Region of Study

4

Figure 1: Map of Southeast Asia

THAILAND GULF OF THAILAND ANDAMAN SEA MALACCA STRAIT CAMBODIA LAOS VIETNAM BURMA MALAYSIA THAI BUDDHIST THAI MUSLIM 1 1 CHUMPHON 2 RANONG 3 SURAT THANI 4 PHANG NGA 5 PHUKET 6 KRABI 7 NAKHON SI THAMMARAT 8 TRANG 9 PHATTHALUNG 10 SONGKHLA 2 3 5 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 SATUN 12 PATTANI 13 YALA 14 NARATHIWAT 11 12 13 14 THAILAND

Figure 2: Religions of the Pak Tai People

Southern Thailand

Geography

Located on the Malay Peninsula, Southern Thailand is a narrow and mountainous region flanked by the Andaman Sea to the west and the Gulf of Thailand to the east. Its bordering nations, Burma to the north and Malaysia to the south have historically allowed Southern Thailand to become the hub for international trade and a melting pot for religion (Figure 1).

Consisting of fourteen provinces, the northern provinces of Chumphon, Ranong, Surat Thai, Phang Nga, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Phuket, Krabi, Trang, Patthalung, and Songkhla were territories of the ancient Thai empire and were the breeding ground for Theravada Buddhism 3 .

Its southern provinces of Satun, Yalat, Narathiwat, and Pattani had been under the control of Malaysia when Arab traders spread Islam to the peninsula (Figure 2). With diverse religious beliefs, the spread of other cultures and knowledge, Southern Thailand’s geography helped transform the stilt house into a complex style of architecture.

Climate

With its proximity to the sea and its slightly northern latitude of 5-10°, Southern Thailand is very hot and humid tropical region rich with vegetation and biodiversity due to its heavy precipitation. With the mountain ranges splitting the region longitudinally, the winds alternate from westward winds to eastern winds creating a wet and dry season with monsoons most common between May and November. The rain brings forth a plentitude for subsidence

3 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

5

farming of rice, durian, mangosteen, coconut, and bananas, but also a diverse selection of building materials in the form of mangroves4, palms, bamboo, reeds, hardwoods, and other grasses (Figure 4). The moisture allows for healthy fertile soil rich of organic matter and clay.

Settlement Southern Thailand because of its location is an agrarian and fishing-oriented society. While fewer people settle with the mountains, a majority of people live within the lowlands, rivers, and coasts of the region with Songkhla and Hat Yai being the most populous cities in all of Southern Thailand. The islands of Samui and Phuket are fishing resorts whereas inland5 , there are farms spread across the land. Today, there are many cultures and religions that cultivate the region. In addition to the already mentioned Buddhist and Muslim cultures, there is also a sizable Chinese and Indonesian population as well.

The Pak Tai Home

The Stilt House

Like its name implies, the stilt house is a building typology in which the main living space is elevated off the ground. However, unlike a solid western foundation, the underside of the stilt home is flexible space depending on the weather. Because of Thailand’s proximity to the water, marshy wetlands, and abundant forests the stilt home was popularized because it could protect the user from seasonal monsoons and the wild creatures that lived in the

4 Posayanonda.

5 Boonjub, “Study of Thai Traditional Architecture.”

6

rainforests at night.6 The readily available materials of bamboos and grasses made the stilt home inexpensive, fast to build, and transportable because it could be disassembled and brought from location to location across the Thai floodplain.

The earliest roof form used on the stilt house was the gable roof because its triangular form diverted rainwater from the house, its eaves created shade, and heat could exit through the ridge of the roof. In northern Thailand the gable roof follows a steeper pitch than the south because of its exposure to snow in the mountains, whereas the south receives more rain, but needs a gentler slope to reduce lateral loads from the wind and protect from a more overhead exposure from the sun (Figure 9). When building the home, the user would orient it to the east or west to allow for ease of access to the water for transportation to trade or sell their goods. While at home, the user would spend most of their time on the terrace, a large exposed area on the house platform for eating, relaxing, prayer, and sometimes sleeping at night. 7 During cooler nights, they would sleep inside the small enclosure on the terrace.

Differences from Central Thailand

While the stilt house of the south is fundamentally the same as the stilt house of the north, there are some difference that the Pak Tai took to adjust it for the appropriate climate. Because of the additional rainfall and a lower elevation, the stilt posts are longer creating a higher underside space, however, to prevent the wood from rotting, the use of teen sao or

7 Nanta.

7

6 Nanta, “Social Change and the Thai House.”

footings help strengthen the foundation from water and termites (Figure 5).8 In addition, on the very wet islands of Phuket and Samui, a large exposed terrace is not desirable so the terrace is reduced or almost not existent and the veranda’s roof covering is expanded to enclose or protect the home. Walls also may be battered to increase runoff. Religion also plays a significant role towards the uniqueness of the Pak Tai stilt house in regard to its arrangement and detailing, but will be discussed in another section.

Hierarchy among Housing

Ruen Krueng Pook

The first variant of the stilt house is the Ruen Krueng Pook (Pook) or the “tied bamboo home.” As its name implies, the Pook uses bamboo, a fast growing and inexpensive material as the core structural and cladding material (Figure 6). As the original vernacular house of southeast Asia, it was built for the purpose of being transportable as people moved across the region. With readily available materials, it was fast to assemble and could be built prefab so anyone could construct it in a matter of days. Today this home is seen as the less affluent form of the stilt home, thus is more common in migratory locations like fishing villages or a home for young couples.9

8 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

9 Boonjub, “Study of Thai Traditional Architecture.”

8

Construction

Because the Pook is designed as a “starter home” it is constructed using simple building techniques, accessible materials, and can be built quickly and inexpensively. As wood is a more expensive and difficult material to use, it is only utilized for the flooring and the main structural posts of the house the rest of the house uses bamboo, vines, leaves, and thatch which can be harvested and transformed into rope, roof coverings, wall panels and bonding agents.10 However, as vernacular building traditions are being replaced for more western approaches, the traditional building knowledge requires the expertise of masters who create prefab components for the user.

Materiality

With southern Thailand’s rich rainforests, the Pook was able to be constructed using a diverse palette of native and easy to harvest materials. The structural posts are made from hardwoods including a variety of palms and mangroves. These large and tall trees allow for a strong foundation against the harsh winds and rain. The roof material of a Pook is commonly thatch, however, more recently may be substituted for corrugated panels. The walls and binding material however are made from split bamboo, nipa palm, and vines. By weaving together the bamboo and using palm fibers, panels are made in a modular form that provide ventilation and protection from the rain. In some regions like in Yala, people may weave designs into the bamboo panels for an inexpensive form of ornamentation.

9

10 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

Ruen Krueng Sab

As peoples’ lifestyle shifted from migration to a more permanent and agrarian lifestyle, the need for an inexpensive portable home diminished for a more stationary and permanent structure. Because people didn’t need to move as much as before, a house could use better materials and they could spend more on something they could treasure. This evolution of the Pook was called the Ruen Krueng Sab (Sab) or the hardwood home, the most common dwelling typology in Thailand today.

Construction

Unlike the Ruen Krueng Pook, the Sab uses more costly materials that involve the intervention of more people to construct. The process to build a sab could take weeks or months, rather than the Pook’s days. This is because not only does the Sab use a lot more hardwood, but each board needs to be cut, and many are carved with intricate patterns or fretwork as a symbol of the owner’s social status. While, the arrangement of spaces and the overall form are similar, the scale of a Sab is larger and may even include an enclosed kitc hen, a washroom, and an additional dwelling unit.11 Construction traditions vary by religion thus are discussed in a later section.

Materiality

By using hardwoods, the Ruen Krueng Sab is a more complex structure because the walls, floors, and supports are made from wood (Figure 7). Unlike the Pook however, the Sab introduces terracotta as a cladding material. First introduced from China to Nakhon Si

11 Nanta, “Social Change and the Thai House.”

10

Thammarat in the 1800s, a special form of terracotta tile was created to adapt to the stilt house structure by creating a hook that would attach to the beams of the roof.12 Rather than relying on a tying technique, the Sab took advantage of mortice and tendon construction because the wooden logs could interlock akin to log cabin construction in North America.

Spaces in the Home

If there is one aspect that is inseparable from domestic architecture, it is the importance of the family. With the stilt home, the accessibility to future expansion is possible because of its origins as a modular and phase-oriented design. As the daughter gets married, the parents will build a separate unit for her by either converting part of the existing terrace or building onto the platform more.13

The Exterior

While the main platform provides the core living space of the stilt home, the underside and the perimeter is still widely utilized. Historically, every family had a subsidence or medicinal garden surrounding the house, but the underside varied by season. 14 During monsoon season, the ground is undesirable, thus it only useful enough to dock a boat in case it floods, but during the dry season it can serve as a leisure space, a storage space, or a bathing area. It is cool and ventilated allowing for an ideal relaxation spot during a hot day instead of the platform terrace.

12 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

13 Nanta, “Social Change and the Thai House.”

14 Boonjub, “Study of Thai Traditional Architecture.”

11

Traditional Spaces

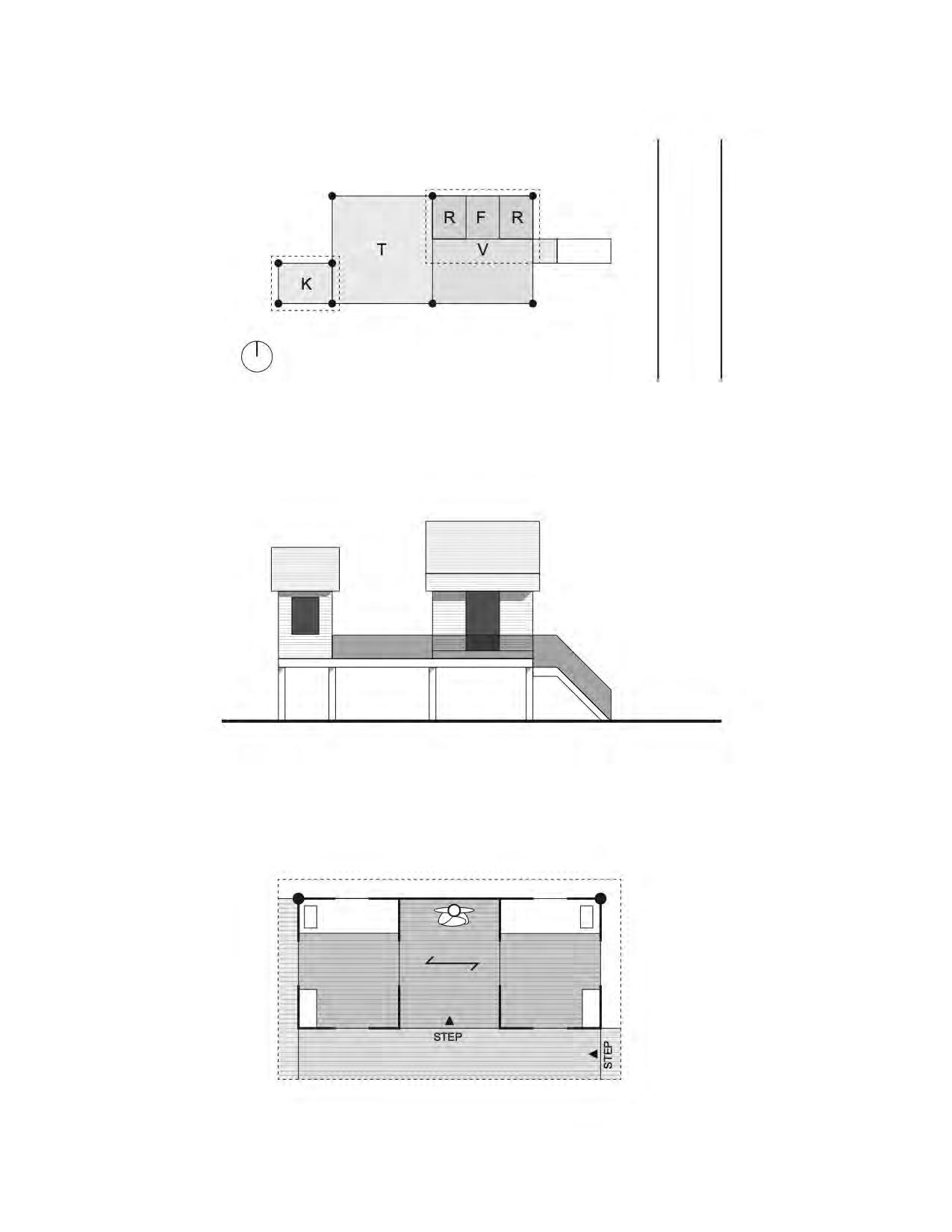

In a traditional Thai stilt house, the platform consists of the following sequence, the stairway to a veranda, sleeping quarters, and a rear terrace with a kitchen there is no plumbing thus there is no washroom (Figure 8).

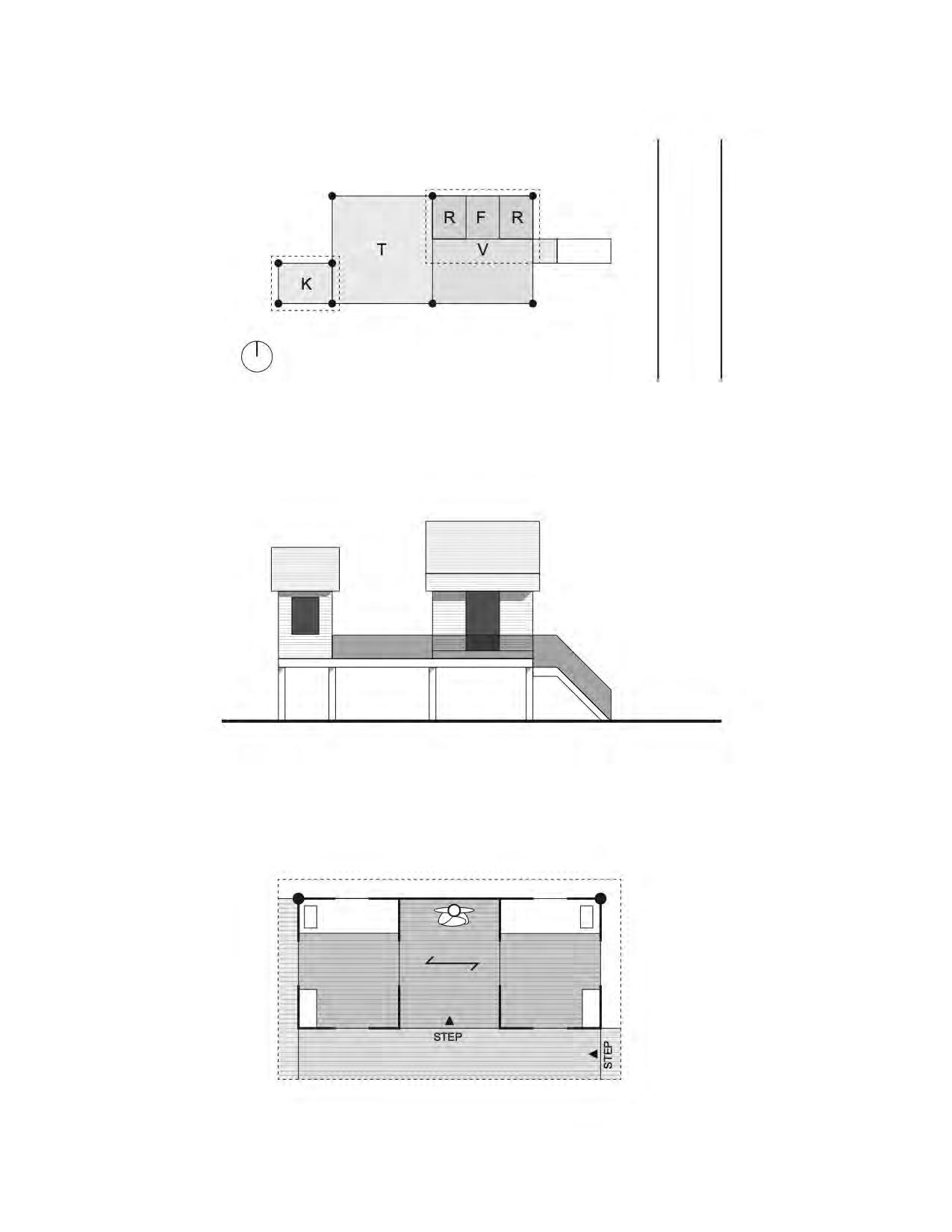

When entering a more traditional Thai home, spaces are organized hierarchically by levels. While building a second story (unless you think of it as a third) is usually not constructed, each room is separated by a step (Figure 10). These breaks in the platform level create a hierarchy of the sacred to the profane. However, due to accessibility to elders more home are now having level platforms.

In the house, the largest space is the terrace, an exposed balcony in the rear where most of the time is spent for eating, playing, welcoming guests and performing rites of passage. Some houses may have an opening for a tree to grow to cover the balcony for shade. Because the terrace is used the most and is exposed to the elements, it is most vulnerable to deterioration thus some people may redesign the terrace to be covered to protect the wood.15 However, covering the terrace can create spatial issues of poor ventilation and sun exposure.

Before entering the sleeping quarters, most homes have a veranda and a foyer, an open hall that acts as a covered small terrace. However, unlike the terrace, this space is considered more sacred because it can be the location for the guests to stay as well as the shrine for the Buddha. To enter the veranda, you must step up from the terrace.

15 Nanta, “Social Change and the Thai House.”

12

The sleeping quarters are the most sacred of spaces because it is not only where the family sleeps, but it also is the place where the family keeps their most respected treasures and good dishware. In a typical family, the daughter sleeps under the same roof as the parents and the son is given a separate building to sleep in. When the daughter gets married, an addition is built for her and her husband 16

Located in the rear of the house just off the terrace is the kitchen. Before the introduction of plumbing, the kitchen consisted of an outdoor kitchen, a covered space where the odors could be vented out. This was the location where a typical meal was created whereas the interior kitchen mostly consisted of the family hearth, where light cooking was done, or food would be stored. To prevent odors inside, some wooden wall panels are substituted for breathable bamboo panels and a washing station consists of spaced bamboo planks to let the water fall to the ground.

The furniture inside a typical stilt house is very minimal because traditionally the family would spend most of their time away from the home because they were working the farm or going out to the town to sell their fish. However, there are a few pieces that a family would typically have including a cupboard for plates when a guest comes, a clothing chest, the family hearth, and most importantly a shrine of the Buddha. Wealthier families may have a table and chairs, furniture that were introduced by the Chinese.

13

16 Nanta.

Modernization

Since the introduction of electricity, plumbing, and cars the changes to the stilt home can vary from minor to drastic. In the rear of the house near the kitchen, many families have hooked up plumbing to allow for a western washroom and an improved kitchen to wash dishes, bathe, and cool off.17 However, due to the bathroom being wood or bamboo, the users have to clean it often to prevent mildew growth and practice good ventilation. Installing a washroom can be costly because the floor needs to be able to support all the modern fixtures.

One of the more significant changes to the Thai stilt house is the conversion of the terrace in an open hall. Typically, the family may do this because they want to preserve the terrace floor from additional weathering, however this also turns what was an outdoor oriented lifestyle into an interior focused one. This can be difficult to achieve depending on the terrace size because a large sprawling terrace with lots of sun and good ventilation becomes a dark, dreary, and congested space.18 In this space, rather than building additional rooms, the family uses furniture as a way to demarcate space into a dining room, a den, an office, and children’s bedrooms (Figure 12). By grouping all these spaces into one great space, a sense of hierarchy is lost because rather than being divided by a step in the floor platform, every space is equal.

If the terrace is converted into an open hall, a new covered balcony may be allocated to serve as a remedy to the lost outdoor lifestyle. These spaces can serve the same traditional uses of the terrace as a dining or leisure space as well as inviting guests over (Figure 13)

14

17 Nanta. 18 Nanta.

Lastly, the underside of the house may be converted to a carport or can built into additional rooms, however this can create a problem in flood prone areas as it is losing the benefits of being a “stilt house.”

Religious Differences

One of the major differences that defines the southern Thai stilt house from the central or northern Thai stilt house is the religious diversity of the region. Whereas the north has remained a relatively stable Thai Buddhist region, the spread of Indonesian, Malaysian, Chinese, and Dutch culture has transformed the stilt house into something more complex. As the dominant religions in the region, the following section will discuss the differences between Thai Buddhist homes and Thai Muslim homes.

Thai Buddhist Homes

Of the fourteen provinces in southern Thailand, Buddhism is prevalent in the northern ten. Historically, the reasoning for this is the ruling of the Thai kingdoms and their dominance across the peninsula. While similar to the stilt house of central Thailand, the southern Thai Buddhist house takes inspiration from Chinese motifs and even some Malaysian Islam in the form of how they ornament their homes.

In Thai culture, the way a roof is ornamented, is a symbol of wealth. With the spread of Malay culture, the hipped roof was introduced as an alternative to the gable roof. These are typically decorated with Chinese or vegetal roof finials (Figure 14). If a gable is used, the ends

15

are decorated in a variety of patterns including the rasmi (sunburst pattern)19 and may use stucco rather than wood. The roof is clad in the terracotta the Chinese introduced to the region.

The interiors may be brilliantly painted in vivid colors with carved fretwork on the ventilation panels above the doors and windows (Figure 17). Ceilings and structural posts may be carved with Chinese motifs as well. The terrace in some homes may be inspired by Chinese courtyard homes with a tree located in the center for shade during the daytime. The Thai Buddhist home acts as a blend of Chinese and Malaysian design traditions.

Thai Muslim Homes

In contrast to the Thai Buddhist home, the Muslim counterpart contains more drastic changes to the Thai stilt home because of the religious practices that came from Malaysia and Arab traders from the west. In southern Thailand, this style of home is more prevalent in the provinces of Satun, Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat because their former Malaysian rule. These homes tend to be larger than their Buddhist counterparts and take a lot of inspiration from Islamic standards from Arabia and India.

While the family culture is slightly similar, Muslim families tend to be larger thus there are more units built around the central terrace to the point that the terrace could be fully enclosed. One of the major differences between the Buddhist and Muslim homes is that rather than having one family kitchen, in a Muslim household each family has their own kitchen. The washroom in the house is located in the rear as the most profane space and a ritual washing

19 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

16

station is located in the front before descending into the home Some wealthier homes may have a ritual well in the center of the home. A Muslim Thai home may also include a mashribiya balcony that is intricately carved rather than the open Buddhist balcony.

One of the most influential effects of Muslim influence to Thailand is the way it changed the stilt house roof by introducing the hipped and Manila roof styles, a hybrid gable hipped roof. The hipped roof in southern Thailand is referred to as the “lima” roof which means five in Arabic, a sacred number noting the five pillars of Islamic practice as well as the five calls to prayer per day.20 The ridges along the lima roof are decorated with ornate finials depicting a variety of vegetal or floral patterns the human figure is never depicted unlike Buddhist carvings. In addition to the finials, many Muslim hipped roofs have delicately carved soffits below the eaves. The other roof style introduce is the Manila roof which is also referred to as the “blanor” style meaning Dutch21 who introduced the style to the region. As the most complex roof form, the blanor style is a symbol of higher class because of its ornamented gables of carved wood or stucco in addition to the roof finials and soffits.

While Buddhist homes are expertly crafted with beautiful fretwork and painted with Chinese imagery, ornamentation is one of the most recognizable aspects in a Muslim home, thus in a Thai Muslim home, it is expertly decorated with the beautiful Islamic motifs of geometric patterns, floral and vegetal designs, and calligraphic scripture In Narathiwat as a type of “southern folk art” the bamboo panels of the Ruen Krueng Pook may be woven in a

20 Posayanonda.

21 Boonjub, “Study of Thai Traditional Architecture.”

17

pattern of stars, diamonds or herringbone transforming a rather simple architectural style into a very beautiful one (

Figure 18).

Unlike Buddhism, another significant difference in the Muslim home is the process of construction. Some aspects transfer from Buddhism including the idea of “Kwang tawan” in which the home can only face east or west, otherwise misfortunate and danger will come. The interior of the home is oriented to face Mecca in the west. When building the home, timing is very important in Islam because on some days like Friday, construction is not permitted. On the day the house begins construction, all the posts must be erected the center back post or Sao Ek is to have a coin attached to bring luck (Figure 19). During this day, a special meal called

18

Poo Lod Kun Yid consisting of stick saffron rice is made for the workers and the guests.22 When time comes to move in, it is usually good luck to move in during Ramadan or Muwlid, the month of Muhamad’s birth.

Future Concerns

Decline of Thai Vernacular

When the Thai stilt house was popularized, society was an agrarian manual labor society in which many people worked the fields producing food for their families and selling them to the cities. However, as technology advanced, innovations in farming technique reduced the demand for farmers because crops could be harvested faster and in higher quantity than by hand. While some farmers adapted to this new technology, others were pushed away from the industry and turned to the city centers for a new job.23 In these city centers which were more modernized, the need for a stilt house is low and is replaced by the western apartment block instead.

From an artisanal perspective, the transition away from the vernacular tradition is saddening because of the loss of construction knowledge. A traditional Thai home requires the knowledge of indigenous building techniques, so people are looking towards “simpler”

western construction techniques and materials. Wood as a material is becoming increasingly expensive and being replaced with concrete, brick, and corrugated metal. Deforestation is an

22 Posayanonda, “The Thai House.”

23 Nanta, “Social Change and the Thai House.”

19

issue because rather than . The transition to western architecture i ornately crafted wooden home is replace with a prefabricated concrete effect of climate change as it endanger the region is shifting. increasing the air temperature of the region. With less rainfall, drought is more common in rural communities

( Figure 20). Yet, with less trees there is less ground coverage leading to mudslides and desertification. With higher temperatures, the sea levels are rising, permanently flooding otherwise stable fishing communities. Farmers and fisherman are fleeing their industry for the

20

24 Marks, “Climate Change and Thailand.”

cities as climate refugees because their business is no longer sustainable. To stop the spread of climate change requires great change to prevent the endangerment of vernacular cultures and settlements around the world.

Conclusion

The stilt home today is on the most recognizable vernacular typologies of architecture because of its simple form, effective response to the environment, and its adaptation to many cultures and religions. In southern Thailand because of its rich ethnic diversity and its ideal geographic location, the stilt home became a powerful building language in the region With influence from across all of southeast Asia, religions that were spread, and the intervention of the European colonists, the stilt home adapted to all these influences into a complex blend of cultures not found as strongly to the north. Looking back to the past and what we can see in the future, it is important that architects study vernacular building typologies because they were able to not only optimize performance, but also successful created a tangible sense of cultural identity that is rarely found today. Architecture that may seem simple or traditional in form, may be one of the most powerful lessons we can learn from.

21

Appendix A

22

Figures Figure 1: Map of Southeast Asia .................................................................................................. 4 Figure 2: Religions of the Pak Tai People ..................................................................................... 4 Figure 3: 8th Century Borobudur Bas Relief............................................................................... 22 Figure 4: Lush Coasts of Phuket ................................................................................................. 22 Figure 5: Southern Thai House Differences ................................................................................ 23 Figure 6: Ruen Krueng Pook ...................................................................................................... 23 Figure 7: Ruen Krueng Sab ........................................................................................................ 23 Figure 8: Spatial Organization of the Stilt House ....................................................................... 24 Figure 9: Environmental Response Axon ................................................................................... 25 Figure 10: Spatial Hierarchy in the Veranda ............................................................................... 26 Figure 11: Underside as Living Space 26 Figure 12: Traditional vs Contemporary Home .......................................................................... 27 Figure 13: Covered Balcony ....................................................................................................... 27 Figure 14: Thai Gable Ornamentation 28 Figure 15: Muslim Ritual Well ..................................................................................................... 29 Figure 16: Pak Tai Roof Types 29 Figure 17: Muslim Ventilation Fretwork 30 Figure 18: Muslim Ruen Krueng Pook 30 Figure 19: Muslim Stilt House Construction 31 Figure 20: Climate Change in Thailand 32

23

Figure : 8th Century Borobudur Bas Relief

Figure 4: Lush Coasts of Phuket

24

Figure 6: Ruen Krueng Pook

Figure 7: Ruen Krueng Sab

26

27

Figure 10: Spatial Hierarchy in the Veranda

Figure 11: Underside as Living Space

28

Figure 12: Traditional vs Contemporary Home

29

Figure 14: Thai Gable Ornamentation

30

31

Figure 17: Muslim Ventilation Fretwork

Figure 18: Muslim Ruen Krueng Pook

32

Figure 19: Muslim Stilt House Construction

33

Bibliography

Works Cited

Boonjub, Wattana. “The Study of Thai Traditional Architecture as a Resource for Contmeporary Building Design in Thailand.” Silpakorn University, 2009. https://docplayer.net/10722566-The-study-of-thaitraditional-architecture-as-a-resource-for-contemporary-building-design-in-thailand-by-wattanaboonjub.html.

Marks, Danny. “Climate Change and Thailand: Impact and Response.” CONTEMPORARY SOUTHEAST

ASIA 33, no. 2 (2011): 229. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs33-2d

Nanta, Piyarat. “Social Change and the Thai House: A Study of Transformation in the Traditional Dwelling of Central Thailand.” University of Michigan, 2009.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/30864426_Social_Change_and_the_Thai_House_A_Stud y_of_Transformation_in_the_Traditional_Dwelling_of_Central_Thailand.

Posayanonda, Saowalak. “The South.” In The Thai House: History and Evolution, by Ruethai Chaichongrak, 190–234. Trumbull, CT: River Books, 2002.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003862834

Timsuksai, Pijika, and A. Terry Rambo. “The Influence of Culture on Agroecosystem Structure: A Comparison of the Spatial Patterns of Homegardens of Different Ethnic Groups in Thailand and Vietnam.” PLOS ONE 11, no. 1 (January 11, 2016): e0146118.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146118

Works Consulted

“Average Weather in Songkhla, Thailand, Year Round - Weather Spark.” Accessed August 18, 2020.

https://weatherspark.com/y/113364/Average-Weather-in-Songkhla-Thailand-Year-Round Bin Hassan, Muhammad Haniff. “Explaining Islam’s Special Position and the Politic of Islam in Malaysia.”

Muslim World 97, no. 2 (April 2007): 287–316, 30. Hays, Jeffrey. “ELEMENTS AND PARTS OF THAI ARCHITECTURE | Facts and Details.” Accessed August 18, 2020. http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Thailand/sub5_8e/entry-3258.html.

“PALACES AND ROYAL AND ARISTOCRATIC RESIDENCES IN THAILAND | Facts and Details.”

Accessed August 17, 2020. http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Thailand/sub5_8e/entry3259.html

Kusalasaya, Karuna. “Buddhism in Thailand,” n.d., 17.

Richard Kuehn, Paul. “Thailand Village Life.” Blog. WanderWisdom. Accessed August 18, 2020.

https://wanderwisdom.com/travel-destinations/Living-in-Thailand-Life-in-a-Thai-Village

Ruohomaki, Olli-Pekka. “Livelihoods and Environment in Southern Thai Maritime Villages.” Phd, SOAS University of London, 1997. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/28505/.

Sthapitanond, Nithi, and Brian Mertens. Architecture of Thailand: A Guide to Tradition and Contemporary Forms. Editions Didier Millet, 2012.

“Traditional Houses - Thailand.” Accessed August 18, 2020. http://www.pattaya-location-beachfront.com/anmaison.php

Valerie. “‘The Thai House: History & Evolution’ Vocabulary.” Thinking Thai (blog), December 16, 2008. http://thinkingthai.blogspot.com/2008/12/thai-house-history-evolution-vocabulary.html

Weerataweemat, Songyot, Nopadon Thungsakul, and Vira Anolac. “Phutai Vernacular Houses in Maung Phin, Savannakhet, Lao PDR.” Journal of Mekong Societies 3, no. 2 (2007): 61–89.

34