Accounts from both pilots take us behind the scenes and into their cockpits

BOEING AIRCRAFT OF CANADA The Aerospace Giant’s Early Days in Vancouver Cessna 182 Panel Makeover DEEP POCKETS MAY BE REQUIRED WAAS and Augmented GPS ED McDONALD EXPLAINS THEIR WORKINGS CANADA’S MOST POPULAR AVIATION NEWSSTAND TITLE MAY/JUN 2024 CANADIANAVIATOR.COM DISPLAY UNTIL JUNE 30 QUICK SUBSCRIBE! PM42583014 R10939 $7.95 RCAF FIGHTERS OF TODAY AND YESTERYEAR

FROM THE GROUND UP, 30th Edition

PrivatePilot Magazine

if you are going to buy a flight manual and only want to have one around the house, this is the one.”

“There is a smoothness and ease-of-reading that make this book a pleasure to read… everyone out there should read the engine section, which is excellent and covers timing, carburetors, magnetos, solid-state ignitions and even a procedure for a backfire during starting…

For over 80 years, the content of From the Ground Up has stood as a literary benchmark that defines the multitude of theories associated to aeronautics. It describes the practices necessary to achieve the highest levels of distinction as safe, competent and skilled life-long aviators.

Flyer Magazine

“[From the Ground Up] offers a wide range of advice and information, technique and instruction, on practically every aspect of flying –in a single volume… The level of detail and its easy-going writing are way ahead of some of the text books we’re used to, especially when it comes to radio navigation and aircraft technical explanations… I found From the Ground Up so useful that it’s becoming part of my deskside library.”

“For 50 years the book From the Ground Up has been published and is one of the most comprehensive volumes on the subject of flying and learning to fly… it can be read right through, from cover to cover, or can be dipped into for information on specific subjects. Some aviation books cannot comfortably be used in this dual role.” International Flight Training News

Through its evolving editions, many generations of readers have used this award-winning title as the foundation of their introduction to the concepts that require thorough understanding in advance of the sought-after hours of flying enjoyment that are the ultimate goal of all who seek to earn their wings and expand their knowledge of flight theory and practice.

From the Ground Up ®

Aviation Publishers Co. Ltd.

ISBNwww.aviationpublishers.com

978-0-9730036-3-5

9780973003635

The content of From the Ground Up may, at times, seem complex, but the pathway to learning the fundamentals of aeronautics is one that reaps much in the way of personal reward for all who pursue the goal of thoroughly understanding the subject. Indeed, it was by design that its original author, “Sandy” A. F. MacDonald — a man recognized as a “father” of what still stands today as the standard curriculum for ground school instruction — devised this aeronautical textbook to be comprehensive and current while conveying its material in such a way as to enhance the reader’s understanding of every written word.

Published by Aviation Publishers Co. Ltd.

Not one to permit his vast experience to allow for foregone conclusions, “Sandy” MacDonald’s meticulous care in the creation of From the Ground Up has become the hallmark for its widespread use and respect as the reference manual of choice in hundreds of flying schools throughout Canada and around the world.

Its latest edition is the 30th Edition. A French-language version is also available under the title Entre Ciel et Terre Totalling over 400 pages of in-depth content formatted in a sequential, logical and easy-to-read fashion, the publication boasts over 360 graphics, charts, diagrams, illustrations and photos. An additional full-colour navigation chart and a sample weather chart are included.

All chapters are current in the latest technological and legislative aeronautical matters and cover such topics as The Airplane, Theory of Flight, Aero Engines, Aeronautical Rules & Procedures, Aviation Weather, Navigation, Radio & Radio Navigation, Airmanship, Human Factors, and Air Safety From the Ground Up also includes an extensive index, glossary and a 200-question practice examination.

Since the 1940’s, virtually every student — civilian, military, commercial, recreational — who has ever learned to fly in Canada has used From the Ground Up as the primary ground school textbook from which they’ve learned everything one can learn about aeronautics, and about flying. Referred to as “the bible” of ground school instruction, and updated with every frequent re-print, From the Ground Up has long been considered an essential resource for all with any interest whatsoever in the theory of flight, and in the practice of aviating.

For more information about this title, visit us on the web where you can obtain details on how to acquire this, and all of our other aeronautical publications.

A World Leading Source in Aeronautics for 80 Years

AVIATION PUBLISHERS CO. LIMITED Box 1361, Station B, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1P 5R4 www.aviationpublishers.com

aviationpublishers.com

A v a ilable from

IN THIS ISSUE

DEPARTMENTS

5 / WALKAROUND

The recreational pursuit of business?

6 / WAYPOINTS

Aviation news

By Aviator Staff

8 / AIRMAIL

Memory lane

By Aviator Staff

9 / GEAR & GADGETS

Four aviation products

By Aviator Staff

10 / FLYING STORIES

Islander continued

By Jack Schofield

12 / THE PLANE FIXER

All in a day’s work

By Liana Buessecker

14 / TALES FROM THE LAKEVIEW

Volunteer extraordinaire

By Robert S. Grant

16 / EXPERT PILOT

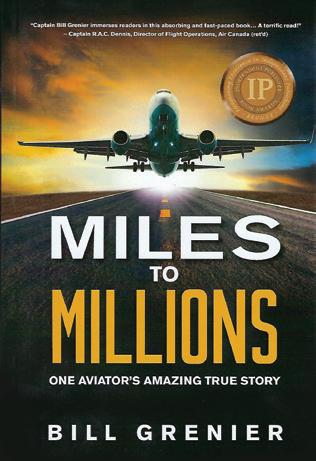

One thing led to another

By Richard Pittet

18 / A PILOT’S LIFE

Ice everywhere and on everything

By Chris Weicht

20 / INSTRUMENTAL FACTS

Augmented GPS explained

By Ed McDonald

22 / VECTORS

Is ATC work stressful?

By Michael Oxner

24 / RIGHT SEAT

Transitions

By Mireille Goyer

26 / PEP TALK

RSCs and CRFIs explained

By Graeme Peppler

28 / COLE’S NOTES

In memorium

By W.T. (Tim) Cole

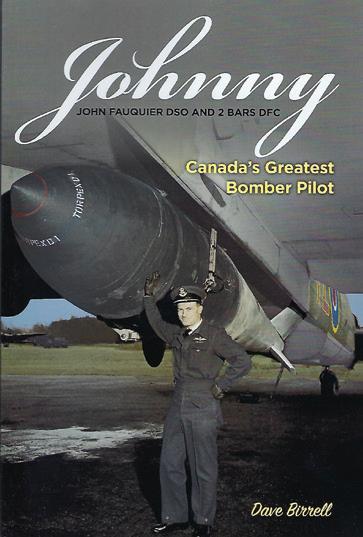

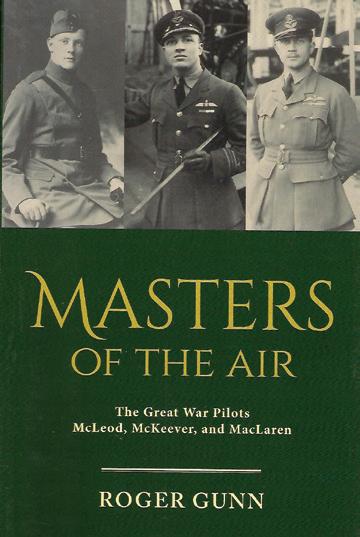

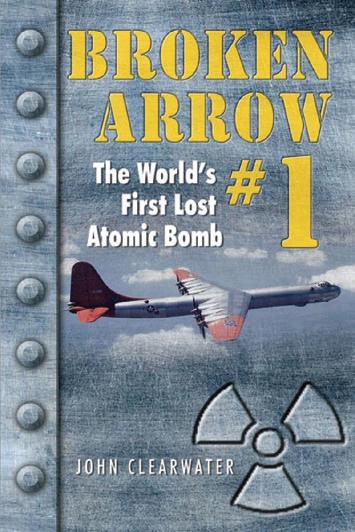

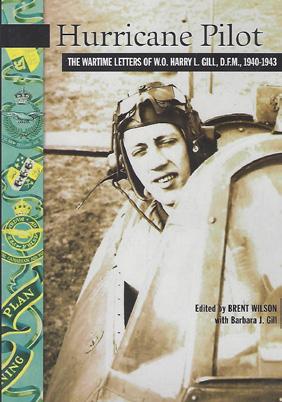

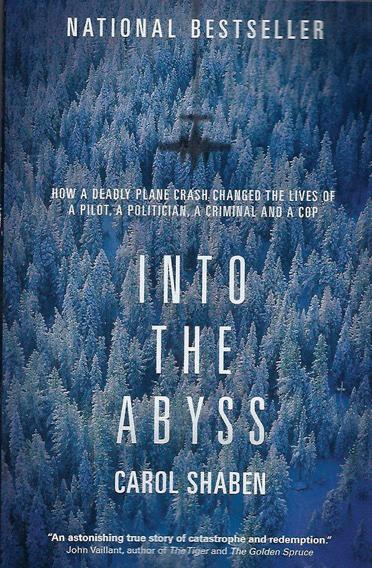

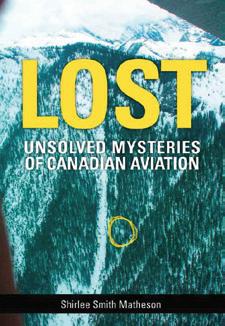

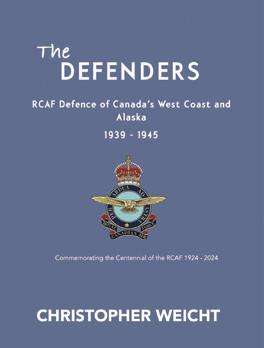

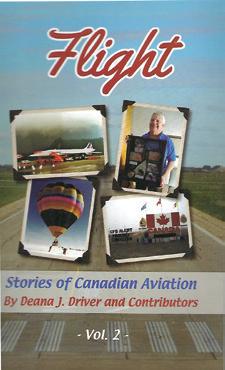

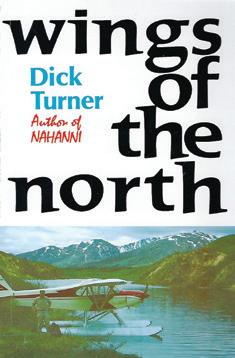

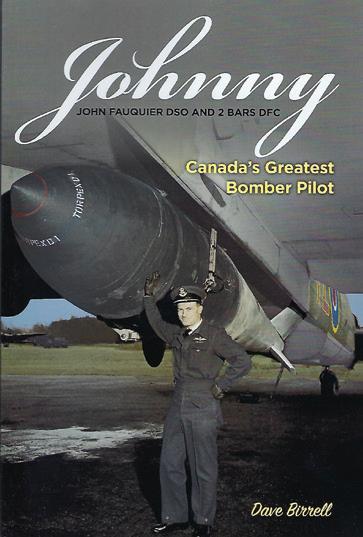

50 / BOOKSHELF

Top aviation titles

52 / SERVICE CENTRE

Deals and offers

54 / FLIGHT BAG

Puzzle and questions

ON THE COVER

An RCAF CF-18 joins a Victory Flight Spitfire in the skies over Gatineau last summer. Two of our three features this month relate to this memorable event.

FEATURES

30 Victory Flight

Three highly skilled pilots were brought together and mated with three vintage warbirds; a Hurricane, a Mustang and a Spitfire. Learn how the Victory Flight was formed.

By Dave Hadfield

38 A Hornet & a Spitfire

In 2023, AERO Gatineau was a very special event for this aviator and was a highlight of his Air Force career. And flying a CF-18 alongside a Spitfire made it unique.

By Major Justin King, RCAF

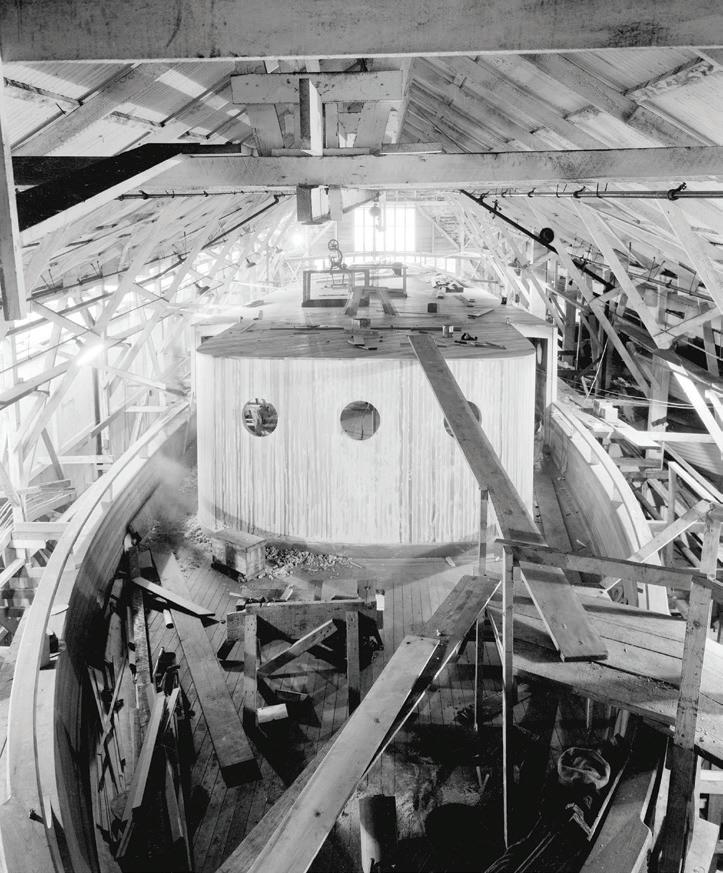

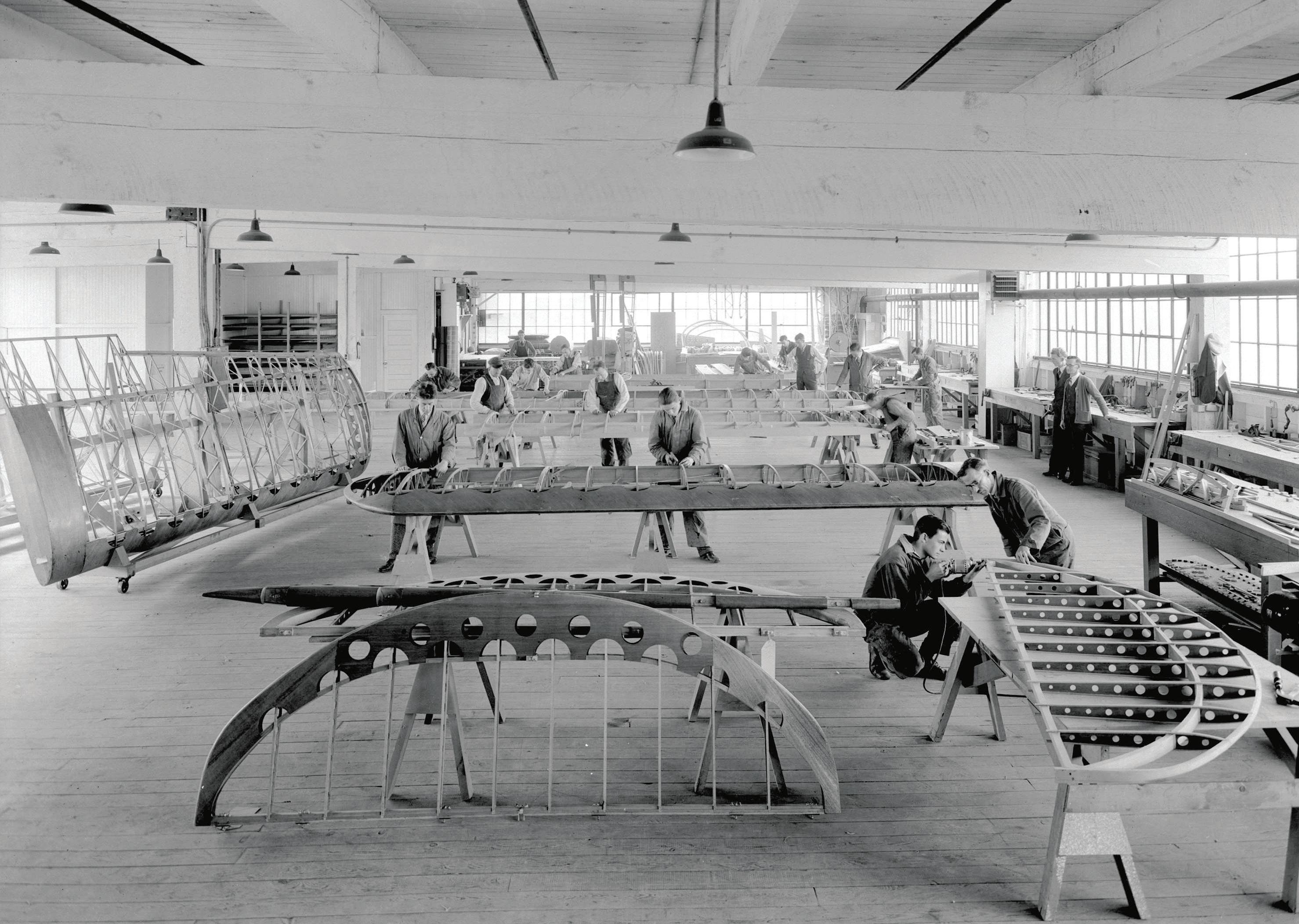

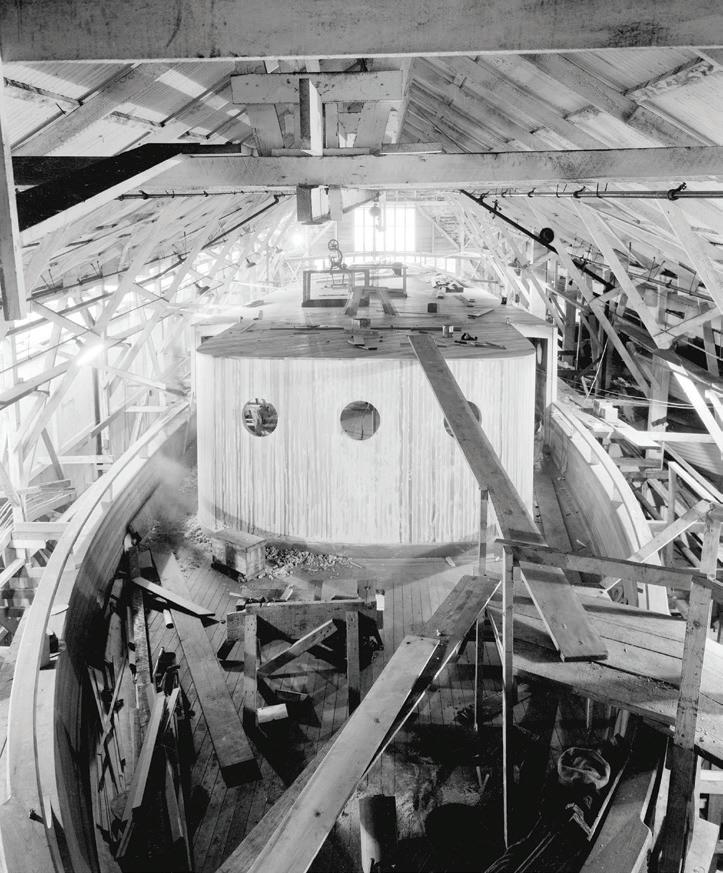

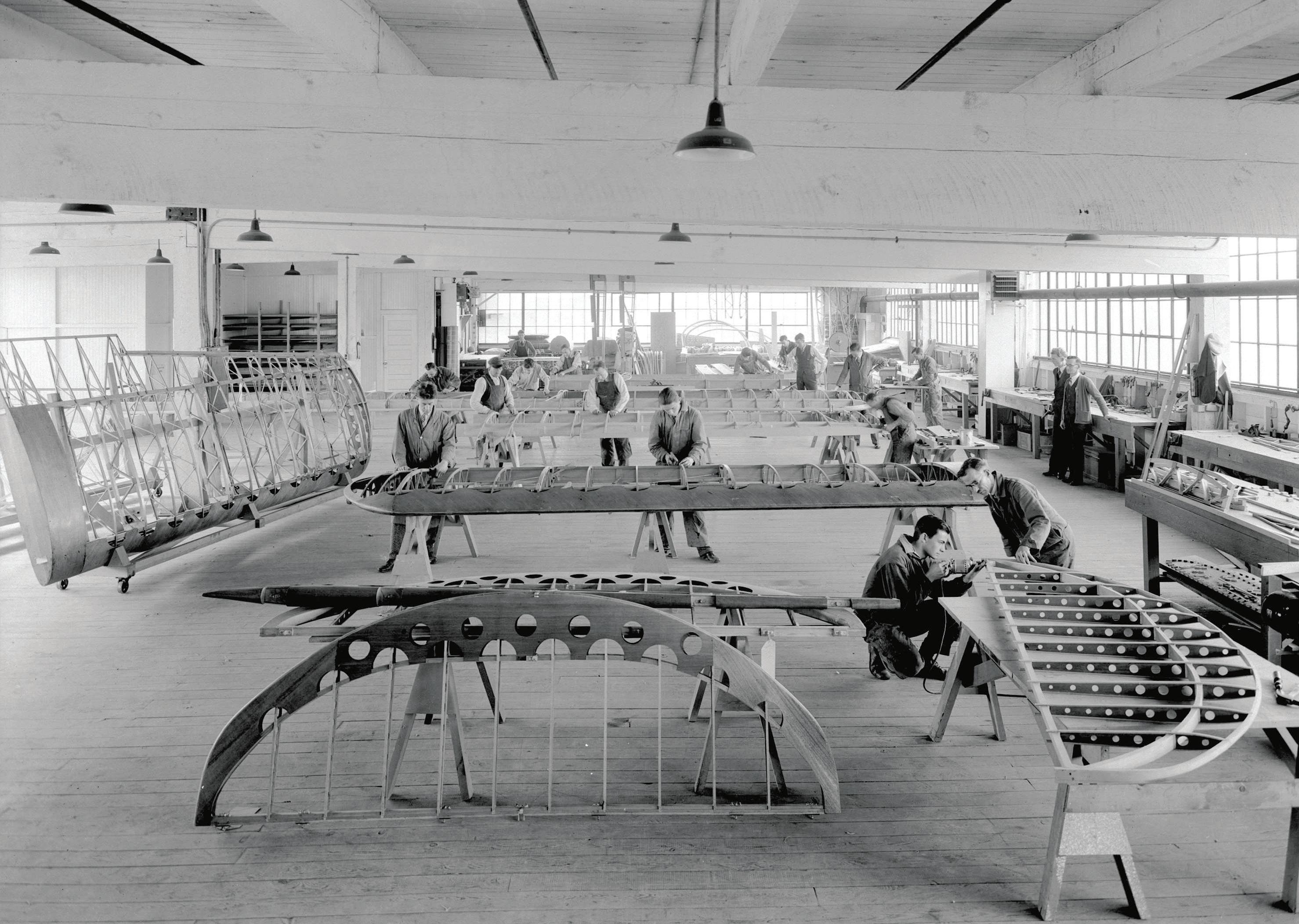

44 Boeing’s Flying Boats

Almost a century ago, William E. Boeing was active in the Vancouver area building boats, first the sailing kind then the flying kind. But it was the airplanes he built that made their mark, most of which supported the Allied war effort against the Axis powers.

By Ed Das

MAY/JUN 2024 VOLUME 34 NUMBER 3

Photo by André Laviolette

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 3

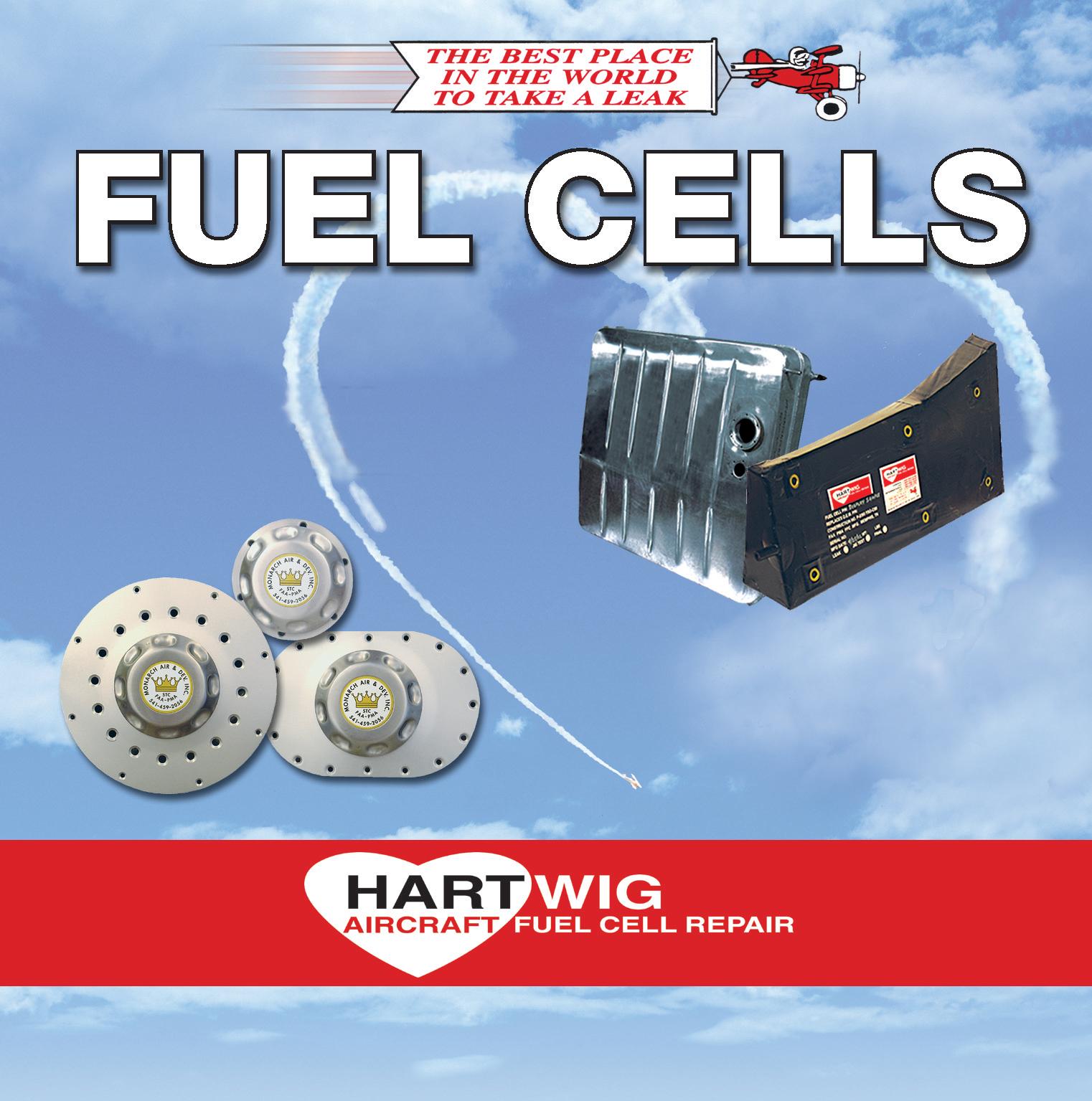

publisher + editor Steve Drinkwater steve@canadianaviator.com 604.999.2411 contributing editor Robert S. Grant graphic designer Janice Hildybrant advertising sales account manager Katherine Kjaer katherine@canadianaviator.com 250.592.5331 director of consumer marketing Craig Sweetman ADMINISTRATION group controller Anthea Williams awilliams@opmediagroup.ca Office 604.428.0261 subscriptions Marissa Miller marissa@opmediagroup.ca 1.800.656.7598 Canadian Aviator is published six times a year: Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/Jun, Jul/Aug, Sep/Oct, Nov/Dec Canadian Aviator Publishing Ltd. 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 3Z3 Phone: 604.999.2411 canadianaviator.com Printed in Canada. Agreement No. 42583014. Postage paid at Vancouver, B.C. Contents copyright 2024 by Canadian Aviator Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. ISSN 1492-0255. Return undeliverable Canadian mail to Circulation Department. 802-1166 Alberni St., Vancouver B.C. V6E 3Z3. From time to time we make our subscribers’ names available to reputable companies whose products or services we feel may be of interest to you. To be excluded from these mailings, just send us your mailing label with a request to delete your name. Publications Mail Registration No. 10939. 50% SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1.800.656.7598 CanadianAviatorMedia @canadianaviatormag canadianaviator.com subscription inquiries admin@canadianaviator.com subscription rates 1 year (6 issues) $26.00 (Taxes vary by province); Outside Canada: $32.00 per year editorial submissions Editorial contributions should be sent to the editor by email in plain text with high-resolution photos attached: steve@canadianaviator.com MONARCH PREMIUM CAPS Premium Stainless Steel Umbrella Caps for yourCessna177 through210 www.hartwigfuelcell.com info@hartwig-fuelcell.com US: 1-800-843-8033 CDN: 1-800-665-0236 INTL: 1-204-668-3234 FAX: 1-204-339-3351 NEW TANKS - 10 YEAR WARRANTY Keeping aircraft in the air since 1952 SPECIALIZING IN BEAVER & OTTER FUEL CELLS QUOTES ON: Cherokee Tanks Fuel Cells & Metal Tanks Repair, overhauled & new Technical Information or Free Fuel Grade Decals Keeping aircraft in the ROTECH MOTOR LTD. 1-(236)-600-0137 SALES@ROTECHMOTOR.CA ROTECHMOTOR.CA AUTHORISED ROTAX DISTRIBUTOR XPS AVIATION ENGINE OIL Formulated specifically for Rotax aircraft engines. FORMULATED FOR THOSE WHO CARE. 4 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

The Recreational Pursuit of Business?

As someone whose occupation requires a certain awareness of aviation events in Canada, I subscribe to a daily summary of TC’s Civil Aviation Daily Occurrence Reporting System reports (CADORS). I only read the details of a few of them, and not every day. However, several in particular catch my attention and I read further. They are ones classified where the aircraft use is classified as “Recreational.”

Most reports are initiated by Nav Canada ATC employees. In completing the report, they must choose the CAR sub-part option that corresponds with the aircraft type. All the CAR Part VII subparts, which cover the different commercial operations, are listed, as is 406 (Flight

Training) and 604 (Private Operators). The remaining options are Other, Recreational Aviation and Unknown.

Sub-part 604 is for aircraft operating under a Private Operator Certificate, which is required for most operations of certain larger aircraft, such as those greater than 12,500 lb, turbine-powered aircraft and pressurized aircraft with six or more passenger seats that carry cargo or passengers.

What is disturbing, however, is that the operation of aircraft owned by companies or individuals that do not meet the 604 criteria are lumped into the Recreational Aviation category. Over the years I’ve seen many reports of relatively expensive, high-performance piston aircraft

that the system classifies as recreational aircraft. Just last week there was a report of a corporately owned Cessna 340 that violated an airspace restriction that required ADS-B. The report, and others like it, implied that the pilot was “out having a good time flying around.”

Regardless of the infraction, what is evident is that there is a chunk of General Aviation aircraft that are used as business tools but whose use is considered recreational flying by Nav Canada and the federal government.

Is it not surprising, then, when senior managers and bureaucrats are presented with aviation statistics, decisions are made without regard to the legitimate business use of many aircraft types?

WALKAROUND EDITORIAL BY

DRINKWATER ONE STOP SHOPPING • LOWEST PRICES • SAME DAY SHIPMENT ORDER YOUR FREE 2023-2024 CATALOG!

STEVE

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 5

CKG Aero Announces Battery-Electric Kit Plane

FISHER DAKOTA HAWK GAINS ELECTRIC OPTION

In 2022 Fisher Flying Products of Dorchester, Ontario, an accomplished kit plane manufacturer, was acquired by Arun Modgil of Mississauga’s CKD Packaging and renamed CKG Aero, and they have recently announced the company’s latest offering, a battery-electric version of the Fisher Dakota Hawk, the CKD Aero Dakota e-Hawk.

Propelling the two-seat (side-by-side) e-Hawk is an electric motor developed and manufactured by Kite Magnetics of Australia, the KM-60. Flight time of over one hour can be achieved if paired with an appropriate high-capacity battery, according to CKD Aero.

“With Kite Magnetics’ propulsion system’s incredible efficiency and CKD Aero’s commitment to excellence, this partnership is poised to redefine what it means to fly, making the skies more accessible, more sustainable, and more exhilarating for everyone,” Modgil, CKD Aero’s CEO, said.

Kite Magnetics’ KM-60 motor generates 60 kW, or 80 hp, while its KM-120 powerplant generates double to power and is intended for larger aircraft. The motor uses a newly developed and trademarked magnetic material developed by Melbourne’s Monash University called Aeroperm. Kite Magnetics says this material has allowed for lighter, more efficient electric motors.

CKD Aero and Kite Magnetics are planning to showcase the Dakota e-Hawk at AirVenture 2024 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin in July.

French Alternative to CL-415 in Development

CANADIAN CONSULTING COMPANY TO ASSIST

Hynaero, a French company based in Bordeaux, announced in February that it has contracted Montreal-based Altitude Aerospace to assist with the design and engineering of their Fregate-F100 amphibious water bomber, a clean-sheet design that the company touts as a next-generation aerial firefighter aircraft, ready to take on the growing threat of wildfires around the world.

With a payload of 10 tonnes of water, a cruising speed of 250 knots and an endurance of up to four hours, the company admits it is challenging de Havilland Canada’s CL-415 head-on, targeting both private and government markets. The aircraft will feature fly-bywire controls and a glass cockpit.

“This agreement represents, in addition to the know-how and experience of Altitude Aerospace, significant financial

COMPILED BY AVIATOR STAFF WAYPOINTS

EAA CHAPTER 132 KITE MAGNETICS

6 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

A U.S.-registered Fisher Dakota Hawk with a conventional piston powerplant.

“We are delighted to collaborate on this ambitious and innovate new program, which is completely in line with the strategic positioning of the group and, moreover, with our geographical development in France.”

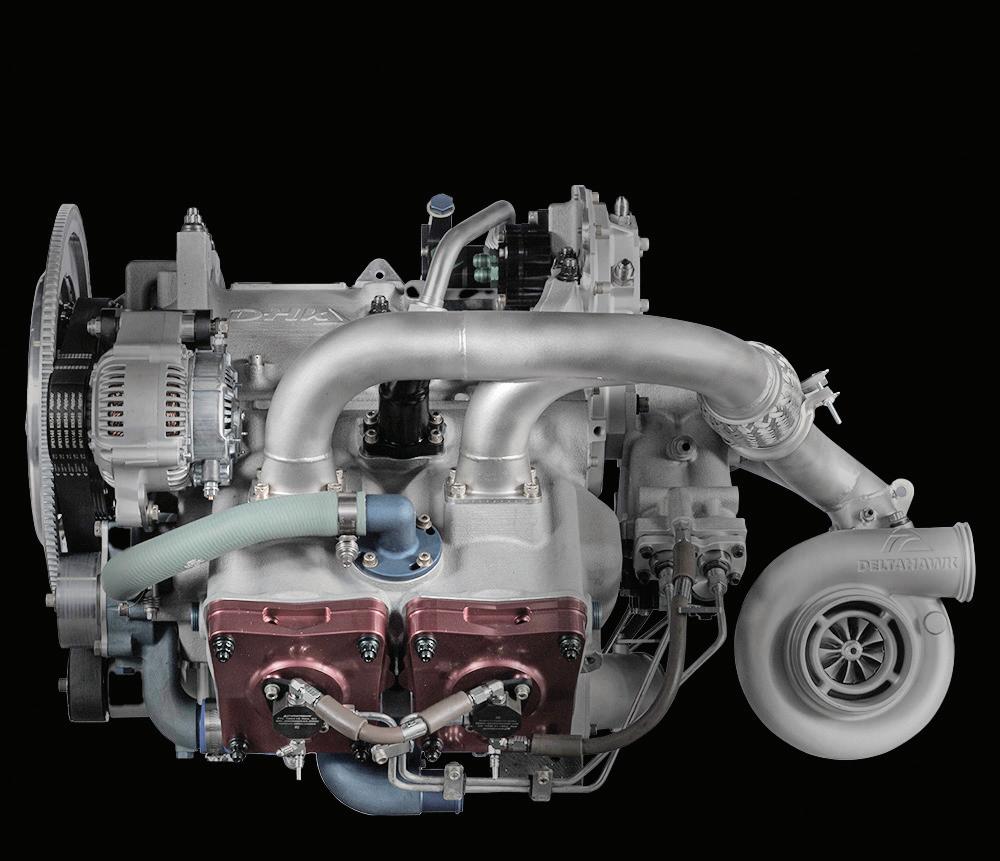

DeltaHawk Expands Engine Lineup

support and a major step forward for the next phases of our aircraft program,” said Hynaero’s co-founder and president David Pincet.

Altitude Aerospace was founded in 2005 and employs more than 170 engineers in Montreal and at its two branch offices in Toulouse (France) and Portland (Oregon).

“We are delighted to collaborate on this ambitious and innovate new program, which is completely in line with the strategic positioning of the group and, moreover, with our geographical development in France,” Altitude Aerospace Group president Nancy Venneman said.

Hynaero, which has obtained funding and support from local, regional, national and European levels of government, hopes to have the Fregate-F100 ready for the market by 2031.

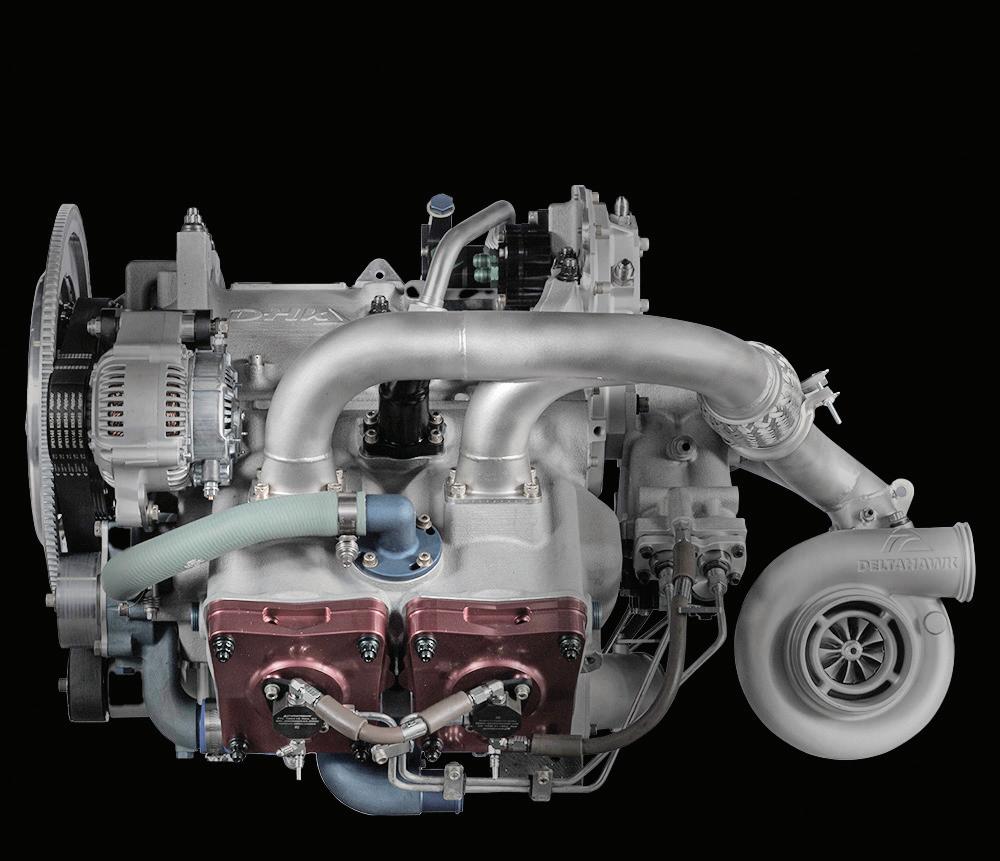

DeltaHawk Engines of Racine, Wisconsin has announced two new jet fuelburning piston engines to their existing 180-hp DHK180 offering. The two new versions are the DHK200 and DHK235, generating 200 hp and 235 hp respectively. All three engines use the same 202-cubic inch (3.3 l) block with 4-inch bore by 4-inch stroke cylinders.

The company’s DHK180 was certified by the FAA in May 2023 and production is expected to get underway later this year. Certification of the DHK200 and DHK235 is expected this year with production of the former to begin this year and the latter in 2025.

“Following FAA certification of the DHK180, customer interest and reservation deposits from aircraft OEMs and individual owners in both certified and experimental markets has been extremely high,” said DeltaHawk’s CEO Chris Ruud.

DeltaHawk highlights several advantages to their engines, citing among other benefits its ease of starting in both hot and cold conditions, 40 percent fewer parts and 35 to 40 percent more fuel efficient than Avgas equivalents and its ability to burn a range of jet fuels, including SAF. Another significant advantage is the elimination of lead contamination of the environment. The price point targeted by the company for its DHK180 is U$100,000.

As reported in our Nov-Dec issue, Bearhawk Aircraft is offering the DHK180 on their four-place model, the Four.

Formed in 1996, the DeltaHawk Aircraft struggled over the years to advance their vision of an alternative to Avgas-burning piston engines. It wasn’t until 2015 that the company received a significant investment that led to the certification of the DHK180 last year, growing their workforce from the original three employees to over 60 in 2019. To date, DeltaHawk says that over U$100 million has been invested in the project.

MORE JET FUEL-SIPPING PISTON ENGINES BECOMING AVAILABLE

Nancy Venneman, president, Altitude Aerospace Group

HYNAERO

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 7

DELTAHAWK ENGINES

I came across reference to SaintHubert-based 429 Squadron in Robert Grant’s article “De Havilland’s Venerable Buffalo” (Mar/ Apr 2024). Wait, I thought, isn’t that supposed to be 643 Squadron? As a 15-year-old Royal Canadian Air Cadet I attended Escadron 643 Squadron at Saint-Hubert in 1967, not far from our home on Montreal’s South Shore. A little digging revealed that RC Air Cadets have their own squadron designations, and that 429 (Tactical Transport Unit) was established at Saint-Hubert in 1967. The 429 was disbanded in 2005 but reactivated in 2007 (renamed Transport Squadron). In addition to the de Havilland Buffalo featured in Grant’s article, 429 used Lockheed Hercules and Boeing Globemaster III in support of Canada’s operations in Afghanistan.

René R. Gadacz Grande Prairie,

Alberta

Your Source for Canadian Aviation Literature aviatorsbookshelf.ca AIRMAIL

The

Squadron Memories

Send us your letters Canadian Aviator welcomes reader letters on topics of concern to Canadian pilots and the aviation industry. Please be brief, to the point and polite in your submissions. Email Steve Drinkwater steve@canadianaviator.com BY ROBERT S. GRANT A my shoes slammed into the snowbank, reminded myself that close acquisition rated higher than shivering scalp. Media relations officer Philippe Tremcliffe’s pristine premises. Now, after stumbling through 15-knot gale, staggered into the The brilliant yellow aircraft came across as breathtaking in brilliance and size. Museum director-general Christopher Kitzan explained wingless exhibit. On October 11, 2023, six flatbed transport trucks had delivered the prize from CFB Trenton where the sleek example RCAF veteran technicians and CASM’s Réjean The existence of 452 and another 125 from 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2000-powered DHC-4 Caribou. Efficient and record setting for its era, de Havilland acceded to US Army turbine transport project capable of hauling almost double the load. flew on April 9, 1964, as the DHC-5A and the RCAF ordered 15, designated as CC-115s by Story, averaged $1,550,000. The museum’s July 1967, example initially carried civil registration CF-QVA with serial number 06 before Squadron. Unlike most military acquisitions, 452 reverted to the same lettering in 1972 on lease to de Havilland for icing trials before carrier, 12,500 pounds could be taken aloft — more than twice the load of Douglas DC-3. With outstanding STOL capabilities, thanks and spoilers, 452 could carry 41 troops, so said De Havilland News Backgrounder. With full fuel, range reached as much as 1,391 DE HAVILLAND’S VENERABLE BUFFALO A Canadian Legend Takes Rightful Place At CASM 8 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

GEAR & GADGETS

First Aid/Survival Kit

Crashkit International Corporation, a company based in Medicine Hat, Alberta, offers a series of first aid kits designed by, and made for, pilots. They are designed such that, once opened, they are impossible to close again. This is because their carefully selected and packed contents are compressed into a Pelican case designed to withstand an aircraft crash. The kits are available in a variety of sizes to accommodate various aircraft passenger capacities. At the lower end of the product line is their Crashkit Lite series, designed for 2-, 4- ,6- or 10-passenger aircraft. The Crashkit 4Lite contains 190 unique and essential items for shelter, signal, fire and water purification. This product is 27 cm x 24.6 cm x 17.4 cm and weighs 4.31 kg. About C$885. Learn more at, and available from, crashkit.ca

Windshield Cleaner

McFarlane Aviation of Kansas offers an aircraft window cleaner that they say, “This stuff is so D A M good we had to share it!” Offered in three sizes, Aircraft (1.5 oz.), Hangar (16 oz.) and Refill Size (1 gallon), D A M Window Cleaner is a liquid spray with no ammonia and only a trace of alcohol. It uses carnauba wax and polymers to fill in minor scratches, leaving a slick surface that repels dust. They claim it is safe on all surfaces. It can be used on other acrylic surfaces, such as those found on motorcycles, boats and RVs. From C$7.95.

Learn more at, and available from, mcfarlaneaviation.com and aircraftspruce.ca

Aircraft Tug

As each year adds up and our aircraft do not get lighter or easier to handle, maybe it’s time to think about an aircraft tug. AC Air Technology of California offers a range of remote-controlled battery-operated tugs that are designed to handle airplanes from 1,500 to 21,000 pounds, as well as a model designed for helicopters. On the lower end of the scale, AC’s TrackTech T1V2 - Compact Tug can handle airplanes with up to 3,500-pound gross weight and tire sizes from 5 x 5 to 6 x 6. They can also be quipped with LED lights. A tailwheel adaptor is also available. About U$4,700. Learn more at, and available from, acairtechnology.com

Kneeboard

There never seems to be a single kneeboard configuration that meets everyone’s tastes. U.S.-based Lift Aviation is offering a pair of kneeboards, the Navigator T-1, that they dub “non-slip workstations.” Made of nylon or leather, they sport a removable EVA knee pad and are designed to support tablets up to the size of an iPad Mini. The Velco-equipped leg straps are made of silicon so they don’t slip, and there is a clear plastic document retainer on the top. It comes with an acrylic clipboard. About U$49 (nylon) or U$89 (leather). Learn more at, and available from, liftaviationusa.com

PRODUCT REVIEWS COMPILED BY AVIATOR STAFF

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 9

Just Another Islander

DEB’S SAGA CONTINUES

You read in the first episode of this epistle that I was engaged to ferry a Britten-Norman BN-2 Islander from Cambridge, Maryland to Campbell River, British Columbia. Ken, my co-pilot to be, and the buyer of the airplane had found it in the pages of Trade-a-Plane and bought it sight unseen over the phone with only the owner’s assurances that it was airworthy. We flew the airlines to Boston, Massachusetts and were dumbfounded to be advised by the airline’s agent that Cambridge, Mass. didn’t have an airport. “You’ve got the wrong Cambridge, my friends,” she laughed, when looking at the phone number Ken had from the Trade-APlane newspaper. “You want to be in Cambridge, Maryland. We can get you to Baltimore — the rest is up to you.”

So, here we are, standing at a designated taxiway at Baltimore International Airport, awaiting the arrival of the owner of the Islander to pick us up and fly us to his private airstrip in Cambridge, Maryland, a beautifully paved runway, as it turned out, and a light lunch waiting for us in the immaculate, prosperous-appearing terminal office operated by a real estate company, an airline and an aircraft sales operation. The big news happened for me when we were on final for that runway: a big high tail in the lineup of planes with a green reminder that Donald E. Braithwaite’s initials would soon appear as our tires barked on the touchdown. CF-DEB, painted in green, stood proud on the tail as did the Gulf Air logo. What a surprise!

“We flew it home across the U S of A de-registered as it was,” laughed our smiling host. “Nobody raised an eyebrow,” he added. “And that’s exactly what you should do unless

you wish to take up living here waiting for the FAA to issue you a ferry permit.” He was laughing at our alarm. “They’ve (the FAA) been making a lot of mistakes recently and found very wanting by the government. You should just get in that bird and fly home. Call yourself Canadian Civil DEB, that’s what we did.”

I looked at Ken and his eyes sparkled — this was his kind of challenge. “Let’s get airborne,” he laughed. So we flightplanned, innocently, with the FAA and were given a list of places we were allowed to land at — a long, long list. “Just those places,” said the voice. “No other airports.”

We got into the unregistered DEB, waved goodbye and took off with those two Lycomings snarling their best from the 24-squared settings from the recently top-overhauled IO-540s. “Nice,” I thought as we topped the required 8,000 feet for VFR passage through the Washington National Control Zone, which gave us vectors for Louisville and put us on flight following.

“Where in hell’s Louisville?” asked Ken. “Got me,” I said, “but it is not on the list of airports we are allowed to land at.” Ken replied, “Oh, great. Then let’s land there. I need some maps.”

This wasn’t cross-country ‘Nav 101’ for sure, but Ken loved it. Louisville, by the way, is in Kentucky and is a nice, clean, neat, single-paved runway in the middle of nowhere, totally surrounded by a giant forest. The population? One man, who was very happy to sell us all his map stock and some of his 130-octane green avgas.

We now set our sights on Kansas, and I couldn’t help whistling, “Yellow Brick Road” and “Somewhere, over the Rainbow” as I recalled the Straw Man, Dorothy and that entire crew all trying to get back to Kansas City. And the dog. What was the dog’s name?

Dog notwithstanding, we did not land at Kansas. Instead, an abandoned atom-bomber base with runways built for the B-52 — wide enough for the Islander to land across the numbers.

I can’t remember that airport’s name either, but it wasn’t on the list of FAA

FLYING STORIES

HANGAR TALK WITH JACK SCHOFIELD

AIRLINERS.NET 10 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

acceptable places for a ‘Canadian Civil’ to land.

I must now admit that I am writing this without benefit of my old logbooks, which detailed the succession of landings as we augered our way across the U.S. with Seattle as our planned port of departure back to Canada. Those logbooks are in the attic of my home on Mayne Island and to get at them one needs to employ a very heavy stepladder that has been gaining weight outside in the rain. Not only that, but one needs to have the use of one’s legs, something now denied me by a syndrome named Guillain-Barré (GBS) that struck in the night recently! So, please suffer my recollections of the geography as we motor across the skies of now Colorado where we followed the old Mormon trail up and over the peaks that brought us, as it did them, to Salt Lake City. There was a lovely, paved strip at the 4,000-foot elevation, so we landed there to get gas before going for the 12,000-foot summit. The attendant was very friendly but somewhat apprehensive as he put the nozzle in our tanks.

“Are you planning to use a Canadian credit card to pay for this?” he queried. “Yes,” replied Ken, “Why?”

“We were badly bitten by some cowboy from Vancouver, B.C. Do you know where that is? He got us for about four hundred bucks.” Ken admitted he knew where Vancouver was, but assured the man of his own good credit and we were soon leaving that extra-long runway and climbing over the still-visible trail made by the Mormon migration so many years ago as they made home of their chosen Salt Lake City.

When we topped 12,000 feet, we had 200 feet between us and the rocks. Then suddenly we were at 12,000 feet over Salt Lake City as the mountain became a very sheer cliff. We let down carefully, not wanting to cool those cylinders too quickly after that long

“I am a worrywart about overhead transmission lines and, as we flew into this gorge, I got to thinking that there had to be such hazards if there was a dam generating electrical power involved.”

hard climb. It was a gorgeous day for at least a thousand miles. The salt flats, where all the high-speed testing of vehicles had taken place over the years, stretched out for miles beneath us and the lake, which gave one such extra buoyancy that perhaps we could walk on water, gleamed in the sun. We thought it a good idea to become tourists in S.L.C. and stayed overnight before taking off for our next stopover at the head of the Columbia River.

There is a long, deep gorge leading to the Grand Coulee Dam where it is possible to fly below sea level, which we commenced doing having been assured earlier by a total stranger that there were no overhead wires to worry about. I am a worrywart about overhead transmission lines and, as we flew into this gorge, I got to thinking that there had to be such hazards if there was a dam generating electrical power involved. So I did an abrupt 180, which startled my co-pilot. Ken admonished me for performing such an abrupt turnaround, but I was happy to be up where we would be back flying in well-mapped country with hydro lines clearly identified.

As we flew into Washington state with the smell of home, real or imagined in our minds if not in the air, we relaxed and enjoyed the return to familiar ground. DEB crossed the 49th parallel and I am sure I could hear a renewed energy from the two

Lycomings as they carried us up the coast of Vancouver Island and onto final at their old home at Campbell River airport (CYBL) where a Canada Customs officer awaited. We each held our breaths as he examined all the documents, ours and those of the aircraft. When he laid down the latter, he looked up at us with an astonished look on his face. He didn’t speak for quite a long pause, then, “Welcome home gentlemen.” Then, with a look as if to assure us, said, “I’m not going there!” He gathered up his stuff and walked away. He didn’t go there because we never, ever, heard a peep from any branch of government, including Transport.

When I was about to retire from flying and go into the publishing business, I got a nice job flying an Aero Commander Shrike with a 12-foot stinger in the tail to perform magnetometer readings out of Inuvik. I was to pick up this airplane in Whitehorse where I would find the beauty parked among a gaggle of other craft. The clapped-out-appearing plane parked immediately beside the spiffy Aero Commander bore the registration DEB. There was no sign of Don Braithwaite green nor Jimmy Pattison’s white and red paint. It looked to be in terrible repair.

When I finally did retire from flying, I launched this very publication, only we called it BC Aviator in the beginning. I rented office space from Viking Air in one of their Pat Bay hangars. It was a nice office in Hangar Three with a big window looking into the hangar. The tail of one of the hangared planes got in the way of a good view of the other stored aircraft. The tail had what was then a new ident of 4 letters C-FDEB. She flew every morning carrying what they call “time-sensitive mail” to Vancouver and beyond. She was painted a dull uninteresting grey, but I thought kind of a proud look to what most would consider just another BN-2 Islander.

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 11

Cookie Books and Tangled Seatbelts

A CURSORY LOOK AT WHAT PLANE FIXERS DO

THE PLANE FIXER

SWINGING WRENCHES WITH LIANA BUESSECKER

ILLUSTRATION: KATH BOAKE 12 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

Have you ever been in the boarding lounge of an airport when you hear those dreaded words, “Delayed due to maintenance”? Maybe it’s not even your flight but the plane at the adjacent gate, and still you feel an array of emotions: angry about the delay, spiteful because of course it’s maintenance — it’s always maintenance, and nervous about getting on a plane that five minutes ago wasn’t good enough to fly. You look out the window and either there’s a person out there staring up at the engine, scratching their head, or you don’t see anything — no sign of a mechanic or a toolbox or anything indicating a real issue.

What is a real issue that causes a maintenance delay? And what could possibly be broken five minutes ago that renders the aircraft not airworthy, that is fixed so quickly? The engines are still there, none of the tires look flat and both pilots look comfortably seated in operating chairs.

Welcome to Edmonton, Alberta in mid-January while it’s -37° outside (without the windchill). As an airline aircraft maintenance engineer (AME), I’ve responded to dozens of ramp calls to complete an MEL, which is a Minimum Equipment List rectification stating the aircraft is safe to fly with whatever system is inoperable or broken. Sunshine or blizzard, your local AME will be outside troubleshooting, replacing components and diving through manuals for correct operating procedures. Snags that can be signed out with an MEL rectification range vastly from a stuck engine intake bypass door, a broken overhead bin latch, or a worn-out spring of a lavatory garbage canister. In these cases, a unique set of requirements must be met, such as the lavatory being locked out so it cannot be used. If you ask any pilot, the most important MEL item on any aircraft is the coffee machine; airplanes can’t fly without at least one in proper working condition. (Spoiler alert: airplanes may run on jet fuel, but pilots run on caffeine.)

While dozens of passengers remain inside the terminal during their maintenance delay, with their faces pressed against the glass wondering if and when their plane will be fixed, the maintenance team is always working as quickly and safely as possible. I’ve spent two hours replacing a relay that usually could be replaced in five minutes. If you’ve ever had to handle 5/32" nuts in -40°C, then you’d understand how you get about 45 functional seconds before you have to warm your hands inside the truck. I’ve dealt with planes returning immediately after takeoff due to pressurization problems, only to close a small drain screw in the cabin door. And I’ve had to make the dreaded decision to tell the captain to deplane the passengers, “This plane isn’t going anywhere.”

Sometimes your maintenance delay will go beyond the 20-minute deferral process, and it isn’t just because we’re topping up the tire pressure. If the baggage cart has ripped the cargo door off its hinges, or a fuel truck has bent a propeller blade, or the catering truck has taken off the last foot of the wingtip (all of which I’ve unfortunately seen), then your plane isn’t going to be flying. When the aircraft requires simple cosmetic repairs, flight attendants will write these up in the cabin logbook or, as some maintenance personnel call it, the “Cookie Book.” We grease the wheels on the trolley cart, and tighten the arms on the tray tables, and adjust the angle of the reading light.

severely wrong. One day I had a man complain of a hole in the side of the airplane. The explanation? A window behind the forward galley had the covering slip down and daylight was passing between the interior panels. A woman once expressed that her seat was falling apart. A wiring bundle provides power to the inflight entertainment screen in the seatback, and this bundle had slipped loose from its clamps and was dangling beside her feet.

“If you ask any pilot, the most important MEL item on any aircraft is the coffee machine; airplanes can’t fly without at least one in proper working condition.”

I’ve been called to fix tangled seatbelts that a passenger refused to let the flight attendant untwist, and to re-tape down a cabin carpet because someone was having intrusive thoughts and wanted to peel the carpet all the way back. Friends have texted me as they’re boarding their flights: why is the rudder a different colour? The captain said they’d be flying unpressurized — can planes even do that? What is that awful noise the plane makes after shutdown? And why do the cabin lights flicker while the engines are starting?

Often passengers will raise questions about the airworthiness of the aircraft, and those are always my favourite reports. Because, while they always share their findings with the utmost genuine concern (and seriously, never stop), they are usually, and thankfully,

Having the answers to these questions is why I got into aircraft maintenance in the first place. I sat beside a runway watching the planes take off and land and asked all these same questions, and I couldn’t stand not knowing. I find there’s always a bit of comfort in understanding why something isn’t a concern. We all sit through the same safety demonstration prior to takeoff, yet the flight attendants never look concerned when the airplane shudders and shakes down the runway. Perhaps it’s because they have a firm understanding of the theory of aerodynamics. Or maybe they have the utmost faith in their AME, who bid them a good flight with a, “See you when you get back.”

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 13

Robert W. Arnold

WINNIPEG’S REMARKABLE MUSEUM VOLUNTEER

Strange how an evening Yuletide airplane hop can lead to a lifetime dedication to aviation. As a child in Winnipeg, Robert W. Arnold enjoyed occasional Christmas publicity rides provided by Air Canada’s precursor Trans-Canada Air Lines during the late 1950s. While gazing through the oversize plexiglass windows of Vickers Viscounts, he had no idea that one day he would be considered an expert on the four-engine British-built transport first flown in England on July 16, 1948. Arnold did not become a professional pilot roaming Manitoba wilderness nor leap northward as an aircraft maintenance engineer. At age 14, however, he

signed on with the Royal Canadian Air Cadets and studied airmanship, meteorology, navigation as well as engine and airframe basics during four of his teenage years. Later employment kept him within the sprawling metropolis of Winnipeg. One occupation in 1976 brought him to early morning groundskeeping duties at a popular golf club. The position entailed free afternoons.

“I was cruising the local telephone book and came across something called the Western Canada Aviation Museum (WCAM) near downtown Winnipeg, which started as the Manitoba Airplane Restoration Group in 1970,” Arnold reflected. “I called them and spoke with

Gordon Charles Emberley, one of the five founding members, who suggested dropping into their new facilities at 11 Lily Street.”

Emberley, later inducted into the Order of Canada as a “... driving force helping to preserve our country’s aviation heritage,” listened to Arnold’s aeronautical interests. He discovered that his first-time visitor enjoyed the hands-on aspect of ‘pulling wrenches’ and promptly introduced him to other members of the rapidly expanding organization.

For slightly more than his first volunteer year, Arnold laboured in the engine department and revelled

TALES FROM THE LAKEVIEW BUSH FLYING WITH

S.

ROBERT

GRANT

14 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

VANESSA DESORCY

in handling historical metal artifacts or absorbing fragrances of aviation gasoline, hydraulic fluids and oil. He considered himself privileged to learn from pioneers who endured austere winters and fogbound open-water seasons. Most passed on ‘tricks-of-thetrade’ and related tales of fingernails pierced by metal slivers or the stink of thawing boots. Arnold respected their contributions.

“After becoming absorbed in the outdoor aspects of museum work and airplane types, I decided to leave my full-time job and donate at least two years volunteering with WCAM,” he said. “That’s when I really gained a lot of experience but never forgot the earpiercing whine of the Viscounts’ RollsRoyce Dart engines while living almost directly under the Winnipeg airport’s hectic approach path.”

As WCAM expanded, a TransCanada Air Lines Vickers Viscount registered CF-THS, which flew with the airline from 1958 until 1974, joined the collection. Shortage of exhibit space forced temporary storage of the 88-foot, 11-inch wing-spanned aircraft at Gimli, 51 miles north of the city. A hangar had been made available, but the Type 757’s vertical stabilizer proved too tall for the structure. Arnold and four other volunteers dismantled the upper section.

The responsibilities of placing the aircraft on display in 1982 increased Arnold’s fascination for the legendary airliner. Air Canada (renamed from Trans-Canada Air Lines in 1964) added reams of documentation to the donation package. Instead of discarding excess historical material, museum management offered the files to Arnold.

“I can either blame or thank them but I’m certainly glad they let me know about reducing the collection. No wow factor here. No specific section really stands out; all the gold’s hidden deep in the pages,” Arnold reflected. “People who worked on or flew Canada’s Viscounts started contacting me and offering their related material. Many said: ‘Since you have that in your collection, it’s only right you now have this where it can be put to good use’.”

Arnold not only became a renowned expert on type in international circles, he continued dedicating hours to other recoveries and restorations. In October 1987 he participated in what became WCAM’s longest aircraft tow when moving a Lockheed Lodestar 18-56, 480 miles from Thunder Bay to Gimli. After the survey aircraft’s left main landing gear had collapsed at a Baffin Island airstrip, the airframe travelled as ship cargo to Thunder Bay’s freshwater port. Arnold and a team of like-minded aficionados completed delivery to museum storage.

Pinched fingers, spider-infested airframes and greasy ropes became routine. On one assignment, Arnold acted as a taxi pilot for a corrugated metal Junkers Ju 52/1m to activate air bottles for braking. As short-term project manager from 2019 until 2022 for Bellanca Aircruiser CF-AWR, he located, refurbished and, with help, installed a Wright 1820-32 engine while arranging with Winnipeg’s Canadian Propeller to overhaul and install the massive unit and hub mechanism for WCAM (whose name changed to Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada in 2014).

A six-day drive in July 1980 took place when a team, including Emberley, rolled away from Manitoba’s flatlands en route to Mayo, Yukon, to recover a Fairchild F-11-2 Husky floatplane manufactured in Montreal. One of 12, the rare aircraft experienced engine failure on July 12, 1979. Museum staff decided this example of Canadian ingenuity could not be left to corrode in a patch of Yukon spruce.

“We survived the slippery mud and gravel beyond Whitehorse and then helicoptered in from a mining camp lined with sleds of core samples,” Arnold said. “Three days later, the wreck was dismantled and ready for lift when we had a tense issue with a hungry black bear.”

Although the team succeeded in driving the animal away, it continued placing itself between crew and camp. Concerned that helicopter noise might cause the bear to wreak his fear and frustration on their group, they made

a collective safety call and soon, the camp obtained a substantial addition to food supplies. Today, CF-MAN awaits restoration at the “Royal.”

Robert W. Arnold possessed the aptitudes to enter the world of professional aviators or maintenance engineers. Instead of occupying cockpits or taming obstinate airplanes, he turned his knowledge and talents toward educating young and old about the fortitudes of the men and women who came before. Each one, Arnold believes, from airline presidents to loaders freezing fingers in wilderness lakes, deserve respect.

During a personal odyssey, arranged in part by a pilot-friend, Arnold experienced an eye-opening week filling fuel tanks, cleaning windshields and pumping floats of a de Havilland DHC2 Mk.III Turbo Beaver. Stationed at Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources’ Nym Lake base, 119 miles west of Thunder Bay, summer heat and seasonal blackflies became part of the drama. Worse, he helped shuffle a 200-pound apartment-size propane refrigerator into CF-OPA as high winds roiled the lake. He and his workmates barely escaped injury when the cumbersome object slipped on the water-streaked floor.

“That week certainly cemented my point of view of aviation’s pioneers. We did almost everything during good weather and mostly in a controlled environment. My predecessors were not so fortunate,” said Arnold. “They did the same work and much more in not-sopleasant places from +40°C to -40°C in bug-infested muskeg, lakes and bushes with likely forced landings in inhospitable terrain far from civilization with limited or zero communication.”

Passengers constantly migrate from Winnipeg’s nearby airport terminal and school buses trundle in with excited children eager to enjoy “things with wings” and the stories that go with them. Beyond the exhibits and usually out-ofsight, Arnold ensures that restoration and recoveries progress. In quiet times, he often ponders the legacy of the massive single spar Vickers Viscount he boarded as a child on a long-ago winter night.

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 15

My Panel Upgrade

A TECHNOLOGICAL LEAP FORWARD FOR A 2002 CESSNA 182T

Those of you who follow this column may recall my efforts a few years back to find a light twin we could fly after retirement from the airline. In the end, the search didn’t turn up any winners, mostly owing to the dearth of worn-out old multis suddenly appearing on the pages of Controller and in the hangars of aircraft brokers. Even our bulletproof Plan B tanked, the one where we would by a vintage Piper Seneca from 90-year-old potato-farming Uncle Virgil in Idaho, then launch into a total restoration project. I’ll blame that failure on the blight.

My wife suggested that we consider upgrading the panel in our 2002 Cessna 182T. Great idea, Karen. But what continued to irk me was that, apart from an attitude indicator failing during the early days of COVID, the factory-installed gear was all working great. The ongoing fly in the proverbial ointment, however, was our need for ADS-B capability to provide for hassle-free flying in U.S. airspace (with Canadian ADS-B airspace requirements soon to follow). In case you haven’t heard, ADS-B boxes require a WAAS GPS data source, which our vintage KLN 94B GPS was never designed to provide.

The plan started out simply and affordably enough. Replace our legacy Bendix-King GPS with a new Garmin GNC 355, then add a diversity transponder to satisfy ADS-B Out requirements. That should do it ... right? Soon after came, “And while we’re at it, why not spring for a new Garmin audio panel, one compatible with the digital transceiver co-located in the GNC 355 Navigator?” Then things really got out of hand.

Before going all-in on a new avionics configuration, I thought it best to consult

the Air Regs. CARS 605.18 is clear where IFR flight is involved. It details the requirement for a second navigation source that would allow either continuing an instrument approach, or diverting to an alternate airport should a single navigation source fail. The obvious question is then, “Why not just install a Garmin GNC 650 or 750 since those navigators come with built-in VOR/ILS receivers? Wouldn’t this satisfy the TC equipment redundancy requirement?”

The answer is ... maybe. With only one satellite receiver on board, carrying out a GPS missed approach, should your single navigation receiver fail, is most likely impossible. Even with a VOR receiver on board, you would require both a VOR on or near the field, not to mention an alternate missed approach procedure. Add to that the ability to actually navigate to an alternate airport. The obvious solution was installing a second GNC 355.

At my airline, GPS approaches are actually the preferred procedure. Virtually every destination we fly our Skylane to also provides the same kind of GPSbased instrument let downs. LPV accuracy (Localizer Performance with Vertical Guidance) allows for minimums approaching those of a conventional ILS. Using Garmin’s Advisory Glide Path function, even non-precision LNAVs begin to resemble Constant Descent Angle approaches, the industry-standard. The future has arrived, and it’s not one where ground-based navaids figure prominently. Saying goodbye to the legacy VOR/ILS Nav/ Coms netted a 33-pound weight reduction.

Justifying a new autopilot (A/P) was more difficult, especially since our Bendix/King KAP 140 was working perfectly. Having spent the last 35-plus years with a highly skilled colleague sharing in the flying duties, the GFC 500 seemed an acceptable stand-in for a talented first officer looking out for me. Having now flown the system, I can state unequivocally that this is one of the best autopilots I’ve ever used — in any GA aircraft.

With GPS navigators and a new A/P decided on, the splurge continued. Karen’s a big fan of glass panels in GA airplanes, insisting that our modernization project include a digital Primary Flight Display. That choice was easy: a Garmin G3X. In addition to its synthetic vision, complete with obstacle and terrain warnings and built-in flight director, the system features wind vector and true air- and groundspeed symbology. An optional engine monitor is prominent on the left side of the screen and features a Lean Assist function. At the top of the LED screen are automation and navigation modes, both active and armed.

EXPERT PILOT FLY LIKE A PRO WITH RICHARD PITTET

16 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

Not a single analog instrument survived this Cessna 182 panel makeover as can be seen in these before (above) and after (below) photos.

NEW EQUIPMENT LIST

GNC 355 GPS/COM (2)

GMA 345 Audio Panel

G3X Touch PFD with optional engine monitor

GTX 355 Diversity ADS-B Transponder

GDL 52R ADS-B “In” Remote Datalink, plus XM Weather and Music

GFC 500 Autopilot

G5 Attitude Indicator

“Was it all worth it? That depends entirely on your mission. What is undeniable is the remarkable situational awareness this new panel delivers.”

Along with airspeed and altitude tapes, the G3X even comes with a flightpath vector, augmenting the traditional attitude indicator’s pitch information. It even has a go-around button, pitching command bars to your predetermined pitch attitude in the event of a missed approach. An entire article would barely cover the capability of this system. A lot of work went into designing what will probably be our one and only panel upgrade. In its final form, the presentation is now clean and ergonomic, starting with the autopilot controls sitting on the top of the avionics stack, rather than buried at the bottom, out of sight and hard to use. The G5 attitude indicator previously installed

in our 182 now resides just left of its big brother, fully capable of controlling the auto flight system should the G3X suffer a major failure. For my part, I will never again fly an airplane with a single attitude indicator in IMC, even one with two separate vacuum sources.

Was it all worth it? That depends entirely on your mission. What is undeniable is the remarkable situational awareness this new panel delivers. Given that it costs about as much as a new Corvette, it better! Needless to say, I’m a most fortunate man to have both a partner in life and airline career that allows for this degree of indulgence. I just hope Nav Canada and the FAA appreciate what I let Karen talk me into!

2010 PIPISTREL

SW USD $89,000

VIRUS

USD $299,500

2005 CESSNA TURBO 206H AMPHIBIAN USD $575,000 1980 BEECHCRAFT 58P

USD

2024

ELECTRO Please call for price

Please call for price 1962 PIPER COMANCHE 250 USD $89,000

USD $78,000 CANADA’S EXCLUSIVE DISTRIBUTOR FOR 226-666-2192 / sales@apexaircraft.com APEXAIRCRAFT.COM

1980 CESSNA A185F

$375,000

PIPISTREL VELIS

1976 PIPER NAVAJO

WE KNOW AIRCRAFT 1972

BELLANCA CITABRIA 7GCBC

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 17

Corporate Flying in British Columbia

ICY AIRFRAMES, PROPS, WINGS AND RUNWAYS

Through the airport grapevine I learned that Northwood Mills, a division of Noranda Mines Ltd. of Toronto, were looking for a summer relief pilot at Prince George, British Columbia flying their Mitsubishi MU-2 DP, CF-CEL. I quickly applied for the position and was hired on July 15, 1975.

After I had taken their in-house course on the aircraft and received training on the MU-2 operations, I was introduced to the niceties of corporate flying. I learned to operate the pressurization system and the differences of flying the Garrett TPE331 turboprop engines. The MU-2 is a complex aircraft and is vastly different than an aircraft like the Piper Navajo. For instance, it has a very small wing, and the aircraft is turned not by ailerons like most other aircraft, but by spoilers on the top of each wing. The aircraft is very fast and suitable for small airports, and it handles much more like a small jet aircraft.

hang glider, which was very, very close. We did a fighter break to the right and dumped the executives and their glasses of scotch all over the ceiling of the aircraft’s cabin. I imagine that the guy in the hang glider probably, at the very least, messed his pants. Of course, the hang glider was not seen by air traffic control radar as it was made of aluminum tubes covered with something like bed sheets. I don’t want to experience being that close again. (But I was.)

I started to fly with Futura on October 6, 1975, in Aero Commander 680E (CF-SNC) on their regular ‘bag run’ from Vancouver to Calgary and sometimes to the Edmonton municipal airport. On my first flight with chief pilot Bob Jacques, we picked up so much ice near Chilliwack Lake (remember Mount Slesse) that we had to turn around and return to the Vancouver airport where our freight was loaded on to the company Learjet 25 and flown by Brady.

I couldn’t have asked for better people to work with. Chief pilot Red Croisdale and co-captain Don Redden were very competent and capable. ‘Red’ let me live in his basement suite and gave the odd dinner.

We flew CEL on company flights throughout western Canada and the U.S. with their executives and technical personnel. One flight that was somewhat exciting was from Prince George to Vancouver during which we were in solid cloud. As we approached Vancouver, air traffic control cleared us to descend out of 20,000 feet; we were still in cloud and were coming up over Grouse Mountain in North Vancouver. Suddenly we broke out of the cloud and right in front of us was a

As the summer progressed and I knew that the summer job would soon be finished, I started to look for work that would allow me to continue doing the type of flying that had a future and that I enjoyed. I contacted Mark Brady who operated Futura Aviation Services, located in the Innotech hangar on the north side of Vancouver airport; it was one of the former RCAF hangars belonging to 442 and 443 Auxiliary Squadrons.

Brady said that he would have an opening for a pilot shortly. In the meantime, I flew occasionally with Fred May of Tradewinds in their Navajo Chieftain (CFRLR) as well as with Dwayne Aldrich who operated a corporate Cessna 421 (C-GBLA) from the south terminal of Vancouver airport.

SNC and another Commander that Futura later acquired (CF-FJR) were marginally equipped for legal instrument flight (IFR). It had no wing or propeller de-ice nor windshield heat. In fact, its only de-icing equipment were the dual heated pitot tubes that provided information to the airspeed indicator and altimeter and carburetor heat.

With these limitations, it was up to its pilot to come up with some way of surmounting the inevitable problems of winter flying over the Coast and Rocky Mountains to Calgary and return. One temporary solution that we found for this problem was the application of a product called silicone slick spray to the propeller blades and the leading edge of the wings and tail surfaces. We found that this would, for a time, prevent the formation of ice on these surfaces and give us a little more time to climb above the area where ice would form.

We tried to climb directly out of Vancouver to about 20,000 feet after going on oxygen at 10,000 feet. This usually put us in air that was exceptionally cold, where ice didn’t usually form. We then maintained that altitude until we crossed the mountains and were on descent into

A PILOT’S LIFE LIVING THE DREAM WITH CHRIS WEICHT

PHOTOS

18 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

Aero Commander 680E CF-SNC

SUBMITTED

Calgary. However, this way of doing things often didn’t work out, as we packed on so much ice that we couldn’t climb above it.

An example of this occurred in October 1975 with Bob Jacques and me in SNC. We were climbing out on V317 airway, and we started to pick up ice that soon became heavy. Without any warning, the aircraft’s wing stalled and the nose dropped out – we had to fight with it to maintain directional control and we were coming down fast. We were over Pitt Lake and called air traffic control and pleaded for radar vectors away from the mountains and out to the Fraser Valley. We were vectored to a landing on Vancouver’s Runway 08 and returned to our base. Upon getting out of the aircraft the amount of ice we saw remaining was unbelievable. There was close to six inches on the wings and propeller spinner.

One way we found that would help us get to our desired 22,000-foot altitude was to take off and get air traffic control to vector us westward, away from the mountains until we reached our altitude and then reverse course eastward to Calgary.

There was another problem I experienced on heading east in SNC. It was while climbing out eastward on V317 and after I had been given an altitude restriction by ATC of 14,000 feet. After levelling off as instructed, we advised ATC. A westbound Air Canada flight on the same airway was instructed to level off and maintain 16,000 feet, which he acknowledged to Centre. Shortly after, the airliner passed directly over us at what I estimated to be less than 500 feet. Not long afterward he called and said “sorry”, and that was the last I heard of it, but there were some loud and unprintable expletives being yelled in our aircraft.

At risk of boring the reader with stories of SNC adventures, I will relate the story as told to me about the pilot who took over from me when I was promoted onto another aircraft. This pilot who had a very interesting previous career was on the usual bag run in Aero

Commander SNC to Calgary and was in level flight at night near Golden, B.C. when he blundered into a thunderstorm. As I said previously, this aircraft had a bare minimum capability for instrument flight and certainly was not equipped with onboard weather radar. The pilot lost control in extreme turbulence and fell in a spin until the thunderstorm spat him out of its bottom, where he was able to recover control, but he had lost all his electrical systems including the radio. The story tells that he was able to see the highway and that gave him some means of navigation to his destination. He manoeuvred his way through the Rocky Mountains at night and sighted Calgary airport but was unable to communicate with the tower, so he observed the traffic on then-Runway 34, fitted himself between incoming flights, landed, got off the active runway and taxied to the FBO (Field Aviation). No-one knew he had arrived safe and sound until he cancelled his flight plan.

Futura Aviation’s fleet started to grow, and it acquired a Swearingen Merlin II-B, a pressurized turboprop aircraft from the British Columbia Telephone Company (a precursor of Telus). CF-TEL was an executive aircraft with comfortable seating for six passengers and a crew of two pilots.

The company was hiring more pilots to fly old SNC and I was promoted on to the Merlin, although I had no experience on the type and would fill the co-pilot position until I had acquired enough time on turboprop and pressurized aircraft to become its captain.

Bob Sansome and I were assigned to fly a charter for Bill Bennett, who was campaigning to become B.C. premier. We flew several flights for Bennett without

any difficulty. However, it was another story on November 22, 1975. Bennett had done an afternoon campaign stop in Kamloops after which we flew to Dawson Creek for his evening campaigning. We had checked the weather for the flight, and it was marginal at the Dawson Creek airport. We arrived overhead and visibility was very poor in blowing snow. We advised Bennett’s campaign manager of the situation and suggested that we land at Fort St. John, which had a better instrument landing system, but the manager was insistent that we had to land to carry out their commitment to the community.

The legal requirement for landing using the non-precision approach was to have visual sight of the ground at an altitude of 772 feet above it and have at least 1½ miles of forward visibility. The actual weather report at that time stated it was indefinite ceiling and sky obscured in blowing snow. We decided to give it a try and proceeded with the approach to Runway 24. We saw fleeting images of the terrain but certainly did not have the required visibility. The lights on the runway were barely visible and we made contact with the ice- and snow-covered runway – it had not been plowed recently. The propellers were put in full reverse and brakes applied. At this point I guess the right wheel hit a bare patch and pulled the still fast-moving Merlin off the right side of the runway and into the snowfield. Considerable power was applied, and the aircraft was brought back on the runway and to the terminal building.

Unfortunately, reporters from both Vancouver newspapers were on board and both gave the incident front-page coverage.

Later in the evening we took off and flew without incident to Fort St. John for another meeting. However, as we taxied to the terminal the tach-generator on the right engine failed, which meant that the Merlin would not be leaving until the part was replaced. So, company owner Brady flew up in the Learjet 25 and took them to Kelowna.

Swearingen Merlin CF-TEL at Dawson Creek, November 22, 1975

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 19

Augmented GPS – What Is It?

In the previous article, unaided GPS or raw GPS approaches were reviewed. This included the LNAV approach, with and without a calculated glideslope, and an approach style using GPS for lateral navigation and barometric altimetry for vertical navigation (LNAV/VNAV). This article examines augmented GPS and how it provides a capability identical, and arguably superior to the venerable Instrument Landing System (ILS).

Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) improves all the necessary qualities of navigation (accuracy, integrity, availability and continuity) to be an ILS replacement. When it was first conceived 20 years ago, the hope was providing a non-precision capability (250-foot approach limits). Over time, with improvements and increasing confidence in it, WAAS has evolved to provide a precision approach capability with approach limits identical to the ILS (200 feet).

The ILS infrastructure has built-in capabilities to monitor its performance continually; the WAAS monitoring stations throughout North America perform the same role in monitoring the health of the underlying GPS satellite network. In addition, a WAAS receiver has a similar capability located on board the aircraft, not on the ground. A WAAS receiver continually monitors its lateral and vertical position; if it goes outside certain bounds an alert is provided to the pilot and an instrument approach using WAAS is not possible.

An instrument landing system has a fixed position and the aircraft position with respect to the localizer and glidepath is determined by the radio signals from these transmitters. WAAS approaches, however, are entirely mathematical creations starting with the run-

INSTRUMENTAL FACTS FLYING IFR WITH ED M c DONALD

HOW WAAS

APPROACHES Source of Canadian Civil Aeronau tical Data: © 2023 NAV CANADA A ll rights reserved CYOW-IAP-3G 0 5 10 15 20 25 (NM) CYOW-IAP-3G OTTAWA/MACDONALD-CARTIER INTL, ON RNAV (GNSS) Z RWY 32 451921N0754002WVAR 14°W CYOW ATIS – 121.15 (En) 132.95 (Fr) ARR – 135.15 TWR – 118.8 GND – 121.9 SAFE ALT 100 NM 7000 WAAS Ch 80163 W32A APCH CRS 320° MIN ALT VODUL 2000 LDA 10005 CATEGORY A B C D LPV 567 (200) ½ RVR 26 LNAV/VNAV (min. -19ºC, max. 54ºC) 654 (287) 1 RVR 50 Knotsft/minMin:Sec 70370 LNAV 760 (393) 1 RVR 50 90480 110580 130690 150800 RNAV (GNSS) Z RWY 32 CYOW EFF 24 MAR 22 EFF 24 MAR 22 EFF 10 OCT 19 Canada Air Pilot Effective 0901Z 10 AUG 2023 to 0901Z 5 OCT 2023 20 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

IMPROVES PRECISION

way threshold position then mathematically computing positions of the localizer and glideslope. And with all these values emanating from an avionics database, the integrity of the database is crucial. When WAAS approaches are created, a Cyclical Redundancy Check (CRC) is used to verify that the numerical values used by the avionics are identical to the numerical values used in the procedure design.

A pilot gets a small insight to this with the WAAS channel found on the approach plate and when drawing the procedure from the database when loading the approach into the receiver. This is the WAAS channel shown on the approach plate.

Flying a WAAS approach is almost identical to flying an ILS. Like an ILS where one confirms that a valid ILS signal is being received (no flags, identification of the frequency, etc.), in the case of a WAAS/LPV approach the pilot must ensure that LPV annunciation appears

on the navigation display meaning that all the navigation requirements of the receiver are satisfied.

Since the WAAS signal is space-based, it is not subject to the challenges of the ground-based navigation such as scalloping of the glideslope, vehicle or aircraft interference of the localizer, or other issues. The ride on an LPV approach is perfectly smooth and uniform.

Older ILS installations provided a back-course approach to the opposite end of the runway; modern ILS installations no longer offer this. And like the localizer-only approach of yesteryear, WAAS does offer a similar approach known as LP (Lateral Procedure Only). This type of approach is used in unique situations where a vertically guided LPV is not possible. This could be when the final approach course exceeds a three-degree offset from the runway axis, the vertical path is too steep or other rare situations, typically found in the

mountains. In this case, the approach is a much more accurate two-dimensional approach and is flown identically to the LNAV approach described earlier.

A common question is, why are some WAAS/LPV approaches to 250-foot approach limits and others to 200-foot limits? In general, this is due to the runway classification — a non-precision runway allows approaches to as low as 250 feet while a precision runway (often associated with an ILS to the same runway) allows for 200-foot minimums. The obstacle clearance, protected area and approach lighting requirements of the precision runway are more rigorous than the non-precision runway; for most community airports, the incremental cost to achieve a precision runway standard is not worth the incremental 50-foot gain in approach limits.

In the next article we will discuss the Required Navigation Performance (RNP) style of instrument approach.

LEARN TO OPERATE IN THE AVIATION INDUSTY AVIATION MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS

Prepare for success in this dynamic industry while gaining hands-on knowledge and skills across aviation management, airline operations, data analytics, security, and more. Discover endless opportunities for growth and advancement as you embark on your aviation journey.

Learn more at bcit.ca/airportops

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 21

Can an ATC Job be Stressful?

IT’S ALL RELATIVE — BUT STILL REWARDING

Like many of my current coworkers, I attended an Air Traffic Control recruitment seminar hosted by Transport Canada in the 1990s. At the time, the country’s Air Navigation System (ANS) was run by Transport Canada who was, and still is, the regulator for all things aviation in Canada.

The host, a gentleman of about 60 years of age, completed the presentation part of the forum and opened himself up to the floor for questions. A young lady in the front row asked the inevitable, yet valid, question: “Is ATC stressful?” His wrinkled face wrinkled just a little more as he searched for an answer. Eventually, he said, “Well, I’m 28 years old.”

The job of an air traffic controller is generally considered to be one of the more stressful jobs out there. You won’t get an argument out of me.

Different people respond to different stressors differently. A friend of mine is a former RCMP officer. I had the eye-opening experience in the distant past of doing a ride-along with him. At the time, someone from the general public, with prior permission, could spend all or part of a shift with an RCMP officer. I was floored by what he had to do that evening. I would never be able to handle it, yet he seemed to handle it easily, taking everything in stride. I’ve known him for years and he just adapted to it all. I don’t have to be a doctor to know that I’m not suited for that job either. People asking for help, but then not taking the advice, would eat at me. Having to deliver bad news to a patient or the relatives left behind would be a tough ask, and I believe it would leave me hollow. Others seem to handle it well.

The stresses that many other professions would present wouldn’t be kind to me, either.

But this one, I like. I’m interested in aviation, but don’t want to fly for a living. This career keeps me current in the industry, just in a different sense. I get to learn a number of things that cater to my interests, and even if I’ll never directly use them, they help me in my duties.

But there is stress. Seeing converging aircraft and having to try to make the best choices for everyone involved to accommodate safety and efficiency all while keeping a sense of order in the skies can be a challenge, especially with rapidly-changing, potentially dire circumstances like severe weather.

The unusual situations presented can leave you thinking deeply to the point of distraction. Be in air traffic control long enough and you’ll see some interesting things develop.

For example, over 25 years ago I was the last controller to talk to a pilot before the plane he was flying crashed. I sat in wonder for hours. Did I say something that misled the pilot into taking a course of action that proved to be unsafe? Could I have seen the situation developing and said something to prevent it from happening in the first place, but failed to see it? Did my actions (or inactions) contribute to the outcome in a way I should have seen?

News eventually broke. Fortunately, though there were some injuries, everyone survived. I was also found to have done nothing wrong in terms of my actions taken or the words I spoke. Still, that incident left an impression on me that is still as fresh

today as it was that night.

Then there is the vast number of situations over my more-than-30 years that I have witnessed and participated in when I fed pilots information, hoping to help them make better decisions. More often than not, they took the advice or information and chose differently, but sometimes they didn’t. When they don’t, it leaves one sitting and waiting to see what will happen in the end, all

VECTORS

ATC

VIEWPOINT WITH MICHAEL OXNER

22 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

while still trying to keep up with the rest of the traffic in one’s airspace.

Does this sound like I’m trying to dissuade you from looking into becoming an air traffic controller? I hope not.

The ATC system is always looking for good people. Nav Canada, the nation’s ANS provider, has a website that opens the door to ATC recruitment. There is a process to go through, and it

will take some time since there is only so much capacity for training, but if you manage to get through, the career can be a rewarding one.

The pay is good. The hours in many facilities include work on weekends, evenings, holidays, and overnights. For some people like me, that works. It can be hard on family life but, overall, I prefer the variety of shifts.

It can be stressful, yes, but in my

view, the stressors involved are different for this job compared to others.

If you’re looking for a new path, you may want to explore ATC as an option. Start by checking out Nav Canada and the recruitment links on the website (Careers). It’s a lot of work, with a lot of information to absorb, but it’s a career like no other, even with the commonalities it may share with some others.

CANADIANAVIATOR.COM 23

Nav Canada uses advanced, state-of-the-art technology to manage air traffic.

NAV CANADA

The Perils of Transitioning

SWITCHING AIRCRAFT TYPES, OR EVEN AVIONICS, HAS ITS RISKS

The thrill of taming a new aircraft type is unparalleled. However, navigating the transition smoothly requires a healthy dose of respect for the unfamiliar and a little help from a qualified mentor.

Airport hangars are filled with stories of aircraft transition experiences going sideways. Unfortunately, so are accident files. Statistically, the first 50 to 100 hours in a new aircraft type are particularly dangerous. That explains why some insurance companies require that new aircraft owners or renters fly with an approved instructor for a minimum number of hours before going solo.

Traditionally, transition training focuses on the numbers and aircraft

systems. But there is more to a successful transition than mastering technical data. Switching aircraft means changing operating patterns, visual and audio clues, and mindset.

Mastering the technical data is a matter of studying the pilot manual. That is where we find everything the aircraft manufacturer decided to share with aircraft operators. Remember the 737 Max fiasco? Boeing chose to keep information about the troublesome MCAS system out of the pilot manuals. In addition, it did not install a yoke kill switch designed to stop runaway trims like most B737s have to ensure the Max’s MCAS could operate unchallenged. The devil is in the details. Nothing is

truer than when it comes to manuals. They are full of “by-the-way”small notes that might make the difference between a safe flight and an accident. Be especially wary of hard-to-spot differences between aircraft models. It is easy to make assumptions when aircraft are visually similar. This advice applies to different versions of avionics software as well.

Studying the manual also allows pilots to get into the manufacturer’s mind and form an intimate relationship with the aircraft’s spirit. Each aircraft is designed to respond to a need and provide an experience. Engineers come up with different approaches to meet the stated goal. Understanding their philosophy

RIGHT SEAT ALWAYS LEARNING WITH MIREILLE GOYER

24 CANADIAN AVIATOR MAY/JUN 2024

Switching from one single-engine type to another, or a twin-engine model to another, needs well-planned-out transition training, even if the aircraft are from the same manufacturer.

PIPER AIRCRAFT

facilitates the transition because procedures make sense.

For example, an aircraft designed for bush flying is usually more manoeuvrable than an aircraft intended for IFR operations, where stable flight lowers the pilot workload. Both might hold certifications for additional types of operations but will be easier to manage in their primary role.

Nothing beats a series of stability exercises to understand an aircraft’s inherent behavior.

aircraft or to adjust to the wings getting in the way when switching between high- and low-wing aircraft. What pilot has not found him- or herself unconsciously matching the ‘slow’ landing speed when driving a motor vehicle after a flight?

“What pilot has not found him- or herself unconsciously matching the ‘slow’ landing speed when driving a motor vehicle after a flight?”

Explore and record the performance output (speed and altitude change rate) for various pitch/power/trim inputs. Try different bank angles and observe the resulting responses (resistance to roll, steady, increasing roll) to determine the bank angles to avoid when things get busy. After becoming comfortable with the normal behaviour, it is time to test the edge of the envelope with slow flight, stalls and emergencies.

Mastering avionic operation from one aircraft to the other has become one of the transition process’s most time-consuming and tedious phases, especially in general aviation, where fleet standardization is rarely an option. Manuals for modern navigation systems are often much thicker than their aircraft counterparts. While many standalone avionic simulators are available, they rarely allow pilots to experience how the various avionic units installed interact with each other during normal operations and under different failure modes.

Becoming familiar with the textbook differences on the ground is the first step. Flying the new aircraft is next, to learn physical and sensory differences. There is no substitute for actual exposure.

A good simulator can help get pilots accustomed to how and where to reach. Still, it cannot fully prepare pilots to approach the runway at twice the previous aircraft’s speed and vice versa when switching between high- and low-speed

Unconsciously reverting to old habits when under stress or distracted can be as much a source of errors as insufficient knowledge when transitioning between aircraft. For example, many fuel exhaustion incidents started with the pilot switching fuel tanks to OFF on a new plane. Early in the transition process, checking and re-checking is a wise and healthy habit. A humble mindset is essential.