DEPARTMENTS FEATURES

always led the world in aerial

capability. Read how.

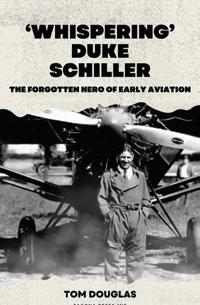

Tom Douglas

always led the world in aerial

capability. Read how.

Tom Douglas

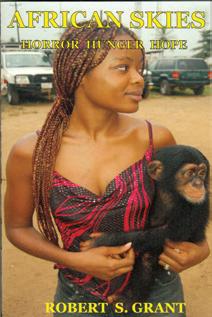

Robert S. Grant

Iwrite this on January 19, a day before Donald Trump becomes, once again, president of the United States. Tomorrow, we go to press. Of the many threats he has made against Canada in recent months, including using economic warfare to force this country to join his as some sort of “51st state” (without considering that Canada is a federation comprising 10 provinces that share co-sovereignty with the federal government, but I digress), the one threat that seems to stick and will have almost immediate threat is his vow to impose 25 percent tariffs on all imports from Canada.

There are many industries that would be adversely affected immediately, such as the automotive sector. Whether the energy sector is affected or not is yet to be apparent – the U.S. depends on Canadian energy (oil, gas and electricity) and has no way to replace it, at least in the short- to mid-term. Likely no tariffs there.

Rather, what I believe Trump is keen on is to force manufacturing jobs to move to the U.S., and those products may be the target of sustained tariffs, even if other sectors see relief. They are the automotive and aerospace sectors. I will focus on the aerospace sector here.

According to Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union, 88,200 people are employed in the Canadian aerospace industry with another 218,000 jobs supported by it. Not all are in the manufacturing sector, but a significant number are: think Bombardier, De Havilland Canada, Airbus Canada, Bell Textron, Pratt & Whitney Canada and CAE. There are several more, including smaller players such as Diamond Aircraft.

Should Trump make good on his threat to force manufacturing jobs to the U.S. that, in his mind, were outsourced due to globalization, we may see these aerospace firms targeted, especially those with American

parent companies, such as Bell Textron and Pratt & Whitney Canada.

We have already seen the result of American heavy-handedness when, due to import tariffs of nearly 300 percent on the Bombardier C-Series demanded by Boeing and approved by the U.S. commerce secretary in Trump’s first term, Bombardier was forced to sell a controlling interest in its airliner division to Airbus for $1. To get around the tariffs, Airbus set up a production line for the now-renamed A220 in Alabama, sending with it what should have been Canadian jobs. Sure, the tariffs were later ruled unjustified, but the damage had already been done. Production of the A220 in Alabama continues. Once a manufacturing plant is set up in the U.S., it is unlikely to leave, regardless of future administrations.

As of this writing, the future for Canada’s aerospace industry does not look bright.

My name is John Drummond and I am with Waterloo Warbirds at Kitchener-Waterloo Airport. In the November/December issue of Canadian Aviator there is an article authored by Victor Neskorozheny (On A Mission) regarding our MiG15 and pilot/owner Richard Cooper. There is a picture of the MiG on page 48 in a left-hand bank over the Grand River/ Cambridge Golf Course. Photo credit is given to Pat Hanna, which is not correct. This was taken on June 22, 2019, and I am the photographer and was in the photo ship (T33).

Canadian Aviator regrets the error. — Editor

Do you fly with children? Are you concerned that adultsized headsets might not be comfortable or even efficient for the young one? Pilot USA of Irvine, California has designed a passive headset especially for children. The Cadet has a smaller, lighter headband which is upgradable to an adult-sized headband as the child grows. Its padding is also sized for a smaller head. The boom mic is shorter as well. Ear cups come in red on one side and blue on the other. About C$225.

Learn more at pilot-usa.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca.

As glass cockpits proliferate, are fingerprints accumulating on the glass, especially on newer, touch-sensitive surfaces? EZClear of Signal Hill, California offer a cleaning pack that meets Garmin’s specification for use on their products. But of course, it is suitable for other instrument surfaces, including conventional steam gauges and iPads. The product is ammonia-free and has anti-static properties. Each pack contains enough product for 3 or 4 applications. About $56.

Learn more at ezclear.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

Wishing you had a better understanding of weather as it relates to aviation? Looking for a manual the is tailored to the Canadian environment and conditions? Look no further than the Royal Canadian Air Force Weather Manual. Used for training new RCAF pilots, Transport Canada has also endorsed it for use by civilian pilots. It is well suited for those studying for the Airline Transport Pilot Licence (ATPL) but can equally provide valuable knowledge to private and commercial pilots. Bonus: the manual comes with two CDs from Transport Canada which contain a series of two-minute videos on various topics, such as wind speed, ceilings, fog, etc. About C$70.

Learn more at, and available from, pilotshop.ca

Want to avoid consuming fuel just to provide 28v power to your aircraft’s systems while on the ground? No plug-in ground power unit (GPU) available? White Lightening of Lexington, Kentucky offers their 28-volt SmartGPU in both 54-amp and 114-amp versions. It provides stable noisefree DC power that replicates the aircraft’s own in-flight system. The accompanying smartphone app allows the pilot or other user to control the GPU via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi from the cockpit or from the hangar. The unit measures 19.75” x 5.38” x 9.25” and weighs about 20 lb with cables. Input voltage: 90-264 volts AC. About C$3,850.

Learn more at whitelightninggpu.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

If you wander into Vancouver’s Westin Bayshore Hotel on the city’s waterfront, you might notice a lobby display of aviation mementos of a bygone era. A pair of airliner seats from decades ago, stylish luggage that those who could afford air travel in those days might travel with, stacked nearby and a bar cart filled with champagne and cocktail glasses, all set against a wall where stylized images of airplane windows with views that might have been enjoyed by the rich and famous back in the day when air travel was glamourous. The sign above reads “Flight of Fancy.”

To an aviation aficionado, one might wonder why the hotel chose this theme for its lobby. If anything, one might have expected a scene depicting maritime scenes, given the 64-year-old resort hotel’s harbourfront location. So, why the aviation theme? One with knowledge of local history, especially aviation history, might associate the aviation theme to the fact that Boeing Aircraft of Canada set up shop metres away, still in Coal Harbour, when Boeing bought a fledging seaplane company owned by brothers Jimmy and Henry Hoffar in 1929. (It was here that Bill Boeing had his famous personal yacht built, the 125-foot Taconite, built in 1930.)

However, that is not the explanation of the aviation theme in the lobby. One needs to continue a few steps ahead to the lobby bar/restaurant, which is named “H Tasting Lounge.” Inside the space one notices continued, but subtle, hints of aviation once again; the logo on the menus featuring a stylized silhouette of a pre-war biplane, a pair of propellers mounted on a wall, a few small, stainless-steel models of planes from a bygone era scattered around the lounge, as if they were paperweights on tables in an outdoor café.

But the answer to this puzzle is

staring the observer in the face. It’s the H. It’s emblazoned on a wall flanked by the propellers. For this was once the temporary home of Howard Hughes, the billionaire tycoon who was a major player in Hollywood and once the owner of Hughes Aircraft Company, Trans-World Airways, and designer and builder of the Spruce Goose flying boat, one of the largest aircraft ever to fly. Younger readers might recall the name from the Martin Scorsese-directed movie The Aviator, in which Hughes was portrayed by actor Leonardo DiCaprio. The movie covered Hughes’ life between 1927 and 1947, so did not include his Vancouver residency, which began when the 66-year-old Hughes, by then a compulsive-disorder-afflicted recluse, arrived at the Bayshore Inn, as it was then called, with his bodyguards on March 14, 1972. He rented the top two floors of the resort’s tower and never left once

during his six-month sojourn. He might have stayed longer but, under Canadian law at the time, he would have had to declare all his assets to the Canadian government and forced to pay tax on the income they generated.

The BCAC is pleased to announce our 2025 flagship events. Please add these events to your calendar. For conference registration and event details: bit.ly/BCAC25

INNOVATION: EYES ON THE HORIZON CONFERENCE KAMLOOPS YKA

June 2- 4, 2025

November 14, 2025 bit.ly/BCAC25 bit.ly/SW25

SILVER WINGS INDUSTRY AND SCHOLARSHIP AWARDS CELEBRATION

Abbotsford, British Columbia-based Conair has announced the purchase of a pair of Daher TBM 960s. The company, which has been supporting wildfire control operations for more than 50 years, selected the 960 after a rigorous evaluation of various types.

“We are planning for our future with the selection of the TBM 960 aircraft, chosen after an in-depth analysis of 50 aircraft types,” said Conair Group president and CEO Matt Bradley. “Modernizing our bird dog fleet ensures our aircraft aren’t grounded by lack of parts supply, increasing maintenance, or obsolescence, when needed the most.” Bradley added, “Investing in modern aircraft gives our government agency customers the security of knowing the fleet is available to respond, offering lower operational risk at a time of crisis.”

The pressurized TBM was originally

produced by French light aircraft manufacturer SOCATA in collaboration with the Mooney Aircraft Company of the U.S., which at the time had French owners. The TBM’s design evolved from the Mooney 301, which had only reached the prototype stage. The resulting TBM 700 entered the market in 1990. Several variants later, the Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6E-66XT-powered TBM 960 debuted at Florida’s Sun ‘n Fun in 2022. The 960 enjoys a FADEC system (full authority digital engine control) and an Autoland feature, the latter being a first for the TBM series.

“Conair’s acquisition underscores the TBM 960’s versatility and effectiveness in highly demanding operational environments,” said Nicolas Chabbert, Daher Aircraft Division’s CEO. Daher, a 160-year-old family-owned conglomerate founded in Marseille, has several

interests in the aerospace industry, supplying Dassault, Airbus and Boeing with sub-assemblies. In January of 2009, Daher bought SOCATA.

“We are committing Daher’s full resources to ensure top-level OEM support for the TBM 960s in service with Conair, applying the expertise we’ve gained with our TBM and Kodiak aircraft that are deployed in multi-mission duties around the world,” said Chabbert.

Conair’s 960s will be modified by the addition of specialized avionics and other equipment specific to its bird dog role of providing surveillance as well as strategic and tactical direction to the onscene firefighting aircraft. A government fire control officer will occupy the right seat during the bird dog operations.

Both aircraft will be deployed in Canada during the 2025 fire season.

Founded by three former Airbus engineers in 2018, Aura Aero of Toulouse has obtained certification in Europe for the first of a family of three light two-seat aircraft the company is developing, the Integral R, the tricycle gear Integral S and the battery-electric Integral E. All models will be equipped with ballistic recovery systems.

The Integral R is aimed at the aerobatic training market and is powered by a 210-hp Lycoming AEIO390 engine. It is capable of 8.5 / -8.5 g load factors. First taking flight in July of 2020, deliveries were expected to

begin in January 2025 and continue with a total of 15 deliveries before the end of the year.

“We worked in close collaboration with EASA for the past years to get the Integral R certified,” said co-founder and head of airworthiness Wilfried Dufaud. “I am very proud today of how far we have come.”

The company’s ambitions extend beyond Europe. “We are now aiming for FAA certification for the U.S. market,” Dufaud said.

The company aims to obtain EASA certification for the Integral S later this

year. With tricycle gear, it is aimed at the basic flight training market. It will be powered with a 180-hp Lycoming IO-360-M1A engine. It will also be available with the Lycoming AEIO360-M1A engine to allow it too to be used for aerobatic manoeuvres. Length and wingspan of the S remain the same.

Next on Aura Aero’s horizon is the electric Intergral E, expected to be available in 2026. It will be powered by a Safran ENGINeUS Smart Motor and have an endurance of one hour when two pilots are on board.

LENGTH:

7.26 m (23.82 ft)

WINGSPAN: 8.78 m (28.80 ft)

HEIGHT:

2.48 m (8.13 ft)

ENGINE:

Lycoming AEIO-390/A3B6 (210 hp @ 2 700 rpm)

PROPELLER:

MT Propeller MTV-15-B-C/C193-25 (constant speed - 2 blades)

MTOW:

1 005 kg (2 216 lbs)

LOAD FACTOR:

+8.5 / -8.5 G (@ 795 kg / Cat A1)

+7.5 / -7.5 G (@ 910 kg / Cat A2)

CRUISING SPEED:

278 km/h (150 kt) @ 8 000 ft / 75%

MANOEUVRING SPEED:

300 km/h (162 kt)

STALL SPEED:

107 km/h (58 kt) @ 910 kg / Cat A2

VNE: 360 km/h (193 kt)

RANGE: 980 km (530 NM)

FUEL CAPACITY:

159 L (42 gal US)

LUGGAGE CAPACITY:

30 kg (66 lbs)

THE BRANCH IS NOW AIMING FOR IOC EARLY THIS YEAR

The Spanish manufactured Airbus C295 variant was meant to be operational in 2022. Several issues have caused the Initial Operational Capability (IOC) to be delayed, including the Covid pandemic and software issues surrounding the special mission capabilities the aircraft is intended to employ.

“While the delay is unfortunate, these types of issues are not unusual given the complexity of the capability being developed,” read a recent Department of National Defence press release.

The contract to purchase 16 of the aircraft, meant to replace the already retired six de Havilland Canada CC-115 Buffalos and the stillin-service Lockheed CC-130H Hercules, was signed in 2016. The RCAF took delivery in Spain of the first Kingfisher in December 2019. Five are currently on the ground at CFB Comox, where a new SAR training centre is located.

Full operational capability of the fleet is expected in 2029-2030. The Kingfishers will be based at various locations across Canada: CFB Comox (5), CFB Winnipeg (3), CFB Trenton (3) and CFB Greenwood (3). The remaining two Kingfishers will be dispatched as required for operations or as maintenance replacements.

SPENDING A NIGHT WITH FOUR OF THEM EVEN MORE SO

There were four dentists from New York City standing on the dock in the rain. Each of the men was wearing a woollen overcoat purchased from the Charles Tyrwhitt shop on Madison Avenue. Two of them, orthodontists, had brollies while the other two, periodontists, didn’t have umbrellas but were wearing fedoras. When they got into the seaplane you could smell their wet woollen coats. The camp guides, two young men with a 25 horsepower Mercury outboard, a gas tank and a picnic lunch in a cooler, were already in the back seat of the Beaver as I cast off and motored to the near end of the lake.

The human body generates 400 British Thermal Units (BTUs) of heat per hour

and, as we taxied out, the seven of us were generating 2800 BTUs, causing the windshield to fog up and run with condensation. Those wet woollen overcoats added to the process, and I was hardpressed to keep the windshield clear as we turned into the wind for the takeoff. The blast of air from the open window beside me would do the trick.

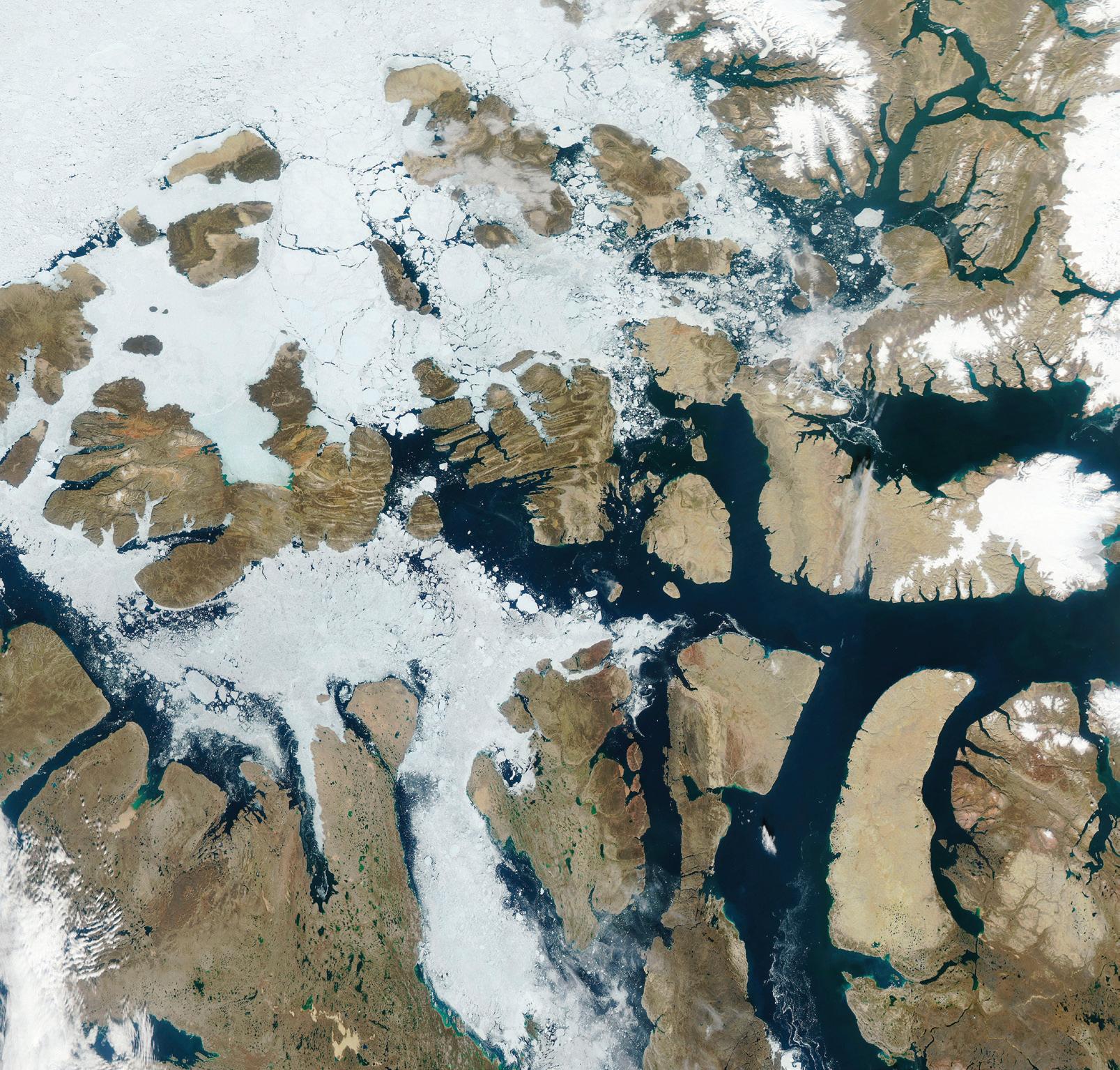

Let me answer your obvious questions: It was May 14, and we were at a sport fishing resort called Kasba Lake Lodge located a few minutes of latitude north of 60 degrees in the Northwest Territories. While most of Canada was basking in sunshine, we were taking off in a clear channel close to the shore while the rest of Kasba Lake was frozen

solid. The thaw had just begun. We were destined for a small lake 50 miles north where a 14-foot tin boat had been left last summer. I was to offload the guides and the four guests at the lake where these New Yorkers would have their first experience of fishing for Pike or Lake Trout. In retrospect, I am sure they would have been much happier performing root canals on Park Avenue. When we got to the lake — surprise, surprise — it too was frozen solid, and the guides suggested I land in the fast-flowing river from where they would hike to the lake and bring the boat down a little tributary and pick up the four well-dressed would-be fishermen. We carried this off rather well and

I was able to heel the seaplane onto a gravel bar in the river where the dentists and I awaited the return of the intrepid guides. I tried to open the conversation with some trivia about the long-term effect of mercury-based fillings, the effect of which was unknown to dentists of the 1930s, but I could not get a word out of the four New Yorkers. They were in total awe of what was going on, having never flown in a 65-year-old airplane, with a pilot of the same age, to a frozen lake to fish for the ugliest fish in existence.

I was happy to see them show some enthusiasm when the guides arrived in the tin boat but, before they headed off, I stopped them with, “Before you go anywhere...” They all looked at me as I checked my watch. “Unless you plan to spend the night here you must be in

this airplane, taking off out of this river at 3:30 — the very latest.” The guides all nodded with complete understanding that the ice fog would be setting in after that time and could prevent take off or could prevent a safe landing back at the lodge. They promised faithfully to comply. They arrived back at the plane at 4:20, half an hour after the ice fog obscured the river, making takeoff impossible.

“There’s a little cabin up that tributary a ways,” said one of the guides. “It’s very small but better than nothing in this rain.”

Did I want to leave a $500,000 airplane tailed up on a gravel bar in a swift running river? No, but I did, because they weren’t worth 500 grand back then—just a mere 90 thousand, so I joined the group for the hike up the little

tributary to what we loosely referred to as Shangri-La.

It was an extremely small A-frame with a dirt floor and no stove. Seven people standing shoulder-to-shoulder had to lean toward the centre of the room, conforming to the ‘A’ shape. One of the guides had the bright idea that a fire could be lit on the floor. He chopped a hole in the roof to let the smoke out, but you know what smoke does, so we all lay on the dirt floor and sucked fresh air from under the door until morning.

When I flew them all back to the lodge the next day, one of the dentists stopped me on the dock stating that he never knew about mercury-based amalgam being used in dental fillings back in the ‘30’s and ‘40’s, and could I recommend an airline with a direct flight back to New York.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS WITH W.T. (TIM) COLE

From October 23 to 26, 1968 I ferried No. 1 Beaver, CF-FHB, from Ottawa to Calgary. Why was this a memorable flight? Well, for several reasons. First, the aircraft involved was the famous Canadian bush plane that resides in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. This aircraft has been immortalized on Canadian coins and postage stamps. Second, while over the span of my aviation career there have been many ferry flights, this 20-hour flight was memorable because it was my very first long distance ferry flight. Third, it was a huge learning curve, and I took away a number of lessons from this four-day trip.

I was a young commercial pilot who had been flying for four years and had about 1200 hours flying time, and I considered myself an ‘experienced’ pilot. Little did I know I had a lot to learn.

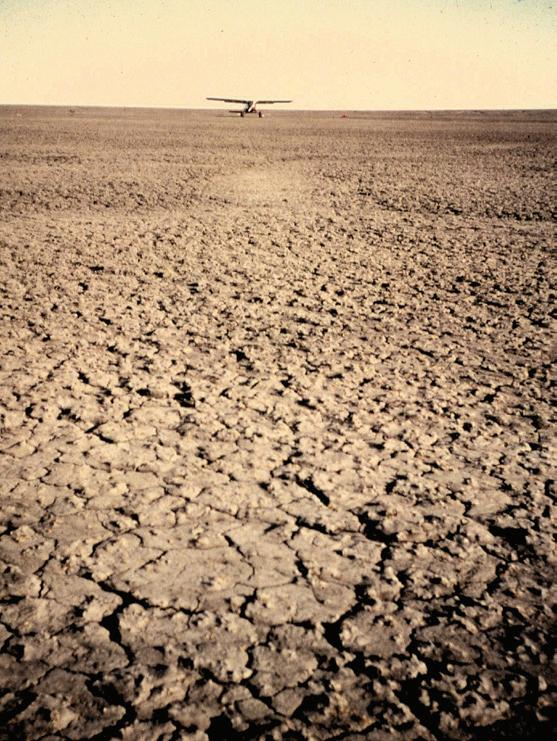

That summer I had been flying Beavers, on floats, for Laurentian Air Services from a base in Western Quebec. I had about 600 hours on Beavers and had about 400 hours in CF-FHB. Laurentian had leased the aircraft for the summer from a Calgary-based company. It was almost the end of the float season, and I was tasked with returning the aircraft to the owners in Alberta. Hey, this was pretty cool, and I was excited to make the trip. One of my main concerns was, “How would I navigate over the prairies?” Nearly all my experience was in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec, where navigation was relatively easy, using lakes and rivers to establish my whereabouts. “How was this going to work over completely flat

territory with no lakes?” The aircraft was changed over from floats to wheels and, when I was given a one-hour wheel checkout by the chief pilot, I was ready to go.

“How was this going to work over completely flat territory with no lakes?”

I flew from Ottawa to North Bay and then on to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. I chose to fly south of Lake Superior due to snow squalls and poor weather north of the lake. I carried on south of the border and spent my first night in northern Minnesota at Bemidji, the home of the legendary Paul Bunyan and his ‘’Babe the Blue Ox’. The friendliness of the American airport operators was outstanding. The next morning I headed off to Winnipeg for a real taste of prairie navigation. “Hey, it was a piece of cake. I’m not sure what I was sweating about.” My first real adventure happened at Brandon,

Manitoba. The lessons learned were: one, don’t reset circuit breakers, and two, don’t get so engrossed in the cockpit that you forget to fly the airplane. Here is what happened. As I was departing Brandon (they still had a tower in those days) I needed to communicate with air traffic control as I was taking off. The Beaver had a huge on/off radio switch that also doubled as a circuit breaker. It tripped off at a critical point and, as I only needed the radio for a few more moments, I reset the circuit breaker. It tripped off again and once more I reset it. This time it tripped off with a bunch of sparks and a burning smell.

“Guess I won’t reset that again, and oh well, I’m now clear of the control zone and as I can’t see or smell any smoke, I guess I’ll just carry on NORDO.”

While all this was happening, I was distracted for a few minutes and now it was time to see where I was and to start navigating to the next destination. As I looked out the window, this Eastern Ontario farm boy was looking at the oddest agricultural landscape I had ever seen. The flat prairie was dotted with random, extremely large, holes. It looked like giant moles were at work. A reference to the chart showed a ‘Restricted Area,’ depicting a military gunnery range. “Oh-oh, I think I know where I am. Better get out of here quick.” Well, the rest of the flight was uneventful, and I chose aerodromes that didn’t need radio contact. This went

well until I neared Calgary, which had a control zone that required radio contact with the tower. I located a Second World War aerodrome (Airdrie) that was closed and was just northeast of the Calgary airport. I landed there and was able to telephone Calgary to obtain permission to come in NORDO, relying on light gun signals. This is the first and only occasion in a lifetime of flying that I used the light-gun system. It worked just like a treat.

Well, feeling good about flying halfway across Canada, I felt pretty cocky as I booked my flight back home to Ottawa. But wait, the story doesn’t end there. The next day I’m in the back of a big cigar tube, a Canadian Pacific Airlines Douglas DC-8, taking off from Calgary’s main runway with an elevation of 3600 feet, and this is looking like the white knuckle express. In my four years of flying small airplanes, I had never flown in a large airplane. As

we were taking off, I thought, “This sucker is going and going and going with over two miles of runway, and it still hasn’t lifted off. Even in a Beaver with four passengers, the carcass of a moose and a canoe strapped to the side, never have I had a takeoff run like this! I have no control. If I feel like this, what do all these other folks feel like? Oh well, the only comfort I have is knowing that my emergency rations and my emergency hand cranked radio are buried in the belly of this beast and, if it goes down somewhere, I at least have the means to survive.”

It’s now a lifetime later and, having travelled on countless airliners and conducted many ferry flights in small airplanes, it is fun to look back at my very first trip across the country in good old Beaver No. 1 and reflect on the lessons learned.

May you have tight floats and tailwinds.

You arrive at approach minimums and you cannot see a thing. It’s time for a missed approach. How do you safely execute a missed approach and what are some of the considerations? And since missed approaches are such rare events, they inevitably are not textbook performances, to which I can personally attest.

While the missed approach physically begins at the missed approach point (DA or MDA [minimum descent altitude] for any vertically guided approach), the mental preparation begins long before that. Sometimes missed approaches are expected, such as when the weather is right on approach limits. Sometimes it is by complete surprise, such as when ATC directs a goaround due to traffic or any number of other things.

A good technique for any approach — visual and particularly instrument — is to assume that you will be doing a missed approach. Not doing a missed approach and landing is an unexpected bonus. This means ensuring that the missed approach procedure is available and briefed, the aircraft configuration changes are known, the navigation system is armed and the all-important altitude reminder is set for the missed approach altitude, lest you blast through it during the pandemonium that usually occurs during a missed approach, particularly an unexpected one. And most of all, aviate, navigate and communicate are the priorities.

Unless otherwise specified, missed approach climb gradients assume a 200- ft/nm climb gradient. However, this is not a climb rate that one would see on the vertical

speed indicator. If the required climb gradient is greater than standard, it will be published in the missed approach instructions. For example, suppose the published climb gradient is 300- ft/nm and your aircraft climbs at 120 kts or 2 nm/minute. The climb rate that you need to see on your VSI would be 300 ft/nm x 2 nm/minute, or 600 ft/minute.

Aircraft operators with an Operating Certificate must ensure that the weight of the aircraft on a particular flying day must be such that the aircraft can achieve the prescribed climb gradient after the loss of an engine. This is not the case for general aviation where it is the pilot’s discretion as to whether an all-engine or single-engine performance is used or not.

Mountainous airports provide the greatest challenges for climb gradients. Take the RNAV X Runway 34 at Fairmont Hot Springs (CYCZ) as an example. It has a little bit of everything. There is a non-standard climb gradient, 420 ft/nm, according to the vertical velocity chart. The nonstandard climb terminates at 6,600 ft where a standard climb gradient (200 ft/nm) can then be used. This is helpful if the aircraft doesn’t have the performance to maintain a high climb gradient at higher altitudes. With the aircraft at 11,400 feet at the RNAV waypoint EPSOD, the aircraft can hold while the pilot figures out a plan. However, to proceed in any direction thereafter, the aircraft must climb to 12,300 by shuttle-climbing in the holding pattern if necessary.

Missed approach procedures can be simple, or they can be complex like Fairmont; the key is planning and preparation.

HUH?

Aviation loves abbreviations and code words. One of the most common you’re likely to hear outside the industry is ‘Standby’ when being told to wait. The phonetic alphabet is also widely used in civil aviation and as someone who is comfortable using it regularly and correctly, I cringe when I hear someone say ‘A as in Apple.’

Being immersed in aviation my entire life, I forget not everyone knows the lingo that is so standard to me. ‘Whirlybird’ is a helicopter — the dark side of aviation. I understand the physics of how a helicopter flies and yet it still doesn’t make sense to me. They just shouldn’t work.

team, I was introduced to a few new aviation terms. The ‘bird dog’ is basically air traffic control in the sky. They are the brains of the entire bombing operation, giving target reports, wind calculations, aircraftspecific run descriptions and holding or drop clearances. In my opinion they have the hardest job of all because they have so much going on. The ‘tanker’ (or ‘bomber,’ depending where in the world you are) reports to the bird dog, dropping either water or retardant that was loaded at a tanker base, and the ‘skimmer’ has the ability to scoop water off a body of water.

When someone says they have to “put the birds to bed,” they are referring to installing intake plugs, prop ties, pitot covers and wheel chocks. In the morning, we get the “birds” ready for the day by removing all these items so they are ready for pilots to jump in and start up.

One of my favourite summer activities is watching the ‘Ducks’ — the Canadair CL215/415 amphibious flying boats — reverse park at tanker bases. (Because yes, those who reverse park are better than the rest of us, especially when it comes to airplanes.)

When I joined the aerial firefighting

Another type of aviation lingo that takes some getting used to is ‘maintenance language.’ Rarely do we write down full words, instead using abbreviations as frequently as possible. I considered calling it something other than ‘maintenance language’ because most pilots are fluent in it as well, but occasionally there’s one person who makes the attempt and basically comes back with the equivalent ‘A is for Apple.’

In these instances, maintenance is usually attempting to interpret a pilot’s snag. They may refer to a component as one name, while maintenance refers to it as another, or they include a location description that makes no sense at all. Then we find ourselves in a situation

where the pilot writes “Left phalange broken,” and our immediate reaction is “This plane doesn’t even have a phalange.”

If the only communication between the pilots and maintenance is a written snag in the logbook, pilots often include additional information in an attempt to be helpful. Usually it is, but there’s the odd occasion where we share the writing with other mechanics and we all have a good head scratch because there is no second wardrobe, and we’re clearly not facing the same left because there’s only two switches, not three.

Aviation lingo also revolves heavily around acronyms and on more than one occasion I’ve encountered a friendly competition between AMEs for who can sign a logbook using the most acronyms possible. For example: L/H I/B MLG WTL. RE/RE IAW AMM. NFF ATT.

This is a real thing I’ve written in a logbook and, if you can interpret

“Sometimes I’m not even sure the pilots understand what we’ve written, but they see our signature meaning “Safe for flight,” and that’s good enough for them.”

it, congratulations. You can consider yourself fluent in maintenance language. Sometimes I’m not even sure the pilots understand what we’ve written, but they see our signature meaning ‘Safe for flight,’ and that’s good enough for them.

When signing a logbook, from defect to rectification, it will always state what the issue was, what work was completed and the outcome; that the aircraft is serviceable. (It may also

require a flight to confirm the issue has been rectified, in which case it is “serviceable subject to satisfactory test flight.” The pilot-in-command is then the one who officially signs off.)

The above abbreviation can be broken down as the defect: L/H I/B MLG WTL, the work completed: RE/RE IAW AMM, and the outcome: NFF ATT.

In plain language, “Left hand inboard main landing gear worn to limits. Removed and replaced in accordance with aircraft maintenance manual. No faults found at this time.”

For anyone who may be in need of a good laugh, I recommend you look up ‘funny airplane repair logs’ on the internet. While I’m pretty sure these are all made up, I can assure you I’ve encountered some very similar and suspect write-ups during my career. (I’m squinting specifically at the pilot who wrote ‘circuit braker pooped.’ Must’ve been a long day.)

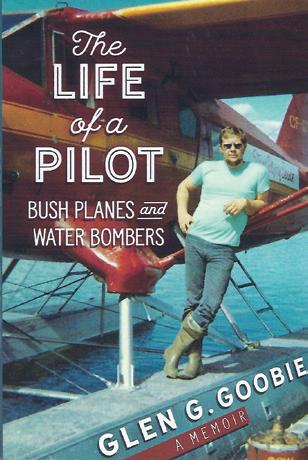

BUSH FLYING WITH ROBERT S. GRANT

Sometimes commemorative statues, street signs or lakes and landforms honour the men and women who contributed to the development of Canada’s immensities. Sadly, however, nothing more than a few pieces of lichen-coated airplane parts mark the spot where ‘The Hero of a 100 Rescues’ perished on June 5, 1956.

Arctic pilot Gunnar Ingvald Ingebrigtson’s parents and children immigrated

from Norway in 1927 and eventually settled in metropolitan Churchill. Although several siblings ventured into saltwater shipping, the thriving port’s aerial activity appealed to the young Norwegian Canadian. On September 14, 1943, as a teenager, he enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force and, at war’s end, returned to the isolated community where winter air transport north of 60° rarely occurred.

Ingebrigtson acquired a single-engine Stinson SR-8M Reliant (CF-AZV) and began probing boulder country west of Hudson Bay. The treeless voids became his backyard in the face of overwhelming parka-penetrating chills throughout the tundra. Coincidentally, Ottawa’s Roman Catholic Church authorities purchased a Noorduyn Norseman to assist in reaching supplicants beyond the range of dog sleds and snowshoes. Their new Montreal-built airplane became the first of many based in Churchill under the name Arctic Wings on August 10, 1948.

Ingebrigtson sold his Stinson CF-AZV to the new air service and became one of their main Norseman ‘drivers.’ Replenishment hops to exploration camps and Hudson’s Bay trading posts brought him face-to-face with winter whiteouts and potential conflicts with springtime migrating geese. ‘Igloo-hopping’ to isolated Inuit saved many lives and flights for injured travellers meant medical attention.

Left: Gunnar Ingvald Ingebrigtson understood the C-64 Noorduyn Norseman intimately and placed its 7,400-pound gross weight on sites demanding exceptional skill. He also learned how to dress for the Arctic chill.

“A good many fliers shun the whole region. I can’t blame them. Landing with skis on moving, undulating ice fields was bad enough,” wrote an unidentified journalist. “The deep crevasses under the snow, the half-frozen seas and the incalculable fuel-consuming distances of the Arctic took a toll.”

Ingebrigtson’s natural aptitudes became well-known throughout the Northwest Territories’ austere nothingness. Radio operators dependent on static-plagued HF communications recognized his accent. As flying hours filled his logbook, he ignored the fragrance of sealskin pelts and fox furs while caribou blood besieged his boots. Chesterfield-based Dr. Joseph Moody, who managed the only hospital within 300 square miles, became a confident client.

flew 5,025 miles in nine days on census missions with his Norseman CF-BAU. During a polio outbreak, the pair landed beside every shack, snow house and tent they could reach, regardless of personal health hazards. Admirers passed on tales of “Daring Exploits” and the “Heroic Arctic Pilot” to itinerant newspaper reporters and magazine journalists sentenced to the dreaded Barren Lands.

“Ingebrigtson’s natural aptitudes became wellknown throughout the Northwest Territories’ austere nothingness.”

“In time, he was to become my trusted companion on many expeditions and patrols; one of the few fliers with whom I felt safe in northern skies,” said Dr. Moody. “He was the only one who would persist when others quit, the only pilot where ingenuity was always ahead of the conniving elements.”

In January 1949, he and “Fogbound,” as Moody nicknamed Ingebrigtson,

In April 1949, Ingebrigtson unfolded reams of featureless blue-white navigation charts during a map-reading odyssey across saltwater ice and mountain ranges with aircraft maintenance engi-

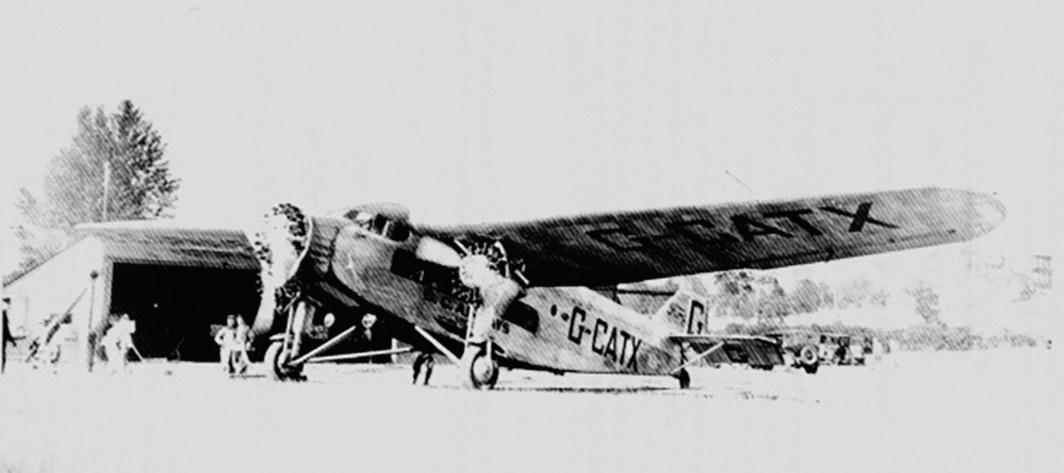

Whenever Norseman CF-GJL appeared in Canada’s Arctic, the 600-hp aircraft attracted attention, although a dog in the foreground showed no respect.

neer (AME) David Croal. They touched down on Eclipse Sound’s Pond Inlet on Baffin Island’s northern tip and marked the village’s first arrival of an aircraft. As Ingebrigtson’s prestige spread, transport needs increased, and long-distance flights became daily fare.

Ingebrigtson’s participation in what many outsiders deemed ‘impossible,’ brought international acclaim after exhausted fuel tanks downed an RCAF 112 (T) Squadron Douglas DC-3 onto sun-weakened ice fields. No injuries occurred to the 12 aboard. Grandiose recovery plans included a glider towed from Manitoba for a snatch-type retrieval. Other schemes included helicopters, dog teams and army vehicles. Ingebrigtson and military pilot Flight Lieutenant N.A Keene managed to alight within 100 feet of sea water to evacuate the crew moments before their landing field disintegrated.

“The aircraft was never recovered and currently rests at the bottom of Hudson Bay,” remarked historian Christopher Charland.

Praised as a “veteran northerner,”

(continued)

Ingebrigtson rushed to a burning Norseman which splashed into Kaminuriak Lake, 112 miles northwest of Rankin Inlet. The four stranded men, including some prominent Minneapolis surgeons, sustained themselves with birds and berries until his arrival. Their saviour understood; Ingebrigtson once spent four days in a snowbank cave enroute to York Factory on Hudson Bay.

Ingebrigtson amazed The Pas residents, 323 miles north of Winnipeg, during a zero-visibility snowfall on a quiet Sunday morning. Churchgoers heard a radial engine following the twisting high-banked narrow Saskatchewan River.

“Several residents saw him approach for a landing and drove to the scene to render help, but they found Ingebrigtson stepping calmly from his aircraft,” an awestruck reporter wrote. “He had zig-zagged along the river ice so closely that the projecting wings had missed each bank by inches.”

Ingebrigtson again attracted media mention in an August 1950 Canadian Aviation article, after being stranded in a “typical ground drive,” or snowstorm, 300 miles northwest of Churchill. He and AME Croal roped the wheel-ski Avro Anson in place and endured three days of gale-force winds. Months later, Ingebrigtson voyaged to relatively tropical Red Lake’s mining community to ‘drive’ Norseman CF-CPS and Fairchild 82 CF-AXL. Almost all trips to Cree settlements, such as Pikangikum, were brief; Arctic-like long distance flights were rare. He returned to Churchill.

Ingebrigtson placed his life on the line numerous times. His family had already lost a member when younger brother Leif drowned while helping park a floatplane in 1951. One of three sons and three sisters, Ingebrigtson decided to leave aviation to manage a theatre in Churchill. Undoubtedly within what poet Robert Service called “the race of men who won’t fit in,” he held out for 12 months before returning to what the same bard described as “ranging the field and roving the flood.”

Tragically, the media’s ‘Best Known Flier’s’ luck ended after departing Churchill for a 200-mile journey in Norseman CF-GJL with seven hours fuel, five passengers and 24-year-old AME Ronald Taylor. Weather reports indicated 4.4°C and excellent visibility with a 26-mph wind. After unloading at the McConnell River camp, he intended to search for potential airstrips solid enough to handle a follow-up Bristol Freighter.

“Gunnar has been missing so many times, but he always comes back,” said his father John E. Ingebrigtson. “This time looks a little different.”

After seven days, headlines announced, “(Air)Plane Sighted, No Sign of Life” when an RCAF Douglas DC-3 discovered CF-GJL’s crumpled wreckage. Ingebrigtson’s hand still held the throttle and Taylor’s arms stretched forward. An inquest described low ceil-

ings and focused on obscured visibility through the Norseman’s two-piece ice-covered windshield. Investigators pondered why the renowned pilot continued instead of waiting on the nearest lake, but Transair chief pilot William F. Wright pointed out that thawing ice would unlikely bear a Norseman’s weight. (Central Northern Airways and Arctic Wings combined to form Transair in 1956.)

In spite of more than 6,000 flying hours, Ingebrigtson had met his demise. Fellow pilot and friend Charles W. Weber accompanied Transair Douglas DC-3 CF-TET on wheel-skis to bring Taylor and ‘The Great’ Ingebrigtson home. Canada lost a self-reliant individual who brought comfort to Natives and non-Natives living within the shattering impacts of treeless terrain.

Intelligent, Ingebrigtson could have prospered in whatever trade or profession he chose — every family member and their descendants thrived. No grateful governments have honoured him, and airliners have never borne his name. Only a few lemmings pitter-patter through some broken tubing on an obscure patch of landscape somewhere near present-day Arviat.

A skilled Canadian pilot’s legacy should be acknowledged for his courage and compassion. Gunnar Ingvald Ingebrigtson has been overlooked.

IT’S PROBABLY NOT WHAT YOU THINK

Kiss’ landings and ‘soft field’ landings are often thought as one of the same. After all, both are gentle on the aircraft occupants and the airframe. However, their purpose and associated techniques differ significantly. One landing technique aims to enhance passenger comfort and minimize wear (and serve as an ego boost), the other aims to avoid an accident, more precisely, a ‘flip over’ accident. Kiss landings, also known as grease or butter landings, are normal power-off landings. Contact with the ground is nearly undetectable because the downward force upon touchdown is minimal and absorbed by the landing gear system. On the other hand, soft field landings are power-on landings suppressing any downward force upon touchdown in situations where the landing gear shock absorption system is rendered ineffective by the softness of the landing surface. Think fresh snow, mud, plowed fields or sand. The power-on soft field landing technique is also useful when operating on hard, but high-drag, surfaces that may produce a sudden deceleration after touchdown.

Landing gear systems vary in design but have the same goal, to help take the ‘shock’ out of our return to Earth. In the beginning, all aircraft had rigid struts. Most helicopters and many sailplanes still do. Rigid struts provide no protection to the airframe other than distance from the ground. When tires are attached, they do help soften the blow. The most common landing gear system designs are spring steel and shock struts. The first system relies on flexible strut material to cushion the contact with the ground similarly to tires, while the second uses the hydraulic concept to absorb shocks. Regardless of the design, the systems require a push-up force to activate. When the landing surface is soft, a normal touchdown triggers little

to no push-up force to trigger the landing gear shock absorbing system. Instead, it is the surface that absorbs the shock by self-compressing and forming a hole.

Normal and soft field landings begin with a power reduction followed by levelling off within a few feet of the ground, then patiently slowing down in ground effect right up to the moment when we start to run out of lift and the aircraft starts to sink. To execute a kiss landing, gently manage the remaining angle of attack range above stall to continue to control the descent rate for the last few feet. To execute a soft field landing, hold the pitch steady and use power as needed to reduce the descent rate to zero as the aircraft comes into contact with the surface.

main gear as much as possible. That too requires power to lighten up the contact between the third wheel and the ground as well as to leverage the prop airflow on the tail to help stir the aircraft. Braking is not really required on high drag surfaces as any decrease in power will slow the plane. Moreover, braking when the surface is soft might yield an unscheduled and lengthy full stop.

While the power remains off between touching down and reaching taxiing speed during a normal landing, the power must remain on after touchdown during a soft field landing to control how the front or rear wheel comes into contact with the surface. The third wheel must also meet the ground gently when dealing with a soft surface. Failure to do so spells trouble as it too can dig in if allowed to drop in. That is especially true when the surface combines softness and high drag characteristics. A quick deceleration upon contact will prompt an unwanted nose-down moment. In some cases, it will take more power to operate on the ground than it did to control the descent rate just before touchdown.

One thing to keep in mind when rolling along on a soft surface is to actively keep the weight of the aircraft on the

The best way to gain a feel for the normal landing technique is to practice approaches to power-off stalls from a descent. On the other hand, slow flight practice holds the secret to successful soft field landings. Of course, neither manoeuvre drilled at altitude can simulate the effects of ground effect and unfavourable winds during an actual landing. Pitch and power input will slightly differ close to the ground.

To really spice things up during practice, transition from a power-off stall approach (stall warning on) to slow flight without losing any altitude. That simulates the most challenging of all landing combinations, a short and soft field (one of my favourite requests during flight reviews to accurately assess pilot skills and knowledge). Anyone who can demonstrate such skills and ability to calculate a blended landing distance (short field approach distance plus soft field landing distance) should have no problem executing kiss landings on demand.

AIRMANSHIP WITH GRAEME PEPPLER

Aone-time U.S. national unlimited aerobatic champion once candidly stated in a seminar that the reason she took up aerobatic flying was to help her overcome her stifling fear of stalls. A legendary U.S. aerobatic performer who for decades lit up airshows worldwide has always been open over the fact that his reason for taking up aerobatics was to overcome his dreaded fear of crashing. In both these cases, these renowned pilots embraced an emotion – fear – that they found was impeding their enjoyment of flying. They leveraged that debilitation and turned themselves into exceptionally skilled, world-class stickand-rudder aviators.

Fear is a natural emotional response to the perception of a threat and to danger, and/or to the uncertainty of an outcome. It’s every species’ wired response to either stay and fight for a positive payoff, or to ‘get the heck out of here’ before something really bad happens. It’s an essential physiological method — fight or flight — that the body uses to safeguard its survival. It helps individuals react to potentially life-threatening circumstances to ensure that they live to see another day.

Fear focusses attention. It mobilizes the body to contend, one way or another, with encroaching unpredictability and/or with an immediate menace. In its helpful guise, it alerts you to fly well-around the unexpected cumulonimbus dead ahead instead of dealing with the possible dire consequences of trying to scythe through it. In its unhelpful guise, it can incapacitate you from flying your aeroplane at all, even when the forecast is CAVOK for several thousands of miles. Fear can, thus, be a means to enable constructive behaviour or, if mishandled, can lead to mental health conditions — phobias, anxieties,

“Fear focusses attention. It mobilizes the body to contend, one way or another, with encroaching unpredictability and/or with an immediate menace.”

oppressive panic — that can limit one’s capacity to get the most out of the things that, were it not for fear, bring the most enjoyment and satisfaction in one’s life.

Pilots can experience a chronic fear for any number of reasons. A bad experience with weather can leave one spooked to fly except on the absolute clearest of days. A nasty incident with crosswinds on a landing could fill one with the dread of having to deal with them again. Perhaps a mechanical incident on a flight — even if subsequently repaired — could pre-empt one’s confidence to fly their aeroplane again, for fear of something else going wrong. Or maybe, even despite occasional practice, one can fear a lingering lack in one’s own ability to respond to an emergency in a calm, measured and life-saving manner.

Fear can rear itself in many ways: even talking on the radio is a commonly whispered fear with which some pilots struggle, not least students and/or newly minted licence holders.

The best antidote to decreasing one’s fear is to build one’s confidence. And to build one’s confidence, one should take the time to best understand what induces one’s fear in the first place. In other words: learn from the fear. Fear can be the moat between where you’re currently standing and where you want to get to. Bridging that divide is achieved by overlaying the gap with layers of confidence engineered from the building of a well-supported framework upon which to eventually walk with firm steps.

Exposure therapy is an effective way to tackle fear. The individual who fears something — no matter how

much they may, paradoxically, want to do that ‘something’ — tends to avoid that which causes the fear in the first place. Such avoidance reduces the fear. But over the long-term, nothing is achieved to eliminate the threat of its re-occurrence nor from it becoming even worse. Exposure therapy breaks the pattern of avoidance and, in time, snaps the treadmill that keeps fear churning. By incrementally, and under controlled circumstances, exposing the individual to that which elicits their fear, can lead to progressively learning to cope with the fear, controlling it, and become habituated to it to the point of eventually eliminating it as an obstructive behavioural response.

Other forms of treatment that may be used to combat fear (and the

anxiety that fear can provoke) may include cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation training, meditation and breathing techniques, amongst others. Medications, too, may be a solution, though a strict review of medical guidelines is essential to ensure that any medications taken are completely compatible with the piloting of an aircraft.

Another way to reduce the fear of what frightens you into pernicious intransigence is to read about others who have dealt with the same issues. Let their stories guide your way just as they were freed from the unease that could have impeded their flying careers. Everyone faces fear at many times in their lives. The fact that others have faced it and persevered can

encourage you to do the same.

A three-time Indianapolis 500 winner — one of the legends of motorsport from the 1960s and 1970s — once stated to an audience at an aviation show that, despite his activities as a very active pilot, he was absolutely terrified of heights. Like the two aerobatic pilots mentioned above, his fear compelled him into action. For being so candid as to bring their fears into the public realm, these three heralded individuals deserve high plaudits. Their lesson: if something scares you about flying, it’s probably a good thing that can set you up to proactively sort it out. And as they showed, when managed the correct way, fear can make you a better pilot and raise you to heights you never thought you’d reach.

LIVING THE DREAM WITH CHRIS WEICHT

In October 2024 while in Southern Spain I took the opportunity to take a tour of the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar, a British Colony since 1713.

After touring the siege tunnels and armed caves, as well the abode of the resident Barbary apes, I wandered away from the rock itself and, being attracted to a large propeller, came upon the monument to the Second World War Polish prime minister in exile and commander-in-chief of the Polish army, General Wladyslaw Sikorsky.

Not being familiar with the incident and there not being much information at the monument itself or nearby, I made notes for myself to do an investigation upon my return home to Canada. I was further interested in that my great-great grandfather had emigrated to England in 1829 from the small village of Rösnitz (now Rozumice) in Upper Silesia, then part of East Prussia and what is now southern Poland.

In late spring 1943, Sikorsky landed to refuel at Gibraltar after an inspection and morale- boosting tour of the Polish forces on duty and stationed in the Middle East. Also, while on this tour, he was engaged in a dispute with Polish General Wladyslaw Anders regarding the normalization of PolishSoviet relations, to which General Anders strongly objected.

At 23:07 on July 4, 1943, after taking off from the North Front tarmac of Gibraltar’s airport, Sikorsky’s aircraft, a Consolidated B-24 Liberator II, serial number AL523, crashed inverted into the sea only 16 seconds after takeoff, killing the 11 passengers on board with only one survivor, the aircraft’s Czech

captain and pilot, Flight Lieutenant Eduard Prchal.

A British military Court of Inquiry convened on July 7, 1943 to investigate the crash, following orders by Royal Air Force Air Marshal Sir John Slessor on July 5, two days earlier. The court concluded that the jamming of the elevator controls, that led to the aircraft becoming uncontrollable after its takeoff, had caused the accident.

Retired KLM pilot Captain Jan Bartelski, of Polish descent and a former president of IFALPA (International Federation of Airline Pilots Associations) put forth a plausible explanation of the crash, suggesting that the incident was caused by a partially empty mailbag which was impaled between the horizontal stabilizer and the elevator, jamming the controls and preventing the aircraft

from climbing after takeoff from Gibraltar airport. Bartelski further states that in a ‘normal’ bomberconfigured Liberator, a mailbag was kept in the machine gunner’s position to protect him from the rush of air through the nose gear door. Similarly, a bag could have been in the cargo compartment on the doomed Liberator and blown out the side hatch, jamming the controls and causing the elevator to become unmovable.

The catastrophe, while officially classified as an accident, has led to much conjecture that the crash of General Sikorsky’s Liberator Bomber was caused by an assassination plot.

The theories surrounding possible and suspected attempts on General Sikorsky are legion. Likely one of the first was attributed to the German Second World War Abwehr intelligence

“There were several bodies that were not found after the crash and still others that were never identified. It is suggested that some of the passengers might have been murdered prior to takeoff and still others who might have been abducted by the Soviet Union.”

agency which suggested that the so-called accident was caused by a Soviet – British conspiracy, or even by the Poles themselves after the German Wehrmacht discovered in April 1943 the mass graves of several thousand Polish officers killed by the Soviet Army at Katyn Forest in 1940. Polish General Anders had taken great issue with Sikorsky regarding his attempts at reconciliation with the Soviets and his policy of colluding with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

Some theorists speculate on the opportunities that the Soviets had at Gibraltar. While Sikorsky’s Liberator was parked on the North Front ramp at Gibraltar airport, a Soviet aircraft that was carrying Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky was parked adjacent to the Liberator, thus confirming a Soviet presence at the accident scene. This brings conjecture regarding the actual passenger load that boarded Liberator AL523 at 23:07 at Gibraltar airport July 4, 1943.

There were several bodies that were not found after the crash and still others that were never identified. It is suggested that some of the passengers might have been murdered prior to takeoff and still others who might have been abducted by the Soviet Union. One might have been Sikorsky’s daughter Zofia Lesniowska, whose body was never found and who was later reported seen in a Soviet Gulag in 1945.

It also officially confirmed that at this time the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service Counterintelligence Agency from 1941 to 1944 for the Iberian Peninsula was none other than Kim Philby, who was a Soviet double agent since the early 1940s. Philby had also served with the British SOE (Special Operations

Executive) which specialized in sabotage and operations behind enemy lines. Philby defected to the Soviet Union in 1963.

The suspicion of sabotage was compounded by the fact that eight months before, in November 1942, Sikorsky had flown over the Atlantic to a meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He stopped in Montreal and boarded a Lockheed Hudson to complete the journey to Washington, D.C. On takeoff, both engines failed only 30 feet above ground, but the pilot was able to land safely, and Sikorsky was unhurt.

Rumours and theories respecting the crash of Sikorsky’s Liberator abound and the archives of the British Public Records Office and Special Intelligence Service archives reveal no further information. However, the General had other potential enemies, some of whom were rather surprising. Winston Churchill considered Sikorsky somewhat of an obstacle, as the British prime minister had previously agreed that after the war the Soviet Union could continue to occupy some Polish territory. Understandably, Sikorsky was furious. This whirlpool of suspicion and plotting ended in the ‘apparent’ assassination of the Polish prime minister.

The Polish official investigation ended in 2013, concluding that deliberate tampering to the aircraft could be neither confirmed nor ruled out. The United States Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles explicitly called Sikorsky’s death an ‘assassination.’

At least one person had no doubts about who was responsible for the assassination of the Polish General. Sikorsky’s widow vehemently shunned Churchill afterwards.

We all think of VFR as a way of flying when the “weather is nice.” But what if it’s not “nice”? Can it be “nice enough”?

VFR, by definition, is Visual Flight Rules, colloquially known as “see and be seen,” where the pilot must actively watch for other aircraft and adjust as needed to avoid them. This is why minimum visibility requirements are established to give pilots enough time to spot other aircraft, determine a course of action and implement that course of action to deconflict themselves from others.

Apart from the rules for right of way discussed in previous columns, there are varying requirements for minimum flight visibility depending on the classification of the airspace. Uncontrolled airspace (Class G) is as unrestricted as it gets, requiring a pilot to have only as little as one statute mile (SM) of flight visibility to allow for flight under VFR (nighttime requires three SM visibility, and there are other considerations under CAR 602.115).

As we move into controlled airspace classifications, the minimum visibility requirement for flight under VFR jumps to three SM. The purpose of the increase is to facilitate the presence of IFR aircraft, which may be operating within cloud and may punch out of cloud laterally or vertically, and which may have to transition from instrument references for flight for the pilot to be able to see VFR aircraft, and for VFR pilots to see and avoid them on what could be short notice.

This, by the way, is part of the reason there are minimum distances specified for operation near clouds both vertically and horizontally for operation under VFR. Controlled airspace, as referenced above, is airspace within which IFR flight is subject to the authority of Air Traffic Controllers. This means Class E and above. If you look at charts or read

the Designated Airspace Handbook, you can find all the definitions of various chunks of airspace in each Flight Information Region (FIR).

Most will readily know quite readily about Control Zones where airport control towers are in operation, and the busier Terminal Control Areas as being airspaces with more positive control over VFR flight. These are typically Class D and higher, but there are two types of Class E I’d like to be sure you’re aware of.

Control Area Extensions are established in areas with enough IFR traffic to facilitate control of IFR flights in enroute areas between airports at lower altitudes and has the effect of raising the minimum visibility for VFR flights in those enroute areas. They typically have the base of Class E controlled airspace starting at 2,200 AGL. Below that will be Class G unless otherwise defined, such as with a Transition Area near an airport served with Instrument Approach Procedures.

Another place where Class E airspace may be established is around airports that don’t have Control Towers in operation. Similarly, the point of this is to facilitate the control of IFR traffic, and to increase the minimum visibility for VFR flight in the immediate vicinity of said airport.

These are defined as Control Zones, which sounds silly given that they don’t have a control tower in operation, but they are named as such to remind pilots that they extend controlled airspace to the Earth’s surface within defined dimensions. Many Control Zones, Class D and higher, whose towers don’t operate 24/7 revert to Class E when the tower closes, leaving the controlled airspace in place for the aforementioned reasons.

Now, what about VFR flight in these areas if the weather is marginal, or even slightly below VFR minima? Enter Special VFR.

When the weather conditions are below VFR minima, ATC may authorize

“Special VFR may be authorized for the pilot to takeoff from or land at an aerodrome within a Control Zone, or to simply transit through a Control Zone. At night, however, the only authorization that can be issued is to permit an aircraft to land at the aerodrome.”

a VFR pilot to operate within a Control Zone surrounding an airport with as little as one SM ground visibility. A helicopter, operated at reduced speeds, may be permitted with as little, but not less than, half of that.

Special VFR may be authorized for the pilot to take-off from or land at an aerodrome within a Control Zone, or to simply transit through a Control Zone. At night, however, the only authorization that can be issued is to permit an aircraft to land at the aerodrome.

To operate under Special VFR, there are restrictions. As always, the VFR aircraft must operate clear of cloud. The pilot may not fly the length of the Control Zone skimming treetops, as there is a prescribed safety margin for those on the ground, too, just like in good weather (not less than 500 feet vertically). That said, there is no minimum ceiling requirement specified.

Which ATC facility authorizes Special VFR? The IFR ATC unit overseeing a given aerodrome does. If a Terminal Control Unit is in operation and has jurisdiction over an aerodrome, it would be the controllers there. Otherwise, it would be those in the parent Area Control Centre.

To streamline things, interunit arrangements are normally in place for controllers in Towers to give that authorization directly to VFR pilots instead of the pilot contacting the IFR ATC unit separately.

If a pilot wishes to operate under Special VFR at an aerodrome with a Control Zone served by a Flight Service Station providing Aerodrome Advisory Services (AAS), including remotely (RAAS), the Flight Service Specialist can be contacted on the Mandatory Frequency to relay the request to ATC

for approval. Some FSS have similar arrangements with ATC to authorize the pilot directly themselves, just like the Towers.

The authorization for Special VFR can be withheld on the basis of current or anticipated IFR traffic. A pilot may be asked to wait outside the CZ or on the ground until IFR traffic is no longer a factor or be asked to remain clear of certain flight paths to reduce the risk of collision. As always, if the weather is such that avoiding those flight paths is problematic, a pilot requesting Special VFR should inform the Tower, FSS or ATC of the issue.

Special VFR may be authorized for a specific operation (entering the CZ and landing, taking off and leaving the CZ), a specific time period, or for more than one aircraft. In the latter case, the pilots of each aircraft operated under Special VFR are still responsible for their own operation and separation from other aircraft.

Special VFR is not something that should be taken lightly, as the margins for error are reduced. It is for this reason that, in all cases, a pilot must initiate the request for Special VFR approval. It will not be offered by ATS (Air Traffic Services) personnel. Pilots must be aware of the weather before making such a request and do so knowingly. An area unfamiliar to a pilot can be full of hazards such as radio towers or other obstacles and terrain that may not have lights or other indications of a hazard.

Special VFR may be a useful tool for a pilot if the weather deteriorates while inbound for landing, or if a front is moving through and conditions outside the CZ are known to be improving. As long as the decision is taken with care and due caution, it can be helpful. Watch the skies and fly safely!

BY BRUCE L. CARNEGIE

Bruce Carnegie shines a light on the little-known mission of Canadian helicopter crews to support a United Nations mission in Central America. The author delivers an exciting account of some hairy missions flown in 1990 in Nicaragua and Honduras, dealing with some tough customers: the Sandinistas and the Contra Rebels. This account is his personal story of his adventures and is a book that should be on every military aviation history buff’s bookshelf. More importantly, it accurately portrays Canada’s participation in the most important event in any war, that being the slow growth of trust between belligerents preceding a peace settlement.

Hailing from Richmond, British Columbia, Carnegie became a Canadian Armed Forces pilot and deployed to Central America to fly helicopter missions at the end of the Contra War. Carnegie’s writing style is easy to read, with just enough detail to not slow down the story and sprinkled with plenty of dry humour. Early in his narrative Carnegie details how rotary wing pilots are trained in Canada, how he earned his wings in 1987 and how he became Captain with 427 Special Operations Aviation (Tactical Helicopters) Squadron, Petawawa. Most of the book details his six-month (January-July 1990) deployment to help with the disarming of the rebels of the Contra War. His many amusing and sometimes somber anecdotes relate to how he shuttles military staff around, delivers paperwork, secret documents and supplies, checks on Rebel camps, and how he and his copilot managed to fly a severely wounded UN observer to hospital, saving his life by a thread.

Loach pilots were born in the Vietnam War (1955-1975) and were a rare breed by the early 1990s. Carnegie’s first tour was flying the Bell CH-136 Kiowa helicopter

(a variant of the Bell 206A) when he was deployed to Honduras (based in Tegucigalpa) and Nicaragua in support of the Contra demobilization. The deployment was part of the UN Observer Force to facilitate a peace settlement between the Contras and the Sandinistas. The force included the UN’s 89 Rotary Wing Aviation Unit (RWAU, disbanded in late 1990) of the 10 Tactical Air Group. The nickname ‘Loach’ comes from the acronym LOH (Light Observation Helicopter) which describes the helicopter’s role.

In Vietnam, the Americans operated the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse helicopter (a variant of the Hughes 500). The Cayuse, like the Bell, is a small, manoeuvrable and fast ship designed for reconnaissance, observation, target spotting, light attack missions, support operations, teamwork with gunships (like the AH-1 Cobra) and even search and rescue. Loach pilots operated in extremely dangerous environments, as their missions required them to fly ‘low-and-slow,’ making them vulnerable to enemy fire. The skill of these pilots was crucial in high-risk situations where quick decision-making and precision flying were essential, as Carnegie relates in his own firsthand account. Loach pilots gained a certain degree of fame in popular culture, notably in the 1972-1983 television series M*A*S*H (though in the Korean War the Americans flew the Bell H-13 Sioux as medevacs) and the movie Apocalypse Now. The depiction of these pilots and their helicopters has become iconic for their bravery and the challenges of their missions.

LOH aircraft were primarily responsible for conducting aerial reconnaissance, spotting enemy positions and gathering intelligence. They often flew ahead of larger formations to locate and identify targets or potential threats. Their missions were critical in the success

A REVIEW BY RENÉ R. GADACZ

of ground operations, and they often worked closely with other units, such as infantry or attack gunship squadrons. Loach pilots needed to be highly trained in helicopter operations, navigation and combat tactics. Additionally, they required strong situational awareness to assess risks and make quick decisions under pressure. Many pilots became highly proficient in tactics like flying nap-ofthe-earth (NOE, flying very close to the ground) and conducting night operations. Carnegie describes several hair-raising missions requiring NOE flights.

The Loach pilot played a crucial role in the development of modern military aviation tactics, especially in reconnaissance and close air support. The skills honed during the Vietnam War influenced helicopter operations in later conflicts, such as the one described by Carnegie in this book, and the LOH’s success as a reconnaissance platform contributed to the future development of other military helicopters, such as the CH-139 Jet Ranger and Bell CH-135 Twin Huey used in the CAF.

Of course, Carnegie’s narrative has a context. The Contra War (1981–1990) was a conflict in Nicaragua between the American/CIA-funded and armed Contras, and the Sandinista National Liberation Front, the leftist government allied with

the Soviet Union and Cuba that came to power after the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship in 1979. It was a significant conflict in what was the last decade of the Cold War, characterized by ideological, political and military struggles influenced by American fears of communism spreading in Central America.

So why is Carnegie’s account important? Canada’s role in the Contra War was relatively limited compared to the United States, but still notable in terms of diplomacy and humanitarian aid. This was also the first time Canadian military helicopters flew in an active conflict zone, albeit near the end of the conflict, the dangers of which Carnegie recounts in suspenseful page-turning scenes.

Unlike the United States which provided direct military and financial support to the Contras, Canada avoided taking sides in the conflict. While not a major player in the conflict, and though placed between two warring parties, Canada’s role in advocating for peaceful resolution and providing humanitarian support left a lasting impact on its relationship with Central America, especially Nicaragua. Canadian development aid continued to flow to Nicaragua during the Sandinista era, reflecting Canada’s policy of supporting development regardless of political ideology.

Since his UN/Canada deployment, Bruce Carnegie served various squadrons as flight instructor, executive assistant to a Wing Commander, held the position of Maritime Patrol Crew Commander and was promoted to the rank of Major, among other military duties. After 21 years of military aviation service and a 33-year flying career, he retired in 2011. He wrote Loach Pilot because “I have seen a lot of weird stuff… and I have a plethora of fond memories.” The 427 Squadron biography page states that he is currently an Airbus 320 captain based in Vancouver.

Loach Pilot: Disarming the Contra War

By

Bruce L. Carnegie

Loach Pilot Aviation Incorporated, 2018, 270 pp.

Available from The Aviator’s Bookshelf (aviatorsbookshelf.ca)

It was the perfect September morning in Alberta’s foothills — calm winds, blue skies and temperatures forecast to hit the high 20s. An early morning departure would help mitigate the usual density altitude concerns pilots flying from airports situated at the foot of the Rocky Mountains often deal with. As an added bonus for our early launch, we would hopefully be rewarded with smooth flight conditions; “good rides” in airline parlance.

My student had already preflighted the Aztec at High River airport when I boarded the airplane and readied for engine start. The plan was a 1.5-hour mission to nearby Springbank airport to practice some ILS approaches. With both engines now idling and run-up complete, Damian released the parking brake and called, “Brakes check, you have control.” At idle power and with only 100 U.S. gallons and the two of us on board, the old bird rolled forward

easily, and I responded, “Brakes check, you have control.”

We hadn’t moved five feet when suddenly a white, acrid smoke began pouring into the cockpit. This wasn’t the smell we all recognize when previously cool avionics get a little warm. No, this was something far more daunting. Without further thought, I called out, “Stop the airplane and shut the engines down — NOW.” To his credit, my newbie multi-IFR student did just that. Next came the words I’d recited in emergency drills literally thousands of times at Air Canada, but never dreamed I’d have to put into action. “EVACUATE!”

By now, about 15 seconds had passed since the smoke first appeared, and it was obvious that a full-on fire was raging somewhere in the Aztec’s front end. For once, being seated in the right seat was a bonus. I don’t remember removing my shoulder straps, but do remember unlocking, then unlatching, the right-side

cockpit door before literally slamming it open. I also recall hoping that I hadn’t damaged the door catch mounted on the inside of the right engine cowling. (Such is the pilot mindset: even in an emergency situation, don’t hurt the airplane!).

With the props now at a dead stop, we scrambled out of the airplane, evacuating aft and right. Now safely clear, I turned to look at the cabin. The Aztec was fully engulfed in white smoke that was pouring out of the partially open cabin door. About 45 seconds had passed since we first detected the fire.

Showing great situational awareness, my student dialed 911, telling the operator, “An airplane is on fire at the Foothills Regional Airport.” He had clearly remembered my lesson about taking an emergency to its logical conclusion.

About the same time Brad and the crew from High River Airmotive arrived on scene, fire extinguishers in hand and ready to go. But by then the fire had al-

ready penetrated the fuselage at the nose cone, and there was no stopping it. We all stood and watched the smoke change from white to grey, then to black, as the fire worsened. All we could really do was to stay clear and wait for the Foothills County Fire Department to arrive. By the time the first responders arrived on scene, their mission was mostly controlling the fire, as there was clearly no hope of the airplane ever flying again. When the forward fuselage literally broke in two aft of the nose gear, the airplane fell onto what remained of its nose. A new threat now emerged as avgas began pouring from the leading edge of the left wing. The firemen immediately responded to this unexpected danger, and the nearly 400 litres of fuel still in the wings was later recovered.

As for the fire, the lesson learned that day is that while flames are bad, what will undoubtedly get you first is a combination of smoke and fumes. Had we not evacuated when we did, I estimate we had another 15 seconds max before succumbing to the combined toxic mess that was being fuelled by the burning interior. Yes, it truly was that bad. The fire was likely initially electrical in nature, but once it got going, anything that could burn supported combustion.

As sad as I was at the loss of the school’s Aztec, I’m ashamed to say I was equally perturbed at the loss of my flight bag, Canadian passport, Aviation Document Booklet, Nexus card, an original radio licence, and my U.S Pilot’s Certificate. Add to that a new iPad Mini and my Bose headset, both birthday gifts from my wife Karen. Then I quickly remembered that only a few minutes before I’d been thankful for us just getting out of the burning Piper alive.

I will continue to teach pilots to take emergencies to their logical conclusion and will now add this particular event to my repertoire. In the category of emergency briefings in GA aircraft, I encourage you to consider briefing your passenger — just as the airlines do, in their actions in the event of an emergency, be it opening a door or helping a fellow passenger egress.

When everything had settled down,

I went back to look at what remained of the classic Piper and to say a final goodbye. Even in her sunset years, the sweet old gal had helped train a new generation of pilots who, in the course of their careers, will likely never have the opportunity to fly the venerable PA-23250 again. How times have changed.

On the rare chance that something might have survived the fire, I grabbed a 2 x 6 board from the box of my pickup and started digging through the incinerated debris in what was once the second row of the Piper twin.

The destruction was disturbing to see, a truly horrible end for what, in the year 1969, was once someone’s pride and joy.