Amsterdam Academy of Architecture Annual Review 2024–2025 Architecture

RESEARCHING

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture Annual Review 2024–2025

DESIGNING FORWARD

Every academic year students tell a story. Not one singular narrative, but a layered composition of voices, ideas and experiments that together reflect the evolving identity of our community. This Annual Review is a collection of such narratives, from the lecture hall to the studio floor and from the first drawings to final reflections. Together they capture the momentum of a year in which urgency, resilience and transformation were recurring themes. One striking thread is the growing importance of transdisciplinarity and the awareness that spatial design cannot be practised in isolation. In various articles, we see the academy opening its doors to guest lecturers from beyond the traditional boundaries of design, to voices from activism, journalism and science. This openness is not merely additive; it transforms how students position themselves as designers and how the academy functions as a learning environment. From the reorganisation of projects to allow more space for critical discourse, to the revision of assessment tools to clarify learning goals, the academy continuously adapts to stay relevant. These educational reforms are echoed in the academy’s broader cultural shifts. The academy makes a conscious effort to make room for reflection and depth, for meaningful feedback and collective learning moments. Events like the graduation weekend reinforce the idea that education is a shared journey rather than a linear path to a diploma.

Yet this year’s contributions to the Annual Review also underscore the urgent questions that remain. What is the role of the architect, urbanist or landscape architect in the face of climate collapse, social fragmentation or technological acceleration? The presence of activism within the curriculum, the inclusion of narrative and research as equal to design, and the space made for imaginative speculation all suggest that the academy sees its task not just in educating professionals, but in equipping students to rethink what professionalism means.

One of the recurring concerns among students is the combination of an intensive workload and employment. The academy has taken several steps to alleviate this pressure, including an expansion of self-study weeks. In the 2024–2025 academic year, students now benefit from two two-week periods without scheduled classes (with an exception in the first year). These breaks are intended not only for recuperation, but also to encourage a greater sense of ownership and self-direction in the learning process. To reduce pressure in the second semester of the third year,

the practice module Design and Management has been moved to the second year. As a result, the Winter School is now attended only by firstyear students. Employment continues to be monitored closely and was the focus of this year’s employers’ meeting, a report of which is included in this Annual Review.

Looking ahead, the themes in this Annual Review challenge the academy to continue evolving. First, the emphasis on reflective, ethical and narrative competence alongside technical mastery must be sustained. The academy has to ensure that students not only acquire skills, but also develop critical judgement. Second, it remains essential to question for whom we are designing, and who is missing from the conversation. Finally, there is the matter of care for each other, for the world we inhabit and for the academy as an institution. The past year has shown how care can be operationalised in policy, pedagogy and programming. It has also shown that care is fragile: it demands constant attention and it must be embedded in structures, not just intentions. This Annual Review does not offer a fixed image of the academy. Instead, it offers glimpses, of students taking ownership of their learning, of guest teachers and staff harnessing their professionalism and of programmes adapting to new realities. These glimpses point to a dynamic and vibrant culture of making, reflecting and learning together.

This year’s edition of the Annual Review serves not only as a record of what was, but as a provocation for what could be. The academy is a place of continuous reinvention. In that spirit, we invite you to read these pages as a call to action: to remain curious, to stay critical and to keep designing futures that are as inclusive and imaginative as they are necessary.←

MADELEINE MAASKANT, DIRECTOR OF THE

Text

AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE

ESCAPING FROM MODERNISM

In collaboration with the architecture centre Arcam, the Academy of Architecture regularly organises One Lectures: public talks by peers aimed at stimulating professional discourse. On 20 February, landscape architect Dirk Sijmons gave a lecture titled Four Escape Routes from Modernism. Below is an edited version of that lecture. Through critical reflection on political, environmental and spatial realities, it challenges designers to reconsider their roles and responsibilities in a world facing a slow-motion catastrophe.

Text DIRK SIJMONS

These are troubling and confusing times. Our trusted navigation tools and maps no longer serve us: large waves are rolling in from all directions. We might be better off with one of those remarkable Pacific Ocean maps, where navigators discern the presence of islands by observing the shape and direction of the waves. These are maps designed for dynamic environments. My lecture is titled Four Escape Routes from Modernism. This title may raise questions: are there only four? Is there a preference among them? We’ll return to that later. My interest in escaping modernism began a few years ago when I developed a plan for the CBK art foundation in Zeeland, titled Pop Down, Melt Up, in the vicinity of the Borssele nuclear reactor. The insights we gained there were applied again a few years later. Last year, together with Herman Kossmann, Wouter van Stiphout and Michelle Provoost, I was invited by the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR) to present the findings of twelve students from ten different countries of the Independent School for the City. Our focus was the Rotterdam area, imagined at 2.5 degrees Celsius warmer than today. We were asked to create the exit of the IABR, both literally and figuratively. We produced a billboard with a ticker tape reading: ‘When do we stop pretending all this is going to end well?’ That became our key phrase. A world that is 2.5 degrees warmer is not one we would still recognise. Many people fail to realise that 2.5 degrees of warming is already catastrophic, and this is the current projection for the end of this century.

The billboard featured three wheels of history turning at different speeds: the wheel of politics, the wheel of temperature and the wheel of planetary boundaries. At the vernissage, people asked me: ‘Are you a pessimist?’ Citing the American author Eugene Thacker, I replied: ‘On my better days, I am a pessimist.’1 Of course, I’m not truly pessimistic. I see myself more as a realist. As designers, if we are to be realistic, we must reflect on our worldview and our professional stance. Are we part of the problem, or part of the solution? This self-reflection is deeply tied to the enduring influence of modernism in our thinking. Like many of my generation, I was steeped in modernism. As a child, I devoured science fiction books filled with optimism about the future. Modernism is deeply ingrained in our Western mindset.

To the architects in the room: I’m not speaking of modernism as an architectural style. That is merely one of many expressions of modernist thinking, which has its roots in the Enlightenment. Let us instead consider modernism as a mindset. Modernism regards nature and its resources as unchanging givens. It envisions society progressing towards emancipation. Humanity, in this view, is strong enough to cast off the shackles of nature. The core values of modernist thought are freedom and detachment from the natural environment. Politicians and designers articulate their ideals in malleable, utopian terms.

Modernism is omnipresent. Consider the Icon of the Seas, a cruise ship that began service last year. It is astonishing: one of the largest cruise ships in the world, essentially a floating theme park with twenty decks and over five thousand passengers. From a sustainability perspective, it is hailed as a major breakthrough, as it runs on liquefied natural gas rather than heavy fuel oil. This is a perfect example of the illusion that sustainability will save us. But taking hedonistic cruises makes us part of the problem, not the solution.

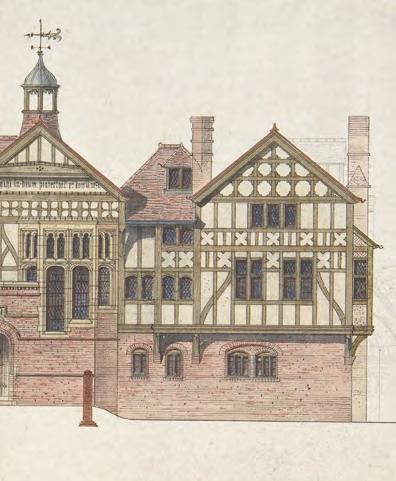

Another example is The Line, a 170-km-long linear city under construction in Saudi Arabia, designed to house nine million people. Marketed as ‘the next best thing in sustainability’, it claims to produce ‘no carbon emissions’. That might be true – though likely not – if one disregards the vast amounts of CO2 embedded in its construction. Modernism, it seems, is still very much alive and has relocated to the desert. The Line bears a striking resemblance to Le Corbusier’s 1933 Plan Obus for Algiers. It is equally megalomaniacal. Whether it will ever be completed remains to be seen, but its ambition is modernism in its purest form.

Here in the Netherlands, we too are capable of such grandiose schemes. There are proposals for a massive sea defence and hydroelectric plant in the North Sea, intended to safeguard the entire province of Zeeland. The concept involves using wind energy to pump seawater up over 30 metres into a reservoir, releasing it later to generate large amounts of electricity. On paper, it’s an ingenious solution for temporary energy storage. A win-win situation. However, the collateral damage would be the destruction of the estuaries between the islands: a premeditated murder of the delta’s estuarine character.

These three examples illustrate how modernism remains very much alive. I will now take a closer look at the three wheels of history on our IABR billboard: the wheel of politics, the wheel of temperature and the wheel of planetary boundaries. I will address them one by one, although they are interconnected. The first is the wheel of politics. One might ask: ‘Why are we, specialists in the built environment, discussing politics?’ There are several valid reasons for doing so. One is the observation that in every authoritarian regime, there are direct links between the political leader, the economic elite and the building and real estate sector. This is also true in democratic countries such as the Netherlands, albeit less overtly. In countries like Russia and – more recently – the United States, these connections are out in the open. The president of the United States is a real estate tycoon whose political agenda is traditionalist, nativist, nationalist and profoundly anti-modernist. Is this cause for concern? Undoubtedly. Consider the early signs of digital book burning. One of the first acts of the new US president was the removal of all references to climate change from the websites of federal agencies. That was just the beginning. Scientists have expressed fears that vital data may also be erased from federal servers. This is a clear example of absolute denialism. A counterreaction may arise in time, but the current situation is alarming. Some believe the Netherlands is immune to such developments. We often say: ‘The Netherlands lags fifty years behind the United States.’ But our current administration’s political agenda shows striking similarities. Here too, the prevailing agenda is decidedly anti-modernist. →

Now to the wheel of temperature. Each year brings new record high monthly temperatures. This is a direct result of the vast amounts of greenhouse gases we emit. In a span of four to five hundred years, we are burning the biomass that took the Earth approximately 500 million years to produce. These emissions include not only CO2, but also methane and other gases. There is simply too much heat in the system. Numerous mitigation efforts are underway – the installation of solar panels being one example – but one particular indicator on the Earth’s dashboard deserves special attention: the Earth’s energy imbalance. This refers to the difference between the energy the Earth receives from the sun and the amount it radiates back into space. It currently stands at 1.64 watts per square metre. That may sound negligible (equivalent to a small LED light on every square metre of the planet), but when aggregated, it equals the heat output of one million small nuclear bombs exploding every day. There is too much heat trapped into the system. This is the driver of climate change. Its consequences include extreme weather events such as the Palisades Fire in Los Angeles earlier this year. Wildfires triggered by severe drought were driven by hurricane-force Santa Ana winds. Architects were relieved when the fire stopped just short of Case Study House No. 8, the Eames House designed for John Entenza, the editor and publisher of Arts & Architecture magazine.

These kinds of weather events also intensify stationary low-pressure systems, resulting in prolonged and severe rainstorms due to their absorption of warm sea water. The resulting floods have become a common occurrence in recent years: in Germany (2021), Porto Alegre (2023), Valencia (2024) and regularly in Miami. Every region is now at risk of experiencing such disasters. We must accept that these extreme weather events will not remain confined to news coverage, but will increasingly shape our everyday environments. The 2021 flood in Germany also impacted the province of Limburg in the Netherlands. All of these events have occurred with just 1.2 degrees of warming. Scientists warn – and political consensus is emerging – that we are heading towards 2.5 degrees of warming by the end of the century. That is why we began exploring what this would mean for Rotterdam. In his compelling book Six Degrees, Mark Lynas illustrates the value of fighting for every tenth of a degree, describing the potential effects of global warming across all aspects of life.2 Scientists are increasingly concerned that the heat accumulating in the system is bringing us dangerously close to climate tipping points. The most troubling among these is the weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which could have catastrophic consequences for our latitude. If it were to collapse, we could become the cold spot of the planet. The third wheel concerns planetary boundaries. Johan Rockström of the Stockholm Resilience Centre created a well-known infographic illustrating the ‘safe operating space’ for humanity in nine key planetary processes. It reveals that in six of these nine areas, we have already exceeded the Earth’s capacity. For spatial designers, the land use system is especially relevant. I will return to that later. However, other issues such as the disruption of biochemical cycles – for instance, nitrogen and phosphorus – are equally pressing. This is not solely a Dutch issue; it is a global one. Nevertheless, the Netherlands is among the highest emitters in the world.

Biomass burning has a long history in the Netherlands. Peat extraction has shaped the landscape of Nieuwkoop.

Photo Frans Lemmens / Alamy

THE GREAT ACCELERATION

Human activity has had a profound impact on the planet’s natural systems. We are introducing ‘forever chemicals’ such as PFAS, altering sediment flows by damming nearly all major rivers for hydroelectric energy, and increasing land use, not only for urban development, but predominantly through the reclamation of wild lands for agriculture. Collectively, these activities are eroding biodiversity. In 2002 this prompted Dutch atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen to propose a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. He argued that we are no longer living in the Holocene, but in the age of humankind. Naturally, the emergence of the Anthropocene sparked significant debate within the social sciences and geology. It has been linked to what is often referred to as ‘the Great Acceleration’. If you plot the major global indicators on a graph, you’ll see that after 1950, they all skyrocket: exponential increases in energy consumption, population growth and urbanisation. Some interpret this as a graph of progress. Others, such as French philosopher Bruno Latour, see it differently. ‘This is the apocalypse,’ he says. But not an apocalypse in the traditional sense – not four black horsemen galloping through the night, laying waste to everything. Rather, it is an apocalypse in slow motion. Our wealth is our apocalypse. →

The Line, a proposed 170-km linear city within the Neom megaproject in Saudi Arabia, is marketed as ‘the next best thing in sustainability’.

The book Apocalypsofie by philosopher Lisa Doeland is a key reference for the North Sea Canal region design commission, a project we’re conducting with Arcam, the Amsterdam centre for architecture.³ If we are facing a slow-motion disaster and are drafting a disaster plan, what precisely is the disaster we’re planning for?

The disaster is the situation we are already in. It’s not a sudden explosion of an oil tanker, nor the leaking of toxic chemicals in the Volgermeerpolder. No, the situation itself is the disaster. Designers working on this project must be almost entirely reprogrammed not to think in terms of progress, but to fully comprehend that we are living amid an unfolding apocalypse.

The beginning of the Anthropocene marks the onset of this disaster, nearly seventy years ago. A more precise definition comes from Indian-American scholar Dipesh Chakrabarty, who argues that the Anthropocene is the era in which the global economy crashes with the Earth’s planetary boundaries.4 That is the reality we face. This definition urges us to rethink how we engage with disaster planning. Turning our attention to the built environment, a recent article in Nature revealed that the total mass of human-made objects now exceeds the weight of all living biomass on Earth.⁵ This includes everything from the pyramids of Giza to present-day infrastructure. It is almost inconceivable. The article also predicts that this ratio could double or triple in the coming four decades. Think about it: all that we have constructed throughout human history is likely to be replicated in weight within just a few decades. This is the trajectory of exponential growth. Where will this enormous wave of urbanisation end? Where will all the necessary cement and steel come from? Architects must urgently explore alternative construction methods using materials like rammed earth, bamboo and mycelium. We must be radical. But another urgent question arises: where will this urbanisation take place? The website Atlas for the End of the World, created by Australian landscape architect and academic Richard Weller, maps global biodiversity hotspots.6 Strikingly, these areas almost always overlap with the locations projected for future urban expansion. We are heading towards a direct collision between urbanisation and biodiversity. The atlas pinpoints these emerging conflict zones. In Nairobi, the city’s periphery is encroaching on rhino habitats. In Mumbai, sprawling slums have entirely surrounded a nature reserve still inhabited by a thriving population of leopards, now forced into the urban fabric. We must radically rethink land use planning if we hope to preserve natural areas. Here in the Netherlands, it’s fashionable to talk about urban nature, but this is an entirely different matter altogether. The only viable path forward in addressing these prolems is to slow the global economy. Yet this is no easy feat. Almost every synonym for ‘shrinkage’ carries negative connotations. Conversely, terms like ‘growth’ and ‘progress’ are intrinsically positive in our culture. It’s ingrained in our DNA. To slow down an economy is to row against the current. Alan Berger, professor of landscape architecture and urban design at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, asserts that systemic design can change the world.7 While that’s an inspiring claim, I think we must be more modest about the power of design. As early as 1971, Austrian architect Hermann Czech reflected on the limits of his profession: ‘Architecture is not life itself. Architecture is just the backcloth, the background. All the other things are not architecture. Architecture won’t solve our political, our social, not even our environmental problems, just as music won’t solve our noise pollution problems.’8

The 1970s were a period of reckoning, a hangover from the era of spatial determinism. Spatial determinism is the idea that societal problems can be handed over to an architect who will then solve them through spatial interventions. Fortunately, Czech’s aphorism doesn’t stop composers from creating beautiful music, nor should it stop landscape architects from working on meaningful projects. Landscape architecture can indeed contribute to addressing today’s challenges. We can assume at least four professional roles. In our day-to-day practice, we function as designers fulfilling assignments. But we can also become landscape activists, operating without a client, treating the landscape itself as our client. In addition, we can work as landscape researchers, using research by design to address issues that would never otherwise attract funding. And finally, we can take on the role of landscape artists.

As spatial designers, we must be honest about our impact. When we overreach, we fail to deliver, but we must also not underestimate our capabilities. All the transitions currently being discussed intersect in the spatial domain, presenting us with an immense task. Everything requires a world in which to exist, and the world we will inhabit is the one we design. That is the condition of the Anthropocene.Let us now contrast the key tenets of modernist thought with the Anthropocene perspective. The modernist belief in the immutability of natural resources gives way to the recognition of Earth as an active agent. Society is no longer progressing toward emancipation but rather is gripped by anxiety – even the air we breathe must be monitored. The ideals of freedom and detachment have shifted towards responsibility. And instead of striving towards a utopian ideal, we are now embedded subjects. Politicians and designers must ask themselves: ‘Do we remain complicit in modernism, or do we stand as part of a counterforce?’

An example of mycelium architecture, the Mushroom Tower was built in the MoMA PS1 courtyard in 2014. Photo Amy Barkow / The Living

There are at least four escape routes from the conundrum of modernism. The first, as already mentioned, is denialism. One approach to these problems is simply to ignore them. We might say: ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ This is the denialist worldview. Climate change is deemed a hoax. The Anthropocene, according to this view, is the ultimate hoax, dreamt up by leftists intent on dismantling our civilisation.Another common escape route is eco-modernism, which emerged in the 1990s as an attempt to align mainstream politics with environmental concerns. It is, at its core, an extension of modernism with the prefix ‘eco’ added. It imagines a world in which anything scientifically or technologically feasible should be pursued: genetic modification, CO2 storage in depleted oil fields, fully climatized agriculture. Its most extreme expression is the proposal to use B52 bombers to disperse sulphur into the atmosphere to cool the Earth. Proponents of this approach argue that economic growth will fund these expensive environmental interventions. We can, they believe, consume our way out of the climate crisis.

This represents a solutionist mindset. Geochemical cycles disrupted? The circular economy will sort that. Sediment flows halted? Implement hard coastal defences. Ocean acidification? Add iron ions and chalk to the water. In this worldview, climate change is seen as an engineering challenge. Biodiversity loss is not considered problematic if invasive species can fill the niches or, ultimately, if it can be tackled through de-extinction programmes. If we solve all these problems one by one, as though ticking off a bulleted list, the final victory for humankind and ‘the Good Anthropocene’ can be proclaimed.

A more recent escape route is posthumanism, a worldview in which all forms of existence and all ontologies are equally valid. Humans are part of a complex web of life, no more or less important than other non-human beings. Posthumanism is increasingly popular. The shift from ego to eco allows us to see ourselves not as the pinnacle of creation, but as one of many living beings. This is a world in which nature is afforded legal standing. The Whanganui River in New Zealand was a pioneer in this regard. Closer to home, the Embassy of the North Sea seeks to give political voice to this body of water. From an artistic perspective, this is an inspiring concept. In practical terms, however, its implementation remains limited. The oat milk elites, as some call them, don’t seem to be marching to the right frontier. Nonetheless, this escape route remains a deeply sympathetic one. The fourth escape route is what I call Anthropocentrism 2.0. It is a response to posthumanism. The premise is: ‘We might wish to see ourselves as just one tiny element in the web of life, but the truth is we are a force – almost a geological force – that has wreaked havoc on the biosphere. We must take responsibility and repair the damage.’ The figurehead of Anthropocentrism 2.0 is Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. in Anthropocentrism 2.0, we return our focus to a more responsible version of the anthropos. A compelling example is Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, whose book Genesis documents the Earth and its indigenous peoples.9 The project stemmed from an artistic crisis. Salgado had spent years embedded as a war photographer in some of the world’s most horrific conflict zones. Emotionally and spiritually exhausted, he decided to create a homage to the living planet. With the proceeds from the resulting book, he and his wife Lélia returned to his father’s deforested hacienda and established three nurseries to reforest the land. Today, it is home to 200 species from the Atlantic rainforest. I might never have learned of this if German filmmaker Wim Wenders had not made a documentary about it, The Salt of the Earth. For me, this is the essence of Anthropocentrism 2.0: restoring, repairing and reconnecting. It is a form of inverse engineering. To be clear, this is not an anti-technological stance. It is about viewing science and technology through a Goethean lens, one that advocates for reflection and debate before such tools are unleashed upon society and the biosphere. Otherwise, we risk producing the kind of unintended consequences Goethe described in his poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice –effects beyond our control.These, then, are four escape routes from modernism. They can be organised into a simple quadrant. It is my adaptation of

and

The denialist remains trapped in the present, yearning for a past that never existed. The eco-modernist proclaims that the best is always yet to come. The posthumanist embraces ontological pluralism and is convinced that the environmental crisis is a spiritual crisis at heart. Anthropocentrism 2.0, by contrast, offers a more sober – and arguably more realistic – outlook: the worst might still be averted. These four approaches show that there are not just four escape routes from modernism. The quadrant allows for a multitude of nuanced positions. You can even use it to situate various philosophers: Clive Hamilton fits squarely within the anthropocentrism 2.0 quadrant; Yuval Harari straddles eco-modernism and anthropocentrism 2.0; Steven Pinker, ever the optimist, sits somewhere between denialism and eco-modernism. You can apply this framework to your own bookshelf, categorising authors according to their philosophical stance.

To be honest, about 90 percent of today’s environmental discourse resides on the left-hand side of the quadrant. Just 10 percent occupies the right. These are the pioneers. Posthumanism is gaining traction in artistic circles. Few, however, fully adopt the stance of anthropocentrism 2.0. The quadrant helps us identify the ideological rifts in the environmental debate. Denialism persists due to cognitive dissonance. Eco-modernism gains momentum by offering hope: the belief that economic growth can continue, if only we adjust our environmental regulations. Anthropocentrism 2.0 is propelled by scientific insight, but the associated ethical discourse in science often lags behind technological progress. Posthumanism fosters new forms of empathy, but its application remains limited given the scale of today’s challenges.

This quadrant also teaches us that no single escape route will dominate the conversation. As designers, we must learn to navigate between these positions. Recognising the stance of your discussion partners can help. It might even be possible to combine the strongest aspects of each approach. Even denialism has something to offer: a sense of detachment, casualness, even a kind of lost innocence. Let us aim for that detachment without the naivety. From eco-modernism, we can take the delight in designing and making, but without the hubris of complete control. From posthumanism, we might embrace its empathy for the non-human, but without its obscurantism. And from anthropocentrism 2.0, we should adopt the impulse to heal, but without slipping into moralism or finger-wagging. With these lessons in mind, we – as architects, researchers, activists and landscape artists – can become reflective practitioners capable of engaging with a wide array of challenges.

I’d like to end with a quote I’ve always appreciated, from William Burroughs, published in a 1979 interview in High Times Magazine: ‘Optimist, pessimist. In a storm, some will say the ship will sink, others will say it will stay afloat. Who is to say who’s the optimist and who’s the pessimist? It all depends on whether the ship is really sinking or not. (…) Both pessimist and optimist are meaningless words.’10 ←

1 Eugene Thacker, Cosmic Pessimism, Univocal Publishing, Minneapolis, 2015, p. 58.

2 Mark Lynas, Six Degrees: Our future on a hotter planet, 4th Estate, London, 2007.

3 Lisa Doeland, Apocalypsofie: Over recycling, groene groei en andere gevaarlijke fantasieën, Ten Have, Utrecht, 2023.

4 Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2021.

5 Emily Elhacham, Liad Ben-Uri, Jonathan Grozovski, Yinon M. Bar-On, Ron Milo, ‘Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass’, Nature 588 (2020) 442444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5

6 https://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world. com/

7 Alan Berger, Systemic Design can Change the World, SUN, Amsterdam, 2009.

8 Herman Czech, ‘Nur keiner Panik’, in: Zur Abwechslung Ausgewählte Schriften zur Architectur, Locker Verlag, Vienna, 1977. English translation from Elise Feiersinger (ed.), Essays on Architecture and City Planning, Park Books, Zurich, 2019.

9 Sebastian Salgado, Genesis, Taschen, Cologne, 2013.

10 Victor Bockris, ‘Interview: William Burroughs’, High Times Magazine, 42 (February 1979).

An atomic explosion during the Baker test of Operation Crossroads in the Bikini Atoll on 24 July 1946.

PLURALITY OF PERSPECTIVES

Architect Estelle Barriol, founder of Studio ACTE in Rotterdam, was invited as a guest critic for the 2024 Graduation Weekend. In the piece below, she shares her perspective on the projects presented.

Text ESTELLE BARRIOL Photos JONATHAN ANDREW

This year’s graduation projects reflect a fascinating plurality of perspectives, with an increasing emphasis on alternative ways of living and building. The work of young professionals and students reveals a heightened awareness of the social, environmental and political challenges shaping both present and future. From imagining habitable environments on the moon to investigations into politics, ecology and materiality, these projects directly engage with contemporary contexts and ongoing tensions.

In many cases, ecology is explored as a systemic concept encompassing social, climatic and historical dimensions. Projects that address resource extraction, colonial legacies and long-term sustainability highlight the complementarity between spatial design and the social sciences. At a time when figures such as Elon Musk provoke discourse around extraterrestrial living, projects cast a critical gaze on the emerging realities of space and interrogate what it means to design for alternative modes of living and working.

A standout theme is the focus on wind and its integration into architectural design. This line of inquiry delves into the relationship between wind and space, underlining the importance of reconsidering natural phenomena as design parameters. At a moment when cities around the world are vying to build ever-taller structures, these projects demonstrate how wind –both a constraint and an opportunity – can redefine the interaction between the built environment, climate and nature, while also bridging disciplines.

Several projects adopt speculative and futuristic approaches, boldly reimagining living models and forms of habitation. Many employ research by design as a methodology, demonstrating the value of inquiry and experimentation in generating novel spatial forms. For architects, urbanists and landscape architects, this approach emerges as a crucial tool for reflection, enabling practitioners to respond meaningfully to complex conditions. Research is embedded within the design process, producing new narratives and frameworks. →

The diversity of representational tools employed reveals the multidisciplinary and cross-disciplinary ethos within the Academy. The capacity to conceive and articulate space through a range of media leads to generous and often unexpected outcomes. These tools not only help frame spatial arguments but also encourage exploration and experimentation in the face of multifaceted subjects and contexts. This multiplicity should continue to be embraced as a strength in the professional field. When combined with more conventional techniques, it introduces new possibilities for expression and communication.

The underlying utopianism evident in many projects signals a nuanced engagement with the intricacies of reality. It echoes the difficulty of envisioning ecological futures while designing spaces that resonate with evolving political landscapes. While utopia has long served as a source of inspiration in architecture, it remains essential to translate idealism into resilient, adaptable and impactful spatial interventions. Spatial design must aspire to cultivate environments that are inclusive, sustainable and transformative. Themes of utopia, care, transformation and refurbishment reverberate strongly throughout the projects. These themes underscore the value of ‘making do’ – of working with existing conditions and recognising transformation as a potent and sustainable act. Collectively, the projects reflect a generation of designers unafraid to challenge conventions and eager to redefine the boundaries of their disciplines. ←

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATIONS

Additionally, both the Research Award and the (R)evolution Planet Award were awarded to Lunar Thais Zuchetti (architecture). The Engagement Award went to Vincent Lulzac (landscape architecture) and the Audience Award to Dennis Koek (architecture). The Archiprix Netherlands 2025 ceremony took place on 14 June. It had four first prizes; one for each of the four disciplines (architecture, urbanism, landscape architecture and interior architecture). The first prize for landscape architecture was for Renan Dijkinga.

At the close of the Graduation Weekend 2024, director Madeleine Maaskant announced the four nominations for the Archiprix Netherlands. The nominated graduation projects were: (Be)Coming Home by Renan Dijkinga (landscape architecture), Low-Tech Haven by Iaroslava Nesterenko (urbanism), The Creature by Minnari Lee (architecture) and Wind-Woven by Rachel Borovska (landscape architecture).

The Amsterdam Academy of Architecture nominated two landscape architecture projects, one architecture project and one urbanism project for the annual Archiprix Netherlands competition.

(BE)COMING HOME

Landscapes of belonging: home for all.

STUDENT Renan Dijkinga

MASTER Landscape Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 29 August 2024

MENTOR Jana Crepon

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Jacques Abelman and Raul

Corrêa-Smith

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Berdie Olthof and Marieke

Timmermans

ARCHIPRIX WINNER

(Be)coming Home focuses on the Campos Gerais region and the Devonian Scarp in southern Brazil, my home. This area’s identity is shaped by a rich tapestry of geological, natural and cultural-historical layers. However, without efforts to bridge these dynamics, and with rising monocultures, exotic species forestry and unregulated tourism, the region risks becoming inhospitable.

This project envisions a future where people recon-

Elements of home: personal collection and family archive.

nect with the land, blending traditional practices with natural systems. It introduces new ways for locals to engage with the landscape, transforming land use to create opportunities for residents and landowners. These initiatives aim to regenerate the environment, attract new economic activity and help communities rediscover the beauty of their surroundings.

Central is a network of natural and cultural tourism sites, linking properties through regenerative land

use. These interventions generate income, support biodiversity and strengthen connections between people and place, healing damaged areas and fostering stewardship.

Landscape architecture plays a key role in preserving and reinforcing local identity. This strategy uses the region’s tourist potential, focusing first on local residents. By encouraging them to engage with diverse land uses and activities, tourism becomes

a tool for fostering environmental pride. Tourists, though welcome, are secondary.

Diverse land uses create opportunities for locals to live within and care for their landscape. This benefits communities and preserves the cultural and environmental heritage of one of Brazil’s most valuable regions. Ultimately, (Be)coming Home invites a sustainable environment where nature and humanity thrive together, offering a place to belong.

Geological dynamics.

Cultural dynamics.

Biodiversity dynamics.

(Be)coming Home: hopeful vision for the future.

Proposal applied in the city of Carambeí, Brazil.

New dynamics section: proposal for land uses, activities and collaboration between layers.

Illustration of the new potentials to reconnect with the landscape.

Plan of the node, showing its recreational function and erosion control. The planting scheme, composed of native edible species, allows visitors to help spread seeds along the pathways.

Detail of the node.

South-westerly winds bring strong cold air; summer winds come from the east.

Wind patterns explored along Breda’s 8-km railway corridor, which cuts through vulnerable climatopes prone to heat accumulation. Climatopes are areas with similar microclimatic characteristics.

STUDENT Rachel Borovska

MASTER Landscape Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 28 February 2024

MENTOR Gert-Jan Wisse

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Nikol Dietz and René van der Velde

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Marit Janse and Ziega van den Berk

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATION

Urban heat islands are a major challenge in today’s cities, alongside the need for cooling and biodiversity. While interventions often focus on depaving, greenifying and reclaiming space for green-blue networks, the role of ventilation in cooling is frequently overlooked. This project, driven by a fascination with the thermodynamic performance of wind, seeks to address that gap by using weather, climate and atmosphere as design mediums.

This research-by-design project explores how wind can enhance cooling, focusing on two dominant wind directions in the Netherlands. South-westerly winds bring strong, cold air from autumn to spring, while summer easterlies can worsen urban heat if obstructed by dense streets or vegetation, reducing human comfort and ecological habitats.

The 8-km-long railway corridor in Breda, running east to west, is used to study wind as a design tool. Rail-

ways have expansive linear profiles and open surfaces that support ventilation and shape local climates. They also function as ecological corridors, enabling wildlife migration and seed dispersal. The railway and its surroundings become a testbed for cooling compositions and landscape interventions. These areas are not treated as blank slates but as vital components in ventilation, ecology and cooling. Wind becomes a medium to compose a green wedge

that integrates with the existing urban fabric. The result is a park-like necklace – an ecological and biodiverse network shaped by wind – running alongside the railway strip of Breda, connecting neighbourhoods and enhancing climate resilience.

A park-like necklace shaped by wind along the railway strip of Breda.

Plan West. The west, exposed to south-westerly winds, uses existing tree lines and adds new trees to shape outdoor rooms.

West blue grasslands. Summer ‘wind room’ impression. Slight topography variation creates shelter for paths, recreation and pollinators.

West beehive autumn. Autumn winds are filtered by trees and shrubs. Wind helps spiders disperse through ballooning.

Plan East. East stream channels summer winds, cooled by tree canopy shade and water surfaces.

Wind-woven axonometries. Topography, water, vegetation and roughness shape wind patterns and diverse microclimates.

Industrial climatope ‘t Zoet explored as a wind disperser via its green-blue network and land composition.

LOW-TECH HAVEN

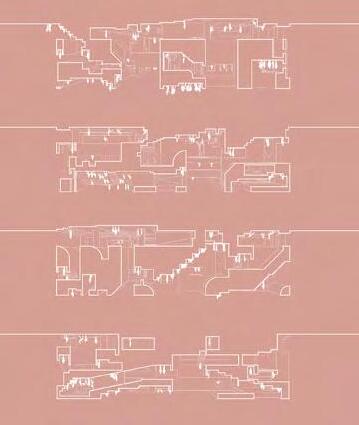

The design introduces four green parks and four lively neighbourhoods.

STUDENT Iaroslava Nesterenko

Master Urbanism

GRADUATION DATE 25 March 2024

MENTOR Jerryt Krombeen

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Jandirk Hoekstra † and Hiroki Matsuura

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Marijke Bruinsma and Martin Hopman

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATION

Urban greenery in low-lying areas functions as flood reservoir and recreational space.

My thesis explores how the energy transition affects cities, how to design liveable environments and what urban designers can do to safeguard quality of life during change. It examines urban design, sustainable low-tech energy practices from the past and urban well-being. Having experienced energy contrasts from Russia to the Netherlands – from abundance to austerity, centralised to decentralised systems – this dichot-

omy shapes my perspective on energy transition as a societal and spatial task.

The Dutch landscape, shaped over centuries by varying energy sources, now faces the integration of renewables. How will this new energy layer transform the urban Dutch context?

This thesis redefines energy as a vital component of urban life, influencing spatial and cultural dynamics. It argues that conserving energy should be prioritised

over producing it. A personal narrative on energy use highlights the need to rethink distribution and address technological inefficiencies.

The thesis proposes making cities more resilient, accessible and community-oriented through simple, traditional methods. The focus is on reducing energy use and avoiding dependence on costly technologies.

Initiatives include urban agriculture, low-carbon mobility and community-driven waste systems.

I developed and tested a toolkit of low-tech urban solutions in Groningen. It addresses green-blue networks, passive climate control using solar envelopes and wind, and efficiency in cargo, mobility and food systems. This is an invitation to engage in shaping futures where energy efficiency is woven into all layers of urban life in a practical, sustainable and human-centred way.

Low-tech streets prioritise cyclists, expose utilities, enhance greenery and improve soil water absorption.

Student Haven uses geography and architecture for natural climate control in a low-tech, eco-friendly setting. Agrihood is a community-focused neighbourhood centred around shared agricultural spaces.

Material Haven is a low-tech neighbourhood built using repurposed materials.

Food Haven.

Full axonometry. Design introduces four green parks and four lively neighbourhoods.

THE CREATURE

STUDENT Minnari Lee

MASTER Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 29 January 2024

MENTOR Jeroen van Mechelen

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Jandirk Hoekstra † and Marten Kuijpers

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Geurt Holdijk and Susana Constantino

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATION

The North Sea has long existed as an imaginary space for humanity. This project presents a future archive from the year 2200 in IJmuiden, envisioning a new form of offshore infrastructure: a floating entity that acts as an ‘indeterminate interface’, merging hard technological systems with soft biophysical processes. This entity functions as a regenerative farmer of the North Sea, cultivating seaweed and fish, desalinat-

ing seawater into freshwater, harvesting wave energy and transporting sea products to nearby cities such as IJmuiden. People live nearby and participate in its construction, operation and maintenance in exchange for its ‘harvest’.

The project seeks to redefine our forgotten relationship with resources, landscape, non-humans and natural elements. It challenges conventional infrastructure, which often removes natural ele-

ments to maximise human benefit. Instead, this proposal offers a vision of co-existence and mutual dependency.

Combining theory and practice, the project sets out abstract concepts and anchors them in a tangible model, communicated through various formats including moving images, paintings and sculpture. These mediums help to gradually materialise The Creature.

The Creature over the horizon of IJmuiden.

North Sea gas extraction.

of The Creature, IJmuiden.

Anatomy of The Creature, IJmuiden.

Chamber of Electricity, axonometry.

Chamber of Electricity, principle plan.

The Creature on the North Sea. Chamber of Freshwater, principle section.

LUNAR LESSONS

STUDENT Thais Zuchetti

MASTER Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 29 January 2024

MENTOR Stephan Verkuijlen

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Bernard Foing and Natalie Dixon

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Raul Corrêa-Smith and Rachel Keeton

AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE Research Award and (R)evolution Planet Award

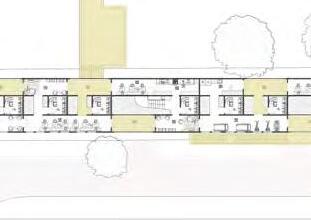

Lunar Lessons is the design of a planetary habitat aimed at knowledge transfer between the Moon and Earth. The idea is to learn from the Moon what it takes to live in an unliveable place, so that such lessons might be applied to an alien Earth in the future. Conversely, the lessons from Earth offer a direct alternative to space exploration settlements, which are often envisioned and developed as clin-

ical and cramped environments that provide only the bare minimum for astronauts. Through the process, it became clear that ‘cramped’ and ‘bare minimum’ conditions are not exclusive to lunar habitats; the lessons from the Moon are closer to home than expected. Lunar Lessons is, in fact, a project about people, regardless of which planet they are on.

Thinking of the people, the Moon base is designed from the perspective of crew wellbeing. It incorporates conceptual architectural techniques from Earth to simulate not only the variety of spaces and atmospheres we are accustomed to on our planet, but also the interactions between people and the rituals from home.

Site plan.

Site plan.

Ground floor plan and entrance to the habitat.

Souterrain floor plan and bedroom module.

Section.

Section.

Souterrain floor plan and bedroom module.

Lantern module, physical model.

Physical model lantern, contemplation room.

Physical model lantern, contemplation room.

ECHOES OF HOME

Visitors are encouraged to interact physically and emotionally with the site. Movement becomes the central mode of engagement.

STUDENT Vincent Lulzac

MASTER Landscape Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 16 April 2024

MENTOR Thijs de Zeeuw

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Lada Hršak and Erik A. de Jong

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Berdie Olthof and Justyna Chmielewska

AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE Engagement Award

Echoes of Home proposes a cultural garden in Nantes, inviting visitors to engage with the geological, hydrological and anthropological foundations of the city.

The 7-ha site lies at the intersection of a 300-km-high geological fault and the 1,000-km-long Loire river, dividing the landscape into wine plateaux, marshlands and riverbeds. Yet, from within the city, the richness of these landscapes remains largely unseen.

Nantes’ strategic position made it a key port in the transatlantic slave trade, triggering rapid urbanisation during the so-called Golden Age, followed by industrialisation along the river. This redefined both the physical and cultural landscape, fostering an identity tied to exotic goods and colonial imageries. In the 20th century, as the maritime industry shifted seaward, quays were abandoned, leaving an indus-

trial void. In response, the city turned to cultural initiatives rooted in its colonial past to maintain dynamism. This has led to a cityscape steeped in nostalgia, yet detached from its local context. The project responds by seeking to liberate itself from extractive narratives and practices. Emerging from a personal ambition to decolonise the discipline of landscape architecture, it aims to reclaim Nantes’

layered heritage. Visitors are encouraged to interact physically and emotionally with the site. Movement becomes the central mode of engagement. The design is conceived as choreography, a spatial dance in which visitors and natural elements move together.

The 7-ha site lies at the intersection of a 300-km-high geological fault and the 1,000-km-long Loire river.

A Garden of Granite, nestled in an old granite quarry, invites visitors to explore geological wonders and natural beauty.

The design of the Garden of Granite is based on movement, dance and music.

The toolbox for the decolonisation of landscape architecture comprises, among others, critical reflection, the reassessment of design approaches and a reconsideration of land use and ownership.

Industrial concrete slabs, which currently cover the ground, are repurposed in various ways to allow for different uses.

MODUS VIVENDI

STUDENT Dennis Koek

MASTER Architecture

GRADUATION DATE 22 January 2024

MENTOR Jarrik Ouburg

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Wouter Kroeze and Krijn de Koning

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Paul Kuipers and Txell Blanco Diaz

AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE Audience Award

Modus Vivendi is an architectural monument to social integration and an ode to the encounters we have lost in today’s polarised, intercultural society. It honours, facilitates and stimulates social exploration and interaction in our shared existence.

Despite the diversity of contemporary society, people often coexist passively, rarely engaging meaningfully across group lines. Rooted in the in-group

and out-group theory, many of these divisions are based on assumptions and imaginary boundaries, contributing to segregation and polarisation. This project explores the role of architecture in fostering social integration. Public architecture, it argues, should not be shaped solely by pragmatic, economic or historical considerations. Instead, it must prioritise social function and encourage spa-

tial awareness and interaction among diverse users.

Modus Vivendi refers to a way of living, a means of continuing what connects us, even when we do not share the same norms and values. Philosopher Eberhard Scheiffele’s notion of ‘making the familiar strange by studying the unknown’ underpins the design and research process.

As a monument, Modus Vivendi is both a tribute to

and a catalyst for social flexibility. Its sculptural mass and counter-mass invite movement, reflection and connection. Grounded in theories from sociology and environmental psychology, the project advocates a shift in mindset: placing social interaction at the heart of public architecture. It stands as both a spatial design and a manifesto for change.

Socioscapes.

Axonometry of the monument of social integration.

Site plan.

Sociospatial

Visualisations.

Pouring of concrete layers.

Section building physics.

Visualisations.

OFTEN YOU’RE IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

Part of the Graduation Weekend is the Kromhout Lecture, delivered by alumni of the academy. This year, architects Lorien Beijaert and Arna Mačkić of Studio LA took the stage.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photos JONATHAN ANDREW

Beijaert and Mačkić graduated from the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture in 2017 with a joint design proposal for a human rights institute on the Plein in The Hague, next to the Dutch parliament. ‘We all remember your huge model, which was exhibited in the same room where we are gathered now,’ said director Madeleine Maaskant, introducing the two architects. ‘In your work, collective dialogue plays a central role.’ At the suggestion of the curators of the Graduation Weekend, Justyna Chmielewska and Anna Zań, Beijaert and Mačkić were invited to reflect on their work over the past seven years.

‘We started studying at the Academy in 2010, during an economic crisis,’ said Mačkić. ‘We wanted to learn from people on the fringes of the profession.’ Their first collaboration was an exhibition design for the Unfair art fair in Amsterdam in 2017. That same year, they created On Speaking Terms, an exhibition installation at Nest art gallery in The Hague, incorporating a temporary semicircular auditorium that meant to promote discussion. This public dimension also characterised the Geheugenbalkon (Memory Balcony) in Groningen (2021). This temporary structure provided a vantage point over a major highway reconstruction project, as well as tiered seating for public discourse. It comprised a dismantled highway segment elevated by a bright red steel frame. Studio LA is currently working on two further art projects in Groningen, including one involving a repurposed concrete road deck elevated on two columns, situated in a park designed by wUrck landscape architects.

A poetic project, City to Dust, was created with Baukje Trenning for the 2021 International Architecture Biennale in Venice. The installation featured floor tiles prone to cracking, yet held together by a mesh underside. As visitors walked across them, they would occasionally and inadvertently break. ‘Each step confronted the visitor with their physical impact on the environment,’ said Beijaert.

Heritage and memory form another key strand of Studio LA’s work. In 2014, Beijaert and Mačkić paused their studies to engage in a project in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, centred on the town’s iconic bridge: destroyed in 1993 and rebuilt between 2001 and 2004 by Unesco, among others. Despite reconstruction, Mostar remains divided, with communities separated across the Neretva River and lacking shared spaces. Inspired by the annual diving competition held since 1566, the architects proposed a speculative design for a diving school; a shared ritual space divorced from religious or political identity. Wide steps lead to a generous platform, functioning as both diving board and communal space. ‘We presented it in Mostar,’ said Mačkić, ‘but the audience was pessimistic: “This is never going to work here.”’ However, some time later, a diving instructor constructed a new platform near the bridge, which has begun to bridge the town’s divisions.

The final project Beijaert and Mačkić presented was their design for a memorial site in Lelystad. The municipality tasked Studio LA with locating the site, engaging communities and exploring modes of commemoration. Studio LA consulted with Jewish, Christian and Muslim communities, as well as Roma and Sinti, veterans, descendants of enslaved people, queers and physically challenged individuals. They selected the Zilverparkkade and proposed a design drawing from the linear landscape of the Flevoland polder. A large, circular stage will serve as a communal space for remembrance, while smaller platforms, co-designed with each community, allow for more individual forms of commemoration.

The lecture concluded with a Q&A. One student referenced a 2017 project by Studio LA: temporary refugee housing in a repurposed prison in Amsterdam. He asked how young designers should respond to today’s political climate, particularly bleak in the days following the 2024 United States presidential election. ‘You have to start somewhere,’ replied Beijaert. ‘Even if you can only make a very small difference.’ When the prison was converted, the window bars were left intact, creating a hostile environment for refugees. When Studio LA questioned this, a representative of the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) claimed the bars improved indoor climate because they allowed for shade. Beijaert recounted: ‘The former prison director told us that that was nonsense.’ Following this, COA denied them further access. Studio LA raised the issue publicly, including at De Balie cultural centre. Weeks later, seven parliamentary questions were posed on the topic. A populist rightwing MP reiterated the claim that the bars were for shade. Seven years on, COA has approached Studio LA once again; this time with a commission to design two refugee housing complexes. ‘Often you’re in for the long haul,’ said Beijaert. ‘Have stamina and hold on to your ideas.’ ←

Lorien Beijaert and Arna Mačkić delivered the Kromhout Lecture 2024.

Each academic year begins with a special welcome: the start workshop, a three-day event that immerses first-year students in the academy’s atmosphere. This year, the workshop concluded with a lecture by London-based activist and architecture journalist Phineas Harper.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photos MILDRED ZOMERDIJK

DRAWING LINES

From the moment the doors opened on Wednesday morning, the academy buzzed with energy. First-year students were greeted with an informative tour and introductions to the library, workshops and other facilities. In small rotating groups, students explored the model workshop, met staff and received their goodie bags: a cheerful gesture marking the start of their academic lives.

After a short walk, lunch at the MakerSpace provided a setting for conversation and connection. The afternoon was devoted to a reflective session about the balance between work, study and private life, exploring intercultural dynamics and personal ambitions. This served as a reminder that the spatial design disciplines are shaped not only by skill but also by identity and context. Thursday shifted gears with the workshop theme ‘from city to landscape’. Through sketching, walking and a boat trip, students explored spatial relationships across Amsterdam, guided by academy alumni Roy Damen and Alice Dicker. They encouraged observation and curiosity.

The workshop concluded on Friday with a presentation of the students’ drawings. Before this, they listened to a number of speakers in the Dokzaal, a former church hall near the Academy of Architecture. The heads of the master's courses in architecture, urbanism and landscape architecture (Janna Bystrykh, Anna Gasco and Joost Emmerik respectively) offered insights into the structure of the curriculum. London-based activist and architecture journalist Phineas Harper gave a lecture on how spatial designers can establish a socially engaged practice. The event ended with drinks, offering a moment for reflecting on first impressions and new friendships. ←

The students’ drawings were exhibited in the academy.

BIRD BOX

For the V1b Form Studies course Technical Matter, students constructed a bird hide on the island of Texel with the help of a robot.

Text BENGÜSU HOŞAFCI EN MARLIES BOTERMAN Photos RAYMOND ASTUDILLO

VAN EIJK

Waddenpolder Waalenburg at Texel is the first and largest meadow bird reserve in the Netherlands. You can experience wide skies along winding creeks that date back to the time when the sea still had free rein here. The open landscape, with characteristic meadow mills on the horizon, offers a glimpse of what every polder in the Netherlands once looked like.

However, the number of meadow birds has been declining at an alarming rate for decades. Ongoing intensive and fragmented land use in rural areas has led to a drastic shortage of suitable habitats. To address this issue and facilitate the study of these birds while minimising disturbance, we initiated a collaboration with Natuurmonumenten at this location. The result: a bird hide designed to prioritise both birdwatching and ecological research.

The Amsterdam Academy of Architecture and Robotlab at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences collaborated to explore how different institutions can benefit from each other’s expertise and exchange knowledge. Students began by observing bird movements in Waddenpolder and translating these behaviours into digital data. Using advanced software such as Rhino and Grasshopper, they created a parametric design that mirrored these movements.

For the construction, we used 486 identical components of 45x45x600 mm thermally modified pine, with all ends cut at a 45-degree angle to emphasise the direction of the installation and provide unobstructed views of the landscape and birds.

Grasshopper enabled robots to efficiently stack the pine for the installation. These robots calculated the number of pieces and assembly points, streamlining the construction process. This robotic integration also offered flexibility, allowing students to experiment with dimensions, piece counts and, most importantly, the overall form of the bird hide. The iterative design process involved numerous trials to achieve a stable structure suited to the location. However, Grasshopper offers a multitude of design possibilities, presenting the challenge of refining these into a cohesive structure that responds to the environmental context and the needs of both birds and visitors.

The entire installation was divided into seventeen sections to allow for pre-assembly and transport from Robotlab to Texel. Construction began with laying the foundation, where wooden poles were hammered into the ground to ensure stability. This created a solid base for the installation. Once the foundation was secure, the first layer was placed and connected to the poles, establishing the framework. Additional sections were then added, interlocking to ensure alignment and cohesion. This method ensured that the final design not only met structural requirements but also harmonised with the surrounding landscape. Throughout the process, balancing functionality and aesthetic quality was essential, resulting in a harmonious addition to the natural environment.←

With thanks to Robotlab at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (Marta Male-Alemany, Marco Gali, Zach Mellas, Timo Bega) and Natuurmonumenten (Lea van der Zee, Eckard Boot, Jerome van Abbevé and Duurt Holman).

JUSTICE BY DESIGN

The Winter School explored the agency of radical design in the pursuit of spatial justice.

Text

IRENE LUQUE MARTIN AND JOHNATHAN SUBENDRAN

Photos JONATHAN ANDREW AND GREG JENNIE

In the face of climate emergencies, socio-political unrest and a growing global wealth gap, spatial design plays a crucial role in offering integrated perspectives to address these overlapping crises both in the present and the past.1 The spaces we design are more than physical interventions; they are socio-political acts that can either reinforce injustice or foster more equitable outcomes.2 This highlights the responsibility and accountability designers must acknowledge, as design decisions shape whose voices are included and which forms of knowledge are prioritised.3

Contrary to the conventional approach in mainstream design education, which often emphasises the heroic role of the designer and a bias toward quick solutions for complex societal problems, the 2025 Winter School built on the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture’s diverse, multidisciplinary framework. It encouraged students to critically engage with the agency of design in confronting escalating social, spatial and environmental injustices. In doing so, students strengthened their multidisciplinary skills, exploring alternative methods and roles better to address the diverse and complex realities of the world today.

Design education in Western Europe, whether in academic institutions or other professional settings, is often grounded in specific values such as democracy. As in any discipline, the values we uphold shape how we operate, whether professionally, domestically or publicly. In design, we have normalised the practice of upholding democratic values because our institutional, political and social environments allow us to.4 However, the reality is that democracy is faltering in many states, both in the Global North and South. We are witnessing this now in the Netherlands with increasing anti-immigration policies, with more than half-century military occupation of the West Bank in occupied Palestine, and ongoing denial of ancestral indigenous people’s land in Canada. Designing under the assumption of a democratic context where everyone has the right to participate, speak and think freely will render us increasingly irrelevant and isolated if we aim to make a meaningful impact in diverse contexts and conditions. This realisation calls for a fundamental shift to diversify our design practices, methods and discourses.

Irene Luque Martin introduces the final conversation in the Dokzaal, a former church close to the academy.

The Winter School was not merely an academic exercise; it was a transformative journey. It was designed to critically explore the agency of design in the pursuit of spatial justice across diverse political, ecological and cultural contexts. Through an intensive examination of cases where injustice or democratic breakdown has occurred, students engaged in debates and discussions to challenge the role and position of spatial design in these conditions. These discussions explored both human and non-human perspectives. From this critical foundation, students embarked on a journey of radical spatial imagination, using design as a tool to resist unjust realities and envision spatial justice. The ultimate aim was to foster a comprehensive understanding of spatial justice through alternative design practices and methods, culminating in an open debate to reflect on the role of spatial design education and practice in creating more just futures. Despite thematic alignments and the need to drive our practice in a more contextualised manner, the Winter School focused on a dual approach. First, we developed a language based on ‘attitudes’ as a way to explore the values, practices, skills and approaches connected to different ways of being and doing. When discussing justice, there is often designer paralysis: designers feel they have no voice or agency in the realm of justice. However, our attitude – shaped and transformed by every decision and thought – defines how we approach our practice. This attitude inherently influences our approach to design, grounded in our educational foundations. The idea that designers should adopt a single attitude (e.g. the hero, the sculptor, the star) is perpetuated by mainstream professional practices, reinforcing power dynamics and colonial structures in contemporary design. Justice by design is a transformative journey to explore and understand alternative attitudes that counteract mainstream practices. It is, and remains, a call to embrace plurality in our ways of working, and to recognise how doing ‘otherwise’ can become a powerful tool for an uncertain future.

Second, the programme focused on contextualising justice, not as a fixed goal but as a lens through which we operate. The Winter School was organised into five case-based studios and one integrative studio. The five case-based studios addressed various unjust realities around the world, serving as the foundation for the students’ imaginative work. The integrative studio was reflective, aiming to develop a critical perspective on the agency of design in pursuing spatial justice, drawing insights from the five case-based studios.

A TRANSFORMATIVE JOURNEY

Justice by design was never about arriving at definitive answers, but about embarking on a collective journey; one rooted in process rather than outcomes. It was an invitation to unlearn, to build conscious awareness and to simply begin from where each participant stood. From the very first moment, students were encouraged to bring their full selves into the space, acknowledging the richness of diverse starting points, attitudes and ways of knowing.

The Winter School became a space for deep introspection, a critical pause to reflect on the designer within. Participants were invited to explore how they project themselves into their work and into the world, making visible the intimate connections between identity, values and design practice. A central thread throughout this journey was the question of positionality. Students were challenged to reflect on how their identities, privileges and perspectives influence the design process and how power shows up not just in the world they engage with, but within themselves.

As the days unfolded, this introspective process took different shapes and tempos. Each participant became an active agent in their own becoming, navigating through layers of self-awareness and shifting perspectives. Attitudes began to surface, not only as abstract concepts, but as embodied roles to embrace, challenge or transform. Some found resonance in the attitude of the hacker, others in the journalist, the exposer, or even in entirely new archetypes born from their own experience. →

Johnathan Subendran was one of the two artists-in-residence of the Winter School 2025.

Caroline Newton taught studio 2, titled Enacting Matriarchal Patterns, with Amber Coppens.

By engaging in alternative methods (performance, singing, storytelling, gaming) students stepped into unfamiliar terrains of inquiry. These creative practices offered new openings to question design ethics, explore values and reimagine the agency of design beyond conventional frameworks. Freed from preconceived assumptions, they were able to confront the injustices they sought to address with fresh eyes and renewed clarity.

This Winter School did not offer a singular path forward. Instead, it offered space to ask different questions, embody different attitudes and make space for different ways of becoming designers in and for justice.

A NEW LANGUAGE

STUDIO 1 JUSTICE BY DESIGN: A CONSTELLATION OF ATTITUDES

TUTORS: IRENE LUQUE MARTIN & JOHNATHAN SUBENDRAN

This studio explored the agency of designer attitudes through critical reflexivity across five case-based studios. Participants engaged in a journey to examine the values, methods and practices that shape these attitudes, drawing from past, present and future possibilities. In three key roles (journalists, researchers and composers), they investigated the evolution of design attitudes, conducted interviews and fieldwork, and created a visual narrative to communicate their findings. The studio integrated these insights into a conceptual framework, illustrating how diverse designer attitudes contribute to advancing justice by design. This process fostered an understanding of how attitudes relate and manifest.

Skills: Critical reflexivity and reflection Attitudes: The reflector and the exposer

STUDIO 2

For many students, the themes explored during the Winter School were entirely new. Questions of justice, ethics, positionality, values and attitudes were unfamiliar and understandably overwhelming. Some felt paralysed or disconnected, uncertain if they were even ‘qualified’ to engage with such weighty injustices. But rather than shying away, the studio embraced these tensions. Through the lens of attitudes and values, students began to see how they could meaningfully engage with complex topics. The key was to individualise the conversation, meeting each participant where they stood and recognising that there is no singular way to understand or relate to justice. Too often, conversations about justice assume a shared vocabulary or common ground. This Winter School challenged that assumption, creating a space where difference was not only acknowledged but welcomed. Through collective dialogue and peer exchange, students realised that injustice isn’t abstract or distant. On the contrary: it often shows up in their daily lives, in how people are treated, how spaces feel or how design decisions are made. They redefined justice on their own terms, whether in feeling unsafe on a street corner or being treated unfairly at work. They also began to dismantle the stigma around the word ‘radical’, recognising it not as extreme, but as a return to the root. Ultimately, students left better equipped to carry justice-oriented values, such as care, respect and equity, into their work. From a curator’s perspective, introducing this new language has been one of the most powerful and transformative aspects of the Winter School.

ENACTING MATRIARCHAL PATTERNS: UNLOCKING THE RADICAL IMAGINARY TUTORS: CAROLINE NEWTON AND AMBER COPPENS

In this studio, participants explored matriarchal patterns of liberation in contrast to colonial and patriarchal oppression. Through theatrical performance and the concept of mind-body-territory, they engaged with the radical imaginaries and decolonial struggles of the Sahrawi people. Focusing on enactment over embodiment, the workshop connected spatial dynamics with personal and collective experiences to foster inclusive, community-driven design practices. Participants reinterpreted and reimagined these patterns through physical, emotional and reflective processes, delving into spatial justice issues. Outputs included a screenplay of performances, visual documentation and reflective writings, promoting an understanding of matriarchal resilience in spatial planning.

Skills: Enactment and performative exploration of spatial concepts, critical reflection, visual documentation and drawing the radical imaginary Attitude: The activator

STUDIO 3

UNTOLD: COUNTER-NARRATIVES OF UNDOING

TUTORS: LUISA MARIA CALABRESE AND RAQUEL HADRICH

This studio examined socio-environmental injustices in land reclamation, focusing on Manila Bay, where socalled ‘green’ developments displace communities and ecosystems. It challenged the designer’s complicity in perpetuating inequity, dismantling the myth of Dutch land reclamation expertise as a universal solution. Rooted in ‘undoing’, the studio deconstructed dominant narratives and confronted designer neutrality. The focus

was on movement improvisation and choreography, allowing students to engage with conflict and injustice through embodied strategies. Speculative mapping was used to challenge power structures, and the final outcome, in the form of a multimedia installation, presented counter-narratives that provoke critical engagement with accepted ‘truths’ in the built environment.

Skills: Movement improvisation and choreography

Attitude: The hacker

STUDIO 4

THE PALESTINE THAT IS IN THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE CAMP: STORYTELLING AS A TOOL OF IMAGINING LIBERATED FUTURES

TUTOR: NAMA’A QUDAH

In this studio, participants used storytelling as a critical tool to re-examine Palestine and Palestinian refugee camps, particularly in the context of the ongoing Israeli war on Gaza. By combining academic research and film, the studio interrogated colonial knowledge production and explored pathways to reclaim justice for Palestine. Participants challenged fragmented narratives about Palestine’s geography and global perceptions, envisioning liberated futures beyond colonial borders. Through storytelling, they explored the temporal and spatial layers of Palestinian refugee camps since Al Nakba (1948), reflecting on how these intertwined histories shape the realities and possibilities of Palestinian life today.

Skills: Storytelling

Attitude: The exposer to confront

STUDIO 5

A PLAY FOR SPACE AND JUSTICE: SHADOWS OF CENTRAL PARK IN SHANGHAI

TUTORS: CHUN HOI HUI, JAMMY ZHU AND YANG ZHANG (SPRING ONION ATELIER)

Lujiazui Central Park, located in Shanghai’s iconic CBD, contrasts lush landscapes with a skyline symbolising China’s economic rise. Yet, its gated access, surveillance and exclusive events reflect a governance model prioritising authority and exclusivity over equitable urban access. This studio challenged these norms by transforming the park into an experimental space for rethinking spatial justice. Through role-play and urban games, students used participatory methods to reimagine the park’s design and governance, shifting from top-down control to inclusive, bottom-up processes. The studio explored governance, social equity and sustainability, uncovering the roots of spatial injustice and inspiring new conversations on public space.

Skills: Urban gaming

Attitude: The gamer

STUDIO 6

SINGING A LAND INTO BEING: RADICAL REIMAGINING OF LAND–BODY RELATIONS THROUGH COLLECTIVE SINGING AND DIGITAL LANDSCAPES

TUTORS: AGAT SHARMA AND LAURA CULL Ó MAOILEARCA

In this workshop, participants enacted scenes from an unfinished script by Dr Dhvani Shodhak, a glottogeologist and theatre-maker. The script, divided into five scenes, explored land–body relations observed on cotton farms in India, highlighting issues such as agrochemical exposure, cancer, contamination and farmer suicides. Each scene consisted of three sections: entering a collective dream space, improvisational singing and creating digital walkthroughs of imagined landscapes. Participants used collective dreaming as a tool for radical imagination and practised embodying and representing landscapes sonically and digitally, exploring the socio-environmental conditions affecting farmers’ lives in India.

Skills: Improvised singing and applying Unreal Editor for Fortnite

Attitude: The realiser