CODEX

Het nieuwe nummer van CODEX Historiae draait helemaal om Labour! In de geest van de Maand van de Geschiedenis, die dit jaar het thema ‘aan het werk’ droeg, sluiten de redactie en onze gastschrijvers de maand af met en van onze dikste nummers ooit. Zo wat was dat een werk! Maar het resultaat mag er zijn; we weten immers waarvoor we het doen. CODEX is er voor studenten om hen te helpen hun schrijfvaardigheden te verbeteren en om ervaring op te doen met redactiewerk. Wellicht is dat de reden dat de redactie in de eerste twee maanden van dit academisch jaar al is gegroeid van acht redacteuren, waarvan een aantal reeds was afgestudeerd, naar twaalf redacteuren, die met een frisse blik het werk voort kunnen zetten. Ik ben dan ook blij om mee te kunnen delen dat CODEX officieel de coronacrisis heeft overleefd en dat zo spoedig mogelijk alle oude nummers worden gedrukt!

Genoeg over het werk van de redactie – verdiep je in dit nummer in de werken van de auteurs over onder andere verzet tegen en de afschaffing van slavernij, de inspanningen van arbeidersbewegingen, de werken van Herakles en nog veel meer! ‘Op de VU’ staat dit keer vol met updates van de studievereniging Merlijn en de facultaire studentenraad, evenals een interview met Jaap-Jan Flinterman, die helaas de VU heeft verlaten. We hebben weer een research update, dit keer over de Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations aan het IISG en een volle rubriek met reviews. Geniet van het lezen en pluk te vruchten van onze arbeid.

Helaas is het voor mij tijd om de taak van hoofdredacteur over te dragen aan iemand anders die CODEX met nieuwe inzet en creativiteit voort kan zetten. Ik wil de redactie en al onze gastschrijvers van het afgelopen jaar bedanken voor hun bijdragen, inzet en betrokkenheid.

CODEX is er om studenten ervaring te bieden met het publiceren van artikelen en om hun vaardigheden te helpen verscherpen. Heb jij iets geschreven voor een vak of ben je geïnteresseerd om iets nieuws te schrijven voor het volgende nummer? Twijfel niet, stuur het naar ons op!

This latest issue of CODEX Historiae is all about Labour! In the spirit of the Dutch Month of History, which was about the theme ‘aan het werk’, we’re closing off the month with one of our thickest issues yet. That was a lot of work! But we’re proud of what we’ve accomplished and we know what we’ve worked for. CODEX exists to help students improve their writing and to offer students experience in editorial work. Perhaps that is the reason the editorial board has grown the last two months, from eight members –some of whom had already graduated – to twelve editors who can continue the periodical with a new perspective. I’m happy to announce that CODEX has survived the corona-crisis and all issues published in the COVID-period will be printed as soon as possible!

Enough about the editors’ work. Immerse yourself in the results of the authors’ labours. They have written about resistance against slavery and abolitionism, about the works of labour unions, the labours of Herakles, and much more! ‘Op de VU’ is full of updates from Merlijn and the faculty student council, as well as an interview with Jaap-Jan Flinterman, who has sadly left the VU.This time, the research update is about the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, a project centered at the IISH, and we have a full section on reviews. Enjoy, and feed your intellect on the fruits of our labour.

Unfortunately, it’s come time for me to pass the mantle of chief editor to another, who can lead CODEX with new vigour and creativity. I want to express my deep gratitude to the editors and guest writers for last year’s involvement and commitment to CODEX.

Like I said, CODEX exists to offer students experience in publishing articles and improve their skills. Have you written anything for a course or are you interested in writing anything new? Don’t hesitate to send it to us!

The deadline for the next issue, ‘Frontiers’, is the 5th of December

De deadline voor het volgende nummer, ‘Frontiers’, is 5 december

Een

De

Life exists by evaluating and purposely ordering its environment and its interior ‘self’. Therefore, life can never be without such emergent properties as value or purpose. It cannot be meaningless because meaning is the primary product of its labour. These comforting thoughts brightened my mind after I had entered a dark place, having just lost my job as a computer programmer due to a lasting hand injury. My limbs felt crushed under the weight of the world, but philosophizing cushioned my despair. Above all, this experience taught me the relationship between selfworth and our ability to perform ‘valuable’ labour – valuable for self-sustainment, self-development or, more holistically, contributing to the betterment of society at large. Why use this story as an introduction to the labours of the mighty Heracles? Because the labours of Heracles are the quintessential story about the ‘hero’ toiling to regain his place in the world, out of the madness and into the light. While the eyes are the path to the soul, stories travel deeper than that. They relate to the universal and explore what it means to be ‘human’1 – something that I’ve theorized in my introduction relates directly to their ‘labour’. The labours of the mightiest of heroes – Heracles – spanned and mesmerized the ancient Hellenistic world and they can still inspire and resonate with readers today. In this article I aim to explore the basic narrative of his labours for readers unfamiliar with the source material, all the while pondering on ‘the labouring human’, morality, and the meaning of life.

However, some minor caveats are in order: there is not enough space in this article to explore the myths in their entirety, nor was there always a fixed canon for the ancient stories;2 there are many variations on each of the myths, with different happenings, written or compiled for varying purposes throughout the ages – many of which scholars can only speculate at. Classical writers have tried to find allegorical interpretations in the myths or endeavoured to rationalize historical events out of them.3 My analyses equally amount to speculation – they are projections from a twenty-first century reader, who is searching for meaning. To sum it up, the labours of Heracles are complex and universally explicable, yet incredibly inviting.

Birth of a Hero4

Zeus, king of the gods, wished to create a hero who could protect both the realm of the gods and the realm of mortals. Therefore, this hero had to be part human, part divine.Through

an act of deception, Zeus tricked a faithful mortal woman, Alcmene, into labouring him this semi-divine child.The goddess Hera, Zeus’s wife, was rightfully furious when she found out about Zeus’s adultery, so much so that she hated Heracles even before he was born, sealing his bitter fate. Heracles would spend most of his life combatting terrible monsters sent at him by her. The first of these hardships occurred when Heracles was still an innocent baby snoozing in his crib: Hera spawned two deadly snakes to end his puny existence, but the divine prodigy dispatched them both at once. While Heracles survived the incident, ordinary humans could not look at him the same way ever since. His divine strength proved to be a double-edged sword requiring great responsibility from its wielder, and he often caused grief for his surroundings. In his youth, for example, Heracles was said to have killed his music teacher, Linus, by bashing his head with a lyre.5 Because he was different – both an aide and a threat – he had to work harder to be accepted by society.

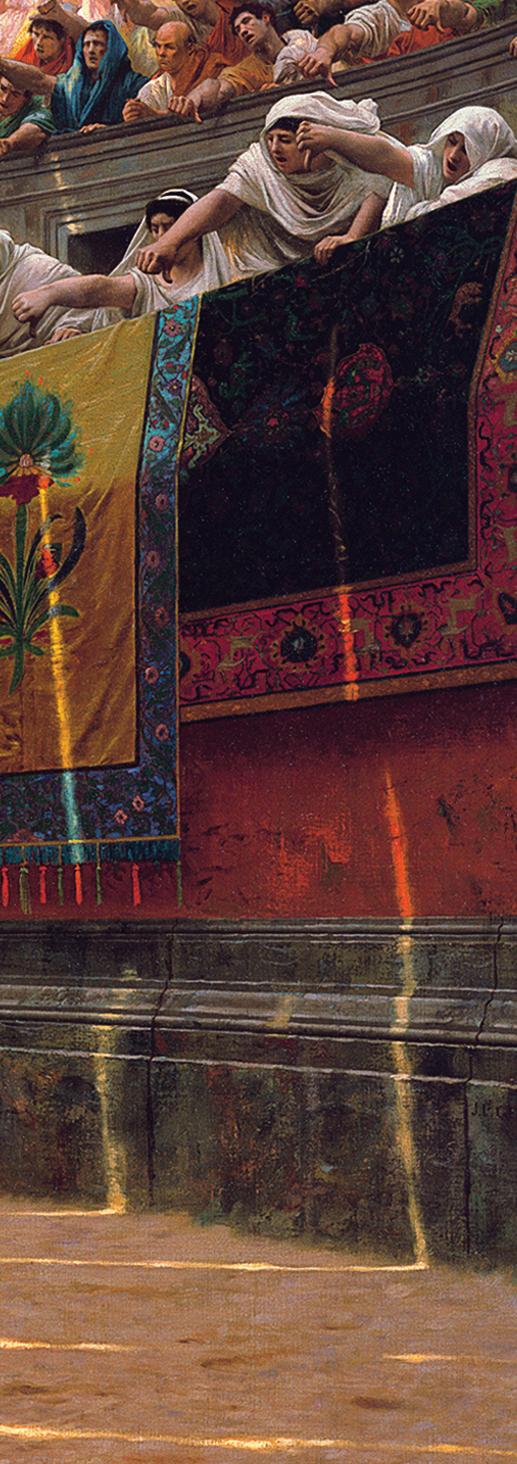

(I) Sarcophagus with the Labours of Heracles.

As an adult, Heracles seemed to have his life in order, leading a happy family life with his wife and children, but Hera could not let him be in peace. The goddess caused a fit of raging madness in the hero, causing Heracles to kill his wife and children, mistaking them for trespassing adversaries.6 In the most wellknown version of the myth, Heracles performed his twelve labours as penance for his tragical deeds, under supervision of the weaselly king Eurystheus. This penance can be understood as an attempt to regain his place in society and to regain his value as a human being through ‘enduring his crucible’. But these difficult labours also sent him off to far-away places, temporarily freeing the civilized world from this ‘double-edged sword’.

Euripides’s play ‘Herakles’ shows the mighty hero contemplating suicide before choosing a life akin to Sisyphus, the mythical Greek king who was cursed to roll a boulder up the mountain for all eternity. The writer therein contrasted loss of hope with loss of honour, the two main reasons for male suicide in ancient Greece. Heracles chose life over honourless death and his famous trials ensued.7

The familiar Disney-image of Heracles is Heracles the warrior with super-human strength. While he does put his Olympian physique to proper use, king Eurystheus’s labours – often making use of monsters raised by Hera – seem purposely designed to require copious cunning and ample adaptation. If your hands falter, use your mental strength instead – a challenge Heracles picked up triumphantly. Heracles trapped the terrible Nemean Lion in a cave. The lion wore an impenetrable fur coat for armour, so Heracles’s weapons were useless against it. Therefore, Hera-cles smartly choked it to death with his bare hands. The Lernaean Hydra’s heads, which grew back twofold with each one chopped off, Heracles scor-ched with a torch to stop their regenerative power, tackling one problem at a time. This teaches us that there is always a way, that we must not falter. The Erymanthian Boar had to be brought back alive on the orders of king Eurystheus, requiring Heracles to immobilize the beast in a deep pack of snow. And the Augean Stables, unceasingly dung-filled, were cleaned by Heracles through

redirecting the rivers Alpheus and Peneus, washing out the foul-reeking halls.8 In short, many labours required him to think outside the box, making Heracles a symbol of resilience and adaptation, reflecting both the human spirit and nature’s ingenuity. As Heraclitus put it, we “must not suppose that he attained such power in those days as a result of his physical strength. Rather, he was a man of intellect, an initiate in heavenly wisdom, who, as it were, shed light on philosophy, which had been hidden in deep darkness.”9

Originally, Heracles was meant to complete ten labours for king Eurystheus, but the weaselly king added two more chores when he found arguments to disqualify sev-eral of Heracles’s attempts; when cleaning the Augean Stables, the overly proud Heracles had asked for payment because the stench was too rough even for his sturdy nose, and Heracles failed the labour of the Hydra because he had received help from his nephew. Heracles was sup-posed to work alone, and only for penance and the promise of immortality. While Heracles is known to be a lonesome adventurer, he could not have overcome many of these obstacles without receiving some much-needed assistance. Among others, the goddess Athena, Heracles’s halfsister, secretly worked to alter his course towards success throughout the labours. When Heracles was stuck in a rut during the labour of the Stymphalian Birds for instance, Athena provided him with a special rattle that expelled the birds hiding in the fog, making them easier targets. Furthermore, during the labour of the Girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyte, Heracles had successfully bargained to cooperate with the queen to obtain her warrior-belt peacefully, but Hera once more sowed her seeds of distrust. After a brutal fight with the Amazons, Heracles returned to king Eurystheus and his daughter Admete, who had greedily desired the belt, and presented a ‘stained’ girdle.10

Immanuel Kant wrote that “Man has an inclination to associate with others … But he also has a strong propensity to isolate himself from others … to have everything go according to his own wish.” He also wrote that “Man … if he lives among others of his kind, requires a master.” 11 The maverick Heracles could not escape the necessity of cooperation; this constant struggle hides a Kantian reflection of human progress. He laboured in the service of lesser men, under the guidance of his allies, and contributed to society while striving for his own redemption and glory. Like any other, Heracles needed a master to provide him with a purpose for his power – a fact vehemently repudiated by the man himself. In Euripides’s play it was, in part, his denunciation of the gods which steered him towards life.12

The relationship between Heracles and his main adversary, the goddess Hera, is perhaps the most intriguing paradox in the myths, for without her challenges and scheming Heracles would not have been a renowned hero. Heracles’s great-ness and his

struggle, and therefore Heracles and Hera, are intimately connected. Zeus might have pro-duced a talented hero by tricking Alcmene into pregnancy, but Hera made Heracles live up to his potential, showing that talent alone is not enough and must be complemented by blood, sweat and tears. It therefore seems fitting that Heracles’s name means ‘Glo-ry of Hera’.13

In some versions of the myth, at the end of the story, Hera and Heracles set aside their differ-ences, as if suggesting that in the end we must embrace our hardships because they make us stronger. Quite literally in fact, as Heracles upgrades himself like a video game character during several of his ‘quests’. During the labour of the Cattle of Geryon, Heracles courageously defied the sun god, Helios, by shooting an arrow at the scorching sun, and Helios rewarded his spirit by handing him the golden cup, a magical device used by Heracles to travel the oceans. Furthermore, his iconic impenetrable lion-headed robe was acquired after stripping it off the Nemean Lion, and defeating the Hydra provided Heracles with arrows drenched in the serpent’s fiery, venomous blood. What comes to mind is a popular phrase meant to encourage responsibility and endurance in labour: what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. But this phrase can be equally interpreted as a disguised threat – be mindful of unwittingly making your foes more fearsome.

In his search for penance Heracles’s development as a character again paints a contrasting picture because he repeatedly makes the same mistakes. During the labour of the Erymanthian Boar, Heracles ends up sparking an unnecessary brawl against an aggressive troupe of centaurs. He does not just kill many of his hooved assailants, but two of his friends as well, one of which had been his teacher, the centaur Chiron; a recurring theme of ‘killing the teacher’ unfolds. Heracles was a beloved hero to the ancients, but for many ancient philosophers he was as much an example of how not to be. An aggressor of a past age, deeply barbarian in nature; 14 a redeyed Cretan bull on a stampede. Moreover, after completing the twelve labours, Heracles would enter another set of humiliating labours, this time in servitude to Queen Omphale, as penance for yet another passionate

murder. This image contrasts deeply with another aspect of Heracles for which he was known all around the Mediterranean: his role as a civilizer, a shaper of culture. He founded many cities and initiated the Olympic games. As judge, jury and executioner, he cleared the roads of violent bandits and made them safe for travel. He brought order in a world of chaos and he fought besides the gods to best the titans. Heracles the ‘culture hero’ tamed the forces of nature,15 irrigated the land,16 and therein embodies life itself by purposely ordering his surroundings.

At first glance, what seems to be missing is the development of the ‘interior’ self. We might have to look at the road towards his apotheosis for a glimpse of character development. Heracles performed his labours for penance, but he was also promised immortality after completing his task by his father, Zeus. Unlike the Mesopotamian hero Gilgamesh, who reaches immortality in name only, Heracles would ascend to Olympus after death. His last two labours prepared the way by sending him beyond the realm of the living. To pluck the apples of the Hesperides, Heracles travelled to a utopian garden. However, no mortal could grasp the apples, so Heracles – still part mortal – had to trick Atlas, bearer of the heavens, into collecting them for him;17 those last few yards towards the goal really are the hardest. For his last of the twelve labours, Heracles descended into the underworld to steal the guard dog Cerberus from Hades. Heracles once more trotted closer towards his death. Ironically, his eventual death would come at the hands of a loved one. Nessus, a centaur survivor from the earlier brawl with Heracles, tricked Heracles’s new wife Deianeira into poisoning her husband using the familiar poisoned Hydra blood. However, Zeus granted Heracles immortality and let him ascend to Olympus. From beginning to end, fate had determined Heracles’s lot, but he earned his divinity by his own hard work. He finally turned over a new leaf, so to speak, perhaps symbolizing that when we truly change, a part of us must die in the process.

Heracles’s death belies a sense of ‘you get what you give’. Both his good and bad deeds repaid him in the end – he earned his divinity by working hard, but his agonizing death was equally of his own making. Heracles could have known this – during the labour of the Mares of Diomedes he had fed the murderous tyrant king Diomedes to his own flesh-eating mares, the foul taste forever curing the mares’ taste for human flesh.18 Therefore, Heracles must have understood the concept of reciprocity.

Heracles has shown that hard work and overcoming hardship leads to glory. The goddess Hera unintentionally set him on a

course to improve the human condition by sharpening his blades. Paradoxically, the price to pay for his growth was an unspeakable sacrifice: the lives of his loved ones. Perhaps in life there is no giving without taking. However, this reality did not prevent the exemplary hero from pursuing his destiny. As in the labour of the Cerynean Hind, Heracles constantly ran after the unreachable and succeeded in seizing it, expanding his frontiers. Moreover, his mistakes became opportunities to improve his ways through labouring; this is the way humans grow. Like Heracles, life might be chasing immortality, but Heracles never struggled merely for survival; his labours sought to regain a purposeful existence. Moreover, he demonstrates that the path of penance is nobler and ever more fruitful than a life captured by vengeance. Heracles – a hero the ancients often thought more suited for comedy than tragedy19 – remains a well of deep resounding meaning today. Above all, Heracles embodies the purpose of life: shaping meaning out of matter, or in more poetic terms, finding beauty in tragedy.

1 Aristotle, Poetics. Stephen Halliwell ed., (Cambridge-Londen 1995) 59.

2 Daniel Ogden, ‘Introduction’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) xxi-xxxi, there xxviii-xxx.

3 For an introduction into allegory and rationalization of the Heracles myths see: Greta Hawes, ‘Heracles Rationalized and Allegorized’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 395-408.

4 For a general overview of the many versions of the labours of Heracles narrative, I have used Apollodorus’s rendition as the baseline and extended upon it with details from the Oxford Handbook of Heracles, which provides extensive summaries of many sources relating to the myths: Apollodorus, The Library. E, Capps, T. E. Page, W. H. D. Rouse eds. (London-New York 1921) 183-241; Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 4-290.

5 Corinne Pache, ‘Birth and Childhood’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 312, there 7-11.

6 In some versions of the story Heracles only kills his children, and Heracles ends up abandoning his wife later. Either case, Heracles must pay the highest price to attain greatness: Katherine Lu Hsu, ‘The Madness and the Labors’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 13-25, there 15.

7 Sumio Yoshitake, ‘Disgrace, Grief and Other Ills: Herakles’ Rejection of Suicide’, The Journal of Hellenic Studies 114 (1994) 135-153, there 138.

8 Susan E. Gibbons, The Labours of Heracles: A Literary and Artistic Examination (Thesis Doctor of Philosophy, London University, London 1975) 211.

9 Donald A. Russell and David Konstan ed., Heraclitus: Homeric Problems. Writings from the Greco-Roman World (Atlanta 2005) 59.

10 There is speculation that it might have been Admete herself (she then travelled with Heracles) who inflamed a war between the Greek adventurers and the Amazons, not Hera: Adrienne Mayor, ‘Labor IX:The Girdle of the Amazon Hippolyte’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (OxfordNew York 2021) 124-134, there 132.

11 Immanuel Kant, Kant Selections, eds. L.W. Beck, P. Edwards (New York-London 1988) 413-425, there 417-419.

12 Yoshitake, ‘Disgrace, Grief and Other Ills‘, 146-149.

13 Pache, ‘Birth and Childhood’, 6; Hsu, ‘The Madness and the Labors’, 15; Susan Deacy, ‘Heracles Between Hera and Athena’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 387-394.

14 Pauline Hanesworth, ‘Labor XII: Cerberus’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 165-180, there 169-178.

15 Christina Salowey, ‘The Gigantomachy’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 235-250, there 248; Anderson, ‘Heracles as a Quest Hero’, 382; Debbie Felton, ‘Brigands and Cruel Kings’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 165180, there 183-197, there 196.

16 Emma Aston, ‘Labor VI: The Stymphalian Birds’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 95-106, there 103; Emma Griffiths, ‘Auge and Telephus’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (OxfordNew York 2021) 224-234, there 231.

17 Gina Salapata, ‘Labor XI:The Apples of the Hesperides’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (OxfordNew York 2021) 149-164, there 151.

18 Daniel Ogden, ‘Labor VIII: The Mares of Diomede’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (OxfordNew York 2021) 113-123, there 117.

19 Michael Lloyd, ‘Tragedy’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 301-315, there 303; John Wilkins, ‘Comedy’ in: Daniel Ogden ed., The Oxford Handbook of Heracles (Oxford-New York 2021) 316-331, there 316-317.

(I) Museo nazionale romano di palazzo Altemps, Ludovisi Collection via wikimedia.

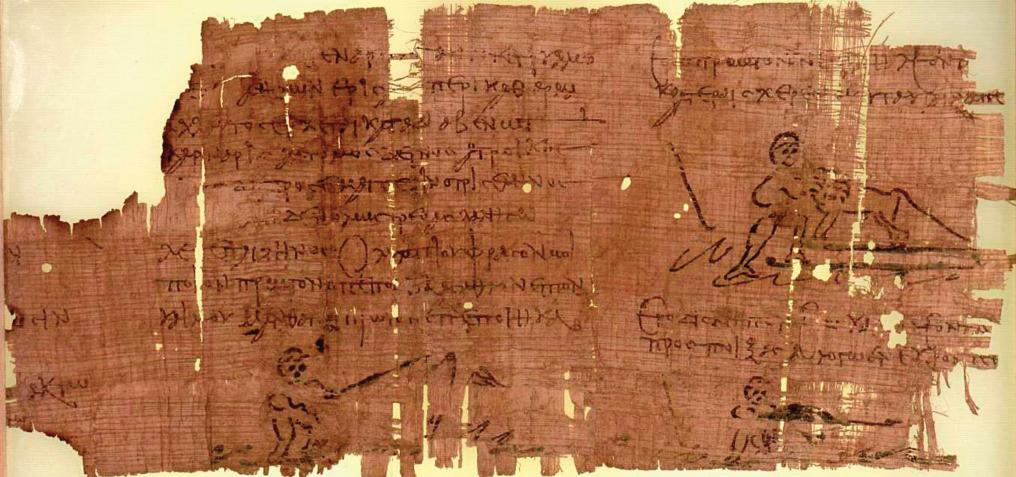

(II) The Heracles Papyrus (Oxford, Sackler Library, Oxyrhynchus Pap. 2331) via wikimedia.

(III) Terracotta neck-amphora of Nicosthenic shape (jar) Attributed to the Class of Cabinet des Médailles 218 ca. 510 B.C. On view at The Met.

(I) Woningbouwcomplex ‘Het Schip’ in de Spaarndammerbuurt (Amsterdam) van Michel de Klerk, gebouwd tussen 1917 en 1921.

In de Amsterdamse Spaarndammerbuurt staat een uniek pand: helemaal oranje en met een grote toren. Het gebouw, dat in de volksmond Het Schip wordt genoemd, kreeg al vanaf de oplevering in 1921 veel aandacht in de wereld van de architectuur. Men was onder de indruk van de eigenzinnigheid en creativiteit waarmee architect Michel de Klerk het pand had ontworpen. Na een bezoek te hebben gebracht aan Het Schip noemde een vooraanstaande Scandinavische architect De Klerk ‘de Rembrandt onder de architecten’.1 Net zo bijzonder als de vormgeving waren echter ook de bewoners van het gebouw: Het Schip was ontworpen voor de huisvesting van arbeidersgezinnen. Het was nog nooit eerder voorgekomen dat arbeiders in zo’n mooi gebouw konden wonen. Met recht werd Het Schip al snel een arbeiderspaleis genoemd.

Arbeiders woonden in de negentiende eeuw vaak in slechte omstandigheden. In Nederland kwam dit omdat de bevolking in de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw sterk toenam. Waar de Nederlandse bevolking rond 1850 nog uit een kleine drie miljoen inwoners bestond, was dit in 1914 verdubbeld tot bijna zes miljoen. De bevolkingsgroei trof vooral de grote steden in het westen van Nederland, waaronder Amsterdam, Utrecht en

spreidden. Aan het einde van de negentiende eeuw waren de omstandigheden in veel Nederlandse steden zo verslechterd dat de nationale overheid besloot in te grijpen.2

In 1901 werd de Woningwet met een overweldigende meerderheid in de Tweede Kamer aangenomen. De nieuwe wet werd zo breed gesteund, omdat de parlementsleden inzagen dat

gunningen. De Woningwet maakte het mogelijk voor verenigingen om financiële steun te krijgen van de overheid voor het bouwen van nieuwe huizen. Dit was het begin van de woningbouwcorporaties, die goedkope leningen kregen van de overheid op voorwaarde dat ze zich volledig toelegden op de woningbouw. De samenleving was aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw sterk verzuild, waardoor elke groep (katholieken, protestanten, socialisten, etc.) een eigen corporatie had. Alle woningbouwcorporaties hadden met elkaar gemeen dat ze woningen bouwden met aandacht voor de gezondheid en hygiëne van de bewoners. De socialistische corporaties gingen echter nog een stap verder; zij hadden als doel om de arbeidersklasse door middel van haar woningen te verheffen, om dus verder te gaan dan kwalitatief goede woningen.4

De socialistische woningbouwcorporaties wilden wooncomplexen bouwen die, naast dat ze uitgerust waren met geschikte voorzieningen, ook van schoonheid getuigden. Deze wens sloot naadloos aan bij de nieuwe architectuurstroming van de Amsterdamse School. De Amsterdamse School begon toen er in de jaren 10 en 20 van de twintigste eeuw in Amsterdam, en andere delen van Nederland, veel werd gebouwd in een expressieve baksteenarchitectuur. De stroming ontstond als een directe reactie op het werk van architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1856-1934), wiens ontwerpen worden gekenmerkt door rationalisme en soberheid, wat goed te zien is in zijn Beursgebouw (Amsterdam, 1896-1905). Zowel Berlage als de architecten van de Amsterdamse School passen in de ontwikkelingen die in de internationale wereld van de architectuur plaatsvonden aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw. Architecten wilden in deze periode vernieuwing teweegbrengen in hun vakgebied, dus waar architecten in de negentiende eeuw regelmatig hadden teruggegrepen op de bouwkunst uit het verleden door middel van de neostijlen (neorenaissance, neogotiek en neoclassicisme), wilde men nu op zoek naar nieuwe inspiratiebronnen. Deze drang naar vernieuwing kwam in de praktijk echter heel anders tot uiting in enerzijds het werk van Berlage en anderzijds dat van de Amsterdamse School. Onder Berlage betekende de vernieuwing vooral sobere en rationele ontwerpen, maar volgens de architecten van de Amsterdamse School moest juist expressieve dynamiek de moderne architectuur kenmerken.5

De Amsterdamse School bestond uit gedreven jonge architecten die volstrekt irrationele vormen begonnen te creëren, vaak met typisch Nederlandse materialen als baksteen en dakpannen. Zij legden de nadruk nu meer op spektakel, schoonheid en romantiek. De benadering van de Amsterdamse Schoolarchitecten was artistiek en idealistisch. Vaak hadden de architecten dan ook geen formele ingenieursopleiding gevolgd. Zij voelden meer voor de bouwkunst, in tegenstelling tot de bouwkunde van Berlage. De Amsterdamse Schoolarchitecten kregen opdrachten voor het ontwerpen van allerlei verschillende soorten gebouwen. Zo ontwierpen de architecten villa’s voor particuliere opdrachtgevers in allerlei plaatsen in Nederland, maar het waren met name grotere bouwblokken zoals woningbouwcomplexen en kantoorgebouwen (een bekend voorbeeld is het Scheepvaarthuis in Amsterdam) die zich goed leenden voor de bouwstijl. De architecten ontwierpen de gebouwen namelijk zo dat de totaalcompositie van de gevels een eenheid vormde. Dit betekende echter niet dat de gebouwen saai en eentonig werden. In de ontwerpen was juist ook veel ruimte voor allerlei creatieve uitspattingen (waar bakstenen ideaal voor waren), zoals experimenten met metselverbanden, uitsteeksels, sierrandjes, rondingen en ramen in bijzondere vormen. Deze kunstzinnig vormgegeven details in de gevels gingen niet ten koste van de eenheid van de gebouwen, maar droegen bij aan de compositie van het geheel; van de kleur van de bakstenen en de raamvormen tot de sculpturen in de gevel en de huisnummers.6

In Amsterdam, waar de huisvesting van arbeiders rond 1900 ook een groot probleem werd, gingen socialistische woningcorporaties samenwerken met Amsterdamse Schoolarchitecten bij het bouwen van nieuwe wooncomplexen. Voor de Spaarndammerbuurt in Amsterdam-West werd door de gemeenteraad

“De Klerk ontwierp in een vernieuwende stijl met veel stijlelementen die kenmerkend zouden worden voor de Amsterdamse School.”

een uitbreidingsplan gemaakt en woningbouwverenigingen kregen de ruimte om woonblokken te bouwen. Architect Michel de Klerk (1884-1923), die zijn carrière al jong was begonnen als assistent bij het architectenbureau van Eduard Cuypers, ontwierp twee gebouwen in deze nieuwe Amsterdamse buurt. De Klerk ontwierp in een vernieuwende stijl, met veel stijlelementen die kenmerkend zouden worden voor de Amsterdamse School: het gebruik van bakstenen met wisselende metselverbanden, dakpannen die voor decoratieve doeleinden werden gebruikt, rondingen in de gevel en ramen in verrassende vormen. De wooncomplexen vielen in de smaak bij het publiek en toen er een derde terrein vrijkwam werd besloten dat De Klerk ook hiervoor het ontwerp mocht maken. Het bouwproject begon in 1917 en stond onder leiding van de socialistische woningbouwvereniging Eigen Haard (opgericht in 1909). Het aangewezen terrein had een driehoekige vorm, wat ervoor zorgde dat deze opdracht ingewikkelder was voor De Klerk dan de eerdere twee. Bij de rechthoekige gebouwen kon De Klerk zich veel meer laten leiden door de gevelwanden, maar bij dit derde project moest de ruimte nog veel duidelijker vormgegeven worden. Voor veel architecten zou dit een moeilijke klus geweest zijn, maar De Klerk ging meesterlijk om met de uitdaging.7

Eigen Haard en De Klerk wilden met het project duidelijk maken dat arbeiders recht hadden op goede én mooie woningen. Volgens hen was ‘niets (…) mooi genoeg voor de arbeider die al zo lang zonder schoonheid heeft moeten leven’. De Klerk maakte van het gebouw, dat dankzij zijn driehoekige vorm in de volksmond ‘Het Schip’ werd genoemd, dan ook een waar arbeiderspaleis. Het wooncomplex telt in totaal 102 woningen. Voor het exterieur gebruikte De Klerk ‘Roode’, oranjekleurige bakstenen die uit Groningen kwamen. De bakstenen werden op verschillende manieren gemetseld; horizontaal werd afgewisseld met verticaal en soms weer

onderbroken door een laag dakpannen. Daarnaast werden in de gevel ook golfbewegingen of rondingen gemetseld die het gebouw dynamisch maakten.

Aan de kant van de Hembrugstraat ontwierp De Klerk een toren op het gebouw, die van buiten helemaal werd bedekt met de karakteristieke oranje dakpannen. De ‘piek’, zoals de toren door de bewoners werd genoemd, gaf het gebouw een sterke herkenbaarheid. Door een toren, iets wat normaliter eigenlijk alleen bij kerken te zien was, te bouwen op een wooncomplex voor arbeiders, liet De Klerk merken dat er een nieuwe tijd was aangebroken. De Klerk zorgde ervoor dat de arbeiders met trots naar buiten konden treden. Wat Het Schip nog meer zo geslaagd maakt is dat het geheel een eenheid vormt, terwijl er tegelijkertijd ook veel aandacht is besteed aan de details. Overal in het exterieur zijn dezelfde materialen gebruikt, waardoor elke zijde hetzelfde gevoel uitstraalt. Binnen de uniciteit is er echter ook veel ruimte voor details geweest, bijvoorbeeld in de vorm van ornamenten en sculpturen in de gevel. Dit maakt dat het gebouw ondanks de heldere compositie ook een grote verscheidenheid biedt, waardoor het niet snel gaat vervelen.8

Dankzij het eigenzinnige ontwerp kwamen er veel reacties op Het Schip toen het in 1921 werd opgeleverd. Nederlandse architecten raakten geïnspireerd door De Klerk en gingen ook steeds meer in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School bouwen. Architecten uit het buitenland waren positief over het gebouw en er werd veel aandacht besteed aan Het Schip in buitenlandse publicaties. In de gemeenteraad van Amsterdam werden echter

(III) Het Schip op de hoek van het Spaarndammerplantsoen en de Oostzaanstraat.

kritische vragen gesteld over Het Schip, in het bijzonder over de hoge kosten en de weelderige uitstraling. Bij sommige raadsleden viel het niet in de smaak dat de architect gemeenschapsgeld verspilde aan het bouwen van zinloze ornamenten op arbeiderswoningen in tijde van grote woningnood en materiaalschaarste. Men vond de vormgeving van het gebouw te luxueus voor arbeiderswoningen. Dankzij de inspanningen van de Amsterdamse wethouder Floor Wibaut (1859-1936) lukte het toch om de financiering voor Het Schip rond te krijgen. Wibaut wees de gemeenteraad erop dat De Klerk een groot architect-kunstenaar was en dat hij het verdiende de gelegenheid te krijgen om al zijn kwaliteiten te kunnen ontplooien in het ontwerp voor de arbeiderswoningen.9 Daarnaast kwam er kritiek op het gebouw van architecten uit de stromingen van het functionalisme en het Nieuwe Bouwen (beide stromingen kwamen vanaf omstreeks 1920 op), waarin de functionaliteit van gebouwen voorop stond, zonder ruimte voor versieringen. Deze functionalisten in de architectuur beklaagden zich dat de meeste decoraties en de toren van Het Schip geen enkele functie hadden voor het gebouw.10

keuken, vaste kasten en een ledikant. Het complex telde achttien verschillende typen woningen, waarvan de meeste twee slaapkamers en een woonkamer hadden. Bovendien waren de keukens in de woningen behoorlijk groot voor de tijd, met de ruimte om er met een klein gezin te eten zodat de woonkamer netjes bleef. De kwaliteit van de woningen maakte dat arbeidersgezinnen in Het Schip een heel stuk comfortabeler woonden dan voorheen in de krotwoningen.11

De belangrijkste partij, de werkelijke bewoners van het gebouw, hielden echter van Het Schip. De Klerk had het hele gebouw met zorg ontworpen, van de details in de gevel tot de typografie van de huisnummers en de indeling van de woningen. De woningen waren van binnen ingericht met een schouw, een

Het Schip nu

Bij de totstandkoming van Het Schip speelde echter de wens om niet alleen kwalitatief goede woningen te creëren maar een waar arbeiderspaleis te bouwen een centrale rol. Ook dit bleef niet onopgemerkt door de bewoners, die trots waren op hun complex. De bewonerscommissie zette zich in om het exterieur van het complex zo veel mogelijk ongedeerd te laten en vroeg de kinderen uit de buurt om niet op de bakstenen te krijten. Daarnaast werden er geen posters zoals verkiezingsplakkaten achter de ramen geplakt, zodat de woningen van buiten ook gezien konden worden.12

Het bouwwerk van De Klerk is tot op de dag van vandaag in bezit van woningbouwvereniging Eigen Haard. Tegenwoordig kent het gebouw 81 woningen, die tussen 2015 en 2018 zijn gerenoveerd. Bijna honderd jaar na de oplevering van het gebouw waren de woningen flink verouderd. Er was sprake van geluidsoverlast, onvoldoende brandwerendheid en allerlei technische mankementen. Ook het exterieur van Het Schip is onder handen genomen tijdens de renovatie. Hierbij werden materialen gebruikt die zo veel mogelijk aansloten bij de originele bouwmaterialen waarmee De Klerk het gebouw had ontworpen. Hiervoor moest Eigen Haard opzoek naar bakstenen die identiek waren aan de originele, wat lastig bleek omdat moderne productiemethoden niet meer dezelfde resultaten geven als vroeger. Ook de zoektocht naar de juiste dakpannen stuitte op problemen. Een bedrijf moest speciaal voor de renovatie mallen maken op basis van de oude dakpannen. Na de renovatie is een deel van de huurwoningen geliberaliseerd, in tegenstelling tot de situatie ten tijde van de oplevering van het gebouw in 1921, toen alle woningen sociale huur waren.15 De geschiedenis van Het Schip als monument van de volkshuisvesting en arbeiderspaleis wordt gelukkig nog wel in leven gehouden. Als rijksmonument wordt het gebouw beschermd, zodat het ook in de toekomst nog in dezelfde staat zal voortbestaan. Bovendien biedt het pand sinds 2001 ook onderdak aan een museum dat is vernoemd naar het gebouw. Museum Het Schip vertelt het verhaal van de Amsterdamse Schoolstroming en laat de visies en idealen van De Klerk en andere Amsterdamse Schoolarchitecten voor het publiek tot leven komen.16

“Niets is mooi genoeg voor de arbeider die al zo lang zonder schoonheid heeft moeten leven.”

het Spaarndammerplantsoen en de Zaanstraat.

Toen Michel de Klerk in 1923 – slechts een paar jaar nadat Het Schip gereed was gekomen – plotseling overleed, maakten de bewoners van het complex hun dank kenbaar voor de architect die hen zulke mooie woningen had gegeven.13 Eén bewoonster, een arbeidersvrouw die met haar gezin in Het Schip woonde, bedankte de architect na zijn overlijden in een ingezonden brief naar het socialistische dagblad Het volk voor alles wat hij voor de arbeiders had gedaan. De vrouw leefde met veel plezier in het complex: ‘Is het niet heerlijk uit de vermoeienissen van den dag te komen in een huis gebouwd uit louter genot en huiselijk geluk? Is het niet of iedere steen je toeroept: Komt allen, gij werkers en rust uit in je huis, dat er voor u is.’14 De arbeiders en bewoners van Het Schip leefden met veel waardering in het gebouw. De Klerk heeft met zijn ontwerp laten zien dat ook arbeiders het verdienen om in een paleis te wonen.

1 T. Heijdra, A. Roegholt & R. Wansing, Arbeiderspaleis Het Schip van Michel de Klerk (Amsterdam 2012) 108.

2 M.Wagenaar, ‘Stedenbouw, volkshuisvesting en architectuur in Nederland, 1850-1950’, Groniek 162 (2004) 59-74, aldaar 5960.

3 Ibidem, 72-74.

4 Ibidem.

5 H. Searing, ‘Amsterdam School’, in: R.S. Sennott, Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol. 1 (Chicago 2004) 87-89; Heijdra et al., Arbeiderspaleis Het Schip, 41-47.

6 Searing, ‘Amsterdam School’, in: Sennott, Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, 87-89; Heijdra et al., Arbeiderspaleis Het Schip, 41-47.

7 Heijdra et al., Arbeiderspaleis Het Schip, 57-60 en 65-71.

8 Ibidem, 57-60, 65-71, 89-93 en 104-106.

9 Ibidem, 107.

10 P. Groenendijk, P. Vollaard & P. Rook, Gids voor moderne architectuur in Amsterdam (Rotterdam 1996) 30.

11 Heijdra et al., Arbeiderspaleis Het Schip, 116.

12 Ibidem, 117.

13 Ibidem.

14 ‘De Klerk’, Het volk: dagblad voor de arbeiderspartij (28 november 1923).

15 B. Pots, ‘Start restauratie Het Schip’, Nul20 76 (2014) 3435.

16 ‘Museum Het Schip’, https://www.hetschip.nl/over-hetmuseum/locaties/het-schip (geraadpleegd op 11 oktober 2021).

(I) Stadsarchief Amsterdam, 1976.

(II) Stadsarchief Amsterdam, ca. 1995.

(III) Stadsarchief Amsterdam, 1980.

(IV) Stadsarchief Amsterdam / Martin Alberts, 2005.

(V) Stadsarchief Amsterdam / Han van Gool, 1991.

Do animals work the same way humans do? If they do, what does this say about our understanding of labour? And if they do not, why not? There are fundamental, intuitive differences between human and non-human animal labour and I want to explore some of these in this article. Understanding historical non-human animal labour is essential for building a more ethical world for both humans and the other animals who shape and share our societies. I will be broaching on some complicated and huge subjects which I myself do not grasp fully. That is why I do not pretend to offer answers in this article, although my personal biases will shine through regardless. Instead, I want to briefly lay out the issues and encourage you to consider and discuss them with those around you.

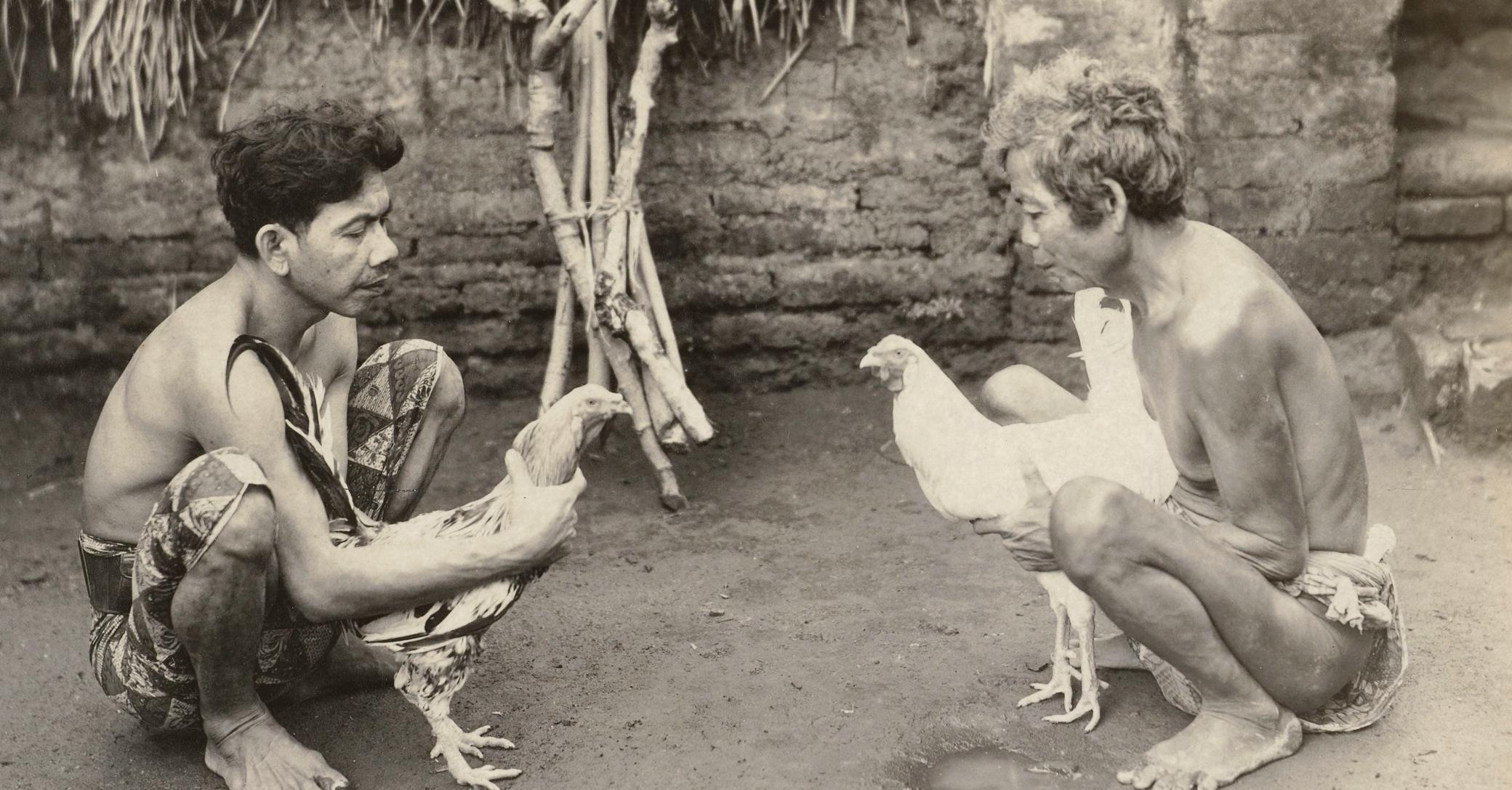

Before we proceed, it is important to mention some examples of non-human animal labour. Non-human animals, historically and in the present, may be found working in agriculture, industry and the services. Agricultural labour is quite easy to conceptualize: horses and oxen pulling on plows are an obvious example. Whether cattle, pigs, chickens, and other animals raised and fed for consumption can be called labourers, is another discussion altogether, one I will leave to the side for this article. Industrial labour is, generally speaking, a thing of the past. For centuries, perhaps millennia, horses and mules were used to spin mills, processing cereals which fed cities. They also played a large role in the early days of the industrial revolution, when horsepower was still cheaper than coal-burning.1 Service labour is the type we encounter most frequently in the Global North in the twenty-first century: dogs working in lawenforcement and healthcare, horses transporting goods and

This definition is followed by an explanation that most labour in world history was (and is) performed without salary compensation, claiming “only a prejudice bred by Western capitalism and its industrial labor markets fixes on strenuous effort expended for money payment outside the home as ‘real work’, relegating other efforts to amusement, crime and mere housekeeping”.3 In this definition rests an awareness that most labour fits outside of our commonplace understanding of work, and that cleaning one’s own kitchen is work to the same degree as an office job is. In English, it is commonplace to ask ‘what do

you do’, and in Dutch ‘what kind of work do you do’. Following the Tillys’ definition, an answer would have to include, next to one’s job title, things like laundry, personal logistics and cooking.

Explicitly absent from their definition are other species; work according to them can only involve ‘human effort’. Karl Marx was of a different mind, claiming that “animals also produce. They build themselves nests, dwelling places, like the bees, beavers, ants, etc. But the animal produces only what is necessary for itself or for its young. It produces in a one-sided way.” While non-human animals are capable of performing labour, it is inherently different from human labour: “what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in his imagination before he erects it in reality.”5 Marx respects that non-human animals may exercise effort to achieve goals such as building a nest and understands this as work, but it is fundamentally different from what humans do.This is because Marx believes labour to be a method of selfactualization for humans.

According to Marx, humans transform their natural environments through labour, and in doing so not only shape their surroundings, but also themselves. Labour allows the selfconscious and rational mind unique to humans to self-actualize in material reality. Since other animals do not possess the sophisticated human mind, they cannot separate themselves from nature in the way humans do, and so their existences are limited to performing labour strictly to serve their physical needs without it impacting their emotional or mental state.They cannot make decisions, acting purely on impulse. As they remain a part of nature in their own minds, they cannot self-actualise through labour in the same way humans can.6

work is fundamentally different from ours. However, recent scholarship has proven this gap between humans and other animals is not quite as large as 19th century thinkers believed it was. Behavioural testing with several species of animals has demonstrated that many species are capable of quite advanced planning and understanding that they could receive (somewhat) abstract rewards in exchange for performing work.7 Conversely, empirical testing has shown that humans are nowhere near as rational as we like to think we are. For example, humans operate on countless irrational biases on a daily basis. Similarly, the notions of free will and human consciousness have also come under fire by recent scientific discoveries.8 While complex planning may be out of the realm of non-human understanding, does this really define what makes human labour special? Most labour in human history has concerned filling relatively direct needs: hunting, trapping or farming to provide food, construction to provide shelter, cleaning to prevent disease. Does the distinction between human and non-human animal labour collapse when taking the majority of human labour into account?

Marx’s writings are, of course, over a century old. Nevertheless, I believe they describe the core of modern understanding of what makes non-human animal labour different quite aptly. Nonhuman animals cannot think or plan the way we do, so their

At this point, we should consider why we might bother understanding the work conducted by non-human animals as labour. Most thinkers concerned with classifying non-human

“Humans are nowhere near as rational as we like to think we are.”

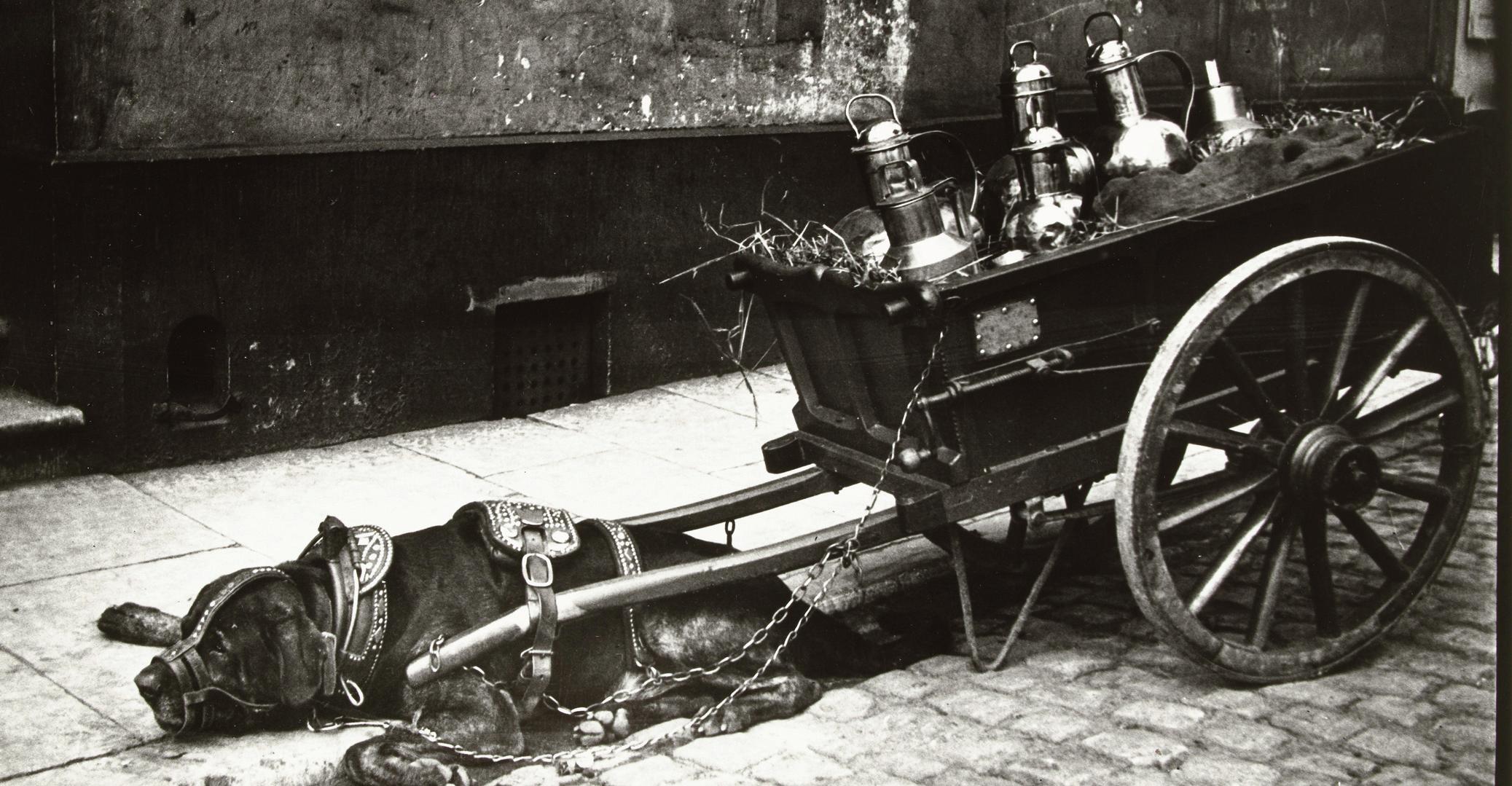

(II) A horse idly awaiting further instructions from his human colleagues.

animal work as labour believe it can be an emancipatory move.9 If people understand that non-human animals, such as horses pulling carts, dogs caring for the blind or trauma victims, or even cattle and pigs bred for the slaughter, work just like they do, they may gain empathy for these exploited – dare I say, enslaved – fellow labourers. Non-human animals are rarely given a choice in what type of work they will perform, or under what conditions they will perform their labour. Resistance, such as the refusal of a carthorse to continue walking, is met with a beating to encourage work, rather than negotiating a 15-minute break. Non-human animals are unable to leave a workplace and join another. In essence, they are not allowed to say ‘no’.

Is a non-human animal that is free to choose what it does for a living happier? Empirical tests can and have demonstrated that non-human animals are more enthusiastic and less stressed when provided with a choice. Apes in captivity, for example, have demonstrated that they are happier when provided the choice to move freely between their inside and outside enclosures, even if they do not take advantage of that choice.10 This offers an intriguing opening to what other choices humans are denying other animals. Empirical testing is just one step of the process. It can make us aware of the issue, but it cannot solve it. Instead, the question reaches deep into our cultural understanding of what makes humans different from other animals. It would also require significant effort on the part of humans to try to find ways to communicate and especially listen to other animals and to understand their wishes.11

The connections to human slavery are obvious, and yet, perhaps justly, out of reach. One of the many atrocities inherent to slavery is that it ‘dehumanizes’ people, treating them like animals. This implies that the manner in which non-human animals are treated is natural and not at all at issue. The question, I think, is whether non-human animals should be able to self-actualize through their labour. From this need to selfactualize derives a need to be free to choose your own work.

Cultural shifts in the attitude towards other animals have happened throughout history. In fact, I wrote about one in an article in CODEX’s own Crime & Justice 12 I believe the present ecological crisis that is climate change will force us to look differently at our own environment and at the other beings that inhabit it with us. What we will discover and decide in the coming decades will radically change the way we look at other animals and their labour. And I, for one, cannot wait to find out what that will be.

Animal labour is a very new field of analysis, both in the humanities and other disciplines. Nevertheless, I can recommend a few texts on animal ethics, animal labour ethics and animal labour history.

(Historical) animal ethics:

Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500-1800 (1983)

Hilda Kean, Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800 (1998)

Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (2009)

Rob Boddice, A History of Attitudes and Behaviours Toward Animals in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Britain: Anthropocentrism and the Emergence of Animals (2009)

Daan Jansen, ‘The Rise of British Rat-Killing. How Animal Cruelty Regulation Created a Blood Sport’ in: CODEX Historiae 42:1 (2021) 40-44

Animal labour ethics:

Jason Hribal, ‘Animals, Agency and Class:Writing the History of Animals from Below’ in: Labour History 44:4 (2007) 435-453

Jason Hribal, ‘Animals are Part of the Working Class Reviewed’ in: Borderlands 9 (2012) 1-37

Kendra Coulter, Animals, Work and the Promise of Interspecies Solidarity (2016)

Jocelyne Porcher, The Ethics of Animal Labour: A Collaborative Utopia (2017)

Charlotte E. Blattner, Kendra Coulter, and Will Kymlicka (eds), Animal Labour. A New Frontier of Interspecies Justice? (2019)

Animal labour history:

Richard Hoffmann, An Environmental History of Medieval Europe (2014)

Frederick Brown, The City is More than Human. An Animal History of Seattle (2016)

Thomas Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts. How animals shaped Georgian London (2019)

Kaori Nagai, ‘Vermin writing’ in: Journal for Maritime Research, 22:1-2 (2020) 59-74

“Climate change will force us to look differently at our environment and other beings.”

1 An excellent work on this development is Thomas Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts. How animals shaped Georgian London (2019).

2 Cited in Karin Hofmeester & Jan Lucassen, The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations: Putting Women’s Labour and Labour Relations in sub-Saharan Africa in a Global Context (2021, upcoming article).

3 Ibid.

4 Marx quoted in Omar Bachour, ‘Alienation and Animal Labour’ in: Charlotte E. Blattner, Kendra Coulter, and Will Kymlicka (eds), Animal Labour. A New Frontier of Interspecies Justice? (2019) 117-138; 121.

5 Ibidem, 122.

6 Ibidem, 121-123.

7 Charlotte Blattner, ‘Animal Labour. Towards a Prohibition of Forced Labour and a Right to Freely Choose One’s Work’ in: Charlotte E. Blattner, Kendra Coulter, and Will Kymlicka (eds), Animal Labour. A New Frontier of Interspecies Justice? (2019) 91-115; 93-96.

8 Ibidem, 97.

9 Charlotte Blattner, Kendra Coulter & Will Kymlicka, ‘Introduction’ in: Charlotte E. Blattner, Kendra Coulter, and Will Kymlicka (eds), Animal Labour. A New Frontier of Interspecies Justice? (2019) 1-26; 4.

10 Blattner, Animal Labour, 96.

11 Ibidem, 109.

12 Daan Jansen, ‘The Rise of British Rat-Killing. How Animal Cruelty Regulation Created a Blood Sport’ in: CODEX Historiae 42:1 (2021) 40-44.

(I) George Hendrik Breitner, ca. 1890-1910, Rijksmuseum.

(II) Théodore Géricault, 1823, Rijksmuseum.

(III) Anonymous, ca. 1930-1940, Rijksmuseum.

(III) Propaganda-dogs, advertising Walrave “Wally” Bossevain’s (successful) electoral campain for the Amsterdam city council.

Hi, dear friends of CODEX and Merlijn! Everyone at the VU has been working hard to return everything back to normal. The new Merlijn board has also laboured busily since the dreamed return to campus to provide its members with fun activities. So far we have been building our networks within the faculty, because much contact with other parts of the faculty had faded during the lockdowns. We were also locked out of our own social room for a long time, but we have now received our passes (hurray!) and it is starting to feel a bit like home. By now we’ve held our first Merlijn ‘borrel’ there, which was a great success! We loved seeing students from all years talking and laughing together, while enjoying their beers and cocktails.

Right now we’re cooperating with CODEX to work out something special for the release of this ‘Labour’ edition of CODEX Historiae. We’ve also helped with the Halloween party of the Faculty, and we are planning something fun for our first year members soon after! We will keep working hard to make this a fun year for you all. See you at the next events, or in the social room (HG-12A-43)!

Hi! We’re this year’s Faculty Student Council (FSR). We look forward to working together with all Humanities students to make this transition out of online education as easy as possible.

The FSR represents the interests of the students in faculty decision-making, as well as within the university at large. What does that mean for you? Well, is there an exam at a stupid time that doesn’t work for anyone? Is a teacher giving you assignments to do during the education-free week? Do you need help or advice as an international student in the Netherlands for the first time? Please tell us! It is our job to help you out to the best of our ability.

To achieve this, we’ve written up a policy plan with our broad goals for the upcoming year. A top priority for us is helping wi transition from digital to hybrid and finally to fully on-campus education. We aim to make sure that the Faculty and Exam Board understand the need for a gradual transition, to ensure students are receiving the highest quality of education possible.

Our other goals for this year are a bit more general and include continuing to help international students during these ‘unprecedented times’; organising more social events for all Humanities students to mingle and meet new people; making the faculty more inclusive for international students; opening up the Humanities social room on the 12th floor; increasing our social media presence; and increasing awareness around student wellbeing and mental health.

Most importantly, we want to invite you to share your issues and complaints with us! At the end of the day, we’re students just like you. This means, among other things, that you don’t need to feel scared to approach us. We truly want to make a difference in the faculty, but we’ll only be in the FSR for a year, so the sooner we know what we need to work on, the better!

You can reach us at our email (fsr.fgw@vu.nl), our Instagram (@fsrgeestes), or our Facebook (@fsr.geesteswetenschappen). Or, if you happen to recognise one of us from the picture, feel free to just talk to us! We don’t bite!

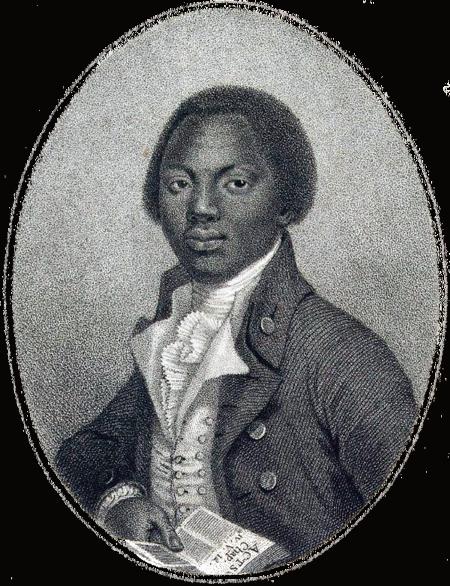

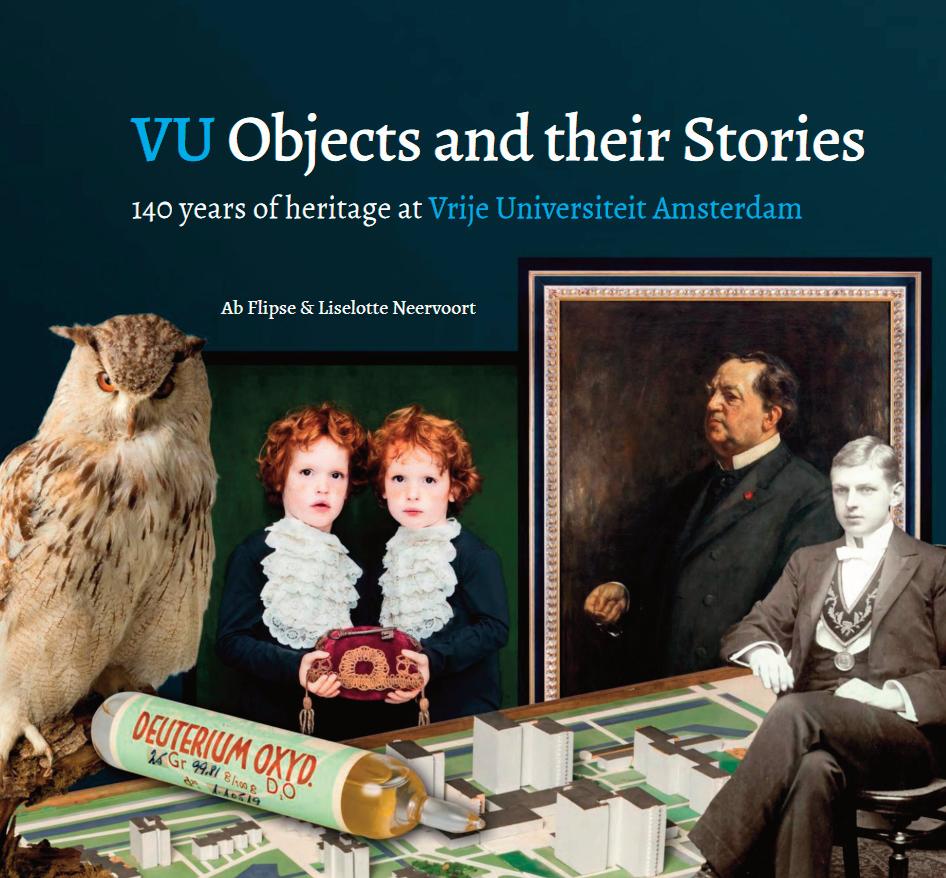

As the other articles in this issue have no doubt already proven, labour is everywhere. As we understand the word in modern Dutch society, labour, or work, refers especially to things we do in exchange for money. Remuneration is key to our understanding of work in the everyday sense. However, many other systems of organizing labour exist and have existed in the past. Not all work resulted in remuneration. Enslaved people were not paid for their labour on plantations in the Americas, and neither were (or are) women for child-rearing or maintaining the household. These kinds of work fall under different types of labour relations, which dictate “for or with whom one works and under what rules.”1 Examining these labour relations helps expose the power dynamics at play in a society and how these have developed throughout history. The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations seeks to examine the last 500 years of labour relations globally.

The Collaboratory was set up in 2007 at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam to bring nuance to an otherwise highly simplified history of labour relations.This simplified history assumed a global, gradual development from labour for the household or the state in a feudal-like dynamic, towards commodified labour (i.e. labour whose products will be traded in a market).This development mirrors the spread of capitalism as the dominant economic system worldwide. However, this history lacks clear definitions or accuracy, and so remains somewhat nebulous. The Collaboratory intended to chart shifting labour relations on a country or region-basis in five distinct years: 1500, 1650, 1800, 1900 and 2000. By looking at these ‘cross sections’ of the past 500 years, we can observe general trends on a global scale. The project is not worked on inside the VU, although VU professor Ulbe Bosma and several VU-students, including myself, are involved in it.

An international team of specialists was assembled to do research on their specific areas of expertise. They set out to collect and compile data on their regions of expertise, armed with an extensive, cooperatively designed taxonomy of labour relations covering all possible labour relations of the past 500 years. These data would then be collected into datasets,

describing the entire population of their region in their cross section(s) as accurately as possible. The participants in the Collaboratory focused explicitly on charting the entire (estimated) population of a country, rather than just those considered working. This was done to force the participants into thinking about what kind of work might be invisible in the sources, especially female and child labour.

This is all a bit abstract, so let’s take a look at an example from my own work on the Collaboratory. The lion’s share of my role as student-assistant in the project has been in working together with Ulbe Bosma to collect, interpret and compile data regarding Maritime South East Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. This is a huge task, as each country is massive and had completely different colonial histories, which affected the sources we could consult significantly. For example, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had little interest in governing the people of Indonesia, preferring simply to extract value from them via local princes. Because of this, the first estimates of the Javanese (working) population that even come close to approaching reliability comes from Stamford Raffles, a British statesman who governed the Dutch East Indies during the Napoleonic Wars. His writings on the topic are still heavily distorted and require a critical eye before use.

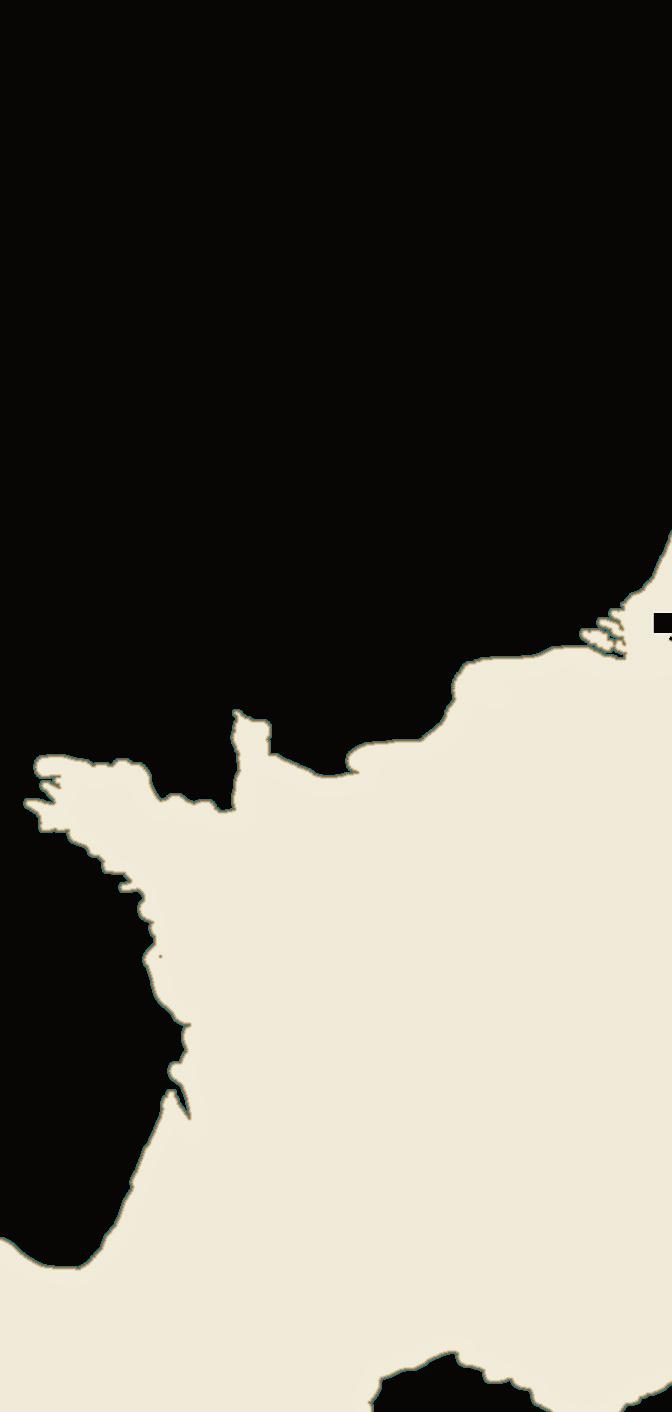

Map of countries covered in Collaboraty research to date. Black countries have published datasets; darker grey countries (India and several African countries) have research conducted but lack published data at present; lighter grey countries (Malaysia, Philippines, France and Great Britain) are currently works in progress.

The work the Collaboratory has done would have been impossible without a shared set of definitions, laid out in the Taxonomy of Labour Relations.The taxonomy is best visualised in the chart you can see by scanning this QR-code (or googling “global collaboratory taxonomy”). It involves dividing the total population among several different types of exchange, which are the most basic type of labour relation: those without work, namely the young, the old, the infirm, the work-seeking and the wealthy; those who work primarily for the household, in a reciprocal fashion, with the expectation that the work done will be rewarded not with money but with goods and services in kind; those who are made to work for the polity, providing tributary labour for the state without receiving monetary reward; and those who work for the market, exchanging their labourtime/productivity for money.

These types of exchange are all subdivided further into specific labour relations, by which researchers can distinguish the wildly varying types of relations that fall under these broad categories. For example, self-employed artisans selling their work on the markets of Marseille and enslaved people being worked to death on the sugar plantations of Saint-Domingue in the 18th century are both classified as commodified labour, but the expected hours worked, the remuneration, and the power dynamics are wildly different.When classifying a labour relation, researchers are invited to look at the treemap ‘backwards’, from right to left, to ensure that they think from the individual’s perspective. This allows the classification of an individual as working in multiple separate labour relations: a factory labourer might supplement their income with small-scale artisanship or peddling on the side, so that they are considered to work under both labour relation “14” and “12a” simultaneously. Each labour relation has a specific definition, for which I invite you to consult the collaboratory website (see ‘Further reading’). As stated earlier in the text, the taxonomy was designed in collaboration with many researchers across the world. The taxonomy has been updated a number of times to better suit the various circumstances researchers have found worldwide.

Other sources are similarly skewed or distorted, reflecting the European colonial male understanding of the world in poorlyexplained racial classifications and a general absence of women, children and nomadic or unincorporated indigenous people. It becomes our task to use these flawed sources to try to get the data we need from them, in a form that makes sense, and to explain the researcher’s entire thought process and justification of their categorization in a methodological paper published alongside the dataset. For example, the number of water buffalo counted in Indonesia in the early 19th century becomes a window into the wealth distribution among farmers. Farmers wealthy enough to own water buffalo could likely sustain themselves with their own land, while those who did not own any would have had to supplement their incomes by selling their labour to other farmers, while also managing their own farms. Similar data exists for the other islands in Indonesia, which implies homogeneity in agriculture throughout the Dutch East Indies. However, cultures and agricultural practices on the other islands varied so wildly and were so different from those on Java that we could not use those data to make a similar distinction.

Once a reasonable amount of data has been collected and classified, an overview of the country or region’s population is put in a large, standardized Excel file. Here, groups can be specified by age, gender, location, urbanization, branch of industry and so on, allowing – in theory – for highly detailed research towards various functions of labour relations.The level of detail a researcher can put into their data is, of course, highly dependent on the sources they have available. The datasets on

Russia are incredibly detailed, so that you can find the single retired priest living in a village. Other datasets, such as those on China, are based almost entirely on estimates (or ‘guesstimates’), thus feature large undifferentiated groups, sometimes counting millions of people.

Definitions and datasets are all well and good, but they mean nothing if not used for historical research. Over the years, the Collaboratory and their approach have proven their value. A wide range of historical questions has been tackled while using the Collaboratory’s taxonomy. One area of research the Collaboratory has shed light on is the economy of Angola, which in 1800 was the largest supplier of enslaved people to the Atlantic market. After the slave trade was abolished, Angola’s economy had to shift its focus to exporting non-human commodities.This involved a large amount of both enslaved and relatively free labour. Throughout the 19th century, a transition took place, from labour that was performed largely to support the household directly (reciprocal), to commodified (wage) labour. In the latter half of the 20th century, during a bloody conflict for independence from Portugal, followed by decades of brutal civil war, this transition was reversed, as international trade with Angola declined significantly. People began producing for their households and families again in the face of war and economic uncertainty. Crucially, if one looks only at the labour divisions between the broad branches of work (agriculture, industry, services), Angola appears to follow a ‘traditional’ trajectory between 1800 and 2000, with a smaller percentage of the population in agriculture and a rising one in services.This

return to the prevalence of reciprocal labour, crucial to understanding the Angolan economy, is invisible without a labour relations approach.2

Not only the approach with its associated taxonomy has merits, but the ability to compare between countries, regions and continents is also highly valuable. The data is far from able to present a global overview as of yet, especially for the 1500 and 1650 cross sections, but the outlines of trends can still be parsed out. Data on Russia, Brazil, China and Venice support the idea that labour relations gradually shifted towards marketoriented work rather than reciprocal work, but indicate that this shift happened far sooner than initially expected, with large sections of the populations of all these countries performing commodified labour as soon as 1650. Men experienced this shift sooner than women, as women were often excluded from the commodified labour market and worked in reciprocal relations to the rest of their households. Nevertheless, regional differences remain important, such as women’s roles as traders and shopkeepers on Java. Similarly, commodification of labour was not simply a question of one or the other; many people, men and women both, historically commodified their labour for part of their time, and worked for the household for another portion of their time. This actually remains true for large portions of the world population, including myself, to the present day.

The Collaboratory continues to extend its offering of datasets. The project recently took on two very talented student interns, one of whom studies at the VU, to conduct research on the historical labour relations of France and the United Kingdom, which were sorely lacking from the Collaboratory until now. As

you can see on the map on page 22, far from all countries have been covered and helping to extend this data is extremely valuable. Research need not necessarily result in a database; well-grounded research into the historical labour relations of a specific country based on, say, census data and the work of historical demographers and labour historians is similarly important.

We invite students and researchers to use the data we provide for their own research.This is also helpful for us, because more minds thinking about the same issues can always lead to new insights. The labour relations taxonomy described in the info box on page 23 can be an incredibly useful tool to analyse economic developments. Our datasets are also free to use for your research, with the caveat that you ought to read the included methodological papers to understand the thought process behind the datasets. The datasets were created to be used by researchers and we are curious to see what insights they might offer you.

1 Karin Hofmeester, Jan Lucassen, Leo Lucassen, Rombert Stapel, Richard Zijdeman, ‘The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500-2000: Background, Set-Up, Taxonomy and Applications’, IISH Data Collection (2016), 6.

2 Jelmer Vos, ‘Work in Times of Slavery, Colonialism, and Civil War: Labour Relations in Angola from 1800 to 2000’ in: History in Africa 41 (2015) 363-385.

Further reading

If you are interested in learning more, feel welcome to take a look at the datasets and papers on https://datasets.iisg.amsterdam/ dataverse/labourrelations (googling “dataverse labour relations” yields the page as well).

For more information on the Collaboratory, read: Karin Hofmeester, Jan Lucassen, Leo Lucassen, Rombert Stapel, Richard Zijdeman, ‘The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500-2000: Background, Set-Up, Taxonomy and Applications’, IISH Data Collection (2016) on the dataverse website.

For some publications resulting from the Collaboratory, see:

Karin Hofmeester, Jan Lucassen, Filip Ribeiro da Silva, ‘No Global Labour History without Africa: Reciprocal Comparison and Beyond’ in: History in Africa 41 (2014) 249-276

Karin Hofmeester & Jan Lucassen, The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations: Putting Women’s Labour and Labour Relations in sub-Saharan Africa in a Global Context (2021, upcoming article)

Mary Louise Nagata, ‘The Evolution of Marriage, Inheritance and Labour Relations in the Family Firm in Kyoto’ in: The History of the Family 22:1 (2017) 14-33

Dmitry Khitrov, ‘Tributary Labour in the Russian Empire in the Eighteenth Century: Factors in Development’ in: International Review of Social History 61:S24 (2016)

Leo Lucassen, ‘Working Together: New Directions in Global Labour History’ in: Journal of Global History 11:1 (2016) 66-87

Karin Hofmeester & Pim de Zwart (eds.), Colonialism, Institutional Change, and Shifts in Global Labour Relations (2018)

kennen Jaap-Jan Flinterman, onze geliefde docent oude geschiedenis aan de VU, als een geweldige spreker die de oude wereld voor je ogen tot leven wekt. Zijn passie voor zijn vakgebied, zijn ervaren retoriek en de droge humor die hij verstopt in zijn colleges (voor wie oplettend genoeg is) zorgen voor een onvergetelijke academische ervaring. Helaas gaat Flinterman met pensioen en zullen we afscheid van hem moeten nemen. Op vrijdag 1 oktober was er al een afscheidssymposium voor hem georganiseerd, maar gelukkig vertelt Flinterman ook ons nog een laatste keer over zijn onderzoek, zijn tijd als docent en zijn passie voor zijn vak.

Hoe Flinterman in de oude geschiedenis terecht is gekomen, heeft zowel te maken met zijn passie voor het Grieks als met praktische overwegingen. ‘Het is een voorliefde en fascinatie voor de Griekse wereld, maar het is ook altijd wel de intellectuele uitdaging om brood te bakken van verschijnselen die op eerste gezicht ontoegankelijk en raadselachtig overkomen – het exotische.’ Hoewel hij tijdens het gymnasium oude stijl zijn interesse voor oude talen heeft ontdekt en daaraan tijdens zijn studie geschiedenis een vervolg heeft gegeven, ‘was het ook gedeeltelijk toeval. Je kon in de vroege jaren ’80 de sloten dempen met afgestudeerde historici.’ Gelukkig was er in de academische sfeer voor hem altijd tijdelijk werk te vinden op het gebied van oude geschiedenis.

Het onderzoeksgebied van Flinterman was de cultuur- en mentaliteitsgeschiedenis van de sociale elite in de Griekse provincies van het Romeinse Rijk tijdens de keizertijd. Dit onderzoek kwam voort uit zijn doctoraalscriptie, die destijds aansloot bij een nieuw onderzoeksgebied binnen de vakgroep oude geschiedenis. Deze vakgroep hield zich toen bezig met Grieks politiek denken na de klassieke tijd (grofweg de vijfde en vierde eeuw voor Christus). Flinterman werd toen ‘gezet’ op het onderzoek naar de Vita Apollonii: een biografie van Apollonius van Tyana (een eerste-eeuwse wijze wonderdoener uit KleinAzië), van de hand van de Atheense sofist Philostratus (ca. 170-247 na Chr.). Het is een sterk gefictionaliseerde biografie waarin de hoofdpersoon als een politiek actieve filosoof wordt gepresenteerd. Flinterman heeft zeven jaar over zijn promotie gedaan en heeft die tijd goed gebruikt om zich breed in te lezen in de retorische cultuur die ontsnapte uit het klaslokaal, of wel de tweede sofistiek. Deze vorm van welsprekendheid ontstond in de vroege keizertijd van het Romeinse Rijk uit de afstudeeropdrachten voor jongemannen die retorisch onderwijs volgden: een gerechts- of politieke redevoering in een fictieve setting. Van een onderwijsvorm werd het een vorm van entertainment voor de elite.

‘Ik denk dat [de fascinatie voor dit onderwerp] vooral kwam omdat ik het niet begreep. Je had [tijdens de studie] aan een aantal onderwerpen geroken, maar er was ook ontzettend veel waar je weinig of niets van begreep bij de eerste kennismaking. Je kunt zo’n literaire of retorische cultuur volgens een collega interpreteren als een “badge of elite identity”, maar dat had ik niet onmiddellijk in de gaten. Ik begreep ook niet wat alle anekdotes inhielden omdat ik het retorisch verschijnsel op zich niet snapte. Ik kende retorica, zoals de historicus dat leert, als de kunst van juridische of politieke overtuiging, maar hier was het opeens een spelletje geworden. Het duurde even voordat ik daar grip op kreeg.’ Een echte “eye-opener” in dit proces was

“Je kon in de vroege jaren ’80 de sloten dempen met afgestudeerde historici.”Jaap-Jan Flinterman in 1976.

Een publicatie uit 2004 is volgens Flinterman de meest waardevolle bijdrage die hij aan het vakgebied heeft geleverd. Dit artikel ging over de verwachtingen ten aanzien van relaties tussen alleenheersers en sofisten, die heel verschillend waren van de reeds veel onderzochte relatie tussen alleenheersers en filosofen. Dit verschijnsel heeft hij aan de hand van een corpus teksten in kaart gebracht en na zijn promotieonderzoek is dit zijn meest geciteerde publicatie. ‘Daar ben ik nog steeds wel tevreden over.’ Met plezier denkt hij ook terug aan zijn bijdragen in het tijdschrift Lampas aan publieke debatten die op dat moment gaande waren. Daarnaast vindt hij het onderwijs dat hij aan generaties studenten heeft gegeven een belangrijke bijdrage aan het vak.

het boekje Greek Declamation van Donald Russell (1983), dat aan Flinterman eindelijk duidelijk maakte wat sofistische welsprekendheid precies inhield. ‘Dit werd door veel auteurs bekend verondersteld, maar dat was bij mij helemaal niet bekend.’

In de collegezaal

Wanneer Flinterman wordt gevraagd of hij meer plezier had in onderzoek doen of onderwijs geven, reageert hij met ‘een heel flauw antwoord, maar ik vind het allebei leuk. Ik heb een echte onderzoeksperiode gehad van drie jaar. Dat vond ik heerlijk en daar kan ik met een zekere weemoed aan terugdenken. Het is ook zo dat ik aan het eind van die periode, toch vooral een eenzame aangelegenheid, het leuk vond om dingen over mijn vakgebied uit te leggen. Daarnaast is het ook intellectueel verbredend. In principe is onderzoek heel erg gespecialiseerd, dus als je als historicus je breed wilt ontwikkelen, dan moet je onderwijs geven. Dan word je gedwongen om de breedte in te gaan.’

Over zijn promotieonderzoek zit Flinterman nog één enkel vraagstuk dwars. Dit betreft een van de bronnen, de memoires van een leerling van Apollonius, waarop Philostratus zijn Vita Apollonii zou hebben gebaseerd. Omdat deze herinneringen niet zijn overgeleverd en de biografie waarin ze besproken worden een sterk fictioneel karakter heeft, gaan historici ervan uit dat deze bron niet bestond en door Philostratus verzonnen is. Flinterman is de ‘kleinst mogelijke minderheid’ die ervoor openstaat dat het geschrift van Apollonius’ leerling niet volledig fictief is. ‘In die biografie zitten een aantal elementen die niet uit het standaardrepertoire van sofistische auteurs komen.’ Als voorbeeld noemt hij de ‘voorstellingen rond de relaties tussen koningen en filosofen in India. Die kom ik nergens tegen, behalve daar, en kloppen met bronnen uit India zelf. Dit is geen bewijs voor de realiteit van de bron, maar roept de vraag op waar het dan wel vandaan komt. Ik ben zelf nergens meer van overtuigd, ik weet het gewoon niet.’

Wat het plezier iets de kop in drukte was de duidelijk te merken verhoging van de werkdruk. Dit begon met de invoering van het bachelor-master systeem in 1999, waardoor er meer scripties moesten worden nagekeken dan bij het kandidaatdoctoraal systeem, gepaard met een toename van het aantal studenten. Daarbij kwam dat er vorig decennium op het HBO ook problemen waren met slechte scripties die toch een voldoende kregen. De reactie hierop was verdere bureaucratisering van het scriptieproces, zoals het nakijken door een tweede lezer. En kwamen de docenten uren tekort? Dan veranderde de tijd die zij hadden om een scriptie te begeleiden gewoon van twintig naar vijftien uur. ‘Tot 2015 heb ik het redelijk volgehouden om internationaal te publiceren, maar daarna is me dat niet meer echt gelukt. Het primaire beroep op je tijd is toch het onderwijs voor studenten.’

“Ik ben zelf nergens meer van overtuigd, ik weet het gewoon niet.”

“Als je als historicus je breed wilt ontwikkelen, dan moet je onderwijs geven.”

Reliëf met afbeelding van een retorische(?) declamatie, Ostia, Late Oudheid.

Mede dankzij deze verhoogde werkdruk verwelkomt

Flinterman zijn pensioen met open armen. ‘Ik vind het wel mooi geweest.’ Lang werken wordt doorgaans beloond met routine, maar met de komst van de door de VU en UvA gedeelde bachelors in oudheidstudies (ACASA) in 2017 en de Engelstalige bachelor geschiedenis in 2018, moest onderwijs plotseling in het Engels worden gegeven. In 2020 stond het onderwijs uiteraard op zijn kop en moest alles digitaal. Flinterman was dan ook erg blij met de hulp en ervaring van collega’s met het geven van grootschalig online onderwijs. ‘Ik werkte formeel maar drie dagen en daar was ik heel blij mee, want anders had ik in de weekenden moeten doorwerken.’

hij mensen in alle ernst hoort verdedigen dat de Grieken hun filosofie van de Egyptenaren hebben gestolen of dat slavernij een vroegmoderne Europese uitvinding is. ‘Het is altijd belangrijk om terug te kunnen grijpen naar het volledige onderliggende kennisapparaat, omdat alle claims die je maakt uiteindelijk daarop zijn gebaseerd.’

Een nieuwe fase

Ontmythologisering en demystificatie

Het mooiste bronmateriaal waarmee Flinterman heeft gewerkt is, misschien verrassend genoeg, niet afkomstig uit de oude geschiedenis, maar uit zijn doctoraalbijvakscriptie over de CPN en de Spaanse Burgeroorlog. In het verlengde daarvan heeft hij samen met medestudenten een aantal interviews met Nederlandse vrijwilligers in de Internationale Brigades afgenomen en aan de hand daarvan een monografie geschreven. ‘Dat is toch wel een aparte ervaring. Zeker over een onderwerp dat zelfs toen, 50 jaar na dato, al verzadigd was van legendevorming. Dit heeft niet zozeer te maken met de merites van het verhaal, maar met de historische sensatie. Sterker heb ik dat niet gehad. Die historische sensatie heb ik ook wel als ik over ruïnes wandel, maar dode stenen zijn toch wel anders dan levende mensen die tegelijkertijd ook al geschiedenis zijn.’