CODEX Historiae Rivalry & Friendship

Het nieuwe nummer van CODEX Historiae gaat volledig over Rivalry & Friendship! Voor veel mensen zullen deze begrippen met name associaties oproepen die te maken hebben met individuele vriendschappen en rivaliteiten. Relaties van vriendschappelijk- of vijandigheid bepalen immers hoe we ons verhouden tot andere personen. Door vriendschappen op te bouwen leren we niet alleen veel over onszelf en de ander, het zijn ook pijlers in ons leven die houvast geven en ons herinneren aan vroeger.Vriendschappen en rivaliteiten geven ons leven vorm, maar ze zijn ook te herkennen in de geschiedenis. Zijn niet alle oorlogen, veldslagen en religieuze strijden die hebben plaats gevonden in de wereld te herleiden naar relaties die werden gekenmerkt door vriendschap dan wel rivaliteit? Waar geschillen tussen staten gevolgen zijn van vijandelijke verstandhoudingen, zijn diplomatie en positieve internationale relaties juist uitingen van vriendschappelijke verhoudingen.

De redactie is zeer geïnspireerd geraakt door het brede thema van Rivalry & Friendship, waar de interessante artikelen in dit nummer het product van zijn. Sommige artikelen gaan over vriendschap en rivaliteit op een abstracter niveau. Lees bijvoorbeeld over de relatie tussen de geesteswetenschappen en de natuurwetenschappen of over de manier waarop we ons verhouden tot het koloniaal verleden in de openbare ruimte. Ook zijn er artikelen die juist een kijkje geven in het leven van historische individuen en hun vriendschappen, vijanden en passies.

Recent hebben we afscheid genomen van co-hoofdredacteur Claire. Gedurende ruim twee jaar bij CODEX heeft ze heel wat interessante en waardevolle bijdragen geleverd aan onze nummers. Wij danken haar hartelijk voor al het werk dat ze heeft gedaan. Voor mij is het de aanleiding om door te gaan als hoofdredacteur en ik zal mijn best doen om CODEX het leuke en leerzame studententijdschrift te laten blijven. Afgelopen jaar hebben we nieuwe mensen mogen verwelkomen in het CODEX team en hebben we afscheid genomen van anderen. Bij deze wil ik mededelen dat we in het aankomende academische jaar graag nieuwe studenten zouden willen verwelkomen. Wij zijn namelijk opzoek naar een vormgever en naar (eind)redacteuren. In dit nummer kun je meer lezen over wat de functies inhouden (lees: advertenties). CODEX geeft je de mogelijkheid om je op een laagdrempelige manier in een gezellig team te ontwikkelen en veel bij te leren. Ook zijn we altijd opzoek naar bijdragen van gastschrijvers, die kunnen bestaan uit een academisch artikel, opiniestuk, column of recensie. Bij vragen of interesse kun je ons mailen op info@codexhistoriae.nl.

The new issue of CODEX Historiae is all about Rivalry & Friendship! For many people, these concepts will evoke associations related to individual friends and foes. After all, relationships of friendship or hostility determine how we relate to other people. By building friendships we not only learn a lot about ourselves and the other, they can also be a cornerstone in our lives that gives us something to hold on to and reminds us of the past. Friendships and rivalries shape our lives, but they have also emerged throughout history. Are not all wars, battles, and religious struggles that have taken place in the world a consequence of relationships characterized by either friendship or rivalry? Disputes between states can be seen as the result of hostility, whereas diplomacy and positive international relations are expressions of friendly relations.

The editors got inspired by the broad theme of Rivalry & Friendship, of which led to the interesting articles in this issue. Some articles deal with friendship and rivalry on a more abstract level. You can read for example about the relationship between the humanities and the natural sciences or about the way in which we relate to the colonial past in the public space. Other articles instead give a glimpse into the lives of historical individuals and their friendships, competitors, and passions.

We recently said goodbye to co-editor-in-chief Claire. In her over two years at CODEX, she made many interesting and valuable contributions to our issues. We thank her very much for all the work she has done. For me it gives rise to continue as editor-in-chief and I will do my best to keep CODEX the fun and educational student magazine. Last year we welcomed new people to the CODEX team and said goodbye to others. I would like to inform you that we are eager to welcome new students into our team in the upcoming academic year.We are looking for a designer and (copy) editors. In this issue you can read more about what the positions contain (read: advertisements). Being a part of CODEX is the perfect opportunity to develop yourself and to learn a lot in a friendly and accessible environment. Moreover, we are always looking for contributions from guest writers, which can consist of an academic article, opinion piece, column, or review. If you have any questions or if you are interested, don’t hesitate to send us an email at info@codexhistoriae.nl.

The deadline for the next issue,‘Sacrifice’, is the 29th of September.

Leah Niederhausen

Thymo Gieltjes

Nica de Korte

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller

When Rivalry Turns into Friendship

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, by Peter Kropotkin

An Introduction to Co-operative Evolutionary Theory

Kunst voor staat en volk Patronaat en koning Ludwig I

Op de VU / At the VU

Niels Koopmans

Merlijn Update

Eva van Roozendaal

Thymo Gieltjes

Being the Killjoy of Your Date Taking Down Statues and Coming to Terms With Our Past

Het kerkgebouw als massagraf

De rol van het christendom in de genocide van Rwanda

Brenno Mulder

Thymo Gieltjes

Zorgen Snaps voor gelukkige vrienden? Aristoteles tegenover Snapchat

Bridging the Gap between ‘Humanities’ and ‘Sciences’

The Reunification of Sciences through the Mind

Pagina 4

Pagina 5

Pagina 9

Pagina 12

Pagina 17

Pagina 19

Pagina 21

Pagina 26

Pagina 30

Suzanne van Bart Pagina 34

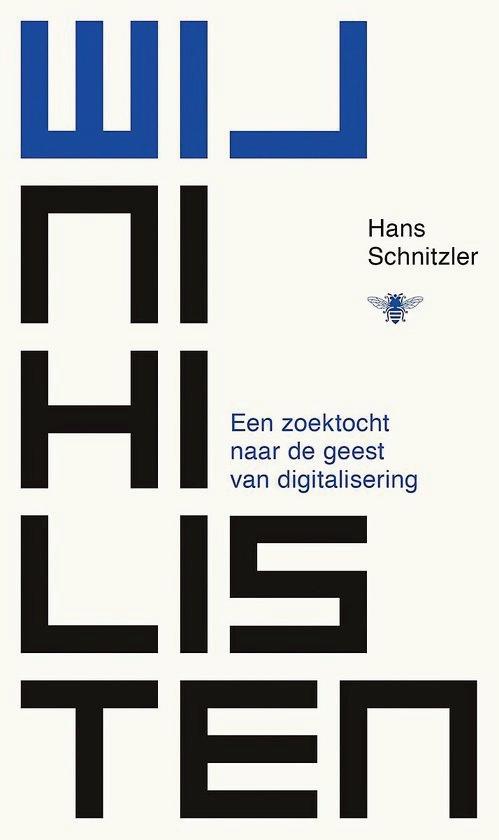

Wij nihilisten: van Nietzsche tot Nerd Hoe verhoudt jouw mens-zijn zich tot een gedigitaliseerde wereld?

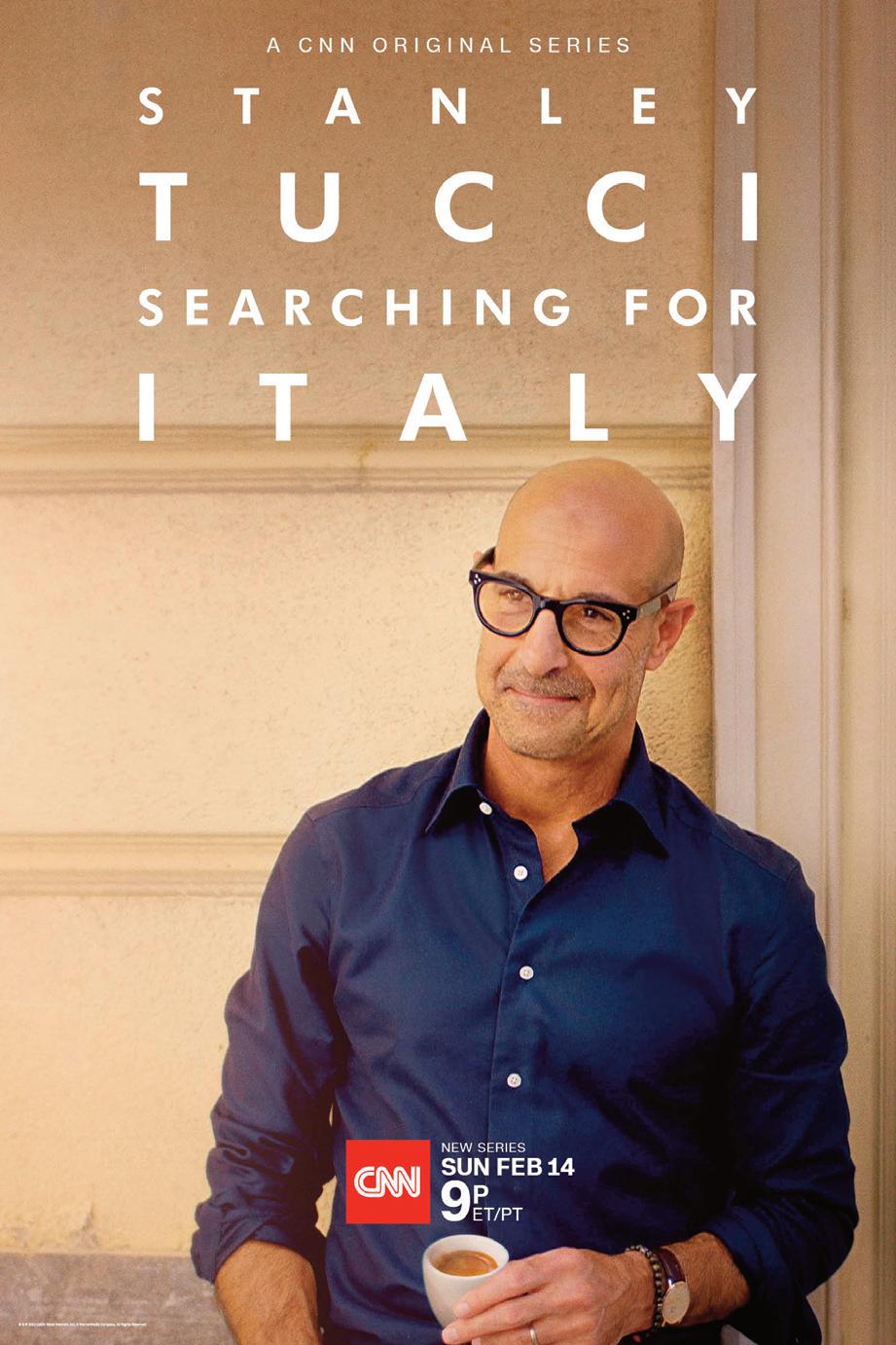

Italians and Their Food Travelling across Italy with Stanley Tucci Nica de Korte

36

The ‘Actualiteiten’ section in CODEX is making a comeback this issue! You might find yourself with some extra free time this summer. If you are looking for educational and fun places to visit, feel free to take inspiration from our recommendations below.

While the building that houses the Amsterdam Museum is undergoing a large-scale renovation, the museum has found a temporary home in the Hermitage. In the Amsterdam Museum Wing that opened there, you will find exhibitions with objects and works about the history of Amsterdam, ranging from very historical to the new neighbourhoods and citizens.The exhibition spaces of the Amsterdam Museum in the Hermitage will be open until 2025.

The Allard Pierson Museum opened an exhibition about the musicals that were created by Annie M.G. Schmidt and Harry Bannink during the years between 1965 and 1984. The exhibition Zeur niet! (Don’t whine!) is open until 30 October. It offers plenty of authentic materials, ranging from costumes to audio and video fragments, and gives an interesting view to first musicals that were created in the Netherlands.

The Tropenmuseum recently opened its new permanent exhibition Our Colonial Inheritance, which centers around the history of colonialism and its traces in the social structures and relationships in the world of today. With artifacts and objects from the museum’s collection as well as newly created artworks, the displays focus mostly on the colonial past of the Netherlands.

The month of October is devoted this year again to the Maand van de Geschiedenis (History Month). Take a look at the website maandvandegeschiedenis.nl for an overview of the many activities that take place in October all over the Netherlands.

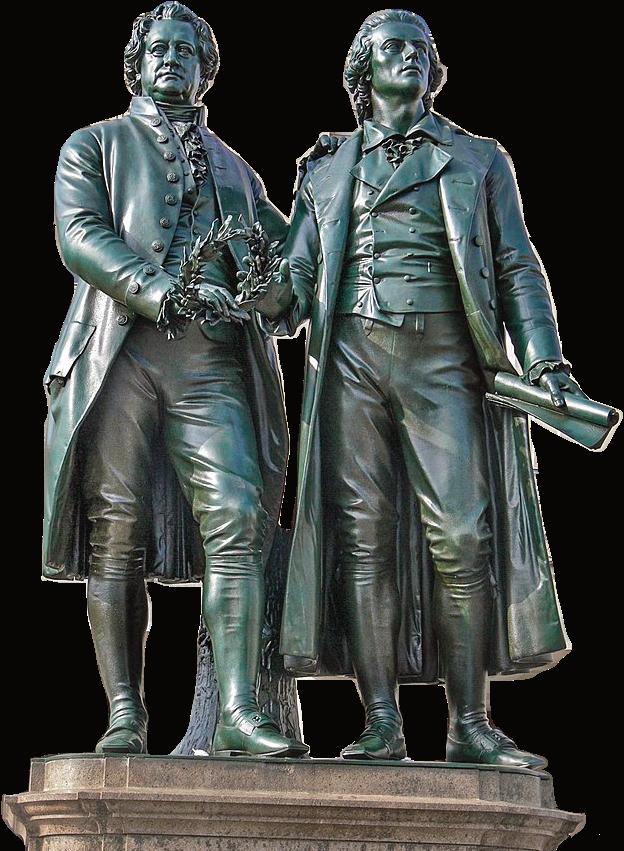

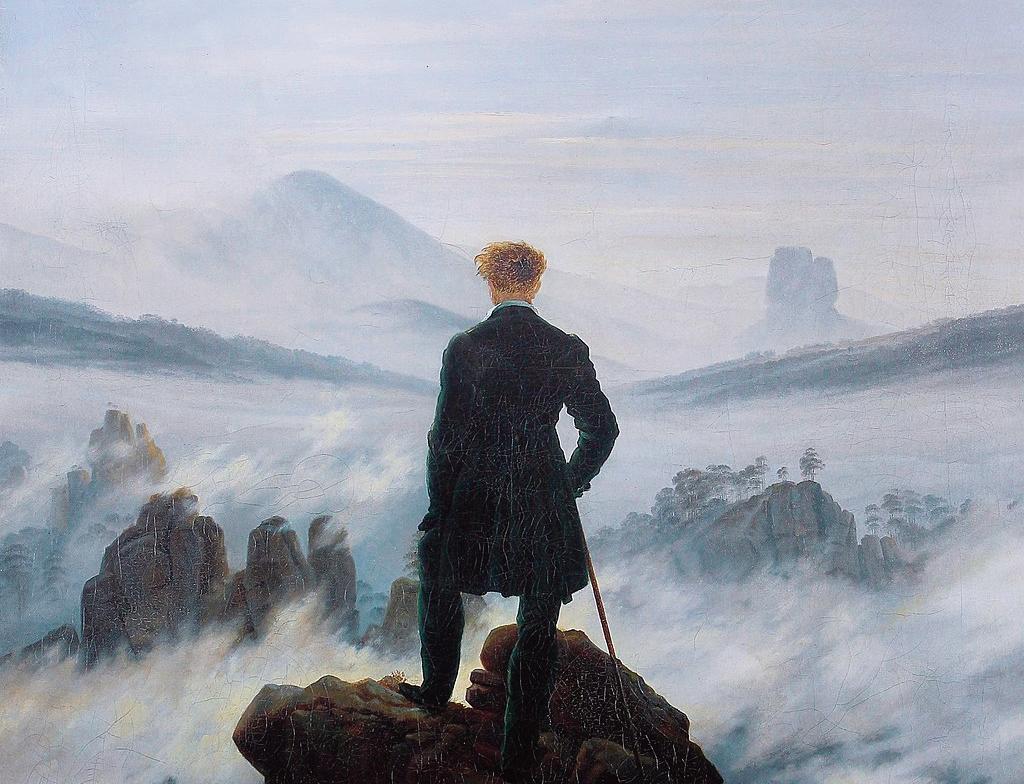

In front of the German National Theatre in the city of Weimar stands a monument which can hardly be surpassed in terms of fame and recognition in Germany: The Goethe-Schiller Monument. Created in 1857 by sculptor Ernst Rietschel (1804–1861), the bronze monument shows the larger-than-life statues of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805).These two men can be considered the most famous and influential German writers of all time, originators of such fundamental eposes as Faustus (1808/1832) and The Maid of Orleans (1801).The inscription on a bronze plaquette underneath the statues reads: “To the poet couple / Goethe and Schiller / the fatherland”,1 highlighting the deep and profound friendship that connected the two writers. However, they had not always been friends. In fact, it had been quite the contrary. In the first years of their acquaintance they had seen each other as big rivals.

Goethe and Schiller first met briefly in 1788.2 At the time, Goethe already was one of, if not the most successful German writer of his time, having immense success with works like Sorrows of Young Werther in 1774. After having been invited by the Duke of Saxe-Weimar in 1775 to become part of his court, Goethe served as the duke’s privy council, chief advisor, and head of the war commission which led him to move in the highest social circles. In 1782, he was ennobled and from then on went under the name of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, an outsized honour as this expressed his elevation to nobility. When he met Schiller in 1788, he had just returned from an inspirational two-year journey to Italy and he was at the peak of his literary production and societal recognition.

Friedrich Schiller, on the other hand, ten years younger than Goethe, was a young rising and impetuous poet who had just celebrated his first major success with the radical play The Robbers in 1781. Schiller admired the famous Goethe, the latter, however, paid little attention to the youngster. He was too

settled for the turmoil in Schiller’s work and found it naïve, childish even. In a letter to a friend, Schiller expressed his disappointment with Goethe’s lack of interest, calling him extremely selfish. Schiller aspired to overcome Goethe, who he thought had been given an unfair advantage, having come from a privileged family, whereas Schiller himself had had to work harder for his recognition.3 Goethe shared these hostile feelings as he claimed to hate and despise Schiller. For the following years they had no relevant contact and witnessed each other’s success from a distance, until Schiller reached out to Goethe again in 1794 to ask him to participate in Schiller’s new literary magazine.4

Goethe accepted the invitation and, in the summer of 1794, the two met for and had an extensive conversation after a dinner event in Jena, next to Weimar.5 At the time,Weimar was the epicentre of German intellectual and artistic thought, influenced by scholars like Christoph Martin Wieland (1733–1813) or Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803). Inspired by their first con-

versation, Goethe and Schiller started exchanging extensive letters, asking each other for professional advice, comments, and edits to their current projects. Soon, their professional relationship turned into a deep friendship, they met frequently, and after Schiller’s move to Weimar in 1799, Goethe was seen at the Schiller household a lot. He would always bring some sort of gift to the kitchen and often stayed until the early mornings, the two would discuss and laugh so loud that Schiller’s wife Charlotte often saw herself obliged to close the windows to not wake up the entire neighbourhood. Whereas in the beginning of their relationship, literary and philosophical topics had been the focus, the two poets now often turned to day-to-day events, such as the fixing of a broken roof, vaccinations for the children or various celebrations.

Thereby, their friendship united two very different characters: two complementary opposites. Goethe was settled in his life, enjoyed the high social circles he had moved into, and he found solace in the beauty and simplicity of nature. Schiller, however, was impetuous and restless. He often felt uncomfortable in society, striving for dialogical reflection and philosophy rather than monological comfort and rational science. For Goethe, literature and art were an escape from rev olution and politics, for Schiller the arts where his political stage. Goethe lived a rather healthy lifestyle, whereas Schiller’s life was marked by cof fee, alcohol, tobacco, little sleep, and sickness. In his desk, he would always keep some mouldy apples as he said their smell would in spire him. Goethe, on the other hand, got sick of the smell.6

However, both of them found in the other a miss ing link to their life. Schiller saw in Goethe a mentor that allowed him to sort and reflect on his vigorous thoughts. Goethe found in Schiller new youthful aspir ations. As he stated in a letter to Schiller: “You have given me a second youth and made me a poet again, which I had almost ceased to

be.”7 Both of them had connected with their partner in spirit, feeling deeply understood as well as challenged. Together, they developed an extensive number of ideas, always being each other’s harshest critic and most loyal supporter. Goethe’s journey to Switzerland in 1797 served as inspiration for Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell and Schiller’s criticism had a significant effect on Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. 8

In 1797, the two also started publishing poems together. Their collaboration was so significant such that, to this day, it is not always clear who wrote which verse, showing how familiar they were with each other’s writing style. Goethe highlights this collaboration in their shared works: “Often, I had the thought and Schiller did the verse, often it was the other way round and Schiller did one verse and I did the other. How can there be any talk of mine and yours!”9 Furthermore, they together made alterations to Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” which Ludwig Beethoven would incorporate in his 9th Symphony years later and today serves as the official symphony of the European Union.

In May 1805, their close friendship came to a sudden end when Schiller died after a prolonged sickness when he was only 45 years old. Goethe could not overcome the loss of his closest friend and companion, locking himself inside for weeks, refusing to speak to anyone. Schiller’s death meant a deep caesura for him. In a letter he said that losing Schiller was like losing half his life and being. Schiller was buried at the Weimar cemetery for 20 years

“Together, they developed an extensive number of ideas, always being each other’s harshest critic and most loyal supporter.”(II) Goethe-Schiller Monument, Weimar

until the cemetery was later shut down. Consequently, Schiller’s mortal remains were excavated and until his reburial, Goethe kept the skull of his friend in his office. Schiller was reburied at the new Weimar cemetery where Goethe joined him years later. He had requested to be laid next to Schiller so that they could be united again.10 However, in 2008 researchers made public that the remains in Schiller’s casket were in fact not his and that there must have been a mistake at his excavation 200 years earlier. Since then, Schiller’s casket next to that of Goethe remains empty.11

Friedrich Schiller and Johan Wolfgang von Goethe are the most known, successful, and influential German writers of all time and together they shaped an entire literary genre of Weimar Classicism.Thereby, they not only fundamentally influenced German and European literature to this day but also deeply impacted each other’s life on a professional and personal level. Their friendship developed from an intense rivalry into a deep comradeship. Ernst Rietschel materialised this friendship in the Goethe-Schiller Monument in Weimar. Despite having had a significant height difference (Schiller was 1,90m; Goethe 1,69m), they are portrayed on one level and eye to eye as they were in life, work, and friendship.

1 Goethe-Schiller-Monument Weimar.

2 Gregor Delvaux de Fenffe, “Schiller und Goethe”, WDR, 2020, https://www.planet-wissen.de/geschichte/persoenlichkeiten/friedrich_schiller/pwieschillerundgoethe100.html, last accessed April 22, 2022.

3 Wolfgang Schneider, “Sie haben ‚mich wieder zum Dichter gemacht‘“, Deutschlandfunk, 2009, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/sie-haben-mich-wieder-zum-dichter-gemacht100.html, last accessed April 22, 2022.

4 Delvaux de Fenffe, 2020.

5 Schneider, 2009.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid, original: „Sie haben mir eine zweite Jugend verschafft und mich wieder zum Dichter gemacht, welches zu sein ich so gut als aufgehört hatte.“

8 Ibid.

9 Johann Peter Eckermann, “Gespräche mit Goethe in den letzten Jahren seines Lebens“, Projekt Gutenberg, https://www.projektgutenberg.org/eckerman/gesprche/gsp2014.html, last accessed April 22, 2022, original: “Oft hatte ich den Gedanken und Schiller machte die Verse, oft war das Umgekehrte der Fall, und oft machte Schiller den einen Vers und ich den anderen. Wie kann nun da von Mein und Dein die Rede sein!”

10 Ursula Homann, “Schillers Tod”, Eines Freundes Freund zu sein, https://ursulahomann.de/EinesFreundesFreundZuSeinUeberDi eFreundschaftVonGoetheUndSchiller/kap005.html, last accessed April 22, 2022.

11 “Der historische Friedhof in Weimar,” https://www.stilvollegrabsteine.de/ratgeber/friedhof-weimar/, last accessed April 22, 2022.

(I) Photo by Flickr-user Wwwuppertal, October 2017, https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwwuppertal/26450812238.

(II) Photo by Wikipedia Common-user MjFe, “The Goethe and Schiller statue in Weimar in front of the National Theater”, October 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goethe_Schiller_We imar_3.jpg.

(III) Photo by Wikipedia Commons-user Karl-Heinz Meurer, “Die Särge Gothes und Schillers in der Weimarer Fürstengruft”, May 2009, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Särge_Goethe_und_ Schiller.jpg.

Ben je creatief? Heb je een scherp oog voor grafische vormgeving? Lijkt het je leuk om het gezellige CODEX team te versterken? Dan zijn wij op zoek naar jou!

Als vormgever tover je levensloze tekstdocumenten om tot een professioneel tijdschrift dat duidelijk in elkaar steekt en roept om gelezen te worden!

Ervaring met grafisch ontwerp is niet nodig, wel een vastberadenheid om te leren en jezelf te ontwikkelen.

Interesse of vragen? Mail ons vooral: info@codexhistoriae.nl

Are you creative? Do you have a sharp eye for graphic design? Are you interested in joining the fun CODEX team? Than we're looking for you!

As graphic designer, you will turn dull text documents into a beautiful, lifely and professional magazine that's inviting to read.

Previous experience in graphic design is not required, a desire to learn and develop is.

Are you interested or do you have any questions? Send us an email: info@codexhistoriae.nl

Three years ago, historian Rutger Bregman released a book that completely changed the public perception of human nature and history. Its English translation, published two years later, is called Humankind: A Hopeful History, but its Dutch title can most aptly be translated as Most People Are Okay or Most People Are Good – the Dutch verb deugen in the original title meaning as much as ‘being a good person, showing socially acceptable behavior’. In his book, Bregman proposes that the majority of people is good-natured, and that millennia of cultural conditioning, often elitist in nature, have convinced us otherwise. One can think of the myriad spiritual leaders, rulers, and scientists throughout history that have advocated that man is predominantly sinning, egotistic, and self-centered. However, man is also a social creature, that has co-operated and supported others according to Bregman – and rightly so – more so than his negative actions.

Bregman’s book sold like hot cakes in the Netherlands and abroad. Its revisionist outlook was seen as revolutionary, especially by the public. However, more than a century earlier, Bregman’s views were already advocated for by another author, one that went further and encompassed more of mankind’s history than Bregman did.

The Scientific Landscape of the Early 1900s

The year is 1902. In fin de siècle Europe, the specter of Darwinism haunts the (pseudo-)scientific landscape, influencing biology, ecology, psychology, and anthropology, amongst other disciplines. As one of the founders of modern science, Charles Darwin (1809-1882) changed the way we see the world, forever steering science’s course away from creationism and alternative theories like Lamarckism. Darwin’s influence on knowledge cannot be understated.

However, another Pandora’s box was opened, unintended by Darwin himself – namely, that of social Darwinism. This theory reinforced not only colonialist viewpoints, but those of a more capitalist nature as well: some people simply lost a ‘struggle for existence’, and this meant that they deserved less. The natural life of humans was competi-

tive, or, in Hobbes’ famous phrasing: ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’.1 We were trapped in a battle from birth until death, toiling and fighting to ensure our survival, and most importantly, doing so alone. We could co-operate, but only out of shallow self-interest. Moreover, some races of man were better equipped in this fight than others and, as such, it was only logical that some were to dominate and some were to be dominated. It is no wonder that eugenics came into being in this era.

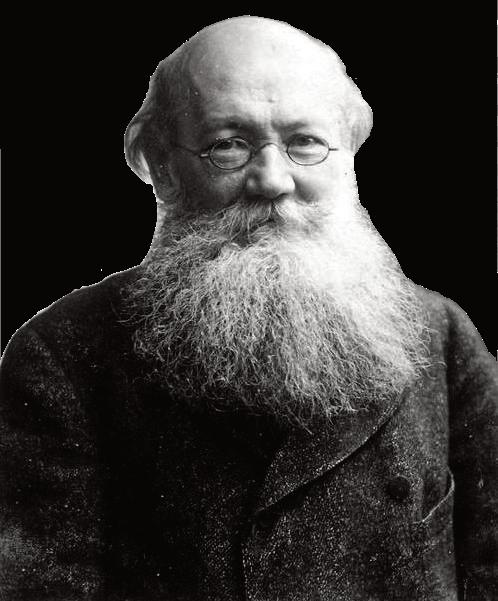

However, in these turbulent times, where the dearth of true science could not have a larger impact, already a voice cried out for change. That voice belonged to the Russian geologist, ecologist, and political thinker Peter Kropotkin (18421921) who, after seeing where evolutionary biology was heading, advocated for a different theory from the mainstream interpretation of Darwin: one that emphasised cooperation instead of conflict. ‘Conflict’ is used here to mean: accomplishing a goal out of self-interest and doing so in a competitive manner, which allows some people to win and others to lose; others may only join in to temporarily aid

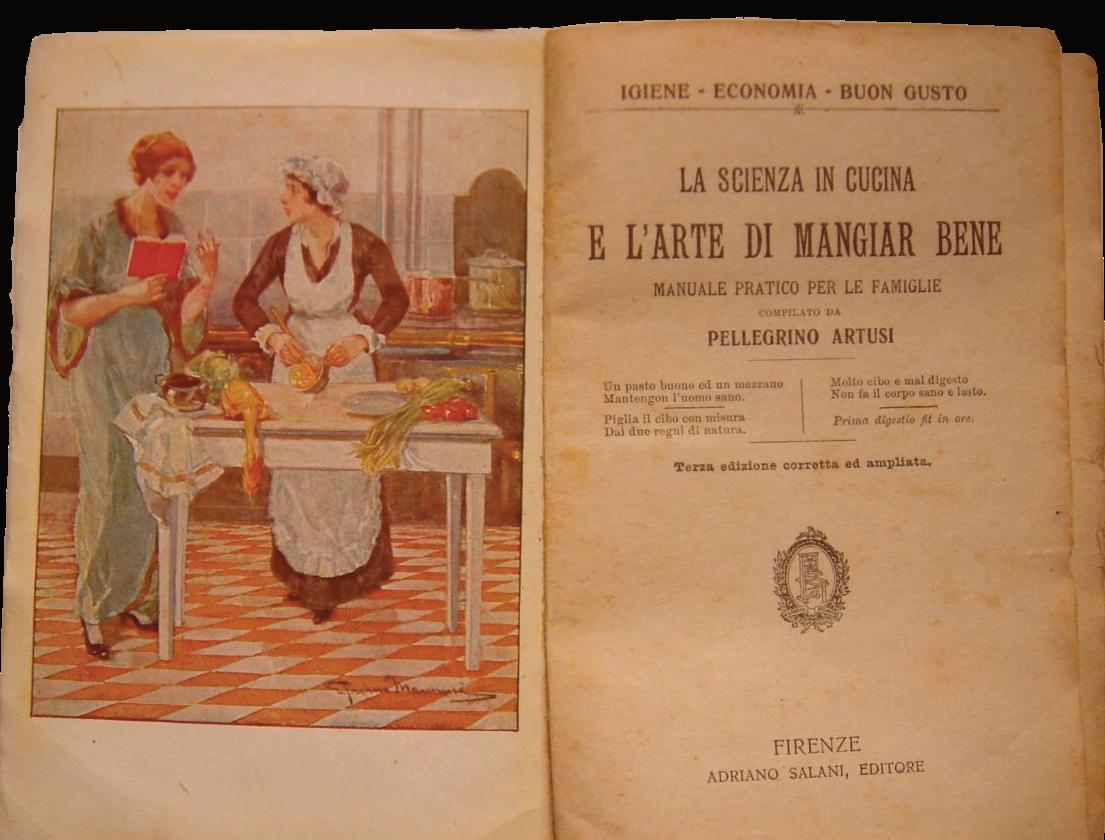

(I) The title page of the 1902 edition of Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

Peter Kropotkin’s anarchist viewpoints form the basis of his writings. His form of anarchism is now most often called ‘anarchocommunism’, meaning an ideology which advocates for a stateless society, organised in communes. These communes, according to Kropotkin, should be based on the principles of equality, freedom and – naturally – mutual aid and co-operation. This is the way that ordinary people (as opposed to ‘history-makers’ like kings and other political leaders) have lived for the majority of history. According to Kropotkin, this was by no means an idyllic, carefree life, but is rather the most preferable, especially when considering today’s technological advances which could support this life. Nowadays, most technical advancement serves a statist system, but Kropotkin argues that it can also be used to enhance a more ‘natural’ lifestyle.4

this quest of self-centeredness, and of course out of their respective egotism. Kropotkin was of the conviction that co-operative tendencies were more influential in evolution than conflict, i.e. that the ability to form social bonds and to work together as individuals was more decisive in the ‘struggle for existence’ than physical strength.

In this light, Kropotkin wrote a book, called Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, in which he described his new theory through empirical evidence. Most striking is, however, that the theory is applied on both animals and humans: starting with the simplest of animals and working up through human history, Kropotkin describes how – time and time again – it is co-operation, not conflict, which sustains and builds life. In describing this, he shows that co-operation precedes sapience.

The first two chapters concern mutual aid among animals. In beautiful English prose, the likes of which are seldom seen in contemporary scientific texts, Kropotkin makes it clear that Darwin’s ‘survival of the fittest’ has little to do with individual

fitness, but with that of the group. Of equal importance is the fact that fitness does not necessarily mean physical fitness, something that Darwin also indicated in later works.

Fitness can also mean the ability to work together as a group to accomplish common goals.The individual ant worker is incapable of achieving much, but by working together with other members of its species, it can form grand structures, kill prey much bigger than itself, and secure the existence of its kind. More often than not, individuals turn to groups (be it in mating seasons, migration periods, hunting parties, or simply all the time) to perform tasks that are greater than the sum of their parts, i.e. the individuals. This holistic method can be seen all throughout the animal kingdom and allows many species to thrive.

In the conclusion of chapter II, Kropotkin eloquently encapsulates the overarching theme of the first portion of Mutual Aid: ‘[Co-operation instead of competition] is the tendency of nature, not always realised in full, but always present. That is the watchword which comes to us from the bush, the forest, the river, the ocean. “Therefore combine—practise mutual aid! That is the surest means for giving to each and to all the greatest safety, the best guarantee of existence and progress, bodily, intellectual, and moral.” That is what Nature teaches us; and that is what all those animals which have attained the highest position in the respective classes have done.’2

After treating the animal kingdom, Kropotkin turns to human beings, to whom about three-quarters of the book is dedicated. In describing humans, Kropotkin focuses on the genesis of human society, seeing it as the culmination of co-operative efforts instead of a kind of ‘great-men theory’, the likes of which are often advocated for by historians. There was no noble king

“This interesting topology stems from Kropotkin’s focus on the commoner, the peasant, the everyday man.”

who subjugated wild man to his ideals of tranquil civilization; instead, man was always able to enjoy peaceful life himself, only turning to large-scale violence through authoritarian leaders. In this, Kropotkin’s anarchist roots are laid bare for all to see –not that he does not make his anarchist sympathies clear from the beginning. The book is intertwined with his political philosophy, advocating that anarchism stems from human evolutionary nature.

Kropotkin divides human history into four phases: that of the savages, the barbarians, the medieval cities and modern times. This interesting topology stems from Kropotkin’s focus on the commoner, the peasant, the everyday man. For example: the only difference the fall of the Western Roman Empire brought, according to Kropotkin, was that it gradually paved the way for the medieval city to rise up – no large-scale power alterations are described. In Kropotkin’s vision, it is always normal people, working together according to the principle of mutual aid, who shape history. Rulers and states mostly function to hamper this development. In this, his anarchist philosophy can again be deduced.

Kropotkin does not deny the presence of conflict within the animal or human world. He does emphasise, however, that cooperation is a much stronger and constructive force that supports life to a greater extent than conflict does or can do. Furthermore, he states that the focus on conflict is drastically disproportional, because practically no attention is paid to the enormous amount of mutual aid.This message is extraordinarily

similar to that of Bregman’s book, but more revolutionary due to its publishing date being more than a century before that of the aforementioned. Even in modern times, Kropotkin is still influential in the field of sociology, anthropology, and biology, being endorsed by thinkers such as Stephen J. Gould.3 In the confusing world of early twentieth-century Europe, Kropotkin spread a message of hope, optimism, and man’s innate ability to do good; a message we can still hold on to in the present, and for which we still have need.

1 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651) i. xiii. 9.

2 Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, Mutual Aid. A Factor of Evolution (unknown edition; New York, 2006) 61.

3 Stephen Jay Gould, ‘Kropotkin was no crackpot’, Natural History 97:7 (Research Triangle Park 1997) 12-21.

4 Cf. Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, La Conquête du Pain (Paris 1892).

Images

(I) https://archive.org/details/mutualaidafacto00knigoog/ page/n6/mode/2up, public domain (property of Harvard University, digitised by Google.

(II) Photograph by Nadar, c. 1900, public domain (property of the New York Public Library).

Do you want to publish a written piece? This is your chance!

CODEX regularly publishes articles by students based on their academic essays, papers or theses. You are also welcome to submit a review, opinion piece or column.

Are you interested? Send an email to info@codexhistoriae.nl with your (idea for an) article and perhaps your name will appear in the next issue of CODEX Historiae!

*Statistic is not scientifically proven, but it is true!

(I) Kroonprins Ludwig (tweede van links) met andere welgestelden en kunstenaars in een Spaanse wijnbar in Rome.

het schilderij van Franz Ludwig Catel (1778-1856) uit 1824 is een voorstelling te zien van een aantal welgestelde mannen die vanuit Duitsland op reis waren in Italië, in het bijzonder naar Rome. De groep bevindt zich in een Spaanse bar in de stad en bestelt een fles wijn. Het is niet op te merken uit het schilderij, maar de man die de fles uitkiest is de latere koning van Beieren, Ludwig I (1786-1868). De toen nog jonge kroonprins zit aan een tafel, waar hij omringd is door kunstenaars. De kroonprins had al vanaf jonge leeftijd een grote voorliefde gekend voor kunst en cultuur, iets waar hij zijn hele leven mee bezig zou blijven. Uit het schilderij, dat werd gemaakt in opdracht van Ludwig, blijkt hoe de kroonprins zichzelf positioneerde binnen de kunstwereld. Ludwig staat op gelijke voet met de kunstenaars die hij ontmoette. Bovendien bewonderde hij hen en het werk dat ze maakten.1 Waar kwam deze liefde vandaan en welke rol speelde zijn patronage voor de kunsten in zijn periode op de troon?

Ludwig I was pas de tweede koning van Beieren en had de politieke functie van zijn familie tijdens zijn leven zien veranderen. Zijn vader, Maximiliaan Jozef (1756-1825), werd in 1799 de keurvorst van Beieren. Hoewel hij slechts uit een zijtak van het huis Wittelsbach stamde, het vorstenhuis dat de graven en hertogen van Beieren leverde, werd hij toch de wettelijke troonopvolger. Toen Napoleon in 1805 in strijd was met Oostenrijk en Pruisen, sloot Maximiliaan een handige alliantie met de Franse keizer. Met steun van Napoleon werd Beieren een jaar later verheven tot een koninkrijk. Het territorium van de staat werd uitgebreid en Maximiliaan kreeg de koningstitel. Maar de hoofdstad München, waar tevens de vorstelijke residentie was gevestigd, sloot vanwege zijn middeleeuwse karakter nog niet aan bij de

visie die Maximiliaan had voor zijn koninkrijk. Daarom gaf hij de aanzet voor de vernieuwing en uitbreiding van de stad, waar in de jaren die volgden vele transformaties zouden plaatsvinden.2 Daarnaast had Maximiliaan een interesse in kunst en verzamelde hij een collectie van belangrijke schilderijen. Onder hem groeide ook de collectie van de koninklijke galerij.3

Troonopvolger prins Ludwig, de zoon van Maximiliaan, had een nog grotere passie voor kunst en cultuur dan zijn vader. Hij werd geboren in 1786 en had tijdens zijn jeugd oorlog en revolutie meegemaakt. Hoewel Napoleon veel had betekend voor de staat Beieren, voelde Ludwig vanuit nationalistisch sentiment juist verontwaardiging tegenover de Fransman. In politiek op-

zicht was Ludwig conservatief, aangezien hij de monarchie in stand wilde houden en zich daarbij verzette tegen uitbreiding van de volksvertegenwoordiging.4 Zijn onderwijs had met name bestaan uit lessen van privédocenten. In zijn latere opvoeding had Ludwig bovendien kunnen profiteren van het nieuwe onderwijs dat werd aangeboden op de universiteiten van Göttingen en Landshut. De ervaringen die Ludwig als jonge prins het meest hadden gevormd waren echter de reizen die hij had gemaakt door Europa. In 1804 en 1805 bracht Ludwig enkele maanden door in Italië, waar zijn levenslange passie voor kunst werd aangewakkerd. Bij de eeuwenoude Italiaanse monumenten en in de met kunst gevulde villa’s van de Romeinse adel vond Ludwig een boeiende wereld die hem onbeperkte fascinatie bood.5

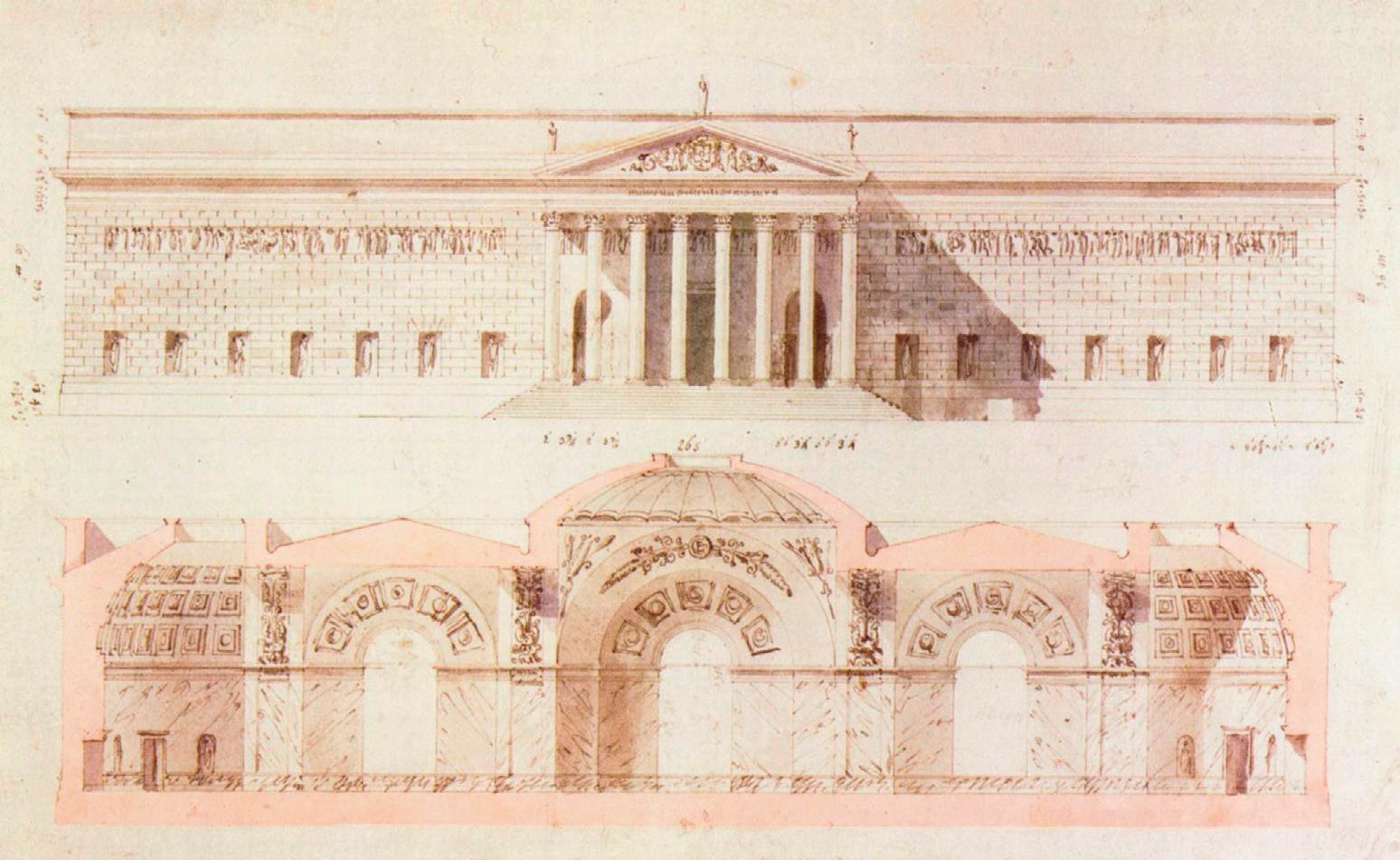

het belangrijk dat zijn grote kunstcollectie openbaar was voor het volk. Zelfs “de saaiste van de massa” konden volgens Ludwig verrijkt en verlicht worden door in contact te komen met kunst.7 In de nieuwe straten waarmee Maximiliaan de stad München had uitgebreid, liet Ludwig daarom musea bouwen waar hij de koninklijke collectie tentoonstelde. Deze musea zouden worden vormgegeven met uitgedachte architectuur waar de aandacht voor kunst en cultuur van de kroonprins in werd gereflecteerd. De eerste hiervan was de Glyptothek. Dit museum was bedoeld voor de expositie van de koninklijke sculpturencollectie van het oude Griekenland. Een groot deel van de beelden uit Ludwigs collectie waren afkomstig uit de Tempel van Aphaia op het Griekse eiland Aegina, die aan het begin van de negentiende eeuw voor het eerst was opgegraven. Op verzoek van de prins maakte de architect Leo von Klenze, (1784-1864) die hij eerder had ontmoet in Parijs, het ontwerp voor de Glyptothek.8

Hoewel kunst voor Ludwig het perfecte toevluchtsoord was wanneer zijn frustraties over zijn verplichtingen als troonopvolger opliepen, had het voor hem ook een diepere betekenis. Waar hij zich in de meeste sociale situaties vrij onhandig manoeuvreerde, gezien zijn slechthorendheid en spraakproblemen, vormde kunst een wereld die hij zich eigen kon maken. Het was een manier om tijd te doden en zijn fysieke tekortkomingen te compenseren, maar Ludwig zag de kunsten ook als iets met inherente waarde. In de kunst die hij als kroonprins en later als koning verzamelde en die hij in opdracht van hem liet maken, waren zijn meest fundamentele waarden weerspiegeld. Het waren vertegenwoordigingen van zijn christelijk geloof, zijn verbintenis met de Duitse cultuur, en zijn doel om het prestige van de Wittelsbach-dynastie te behouden en te vergroten. Op deze manier was de patronage van de kunsten voor Ludwig een manier om bij te dragen aan het welzijn van zijn staat en probeerde hij daarmee zijn eigen plaats in de geschiedenis te markeren.6

Met geld van de staat, van zijn vader of uit zijn privéinkomsten kocht Ludwig veel kunstwerken aan, van schilderijen tot beeldhouwwerken, en al snel had hij een wezenlijke collectie bij elkaar gebracht. Aangezien Ludwig er sterk van overtuigd was dat de staat verantwoordelijk was voor de educatie en ontwikkeling van zijn inwoners, vond hij

De bouw begon in 1815, maar het zou tot 1830 duren tot het complexe project gereed was. Voor een deel kan dit verklaard worden door de veeleisende Ludwig, die bij elke stap van het bouwproces betrokken was en zich persoonlijk boog over de talloze details. Bovendien was hij als kroonprins nog altijd afhankelijk van de toestemming van zijn vader, wat het proces niet bevorderde. Dit veranderde in 1825 toen Ludwig koning werd, maar hij bleef beperkt door de grondwet die grenzen stelde aan zijn macht. De werkwijze van Ludwig en de manier waarop hij met zijn architecten samen wilde werken, droegen ook bij aan de vertraging van het bouwproces van de Glyptothek als eerste museum. Ludwig wilde niet alleen een patroon zijn die zijn kunstenaars opdrachten gaf en van inkomsten voorzag, zoals de relatie met zijn kleermakers of koks eruitzag. In plaats daarvan wilde hij een actieve deelnemer zijn, die een bijdrage leverde

“De patronage van de kunsten was voor Ludwig een manier om bij te dragen aan het welzijn van zijn staat en om zijn eigen plaats in de geschiedenis te markeren.”(II) De Glyptothek in München, ontworpen door Leo von Klenze en gebouwd tussen 1815 en 1830.

aan het scheppingsproces. Hierdoor werkte hij bij de Glyptothek samen met Klenze en ging hij soms in tegen zijn artistieke adviseurs of tegen de architect zelf. Ludwig en Klenze wisselden gedurende het hele bouwproces bijna vijfhonderd brieven uit over verschillende structurele en esthetische vragen.9

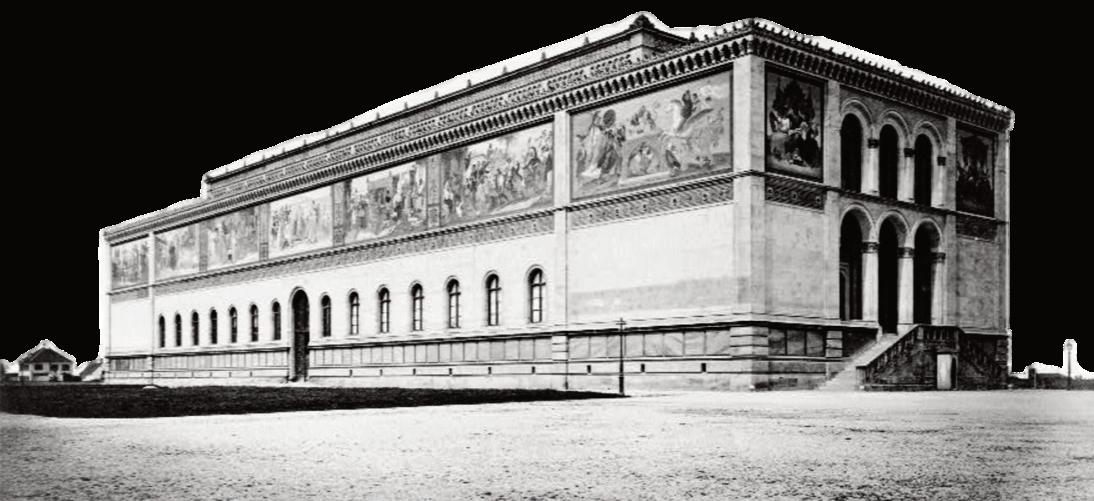

De grote reikwijdte van Ludwigs interesse werd weerspiegeld in de enorme tijdspanne van zijn collecties, die bijna de hele westerse kunstgeschiedenis omvatte. In lijn met zijn negentiende-eeuwse tijdgenoten had hij grote belangstelling voor de klassieke oudheid. Daarnaast had Ludwig een voorliefde voor alles wat Italiaans was en had hij ook werken uit de renaissance en barok.10 Bovendien hield hij zich bezig met de kunst in zijn eigen tijd: hij kocht werken van negentiende-eeuwse Duitse kunstenaars en gaf hun opdrachten voor nieuwe schilderijen. Voor de collectie eigentijdse kunst liet Ludwig vanaf 1846 een nieuw museum bouwen: de Neue Pinakothek. Dit nieuwe museum was bedoeld voor schilderijen uit zijn huidige eeuw en uit de toekomstige eeuwen. Het was Ludwigs bedoeling om met zijn patronage van de kunsten een nieuwe opbloei teweeg te brengen, vergelijkbaar met de renaissance, maar dit keer in Duitsland. Dit narratief moest worden afgebeeld aan de buitenkant van het gebouw door middel van fresco’s.

Op de bovenste helft van de Neue Pinakothek, gebaseerd op de Italiaanse romaanse en vroege renaissancestijlen, kwamen negentien muurschilderingen, ontworpen door Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874).11 De verschillende fresco’s verbeelden samen een duidelijk verhaal. Eerst wordt duidelijk dat er in de

achttiende eeuw sprake was van een artistiek verval in Duitsland. Ludwig wil hier verandering in brengen en geeft Duitse kunstenaars de mogelijkheid om naar Rome te reizen, waar zij kennis op doen over architectuur, beeldhouwen en schilderen. Vervolgens verbeteren hun technieken en keren ze terug naar Duitsland, waar ze opdrachten krijgen van de koning en zich een nieuwe wedergeboorte van de kunsten ontplooit. Op de centrale muurschildering staan zowel Ludwig als Duitse kunstenaars uit zijn tijd. Kaulbach heeft van dit centrale schilderij een mooie weerspiegeling gemaakt van de wijze waarop Ludwig zich relateerde aan kunst en kunstenaars. De koning stapt van zijn troon af om zich bij de kunstenaars die hun werk presenteren te voegen. Hier verbeeldt Ludwig opnieuw zijn verbondenheid met de kunstwereld en laat hij zien er niet alleen boven te staan als opdrachtgever, maar toont hij aan zelf ook leerling te zijn. Hij voelde zich een gelijke van de kunstenaars met wie hij werkte.

Of de inspanningen van Ludwig echt hebben geleid tot een wedergeboorte van de kunsten, zoals in Italië ten tijde van de renaissance, valt te betwisten. Wel is het zeker dat kunst een belangrijke pijler was in het leven van Ludwig, iets wat hij wilde delen met zijn koninkrijk. Door zijn inspanningen groeide de kunstcollectie van Beieren. Bovendien steunde hij Duitse kunstenaars met financieringen en opdrachten. Ludwig werd hierbij gemotiveerd vanuit zijn persoonlijke passie voor de kunst, maar hij zorgde er ook voor dat zijn activiteiten niet onopgemerkt zouden blijven door zijn tijdsgenoten, het Duitse volk en toekomstige generaties. De werken die kunstenaars in opdracht van hem maakten, van architectuur tot schilderkunst, moesten het imago van Ludwig als patronaat en aficionado van de kunsten bevestigen. Afgezien van achterliggende motivaties blijft het een feit dat München door de inspanningen van Ludwig tot een culturele hoofdstad werd getransformeerd, waar men nog steeds geniet van de musea die hij bouwde en van de collectie die hij samenstelde.

“Zelfs “de saaiste van de massa” konden volgens Ludwig verrijkt en verlicht worden door in contact te komen met kunst.”

1 J. Sheehan, Museums in the German art world from the end of the old regime to the rise of modernism (Oxford 2000) 61.

2 J. Hagen, ‘Architecture, urban planning, and political authority in Ludwig I’s Munich’, Journal of Urban History 35:4 (2009) 459485, aldaar 461-462; D. Watkin, ‘The transformation of Munich by Maximilian I Joseph and Ludwig I’, The Court Historian 11:1 (2006) 1-14, aldaar 1.

3 Sheehan, Museums in the German art world, 59.

4 Hagen, ‘Architecture, urban planning, and political authority in Ludwig I’s Munich’, 461.

5 Sheehan, Museums in the German art world, 60.

6 Ibidem, 60-61.

7 Hagen, ‘Architecture, urban planning, and political authority in Ludwig I’s Munich’, 461-462; Sheehan, Museums in the German art world, 116.

8 Sheehan, Museums in the German art world, 63-64.

9 Ibidem, 62-63.

10 Ibidem, 61.

11 Hagen, ‘Architecture, urban planning, and political authority in Ludwig I’s Munich’, 467-477; Sheehan, Museums in the German art world, 97-98.

(I) Franz Ludwig Catel, Kronprinz Ludwig in der Spanischen Weinschänke zu Rom, 1824, olie op canvas, Bayerische Staatsge mäldesammlungen, München (inventaris nr.: WAF 142).

(II) Leo von Klenze, Glyptothek in München, ca. 1815-1834, pen en aquarel, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, München.

(III) Maker onbekend, Munich, New Pinacothek,1860-1890, fotoprint, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (reproductie nr.: LC-USZ62-109029).

(IV) Wilhelm von Kaulbach, König Ludwig I., umgeben von Künstlern und Gelehrten, steigt vom Thron, um die ihm dargebotenen Werke der Plastik und Malerei zu betrachten,1848, olie op canvas, 78,5 x 163 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, München (inventaris nr.: WAF 406).

(III) De Neue Pinakothek in München, met rondom de hele bovenste helft van het gebouw fresco’s over Ludwig I en zijn patronage voor de kunsten. Het ontwerp, gemaakt door Friedrich von Gärtner en August von Voit, is opgeleverd in 1853, maar werd gesloopt in 1949 nadat het zwaar was beschadigd tijdens WO II.

Ontwerp voor een van de negentien fresco’s die aan de buitenkant van de Neue Pinakothek gerealiseerd moesten worden. Koning Ludwig I komt van zijn troon om het werk van de kunstenaars te bekijken.

Hi again, dear readers of CODEX Historiae! Since our last update here, Merlijn’s griffin has taken wing and flown to Prague, before safely returning again on familiar soil after six days of fun and wonder. First and foremost, we were happy that the entire Merlijn board made it on time for the flight, after a hectic car ride right out of a movie scene. Prague, the city of mechanical clocks, colourful city blocks, and cheap nightlife, the decor of a lively student group that grew tighter together.

Under the professional guidance of our local guide Daniel, we were able to leave no cultural stone unturned, no dancefloor or bar unvisited, and no local dish untasted. You should try the rich brown gravies with spongy white dumplings, backed up by luscious green (!) beer. We played foosball till we dropped, watched Feyenoord drop out Slavia from the Conference League on the big screen, and relived the fall of communism in a dedicated museum – where, rumour has it, at least two board members made out with Brezhnev. Daniel also took us to the national pride that is the Czech National Museum, a beautiful neo-Renaissance cabinet of wonders, and to a village nearby, Kutna Hora – historically known for its silver riches – where long ago in a small church, art was made from the bones of Medieval plague victims. We did not just shiver from the terrible cold that day! There really is too much to say about the trip to Prague, and we hope the photos on the next page will fill in the gaps, and perhaps you will one day hear legends about our dancing.

Back at the VU a group of chess enthusiastic Merlijn members dipped their toes into the rich history and strategy of the ancient Chinese game of GO. Unfortunately, the pandemic took away our opportunity to visit the European GO Cultural Centre in Amstelveen, as it shut down last year, but, for one day, the social room was filled with black-lined wooden boards and the sounds of black and white stones dropping onto strategic positions.

“Time flies when you’re having fun”, that line seems so applicable to this last part of the year, but also to the current Merlijn board’s realisation that time is running short. Only a few more months remain to create fun activities, and our successors have already been informally chosen by now.What rests the next generation is the formalisation of their positions during the ‘ALV’, the General Members’ Meeting, at the beginning of June. By the time you read this, the new board will expectedly be preparing themselves to replace us in style.

“Why do you bother? For me, personally, it doesn’t matter if the statue is or isn’t there.” It was the summer of 2021, Rotterdam. My date, let’s call him Alex,1 and I came across the Piet Heyn statue, standing there in all its glory, at its homonymous square. Admiral Pieter Pieterszoon Heyn (1577-1629) was commander of the West Indies Company, a Dutch company that had a state-monopoly on trading and shipping around the area of America and West-Africa, predominantly trading enslaved people and sugar. Under Piet Heyn’s rule, loads of silver was stolen by the WIC from Spanish traders (in the Netherlands this is also known as the conquest of the ‘Zilvervloot’) and later invested in the slavery system.To worship this allegedly great man, his three-metre statue was put on a pedestal in 1870 in Delfsthaven, Rotterdam, the image of a national hero. He was more of an international criminal, I would say.

My date did not know it yet, but the hour that was about to follow would be a tough one.2 I raised my voice in incomprehension and disregard, frustrated that I could not find the words to make him understand how he made the situation worse with every sentence he said. “Why are people being so sensitive about it? Especially you, a white girl, why are you worrying about these things? It has nothing to do with you … He also did great things, we should not forget the prosperity he brought … It’s just a statue, no one looks at it or cares about it.”

I did not have the words then, but I do have them now. Different historical objects in our public sphere have different functions. A monument, for example, has the function to remember a historical person or event. The function of a statue is to glorify a person and his or her deeds.They are figuratively and literally put on a pedestal. In this way, statues have a different function than, let’s say, a museum. Museums display history, but statues have a positive judgement attached to them and the history they carry, glorifying the person that’s on the pedestal.Their purpose is not to show history, like a museum, but to worship that

specific history.3 A history that can be very painful and not something worth worshipping, like the statue of Piet Heyn and his involvement in slave trading.

This is, according to social anthropologist Markus Balkenhol, the reason that statues are always part of an emotional debate: because they are not factual things, they are emotional objects.4 Balkenhol explains that when we understand a statue as an object “in which secular and sacred ideas, feelings, emotions, motivations, experiences, and perceptions, intertwine, conflate and conflict, we can gain a better understanding of why people kick them, defecate on them, and destroy them, or why they feel that they need to defend them with their lives. [Statues] act like social agents in that they influence social relations.”5 Moreover, statues not only influence social relations, but are influenced by them as well; statues and social relations or memories are engaging in an ongoing dynamic and twosided relationship.

The date, Alex, complained that white girls like me don’t have anything to do with this colonial past, presumably because he assumes that neither I nor my ancestors were harmed by Piet Heyn’s deeds. For this, I want to refer to the famous author of the book White Innocence, Gloria Wekker, who calls for a larger we.6 She’s missing a feeling of common responsibility among the Dutch population. The horrors of the Colonial Past – such as slavery – are too often seen as something that ‘they’ – the descendants of the enslaved, the victims - have to deal with. The point is that this is ‘our’ history as well, a history of 400 years that built structures still affecting society as we live in today.7 And, let’s open our eyes, if ‘we’, descendants of people who profited from the colonial system, be it directly or indirectly, are the ones that find these things hard to talk about, ‘we’, the perpetrators have to come to terms with this past.

argued before, statues do not function as such.We are not erasing the memory of the (colonial) past by taking down the statues. By taking them down, we start to deal with our emotions about that past.We participate in the memory and maybe, finally, come to terms with our past. So, let me be the killjoy once again: let’s take those statues down.

1 This name is a pseudonym, the real name of Alex is known to the editors.

2 ‘Killjoy’ in the title refers to what is said here. The definition of ‘killjoy’ is: “a person who deliberately spoils the enjoyment of others.” Sara Ahmed, Writer and scholar specialised in feminist, queer and race studies, describes it as: “raising the issue of dominance and becoming more aware of power and the violence that goes with it is uncomfortable, stiff and difficult.”

Sara Ahmed, ‘Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness’, Signs 35:3 (2010) 571-594.

3 With this, I’m definitely not arguing that museums are objectively presenting history, we can talk about that some other time, the difference is in the glorifying way of presenting.

That Dutch colonialism is still not recognized among the Dutch public is shown by Alex’s statement about the ‘great deeds’ of Piet Heyn. Britta Schilling, professor of Cultural History, emphasises that we should not forget that these famous people – in her text she’s discussing Jan Pietersz. Coen and Herman von Wissmann,8 but the same can be applied to Piet Heyn – were not merely people of their time. Research shows that in their time, there were also people that saw these actions as dubious, criticising them in newspapers and pamphlets.9 It is often said that we should not judge people from the past with the morals of today. But if these actions were already criticised by the people living in that time, with the morals of that time, this argument does not hold. The question then is raised: who are we agreeing with in the past?10 The people that did not criticise them? Or the ones who did?

By arguing that no one looks at the statue anyway, Alex shows a painful fact that Schilling also exposes in her research: streets named after ‘heroic’ (read: criminal) figures and especially also statues of these figures, have become dissociated from the colonial past attached to them. A lot of people nowadays don’t know who Jan Pietersz is, who Coen or Piet Heyn were and what they did in relation to the colonial past. Schilling argues that it’s not only about forgetting, but also about concealing. People are not being educated well enough about this past; the knowledge is present, but not in our schools, museums, and other educational institutions.

As you can guess, both my date and I were not very eager to see each other again. I, because I felt that his case was a hopeless one. He, because he did not like to be yelled at on a first date and actually, I can’t blame him. I wish I could have told him this more calmly; we will not remember the past by retaining statues of colonial criminals. Because, as I and many other people have

4 Markus Balkenhol, ‘Colonial Heritage and the Sacred: Contesting the Statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen in the Netherlands.’ In: Markus Balkenhol, Ernst van den Hemel en Irene Stengs, The Secular Sacred. (London 2020) 195-216, q.v. 208.

5 Ibidem 213.

6 Gloria Wekker, ‘Never be indifferent 400 years of Dutch Colonialism, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMwgzK9LGeM, 12 februari 2022

7 More about these structures in Gloria Wekker, White Innocence Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Tennessee 2016)

8 Britta Schilling, ‘Afterlives of colonialism in the everyday.’ In: Berny Sèbe, Matthew G. Stanard (red.), Decolonising Europe. Popular Responses to the End of Empire (London 2020) 113139.

9 Ibidem.

10 Wayne Modest, Oral source in lecture 6, 18 maart 2022

Standbeeld “Piet Hein” (Oud Delfshaven) Rotterdam, 1900, postcard, collection Stadsarchief Rotterdam, https://hdl.handle.net/21.12133/0A6F9CD0DC7D474BA54C8 33F306DE2D9.

“My date did not know it yet, but the hour that was about to follow would be a tough one.”

(I) De overblijfselen van Rwandese kerkgangers.

‘After the genocide, whatever faith I had was gone. I felt abandoned by God. I could never understand why He had allowed so many innocent people to suffer such horrific fates. I asked God why many times, and heard only a hollow silence in reply. Nor could I understand how so many members of the clergy could be complicit in the genocide. I would hear stories of Catholic priests and Adventist pastors who stood by and watched as their congregations were slaughtered – or worse yet, participated in the massacres. Were these not men of God? How could I put my faith in church leaders whose hands were stained with blood? The all-loving God I had been told about as a child was lost to me.’1

– Joseph Serabenzi, voormalig president van RwandaReligie heeft een prominente rol gespeeld in veel genocides. Het geloof wordt meestal ingezet als identificerende factor, door welke groepen kunnen worden toegelaten of uitgesloten. De Holocaust, waarin Joden werden uitgeroeid om een vermeende etnische achtergrond alsmede een religieuze, is uiteraard een passend voorbeeld. Men denke ook aan de Armeense Genocide (1915-1917) waarin een voornamelijk christelijke groep werd gedood door een grotendeels islamitische, of de gruwelijkheden die zich voltrokken in Bosnië in de negentiger jaren, waar grote groepen moslims werden gedood door mensen met een christelijke achtergrond.

Rwanda vormt in dit licht een interessante casus. In 1994 brak daar een genocide uit toen de Hutu’s, een etnische groep die lang politiek en maatschappelijk achtergesteld was, op grote schaal geweld uitoefenden op de Tutsi’s, de één-na-grootste bevolkingsgroep in Rwanda, die het merendeel van de hogere strata uitmaakten. Het land had, ten tijde van de genocide, een overwegend christelijke bevolking: in een overheidsonderzoek uit 1991 geeft 59,8% van de inwoners aan christen te zijn, waarvan 62,6% rooms-katholiek, 18,8% protestant en 8,4% zevendedagsadventist.2 Er was echter geen manier om onderscheid te maken tussen Hutu’s en Tutsi’s op basis van geloof. Politicoloog Timothy Longman stelt het als volgt: ‘In contrast to genocides in other contexts, Tutsi in Rwanda were never ostracized for their religious beliefs, practices, or background nor were they isolated as infidels.’3

Echter, de kerken van Rwanda speelden een aanzienlijke rol in de genocide.Wat was de functie van de Rwandese kerken in de moordpartijen en hoe werden de gruwelijkheden gerijmd met de christelijke geloofsovertuiging? Hoe konden geestelijken, wier taak het zou moeten zijn om zich te ontfermen over de bevolking, een volkerenmoord begunstigen?

De christelijke oorsprong van Rwandees etniciteitsdenken

De kerken van Rwanda hebben zich sedert hun eerste missionarissen, aan het einde van de 19de eeuw, gemengd in etnische twisten. De christelijke strategie voor het kerstenen van de Rwandezen, begon bij het bekeren van de elite. Er bestond hoop dat het geloof zich op deze manier zou verspreiden door alle echelons van de maatschappij. Hiervoor moest echter door de kolonisatoren worden vastgesteld wie behoorde tot deze elite en wie niet. Een arbitraire grens werd getrokken, gebaseerd op het pseudowetenschappelijke racisme van de 19e eeuw, waarbij mensen werden ingedeeld als behorend tot een van de drie ‘volkeren’ van Rwanda: de Hutu’s, de Tutsi’s en de Twa. De factor waarop deze indeling berustte, was de hoeveelheid vee die een persoon bezat. Van deze drie groepen werden de Tutsi’s gezien als het verst ontwikkelde volk; zij beschikten over het meeste vee.4

De veehoudende aristocraten, die de naam ‘Tutsi’ droegen als indicator, werden schielijk tot volk gemaakt. Daarvoor was ‘Tutsi’ een woord dat iemands socio-economische status aangaf.

Dit nieuwe volk kreeg alle privileges toegediend, zoals regerings- en bestuurstaken, gesteund door het kerkelijke beeld. Zo werden, door gebruik te maken van reeds aanwezige scheidslijnen tussen groepen mensen (maar niet tussen volkeren), al bestaande categorieën gemaakt tot etnische indelingen. De racistische bevolkingsverdeling van Rwanda vond zijn oorsprong dus in de kerken, die vanaf het begin een belangrijke rol speelden in het bevorderen van de etnische kijk op Rwanda’s bevolking.

In genocides wordt vaak positieve taal ingezet door de dadergroep: een probleem wordt opgelost, een plaag wordt verholpen, ongedierte wordt uitgeroeid om zo de natie te zuiveren. Dit valt ook terug te zien in Rwanda: de naam van de Interahamwe, de voornaamste extremistische Hutu-militie gedurende de slachtpartijen, betekent letterlijk ‘zij die samen vechten’.5 Het taalgebruik maskeert het feit dat de moorden voortkomen uit ideologische motieven, door een façade van rechtvaardigheid op te stellen, inspelend op culturele en sociale motieven.

Het taalgebruik van christelijke autoriteiten voorafgaand aan en tijdens deze genocide nam eenzelfde karakter aan. In boodschappen aan de bevolking onder de auspiciën van het Rwandese katholieke bestuur kwam de nadruk steeds minder op religieuze thematiek te liggen naarmate de jaren vorderden; steeds vaker werd de staat en diens leider benadrukt.6 Ook de schrijvers van het beruchte Manifeste des Bahutu, dat al in 1957 aanspoorde tot etnische spanningen, genoten de steun van de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk; Hutu-suprematie en religie gingen hand in hand.7

Door de nauwe band tussen kerk en staat werd het idee de wereld in geholpen dat de genocide, die vanuit de staat georga-

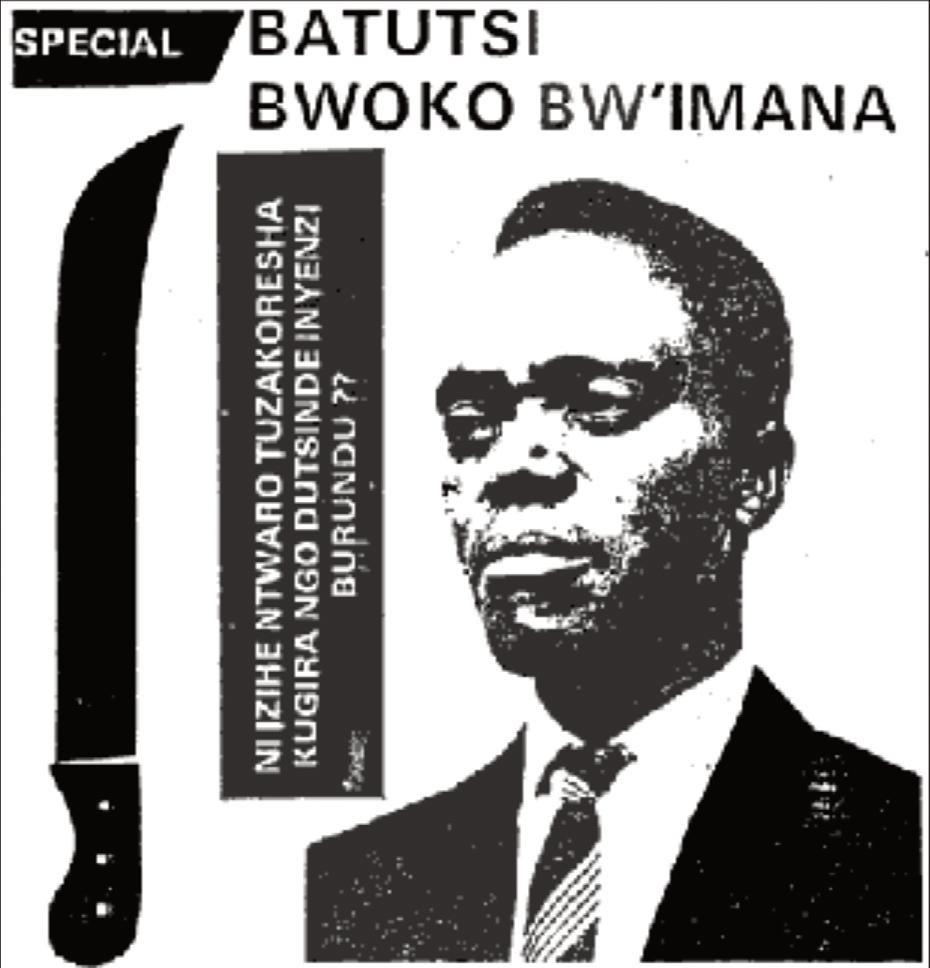

(II) Propaganda uit het Rwandese tijdschrift Kangura. Het bijschrift leest: ‘Welk wapen zullen we gebruiken om de Tutsi-kakkerlakken te verslaan?’ Ernaast staat een machete afgebeeld.

niseerd was, goedgekeurd werd door de kerken; veel daders namen zelfs deel aan de mis alvorens het moorden.8 Historicus Olov Simonsson spreekt van het construeren van een aparte ‘Hutu-God’ met een tweeledig karakter: een vredelievende god wanneer de Tutsi’s als gewelddadig moesten worden afgeschilderd, een oorlogsgod wanneer de massamoord op de Tutsi’s verantwoord moest worden.9 In dat laatste valt het heiligende karakter van genocides opnieuw te zien: het is een benodigd iets, een gevecht waarin er maar één overwinnaar kan zijn.

De kerken waren niet de organisatoren van de massamoorden, maar maakten het wel begrijpelijk voor de Hutu-bevolking.10 Christelijke autoriteiten spoorden de bevolking aan om de staat te volgen en te gehoorzamen, en stoomden zodoende, direct of indirect, diezelfde bevolking klaar voor de genocide.11 In de woorden van de reeds aangehaalde Longman: ‘Christianity in Rwanda remained predominantly a legalistic religion that emphasized authority and obedience and continued to practice political maneuvering and discrimination.’12

In dit proces werd nooit direct taalgebruik benut. Vanuit de Rwandese kerken is, zoals bij meer genocides het geval is,13 geen directe boodschap te vinden waarin wordt aangespoord tot het plegen van genocide.14 Genocides worden altijd gerechtvaardigd op de reeds beschreven, ambigue manier. Ze worden neergezet als een vereiste, dan wel voor de gezondheid van de natie, dan wel voor het imminente gevaar dat een bepaalde groep vormt.

Indirecte en directe deelname

Het verspreiden van genocidaire propaganda is slechts één aspect van de indirecte deelname in de genocide van de kerken. Een ander aspect is het gebrek aan actie, de afwezigheid van pogingen om de genocide te doen ophouden.

Door de kerstening van Rwanda in de loop van de 19de en 20ste eeuw verwierven de kerken veel macht. Missionarissen poogden de bevolking op materiële wijze te bekeren, bijvoorbeeld door het opzetten van scholen, ziekenhuizen, silo’s, etc., opdat de plaatselijke inwoners zich bij het christendom zouden voegen. Op deze manier verkregen de kerken al vroeg in Rwanda’s koloniale geschiedenis aanzienlijke macht en vormden ze een grote

“Veel dominees en priesters waren de oprichters van milities die werden ingezet in de genocide...”

speler in de nationale politiek.15 De invloed van de kerken had ingezet kunnen worden om de genocide in te perken, maar werd voornamelijk gebruikt om de volkerenmoord te ondersteunen. De schuld van de geestelijken begon niet bij het participeren in de genocide, maar al eerder, bij het weigeren om hun autoriteit over het volk en hun invloed in de staatspolitiek te utiliseren om de etnische conflicten te stoppen.

Het bleef echter niet bij onwil vanuit de kerkelijke autoriteiten. Geestelijken hielpen op lokaal en regionaal niveau met het mobiliseren en bewerkstelligen van geweld tegen Tutsi’s c.q. deden direct mee in het geweld.16 Veel dominees en priesters waren de oprichters van milities die werden ingezet in de genocide,17 en kerken vormden een plek waar een opmerkelijk deel van de slachtoffers vielen.18

Niet alleen de paus, maar ook geestelijken in Rwanda protesteerden tegen de genocide, hetzij vanuit religieuze, hetzij vanuit humanitaire overtuigingen. Al op de eerste dag van de genocide verzette Augustin Nkezabera, de Hutu-priester van de Muramba-parochie, zich door Tutsi’s te waarborgen in zijn kerk, waarvoor hij werd vermoord.24 Door het doden van gematigde Hutu’s als Nkezabera werd er verder een wig gedreven tussen de twee bevolkingsgroepen.

Volgelingen van de pinksterbeweging boden bijzonder veel weerstand tegen de genocide en hielpen Tutsi’s vaker dan andersgelovigen,25 maar uiteindelijk zouden geestelijken uit alle stromingen protesteren.26 Zo schreef bisschop Thaddée Nsengiyumva, die uiteindelijk vermoord zou worden tijdens de genocide, met het oog op de passieve houding van de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk aangaande de etnische conflicten in Rwanda in 1992 al: ‘De Kerk is ziek.’27 Ook de kardinaal Roger Etchegaray riep in 1994 op om de oorlog te stoppen.28

Een andere manier waarop de kerken deelnamen aan de genocide was het goedpraten ervan. Een grote rol hierin werd gespeeld door paus Johannes Paulus II, die het pontificaat van 1978 tot 2005 bekleedde en een tegenstrijdige positie innam ten opzichte van de gruwelijkheden in Rwanda. Hij zei dat de Kerk geen verantwoordelijkheid kon nemen voor geestelijken die medeplichtig waren aan de genocide.19 Ook na de gruwelijkheden bleef het Vaticaan onwillig om verantwoordelijkheid te nemen. Twee nonnen die in 2001 berecht werden vanwege hun misdaden tijdens de genocide, genoten de steun van de Kerk.20 Op deze manier maakte de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk onder leiding van Johannes Paulus II zich schuldig aan het begunstigen van het ontkenning proces.

Het zou echter onjuist zijn om de paus louter af te schilderen als boosdoener. Op 10 april 1994, luttele dagen na het ontluiken van de massamoorden, pleitte Johannes Paulus II tijdens de homilie voor het beëindigen van wat hij ‘fratriciden’ noemde, en op 3 mei 1994 was hij de eerste persoon in een machtspositie die de term ‘genocide’ gebruikte om de moordpartijen in Rwanda te omschrijven, nog voor de Verenigde Naties dat deden.21 Op 15 mei zou hij nogmaals vaststellen dat het om genocide ging en betreuren dat katholieken hierin een rol speelden.22 Het is derhalve onjuist om te stellen dat de paus de katholieke ondersteuning van de genocide ontkende. Bovendien zou Johannes Paulus II door de jaren heen nog vaker oproepen tot het stopzetten van de genocide.23

Al met al heeft het christendom een aanzienlijke rol gespeeld in de Rwandese Genocide. De kerken fungeerden niet alleen als tussenpersoon om de boodschappen van de staat over te brengen op de bevolking, maar delen ook de schuld door de onwil om hun macht te gebruiken om de genocide te belemmeren, waarbij ze ook hun rol in de genocide ontkennen. Echter hebben de kerken en hun personeel, in het bijzonder de paus, geholpen bij het erkennen van de massamoorden als een genocide. Het zou kortzichtig zijn om te stellen dat de kerken eenzijdig aan de kant van de daders stonden.

“Niet alleen de paus, maar ook geestelijken in Rwanda protesteerden tegen de genocide...”

1 Joseph Sebarenzi, God Sleeps in Rwanda: A Personal Journey of Transformation (Londen 2010) 88.

2 Carol Rittner, John K. Roth en Wendy Whitworth eds., Genocide in Rwanda: Complicity of the Churches? (Saint Paul, 2004) 89.

3 Timothy Longman, ‘Church Politics and the Genocide in Rwanda’, Journal of Religion in Africa 31:2 (2001) 163-186, aldaar 165.

4 Ibidem, 168-169.

5 Jean-Pierre Karegeye, ‘Religion, Politics, and Genocide in Rwanda’ in: Andrea Bieler, Christian Bingel en Hans-Martin Gutmann eds., After Violence: Religion, Trauma and Reconciliation (Leipzig 2011) 82-102, aldaar 85.

6 Ibidem, 83-87.

7 Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 6.

8 Longman, ‘Church Politics’, 166-167, 180.

9 Olov Simonsson, God Rests in Rwanda: The Role of Religion in the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda (Uppsala 2019) 192.

10 Longman, ‘Church Politics’, 166, 176.

11 Timothy Longman, Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda (Cambridge 2009) 196.

12 Longman, ‘Church Politics’, 182.

13 Men kan hierbij denken aan de Holocaust, waarvoor ook geen direct bevel te vinden is dat kan worden toegeschreven aan Hitler.

14 Longman, Christianity and Genocide, 196-197.

15 Longman, ‘Church Politics’, 167, 170, 172-174.

16 Ibidem, 180.

17 Longman, Christianity and Genocide, 185.

18 Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 12.

19 Karegeye, ‘Religion, Politics, and Genocide’, 98; Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 16-17.

20 Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 19.

21 Ibidem, 13.

22 Karegeye, ‘Religion, Politics, and Genocide’, 98; Simonsson, God Rests in Rwanda, 185.

23 Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 12-15.

24 Longman, Christianity and Genocide, 195.

25 Ibidem, 195-196.

26 Longman, ‘Church Politics’, 180.

27 Rittner e.a., Genocide in Rwanda, 9. Mijn vertaling.

28 Ibidem, 14.

(I) Foto door een onbekende fotograaf. Eigendom van dw.com.

(II) Omslag van de uitgave van Kangura uit december 1993. Toegestaan gebruik volgens de richtlijnen.

(III) Foto van Johannes Paulus II door een onbekende fotograaf, 21 mei 1984. Eigendom van Quirilane.it.

Aristoteles’ dood in 322 v.Chr. in het Griekse Chalkis, kwam hij als revolutionair filosoof uiteraard in de hemel, waar zijn misogyne ideeën werden vergeten. Naarmate de eeuwen voorbij gingen, verschenen er steeds modernere mensen in de hemel. De nieuwste technologische ontwikkelingen waar deze omhoog gestegen zielen over spraken gaven Aristoteles genoeg nieuwe filosofische problemen om zijn visie op los te laten. Zijn nieuwsgierigheid werd helemaal opgewekt toen hij hoorde dat iemand zelfs een vriendschap kon behouden met deze nieuwe technologie.Terwijl hij zelf deze technologie genaamd ‘Snapchat’ gebruikte, behield hij zijn gewoonlijke onderzoekende en vragende manier van filosoferen en begon met mij te praten:

Voor altijd Snapvrienden?

Wat is de waarde van vriendschappen op Snapchat gezien vanuit het perspectief van Aristoteles? Eerst even kort over Snapchat zelf: op deze applicatie van het bedrijf Snap Inc. delen gebruikers berichten van hun dagelijks leven, bekend als ‘Snaps’. Deze Snaps bestaan uit foto’s of video’s, die mensen sturen en ontvangen. Het nut van sociale media, waar Snapchat deel van uitmaakt, is het efficiënter maken van netwerken, adverteren en communiceren.1 We kunnen ‘vrienden’ worden met mensen die op geheel andere continenten wonen. Wat de applicatie onderscheidt van andere apps zoals WhatsApp, is de directe en tijdelijke natuur van de berichten. De meeste berichten kan je maar één keer zien voordat ze verdwijnen. Zoals het bedrijf stelt op zijn website: ‘We contribute to human progress by empowering people to express themselves, live in the moment, learn about the world and have fun together.’2 Het doel van de app is dus om mensen te laten leven in het moment door ze aan te moedigen om foto’s te maken van de mooie momenten in hun dagelijkse activiteiten. De meeste mensen onderhouden een vriendschap op Snapchat door foto’s, video’s of chatberichten te sturen van wat ze dagelijks meemaken. Snapchat maakt daardoor de nabijheid van vriendschap overbodig. De fysieke afstand van Snapchat zou vriendschap niet moeten belemmeren. Snapchat overbrugt immers deze afstand via digitale communicatie. Echter, in hoeverre is echte vriendschap mogelijk op een online platform zoals Snapchat?

Het is hier belangrijk om een onderscheid te maken tussen de verschillende manieren waarop online vriendschappen tot stand komen. Er zijn drie mogelijkheden voor het ontstaan van online vriendschappen: goede vriendschappen in het echt die we verder online in stand houden, vrienden die elkaar online ontmoet hebben en later elkaar in het echt ontmoeten, en vriendschappen die online blijven.3 Het is de vraag hoe Snapchat bijdraagt aan deze drie manieren waarop online vriendschappen ontstaan.

Vrienden delen voor het leven Aristoteles betoogt in de Ethica Nicomachea dat elk mens in zijn leven streeft naar geluk. Gelukkig zijn is niet alleen een gemoedstoestand, maar ook iets wat we leven. We kunnen het goede leven bereiken door te focussen op deugdzaamheid. Opmerkelijk is dat hij in dit werk niet alleen schrijft over het goede leven van de individuele mens, maar ook over vriendschap. ‘Want zonder vrienden zou niemand ervoor kiezen om te leven.’4 Vriendschap is onderdeel van het goede leven: de gelukkige mens heeft vrienden nodig. Aangezien Aristoteles de mens definieert als politiek dier, heeft de mens dus van nature mensen nodig om gelukkig te worden.5

kunnen onderhevig zijn aan verandering: vrienden vormen elkaar door de tijd heen en beïnvloeden elkaars waarden en keuzes. Bovendien is vriendschap een fenomeen dat voortbouwt op eerdere ervaringen.10 We verkrijgen een oprechte vriendschap door middel van een gedeelde geschiedenis, die ervoor zorgt dat we elkaar beter begrijpen. Als je begrip hebt van het verleden, heb je immers een betere kijk op het heden en de toekomst.

Anders dan de eerdergenoemde manieren waarop vriendschappen ontstaan, onderscheidt Aristoteles drie soorten vriendschappen: een vriendschap uit genot, nut of deugd.6 Het ging Aristoteles er met dit onderscheid vooral om met welke reden we een vriendschap aangaan. Vriendschappen uit genot ontstaan wanneer mensen afhankelijk zijn van elkaars plezierige kwaliteiten. Denk aan uitgaansvrienden of vrienden van de sportclub: je doet vooral leuke dingen met elkaar. Vriendschappen uit nut komen voort uit gemak of handigheid. We worden vrienden met medestudenten, collega’s of de kapper, omdat we ze later nodig hebben. De eerste twee vriendschappen zijn volgens Aristoteles accidenteel: ze ontstaan toevallig door tijdelijke behoeftes en houden op de lange termijn geen stand. Vriendschap uit deugd noemt Aristoteles ook wel perfecte vriendschap, omdat het langer standhoudt. Bij de laatste soort vriendschap zijn mensen niet gebonden door noodzaak of handigheid, maar door wederzijds respect en deugd. Bij perfecte vriendschap is deugdzaamheid noodzakelijk: alleen goede mensen kunnen goede vrienden zijn voor het belang van de ander. Dit soort vriendschappen zijn zeldzaam en duren lang om te ontwikkelen.7 Wanneer twee vrienden dezelfde deugden nastreven, zal hun vriendschap voortbestaan. Deugdzame vrienden zijn daarom niet alleen belangrijk, maar essentieel voor een gelukkig leven.8

Daarnaast beschrijft Aristoteles vijf kenmerken van een perfecte vriendschap.Ten eerste is een vriend iemand die het goede doet en het goede wenst voor het belang van zijn vriend.Ten tweede wenst hij dat zijn vriend leeft en bestaat. Ten derde spendeert hij tijd met zijn vriend. Ten vierde maakt hij dezelfde keuzes als zijn vriend. En ten slotte is een vriend iemand die van hetzelfde geniet of om hetzelfde treurt als zijn vriend.9 Deze gelijkenissen bepalen niet de vriendschap als noodzakelijke conditie, maar

Op het eerste gezicht lijkt Snapchat vooral bedoeld voor het onderhouden van vriendschappen uit genot. Gebruikers onderhouden langdurige vriendschappen door het sturen en bewerken van foto’s of video’s. Snapchat gaat vooral om plezier maken: grappige foto’s of lollige tekeningetjes doorsturen naar je vrienden voor tijdelijk vermaak. We kunnen via deze app alleen vriendschappen op basis van genot behouden. Echter, het vervullen van een goede vriendschap kan volgens Aristoteles alleen door met een vriend je leven te delen.11 De gelukkige mens deelt zijn proces van deliberatie. ‘Hij moet, daarom, het bestaan van zijn vriend samen met die van hemzelf waarnemen.’12 Samenleven met een vriend betekent het delen van activiteiten, gedachten en bovenal discussies. Aristoteles laat ons dus zien dat vriendschap het fundament is van elke samenleving en dat het groeien en verbreken van vriendschappen hoort bij wat het is om mens te zijn. Zoals Aristoteles stelt: ‘Afstand verbreekt de vriendschap niet absoluut, maar alleen de activiteit ervan.’13 De fysieke afstand van Snapchat zou vriendschap dus niet moeten belemmeren. Snapchat verwisselt deze afstand door digitale communicatie, waardoor het niet voldoet aan een vervanging van deze fysieke activiteit.

Voldoet Snapchat dan aan Aristoteles’ definitie van een perfecte vriendschap? Bij Snapchat komen de vijf kenmerken impliciet terug. Een vriend op Snapchat wenst het goede voor zijn vriend door hem foto’s te sturen van leuke dingen. Of een vriend daarmee ook wenst dat de ander leeft en bestaat, blijkt impliciet uit het versturen en ontvangen van Snaps.Vrienden spenderen tijd met elkaar door deze Snaps te delen en erover te chatten. Daarnaast kunnen vrienden dezelfde keuzes delen via Snaps, bijvoorbeeld het kiezen van hetzelfde eten of het doen van dezelfde activiteiten. En ten slotte kunnen vrienden positief of negatief reageren op gestuurde foto’s.

Toch heeft goede vriendschap volgens Aristoteles een geschiedenis van gedeelde ervaringen nodig, iets wat bij Snapchat

“We worden vrienden met medestudenten, collega’s of de kapper, omdat we ze later nodig hebben.”

“Goede vriendschap heeft volgens Aristoteles een geschiedenis van gedeelde ervaringen nodig, iets wat bij Snapchat ontbreekt.”

ontbreekt. Vrienden op Snapchat brengen hun tijd door het sturen van chatberichten, video’s en stickers. Een voordeel is dat je altijd kunt communiceren met je vrienden, een nadeel is dat je tijdens het communiceren niet fysiek bij elkaar bent. Snapchat houdt een lijst van ‘Best Friends’ bij, afhankelijk van hoe vaak je met je vrienden praat. Degenen met wie je het meeste praat en naar wie je de meeste Snaps verstuurt, zijn dan je beste vrienden. Echter, vriendschap valt niet te kwantificeren op basis van interacties. Aristoteles zou zeggen dat het gaat om de kwaliteiten van een ander, niet om het aantal ontmoetingen.14 Als een gedeelde geschiedenis noodzakelijk is voor een oprechte vriendschap, dan is een sociale media vriendschap op basis van een gebrek van gedeelde ervaring gedoemd om te falen.15

Een tegenargument zou kunnen zijn dat je via Snapchat wel degelijk activiteiten kan delen met vrienden, deze activiteiten zijn alleen van een andere soort.Vrienden houden elkaar op de hoogte van elkaars leven, niet alleen via berichten, maar vaak met levendig beeldmateriaal van wat de ander aan het doen is. Net als er vrienden zijn die samen drinken, gamen en discussiëren, zijn er ook vrienden die elkaar Snaps versturen. Het sturen van Snaps is een activiteit die een gedeelde geschiedenis opbouwt. Als vrienden activiteiten op Snapchat kunnen delen, kunnen ze toch ook een goede vriendschap onderhouden en gelukkig zijn? Ik zou hier willen beweren dat het versturen van Snaps of chatberichten niet genoeg is om een goede vriendschap te onderhouden. Je kan inderdaad discussiëren en elkaar uitdagen via chatberichten, maar daar is de app niet voor bedoeld. Snap Inc. stelt zelf dat het doel van Snapchat het delen van dagelijkse momenten is. Bovendien is er een verschil tussen activiteiten delen en samen meemaken met vrienden. Constant een ander op de hoogte houden van de activiteiten die je doet is handig, maar je deelt deze activiteiten niet gezamenlijk, je ‘deelt’ ze slechts digitaal. Activiteiten delen betekent niet per se samenzijn.

hoogte blijven. Een goede vriendschap bestaat volgens Aristoteles namelijk uit het verbeteren en uitdagen van elkaar, om ervoor te zorgen dat beide vrienden een beter persoon worden, iets wat bij Snapchat lastig is om te doen.We kunnen onze Snaps zien als extra middel voor plezier in een goede vriendschap, niet als een manier om de ander deugdzamer te maken. Echter, we moeten erkennen dat deze vriendschappen vaker gebouwd zijn op plezier, in plaats van onvoorwaardelijk voor elkaar klaar staan.

Het is dus moeilijk om alleen op Snapchat een goede vriendschap te vormen. We kunnen het wel gebruiken om een goede vriendschap te onderhouden wanneer we onze vrienden voor een lange tijd niet zien. Echter, op de lange termijn zorgt Snapchat niet voor goede vriendschappen.

1 O.O. Badejo & N. Okorie, ‘Ethical implications of friendship based on anonymity: The social media example’, Philosophia: EJournal for Philosophy & Culture 27 (2021) 51-72, aldaar 57.

2 Snap Inc., ‘Snap Inc.’, https://www.snap.com/en-GB (geraadpleegd op 10 juni 2022).

3 Badejo & Okorie, ‘Ethical implications’, 57.

4 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, W.D. Ross & L. Brown (red.), (Oxford; Herziene editie 2009) 1155a 5-6.

5 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1169b 18-22.

6 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1156a 11-13, 1156b 7-8.

7 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1156b 32-33.

8 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1170b 18-19.

9 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1166a 3-9.

10 Badejo & Okorie, ‘Ethical implications’, 62.

11 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1172a 7-8.

12 Aristoteles, The Nicomachean Ethics, 1170b 9-10.