votre référence en formation des adultes

votre référence en formation des adultes

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Coalition ontarienne de formation des adultes (COFA).

Gabrielle Lopez

This issue takes up the themes discussed at the Forum 2024, for those who were unable to attend, or for those who wish to recall what COFA has been trying to instill in the network for several years. It proposes a reflection on the transition from a training culture to a learning culture, where each person engages in an active and dynamic approach to learning. From this perspective, learning to learn becomes central. As a reminder, a learning culture is based on a set of beliefs, practices and attitudes that support continuous learning within an organization or community. The key elements that define it are:

1. Growth mentality: valuing the development of skills and learning through experience, seeing failure as an opportunity for progress;

2. Support for continuing education: investment in training programs and encouragement of self-directed learning;

3. Curiosity and innovation: promoting experimentation, research, new ideas and experiential learning;

4. Collaboration and knowledge sharing: encouraging the exchange of knowledge and learning from others, notably through mentoring and communities of practice;

5. Constructive feedback: the importance of regular feedback to adjust and improve performance;

6. Self-directed learning: encouragement to proactively identify and meet one’s own learning needs;

7. Use of technology: adoption of online platforms and tools to facilitate access to educational resources;

8. Recognition of learning: formal or informal acknowledgement of learning efforts, through certification or praise. These elements seek to create an environment where continuous learning is central to practices and interactions. This approach to learning culture offers many benefits, including enhanced productivity, greater adaptability to change, and increased member satisfaction.

In this issue, you’ll discover the contributors to Forum 2024 who are supporting us in this paradigm shift.

Daniel Baril points out that a number of evolutions are underway, forecasting profound transformations in the way learning will be accessed in the near future. Vienna Blum shares her experience of running a joint workshop with Donald, where they sought to gradually unsettle the training system, one workshop at a time. Chantal Carrière presents a Competencies Framework designed to recognize the skills of practitioners and enhance the value of the LBS program, while guaranteeing the viability of the network, notably through tools such as digital badges.

A three-way conversation - between me, Donald Lurette and Hervé Dignard - explores Social-Emotional Skills and a pilot project for skills recognition in Indigenous communities in Northern Quebec. We revisit David Kolb’s experiential learning and explore how this approach can be applied to LBS practices.

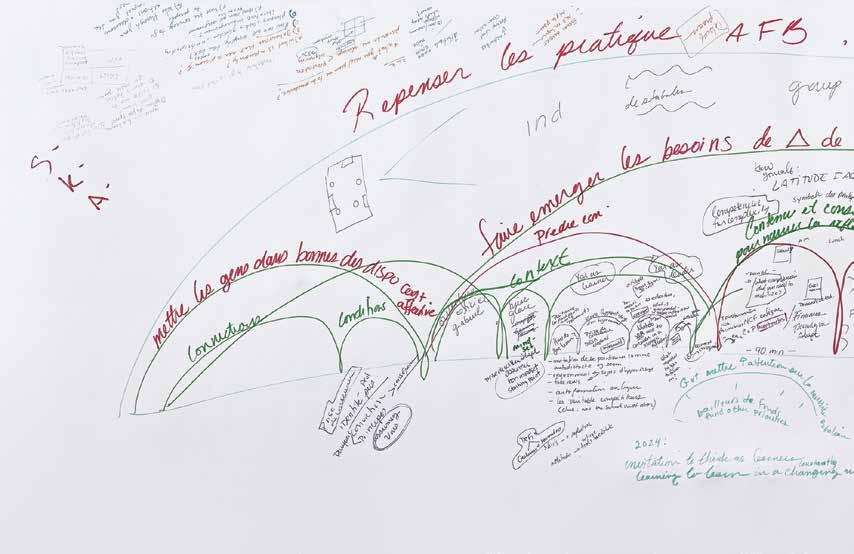

We then move on to a higher level of complexity with the Learning Arches, a method developed by Simon Kavanagh and perfectly in tune with our concerns. We also take advantage of FADIO’s practical advice on running an online community.

Last but not least, we echo the needs expressed by our participants, because listening to and meeting your expectations remains a constant priority for COFA. I would like to conclude by thanking Laurence Buenerd, who has devoted four years to making Perfectio a valuable, shared tool, both within the network and in the wider LBS world.

Written by Laurence Buenerd

DANIEL BARIL IS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE MONTREAL-BASED INSTITUT DE COOPÉRATION POUR L’ÉDUCATION DES ADULTES (ICÉA), AS WELL AS CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF THE UNESCO INSTITUTE FOR LIFELONG LEARNING (UIL). HE OPENED THE COFA FORUM WITH AN IMPACTFUL PRESENTATION ON THE CHANGES THAT ARE FAST APPROACHING IN THE WORLD OF ADULT EDUCATION. SOME MAY SEEM OBVIOUS, BUT OTHERS ARE NOT QUITE ON THE RADAR YET. HERE’S A SUMMARY OF THE BIG IDEAS HE PRESENTED.

While the changes taking place in the field of Adult Education may seem remote, they are actually happening. Many recent changes, such as the integration of smartphones into our lives, go relatively unnoticed even though they are very real. Daniel reminded listeners that they themselves have integrated many new learning practices without necessarily realizing it. One example: before the pandemic, few people knew what Zoom, Teams or Google Meet were. These tools were quickly integrated into professional practice, without having been “learned” in the formal sense of the word. In this case, learning took place through self-training, with perhaps a small dose of peer learning, if a colleague explained certain functionalities.

The most obvious change is the arrival of digital technology. It has taken hold at every level: as a place of learning, as an object of learning, as a tool for learning and as a bridge between people. This revolution has taken place here in Canada, but elsewhere in the world, such as in Africa, Asia or South America, mobile phones have suddenly become tools for access to training, or even places for training. Everywhere, thousands of applications offer training in every field: health/ wellness, languages, services of all kinds... In addition to their services, they also offer their users help capsules to help them get started.

What has changed in the basic training landscape is that the level of skill and knowledge expected of everyone has soared, and now encompasses all spheres of life: health, finance, parenting, and so on. We are now in a knowledge-based

society, where the development of knowledge is fundamental to the lives of individuals, organizations and communities, and in a multitude of fields. What’s also changed is that it’s no longer enough to know, you have to know the right things. There are many challenges to accessing this knowledge, many inequalities and discrimination.

On YouTube, says Daniel, there are over a billion views of educational tutorials a day, and 1/8th of humanity watches YouTube videos every day. Which makes him think it’s the biggest school in the world. The platform is currently investing in YouTube Education, a service that will enable anyone to upload tutorials and sell them. He sees this as a complete democratization of the educational offering.

All the Web giants are now investing heavily in the field of continuing education and employment, with themes such as programming, management, psychological health in the workplace and so on.

Another important change taking place in the field of basic education and training is that training spaces are no longer limited to face-to-face or online classes. They take on all kinds of forms for learners. Universities and other training institutions are now facing serious competition from a proliferation of platforms offering catalogues or complete Bac-type online training courses, with packages and the issue of certificates at the end of the course, rather like Netflix models of learning. Some platforms even offer nested educational services, such as learning support, or assessment of prior learning and skills. We are thus witnessing the fragmentation of the training universe and the creation of a genuine industry.

“YouTube Education will soon enable anyone to upload tutorials he or she has created and sell them. It’s a complete democratization of educational offerings.”

“All the Web giants are investing massively in continuing education and employment.”

Daniel has identified the main trends in the transformed educational offer:

• Mobile learning, with thousands of mobile learning applications;

• Blended learning, such as smart classrooms that offer different types of access (face-to-face, online, synchronized, desynchronized);

• Personalized learning paths, with a personalized digital learning environment that accompanies the individual throughout his or her life;

• Personalized learning environments that offer a combination of all available learning tools and models. Daniel sees this as a set of pedagogical projects that would be set up in a space enabling face-to-face and online learning, offering a panoply of learning resources, and using tools such as artificial intelligence while also providing access to other humans. He is thinking, for example, of intelligent virtual agents, such as what the Khan Academy1 is now offering, for its English version, with its Khanmigo intelligent tutor;

• The Metaverse, which in the future should combine various technologies and offer, for example, 3D learning environments.

But one of the most dramatic changes to come, in his view, is that learners will have to learn how to learn and manage their own training path.

“Universities that think their competitors are other universities are wrong. Their competition is YouTube, it’s Coursera, etc.”

Daniel also warned his listeners that several private companies, such as Khan Academy, Coursera and Moodle, are actively thinking about their future educational offerings, and are working in particular to improve the user-friendliness of their tools and access to support for their users.

Daniel then came back to the idea of supported learning paths, which began with people’s backgrounds: where they came from, what their initial pathway was, their baggage, and so on. And that would be mapped out according to where they wanted to go, what their project was, what they needed to know or learn, and so on. For him, the service offer becomes the toolbox that these people will use according to their needs and aspirations. He proposed the image of a learning archipelago, with learners moving from island to island according to their needs: face-to-face, community-based, etc. The question is how to get them from one island to another, and how to organize the territory to facilitate their journey.

Daniel mentioned another change that has occurred since the pandemic: the fragmentation of pedagogy and delivery modes (face-to-face, online, synchronous, asynchronous), to meet all needs. In his view, this fragmentation is part and parcel of training engineering, the aim of which is to organize learning according to a certain number of parameters: content, objectives, target audience, delivery methods, type of accreditation, etc. This engineering also includes the need to take into account the specific needs of each client, their career paths, before, during and after learning, and to ensure that these people are monitored throughout their lives.

For an organization, this implies a holistic service offering, possibly with partnerships to ensure a continuum of services. For him, badges fit into this perspective by enabling standardization of prior learning recognition.

For him, the essential question that organizations must now ask themselves is: how do we position ourselves in a world where the private sector has expanded its training offer exponentially and is devoting enormous resources to exploring what will be the next step in this diversification movement?

Daniel Baril then addressed his audience directly, asking them if they had already perceived or felt the initial effects of this competition from the private sector. He warned against the idea that only people who are very comfortable with the Internet or online educational universes can benefit from this new offering. He took the example of the accessibility of DuoLingo, 2 with a free, fun version offering a large choice of languages, which has been designed for a wide range of audiences.

He concluded his presentation with the idea that the public sector - schools and universities, community organizations and more informal venues such as libraries and museums - must rise to the challenge of private provision. It must in turn create learning approaches and formulas capable of responding adequately to the needs and aspirations of people in learning mode. And it is with the knowledge that has been accumulated, with its own content, that the public sector will be able to develop this offer.

Written by Laurence Buenerd

Vienna Blum is an experiential learning designer with a great ability to elevate diverse groups through meaningful collaboration. She is a facilitator and a design coach with Management Savvy in Montreal, a consulting firm using the experiential learning approach and Kaospilot method to coach, train and accompany clients in their learning and changing journeys. Together with Donald Lurette, they once again took up the challenge of hosting this latest edition of the Forum. This is how she recalls her experience.

1

“The method is not revolutionary, but it’s now part of who I am” comments Vienna.

To Vienna, academic conferences, with a traditional format and an academic style, are easy to organize: you invite a few people to talk and loads of people to attend. They come; people sit & listen. Participants know what to expect and are more or less in cruise control. “That’s not what we did.” To her, this Forum was part of an uncomfortable process about change and learning. All participants were invited to experience that process through an experiential learning approach.1 “The method is not revolutionary, but it’s now part of who I am” comments Vienna.

A lot of prep work was done before the Forum. Vienna recalls listening to the committees about their work, and being told that, instead of simply presenting their activities and results, they wanted to consult with the community because they felt the need to validate the path they had taken before going further down. Things such as “Are these needs still alive?” or “Do we need more of that?” So, it was a real team effort to try to have a Forum as much participative as possible, with several types of exercises offered to the participants.

The first interactive activity was an impromptu networking the first night, when people were just arriving and having a cocktail. Vienna believes it gave the opportunity for people to begin the conversation with people that they don’t normally talk to, around topics that people don’t usually talk about when they’re just saying hi. She invited the guests to find someone in the room that they didn’t know that well, and instructed them to talk about something they were proud of from the past year in their organization, in a four-minute exchange. Then participants were instructed to find another person to share about a challenge that came up in the past year, and that they overcame. And finally, a last exchange with another person about learning acquired that same last year.

There were multiple goals: connecting with people, talking from the heart, talking about real stuff that was going to be the main topic during the Forum (a sort of priming), and connecting on a deeper level.

Vienna says she always enjoys how people get real, as it’s usually the most emotional things that come to mind when you have limited time and because it’s an instruction, even if participants are a bit embarrassed, they talk about real things, not about the weather. “I give people permission to talk about real things and to humbly brag a little bit. I love giving people permission to humbly brag and share what they’re proud of.” According to the participants’ feedback, it was a great opener.

A fish bowl is a setting where the panellists sit in a circle on the centre stage and the audience sits around2 . It was used before the final event, as all participants gathered at the centre to present the ideas resulting from the various activities that had taken place during the day. They did a wrap-up of what had happened during the consultation, and of what kind of new ideas, needs, insights, came up from the regions. Participants from the same regions had been invited to sit together and distribute roles among the group: animator, note taker, curiosity manager, etc. and to discuss what the priorities were for their region. All those topics were presented in the fish bowl.

On the final morning, the groups were asked to get back together and choose a single idea or project to be presented to all participants. This last activity took the shape of a Dragons’ Den-style session, with a representative of each regional group invited to pitch the group’s idea or project. This type of animation is based on a TV series, during which budding entrepreneurs get grilled by a set of “dragons” investors on air, before they decide to invest or not in their enterprise. The COFA’s team became the dragons, but with the purpose to listen to the regions’ needs or priorities and to briefly comment on them. Each group had 20 minutes to get ready with a pitch, and four minutes to present it to the dragons. Vienna really enjoyed seeing the process, which was to bring some structure to a very interactive process, and addressing COFA directly: “It wasn’t to pitch COFA to do some work, but pitch COFA to pay attention, or make a priority, or address a blind spot.”

Vienna is adamant any activity needs a landing. One example she gives is the presentation to the entire group of a single idea or tool chosen by each participating group or individuals, with suggestions on how to implement it or how it could respond to their needs. “It’s cool, fun and exciting, but if there’s no landing, participants won’t leave with anything concrete.” She highlights that a landing takes time, and that the entire Forum was a

2 The fishbowl principle is that the action takes place inside the bowl, while people on the periphery are there to listen. Those who wish to speak up can do so by taking a seat in the bowl. The discussion that takes place takes the form of a free, undirected conversation, to explore, deepen a subject or answer a question.

two-day event. “During a landing, you take the time to pause and say, now that we just had that cool experience, what was it like? What just happened? What did you feel? What did you observe? What happened inside you, around you? And then once that’s out, that’s the objective data, then we say, okay, so what does that mean? What does it mean that you felt that way? What does it mean to you? What conclusions are arising as a result of that experience?” In her experience, a landing can take five minutes, ten minutes or even three days, depending on the purpose. The “pitch party” that closed the forum was meant to help participants make sense of the day and to integrate it in the form of regional pitches. “That was how they were concretizing it” concludes Vienna.

The “pitch party” that closed the forum was meant to help participants make sense of the day and to integrate it in the form of regional pitches. “That was how they were concretizing it” concludes Vienna.

Vienna acknowledges that not everything was a great success. She tried to start a Conversation Café with talking sticks, where each group was to use the talking stick as a tool to practise active listening, during the workshop dedicated to newcomers: only the person holding the stick would talk, until they were done and would hand the stick to the next person. The intention was to illustrate the idea of listening better to be able to better respond to the needs of people coming from other countries. It didn’t really work, because ironically, no one was really listening to the instructions.

But it was one of the last activities of the day and Vienna recognizes they were trying to disrupt the system and that “there’s always some resistance when there’s change.” Her aim was to inspire participants or at least to let them know things can be done differently and she’s pleased with what was experienced. In her mind, the future educators will have to be adaptable, curious, and not afraid of trying new approaches, tools, etc.

To her, the funny thing is that there has never been so much feedback after a COFA Forum: it was either good, bad, lovely, all of it... She’s glad the hosting brought engagement and strong feelings that participants were willing to share and write about. While she may have hoped for more enthusiasm towards the activities, she remains optimistic that it gave them a glimpse of different ways of engaging and the attitudes needed to find joy in the new, albeit uncomfortable… as change is on the rise.

THE FOLLOWING IS A SUMMARY OF THE FEEDBACK RECEIVED FROM PARTICIPANTS ON THE FORUM’S THEME AND FACILITATION, TAKEN FROM THE FEEDBACK QUESTIONNAIRES RETURNED TO COFA.

The Forum’s activities and themes were designed to illustrate the theme “From a training culture to a learning culture”, with a participatory approach, a variable-geometry format and diversified activities. The Forum was to be a time and a place to experiment with situations of exploration and openness, to imagine or glimpse modes of operation better suited to a learning posture.

The COFA team wanted to avoid a classic Forum1 in which participants simply listened, more or less actively, to the speaker describing the universal, miraculous method that would enable them to meet the needs of each learner and their organization.

1

IN WHAT WAYS WILL YOU BE ABLE TO APPLY WHAT YOU’VE LEARNED IN THE FORUM TO YOUR

For several participants, the Forum was a moment of validation of their professional practices, which was seen as an encouragement.

For others, the Forum was an opportunity to be exposed to new ideas. These people intended to return to their teams with the motivation to integrate these ideas into their professional practices and share them with their colleagues. Programming and the use of digital badges were mentioned in particular.

For some others, what they learned at the Forum would need a little time to be assessed and assimilated, and eventually put to use. It was also mentioned several times that knowledge sharing and reflection would be key elements in integrating the learnings into future professional practices. Several people regretted not having been able to bring back concrete solutions or practical content.

HAS THE FORUM PROMPTED YOU TO EXPLORE FURTHER THE SHIFT FROM A TRAINING CULTURE TO A LEARNING CULTURE?

As with the first question, several participants felt that the Forum had reinforced certain practices already in place in their centres, or confirmed the relevance of their approaches. A significant number of participants felt that the Forum had provided an opportunity to explore further the shift towards a learning culture, with some specifically mentioning the importance of facilitating the development of skills rather than the mere transmission of knowledge. Some others again expressed regret that they had not heard more practical solutions or examples of successful partnerships.

In general, however, the Forum was recognized as an excellent venue for sharing ideas and networking, with reports of enriching interactions and exchanges on best practice. Overall, the Forum seems to have encouraged many participants to reflect and consider a move towards a learning culture. Many said they were motivated to put what they had experienced into practice on their return.

Written by Chantal Carrière

Just as we aim to develop the learner ’s multiple skills, we take a similar approach to developing organizations and their practitioners to meet their complex and varied needs.

The Competencies Framework for LBS practitioners attempts to address three main issues for the LBS network: recognizing the competencies of practitioners, enhancing the value of the LBS program and ensuring the sustainability of the network

• Recognizing practitioners’ competencies: the Competencies Framework recognizes the varied skills acquired by practitioners through life experience, prior learning and fieldwork. Given the lack of specific formal training in LBS, these professionals, who come from diverse backgrounds, deserve recognition for their unique expertise.

• Enhancing the value of the LBS program: reinforcing the perceived value of the training offered by the LBS program enables learners to better demonstrate their skills to potential employers.

• Ensuring the network’s viability: faced with the challenges of staff retention, the benchmark values the contribution made by employees, helping to stabilize the workforce and ensure the network’s viability.

“As employers, we recognize the need for a tool that will enable us to address these concerns. We see the Competencies Framework for LBS practitioners and COFA’s digital badges as an opportunity to address these issues.”

Louise Lalonde, Consultant, Former Director of the Moi j’apprends Centre

The Competencies Framework is first and foremost a skills framework that provides benchmarks for LBS organizations and aims to catalyze and structure the development of professional practices at individual, organizational and network levels:

The Competencies Framework plays a crucial role in the professional development of practitioners in the COFA Network, making them aware of the skills they possess and those that could be improved. It provides a structured framework for drawing up personalized development plans, enabling skills gaps to be bridged. This helps practitioners identify skills that need strengthening, and explore new opportunities for progression. By clarifying professional expectations and encouraging the acquisition of new skills, the Competencies Framework stimulates continuous learning, while guiding practitioners along their career paths.

For organizations in the COFA Network, the Competencies Framework facilitates internal skills management. It makes it easier to identify skills development needs, helping to establish

a culture of continuous learning. With a better understanding of existing skills and emerging needs, organizations can better structure their projects, allocate tasks and encourage internal mobility. This strengthens their agility to face future challenges and remain competitive. The Competencies Framework also helps with succession planning and improves recruitment processes by targeting candidates with the right skills.

Developing professional skills is a shared responsibility between individuals and organizations. While every practitioner must engage in continuous learning, it is up to organizations to create the right conditions for this development.

The Competencies Framework enhances the value of practitioners by clearly defining the skills required for each role, thus increasing their professional recognition. This clarification enables partners and government bodies to recognize the legitimacy of the COFA Network, reinforcing confidence in the quality of the services offered. In addition, the framework supports ongoing professional development, promotes recognition of prior learning and encourages strategic partnerships, thus contributing to an enriched service offering that is better adapted to community needs.

“ These initiatives will help strengthen the quality of the services offered by our centre and raise the standards of LBS as a whole. By having better trained and qualified professionals, we will be able to respond more effectively and efficiently to the needs of the beneficiaries of our services.”

Emma de Lanoy, Coordinator, Adult Employment and Training Services, La Clé.

In any organization, the ability to collaborate effectively is essential to achieving goals that cannot be achieved individually. This is particularly true in environments like those of COFA’s network members, where many tasks are carried out collectively. The development of collective skills thus becomes a central issue in strengthening cohesion within the organization.

Some complex tasks require the collaboration of several people with varied and complementary skills. Let’s take the example of a centre welcoming a learner from an underrepresented background. An adult educator, despite his or her specific skills, will not be able to meet all the learner’s needs on his or her own. A manager will step in to offer additional support, and it will often be necessary to call on external partners to accompany the learner on his or her journey. It is by combining these individual and collective skills that the organization can better achieve its objectives and offer a higher quality service.

Collective skills enable us to build shared knowledge and collaborate more effectively. Working collaboratively isn’t just about getting the job done, it’s also about learning from each other and strengthening the organization as a whole.

For these collective skills to develop, certain conditions must be met. Firstly, a culture of collaboration must be established within the organization. Each member must understand that his or her skills, while valuable, are only part of the total pool of available resources. The success of a complex task depends on the ability to pool these skills, share ideas and draw on a network of collaborators.

To support this development, communities of practice, for example, play a key role. These spaces enable professionals to meet people with different skills, learn new practices, and complete projects they wouldn’t have been able to accomplish on their own. These exchanges encourage the emergence of new skills, while enabling the organization to grow.

In a network made up of many small members, the pooling of skills becomes an essential lever for encouraging professionalization and dynamism. This collaborative dynamic creates the opportunity to maintain learning organizations, where each individual contributes to the enrichment of collective knowledge.

Sources :

• AFB Network Practitioner Competency Reference Guide: https://badges.coalition.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/GuideUtilisation-Referentiel-COFA-Mai2024-1.pdf

• CharityVillage Professional Development Guide : https://charityvillage.com/charityvillage-professional-development-guide/

• Recording of the discussion between Donald Lurette, Hervé Dignard and Gabrielle Lopez (September 2024), some of whose contents are presented in the article on page 20.

The Framework is structured around four key roles that define responsibilities within the LBS organizations:

• Training

• Design

• Management

• Administrative and Technological Support

Andragogical roles, such as training and design, are directly linked to adult learning. The training role involves direct accompaniment of learners to achieve their learning objectives, while the design role revolves around the development of projects adapted to the specific needs of certain clienteles.

Administrative roles, such as management and administrative support, ensure the smooth running of the organization. The management role focuses on the administration of human and material resources, as well as the implementation of action plans, while administrative and technological support provides technical and organizational assistance to all personnel.

Each role includes specific functions, and each function is associated with a set of specialized skills, specific to the LBS Network. These specialized skills are deployed in three levels of tasks, according to their complexity: simple, medium or advanced. Each task level is matched by typical activities, which illustrate in concrete terms the professional practices associated with these tasks.

Typical activities:

List issues regularly to the Board of Directors’ meetings.

2. Provide the information needed to support the Board of Directors in its decision-making.

3. Share with Board members the documents they need to make informed decisions.

g Ease of communication

g Ease of persuasion

g Organizational skills

g Sense of responsibility

1 https://icea.qc.ca/sites/icea.qc.ca/files/NCF_Referentiel-ICEA_septembre2018_0.pdf

2 https://www.canada.ca/en/services/jobs/training/initiatives/skills-success.html

Finally, the Competencies Framework is rounded off by a cross-cutting section common to all roles: professional development, essential for maintaining the continuous evolution of practitioners’ skills.

As part of the development of the Competencies Framework, each competency was associated with generic competencies from the ICÉA’s1 Framework, thus ensuring complementarity and consistency in the development of professional competencies. In addition, an exercise was carried out to align these competencies with the federal government’s Skills for Success Framework 2 . This approach aims to ensure that the competencies developed meet the standards, while responding to the specific needs of the literacy and basic skills sector.

Typical activities: 1. Experiment with adaptations of internal governance processes with the Board of Directors. 2. Study the best practices and solutions adopted by other organizations in similar contexts with the Board of Directors’ members.

g Ease of communication

g Ease of persuasion

g Sense of responsibility

Typical activities:

1. Analyze issues the organization is facing and explain or discuss them with the Board of Directors.

2. Assess opportunities and actions with the Board of Directors in a consultation or co-development session.

3. Develop program objectives and structure action plans and work plans, and share/review/validate them with the Board of Directors.

g Creativity

The full COFA reference document is available here:

18 Les badges numériques : reconnaissance formelle et vérifiable des compétences et des réalisations

Written by Chantal Carrière

To support the implementation of its Competencies Framework, COFA has set up a system of digital badges. Each badge represents one of the specialized competencies in the Competencies Framework. These badges are awarded on the basis of the evaluation of evidence files submitted by applicants. The application process, assessment criteria and validation stages have been designed to ensure that badges meet COFA’s high standards.

Digital badges offer a new way of recognizing and valuing skills acquired throughout life, particularly in non-formal learning contexts. This innovative system enables practitioners to receive official recognition of their achievements, while facilitating sharing and professional networking. Here’s how digital badges can play a key role in professional development and skills enhancement within the LBS network:

Official Recognition

Badges offer verifiable formal recognition of skills and achievements.

Lifelong Learning

They validate skills acquired through non-formal and informal learning.

Professional Development

Badges can recognize milestones and achievements in a career path.

Easy to Share

Badges can be easily shared online, on social networks, and integrated into digital CVs.

Networking

Thanks to COFA’s personalized space on the CanCred Passport Platform, members can build their professional profile online, exchange with other members of the COFA Network, and store all the digital badges they have earned, in line with Open Badges standards.

To find out more about this project and discover the COFA badges, visit: www.badges.coalition.ca

Some Statistics for the Period February to August 2024

150 + badges issued

50 members in the CanCred Passport area

Most popular badge: Digital Integration Advanced Complexity

99 badges now created

Watch the video presentation to find out how digital badges can help you on your career path!

“The digital badges project immediately struck me as a good tool in the LBS Network. As practitioners in this network, we acquire many professional skills over the years; sometimes in a non-formal context, other times in an informal one. Digital badges enable us to gain recognition for all our skills. It’s very rewarding! ”

Marie-Ève Vézina, Adult Educator, Centre Moi J’apprends, Hawkesbury

“Given that there is no diploma or credited certification to be recognized as an LBS Adult Educator, the digital badges allow me to showcase my experience acquired over the years and my professional background, transforming them into tangible proof.

It’s very motivating to get recognition for all the work you’ve done. The badges make it possible to break down the work done: planning lessons, creating materials and managing files. Our tasks are easy to spot in the Framework, and the badges available for each of them are already linked to it.”

Nancy Rivard, Trainer and Programming Officer, Programme de formation à distance (FAD)

Written by Laurence Buenerd

Have you ever wondered what skills are covered by the much-used term «SocialEmotional Skills», and how they relate to generic skills, or Skills for Success? We asked some experts to shed some light on the matter... This back-to-school discussion took place online in early September 2024, between Hervé Dignard, researcher at the Institut de coopération pour l’éducation des adultes (ICÉA), Donald Lurette, specialist and consultant in andragogy and regular contributor to COFA’s research activities, and Gabrielle Lopez, COFA’s Director.

Hervé, Donald and Gabrielle all agree that the term “SocialEmotional Skills” has been widely used for some time now, by various organizations and government agencies. Is it a buzz word? Donald mentions having heard of social skills, social and emotional skills, or Social-Emotional Skills. In his view, they have a lot in common, but are classified differently depending on the organization using them.

The skills grouped under these three headings are linked to relationships with others: communication, exchanges, interactions, adaptability, problem-solving, self-awareness, emotional management, etc. Skills that are not always immediately linked to employment situations. “It’s a wide universe, without well-defined boundaries”, says Hervé, which revolves around people’s personalities, the management of “self in relation to others”, emotions and so on. Donald appreciates this reclassification under the heading “social-emotional”, because it helps to differentiate them from other generic skills and clarifies their scope: “social” for relationships between oneself and others, and “emotional” for self-management and emotional aspects. What is now classified as Social-Emotional Skills, such as communication or collaboration, has always been seen as important, but was not categorized in this way. However, Hervé points out, definitions vary and are adapted by the different organizations that use them, depending on their objectives.

“What complicates matters, ” observes Donald, “is that a generic skill can be considered a professional skill when it is indispensable to a job. For example, the ability to communicate well, for someone in training, is an indispensable skill and will be part of their job description, whereas for other professional fields, it will be secondary. ”

Donald and Hervé agree that social-emotional skills are part of the generic competencies, but what’s important, Hervé believes, is the choice of competencies that appear in a competencies framework and their definition; what’s less important is to which large set they belong.

For Donald, learning these skills is also where the challenges lie. He points out that a person’s ability to adapt or collaborate well will be the result of past experiences, their family background, etc. There may be resistance to developing this type of skill, and in general, it will also require a group work context to achieve it. So there’s a whole set of elements required that are more complicated to implement than for learning a technical or even cognitive skill. This has pedagogical implications.

He cites the example of the pilot program in which he works with young carpentry apprentices: while it’s relatively straightforward to learn how to calculate the quantities of concrete needed to pour a foundation, it’s much less so to learn how to work together to erect a wall. Depending on the individual, there may be reluctance to work in a group for fear of others witnessing their mistakes, or because they’re afraid of conflict, or because they’re poor at communicating their needs. These are barriers to learning that are difficult to anticipate, since they will be specific to particular individuals. These types of learning are more time-consuming, since they take place in practice, and require more feedback than actual teaching, as well as different types of pedagogical support.

The idea of adapting the NCF tool for Aboriginal communities arose from a pilot project to create a competencies framework for carpenters, initiated by the First Nations Adult Education School Council (FNAESC) and based on the Ministry’s competencies framework, which lists 19 generic competencies related to this type of job. Donald used the ICÉA’s “Our Strong Competencies” “Nos compétences fortes” (NCF) framework1 to identify the generic competencies required that were not listed in the Ministry’s framework. Many of the students involved in the pilot project were members of aboriginal communities.

It is in this context that questions about the fit between generic skills and “ancestral knowledge”, “ancestral skills” or “ancestral teachings” have emerged. 2

The ICÉA was then approached by the First Nations Adult Education School Council (FNAESC) to launch another pilot project focused on the valorization and recognition of SocialEmotional Skills relevant to Aboriginal communities. It will involve a process of self-recognition and peer recognition of some of these skills, defined and named by the participating First Nations communities. It will be inspired by the principles and facilitation methods found in the NCF tool, which enables skills to be recognized within a group. Hervé is delighted that the tool performs well when groups are heterogeneous, as they should be in the participating communities. The tool created will then be tested before being validated. While it is possible to believe that the skills recognition process will be universal, what will be recognized is likely to vary from one community to another. In the end, the process put in place will enable to recognize different “soft skills” and different frames of reference to be used in different communities.

The project will take place in seven Quebec-based aboriginal communities, five French-speaking and two English-speaking, with researchers recruited and trained in each community. The communities were selected by the FNAESC with a view to ensuring diversity of context: French-speaking, Englishspeaking, urban, semi-urban or remote from major centres, and according to the interest aroused by the project in the communities approached.

The three objectives of the project are as follows:

• create a recognition tool;

• create meaningful frames of reference for different aboriginal communities in Quebec;

• link these competencies frameworks with the federal government’s Skills for Success.

This project grew out of the need to validate this approach to recognizing “soft skills”, rather than skills, a term that doesn’t necessarily make sense in these communities. An application for funding was submitted to and obtained from Employment and Social Development Canada. The project is in the start-up phase and should be completed around July 2025 or a little later. It should take the form of an action research project3 with a collaborative and cooperative perspective, in which those taking part will be considered co-researchers and will have a say in the direction the research takes.

1 See ICÉA’s Nos Compétences Fortes (NCF) Tool on page 23

2 They include, among others, the Seven Sacred Teachings that are the traditional values shared by Aboriginal communities: humility, honesty, respect, courage, wisdom, truth and love. Depending on the communities, these values are personified by an animal or a legendary character, but they are common to all of North America. The Legislative Assembly of Ontario has created a document that presents them: https://www.ola.org/sites/default/files/common/pdf/Seven%20Grandfather%20Teachings%20WEB%20Eng%20.pdf

3 According to Michèle Catroux, action research is a process designed to enable all participants to be active, consenting players in the research process. They are aware of all aspects of the research, and take part in the negotiation, observation and decision-making phases. See Michèle Catroux, “Introduction à la recherche-action : modalités d’une démarche théorique centrée sur la pratique”, Les cahiers de l’APLIUT [Online], Vol. XXI No 3 | 2002, accessed September 3, 2024 at URL: https://journals.openedition.org/cahiersapliut/4276?lang=en ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ apliut.4276

For Hervé, one of the biggest challenges of the project remains to coordinate seven different research fields and to train people within the communities to steer the projects, but also to take account of the variety of viewpoints from one community to another, and of this variety within a community itself. Donald mentions the example of the feelings of young members of the Mi’kmaq community in which he has worked, who are unsympathetic to the importance of the teachings of their community’s elders, perceiving them as too moralistic. At the same time, however, he points out that some of them have shown an interest in those elements of their culture with which they were unfamiliar. It will therefore be interesting to see how these divergent points of view can converge in the recognition of skills encompassing, at least in part, know-how derived from these “teachings”. For Hervé, the diversity of the people involved in the projects in the seven communities will be crucial to ensuring that the tool to be created is representative of the skills recognized and named, but it will also represent a challenge.

For Donald, identifying these skills is difficult. A person’s technical skills can be identified on the basis of experience: he or she has performed such and such a task in the past, and can therefore say that he or she possesses such and such a skill. On the other hand, people are not always aware of their own generic and social-emotional skills. It’s for this type of skill that a recognition process like the NCF tool is useful, because these skills can be difficult to recognize for oneself. Hervé mentions that the recognition stage can be akin to a prior learning identification process, as part of the start-up of a group project, for example, where it’s important to check that all members are starting from the same foundations, and to identify which skills might need strengthening.

He also points out that the NCF tool relies on the group to collectively validate the skills of each person present. In a learning context, he points out, “the prior identification of participants’ skills creates a positive climate conducive to learning”.

Social-Emotional Skills are not just the popular term of the moment, they have an important role to play in all projects, large or small, that require collaborative efforts.

In May 2021, the Skills for Success Office (of Employment and Social Development Canada) updated the «essential skills» competencies framework,4 whose framework had been defined in 2007 and which needed to be adapted to the new realities of the world of work. The revised skills were designed to better reflect the adaptation and navigation needs created by rapid changes in the job market and technologies. These nine competencies, grouped together in the "Skills for Success" framework, are those used by a person to perform a wide variety of everyday and professional tasks, and more broadly, to succeed in a professional, social and personal context. 5

4 Competencies frameworks identify and describe skills, and can define different skills depending on their purpose.

5 See the Spring 2022 issue of Perfectio “Pathways”: https://issuu.com/ cofa-fad/docs/edition_speciale_-_printemps_2022-en_web

Generic skills 6 differ from specific or technical skills, which are specific to a particular task or profession. They have taken on the name generic because they are applicable in different contexts, both professional and non-professional. Skills for Success, for example, lists creativity and innovation skills as being in demand by employers. These skills can be applied to a wide range of fields. Historically, explains Donald Lurette, when the “old Essential Skills” competencies framework was used to define what skills were needed to enter the job market, employers felt that certain skills were missing from the list, in particular those relating to “soft skills”, which are now referred to as Social-Emotional Skills. This shortcoming has been partly remedied by updating the framework.

Hervé Dignard mentions that he has done a great deal of work comparing the Skills for Success with some forty other frameworks, similar in purpose.7 He came to the conclusion that, although the skills identified are not always named or defined in the same way, they are nonetheless comparable.

Hervé Dignard gave a brief overview of the “Nos compétences fortes (NCF)” tool developed by ICÉA: it is used to recognize a person’s strengths and competencies, particularly generic. 8 It’s a way of valuing and recognizing people’s generic skills and strengths, which are mainly linked to their personality. The ICÉA Competencies Framework lists the competencies that were chosen in 2012, generic competencies that are easy to recognize and identify by people who didn’t always have a great deal of professional experience. It had its origins in an initial tool created in 1989 for women re-entering the job market after a career break. This first tool aimed to help them name the skills they possessed that would be meaningful to potential employers. Hervé explains that the NCF skills identification process and the ICÉA generic skills framework are complementary, but that they are two different tools.

6 On this subject, see the Autumn 2023 issue of Perfectio “Recognition”: https://issuu.com/cofa-fad/docs/perfectio-automne2023-reconnaissance-anglais-fa-we?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ

7 Dignard, Hervé (2023). Compétence génériques et compétences pour réussir : un exercice de comparaison, Apprendre + Agir, Édition 2023, Institut de coopération pour l’éducation des adultes (ICÉA). Online: https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/competences-generiques-et-competences-pour-reussir-un-exercice-de-comparaison

8 See the testimonial articles on pages 25-26 of the Autumn 2023 issue of Perfectio: https://issuu.com/cofa-fad/docs/perfectio-automne2023-reconnaissance-anglais-fa-we?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ

David Allen Kolb, born in 1939 in Illinois, is an American educational theorist whose work focused on learning styles, experiential learning, social change, career development and professional education. He is the founder of Experience Based Learning Systems (EBLS) and is also renowned for his Learning Style Inventory (LSI).

David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model is a framework that can transform the way to approach teaching and learning. At its core, Kolb’s model emphasizes learning through experience, a process that unfolds in four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. This cycle allows learners to engage deeply with material, reflect on their experiences, conceptualize new ideas, and apply their knowledge in real-world settings.

In a group of learners, this is how it could be illustrated:

• Concrete Experience: Encourage learners to dive into hands-on activities with a group project, a role-playing scenario, or a practical task, so they can be experiencing new situations. For instance, learners could be tasked with managing a small budget, an exercise linked with real-life financial literacy.

• Reflective Observation: After the activity, a discussion can be facilitated to encourage learners to contemplate what they’ve experienced, with questions like, “What went well?” or “What challenges did you face?” This reflection helps learners process their experiences and draw meaningful insights.

• Abstract Conceptualization: At this stage, learners can integrate their reflections into broader concepts. Theories or principles that relate to their experiences can be introduced,

such as discussing financial management strategies. This stage connects practical experiences with “academic” knowledge.

• Active Experimentation: Finally, learners can be encouraged to apply their new knowledge to different situations. They might create a personal budget plan or teach a budgeting workshop to peers. The aim of that experimentation is to reinforce learning and encourage continuous improvement.

Incorporating Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model into teaching practices helps to create a dynamic and engaging learning environment. This approach not only builds skills but also empowers learners to apply their knowledge more confidently in everyday life.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017), The experiential educator: Principles and practices of experiential learning. Experiencebased learning systems. EBLS Press, 594 pages.

An overview of the book is available here: https://learningfromexperience.com/books/the-experiential-educator-book-excerpt.pdf

These implications can be actively tested and guide learners in creating new experiences during AE. Here, the educator is a coach helping learners apply knowledge to achieve their goals in their learning context.

The educator is a facilitator. Immediate or concrete experiences occur, and they are the basis for observations and reflections.

Act, Do, Experience

Test your conclusions, develop a plan of ac tion

Look back and as sess what went well, not so well

Make sense of the experience, draw conclusions

Reflections are assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts from which new implications for action can be drawn. The teacher is the standard setter and evaluator, helping learners master the application of knowledge and skill in order to meet performance requirements.

The educator is the subject matter expert, leading the reflection by making relevant texts and lectures available, creating space and a framework for systematic analysis through reflective practice.

© Toronto Metropolitan University. Illustration is from: https://www.torontomu.ca/experiential-learning/faculty-staff/kolbs-el-cycle

by Simon Kavanagh

written by Laurence Buenerd

To Simon Kavanagh, Arch Design is “one of the best and simplest ways to visualize learning”, but it is also a method that is more engaging, transparent, autonomous, action-based, co-creative and transformational, in line with the human-centred Kaospilot pedagogy.1

The method creates and shares ownership and direction for the learning between learners, peers, near peers, teachers, facilitators and trainers. It bridges and stimulates the connections between subject, content, time, learning purpose, methods, and personal development through individual, group and team-wide learning.

1 Founded by Uffe Elbæk in 1991, Kaospilot is an education provider and facilitator of learning experiences for individuals, communities and organizations located in Aarhus, Denmark. It’s a hybrid business and design school with a curriculum divided into three domains: Project Design, Process Design and Business Design. The school provides full-time education and workshops. To learn more visit: www.kaospilot.dk

Simon Kananagh developed the method as he was developing a new curriculum for the Kaospilot’s three-year program. Based on Kaospilot Creative Leadership, he ended up with a visualized learning journey, managing equilibrium and integrating impact, value, subject, social, emotional, collaborative and creative competencies with personal craft and leadership. He realized a few years later that the learning arch method could be shared to all learning designers with a method to design curriculums and learning tools that increase the creativity, innovation, engagement and risk in education.

To Simon Kananagh, there’s an archaic “teach > learn > perform or test” learning style, sustained by old guards who are “change averse and held by procedures, policies, regulation, top-down control and ultimately a generational misalignment to the contemporary and emergent styles of learning.” The Learning arches exploit an “act > learn > adapt > repeat” learning style, which supports a more adaptive and collaborative self-efficacy and leadership model, aiming to educate and encourage the students to create their own future as reflective activists.

The Learning Arches (LAs) are a method to design transparent, collaborative and experiential learning journeys or processes that maximize engagement, capacity, ambition, ownership, confidence, relevance and most importantly, dialogue between the learners and hosts, facilitators, instructors or teachers as stakeholders of the learning.

It visually translates and interprets the curriculum into a learning journey. It provides a picture showing learning blocks, and stimulating the flow, the connection and continuity of learning, the challenge and growth towards mastery of any given topic, subject, discipline or craft.

The Learning Arches (LAs) provide a flexible structure, or learning scaffolding, but allow for more exploration and deviation from the plan, knowing that the participants and facilitators can return to them and land or check in at any point of the process. The Learning Arch Design Canvas (LADC) uses the 4Ds that are to define, design, deliver & discover, to frame a design process for developing and running learning journeys.

Above the horizontal axis of the timeline, each arch should represent a subject or module, taken from the curriculum, with proper label. The content to be delivered, explored, learned, experienced, taught & tested has to be specified. The focus above the timeline is on the known (content) skills, knowledge, methods, models, and theory.

The landing of the big course arch should also specify the learning objectives for the entire course. Mid arch intervals on the larger arches allow checking into progress, connection, alignment, satisfaction and understanding.

Under the timeline should be written the arches values, mindset, attitudes, and competencies the student would want to explore and grow. S. Kananagh refers to it as the Hidden curriculum, the unknown elements of the curriculum, unknown in the sense that most educators and learning designers, are unsure of how to design and measure authentic exercises that allow the participants to embody and reflect.

• Above the timeline: The ‘known’ skills & knowledge;

• Below the timeline: The ‘unknown’ attitudes, values, competencies and mindsets.

There should be a mix of high action (do): active experimentation, concrete experience & impact, and low action (think): evaluation, reflection, deeper analysis and theoretical understanding.

One of the 1st tips he gives is that the frames and learning culture need to be set and co-created with the students based on the first LA draft. Delivery of the curriculum should be done with transparency, alignment, commitment, clear frames and direction, using the arches as a guide or map.

The setting is the most important stage, according to him: it shows the stage, culture, tone and mood for the entire learning period, shares the learning agenda and inspires connection and ownership of the program and the shared learning agreement.

At the beginning of a unit of study, a diagnostic assessment is given to assess the skills, abilities, interests, experiences, levels of achievement or potential gaps & difficulties of an individual student or a whole class. It’s used to collect data on what students already know about the topic or what SK calls “to meet them where they are at.”

Holding Learning arches, means the hosting, facilitating and leading of the learning experience and the learning space both inside the arches and between them.

Holding happens during the setting and landing, as an arc is created, the learning arch, and in the space created inside, the learning space. Whilst holding, the LAs are the framework or scaffolding to support the transition from safety of content and structure to exploration and emergence. Holding is facilitating, leading and hosting but also pausing, observing, questioning, measuring, reacting and adapting in service of the learning, task and purpose.

A formative assessment (during the holding) aims to determine how students are progressing through a certain learning goal/arch or journey. Through individual, group and team performance, observation and guidance during the learning process, a concurrent record of the students understanding, achievement & engagement is created. Here are some of the questions that can help that assessment: What are we learning & discovering about the content & ourselves? What do you know, understand and can do?

Landing a Learning Arch is a key moment in any learning process. It’s generally a time to relax, look back, a time to assess and evaluate skills and knowledge but also on an attitudinal and mindset level. Students should be allowed during the landing to feed forward their learning, get on the same page, explore what more they’d like to learn, or make connections to help understand the importance of what they have just acquired and learned. It’s also a time to reconnect with the bigger purpose.

Landing an arch always needs to be done in order to complete the phase of learning before starting the next arch. The longer the arch, the longer it takes to land.

A summative assessment (during the landing) aims to evaluate the student learning at the end of an instructional unit by comparing it against some standard or benchmark. Some examples of summative assessments include: a mid-arch or final exam, final projects & well-framed reflection and evaluation to feed forward learning and feedback to the learning journey. The purpose is not only to show the students’ subject & knowledge competencies, but also their change & ability to create sustainable impact & value.

Landing is a reflective action that works on two levels:

• Allowing the students to self and peer assess their performance, the process, the methods, the delivery of content, etc.

• Referring to the theory and encouraging the students to analyze what they know and what they need to know more of. All students have to have reached a desired level of understanding and clarity before moving on to another arch.

The level of engagement, ambition, autonomy and intervention of the students’ needs to be monitored through the entire LA. Based on their capacity, disturbances can be applied in the arch to move them into the right frame of mind for the lesson or arch.

Five types of disturbances can be planned at certain points by design or delivered when needed:

• Creative: Increase creativity, sustain divergent thinking, innovation, inspiration, expectations, critical thinking & deliverables. That type of disturbance creates energy.

• Knowledge: Small doses of knowledge, methods or theory delivered at a time where it is most relevant and useful. That type of disturbance works very well in webinars.

«The Learning Arches are primarily a method to design transparent, collaborative and experiential learning journeys or processes that maximize engagement, capacity, ambition, ownership, confidence, relevance and most importantly, dialogue between the learners and hosts, facilitators, instructors or teachers as stakeholders of the learning.

Every student deserves to know at the beginning of any learning period, why they are there, what they are going to do and how they are going to do it.

The purpose of the Learning Arch method is to increase the bandwidth for risk, engagement, creativity and innovation in new and existing curricula and programs.

For me, it’s [the Learning Arches that are] the most effective method for defining, designing, delivering and discovering learning journeys and programs of any duration and for any age or target group. Using LAs, we design highly effective learning journeys where the pursuit of skills, knowledge, attitudes and values are unfolded, unpackaged, discovered and embodied.

Landing a Learning Arch is the time when we come back as a team or class of students and learners to make explicit the success and failures when applying a particular skill set, method or theory.

We do not learn from experience... we learn from reflecting on experience.

John Dewey

• Activate (the literature): The reading material that accompanies a course or programme needs to be activated, or brought alive by creating opportunities & tasks to apply and discuss using forums & breakout sessions.

• Hotspots: A hotspot (HS) is an intervention designed to personally challenge and grow the students and the team/ class, to deal with diversity, assumptions, conflict, complexity, etc. HS’s are not shown in the Learning Arches. They can be supported by breakout group sessions for problem solving, motivation, teamwork, moral & conflict resolution!

2 SKAV: Skills, Knowledge, Attitudes & Values.

Revisit Learning (SKAV): If the SKAV2 & content, theory and methods are powerful and relevant, they should be revisited, but within more challenging contexts that require a higher level of understanding and application. That type of disturbance supports different learning styles, risk, assessment & growth.

To learn more read this article about the Learning Arches.

Simon Kavanagh’s Biography

It was during his studies in Art & Design from the Dublin’s National College of Art & Design (a joint degree incorporating three years of Visual Communication) that Simon first found the need to challenge educational norms by making art relevant to students, especially those from social and economically challenged communities. He received his degree in 1996, at the age of 21.

He then successfully started working in the Irish Multimedia Industry, becoming in 2001 a consultant for Windmill Lane Studios in the areas of interactive Television, Content Management and Educational Systems. After a move to Paris to further his career in digital media and art, Simon re-embarked on the educational path in Shanghai to lead the BA Faculty of Visual Communications for a British degree in new media, design and culture.

But it’s at Kaospilot that he was able to thoroughly explore alternative approaches to education and pedagogy. He is the Program director of the Kaospilot Learning Design Agency 3 and creator of the Learning Arch Method, as well as one of its licenced “pilots” and gives workshops4 on a regular basis in Aarhus, Denmark, where he lives and works.

3 www.kaospilot.dk

4 https://www.kaospilot.dk/product/designing-and-facilitating-learning-spaces/

Simon Kavanagh is the Program Director of the Kaospilot Learning Design Agency1 and the creator of the Learning Arches Design method. He lives and works in Aarhus, Denmark, where the school was founded, and was happy to comment on the whys and wherefores of his Learning Arches.

Simon Kanavagh has been part of Kaospilot for the last 17 years. Kaospilot is an international school founded in 1991 in Aarhus, Denmark, that provides full-time programs, professional programs and consulting services in creative leadership & meaningful entrepreneurship. 2

He was the first English-speaking member of staff hired when the school decided to broaden its scope outside Scandinavia, partly to reduce its dependency from the Danish government. Team Leader for a few years, he became Head Master and was tasked to create a curriculum that would be ready for accreditation.

He dived into the heart of the school’s activities, did a lot of research and tried to organize on paper how the teachings were carried out. He realized that nobody had ever tried to measure the students’ intrapersonal and interpersonal development and transformational learning journey, their values, mindsets, attitudes and behaviours. He also worked on finding a way to measure the level of challenges the students were facing every semester. As he started feeding those elements in Excel, it created graphics that looked like “insane roller coaster rides”. Simon recalls it was the first visualization of their learning journey. This first step helped him better understand how things worked. The roller coaster rides were taped into a methodology called Coactive coaching and became the Learning Arches3 .

1 Founded by Uffe Elbæk in 1991, Kaospilot is an international school providing education in creative leadership & meaningful entrepreneurship located in Aarhus, Denmark. It’s a hybrid business and design school with a curriculum divided into three domains: Project Design, Process Design and Business Design. The school provides full-time education, workshops and consulting services to individuals, communities and organizations. More information at www.kaospilot.dk

2 See above.

3 See the article “A summary of Learning Arch Design” on page 26

It led to some of the fundamentals of the school such as meeting the students where they’re at, explore context before content, experience before explanation, practice before theory, balance high action/low action, introduce complexity... all the things they already did naturally in the classrooms.

Simon considers the Learning Arches Design method to be something like the “Java of learning”. Once it was articulated, he thought of codifying it, sharing it and allowing people to hack it. The team collectively decided to go open source, packaged it, created resources and started offering training programs on how to use it. Today, the school offers 3-day master classes on the Learning Arches Design, and 12 licensees, working in 10 different languages, also provide Learning Arches Design training and master classes outside of Scandinavia.4 As they’re trying to become a regenerative school, licensing has become more important as it reduces the transportation of attendees. They also now offer online training on leadership and learning arches, mostly to give access to developing countries.

“At the beginning of any training, either with kids or adults”, explains Simon, “you need to set a safe space and to learn about the student, what triggers them, especially in the age of neurodiversity, what their interests are, or their learning styles.” Those periods of time help teachers or hosts to find out what would be the best way to teach the students. “For instance, there’s always a percentage that learn better while using their hands, comments Simon. Once you find out, you want to create the space, the condition, the culture, and the connection. It can be applied to all learning contexts.”

To Simon, all learners deserve to have a visualization of their learning journey in order to gain ownership. He believes the Learning Arches (LAs) can support teachers doing it intuitively with a lack of methodology, frame, etc. He says that during workshops, some teachers realize they already thought that way. To him, the LAs help them understand how it works, why it works, and to visualize what they’re doing and how they do it. He gets calls and messages all the time from people telling him that the Learning Arches method supports their work, brings consolidation to it.

Simon explains that when setting the arches, the bigger arch helps students to learn how to learn. In the average classroom, he observes, when teachers are teaching, they never reach to the higher arches, to reconnect with the purpose of what they’re doing. “The Learning Arches with their mid-arch points, allow for that reflection, they remind teachers about the intention & purpose.”

He asserts that a certain level of transparency needs to be created between teachers and students. To him, the LAs at the basic level are just a visualization over time of the learning and how it enfolds. It benefits both teachers and students.

As described in the Learning Arch Design booklet, the Learning Arches balance two tracks: One is above the axis, it’s the theories & methods. Simon sees it as a more “masculine” area. Under the axis are the soft skills and attitudes, which he considers more “feminine”. Simon believes that attitudes and mindsets are equally important as skills and knowledge, so when he designs a curriculum, that equal importance is the first stake. He then adds Activities, along with tasks or projects challenging enough to practice the skills, apply the knowledge and really embody the attitudes and mindsets.

Simon points out that students are considered as co-learners and young professionals at KaosPilot. When they are first asked to give some feedback on their learning, recounts Simon, they get stressed as they’re not used to it. “But it’s important to have their opinion on what they’d like to have more or less different things, such as peer-to-peer activities, theory, etc.” Because, he explains, doing that verification at the end of the year won’t give it a chance to implement changes. It’s also what the landing of the arches is used for: it brings some ownership to the students. “It’s their journey,” comments Simon.

How to assess the growth of the students, their learning? Simon deems skills and knowledge are easy to assess: “We’ve been doing it for centuries and it can be very summative.” He explains that the landing of a Learning Arch is a period dedicated to exploring how to land and reflecting on authentic levels. He states that it’s during that arch landing that the teacher or facilitator can see all interest, beliefs, assumptions, biases, ambition, etc. of the students. And he points out that there is always an arch landing before starting a new one.

4 Vienna Blum, who hosted the 2024 Edition of the COFA Forum, is one of these licensees, working as a facilitator and design coach with Management Savvy in Montreal. She is also interviewed in this issue on page 9

Simon suggests that behind all resistance are unmet personal, social or professional needs. He points out that “when trying to implement changes, if you push with a recommendation, for example, you will most certainly get a push back. Part of the training we provide is to always, always ignore your first impulse.”

He believes that as a teacher, one has to allow oneself a certain level of vulnerability, but recognizes it can be difficult: “Some teachers feel that if they give students ownership and autonomy, they might not get control back. Teachers aren’t trained to assess emotional connections, and it’s harder than it used to be because of the neurodiversity in the classes.” He acknowledges that some teachers end up reading from a script because they don’t want to go through any conflict.

Simon states that “When you set the arches, you have to plan on creating connections, between you and the students, among the students, the students and the content, to create passion and a will for lifelong learning.” He notes that the average teaching culture does not aim on creating more autonomy in the students. To him, teachers need to create their own pack and that they have a duty to “package” the pursuit of knowledge, even in gamifying it.

Simon mentions they are in the process of licensing a partner in Vancouver, so in Canada, they should have licensees in Montreal and Vancouver. He’d love to give some workshops in Ontario but it hasn’t happened yet for a variety of reasons. 5 LinkedIn

He also explains they use LAs for their internal consultancy activities (30% of the school activities), and to attract new clients. They’re currently working on creating LAs that focus equally in the in-between training periods, to hold the space and practise a “due-care” style of consultancy and systemic support. Clients who only have resources to buy a limited amount of training would then benefit from extended training programs. Their plan is to build more internal ownership of the processes in between workshops. LinkedIn Learning5 allows the school to curate some existing content on that platform to support continuous learning tracks during those periods.

According to Simon, KaosPilot is growing with several companies and organizations because they are coming to realize their future is based on culture. He emphasizes: “not money, not finance, not sales. We help them build systemic authentic cultures as they come from very transactional mechanistic.” He notes that education has a very transactional background6 , and that teaching is a very transactional and functional system. Yet, “transactional hates creativity. It follows steps but emerging needs are ignored, there’s no adaptation.”

He believes that creativity is one of the elements LAs brings, and that they bring it strategically. He takes the example of consultation and point out that the majority of consultants do some training in the organizations, but without a bigger picture or purpose, and also, that consultation should be aiming for the good of the organization. Consequently, the solutions envisaged must have a cause-and-effect relationship for the people in the system, otherwise the changes will never be implemented. Simon thinks of the Learning Arches as the backbone of the strategic development they are doing.

And he wonders: “What if learning design is an art-based time form, just like film is?” To him, learning design is a major craft in the design field, but it doesn’t get the respect it deserves.

Creative, Technology and Certifications. It provides credentials including certifications, continuing education units, and academic credits. https://learning.linkedin.com/product-overview

6 Education can be seen as a structured approach with clear rewards and sanctions linked to student performance.

The LAs allow for a visualization of the learning journey (or “adventure”) and how and why the hidden curriculum will be brought to life;

02 They support dialogue, transparency, meaning & ownership of the learning;

They offer a way to unpack learning, action and knowledge, and to balance the pedagogical compass;

Complexity should increase over time, and learners should always get a second chance to practise, in the cycle Act-Learn-Adapt-Repeat;

The setting of the arches should meet the learners “where they’re at” and adjust the learning ambition, level and style to their level;

The launch of any learning cycle should start with a call to adventure (with excitement and relevance) and the connection, conditions & context before content;

The holding of an arch should always balance frustration and breakthroughs, and reward it;