WOP MAY’S MERCY FLIGHT

PEI’S CABLE HEAD AIRPARK

DEPARTMENTS

50

FEATURES ON THE COVER

Phoenix Aviation’s Airbus H130 (EC 130) together with their Diamond DA-62 near Fort McMurray, Alberta. See page 30 for story. Photo by Greg Halinda

Robert S. Grant

50

Phoenix Aviation’s Airbus H130 (EC 130) together with their Diamond DA-62 near Fort McMurray, Alberta. See page 30 for story. Photo by Greg Halinda

Robert S. Grant

Canada has a rich and proud aviation history — from the pioneering bush pilots who connected remote northern communities, to world-class aerospace innovation and training. Supporting a Canadian aviation print magazine helps preserve and celebrate this legacy while fostering future growth and awareness within the industry.

First, print aviation magazines offer indepth stories and historical features that digital formats often fail to match. They provide an immersive experience, encouraging readers to slow down and engage with content in a more meaningful way. For aviation enthusiasts, professionals and hobbyists, print remains a valuable resource for learning and inspiration.

Second, a Canadian-focused aviation magazine ensures that our unique

perspectives and achievements are not overshadowed by international narratives. It highlights Canadian pilots, aircraft, companies and events — stories that might not otherwise receive attention in American or other global publications.

Moreover, supporting such a publication strengthens the national aviation community. It connects readers from coast to coast to coast, showcasing regional events, airshows and aviation schools. This fosters pride and promotes networking opportunities across the country.

Finally, in an age of shrinking newsrooms and growing media monopolies, independent print magazines face immense challenges. Supporting a Canadian aviation magazine means supporting Canadian journalism,

storytelling and specialized knowledge. It’s an investment in an informed and inspired aviation community.

Whether you’re a pilot, engineer, student, or simply a fan of aviation, backing a homegrown aviation publication helps keep our skies — and our stories — alive and thriving.

And we need your help. I urge all our current subscribers to gift a oneyear subscription to Canadian Aviator magazine to a family member, friend or acquaintance with an interest in aviation. Use this code for a 50-percent discount off the regular price*: D5AAAAAA. New subscribers are entitled to this special promotion too. See the masthead opposite for subscription contacts. Valid until August 31, 2025.

*Valid for new subscriptions only.

I have just read "True Patriot Love" in your Airmail section of the May/ Jun 2025 issue. I want to congratulate David Dickens of Monterey, Calif. for his excellent taste in aircraft. I, too, with a fellow pilot, owned a 1965 (or was it a 1962?) Cessna 150 based in Saint John, New Brunswick. That was back in 1984 to 1988. I loved flying that little bird and treated many friends and family to joy rides in it. Many parts of New Brunswick passed under my wings, as did the Bay of Fundy while crossing over to Nova Scotia and the Northumberland Straight, as I eagerly crossed over to Prince Edward Island for a totally different landscape view.

Since then, I have been a dedicated hangar flyer, and Canadian Aviator keeps me on course.

Harold McKinnon, Quispamsis, N.B.

Just to mention that in the latest issue of Canadian Aviator (May/Jun 2025), Graeme Peppler’s Pep Talk article titled “Aviation Miracles” mentions that Lausanne, France is where the Fédération Internationale de l’Aéronautique is based. Lausanne is located in Switzerland (or Suisse for us French-speaking people). Lausanne is also the headquarters for the Comité International Olympique.

Always interesting to read the magazine from beginning to end.

André Charbonneau, Mont-Tremblant, Qué.

Lausanne is of course in Switzerland. France was accidentally inserted during the editing stage. This editor should know this geographical fact, having once visited the beautiful city on the shores of Lake Geneva (known as Lac Léman in French). – Ed.

In August of 1971 I was a member of the RCMP and transferred from Gold River, British Columbia to Sidney, B.C. In September I started flying lessons towards obtaining a commercial pilot licence. I was looking for a flight instructor and someone recommended Rick. I can still remember to this day when I first met Rick across from the B.C. Government Air Services Hangar at the Victoria Airport. At the time I arrived in Sidney, I did not know that Rick Cockburn had flown his Harvard in the London to Victoria Air Race.

That September I started my flying lessons towards the CPL and Rick was my instructor. We became great friends during this time. He took me up in his Harvard and demonstrated rolls and other aerobatic manoeuvres. It was during this time that he told me all about his adventures flying in the air race and the finish over Race Rocks in Victoria.

In 1973 I was accepted into the RCMP’s Air Division flying all over Canada, including the Canadian North. I retired after 33 years and flew overseas until I turned 65. Rick and I have remained friends until this day.

I also want to say how much I enjoy reading every issue of Canadian Aviator. There isn’t an issue that I don’t read about someone I know or stories about places I have flown.

Garry McIver Kamloops, B.C.

Send us your letters. Canadian Aviator welcomes reader letters on topics of concern to Canadian pilots and the aviation industry. Please be brief, to the point and polite in your submissions. Email Steve Drinkwater steve@canadianaviator.com

Ever lose a GPS signal on your device while in the cockpit? Want something that is more accurate and dependable than the GPS feature of your iPhone or iPad? Garmin offers a remote antenna, the GLO-2, that captures not only the U.S. military’s GPS signals, but also the Russian GLONASS signals, offering redundancy, especially in this era of undependability of our supposed ally to the south. The GLO-2 links to as many as four different devices via Bluetooth and updates itself up to 10 times faster than the GPS feature found in most smartphones and tablets. Battery will stay charged for up to 13 hours, and it comes with a USB charging cable. About C$180. Learn more at, and available from, garmin.com

Do you want others to be able to track your flight’s progress on a map? Would you like to know your wheels-up and wheels-down time precisely? Would you like to receive

maintenance reminders when they come due? All these features, and many more, are available through Airbly of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. The Phoenix Aircraft Monitor is a small, black box that measures about 94 x 94 x 28 mm (3.7 x 3.7 x 1.1 in.) that sits on your aircraft’s glareshield and communicates via satellites. Ideal for aircraft fleet operations.

About C$429. Reporting services start from C$99/year. Learn more at, and available from, airbly.com

From the makers of the XGPS150A Universal GPS Receiver comes the XHUD1000 Head Up Display. Designed especially for light, general aviation aircraft, the XHUD can display one of three selectable modes: AHRS, which displays altitude, airspeed, attitude, bank angle and compass heading; Traffic, which displays ADS-B traffic on a radar style graphic with selectable range, using TCAS symbology; and Tablet Graphics, which displays graphics from separate apps running on a tablet or smartphone (e.g. AHRS, synthetic vision, maps). It is compatible with both iOS and Android devices, using Wi-Fi and Bluetooth technology. It is compatible with Foreflight and other Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs). About C$860.

Learn more at dualav.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

Father’s Day may have passed already, but you don’t need that excuse to pass up the opportunity to gift the aviator in your family with a pair of socks sporting an aviation theme. Perhaps a stocking stuffer come Christmas? The socks are of a polyester and Spandex blend and are machine washable. One size fits all. About C$5.50. Learn more at, and available from, temu.com/ca

As Remotely Piloted Aerial Systems (RPASs) — often referred simply as drones — continue to proliferate, more and more responsibility lies with the drone operator to conduct operations in a safe manner, particularly with respect to more conventional aircraft that may be operating in the same airspace. While helicopter operations come to mind, the fact that light airplanes and ultralights are legally permitted to fly as low as 500 feet above ground level (agl), or 1,000 feet agl in built-up areas, they also have the potential to come into conflict.

uAvionix, the market-disrupting American company that brought low-cost ADS-B solutions for light aircraft, has introduced a new product to aid drone operators by alerting them to other aircraft that are close to the drone operations area.

Meant as a wearable device for the RPIC (Remote Pilot In Command) or an associated observer, skyAlert will provide a real-time audible and visual alert when an ADS-B Out signal-emitting aircraft enters a zone that the drone operator defines. That zone can be set for range and altitude limits. Both 978 MHz and 1090 MHz frequencies are detected.

Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) such as Foreflight, FlyQ, SkyMap and many others are supported through industry-standard GDL-90 protocols.

This device only works when approaching aircraft are transmitting an ADS-B signal. Although there is still no mandate for ADS-B Out in Canada for operations in Class C, D and E airspace, the adoption rate for the installation of ADS-B equipment in light aircraft is nevertheless relatively high given the enhanced flight safety it provides.

uAvionix was founded in 2015, initially to develop miniature avionics systems for drones, hence its name uAvionics, the uAv being the acronym for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, another name for drones. In 2022, the company was sold to DC Capital Partners LLC.

STRUCTURES TECHNICIANS

Northern Alberta’s Portage College has announced a new certificate program that will train students in Aircraft Structures. Graduates will be able to gain entrylevel employment leading to a career as an Aircraft Maintenance Engineer - Structures (AME-S). The program is set to begin next year and will be based at the Cold Lake Regional Airport (CEN5). Portage College’s aim is to provide trained technicians to serve in civilian roles not only at nearby CFB Cold Lake (home to 4 Wing, the RCAF’s largest fighter aircraft wing), but elsewhere in the country.

In partnership with Portage College, the City of Cold Lake has purchased a hangar at their regional airport and is converting it into a state-of-the-art training facility.

“This hangar will house the first iteration of the Cold Lake Aircraft Maintenance Engineering School, which would be a big win for our community and our partner, Portage College,” said Mayor Craig Copeland. “With the aerospace and defence industry operating in our community and a strong relationship with 4 Wing over the past 70 years, there are many potential partnerships we can leverage as this project takes shape.”

The city has set aside additional adjacent land to allow for expansion of the facility should the college expand its aerospace-related offerings to include aircraft maintenance,

engineering, and perhaps flight training. Portage College plans to eventually offer a full program.

“At Portage College, we are thrilled to partner with the City of Cold Lake on expanding into the aerospace sector,” said Nancy Broadbent, president and CEO of Portage College. “The establishment of the Aircraft Maintenance Engineering program marks a significant milestone for both our institution and the community.” The program has also received official endorsement from the Minister of Defence.

The Aircraft Structures Technician program will be broken down into seven modules:

• Introduction To Aviation Structures

• Metal Aircraft Construction 1

• Metal Aircraft Construction 2

• Special Processes/Practices

• Composite Fabrication/Repair

• Damage Assessment/Repair 1

• Damage Assessment/Repair 2

The college will begin student intakes in October of 2025, with first classes beginning in August 2026.

Portage College’s main campus and headquarters is in Lac La Biche, Alberta and it has several other campuses spread around Northern Alberta communities, including several First Nations.

There is likely no Canadian who has not heard of the de Havilland Beaver, given its iconic status in Canadian culture. Most would be forgiven, however, if they assumed it was the first Canadian-designed bushplane. For it was not.

In 1935 Dutchman Robert Bernard Cornelius “Bob” Noorduyn designed the Norseman to fulfill a Canadian-defined mission: A heavy load-hauling, single-engine high wing monoplane to facilitate float operations and the easy loading of passenger and cargo on airport ramps. First flight was on November 14, 1935.

The design proved to be popular, and many served in both the RCAF and in U.S. military forces during the Second World War. In fact, it was the first Canadian-designed aircraft to serve with U.S. forces. Six iterations were built over a 25-year production span, totalling over 900 airplanes. Initially they were produced by

Montreal-based Noorduyn Aircraft Ltd., later by Canadian Car and Foundry, also of Montreal.

The first Norseman, powered by a Wright R-975-ES Whirlwind radial engine, was sold to Dominion Airways and registered as CF-AYO. During the summer of 1941, American film production company Warner Brothers leased it for a starring role alongside James Cagney in Captain of the Clouds, with filming done around North Bay Ontario. CF-AYO met its demise in Algonquin Park in 1952, and its wreckage is on display at the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

A trivial, but nonetheless interesting fact about the Norseman: It was first designed with floats. Later iterations were fitted with skis before finally evolving into a landplane on wheels.

SHOULD FLOCK TOGETHER – OR SO I THOUGHT

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore — Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

— Edgar Allen Poe

Iwalked down to the dock at about seven one morning. I had a flight pre-arranged to take off at eight o’clock with six passengers to three destinations. About 40 minutes of flying time would be involved. The Beaver’s floats needed pumping, the oil checked, and fuel added. I was giving myself an hour to do these tasks and, with any luck, would have enough time left over to check the phone recordings for other bookings called in during the night.

The walk from the house had taken a pleasant 10 minutes. The North Island weather does not promise the kind of morning that was now greeting me. It was a delightful dawning with no rain for a change, nor any feel of a Nimpkish blowing out of the valley of the same name behind the townsite; it was a soft quiet morning.

Then suddenly, the raven that lived on the balustrade over the entrance to the ramp let out a loud screech and flew at me as if to attack. This wasn’t just a scolding like most mornings, but a statement of ownership by what I had thought earlier to be a bird who acknowledged our mutual domicile and place of work. We had been living in peace together, each conducting our flights from the seaplane dock here at Port McNeil.

Our seeming affinity, each as aviators, one with feathers the other with

less airworthy materials, was now in question. I ducked from his advancing dive, which turned out to be a feint and ended with a clever bird-only type roll off the top as he regained his footing on the crossmember above. I viewed a hostile glint from the black eye in that head that was now cocked in a fashion as if to favour hearing from only one ear.

I felt, rather than viewed, the bird’s unwavering hostility following me down the dock to the moored seaplane. I determined immediately the reason

for this unexpected hostility: The last bilging port on the Beaver’s dockside pontoon was missing its stopper — one of those happy little red, white and blue rubber balls used in the child’s game of Jacks that seaplane pilots found to fit so conveniently snug would now be a prized item of theft in a raven’s nest.

As I cut one of the other balls in half and shared it with the empty port, I could not resist the temptation and stated loudly for the bird to hear, “Thus spake the Raven Nevermore.”

The Kremlin felt a strong need to impress the world with its flight capabilities, especially the Germans and Japanese, whose sabre-rattling was becoming an increasing concern. In 1935 a decision was made to attempt a non-stop flight from Moscow to the western United States. However, the only aircraft available was the ANT25 whose range was only 1,900 miles, a lot less than required for the proposed 5,674-mile flight.

In 1929, Russia had successfully made a flight to the U.S. with a Russianbuilt Junkers K 37, but stops were made in Siberia, the Aleutians and in Alaska before its arrival in Vancouver, Washington, across the river from Portland, Oregon. The Soviets therefore consulted with that crew to determine what possibilities were available for the planned 1937 flight.

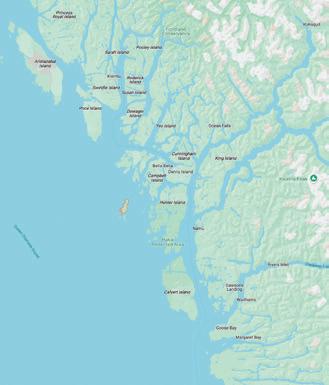

At this time Stalin ordered Sigismund Levanevsky to proceed to the U.S. and take delivery of a float-equipped Vultee aircraft and fly it back to Russia via the British Columbia coast, Alaska and Siberia. On this August 8, 1936 flight, Levanevsky stopped for two days at uninhabited Goose Island, 25 miles southwest of Bella Bella, B.C.

Stalin had also decreed that Valery Chkalov would pilot the June 1937 nonstop flight, and not Levanevsky as previously planned, likely because he was born in Poland and Stalin wanted this record-setting flight to be made by a Russian.

After consultation with the North Sea Route administration (NSR) and Tupolev, the Kremlin made a decision that, even though the nonstop flight was not possible, the use of deception would allow the appearance of the nonstop flight. Previously, on July 13, 1935, an official request for the flight had been made for the ANT-25 to land in the U.S. Stalin, either directly or

through his embassy in Washington, D.C., requested logistical and moral support in his clandestine endeavour.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was president from 1933 to 1945. He was no fool and could see the value of supporting Stalin’s regime as a buffer to the militaristic threats of Adolf Hitler.

FDR also had a staunch ally in William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had been educated at Harvard University and the University of Toronto, and whose mother was an American. Member of Parliament King was swept from office in 1911, and he later returned to the U.S. where he was retained as a

“... Stalin ordered Sigismund Levanevsky to proceed to the U.S. and take delivery of a floatequipped Vultee aircraft and fly it back to Russia via the British Columbia coast, Alaska and Siberia.”

consultant by John Rockefeller, Jr., who allowed him to continue his work with the Liberals in Ottawa while working with Rockefeller’s interests in the U.S. King first became prime minister in 1921 and again from 1935 until 1945. Prior to taking his position, he had discussions with American academic and businessman Clarence Decatur (C.D.) Howe, who agreed to stand for Canadian office and, after his election in 1935, became Minister of Transportation.

So we can see that, when in 1936 FDR made a simple request to his Canadian counterpart for the government of Canada to turn a blind eye to the Soviet’s use of an uninhabited island off the West Coast to refuel an

aircraft that was supposedly making a “nonstop” flight from Moscow to Vancouver, Washington, it would not be a problem, especially since FDR was to monitor the situation by providing onsite assistance to ensure the secrecy of the project. FDR, John Rockefeller Jr. and American big business were calling in some of their markers.

In a very short time, the U.S would be providing $32 billion in “lendlease” aid to the Soviet Union. The manufacturing giants of America were destined to make huge profits, regardless of whether the Russians paid off the debt or not.

FDR was responsible for the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, during the Great Depression

to provide paid work for unemployed young men. In 1937, a number of these men, who were Native Americans from Alaska and Washington state, were recruited to proceed via a government vessel and assist in the refuelling of an aircraft at an unidentified West Coast location. Frank Eyle, from Charter Oaks, Washington, was a member of the group who later described the project as the best job he ever had.

On Monday, June 14, 1937, in Seattle, Soviet agent Vartanian had made radio contact in code with the group at Goose Island and advised them to expect a message on June 17 concerning the arrival of the ANT-25.

To be continued...

What an amazing world we live in when it comes to technology. The power packed into small devices these days was only in the imagination a few decades ago. Now it’s taken for granted by most of us. Those of us who have been in the industry for a while have watched a variety of technologies, probably most notably GPS, take a couple of decades to take root and grow. Thirty years ago, acceptance of GPS for IFR navigation was in its infancy. These days, very few airplanes fly without it.

Back then, aircraft snaked across the sky in crooked routes using ground-based NAVAIDs for guidance. Conflicting aircraft were commonly vectored around each other by controllers where radar coverage existed. All of this required a controller’s attention to ensure separation. These days, aircraft capable of accurate point-to-point navigation can reduce controllers’ workloads by flying routes that keep them separated. Sometimes ATCinitiated shortcuts can solve conflicts requiring minimal monitoring.

In the old days, a pilot might choose a route by looking at a map and seeing items like restricted or danger areas that should be avoided. Most flight planning utilities don’t have algorithms or databases to recognize these areas and plan around them. Interestingly, the software often chooses routes arbitrarily with waypoints, and it often leads to some surprising route descriptions. They often resemble the time-honoured, traditional zig-zag paths.

spell waypoints correctly to ensure the correct course.

These Mandatory Routes come in many forms. Some are strictly for departing one airport and landing at another. Others are departure routes to get you out of one airport to a point where the pilot is free to choose the rest of the route. Similarly, other routes are for arrivals within a particular region, where the route to get there is not published, but effective for when the aircraft is approaching the destination.

As good as this technology is, there are downsides to all of this that must be kept in mind.

Probably the most prominent issue from an ATC viewpoint is related to flight planning. Aircraft are capable of direct routes over long distances, and now flight planning software and websites have advanced to amazing capacity. One trouble with this is that pilots often allow the software to pick a route without scrutinizing what was chosen.

ATC facilities publish routes for IFR pilots to file to help the flow of air traffic. These are called “Mandatory Routes” and are found in the planning section of the Canada Flight Supplement. They exist for a reason. Some pilots simply file direct, and let ATC reroute them if necessary. This lazy flight planning results in increased workload for controllers, and “heads down” time in the cockpit, as the controllers must issue clearances on new routings. Entering a new route can take time and care must be taken to

Arrival routes often include Standard Terminal Arrival Routes (STARs), but not all airports that have Mandatory Routes have published STARs. Case in point, the Saint John, New Brunswick airport has restricted airspace merely 14 nm northwest, and there are routes published for approaching from various directions to aid a pilot in flight planning around that airspace, rather than filing direct and going through it. While these routes are normally established for IFR flights, VFR pilots may consider them as guidance, as well, since they may be published for effective use of airspace and for safety considerations. It is fairly common to see a departure out of an airport file fixes associated with STARs, using them as enroute waypoints. Also, arrivals using fixes published as departure routes occur. With a little thought, one can see why this might not work well. Almost invariably, these aircraft end up getting rerouted due to opposite direction

“As with every piece of technology, we must remember there are traps that are often easy to fall into. If you’re not aware of how the technology works and what its limitations are, you may be taken by surprise.”

traffic. Another reason to look for a Mandatory Route.

Many of the flight planning websites have another issue. One pilot files a route, and whether it’s an acceptable route traffic-wise doesn’t matter. As long as there are no spelling errors in the fix names, the site saves it for recommendation to other pilots who use the same software for the same airport pairing. This, in effect, propagates the offending route and then it becomes self-validating. “Look how many pilots file flight plans with this route.”

With all those pitfalls in mind, I’ve watched GPS go from being barely accepted to being mainstream navigation. Something once used questionably for aircraft navigation has now become part of every aspect of flying, from departure and enroute navigation to flying high-precision and high-efficiency instrument approaches. Instrument approach procedures can be established even at smaller, remote airfields where ground-based technology is difficult to install and costly to maintain.

As with every piece of technology, we must remember there are traps that are often easy to fall into. If you’re not aware of how the technology works and what its limitations are, you may be taken by surprise. Understanding how it should be used, and the effects of using it improperly, can make all the difference to flight safety.

Like the Calgary-Edmonton rivalry, there is a lesser-known strife in aviation: pilots and mechanics. While the conflict doesn’t necessarily exist to the same degree at all companies, I’m fairly certain it’s a universal relationship — or lack thereof.

Most AMEs will “bag on” pilots for writing lazy snags, refusing to fly a perfectly safe airplane, and nitpicking problems that are likely due to “finger issues”. Meanwhile, pilots will scoff over a mechanic’s vague rectification (“ground-tested serviceable” or “unable to duplicate”), the spite or mockery involved in persistent troubleshooting, and their promptness to jump for an MEL (Minimum Equipment List).

Somewhere in the middle, where it’s hazy and grey and constantly overcast, is the ominous land that belongs to the pilot-mechanics, or mechanic-pilots, depending on which profession they associate themselves with first. These confused folk (I would know, I’m one of them) don’t really belong to one specific side of the battle.

Instead, we sit in dark hangars with grease on our hands and swear we won’t be the type of pilot that wrote up whatever is giving us a headache in that moment. And then we find ourselves on the ramp during a preflight walk-around cussing about whichever mechanic signed the very bald tire as serviceable.

Occasionally, the dewpoint is at the exact right temperature, and the pressure in the oleo is perfect, and maybe

the moon is in a specific phase, so all the pilots and all the mechanics end up sharing a beer together. Those moments are exhilarating and stressful because we can simultaneously joke with everyone and offend everyone at the exact same time.

As a pilot, I’ve flown some questionable airplanes. I’ve experienced stuck brakes and jammed flaps and crosswinds in a small trainer that made my knees shake when my feet touch solid ground. Every time I take off, I have the utmost faith in my engineer that the plane they’ve certified is going to bring me home safely. I would never second-guess another pilot’s decision for not flying.

As a mechanic, I’ve witnessed a plane with physical holes in the leading edge fly as required. I’ve taken apart a propeller hub that has too-few ball bearings and damaged seals and cracked flanges, that still ran like a dream. I’ve seen first-hand what these planes are capable of, and I’ve watched them deliver despite the worst circumstances. Yet I would absolutely never hand over a plane that I wasn’t 100 percent confident in.

At the end of the day, both pilots and mechanics will call home to say they’re going to be late, delayed due to maintenance. None of us are happy about it, we all want the plane to take off on time and land as scheduled.

Aerial firefighting, I found, was one of the few places where pilots and mechanics (typically) got along seamlessly. There was no “my plane” vs “your plane,” no petty complaints and no blame game. We were a team,

“Every time I take off, I have the utmost faith in my engineer that the plane they’ve certified is going to bring me home safely.”

away from home base with nobody but each other, doing our absolute best to benefit everyone.

Whenever anyone asks if I recommend aerial firefighting, I always say absolutely. But then I recount a nightmare shift because it is not for the weak.

You begin your day at 08:00 with a blaring alarm (that will leave you with the resemblance of PTSD years later) alerting of a dispatch. You help the pilots ready the planes — chocks, covers, tie downs — and then you see five of the six of them take off. The last one is having oil temperature problems, so as soon as the responding planes disappear you grab your tools and get to work. The planes return a few hours later while you’re elbow-deep in the engine and you must tend to them, assisting with refuelling, completing a walkaround and performing quick maintenance — a burnt-out bulb, perhaps a quick tire change. Then engines start, you wave goodbye, and back to the broken plane you go.

You scarf down a quick lunch with dirty hands and get the oil cooler removed just as the planes are coming back again. The cycle repeats until the sun begins to set and they must land for the night. One returns with a flutter in the flight controls, another that isn’t making rated power, and one pilot mentions — although not urgent, he insists — that his air conditioning isn’t working. You worked all day in the blistering sun which you know means his cockpit is hotter, so it’s absolutely a priority even though he promises he’s okay. Thankful for the cool breeze the night brings, you don your headlamp and divide the work with your other

mechanic, each tackling a plane. It’s after midnight before all the planes are serviceable, with fresh foam, clean windscreens and no snags in the book. Now it’s time for engine runs. You return the broken plane to service at three in the morning, pack up all your tools, drive home and collapse into bed.

Four hours later, you get a dispatch, and you do it all over. At least you’re not beginning the day with a broken

plane this time, you remind yourself. But aviation loves a good jinx and when the planes return for a refuel, one pilot reports a leaking tank. You grab your tools and, more importantly, your caffeine and get to work, the cruel reminder that, at the end of the day, at least the pilots get to go home. You then consider a career change, that maybe you should be a pilot-mechanic instead of a mechanic-pilot after all.

NORTHERN ADVENTURES WITH MICHAEL BELLAMY

Helicopters demand an attentive pilot, someone who is mechanically intuitive when sorting through signals the engine or the flight controls are sharing. The indications can be subtle, like a new vibration, or a temperature or a pressure needle a width from where it normally resides. Those habits gradually become ingrained to where the slightest change will grab your attention.

Jodie Granley, Chief Pilot for the Edmonton Police Service, recently related an incident where a caution light started flashing, indicating that the Ni-Cad battery on her Hughes 500 was “over-temping.” Anyone familiar with nickel-cadmium batteries knows just how prone they are to overheating, including the possibility for them to catch fire or even explode. Her immediate action was to shut off the master switch. She then changed course, heading for a braided river course a few miles away. Granley reached to the floor just ahead of her seat, opening the battery access door. The battery was indeed hot.

Landing on a gravel bar, she rolled the throttle to idle but kept the engine running. Wearing gloves, she disconnected the battery, then carefully lifted it out and carried it to the water’s edge. Partially immersing the battery in the cold water, she returned to the machine and patiently waited for it to cool. Once done, Granley reinstalled the battery and flew back to base. What impressed me about Granley was the logic of her actions. I’ve heard of other circumstances where pilots simply landed, shut the machine down, vacated the helicopter and waited for help. Not Granley. Once she landed back at base, she sought out the engineer to nonchalantly report what had happened with the hope a new battery could be installed before her next trip.

Leaving Fort McMurray, Alberta early one Sunday morning, I had a ‘hung start’ with the Allison C20B engine in an Alberta Forestry Bell 206 Jet Ranger, meaning the N1, or compressor, during the start sequence refused to accelerate fully into the idle range. Twisting the throttle above the detent, I managed to encourage it and completed the start. I didn’t have passengers but was heavy with fuel and cargo.

I continued with the warmup and preflight, all appearing normal. Advancing to flight idle, I decided to go. “Good morning, Tower. Fox Sierra Alpha is ready for departure northbound.” Tower came back with the clearance, and I pulled up into a hover. A quick instrument scan — all normal — and I accelerated to 80 knots in the climb.

At 400 feet I felt the machine twitch, which instantly brought me back to the gauges. N1 (compressor) indicator was hunting a bit, which pulled me over to the TOT (turbine outlet temperature)

to see that it was following. Another abrupt yaw with needles splitting even further, I dumped the collective — panel caution lights were flashing.

I keyed the mike with, “Tower, it’s F-S-A, I’ve lost my engine.” Looking ahead, there was a rough field alongside the highway. The engine continued to surge violently as I tried to control the yaw with pedals. I rolled the throttle off. With an open stretch with deep grass ahead, I ignored the panel as I judged the flare — I’d have to run it on. We slid onto the long grass, but hidden just ahead was a shallow ditch. I locked the cyclic into a firm grip as I had visions of skidding into that ditch where the blades would take the tail boom off.

We came to a stop nose-down, and the machine rocked on the uneven ground. Silence! Switches ‘Off’, I popped the door open. Across the narrow field there was a parking lot for what looked like a hardware store. A couple of men were standing at the door curiously looking at me. I swung

my knees back inside and turned the master back on. The radio came to life with tower “F-S-A, its tower — say again?” Once I responded affirming my safety and location, I walked around the machine. All appeared okay. No visible damage. Giving the tail rotor a turn backwards, there was an ominous metallic noise coming from the engine.

A few minutes later, the RCMP arrived and, with their help and with rope from the cruiser, we pulled the 206 back a bit to where it was not so precarious. From then on, highway traffic lost interest. The officer asked for a written explanation, and I wrote, “Shortly after takeoff, a mechanical problem was experienced. I landed to investigate and decided not to continue the flight.”

The next day, Barry Cornfield the engineer arrived with another engine and soon I was back on the job. Investigation showed that a main bearing in the compressor section had failed. That compressor wheel now sits on my desk as a paperweight.

Another close encounter with a 206 occurred when delivering engineers to a large gas compressor station in northern Alberta. The winds were strong and gusting. I elected to fly directly to the helipad in a slow, descending approach over the maze of white gas piping. Once on the pad and the collective down, my passengers opened the doors and, gathering tools, headed towards the maintenance shed.

Something was wrong. The engine was still at flight idle, but the engine

was spooling down well below the ground idle speed. I gripped the throttle, ensuring that it was still wide open, but the engine was slowly decelerating. There appeared to be a white mist coming from the side of the engine cowling. I tightened the controls and stepped out to open the cowling. Jet-B fuel was spraying everywhere in the engine bay. I didn’t waste any time, shutting down the engine and, once secure, I went back to investigate. The Fuel Control Unit intake pipe had a broken flange on the ‘B nut’, which luckily happened just as I landed. I looked at the myriad white gas pipes that I had just flown over, visualizing the explosion I would have caused had I crashed into them. My angel was certainly with me.

AEROBATICS WITH LUKE PENNER

YES, IT’S POSSIBLE WHEN SEATED IN A COCKPIT!

In a previous column, I briefly alluded to a setback I encountered during last year’s training season — a physical injury that forced me to reevaluate how I approached preparation, recovery and risk in competitive aerobatics. This article is the story behind that moment, and the lessons I took from it as I prepare for what might be the most ambitious season of my flying life.

In the months leading up to the 2024 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships, I was pushing hard to fine-tune my Unlimited-level figures. One particular challenge had been gnawing at me: the vertically ascending negative snap roll. More specifically, a left-rotating snap roll on a vertical upline, initiated with right rudder — opposite the foot I’m used to using for that kind of figure. For whatever reason, these negative snaps in the vertical plane have always been profoundly disorienting for me.

Despite flying aerobatics for years at a high level, I couldn’t seem to wrap my head — or my muscle memory — around how to make this specific figure work cleanly and consistently. The snap would either break unevenly, or the airplane would yaw and tumble in ways I didn’t intend. I knew I needed to master it if I wanted to be competitive at Unlimited, so I committed to months of focused practice.

Eventually, I started to get it. The breakthrough came after relentless repetition, review of onboard footage, and careful attention to energy management and control inputs. But in the runup to Nationals, time was scarce. The Unlimited catalogue is so vast that you can only allocate so much bandwidth to a single figure. I moved on, trained the rest of the catalogue, and left the “other direction” snap for another time.

That “another time” arrived last year when I decided I needed to become ambidextrous in snap rolls, particularly on vertical uplines. I went up to practice

the right-foot, left-rotating, vertical negative snap, but I made a critical error: I didn’t fully commit. I hesitated during the initiation, never reached a proper accelerated stall, and then applied rudder anyway (all of this happens in a fraction of a second). The airplane jolted into an awkward, violent motion and, in the process, I hurt my back.

What followed was massage therapy, chiropractic work, stretching and grit — trying to stay in competition shape while managing a lingering and painful injury. I did make it through the Nationals, and I’m grateful for that. But it wasn’t pretty, especially as I hobbled away from the airplane after a flight. Anyone who has dealt with back pain

knows how limiting it can be, especially in a high-G, high-focus environment like an aerobatic box. The physical strain of Unlimited flying leaves no room for compromised biomechanics.

That experience stuck with me. Over the winter I kept thinking about the mistake — not the technical one in the airplane, but the strategic one in how I approached the manoeuvre. I had gone at it with urgency and ambition, but without a fully structured plan. And I had paid the price.

This year I’ve taken a different approach. As I write this, I’m one week away from my first major training event of the season, working with a French coach who’s flying to North America to help prepare several of us for a longterm goal: representing our countries at the 2026 World Aerobatic Championship in New York.

With just a month to prepare at home before that coaching camp, I set out to shake off the rust and rebuild my G tolerance. But front and centre on my training plan was that snap roll — the one that injured me last season. I knew I had to face it again.

I built a gentle progression. I started light, limited the torsional G-load, reviewed every flight using 360-degree onboard footage, and analyzed each attempt for timing, attitude and control coordination. After six or seven flights, something clicked. I found the missing piece in the transition between the pitch and yaw elements, and the figure began to feel… not easy, but possible. Consistent. Repeatable.

And that’s when the fear really showed up. The mental residue of last year’s injury was still there. My brain remembered how it felt to walk away from a flight barely able to bend down and untie my flight shoes. But, step by step, I pushed through it — not by ignoring the fear, but by addressing it systematically.

That’s the real lesson here. Fear has a place in aviation. It reminds us of what’s at stake. But it can’t be allowed to guide the aircraft. You don’t conquer it by pretending it isn’t there — you do

it by preparing carefully, learning from your mistakes and building systems that allow you to progress without rushing.

This spring marks the beginning of a new phase for me. I’m looking at the biggest challenge I’ve ever taken on in aerobatics: a two-year campaign to the World Championships. It’s daunting, yes, but it’s also deeply motivating. The journey to New York in 2026 will involve countless training flights, competitions on both sides of the border, and the occasional setback, without doubt.

But if there’s anything I’ve learned from that snap roll, it’s this: progress isn’t about being fearless — it’s about being focused.

In my next article, I’ll report back on how the training camp went, how the first contest of the year unfolded, and what lessons I’m already pulling from this season. My eyes are on the Canadian and U.S. Nationals later this year, with the hope of earning a place on Canada’s Unlimited team.

See you in the box.

ACessna 180 water-flying trainer operated by Lake Country Airways of Orillia burbled away from a slightly splintered dock at Constance Lake, west of Ottawa. A teenage girl, whose father occupied the left seat, turned to me and asked if float airplanes could fly from regular airports. She listened wide-eyed to my descriptions of dolly takeoffs and landings on grass and gravel airstrips until her father returned with a fresh seaplane rating on his private pilot licence.

The little lady’s interest sparked remembrances of a well-known and respected bush pilot from years ago who regularly enthralled fellow aviators at Red Lake’s Lakeview Restaurant. Born on August 12, 1935, in the Northwestern mining community, colourful and witty aviation pioneer Hartley Weston sometimes reminisced and laughed about his frights launching floatplanes from dilapidated platforms after spring breakup. A glance into my files indicated that the scary process still continues, especially with light airplanes south of the Canada-USA border.

Numerous anecdotes appeared in flying forums and water-flying posts. One wily individual sprayed a Piper PA-11’s floats with soapy water as well as his grass airstrip. Another fastened Teflon to a plywood sheet and used a truck to reach takeoff speed. (The airplane fell off the plywood.) A similar enthusiast slid his aircraft down a sloping 900-foot airstrip with ditches on both sides and later announced to attentive compadres that everyone should experience the fun and “…stripe your shorts at least once.”

Hartley and I kept in touch over the years. In his honour, the correspondence we exchanged resided

in my filing cabinet long before his passing in 2009. Rereading old times after the visit to Constance Lake, I noticed he had flown dozens of types, from scrubby Cessna 180s to glamourous Beechcraft 18s on wheels, floats, skis and wheel-skis. Weston likely held an unofficial record for more dolly takeoffs than any pilot in Canada. He seemed possessed with inner instincts to extract more performance from wings and engines than modernday flight school graduates fingered from their number-crunching handheld computers.

Typical dollies came with two large rear wheels and two smaller units at the front. Helpers shuffled the candidate onto a wooden platform and attached a lightweight cord to one float with the opposite end secured to a springloaded brake handle. At liftoff, the cord activated the brake, and the dolly stopped. Not infallible, the contraption sometimes wobbled out of control and sheared runway lights before running out of momentum.

Towed to the runway or airstrip, most operators disconnected the tow bar, although with slower aircraft, pickup trucks pulled the platform to

flying speed. Before starting the run, the pilot placed the control column forward and waited for adequate airspeed and elevator control before full throttle. Positive climb prevented damage to the truck roof or the dreaded danger of plunking onto the departed surface. An American launch did not go well.

“I hauled butt to 55 mph, and he gunned the engine and yanked in a couple notches (of flap). He lifted and wobbled a little,” the truck driver said.

“I was staring in the mirror when the trailer started to fishtail. I slowed down like an idiot and my son hit the deck of the truck because those floats zoomed right over his head.”

Weston’s career, which began with a war-surplus Tiger Moth registered CF-FUG, included many airplane types on wheels, skis, floats and wheel-skis. No prior training or checkout methods existed for dolly procedures. With twin-engines, asymmetric thrust from the Beech 18’s 450-hp Pratt & Whitney R-985s eased directional control. The massive 47-foot, 7-inch wing and electric 45∞ flap (maximum) added to the safety picture and dolly departures averaged 70 mph. After slugging through

days of slush and whiteouts, Weston described a “hairy” event which caught him by surprise.

Tow bar removed and power applied to the 6,800-lb Beech 18, acceleration seemed normal. Weston readied to apply standard 15∞ flap when an earthquake-like tremor shimmered the airframe. A follow-up “God-awful” bang blurred his world. Before Weston had time to ponder, he realized blue sky no longer filled the windshield. Instead, he had been thrown from the dolly into a near-vertical position with forward view changed to asphalt gray. Beechcraft did not normally assume extreme attitudes.

“At such times, one does not have the luxury of protracted analysis; one responds to the emergency by slamming throttles wide open while simultaneously hauling back on the control column,” he said. “With the aircraft barely assuming level flight, the floats made heavy contact with a resounding crunch, causing the aircraft to ricochet back into the air, vibrating like an oversize tuning fork.”

Milliseconds from converting into a collection of crumpled metal and Weston’s body parts, the tail lowered but airspeed hovered on stall. The low-wing Beechcraft and flap produced enough lift to remain airborne until speed reached a safe balance. The unplanned runway contact damaged both float bottoms and rear support struts, so he returned to car-

ry out a grass surface touchdown. Weston deduced that a malfunctioning brake unit caused a “tire-burning premature halt and threw him into the air. The return to earth, he acknowledged, made his nerves “more twangier.”

On final, Weston maintained a nose-up attitude as slow as could be managed. When the Beech settled, he applied maximum power and pulled the controls brutally back to the stops. Instead of flipping, the aircraft rocked several times in clouds of grass blades and earthworm-infested turf. “Beeches sure were tough buggers,” he concluded.

During the era of Canadian-designed Noorduyn Norseman dominating wilderness skies, the fabric-covered freighters with cabins reeking from moose blood and pike scales returned for changeovers to skis. Pilots like Weston preferred calm mornings or tranquil evenings without unfriendly crosswinds. Compared to most airplanes, Norsemans, cautioned Weston, called for extra expertise and no gentleness when the moment arrived for full and abrupt throttles.

“Approach no more than a couple hundred feet a minute carrying power. As one begins contacting the grass, more power is slowly and carefully applied as shock and deceleration slams one forward in the harness,” said Weston. “As weight on the grass be

comes greater, you rapidly decelerate, and throttle must be fed to the stop as the aircraft comes to a shuddering halt. The Norseman was the only one that consistently left me weak in the knees.”

Weston added that Norsemans had little tendency to flip upside down if “…one kept their cool and power on with full back elevator.”

Weston’s intense interest in northern flying began when, as a toddler, he wandered from his Red Lake waterfront home and pulled himself onto the air services’ docks. During late teenage years, he earned a private pilot licence and bought a de Havilland DH.82C Tiger Moth. To help pay for it, he cleared the front cockpit and installed a plywood floor to haul trappers and native people. Experience gained, he flew numerous more powerful bush planes in all conditions and weather situations. Weston fought off sled dogs in a Fairchild F-11 Husky and survived a flesh-tearing Beechcraft 18 hilltop crash. Employers depended on his skills to test fly rebuilt airplanes and called him first to move changed-over aircraft from decrepit dollies. His dedication enabled others to prosper while he stayed in the background. Today, no monuments or plaques mark his contributions. At least contemporaries still residing in the aviation community of Red Lake still watch Hartley Weston’s skies.

YES, AND IT CAN SAVE YOUR LIFE

Pilots universally dislike surprises. They are stressful at best, and harmful at worse. This aversion often keeps us close to familiar playgrounds. Come summertime though, the temptation to venture away pushes us to tackle new destinations and environments, heightening the potential for unwelcome surprises like an unexpected obstacle on short final or an unusual micro-weather system that we don’t detect until too late.

Meticulous flight planning, sometimes spanning hours, is necessary to mitigate these risks. The military, which thrives on procedure development, has a mnemonic to organize the process: OUTCAST. The approach is transferable to all flight operations with some adaptations.

O: Operating Area. Begin with a broad overview of the route and the airfields. A few years ago, that meant laying down miles of sectionals and flipping through hundreds of pages of aeronautical data. Today, there are numerous apps and Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) available to facilitate and enhance the task. You can even ask Artificial Intelligence (AI) to tell you about your planned flight, but it will remind you that it is only trying its best and you are ultimately the pilot in command. Then, delve into specifics. Where are the destination and alternate airfields in relation to nearby landmarks? What types of approaches, visual and instruments, are available? What is the runway orientation, length, width, elevation and slope? What is the runway current condition? What is the taxiway layout, and how will you navigate from touchdown to parking? Online aviation communities can be a great source of “local knowledge”. Picking up the phone and speaking with the locals at your planned destination remains a tried-and-

true approach to gaining insights.

U: User. This is about mission goal and support, people-wise. Who are you meeting, and where? Is the mission critical? Can it be achieved by alternate means? If you will take passengers, do they have any specific needs? Do you have ground transportation arranged? What about food, customs, fuel, parking/hangar space? What fees are involved? Are services like oxygen or maintenance available? What about WiFi or cell service availability?

T: Terrain. This remains critical, especially given the heightened risk of Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accidents near airports. Leverage satellite photos and 3D imagery to “see” the route and facilities ahead of time. Inflight videos available online can also be useful. Are there nearby towers, power lines, or high-tension wires? Keep in mind that things can change. NOTAMs are still highly relevant to safety. Will the terrain influence weather patterns, potentially creating wind

funneling or wind shears? What is the Minimum Safe Altitude (MSA)? Is density altitude a concern?

C: Communication. Who do you need to contact along the entire route and how? Does the destination airport have a control tower, and what are its operating hours? If not, where is the closest towered airport? How will you obtain the latest weather? How will you close your flight plan? What services can you expect? If you need to pick up an IFR clearance or cancel a flight plan, how will you do so? Is the airfield frequented by aircraft like gliders or agricultural aircraft that might not be on the common frequency?

A: Airspace. What classes of airspace will affect your route and your destination airfield? Do you have the required equipment and a backup plan should the equipment fail? Are there overlying airspace restrictions you need to be aware of? What about Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs)? Are there any Special Use

Airspace (SUA) areas nearby that require consideration? What are their activation times and altitudes? Are there any non-standard circuit procedures, such as right-hand traffic, or unusual altitudes? Are there any unique procedures published in the CFS or in NOTAMs?

S: Sunlight. Here, we consider the level and quality of lighting available. What are the precise sunrise and sunset times for your arrival? Will you be operating directly into a rising or setting sun, a potential blinding hazard? If operating at night, what is the lunar phase and illumination percentage? Is there surrounding unique lighting that might help visual identification of the airfield? What type of lighting does the airport have, and how is it activated (e.g., pilotcontrolled lighting frequencies)?

T: Threats. Consider anything that may constitute a hazard to your operations. Are there parallel runways or oversized taxiways that could cause confusion on arrival? Are there

any runway or taxiway "hot spots" requiring extra caution during taxiing? Are there nearby airfields with similar runway layouts that might lead to misidentification? Is there specific traffic to be particularly aware of, such as high-speed military or airline operations, or significant traffic from a nearby flight school?

The OUTCAST mnemonic provides a robust framework for pre-flight preparation. It helps to proactively identify and mitigate risks through thorough planning, but not eliminate them entirely. Equipment failure or adverse weather can throw a wrench in the best laid out plans. Taking the time to analyze all angles of an upcoming flight will not only help avoid surprises if everything goes as planned, but it will also allow you to be better prepared to successfully adjust the plan should the need arise. Ultimately, a systematic approach to flight preparation will help you build the confidence to expand your flying range safely.

768 Pages – 1,800 Photographs

Order your copy today at aviatorsbookshelf.ca (see page 51)

ONCE LONG IGNORED, NOW OF VITAL IMPORTANCE

Flying an aeroplane requires that pilots be alert and disciplined. They must be in full command of their physical skills and their cognitive functioning must be at its sharpest.

It goes without stating that pilots should, as best as they reasonably can, be free of any conditions that would be detrimental to their alertness, their decision-making and their reaction times when flying. Should any of these human factors be lagging, for whatever reason, perhaps in the presence of such matters it’s best to refrain, temporarily, from being seated behind the controls of an airplane.

The types of factors which are best known to crop up as hindrances to piloting are physiological. Most often this entails serious heart and cardiovascular issues. Certain other physical conditions

such as epilepsy, uncontrolled diabetes or other insidious medical problems which might cause sudden incapacitation can either temporarily or permanently render a pilot unfit to fly. Other health problems such as acute infections are transitory and, while affecting one’s immediate ability to fly, they’ll not disqualify pilots from holding their licence in the way that an acute or chronic issue could.

While a pilot’s physical health has, forever, been the determining criteria for medical fitness to fly, lately there’s been increasingly open talk of a health issue that has long been swept under the carpet: mental health. While being every bit as crucial to one’s flying preparedness, it’s perennially been relegated to the background, stymied by the stigma and sensitivity associated to its breakdown not being amongst the characteristics that

a pilot is ostensibly supposed to have.

Mental health encompasses one’s cognitive, behavioural, social and emotional well-being. It plays a pivotal role in daily life, fostering how individuals balance the daily demands placed on them, how they cope with stress, pressure, decision-making, relationships, etc., and how likely they are to reach the goals and potential towards which they may be aiming. It’s a measure of an individual’s capacity to act in ways to achieve a higher quality of life.

Being a pilot is unique. For the professional, it entails unorthodox work schedules. It means being away from home, and from family, for frequent stretches of time. It likely involves dealing with frequent time zone changes to which one is constantly having to adapt. And there’s the constant pressure required to

maintain the highest levels of professionalism and safety. For the airline pilot, the burden of responsibility to a cabin full of faithful passengers, in and of itself, can induce significant stress: you, as pilot, shoulder the responsibility of their safety. You have to perform at your best; passengers simply sit there, completely reliant on you, your skills and your sense of wellbeing on the day. The lifestyle can, and does for many, take a toll.

Several warnings signs are identifiable as mental health flags. A change in personality is one: someone who doesn’t quite “seem like themself” may be evidence of a mental health matter. Uncharacteristic behaviour, irritability and moodiness may be another. An increase in occupational mistakes, and/or evidence that the individual is struggling with decision-making could be another symptom of trouble. Withdrawing socially or expressions of being overwhelmed should raise flags in the minds of others

that someone in their sphere is facing challenges with which they could use some professional help.

Be it from flying itself or from other factors running their way through one’s life, a not insignificant percentage of pilots — air traffic controllers, technicians, ground personnel and cabin crew too — are subjected to stress, anxiety, depression and other mental issues at various times. The impact on the individuals concerned and, by extension, on flight safety, is emerging as being a vital component towards which the industry is proactively applying recognition and treatment paths.

The stigma surrounding mental health, not least in the aviation field, has traditionally resulted in barriers to assistance for those for whom their mental state is low. For pilots suffering from mental health problems, three themes that work against their addressing of it are: (1) their fear that discussing it will result in

repercussions, (2) they generally distrust the confidentiality of reporting systems, and (3) their belief that the reporting of it will devastate their careers. All of this has resulted in a culture of whispers if not of outright silence.

With such inhibitive factors in mind, various aviation and pilot advocacy groups have been studying how the industry could better deal with mental health. The effort is, thus, now growing to properly foster an environment that places mental well-being on a par with physical health. So, for pilots faced with mental health challenges, the industry is now proactively working at ways to lighten their path to health. The stereotypical days of pilot-jocks born of physical and mental steel are being consigned to the mythology that has always been their reality. People face mental health challenges. That’s the reality, and aviators are no different. Long may a more holistic approach be cultivated.

July 26, 1965, at Constance Lake, a little lake located adjacent to the Ottawa River and about 30 kilometres northwest of the then CYOW Uplands Airport, was the first time I was in a float-equipped airplane, and I was obtaining my seaplane endorsement. The aircraft was a 1955 PA-18 Super Cub, CF-JPK, which is still on the Canadian aircraft registry and shows that it operates out of White River, Ontario. My instructor, and owner of the Cub, was the renowned Russ Bradley of Bradley Air Services. He formed the company just after the war in 1946. Russ and his partner, Weldy Phipps, were pioneer arctic aircraft operators and the first to use Super Cubs on arctic tundra tires, which allowed them to

land almost anywhere on the arctic barren lands. Bradley Air Services went on to become First Air which, in 2019, morphed into today’s Canadian North and services our Canadian Arctic communities with a fleet of jet and turboprop aircraft.

For those of you who are not familiar with the Super Cub, the seating is tandem with the student sitting in the front and the instructor seated behind in the back seat. This two-hour initial flight started out with some air work to demonstrate the handling characteristics of the aircraft fitted with floats. I was instructed to demonstrate a stall. Part way through the manoeuvre I received a fairly sharp smack on the back of the head with the admonishment of, “Whoever

showed you how to do a stall like that?” Hmm, not so sure that instructional technique would go over very well in 2025, but 60 years ago it was apparently an accepted practice.

That first flight on floats led to 42 years of flying on the water and about 6,000 hours of flying floatplanes and amphibians, including two seasons on the venerable twin engine Grumman G-21A Goose flying boat. My theatre of water operations was primarily on the lakes and rivers of Quebec, Ontario, Labrador and British Columbia. Salt water operations included Hudson Bay and the Arctic, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. During much of my early aviation career, and in later years as a sideline occupation, I was a floatplane

training and check pilot and provided advanced float training in a variety of seaplanes.

Most seaplane pilots operate in a single-pilot capacity and often operate in remote and challenging conditions. It is imperative that these individuals be prepared to operate safely in a myriad of changing environments. My job was to prepare these pilots for these operations. Hunters, fishermen, tourists, campers, medevac patients, indigenous families, geologists, miners, foresters, firefighters, big-city commuters, business tycoons and captains of industry were, and continue to be, part of the seaplane pilot’s clientele. Seaplane pilots need skillsets that go far beyond those of their wheeled-plane counterparts to provide safe conditions for themselves and their passengers.

Glassy water, rough water, small, confined lakes, ocean swells, tidal currents, marine harbours, fast-flowing rivers, shallow lakes, floating debris, shoals and reefs are all considerations that the pilot must consider prior to takeoff and landing. An imperative skill that the seaplane pilot must develop is the ability to read the wind on the water. When landing, taking off, docking and/or mooring, the seaplane pilot must always be cognizant of the wind, much more so than their landplane counterpart. Water operations are unforgiving and a hard landing or a landing with even a little side drift can result in disaster. Taxiing a light airplane on land, in high winds, can sometimes be a challenge but when taxiing on the water in these conditions, it takes an entire new set of skills to do so safely. Water taxiing must be done very slowly or conversely very fast, and this latter mode is referred to as “step taxiing.” Turning in and out of wind techniques can differ significantly, depending on the type of aircraft. In a twin-engine turbine aircraft that has reversing capability, like in the Twin Otter, it can be a piece of cake. Turning a piston Single Otter, with its large tail surfaces, can be a major challenge and requires type-specific techniques. So far, we have considered takeoffs,

landings and taxiing, but the goal is to put your passengers and/or cargo safely ashore and then depart again, and this is another whole dimension. Docks or floats that are specifically designed for seaplanes are few and far between. More often than not there are other challenges such as marine craft, pilings, protruding sharp objects, waiting to puncture delicate pontoons, and a host of other challenges. Currents, tides, winds, children, dogs and well-meaning “lookie-loos” are other factors.

When operating in wilderness conditions, docks are nonexistent and sandy beaches with the right slope are a rarity. More often than not there are trees right down to the shoreline and the shores are infested with sharp rocks and boulders. Ramps and suitably sloping shorelines to taxi amphibians up are another story. Another skill that is not used very much anymore, but pilots should be cognizant of, is the ability to tie up to a buoy. Also, how to use an anchor in fast-flowing rivers, or to ease one’s aircraft back on to a windward rocky shoreline. These are almost a lost art but were used in remote high wind situations. Ropes, rope handling, and fuelling on the water in remote locations must also be learned. Another topic not yet touched on is the carrying of external loads, the most common being marine craft.

To the uninitiated, all these challenges, and more, sound rather

daunting and maybe discouraging. Not so. When these skills are mastered, the floatplane pilot is as professional as the airline captain shooting an approach on a dark and dirty night in a large transport aircraft. Just different skills. Christmas Eve, 2007 was my last day in the office before retirement. In the hangar below were a couple of King Airs, a Twin Otter, a couple of helicopters and a Cessna 206 on amphibious floats. Well, I was the boss and there had to be some perks to this job that I was leaving. I had made arrangements to keep on flying in retirement, but this would likely be my last opportunity to do my favourite type of flying. I took it, and the Queen paid for the gas. The office manager had never been in a floatplane, so I piled her into the Cessna and I took off from CYVR and flew up to Pitt Lake and shot a few last touch-and-goes on the water. You can do that on the West Coast in December.

After landing back at the international airport I gave the floats a little pat and hung up the float flying forever. I still have fond memories of the water, the wilderness, the myriads of lakes, rivers and coves that I have landed in over the years. These are just memories now, but I hope this little story may inspire some young and upcoming pilots to venture into the world of flying off the water. In doing so I wish you all the old bush pilot’s blessing: “May you have tight floats and tailwinds.”

A REVIEW BY RENÉ R. GADACZ

BY MICHAEL VLESSIDES

If you’ve ever found yourself on the ramp at -30°C with numb fingers and jet fuel on your coveralls, Michael Vlessides’ The Ice Pilots will feel familiar. But even if your aviation experience is limited to sunnier latitudes or more modern cockpits and flight decks, this book offers an engaging and gritty look into one of Canada’s most legendary northern operations: Buffalo Airways Ltd., based in Yellowknife, N.W.T., Hay River, N.W.T. and Red Deer, Alta.

Best known to the public through the History Channel series Ice Pilots NWT, Buffalo Airways is more than just reality TV; it’s an all-weather, no-nonsense company that flies freight, fuel and passengers in some of the oldest airworthy aircraft still operating commercially. Vlessides, a writer and journalist, embedded with the crew for several seasons and, bitten by the Buffalo bug, delivers a firsthand account that is part memoir, part historical retrospective and all aviation passion.

The book follows the seasons of Buffalo’s unique operations, beginning in the bone-cracking cold of a typical Yellowknife winter, moving through spring’s melt and breakup and into the high-paced tempo of wildfire season. Each chapter is anchored in specific events: supply runs, medevac flights, mechanical issues, training days, latenight maintenance and fire suppression missions. Vlessides uses them as launch points to explore deeper stories of the people, the aircraft and the ethos of northern bush flying.

The heart of Buffalo Airways is Joe McBryan (“Buffalo Joe”), founder and patriarch, whose aviation credentials and sheer personality need no introduction in Canadian aviation circles. Vlessides does a fine job of capturing Joe’s contradictions: his Luddite stubborn

insistence on doing things his way, the sharp temper that creates tensions for those around him, the deep loyalty to his crew and customers and the unshakable love for the ships under his care. He is the kind of owner-operator who still flies, still wrenches and still sets the tone for the entire company.

Vlessides also spotlights key figures in the Buffalo crew — chief pilot Arnie Schreder, the ever-calm veteran presence in the cockpit; up-and-coming rookies learning to tame taildraggers in high winds; mechanics working miracles in improvised hangars at remote gravel strips. Aviation professionals will appreciate the inside look at these people’s day-to-day work, from the challenges of keeping radial engines (“piston pounders”) humming in subzero conditions to managing fuel logistics on the edge of nowhere.

The book also shines a spotlight on the younger generation of pilots, some barely out of flight school, who come to Buffalo Airways seeking adventure and the all-important flight hours. Unlike their peers elsewhere, these rookies learn to fly in some of the most demanding conditions, often with outdated instruments and minimal technology. Most don’t last long, surrendering to the cold or the intensity of the work.

One of the book’s real strengths is the respect it pays to the aircraft. The Douglas DC-3, DC-4, Curtiss-Wright C-46 Commando (a.k.a. “Dumbo”) and Lockheed L-188 Electra are more than just machines in Buffalo’s hangar; they are characters in their own right. Vlessides writes with reverence about these airframes, detailing their Second World War heritage, quirks, strengths and the painstaking maintenance required to keep these ships in the air. There is a particular satisfaction in seeing these classics continue to earn their keep in

a world dominated by digital cockpits, AI-assisted flying, GPS and composite skins. By documenting the continued relevance of analog systems and handson experience, The Ice Pilots challenges dominant narratives of technological progress and so celebrates a form of flying that is increasingly rare.

Readers familiar with aircraft systems and flight operations will find plenty to sink their teeth into. Vlessides doesn’t bog the narrative down with jargon, but neither does he shy away from describing the nitty-gritty: startup procedures on a frosted-over DC-3, dealing with carb icing at 8,000 feet, emergency repairs in subzero temperatures and firefighting sorties in Canadair CL-215’s (a.k.a. “the Duck”) and Lockheed’s Electra dropping 12,000 pounds of water every few minutes on Yukon wildfires. These aren’t just anecdotes; they are reminders of the skill, judgment and resourcefulness required to fly in the North.

There’s also an underlying respect for aviation culture throughout the book. Whether it’s the hangar-floor banter, the rite-of-passage ‘checkouts,’ or the campfire storytelling that always fol-

lows a good scare, The Ice Pilots captures the language and lore of pilots “who fly by feel.” Vlessides is honest about the risks, the mistakes and the hard lessons learned. Near-misses, fuel miscalculations and mechanical failures are all part of the job and part of the story.

That said, the book never loses its sense of admiration for the job these crews do. The North demands a different kind of flying — low, slow and often without much margin for error. Buffalo pilots often operate under pressure most modern operators would find unthinkable: weather that can turn on a dime, short gravel runways, non-existent instrument landing systems (ILS) and cargo that simply can’t wait. This is a world where good stick-and-rudder flying still matters, where checklists are memorized, not programmed and where customer relationship management (CRM) happens face-to-face, not over VHF.

The Ice Pilots is more than a tie-in to a television show; it is an ode to Canada’s northern aviation history and heritage and those still living it. If you ever have the chance to look at Buffalo Airways’ vintage Douglas DC-3 (C-GWZS, one of nine) that you knew flew on D-Day, dropping paratroopers over Normandy, or knew that their Douglas DC-4 (C-FBAA, one of 13) was used in a recreation of the historic 1943 Dam Busters raid over Germany and would feel awe, this book will resonate.

In a time when aviation is becoming increasingly automated and risk-averse, The Ice Pilots reminds us of a different kind of flying: hands-on and high-stakes. This book is worth the read for anyone passionate about Canadian aviation, classic aircraft and the realities of Arctic and sub-Arctic flying. Buffalo Air is alive and well and, since Vlessides’ book published 13 years ago, the company has expanded its current 62-aircraft fleet to include a Boeing 737-300, among others.

The Ice Pilots: Flying with the Mavericks of the Great White North

By Michael Vlessides

Douglas & McIntyre, 2012, 271 pp. Available from The Aviator’s Bookshelf (aviatorsbookshelf.ca)

Just weeks away from my 66th birthday I found myself — yet again — a student of flight. Strapped in beside me was Cameron Spring, the operations manager for Phoenix Heli-Flight, based at CYMM in Fort McMurray. Situated on the floor between us was the Airbus EC-120 Colibri helicopter’s right seat collective lever, which I was pulling up, ever so slowly. To counteract the twisting force of the rotor, I gently input cyclic pressure and pressed on the anti-torque pedals, remembering (just in time) that most European helicopter rotors turn opposite to those on the Bell 206 Jet Ranger I’d once flown. We wobbled a bit at first, then lifted into a hover.

Even after a 17-year hiatus from flying helicopters, surprisingly enough came back for my instructor to move his hands far enough away from the controls for me to notice. For the next 48 minutes, I practiced hovering, landings and takeoffs on the CYMM apron, and then again onto a still-frozen Clearwater River. Cameron went so far as to let me recover at their base, flying an approach through a gap in the forest before turning 90 degrees, touching down on a pad in front of the Phoenix hangars, more-or-less properly aligned. It was an amazing experience, reminding me how much I enjoy helicopter flight.

But the truly glorious, nearly one-hour flight down rotary-wing lane wasn’t the reason for my returning to the city I once called home during the mid 1980s. Paul and Andrea Spring, the owners of Phoenix Heli-Flight, had recently added a brand spanking new Diamond DA62 airplane to their fleet of 11 helicopters, expressly for the purpose of transporting flight crews during fire season. On assignment from Ed McDonald’s JetPro Consulting, my job in Fort McMurray was to help Cameron garner a multi-engine instrument ticket, and the same, preceded by a multi-engine rating, for their chief pilot Steve Harmer.

Cameron Spring learned to fly with the Air Cadets and has logged nearly 4,700 hours in helicopters (which industry credits at a 3 to 1 ratio when compared to equivalent fixed-wing experience). He first graduated with a degree in Business, then went on to complete his Commercial Helicopter Licence before joining the company his parents built from one leased helicopter and rented hangar space.