apprendre + Agir.1

THE NOTION OF THE COMMON GOOD IS BECOMING INCREASINGLY POPULAR IN PUBLIC DEBATE, WHETHER IN RELATION TO EDUCATION, HEALTH, THE ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, OR THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, DIGITAL RESOURCES AND KNOWLEDGE. THIS NOTION IS ALSO USED IN A WIDE RANGE OF DISCIPLINES (ECONOMICS, LAW, ENVIRONMENT, PHILOSOPHY, POLITICAL SCIENCE, EDUCATION, ETC.).

The award of the Nobel Prize in Economics to Elinor Ostrom in 2009 for her work on the commons, and in particular on economic governance, 2 has given new visibility to the notion of common goods and commons. Similarly, ecological crises such as climate change and biodiversity loss, as well as interest in the knowledge or information commons, 3 have contributed to a renewed interest in the work and theory of the commons.4

1 To read this article go to: https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/les-notions-de-bien-public-et-de-bien-commun-en-education-des-adultes-une-introduction/

2 Ostrom, E. (2010). Gouvernance des biens communs. Pour une nouvelle approche des ressources naturelles. Bruxelles, De Boeck (original Edition Cambridge University Press, 1990).

3 To learn more see: Le Crosnier, H. (2018). « Une introduction aux communs de la connaissance », tic&société 12(1) : 13-41. https://journals.openedition.org/ticetsociete/2481#

4 To learn more, go to: Buchs, A. C. Baron, G. Froger et A. Peneranda (2019). « Communs (im)matériels : enjeux épistémologiques, institutionnels et politiques », Développement durable et territoires 10(1). https://journals.openedition.org/developpementdurable/13701#; Dardot P. et C. Laval (2014). Commun: essai sur la révolution au XXIe siècle Paris, La Découverte.

In recent years, several UNESCO publications have focused on the notion of the commons, notably “Rethinking education: Towards a global common good.5 More recently, this notion is also at the heart of the report by the International Commission on the Futures of Education: “Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education”.6 This new social contract for education is based on two principles: the right to education, and a commitment to education as a public project and as a common good for humanity.

A number of notions related to that of the commons are used, sometimes synonymously, sometimes complementarily or differently. These include common goods, commons, global commons, common resources and common property. The same applies to the notion of public good. Here are a few examples: public services, global public goods, general interests, fundamental rights, collective goods, essential goods, shared goods, etc.

Firstly, a public service is not necessarily a public good, and vice versa. A public service can be provided by the state or by a public authority (municipality, public institution, etc.), but it can also be provided by a private company. The notion of public service is based on the idea that certain activities or services are essential and strategic, and must be accessible to all. Depending on the context, country, city or community, the definition of public service changes, and this influences our vision of the role played by the private sector.

According to certain economic theories, a public good can be considered to be a non-rival or non-excludable good.7 This means that it is a good whose consumption by one person must not prevent its consumption by another (“non-rivalry of consumption”), and that no one can be excluded from consuming it (“non-exclusion of use”). Goods meeting these two criteria, whether local, national or even global - so-called global public goods - would benefit everyone and would not be subject to market competition. This economic approach to public goods has been criticized.

In other publications, when we speak of public good, we often refer to two notions: general interest or public utility, and undifferentiated access to this good for everyone. The public good also refers to state action, and in particular to the public policies that are put in place.

The common good (used in the singular) refers to what is desired for the development and well-being of a community, political group or society. This notion shares similarities with that of public good.

The notion of the common good thus refers to a set of values, shared goals and ideals guiding collective action, the benefits of which would be shared by all members of a community, group or society.

According to UNESCO, the common good must be defined “according to the diversity of contexts and conceptions of well-being and common life”.8 Depending on cultural contexts,

Public goods are considered to be more directly linked to public and state policy. The term public often leads to a common misunderstanding that ‘public goods’ are goods provided by the public (UNESCO, 2015, p. 86).

5 UNESCO (2015). Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good. Paris, UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232555/PDF/232555eng.pdf.multi

⁶ UNESCO (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. Paris, UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707/PDF/379707eng.pdf.multi

7 Boudes, P. et C. Darrot (2016). « Biens publics : construction économique et registres sociaux », Revue de la régulation (19). https://journals.openedition.org/regulation/11805#

⁸ UNESCO (2015). Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good. Paris, UNESCO. Paris, UNESCO, p. 87. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232555/PDF/232555eng.pdf.multi

What is meant by the common good can only be defined with regard to the diversity of contexts and conceptions of well-being and common life. Diverse communities will therefore have different understandings of the specific context of the common good. Given the diverse cultural interpretations of what constitutes a common good, public policy needs to recognize and nurture this diversity of contexts, worldviews and knowledge systems, while respecting fundamental rights, if it is not to undermine human well-being (UNESCO, 2015, p. 87).

places and times, the common good will therefore not be understood and defined in the same way.

Alongside this notion of common good (in the singular) understood as what is desired for the community or society, as shared aims, values or ideals, there are also resources that are considered to be common goods or commons. A common good can be tangible (water, air, forest, seed, etc.) or intangible (knowledge, data, software, genetic code, peace, education, etc.).

To define common goods, it is common to refer to the notion of belonging or ownership. According to Proulx (2004), “A good is common when, because of the general interest, it belongs to everyone”, i.e. to the community as a whole rather than to an individual or an organization.9 It cannot be a “personal or parochial good”. (UNESCO, 2015, p. 87)

The question of governance is also a criterion used to define the commons. For a good to be a common good, there should be democratic and collaborative management of a resource by a community, shared governance following choices made by this community. There’s a major difference between this and public goods.

Notion of common goods therefore refers not only to resources, but also to the “community in action” that produces, creates, manages, provides access to and preserves resources, and to the “rules of governance that this community sets for itself”.10 This vision does not meet with unanimous approval. Verhaegen mentions that we need to go beyond this triad (resources, community and rules of governance).11

The commons Ambrosi refers to are referred to by others as the “commons”.12 The notion of the commons refers to a set of initiatives, collective social practices, citizen practices, social systems and collective actions designed to produce, protect, value or manage goods or resources in common, to create or develop the commons. The commons are “spaces for negotiation” and “for the expression of society”.13

The commons movement is plural. It brings together a diversity of people and organizations, at local, national and international levels - the “commoners” - who are involved in thinking about, building and putting into practice the commons, which can be environmental commons, cultural commons, knowledge commons, educational commons, and so on.

⁹ Proulx, J.-P. (2004). « L’éducation, un bien commun très particulier », Éthique publique 6(1). https://journals.openedition.org/ethiquepublique/2053#

10 Ambrosi, A. (2012). Le bien commun est sur toutes les lèvres. Remix The Commons. https://wiki.remixthecommons.org/index.php/Le_bien_commun_est_sur_toutes_les_l%C3%A8vres

11 Verhaegen, É. (2018). “From Common goods to the common”, Les Politiques Sociales 1-2(1), p. 19-33. https://www.cairn-int.info/article.php?ID_ARTICLE=E_LPS_181_0019

12 To learn more, see: Bollier, D. et Helfrich, S. (2022). Le pouvoir subversif des communs, Paris, Éditions Charles Léopold Mayer (collective translation from English coordinated by Olivier Petitjean).

13 Le Crosnier, H. (2011). « Une bonne nouvelle pour la théorie des biens communs », Vacarme (56), p. 92-94. https://doi.org/10.3917/vaca.056.0092

We speak of a «common good» whenever a community of people is motivated by the same desire to take charge of a resource that it inherits or creates, and self-organizes in a democratic, convivial and responsible way to ensure access, use and sustainability in the general interest and with a concern for the «good life» together and the good life of future generations (Ambrosi, 2012).

In short, the notions of public good(s), common good(s) and common(s) are comparable in some respects and distinct in others. To quote Rita Locatelli, it seems interesting to think of the notions of public good and common good as “a kind of continuum, the aim of which is to put in place democratic political institutions that enable citizens to have a greater say

in the decisions that affect their well-being”.14 From this point of view, in adult education and training, this would mean putting learners at the centre, involving them in the decisionmaking processes that affect them and in the co-construction of public policies.

Figure 2: The Triad of the Commons Material or immaterial

14 Locatelli, R. (2018). “Education as a public and common good: Reframing the governance of education in a changing context”: Education Research and Foresight Working Papers (22). Paris, UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261614/PDF/261614eng.pdf.multi

THE NOTIONS OF THE COMMON GOOD AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ARE LINKED. FOR SOME PEOPLE, SOCIAL JUSTICE IS NECESSARY TO PROMOTE THE COMMON GOOD.

Social justice involves reducing inequalities, combating various forms of discrimination and recognizing their causes, as well as promoting and guaranteeing human rights. Social justice therefore aims to ensure equal rights and fairness for all. Working for greater social justice means wanting all people to be able to participate fully in society and have access to a decent life.

Equity is synonymous with justice, meaning that people, whatever their identity, are treated fairly.1

Philosopher John Rawls wrote the foundational work of the theory on social justice. 2 Since then, a great deal has been written about social justice. According to the Ontario Ministry of Education, social justice is based “on the belief that each individual and group within a given society has a right to equal opportunity, civil liberties, and full participation in the social, educational, economic, institutional, and moral freedoms and responsibilities of that society. 3

According to the United Nations, social justice is “based on equal rights for all peoples and the possibility for all human beings without discrimination to benefit from economic and social progress throughout the world. Promoting social justice is not simply a matter of increasing income and creating jobs. It’s also about workers’ rights, dignity and freedom of expression, as well as economic, social and political autonomy”.4

There are several types or concepts of social justice: distributive social justice, redistributive or restorative social justice and commutative social justice. Today, authors are making links between social justice and climate justice.

Fraser, N. (2011). Qu’est-ce que la justice sociale? Reconnaissance et redistribution. La Découverte.

Vargas, C. (2017). Lifelong learning from a social justice perspective. Education Research and Foresight Working Papers, 21, 1-15. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ ark:/48223/pf0000250027

1 https://edi.uqam.ca/lexique/equite-diversite-inclusion/

2 Rawls, J. (1987), Théorie de la justice. Paris, Seuil, (éd. originale, 1971).

3 l’Éducation (2014). Equity and Inclusive Education in Ontario Schools. Guidelines for Policy Development and Implementation, p. 99, Ministry of Education: https://files.ontario.ca/edu-equity-inclusive-education-guidelines-policy-2014-en-2022-01-13.pdf

4 https://www.un.org/fr/observances/social-justice-day

When we say that education is a public good, we mean that the state and public authorities have a key role to play. The state has a number of responsibilities, including regulation, management, policy and program development, financing and the provision of educational services.

Rita Locatelli (2018)1 identifies three facets of the principle of education as a public good:

• as a vision;

• as policy focus;

• as a principle of governance.

She explains: “Whether understood as a humanist vision, a political priority or a principle of governance, the principle of education as a public good refers to the definition and protection of society’s collective interests, and to the central responsibility of the state in this regard”. 2

In the field of adult education and training, governments (provincial or national) play a key role, particularly when it comes to basic skills training. 3 Of course, they are far from the only players involved. The adult education and training ecosystem involves numerous organizations from the public, community, associative and private sectors. It also includes many different forms of education (formal, non-formal, informal), as well as a multitude of different approaches and philosophies.

To claim that education is a public good also implies that it benefits society as a whole. Education does indeed have a positive impact on society as a whole, whether it’s on the health of the population or on the reduction of crime and socio-economic inequalities. Adult education also plays an important role in society. It promotes personal fulfillment and autonomy, social integration and active participation in society (economic, community and political activities), as well as job integration and mobility. Furthermore, the literacy skills that people acquire have impacts on employment, remuneration, civic participation, health and self-confidence, among others.4 Developing these skills helps reduce the individual and social costs associated with low literacy levels.

1 Locatelli, R. (2018). “Education as a public and common good: reframing the governance of education in a changing context”, Education, research and foresight: working papers (22). Paris, UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261614

2 Ibid, p. 3.

3 https://www.tcu.gov.on.ca/eng/eopg/programs/lbs.html

4 Proulx, J.-P. (2004). « L’éducation, un bien commun très particulier », Éthique publique 6(1). https://journals.openedition.org/ethiquepublique/2053#

To reaffirm a humanistic/integrated vision of education in contrast to a more utilitarian approach

To preserve the public interest and societal/collective development in contrast to an individualistic perspective

To reaffirm the role of the State as the guarantor/ custodian/main duty-bearer of education in light of the greater involvement of non-state actors at all levels of the education endeavour

Proulx writes that education can be considered a common good, because “it is essential to the maintenance and development of society as a whole, both as a civil society and as a political community”.5 The notion of the educational commons also emphasizes the goals of education as a collective societal enterprise, rather than as an individual investment as defended by human capital theory.

To be considered a common good or a common, education must be the subject of a collective, evolving and democratically elaborated construction. For this reason, a number of educational sectors and facilities are more likely to be considered public goods, since they are under the responsibility of the state, which makes decisions and manages them. However, this does not prevent their actions from contributing to the common good.

Making education a common good requires transformations to foster greater cooperation and participation by citizens and communities, in order to build education systems that are more democratic, more inclusive and better adapted to the specificities and realities of each community (Locatelli, 2018). This democratization also requires the consultation and participation of citizens and communities in the development and implementation of public policies.

The notion of education as a ‘common good’ reaffirms the collective dimension of education as a shared social endeavour (shared responsibility and commitment to solidarity (UNESCO, 2015, p.78).

• THE CREATION AND SHARING OF OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES (OER);

• THE USE OF CREATIVE COMMONS LICENCES;

• USE OF FREE SOFTWARE;

• SETTING UP WORKSHOPS AND SPACES FOR CREATION, SHARING AND COLLABORATION;

• THE DEVELOPMENT OF LEARNING COMMUNITIES;

• PEER-TO-PEER KNOWLEDGE SHARING;

• THE USE OF WIKIPEDIA IN TEACHING;

• MASSIVE ONLINE COURSES (MOOCS, WHICH ARE FREE, NON-CREDIT COURSES OPEN TO ALL).

Here are just a few specific examples of commons developed for and by the adult education community.

The Mahara platform, an open source application, is one example.6 It’s a complete digital portfolio that includes social networking features to enable the creation of learning communities. There are communities for general adult education and occupational training. The open-source software (Passages), is a transdisciplinary portfolio, which enables the recognition of prior learning and skills, as well as the validation of previous experience (experiential and extracurricular learning). 7

Alongside the information and digital commons, there are other types of commons. Community-based education is one of them. It lies at the heart of the practices of many organizations and institutions, and is a genuine tool for social transformation. The community-based literacy centres (Centres d’éducation populaire de Montréal) created by citizens to take action in their communities, and managed collectively are another example of the commons. A few years ago, the role of Montreal’s six community-based literacy centres, and the specificity of their approach and educational practices, led Bourret and Ouellet (2006) to present them as a common good.8 Among the commons, we can also include community-based literacy groups.9 Community-based literacy involves taking collective responsibility for the environment with a

6 https://mahara.org/

7 https://epassages.ca/en/

8 Bourret, G. et C. Ouellet. (2006). Six centres d’éducation populaire de

view to social transformation. Groups are autonomous and democratically managed.

The education and adult training commons highlight new ways of learning, training and being trained, working and sharing knowledge and skills. Of course, people and organizations were already working on “sharing” or “making it common” long before we started talking about educational commons. Communitybased education comes to mind.

Finally, in a context of EdTech,10 development, particularly in the private sector, the commons are an important alternative. The free software community is a good example, as is the FabLabs network. Contributory and collaborative approaches are at the heart of the commons. Commons promote the sharing of knowledge, skills, expertise, tools and resources. They also encourage participation, collaboration and involvement of citizens or learners in various projects and decision-making processes, as well as collective and community management. It is also important that these voices be heard, taken into account and integrated into the development of public policies in education in general, and in adult education and training in particular.

un bien commun. Rapport de recherche. Alliance des centres d’éducation populaire de Montréal - Inter Cep et Service aux collectivités, UQAM, p. 65

9 https://rgpaq.qc.ca/

10 “The EdTech sector encompasses all organizations with technological know-how or innovative technological tools dedicated to knowledge transmission, learning, knowledge exchange as well as pedagogical assistance”. To learn more visit: https://www.edteq.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/etude-du-secteur-des-technologies-numeriques-educatives.pdf

OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES (OER) ARE LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH MATERIALS IN ANY FORMAT AND MEDIUM THAT RESIDE IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN OR ARE UNDER COPYRIGHT THAT HAVE BEEN RELEASED UNDER AN OPEN LICENCE, THAT PERMIT NO-COST ACCESS, RE-USE, REPURPOSE, ADAPTATION AND REDISTRIBUTION BY OTHERS. (UNESCO, 2019).

On June 7 and 8, 2023, the Institut de coopération pour l’éducation des adultes (ICÉA) organized the forum Construire l’avenir : l’éducation des adultes au service du bien public et du bien commun (Building the Future: Adult Education for the Public and Common Good). The goal of the forum was to encourage participants to reflect collectively on ways of promoting and strengthening the common good in adult education, and to prioritize where to focus in order to meet the major challenges in adult education, with the ultimate aim of contributing to the public good and the common good.

For several years now, the ICÉA has been documenting certain transformations in the world of adult education, notably the increase and diversification in adult education, training and learning venues. In the private sector, for example, the supply of online training has grown considerably, particularly with the proliferation of digital learning platforms such as Coursera, Udemy, Udacity and EdX. Some authors even use the term “platforming of learning” to describe this transformation in the organization of the production and promotion of educational content. Private players are not the only ones to occupy this niche, but they are especially prevalent.

At the same time, society’s demands for knowledge and skills in various spheres of daily life are omnipresent (digital, health, finance, environment and sustainable development, etc.). In this fast-changing educational environment, adult education and training, a component of lifelong learning, is more necessary than ever, especially as we face various crises, particularly ecological ones, which, if they are to be overcome, require that citizens develop new skills.

It is in this context of transformation and reconfiguration of adult education that the ICÉA team found it relevant to reflect on the notions of public good and common good. It seemed to us that these notions could help us to better grasp the changes underway, and to (re)think the role of the state and all stakeholders in adult education. The idea of a forum, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, seemed the perfect way to bring people together around this theme.

The forum was preceded by a collaborative process that involved, among other things, consulting a variety of people and organizations working in adult education and training. This consultation enabled us to gather their visions of adult education and training, their viewpoints on current issues, and their understanding of the notions of public good and common good.

Three notions sum up the essence of the preforum approach: co-construction, consultation and sharing.

• Advisory committee

• ICÉA units

• 42 meetings

• Diversity of people and organizations

SHARING

• Podcasts

• Internet sites

• Resources about the public and common good

The forum program was designed to provide opportunities for exchange and reflection, as well as for collaborative work. Participants identified key principles for fostering and strengthening the common good in adult education, as well as priority areas of work to be implemented in order to meet the major challenges facing adult education, and to promote the public good and the common good. Those principles included accessibility, solidarity, equity, collaboration, shared responsibility, inclusion, sharing expertise and knowledge, giving oneself the right to imagine, and knowing how to become.

The various adult education sectors and locations have a positive impact on society. Adult education contributes to personal fulfillment, empowerment and autonomy, as well as to social integration, active participation in society and job integration and mobility. It is a driving force for social transformation and economic development. At a time when we are facing various crises, particularly ecological ones, adult education and lifelong learning are more necessary than ever, especially as the decisions and choices, both individual and collective, that adults make are decisive for society as a whole.

When we think of adult education and training, we often think of literacy, continuing education, francization, vocational training or even adult general education (AGE), but we must also think in terms of areas of knowledge or skills: finance, environment, digital, health, etc.

In the context of this forum, we therefore looked at various facets of adult education that seemed essential, in line with societal demand for the development and maintenance of knowledge and skills useful for life and work, such as environmental education, media literacy and financial education.

As Daniel Baril, Director of ICÉA, pointed out, the search for the common good involves the development of “specific skills in areas rooted in daily life and individuality, but which have an impact on the whole of our families, our cities, our neighbourhoods, our countries and the entire planet.”

Several inspiring practices in different sectors of adult education and training were shared during the forum. Digital badges, for example, were discussed with the agency Cadre 21 that offers an online continuing education platform for the educational community in Quebec, French-speaking Canada and the rest of the world. Digital badges play an important role in the recognition of skills, and in this sense, they contribute to the common good.

Various forms of collaboration were also discussed. For example, the Wow Project, which brings together various players and aims to support the success of students in adult general education (AGE) through the use of digital learning and learning with the help of digital technology. Another form of shared collaboration has been the establishment of a community of practice in legal education, the Réseau en éducation juridique (the Québec legal education network). This network contributes to the common good by bringing together a number of players who didn’t know each other or work together, and creating a space for sharing experiences and pooling resources.

Another very inspiring example concerns public libraries. Their role in promoting literacy was recalled, as were the changes underway to turn them into genuine “third places” and to transform them into houses of the regular people. With this in mind, public libraries are increasingly providing spaces and laboratories for creation, learning and socialization, such as Fab Labs and medialabs, grain libraries, Wikipedia workshops, and so on.

Forum participants came up with six work streams. The work streams are free, autonomous spaces designed to strengthen the public and common good in adult education. They are made available to individuals and organizations as laboratories for ideas, exchange, reflection and work, whose operation, based on co-construction, is in itself a common good. The launch of these work streams began in February 2024.

A preforum approach involving:

• Setting up an advisory committee composed of about fifteen people from various educational, training and learning sectors and locations involved in adult education.

• Organizing consultations with the adult education community:

1. podcasts (7 episodes were produced)

2. discussion meetings (42 meetings were held with around sixty people)

• Sharing resources: podcasts, bibliographical references, etc.

Two days of exchanges and workshops aimed at:

• Introducing the concepts of public good and common good into the debate on adult education and learning, and reviewing the content of the preforum process;

• Reflecting on adult education as part of the response to the problems and challenges facing our societies;

• Drawing inspiration from practices that contribute to the common good in adult education;

• Developing shared guidelines and identifying areas for action in response to the major challenges facing adult education.

Continuing to work together to:

• Set up six adult education work streams: laboratories for ideas, exchange, reflection and work for the benefit of everyone.

During the forum, Michèle Stanton-Jean, visiting researcher from the Université de Montréal’s Faculty of Law (CRDP) and former president of the Commission d’étude sur la formation professionnelle et socioculturelle des adultes (known as the Jean Commission), presented the conceptual framework of the common good that she developed during her doctoral research. This conceptual framework synthesizes many of the thoughts and concerns shared during the forum.

The notion of justice has also been addressed in a variety of ways: the right to education, and more specifically the right to education and lifelong learning, redistributive justice, social justice, environmental justice, equity, etc. Many obstacles stand in the way of the right to education at all ages, including the lack of financial means to finance training or study, and the challenges of reconciling family, work and study.

Indeed, the notion of responsibility was at the heart of many of the discussions. The responsibility for training, educating and learning cannot rest solely with individuals. Nor should it rest solely on the shoulders of teachers in the formal system, trainers or the government. It’s a shared responsibility. We can train ourselves, among peers or within a community of practice. We can also train and learn in a variety of places and contexts (formal, informal, non-formal). All of which are important places and all of which have a role to play in promoting the common good.

Alongside justice, solidarity also emerged as an important element. Solidarity encourages collaboration and cooperation between people, communities and organizations to tackle common challenges. Throughout the forum, people called for greater collaboration and concerted action to find solutions to challenges affecting adult learners and certain sectors such as public education. Solidarity is an important principle, based on the idea that the members of a society are responsible for each other and must act together for the collective well-being.

The final concept in the model is autonomy. Over the two days of the forum, we discussed the autonomy of individuals, learners and organizations, financial autonomy and professional autonomy. Those involved in adult education have different educational approaches, visions, working methods, pedagogical approaches and missions. These different forms of autonomy are undoubtedly a common good that must be protected.

Although learners are not included in Ms. Stanton-Jean’s model, she insists that they must nonetheless be at the center of our actions and concerns. This was also reiterated, in various ways, by those who took part in the forum. The question of “where are the learners?” was also asked several times. Obviously, when it comes to so-called marginalized, vulnerable or excluded populations, we can see that these people were absent from the forum. But aren’t we all learners? There were indeed learners in the room. However, there were some missing voices that need to be heard and taken into account in order to properly respond to their needs and aspirations.

In conclusion, prioritizing the common good in adult education and training involves:

• ensuring that everyone can access and participate in the education, training and learning activities they need, whatever their age, socio-economic status, gender, level of education, etc.

• ensuring that adults can study, train and learn in contexts that take into account their realities, constraints, experiences, motivations, goals, needs and challenges. It also means ensuring that they can do so in culturally safe environments.

• recognizing and valuing the positive contribution of different sectors, organizations and training sites, and the importance of learning in formal, informal and non-formal contexts.

• taking care of the people who work there, regardless of the type of environment (community, associative, union, institutional, governmental, etc.).

Finally, working to strengthen the common good in adult education and training is inevitably a collective, community and collaborative effort.

Conceptual Framework of the common good (Stanton-Jean, 2011)

Working for the common good in adult education means training with a view to ensuring that training activities have an impact not only on the trainees themselves, but on society as a whole. For example, a person who develops critical thinking skills through media education workshops will be more likely to recognize and filter fake news, and less likely to spread it.

In Francophone minority communities, this dimension is all the more important as it contributes to the vitality and growth of the community. Indeed, for a person who joins a French-language literacy training centre, developing their literacy skills enables them to speak their language and bring their culture to life, which is beneficial both for themselves and for the whole community.

Yet, across Canada, training programs are increasingly designed to meet employability objectives or, more generally, with a new liberal vision, aligned more with labour market objectives than with the interest of the common good. While this approach is useful for training the workforce and helping people who need help to enter the job market, its relevance is less obvious in the case of literacy and basic training.

In fact, developing basic skills are useful in all areas of life, not just in the workplace. When you feel more at ease with the written word, or with technology, you’re more at ease communicating, making choices at the grocery store or with your personal finances, or engaging in leisure activities. Better literacy skills even have a positive impact on health, as shown by the latest results of the survey conducted by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. (Jacobsen, L., Long, A. 2017).

The benefits of developing literacy skills are also evident in family literacy programs. Parents who are more at ease with the written word are better equipped to support their children’s schooling and perseverance. These benefits are not easily measured in the short term, in the same way as unemployment or graduation rates, but they do have long-term effects on the lives of individuals and, by extension, their environment.

The advantage of training offered by community organizations is that they seek to adapt to the different needs of the adults who come to them: more flexible than the services offered by government agencies, those offered by community centres take into account the environment of these adults, their potential and their constraints.

In Ontario, Literacy and Basic Skills programs come under the umbrella of Employment Ontario. As a result, the focus of adult training programs is on employability. The development and reinforcement of adult autonomy are part of the LBS programs, but with a focus on professional integration. As a result, training activities cannot focus on the social and community aspects. However, it is essential for community members to discuss their shared francophone culture and

values, as well as developing general skills that can be transferred into the workplace.

LBS centres are places where people can develop their self-confidence, team spirit, communication and interpersonal skills,1 all of which are essential for both community life and job retention.

When we work on enhancing adult skills, we don’t isolate these skills according to the first place where they will be useful and profitable. We know that by improving their ability to use information, people will be more independent in all spheres of their lives. Even if this improvement is aimed at professional integration, we can see that it will have a global impact. The same thing happens when generic skills are improved: having greater confidence in oneself and in one’s francophone culture is an advantage for the community, as well as being useful in the workplace.

Rather than focusing on employability, shouldn’t a ministry responsible for adult literacy think about these services in a more holistic way? This would enable francophone minority communities to feel the government’s commitment to francophone culture, to strengthen participation within the community, to share common values while keeping in mind that they are the foundation of the common good.

1 On this subject, see the site dedicated to generic skills: http://mypersonalskills.net/

2 Link to the Official Languages Act: https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/o-3.01/page-3.html

Generic, citizenship and community skills make it easier to adapt to socio-economic change, keep a job and keep other skills up to date. Within a minority community, they help to resist the risks of marginalization or exclusion.

Focusing on generic skills from the perspective of the common good also means recognizing the breadth of training venues and methods, the diversity of ways to acquire skills, and the relevance of community centres and all informal training venues: all elements that are useful to any community, but which become vital for minority environments. This is the promise of the Official Languages Act 2 as it has been modernized in 2023. Section 41(3) of the Official Languages Act has been reworded to state that “the Government of Canada is committed to advancing formal, non-formal and informal opportunities for members of English and French linguistic minority communities to pursue quality learning in their own language throughout their lives, including from early childhood to post-secondary education.” This recognition of the variety and continuity of learning opportunities should help affirm the importance and value of literacy and basic training centres, support the development of multiple skills and thus strengthen the common good that is francophone culture.

In 2013, the first International Conference on Learning Cities was held, which saw the adoption of the “Beijing Declaration on the Creation of Learning Cities”1 and the reference framework “Key Characteristics of Learning Cities.”2

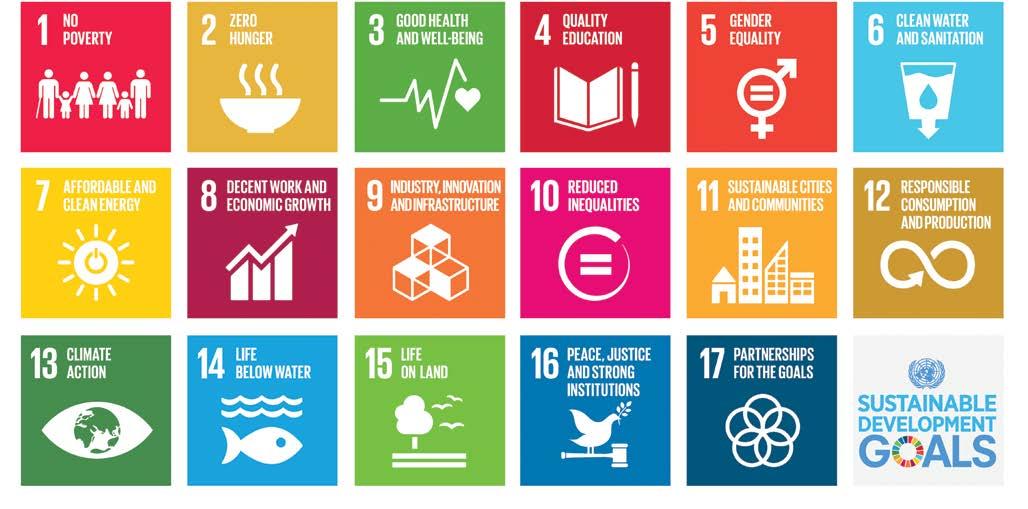

These two documents became the founding pillars of the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities, created by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning following this first conference to foster social cohesion, economic development and sustainable development in urban areas. In 2015, the network began receiving applications and accepting members. Since then, it has become one of the driving forces in promoting lifelong learning and hopes to contribute to achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals at the local level.

In 2023, 64 new cities in 35 countries joined UNESCO’s Global Network of Learning Cities, bringing the total number of cities in the network to 356 in 79 countries.3

The 2023 cohort includes cities as diverse as San Luis Potosí in Mexico, Ocotal in Nicaragua, Recife in Brazil, Lviv in Ukraine, Manchester in the UK, Fundão in Portugal, Liège in Belgium and Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, Nanjing in the People’s Republic of China, Gwangju in the Republic of Korea, Bangkok in Thailand, Fez in Morocco, Muscat in Oman, Alexandria in Egypt, Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia, São Filipe in Cape Verde or Dakar in Senegal.

The call for applicants is launched every two years. Cities that are already members of the network must submit a progress report detailing the implementation of their learning city strategy. These progress reports must also be submitted every two years.

Cities must follow monitoring and control procedures with reasonable objectives and indicators that they themselves have selected and that are specific to them, based on their own environmental, social, cultural and economic issues, as well as the needs expressed by their citizens. The cities develop their own policy frameworks for planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation.

The UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning produced a document in 2017 to help translate the global sustainable development goals into local actions. The document drew on concrete actions taken by member cities of the global network to promote green and healthy environments, equity and inclusion, and decent working conditions and entrepreneurship.

Many of these actions required strong political leadership, integrated governance and partnerships at various levels with public and private actors from many sectors, including that of civil society.

¹ See the article on the Beijing Declaration on page 30. The document was adopted by the World Conference on Learning Cities in Beijing (China), October 21-23, 2013. It can be consulted in full at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226755

² In 2012, the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning held its first workshop to develop a framework for the key characteristics of learning cities. This document is the result. It can be consulted here: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226756

³ UNESCO, February 14, 2024, UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities: 64 new members from 35 countries, Press release, found at URL: https://www.uil.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-global-network-learning-cities-64-new-members-35-countries

This document, entitled Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action,4 has three thematic sections:

• Green and healthy learning cities (environmental sustainable development);

• Equitable and inclusive learning cities (individual empowerment, intercultural dialogue and social cohesion);

• Decent work and entrepreneurship in learning cities (economic development and cultural prosperity).

These three dimensions of sustainable development are intrinsically linked, and actions to encourage lifelong learning will generally have an impact on several of these dimensions at the same time. The fourth dimension, just as important as the other three, is culture (cultural expression and heritage, and diversity), and is cross-cutting.

The document contains many examples of actions implemented by the various cities in the Network, which show the diversity of possible initiatives and reflect the wide variety of stages of development of the learning cities in the network. Here are just a few...

Examples of activities for a green and healthy living environment:5

• Offer health training programs for teachers;

• Create mobile clinics to empower citizens by enabling them to learn more about their own bodies and health issues;

• Set up sanitation committees, responsible for creating a collective awareness of hygiene and health issues among residents;

• Provide residents with garbage cans and recycling bins for their homes;

• Set up street cleaning teams;

• Incorporate learning activities, such as recycling, into events to raise public awareness of environmental protection issues;

• Create places where people can learn to ride a bike;

• Promote alternative forms of mobility in the city and inform the public about the rights and duties of road users and the rules of the road for cyclists in the city.

Examples of activities to promote equity and inclusion for all:6

• Offer alternative educational opportunities to all citizens, and in particular to vulnerable groups who do not follow a formal education or training pathway;

• Offer free online courses;

• Promote intergenerational learning initiatives;

• Offer career guidance services, especially for women;

• Create mobile libraries to provide reading opportunities for all;

• Use cultural centres as places of learning, combining culture, art and learning;

• Encourage young people to take part in public life.

Examples of activities to ensure decent work and encourage entrepreneurship: 7

• Offer training programs for young people and adults outside the school system;

• Encourage the production and sale of local products;

• Develop partnerships with local employers to improve participation and access to training and employment for people with disabilities;

• Offer career guidance services in schools;

• Support companies that offer work-study programs or on-the-job training for students;

• Offer workshops and mentoring programs to encourage entrepreneurship among women and vulnerable groups, and in remote rural areas, workshops and programs for all.

Given that more than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas and that, according to the World Bank, 70% of the population will be urban by 2050, it seems appropriate to hope for cities of the future that are more learning, more participative, and in which citizens are at the forefront of their concerns.

4 UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2017, Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action, Hamburg, 24 p., located February 22, 2024 at URL: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260442

⁵ See page 10 of the document Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action, available here : https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260442

⁶ See page 13 of the document Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action, available here : https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260442

⁷ See page 17 of the document Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action, available here : https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260442

The UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities supports the achievement of all 17 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG 4 (Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all) and SDG 11 (Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable). Learning cities promote green and healthy environments, strive to achieve equity and inclusion, and support decent work and entrepreneurship. They are therefore key drivers of local-level sustainability in both urban and rural areas.

“One of the responsibilities that we have is also to manage to build a stronger narrative and build more evidence, so that we can actually explain and demonstrate to policymakers that, okay, if you invest more in lifelong learning, in a certain way you will also contribute to climate change mitigation policies, you will contribute to employment, etc.”

December 2022, David Atchoarena, Director of UNESCO’s Institute for Lifelong Learning*

*In an interview with The PIE News: https://thepienews.com/pie-chat/david-atchoarena-unesco

Sustainable Developement Goals

Source: https://www.uil.unesco.org/en/learning-cities

In October 2022, Edmonton became the first Canadian city to join UNESCO’s Global Network of Learning Cities (GNLC). Edmonton is the northernmost big city in North America, and becoming a member of the UNESCO network represents the culmination of many years of dedication, across the community, to education and lifelong learning for everyone.

In 2021, a community coalition was established, led by Edmonton’s mayor, that included the Edmonton Public Library, Edmonton’s three school boards, specifically Edmonton Public Schools, Edmonton Catholic Schools and Conseil scolaire Centre-Nord, and all eight of Edmonton’s post-secondary institutions (University of Alberta, Concordia University of Edmonton, The King’s University, MacEwan University, NAIT, NorQuest College, Yellowhead Tribal College and Athabasca University).

“As a community of learners, we celebrate this opportunity to connect with like-minded cities around the world. Our openness, cultural diversity and curiosity make Edmonton an excellent addition to the Global Network of Learning Cities. Our ambition is to attract a million more people over the coming few decades to our city of eager learners, energetically looking to embrace new ideas, emerging technologies, and ways of working and learning.” Mayor Amarjeet Sohi, City of Edmonton

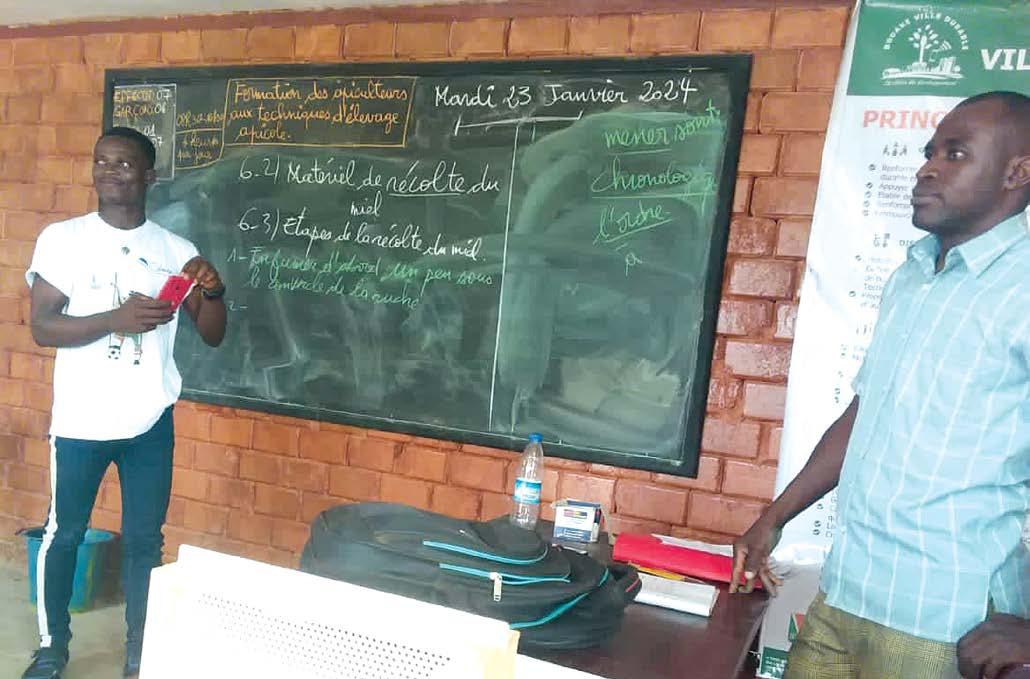

Nicknamed the “crossroads city,” this African city in central Côte d’Ivoire, some 350 km from the capital Abidjan, joined UNESCO’s network of learning cities in September 2022. According to Mame Omar Diop, Unesco’s representative in Côte d’Ivoire: “This is no accident. A lot of hard work went into awarding this label to the city, the first in Côte d’Ivoire to receive it.” 1

This city of more than 830,000 residents estimates that the literacy rate among its population is around 57%, but only 41% among women.2 Its application was accepted, in part, because the city has launched a literacy program. By 2022, the city had 86 literacy centres, with a total of 2,091 people enrolled, including 1,270 women.3 The city of Bouaké has set itself the ambitious medium-term goal of achieving a 75% literacy rate by 2035.4

By joining the network, Bouaké will be able to share and exchange ideas with other cities, find solutions to some of the problems it faces, forge partnerships, and, above all,

benefit from UNESCO’s multi-donor funding mechanism. The city knows that it must first and foremost meet the needs in terms of awareness and teaching materials, as well as such basic needs as the electrification of certain centres and the purchase of furniture.5

The city has also made considerable efforts in terms of sustainable development, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, with policies to integrate young people into a “green and circular economy,” and is focusing its efforts on the training and professional integration of young people, on participative

1 Coulibaly Souleymane (August 2022), Côte d’Ivoire : Alphabétisation et culture - Bouaké fait son entrée dans le réseau des villes apprenantes de l’Unesco, Le Patriote Presse quotidienne, Abidjan, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://fr.allafrica.com/stories/202208250481.html

2 L’inspiration politique (November 2023), Bouaké en campagne d’alphabétisation, INNOMEDIAS, Orléans, France, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://www.linspiration-politique.fr/2023/11/07/cote-divoire-bouake-en-campagne-dalphabetisation

3 Coulibaly Souleymane (August 2022), Côte d’Ivoire : Alphabétisation et culture - Bouaké fait son entrée dans le réseau des villes apprenantes de l’Unesco, Le Patriote Presse quotidienne, Abidjan, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://fr.allafrica.com/stories/202208250481.html

4 L’inspiration politique (November 2023), Bouaké en campagne d’alphabétisation, INNOMEDIAS, Orléans, France, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://www.linspiration-politique.fr/2023/11/07/cote-divoire-bouake-en-campagne-dalphabetisation

5 Coulibaly Souleymane (August 2022), Côte d’Ivoire : Alphabétisation et culture - Bouaké fait son entrée dans le réseau des villes apprenantes de l’Unesco, Le Patriote Presse quotidienne, Abidjan, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://fr.allafrica.com/stories/202208250481.htm

governance and on greening the city.6 In 2019, Bouaké began planting trees on its territory, and in 2022, the city installed 34 solar electricity poles to supply the city hall with electricity.

In early 2024, it launched a “Green and Circular Economy Training” program to prepare its “citizens to adopt innovative and environmentally-friendly practices while opening the door to a more sustainable and prosperous future.”7 In particular, the city wants to increase the capacity of urban market gardeners in agroecology: the AZARIA Beekeeping Centre has organized its first training course on beekeeping in an urban environment, and AMEA Energy has organized a training course on biogas and biochar. The city will also be offering training, coaching and funding in poultry farming, snail breeding, edible mushroom production and urban agroecology to equip its young entrepreneurs.

Lastly, the city is endeavouring to involve its citizens in the management of household waste by organizing meetings with the civil society (neighbourhood committees, youth and women’s associations), by organizing a spring cleanup operation in different parts of the city8 and with a project for a plastic waste recycling plant to be developed by a Côte d’Ivoire start-up company, Coliba Africa.9 There is no doubt that with its inclusion in the UNESCO global network of learning cities, the city of Bouaké can play a showcase role by encouraging the exchange of practices and tools promoting inclusion, sustainability and the democratization of learning throughout West Africa.

6 Consult the page dedicated to Bouaké on the UIL website: https://www.uil.unesco.org/en/learning-cities/bouake

7 Facebook post on January 16, 2024, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://www.facebook.com/bouakevilledurable

8 Facebook post on October 30, 2023, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://www.facebook.com/bouakevilledurable

9 The «Échos des villes» page (May 2023), Bouaké passe au recyclage des déchets plastiques, AIMF website, found February 28, 2024 at the URL: https://www.aimf.asso.fr/actualite/bouakepasse-au-recyclage-des-dechets-plastique

The French town of Mantes-la-Jolie lies 50 km west of Paris and has a population of almost 45,000 people, including many young people and families from a wide range of backgrounds. The town made the headlines regularly in France in the 1990s for its crime rates, urban riots and the Val Fourré housing project, bringing together all the clichés associated with the suburbs in a major French city.

In 2017, Mantes-la-Jolie joined UNESCO’s network of learning cities in order to make it, according to its mayor, a “tool for local policy and social cohesion.”1 It should be noted that 42% of people over the age of 15 in the town have no diploma, compared with an average of 32% in France.2

The local administration is counting on its recent status as a Learning City to change the socio-cultural dynamics, to the extent that the town’s mayor, Raphaël Cognet, sees education and learning at all ages as “the solution to 99% of [its] problems.”3

Initiatives supported by the municipality include:

• The Enjoy association, which offers monthly themed workshops and a cultural outing for around twenty children aged 9 to 13 to help them develop their cultural awareness;

• The Sigma F association, which offers tutoring to “acquire technical, academic and human skills”, helps with school and career guidance, and offers programs focused on active citizenship;4

• The establishment of the “École française des femmes” (French School for Women), to support women in their career paths and job searches, and of socio-linguistic workshops, offered in three neighbourhoods to help adults learn French;

• The “Citoyen dans ma ville” (Citizen in my Town) project, which gives young people access to financial assistance to carry out a project in exchange for 20 hours of volunteer work in a local association (often language study trips or university exchanges);

• The “Choose your future” program, which involves university students who are receiving the “Mantes + Students” grant sharing their experiences with high school students;

• The transformation of a town square into a multi-purpose space capable of hosting different types of events and activities, including an ecological restoration initiative (greenery, grove, wetland), a playground and sports area, festival pavilions and a reading area adjoining the town’s media library.

The town’s mayor, Raphaël Cognet, sees education and learning at all ages as “the solution to 99% of [the town's] problems.”

1 Branquart, Victor (December 2019), «Mantes-la-Jolie, une ville où l’on apprend toute la vie», We demain, consulted online on February 28, 2024 at the following URL: https://www.wedemain.fr/partager/mantes-la-jolie-une-ville-ou-l-on-apprend-toute-la-vie_a4428-html

2 Oddoux, Anaïs (Juin 2019), «La « Ville apprenante » : réapprendre à faire la ville?», City Linked, consulted on February 28 at the following URL: https://www.detourbycitylinked.fr/la-ville-apprenante-reapprendre-a-faire-la-ville

³ Branquart, Victor (December 2019), «Mantes-la-Jolie, une ville où l’on apprend toute la vie», We demain, consulted online on February 28, 2024 at the following URL: https://www.wedemain.fr/partager/mantes-la-jolie-une-ville-ou-l-on-apprend-toute-la-vie_a4428-html

⁴ Consult its website: https://sigmaf.org

1

The city of Tafí Viejo is located in the province of Tucumán in Argentina. A member of UNESCO’s Learning Cities Network since 2022, the city has a population of 56,407 people, who, according to UNESCO, have completed an average of 12 years of education. Since joining the network, the city has put in place numerous initiatives to promote the SDGs and learning among its citizens.

Here are a few recent examples (2024), taken from the city’s FB page:1

• The healthy town square project, offering free physical and sporting activities to residents several times a week in several of the city’s green spaces.

• A municipal partnership to open a small kiosk selling local food products at the La Toma spa in order to encourage healthy eating habits.

• The city hosts an open-air craft and business fair to promote local creativity.

• The Los Pocitos health centre ran a workshop on addiction prevention for local families. Topics covered included: how to detect an addiction, the differences between drug use and problematic drug use, myths and realities about problematic drug use, and family protection factors.

• An agreement was signed between the La Tierra de Nuestros Hijos Foundation (the land of our children) and the city of Tafí Viejo. The agreement aims to promote environmental sustainability and implement projects to remedy existing environmental damage and encourage sustainable development.

• The city offers senior camps during the summer months; in 2024, over 70 participants have already started enjoying art, yoga, folklore and swimming workshops.

• The Jose Perea Muñoz educational centre has opened enrolment for courses for the start of its 2024 academic year. The centre offers a variety of afternoon and evening courses for people who work or who are otherwise busy during the day: sewing, graphic design, carpentry, appliance repair, IT, hairdressing, cooking, pastry-making or textile production.

You can follow news from the city of Tafi Viejo on its municipal website: https://www.tafiviejo.gob.ar

Adopted at the International Conference on Learning Cities, Beijing, China, October 21–23, 2013

This document is the foundation of the UNESCO Learning Cities Network. We are publishing it in a shortened version, but it can be consulted in full at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226755

We, the participants at the International Conference on Learning Cities, co-organised by UNESCO, the Ministry of Education of China and Beijing Municipal Government (Beijing, 21–23 October 2013) declare as follows:

We recognise that we live in a complex, fast-changing world where social, economic and political norms are constantly redefined. Economic growth and employment, urbanization, demographic change, scientific and technological advances, cultural diversity and the need to maintain human security and public safety represent just a few of the challenges to the governance and sustainability of societies.

We affirm that, in order to empower citizens – understood as all residents of cities and communities – we must strive to give them access to and encourage their use of a broad array of learning opportunities throughout their lives.

We believe that learning improves quality of life, equips citizens to anticipate and tackle new challenges, and helps build better and more sustainable societies.

We acknowledge that the concept of learning throughout life is not new; it is an integral feature of human development and is deeply rooted in all cultures and civilisations.

We maintain that lifelong learning confers social, economic and cultural benefits to individual learners and communities and should be a primary focus of cities, regions, nations and the international community.

We acknowledge that the majority of the world’s population now resides in cities and urban regions, and that this trend is accelerating. As a result, cities and urban regions play an ever greater role in national and global development.

We recognise that “learning communities”, “learning cities” and “learning regions” are pillars of sustainable development.

We accept that international and regional organisations, as well as national governments, have a vital role to play in developing learning societies. However, we are aware that this development must be rooted in sub-national regions, cities and all types of community.

We know that cities play a significant role in promoting social inclusion, economic growth, public safety and environmental protection. Therefore, cities should be both architects and executors of strategies that foster lifelong learning and sustainable development.

We acknowledge that cities differ in their cultural and ethnic composition, heritage and social structures. However, many characteristics of a learning city are common to all. A learning city mobilises human and other resources to promote inclusive learning from basic to higher education; it revitalises learning in families and communities; it facilitates learning for and in the workplace; it extends the use of modern learning technologies; it enhances quality in learning; and it nurtures a culture of learning throughout life.

We envision that a learning city will facilitate individual empowerment, build social cohesion, nurture active citizenship, promote economic and cultural prosperity, and lay the foundation for sustainable development.

We commit ourselves to the following actions, which have the power to transform our cities:

1. Empowering individuals and promoting social cohesion

2. Enhancing economic development and cultural prosperity

3. Promoting sustainable development

4. Promoting inclusive learning in the education system

5. Revitalising learning in families and communities

6. Facilitating learning for and in the workplace

7. Extending the use of modern learning technologies

8. Enhancing quality in learning

9. Fostering a culture of learning throughout life

10. Strengthening political will and commitment

11. Improving governance and participation of all stakeholders

12. Boosting resource mobilisation and utilisation

Numerous places already define themselves as learning cities or regions. They are keen to benefit from international policy dialogue, action research, capacity building and peer learning, and to apply successful approaches to promoting lifelong learning. Therefore,

1. We call upon UNESCO to establish a global network of learning cities to support and accelerate the practice of lifelong learning in the world’s communities. This network should promote policy dialogue and peer learning among member cities, forge links, foster partnerships, provide capacity development, and develop instruments to encourage and recognise progress.

2. We call upon cities and regions in every part of the world to join this network, to develop and implement lifelong learning strategies in their cities.

3. We call upon international and regional organizations to become active partners in this network.

4. We call upon national authorities to encourage local jurisdictions to build learning cities, regions and communities, and to participate in international peer learning activities.

5. We call upon foundations, private corporations and civil society organisations to become active partners of the global network of learning cities – drawing on experience gained in private-sector initiatives.

In everyday language, education and learning refer to the primary, secondary, and post-secondary school systems.

When we work in adult literacy and basic training, we work in an environment that recognizes that people can learn at any age and develop skills of all kinds, which go far beyond academic knowledge. The learning that takes place in a literacy centre remains part of an educational framework, even if it is not a formal one.

Taking an even broader approach to education, community literacy is a concept that looks at how an entire community can participate in the development of literacy skills. This refers to the way in which a multitude of actors, whether institutional or community-based, can become involved and feel concerned by lifelong education, when their primary mission is not educational, or at least not perceived as such. Examples include museums, health clinics, sports and leisure centres, libraries and so on.

Community literacy is thus defined as a community’s ability to mobilize a diversity of stakeholders around the learner, thereby fostering the development of skills throughout the community. This brings us back to the notion of education as a common good, at two levels: on the one hand, the community recognizes itself as bound by and invested with educational responsibilities, and on the other, it learns and builds knowledge and skills.

Community literacy goes beyond the school setting, covering all dimensions of life and being part of a lifelong learning perspective, making it possible to meet the educational needs of people at various stages of their lives.

Community institutions and organizations whose primary mission is not training, or education are well advised to see themselves as stakeholders in lifelong learning. From parent discussion groups offered by social services to community gardens and library activities, learning opportunities are everywhere. Yet the people who work in these sectors do not usually see themselves as actors in lifelong learning. By changing their posture and seeing themselves as trainers, these people could see themselves as an integral part of a wider educational community.

Computer courses, public legal education, perinatal support, leisure and craft activities, and employability development workshops all have different short-term objectives, but they all share the same long-term goal: to increase people’s skills to promote their autonomy. All these activities, and many others, require the use of the written word. By encouraging the development of skills in reading, writing, and understanding

information, community literacy gives people the opportunity to become fully involved in society, to make their voices heard and to defend their rights. It is linked to a multi-partner commitment to emancipation and social justice.

By facilitating access to information and encouraging the creation of knowledge within communities, community literacy helps to reduce disparities by providing everyone with the means to learn, train and make informed decisions.

In times of digital transition, community literacy could be seen as one of the pillars of democracy, offering everyone access to the resources and knowledge essential for active participation in the social, cultural, and political spheres.

In short, community literacy plays an essential role in developing individual and collective skills and promoting inclusion and collaboration.

As mentioned above, the first prerequisite for putting community literacy into practice is the involvement of community members, who must recognize themselves as players in lifelong learning.

Then, each community must identify the needs and issues related to its own characteristics and prioritize its actions. It may, for example, choose to work more on population health or on the vitality of Francophone culture.

Finally, it is important to inform and promote reading by exploring different dimensions of literacy, through the media, digital, etc.

The role of libraries in community literacy is essential in promoting access to information, education, and personal development within communities: they offer free access to a variety of resources, such as books, magazines, newspapers, online databases, and computers, and make it easier to find reliable and relevant information. Libraries organize workshops, family reading activities and computer courses that enhance literacy and digital literacy skills. They support lifelong learning by offering resources for all ages. Libraries also encourage the use of French by making local and international literature available. They organize cultural events, exhibitions, and book clubs to encourage the exchange of ideas and the sharing of experiences. Libraries are open to all, regardless of age, social status, or ethnic origin.

In short, libraries play a crucial role in promoting literacy, empowering people, and strengthening communities. They are guardians of knowledge and places where everyone can enrich themselves intellectually and socially.

Schools, colleges, and universities are, of course, key players in developing literacy skills among learners, as they have the resources to organize reading, writing and communication activities.

Community groups, social centres and local associations are usually heavily involved in promoting literacy. They organize workshops, reading clubs and events for community members.

Local and national governments often support community literacy initiatives. They allocate funds, create policies, and implement programs to improve literacy skills. Local service points relay information and support the community as much as the individuals within it.

Some companies and entrepreneurs engage in social responsibility projects to promote literacy: they may sponsor reading, mentoring or skill development programs.

The media, blogs, podcasts, and online platforms can help to disseminate information and promote literacy, by creating educational content and encouraging everyone to participate.

People working in teaching, training and education are key players in improving literacy skills, since they collaborate directly with learners to build their capacities.

Community literacy benefits Francophone minority communities in Canada by:

Community literacy enables community members to better understand their history, culture, and traditions. It promotes the preservation of the French language and strengthens the sense of belonging to the Francophone community.

By encouraging reading, writing and communication, community literacy helps to improve people’s language skills. This facilitates their active participation in society and enables them to express themselves better.

Community literacy improves access to educational resources, such as books, newspapers, workshops, and programs. It enables community members to acquire knowledge and stay informed.

Community literacy activities, such as book clubs, writing workshops and cultural events, encourage social interaction. They create bonds between people and strengthen community cohesion.

A literate community is better prepared to participate actively in democratic life. Community literacy encourages civic engagement and speaking out.

In short, community literacy is a powerful tool for empowering Francophone minority communities, promoting their culture and fostering their development.

It is an essential area that mobilizes many players and institutions to strengthen literacy skills, in a global and inclusive perspective.

Mercier, J.-P. & Martel, M. D. (2021). La littératie communautaire : explorer les pratiques des acteurs institutionnels au sein des communautés éducatives. Revue de recherches en littératie médiatique multimodale, 14. https://doi.org/10.7202/1086910ar

Public education systems were set up because they are the foundation of society, serving to consolidate national sentiment and the unity of the nation-state. Governments have progressively organized the education of populations, set up governance structures and thus designed a public good. However, educational activities, even when offered as part of a public system, contribute to the common good. In democracies, the aim has been to improve literacy levels so that individuals are more autonomous and can make choices that contribute to the common good, for example, by participating in decision-making by voting for those who make the laws.

SIMILARLY, TRAINING OFFERED IN INFORMAL OR NON-FORMAL SETTINGS CONTRIBUTES TO THE COMMON GOOD. HERE ARE JUST A FEW EXAMPLES:

Thanks to financial education, a person will be able to make a budget, manage their accounts and plan their spending. If more people have developed these skills, society as a whole benefits from this, because its population is less indebted and more financially independent.

With consumer education, a person understands his or her rights and remedies when buying goods online. On a larger scale, knowledge of the right cybersecurity gestures enables more people to protect themselves against fraud.

Among other things, media literacy helps develop the skills to respond to cyberbullying, whether for oneself or in support of a victim. People who feel safe when using digital media are more likely to participate in cyber citizenship, making their voices heard to take part in democratic debates.

Legal education training and resources help people to know and understand their rights. Confidence in one’s ability to navigate the justice system is important when it comes to asserting one’s rights: the more people in a society assert their fundamental rights, the more the law advances and the more egalitarian society becomes.

People who take part in environmental education activities are better equipped to understand the impact of their choices on their environment, the issues involved in protecting natural environments, and contribute to preserving biodiversity.

Intercultural or multicultural education enables people to open up to cultural diversity and learn how to communicate with others, thus helping to develop “living together” in societies.

From March 4th to March 6th, 2024, COFA took part in the National Summit on Lifelong Learning, organized by the Réseau pour le développement de l’alphabétisme et des compétences (RESDAC). These three days of meetings brought together players from Canada’s Francophonie to talk about lifelong learning in all spheres of life.