6 /

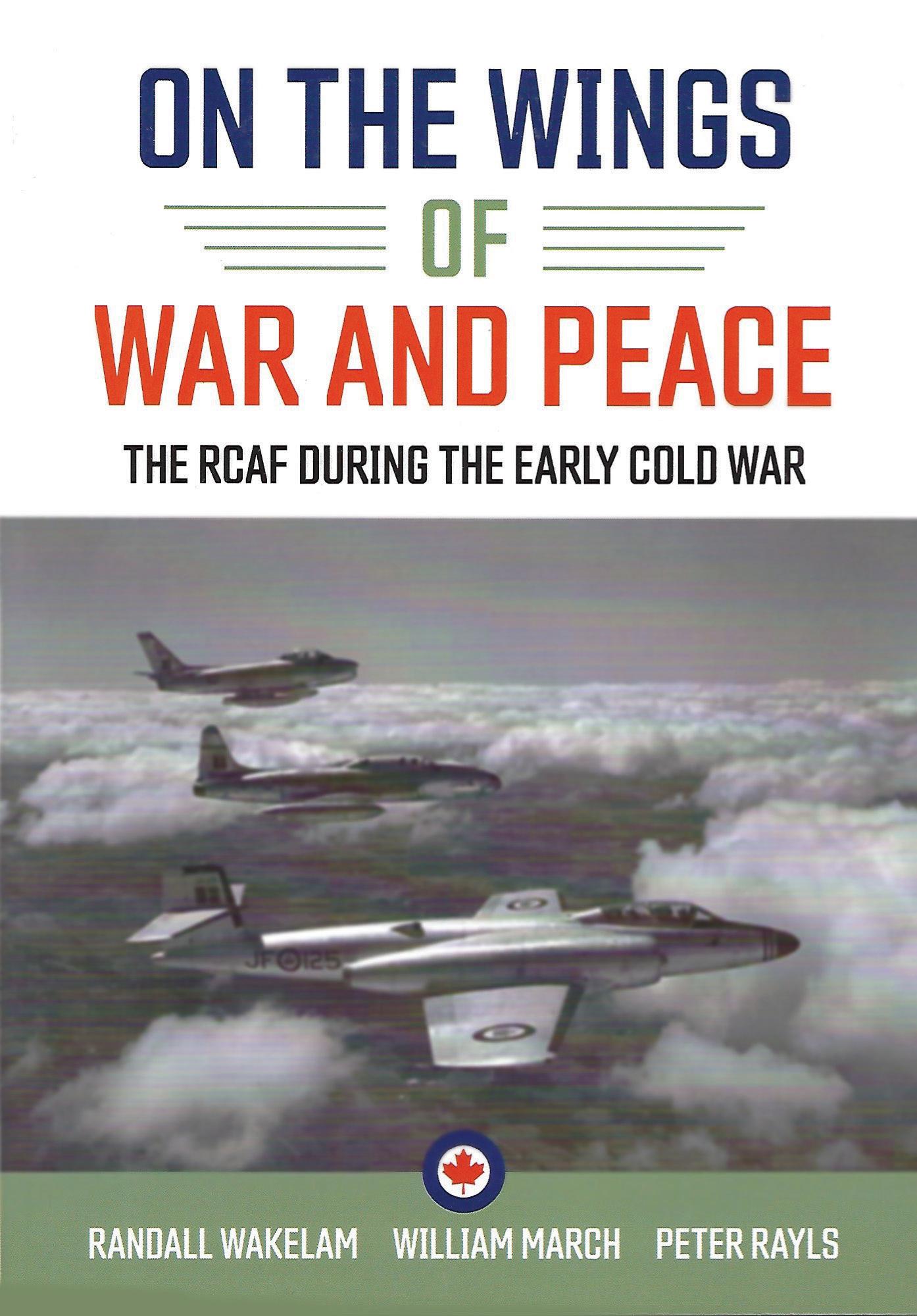

While the RCAF is now over 100 years old, this country fielded great aviators and heroes in the First World War. By Nathanael Reed

Canada joins the United Kingdom, Finland, Norway, Poland and the United States in aerial combat training. By Remco Stalenhoef & Patrick Smitshoe My long-held boyhood dream came true.

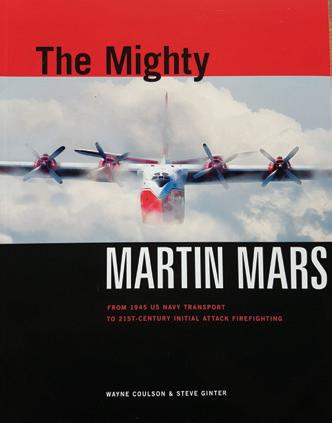

The founder of this magazine, Jack Schofield, continues to not only entertain us with stories of his exploits on, and above, the British Columbia coast in decades past, he also serves as a chronicler of aviation events of historical significance. In his current installment, Jack tells us about the time when the fleet of four Martin Mars flying boats, replete with US Navy livery, arrived in Victoria in 1959-60, property of a consortium of B.C. lumber companies. Jack was there.

Last issue, René R. Gadacz came on board as a book reviewer. His love of words is such that he now helps out with the copyediting of the raw material we receive since I took on other, nonediting activities. I’ve made René Associate Editor (making me Editorin-Chief, I guess).

We consider rotary flight worthy of coverage in this magazine, although contributions on that subject matter are scarce. Nevertheless, two of our regular columnists, Tim Cole and Robert ‘Bob’ Grant, chose to write about their helicopter experiences in this issue. Bob loved the experience so much he went way overboard in the word count. But if you’re like me, you never get bored with what Bob writes. Be sure to read both columns.

This issue also sees double the number of columns about aerobatic flight. Luke Penner continues to write about his and his teammates’ ever-increasing presence and success in world championship aerobatic competitions, doing Canada proud. And now that our Expert Pilot columnist Richard Pittet has retired from his stellar airline career, most recently as a captain on Boeing 787s, he has chosen to write

about the aerobatic training he received as an RCAF aviator and more recently taking up the sport in a Pitts S-2C. See why he thinks we all should learn to perform aerobatic manoeuvres and become better pilots for it.

Finally, a word about a feature I introduced to this magazine several years ago. I’ve always loved crossword puzzles, especially creating them. It’s not as hard as you might think, as there are software programs that make it easier. What’s difficult, however, is dreaming up new themes: I’m slowly running out of ideas. It’s hard to gauge how many of our readers take on the challenge, but I know of at least one subscriber who attempts every one of them — he often emails me for an additional clue or two. Let me know if there are others out there who want me to continue.

I look forward to each issue of Canadian Aviator and I’m never disappointed. The Nov/Dec magazine is especially good.

As a recently retired veteran of 30 years with Cathay Pacific, I can vouch for the accuracy of Graeme Peppler’s article. Transitioning down from an Airbus A350-1000 to a Cessna 206 has certainly had its moments.

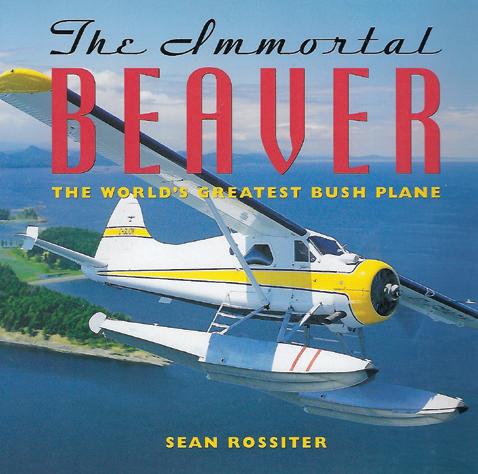

The Mars feature was beautifully done, Richard Pittet never disappoints, and the new bookshelf feature is a master stroke. Your magazine is going from strength to strength. Keep up the great work.

Martin Baggaley, Courtenay, B.C.

Your mag has a great way of taking me back. I played trumpet in Canada’s Marching Ambassadors 2nd Armoured Divisional Signals Regiment in the early 50s, and we wore scarlet and black pants, with spurs on our shoes no less. I used this button stick on brass buttons and you had to make sure you passed inspection, or you went on detail!

Bob Bradley, Surrey, B.C.

I enjoyed reading the article “A Journey Down Memory Airways” (Cole’s Notes, Sep/Oct 2024). It reminded me of a trip that a group of us took in the late 1970s to visit the airplane and war museums in Ottawa. One of the lads suggested we take part in the trial program of intercity service between Montreal and Ottawa. Air Canada had a subsidiary named Air Transit (not Air Transat) where they flew DHC-6 Twin Otters from the parking lot at the Olympic site to Ottawa. The airfare was slightly more expensive and so included our flight from Toronto to Montreal on a DC-8 Super Sixty, which was a beautiful comfortable flight, and then a shuttle bus to Air Transit. As we boarded the Twin Otter, we noticed that the female flight attendant was in a [bad] mood. She had no smiles and spoke to no-one. One of the fellows suggested that she was being punished for something and put on this route. The pilots were happy and friendly as they were able to pilot an airplane without automation. “Miss Grumpy” had to hoist the small ladder and close the door manually and then sat in her seat with arms folded in disgust. All of us were having a good flight seeing the terrain at the lower altitude. Midway the pilot pulled back the curtain and said with a smile, “You have to bring your own coffee on this trip” and raised his thermos. We landed in Ottawa and thanked the pilots for a great flight. All of us had an enjoyable trip, except for the flight attendant.

Mike Sisko, Toronto, Ont.

Your comments (Walkaround, Nov/Dec 2024) struck a chord as they infer that few members in society now read books — or in fact anything written on paper. To this lament could be added the fact that schools have not been teaching students how to write for decades. To see the evidence of this, it is only necessary to observe people of various ages holding a pen or pencil as if it were a shovel.

Not reading books, newspapers, et al deprives people of the opportunity to learn from others. The disinclination to write robs people of the chance to develop their thoughts and ideas and to effectively communicate them and hopefully engage in correspondence with others. There is a societal price being paid for these diminishing attributes.

However, the good news is that your team now includes someone [René Gadacz] who will take the time to read and review the books submitted to The Aviator’s Bookshelf David Green, Thornhill, Ont.

When I read [about the SAR exercise in Waypoints (Sep/Oct 2024)] that the emergency was a plane crash at a rural airstrip 20 kms to the east of Courtenay, I began a little “LOL” but did need to confirm my suspicion. By my reckoning that puts the airstrip slap bang in the middle of the Georgia Strait between Vancouver and Texada Islands.

Richard ‘Buzz’ Bennett, Gibsons, B.C.

Canadian Aviator welcomes reader letters on topics of concern to Canadian pilots and the aviation industry. Please be brief, to the point and polite in your submissions.

Email the editor steve@canadianaviator.com

In the market for a new headset? Wanting to upgrade to active noise reduction technology but discouraged by the high prices of the major brands? Regina, Saskatchewan’s Prairie Flying Service is the exclusive Canadian distributor of the Q Set Aviator line of headsets, both passive noise reduction (PNR) and active noise reduction (ANR) models. They claim that the quality of their Q Set headsets match those of the major brands, but at much lower prices. Made with carbon-fibre, they weigh in at only 290 grams (10 ounces). Equipped with Bluetooth technology, the volume of a paired device can be controlled separately from the radio feed. Helmet and helicopter models are also available. About $720.

Feeling guilty about tossing your fuel sample onto the ground?

Learn more at aviationheadsets.ca. Available from select dealers across Canada.

Do you struggle to see forward when taxiing your taildragger? Do you have to resort to weaving side to side in order to ensure the way is clear? Or worse, have you strayed off your intended path and ended up in an embarrassing situation? Well, the solution may be at hand. Radiant Technology of Wichita, Kansas brings to the market their Taxi Camera which, when mounted correctly, provides a view straight ahead of your aircraft, allowing you to see what you couldn’t before. Included is a high-resolution LCD display which folds into a case when it is not in use. The small camera can be mounted on the wing. About U$400.

Learn more at, and available from, radiantinstruments.com.

Concerned about adding more lead into the environment? A 1990 study in the U.S. revealed that over 3 million gallons of AvGas are poured into the environment — each year! Not only is it a waste of money, but it is also very harmful to the environment. Aviation Specialties offers its GATS Fuel Tester that separates water and other contaminants from the sample, allowing pure fuel to be returned to the tank. About C$30.

Learn more at, and available from, aircraftspruce.ca

Also available from Radiant Technology is a carbon monoxide detector that is much smaller than typical detectors. The Geiger PLUS sounds an audible alert at around 41 ppm of CO, rising to an “insistent tone” at around 100 ppm. The key-fob-sized device is powered by an internal, USB-rechargeable battery that provides around six hours of service and takes about 30 minutes to recharge. The Geiger PLUS, meant to be attached to a keychain, meets FAApublished guidelines for CO detection. Bonus — the device also detects exhaust and gasoline fumes. About C$150. Learn more at radiantinstruments.com. Available from aircraftspruce.ca.

Pilots training on CAE’s multimillion-dollar high fidelity simulators may soon be able to take homework away with them thanks to the integration of a popular augmented reality (AR) system. CAE’s Director of Incubation Eric Fortin and his outsidethe-box thinkers have written software to integrate Apple Vision Pro with its simulator systems and the result is a high-resolution electronic rendition of a Bombardier Global 7500 flight deck.

“The Apple Vision Pro app developed by CAE will allow pilots to familiarize themselves with the flight deck, practice critical procedures and develop muscle memory for key functions from anywhere,” CAE said in

a news release. After fitting the goggles and calibrating them for the trainee’s eye and hand movements, they can run through procedures and call up information on virtual screens to learn control and instrument layout and location. It’s remarkably realistic, from moving the joystick to operating the mechanical switches on the overhead panel. The toggles have to be pulled out before the can be moved up or down and the system mimics that complex movement.

“The resolution is so high you can feel as if you are on the real flight deck,” said Fortin. He said that to be valuable, the system had to allow trainees to interact with the controls

and screens with “natural gestures” as if they were in a real flight deck. “For us, the goal is to empower the learner,” he said.

The system is still under development, but it has been deployed to pilots and instructors to gather feedback and to spot any glitches. The initial plan is to use AR to supplement the simulator training but, as the system is developed and improved, it could potentially be integrated into training curricula. The Global 7500, which has a state-of-the-art Vision Cockpit and Rockwell Collins avionics, is the test bed for the AR system, but Fortin said it can be adapted to any flight deck.

Bombardier’s new flagship business jet, the Global 8000, has entered serial production at the company’s new factory at Pearson International Airport and first deliveries are expected by the middle of 2025. In an update at NBAABACE in Las Vegas, virtually the entire C-suite was on hand to celebrate the rebirth of the company, which was on the ropes financially five years ago when it decided to sell off all its business units and pin its whole future on the big bizjet market.

CEO Eric Martel told a packed news conference that company revenues topped $5 billion this year and will increase to $8 billion by 2030. With a large backlog for both its Global and Challenger lines, Bombardier is greatly expanding its maintenance and repair network and much of the growth over the

next five years will come from that sector.

The new Globals are not only spacious and luxurious, they are also among the fastest civilian aircraft on the market with cruise speeds above Mach 0.9. They also have among the longest ranges of any bizjets and can reach virtually any point on Earth from any point on Earth nonstop.

To amplify that performance, Bombardier’s demo Global 7500 has been setting city pair records on dozens of flights. The platform has set so many of those records (60) that it has, in fact, set a record for setting records.

Amy Marino Spowart, president of the National Aeronautic Association, which keeps track of aviation records, was on hand to present certificates for the latest tranche of records, including the one for setting the most records.

HANGAR TALK WITH JACK SCHOFIELD

Some great British Columbia aviation history now resides at the B.C. Aviation Museum at Victoria airport where the Hawaii Mars has become a static display — those magnificent radial engines have roared for the very last time.

The Philippine Mars as it appeared before being sold to the Forest Industry Flying Tankers consortium of B.C. This is the last Martin Mars to fly, by now having been delivered to the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.

I am sure you will want to go there to view this behemoth. Perhaps even some of you young Boeing 777 captains may even be interested in the history of the craft. This very magazine ran several stories about them when the four Martin Mars flying boats first arrived. Guess who was left with all the early photos taken when Fairey Aviation converted each of them to a waterbomber right here at Victoria airport? How fitting that one of these beauties should return to where the waterbomber concept was born.

Dan McIvor was the pilot responsible for saving that fleet of Mars from the wrecker’s axe. In the early days he loaded water bags which he would then drop on fires from a Grumman Goose. “There’s got to be a better way,” he said and, when he heard that the US Navy was about to scrap the fleet of these famous flying boats, he ditched the bags and flew off to the Alameda Naval Base in California. Dan did not arrive in time. The US Navy had disposed of the aircraft. Dan hurried to the scrap merchant and offered him one hundred thousand bucks for the lot. “Sold,” said the scrap merchant. I have no idea how Dan had managed this purchase. He must have had the nod from the 13 corporate members of the forest industry who were logging B.C. at the time and who quickly formed the Forest Industry Flying Tankers to operate this amazing idea of aerial application for forest fire control.

While Dan McIvor was busy flying each aircraft from Alameda to Patricia Bay, Fairey Aviation, who had developed a modification to allow the Mars to take on water while on the step for takeoff, were transforming the big guys into waterbombers — no more paper bags. Dan told me in an interview that his only regret was that the forest giants wouldn’t buy all the spare engines from the US Navy even though the USN gave them a million dollars’ worth of spares for the aircraft. “The Navy was asking $300 each for about 30 of the spare engines,” he exclaimed.

The US Navy base at Alameda was delighted to know their very famous flying boats would once again be in the air. They were beloved for their amazing service during the Pacific War at which time they flew troops in and the wounded out, back-to-back, for the duration.

During the performance of this modification work on these great aircraft, Victoria airport suffered the blast from Typhoon Freda and the Caroline Mars was blown across the tarmac and damaged beyond repair.

Wouldn’t you love to have been the paint salesman when they bought all that red and white paint? Soon the remaining three, in their famous colours, were on the job.

I recall Dan McIvor’s last comment during that interview when he remembered going out to the scene of a fast-moving forest fire. “We just flew in and put it out,” he said with satisfaction.

In the early 1980s I was employed as a Civil Aviation Inspector in Transport Canada’s Pacific Region, filling the role of an Aerodromes Inspector. While most of my work was associated with fixed-wing operations (e.g., airports, aerodromes and seaplane operations), there was also a significant amount of work associated with helicopters. This included developing and licensing (now called certification) of heliports, authorizing aerial work in urban areas and issuing permits for one-off landings like the annual arrival of Santa at local shopping malls.

At that time I was an experienced fixed-wing pilot with about 6,000 hours flying in light twin-engine airplanes that included Twin Otters, King Airs, the Grumman Goose, Beavers, Otters and a variety of Cessnas and Pipers. In my previous employment I had significant experience servicing helicopter operations by carrying fuel and supplies to remote locations, even spending the odd night in a helicopter camp. However, I had virtually no experience with flying helicopters, with their operating parameters and limitations.

As these duties, mentioned above, were in my job description, I applied

for helicopter training and was initially approved for the 25-hour conversion course for a private rotary pilot licence. In subsequent years, I went on to obtain my commercial helicopter licence and added several other helicopter types to my repertoire.

My initial training was taken with Transwest Helicopters at Pitt Meadows airport, located in Metro Vancouver. There were a number of milestones during that initial training that stick

in my memory and the first three that come to mind were my first flight in the Bell 47, my first solo and training lessons in ‘confined areas.’

After the preflight that is so much more comprehensive than a fixed-wing walk-around, my instructor, Lyle Watts, took me out to a large, open ten-acre field. He demonstrated what the helicopter could do and explained the controls and the coordination required to hover the aircraft. He then gave me control and instructed me to hover. Well, all hell broke loose. Here I was in a 10acre field, large enough to land a Beaver and I couldn’t keep this bucking bronco steady within the boundaries. What a lesson in how wobbly a helicopter is. I thought I could walk and chew gum at the same time.

Gradually, with much sweat and perseverance and with Lyle’s patient guidance, things settled down and eventually, with several lessons under

my belt, I was not only able to hover and carry out other manoeuvres, but do so with precision. What I learned was that, while an airplane is designed to be stable and usually, if you relax and let go of the controls such as in straight and level flight, the aircraft will pretty much continue on its way. A helicopter is inherently unstable and, for every movement of a control, a coordinated and compensating movement is required from other controls. The analogy that I like to use when describing flying an airplane versus a helicopter is that it’s like the difference between walking and swimming; you use your hands, feet and motor skills in a totally different manner in either activity.

Almost 20 years after my first solo in an airplane, I soloed the little Bell helicopter in that same field in which I first tried to hover. It went really well and I felt I had accomplished something that overshadowed that other flight so many years ago.

As my training progressed through all the required manoeuvres, including simulated engine failures that require autorotations, as well as other challenges, the most memorable training took place in confined spaces. Helicopter pilots often work in very close proximity to trees, structures and other types of natural and human-made hazards, more so than their fixed wing

colleagues. I vividly remember making approaches into and departures from tiny clearings in the trees and always having to be conscious of the fact that my rotors and tail rotor were often only a few feet away from contact with a solid object. The slightest wrong move at the controls would result in a rotor or tail rotor strike that would damage the machine and/or cause injury, even death. Never in my career as a fixedwing pilot, even on the darkest nights

in severe weather on an instrument landing approach, did I have such mental concentration, telling myself to relax and coordinate my controls to avoid catastrophe.

Over the years I obtained helicopter skills that included mountain flying, night operations and instrument flight. While I thoroughly enjoyed flying helicopters, I did not take it up as a vocation and remained in the fixed-wing genre. However, my work with Transport Canada kept me associated with helicopters and the helicopter industry for many years. I was fortunate in being able to assist in the development of heliport standards, develop heliports, authorize special helicopter events and, in my later years, to manage two Canadian Coast Guard helicopter bases in Victoria and Prince Rupert. All this was made possible by the knowledge I obtained by gaining my helicopter licences and the intense associated training that was involved.

One of my regrets, I must confess, is that I did not get the opportunity to fly a helicopter on floats.

May you have tight floats and tailwinds.

SWINGING WRENCHES WITH LIANA BUESSECKER

Some of the most exciting moments of my career are likely what was a terrifying moment for someone else, whether passenger or pilot.

One of the most memorable projects I’ve worked on was a plane that had a bird strike with an entire flock of snow geese. Both engines continued to meet performance criteria, so the flight did not turn back. We prepared for its arrival with the understanding that the damage was negligible. Of all the things we imagined might have happened, it was worse. We replaced all the propeller blades, one engine, multiple leading

edges and the radome. Several spots along the fuselage required sheet metal repair, and interior avionics and circuit breakers required extensive cleaning.

I learned a lot about planes that night: namely, just how many things can be damaged with the aircraft continuing to operate as required. It was during this time I also learned I was an ideal bird-strike-inspection-size, fitting as I did inside the intake of the de Havilland DHC-8 Q400.

Another unique moment I’ve had the opportunity of dealing with on more than one occasion is a shattered windscreen. Aircraft windscreens are

comprised of multiple layers of glass so typically it’s only one pane that sustains damage and therefore the aircraft is not in any imminent danger. Often the windscreen heat is to blame, and I’ve formed a habit of carefully inspecting the cracking to determine where the burn began.

Recently I had the experience of being onboard an aircraft that suffered a shattered windscreen in flight. In the cockpit at 25,000 feet, a glow in the window is the last thing any pilot or mechanic wants to notice. I was expecting something far more terrifying than the few “pops” that caused us to

jump in our seats when the glass broke, but that was it.

For many people, when they think of windscreen failures, a British Airways incident from years ago comes to mind. For those of you unfamiliar, a maintenance error led to a windscreen blowout (the entire window assembly departed the aircraft) mid-flight. Miraculously there was no loss of life, but the incident led to the implementation of new and stricter criteria for a windscreen replacement. The incident has been engraved in every aircraft mechanic’s brain as a haunting reminder of what not to do.

I always imagined a windscreen cracking was as dramatic as the BA incident, but that’s not the case. It’s certainly inconvenient and stressful. However, there is no emergency decent, no mayday and no pan-pan. A descent is only prioritized to minimize the differential pressure, and any VFR flying is conducted from the seat without the damaged glass.

Windscreen replacement is typically not a strenuous task. It involves scraping the PRC sealant, removing dozens of screws and carefully manoeuvring the window from the frame. Installation is the reverse, with a very specific torque sequence. The entire task can be completed in a few hours, with a re-torque required after a certain amount of landings.

Unfortunately, this particular incident proved to be a bit more complex as we had to wait for the windscreen to be delivered to our location away from our maintenance hub. Our parts department opted to send two and that caused some mixed emotions: was it lucky they had sent an extra, or did it jinx us because they did?

I’m not superstitious but I am a ‘little-stitious’ — aviation has made me that way. Because, if you say, “It’s a quiet day,” it will suddenly be very busy. Or, if anybody jokes, “It’s about time for the plane to break down,” it will absolutely begin generating fault codes. Or if someone sends two windows when you only needed one,

“It’s an absolute nightmare for any AME to be dead set on fixing something that was partially working and ending with it not working at all.”

the first will surely crack during install. We completed the entire process for a second time, thankfully without any hiccups, and our plane was flying again a few short hours later.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case, and on occasion I’ve witnessed maintenance actions, during installation or ground-testing, that only made a situation worse.

It’s an absolute nightmare for any AME to be dead set on fixing something that was partially working and ending with it not working at all. In one particular instance, a hydraulic pump kept blowing the circuit breaker so we knew it was shorting, but we couldn’t figure out why. We replaced the pump because everything led back to that, and suddenly the system wouldn’t pressurize at all.

Another time some pilots were performing an operational test of the propeller overspeed governor when a simple and honest mistake was made resulting in both propellers

over-speeding. The rectification was to change all the blades on the aircraft. A team was sent to complete the task and, during post-maintenance function checks, the exact same mistake — the slip of a finger on a sensitive button — caused another propeller overspeed. A new team was sent and the rules regarding propeller overspeed testing were changed shortly thereafter. I wonder how the passengers of that flight would’ve felt had they been given the specifics about why they were deplaning.

As a passenger, would you rather know the details of what your flight crew is experiencing in the cockpit? Would hearing an AME explain why the plane is or isn’t okay to fly in its condition give you peace of mind? The traveller in me simply wants to close my eyes and put my feet up, but the mechanic in me wants to know and understand everything and therefore I’ll always look for those burn marks in the windscreen.

Surprised to discover we hadn’t drifted into a parked Twin Otter,” my new friend nodded as I hover-taxied the Bell Model 206L-1 helicopter toward the centre of Hassi Messaoud’s airport, 334 miles south of Algeria’s Mediterranean coastline. On that March morning, the kind stranger had sensed my longing to revisit the rotary regime and granted me a 30-minute flight above the Saharan sand. Shortly after the trip, he transferred elsewhere, and we never met again.

Decades later, Montréal-raised Patrick Richardson also noticed my yearning to savour pulsating rotor blades once more. As chief pilot and co-owner of Select Aviation College at Gatineau-Ottawa Executive Airport (CYND), 16 miles northeast of Canada’s capital city, his enterprise counted on eight Robinson R44 Raven Is as training platforms. Richardson and business partner Daniel Cyr also used 40 fixed-wing airplanes including Piper PA-44 Seminoles and Cessna types such as Cessna 180s on amphibious floats.

After obtaining a commercial pilot licence in 1999 before moving on to Inuvik-based Beaudel Air, Richardson survived 4,000 hours on floats, tundra tires and skis. The infamous 9/11 and industry downturn forced him south again where, as an astute businessman, he formed a prosperous automotive ignition distribution venture. Not content to leave aviation forever, he underwent helicopter conversion in 2013 at Passport Helicopters in Mascouche, north of Montréal, after creating Select one year before.

Curiosity led me to Select where security staff slipped word to the office about some bald-headed bozo wander-

ing the premises. Richardson welcomed me and, like my Algerian friend, seemed to surmise that, perhaps, slight rotary knowledge still lived within my mindset. He suggested a sample hop in a Robinson R44 although I had never handled a helicopter with a clutch or magnetos.

“They’re amazing flight training machines. You can put three big guys in, cruise 110 knots and burn 15 gph. They’re the Ford F-150 of helicopters,” he said. “New students, especially with

tailwheel or construction machinery experience, adapt quickly and most first solos take place around 20 hours.”

With ink long dried from North Bay’s 1985 Canadore College program and last revenue trip in 1987, I had doubts about remaining upright for long in any make of ‘fling wing.’ Previous indoctrination and follow-on field work occurred on turbine-powered Bell products. Nevertheless, Richardson’s positive attitude matched Canadore’s Allan B. Lang’s who I considered the greatest

instructor who ever bent a tail rotor.

Select’s 60 full-time employees included a helicopter division with four in-house-trained instructors and a cadre dedicated to ground school. Newly uniformed and clearly ardent, they submerged themselves almost seven days a week into the two-year, 130-flying hour academic-oriented college diplomas. Supplicants who wished to forgo night rating, simulator and survival courses, as well as the Bell 505 Jet Ranger X checkout, would walk away as quickly

as three months with a helicopter commercial licence. Entering the field can be costly, Richardson pointed out.

“There are authorized schools all across the country. Nobody comes to Select with the idea of saving $15,000 or $20,000. They enroll for opportunity and a chance to sign on at a place that’ll help them find employment,” he explained. “If shopping for a bargain price, don’t come here, for sure. Many good places offer the same licences. Ninety percent of our employees are former students and when they decided to work with us — that’s their major step — they’ve entered the industry.”

Select’s forthright attitude attracts. A whiteboard behind a dispatch desk greets career seekers and, although bargain prices do not exist in any form of aviation, forthright honesty encourages conscientious loyalty. State-of-the-art Raven Is list at $945 hourly for diploma programs and $995 for the non-academic courses. Students of any level pay their own accommodation.

While waiting on Select’s leather lounge couch, I overheard helicopter candidates discussing lessons and lifestyles. Accents and terminology sounded like I’d daydreamed into an Algerian suq (market) and a glance into my yellowed Pilot Transition Notes didn’t help. Richardson, with 12,000 hours including 1,000 instructional, appeared anxious to leave his office and slip into C-FIFE with a non-current old guy. Like Allan B. Lang, he showed no concern that every seagull and sparrow within 50 miles of Gatineau would frantically flap away from a belly-wobbling contraption lifted by a two-blade razor swinging at 408 rpm.

The Raven I weighed 1,505-pounds empty with a 2,400-pound gross powered by a 245-hp six-cylinder Lycoming O-540. After the model’s first flight in Torrance, California, on March 31, 1990, the company has the capability of producing 1,000 helicopters annually. Select’s C-FIFE appeared fresh from California’s coast with not a mosquito carcass marring the 38-foot, nine-inch riveted aluminum fuselage. Inside the

4.59-foot-high cabin, leather-like seats emanating freshness overwhelmed burbling fuel trucks and vapouring exhaust stacks. Nearby, another departing Raven I lifted to a hover and steadied in ground effect at 19 inches of Hg before fading toward La Belle Province’s leafy deciduous treeline north of Runway 06-27.

After learning the gravity-fed main fuel tank contained 26 imperial gallons when full and an auxiliary cell that held 15 imperial gallons, I realized that potential mastery of a costly creature (average pre-owned, low hours, Raven retailed for $363,457.10) demanded a dive into unfamiliar piston-oriented terms such as V-belt sheave, a device fastened to an engine output shaft which transmitted torque to a clutch. Cautionary bird-like warbles indicating 108 percent rotor rpm never existed in my past. A ‘sprag’ type one-way drive clutch came across as something a happiness seeker would find in downtown Bangkok’s Nana Street.

The Raven I depended on a seepproof hydraulically boosted main gearbox system to reduce control pressures. Without the liquid help, muscle power, or as a Robinson System Manual explained, a “large pilot input force” (muscle power), entered the picture. A collective control lever with hand-grip throttle lurked between the front seats and an odd-to-me T-bar Cyclic controlled movement backward, forward and laterally by tilting the 33-foot rotor disc.

Hopefully, right seat exposure would actuate some subliminal rotary flying genes. Richardson’s generosity in re-educating a fixed-wing clown bordered on phenomenal. Before and after the session, I saw the same attitude toward every student, AME, manager or instructor who stopped him in the hallways or on the ramp. After watching his meticulous pre-flight inspection and panel opening, I began to relax by studying an 18-item annunciator panel. Seconds later, told to do so, I pulled an overhead chain resembling a string of silver bearings designed to flush

a French commode. It disconnected the engine from the rotor to reduce starting loads.

After key turn, the Lycoming’s dual magnetos and 12 spark plugs sparked and at 60 percent engine rpm, a flip of a guarded Bakelite switch re-engaged the clutch and the rotor rotated. Carburetor heat push-pull and mixture control confirmed we would not overtemp or over-torque like an improper start on a free turbine powerplant. A dual needle instrument indicated engine and rotor rpm percentages.

Impatient, yet distressed with possibly coming across as an idiot, I retreated into a Charles Dickens-like “state of mortal apprehension,” aware that Richardson would soon learn how far from the rotary domain I had strayed. Airborne, overcontrolling began and attempting to maintain equilibrium reminded me of the pendulum in my grandmother’s kitchen clock.

The instant C-FIFE’s 86-inch-wide skids left the surface, our track across cringing grass blades looked like an exorcist shaking sacks of spiders. Richardson suggested a reference point 100 feet ahead. Pedal left or right, no member of my body slipped back to Canadore’s intense drills, reviews and

practice. Richardson could have justifiably called off the show. Mesmerized students, control operators and runway sweepers had every right to run for their lives. We continued and so did my desperation to “catch the hover” as Select staff called the procedure.

Finally, amplitudes diminished enough to enter traffic circuit cruise at 22 inches of Hg with 100 percent rotor and engine rpm. Speed steadied at 90 KIAS.

Straining to maintain 1,200 feet, I managed within 500 feet above and below. “Autorotations next,” announced Richardson. The concept of plunging out of a stable sky in a so-called vertical glide didn’t seem wise. I wondered if my overcontrolling had shimmered his brain tissue.

I lowered the collective to a built-in mechanical stop and twisted throttle to idle, taking care not to shut off the engine. Descent at 65 KIAS and 1,500 fpm panicked a suntanning woodchuck beside a taxiway while

several seagulls dropped their lunches and launched aloft. At 40 feet, Richardson screamed “Aft cyclic!.” I braked descent and speed. At eight feet, forward cyclic brought us level and a raised collective placed us into a flare followed by ground contact.

Richardson performed most of the exercise while I followed through. Moving from one event to the other, I glanced over and noticed his hands touched less and less. No low-rpm lights or warning horns activated nor did C-FIFE drift sideways into a dreaded rollover. Progress.

After more power recovery and to-the-ground autorotations, final approach required 60 KIAS down then zero forward speed and final transfer of weight to the skids. After 30 minutes before the contemplative Gatineau-Ottawa Executive Airport population, solo flight did not enter the picture. Industry-ready — not close. Employer-sponsored training would unlikely come again nor did my driveway shelter a Lamborghini to sell for self-sponsorship unlike Canadian Aviator’s editor. However, instead of a siren-screaming ride to a place of mental treatment, I understood that further tutelage would do the job.

Back on the leather lounge couch, I pondered about the devotees attractTALES FROM THE

ed to the expeditious organization beside the languid Ottawa River. A number of enthusiasts from Ontario and Québec traveled to Gatineau for 50-hour private pilot licences and often purchased low-time Robinson 44s directly from Select. Commercial fixed-wing candidates composing most of the roster concluded with 200 hours and advanced to instructor training. When finished, they can seek employment elsewhere or remain on Select’s staff.

“On the helicopter side, it’s different. When they finish a 100hour commercial, of which 37 is pilot-in-command, they need another 213 hours to become an instructor so where do they find that?” explained Richardson. “Fortunately, we have a helicopter section specializing in tourist trips — we did 1,000 hours last year. So, here, they can log enough time to become instructors and then we hire them.”

After a day without being evicted from Select’s pristine property, student babbles and accents I’d heard indicated they had arrived in Gatineau prepared to do whatever entry into the fascinating profession required. Washing windshields, wiping instrument panels, or filling fuel tanks, it didn’t matter. Graduates who obtained the school’s smart brass wings and coveted Aviation Document bestowed by Transport Canada were not forgotten.

“Anyone who’s been in our flight school and demonstrates the right attitude and stays on the ball, I’ll recommend them,” concluded Richardson. “Last year, every operator needed people and we’ve partnered with several companies. This was the first season we didn’t run out of pilots and usually take 25 under training. We intend to double that.”

In any case, I had much to be thankful for. Years ago, a kind Algerian stranger had helped retain my fascination for helicopters and now, in Canada, a flight school president closer to home restoked the fire.

This series has explained the several types of RNAV approaches that will get you to approach minimums. That is the easy part; the hard part is transitioning to landing or performing a go-around or overshoot if required. These are among the two most dangerous activities in flying. This article will discuss the former case.

Imagine an instrument approach at night in poor weather characterized by low clouds, poor visibility and high winds (particularly cross winds). You are glued to the dials (or glass nowadays) until you reach minimums then you start hunting for the runway, gain your outside bearings and land, all within less than a minute.

It was a dark night in Cambridge Bay in the middle of January with low visibility and a howling crosswind. I flew the VOR approach to minimums in the Boeing B737-200 and we acquired the runway; however, the runway lighting was the only lighting visible — a black hole approach. That alone is disorienting. Despite seeing the runway, it was difficult to get a sense of the crosswind and drift. However, we captured the PAPI and descended on it. The visual illusion of the black hole approach and the crosswind were simply too much to overcome in such a short period of time and I initiated a go around at less than 50 feet, much to the surprise of my partner. With the benefit of experience, we tried a second time and I was able to manage the illusion and drift and landed safely.

The lesson here is that even after acquiring the landing environment, the game is not over. Transitioning from instrument flight to visual flight in a brief period can be extremely challenging.

A good landing begins with a good approach. Transport Canada has been advocating the use of the Stabilized Approach concept. The professional aviation community has been using this for years and it has made significant

contributions to improving approach and landing safety. Hard landings, long landings and their attendant runway overruns and short landings are avoided if one adheres to the principles of a stabilized approach.

There are two gates, one at 500 feet AGL for visual approaches and 1,000 feet for instrument approaches. At these gates, the aircraft must meet the following criteria, otherwise it requires a go-around:

1. Aircraft configured for landing including landing gear and flaps

2. Briefings and checklists complete

3. Approximate power setting applied

4. Maximum sink rate of 1,000 feet/minimum

5. Airspeed +20 to -0 knots from reference speed

6. Small heading and pitch changes required to maintain the path

7. On the lateral and vertical path (1/2 dot laterally and vertically for instrument approaches or on the centreline and PAPI for visual approaches)

If all these criteria are not satisfied at the appropriate gate, it is a go-around to try again, just like my experience at Cambridge Bay. A go-around is a far better alternative than a bad landing, particularly on a short, narrow, gravel runway like Cambridge Bay.

Tight — tight — more Gs, more Gs!” Following my instructor’s orders, I did as he told me, pulling even harder on the stick. With no warning, the cute little red biplane I was co-piloting above the farmland of western Quebec had suddenly morphed from a children’s cartoon character to an unbridled ’G’ monster.

It was exhilarating!

Rewind the calendar to 35 years ago when, as an RCAF Canadair CT-114 Tutor instructor, I practically lived on a fat-free diet of high-G aerobatics. The more, the merrier. Today, a load factor of just 4-1/2 Gs felt like a concrete slab pushing me into my seat, simultaneously fogging my brain in the process.

As we briefly floated inverted across the top of my first more-or-less round loop, the focus switched to unloading

the previous stick backpressure, taking us into the less-than-one-G realm.

Seconds later came the call to bring the Gs back on “tight, tight, tight!” as we transitioned through the back half of the loop, remarkably finishing in more-orless level flight at the same altitude.

There was no question that my former first officer, Luc Martineau, seated behind me in the rear cockpit of his spectacular Pitts S-2C aerobatic biplane, had indeed become the schoolmaster, leaving me yet again demoted to fledgling aerobatics student. When not flying what he describes as his “favourite airplane” Luc is a skipper at Air Canada. In fact, I would go so far as to say this Boeing Dreamliner 787 captain is your quintessential overachiever. A graduate of the Royal Military College and former military officer, he also holds a comput-

er engineering degree from that great Kingston, Ontario institution.

Having checked him out on the 787, I know of what I speak. Luc is precise, detail-oriented and fully predisposed to perfection — which is exactly how he flies his 2012 Pitts (based in Lachute, Quebec). Martineau is happy to give an introductory flight for those interested in aerobatics or advanced flying courses. His only condition is that pilots check their egos at the airport gate and show up ready to learn.

Our 45-minute pre-flight briefing began with flight safety considerations. Next came the manoeuvres he had planned on demonstrating, including those I would get to try. The focus was on rudder work and G-loading. Knowing a little bit about the topic, I found his explanation of the physics of aerobatic

flight (especially when strapped into an aeroplane with 20 feet of wingspan and 260 horsepower up front) worth the trip to Montreal alone. Added to this was his briefing on aeromedical considerations, including a counterintuitive warning of the necessity to not eat within two hours of flight. Finally, the call came for full disclosure: “Are your pockets empty?” Captain Martineau also has a pair of onboard GoPro cameras recording the flight, so you might as well leave your iPhone at home.

Based on his insurance company’s requirements and the advice of his own instructor, Luc makes it clear to all potential students that this is an aerobatics course, not a Pitts-type checkout. This means that they will not be allowed to touch the stick for takeoffs or landings.

I asked Luc how he came to fly the Pitts, an airplane with a reputation for being remarkably challenging to handle. He gives full credit to his own instructor, telling me the story of how he met US Navy Rear Admiral (Ret’d) Bill Finagin. Bill is a legend in the aerobatic world, a multiple-time champion in advanced categories with over 18,000 hours in the Pitts. Added to that is a surface waiver for airshow flying which means he is cleared right down to the deck.

After their first flight together, Luc knew he had found the man to teach him to fly Curtis Pitts’ little legend and so enlisted Bill as his instructor. Regarding Luc’s initial Pitts checkout, Finagin was ready to cut his new student loose for solo after only 15 hours of flight time. Luc countered with a request for an additional 10 hours. An insurance company was the final arbiter, requiring 50 hours on type before they would sign Luc off for solo aerobatic flight. That is how demanding a Pitts can be to fly. Even with all his experience in the airplane, Luc insists on taking his own spring refresher course, to “remove the rust,” as he says.

It is hard to believe any rust could form on my former colleague. Martineau is himself a remarkable aerobatics pilot and equally talented teacher, winning in the top-rated Intermediate

Aerobatics category. Our one-hour flight, which included ballistic rolls, hammerheads, loops and Cuban 8s, flew by in what seemed like mere minutes.

Even with a considerable amount of time logged doing aerobatics in military aircraft, I found attempting the same manoeuvres in a piston-powered Cessna A152 Aerobat very challenging, bordering on darned hard. Then Luc reminded me this was a purpose-built, world-class competitive biplane, describing it as “a little arrow with an orgy of power.”

No further convincing was required and it became readily apparent to me that teaching aerobatics in such an airplane is anything but routine. I asked the Montreal-based Dreamliner captain if he had any interesting experiences flying with students. He spoke about occasionally departing controlled flight in what he described as “ballistic flight,” which had in turn led to inverted flat spins.

I proudly started telling Martineau about my own experience spinning the

Tutor inverted — that is, until he started discussing the 10 varieties of spins he is proficient in. Take Luc’s spin training and you will get to explore and, more importantly, learn how to recover from each of them. In case you are wondering, when flying inverted the Pitts will rock your world at negative 3 G in a mind-blowing accelerated inverted spin.

Aerobatic flight might dazzle judges at competitions and wow the crowds at airshows, but it has another even more significant benefit. Take aerobatics training at any level, and the confidence you will gain in recovering your own aircraft from almost any attitude will be astounding. A one-hour hop or 20-hour course with Luc Martineau in his amazing Pitts S-2C will sharpen your energy management skills and situational awareness and, in doing so, make you a better pilot. Just remember to push on that right rudder, and to “Pull… tight, tight, tight!”

You can contact Luc at info@ lachuteaviation.com.

LIVING THE DREAM WITH CHRIS WEICHT

CHRIS WEICHT AND HIS MU-2 ADVENTURES

Other interesting flights were made for the RCMP and CSIS but not enough space is available for my reports. I will finish with the story of our longest charter flight on behalf of the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company (COMINCO) from Abbotsford, British Columbia to Kotzebue, Alaska.

In August 1989, Airlift Canada received a request from COMINCO for the transport of a group of their executives from Abbotsford to Kotzebue, Alaska, and then on to their mining operations at the Red Dog Mine at Noatak River. The Red Dog Mine is situated almost 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. From the air on a clear day, you can see Siberia across the Chukchi Sea. This would be one of our longest trips to a very remote area. The open pit zinc mine is situated almost 100 miles from tidewater where the zinc is transported by ship for eventual delivery to Trail, B.C.

I had flight-planned for a direct flight to Anchorage and then to Kotzebue for the night and then on to Noatak River the following day. As we proceeded up the coast the weather deteriorated, and I decided to stop at Sandspit in the Queen Charlotte Islands for fuel in the event the weather at the destination airport was worse. As we were abeam of Yakutat, Alaska we received a radio report that Anchorage; other possible alternates were becoming poorer options for landing. After consulting my navigation maps, I decided that we could fly direct from Yakutat to Northway in the Alaskan interior, clear customs and refuel, then continue to Kotzebue. I contacted Alaska ATC and made my request. They responded as follows: “Canadian Mitsubishi Charlie Foxtrot Alpha Mike Papa is cleared from present position direct to Northway to maintain Flight Level 210.”

I felt that this was a sensible option and that I was doing the right thing in view of poor weather further up the coast. As we proceeded on the 165-mile flight, we started to encounter turbulence that soon became violent. We knew that we were overflying rough mountainous terrain, but I had neglected to look closely at my chart. We were flying over the second highest terrain in North America, and in fact very close to Mount Logan at 19,850 feet, the highest peak in Canada.

All aircraft flying above 18,000 feet are in a zone (the standard pressure region) where the altimeter must be set to a standard barometric pressure indication of 29.92 inches of mercury. Another upsetting factor about this flight was the unusually low barometric pressure on this day due to the intense storm through which we were passing, which would give our aircraft an even lower altitude than was indicated on our altimeter. I had committed a cardinal mistake and flew too low through this ominous jumble of rock and ice.

as the area was within the ADIZ or Area Defence Identification Zone due to its proximity to what was then still the Soviet Union. The flight over treeless terrain went without difficulty and we landed on the gravel airstrip at the mine. There we waited for our passengers to have their meetings and to tour the operations. That done, we departed down the gravel road where the ore was transported to Kivalina for shipment by freighters.

We again spent the night in Kotzebue then left early next morning for Anchorage. Prior to landing we had an unrestricted view of Mount McKinley, which at 20,320 feet is the highest mountain in North America. We then flew direct to Abbotsford.

“I had committed a cardinal mistake and flew too low through this ominous jumble of rock and ice.”

The MU-2’s speed of over 300 miles an hour thankfully had us past the dangerous peaks of the Saint Elias Mountain Range. As we approached Northway breaks appeared in the cloud that had surrounded us since Yakutat. Soon we were able to land. My son Andrew and I realized our transgressions and did our best to appease our paying passengers for their extremely rough flight. The gods this day had smiled on us. Lesson learned.

Our flight continued via Fairbanks with good weather on to a successful landing at Kotzebue, a treeless mainly native village situated on the Bering Strait of the Chukchi Sea. We checked into the local Nullagvik hotel and after a bit of walking around the village went for a fabulous dinner of Muskox steak. The next morning we carefully planned our flight to the Red Dog Mine,

In early June 1990, COMINCO decided that it was no longer viable to maintain our MU-2 charter business due to the economics of their operation. CF-AMP was sold to a Kansas-based company and I flew the airplane’s last trip on June 10 to Salt Lake City, Utah where Airlift was having a directors’ meeting. After an overnight stay I flew to Wichita, Kansas to deliver the aircraft to its new owners.

On delivery, June 11, 1990 I offered to train the staff of this company. My offer was refused as they said they did not need it. Two weeks later I received a report that MU-2 CF-AMP had crashed and all aboard were killed. Sadly, they neglected to believe that the MU-2 was not just another airplane.

Airlift Canada decided that they would acquire a newer long-bodied MU-2, which would be operated in a medevac capacity in the Alberta STARS (Shock Trauma Air Rescue Society) program, My (then) wife did not want to move to Calgary, so I declined the offer of a job as chief pilot of the Calgary-based program. Airlift treated me fairly in my separation from the company and I was compensated accordingly. However, I now believe that I had made a career mistake.

Get great article suggestions and post alerts when new issues become available.

ATC VIEWPOINT WITH MICHAEL

If you have been following my column in this fine publication, you may have noticed a recurring theme. For those who have not, please let me introduce you to it.

An issue of growing concern across the country, especially over the last few years , is conflicting air traffic. Not only VFR versus VFR, but IFR versus VFR as well. I worked as an airport controller in my early days of air traffic control, but for the last 30 years I’ve been an enroute/terminal controller. I can vouch for the increase in air traffic issues for both kinds of controllers and different flight rule pilots. Transport Canada and Nav Canada are keenly aware of these issues and are attempting to find ways to resolve them.

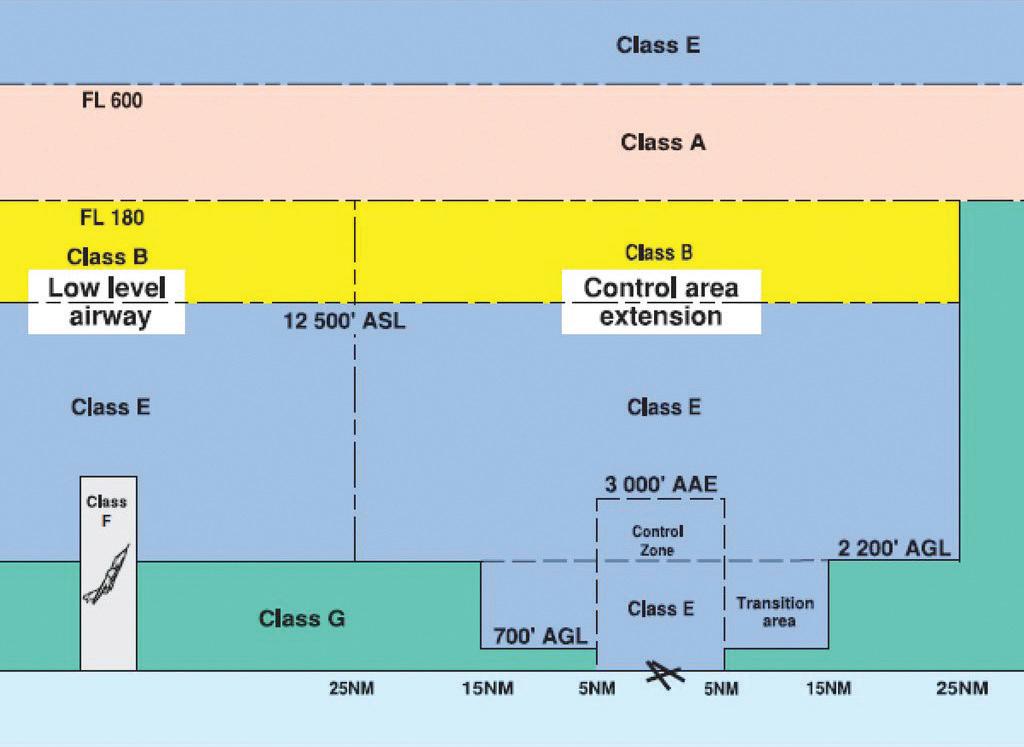

Airport controllers have a tricky and under-appreciated job in many of the nation’s control towers. Airport layouts may be complex or have few taxiways, which could lead to complications. Trying to accommodate ‘faster’ with ‘slower’ traffic can present many challenges. Surrounding airspace, whether controlled by an enroute sector in an Area Control Centre (ACC) or dedicated Terminal Control Unit (TCU), comes with its own issues. One of these issues is the primary topic for this article: the mixing of IFR and VFR traffic.

I mentioned the airport controllers above since they are also often involved in trying to straighten out IFR versus VFR conflicts, even if they occur outside an airport’s Control Zone. Trouble commonly arises between five and 15 miles from the airport. Around many airports in Canada, the concerned airspace is Class E. This airspace contributes much toward the problem. Class E airspace is controlled airspace where IFR aircraft are subject to Air Traffic Control clearances and instructions. IFR Pilots must follow ATC

Airspace classifications in Canada.

directions, from departure to arrival. To do this, pilots usually fly prescribed flight paths and altitudes where instrument procedures are typically flown in VFR weather just as surely as in IFR weather.

However, VFR aircraft operating in Class E airspace do so quite differently. The ’controlled airspace’ part of Class E serves to increase the weather minima for VFR pilots. This increases the odds of ’see and be seen’ for both the IFR and VFR pilots. Air Traffic Controllers, though, have no authority over VFR pilots operating in Class E airspace. Even if a suggestion is made (or a directive given) by a controller to a VFR pilot in Class E airspace, the pilot has no obligation to obey. Under Canadian Aviation Regulations, the VFR pilot flying in Class E airspace is not even required to contact ATC or ACC. Pilots operating near airports can be engaged in training or exercises, for example, meaning there can be distractions as

instructions are given to the student. This can mean ’heads down’ time in the cockpit, greatly limiting the ability for both pilots to keep a careful watch outside for air traffic. The aircraft may also be flying by a solo student with limited experience.

Many pilots setting a course on VFR cross-country flights are taught to plot a course using a prominent landmark as a ’set heading point.’ Chosen landmarks can often be located where that could complicate traffic flow. Even those who don’t use this method, perhaps knowing their planned course well enough or following GPS guidance, may end up flying through areas where IFR traffic is operating without even realizing it.

On approach to an airport, the IFR aircraft usually follows clearance for an approved approach procedure. These procedures are typically initiated between eight to 15 miles from the airport and, in a straight-in approach, have paths normally aligned with

the runway centreline as the aircraft enters the aerodrome’s Control Zone or Mandatory Frequency area. Pilots typically have initial approach segments (base legs) to begin their final approach that are typically aligned 90° to the final approach heading. This is the situation where IFR and VFR traffic typically mixes and merges, potentially leading to problems.

Because instrument approach procedures are often designed with a glidepath near three degrees, IFR aircraft are often expected to appear between 3,000 and 5,000 feet Above Aerodrome Elevation (AAE) on the base legs. That’s also a very common altitude range for operation of VFR aircraft, whether they are on crosscountry flights, conducting local training or just sightseeing.

Where surveillance coverage exists, controllers will often see potential conflicts and will pass traffic information to the IFR pilot as the aircraft navigates to begin the approach procedure. Sometimes VFR aircraft are flying directly in the intended path of IFR aircraft but are unaware of this traffic.

In the absence of raising the VFR pilot on the ATC frequency, the controller cannot know the intentions of the pilot. Doing sightseeing or training manoeuvres, the VFR pilot may unexpectantly change course or altitude. This unpredictability might be okay for what the VFR pilot wants to do, but it certainly complicates the integration of IFR aircraft into the approach pattern. Consider as well that the speed and the wake turbulence of IFR aircraft tends to be higher and greater than the average VFR aircraft. So how can this problem be mitigated? Some have suggested altering the classification of airspace around several midrange-volume airports to Class D. This would have the effect of requiring VFR pilots to talk to ATC, enabling controllers to more effectively keep aircraft flightpaths apart. It would, however, increase the workload of both controllers and pilot as new responsibilities are added

to each of them. This might be a ’be careful what you wish for’ solution. Alternatively, VFR pilots may voluntarily contact ATC. This means calling the tower well before reaching the Control Zone boundary. The airport controllers will have information on inbound IFR flights and can pass this traffic information to the VFR pilot. This also serves to inform the ACC or ATC of the intentions of the VFR aircraft if an IFR arrival appears to be in conflict.

The VFR pilot may elect to contact the ACC controller directly on an appropriate arrival frequency within 15-20 miles of the airport if they plan on flying above, say, 2,000 feet AAE. Since this is the area where potential conflicts between IFR and VFR are likely to occur, the controller may be able to inform the VFR pilot of traffic, allowing him or her to safely alter course.

VFR pilots who don’t wish to contact ATC may choose to monitor the radio frequency of the ACC near the airport. This may not give them the best information on traffic operating nearby, but may help. As a controller who passed traffic information to an VFR aircraft whose intentions were unknown, I have occasionally reached pilots this way. When the pilots concerned realized that they were the traffic, they checked in to confirm what was going on. That gave me the chance to help ’de-conflict’ the situation by sharing information, offering suggestions or modifying clearances for either the IFR or VFR aircraft.

It may only take a few seconds to check in when nearing an airport to see if there is any traffic a pilot should be aware of, but those few seconds can be valuable. Ideally, this advice should apply to both VFR and IFR pilots.

I don’t believe there is a ’magic bullet’ that can stop potential conflicting air traffic issues from occurring, but there are a few simple steps that can be taken to minimize or even eliminate the risks. As always, everyone should keep an eye out and watch for other traffic.

AIRMANSHIP WITH GRAEME PEPPLER

ESSENTIAL READING — TWICE A YEAR

When asked how many pilots download, then scan through, Transport Canada’s biannually updated Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM), a senior Transport Canada (TC) official jokingly held up his hand and brought the tips of his index finger and thumb together into the universally recognized symbol of a zero. If true — and this particular individual knows what he’s talking about — then this is a shame.

The TC AIM is written to provide Canadian pilots with information on rules and procedures for the operating of aircraft in Canadian airspace. Subjects covered include, but are not limited to, aerodromes (AGA), communications and navigation (COM), meteorology (MET), rules of the air (RAC), search and rescue (SAR), aeronautical charts (MAP), licensing and airworthiness (LRA), and airmanship (AIR). The subject of remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) is now covered thoroughly as well.

A revised release is available every spring and every fall. It has as its target-audience everyone connected with flight operations in the country. Its content is full of informative nuggets — many of critical importance to the safety of flight operations — that cover a full spectrum of topics that have relevance to every industry participant.

A scan through the October 2024 release of the AIM spotlights the kinds of details that may typically proliferate across its regularly revised pages. For instance, as it concerns the subject of meteorology, 11 updates span this specific section in this particular release. Amongst these 11 updates, a revision to flight weather documentation requirements now suggests that pilots avail themselves not just of GFAs, AIRMETs, SIGMETs, TAFs, METARs, SPECIs, PIREPs and upper wind and temperature forecasts, but that they now also add the latest weather satellite images, weather radar and lightning detection information to their pre-flight verifications.

And while reminding pilots that upper wind and temperature forecasts should form part of their pre-flight planning, the latest AIM expands on previously announced revisions to upper-level wind and temperature forecasts themselves.

These forecasts, known as FDs, are now being replaced by FBs, where the former are issued twice per day (but are being phased out) while their replacements (the FBs) are issued four times per day with a mildly notable heading format change. Format changes are also identified in the latest AIM pertaining to the Comments Box that appears with Graphic Area Forecasts (GFAs). Furthermore, the remarks associated to METARs have undergone a tweak with the adding of directions; for example, the remark “PRFG SE-N” indicates that fog is partially covering the aerodrome from the southeast to the north.

ber of new procedures, not the least of which relate to: (1) how large turbine-powered aeroplanes may fly the traffic circuit at 500 feet above the established circuit altitude, (2) how pilots of rotorcraft should fly the circuit normally flown by aeroplanes but at a lower altitude (of 500 feet above aerodrome elevation) and closer to the runway, (3) how pilots of low-performance aircraft (such as ultralights) may fly a circuit at an altitude no higher than 500 feet below and inside the standard circuit of the aerodrome, and (4) how gliders flying a diagonal leg from downwind to base between 500 feet and 1,000 feet above aerodrome elevation — and always, inevitably, in descent mode in the circuit — require that aeroplane operators provide extra vigilance and heed to the glider’s right-of-way.

Taxi information gets a lexical, and very necessary, nip-and-tuck in the latest AIM. With runway incursions continuing to be a hot concern, air traffic service (ATS) personnel will now be requesting a readback for all “Hold” and “Hold Short” instructions or requests that have not been read back by the pilot to whom they’ve been directed. (Previously, the AIM did not specifically state that the readback will be requested if it is not provided by the pilot. It also offered that the readback was a “good practice” by pilots, but implicitly not necessary.)

Where the October 2024 edition of the AIM cuts deeply into new territory comes in the rules regarding traffic circuits at aerodromes. A slew of new conditions now appear which describe approach and landing procedures that are thoroughly more encompassing than previously chronicled. The upgraded content sets forth, for both controlled and uncontrolled aerodromes, a num-

The latest AIM gets even deeper into matters at uncontrolled aerodromes. It stresses the pilot’s responsibility to deconflict from other aircraft. It has jettisoned the expression of an aerodrome’s “upwind side” in favour of the expression “non-active side,” the latter being the side from which it pointedly favours that approaches be initiated. The phraseology, “Any traffic in the area, please advise” is now strongly discouraged in communications, and straight-in approaches are singled-out not to be used as well. Indeed, this AIM has a lot to state about traffic circuit procedures at uncontrolled aerodromes.

The bottom line to all the above is this: the AIM is a useful product from which active aviators can keep on top of operational changes in Canada. Everyone is well-advised to download each new release from the TC website, then to focus on the shaded teal backgrounds that highlight the new stuff that they really ought to know. When all pilots are up to speed, operations are safer for everyone.

Each of my pre-solo students must demonstrate their ability to fly a circuit from takeoff to landing without viewing any flight or engine instruments. I expect them to assess speed by listening to the wind noise over the airframe, to tell altitude by observing ground references and set RPMs by ear. The sectional chart that I use to hide all the instruments also prevents them from seeing the levers and forces them to identify them by feel alone, based on their distinctive shape. For example, the airfoil-shaped lever is for flaps and the little wheel lever is for landing gear.

This is clearly not a regulatory requirement. In fact, as flight simulators and glass cockpits become the norm at flight schools, fewer and fewer flight instructors can and do teach in-flight sensory awareness. However, I believe that as computer-flying replaces hand-flying, teaching pilots-to-be when and how to use their senses to confirm normal operations or flag anomalies is more critical than ever.

Of course, using only sensory inputs can kill when spatial disorientation takes hold of pilots. So, pilots are trained to ignore their sensations and trust their instruments. But when flight instruments fail or distractions prevent a systematic and continuous instrument scan, sensory awareness can save the day. Developing a physical sense for aircraft speed, turns and power settings is healthy if it comes with a strong understanding of its limitations and potential dangers.

“Add power. Check proper RPM. Airspeed alive.” These common takeoff instructions fail to develop common sense sensory awareness. “Add power. Listen for proper RPM. Aircraft moving,” are also relevant to proper operation. Bringing attention to these normal takeoff sensations should be part of any primary pilot training and so should paying attention to the aircraft readiness to fly before pulling back the yoke or stick. Teaching students to pay attention to this would prevent many takeoff mishaps. I suggest “Vr. Light on the wheels.” as a

clue to rotate instead of just Vr.

In explanation, if at rotation speed the aircraft’s wheels still feel strongly connected to the ground, that means the wings are not developing enough lift to lighten up the load on the wheels. Airfoil or high-density altitude conditions could be the culprits as they decrease the aircraft’s ability to create lift for the required air speed. Forcing an aircraft aloft strictly in reference to instrument numbers under such conditions can make for an interesting experience at best.

Cognitively, data gathering and number crunching to create a mental picture is far more difficult to do and is a bigger brain-drain than just looking at a compiled/complete picture. That is why we invented synthetic vision to do the data gathering and the number crunching for us that presents a straightforward picture of what is going on. The all-in-the-box simplification process removes the potential for human calculation/interpretation errors but at the same time makes it harder to proof-check computer output.

Smart and wise pilots do not just trust a heading computed by a GPS unit; they cross-check it against the intended direction, maybe not to the exact degree using a manual flight computer, but to the general direction for the flight. Obviously, a westbound flight should not include an easterly heading unless a procedural course reversal is required. Any GPS-suggested heading not consistent with the general direction of the flight is a flag to a potential error and a bad situation.

Wise pilots use their trained senses in a similar manner. An attentive pilot can feel/ see/hear most significant changes like engine output, speed and bank angle before the numbers register on lagging instruments. No training in acknowledging such sensations robs pilots of potentially critical warning signs. However, developing these critical skills must come with a strong understanding that our biological senses, just like our mechanical or digital instruments, can fail us. Our vision, our kinetic senses, our hearing have limitations. They too can mislead and deceive us and should be ignored on occasion. As pilots we are all familiar with the visual challenges of landing at an airport very different from our ’normal’ airport. We train to recognize spatial disorientation and recover from it.

Learning to identify inaccurate data, whether it is a product of our human-made equipment or biological endowment before removing it from consideration, is one of our key responsibilities. It begins with a full understanding of the tools we have and how to use them. When all available human-made or human sensory ‘inputs’ are ‘synchronized,’ we are reassured that everything is proceeding according to plan. If one seems ‘out of sync,’ then the more alternate sources of information we have, the easier it is to proceed safely.

Over the years, my pre-solo students have been consistently accurate in my ‘bare minimums’ challenges. Confidence building is one of the most significant spinoffs of the exercise. Imagine how you would feel about flying if you proved to yourself that with just an airframe and an engine, you would still be able to successfully pilot an aircraft. Try it, you will be amazed at how much fun it is. You will become a safer pilot in the process.

AEROBATICS WITH LUKE PENNER

Pop! Ouch! That’s not good,” I thought as I was jolted violently in an unexpected direction inside the cramped cockpit of my Extra 330SC, a force that hit hard into my lower back. After landing, I brushed it off, but within hours an intense pain set in, where every movement felt excruciating. With just two weeks until the start of the 2024 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships, this was hardly the ideal time for an injury. But more on that later.

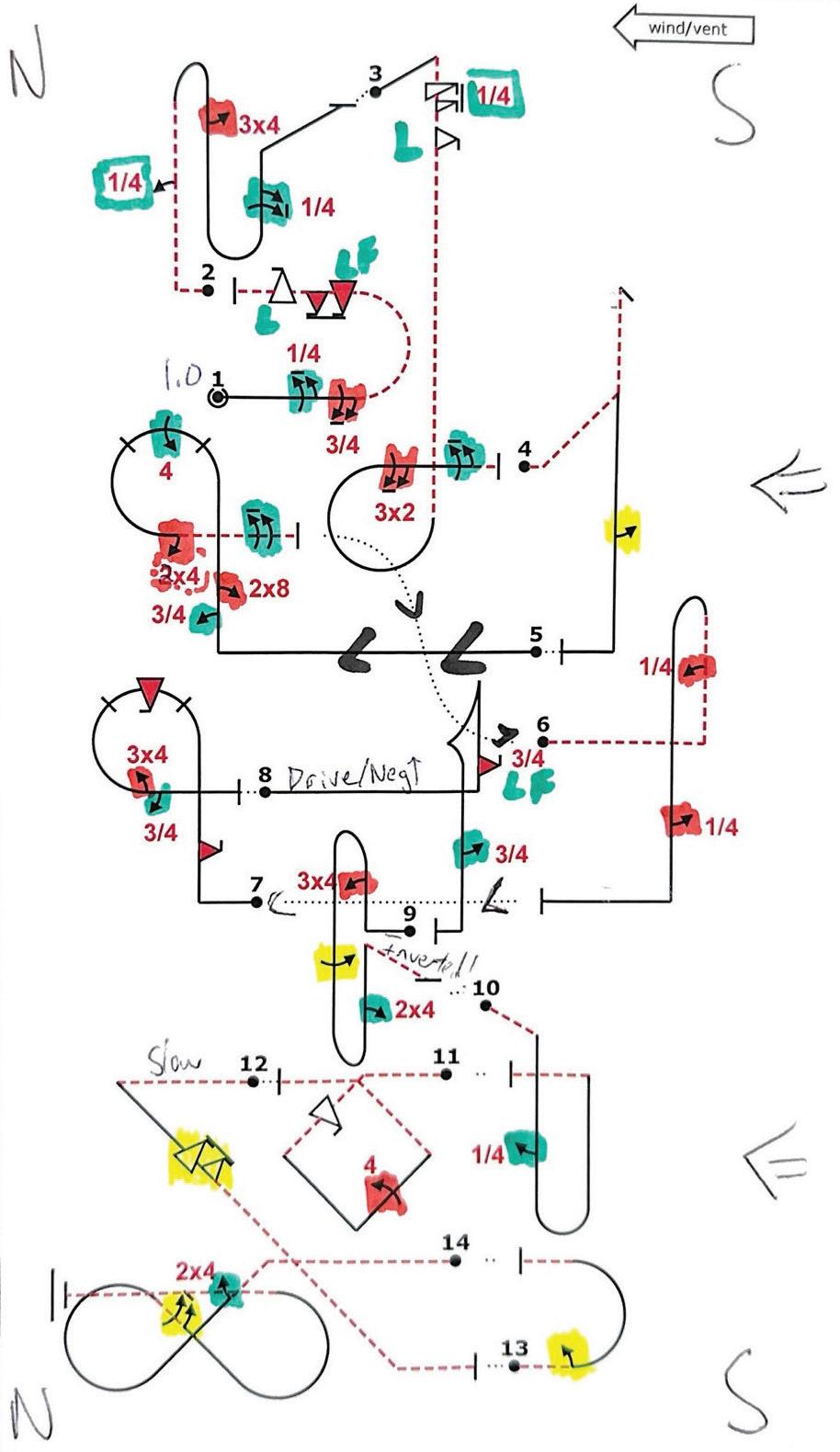

This debut-year competing in the Unlimited category has pushed me to train harder than ever to master the vast range of figures and combinations that are required to execute. One of my biggest challenges was learning vertically ascending snap rolls, both negatively and positively loaded, with precision and efficiency. After years of building up the infamous negative three-quarter snap roll in my mind, I started a spring training regimen, gradually getting comfortable with Unlimited figures and building my G-tolerance. Weeks of intense snap roll practice in my training box near Steinbach South Airport finally led me to pack up the tiny baggage space of the 330SC and head for warmer skies in Iowa for my first training camp of the season.

In early May I teamed up with my longtime friend, coach (after eight years of working my way through the category system) and fellow Unlimited competitor Aaron McCartan for an intense five-day training session. Our initial focus was to develop many of the new figures required in the International Academic Competitions (IAC) Unlimited, including negative snap rolls in every possible attitude and as many rotation variations as we could tackle in a week. We also set out to master the intricacies of the colloquially named ‘Ming Vase’-style snap rolls.

A quick refresher: a snap roll is an accelerated stall (either positively or negatively stalled) that leads to rapid autorotation, induced by stalling one wing with the use of rudder. In a ‘normal’ snap roll, for example, the airplane is upright on a level line, and the manoeuvre begins by rapidly pulling the stick back to increase the angle of attack close to the critical angle, then applying rudder to initiate

autorotation. Now, imagine staying level and upright, but instead of pulling, you push the stick forward as hard and fast as possible. It’s counterintuitive, requiring a larger angle of attack to reach the critical point (i.e., stall) while at the same time pitching toward the earth. And yes, it’s just as uncomfortable as it sounds.

Several months later and just a couple of weeks before the U.S. Nationals, I felt confident in the foundation that Coach McCartan helped me build. It seemed like the perfect time to tackle a glaring weakness of mine: I could only perform the ascending negative three-quarter snap roll with left rudder, causing the airplane to rotate to the right. Mastering the initiation alone took months of practice. Achieving a precise stop took even longer. Limiting my rotation to the right meant that, in certain figure combinations, I was at a disadvantage. To address this, I set out to develop my right rudder/left-rotating negative snap rolls on the vertical.

It might not sound like a big deal to simply switch feet, but when your entire body’s muscle memory is tuned to an already disorienting figure heading in one direction, building the necessary new muscle memory is challenging. So, when I slammed the stick forward on that vertical upline, I wasn’t quick enough with my right rudder. It requires more aggressive right rudder than left rudder to counteract the propeller’s gyroscopic forces. As a result, the airplane didn’t stall and autorotate as expected; instead, the torsional load hit my lower back. And yes, it hurt.

With only two weeks left before the start of the U.S. Nationals, I spent nearly every day visiting a chiropractor and massage therapist to ensure I’d be ready for the final training camp in Iowa before heading down to Salina, Kansas, for the competition. Thanks to their expertise, my back improved enough for me to fly with minimal pain, allowing me to join Coach McCartan, several other pilots from Canada, some from the U.S. Midwest and one from the U.K. for one last intense push prior to what is, in terms of competitor numbers, the largest aer-

obatic competition in the world. These training camps are among my favourite parts of aerobatic sport. Days are spent pushing our skills to the limit with friends, where evenings are capped off with a great meal and where we dive even deeper into flying and aerobatics — only to do it all again the next day.

After finishing the training camp in Algona, Iowa, we all flew down to Salina in a five-ship formation. Ironically, our group consisted of four Canadians, one Brit and only one American (Coach McCartan). Once we landed and got settled in Salina, we had a few days before the championships began. We spent this time flying final practice sessions in the competition box and mentally preparing ourselves. I worked with my sports psychologist to get into my optimal headspace — because despite the physical demands of aerobatics at the Unlimited level, it’s still largely a mental game.

Arriving at the briefing for my first Unlimited program, I found it surreal to hear my name called alongside legends like Goody Thomas and the now 13-time consecutive U.S. Unlimited Champion, Rob Holland. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t intimidated stepping into this competition, and I was blown away by how welcoming and supportive the other 10 Unlimited competitors were all week long. I’m incredibly grateful for the training I received from Coach Mc-