ONCE THERE WERE DIKES ONCE THERE WERE DIKES

Krijn Nugter 2024

Krijn Nugter 2024

Krijn Nugter

krijnnugter@gmail.com

Master Landscape Architecture

Academy of Architecture

Amsterdam University of the Arts

March 2024

Committee

Lodewijk van Nieuwenhuijze (mentor)

Bruno Doedens

Alexander Sverdlov

Examination committee

Kim Kool

Roel van Gerwen

Head of Landscape Architecture

Hanneke Kijne ≤ 2022

Joost Emmerik 2022 ≥

All images are own work unless the source is mentioned. They may not be shared or published by any person or entity without permission from the author.

ONCE THERE WERE DIKES

A study of how Māori philosophy can be an inspiration for climate adaptation strategies

“Once there were dikes” is a Dutch graduation project for the study Landscape Architecture that was compiled out of a curiosity in other cultures, questions why people act in certain ways, and a drive to challenge assumptions.

In this project, an attempt was made to approach the perspective on the landscape from a non-Western mindset and translated into landscaperelated issues. To accomplish this, the Māori culture was studied, and a specific area in New Zealand was used to illustrate this perspective.

Throughout the project, it became evident that the meaning of the landscape for Māori is complex and intrinsically linked to Māori identity. There was a

noticeable reservation from Māori towards me, which is a legacy of the colonial past and its impact on the landscape and Māori culture.

Nevertheless, this project continued, and statements are made about what the Māori culture and the significance of the landscape is. Additionally, land was used which the Ngāti Maru iwi have a deep connection to. Finally, suggestions were made about how this land should be further developed.

It has never been the intention to offend anyone with this project. I am aware that this project is incomplete in its understanding of the meaning of landscape and Māori culture. I also acknowledge that taking advantage of valuable or

sacred land for a studyproject can come across as disrespectful. Furthermore, I understand that it is not up to me to determine how this land should look like in the future.

Yet I think landscape architects can play a crucial role in multidisciplinary issues regarding landscapes. This project was an exercise; an attemption to combine indigenous knowledge with modern science in order to obtain a graduation. At the same time, I sincerely hope that this project contributes constructively to the discussion about future land use and land ownership, specifically in the Kopu Area.

Krijn March 2024

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

A cultivated landscape as nature reserve.

An example of how nature benefits from more space for the river.

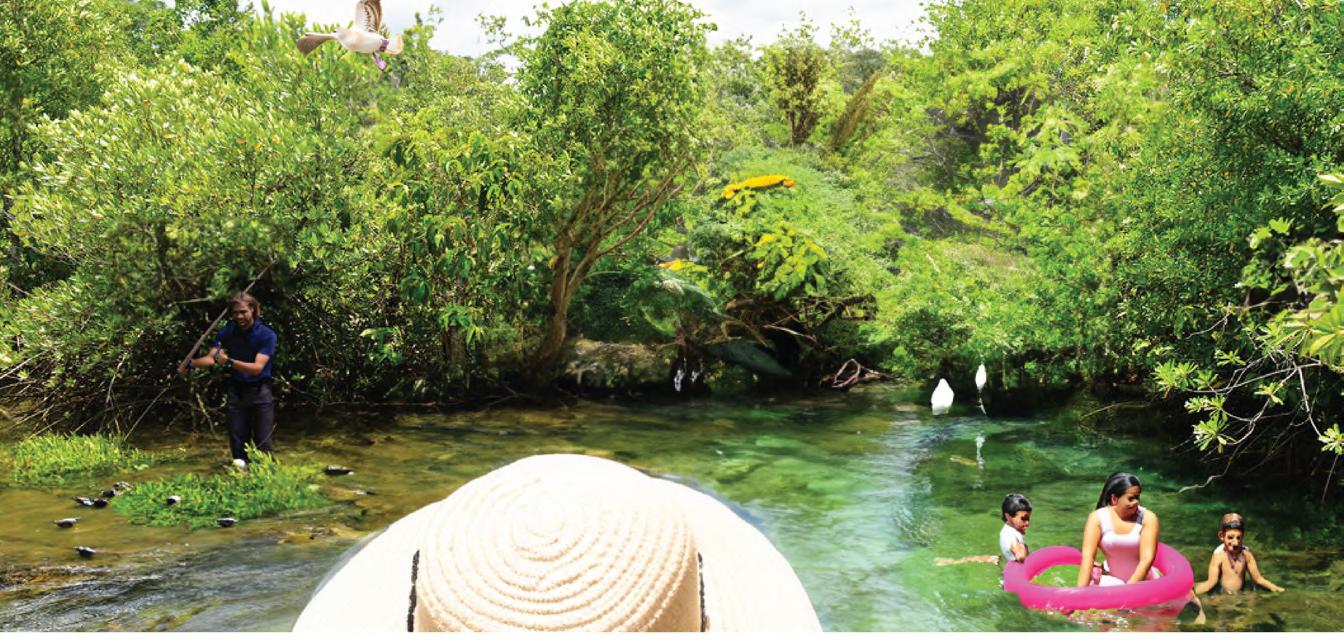

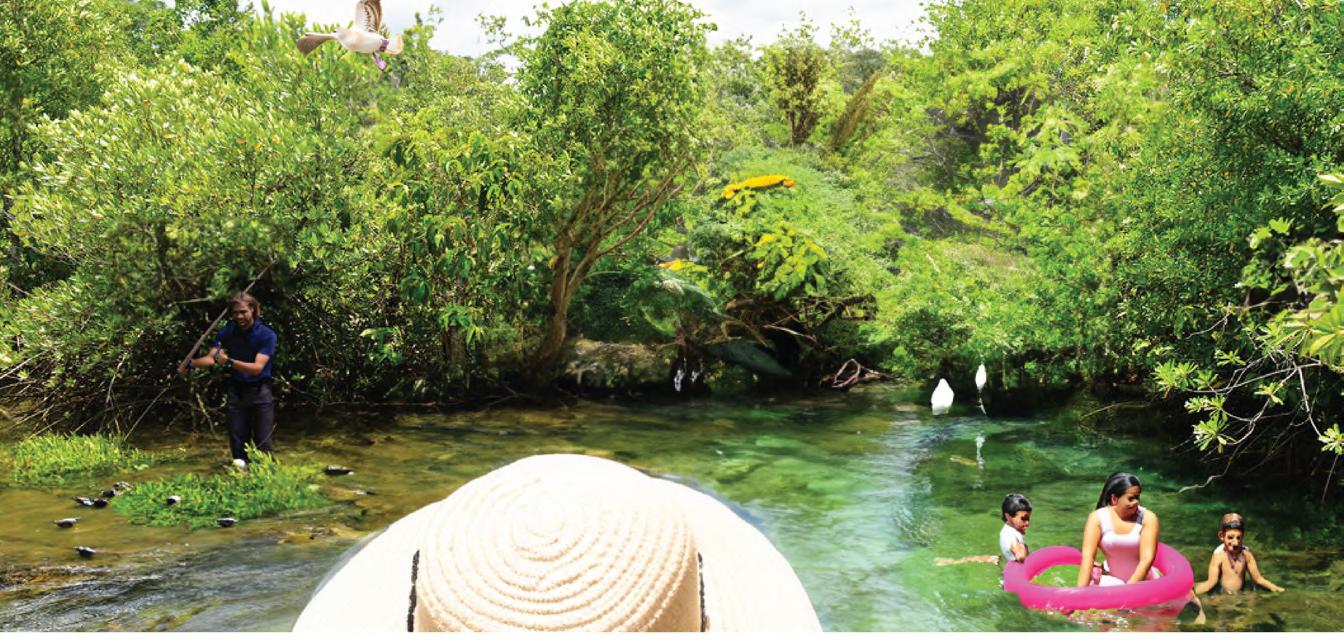

A river as essential part of the well-being of Māori tribes.

Vinkeveense plassen

De Blauwe Kamer

Whanganui River

Prologue

Landscape architects design landscapes with ‘nature’ as being an essential component to do so. However, what is the meaning of nature exactly? How can nature be interpreted? And how do people relate to that nature, or how should they relate, in the context of climate change?

“ The time has now come for the same care to extend to nature itself, to find means to achieve the preservation of important natural-historical landscapes,” writes nature enthusiast Jac. P. Thijsse in his article ‘De Olievlek’ (The Oil Stain), published on November 26, 1904, in Algemeen Handelsblad (Our Heritage, 2005).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, partly due to Jac. P. Thijsse, one of the founders of nature conservation in the Netherlands, highly cultivated landscapes were identified as valuable natural areas and protected against rapidly growing villages and cities that threatened Dutch natural

beauty like an ‘expanding oil stain’. The value of nature was articulated for the first time in Dutch history.

In the 70s and 80s, the idea of not only protecting designated nature reserves but also creating more space for ‘wild’ nature gained traction. Instead of making Dutch lands mostly suitable for agriculture, except for nature reserves, more space was allocated for nature development, the natural system, and room for the river. With Plan Ooievaar as vision for the Dutch river area, the new ‘landscape system thinking’ was introduced and increasingly used as a basis for spatial planning in the following years.

In 2024, it is legally determined that natural systems - water and soil driven - are guiding principles for the future design of the Dutch landscape to make it more resilient as a delta region against a changing climate. Through this new thinking, space for the natural system

will also be allocated ‘beyond the riverbanks.’ The search for a symbiotic coexistence with nature is now underway, and although this has always been necessary in a Netherlands predating the invention of the dike, the mentality has completely shifted in recent centuries to a society where nature became subordinate to humans.

However, indigenous cultures such as the Māori culture see humans as an integral part of nature. Words like ‘ I am the river, and the river is me’ are expressions of the Whanganui tribes in New Zealand, referring to the Whanganui River, which was granted legal personhood in 2017, recognizing it as a living entity equal to humans.

In this graduation project, I aim to comprehend and apply this holistic worldview in a spatial assignment, with the goal of providing insights into how this way of thinking can be integrated into the future design of (Dutch) delta landscapes.

Abstract

Climate change challenges us to consider landscape adaptation strategies. For delta regions like the Netherlands, sea level rise poses a challenge, while the country has historically been protected from water threats through technological innovations. The latest climate predictions from the IPCC indicate that in the longer term (2300), sea levels could rise by 17 meters. This places technological innovations in a different context than the usual predictions focusing on 2100. Indigenous knowledge can provide insights into how collaboration can be sought with natural dynamics, rather than seeing them as a threat. This research explores how Māori philosophy can be an inspiration for new types of adaptation strategies. To test this, an agricultural polder area in New Zealand has been used as a case study, and is transformed into a landscape that is mostly shaped by nature with the use of natural dynamics.

The project has been both qualitatively as quantitatively

researched. Unlike typical landscape architectural projects, this project area was initially studied through anthropological fieldwork. Various interviews with (local) Māori, scientists, rangers, or officials determined the significance and value of the area. It is noticeable that there is societal tension over land use and ownership that comes from the colonial history. Additionally, the project area was examined through literature, map studies, and archeological findings to understand how the landscape and ecosystems functioned from a scientific perspective and how large-scale interventions in the landscape have caused these natural dynamics to disappear.

Inspired by Māori philosophy, three guiding principles have been formulated concerning the functioning of the natural system, the carrying capacity of the landscape, and the cultural-historical value of the landscape. From there, an adaptive planning strategy has been developed, which guides the transformation of the project

area, emphasizing collaboration with natural dynamics and a restraint from human interventions. This results in a cyclical planning process where planning uncertainties are part of the strategy; after each human intervention, nature shapes the area further, and before the next step is taken, the situation at that moment must be reconsidered. The plan therefore has no fixed final image. Not only the natural dynamics are reintroduced, but also culturally and historically valuable Māori sites.

This project illustrates how an agricultural area can transform into a ‘Māori landscape’. The outcomes is a restart of the natural process of reclamation in this area and thus the ability to adapt to sea level rise. Natural vegetation processes and the original landscape slowly return, along with Māori culture and values.

Introduction - Motive - Māori - Location - Assignment

Content

Pre human era Māori era European era Today Strategy Design Perspective Epilogue 14 32 44 54 60 64 72 132 138

Remote places

Remote places

Photo taken from the airplain to New Zealand

Photo taken from the airplain to New Zealand

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION

Climate change

Ecomodernism

Antropocentrism 2.0

16

Motive

In the sixth IPCC report of 2023, alarming predictions regarding climate change are presented. The insights into sea level rise are crucial for all delta regions inhabited by 500 million people worldwide, including the Netherlands, which already lies for 60% below sea level. While current strategies may adequately protect the Netherlands in the short-term predictions until 2100, with a sea level rise of 1 or 2 meters, it cannot be excluded that by 2300, sea levels may have risen up to 17 meters, necessitating a reconsideration of existing strategies.

Although this worst-case scenario has a low probability, it represents a fundamental threat that requires proactive adaptation strategies that cannot be deferred to the next generation.

These strategies can build upon the tradition of technological advancement, a pragmatic approach to addressing urgent climate issues without sacrificing

human prosperity and economic progress, commonly referred to as ecomodernism.

On the flip side, the same technological progress can be viewed as the contributor to the initial causes of the climate crisis and the crossing of planetary boundaries. Acknowledging and taking responsibility for this is termed as anthropocentrism 2.0. Instead of pursuing growth, society should consider a prosperous contraction by repairing, restoring, or defragmenting the earth.

A different mindset could help to achieve this contraction, emphasizing the understanding that humans are part of a larger whole, and that achieving a proper balance between humanity and nature is crucial for survival.

Indigenous cultures, such as Māori have lived with a similar worldview for thousands of years and that is the reseaon to understand this mode of thinking firstly, before ‘using’ it in adaptation strategies.

17

Māori

The Māori people are the indigenous Polynesian inhabitants of mainland New Zealand, also known as Aotearoa. The sentence “ I am the river and the river is me” has gained international attention. It symbolizes a profound connection between humanity and nature. According to Māori philosophy, nature is seen as a community, something in which humans actively participate, a sort of family. Rivers, among other landscape elements, are considered ancestral to Māori,

fostering an ongoing and active relationship. Following the reciprocal principle of not only taking but also giving, the well-being of a river is maintained, ensuring the well-being of the people living alongside it. This circular thinking leads to the establishment of a sustainable society that can last for ages.

In order to internalize this worldview and to use it in a spatial assignment, a sociocultural research is needed to get a better grip on it.

18

‘‘I was bourn up in a world with the older people. In a time of no electricity. That’s not so long ago really. You know, the 50s and the 60s. The place was still quite alone. Particularly up the river where we had no other contact with many people. I’m being able to be brought up and thaught by our elders. The river is the biggest player in my who I am. Without the river I am nobody. And it is because the way that I feel the spiritual connection with the river, I feel that it is my job to ensure that I have been giving my hand on to others.

When my river is well, my people are well and so is our Mauri, our lifeforce is well. The river flows from the river to the sea, I am the river and the river is me.’’ (Ned Tapa, 2DOC, Wij zijn de rivier, 2020)

19

20

Kaumātua Wati Ngamane (Cowpland, 2022)

Research methodology

Various research methods have been used to gain a better understanding of Māori philosophy. Firstly, literature describes how the origin story of the Earth differs fundamentally from the scientific narrative. Māori reasoning from Mother Earth, where all elements of nature and the landscape, including humans, are created equally and are proportionally intertwined. In this context, human existence is interwoven with nature across multiple dimensions.

Secondly, the geographical location of inhabitable areas is crucial to Māori identity. Natural features such as rivers are viewed as ancestors, akin to family members, and over centuries, specific traditions and cultural practices have evolved within each tribe,

linked to particular locations in the landscape. Knowledge about using natural resources, interactions regarding natural dynamics, or traditions around ‘spiritually’ significant sites are orally shared from generation to generation within Māori tribes.

Through anthropological fieldwork research, involving interviews with diverse Māori individuals, it has become evident that Māori are highly cautious in sharing local knowledge about the landscape or expressions related to nature. Due to the colonial past, significant areas of the original landscape have disappeared, along with many customs, rituals, or practices. There is a great desire to the original landscapes as they are crucial for identity, wellbeing and way of life.

21

Natural system

Interaction between soil, water and vegetation

Landscape capacity

Harvesting the amount that the ecosystems provides

Historic traces

Respecting the continuity in landscape history

22

Leading principles

From the socio-cultural preliminary research, I distill three guiding principles that serve as a translation of the Māori philosophy into a planning strategy. The first is the natural system, specifically focusing on the interaction between soil, water, and vegetation. The second is the carrying capacity of the landscape; the

concept that one should not exploit the landscape beyond its capacity, emphasizing harvesting what the ecosystem provides. The third principle is the respect for the continuity of landscape history, particularly taking into account culturally significant and/or sacred Māori sites in the landscape.

23

Location

The project area is near Kopu, a small settlement 5 kilometers south of the city of Thames. The location is situated next to the river mouth of the Waihou River, which flows from the Mamaku Ranges through the Hauraki Gulf. In its lower reaches, the river partially forms the alluvial Hauraki Plains. The river mouth of the Waihou River has a culturally rich history, inhabited by various Hauraki tribes and later by Europeans. Simultaneously, the area has been reclaimed and is situated below sea level, making it vulnerable to sea level rise. In that sense, it shares similarities with the Netherlands, making it an intresting case study area.

Plains

25

Hauraki

Farm

Within this agricultural area, one farm will serve as a case study in this project. The transformation occurring in this area will be exemplary for the entire low-lying delta region, in the Hauraki plains, or as inspiration for other delta regions worldwide . The area has been reclaimed from the sea and is partially

surrounded by dikes. Additionally, waterways have been dug out to keep the land dry. Consequently, approximately 90 percent of this farm consists of meadow, with its primary function being milk production. Simultaneously, there are twelve residences located on the edge of this project area.

27

29

Meadow

Dikes and canals

1 farm and 12 dwellings

30

The central question in this project is how this agricultural area can transform into a ‘Māori landscape’ using the guiding principles derived from Māori philosophy.

31

Assignment

Growing landscapes

Photo taken at Waiheke island

Growing landscapes

Photo taken at Waiheke island

PRE HUMAN ERA PRE HUMAN ERA

34

Water from land to sea

200.000 ha catchment area transporting sediments

Water from sea to land

Dynamic tidal zone

Estuary

The Hauraki Plains is an alluvial floodplain through which various rivers flow, including the Waihou River. In the deltaic region, the river mouth system influences the dynamics and growth of the landscape. This dynamic process involves water being conveyed from the mountains to the sea, carrying sediments along the way. At the same time, tidal dynamics also influence the coastline, with water from the sea flooding the land.

35

Sedimentation

Due to tidal dynamics, sediments are deposited over the land. Through daily repetition of this process the landsurface elevates. When the highest tide is not able to flood the land anymore, the area becomes marshland; water becomes land.

38

Landification

This process of elevation results in a regressive coastline; a coastline moving seaward. With an average retreat rate of 2.5 meters per year, it is evident that

the project area was situated directly along the coastline approximately 1000 years ago, whereas it now lies nearly 5 kilometers inland from the coastline.

39

Mangrove

In the semi-tropical climate of this region, mangrove processes are an integral part of the sedimentation process. The mangroves that grow here possess specific tap roots capable of better holding the

sediments. Thriving in the high tide, mangrove trees additionally serve to protect the hinterlands from storm surges. Simultaneously, mangrove forests provide habitat for various fish and bird species.

41

Kahikatea

Behind the mangroves, Kahikatea forests thrive. These forests emerge after the area has became land. They are swamp forests that flourish in extremely wet conditions, and the relatively elevated root system of the Kahikatea tree sustains the trees in the marshy soil. Due to their proximity to the coast, the

groundwater level is very high, yet these forests are resilient to saltwater intrusion during occasional storms and flooding events. Various plant species rely on Kahikatea trees, and in climax stage, the forests are highly layered in plant species, making them an intriguing habitat for numerous indigenous animal species.

43

Respected places

Respected places

Photo taken at Pukekiwiriki Pā in Auckland

Photo taken at Pukekiwiriki Pā in Auckland

MĀORI ERA

MĀORI ERA

Māori quoe

Occupation

It is said that around 1600, the initial settlements are build in this area, which currently fall under the jurisdiction of Ngāti Maru, an entity devised to collaborate with the Crown (European government). Ngāti Maru comprises 16 hapu (subtribes) residing in the broader Kopu region. Ngāti Maru are descendants of Te Ngako, also known as Te Ngakohua, the son of Marutūāhu, after whom the tribe is named. It is one of five tribes of the Marutūāhu confederation, the others being Ngāti Paoa, Ngāti Rongoū, Ngāti Tamaterā and Ngāti Whanaunga. The Marutūāhu tribes are descended from Marutūāhu, a son of Hotunui, who is said to have arrived in New Zealand on the Tainui canoe. The Marutūāhu tribes are therefore part of the Tainui group of tribes. The Marutūāhu confederation is also part of the Hauraki collective of tribes (Te Ara, 2023). All places where Māori have settled are connected to the past and can hold sacred value, whether explicitly recognized as such or not.

47

48

Occupation strategy

Based on the topography present at that time, Māori settled at the edge of water and land. These locations were strategically chosen to use natural resources from the sea as well as from the land. Māori constructed mounds in areas closely associated with the existing creek system. Over the years, these mounds were raised or expanded to remain dry or accommodate further growth of the tribes.

Settlement types

There were various types of settlements, depending on their purpose and occupants. A living site could serve as a fortress where the Māori chief resided, and where all subtribes could retreat in times of threat. This fortresses were surrounded by a defensive wall made of palisades. Other living sites were less fortified than the fortress but served as well as villages where sub-tribes lived in comunities. Further across the landscape, various residential areas were built, which, for example, served as temporary homes for seasonal hunting. >

49

50

51

The kainga of Te Kumi (Library, 2022)

Māori Pa site (Gallery, 2024)

Palisaded fence (Aucklandnz, 2024)

52

Values and practices

Over the centuries, Māori have accumulated knowledge to survive in the landscape. Various natural resources were used for different purposes. Because Māori did not have a written language, knowledge about the use of

these resources was passed on orally from generation to generation. An important lesson was respecting the carying capacity of the landscape, among other things to be able to survive on the longer term.

53

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

EUROPEAN ERA EUROPEAN ERA

56

Exploitation

After New Zealand was also discovered by Europeans in the 17th century, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, establishing it as a British colony. The treaty included agreements on, among other things, the distribution of land. To this day, there are disagreements over these agreements because there were two different versions

of the treaty: one in English and one in Māori language. As a result, many culturally significant areas of Māori land have disappeared. The land was exploited and transformed into dairy farming in this area. Consequently, the production of nutrients in the form of milk yields is only one-fourth as much as the same area would yield in its natural state.

57

58

Growth potential

As a result of deforestation, mangroves have disappeared, along with their function of protecting the land against

storm waves. Around 1930, a major storm occurred, prompting the decision to build dikes. Consequently, sediment

depositions also were blocked and thereby permanently diminished the landscape’s potential for growth.

59

The flood of all floods (Watton, 2006)

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Photo storm

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Photo storm

TODAY TODAY

62

Climate change

Presently, there are various predictions concerning the future sea level rise, categorized into different scenarios. These scenarios are depeneded upon other natural processes on earth and are stratified by confidence. In the most extreme scenario, with a low probability, it is forecasted that by 2300, the sea level could have risen by up to 17 meters. For the project area, this would mean that by 2090, the current dikes will not be sufficiently high, resulting in 99% of the area being flooded. This will effect the way living, infrastructure, production

and last but not least, Māori heritage.

In the context of climate change, New Zealand is already vulnerable to weather extremes, as evidenced by the damage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle at the time when fieldwork for this project was conducted. Uncertainty and fear that comes along during these events strengthen the determination to prepare well for such events.

Water flows

Photo taken in Coromandel ranges

Water flows

Photo taken in Coromandel ranges

STRATEGY

66

Adaptive planning

Based on the guiding principles, the history of the area, and the current climate predictions, the proposal is to transform this land to the original landscape in order to adapt to climate change. To reach that, the approach is twofold. Firstly, the occupation strategy originating from the Māori era is reintroduced. This entails reintroducing all inhabited areas of Māori origin with mounds and assigning them new significance. Additionally, this plan is founded on nature-based adaptation, whereby water and sedimentation processes are reintroduced within the project

area, allowing it to rise equally with the rising sea level. This can be seen as a next step in the design tradition of land reclamation.

This plan does not have a final blue-print, but is based on adaptive planning that utilizes the natural system. A cyclical planning process helps to manage planning uncertainties. Each subsequent step in time is taken after reflecting on the preceding period. Nature carries out the work at its own pace. Humans do no more than necessary and rely on nature. >

67

Design tradition

Restraint construction

Photo taken along Whanganui river

Restraint construction

Photo taken along Whanganui river

DESIGN DESIGN

Mounds

Based on archaeological excavations, the precise outlines of at least two former pa sites can be determined. To honor the value that these sites may hold, these outlines are

faithfully replicated and raised to a height just above the current dike height. This way, these sites are secured for a certain period of time and prepared for the worst case sea level rise prediction.

75

Extractions from The Waihou Journeys (Phillips, 2000)

76

Local materials

local natural materials are used as much as possible. Stones from the Kirikiri stream upstream are used to reinforce the mounds and protect them from erosion caused by the natural dynamics that enters the area in a later stage.

77

Marae

It can be said that Hurumoimoi was inhabited by a Māori chief and is therefore valued differently than other sites. It is customary to build a Marae on such sites; a Māori community’s hub where Māori retain their tribal history and stories, genealogy, customs, and traditions. A Marae consists at least of a meeting

house, a dining hall, a gate and a courtyard, following traditional architecture. In this proposal, a boardwalk is introduced, referencing the function of the fort, and follows the exact contours of the former palisaded defensive wall. This reinforces the division between inside and outside the fort.

79

Graveyard

In Whetekura, a graveyard has been found, signifying that this site holds a sacred status. The proposal suggests reintroducing the exact contours of this place with a small fence and a gate. Access to the site is facilitated by a gravel pathway.

81

82

Temporary dike

A temporary dike is constructed in anticipation of the phase when the area will be opened up to the water. This dike follows the high tidal contour line and is raised just enough to withstand storm floods. With its gentle slope, this dike

seamlessly integrates into the undulating landscape. It is wide enough to accommodate infrastructure. The current farm moves temporary to the save side of the dike and continues dairy farming on the remaining dry lands.

83

85

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Water transport

Before the natural dynamics enter the area, minimal interventions in the land are made to transport water from the highest point to the lowest point in the area. Existing waterways are connected to each other and widened to match the width of the Kirikiri stream for a continues

wateflow. The dike is breached at the highest and lowest points to allow the flow of fresh water and tidal dynamics into the area. Water forces will erode the waterway on the outer corners and deposits will occur on the inner bend. From this point onwards, nature codesigns the area. >

89

91

Sedimentation

It is uncertain how water will shape the area precisely, but a prediction is outlined below, where forces on the inner and outer bends will move the water flow through the area. Simultaneously, sediments will be deposited in the area. Meadow will change into mudflat.

92

93

94

Landification

Due to sedimentation, the land will elevate. The exact rate of this process cannot be determined as the rise in sea level is unpredictable. There will be a phase where mangrove seeds will remain, leading to spread mangrovetrees like weeds in this area, ultimately accelerating the sedimentation process.

95

Reflection

If it appears that insufficient sediments are being supplied, the breach in the dike at the lowest point can be widened, or an additional breach can be excavated at another logical location in the dike.

Constructions in the area can also be utilized to facilitate better sediment deposition. In case freshwater inhibits the growth of mangroves, the dike at the highest point can be temporarily closed.

97

Sediimentatino and construction (Doedens, 2024)

Build along

It is likely that the creeks will follow their old patterns as the old topography still partly exists in the landscape. Based on the new water flow, further development can occur, and places like Hurumoimoi can be

made accessible by boat. The exact location of a jetty can be determined at that time. Its design will refer to the river stones lying upstream in the river, from which the river derives its name (Kirikiri = riverstones)

99

Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river

Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river

Succession

Depending on the elevation of the land, various plant species will grow. Once the area becomes land, succession will take place. Where it is still vegetated with mangroves in

the tidal zone, it will be covered with marshland when the land reaches a sufficient elevation. Subsequently, more shrubs will establish and then grow into Kahikatea swamp forest.

Mangrove

In a normal rate of growth, this area could be land in almost 20 years, with help from mangrovetrees. Depending on sea level rise, mangroves will grow with it until the point where the land accretion process outpaces sea level rise.

Changing mangrove environment (Grace, 2015)

Changing mangrove environment (Grace, 2015)

Grow conditions

Based on the existing topography, areas where marshland already grows on the dikes can be identified. These areas lie just above the highest tide and are therefore suitable for kahikatea trees to grow as well. Forest can be planted here to accelerate

the growth process and to produce timber as a economic model. Simultaneously, the temporary dike and areas behind the dike are suitable for kahikatea tree growth. 4500 trees can be planted within the shape of the current topography.

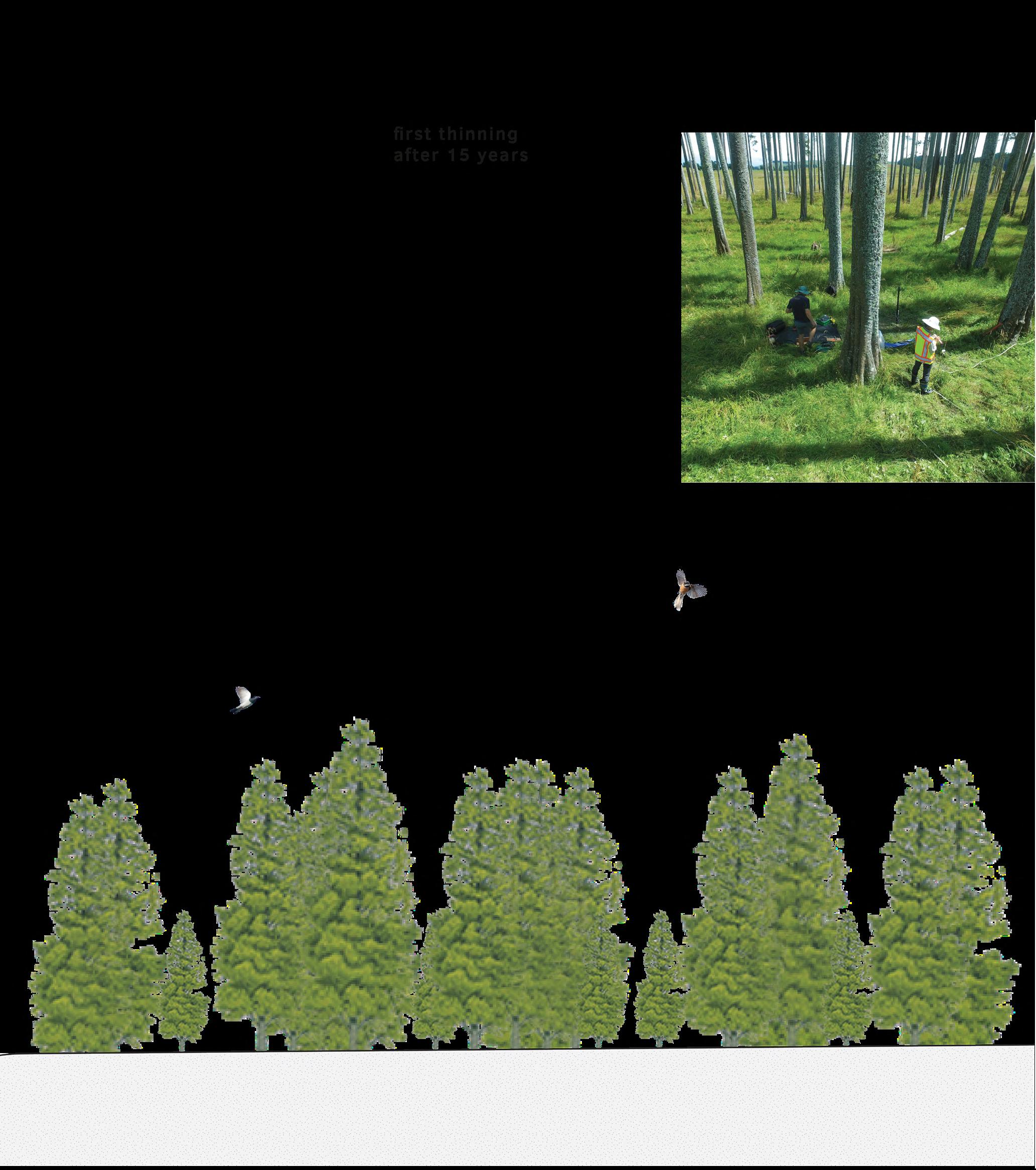

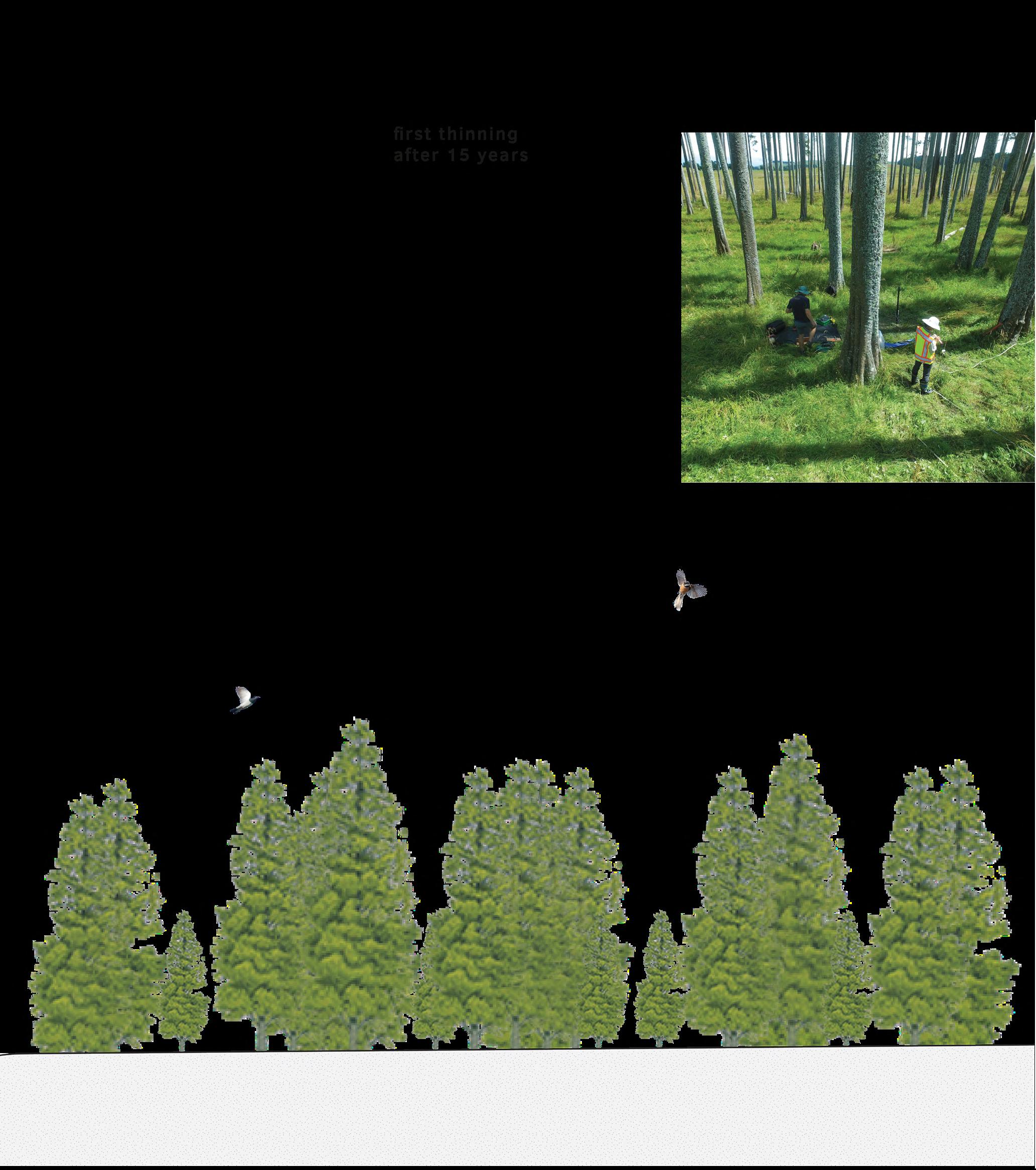

Forest plantation

The trees can be sustainably planted and harvested. Rejuvenation of the forest can be done by initially planting three times more trees than the space needed by the trees in mature state. As the forest grows, it will be thinned out, and this wood can be used for other purposes like construction material. >

109

110

111

112

113

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

116

Living sites

When the sea level in the future reaches a critical point where even the temporary dike is not sufficiently high, it is time to reintroduce the former temporary living areas of Māori.

Creek village (Bollard, 2024) The kainga of Te Kumi (Library, 2022)

Creek village (Bollard, 2024) The kainga of Te Kumi (Library, 2022)

118

Local construction

Raising the mounds again with local building materials such as shells can be used for this purpose. The already raised mounds will be raised again to the new situation.

119

Wooden construction

The residents who still live safely behind the temporary dike at that time will move to the new mounds, built from wood produced locally in the area.

121

Housing in Hauraki Plains (Bayleys, 2024)

Communal living

Dwellings will be built in clusters of six and within a equivalent plotsize as today. With a complete orientation to the landscape and a communal area being part of the urban design, it refers to how the former temporary dwellings were fully integrated into the landscape.

123

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Hinterland

Now that there is no longer any danger to the residents in the hinterland, the hinterland can be opened up according to the same principles as how the first part was initially opened up to natural dynamics. Depending on the topography and watercourses at that time, the dike will be breached in various places. This will have effect on the accesibility. .

127

Sedimentation

Tidal dynamics will now also irrigate the hinterland, and sedimentation processes will raise the land.

128

129

Succession

It is likely that once again the mangrove forests will follow the high tide zone and settle in this area. If this does not happen, it can also be chosen to wait until the area transforms into marshland, on which new kahikatea forests can be planted.

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

REFLECTION REFLECTION

136

Symbiotic landscape

This project shows a transformation from a monotonous landscape to a symbiotic landscape. Natural dynamics have become part of the planning strategy, bringing uncertainties with them. By not reasoning from a final image but reasoning from a step-by-step plan, the landscape gradually

takes shape. With minimal interventions and trust in nature, it is possible to grow in a delta area. This planning strategy could be applied in any delta area, including the Netherlands. The next step is a different way of living, with different forms of production, different infrastructure, and uncertainties that are to some extent controllable. It shows

that climate change does not necessarily have to be a threat as long as nature is embraced.

This project goes beyond postmodernism and is a statement of the symbiocene, in which humans, nature, and technology are finding a new balance together. Living in harmony with nature, which Māori are very good at

137

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

EPILOGUE EPILOGUE

Fieldwork supported by:

Special thanks

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Kaumātua Waati Ngamane for sharing his insights into his traditional Māori cultural worldview. I am grateful for the genuine and warm conversations we had, which will always stay with me.

I also thank Toon van Meijl, professor of cultural anthropology, for his assistance in preparing my fieldwork research in New Zealand and for sharing his knowledge about Māori culture.

Of course, I am thankfull to my committee members, Lodewijk, Bruno and Alexander, for their guidance and patience throughout this dynamic study process. Without their expertise, critical questions and remarks, and numerous extra sessions, this project would not have been acomplished.

I want to thank Marjolein, who supported me throughout the entire study period and who had to participate in this emotional rollercoaster!

lastly, I would like to thank the following individuals who directly or indirectly contributed to this project:

‘Jacky’

Matai Whetū marae caretaker

Alex Foulkes

Conservation biologist at the Department of Conservation

Marc Weeber

Researcher Water Quality & Ecology

Rogier Westerhoff

Geophysicist and Remote Sensing Scientist

Deniz Özkundakci

Freshwater ecologist

Erik Horstman

Assistant professor Water Engineering & Management

Joeri de Bekker

Collegue and landscape architect

Jasper Mallekoote

Former collegue and landscape designer

Hanneke Kijne

Former head of master landscape architecture

Bibliography

Images

Aucklandnz. (2024). Discover Auckland. From https://www. aucklandnz.com/explore/te-hana-te-ao-marama

Bayleys. (2024). Bayleys. From Bayleys: https://www.bayleys. co.nz/listings/lifestyle/waikato/hauraki/147-ngataipua-roadturua-2315193

Bollard, W. (2024). Māori Kainga on the Waikato River. From Sarjeant Art Gallery: https://collection.sarjeant.org.nz/ objects/47103/Māori-kainga-on-the-waikato-river Cowpland, J. (2022, 6 6). Valley profile. From https://www. valleyprofile.co.nz/2022/06/06/the-jobs-not-finished/

Doedens, B. (2024). Wadland. From SLEM: https://www.slem.nl/ projecten/wadland/downloads/

Gallery, A. a. (2024). Mātauranga Māori and science. From Science learning hub: https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/ resources/2545-matauranga-Māori-and-science

Grace, R. (2015, 3 9). The Value of Mangroves in Whangateau Harbour. From whangateau harbour Ccare: https:// whangateauharbour.wordpress.com/2015/03/09/1276/

Library, A. T. (2022, 9). Research gate. From Decolonising Flooding and Risk Management: Indigenous Peoples, Settler Colonialism, and Memories of Environmental Injustices: https:// www.researchgate.net/figure/The-kainga-village-of-Te-Kumisituated-beside-a-tributary-to-the-Waipa-River_fig3_363387503

mz, A. (2024). Discover Auckland. From https://www.aucklandnz. com/explore/te-hana-te-ao-marama

Watton, G. (2006, 9). Ohinemuri. From The flood of all floods: https://www.ohinemuri.org.nz/journals/journal-50september-2006/the-flood-of-all-floods

Literature

Carter, L. (2019). Indiginous pacific approaches to climate change. Dunedin: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Committee, S. (2008). Te Aranga - Maori cultural landscape

strategy. Auckland: Auckland Design Manual.

Council, W. r. (2021). Kahikatea forest fragments: managing a Waikato icon. Waikato: Waikato regional Council.

Darren N. T. King, J. G. (2007). Māori environmental knowledge and natural hazards in Aotearoa‐New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 59-73.

Harmsworth, G. R. (2013). Indiginous Maori knowledge and perspectives of ecosystems. Indiginous Maori knowledge and perspectives of ecosystems, 274-286 .

Hill, C. (2021). Kia Whakanuia Te Whenua. Auckland: Mary Egab Publishing.

Horstman, E. M. (2018). The Dynamics of Expanding Mangroves in New Zealand. The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand: Springer International Publishing.

Jim Nicholls, B. W. (2004). Whaia Te Mahere Taiao o HaurakiHauraki iwi environmental plan.

N., Osborne, B., Lovegrove, T., Jamieson, A., Boow, J., Sawyer, J., . . . Webb, C. (2017). Indigenous terrestrial and wetland ecosystems of Auckland. Auckland : Auckland Council.

Phillips, C. (2000). Waihou Journeys: The Archaeology of 400 Years of Māori Settlement. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Rogers, N. J. (2014). A classification of New Zealand’s terrestrial ecosystems. Wellington: Department of Conservation. From Department of Conservation.

Runanga, N. M. (2020). Cultural values assessment for Thames Coromandel District Council - Kopu marine project.

Smith, H. (2021). Collaborative Strategies for Re-Enhancing Hapū Connections to Lands and Making Changes with Our Climate. The Contemporary Pacific, 21-46.

Temmerman, S. (2022). Marshes and Mangroves as Nature-Based Coastal Storm Buffers. Annual Review of Marine Science.

Young, D. (2021). Wai Pasifika, indiginous ways in a changing climate. Dunedin: Otago Universiity Press.

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Bridging places

Photo taken in Kauaeranga valley

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Fast drainage

Photo taken at Thames city

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Photo storm

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Visible cracks

Photo taken at Gaysorn’s house

Photo storm

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Erosion and deposition

Photo taken along Kirikiri stream

Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river

Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river Mangroves innerworld

Photo taken along Waihou river

Changing mangrove environment (Grace, 2015)

Changing mangrove environment (Grace, 2015)

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Off grid living

Photo taken at Louise’s place

Creek village (Bollard, 2024) The kainga of Te Kumi (Library, 2022)

Creek village (Bollard, 2024) The kainga of Te Kumi (Library, 2022)

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Peatbog in hinterlands

Photo taken south of Hauraki Plains

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

Kahikatea forest

Photo taken in Whanganui national park

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland

End of the tunnel

Photo taken in Auckland