5 / WALKAROUND

6 / WAYPOINTS

Aviation news By Aviator staff

7 / AIRMAIL

A nostalgic Mallard

9 / GEAR & GADGETS

Four aviation products By Aviator staff

10 / FLYING STORIES

Demotivating governments By Jack Schofield

12 / A PILOT’S LIFE

Red Star – Part 3 By Chris Weicht

15 / VECTORS

GPS dependency

By Michael Oxner

16 / THE PLANE FIXER

Avoiding insanity

By Liana Beussecker

18 / WHIRLYBIRD WRITINGS

Herding sheep By Michael Bellamy

20 / UNUSUAL ATTITUDES

A legendary master By Luke Penner

22 / TALES FROM THE LAKEVIEW

The early days of medevacs By Robert S. Grant

24 / RIGHT SEAT

Risk management By Mireille Goyer

26 / PEP TALK

Need to know more By Graeme Peppler

28 / COLE’S NOTES

Remembering Tony Swain

By W.T (Tim) Cole

30 / WORDS ABOUT A BOOK

His Majesty’s Airship

By René R. Gadacz

32 / EXPERT PILOT

A dark, dark night... By Richard Pittet

50 / BOOKSHELF

Top aviation titles

52 / SERVICE CENTRE

Deals and offers

54 / FLIGHT BAG

Puzzle and questions

Victoria-based commercial pilot and amateur photographer Aaron Burton once again (e-Beaver, 2024) scores a cover photo with this Kingfisher takeoff from YYJ. ON THE COVER

Forty years on, these foreign millionaires are still missing in B.C. By Dirk

Septer

Captain Kate Speer’s globehopping path to a Porter left seat. By Robert S. Grant

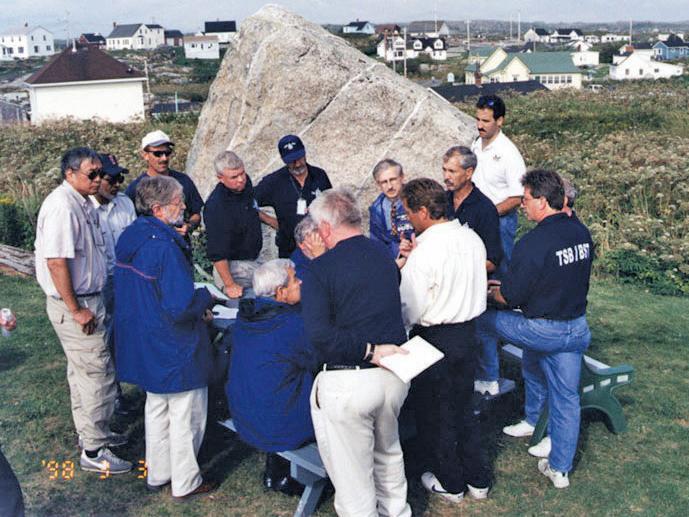

What the TSB has been doing for 35 years. By Yoan Marier

Readers of this space will know that I often write of matters related to our military; more specifically, the Royal Canadian Air Force. If not here, then feature articles written by others I select to publish. Stories that hark back to an era when the RCAF was a force to be reckoned with. It’s not that I have any particular relationship to that storied institution, other than a stint as an Air Cadet in my youth. Rather, it was my boyhood dream of being a pilot in the RCAF that drew me into a fascination with all things aeronautical. At some point in my cadet career I decided that the military had no place in my

future (a decision that, much later, had me wondering whether I had made a mistake). But the longing to become a pilot never left me. It wasn’t until my mid-30s, however, that I fulfilled that ambition. Since then, my life has been interspersed with aviation career moves: once running a flight school, then writing for and editing an aviation magazine, now also selling kit airplanes. During much of that time, I was flying my own airplane, something I continue to do. Were it not for the youthful excitement of flying fast air force planes, I might never have taken up flying as a hobby that later led to an aviation-related second career.

We all know that the last two or three decades has seen a decline in the number of flying opportunities in the RCAF, concurrent with a lack of interest by young people in aviation as a career. Numerous institutions have been trying to reverse that trend for years, though not with overwhelming success. That may be about to change.

The evolving reality of world affairs, leading to the now-planned rejuvenation of the RCAF, may once again spark a child’s imagination and draw him or her into the world of aviation, whether by serving our nation in uniform or simply to pursue the dream of flight.

The long-awaited replacements for the RCAF’s fleet of DHC-5/ CC-115 Buffalo Search and Rescue (SAR) aircraft have finally become operational as of May 1, 2025. The Spanish-made Airbus C295 is the CC-295 Kingfisher in RCAF service, and five of the twin turboprops have already been delivered to CFB Comox on Vancouver Island, serving with the 442 Squadron of 19 Wing. The Kingfishers will also replace certain models of the Lockheed-Martin Hercules that were serving as SAR aircraft; specifically, the CC-130H model.

While conventional Canadian SAR aircraft were designed to go low and slow and have short-field takeoff and landing characteristics, the Kingfishers were not designed for this. Instead of relying on human observers peering out of bubble windows, on board the Kingfishers are an array of high-tech sensors and instruments, such as MX-15 Electro-Optical and Infrared Cameras, that can detect persons or objects like a downed aircraft or a sea vessel in distress from more than 40 kilometres away. The Comoxbased Kingfishers will cover not only Canada’s West Coast and out over the Pacific Ocean for 1,500 kilometres, but the entire province of British Columbia as well as Yukon Territory.

The contract with Airbus is for 16 CC-295s spread across Canada, including Winnipeg, Manitoba, Trenton, Ontario and Greenwood, Nova Scotia in addition to Comox,

“The addition to our SAR capability will significantly enhance our ability to respond to Canadians in need and save lives.”

— Lt-Gen Steve Boivin

B.C., which will be home to a newly constructed training centre replete with state-of-the-art flight simulators. Comox’s 418 SAR Operational Training Squadron is responsible for the training of the aircrews and maintenance personnel, and 19 Air Maintenance Squadron will perform maintenance of the Kingfishers.

“Canadians should feel assured that as of [May 1], a fully capable and crewed CC-295 Kingfisher will be available 24/7, 365 days a year throughout Canada’s western territories and waters to support SAR activities,” according to a statement from the Department of National Defence.

The current service standard for response time for 442 Squadron (which

also includes CH-149 Cormorant helicopters) is two hours from the time an alert is received at the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) in Victoria. However, it is expected that calls received during the hours of 08:00 and 16:00 will be responded to within 30 minutes.

“The addition to our SAR capability will significantly enhance our ability to respond to Canadians in need and save lives,” said Lieutenant-General Steve Boivin on May 1. Lt-Gen Boivin is Commander of Canadian Joint Operations Command.

Acquisition of the Kingfisher fleet was budgeted at $2.9 billion with another $2.3 billion to maintain them for 15 years.

The “Great Magazine” did it again! [The photo of the Mallard in the May/Jun issue, Flying Stories] brought back old, favourite memories. I worked for K&N Shipping. Arrow Transport hauled our containers from Seattle to our warehouse in North Vancouver. As a good customer, I was a guest on the owner’s vessel, the MV Hotei, in Hecate Strait. They flew us from Vancouver and landed on the water beside the Hotei in that Mallard. I sat beside the pilot and those big props, spinning right beside me, were intimidating. Bob Bradley, Surrey, B.C.

The Jul/Aug issue’s crossword puzzle contained two errors. 4 DOWN should read: A colleague of 10 ACROSS. 15 DOWN should read: Fan of 10 ACROSS. Canadian Aviator apologizes for the errors.

On page 46 of the May/Jun issue (“The Great London-Victoria Air Race”) we used a photo of competitor Rick Cockburn’s Harvard on the ground during a stopover in Ottawa on its way to Victoria. We neglected to assign credit to the photographer, David Dickens of Monterey, Calif., who was in the nation’s capital that day. Canadian Aviator regrets the omission.

Could you use a pair of compact but effective set of wheel chocks? Innoquest of Woodstock, Illinois promotes its product as “The chock that stays put.” Made of solid polymer with a rubber bottom, the chocks are connected by a cord that wraps around the chocks making them easy to store. They are contour-shaped, preventing pressure points on tires and making them easy to position. Each chock measures 4.25" x 7" x 2" (10.8 cm x 17.8 cm x 5.1 cm). The cord length is 24" (61 cm). About C$111.

Learn more at innoquestinc.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

Do you have a favourite pair of sunglasses but have trouble reading the small print of your charts or your iPad app? Do you find that your untinted progressive lens don’t offer enough protection from bright sunlight? Optx2020 of Deerfield Beach, Florida offers their Hydrotac Optx 20/20 StickOn Bi-focal Reader Lenses. Turn those favourite sunglasses into bifocals with the exact amount of magnification you need: 1.25x, 1.5x, 1.75x, 2x, 2.5x or 3x. The lens are both removable and reusable. Use scissors to trim to the exact shape you want. About C$40.

Learn more at optx2020.com Available from aircraftspruce.ca

Do you rely on a cheap, stick-on carbon monoxide detector to protect your life and those of your passengers? Did you know that, even when they work as designed, it might already be too late? Or maybe you have no CO detector in your cockpit at all. Consider the Sensorcon AV8 Inspector Pro from California-based Inspector Tools. The portable lightweight device features adjustable audio, visual and vibrating alarms. It also features a “time-weighted average” function that monitors exposure over a 24-hour period. Battery life is two years, and its built-in loop allows for suspension anywhere in your cockpit. The device measures 3.2" x 2.2" x 0.9" (8.1 cm x 5.6 cm x 2.3 cm) and weighs 4 ounces (113 g). About C$326.

Learn more at inspectortools.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

USB chargers that plug into a cockpit’s cigarette lighter socket are cheap and easy to find. Many, however, cause interference on aircraft radios. My Go Flight of Denver, Colorado offers a made-for-aircraft charger that is equipped with both USB-A and USB-C connections. What’s more, it has a digital display that acts as a voltage meter and displays amps out when a device is plugged into it. The charger supplies enough current so that an iPad running aviation apps will continue charging while in use. 12 to 32 V input. About C$78.

Learn more at mygoflight.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca

Once upon a time, in the days before civil aviation was deregulated, there was a government commission known as the Canadian Transport Commission, the CTC as it was referred to by the industry. Any mention of this CTC always brought forth an expression of exasperation because this committee was a roadblock to doing business in the Canadian aviation industry. Why? Because it was created in 1937 to make absolutely certain that the government airline, Trans Canada Airlines (now Air Canada), would operate without competition.

Staffed with appointees made by the Prime Minister of the day, committee members of the CTC were usually lawyers who knew nothing of the flying business, but were charged with ruling on who could fly, and where. If you wanted to fly some loggers into camp, some native villagers into their village and some sport fishermen into a resort, you first had to ask, in writing, the CTC for approval — in triplicate, no less — to establish your airline. One of your application papers went to the airline closest to your proposed base of operations. He was asked for his comments, and he always had some colourful ones, like his claim that you were out of your mind, that he was already providing that service was called “an intervention” and such interventions always won the day.

So, you couldn’t just plop an airplane into some little town and start hauling your loggers. You had to appear in court first and present your case to the CTC to justify the need for such a service as you proposed, and the odds were that you would fail to be issued a licence because everybody in that courtroom wanted you to fail. So, if getting an application to establish an airline was so difficult, what could a person do? The answer of course was to buy out a guy who already had

a licence, and while you were smugly smiling that you had outfoxed the CTC, they dropped the news on you that it was illegal to sell a licence. An airline’s assets could be purchased but you could not buy the licence. Licences were transferrable, but such a transfer became the subject of another decision for or against the transfer by the CTC and that decision was going to take another year.

So, what you did then was to connive to purchase the licensed airline’s clapped out Cessna 180 for which you would pony up an extra five grand over market value for the aircraft and the owner would then agree to transfer the licence, with a knowing smile, and would then allow you to fly under his name for as long as it took to get the transfer approved. What a game it was, and it was played just like that by a succession of aviation entrepreneurs such as the famous Grant McConachie, whose client, Canadian Pacific Railway, bankrolled his purchase of a whole gaggle of little guys that gave the new Canadian Pacific Air-

lines he had created the route structure to establish a domestic carrier that planned to compete with the national airline Trans Canada Airlines.

It was the game also played by Russ Baker, whose Central BC Airways bought out Jim Spilsbury’s Queen Charlotte Airlines (QCA), allowing Baker to establish Pacific Western Airlines (PWA) as a British Columbia regional service. In more recent years, it allowed B.C.’s favourite entrepreneur, Jimmy Pattison, to buy out and amalgamate six little coastal outfits into a company he called AirBC, which was quick to become the latest B.C. regional service. AirBC ultimately performed over 40 percent of Air Canada’s feeder service and was later sold to Air Canada at a significant profit to become that national carrier’s Canada-wide regional feeder service now known to you and me as Jazz.

So, such a game it was when government regulation prevailed, but the real reason for it all was to ensure that Trans Canada Airlines (TCA), the

airline created by Canada’s Parliament, could operate free of all threat of competition. The Trans Canada Airline Act declared that no other airline could parallel the routes of the national carrier. When Canadian Pacific Airlines looked capable of threatening TCA, an order in council was hurriedly passed requiring that an airline could not be owned by a railway system. While the target was obviously the Canadian Pacific Railroad’s airline division operating as CPAir, it was argued that the Government themselves were in contravention of their own rules as, not only did they own the national airline, but they also owned a railway system — the CNR. Nevertheless, CPAir were relegated to fly only to destinations off the main domestic airway routes across Canada and, when instrument landing systems (ILS) came into being, these systems were installed only at airports

serviced by the government’s TCA.

The Trans Canada Airlines Act had the effect of stifling the aviation industry and the need for deregulation was being espoused by the industry in the face of total indifference by government until one day…and here at last is the story you were being primed for…

“GOD HOW I LOVE AVIATION”

Who are we quoting? Barry LaPointe, an instrument rated commercial pilot and also an AME). Barry held what was once called an ATR — an Airline Transport Rating. He also had a Ford pickup with a big tool kit in the back. He put all this together over his lifetime and has now retired, having created Kelowna Flightcraft, now known as KF Aerospace. Be careful not to abbreviate that company name to KFC, because Flightcraft is no chicken; it is the largest and most significant aerospace company in Canada. So, where does Barry

Lapointe fit into the Trans Canada Airline Act? The answer to that is that he did not fit into it at all. In fact, he shot it down in flames, opening the door for deregulation.

How did he do that you ask? Well, it’s a little long to elaborate on here, so tune into a future issue of Canadian Aviator to get that story. But I assure you it is a good one that you won’t want to miss. And, I might add, it has never been told before in print.

And, while I have your attention, here is an aerospace history question I ask all Canadian aviators to answer upon the eve of the U.S.’s 25 percent tariffs aimed at Canada: What Canadian Government was in power when the Canadian aerospace industry was totally disassembled by caving in to gunboat politics from the U.S. oval office?

I think I just shot an Arrow in the air!

On Monday, June 14, 1937, Soviet Agent Vartanian in Seattle had made radio contact in code with the group at Goose Island and advised them to expect a message on June 17 concerning the arrival of the Tupolev ANT-25.

The departure of the ANT-25 from Shelkova airport near Moscow was recorded as 04:05 Moscow time, or 01:05 Greenwich Mean Time on June 18, 1937, with considerable press coverage. Valery Chkalov was in command, with Georgy Baydukov as copilot and Alexander Belyakov as navigator. As the aircraft took off, photos clearly showed the ANT-25’s departure.

The flight apparently proceeded on schedule. However, communications with the ANT-25 were all handled through Soviet agent Vartanian in Seattle, who in turn received progress messages from repeater stations in Vladivostok and Khabarovsk, Siberia. Vartanian would then translate and provide copies to the US Army Signals Corps at Seattle.

The single exception to this routine was messages received from Canadian Army Signals Corps at Edmonton, which stated that they had received four messages in Russian that they thought had originated from the ANT-25 and were relayed to Vartanian. The first message was received 35 hours after the aircraft departed Moscow, stating, “Everything OK travelling 120 mph, location Prince Patrick Island 800 miles south of the pole on the American side.” Later messages were received from Fort Norman and near Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. The first message received by US Army Signals at 20:32 PST stated, “Entering Alberta and heading for Pacific Ocean.” However, U.S. authorities had expected the aircraft to follow the 120th Meridian through Edmonton and Spokane and on toward its planned destination.

At 21:00 PST a message from the ANT-

25 stated, “Over Queen Charlotte Islands following shipping lanes to Seattle.” But something was amiss here. Only 28 minutes earlier their message was received stating the aircraft was leaving Alberta for the Pacific Coast, an impossible feat for an aircraft barely able to maintain 100 mph, and probably a lot less, against the westerly winds. The ANT-25 was certainly not supersonic.

Navigator Belyakov later sent a message direct to his consulate in San Francisco stating that they had used 2,619 gallons of fuel since leaving Moscow, which was very strange since the ANT-25 had taken off with only 2,000 gallons on board. As the aircraft approached the mouth of the Columbia River at Astoria, it was spotted at 07:15 by a US Coast Guard cutter. One hour later, at 08:16 on June 20, 1937, it landed at Pearson Field. At this point it had averaged only 60 mph since leaving the Queen Charlotte Islands (present-day Haida Gwaii).

The English publication “The Aero-

plane” of September 8, 1937, took issuance with the authenticity of this flight. It stated that there was no possibility for the ANT-25 to stay aloft for anywhere near the amount of time to make the transpolar flight and suggested it had been refuelled. Its editor, C.G. Grey labelled it a “Flight of Fancy”. U.S. authorities, however, recognized the Soviet record claim without reservation.

Had the Russians really completed a nonstop flight? If so, how did they manage to make the 1,900-mile-range aircraft accomplish the feat? If the aircraft was refueled, where did this happen and what evidence is there?

The copilot of the flight, Georgy Baydukov, assumed the position of spokesperson for the tour. Baydukov was interviewed in Ogden, Utah, by a Mr. N. Vishnevsky, who was a Russian-born American retained by the State Department of the United States. Vishnevsky stated that Baydukov advised him that their flight had stopped at Marshall

Field, British Columbia, on the supposedly nonstop polar flight. Whether this was meant as a confidential aside between two Russians is unknown, as most of the American documentation relative to the whole incident is still marked “SECRET.” The reference to Marshall Field is a mystery as there is, or was, no such airfield in the province of British Columbia.

Possibly the reference was to General George C. Marshall, who was the commanding officer of Pearson Field and the United States Army Barracks at Vancouver, Washington. Is it possible that General Marshall masterminded the United States’ participation in this so-called “nonstop” polar flight?

In his own memoirs, General Marshall had mentioned that he considered his post at Vancouver, Washington, to be the end of the line as far as his career was concerned. However, his duties there included the supervision of the C.C.C. (Civilian Conservation Corps.) camps and Public Works projects throughout the Northwest. He had also been visited by none other than the Russian radio agent, Vartanian, prior to the arrival of the ANT-25.

In view of all this, we speculate that the airstrip prepared at Goose Island by the C.C.C. Natives was named Marshall Field in honour of their leader, General George Marshall. In any event, his career certainly skyrocketed after the successful completion of the Russian “nonstop” flights. He was personally selected by Franklin D. Roosevelt over 33 other general officers for the position of United States Army Chief of Staff. Other promotions included U.S. Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense and Special Ambassador to China. He was also the architect of the Marshall Plan in Europe, which won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.

In December 1992 I attempted to find if any of the remaining Elders of the Heiltsuk Tribe remember the bizarre occurrence of 1936 and 1937 at Goose Island. I was able to learn of one Elder named Phillip Hall, who was a young man in his early twenties at the time of these flights, and he remembered a group

of Americans and foreign Native Indians with a large aeroplane at Goose Island. There was also a memory of the arrival and landing of the aircraft.

The Heiltsuk natives were not the only ones to witness the landing of the aircraft. On the late afternoon of June 19, 1937, a vessel travelling in the Queen Charlotte Straits sent a message to the Canadian National Telegraph office in Prince Rupert stating that a large Russian aircraft was observed going down on an island near Bella Bella. This message was relayed to US Army Signals Corps in Seattle who in turn passed it to Russian agent Vartanian, who denied its authenticity.

As stated earlier, in 1993 I interviewed Archie Miller, a long-time resident of Bella Bella who, during the Second World War, served as an RCAF marine officer. In 1943 he was ordered to take men and equipment to Goose Island and to survey the possibility of constructing a runway on the tidal lagoon for the landing of land-based aircraft.

In the summer of 2006, while on a speaking tour of northwest British Columbia, I spoke to a large group at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George. At the conclusion of my talk, I was approached by a man who identified himself as a retired BC Forest Service captain on coastal patrol boats. He stated that after the end of the Second World War, in 1946, he was ordered to proceed to Goose Island with his crew and destroy any structures remaining on the lagoon. He was advised that this activity was to remain a secret.

On the early morning of June 20, 1937, the Russian ANT-25 landed at Pearson Field at the Vancouver, Washington US Army Barracks, where its arrival was stated as unexpected, yet two Russian speakers just happened to meet its arrival. George Kozmetsky was a United States Army Reserve officer. Also present was a woman who was a university student. Shortly prior to the landing, U.S. security officer Lieutenant Carlton Bond received an FBI message stating that the aircraft originally destined for San Francisco would land at Pearson

Field where Bond served.

Photographs taken at the departure of the ANT-25 from Moscow show that the right side of the aircraft was painted in white with no markings. However, on its arrival at Pearson Field 63 ½ hours later, both sides of the ANT-25 were emblazoned with the inscription in Russian “The Route of Stalin,” a little hard to do on a supposed “nonstop polar flight.”

We suggest that the flight that departed Moscow’s Shelkova airport was a ruse, with radio transmissions supplied by Vartanian along the way that would hopefully legitimize the flight, and that the actual aircraft took off from Siberia and proceeded via the Aleutian Islands, the panhandle of Alaska, the British Columbia coast to Goose Island, where it was refuelled, and then continued to its destination, arriving at 08:16 PST at Pearson Field on the north side of the Columbia River, across from Portland, Oregon.

The intent to impress the belligerent axis powers with the possibility of Soviet reprisals likely failed. But Franklyn D. Roosevelt’s efforts to support the Russian ruse and bring the U.S.S.R. into the Second World War on the side of the Allied powers eventually succeeded, and the Lend-Lease program was a huge benefit in bringing a conclusion to the war.

In recent years, the surviving Tupolev ANT-25 has been relocated to the Central Air Force Museum at the Monino Airfield military base in Shchyolkovo, Russia, about 35 miles by road from Moscow.

Today, Goose Island is still uninhabited. The tide has come and gone tens of thousands of times since the Russians visited the lagoon over 85 years ago. No sign of their activity remains. The ravens and seagulls continue their eternal vigilance. The occasional visitor comes to hunt deer or geese, which abound. Goose Island is just as rugged and beautiful as it was to Sigismund Levanevsky on that misty day in August, the year before, when he landed the Vultee V1 floatplane on the clear waters of the island’s lagoon.

For over 80 years, the content of From the Ground Up as a literary benchmark that defines the multitude of theories associated to aeronautics. It describes the practices necessary to achieve the highest levels of distinction as safe, competent and skilled life-long aviators.

Through its evolving editions, many generations of readers have used this award-winning title as the foundation of their introduction to the concepts that require thorough understanding in advance of the sought-after hours of flying enjoyment that are the ultimate goal of all who seek to earn their wings and expand their knowledge of flight theory and practice.

The content of From the Ground Up may, at times, seem complex, but the pathway to learning the fundamentals of aeronautics is one that reaps much in the way of personal reward for all who pursue the goal of thoroughly understanding the subject. Indeed, it was by design that its original author, “Sandy” A. F. MacDonald — a man recognized as a “father” of what still stands today as the standard curriculum for ground school instruction — devised this aeronautical textbook to be comprehensive and current while conveying its material in such a way as to enhance the reader’s understanding of every written word.

Not one to permit his vast experience to allow for foregone conclusions, “Sandy” MacDonald’s meticulous care in the creation of From the Ground Up has become the hallmark for its widespread use and respect as the reference textbook of choice in hundreds of flying schools throughout Canada and around the world.

Its latest edition is the 30th Edition. A French-language version is also available under the title Entre Ciel et Terre Totalling over 400 pages of in-depth content formatted in a sequential, logical and easy-to-read fashion, the publication boasts over 360 graphics, charts, diagrams, illustrations and photos. An additional full-colour navigation chart and a sample weather chart are included.

All chapters are current in the latest technological and legislative aeronautical matters and cover such topics as The Airplane, Theory of Flight, Aero Engines, Aeronautical Rules & Procedures, Aviation Weather, Navigation, Radio & Radio Navigation, Airmanship, Human Factors, and Air Safety. From the Ground Up also includes an extensive index, glossary and a 200-question practice examination.

Since the 1940’s, virtually every student — civilian, military, commercial, recreational — who has ever learned to fly in Canada has used From the Ground Up as the primary ground school textbook from which they’ve learned everything one can learn about aeronautics, and about flying. Referred to as “the Bible” of ground school instruction, and updated with every frequent re-print, From the Ground Up has long been considered an essential resource for all with any interest whatsoever in the theory of flight, and in the practice of aviating.

Also available from Aviation Publishers

• From the Ground Up Workbook

• Canadian Private Pilot Answer Guide

• Canadian Commercial Pilot Answer Guide

• Canadian Instrument Pilot Answer Guide

• Instrument Procedures Manual

• Flying Beyond: for Commercial Pilots

• Unmanned: for RPAS Studies

• Flight Test Notes: for Flight Test Prep

For more information about all of our titles, visit us on the web or contact your local pilot supply

frequent question I receive from pilots, including career pilots in a variety of jobs and private pilots as well is, “Should I be in contact with ATC?” As you can imagine, there is a lot to the answer to that question. What are the considerations, and why ask the question? Let’s tackle the first question. It may sound obvious when I ask, “What’s the classification of airspace?” But the answer brings up some grey areas. If you’re IFR, then yes, contact ATC. Until you’re released from ATC’s frequency, you should be monitoring the radio for ATC messages and clearances all the time. If you have to leave the frequency temporarily, talk to the controller first to ensure any messages in the nearterm get through to you.

If you’re operating under VFR and the airspace is Class D or higher, the answer should be obvious. In Class D, pilots must establish two-way communication with ATC prior to entering and remain in contact. Above Class D, VFR pilots must follow clearances and instructions with a lot more care to ensure that the plan for separation the controller is employing works out.

But what about Class E? Should the VFR pilot talk to ATC in that airspace? There is technically no requirement for VFR pilots to talk to ATC. But that doesn’t make it a bad idea.

On to the second question. Why would a pilot not want to talk to ATC? When operating near a busy airport, whether the traffic is mostly IFR or VFR, the Tower will likely know what’s going on with the traffic operating in the airspace immediately surrounding the control zone. Incoming IFR arrivals will be in communication with the Tower, or their intentions will be known, as will their estimate for the airport, if not their exact location. They can communicate this

information to you to help you avoid their flight path. Other VFR traffic operating nearby may also be on Tower’s frequency, so they can offer information they have on those aircraft, as well. Similarly, the intentions and flight paths of departing IFR and VFR aircraft will be known to the Tower to help you avoid each other, even if you’re just outside the control zone.

It seems common for a pilot to want to avoid “bothering” ATC — or to not want to bother with them at all. Sometimes a pilot will choose to do something that can be obviously questionable to avoid the call. Long ago, as a newly-licensed pilot, I flew at 3,501 feet over the airport (because the CZ had a ceiling of 3,500 feet), just so I “wouldn’t have to call.”

Later in my life, I would work that same Tower and would see it from the other side and I realize now that I could very easily be in the way of other traffic. Not having communications with an aircraft in conflict with another can be very stressful for controllers and other pilots. Others have flown intentionally below the floor of Class D airspace in terminal areas so as not to bother controllers, but just below. Again, if ATC knows who you are and, more importantly, what you’re doing, it can reduce a lot of problems. Passing traffic to another aircraft saying, “type, altitude, and intentions unknown” uses a lot of radio time when a transmission may not even be spoken if the controller knows what you’re up to and verifies your altitude and intentions. Often, an aircraft that is showing on surveillance systems but the intent is not known forces controllers to take action with another aircraft on approach to an airport since ATC doesn’t know what the aircraft may do. There may be other safety implications, too. For example, there are good odds that anyone squawking

1200 is an aircraft of the “light” wake turbulence category. The majority of aircraft operating under IFR are “medium” or “heavy,” and this can lead to a wake turbulence hazard.

If controllers don’t know the altitude of your aircraft, and don’t know for certain that you won’t climb, clearing a heavier category aircraft directly over you can be a scary thought. This aircraft may be held up well above you or vectored around you to prevent a hazardous situation for you. This may lead to an increased workload for the controller and the other pilots.

I’ve heard that VFR pilots sometimes don’t feel welcome. That’s understandable. Sometimes the controller is busy, and that makes responses terse. Perhaps the controller may be just having a bad day. In the end, the controller’s interest, and the job, is to keep airplanes separated. That’s much harder to do if the pilots involved are not monitoring an ATC frequency in the terminal area around an airport.

This can also be true in enroute airspace. Even just monitoring ATC’s local frequency can be helpful. I recall passing traffic to an IFR aircraft as, “type and altitude unknown, over the Saint John River southbound.” The pilot of that aircraft heard the transmission and immediately checked in, saying, “I might be that traffic.” I confirmed the identity of the target on my screen and, being able to talk to both pilots, was able to pass traffic information and ensure they saw each other and took action to avoid a conflict.

Controllers don’t like the idea of aircraft passing extremely close to each other in an uncontrolled manner. If you check in and you’re potentially one of two (or more) who could tangle, we can help each other stay out of newspaper headlines.

Ithink I’m going to quit my job,” I told my manager at four in the morning in the middle of the week. It was a terrifying claim to make because what if he didn’t understand? What if he couldn’t help me find a solution? What if he didn’t care?

At the time I was working in an “old boys’ club”, somewhere they hadn’t hired new apprentices in nearly a decade, a place where I was one of three women working alongside 35 men. I had moved to a new city, I worked every single weekend (a four-and-three Saturday through Tuesday), and I was on straight nights (9 pm to 7 am). It was winter on the gloomy West Coast, so I hadn’t seen the sun in days. I was overwhelmed, I was exhausted, and I was miserable. And it all came back to one thing: I wanted to quit my job.

At the time, I was still young enough and new enough to aviation that I didn’t fully understand how the industry can take a toll on my state. In school we joked about Aviation Induced Divorce Syndrome, and teased the pilots we knew about taking a Tylenol for a headache because, what if Transport found out and pulled their medical?

Sure, we laugh about these things now, but mental health in aviation really isn’t spoken about as seriously as it should be. Companies will say an employee’s well-being is a priority but still expect them to work a 20-hour shift with little thanks.

I was raised in aviation and oil and grease. Who was I if I wasn’t supposed to be right where I was? But who would I become if my spiral steepened? I didn’t want to quit; I knew that even as the words left my mouth. I just needed — what? A different shift, or a different base, or a different company? I found all three and found that the grass isn’t always greener.

It was an isolating feeling; certain I was alone in my struggle while everyone around me was excelling and thriving. When I met Ben, we discussed how we

both ended up in the industry: I was raised an airline brat whereas his interest stemmed from the copious amounts of planes that covered his ceiling. He was a child with an avid mind driven by the curiosity in how things worked, so he spent his time taking apart toys and typewriters and electronics. We found common ground with how things fell into place for each of us, his thanks to a grade-nine shop teacher and mine to family history: we both liked planes, and mechanics, and planes need mechanics so maybe aviation needed us.

Ben spent 16 years as an AME in the unique world of aerial firefighting

before he began to wonder what else the world could offer him. He loved his job, but he’d unknowingly let it sink into his personal life to an extent he deemed unacceptable. He told me, “It’s hard being your own audience and watching yourself consistently setting fire to everything you own in a search for an answer to a question you don’t understand.”

He had no idea how much I understood.

In an attempt to separate his career from his life, Ben began taking classes for things outside aviation and sought guidance from a mental health counsel-

lor. And then he did what I thought so hard about doing early on in my career; he set down his tools and he walked away.

With his newfound time and freedom, Ben made incredible personal triumphs. He backpacked New Zealand and he cycled across Canada, and then he settled down for classes in psychology, in what he was sure would be a complete career change. But after moving to a new city with no job to fall back on, Ben didn’t find the same passion he’d initially had in aviation.

He realized he still wanted to work in the industry; he just needed a way to reignite that flame. So he spent his time gaining perspective, on aviation, on life, and on himself, and he formed a new understanding of what his career meant to him, and of how he wanted to balance his life.

So Ben returned lighter, more focused,

and adamant about making his career exactly what he wanted. He took parttime work at a hangar in Vernon and continued his classes with a new mindset: that he was okay with whatever happened next.

He completed his first-year classes in psychology and pivoted to a degree path in technology management. Simultaneously (and on opposite sides of the country), he led both the resurrection of a Q400 from an unfortunate engine fire event, and a heavy check on a Q400 that had just come back from storage. In doing so, Ben found acceptance and confidence in who he was in aviation, and these projects provided him a unique opportunity that successfully re-sparked that passion he’d been missing.

Now his curiosity is alive and well, he’s motivated and challenged, and he’s comfortable. He has a newfound respect of what led him to walk away, and

everything that led him back.

After almost 20 years in the industry, not everyone is as fortunate as Ben. Perhaps we should all take a small sabbatical, or accomplish an incredible feat, or spend some time studying the human mind so we can know for certain why we do what we do, so we can understand the importance of prioritizing our mental health.

As for me, I’ve begun branching out and exploring interests outside aviation. While I know for certain anything airplane-related is where I want to be, it’s been liberating to find I can love something else almost as much. I’ve realized when people say, “It’s just a job,” they’re absolutely right; you are so much more than your 9-to-5 (or 5-to-9!) shift.

When you have the same passion and desire as Ben, and you’ve found your optimum balance, you no longer have to go to work: You get to go to work.

NORTHERN ADVENTURES WITH MICHAEL BELLAMY

Articles regarding the shortage of pilots certainly draw a lot of attention from those who always wanted to fly. Perhaps until now, it was just a flight of fancy. Optimism rising, they look to those who have gone through the process to get an honest opinion of what awaits.

Of course, my experience as it applies to larger airlines is very dated and my preference was brought about by the challenges and the autonomy that I relished flying for smaller carriers. With a new commercial licence along with a float endorsement, I then added a little more time by hauling fuel and whatever was needed to small placer mining operations which covered the cost of renting the airplane chisel charter, remembering the term. Looking back, flying time was certainly a prerequisite for employment, but it was also contingent of what contributions to the company’s operation you could make other than flying. Sweeping floors and cleaning toilets comes to mind. Hardly the encouragement recent flight school graduates are looking for.

As hours grew, so did aircraft capabilities and complexities; de Havilland Beavers and Otters, Beech 18s and various twins. I added at that time a Class 1 Instrument Rating. Medevacs and scheds, single-pilot IFR and, due to distances, receiving clearances on HF radios. My first introduction engaging the autopilot for a precision approach was learning that the pilot was required to advise ATC that you would be doing a coupled approach.

A couple of summers were spent fighting forest fires flying Bird Dog and Douglas A-26 Invaders for Air Spray of Red Deer, Alberta. Now who would not enjoy flying a Second World War bomber, with Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engines thundering on either side, fuelled by 145 octane “testosterone” fighting wildfires? Winter had me talking to Canadian Pacific as a Boeing 737 seemed to be the next logical step for me and oth-

ers. However, the repetition of following the same schedule day after day felt more than a bit anticlimactic.

The growing demand for helicopters, especially in the North, and the machines’ abilities intrigued me. The mechanics and complexity of helicopter components are all related, like the inhabitants of some mountain village. The ‘cyclic’ controls pitch and roll, and is familiar to most fixed-wing drivers, similarly the pedals introducing yaw control. The ‘collective’ on the pilot’s left side controls the main rotor pitch, with the throttle incorporated into the grip, like a motorcycle. A short flight in a friend’s Bell Jet Ranger where, for the first time, I tried my hand at the controls found that the dynamics of the flight were similar to a fixed-wing aircraft. The helicopter controls, though, had a remarkable ease and sensitivity to the pilot’s every input, even when it was unintended. How the machine attained forward, lateral and reverse flight, however, was based on the rules of aerodynamics. Once understood, there were always exceptions to the rule.

Cruise flight was comfortable, especially the dramatic view afforded the pilot

once he or she grew accustomed to not having a cowling or wings to reference the horizon. Descending into a large field had me squeezing the seat cushion, watching the airspeed unwind below 40 knots. My instructor’s hands now assumed a more attentive position as we descended into a temporary hover. “Temporary” referred to my frantic attempts that more closely resembled herding sheep with a wheelbarrow. My friend’s laughter had me releasing control to his hands and the 206 obediently became docile and settled to the ground.

Fixed-wing airplanes generally fly from point A to B and job done. Helicopters, however, with their singular ability to hover and, more recently to cruise at a respectable speed, open the door to all manner of applications. Wildlife surveys, mineral exploration, forestry or simply providing an airborne platform for the client to get a better understanding on what their next job is going to entail. This provides the pilot, with the client seated next to them, to be privy to firsthand briefings on all sorts of exclusive professions. The more the pilot learns from this association, he or she is then able to tailor

the flight directly to their needs. This trust and camaraderie quickly lead to where a customer will ask specifically for you, the pilot, which always impresses your opera tions manager.

This close association with the profes sionals that you fly also expands your knowledge in the subtleties of the terrain you once casually overlooked. Listening over the intercom as they discuss observa tions pertaining to their knowledge gives you a complimentary education in all manner of subjects. I once flew an interna tionally esteemed geologist who described the mountains that were floating by. For him and his apprentices, the helicopter became a magical classroom as he described how the tectonic plates formed them, then pointing to an anticline where the crust of the earth buckled under pressure millions of years ago.

Another contract had me flying paleoanthropologists looking for evidence of early hominids. Pointing out a promontory overlooking a suspected ancient watercourse, we landed so they could investigate. With small digging tools they soon uncovered evidence of stone tools and projectile points thousands of years old.

With my past fighting wildfires with tankers and bringing that experience to helicopters brought on a rekindled enthusiasm as I chased fires from British Columbia to Ontario and into the States.

Flying every mission, the pilot of the helicopter is always at the controls being aware of every circumstance affecting the machine, “machine” being the preferred informal substitute for helicopter in use by engineers and pilots alike.

Multiengine helicopters are also quite capable in the IFR category used in offshore commuting to oil rigs platforms. Also in the medevac field, delivering patients to hospital helipads. On a later occasion, studying the Aircraft Flight Manual for an Aérospatiale Alouette and the Emergency Procedures section, boldly labelled in red, had an appealing caveat. “In all cases the pilot will have situational awareness and the procedures that follow describe the degree of urgency ONLY.” You must of course be familiar with the emergency procedures, but as the pilot, you, as pilot in command, make the call.

AEROBATICS WITH LUKE PENNER

In late May 2025, I had the incredible opportunity to immerse myself in a week-long training camp in Algona, Iowa, under the guidance of Pierre Varloteaux, a legend in the aerobatic world. While I’ve spent years training with my coach Aaron McCartan, who has made me the aerobatic pilot I am, the chance to learn from a former top-five pilot in the world was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. This experience not only allowed me to broaden my horizons but also offered a fresh perspective on my training journey.

Pierre brings with him the pedigree of l’Équipe de Voltige, France’s elite

military aerobatic team, renowned for producing some of the finest pilots in the world, including the current two-time consecutive world champion Florent Oddon. With multiple world titles to their name, the team’s legacy is well-established — and Pierre’s own record speaks for itself. He was a member of the gold medal-winning French team at the 2009 World Aerobatic Championship in Silverstone, U.K., and holds numerous domestic medals from France’s fiercely competitive domestic competition scene.

Each day in Algona followed a consistent rhythm: two focused flights,

each around 18 to 20 minutes long, the standard duration at the Unlimited level. While brief on paper, these sessions were anything but easy. Pulling +9 and -7 Gs nearly constantly during each flight demands extreme physical and mental stamina. Any longer and figure quality starts to drop off — not to mention the safety risks of vertigo and fatigue.

The first flight of the day typically featured an unknown sequence Pierre had brought from French competitions. The night before, over dinner, the pilots would gather and study these programs. These weren’t casual practice routines — they were some of the most technical and

demanding sequences I’ve ever flown. And while I’m only in my second season flying Unlimited, I met the challenge head-on and left after the week proud of what I had accomplished.

Pierre’s style during flights was calm and observant. He wouldn’t speak on the radio during the initial run-through of the sequence, just as it would be at a real competition, instead recording his detailed commentary for a thorough post-flight debrief. Once the unknown was flown, we’d work through trouble spots. Several times through the week Pierre found a hole in my armour and we trained those weak spots.

and that felt like a personal milestone.

The second flight of the day was usually focussed on refinement: isolating figures and transitions, working through them until the control inputs were crisp, precise and at the correct cadence for optimal score from the judges. Every session was intense. And every minute counted.

This camp wasn’t just about polishing figures; it was about pushing my limits. Pierre came prepared with sequences more complex than anything I’d flown before, and he had no intention of letting me stay in my comfort zone. One particularly brutal figure involved pushing from an inverted horizontal flight to a vertical up-line with a three-quarter inside snap, ending in a tailslide. The challenge here wasn’t just the technical demands or the high negative Gs — it was flying the snap so cleanly that the airplane exited aerodynamically pure, without any side slip or yaw. By the end of the week, I’d flown it comfortably,

My main goal this season is to earn a spot on the Canadian Unlimited Aerobatic Team that will represent Canada at the 2026 World Aerobatic Championships in Batavia, New York. To do that, I need strong showings at both the Canadian Nationals in August and the U.S. Nationals in September. This camp was one of several key steps toward that goal — and thanks to Pierre, it was also one of the most productive.

Pierre’s coaching style is unmistakably French: blunt, sharp and seasoned with dry humour. But under the edge is a deep well of knowledge, and his observations always cut to the core. I appreciated his expert eye — and the way he challenged me to fly sequences I didn’t think I was ready for, only to show me I was.

The camaraderie at these camps is one of my favourite parts of competition aerobatics. Everyone shows up ready to work, and the egos are left behind in the hangar. We share techniques, push each other and debrief over good meals and plenty of laughs. A highlight

for me was watching my good friend Jesse Mack begin his own Unlimited journey, just as I did last year. Jesse will be making his Unlimited debut at this year’s Canadian Nationals in Steinbach, Manitoba. If both of us, two pilots from Manitoba, end up representing Canada at the Worlds next year, that’ll be something special for our small but proud province.

In past camps, I might have pushed for three flights a day, but Unlimited flying demands a different approach. With the high costs, extreme physical and mental demands, and steep learning curve, it’s smarter to focus on quality over quantity. Two flights per day gave me the intensity I needed without tipping over into diminishing returns.

In all, I left Algona sore, exhausted and inspired. I’m eager to take what I’ve learned and apply it to the next two big tests. Hopefully, by August next year, I’ll be standing on the flightline in Batavia wearing the Canadian colours.

The writer flying in the 2024 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships.

My next article will cover the results of the 2025 Canadian Nationals — so stay tuned.

Visitors to the Cat Lake First Nation, 112 miles northwest of Sioux Lookout, Ontario, often remark on the splendiferous forests surrounding the cluttered village. Since the 1970s, an airstrip has provided access to medical facilities but, brief years before, Cat Lake’s Cree-Ojibway rarely encountered airplanes. On September 3, 1932, however, they watched the dramatic splashdown of a de Havilland DH.61 Giant Moth after starvation and tuberculous overwhelmed their destitute community. Pilot G. P. Hicks and Dr. O’Gorman soon determined only mercy missions could save the severest cases.

“One was a woman who was emaciated and in a poor state of health for some time. In consequence, she was unable to catch enough fish for herself, husband and children,” said Hicks. “The other patient was a boy of seven years who had his right leg broken three weeks previously. His leg was badly discoloured and swollen.”

Hicks and O’Gorman carried the patients to the towering transport for a flight to Sioux Lookout’s hospital. Majestic 10-passenger, 52-foot wingspanned Giant Moth G-CAPG belonged to the Ontario Provincial Air Service (OPAS), which was created March 31, 1924, under the guidance of the renowned Roy W. Maxwell. Expected to patrol timber tracts for fires and forest health, the fleet became recognized worldwide as the “Yellow Birds.” When demands dictated, managers dispatched seaplanes or skiplanes into the Canadian Shield’s sharp-toothed spruce wonderlands to assist the native and non-native populace.

Few aviation enthusiasts know precisely when Canada’s first mercy missions took place. Some historians

suggest the moment an RCAF pilot stuffed a “war-wounded” lieutenant into a Curtiss JN-4 on August 9, 1920. Elsewhere, an Avro 594 Avian pushed 343 miles through clutching -40°C north from Edmonton. The frozen-faced crew carried 600,000 antitoxin units to combat a diphtheria outbreak.

By coincidence, Roy Maxwell himself carried out what aviation aficionados believed to be the first OPAS medical mission or “medevac.” During a treaty trip to distribute James Bay Treaty No. 9 payments to Ojibway and Cree northerners, word came of inadequate medical supplies at a remote post. Although superstitious locals had already shot at his Curtiss HS-2L “Devil Bird” years before, he loaded necessities at Ogoki Post, 141 miles northeast of present-day Geraldton, and “…flew back to English River, dropping the supplies into the river directly in front of the post, and then circled overhead until they saw that the Indians who had put out in canoes had picked up the floating parcels from the water,” reported the Sault (Ste. Marie) Star.

The OPAS devoted hundreds of hours to medical and mercy forays where few commercial air services existed. Some writers described the pilots and aircraft

maintenance engineers (AMEs) as wild adrenaline-seeking adventurers. In reality, these skilled individuals in unstable airborne contrivances took only calculated risks into meagrely mapped hinterlands saturated by blackflies and frostbite.

After his Cat Lake flight, Hicks and G-CAPG departed next day into the same forlorn region to assist in another drama. Word from Osnaburgh House, 101 miles northeast of Sioux Lookout, described the plight of two Ojibway sisters. Like children everywhere, they amused themselves in whatever play they could devise. This time, their brother emerged from the family shelter with a double-barrel shotgun.

In jest, he ordered his playmates to raise their hands and pulled the trigger. Shotgun pellets savaged the siblings horribly. Wood splints and tree sap applied by the parents did nothing. After packing both into a canvas canoe, the father paddled 50 miles overnight to Osnaburgh House where radio communication via the Hudson’s Bay Company summoned Hicks. The stately 525-hp Pratt & Whitney-powered Giant Moth traversed the well-watered aerial pathway and alighted on the boulder-dotted lake. The youngest child, age 11, hem-

orrhaged badly and her 17-year-old sister’s nearly severed arm and punctured chest rendered them comatose. Villagers placed them on the Giant Moth’s floor. In spite of enroute turbulence, both survived. Hick’s cryptic report read, “Air travel only means of giving girls a chance of life.”

The Toronto-based Travel & Publicity Bureau decided to capitalize on what Maxwell’s successor, George P. Ponsford, classified as “flights of a mercy nature.” A Lake Superior tourist resort passed word that a camper had walked 20 miles to a railway station to seek aid for his grievously ill companion. By the time medical officials informed Ponsford, darkness curtailed all airplane activity yet pilot George H. R. Phillips decided to attempt a night flight on August 1, 1931.

“Mr. Phillips flew the doctor in along the rocky shoreline of Lake Superior before the chap who had gone out to communicate with Sault Ste. Marie returned to camp,” said Ponsford. “The doctor attended the sick man who was later returned to hospital in Sault Ste. Marie and Mr. Phillips flew back to base the same night.”

Press coverage said nothing of night flying hazards in a seaplane. The cockpit contained few instruments and wings lacked landing lights. Phillips sensed himself downward with gentle throttle and slow speed until the floats contacted unseen high seas. Damage-free on the roiling surface, Phillips could only guess locations of boulders and tree stumps to avoid crumpling the fragile fuselage. No newspaper described his fatigue; he logged over 160 flying hours the same month.

Besides standbys for public good, OPAS pilots occasionally rescued their own. One DH.60 Moth slammed into the spruce when the weary pilot fell asleep in his cockpit and entered a spin. One tree branch sliced his calf muscles, carried upward and ripped a deep chest gash. Another passed through the opposite leg and skewered him to a tree. Workers from a nearby railway line used a hacksaw blade to free him before

another OPAS pilot brought a nurse to the site.

“The nurse gave him a good slug of morphine, then with four section men and the rest of us breaking trail, we made fast time getting him back to the lakeshore and then took off to the hospital,” wrote the rescue pilot. “The walk through the woods hadn’t helped the little Finnish nurse’s appearance. Her stockings were in shreds, shoes ruined and although her dress needed a visit to the cleaners, she didn’t complain. We took her to dinner.”

The accident pilot went back to work and never again fell asleep at the controls.

Pilots needed resourcefulness as well as skill. Edward C. Burton did not receive a traditional friendly welcome after docking his OPAS Yellow Bird Noorduyn Norseman at a fire tower to deliver food supplies. He found the blood-soaked observer days after an axe deflected into his ankle. Burton sliced off the suffering man’s leather boot to remove the crusted sock, returned to the Norseman and retrieved a sack of flour. Scooping a depression, he inserted the foot and packed flour around the suppurating wound. Later, a Port Arthur doctor informed Burton he had saved a life.

Another outstanding episode caught the attention of peoples of both sides of the Canada-USA border on April 11, 1933. Shifting Lake Superior ice floes provided a theatre-like backdrop when

two American fishermen found themselves stranded far from land. The cast consisted of two pilots already known internationally — Phillips and Maxwell.

“These men (the fishermen) had become isolated on a small ice floe that was liable to break up while drifting out into the stormy waters of Lake Superior,” an OPAS memo explained. “Aircraft were used to find the men and later to direct a rescue boat on observations from the observer. State Department Washington have written in high commendation of assistance rendered.”

In the 100th anniversary year since Maxwell led the organization, the OPAS transformed into the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Instead of obsolete flying boats and gust-prone biplanes, Canadair CL-415 water bombers, helicopters, de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otters and a handful of DHC-2 Mk III Turbo Beavers wear the yellow scheme. On the same site as the original 1924 hangar, Sault Ste. Marie’s Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre files contain yellowed pages replete with tales of bowel obstructions, shattered limbs, ruptured appendices and many others. Many situations called for bush planes dispatched into malevolent muskeg or shallow sand bars regardless of citizenship, language or native reserve.

The Centre’s staff have accepted a mission to preserve and show the heritage of the pioneering “adrenaline-seeking adventurers” who saved or comforted the injured and ill.

LANDING BACK AT THE DEPARTING AIRPORT WAS NOT AN OPTION

How long do you want to fly with one door unlatched?” That was the response I gave to one of my students who had recently bought a nicely equipped twin-engine Piper Aerostar and was trying to figure out how to adjust his personal minimums.

An extra engine does change the risk management equation. The odds of an untimely off-airport landing are reduced significantly. Flying in instrument meteorological conditions and over unfriendly environments becomes safer. On that day, the weather was bad enough that landing back at the departing airport was not an option as the conditions were below approach minimums. It was not an option either for more than one hundred miles.

My student had bought the aircraft to commute to Florida where he had a second residence. He knew that the weather usually improves going south and that he could potentially fly to better weather with one engine.

Spending time in the sun was very enticing. That is why he was asking me if I would take off for Florida under these circumstances. However, I did not gave him an answer. Instead, I started asking questions to raise his awareness of all the risks and help him decide for himself which one he would want to tackle and which one it did not, and why.

Truth be told, my personal minimums vary from ‘never again’ to ‘never’ to ‘it depends” and are, well, personal. It would not come to my mind to encourage anyone just to adopt them mindlessly.

Flying is inherently risky as are many things we do every day. To increase our chances to live another day, risk assessment is a prerequisite to making any move. While we routinely assess risk in our daily earthbound life, in aviation, the exercise tends to be more deliberate and thoughtful.

Far too often, though, we talk

about risk management in a vacuum — without addressing the benefits of taking risks. Only fools take risks without regard to benefits. It is the palatable benefits that lead us to accept risk.

To take a calculated risk, we must not only understand what the risk is, we must go one step further and weigh it against the benefits. In aviation, we tend to stop at identifying risks and evaluating our technical abilities to deal with them.

Pilots love to fly. Each flight comes with at least one benefit for us — to be airborne. How much risk is that benefit worth? Well, let me put it this way. Few of us hesitate to take a well-maintained machine thousands of feet above the Earth on a beautiful sunny day.

Risks, per se, rarely kill; it is the overzealous quest for their associated rewards that does. For example, the well-known get-home-itis syndrome is not necessarily grounded in the failure

to identify the risks. It usually stems from an overvaluation of the benefits. To put it in another way: a pilot suffering from the syndrome thinks that the risks are worth it.

Developing a set of ‘canned’ personal minimums outside of the context of benefits may not be as effective at protecting us from making bad decisions as we would expect. A better technique consists of setting up an enticing scenario before considering potential risks and formulating personal minimums.

My student could already see himself and his family working on a suntan on the beaches of Florida and knew that he owned an aircraft capable of flying hundreds of miles on a single engine effortlessly. So, I helped him work through scenarios when nothing was at stake yet.

What if the door came unlatched just after liftoff and he could not land for hundreds of miles to close it properly? Would the potential advantages of taking off without delays instead

“Establishing realistic personal minimums is a necessity to expedite and improve the decisionmaking process, but it is not infallible.”

of waiting for improvements worth everyone's discomfort? If the potential rewards were worth some discomfort, then the next question would be, how much and for how long? Thirty minutes at -15° C? One hour at +15° C? His answers would define some of his personal minimums during instances of low instrument conditions at the departing airport.

Establishing realistic personal minimums is a necessity to expedite and improve the decision-making process, but it is not infallible.

Take, for example, fire. From an early age we learn to avoid it at all cost to ensure our survival. Nobody in their right mind would run into a fire without

proper equipment. Good Samaritans, however, do it on a regular basis — but to save someone else’s life.

That human trait may, under extreme circumstances, lead us to act instinctively. It is not to be underestimated because it can affect the most conservative of pilots.

Just imagine how hard it would be to abide by your strict personal minimums should the life of one of your passengers, or your own, be at stake. Suddenly, flying an approach down to minimums — maybe even a little lower — might not sound that bad.

Testing personal minimums against realistic reward scenarios will help validate them against emotional pulls and make them more potent inhibitors should circumstances challenge their relevance. Without such level of due diligence, developing personal minimums is just a futile intellectual exercise with little safety enhancement value.

CANADIAN AVIATION CONFERENCE AND TRADESHOW 2025

A major Industry Networking Event not to be missed!

ATAC’s Canadian Aviation Conference and Tradeshow is the premier national gathering offering Canada’s best networking, learning, and sales opportunity for operators, suppliers, and government stakeholders involved in commercial aviation and flight training in Canada.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 18 TO THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 20

FAIRMONT QUEEN ELIZABETH HOTEL, MONTREAL, QC

For more information contact: tradeshow@atac.ca www.atac.ca

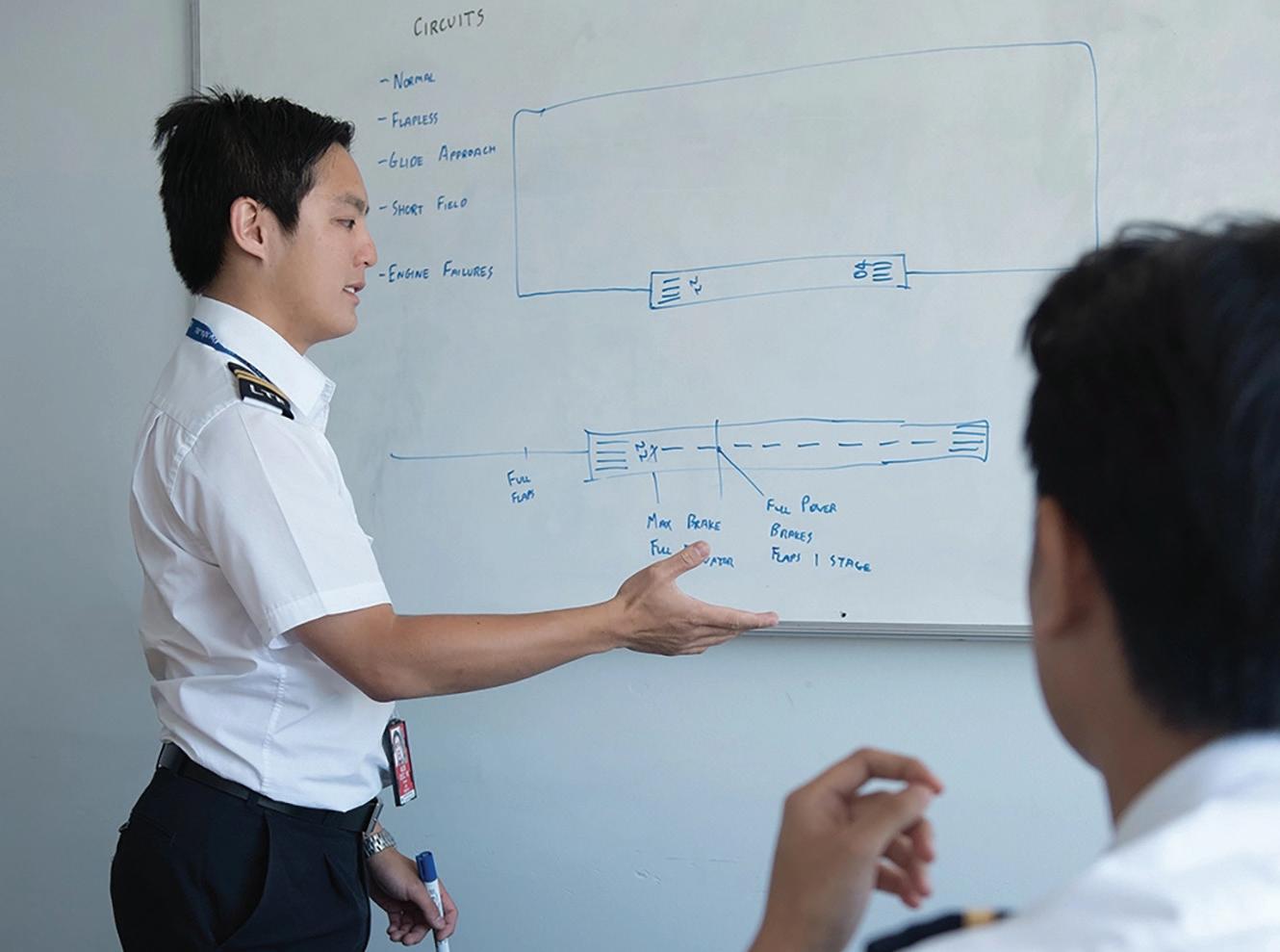

Transport Canada (TC) sets the knowledge requirements for schools that teach students to fly. Their standards also identify the subject matter that students need to know to prepare for their written examinations. For private pilot licence (PPL) candidates, the document which lays out that guidance is referred to as the Study and Reference Guide for Written Examinations for the Private Pilot Licence (Aeroplane), also known as TP12880. For the first time in a while, the document has been updated, its new version having been posted for viewing in the late spring of 2025. For those at TC tasked with undertaking the

update, it was no small process, and a lot in the new document has changed from the old. As always, Air Law, Navigation, Meteorology and Aeronautics (General Knowledge) are the sections from which students have to know their stuff. Below is a summary of some of the things PPL students are, henceforth, expected to know, as well as some of the long-established curriculum items that TC no longer prioritizes.

Students often state that Air Law is the toughest subject to know, a sentiment that is founded in its propensity for being the driest topic to learn. But, of course, pilots need to

know the law. And TC has added a few regulations of which they want pilots to be better aware. This includes sections of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) related to Registration of Aircraft (CAR 202.13), Qualifications to be a Registered Aircraft Owner (CAR 202.15), Transfer of Legal Custody and Control of Canadian Registered Aircraft (CAR 202.35), and Conditions for Cancelling a Certificate of Registration (CAR 202.57). Furthermore, the laws related to Reimbursement of Costs of a Flight (CAR 401.28), and Medical Certificate Requirements (CAR 404.10) are now identified as “need to know”

subjects. Possession of Hand-held Lasers (CAR 601.19), Language Used in Aeronautical Radiocommunications (CAR 602.133), Requesting Air Traffic Services (CAR 602.134) and Aircraft Equipment Standards and Serviceability (CAR 605.06) are now also on the TP12880 hit parade. It’s not inspirational reading, but TC wants students to know this additional regulatory material to pass their exam.

Under the section for Navigation, TC has added its desire to have pilots know about Aeronautical Information Publication Supplements (AIP SUP) as another source to ensure that they have all the information pertinent to a flight. TC is also looking to ensure that students know about Electronic Flight Bags and Portable Electronic Devices. The latter, of course, have been around as cockpit aids for a while now, but TC is now recognizing them as standard cockpit items and, as such, are wanting to test students on their knowledge of their basic principles of use, their limitations and the sources that power them. So too does TC want to ensure that students know how best to manage the distractions, and fire hazards, that these devices can engender. Also under Navigation, Automatic Dependent Surveillance — Broadcast (ADS-B) has been added as a topic for students to now be fluently brushed up on, as have Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS). What’s been removed from required Navigation knowledge is: VHF Omnidirectional Range (VOR), Automatic Direction Finder (ADF), VHF Direction Finding (DF) Assistance, and Airport Surveillance Radar (ASR).

Not much changes in the study of Meteorology, so TC knowledge requirements are representatively stable. Where they do want students to show significantly broader knowledge is in hazards that are, perhaps, increasingly associated to climate change: hurricanes, tornados, forest fires and dust devils. Under the topic of Meteorological Services Available to Pilots, the Collaborative Flight Planning Service (CFPS) — Nav Canada’s new internet

“Though the jury may still be out on how long it will be before electric aeroplanes are humming around Canadian skies, TC is turning its attention to electric motors and batteries; they want students to have some knowledge on their operation.”

flight planning system — is now another “must know” to manage flight planning. New automated weather reporting equipment in the form of Limited Weather Information Systems (LWIS) and Automated Weather Systems (AUTO) are newly listed, as are Upper Winds and Temperature Forecasts (FB). What’s gone from Meteorology knowledge requirements includes Pilot’s Automatic Telephone Weather Answering Service (PATWAS) and Nav Canada’s Aviation Weather Web Site (AWWS) which has been replaced by CFPS.

Though the jury may still be out on how long it will be before electric aeroplanes are humming around Canadian skies, TC is turning its attention to electric motors and batteries; they want students to have some knowledge on their operation. Also, fuel and fuel system considerations in winter are newly added to TP12880 in the Aeronautics (General Knowledge) section. Also newly found in the document are the topics of roll upset, aerodynamic effects of airborne icing, Electronic Flight Instrument Systems (EFIS) and their

associated principles of operation, their errors and limitations and their power sources. Under the topic of Flight Operations, students need to know about displaced thresholds, porpoising, reference landing speeds (Vref), external loads, maximum landing weight, zero fuel calculations and types of critical surface contamination ice.

Finally, under the Aeronautics (General Knowledge) subsection of Human Factors, it’s now time for students to brush up on visual references, individual health and fitness, fasting, substance use (as opposed to abuse), effects of smoking and vaping, threat and error management, hazardous attitudes, interaction with automation, GPS moving maps, communication with ground personnel, family relationship pressures, peer group pressures and goal conflicts.

All of this is what TC says students should now know. Maybe every pilot should dip into this subject matter too. If it’s important to the pilots of tomorrow, then it should be just as equally important to the pilots of today.

On Friday June 6, 2025, I attended a Celebration of Life for Tony Swain (1934-2025) at the Billy Bishop Legion, located near Kitsilano Beach in Vancouver. This British-style pub is filled with aviation photos and memorabilia. It was a fitting location for Tony’s sendoff as it was his “local.” For many decades he lived just down the street from this watering hole. The event was well attended by his family, friends and fellow aviators. A lone “Harvard” flew overhead as a tribute to Tony’s final flight “west.”

I remember the first time I met Tony and his wife, “The Mary,” in the mid-1990s. He always referred to

Mary in this affectionate manner. It was at a raucous town hall meeting in South Delta in the greater Vancouver area. I was attending the meeting on behalf of Transport Canada to ascertain the facts associated with local demands to shut down the Delta Heritage Airpark (CAK3). This 2600foot “grassroots” aerodrome is located south of Vancouver on the shores of Boundary Bay and is adjacent to the larger Boundary Bay Airport (CZBB). There were allegations by local residents that the Delta aviators were deliberately harassing their neighbours by flying low over their homes and disturbing their quality of life. Tony

and Mary were foremost among the defenders of the airpark and its tenants. After a prolonged investigation and negotiations with neighbours, the airpark was subsequently saved from closure. The successful efforts to save the airpark may, to a large extent, be attributed to the leadership of Tony Swain.

Tony’s early boyhood was in Hull, Yorkshire, England, where he experienced Second World War air raids. I remember him describing a lowlevel strafing run down the street that he lived on, and this incident made a lasting impression on the little boy. This occurrence may have been the trigger

that subsequently found him, in the early 1950s, enlisting for pilot training in the Royal Air Force. A portion of his advanced training was with the RCAF in Western Canada on Harvard and Lockheed T-33 aircraft.

Due to a health issue, he did not continue with a career in the RAF but, subsequently, in 1956, he emigrated to Canada as an aeronautical engineering draughtsman. He initially resided in Alberta but eventually found his way to the West Coast where he met “The Mary,” who ran a fish shop in West Vancouver. They married and were an amazing team for 44 years. Their initial common interests were in the yachting community; however, they progressed to the aviation genre when the couple bought a surplus Harvard airplane that they dubbed “Bessy.” The airplane also displayed nose art of a comely female fish, which they dubbed the “Fish Lady.”

you could hear Tony telling aviation stories and touting the benefits of the General Aviation community.

“The couple were tremendous ambassadors for the aviation genre and were recognized far and wide. They touched the lives of both aviators and non-aviators.”

The couple were tremendous ambassadors for the aviation genre and were recognized far and wide. They touched the lives of both aviators and non-aviators. They never missed a chance for a formation flyover and were especially prominent during Remembrance Day ceremonies. The roar of their formation’s Second World War-era Pratt & Whitney 1340 engines brought many a tear to those attending the cenotaphs that they flew over every year. As they progressed in years, they eventually sold their beloved Bessy that they had owned from 1971 to 2005 (34 years).

Tony belonged to several yachting, racing and aviation organizations. The aviation groups that he was most prominent in were the Western Warbirds Association and the Canadian Owners and Pilots Association (COPA). For many years, Tony was the COPA director for British Columbia and the Yukon. He dubbed himself the “COPA Guy” and wrote a monthly column, “The Pacific Perspective,” in the COPA newspaper. Aviators from all over Canada couldn’t wait to read the next edition of the newspaper to find out what Tony and The Mary’s next escapade would be.

The couple flew Bessy all over Western Canada and the United States, attending many, many aviation functions. They also travelled all over Canada in his role as a COPA director. Tony had a booming voice and had a distinctive Yorkshire accent. He was a great raconteur and at most functions

The aircraft was sold to the Canadian Harvard Aircraft Association based in Tillsonburg, Ontario. The aircraft still regularly flies at airshows and other events and, while she has a new paint scheme, she still bears the name “Bessy” and sports the nose art of The Fish Lady on her cowling. Tony and The Mary were so proud that she continued to fly and carry on their legacy.

When Mary passed away in 2013 there was a very large gathering at the Delta Air Park and the attendees were so generous in their donations that an annual scholarship, administered by the British Columbia Aviation Council, was established in Mary’s name for young women entering the field of aviation. Mary’s scholarship continues to this day. About 10 years after our first meeting, I became a partner in a little aircraft that was based at the Delta Airpark, and I got to know and appreciate this couple and realize how great their impact was on Canada’s aviation community. I was proud to be called their friend.

Tony, as you fly west on your last trip to join The Mary, I wish you the old bush pilot’s blessing: May you have tight floats and tailwinds.

REVIEW BY RENÉ R. GADACZ

BY S.C. GWYNNE