CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE MAR/APR 2024 CANADIANAVIATOR.COM DISPLAY UNTIL APRIL 30 QUICK SUBSCRIBE! PM42583014 R10939 $7.95 DEW Line Duty THE COLOURFUL CHARACTERS INVOLVED RCAF’s Last Buffalo NOW PRESERVED AT OTTAWA MUSEUM North to Alaska FLYING AMONG SPECTACULAR GLACIERS TEAM CANADA A Look Inside the World Advanced Aerobatic Championship in Nevada AT THE WAAC

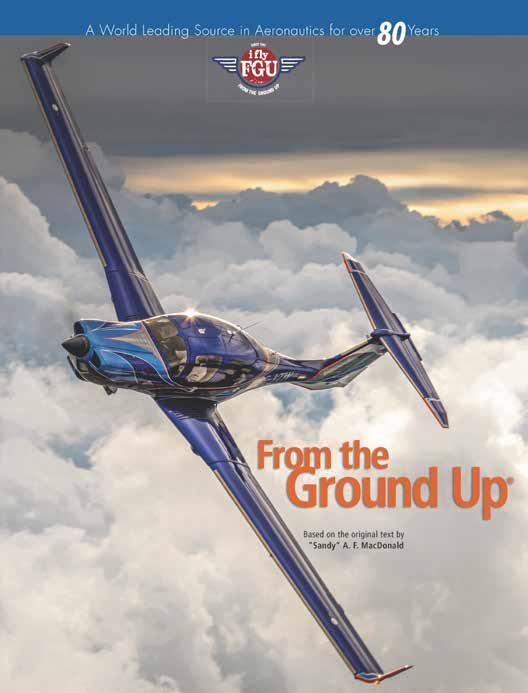

FROM THE GROUND UP, 30th Edition

PrivatePilot Magazine

if you are going to buy a flight manual and only want to have one around the house, this is the one.”

“There is a smoothness and ease-of-reading that make this book a pleasure to read… everyone out there should read the engine section, which is excellent and covers timing, carburetors, magnetos, solid-state ignitions and even a procedure for a backfire during starting…

For over 80 years, the content of From the Ground Up has stood as a literary benchmark that defines the multitude of theories associated to aeronautics. It describes the practices necessary to achieve the highest levels of distinction as safe, competent and skilled life-long aviators.

Flyer Magazine

“[From the Ground Up] offers a wide range of advice and information, technique and instruction, on practically every aspect of flying –in a single volume… The level of detail and its easy-going writing are way ahead of some of the text books we’re used to, especially when it comes to radio navigation and aircraft technical explanations… I found From the Ground Up so useful that it’s becoming part of my deskside library.”

“For 50 years the book From the Ground Up has been published and is one of the most comprehensive volumes on the subject of flying and learning to fly… it can be read right through, from cover to cover, or can be dipped into for information on specific subjects. Some aviation books cannot comfortably be used in this dual role.” International Flight Training News

Through its evolving editions, many generations of readers have used this award-winning title as the foundation of their introduction to the concepts that require thorough understanding in advance of the sought-after hours of flying enjoyment that are the ultimate goal of all who seek to earn their wings and expand their knowledge of flight theory and practice.

The content of From the Ground Up may, at times, seem complex, but the pathway to learning the fundamentals of aeronautics is one that reaps much in the way of personal reward for all who pursue the goal of thoroughly understanding the subject. Indeed, it was by design that its original author, “Sandy” A. F. MacDonald — a man recognized as a “father” of what still stands today as the standard curriculum for ground school instruction — devised this aeronautical textbook to be comprehensive and current while conveying its material in such a way as to enhance the reader’s understanding of every written word.

Aviation Publishers Co. Ltd.

ISBNwww.aviationpublishers.com 978-0-9730036-3-5

9780973003635

From the Ground Up ®

Not one to permit his vast experience to allow for foregone conclusions, “Sandy” MacDonald’s meticulous care in the creation of From the Ground Up has become the hallmark for its widespread use and respect as the reference manual of choice in hundreds of flying schools throughout Canada and around the world.

Its latest edition is the 30th Edition. A French-language version is also available under the title Entre Ciel et Terre Totalling over 400 pages of in-depth content formatted in a sequential, logical and easy-to-read fashion, the publication boasts over 360 graphics, charts, diagrams, illustrations and photos. An additional full-colour navigation chart and a sample weather chart are included.

All chapters are current in the latest technological and legislative aeronautical matters and cover such topics as The Airplane, Theory of Flight, Aero Engines, Aeronautical Rules & Procedures, Aviation Weather, Navigation, Radio & Radio Navigation, Airmanship, Human Factors, and Air Safety From the Ground Up also includes an extensive index, glossary and a 200-question practice examination.

Since the 1940’s, virtually every student — civilian, military, commercial, recreational — who has ever learned to fly in Canada has used From the Ground Up as the primary ground school textbook from which they’ve learned everything one can learn about aeronautics, and about flying. Referred to as “the bible” of ground school instruction, and updated with every frequent re-print, From the Ground Up has long been considered an essential resource for all with any interest whatsoever in the theory of flight, and in the practice of aviating.

For more information about this title, visit us on the web where you can obtain details on how to acquire this, and all of our other aeronautical publications.

Published by Aviation Publishers Co. Ltd.

A World Leading Source in Aeronautics for 80 Years

AVIATION PUBLISHERS CO. LIMITED Box 1361, Station B, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1P 5R4 www.aviationpublishers.com

aviationpublishers.com

A v a ilable from

IN THIS ISSUE

DEPARTMENTS

5 / WALKAROUND

For the thrill of it

6 / WAYPOINTS

Aviation news

By Aviator Staff

7 / GEAR & GADGETS

Four aviation products

By Aviator Staff

8 / AIRMAIL

Up for adoption

By Aviator Staff

8 / FLYING STORIES

The Island’s Islander

By Jack Schofield

10 / THE PLANE FIXER

It’s becoming a woman’s world, too

By Liana Buessecker

12 / TALES FROM THE LAKEVIEW

Douglas’s workhouse

By Robert S. Grant

14 / EXPERT PILOT

Ferrying can be complicated

By Richard Pittet

16 / UNUSUAL ATTITUDES

On coaching Team Canada

By Aaron McCartan

18 / A PILOT’S LIFE

DEW line talk

By Chris Weicht

20 / INSTRUMENTAL FACTS

Displayed vertical paths explained

By Ed McDonald

22 / VECTORS

Do you really want to cancel IFR?

By Michael Oxner

24 / DOWN EAST

Searching eastern shores

By Don Ledger

26 / RIGHT SEAT

Off-airport landings

By Mireille Goyer

27 / PEP TALK

A briefing on pre-flight briefings

By Graeme Peppler

28 / ON THE ROCK

The disappearing Swede

By Gary Hebbard

30 / COLE’S NOTES

Get ‘er done!

By W.T. (Tim) Cole

50 / BOOKSHELF

Top aviation titles

52 / SERVICE CENTRE

Deals and offers

54 / FLIGHT BAG

Puzzle and questions

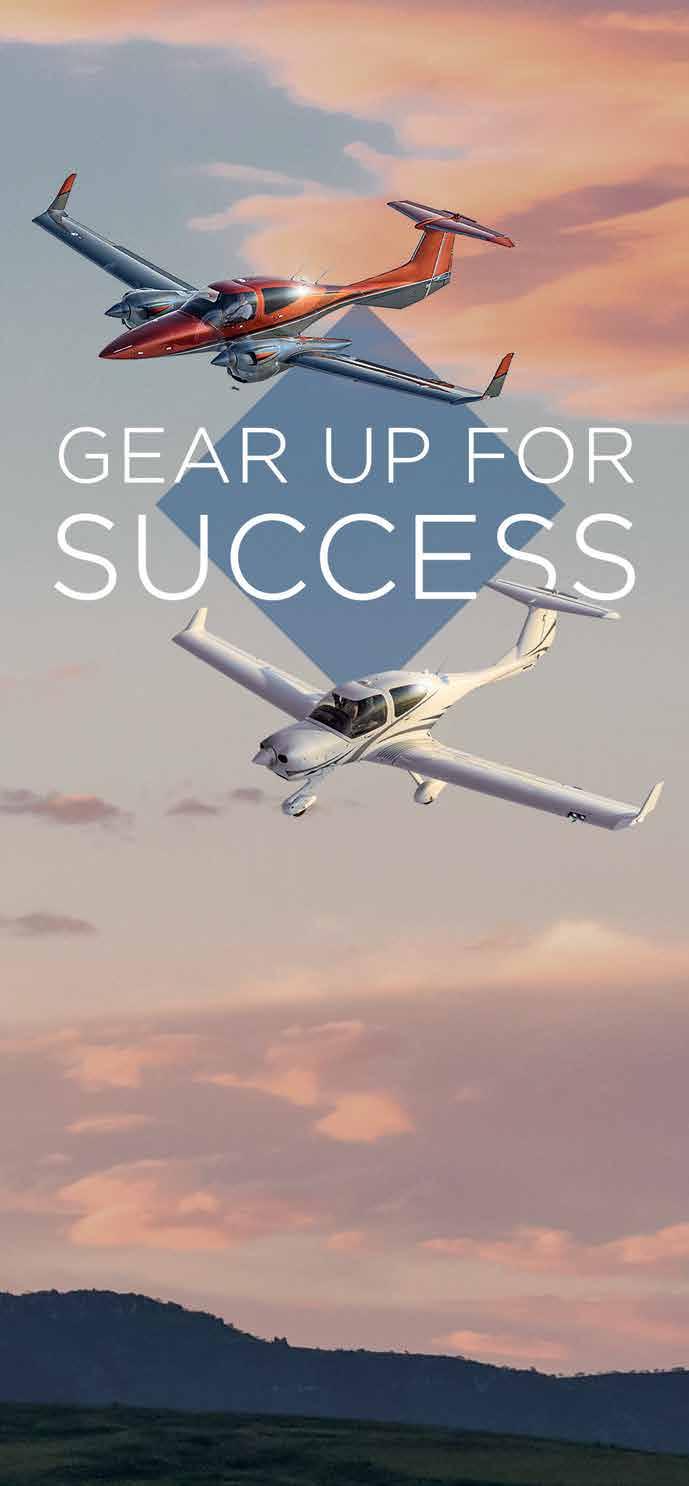

ON THE COVER

The skies over Nevada were filled with several red and white aerobatic competitors from Canada.

FEATURES

32 Competing with the Best

Team Canada captain Luke Penner provides us with the exciting details of the team’s performance at the 2023 World Advanced Aerobatic Championship in Nevada.

By Luke Penner

40 North to Alaska

A pair of taildragger pilots tour the spectacular glaciers and scenic backcountry airstrips of northwestern British Columbia and southeastern Alaska.

By Curtis Penner

46 De Havilland’s Venerable Buffalo

Ottawa’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum invited Canadian Aviator to the unveiling of the last RCAF Buffalo, now on display. Our contributing editor takes us behind the scenes.

By Robert S. Grant

MAR/APR 2024 VOLUME 34 NUMBER 2

Photo by Spencer Davis

RICK HIEBERT CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 3

LUKE PENNER

publisher + editor Steve Drinkwater steve@canadianaviator.com 604.999.2411 contributing editor Robert S. Grant graphic designer Janice Hildybrant advertising sales account manager Katherine Kjaer katherine@canadianaviator.com 250.592.5331 director of consumer marketing Craig Sweetman ADMINISTRATION group controller Anthea Williams awilliams@opmediagroup.ca Office 604.428.0261 subscriptions Marissa Miller marissa@opmediagroup.ca 1.800.656.7598 Canadian Aviator is published six times a year: Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/Jun, Jul/Aug, Sep/Oct, Nov/Dec Canadian Aviator Publishing Ltd. 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 3Z3 Phone: 604.999.2411 canadianaviator.com Printed in Canada. Agreement No. 42583014. Postage paid at Vancouver, B.C. Contents copyright 2024 by Canadian Aviator Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. ISSN 1492-0255. Return undeliverable Canadian mail to Circulation Department. 802-1166 Alberni St., Vancouver B.C. V6E 3Z3. From time to time we make our subscribers’ names available to reputable companies whose products or services we feel may be of interest to you. To be excluded from these mailings, just send us your mailing label with a request to delete your name. Publications Mail Registration No. 10939. 50% SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1.800.656.7598 CanadianAviatorMedia @canadianaviatormag canadianaviator.com subscription inquiries admin@canadianaviator.com subscription rates 1 year (6 issues) $26.00 (Taxes vary by province); Outside Canada: $32.00 per year editorial submissions Editorial contributions should be sent to the editor by email in plain text with high-resolution photos attached: steve@canadianaviator.com MONARCH PREMIUM CAPS Premium Stainless Steel Umbrella Caps for yourCessna177 through210 www.hartwigfuelcell.com info@hartwig-fuelcell.com US: 1-800-843-8033 CDN: 1-800-665-0236 INTL: 1-204-668-3234 FAX: 1-204-339-3351 NEW TANKS - 10 YEAR WARRANTY Keeping aircraft in the air since 1952 SPECIALIZING IN BEAVER & OTTER FUEL CELLS QUOTES ON: Cherokee Tanks Fuel Cells & Metal Tanks Repair, overhauled & new Technical Information or Free Fuel Grade Decals Keeping aircraft in the ROTECH MOTOR LTD. 1-(236)-600-0137 SALES@ROTECHMOTOR.CA ROTECHMOTOR.CA AUTHORISED ROTAX DISTRIBUTOR XPS AVIATION ENGINE OIL Formulated specifically for Rotax aircraft engines. FORMULATED FOR THOSE WHO CARE. 4 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

The Pursuit of the Thrill of Flying

Most if not all of us remember the thrills we got in the early days of flying. Some of us renew that thrill every so often by taking on a new challenge, such as a float rating, night rating or obtaining a tailwheel endorsement and flying to backcountry airstrips. Some decide to point the nose of their aircraft west and tackle the Rocky Mountains and beyond.

Yet for some of us that is still not enough. The cover story of our Nov/Dec, 2023 issue featured two Canadian teams that competed in the 2023 Reno Air Races — the last competition to be held at that venue, by the way. Edmonton’s Outlaw Racing Team and Calgary’s Atomic Pumpkin

flew the Canadian flag at Reno-Stead airport. Racing may have come to an end in Reno, but it will continue elsewhere, and we hope both Alberta teams, and perhaps others from Canada, will be there.

And for others yet, for whom air

racing is not quite the thrill they were looking for, decide to tackle aerobatic flying instead. Our own Luke Penner, who writes about aerobatic flying in his regular column Unusual Attitudes, penned this issue’s cover feature of the 2023 World Advanced Aerobatic Championship in Nevada. Penner, as Team Canada’s captain, is also an aerobatics instructor at Manitoba’s Harv’s Air Inverted where he has trained some of the team’s members.

All of these competitors are living the dream many of us had, or for some, still have. The rest of us will have to be content with watching them from the ringside. Or reading about them.

WALKAROUND EDITORIAL

ONE STOP SHOPPING • LOWEST PRICES • SAME DAY SHIPMENT ORDER YOUR FREE 2023-2024 CATALOG!

BY STEVE DRINKWATER

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 5

KENN SMITH

WAYPOINTS

The Next Step in Powered Flight

SEALAND OF B.C. LEAPS TO A NEW ERA IN FLIGHT TRAINING

Soon to grace the skies over central Vancouver Island will be an aircraft designed in Slovenia and built across its border with Italy — a batteryfuelled, electrically powered Pipistrel Velis Electro. By the time you read this, Sealand Flight of Campbell River should have received this newest addition to their training fleet.

Pipistrel, acquired by Textron Aviation in 2022, began developing electric airplanes in 2007 with the Taurus Electro.

Seventeen years later, the Velis Electro is now type certified for Day VFR pilot training in over 30 counties.

The Velis Electro has a maximum cruise speed of 98 knots, a maximum altitude of 12,000 feet and has a useful load of 378 pounds. Its endurance is estimated at 50 minutes plus reserve. These parameters, significantly less than traditional training aircraft powered by internal combustion engines (ICE), are more suitable for training duties within an airport environment or close by.

dual liquidcooled lithiumion batteries that are not designed to be easily removed but are quickly recharged.

may work out to be a savvy investment for flight schools.

“With the industry moving towards electric-powered aircraft, there will be a need for pilots trained in that environment,” Sealand’s general manager Nancy Marshall told us. “Harbour Air is an example,” she added.

Canadian Aviator did a cover story and flight review on another Pipistrel electric aircraft, a privately owned Alpha Electro, published in the May/ June 2018 issue. A major difference between these two aircraft lies in the battery technology. The Alpha Electro uses two 10.5 kWh lithium-ion batteries that can be easily removed. With the ground charging equipment and a set of spare batteries, turnaround time is minimized by swapping batteries after each flight. In contrast, the Velis uses

“The time to recharge is about the same time it takes to discharge,” Sealand’s Mike Andrews told Canadian Aviator, meaning that it would take about 45 minutes to recharge after a 45-minute flight. “We’ve got a team of electricians and an electrical engineer helping us devise temporary and eventually permanent charging infrastructure at CYBL, CAH3, CAT4, and CYPW [Campbell River, Courtenay, Qualicum Beach and Powell River airports.]”

With no CO2 emissions and a considerably reduced noise footprint, the Velis Electro should prove popular with those who want a more environmentally friendly training experience. And with no direct fuel costs other than an increased electricity bill, and far less maintenance costs, the more than $300,000 investment

Sealand is working with Transport Canada to develop a training syllabus that recognizes the unique characteristics of an all-electric aircraft. Sealand will also require both a special airworthiness certificate and a special operations certificate from Transport Canada to operate the aircraft.

Sealand joins Ontario’s Waterloo Wellington Flight Centre, which has been operating a Velis Electro since early last year. Their experience has seen the aircraft achieve an average of seven circuits before arriving at the State of Charge (SOC) level of 30 percent, which is what Pipistrel sets as the reserve. This assumes an SOC of 100 percent when the power is turned on at the start of the flight lesson.

Watch for a flight review of the Velis Electro in an upcoming issue.

COMPILED BY AVIATOR STAFF

6 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

PHOTOS: PIPISTREL

Zippered Hoodie

Canada’s Red Canoe apparel maker is honouring the proud history of the Royal Canadian Air Force by offering in this 100th anniversary year a zippered hoodie emblazoned across the front with ‘RCAF’ and with an RCAF roundel on one shoulder and a stylized roundel with ‘100’ on the other. It’s available only in navy blue. Made of cotton-rich fleece. About C$100.

Learn more at redcanoebrands.com. Available from redcanoebrands.com and vippilot.com.

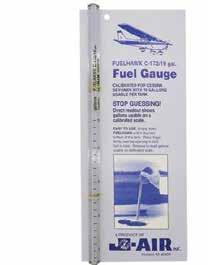

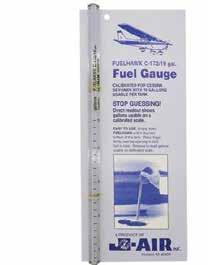

Fuel Dip Stick

Take the guessing out of fuel quantities by using a Fuelhawk transparent dipstick calibrated for the aircraft you fly. Stop relying on eye-ball estimates or crude sticks that don’t take the irregular sizes of typical GA fuel tanks. And, of course, never rely solely on panelmounted electronic fuel gauges that are notorious for erroneous readings. Select from common aircraft types with dipsticks calibrated for your specific aircraft model. Dipsticks for Cessna 152s through to 182s, and their various tank capacities, are available as well as for Cherokee 140s. Universal models are also available. About C$20 to $27.50.

Learn more at, and available from, pilotmall.com and aircraftspruce.ca.

ADS-B Receiver

uAvionix is marketing what they call the pingUSB, a dual-band ADS-B traffic receiver which allows users to be informed of nearby air traffic on their favourite electronic flight bag (EFB) app or on their desktop computer by using the built-in USB connector, allowing it to connect to PC-based air traffic monitoring programs. The device is mounted to a window using a built-in suction cup. It monitors both 978 MHz and 1090 MHz ADS-B frequencies and displays the monitored traffic on EFBs such as ForeFlight, EasyVFR, AirMate and Oz Runways via its built-in WiFi. The pingUSB measures 34 mm x 19 mm x 8 mm and weighs only 5 grams. About U$275.

Learn more at, and available from, uavionix.com

Engine Pre-Heater

Although by the time you read this, winter may have already come to an end. Nevertheless, now is a good time to reflect on the past few months and admit that there were a few days you decided not to go flying because the engine would have been too cold to risk damaging it with a very cold start. Reiff Preheat Systems of Wisconsin offers a thin and lightweight oil sump heater with dual 100-watt elements that is thermostatically controlled. Approved for use with most GA Lycoming and Continental piston engines. About C$393.

Learn more at reiffpreheat.com. Available from reiffpreheat.com and aircraftspruce.ca

PRODUCT REVIEWS COMPILED BY AVIATOR STAFF

GEAR & GADGETS

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 7

AIRMAIL

Metamorphosis of a Fly Baby

I’m sure that many of your readers did a double take when they saw the cover of the Jan/Feb 2024 issue — a biplane Fly Baby. Most folks are used to seeing the Fly Baby as a low-wing monoplane. My late friend Peter Bowers used to bring his original Fly Baby (N500F) up to the early Abbotsford Airshows, and one year he brought along some extra wing panels and converted it to a biplane at the show. See a scanned slide from the (1963 or 1967) show.

Jerry Vernon President, Vancouver Chapter Canadian Aviation Historical Society

An Islander for the Island

BACK WHERE SHE BELONGS?

Back in 1969, a successful logging company owner, Donald E. Braithwaite, of Campbell River, British Columbia bought out his accountant partner in Trans Mountain Airlines (TMA), changed the name to Gulf Air and relaunched the popular Class 4 Vancouver Island air service. That same year Braithwaite purchased a Britten-Norman BN-2 Islander from the Isle of Wight factory in the United Kingdom and gave it the Canadian registration of his initials, CF-DEB.

“What colour, guvnah?” came the voice over the phone from the British island.

Machine,’ but not on floats for this addition to the fleet, a tricycle-gear, 12-passenger light twin powered by two IO-540 300-hp Lycomings. Lots of flap, big high tail, land on a dime and give eight cents change with a funny door arrangement for control of the weight and balance when loading, and a typical British heater system with a three-position switch, cold, cold and cold. Good airplane: does everything it claims. The new Islander would join Gulf Air’s one single Otter amphibian to provide service into the increasing number of private dirt strips being used by the big logging companies.

steve@canadianaviator.com

“Paint it green,” replied Braithwaite. “What else?” muttered chief pilot Stan Kaardal, sitting nearby. “Everything else around here is green.” It being a joke that one should not stand in one spot for too long for fear of being sprayed Don’s favourite colour.

Thus, DEB became the next ‘Green

The big logging companies were suddenly the problem. Once 13 in number, they were fast disappearing, and a very new situation was taking place within the industry; financier Jim Pattison was about to take it over. He would buy all six of the floatplane operators on the Coast, calling the new company Air BC. He had over

FLYING STORIES

HANGAR TALK WITH JACK SCHOFIELD

us your letters Canadian Aviator welcomes reader letters on topics of concern to Canadian pilots and the aviation industry. Please be brief, to the point and polite in your submissions.

Send

Email Steve Drinkwater

8 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

EDUARD MARMET

120 Cessnas, Beavers and Otters, and many of them were destined to be auctioned off by a heavy-duty equipment auction house based in Vancouver. Sadly, there, amongst the many floatplanes on the auctioneer’s block, was our now-fading green Islander DEB. It was the first to go. A young novice aviator purchased it for the purpose of making a trans-Atlantic flight to Britain.

“You’re crazy to attempt such a flight in a utility aircraft like that,” said the man standing next to him at the auction. “I’m a Cessna dealer. I’ll take that machine off your hands and put you in the right airplane satisfactory for a trans-Atlantic flight!” This Cessna dealer was true to his word and joined the young man to fly the Islander back to his own home base close to Washington D.C. The young man purchased the recommended aircraft from our smart salesman, DEB was given a top overhaul on both engines and put on the lineup of aircraft for sale at his private airport.

that I would pass on their proposition.

“Good airplane: does everything it claims. The new Islander would join Gulf Air’s one single Otter amphibian to provide service into the increasing number of private dirt strips being used by the big logging companies.”

When I got to Vancouver on that flight I passed on the information to the dispatcher, and he sent me to Victoria to so advise the airline’s owner of this offer. I won’t dwell on this, but the owners must have thought I was complicit with the Qualicum businessmen and fired me on the spot! The old Greek parable comes to mind: “When in doubt, shoot the messenger.” When I confronted the group’s spokesperson, Ken Fyfe, with my news, he pushed a Trade-a-Plane under my nose, stabbing his finger on an aircraft listing, “I just bought that sucker lock, stock and barrel sight unseen, and you and I are going back to Cambridge, Massachusetts to get it!” Sure enough, it was an BN-2 listed by an eastern Cessna dealer. Ken Fyfe was a guy who made things happen!

That should be the end of DEB’s history concerning myself, but far from it. Fast forward to when I was employed by Burrard Air in the mid1980s. I was flying a scheduled seven flights per day between Qualicum and Vancouver International Airport. Prior to takeoff from Qualicum one morning, a party of six local businessmen approached me and asked if I would present a proposition to the current owner of Burrard Air to sell them one of his airplanes and transfer the licence for the Qualicumto-Vancouver service to them. They wished to keep the air service in good equipment and owned locally. I was a bit stunned by the request but agreed

Following a hilarious turn of events, we learned that there were two Cambridges in the U.S. and American Airlines helped us find the right one in the state of Maryland. (Sorry about that, Paul Revere!) They dropped us at Baltimore, Maryland, and we were picked up there by the seller of the Islander in a dazzling Cessna business twin. We whisked over John Kennedy’s favourite sailing waters onto final for the company’s private paved strip in Cambridge, Maryland. We could see the distant buildings of the White House across Chesapeake Bay as we descended. We could also see in a lineup of planes along the strip a high-tail in green with the now indistinguishable letters that I knew would spell Don Braithwaite’s initials — DEB.

To be continued in the next issue…

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 9

Will it Remain a Man’s World?

DON’T BE SO SURE

On more than one occasion in my career I have asked a colleague if I can borrow his muscle, similar to how one might ask if they could borrow a bigger hammer. My tools (or muscles) just aren’t quite enough to complete the task at hand. Bear in mind I do own the biggest breaker bar in the hangar — four feet of sheer will power — and it’s come in handy for a few of the guys, not just me. It may take my entire bodyweight to torque a propeller blade, and I may not be able to install a main tire brake assembly by myself, but being a petite woman also has its advantages.

While I ask to borrow muscle, my male counterparts ask to borrow my small hands. What might be considered a confined space entry for them because they must calculate how they’re going to fit their shoulders through the access panel, and what might happen if they get stuck, and what if they don’t have the right tools (they can’t just step out to grab something) is simply an in-and-out operation for me. When my colleague dropped his screwdriver in the bottom of the float bay, he sat peering in the hole for a long moment contemplating the best plan of attack to retrieve it. “Does anyone have a super long, strong

magnet I could borrow?” he asked around. I took one look in the small access panel and shrugged, “Hold my ankles,” and head-first I went.

The Air Tractor 802 is a unique aircraft and in many ways is a mechanic’s dream; the aircraft is made entirely of panels. Everything comes apart during maintenance, giving complete access to everything. I was recently assigned with removing avionics components from behind the cockpit. I assessed the area from both sides, confirmed what tools I would need, and climbed inside the structure of the aircraft, skirting over flight control wires and underneath

THE PLANE FIXER SWINGING WRENCHES WITH LIANA BUESSECKER

10 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

Author Liana Buessecker demonstrates her ability to take on tasks that most of her colleagues are unable to.

electrical bundles. When someone called for me and I responded, they walked by me twice before realizing where I was.

When a pilot reported a potential bird strike on a Q-400 during an aircraft turnaround, my superior immediately called me for the inspection because I fit inside the intake of the engine, saving tremendous time in having to lower the cowling. And while greasing the landing gear will never be anyone’s favourite task — there are 50-something grease points on each main gear of the Q-400 — I’m often given the task simply because I can climb up in the gear bay and reach all the grease fittings, whereas some guys who are taller and bigger cannot.

There’s a running joke that being small in the aircraft maintenance industry guarantees you specializing in fuel tank entry. It would certainly be a con if you were claustrophobic. Aside from any physical constraints, there are certainly other obvious obstacles as well.

There are a lot of organizations nowadays encouraging and advocating for women in the industry, and while they are incredibly inclusive and supportive, I’ve found they seldom talk about how difficult it actually is. Nobody wants to talk about the scary stuff in fear of it discouraging the next generation, but if we don’t talk about it now, then how will it ever change?

Aviation is an old boys’ club and anyone who tells you differently probably doesn’t work in maintenance. I have fought for my seat at the table and to prove I deserve to be there. There are certainly dinosaurs in the industry, old men set in their ways who refuse to be inclusive or admit the industry (and the world) is changing, but there are also men on the other end of that. My team at Jazz in Calgary was the best crew I have ever worked with. At no point did I ever doubt myself or my place, and neither did they. I owe so much to those guys, because if I hadn’t had such a positive experience with them, I may have given up in rougher water.

My experience hasn’t always been as smooth sailing as my time there. I have

had men tell me to consider a cleaner career, something I will be able to continue doing when I inevitably bear children — do I even understand the potential dangers aviation poses to a fetus? — and to stick to what women are meant to do.

Even when I took a temporary desk position in quality assurance during the pandemic, I was doubted: how could I possibly know everything I needed to know at my age?

from their toolboxes? Was I going to demand to be treated differently (or specially) because I’m a woman? And if the answer to any of those questions is yes, that woman probably doesn’t have what it takes to thrive in maintenance.

“Aviation is an old boys’ club and anyone who tells you differently probably doesn’t work in maintenance. I have fought for my seat at the table and to prove I deserve to be there.”

I’ve had guys physically take tools out of my hands and tell me they are surely too heavy for me to handle. I’ve been the last given an assignment, only to be tasked with paperwork. I’ve been asked if I’m okay to do that job because I might get dirt under my nails. I’ve spent an entire shift holding a flashlight for someone else, and I’ve had a complete stranger and grown man think it’s appropriate to ask how much I weigh.

When my colleagues heard a woman had been hired, they admitted to me some time later that they were initially nervous. There wasn’t a single other woman in the hangar: were they going to have to worry about everything they said? Would they have to remove any dirty or inappropriate stickers

To the men who were worried about the language they use: I’m a firm believer that cussing at the aircraft gives you extra strength, and remember I can use all the extra strength I can get. To the guys worried about what they have pasted on their toolboxes: I see your Vegas stripper cards and raise you a Thunder from Down Under calendar. And to anyone worried I’m going to ask for special treatment: I will absolutely challenge you to a donut-eating competition — I will lose by a long shot because I am tiny. And immediately after I will grunt and groan as I drag my six-foot toolbox across the floor to prove my tools are bigger and better than yours.

Being a woman in a man’s world isn’t always sunshine and rainbows. But here’s a fun fact about women in aviation: we are resilient. When you say jump, we don’t ask how high, because we’re already busy giving it our all.

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 11

Servicing a four-engined Avro RJ85 AT aerial tanker.

The Douglas DC-3

A LEGENDARY WARBIRD CUM CANADIAN BUSH PLANE

My flattened fingers eased the Douglas DC-3’s throttles to takeoff power and 56 spark plugs encouraged miscellaneous engine parts to come to life. Empty, CF-FTR weighed 16,939 pounds with the 1200hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830s turning 11-foot, 6-inch hydromatic propellers at 2,700 rpm. As airspeed increased, vibrations shifting from the pebbled airstrip encouraged perspiration aromas to ascend from my flight suit and flavour our microworld. At 76 knots, the 64-foot, 5-inch fuselage levitated and moments later the ‘C-47B-25 DK’ turned to a southward heading. We were going home.

A few weeks before, Gimli-based First Nations Transportation operations manager Fred Petrie suggested joining his organization as a ‘Three’ captain. In

1973, I had occupied the right seat on a trio of the elegant ‘sky climbers’ for Arctic Air in Fort Nelson on the Alaska Highway. Other opportunities brought on departure before gaining enough experience to slip to the left. Now, decades later with several more piston radial types in my logbook, Petrie had no idea he offered a route to a long-sought goal. The first look at CF-FTR in Gimli, north of Winnipeg, however, was not encouraging.

Below the 14-cylinder powerplants pooled oil from the 48.2 imperial gallon tanks darkened the hangar floor and above, pink hydraulic fluid glistened in wheel wells. Greenish fuel dripped from drains and the belly batteries released white acid streaks as far back as the elevator. Dents and dimples marked the age-tarnished 24ST fuselage while

slipstream-shredded duct tape patched the seagull-stained control fabric.

Dried ice cream made the 38-foot cargo floor slippery and grease from squashed plastic pails dotted the walls. Reaching the so-called “Place of Repose,” or cockpit, meant stepping over a cable winch bargained from Gimli’s Canadian Tire. A finger-printed Trimble 300 GPS with cracked plastic case lurked in a panel opening crafted with a hacksaw blade. Visual flight rules only. Freight runs would take place where herds of turbine twins dominated lightning-blasted boreal tracts near Manitoba’s Indian settlements. We were not exactly ploughing pioneering furrows into wilderness sky. Air services from hundreds of miles around sent their white-shirt multi-striped prima donnas north.

TALES FROM THE LAKEVIEW BUSH FLYING WITH ROBERT S. GRANT

Compressed seat padding brought little comfort in CF-FTR. Each 1200-hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 weighed 1467 pounds and on runs north of Gimli, loads averaged 7,000 pounds. 12 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

Together with fellow captain Gary Foster and swamper Brad Danks, we dared not neglect broadcasting positions as we steamed forward above Jack pine, spruce and muskeg mud between fog patches. Maintaining guard for microwave towers and inbound melees of IFR traffic formed our safety package. On crushed rock airstrips, we strove to plant our 1700 x 16 tires at the extreme end; never beyond thresholds as flight schools taught their novitiates.

After retraining with DC-3 virtuoso Duane Dick, chief pilot Jeffrey Schroeder arranged a Transport Canada check ride in Winnipeg with an examiner who concluded the air test with passing marks. Back in Gimli, Schroeder reviewed my God-forsaken nose-down steep turns and erratic approaches and kindly kept me on the payroll. After line indoctrination, work began exclusively for North West Company retail stores.

Built in 1944, CF-FTR’s documents showed almost 27,000 hours under many owners. At allowable 26,900-pounds gross weight, fuel burn averaged 600 pounds per hour hauling merchandise absolutely essential beyond civilization’s solace. Company loaders herc’d down Ecuadorian bananas, Winnipeg cheese snacks and Mister Noodles on colour-coded wood pallets. Once, a 42-pound Tummy Trimmer rattled beside cardboard-wrapped Ford panels along the sloping floor.

and so were the spiders observed behind wall panels.

At most destinations a forklift stood by to unload, but at the quiet Cree community of Red Sucker Lake, none existed. Every pound, package and piece of leather-covered furniture had to be manoeuvred through the two-piece left side cargo door. On ‘pop runs,’ never-ending soft drink cartons blistered our palms, and the crushed ones soaked our socks. Occasionally, passing pilots volunteered to help unload yet stood

did their damage and the hand-pumped hydraulic floor jack bruised through safety boots.

For the project’s final engine start, we electric-primed, set throttles and cranked propellers 10 times before flicking on magneto switches. Bluish black smoke enveloped cowlings and orange flame sheeted backwards in the dim dusk. Both R-1830s idling smoothly, Foster read checklists and the 45-psi tires softened the ride as we taxied away. No one said goodbye or thank you.

stunned when they stepped into CFFTR’s stone age “functional minimalism” and gaped at frayed bungee cords supporting the compass. Most marveled at the labyrinth of aging pistons, pushrods and pumps saturating soil below the wheel wells.

Airborne, the 95-foot multispar fail-safe wing carried us homeward as the magnetic compass seeped fluid and the bungees blurred. I looked back into the cargo compartment where wood chips and steel wrapping bands danced on plywood-protected floor panels. Hercules straps dangling from the ceiling resembled a Rastafarian wig. In cruise, our team relaxed. Antique, no doubt, CF-FTR, one of 13,142 Douglas DC-3s produced, fulfilled its task. Not once did an engine self-destruct internally, and no wind-blown cargo doors pulped anyone’s fingers.

Cruise at 124 knots usually took place below 5,000 feet or potato chip bags burst. Trickling fuel drums and fluttering zinc chromate flakes improved our lunchtime sandwiches. We dreaded rain. Downpours penetrating window seals through rolled-up paper napkins soaked our knees. Liquid dribbling into the Trimble GPS rendered it useless. Navigation charts turned to mush. Lacking radar, radio altimeters or strike finders, we appreciated the gift let loose by Mr. Donald Douglas on December 17, 1935. Blackflies resting on the tape-wrapped control column were happy campers

Petrie landed a weekend contract to move prefabricated houses from Gillam, 107 miles southeast of Thompson, to the settlement of Shamattawa. Esprit de corps really shone at FNT even on days off and everyone, including the Curtiss C-46 crew, resolved to do the job. Each leg averaged 35 minutes. Tons of lumber, galvanized nails and glass windows went aboard, and we levered everything out at destination. Despite leather gloves, slivers channeling under fingernails brought on what writer Ernest Gann described as “consuming waves of agony.” Scalp-scraping doorframes

At Gimli, 45° landing flap helped touch asphalt at 85 knots and, a few weeks later, the cold weather season shut First Nations Transportation down. I had revelled in the shimmers, shakes and thuds of an exhaust-stained legacy, but knew brief exposure to the “Vomit Comet” could not make me a DC-3 artisan like the Sam Coles, Daniel Genests and other masters who came before. The bonus came from several hundred sovereign hours handling a great, great airplane and inexplicable delicious moments known only to those who fate blessed into the left seat.

Besides gazing at muskeg mud, another bonus fell my way during the same summer odyssey. Fragrances of splashed 100/130 avgas on my boots lessened wait times in Gimli’s supermarket checkout lines.

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 13

Every board, pipe and nail keg was moved by hand and more than one finger found itself flattened during flights from Gillam to Shamattawa.

The Perils of Ferry Flying

HOW A TWO-DAY FLIGHT TURNED INTO A MONTH-LONG JOURNEY

Afew months back the owners of Kanata Aviation Training in High River, Alberta asked if I’d help one of their recently graduated students, Tim Taylor, ferry a Cessna 210 he’d purchased in Texas to its new home near Calgary. Being a big fan of 210s, I jumped at the opportunity. After all, what do airline pilots do on their days off, if not go flying?

The final plan had a lot of moving pieces. A major winter storm was forecast to hit the Denver region less than 48 hours after our arrival in San Antonio, making departing Texas early the next day critical. To up the stakes even more, I was due to ferry another airplane, this one a Boeing 787 with 275 passengers aboard, to London just four days later.

Before I tell you what actually happened, first let me share a few things I’ve learned in nearly 50 years flying GA. First, never board an airplane with the express purpose of picking up another

airplane until it’s been confirmed the second aircraft is fully reassembled, signed off as airworthy and is literally ready to go. The second rule: if your schedule is weather-dependent or even remotely time-critical, plan to fly another day, week or even month. Suffice it to say we were both ignorant of Rule No. 1 being broken by an unknown third party and were far too optimistic about our ability to work around Rule No. 2.

Day 1. Arriving in San Antonio, we jumped into our rental car and zipped out to nearby Castroville Municipal Airport. Our ambitious plan depended on me test flying the Cessna that afternoon, then be poised to depart early the following morning. What we discovered instead was a 63-year-old 210 in what appeared to be a million pieces. Attending to the mechanical fray was the airplane broker’s hired mechanic, a less than confidence-inspiring gentleman. In addition to finding it necessary to

expound on his limitless knowledge of Cessna aircraft, he insisted on throwing in repeated references to musician George Strait, whom we were presumably to infer he knew personally.

My love of country music notwithstanding, as the yakking continued, I found myself growing increasingly uneasy with his selfproclaimed expertise. Rather than wait out the process at our hotel, we instead elected to discreetly hang around and oversee the reassembly of Tim’s 210 from a polite distance.

Mercifully, just before noon the next day, the 210 was finally ready to fly. George Strait’s good buddy insisted on conducting the test flight personally, with me watching from the right seat. The finale was his literally slamming the big Cessna onto the runway, passing his poor handling off as “short-field technique.”

With all the hullabaloo behind us and with tanks topped off, Tim and I finally

EXPERT PILOT FLY LIKE A PRO WITH RICHARD PITTET

14 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

Owner Tim Taylor’s newly purchased Cessna 210 at the Castroville, Texas airport.

set out north. The vintage 210 was easily grounding 170 knots under a scattered layer. If we could just get beyond Denver before sunset, we’d be in for a short Day 2. To add to our operational constraints, I prefer not flying an airplane I don’t know well after dark and won’t even consider flying one that is new-to-me and untested, in cloud.

All was going smashingly. Then, about an hour north of Castroville, came this unsettling observation. “Rich… we’re losing fuel.” Tim was watching the left and right fuel quantities slowly moving towards ‘E’. This couldn’t be. Then I recalled the mechanic’s reference to issues with the fuel lines in the wings. Or could it be the Monarch brand fuel caps leaking?

On the “everything’s ok” side of things was analog gauge behaviour following an electrical power loss, specifically that an AC-powered gauge will remain at the last indication shown at the time of electrical failure. In contrast, a DCpowered gauge will move towards zero, making you believe something that might not be the case. In short, “AC lies, DC dies.” The fuel gauges were DCpowered, suggesting that the real culprit was an ongoing electrical failure, but nothing else supported that theory.

In the face of conflicting information, always believe the bad news, especially the sort that will kill you. We were either experiencing a total electrical failure or were about to deal with the more critical problem of fuel exhaustion. Either way we had to land.

In less than 30 seconds we’d carved the big 210 around and pointed it at the nearest field, which turned out to be Brady, Texas. As an added precaution, I elected an overhead break. Minutes later we landed without further event, taxiing to the apron, propeller still turning.

By the end of that first evening, Larry, an octogenarian aircraft mechanic, confirmed that the airplane’s battery was indeed kaput. This wasn’t a surprise; it had seen 12 summers of use, followed by a full year of total neglect. The following morning, with a new Concorde battery installed, we made it just 15 miles north before weather forced us to turn back.

For the next two days we sat in what is known as the “Heart of Texas” waiting for the stationary frontal surface — maliciously parked over Curtis Field, to eventually move. By the end of the second day, my work schedule required that I fly home to Calgary.

A few days later the weather finally broke. Tim and another ferry pilot once again set out for Calgary, only to have a carbon monoxide detector alarm go off when cabin heat was selected. The previous owner had paid to have both exhaust manifolds replaced but neglected to replace the downstream mufflers. Fully corroded, the holes in those components let CO into the cabin heat system, which in turn was the source of the deadly carbon monoxide leak into the cabin. There’s a valuable lesson here about the value of CO detectors and logic of replacing critical components, such as mufflers, when upstream items are no longer airworthy.

Nearly a month has passed since our truncated ferry mission, and I eagerly await the call to complete the delivery. When I last spoke to Tim, his new-to-him airplane was still in Brady. FedEx had lost the set of new mufflers somewhere between California and the Lone Star State. Not one to let a situation get the best of him, Mr. Taylor has Larry, the scooter-driving airplane mechanic, busy installing vortex generators on the 210. VGs will improve the airplane’s already good short field capability and low-speed handling.

Despite everything, the trip had many pluses. I can confirm that I still love Cessna 210s and have added Tim to my growing list of pilot friends. As for Brady and nearby Curtis Field, it turns out that some of the friendliest people you’ll ever meet can be found in the Heart of Texas. That and the best dang Mexican food north of the Rio Grande!

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 15

Behind the Scenes at the 2023 WAAC

WE HEAR FROM TEAM CANADA’S COACH AARON M c CARTAN

Greetings, my neighbours from the North. Presumably, many readers are aware of the sport of aerobatics yet may not follow the individual competitors. Perhaps a brief introduction is in order. I’ve been involved with competitive aerobatics since 1991 and actively competing since 2007. My competitive career has enjoyed success at regional, national and international events. I’ve been a member of three U.S. aerobatic teams between Advanced and Unlimited.

Almost 10 years ago I met Luke Penner at his competitive debut in the United States and our friendship commenced. We collaborated for many years culminating in his win at the Canadian National Championship during Team Qualification in 2022. Over those years I was gradually introduced to more members of the Canadian aerobatic community, but the trip to Rocky Mountain House, Alberta in 2022 supporting Luke and his protégé, Jesse Mack, introduced me to all but one of the 2023 team candidates. That’s the short version of how I opened the door to coaching a national team.

What does an aerobatics coach do?

Coaching is an interesting role that wears many hats. To perform the duty properly one must develop a good relationship with each of the pilots under their charge. Aerobatics is part physics and part artistic performance. Think of it as an aggressive ballet in the sky. To perform at a high level in this sport, the burden is upon the pilot to present the illusion of perfection and the only way to really hone that presentation is with ground coaching. The coach must understand the expected outcome, learn some of the idiosyncrasies of the airplane and learn the psychology of the pilot. Somewhere in the mix exists a challenge

of identifying mistakes or deficiencies in the performance and being able to communicate a solution to the pilot. The coach also needs to identify when the pilot has met their breaking point and is unable to gain any lesson from the flight; fatigue plays a big role during training. Finally, the trainer must strike a balance between rewarding good performance and reassuring that a missed manoeuvre can be corrected by adjusting slightly. In essence, coaching means equal part professor, shrink and cheerleader.

In sports of high achievement like aerobatics, every detail matters. A change in your seat cushion changes the sight picture slightly, a funny grip on the control stick adds unwelcome pitch to the rolling elements. One miniscule change yields a drastic effect on the outcome of the flight. The key to this pursuit is consistency and faith. Each pilot had to place blind faith in their coach to develop a program tailored to maximize their performance.

In a catalog of thousands of manoeuvres there are times when we would hold back certain aspects or reroute training to attack a deficiency. Doing this at strategic stages and then shoring up those skill sets with related manoeuvres would build confidence and allow us to attack new skills. As each pilot progressed through the catalog there will inevitably be moments of frustration and those “a-ha” moments which are greatly rewarding.

Over the course of training Team Canada in 2023, I had pooled a career of training exercises, and even improvised several new events, to force our pilots to perform under the stressful conditions experienced in the World’s highest contest. One of the favourites was a random ‘Unknown’ figure exercise. At the very end of the flight, after all the prepared and briefed exercises were up to accept-

able standard, I would radio the pilot and ask for a manoeuvre completely outside the scope of that flight’s mission. The pilots absolutely loved the challenge of thinking on their feet while pushing fatigue limits. Ultimately this aided in our overall performance at the World Championships.

It Takes a Village

Early in my career I was working with the former trainer from the U.S. Unlimited team and found a struggle with what should be a simple manoeuvre. Loitering in the hangar between flights, one of my fellow pilots offered some satirical advice as we discussed our struggles. What started as a passing comment ultimately was the key to success. This experience shaped the culture of Team Canada’s training camps. When pilots on the team weren’t flying, they were encouraged

UNUSUAL ATTITUDES AEROBATICS WITH AARON M c CARTAN

16 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

to sit alongside the coach and spectate; especially if their teammate was operating a similar aircraft type. I would carefully integrate certain comparisons: “This is how it should look,” or “This was what you did differently,” or “Can you help them with this? You’ve been nailing it lately!” This would generate a significant increase in team collaboration and camaraderie. We all raise the level of performance together.

The Result

I could write volumes about competitive format and the level of airmanship required by our pilots to represent themselves at a World Championship event. For a follow-up, I could detail the judging process and how the margins of error between first place and tenth place are razor thin. A game of this calibre is won by the tiniest of details and graded in a very subjective manner which results in scores that aren’t the easiest to understand.

Team Canada’s overall finish at the 15th World Advanced Aerobatic Championships is remarkable and truly something to be proud of. As a coach and friend to the individuals under my charge, I could not be prouder of the progress made by each of our pilots.

At the World Championships teams were issued small event tents as a place to shelter from the sun and park individuals’ gear. Canada shared a tent with France, which was a fun dichotomy. The French team were strictly business. While polite and courteous, they were only on the airfield to conduct their flights and then departed immediately. Team Canada maintained a stronger presence during the contest by being the hospitable and gregarious personalities that the country is known for. Honestly, it was probably the most popular tent for passers-by and even became a social hub.

In the end, three of our aviators made the cut in the top 25 to fly the fourth and final round. For two being rookies at the

world-level, that is a remarkable standing. France won overall, being almost professionally backed and heavily funded, with Romania on their heels having nearly the same level of support. The U.S. was in third place, having several pilots with extensive world-level experience. Canada respectably placed fourth overall for their first full team showing in decades. That is no small achievement!

I want to close with a special thanks for Lenora Crane for her management of the team and Carole Holyk for representing Canada as our delegate to the CIVA regulatory commission. Those two ladies did more behind the scenes than I can credit. A debt of gratitude is due to Tara and Matt Granson for the countless hours keeping the fleet of competitors in the sky.

And finally, thanks to our Team Canada for having faith and putting in the effort to succeed. You are all exceptional as individuals and our mutual success was a product of your effort.

USD $99,000

2010 PIPISTREL VIRUS SW

2005 CESSNA TURBO 206H AMPHIBIAN USD $575,000

1980 BEECHCRAFT 58P

USD $299,500

1980 CESSNA A185F USD $375,000

USD $223,573

2024 PIPISTREL VELIS ELECTRO

USD $89,000 226-666-2192 / sales@apexaircraft.com APEXAIRCRAFT.COM WE KNOW AIRCRAFT

2001 MOONEY M20R OVATION2 USD $259,500 1962 PIPER COMANCHE 250

USD $78,000 CANADA’S EXCLUSIVE DISTRIBUTOR FOR CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 17

1972 BELLANCA CITABRIA 7GCBC

As Luck Would Have It

BEING MENTORED BY PWA’S CHIEF PILOT (PART 2)

Since getting my private pilot licence as an Air Cadet while in high school, I have been thwarted in my attempts to advance in my planned career in aviation due to my visual acuity not being the venerated 20/20.

Even though I had substantially more than the required flight time for the Canadian commercial pilot licence and had passed the exams and flight-tests, the Department of Transport was unrelenting.

It would be later that I was able obtain an American FAA commercial pilot certificate with multi-engine IFR and obtain employment with the U.S. Forest Service after obtaining a U.S. Immigration Green Card.

Now back to the story.

Distant Early Warning (DEW Line) Radar Operation contracts with other airlines also operated out of Yellowknife, NWT, and their crews, a motley bunch, frequented the Ingram Hotel’s bar and

café. Besides the Canadians, some were Americans, also English and some were German. Since it was only a few years since they were fighting each other in the Second World War, there were frequent disagreements that often led to a physical fight. Usually though, sanity prevailed, and the combatants were encouraged to shake hands and have another drink.

The Department of Transport was not often present so frequently the regulation book was thrown out of the window. This was especially the case with regard to drinking. (Eight hours from bottle to throttle.) On one such event a crew from Associated Airways at Edmonton were flying Avro York, registration CF-HMZ, which was loaded with its fuselage crammed with 10-foot by 10-foot lumber about 20 feet long. Well, the crew had not done much de-icing and there was still frost on the wings. The aircraft started

its takeoff run and it quickly became apparent to the pilots that, with frost on the wings and a full load of lumber and full tanks of fuel, the York was not going to fly and it was too late to stop on the snow-covered runway. However, the captain had the foresight just before going into the gravel pit at the end of the runway to apply full right rudder which turned the York sideways, allowing the lumber to break out the side of the fuselage rather than come forward into the cockpit which would have likely killed them both. No one was seriously injured and, except for the aircraft being a total writeoff, everyone was okay.

Sheldon Luck, chief pilot for Pacific Western Airlines’ DEW Line Operations, invited me out for a drink one evening in Yellowknife and asked me what it was like to have my father leave the family. He was in the middle of a divorce and

A PILOT’S LIFE LIVING THE DREAM WITH CHRIS WEICHT

PROPLINER MAGAZINE 18 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

This photo, of unknown origin, features an Avro York, CF-HAS, in service with TransAir. This aircraft is similar to CF-HMZ referred to in the text above.

was deeply concerned how this would affect his children. I told him how the event had affected me, which he seemed to appreciate. In fact, he seemed to make every effort to help me in my quest to fly for a living.

One of the PWA co-pilots had suddenly departed from the operation. Burt Sechrist, one of the American Flying Tiger contract captains, came to my room and asked if I would like to be his co-pilot on the Curtiss C-46E. He pointed out that he knew that I only had a private pilot licence, but the Department of Transport was close to a thousand miles away. As far as he was concerned, he knew that I was extremely keen, and he would help me build my time and experience. Sechrist pointed out that I would not be able to log the time in case my logbook came to the attention of the DOT. I agreed and started to learn about flying the big Curtiss. I still had to load freight and fill up the gas tanks but getting to fly and having the support of these great guys made it very worthwhile. One of the other co-pilots, however, made several complaints to Sheldon Luck and that eventually brought the charade to a halt.

Pacific Western’s C-46 activities on the DEW line was very much a bush operation. There was a radio range instrument approach at Yellowknife as well as several NDBs (non-directional beacons) along the Arctic Coast, but otherwise there were few navigational aids in the Northwest Territories.

One typical flight route was to DEW Site 10, Clinton Point, NWT, which was designated as PIN-1. The flight route would typically be flown for 261 miles direct to Sawmill Bay (SW), which had an NDB at 296 kHz. From there it was another 270 miles direct to Clinton Point NDB (UH) at 340 kHz. Or an alternative routing was via Contwoyto Lake NDB (WO) at 361 kHz, then direct to the coast and westbound to Site 10. It would typically take 2 ½ hours to fly from Yellowknife to Clinton Point.

Much of Canada’s Barren Lands and Arctic coast are located in an area of compass unreliability due to its proximity to the magnetic north pole. Of necessity, one must navigate using true north rather than

magnetic north, and all the instrument approach charts there are designated this way.

The Barren Lands are an area of featureless tundra wilderness covered by thousands of lakes and, to the north, it is above the treeline. In winter, which lasts over six months, it is in darkness and map-reading would not be possible.

Once at Site 10 we unloaded the freight and refueled out of barrels, sometimes with a powered pump but often with a hand-powered rotary pump. This often took a lot of time as the Curtiss C-46E had a fuel capacity of 1,400 US gallons. Fortunately, we loaded less than maximum fuel for the return flight to Yellowknife, one reason being that the fuel had to be flown in and its resulting cost was very high. Sometimes the weather or mechani-

“The DEW Line was built during the so-called Cold War. It was a system of radar stations set up to detect incoming Soviet bombers and provide early warning for a land-based invasion.”

cal difficulties required that we remain at the camp. If so, we slept in double-walled tents with a wooden floor and walls. There was an oil heater in each tent, and we of course always travelled with our arctic sleeping bags. Each camp had a cookhouse and even though the meals were simple there was always lots of food.

The DEW Line was built during the socalled Cold War. It was a system of radar stations set up to detect incoming Soviet bombers and provide early warning for a land-based invasion. The northern DEW Line starts from the Chukchi Sea on Alaska’s northwest coast, continues across northern Alaska and Canada’s Arctic coast as well as crossing southern Greenland. It was entirely controlled by the United States. They paid the bills, and they called the shots.

There were several Canadian airlines which had contracted with DEW Line Operations to supply air transport for the construction and re-supply of the chain

of radar stations. The primary Canadian operator was likely Canadian Pacific Airlines; however, others were Associated Airways at Edmonton, Maritime Central Airways, Pacific Western Airlines of Vancouver and others.

Sometime later, due to a slowdown of operations, we moved Pacific Western’s base from Yellowknife to Edmonton, Alberta (at the then downtown municipal airport which was known as the “Muni”) where we were housed at the Edmonton Inn. While there, I was a witness to the unfortunate fatal accident of an Associated Airways Avro York, which was heavily overloaded and never got out of ground effect and ran into a row of railway freight cars. At this time the number of flights by PWA was reduced significantly and I was returned to Vancouver and laid off.

I was fortunate in finding employment at the Department of Transport Meteorological Office at the Vancouver airport (then known as VR-AMF or Vancouver Air Mail Field) and started training as a Meteorological Assistant. After several months of training, I began making weather observations, tracked upper winds using radiosonde balloons, plotted weather maps with information obtained from freighters and passenger liners, as well as weather ships in the Pacific Ocean. This of course was long before the use of computers and weather satellites.

One advantage of this job was that I had the privilege of flying on DOT aircraft. On one occasion I flew in Beechcraft D-18S, registration CF-GXC, with inspector Bill Lavory from Vancouver to Calgary and, after an evening with his pilot friends, returned to Vancouver. (This was a job that became very useful later when I was able to resume flying for a living.)

I eventually got into a dispute with Chief Forecaster Patrick McTaggart-Cowan, who told me in no uncertain terms that he did not like pilots. (During the Second World War, this man was the chief forecaster for the Ferry Command at Gander, Newfoundland, and it was there he formed his dislike of pilots.) I told him that I did not like bureaucrats either. After a few unprintable words we then decided to go our own ways (mine without a paycheque).

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 19

The previous article discussed the basic Lateral Navigation (LNAV) approach — it is flown with lateral guidance by following the ‘magenta line’ and honouring the altitudes as depicted by stepping down in altitude at the appropriate location. As well, a technique to manually add a vertical path was shown using a rated descent to emulate an imaginary glidepath. This article will describe the same LNAV approach with a displayed vertical path.

The LNAV/VNAV (LNAV with Vertical Navigation) approach, formerly known as a Baro-VNAV approach, is a formally designed instrument approach using specific design standards. The path over the ground is identical to the LNAV approach. However, a glidepath, based upon barometric altimetry, is considered in the procedure design.

Owing to the challenges with barometric altimetry (non-standard atmosphere, etc.) a temperature limitation is imposed upon the procedure as the slope of the protected surface beneath the glideslope changes with temperature. This is shown in the depiction — if the airport temperature is within the published bounds, an approach is authorized using LNAV/VNAV. An observant pilot will notice that despite being a nominal 3° glideslope, the true flight path angle will vary with the temperature — a warmer than standard atmosphere will result in a steeper approach angle (and lower than normal engine power) and a colder than standard atmosphere will result in a flatter approach angle (and higher than normal power).

In general, the LNAV/VNAV approach produces lower approach limits than the LNAV approach; years

INSTRUMENTAL FACTS FLYING IFR WITH ED M c DONALD

LNAV

Source of Canadian Civil Aeronau tical Data: © 2023 NAV CANADA A ll rights reserved CYOW-IAP-3G 0 5 10 15 20 25 (NM) CYOW-IAP-3G OTTAWA/MACDONALD-CARTIER INTL, ON RNAV (GNSS) Z RWY 32 451921N0754002WVAR 14°W CYOW ATIS – 121.15 (En) 132.95 (Fr) ARR – 135.15 TWR – 118.8 GND – 121.9 SAFE ALT 100 NM 7000 WAAS Ch 80163 W32A APCH CRS 320° MIN ALT VODUL 2000 LDA 10005 CATEGORY A B C D LPV 567 (200) ½ RVR 26 LNAV/VNAV (min. -19ºC, max. 54ºC) 654 (287) 1 RVR 50 Knotsft/minMin:Sec 70370 LNAV 760 (393) 1 RVR 50 90480 110580 130690 150800 RNAV (GNSS) Z RWY 32 CYOW EFF 24 MAR 22 EFF 24 MAR 22 EFF 10 OCT 19 Canada Air Pilot Effective 0901Z 10 AUG 2023 to 0901Z 5 OCT 2023 NOT FOR NAVIGATION PURPOSES 20 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

+ Displayed Vertical Path HIGHLY ADVANCED APPROACHES MAKING THEIR WAY INTO GA PANELS

ago, the opposite was true and this was due to a quirk in the design criteria which has since been corrected.

In both cases of the LNAV and LNAV/VNAV approach, a temperature below 0° Celsius requires a temperature correction applied to minimum altitudes. Unlike the LNAV approach, however, a slight altitude loss when transitioning from the descent to missed approach is permitted as the missed approach design accounts for this.

The LNAV/ VNAV approach was originally intended for aircraft with Flight Management Systems (FMS) like those found on airliners and business aircraft. This type is available for general aviation aircraft in certain avionics. If Satellite-based Augmentation System (SBAS) is available, an LNAV/VNAV approach can be flown since a highly accurate altitude is available to the avionics. Consult your owner’s manual as different avionics have different restrictions.

“The LNAV/VNAV approach was originally intended for aircraft with Flight Management Systems (FMS) like those found on airliners and business aircraft. This type is available for general aviation aircraft in certain avionics.”

LNAV+V types of approaches that pilots must be aware of. All formally designed approaches with vertical guidance (LNAV/VNAV, LPV, ILS) are assessed for the area between the Decision Altitude (DA) and the runway for any obstacles beneath the approach path. In other words, with these approaches the pilot is assured that no obstacles will affect them as they transition to land; this is not the case of an LNAV approach with the vertical path added, using either the Stabilized Constant Descent Angle (SCDA) method in the previous article or the avionics provided guidance with an LNAV+V.

Some avionics provide a displayed vertical path with an LNAV only approach. Depending on the avionics, it may be identified differently. With the popular Garmin avionics, it is displayed as LNAV+V. In these cases, the database provider, Jeppesen for example, adds a vertical path to the approach by taking the runway elevation, adding a threshold crossing height, then projecting a glidepath (typically 3°) into the approach area. With both the LNAV+V and LNAV/VNAV style of approaches, the actual altitude of the aircraft is compared with the calculated altitude — the vertical display shows the deviation above or below this path.

There are significant differences between the LNAV/VNAV and the

A number of years ago a business jet had an “excursion” through some trees during a dark and stormy night; they flew the approach by the book, broke out of the clouds and continued on the vertical path to the runway not knowing that the visual segment of the approach was not free of obstacles as it was not an LNAV/VNAV approach (with the visual segment properly assessed), but an LNAV approach with the vertical path added.

Aircraft with GPS-only capability can fly instrument approaches to a high degree of accuracy with improved situational awareness. With either the SCDA technique or a computer-generated vertical navigation display, the traditional dive-and-drive has been replaced with a vertical path that significantly improves flight safety.

In my next article I will discuss the new, gold standard of approach navigation, Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) and the associated Lateral Procedure with Vertical Guidance (LPV) approaches.

For more information, contact KATHERINE KJAER 250.592.5331 katherine@canadianaviator.com CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE MAR/APR 2023 $6.95 CANADIANAVIATOR.COM RCAF Returns Home The AI & Flight Training COMPUTER-ASSISTED INSTRUCTION FPET Project PIETENPOL WINS AT AIRVENTURE Passionate about aviation, we engage, educate and entertain — which is why each issue of Canadian Aviator is read cover to cover and passed along to business associates, fellow pilots and friends. Advertise in the best-selling aviation magazine on newsstands in Canada

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 21

Want to Cancel IFR?

SEVERAL THINGS YOU NEED TO CONSIDER

What does it mean when a pilot cancels IFR? Do you know all that is involved with that phrase, what it means to ATC, and what’s left for you, as a pilot, to do?

When flying IFR, ATC is responsible for separation between you and other IFR aircraft. In some airspaces, such as Class B airspace, it may also include separation from VFR aircraft. In most airspace in Canada, VFR are not included in that equation as most is Class E controlled airspace where VFR isn’t subject to ATC clearances and instructions or Class G uncontrolled airspace, where no aircraft is subject to ATC.

In both E and G airspace, VFR pilots don’t have to talk to ATC and controllers may not even be aware of the presence of VFR aircraft.

So let’s look at this with respect to IFR aircraft and that final portion of an IFR flight: the approach to an aerodrome. As long as the pilot continues on an IFR flight plan with an IFR clearance in controlled airspace (in this case, a control

zone which reaches to the ground), ATC will assign tracks, altitudes or approach procedures as required and keep the separation between IFR aircraft.

Why would a pilot want to cancel IFR and give up ATC-provided separation?

Sometimes the weather is good at destination and a pilot doesn’t want to fly the extra miles downwind on an RNAV procedure or do a procedure turn to join final. Sometimes a pilot would prefer to conduct the approach visually, since flying into the traffic pattern without those extra miles saves flight time, fuel and bother in flying instrument procedures.

With no other traffic involved, such as an IFR departure with a departure clearance, ATC can usually permit this when a pilot requests either a visual or a contact approach. If departing traffic is involved, these may not be options.

Also, anyone who flies IFR regularly knows a variation of the old joke, “What does IFR mean?” with answers something along the lines of, “I fly restric-

tions.” Those restrictions are used to ensure separation, and they can be quite restrictive, especially in airspace not covered by surveillance systems.

This means that a departing IFR aircraft may have to wait on the ground for a period of time for an arrival to land. Strictly in terms of the IFR clearance, the departing aircraft would no longer have to wait for the arrival if the arrival is no longer IFR. Thus, a pilot cancelling IFR on approach allows the departure to take off perhaps much sooner than the clearance might otherwise permit.

So what does this mean to the pilots involved?

At this point, I’ll make an aside. The pilot who cancels IFR is still required to file an arrival message to close the IFR flight plan just as if the flight were still operating on a clearance. This is done automatically on a pilot’s behalf if landing where AAS (Airport Advisory Service) or RAAS (Remote AAS) is provided by FSS or where a control tower is operating. Otherwise, the pilot

VECTORS ATC VIEWPOINT WITH

MICHAEL OXNER

22 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAR/APR 2024

must close the IFR flight plan via phone or through direct contact with the controller on a radio frequency, if available. Closing the flight plan may be done while still in the air, but the pilot should be aware that this stops ATC-provided alerting services, too.

Back to the recently cancelled IFR flight. The pilot is required to avoid other traffic, including VFR aircraft, operating around the aerodrome, just as before, and also the departing IFR aircraft.

A fairly common issue faced by pilots exists at single-runway airports whose configuration has only one or two taxiways, perhaps only at one end of the runway. For the sake of expedience, an arriving aircraft may elect to land on one end, and later wish to depart in the other direction to reduce taxi time. This leads us to planned departures wishing to take off into the approach path of arriving aircraft.

Because one of the aircraft is no longer IFR, ATC in the IFR ATC unit (usually the Area Control Centre) is not required to provide separation between the IFR departure and the now-VFR arrival. A clearance issued to a departure will not normally include provisions for said departure to manoeuvre around the arrival’s path because ATC no longer has authority over the arrival’s path.

When an arriving pilot cancels IFR to permit an IFR departure to take off, it is now incumbent upon the pilots to stay away from each other, and consideration must be given to a lot of things; most importantly, the timing of the IFR departure and the flight path assigned to that departure.

If the arrival is established on, or just planning to fly, a straight-in approach to landing and the departure is assigned or permitted a straight-out departure in the opposite direction with the IFR clearance, things can get tense quickly. Such

a situation may require the arriving aircraft to alter course to allow for the departure. Given the closure rates, this decision may have to take place early and quickly to avoid a nose-to-nose situation.

In most of these cases, ATC’s last ability to prevent an occurrence is removed when a pilot cancels IFR and, once that happens, the only thing left for a controller to do is provide traffic information. When these occur near airports, enroute ATC may be out of the communications loop since the aircraft will be on the mandatory frequency (MF) or aerodrome traffic frequency (ATF). That means the information will have to be derived from other sources such as FSS, where available, and/or other pilots.

While cancelling IFR can help move airplanes, caution should be used by pilots to ensure everyone knows what’s going on and that plans of action don’t lead to hazardous situations.

SUBSCRIBE AND SAVE ONE YEAR SUBSCRIPTION $26 (TAXES MAY VARY BY PROVINCE.) 1.800.656.7598 canadianaviator.com CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE QUICK SUBSCRIBE! RENO AIR RACES De Havilland’s Dragon Rapides THE MULTIROLE BIPLANES MADE THEIR MARK IN CANADA Fighting Wildfires THE ROLE HE PLAYED +Liberator Overdue BRITISH-CREWED AIRCRAFT DISAPPEARS IN B.C.’S MOUNTAINS The Curtain Falls on Iconic Championship Event CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE MAY/JUN 2023 $6.95 New Columnist: INSTRUMENTAL FACTS Supporting the Canadian Mining Industry HOW AVIATION PLAYS KEY ROLES +BrittenNorman’s Trislander ODDLY EQUIPPED FOR MINERAL EXPLORATION ANTONOV’S BACKCOUNTRY BIPLANE Aerial Yachting in Style GRAND CARAVAN An easy-to-fly modern workhorse QUICK SUBSCRIBE! J. Errol Boyd NEWFOUNDLAND’S INTREPID AVIATOR The Mystery of Roderick Island UNSOLVED 54 YEARS LATER +The 54th Salon du Bourget WE REPORT FROM PARIS CESSNA’S CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE MAR/APR 2023 $6.95 RCAF Returns Home The AI & Flight Training INSTRUCTION FPET Project PIETENPOL WINS AT AIRVENTURE BEECH’S STAGGERWING 90 years young – and still turning heads I Flew the Vulcan Bomber ON ONE ENGINE! CubCrafters Adopts a Rotax Designing Instrument Approaches WE TAKE YOU THROUGH THE PROCESS $7.95 CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE JAN/FEB 2023 $6.95 Stamp Duty Canada Post Stirs the Pot HAWKER HURRICANE Battle of Britain Workhorse Team Canada AT 2023 WORLD AEROBATIC MEET Ski-Flying ENJOY YOUR PLANE YEAR-ROUND Airbly Phoenix LOGGING-TRACKING + CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 23

GA’s Role in Maritime Searches

EVEN CESSNA 172 s HAD THEIR PLACE

Looking outside yesterday, the area where my wife and I live was blanketed in snow. Before six or seven years ago, that blanket could have been as much as a metre deep. But yesterday, light powdery snow about three centimetres deep was the case as it has been for these last six or seven years. Global warming?

Later that evening I thought back to my early years when snow in the winter was always deep. Then, unbidden, the memory of a Civil Aviation Search and Rescue Association (CASARA) search popped into my head. We were District 2, Halifax. I was Zone Commander then. We had two Cessna 180s and three Cessna 172s in our group. It happened that on Sunday November 22, 1987, I had planned an exercise practising track crawls. Kevin Layden and I had found a couple of open spaces in the woods some 15 miles from — you guessed it – Stanley Airport. We laid down orange tarps in the shape of small airplanes. Long story short, the exercise was well attended, and the crews were successful. I got to sit in on this one and man the radios.

When we began our search, I contacted the Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC, now JRCC) to advise them we had an exercise in progress just in case we could be of service. I was thanked and then we disconnected. I was surprised when not 10 minutes later they called back and advised me that they might require our services the next day. Could I have an aircraft on standby? That was a Monday, a workday. I knew I was available but that was all. I told them I would check my members and, if memory serves, I recalled one of the aircraft I had was searching for tarps. There were two C-172s and one C-180, all four-seat aircraft. From those three crews I was able to get three people who could commit to the next day if required. Kevin Layden, a pilot of his own homebuilt Rand KR-2 plane at Stanley and a radio operator for the Coast Guard, was available. Layden was our CASARA navigators training officer. The two spotters in the back seat were James Walker and

Marc MacPherson. Mike Doiron, who worked for Transport Canada, replaced MacPherson for our afternoon search. At 5:30 the next morning, RCC contacted me at home and tasked me to arrive at Halifax international airport (CYHZ) for briefing. I contacted Layden and he contacted the two spotters. Layden would then meet up with me and we would head up to Stanley to fly my plane to CYHZ.

As it turned out, it had snowed overnight and the temperature about 5 Celsius. When we arrived at Stanley there were small snowdrifts around, preventing me from getting my Cessna from its hangar to Runway 27/09. And even if we could, the runway seemed to be covered with a 15-centimetre layer of powdery snow with a slushy underlay. Although the snow had stopped, it was a grey day with a high overcast.