Restoring the connection to the Cromarty Firth

Laura Kragten laurakragten@gmail.com

European Master in Landscape Architecture (EMiLA) Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

Graduation committee:

Yttje Feddes Mentor

Ziega van den Berk Committee member

Dingeman Deijs Committee member

Members of the exam committee:

Roel Wolters

Brigitta van Weeren

Date: 26 May 2025

© Laura Kragten

Gegrepen door de bijnaam “oil rig graveyard” werd mijn interesse gewekt om de Cromarty Firth regio te ontdekken. Een gebied waar water en land elkaar ontmoeten in het noordoosten van Schotland.

Mijn interesse voor een opgave in Schotland combineerde zich met de wens om een project vanuit een plek te starten en niet vanuit een probleem.

De Cromarty Firth is een zij arm van de Moray Firth met door de gletsjer gevormde diepe, beschutte wateren. Door de eeuwen heen hebben mensen zich gevestigd op de glooiende helling naast de Cromarty Firth. Deze regio heeft verschillende identiteiten en ingrijpende transformaties gekend. Ooit was dit een lokaal agrarisch gebied met crofting tradities, dat door de globale industrialisatie in de luwte is geraakt. Fascinerend is het huidige contrast tussen de natuurlijke condities en de olieboorplatforms die geparkeerd zijn in het water van de Firth. Hierdoor begon ik me af te vragen; wat is de identiteit van deze plek en hoe zal die zich ontwikkelen in een postolie tijdperk?

Om de genius loci van de plek te ontdekken en te ontmoeten was een onderdompeling van piek tot kustlijn in het gebied cruciaal. Mijn reis toonde een gelaagd landschap dat gevormd is door de geologie, geschiedenis en menselijke ingrepen. Relicten van verschillende tijdslagen zijn her en der zichtbaar. De zachtheid van de rivier begeleidende bossen, vergezichten over het landschap door de natuurlijke hoogte en de luwte van het gebied staan in contrast

met de hardheid van de grootschaligheid en industrie. De gradiënt in het landschap wordt verstoord door barrières die het gebied doorkruisen. Industrialisatie heeft het water verstijfd en de sociale connectie vertroebeld. Niet langer is de gemeenschap emotioneel en fysiek verbonden met het water. Het contact met de Firth is verloren. Het water van de Firth is in de vergetelheid geraakt.

Uit mijn veldonderzoeken ontstond het projectdoel: het herstellen en activeren van de fysieke en emotionele relatie tussen mens en de Firth. Om zo een nieuwe identiteit creëren voor de postolie toekomst. Waar land en water elkaar ontmoeten ontstaan nieuwe relaties.

Crofting vormt de basis voor de hernieuwde verbinding met het water en het lokale landschap. Door dit kleinschalig gemeenschappelijk landbouwsysteem, wat diepgeworteld is in de Schotse Hoogland cultuur, te interpreteren worden de verloren relaties hersteld. Kleine crofts en gemeenschappelijke commons vormen de basis van een divers en verbonden landschap waarbij de natuur en de gemeenschap worden herontdekt.

Met dit project ontwikkelt de Cromarty Firth haar nieuwe genius loci. Fysieke en emotionele banden worden gevormd door herinterpretatie van relicten uit het omliggende landschap. De Cromarty Firth ademt weer, niet langer de stille achterkant, maar als kloppend hart van de gemeenschap.

My graduation starts with a place, not a problem.

Intrigued by its nickname ‘the oil rig graveyard’, my curiosity was drawn to explore the Cromarty Firth region. A region where land and water meet in the Northeast of Scotland.

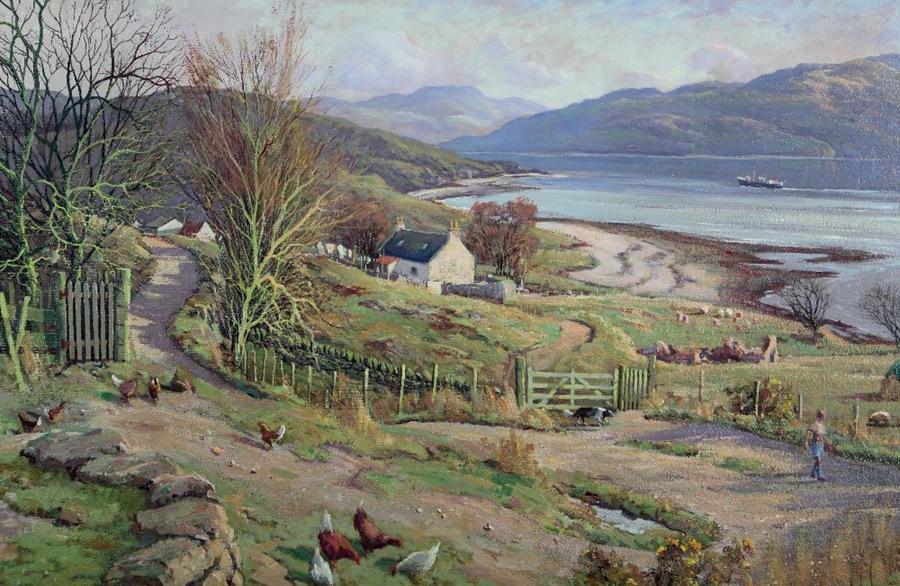

The glacially shaped, deep and sheltered waters of the Cromarty Firth flow to the neighbouring Moray Firth. Over time people have settled on the gentle slopes next to the Cromarty Firth. Historically, this region has known different identities and significant transformations. Once a local agricultural landscape with crofting traditions, has faded due to global industrial expansion. The current contrast between the natural conditions and the towering oil rigs over the waters of the firth is fascinating. It made me wonder: what is the identity of this place and what will the genius loci of this area become once the oil era ends?

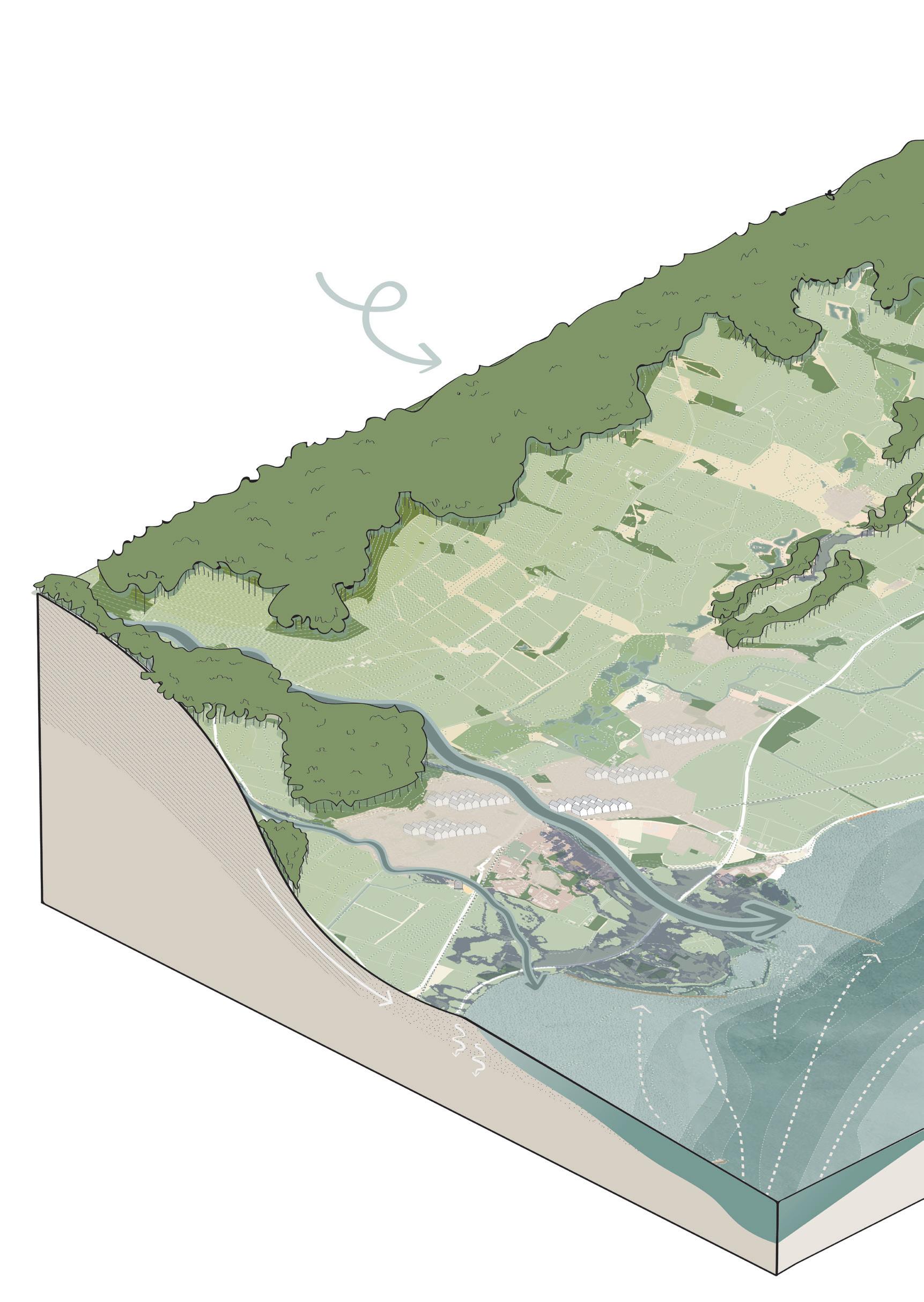

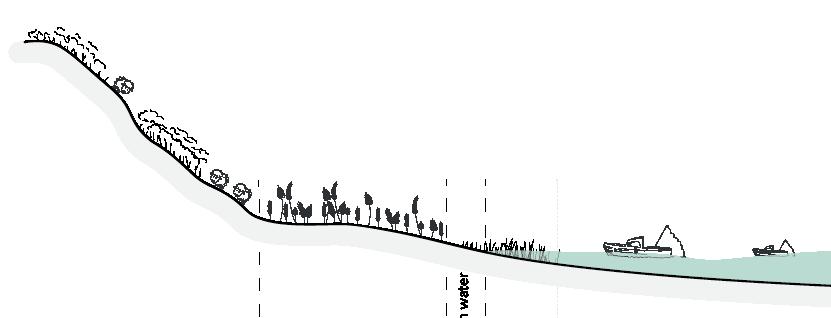

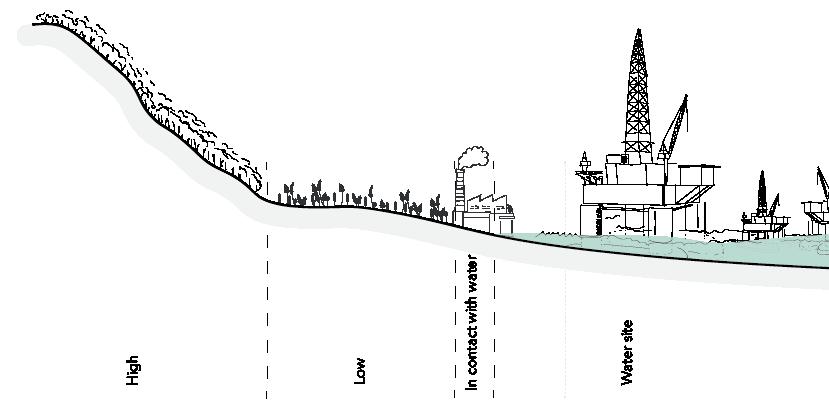

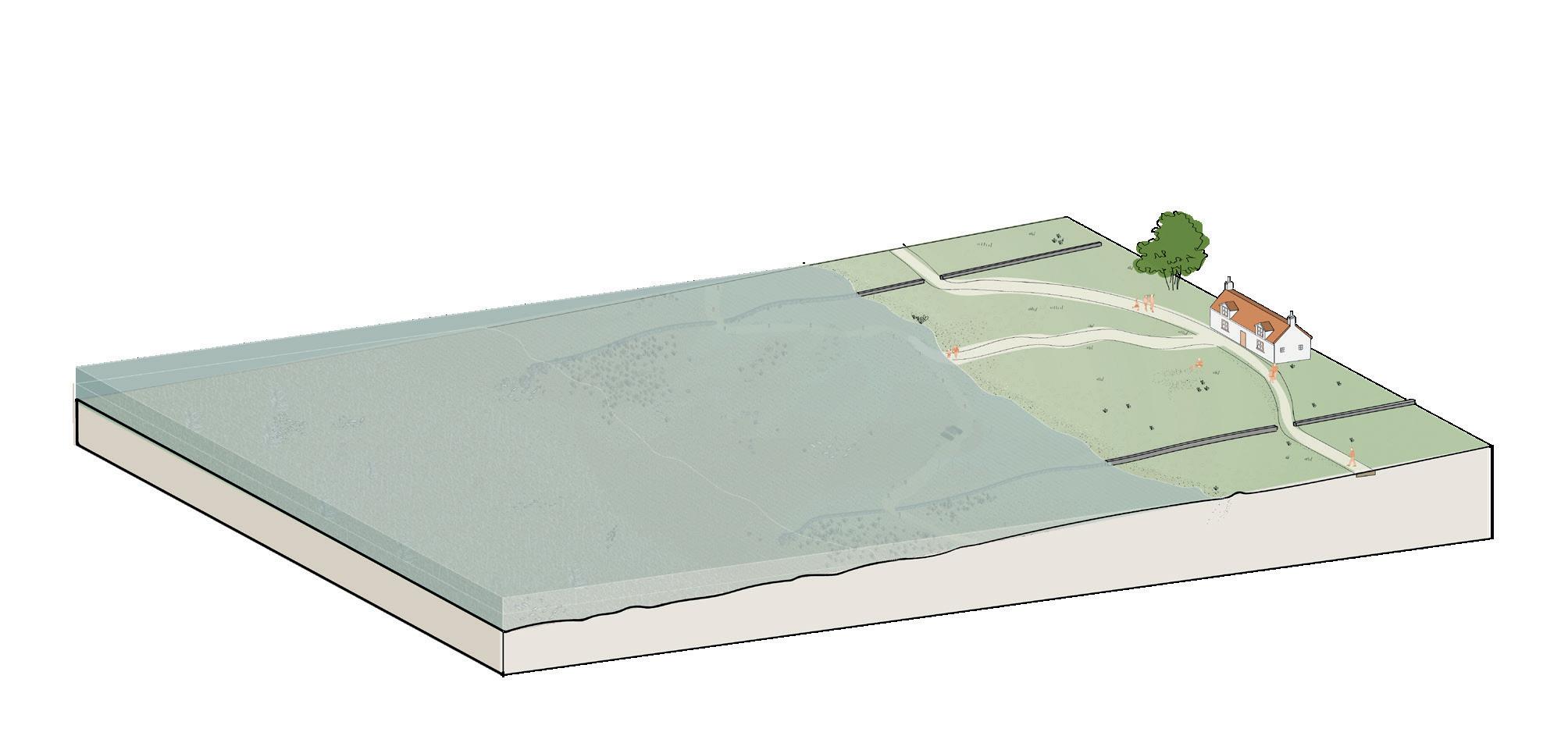

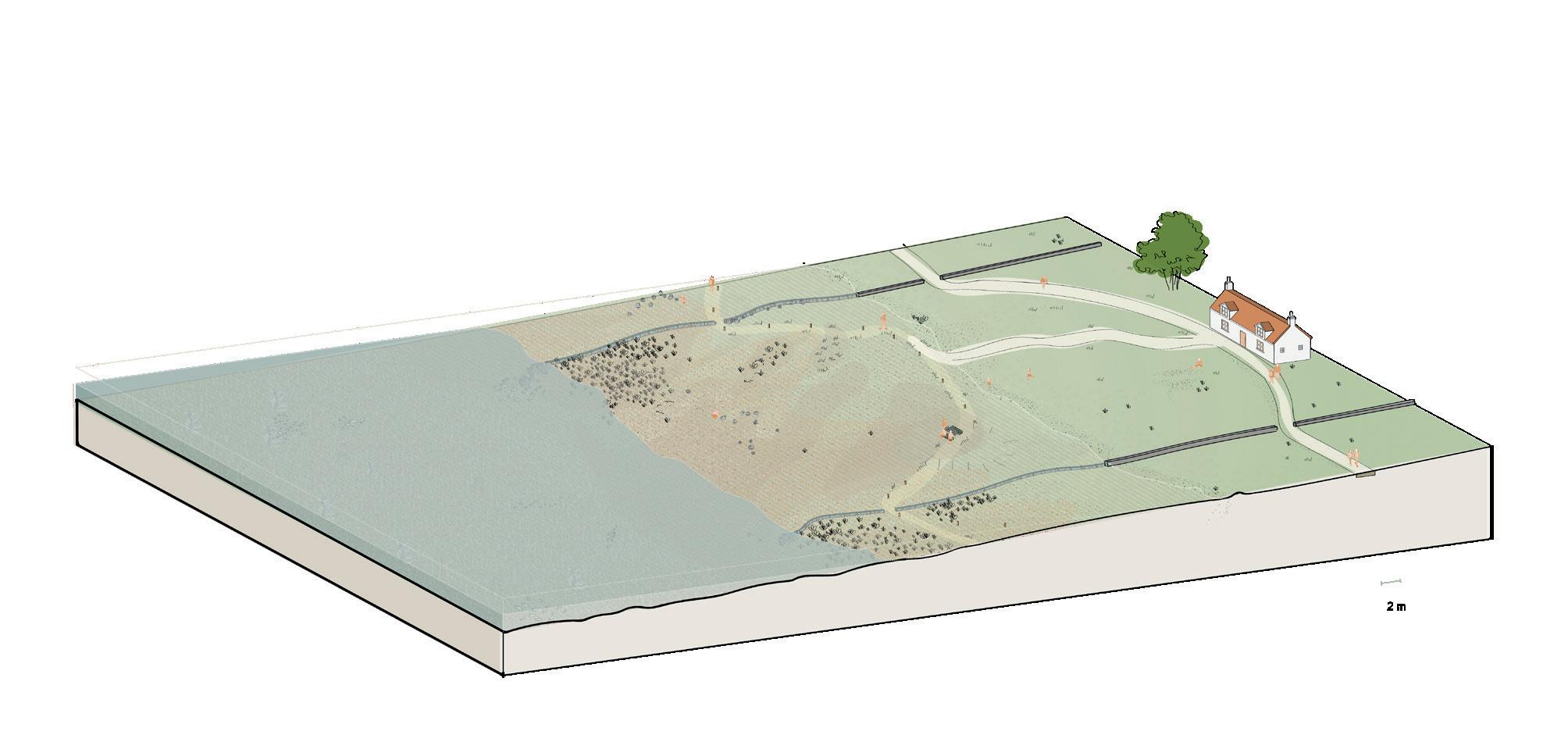

To discover and encounter the genius loci, a full immersion from peak to edge was essential. My journey from the top of the Highlands to the water of the firth revealed a layered landscape: one shaped by forces of nature, history, and human ambitions. Relicts of all those layers are still traceable. The landscape shows a gradient from peak to edge, but is disturbed by barriers that cut across the area. Industrialisation has stiffened the

waters and blurred the social connection. The people and water of firth are not physical and emotional tied together anymore. The waters of the Cromarty Firth are slowly forgotten.

Out of those fieldtrips, the project goal emerged: to restore and revitalise the physical and emotional relationship between the people and the firth, thereby creating a new identity in the post-oil future. Where the water and the land meet, new relationships will be woven.

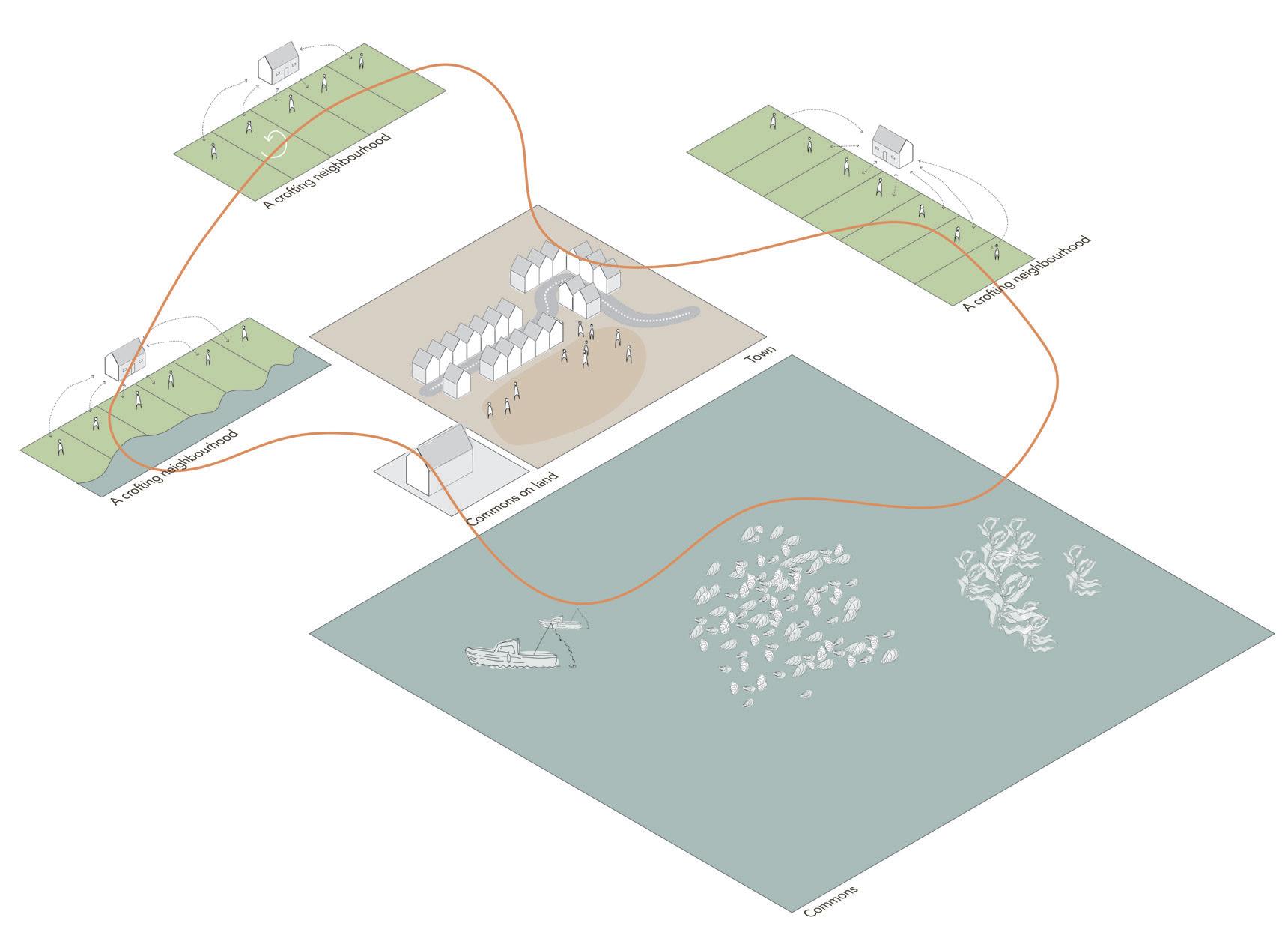

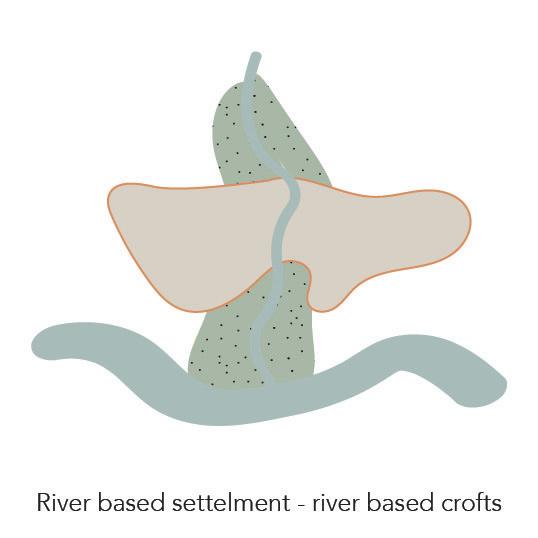

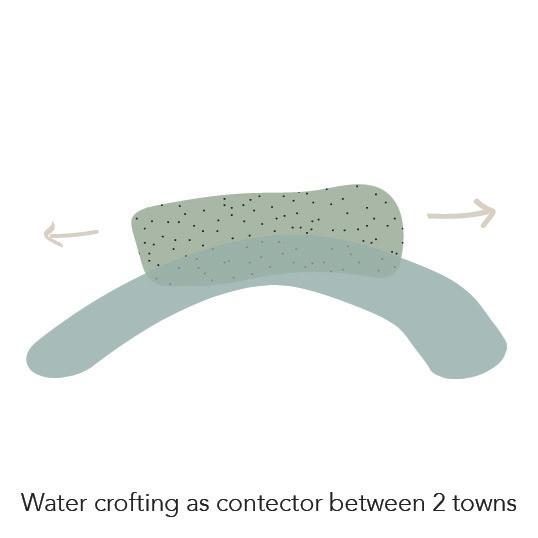

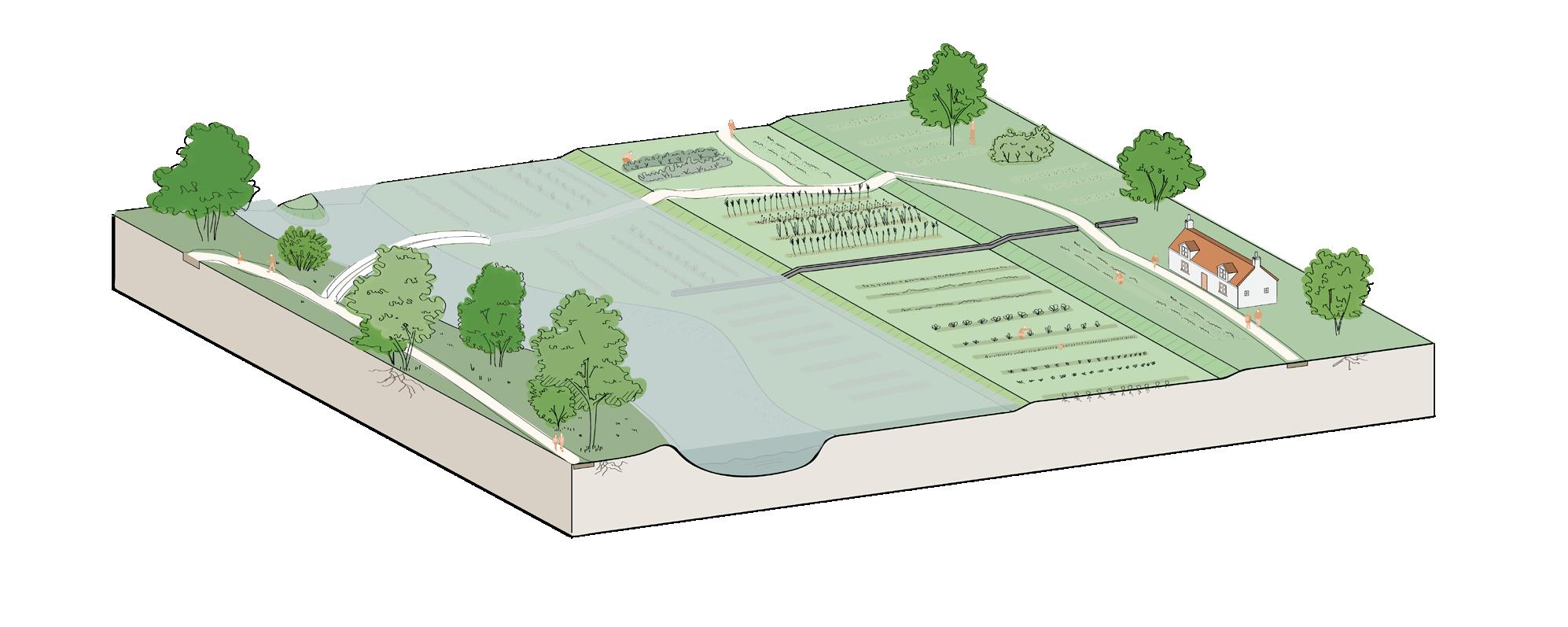

Crofting forms the foundation for how this reconnection with water and the local landscape will unfold. This typical Scottish small-scale communal agricultural system, is adapted to the Cromarty Firth. Small crofts and commons form the base of a new diverse connected landscape. The lost relationship between the villages and the water will be rewoven, allowing nature and community to rediscover one another with a cycle of connection and growth.

With this project, The Cromarty Firth is forming a new identity. Physical and emotional ties are being restored by giving new life to relics from the surrounding landscape. The Cromarty Firth will breathe again. Not as the silent backwater anymore, but as the beating heart of the community.

Fascination for the chosen location

My graduation starts with a place, not a problem.

Sometimes, we forget to truly immerse ourselves in a place and experience the unique elements.. With this graduation, I aim to demonstrate that landscape architecture is more than solving big climate problems. It involves listening to and engaging with a site to understand its true needs, instead of starting with a problem or a specific subject. In order to do this I searched for an inspiring and fascination location. The project’s goal will emerge from the exploration and the challenges I will encounter.

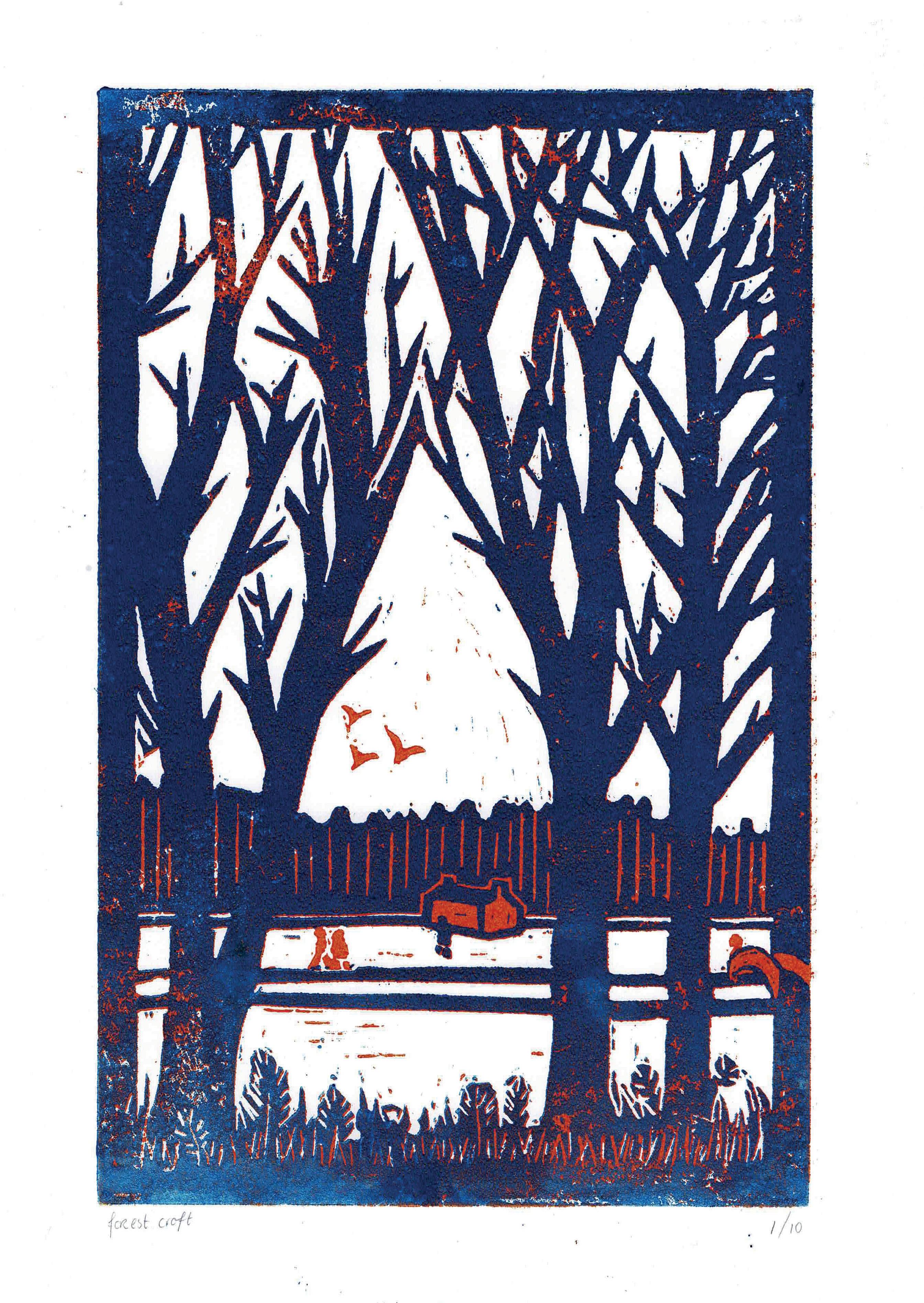

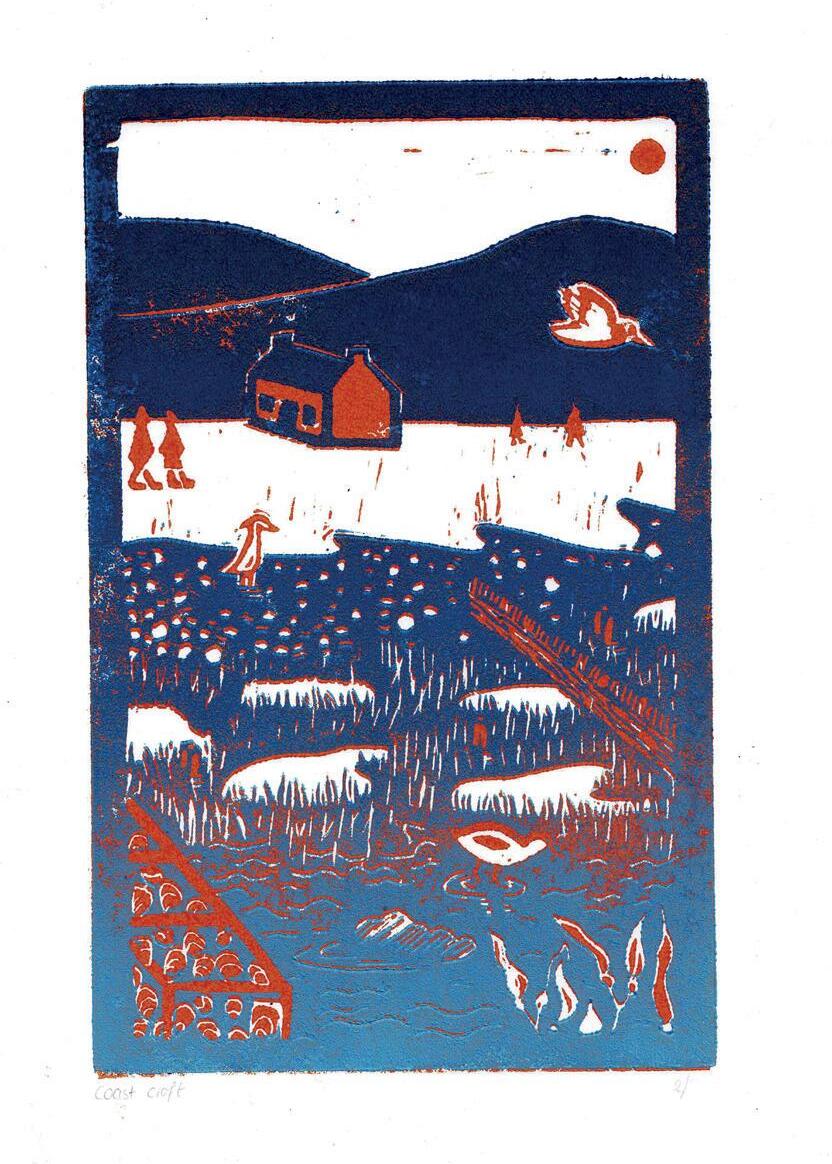

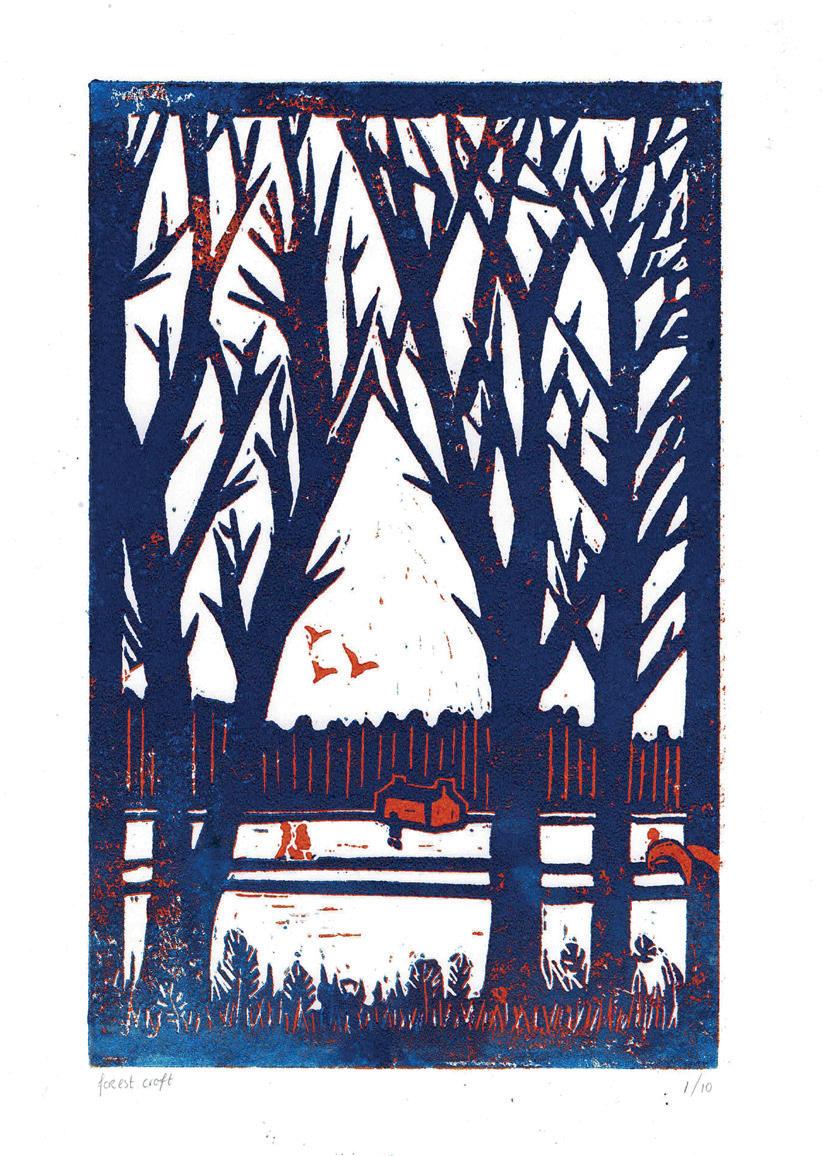

My fascination for the Cromarty Firth area began by the contrast I saw. The friction of the place made it feel different from the Scotland I knew. During my academic career I have studied abroad with the EMiLA (European Masters in Landscape Architecture) program. In Scotland I had to opportunity to study at the University of Edinburgh. The landscape and in situ printmaking, as another way of understanding a site, inspired me. Nevertheless, I never had a design project in Scotland and this graduation project was the perfect time to make that wish come true.

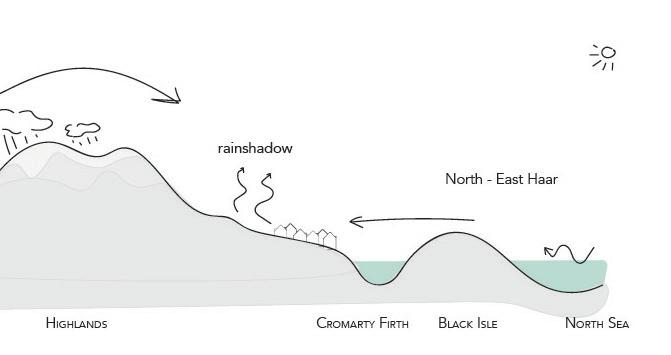

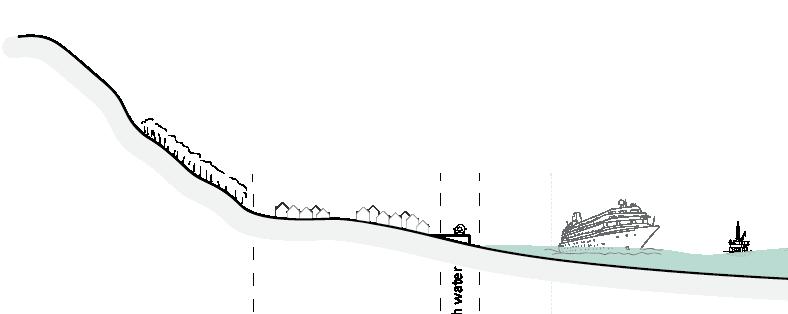

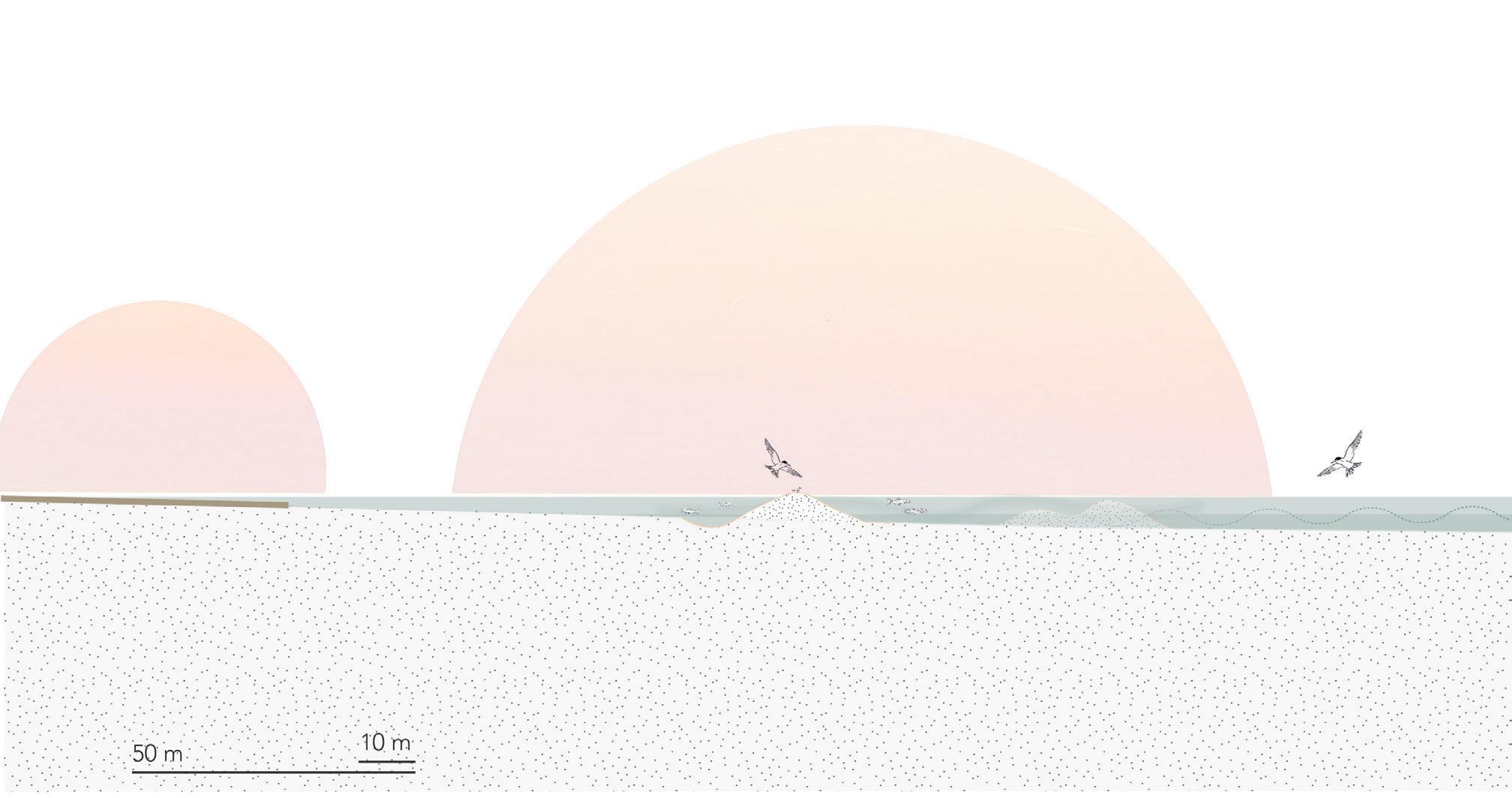

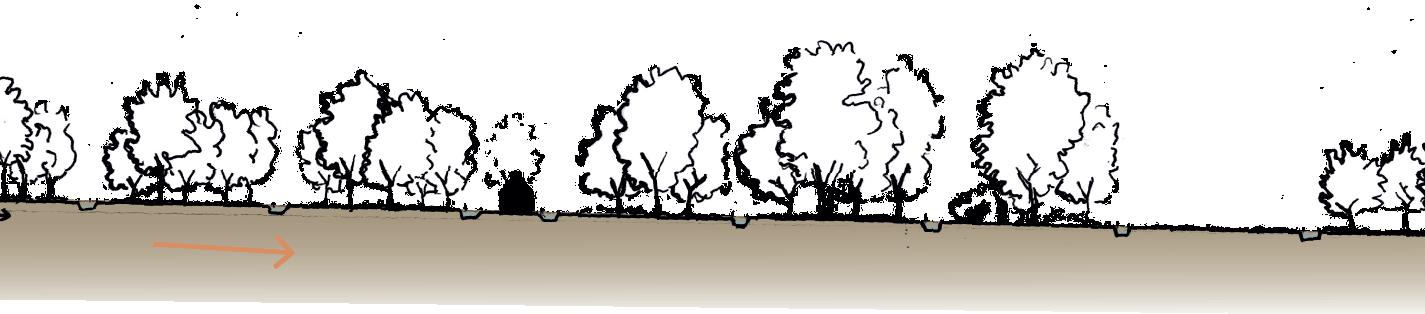

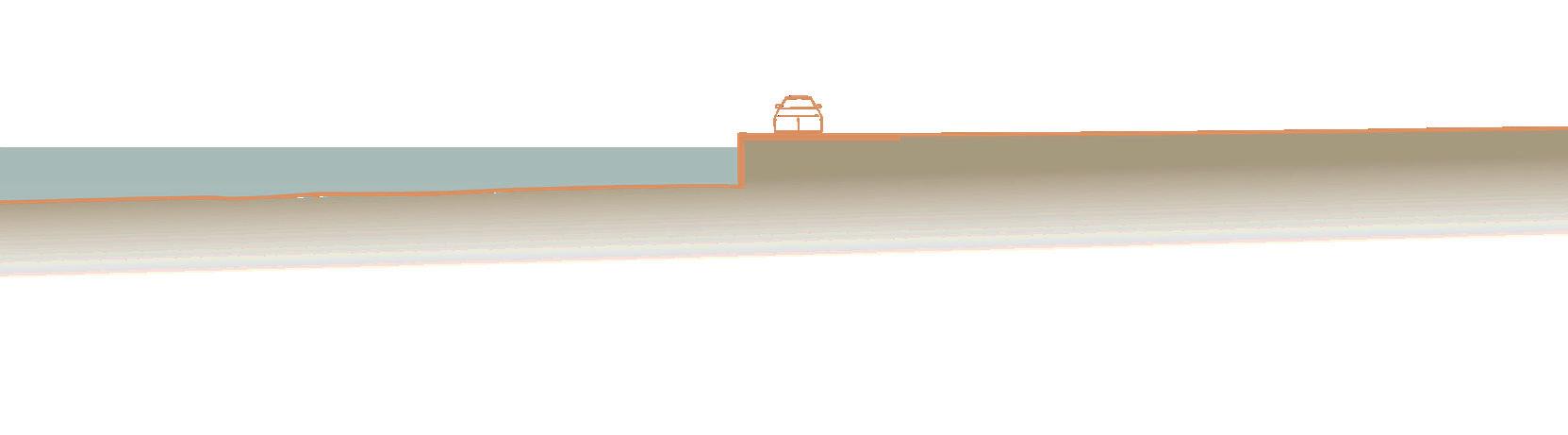

Img. 2. Principle cross-section of the sheltered position of the Cromarty Firth on the eastern side of the Highlands

The Cromarty Firth, a sidearm of the Moray Firth in northeast Scotland, immediately captured my attention with its friction and contradictions. Shimmering in the water, various oil rigs standing tall on the horizon. Wherever you look, they cannot been unseen. Behind the décor of the industry is a history full of stories from the Highlands.

As we contemplate the future, there are various possible directions. One path leads towards further global industrialisation, which will ultimately deplete the Earth of its natural resources. While another ideology brings us back to a deeper connection with the rhythms of the Earth—a way of living where people are once again in harmony with their surroundings and where local communities play a central role. In this graduation work, I envision a post-oil era in which humanity reconnects with its environment.

The presence of those industrial giants casting shadows over the landscape, made me wonder: what will the identity of the Cromarty Firth become once the oil era fades into history?

My exploration of this question began with firsthand site visits, supported by literature and data. During those site visits, I discovered through drawing, prints and recordings. Walking through the area, speaking with local residents, and immersing myself in their narratives

deepened my understanding of Cromarty Firth. Their voices, combined with my own observations, shaped the story of Cromarty Firth as I know it. This project looks into the next chapter of this region, envisioning a new phase after the oil era

2 km

A scenic walk from peak to edge to immerge into the landscape around the Cromarty Firth

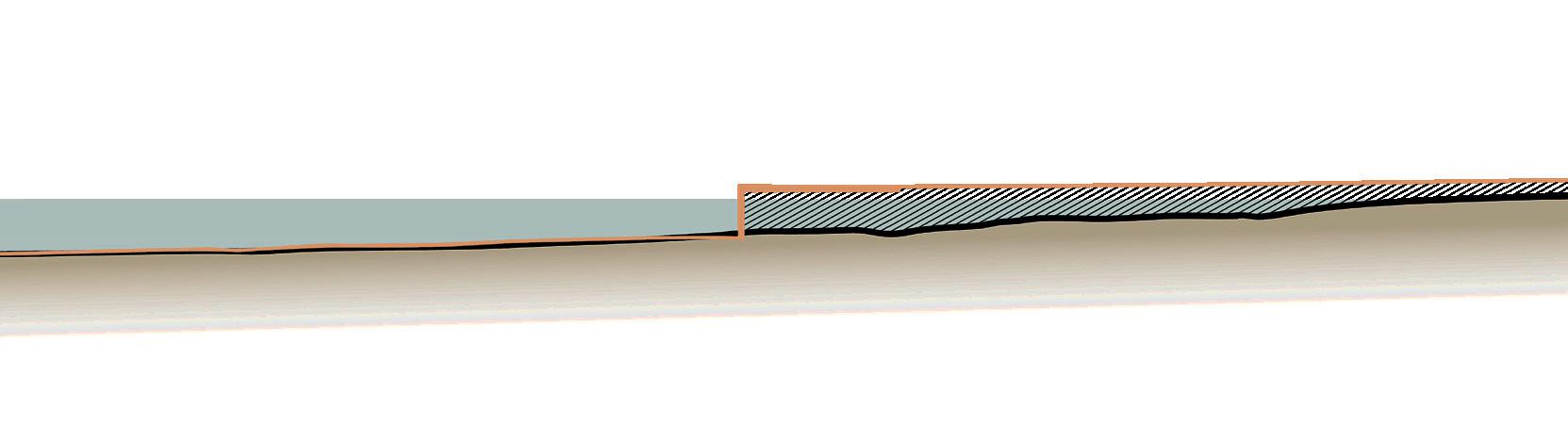

During my site visits, I observed the underlying gradient of the landscape, with its natural contours shaping the terrain beneath my feet. Yet, barriers— both physical and emotional—cut through the landscape, disrupting its continuity. The tidal zones, once intimately tied to the land, now feel distant and severed from their original connection. Scattered relicts from a time when the relationship with the land was stronger are now overshadowed by the imposing presence of the oil rigs.

8. Collection of observations during fieldtrips: pictures, drawings, paintings, water prints and magnifying glass studies (May & October 2024)

Standing on the peaks of the highlands, the wind rushes past you in an open and robust landscape. The clouds hide and reveal the peaks, traveling along on this high altitude. This combination of elevation and persistent winds contributes to the region’s harsh environmental conditions, defining a mountainous landscape that is typical for the Highlands’ distinct topography. The tops of the Scottish Highlands are characterized by their elevated, rugged terrain.

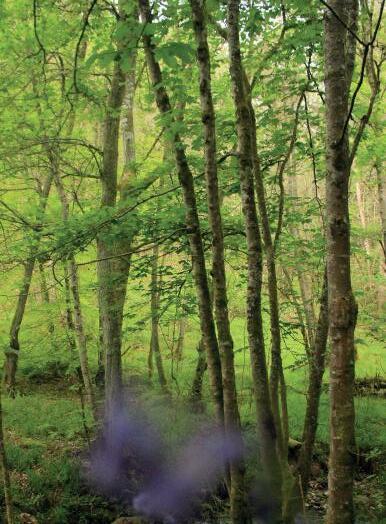

As the heights descend, the roughness softens, giving way to broadleaf woodlands to inhabit the western slopes overlooking the Cromarty Firth. The broadleaves woodlands form a peaceful and robust structure in the landscape.

Img. 11. Woodlands overlooking the Firth (October 2024)

Img. 12. Woodlands (May, 2024)

Img. 13. Woodlands (October, 2024)

The Black Isle Water of the Cromarty Firth

Vistas emerge as the broadleaf forest opens up towards the firth. Offering clear views of the lower part where where the peak transfers to the edge. The beauty of elevation is that it reveals the diverse landscape below and the perspectives it offers. From this view, the landscape gradient becomes clear along with the barriers that cut through it. Looking down from the vistas, there is more to explore.

Where the land levels out, the emotional connection to it seems to vanish. The relative sunny side of gentle slope are the home to tree crops: rapeseed, wheat and barley. The little variation in crops form a monotonous landscape which is susceptible to flooding due to its flat expanse.

Img. 15. Agricultural field (October, 2024)

Img. 16. Agricultural field (October, 2024)

Img. 17. the Scottish Ploughing Championships (October, 2024)

Forest on the higher parts

Big scale traditional farmland

The Black Isle

“The most of use grow 3 types of crops: barley, wheat and rapeseed ”

Scattered throughout are relicts of an earlier time, echoes of a more diverse past before large-scale, single-crop agriculture became part of the area’s identity. A lonely crofters house stands hidden in the landscape, and some historic plantation forests have partly survived.

Img. 18. Croft building (October, 2024)

Img. 19. Sign to croft (October, 2024)

Img. 20. Entrance to House of Rosskeen (Richard Dorrel, Dec 2019)

Img. 21. Historical forest (October, 2024)

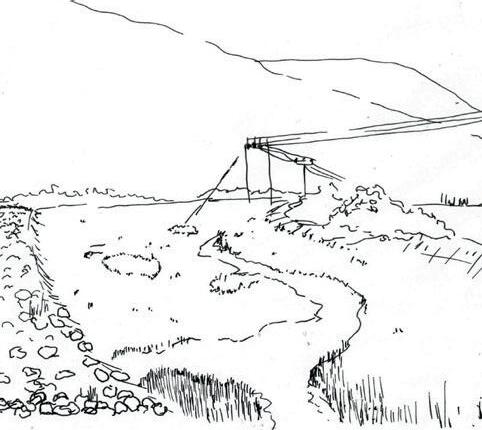

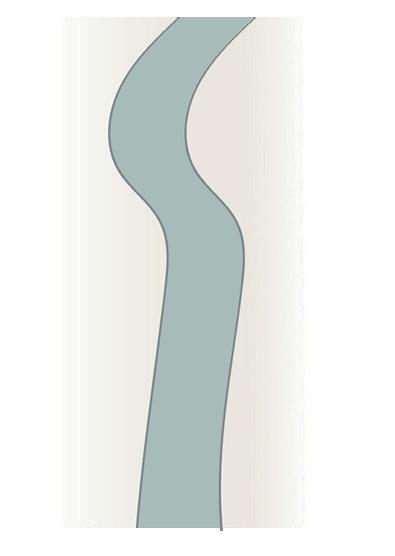

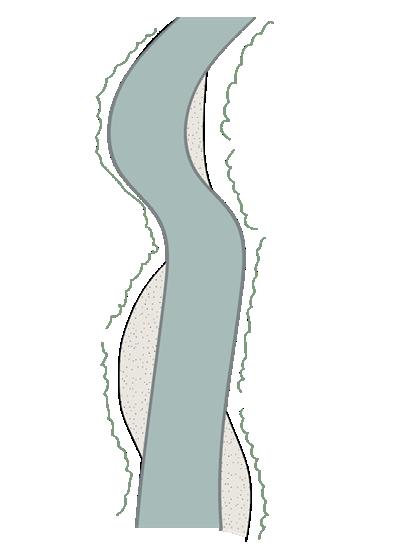

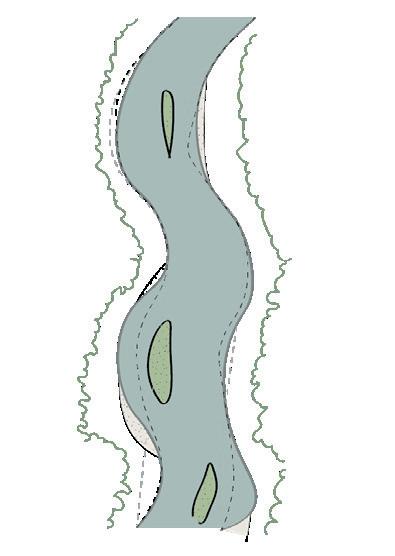

Flowing along with the gradient of landscape types, the rivers make their way downstream. The forest tames the water streams of River Averon as they descend the slopes. Upstream, the river carves into its banks, shaping the landscape through the force of its river flow.

Img.

Img.

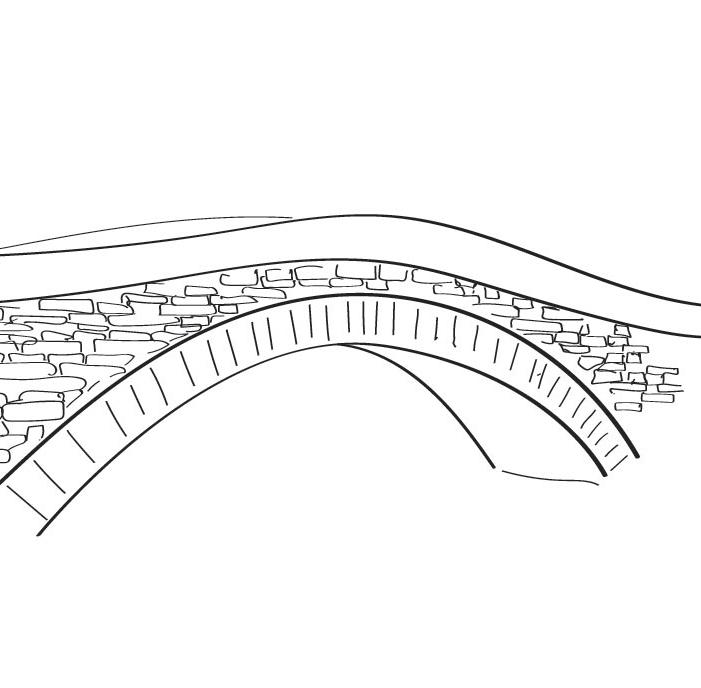

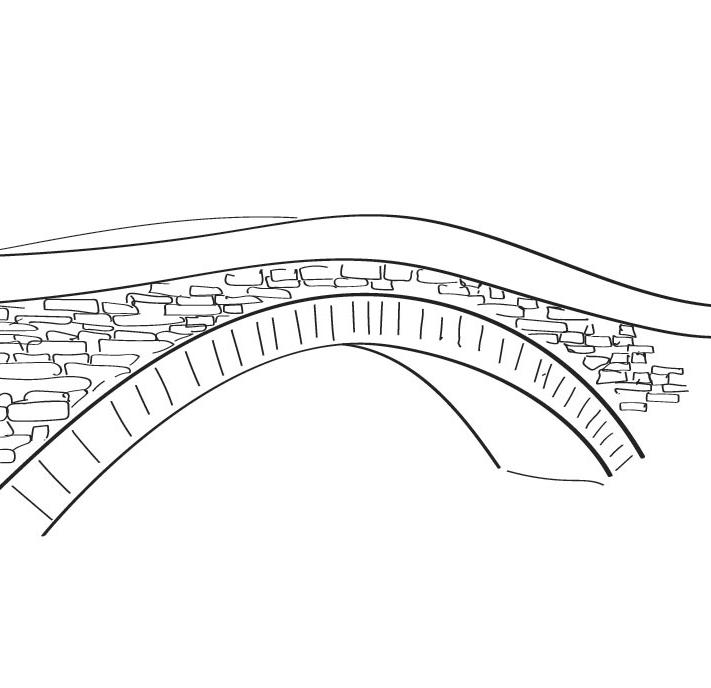

As the town of Alness takes shape, a bridge over the Averon forces the forest and river to part ways. It links both sides of the village, which has expanded over the years. The bridge continues into a road that cuts through the landscape gradient.

Alness is built next to the river along a single main road, where shops and eateries breathe a surprising vibrant life. The original main street endures.

However, south of the old town, industrial growth has disrupted the emotional and tangible connection between river and land.

Img. 25. Bridges over the Averon (Bob Embleton, 2010)

Img. 26. Teaninich Distillery (Valenta, Sept 2018)

Img. 27. Alness high street (May 2024)

The river Averon has been tamed and channelised. Its once wild course is now straightened, its banks tiered and paths form walls, guiding the water towards the river mouth through engineered fish traps.

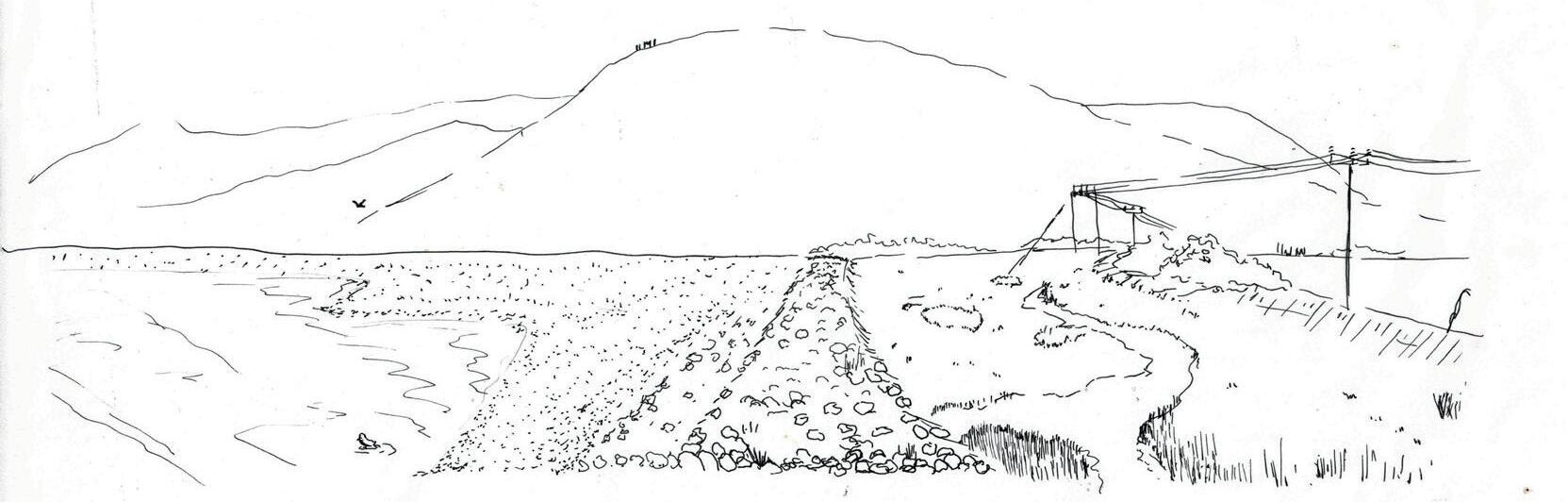

At the Averon river mouth, two seminatural realities coexisted.

On one side, a human-made sheltered area supports a fragile balance between recreation and ecology, allowing diverse species to thrive. The tides moved in and out across a shingle barrier, breathing life into salt marshes protected from the harshest movements of the sea. A quality of the river mouth.

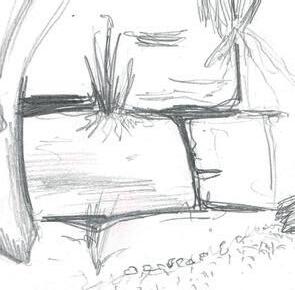

On the other side, the tides move in and out revealing the hidden stages of the tidal flats. Old relicts lie scattered: traces of long-forgotten interactions with the Firth.

Img. 28. River Averon (May 2024)

Img. 29. Low tide (May 2024)

Img. 30. River Averon (May 2024)

Img. 31. Sketch shingle boarder behind the rivermouth (May, 2024)

Img. 32. Saltmarsh behind the single border (May 2024)

Border for high water

Walkingpath

Agricultural backland

Black Isle

Hidden relicts during low tide

Substrate for shellfish (old poles)

The water prints capture interpretations of the movement of the flow and, occasionally, disruptions from pollution, such as oil traces leaving sharper, darker marks.

Img. 33. Alness distellery (May 2024)

Img. 34. Waterprint site: Puddel Dalmore Disterllery (May 2024)

Img. 35. Waterprint (May, 2024)

Nutrient outlet of distellery

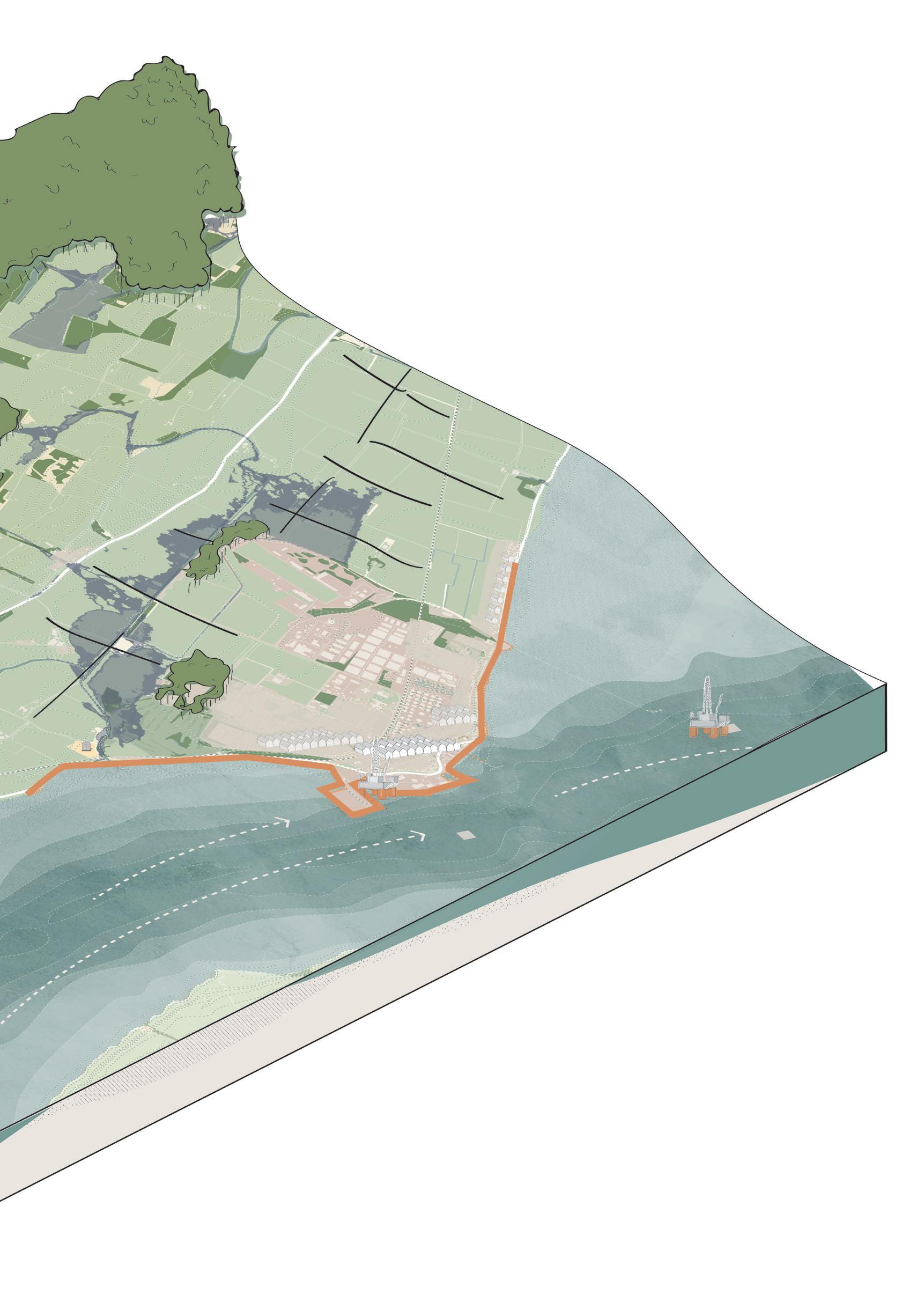

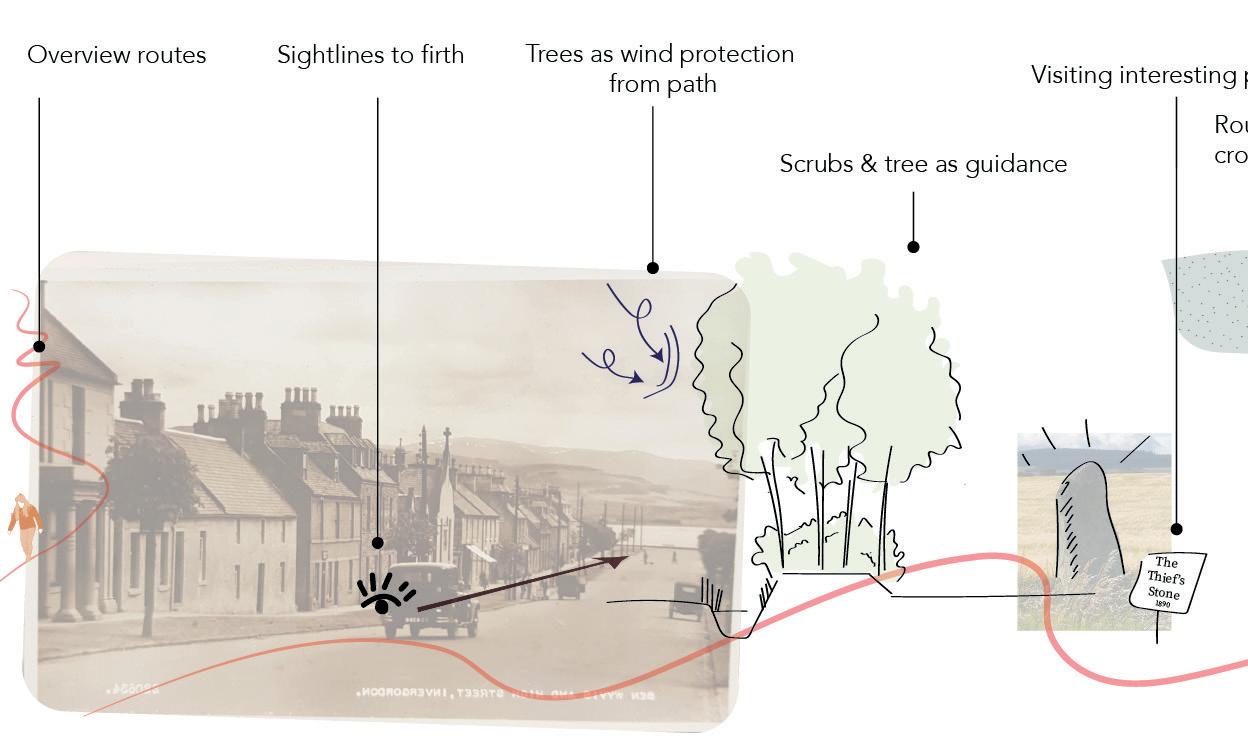

Heading along the coast towards Invergordon, the other village in this study region, the atmosphere grows harsher. The shoreline road thunders with cars, leaving little space for wanderers or dreamers. This barrier cuts off the hinterland from the water. The harsh wall creates no space for the water of the firth to breath or for people to interact with it. I want to touch the water, but it remains out of reach.

Unsafe busstop next to the car road

Towards Alness

Img. 36. Road dominated along the shoreline (May 2024)

Img. 37. Harsh border (May 2024)

Img. 38. Houses next to the shoreline (October 2024)

barrier to the waterfront

‘It is not a nice (cycle) ride along the firth. It doesn’t feel safe. I would rather cycle somewhere else.’

inhabitant

Invergordon presents a quieter, less lively impression compared to Alness. A local librarian tells me that the town has seen better days. The main street hosted scattered businesses, but lacks the vitality of a true town centre.

Many industrial employers live in temporary housing and miss the local connection.

Behind the town, the shoreline is lost behind the industrial harbour, cutting off almost all public access to the water. Only the sharp-eyed viewer will find a few sightlines to the shore.

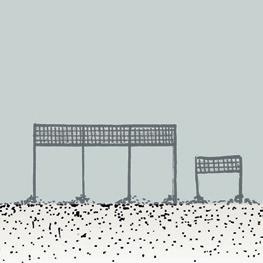

Oil platform style fencing

Industrial site on the shoreline

Img. 39. Industrial site forms barrier to shoreline (October 2024)

Img. 40. Bench with a view...(October 2024)

Img. 41. A small sightline towards the harbor area in Invergordon (October 2024)

Img. 42. Main street Invergordon (Historic Environment Scotland, October 2015)

Img. 43. Sign in Invergrodon for temporary accomodation (May 2024)

Not welcome

One of the few sightlines to the Firth from Invergrodon highstreet

Barriere of sight

Not welcoming

water behind

‘There used to be a butcher and a baker, but they are all gone. The supermarket has taken over. There is not much to do anymore (in Invergordon), especially for the young people’

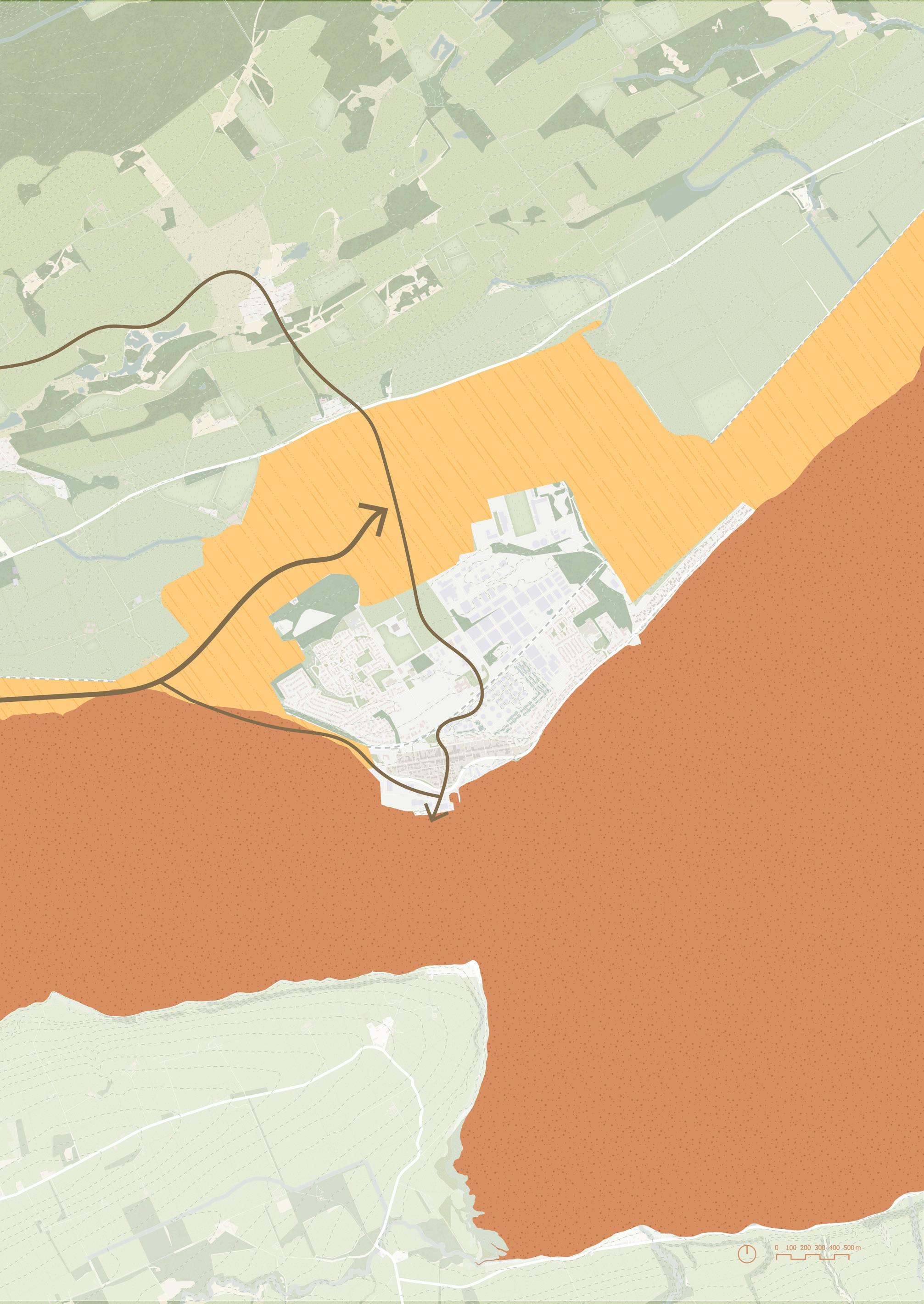

Lindathe local librarian

‘I don’t know anyone in town that works there’on the oil rigs). Are just fellows from outside.’

Inhabitant Invergordon

In the firth, oil rigs stand like massive sculptures, parked indefinitely. The water itself seems to transform into a massive rig. By day, this row of landmarks appears as massive silhouettes, and by night, they sparkle like Christmas trees. In the postoil era, they will become the new relicts of the future.

Img. 44. Oil rigs parked in the Cromarty Firth (May 2024)

Img. 45. Sunset (October 2024)

Img. 46. Firth at night ‘Oil rigs light up like christmas lights’ (October 2024)

Img. 47. Sketch of rigs on the Cromarty Firth (May, 2024)

‘They light up like Christmas lights at night”

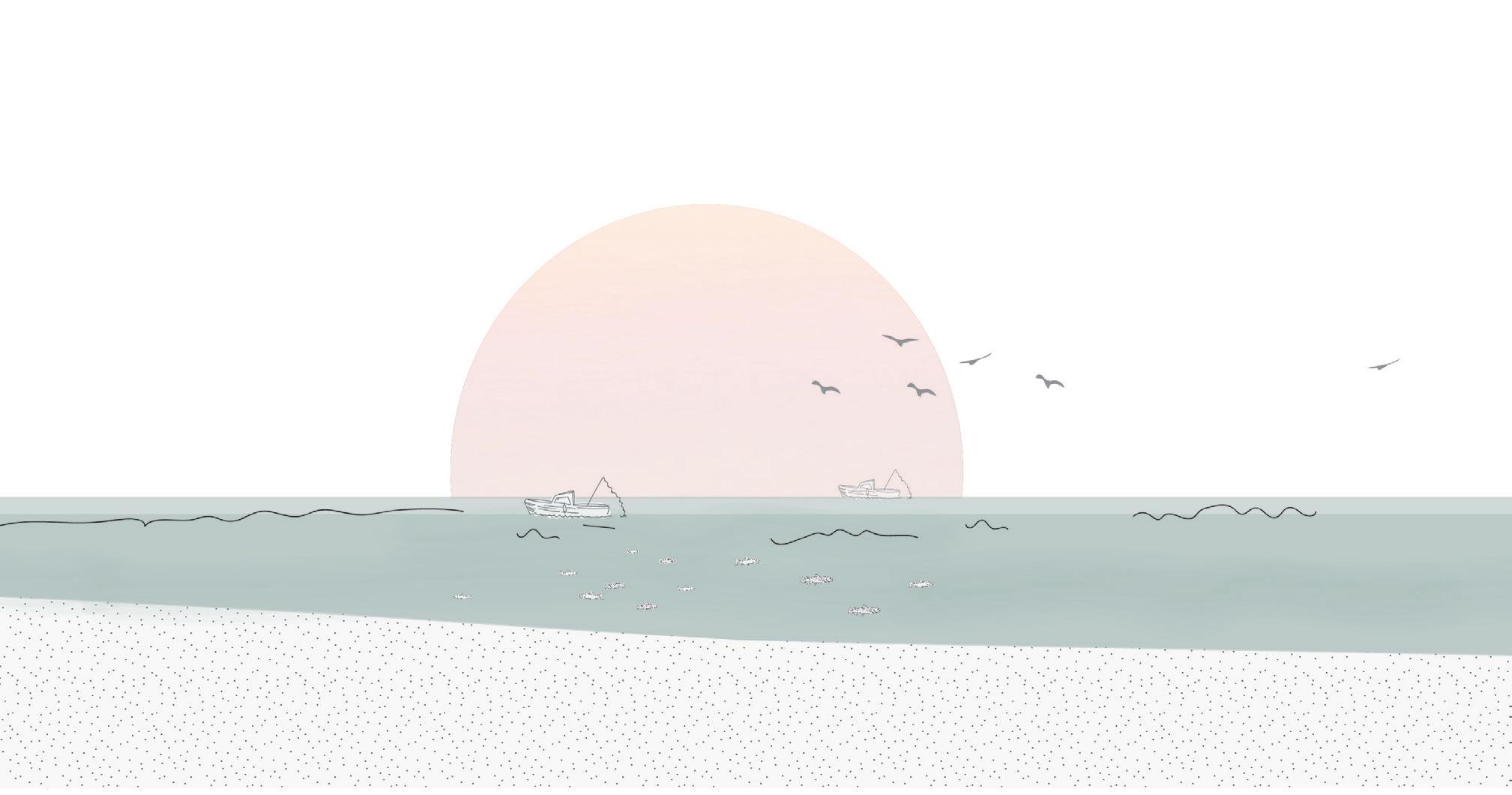

Glimpses of biodiversity remain despite the industrial presence. At the mouth to the Moray Firth, I caught sight of this dolphin. Pure magic. Yet, with a single blink, she was gone.

Img. 48. A dolphin in front of the oil rigs during fieldtrip at the mouth of the Cromarty Firth (May 2024)

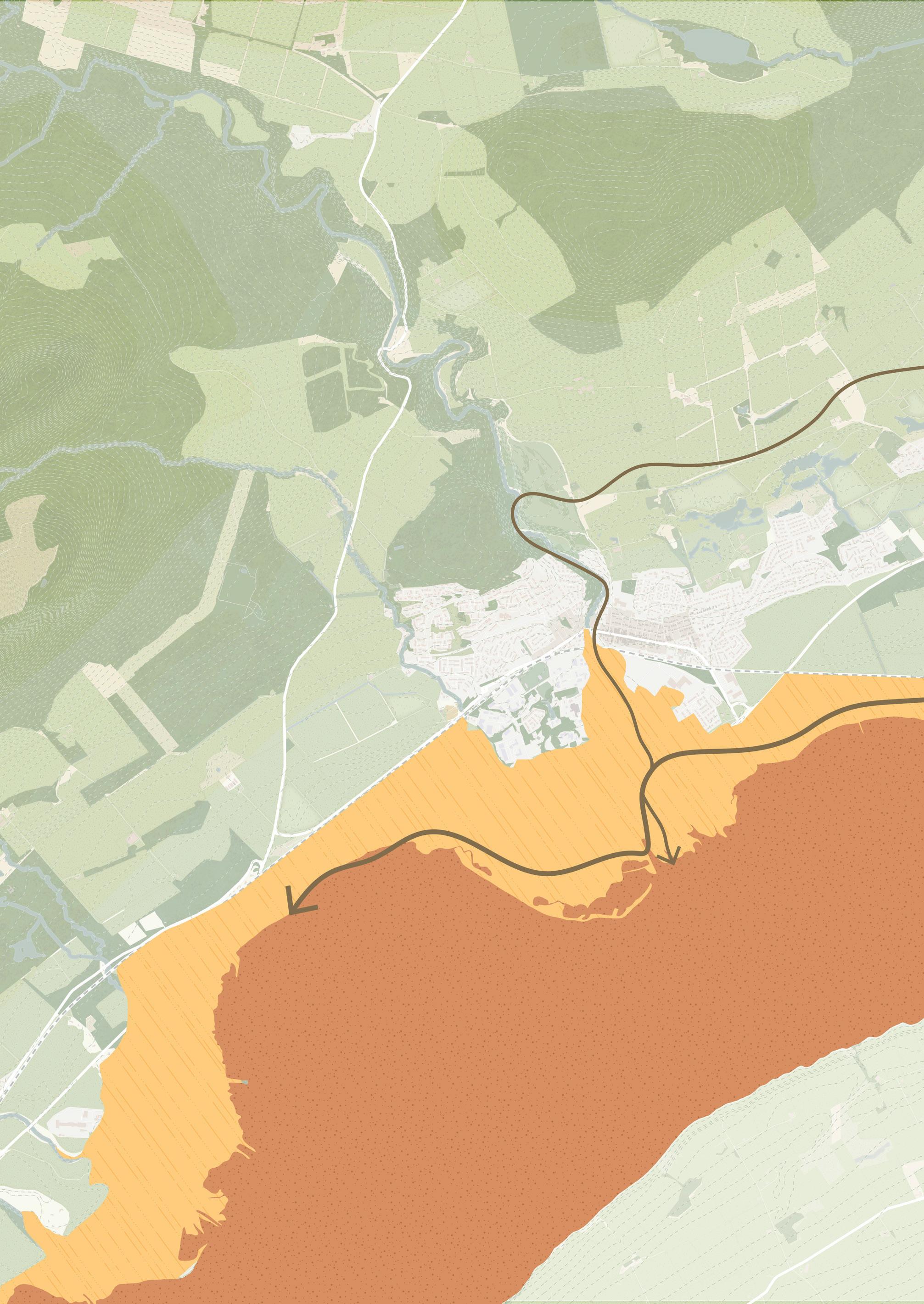

Our journey from the heights of the Highlands to the water of the firth revealed a layered landscape shaped by the forces of nature, history, and human ambitions. The landscape shows a gradient from peak to edge, but is disturbed by barriers that cut across the area. The people and water of firth are not physical and emotional tied together anymore, but traces can be found and restored.

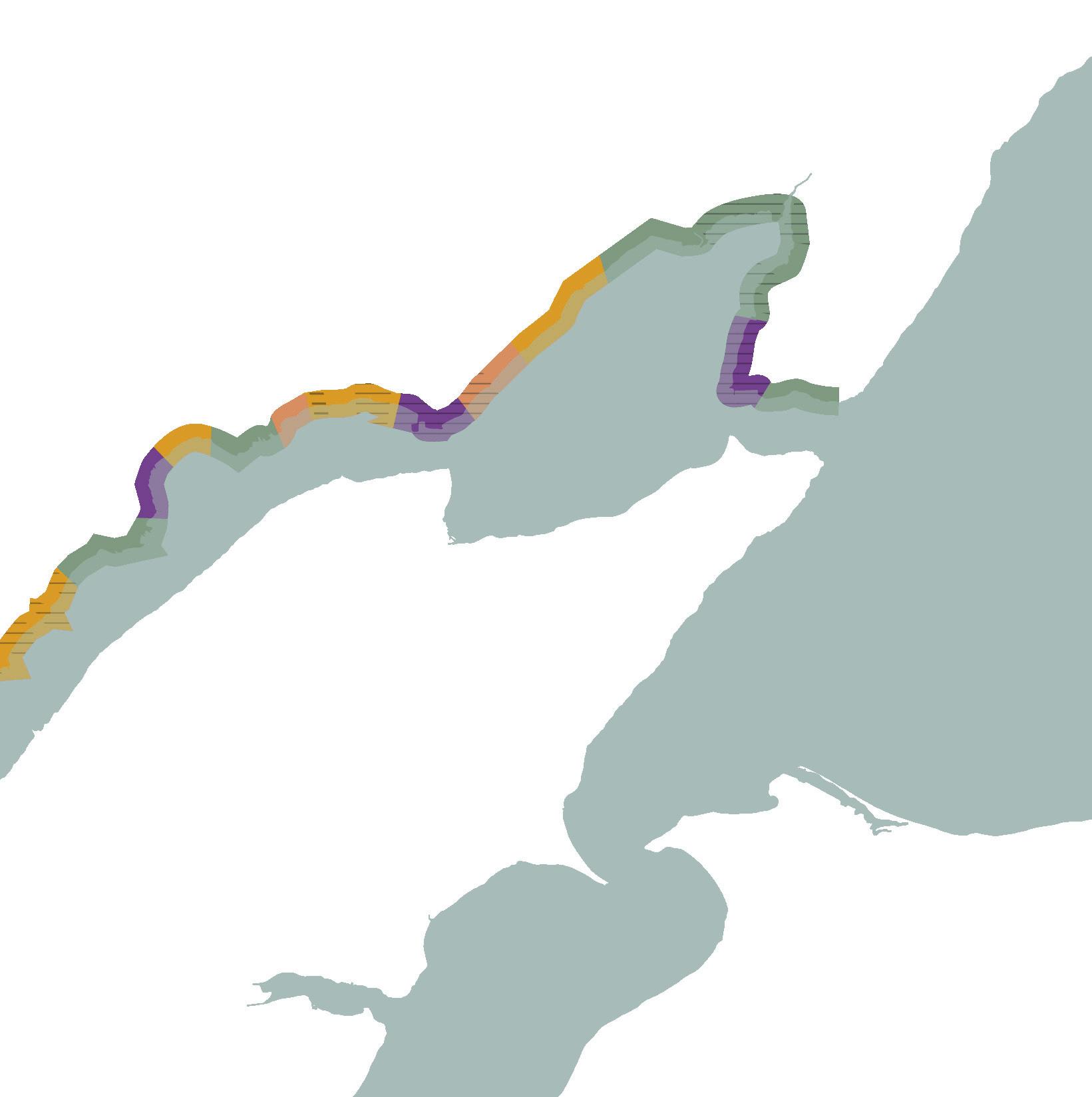

Img. 49. Layer approach of the landscape gradient (1), barriers that cut through the landscape (2) and intertidal area that shows different use and connections (3)

Restore and revitalise the physical, emotional, direct and indirect relationship between the people and the firth, therefore giving the Cromarty Firth a new identity in the post-oil future. Where the water and the land meet, new relationships are being woven. The Cromarty Firth will breathe again.

The Cromarty Firth will no longer be the hinterland or the backside, but will become the beating heart of the community.

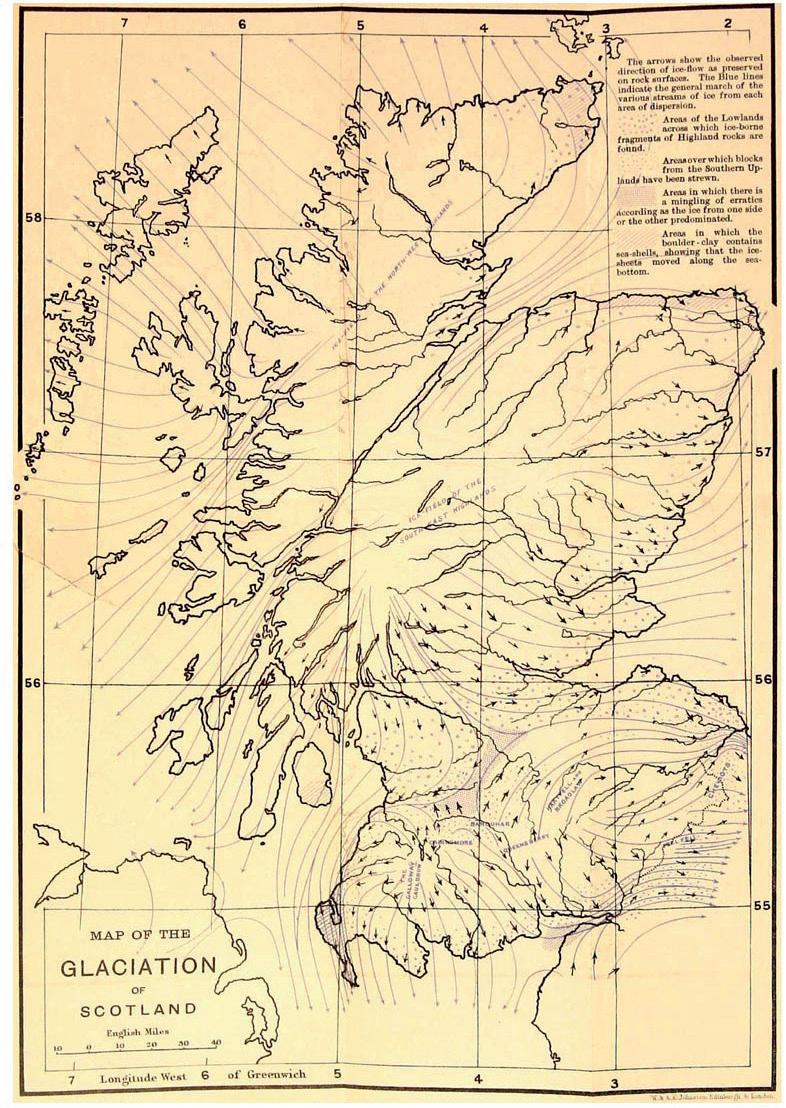

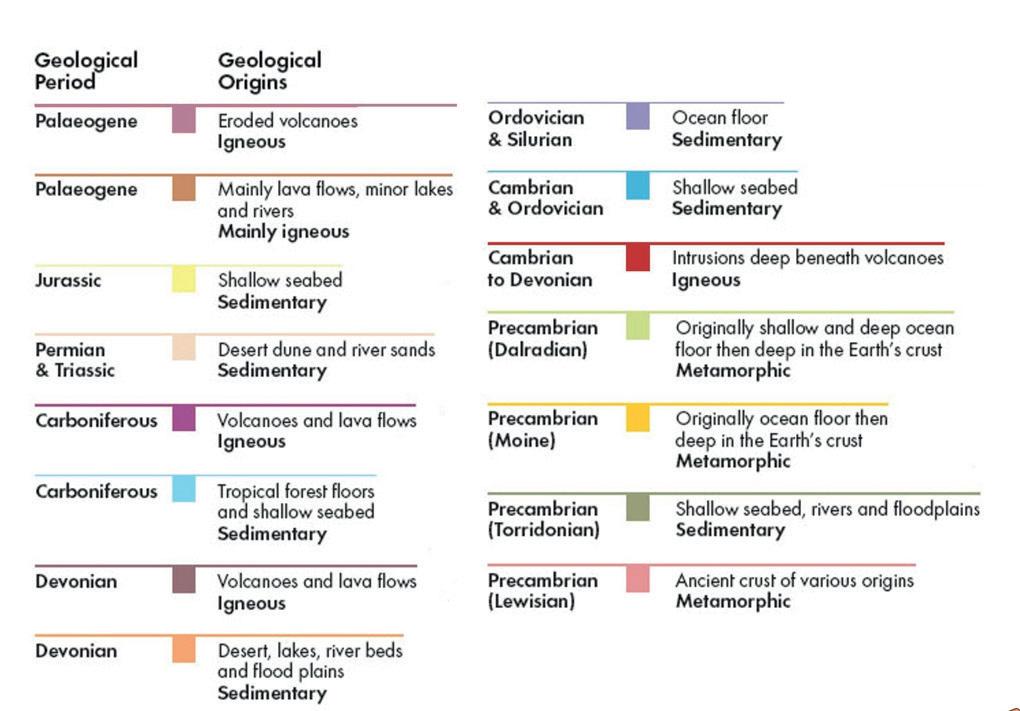

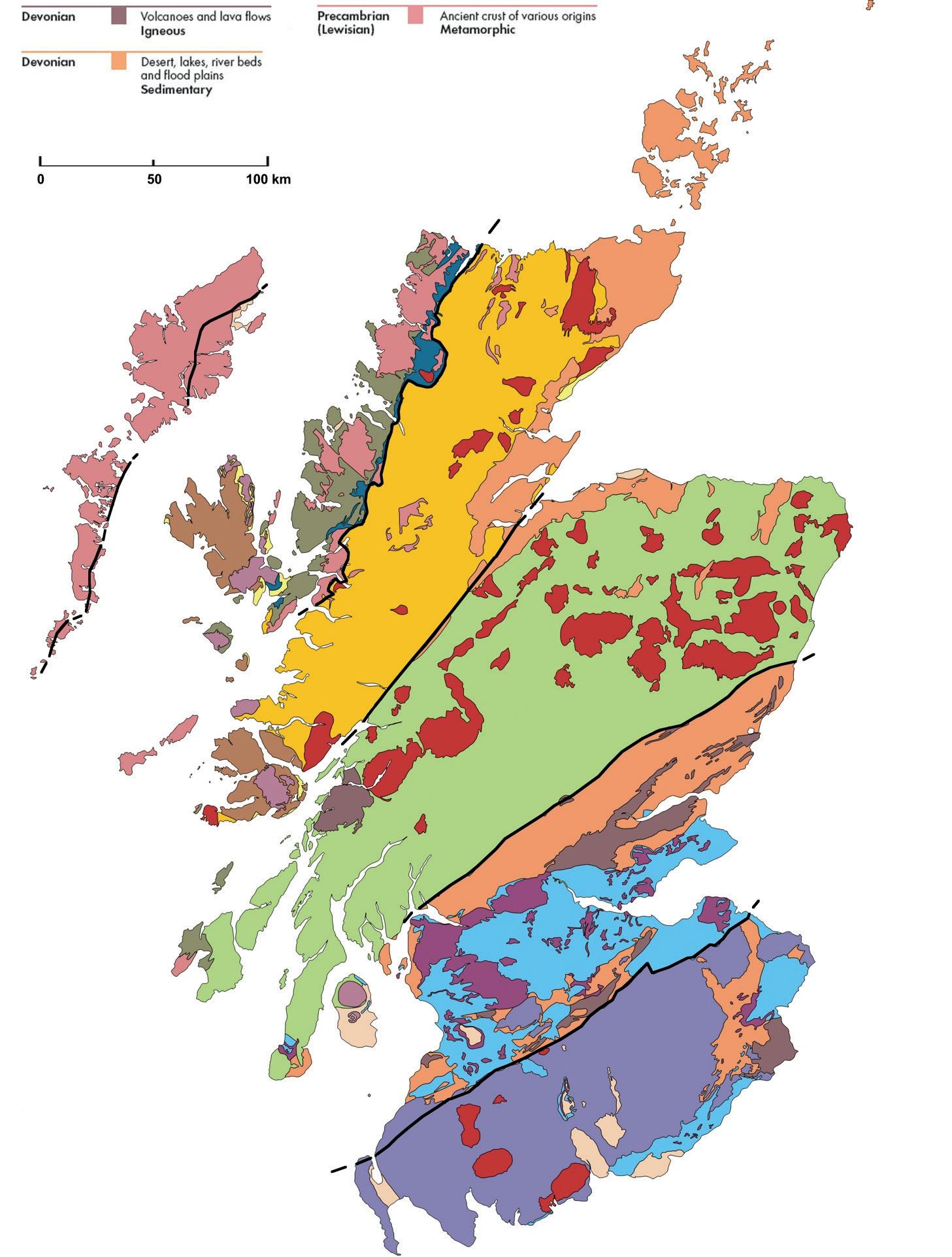

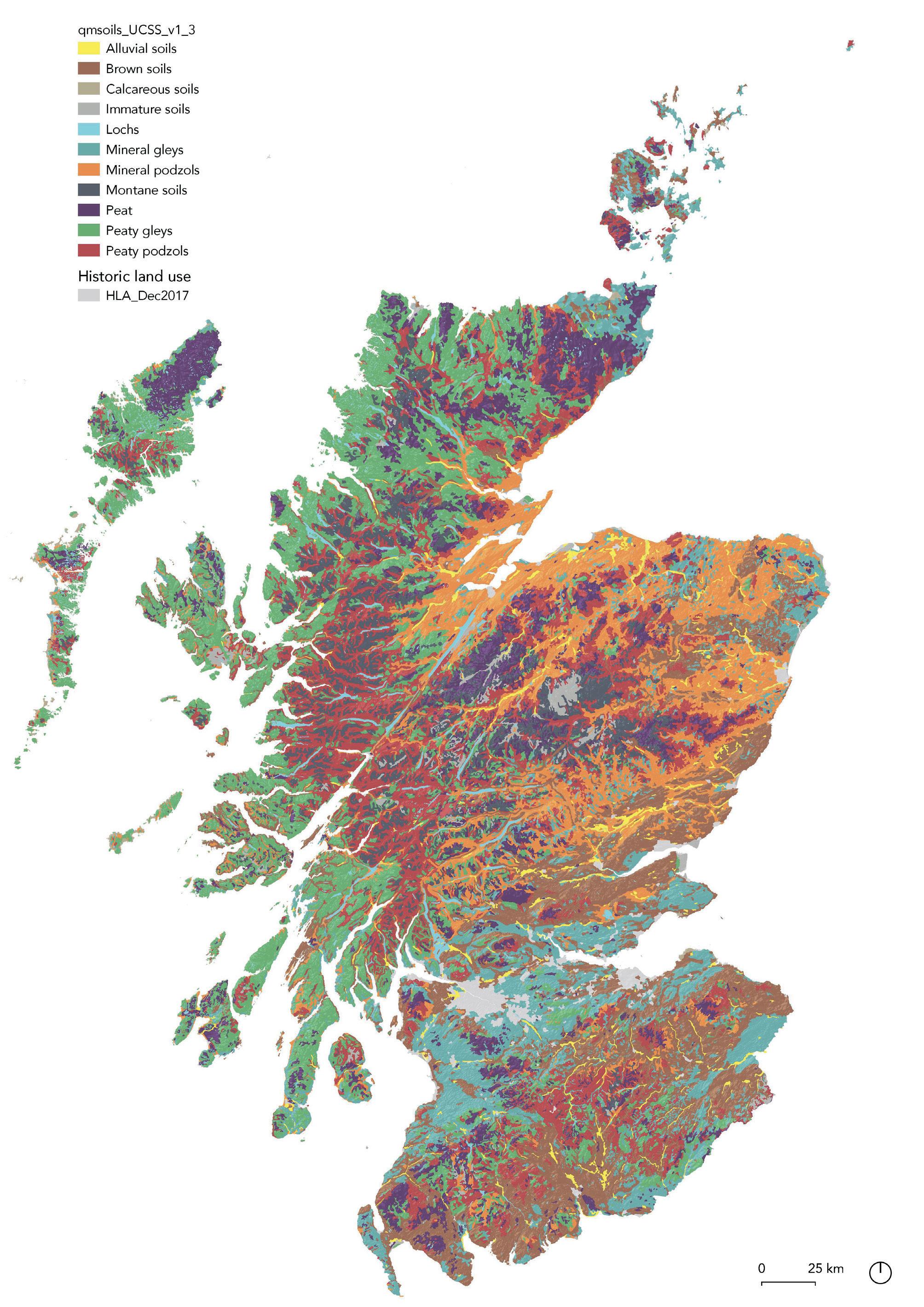

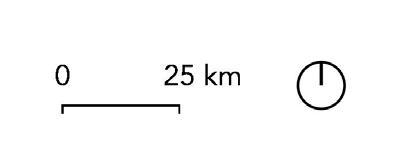

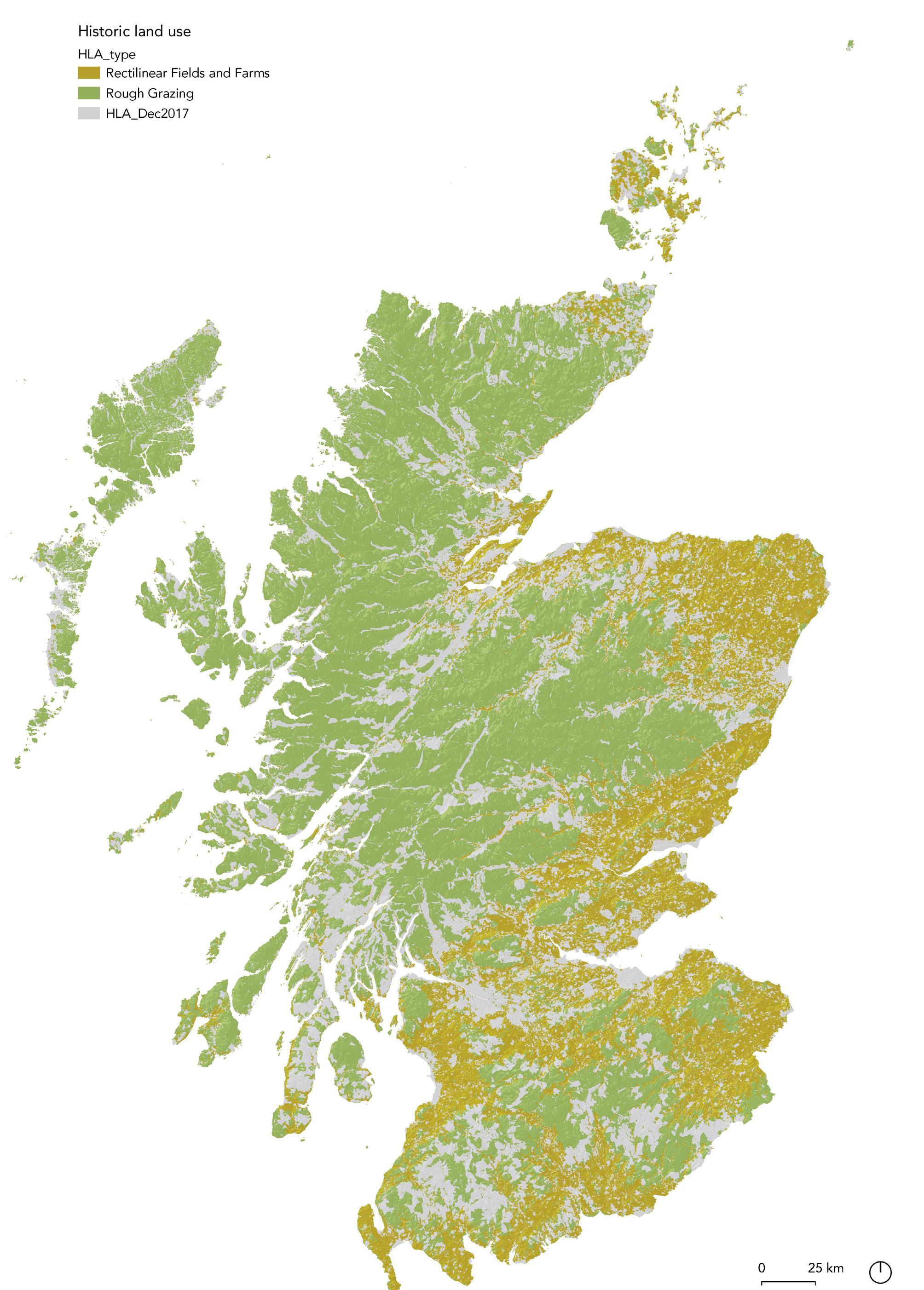

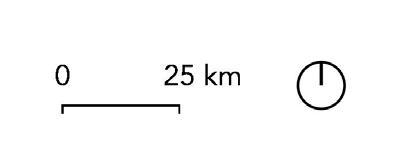

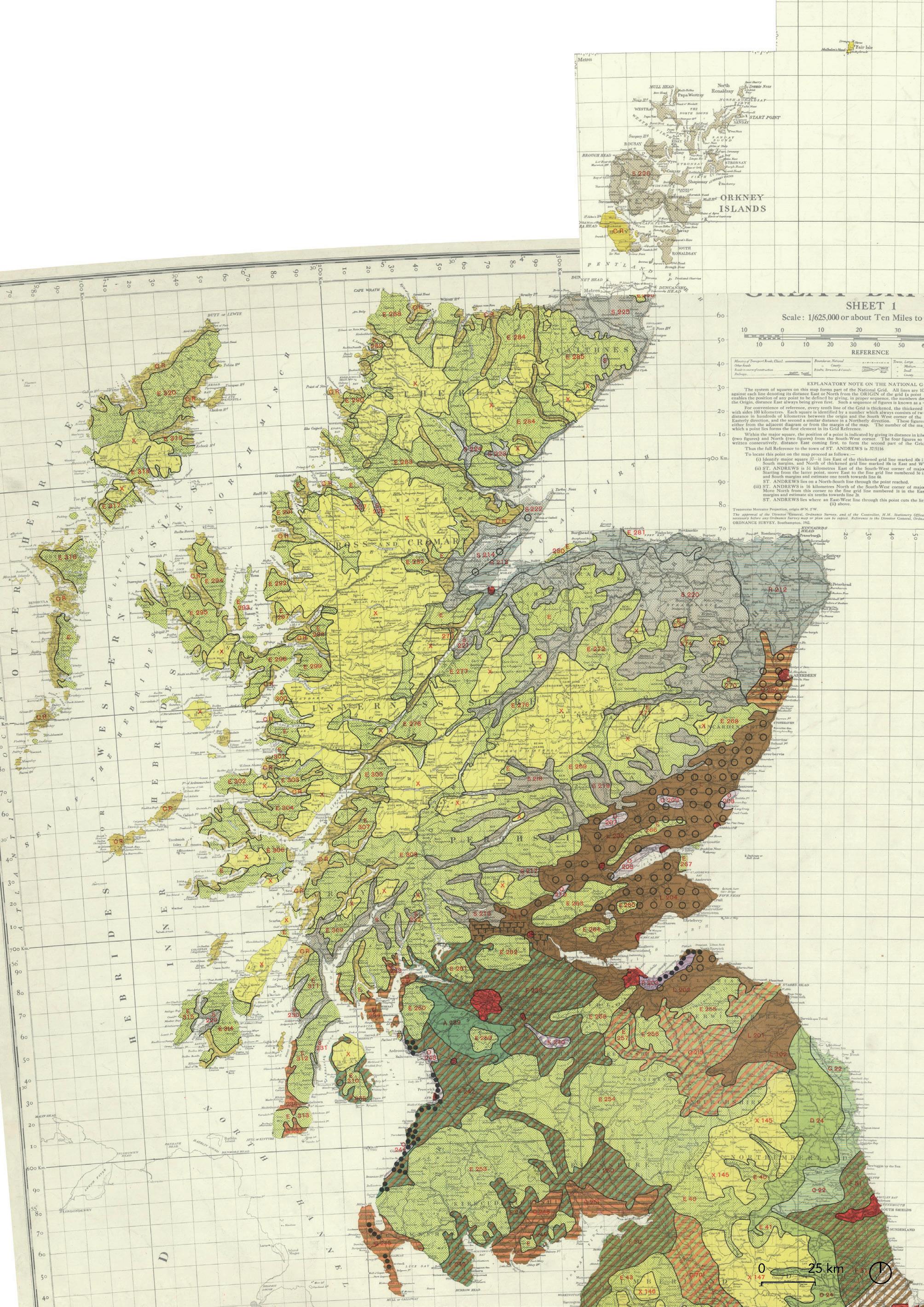

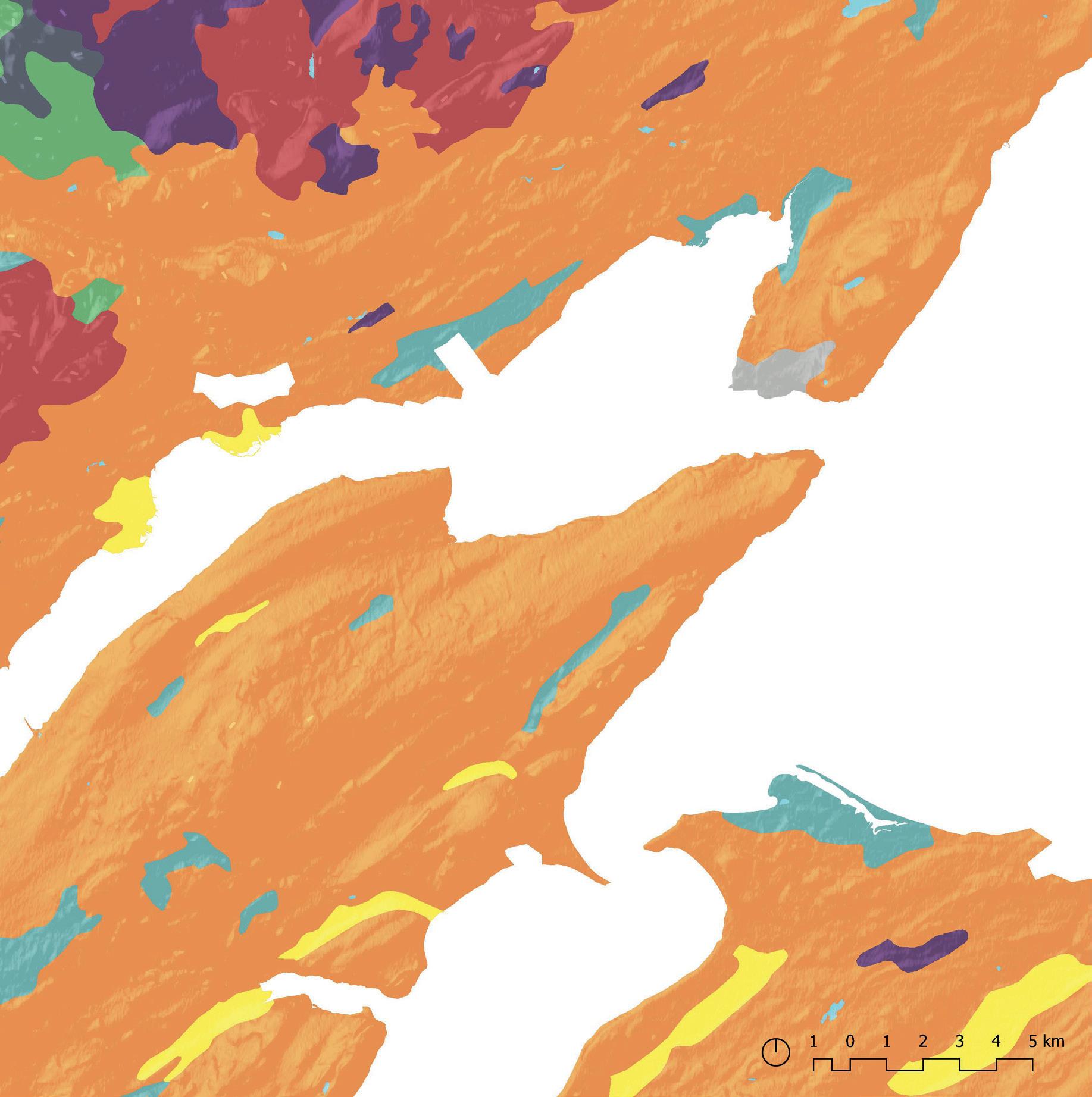

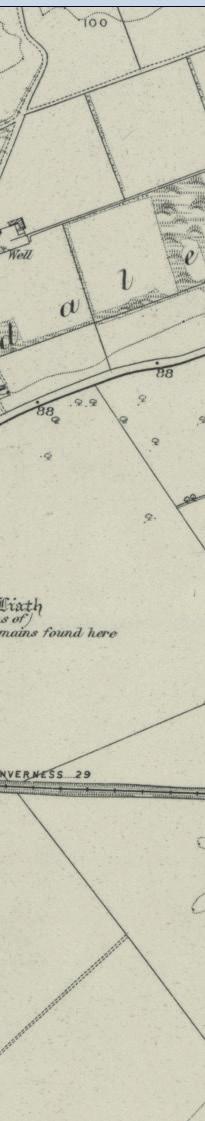

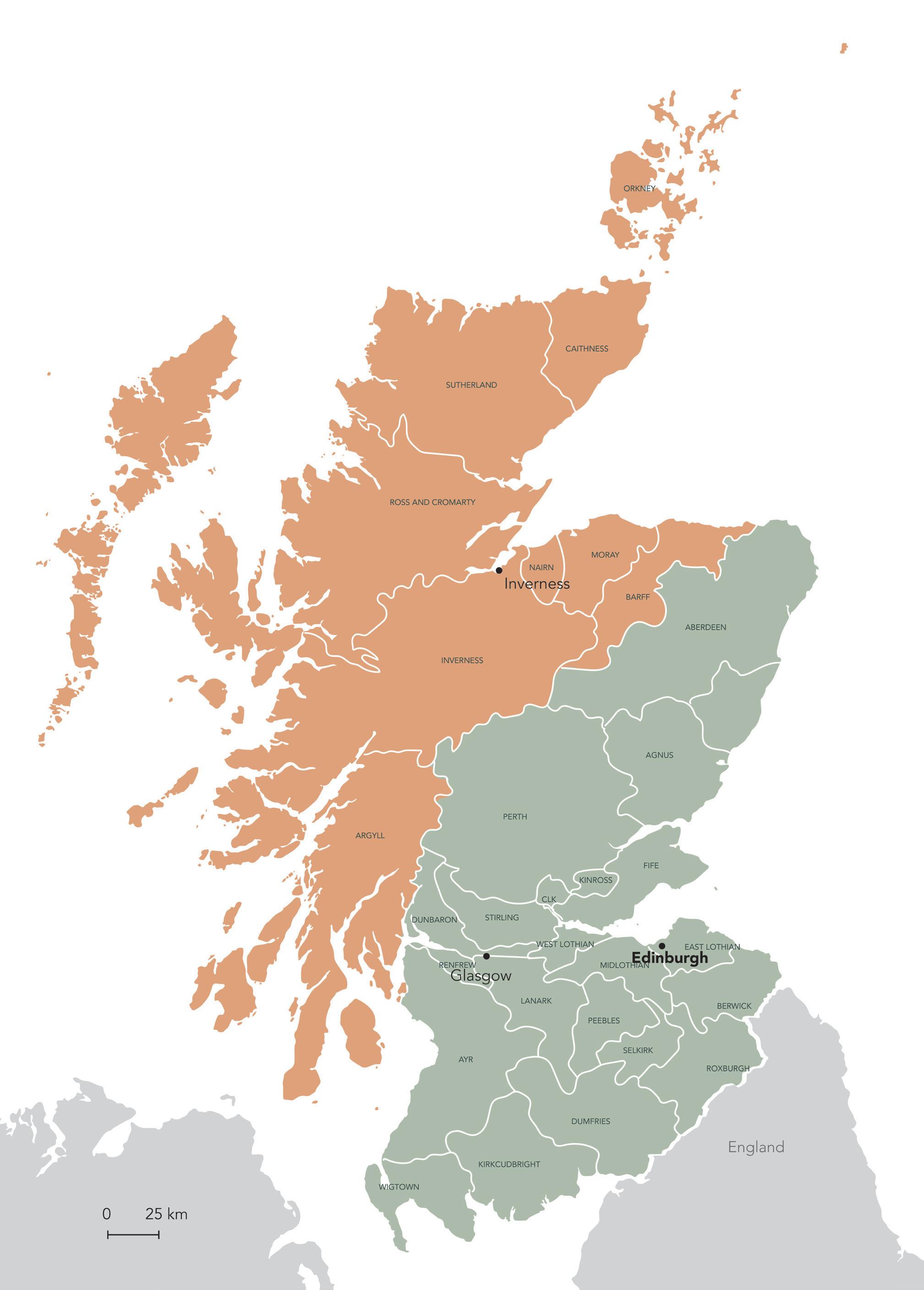

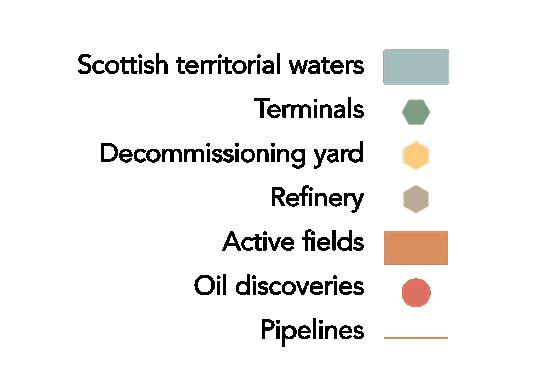

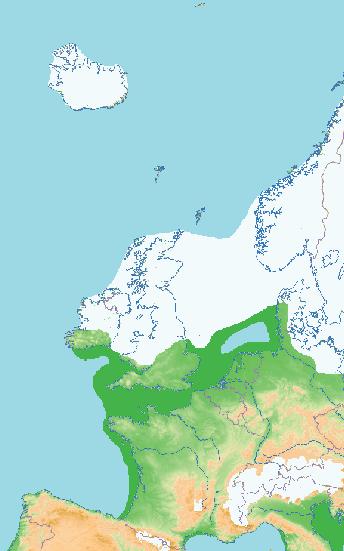

The underlying story of Scotland’s landscape of is rooted in geology. Over millennia, it has adapted and evolved in response to climate, resources and requirements (Watson & Dixon, 2018). More than 10.000 years ago, glaciers eroded the land and fault lines have since shaped the Scottish map (The Geological society, sd). Roughly Scotland can be divided into four geographical areas. The North-West Highlands are separated from the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen Fault line (GGF). This fault line remains active, with the northwest and southeast sides of the GGF still shifting in opposite directions. This fault line had a major effect on the shaping of the Moray Firth. The GGF controlled the shape of the Black Isle that shelters the waters of the Cromarty Firth (Gillen, 1993).

Img. 53. Geological map of Scotland (National Library of Scotland - NatureScot)

Northwest Highlands

Grampain Mountains

Central lowlands

Southern Uplands

Img. 55. Map of Scotland with faultlines + arable land (data: HLA)

Alluvial soils

Brown soils

Calcareous soils

Immature soils

Lochs

Mineral gleys

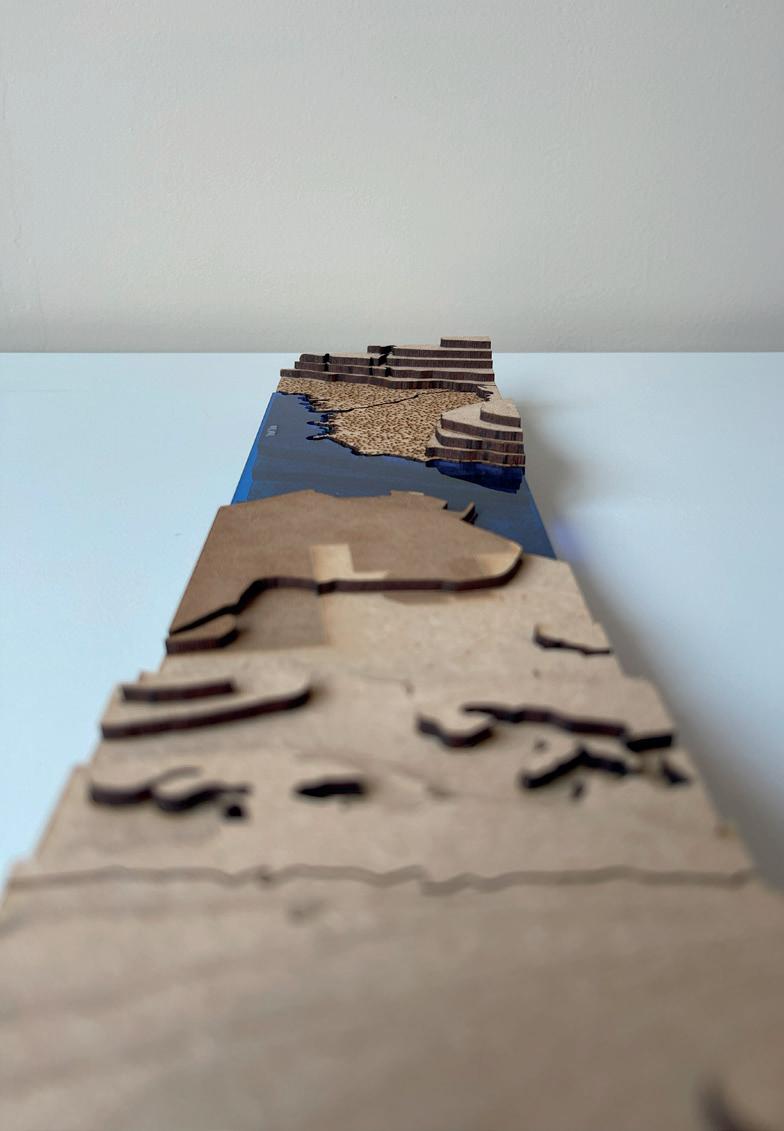

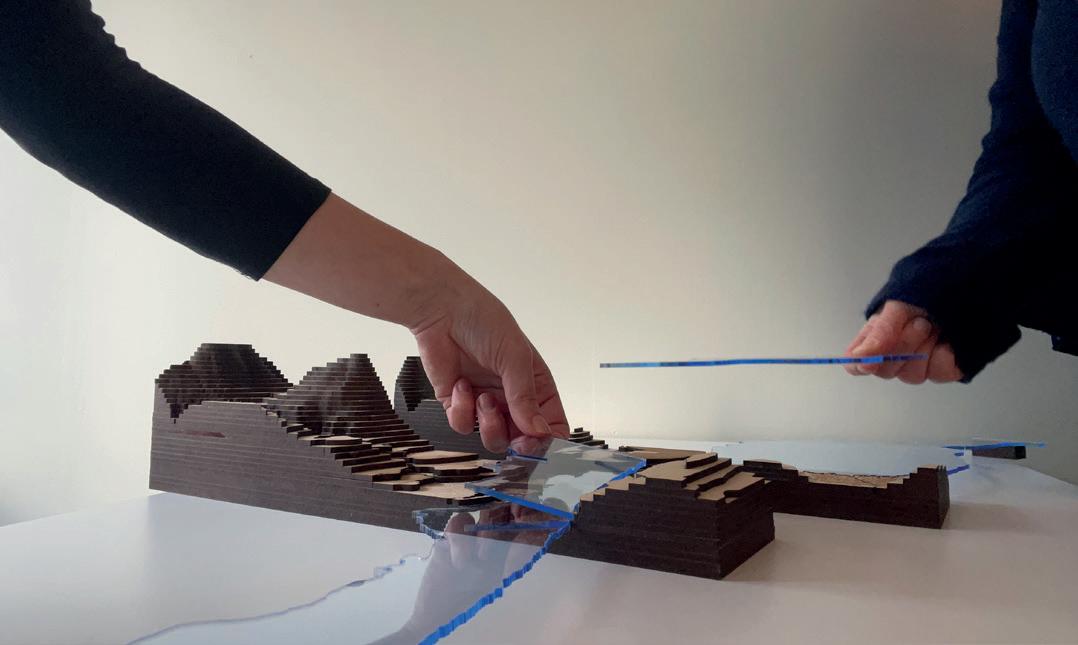

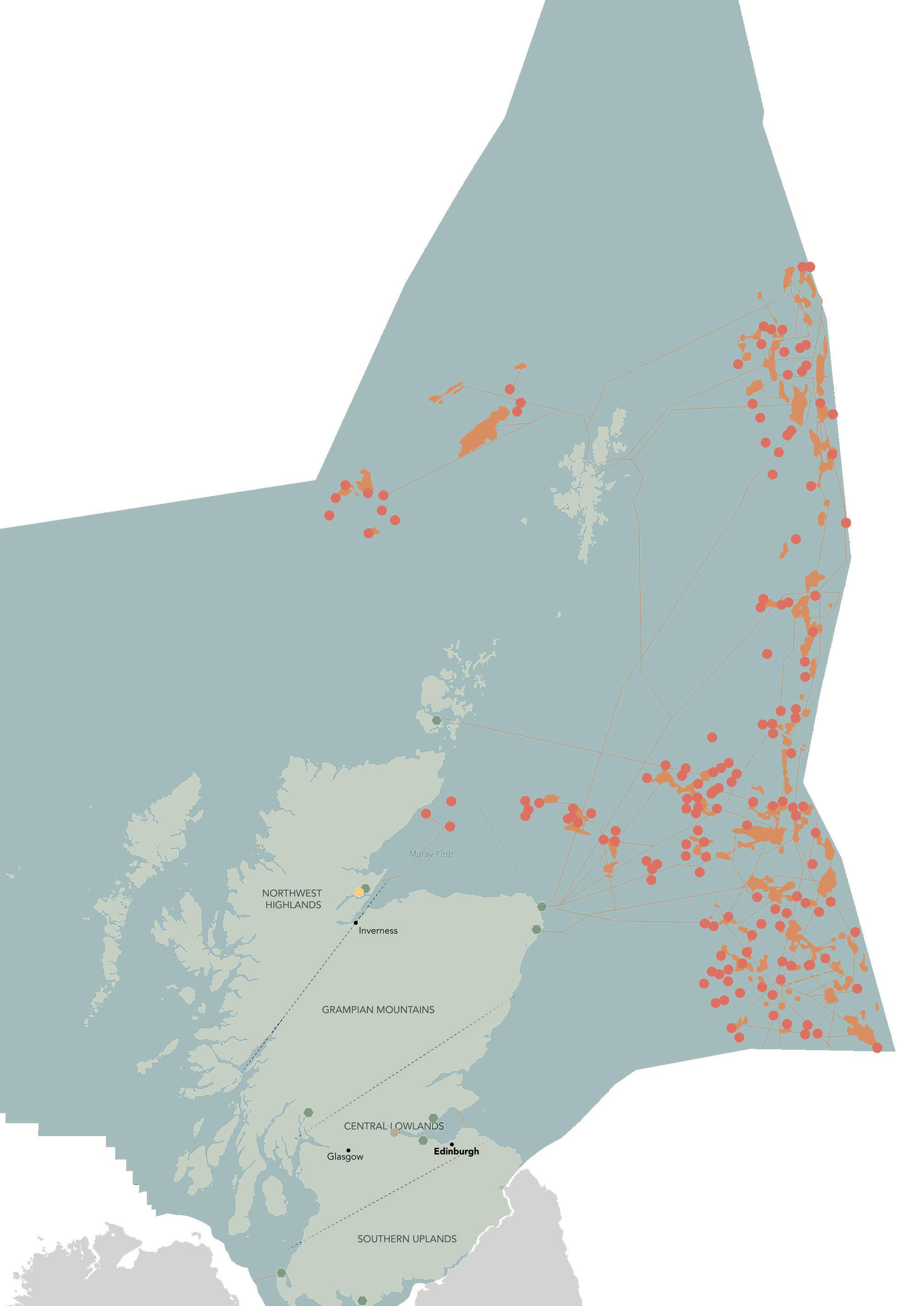

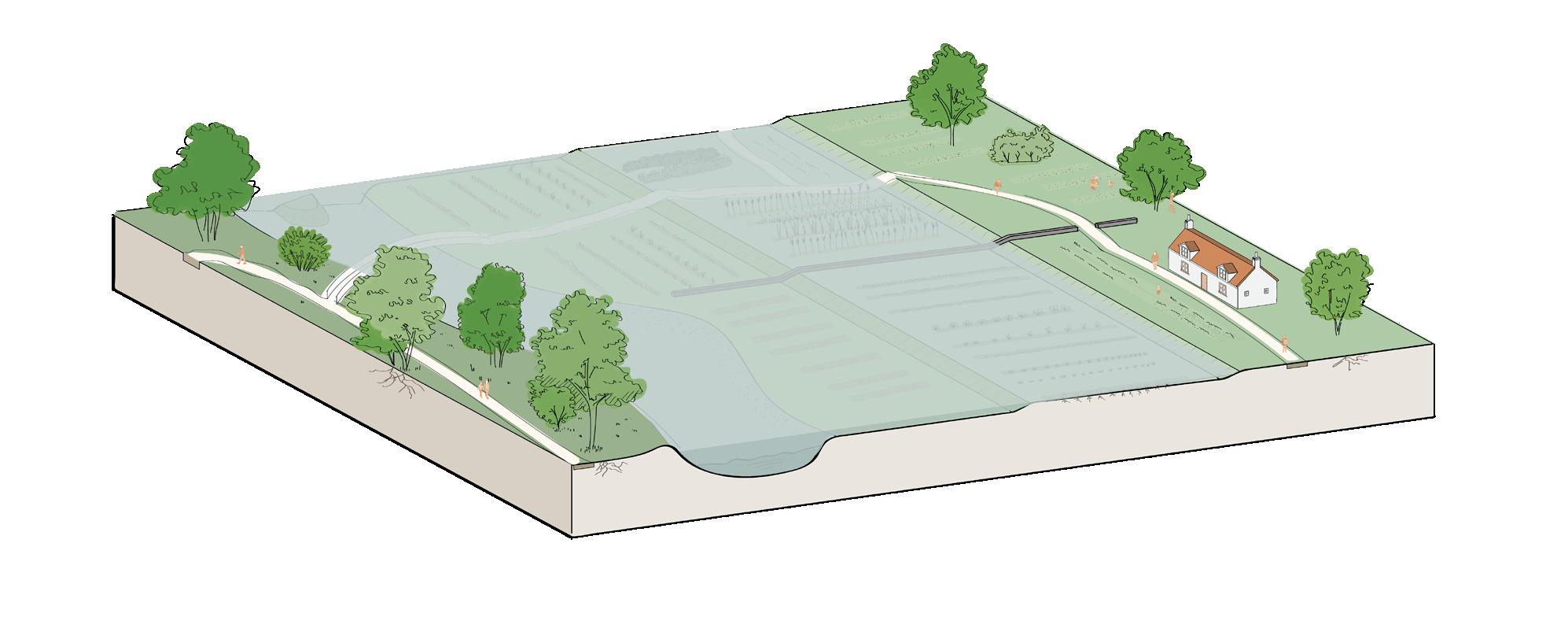

Img. 58. Landscape system of the focus area

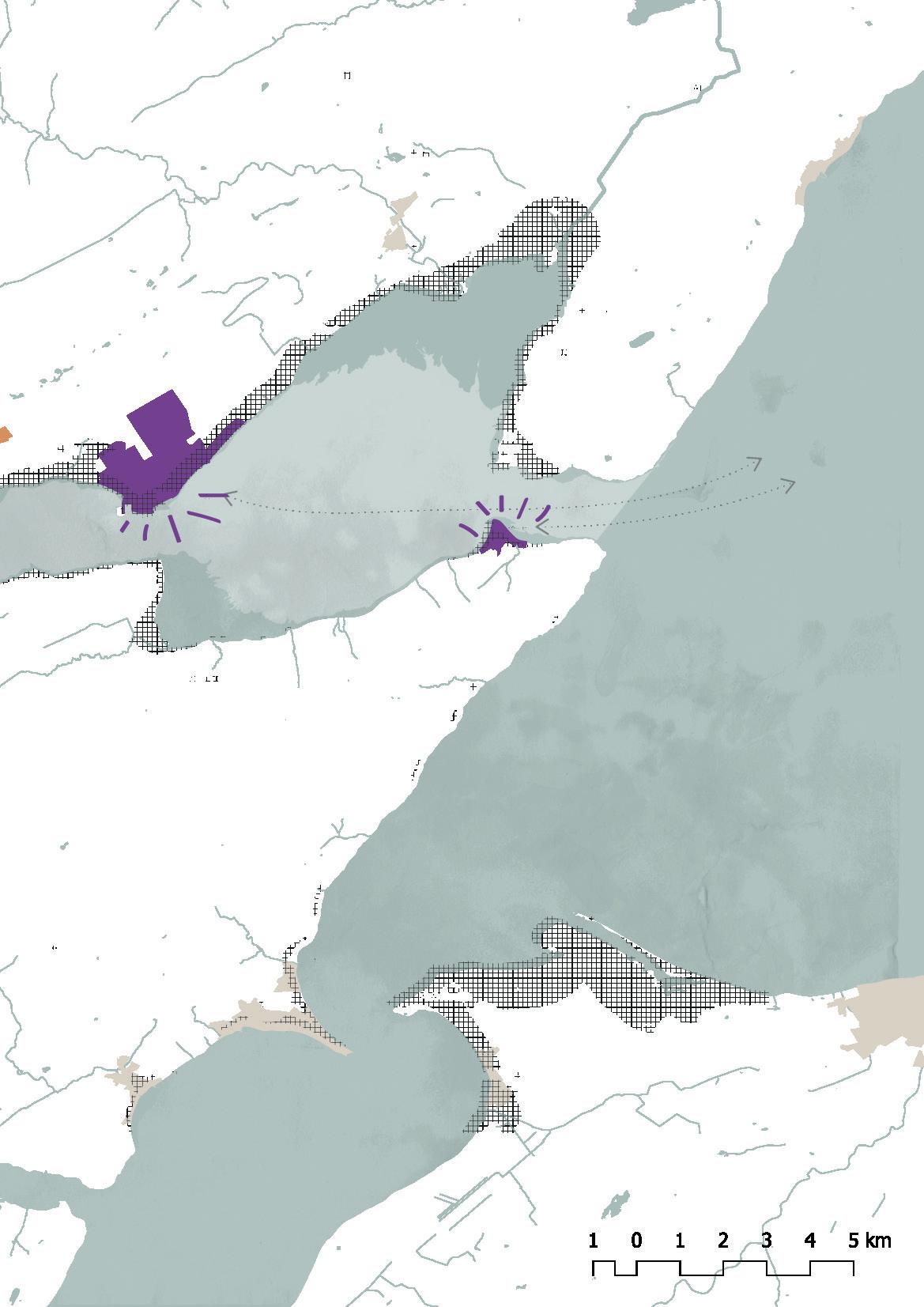

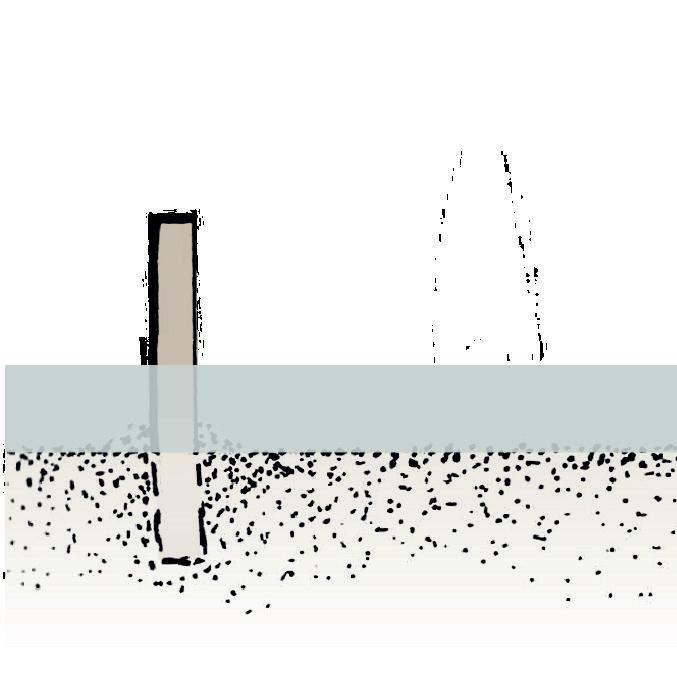

The Cromarty Firth (3.8 ha) is a sea arm of the Moray Firth. Glaciation has shaped the deep basin of the Cromarty Firth (NatureScot, 2019). The sheltered position of the Cromarty Firth is due to the highlands on its west side and the peninsula of the Black Isle on to the east. The coastline offers a gently sloping transition from the highlands to the sea, with a wide and flat coastal edges of glacial deposits and soils. The narrower parts of the firth have developed into estuaries due to sedimentation, leaving the surrounding the soil around the coastline primarily as mineral podzols. This fertile soil, combined with the gentle sunny slope, has made the area suitable for agriculture in northern Scotland.

Over time, settlements have formed on this gentle slope, either beside the water of the firth or alongside the rivers that sustain it.

industrial coast

living next to the coast

agricultural backland

semi natural coast

Artificial buffer

River streams

Img. 60. Streams that enter the Firth from the North side with the water catchment area. Where the water entres the Firth, there is a semi natural coastline.

Scale model of the location of the villages on the Firth (1:50.000)

The Cromarty Firth is fed by several river that flow into its waters. The river Conon, entering from the south by the Conon Bridge, is the largest freshwater supplier. Other suppliers of freshwater include the River Averon, Glass and Sgitheach. On those river outlets we see a semi-natural connection to the firth.

In recent years, the UK’s marine environment has suffered significant losses. Saltmarshes, mudflats and seagrass meadows are in decline, while Scotland’s coastal infrastructure and habitats face growing threats. Physical distortion as well as pollution have made intertidal communities vulnerable (Scottish Government, 2011). With tidal difference of up to three metres, these zones have become more tighter, partly due to the construction of hard quays and land reclamation, also known as coastal squeeze. These habitats provide a natural sea defence by absorbing wave energy and are important for young fish and many wintering birds and waders. The waters of the Cromarty Firth remain home to various fish species. On occasion, dolphins and porpoise find their way into the Cromarty Firth from the Moray Firth.

Pink-footed Goose

Anser brachyrhynchus

Tringa totanus

Stonechat

Saxicola rubicola

Dunlin

Calidris alpina

Anas penelope

Pintail

Anas acuta

Snipe

Gallinago gallinago

Haematopus ostralegus

Lapwing

Vanellus vanellus

Trout

Salmo trutta

Salmon

Atlantic salmon

swan

Cygnus cygnus

dolphin

Tursiops truncatus

Bar-tailed

godwit

Limosa lapponica

Harbour porpoise

Phocoena phocoena

Villages have long settled along the shores of the Cromarty Firth and besides its rivers. Due to the relative shelter and fertile soil, communities have developed here. Some former estates once stood here, within the historic territory of Clan Munro. At first glance, the landscape appears unchanged, with the underlying structure and landscape gradient remaining intact. However, socially, the region has undergone a notable transformation. The emotional connection to the region has become disconnected with a downward social development.

Most notably are the land reclamation in the region. This is an urban phenomenon which most occurred in the nineteenth century, creating new sites for harbours and industrial areas. This industry has contributed to a well-developed infrastructure. Despite this, social

development declined. The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivations shows that various neighbourhoods in this region score inadequate on topics such as health and education and continue to face challenges (Scottish Government, sd).

Nowadays, Alness and Invergordon show that they are working towards a new future perspective. In 2021, both villages have been selected as a part of ten other Climate Action Towns across Scotland by the Scottish Government (Architecture Design Scotland, sd). This project worked with local communities in small towns to empower and support them in placebased climate action. This initiative reflects a collective desire for fresh perspectives and a renewed direction for the future.

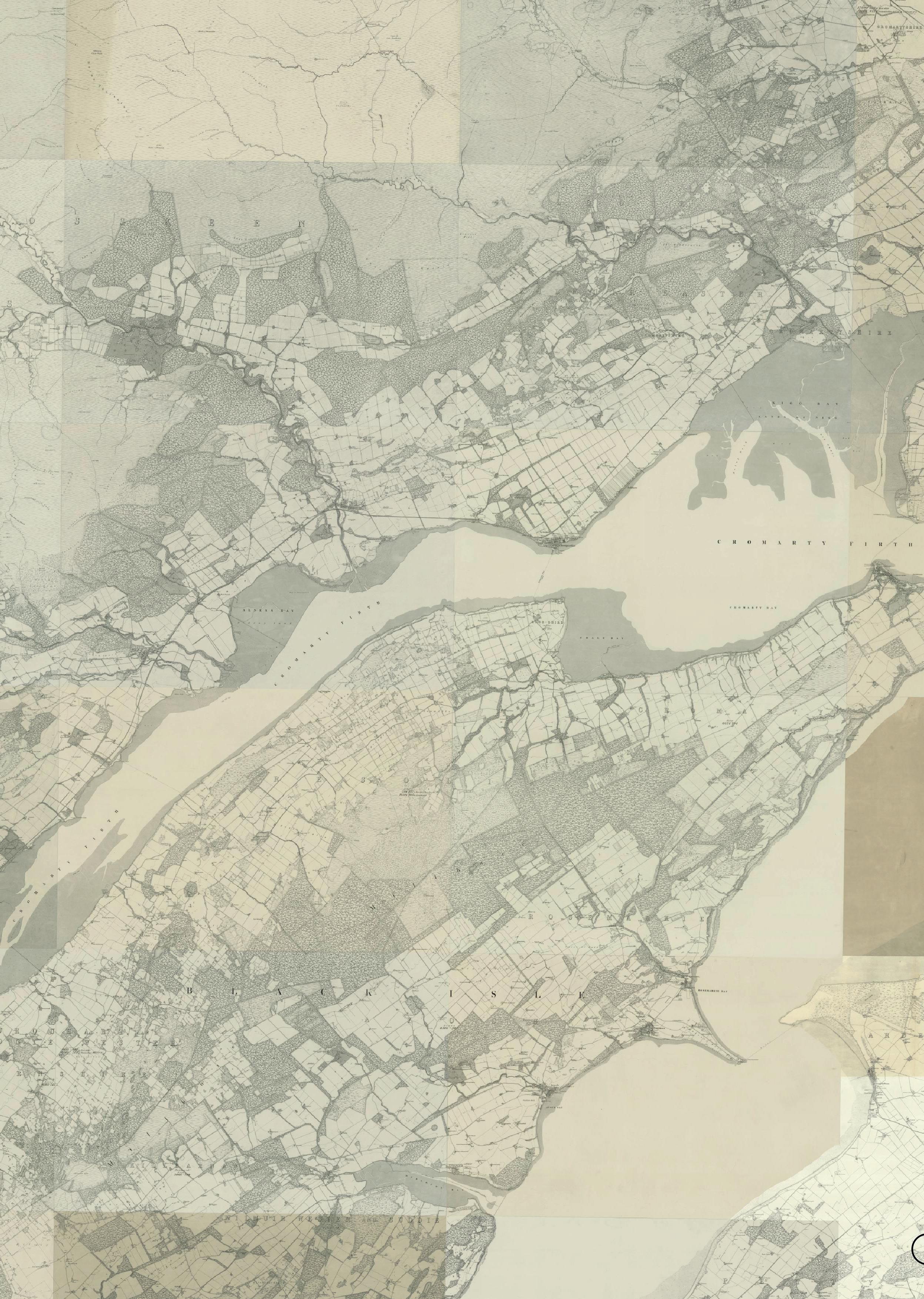

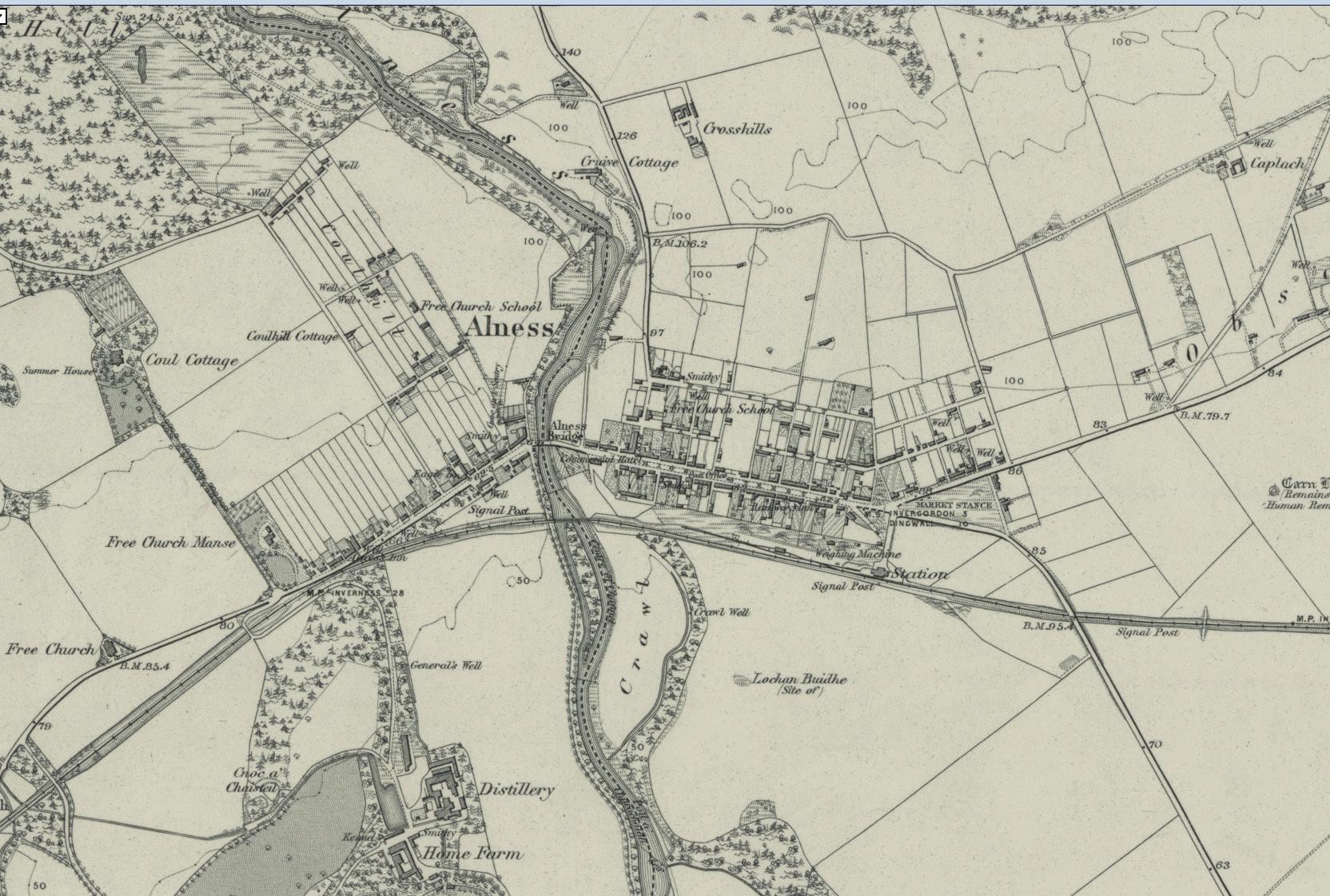

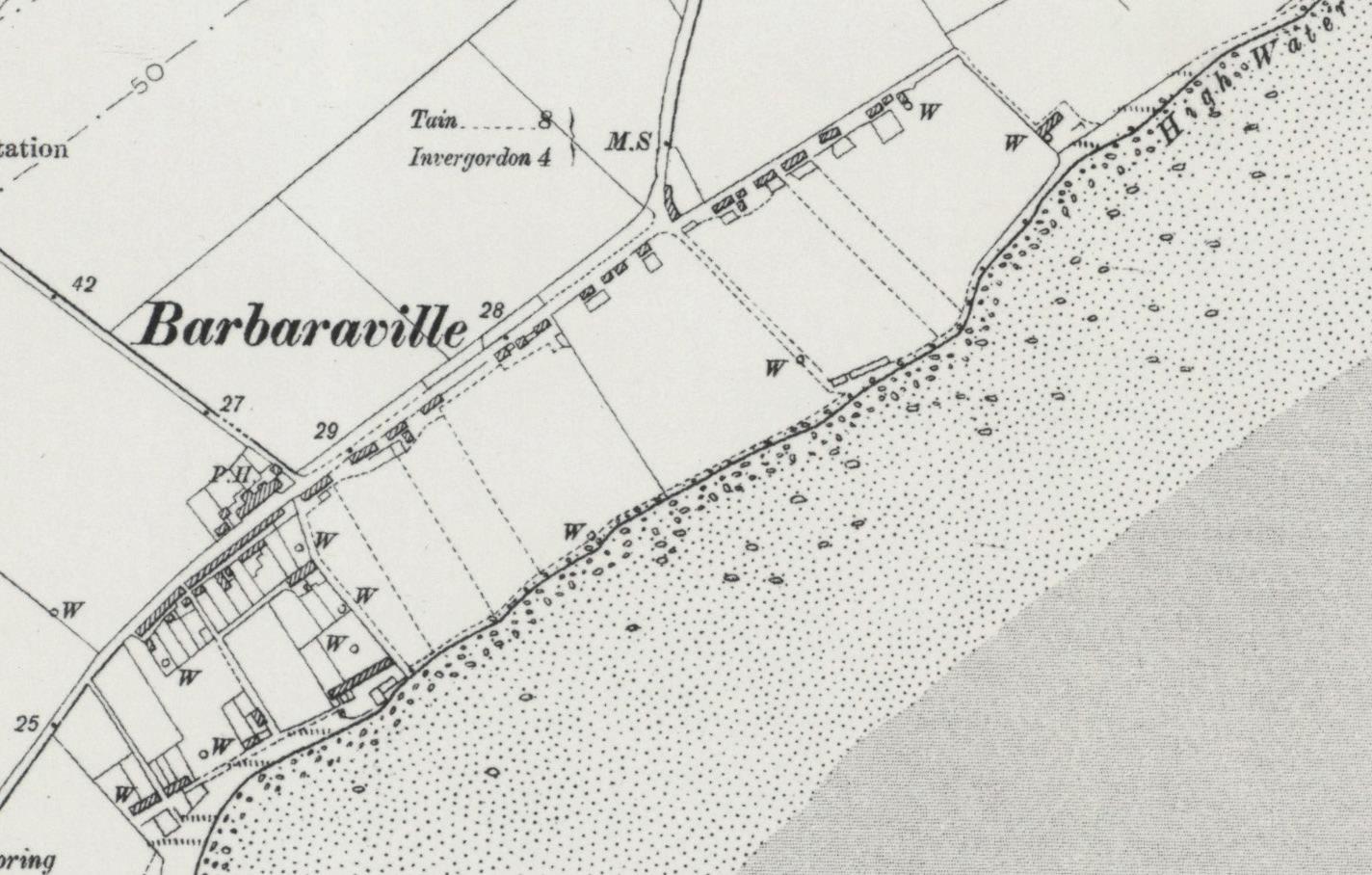

Img. 69. Historical map (1747- 1755) (National Library of Scotland)

Img. 70. Historical map (1830-1880). Agrilcultural landscape on the lower part of the North area of the Cromarty Firth and the Black Isle is visible (National Library of Scotland)

Img. 71. Historical map of Cromarty Firth (1908 - 1918) shows really well the 3 zones of the landscape. Highland, the lowerland with agricultural landscape and the lowland with the feet in the Cromarty Firth (National Library of Scotland)

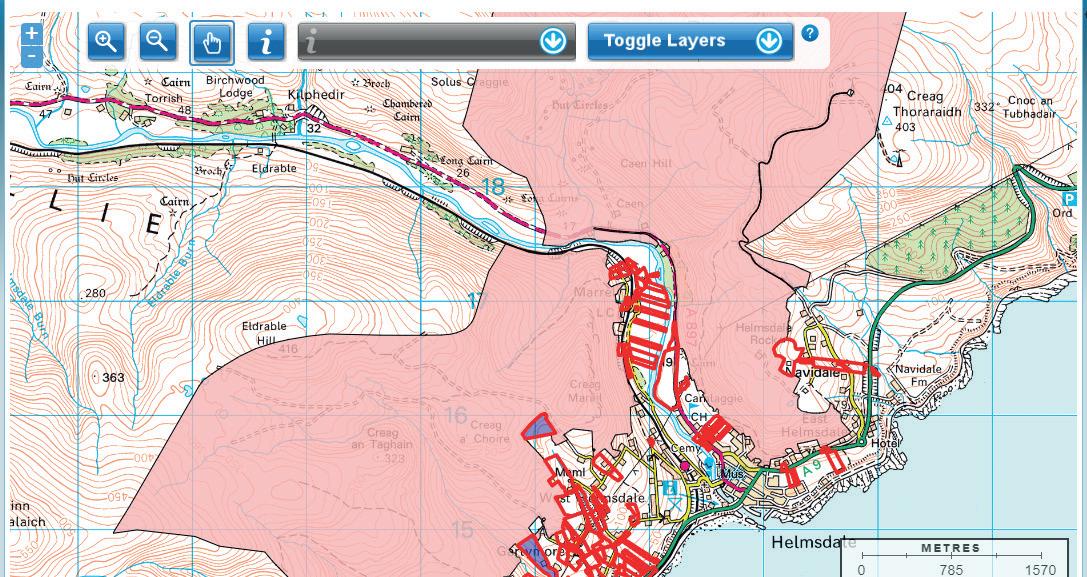

Visible traces of crofting /small holdings

Former fishtraps

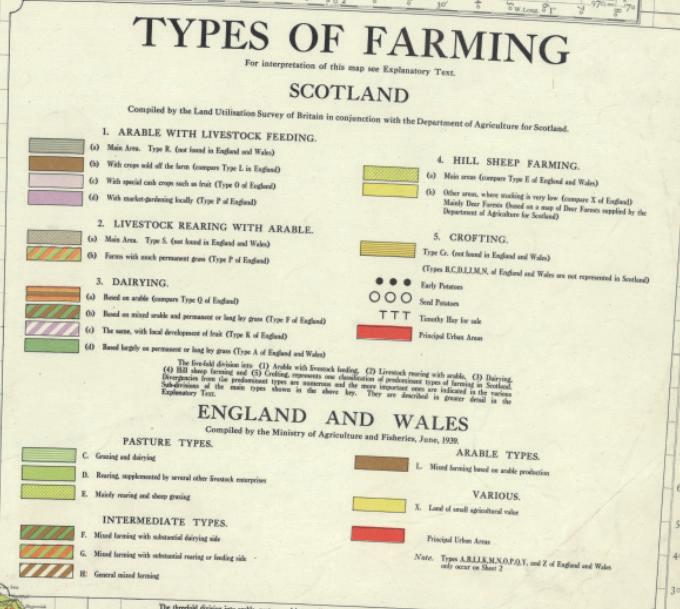

Farming zones 1944:

Hill sheep farming, main area’s

Hill sheep farming other area’s, mainly deer

Crofting

Livestock rearing with arable

Arable with livestock feeding

Img. 72. Histroy of crofts and smalholdings in the area

landscape.

Invergordon : 3.930

Meadows

Rectilinear field and farms

Woodland

Saltmarsh

Golfcourse

Village

Old part of town

Extended parts of town

Graveyard

Industry

Historical building

Traintrack

Road

Img. 74. Alness analysis

Meadows

Rectilinear field and farms

Woodland

Golfcourse

Village

Old part of town

Extended parts of town

Graveyard

Industry

Historical building

Traintrack

Road

Img. 75. Invergordon analysis

The Highland Clearance (1750-1860) remains one of the most controversial periods in Scottish history, marking a period when a new agricultural, economic and social ethos spread across the region.

Rather than continuing to squeeze an income from the small tenant farmer, who often struggled to pay their rent, landowners were enticed by the promised financial ease of agricultural improvements such as large-scale sheep farming (Watson & Dixon, Crofting, 2018). The tenants had to leave their land and make way for the sheep. The year 1792 is also known as Bliadhna nan Caorach, The Year of the Sheep.

A long tradition of communal farming was diminished, leaving landowners to decide what to do with their surplus tenants. Many people in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland were forced from their homes and had to find new places to live without any support. The scale of these clearances was astonishing, both in terms of number of people and the costs involved. Sometime cottages were burned down to force people away (BBC, 2020). This led to mass immigration from the former tenants. People emigrated to North American Colonies, but also to the coastal area’s and the Scottish lowlands (Visit Fort William, 2024).

Other landowners channelled their surplus tenants into crofting townships and smallholdings. The houses and farm were set out in a linear pattern on long thin strips of land (Watson & Dixon, 2018).

The Scottish history, with the Highland clearances, also influenced the area around the Cromarty Firth. Landlord moved their tenants from the hills to coastal regions. The lands the tenants received on the coastal margins were insufficient to support their families, and therefore, they were also expected to become fishermen and kelp farmers (Voices Over the Water, 2015). This has also led to landscape fragmentation.

Crofting is hard work. Around 1880 there was the Crofters’ War with sustained and popular protests against the Highland landowners. Crofters fought for security of tenure (Voices Over the Water, 2015). Since 1886 crofting has its own specific legislation with the Crofter Holding Act (Crofting Commission, sd). Nowadays there is a crofting commission that regulates crofting laws to benefit the crofters and the land. It is independent from the Scottish government (Crofting Commission, 2025). In Scotland there are seven Crofting Counties.

Img. 77. Typicall rectangulair fields of crofting township are visible near Alness on old maps (Source: historical map Scotland)

(Source: historical map Scotland)

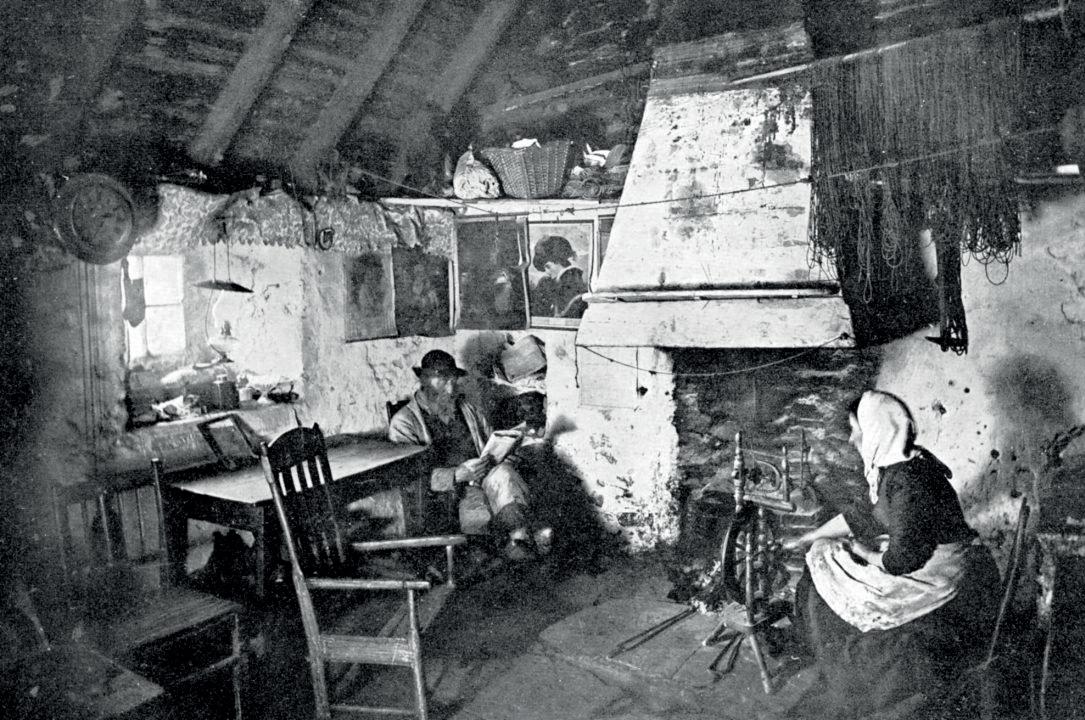

Crofting is a about local food production, preserving cultural heritage and the natural environment. It stimulates individual enterprise among crofters as well as cooperation with the community. Crofting townships consist of individual crofts and shared common land used by the community.

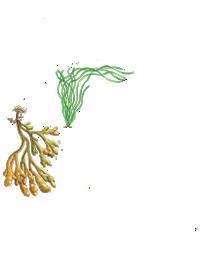

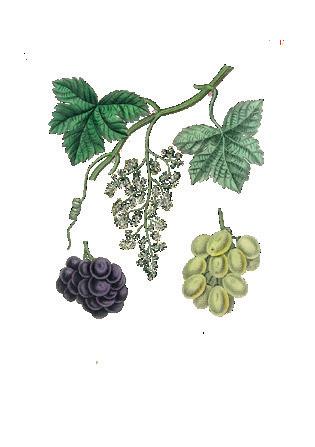

A croft is a relatively small traditional agricultural system in Scottish Highlands and islands. The word croft involves the house of the smallholdings as well as the land itself (Watson & Dixon, 2018). Crofting practices are conserving nature in harmony with ecosystems and the changing seasons. Crofters often supplement their income with fishing, kelp, community related activities like sewing and wool spinning.

Img. 79. Map of crofting counties

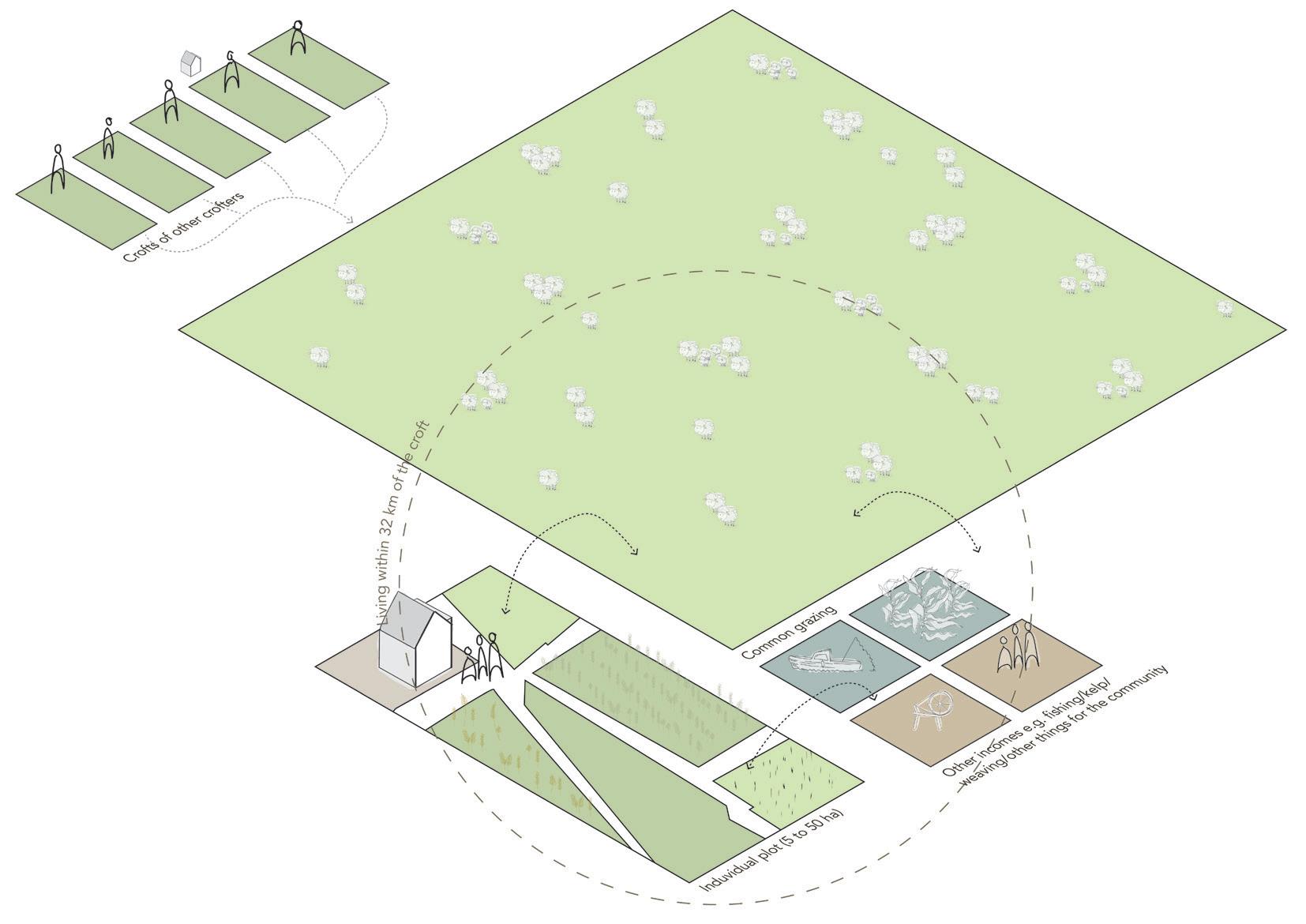

Crofting is defined by three key spatial elements:

- The croft (land): Usually the more fertile land is held in tenancy (The National Trust for Scotland , sd). Crofts range in size, with on average nearly 5 hectares (Crofting Commission, sd). Various crops are grown, primarily for self-consumption. The land is arranged in a linear pattern on long, thin strips, which may or may not have a house on it.

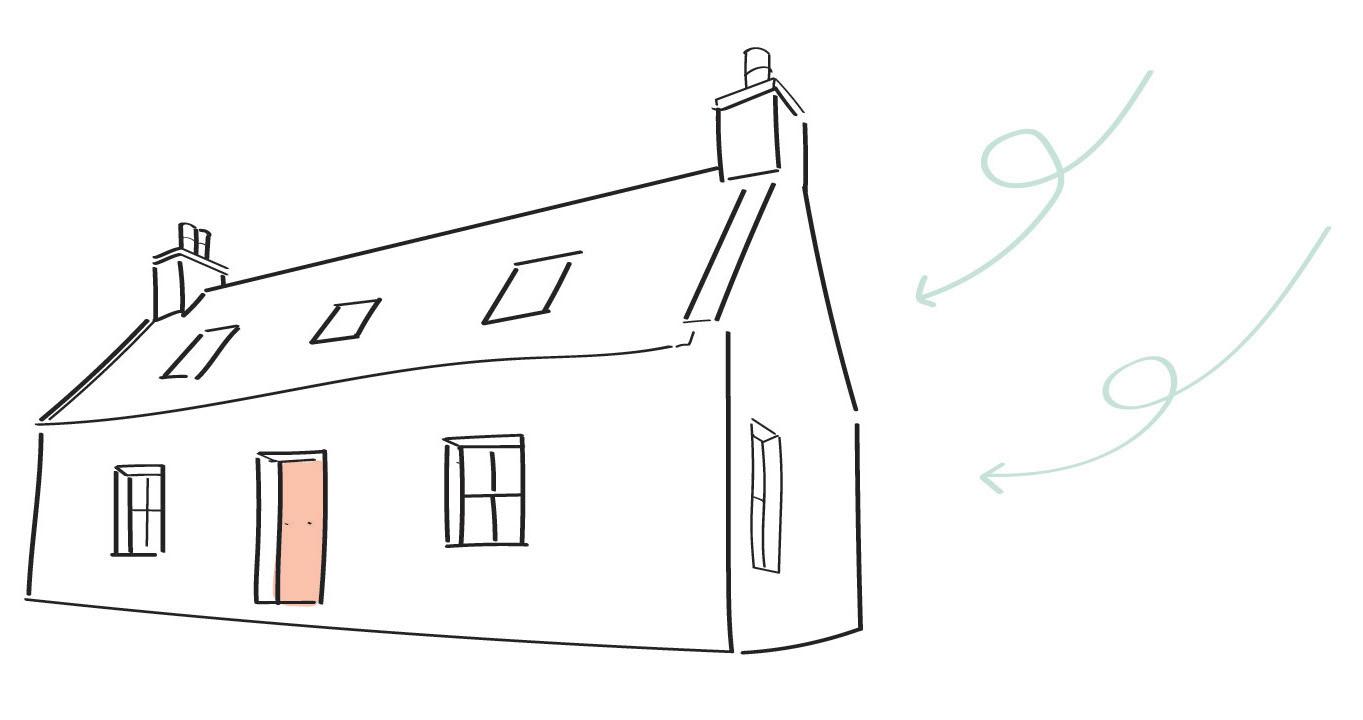

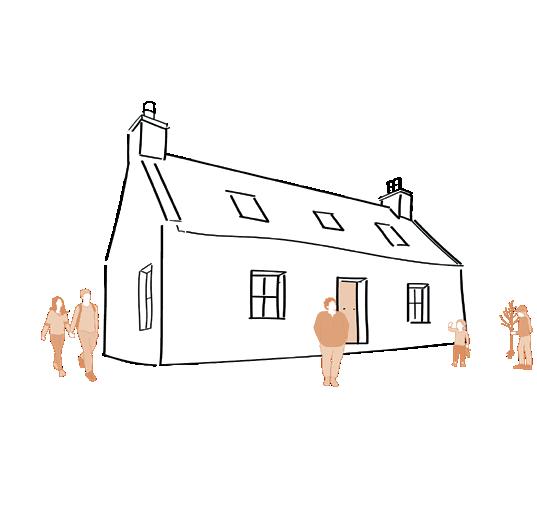

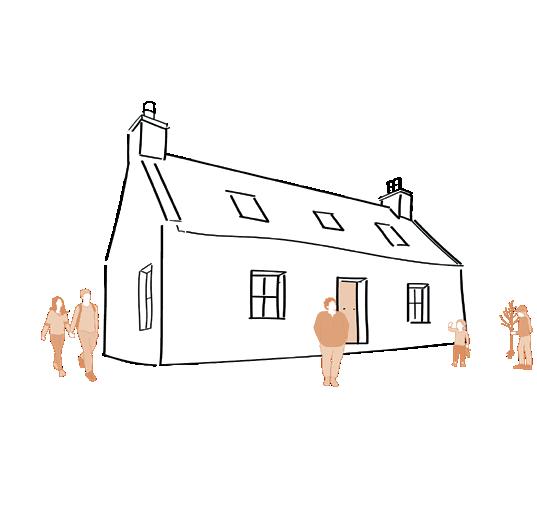

o A croft (house) is typically white-washed, with a single front-entry door and a couple of windows on the warmer, less windy side. Traditionally, the house is a symmetrical single-level building with gable roof and chimneys on both sides.

- The common grazing: These are large areas of land used by crofters and others who have the right to graze stock on that land. This land is usually less fertile ground such as heathlands, grasslands, rocks and marshes, as well as extensive forest areas .

- Settlements: These are small settlements with typical whitewashed modest houses.

Img. 84. Shematic principle of traditional crofting

The key principles of crofting can be summarised as follows:

- Sense of community. Each crofters takes an interest in the commons. Together they belong to a rooted community in the area they all work and live on.

- Preserving cultural and natural heritage with a connection to the location. By listening to the needs of their crofts and land, the crofters are emotionally entangle to their site. The underlaying landscape structure works as a guide for agricultural choices.

- Local food production. Creates a sustainable food network, with food as a connector.

Despite an ageing population of crofters, there are also young people eager to embrace crofting (Haig, 2015 ). In some regions of Scotland crofting communities can still be found. To illustrate the variety of crofting communities and the spatial conditions, two case studies of exiting crofting communities have been conducted.

Img. 85. Source: The Newstatesman, 2015

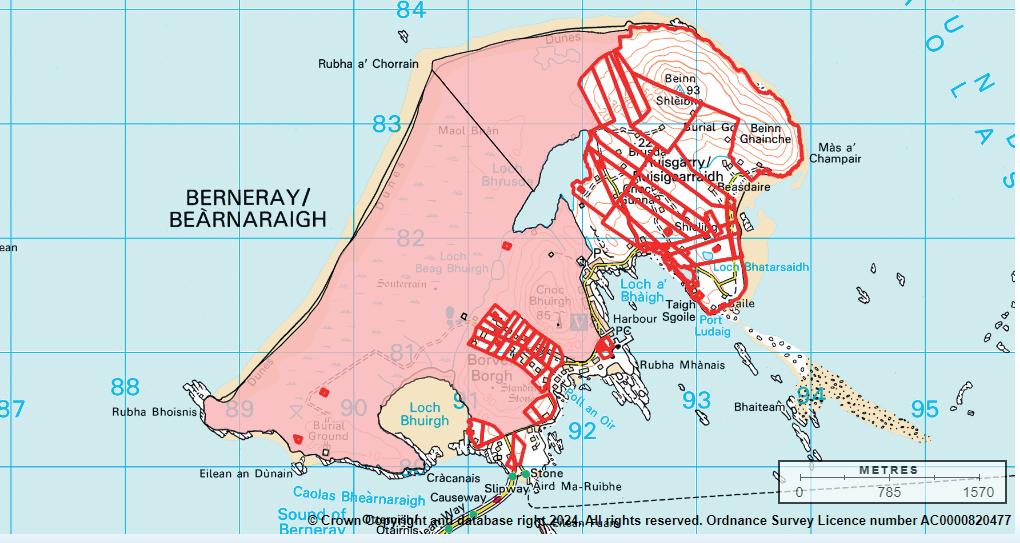

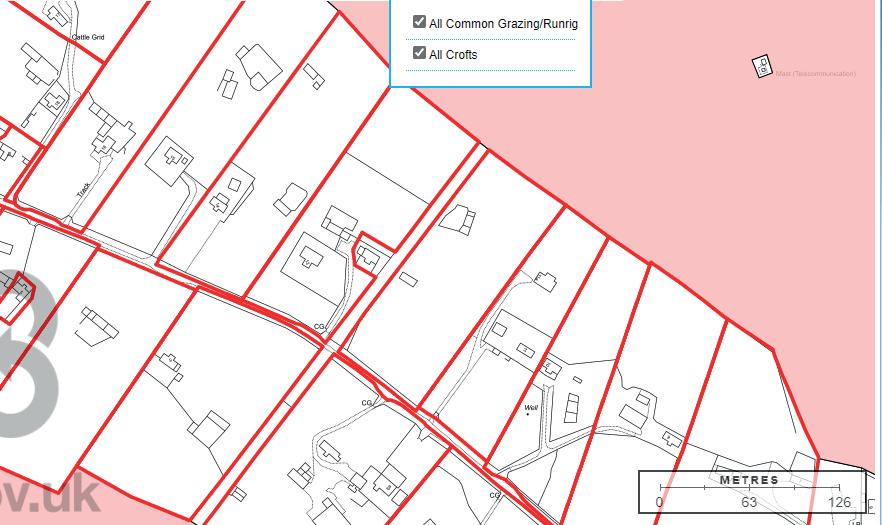

Berneray

Berneray is an island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, covering an area of over 10 km2. Almost the entire island is used for crofting and under the Crofting Act. The crofting practices also encourage wildlife on the island. The

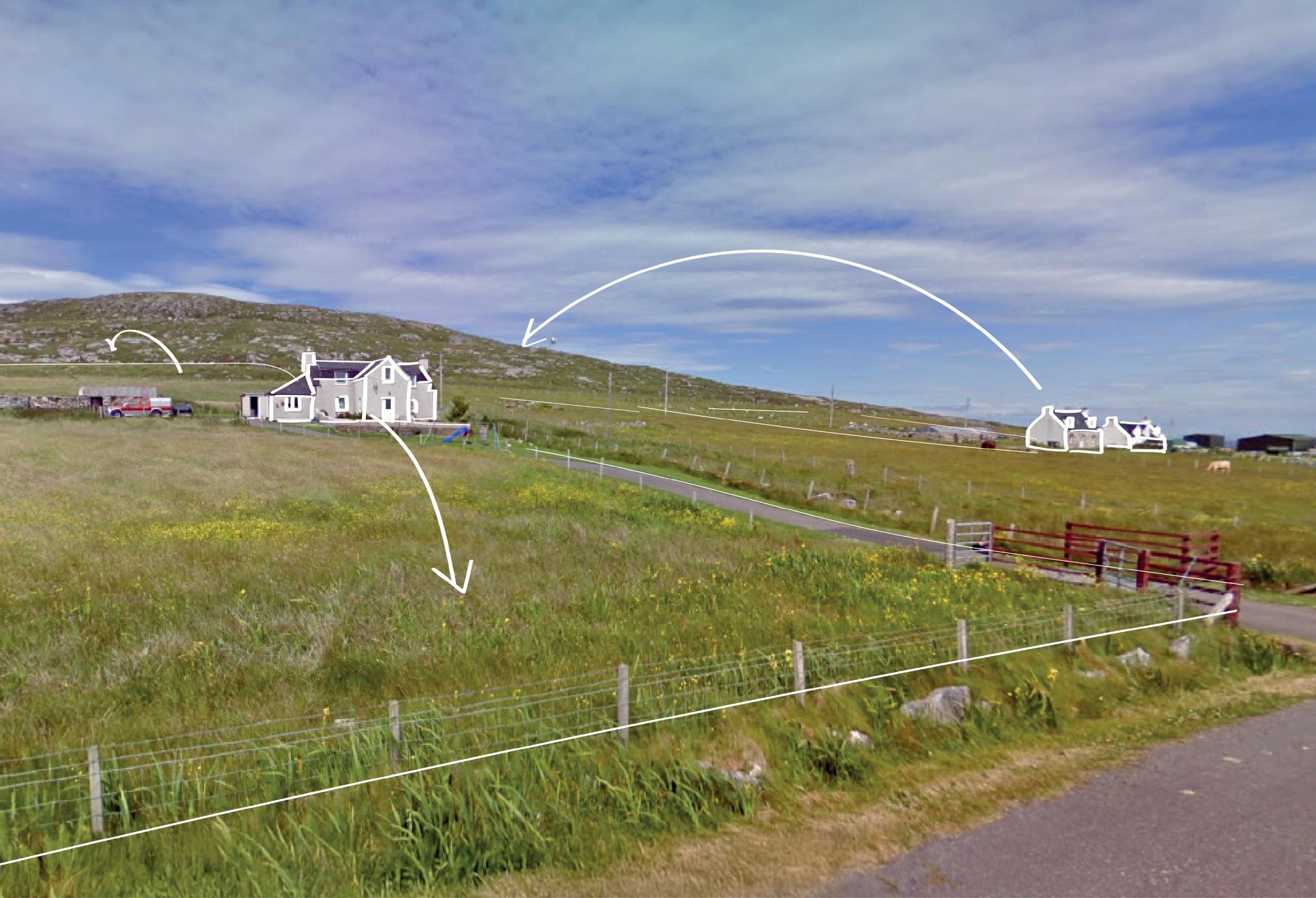

57 crofts on the island have an average size of 4,2 hectare. The ratio croft to common land is 1:2,7 on the island. The rectangular plot structure and the crofters house are very visible.

Img. 86. Crofting community on Berneray Island (The Crofting Register, consulted 8-11-2024)

single-story symetrical buidling with gable roof

Doors and windows situated on the sheltered side

Chimneys

White plaster outside work

Other crofts

Common

Croft

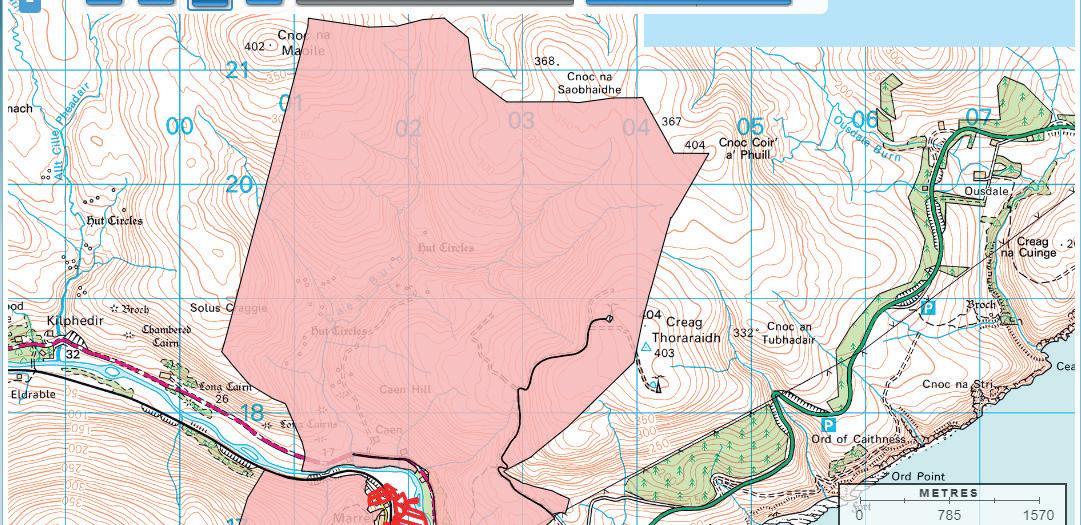

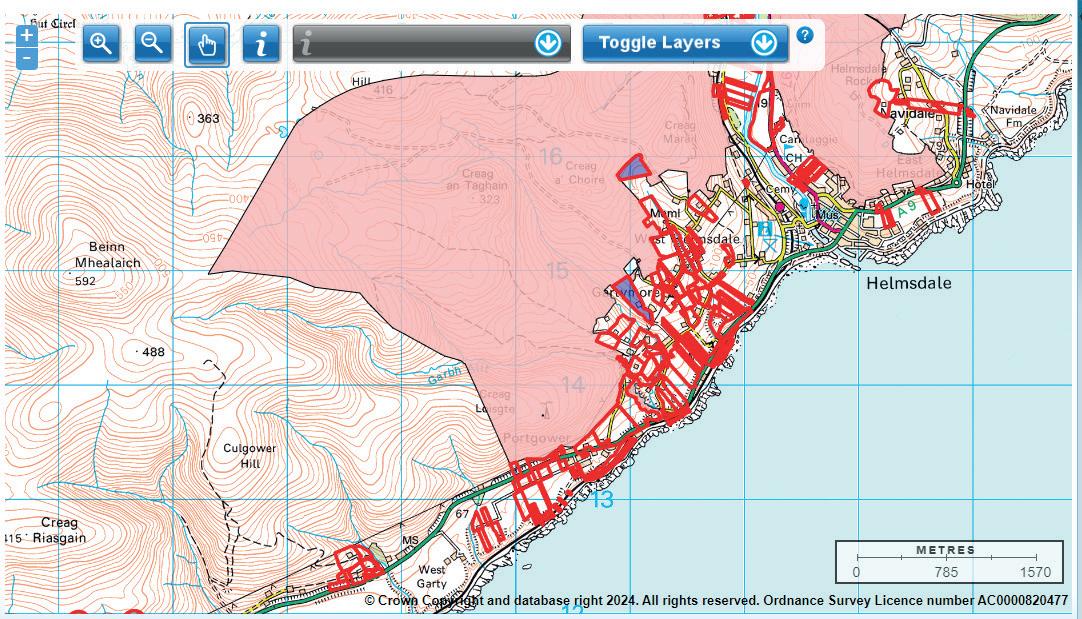

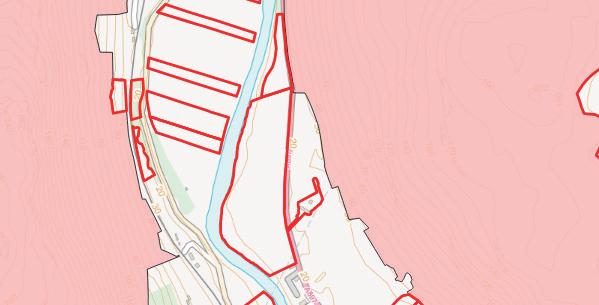

Helmsdale is a settlement on the east coast of Scotland, located 60 km north from Alness. The 90 crofts have an average size of 2,5 hectare. The ratio croft to common land is 1:9,8 in

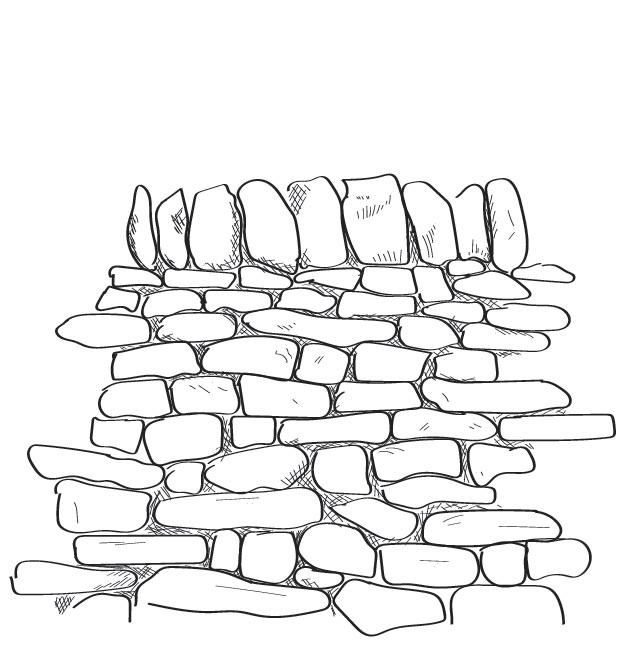

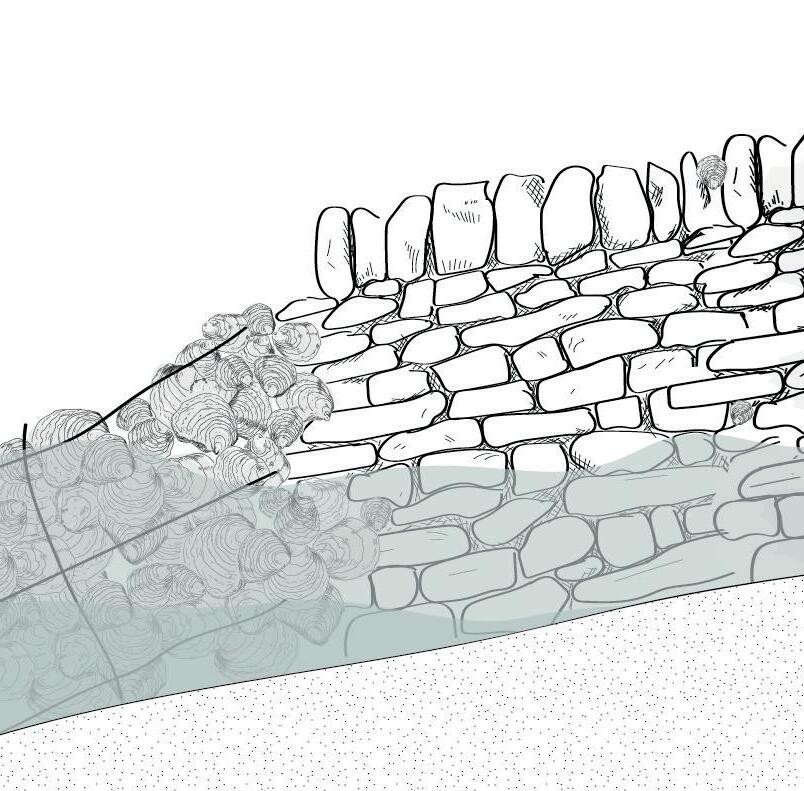

Hemsdale. The drystone walls form the division between de crofts. Those ecological important structures embrace the natural relation to the place.

consulted 8-11-2024)

Dry stone wall structure top layer vertical orientated horizontal dry stones layers as a base

In conclusion, a crofting community is a cohesive social and spatial system. The community has a shared interest in both the commons and in the knowledge of the fellow crofters. It is based on three principles. With the sense of community, everyone has their own share in the crofting community. Another important aspect of crofting is that it is a system that lives in great interaction with the surrounding land. When you take care of it, the land takes care of you. Lastly, crofting is about food. Food is a connector, it brings people together and connects to the local food.

Crofting is a system that establishes direct and indirect relations to the landscape and her people.

teractionwith the surroundingarea

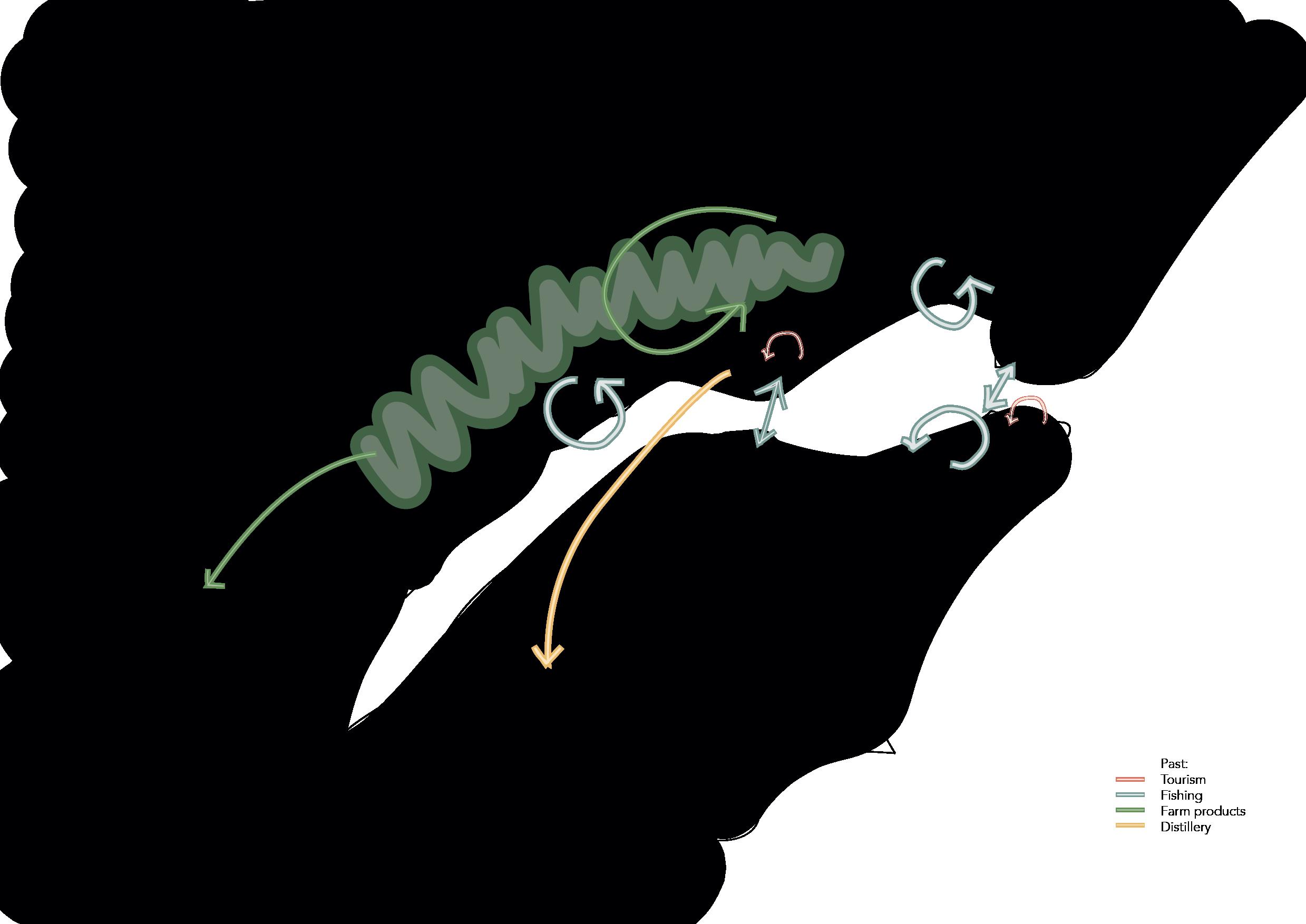

In the 17th century, agriculture was essential in Firth area (Ash, 1990). On the water, Alness and Invergordon had a booming fishing industry. The economy was very local, adapted to the local surroundings and seasons. However, this began to change over time. Monoculture is currently prominent in the large-scale agricultural landscape.

Img. 95. Historically the Firth was more a local economy

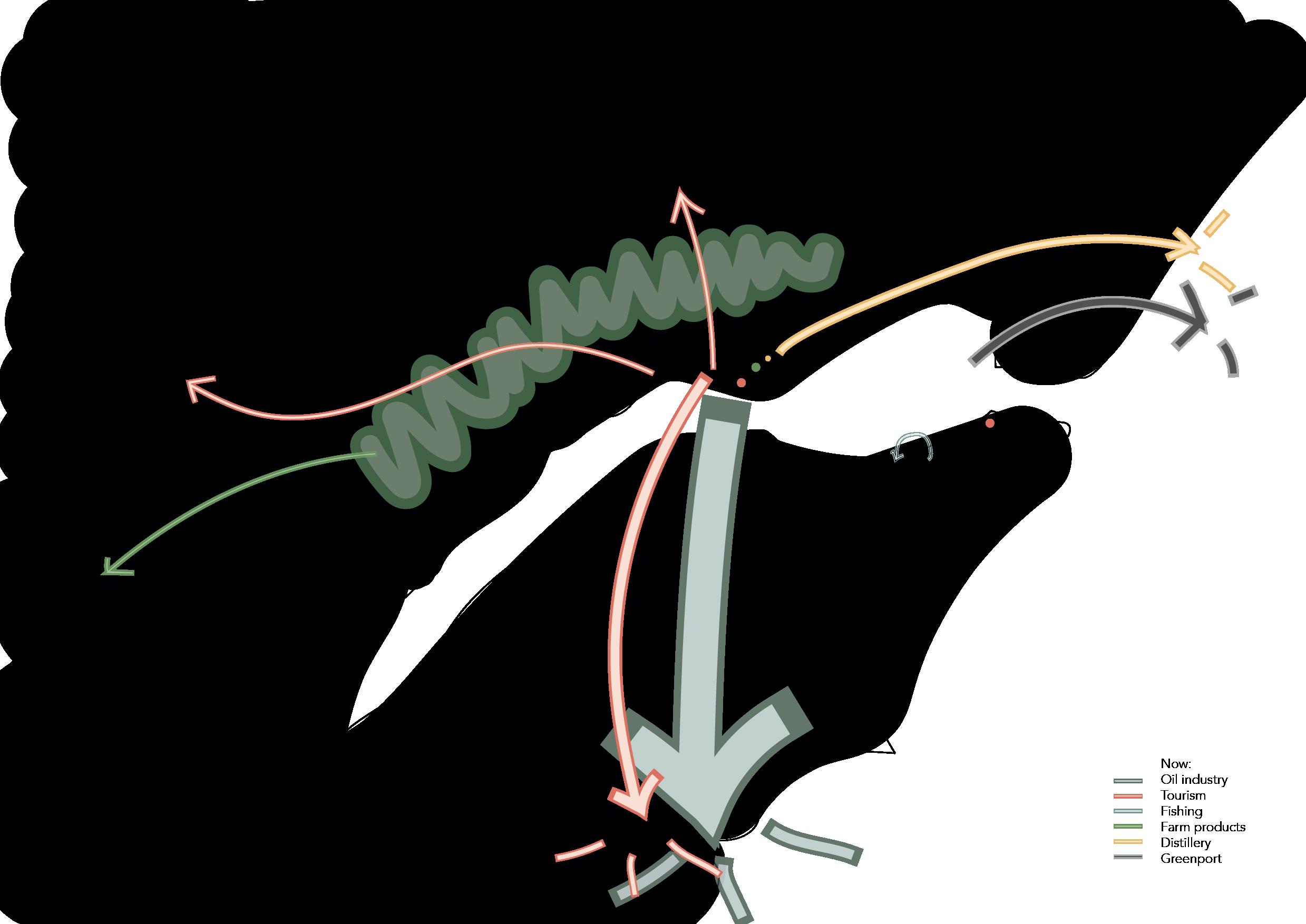

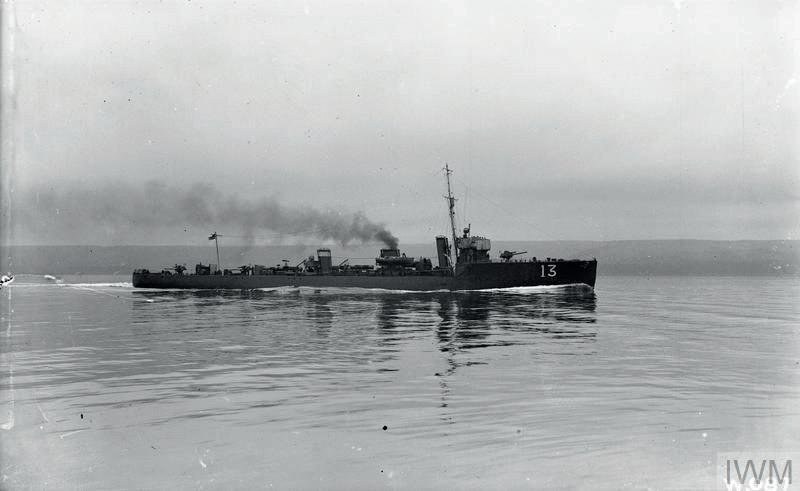

In the early 1900s, Invergordon became an official naval base, chosen for its suitable channel depth and sheltered position. During both World Wars, the harbour and storage oil tanks were in full use of the Royal Navy (Ross and Cromarty Heritage Society, 2024). The global importance brought infrastructure that created harsh boarders along several places along the Firth.

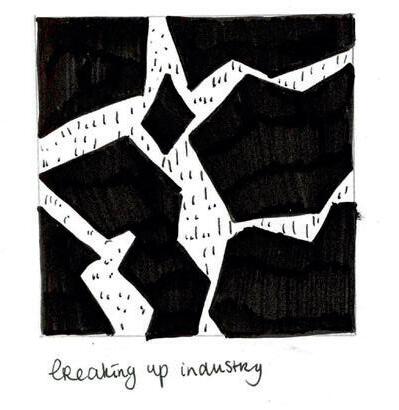

After the World Wars, the oil industry established itself along the sites of Invergordon. Over the years, the industrial sites reclaimed several pieces of land, while economically growing. However, the local community did not benefit economically, as the oil rig employees were guest workers from other places.

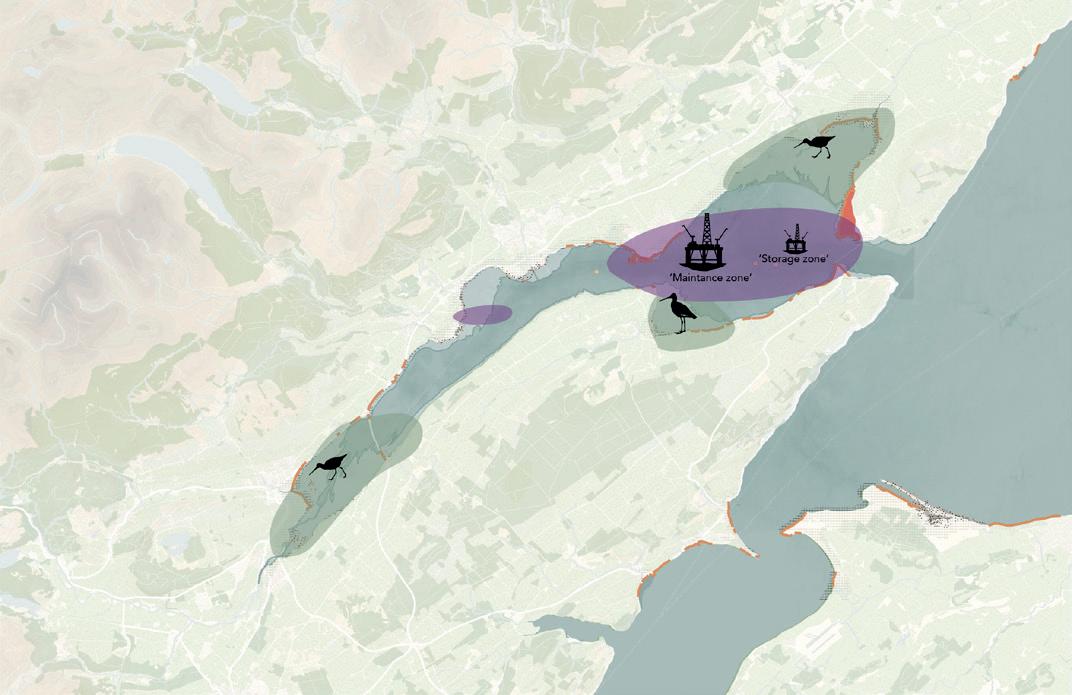

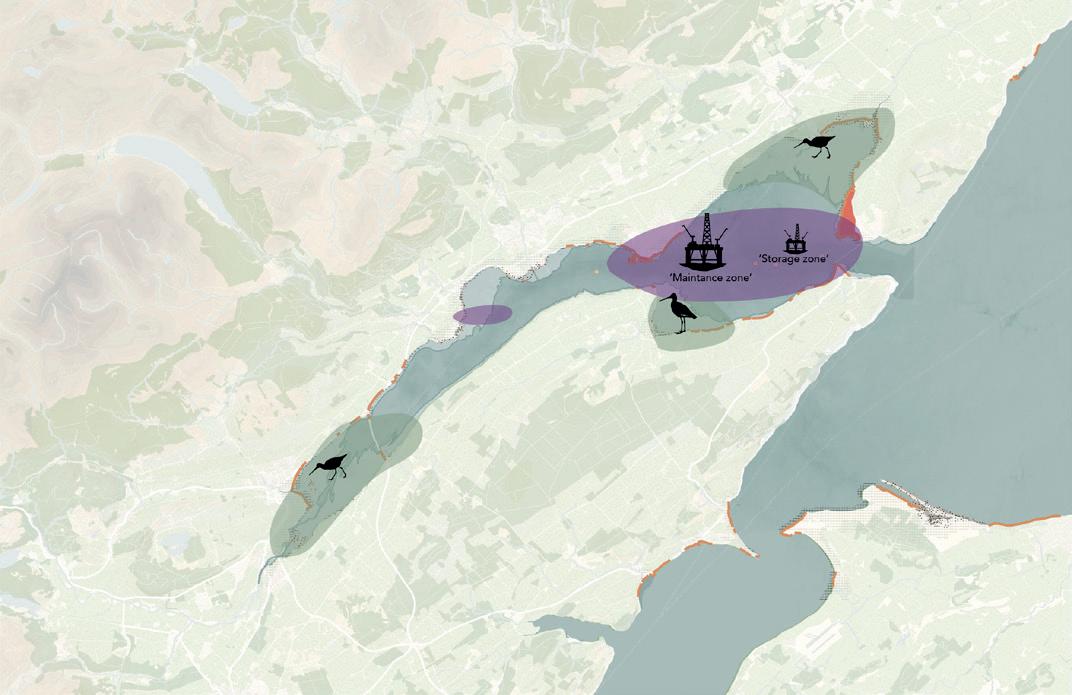

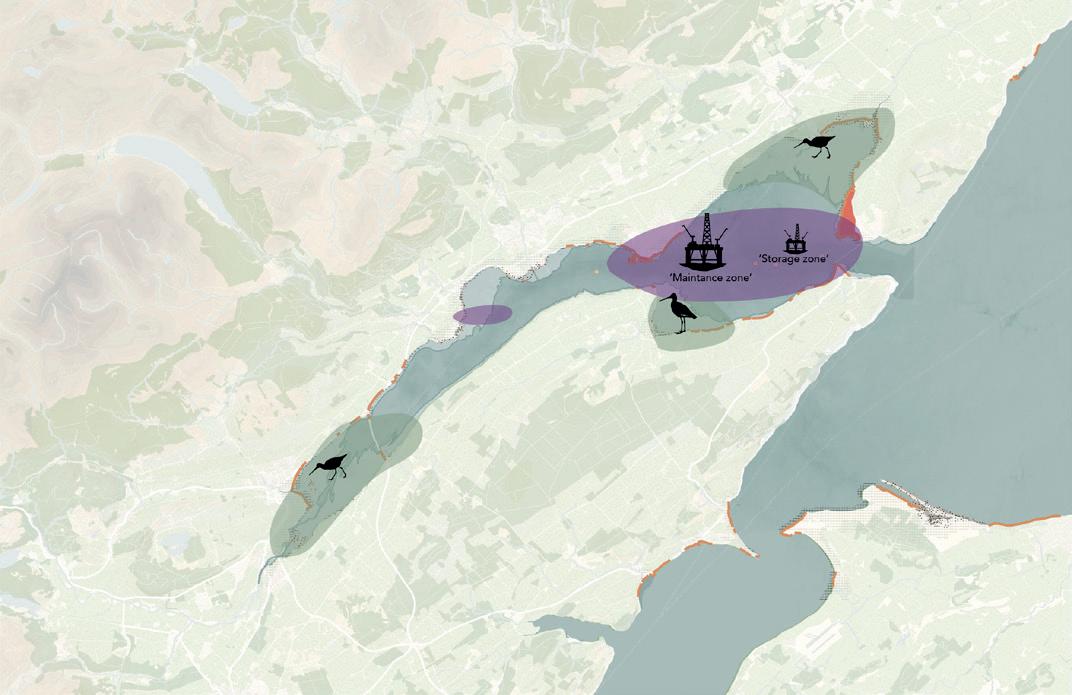

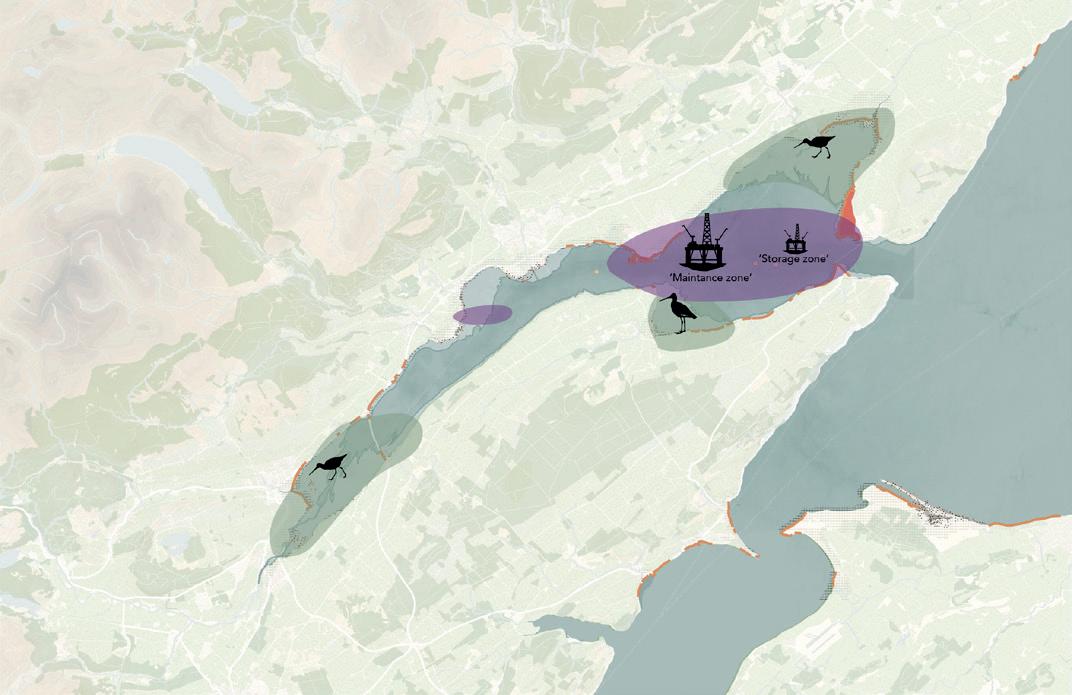

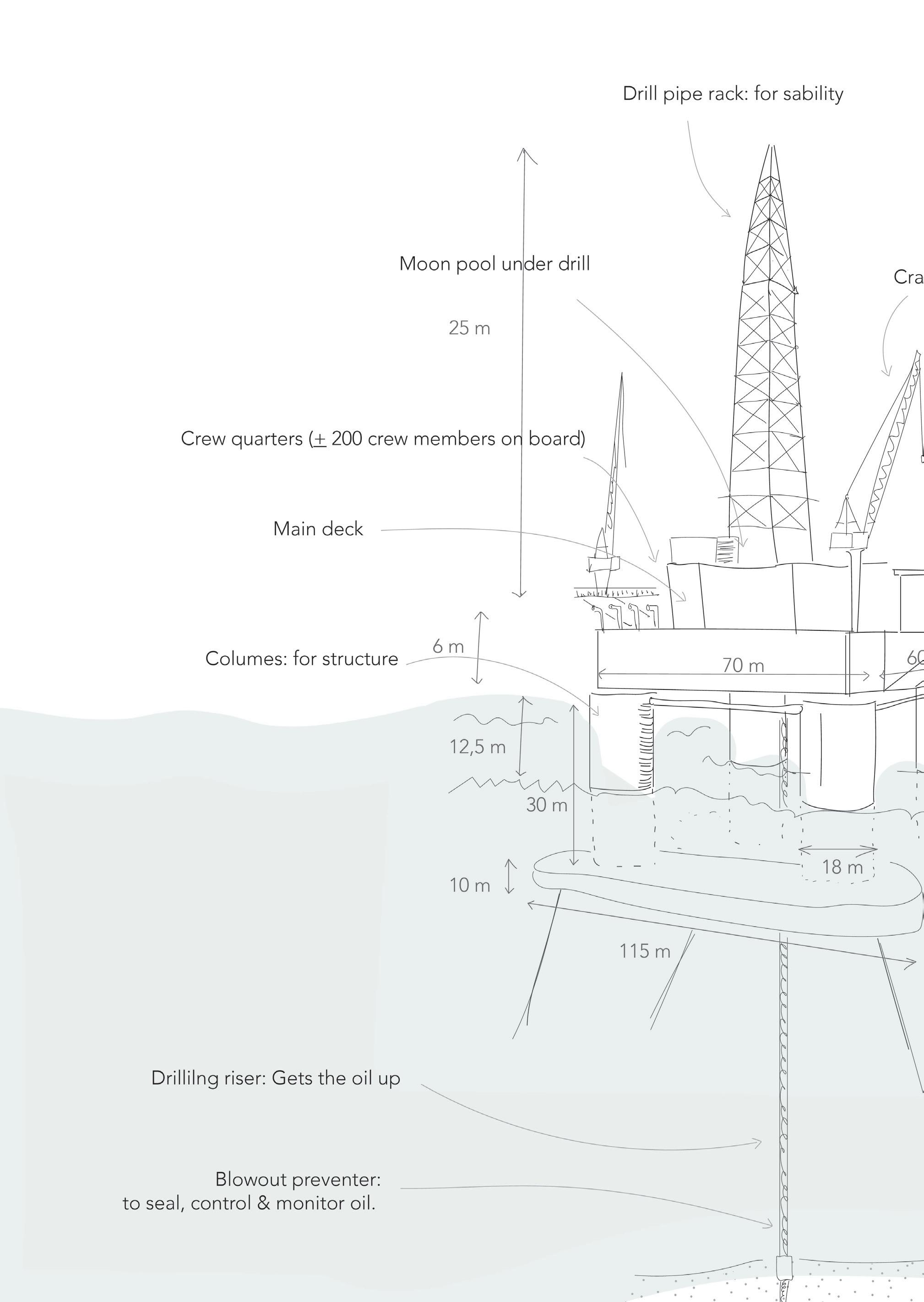

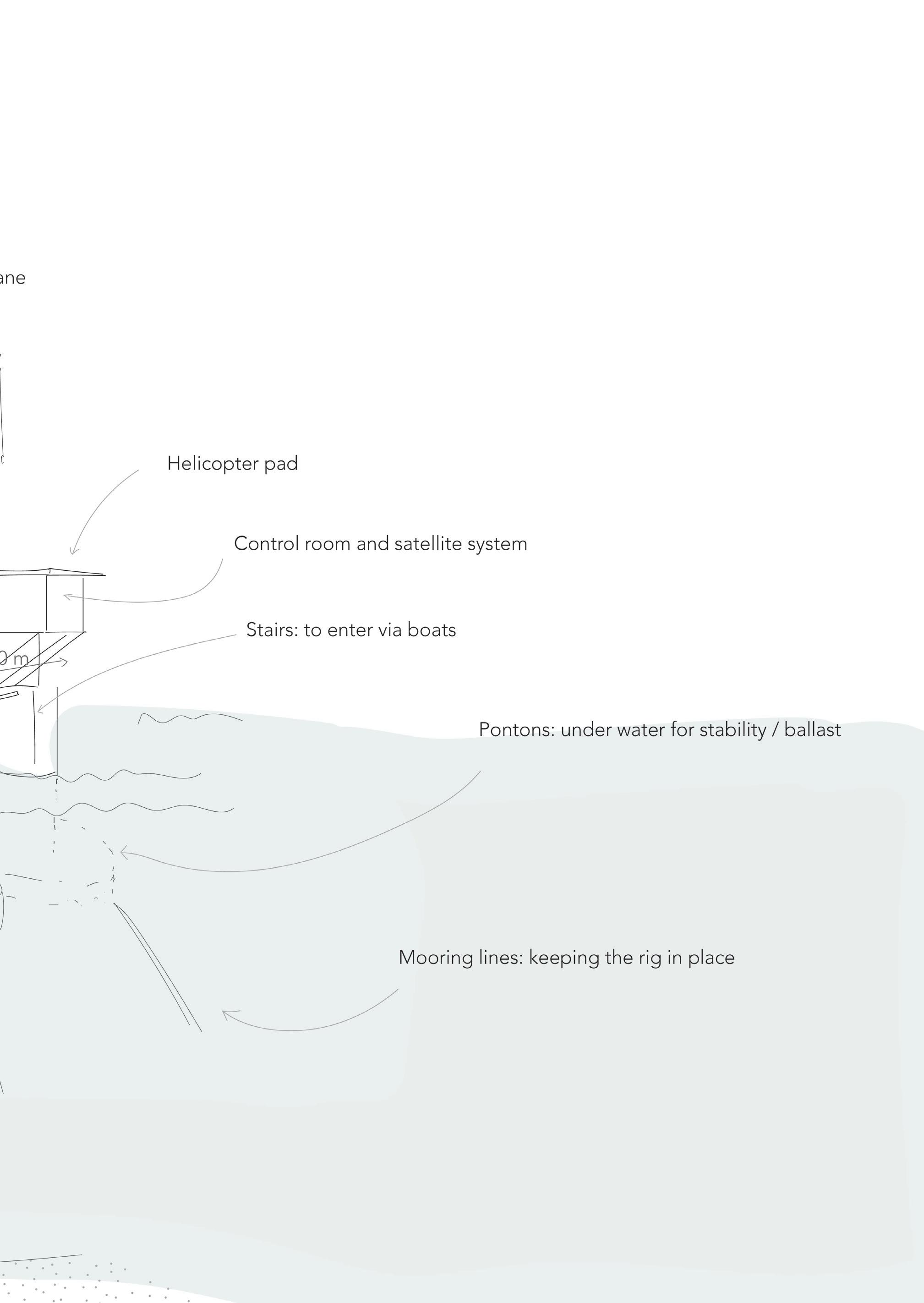

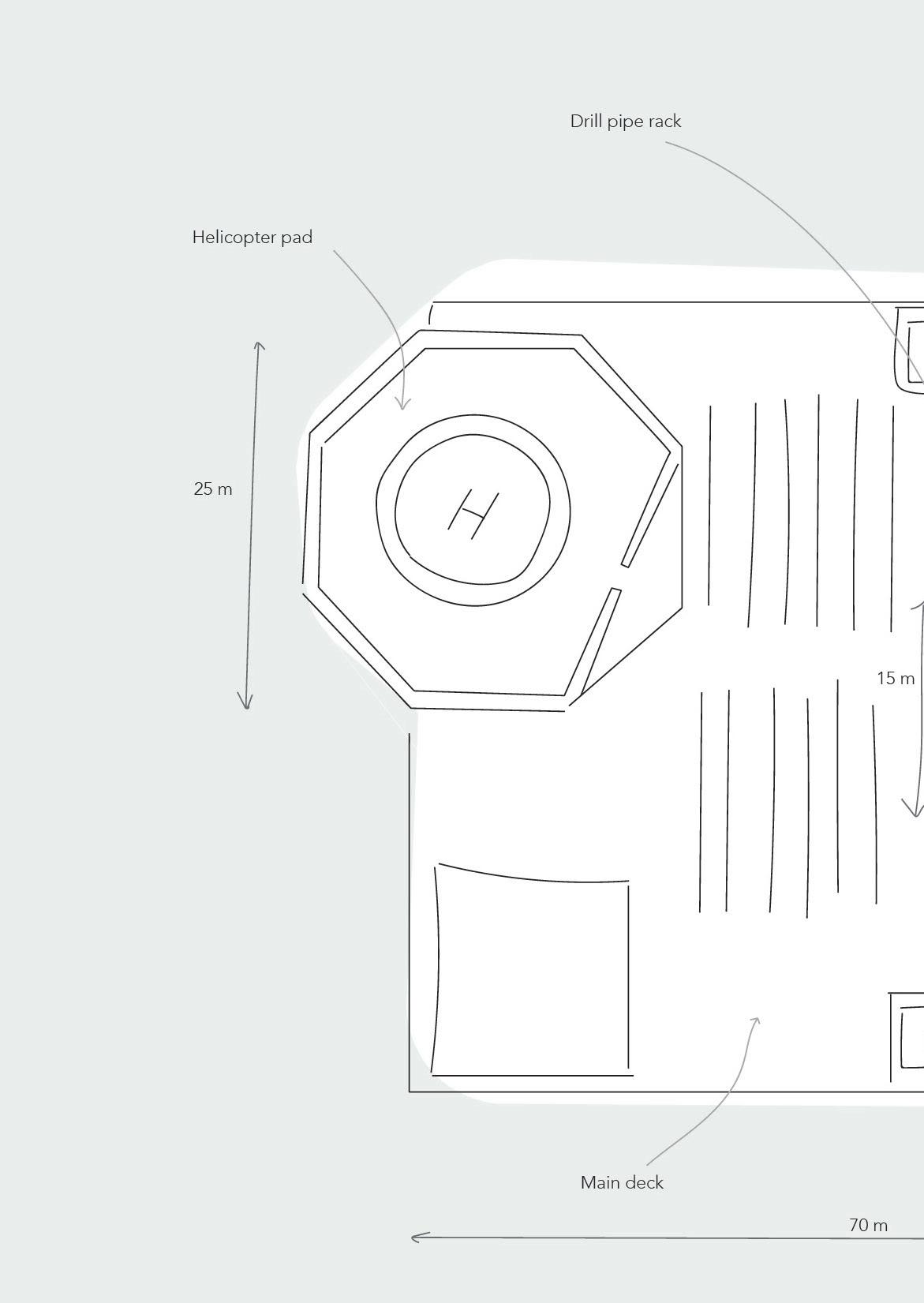

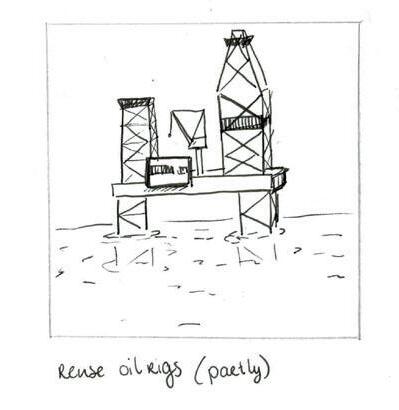

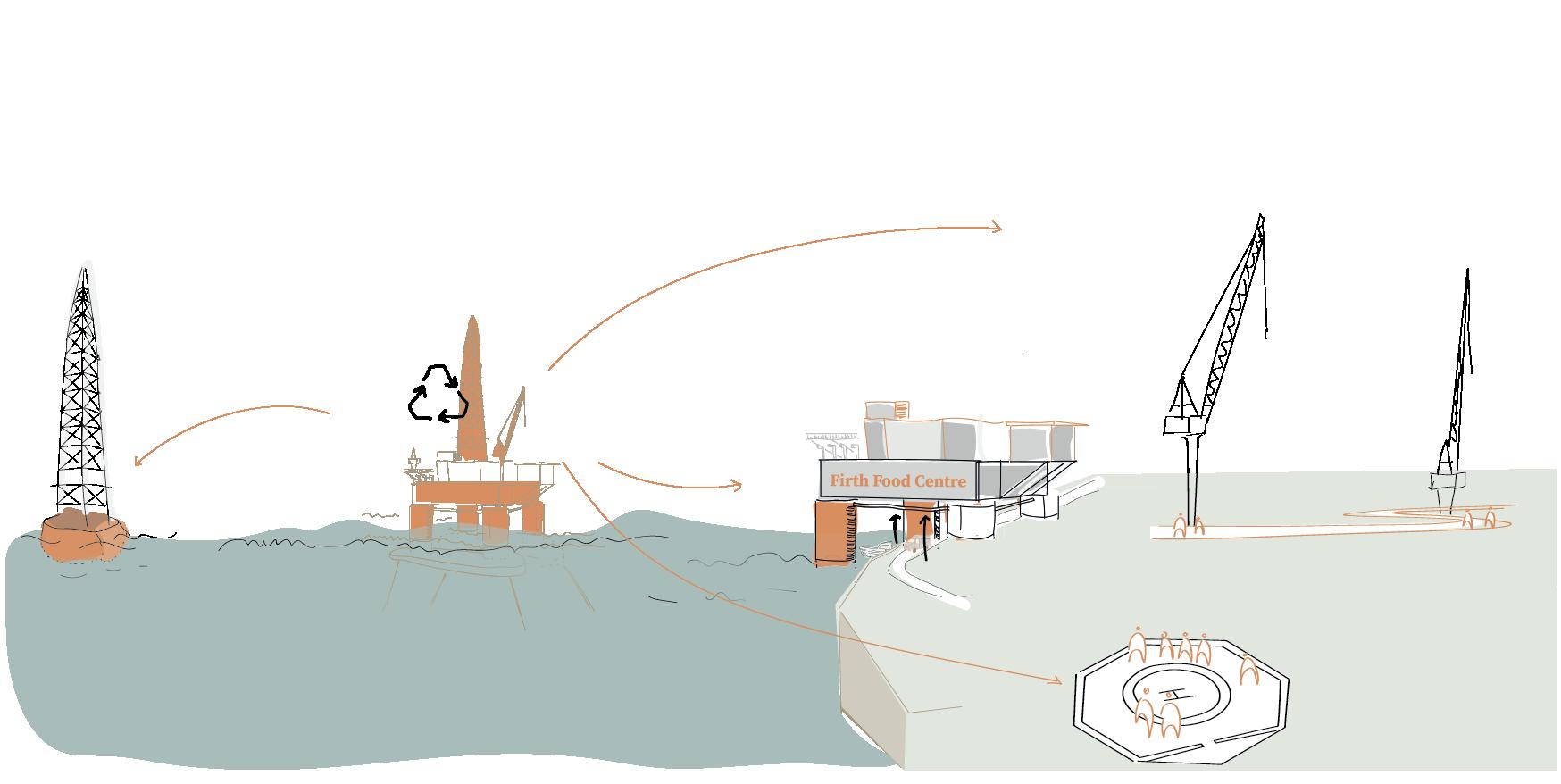

In the 20th century, the Firth became a vast parking lot for redundant oil rigs. The semi-submergible oil rigs drill for oil in the North Sea when in use. When not in use or in need of repair; they are towed into the Firth with vain hope of returning to the oil fields. This location is the only decommissioning yard in Scotland. However, the rigs remain in the Firth, as dismantling is expensive and risky. As a result, long lines of degraded oil rigs rise above the horizon of the Firth.

The oil industry has left its mark in the Cromarty Firth region, both on water and on land. It has become the overshadowing part of its identity. It has become Scotland’s oil rig graveyard.

Global economy

Img. 96. Then with the industrialisation the economy became global and not specifically providing the local inhabitants

Img. 97. Oil around Scotland and the transport to the main land

Img. 99. Invergordon Port where the rigs are repaired (British ports)

100. Three tugboats move the oil platform (Youtube:TheMarcosparco)

Img. 103. Structural elements of a semi-submersible oil rig

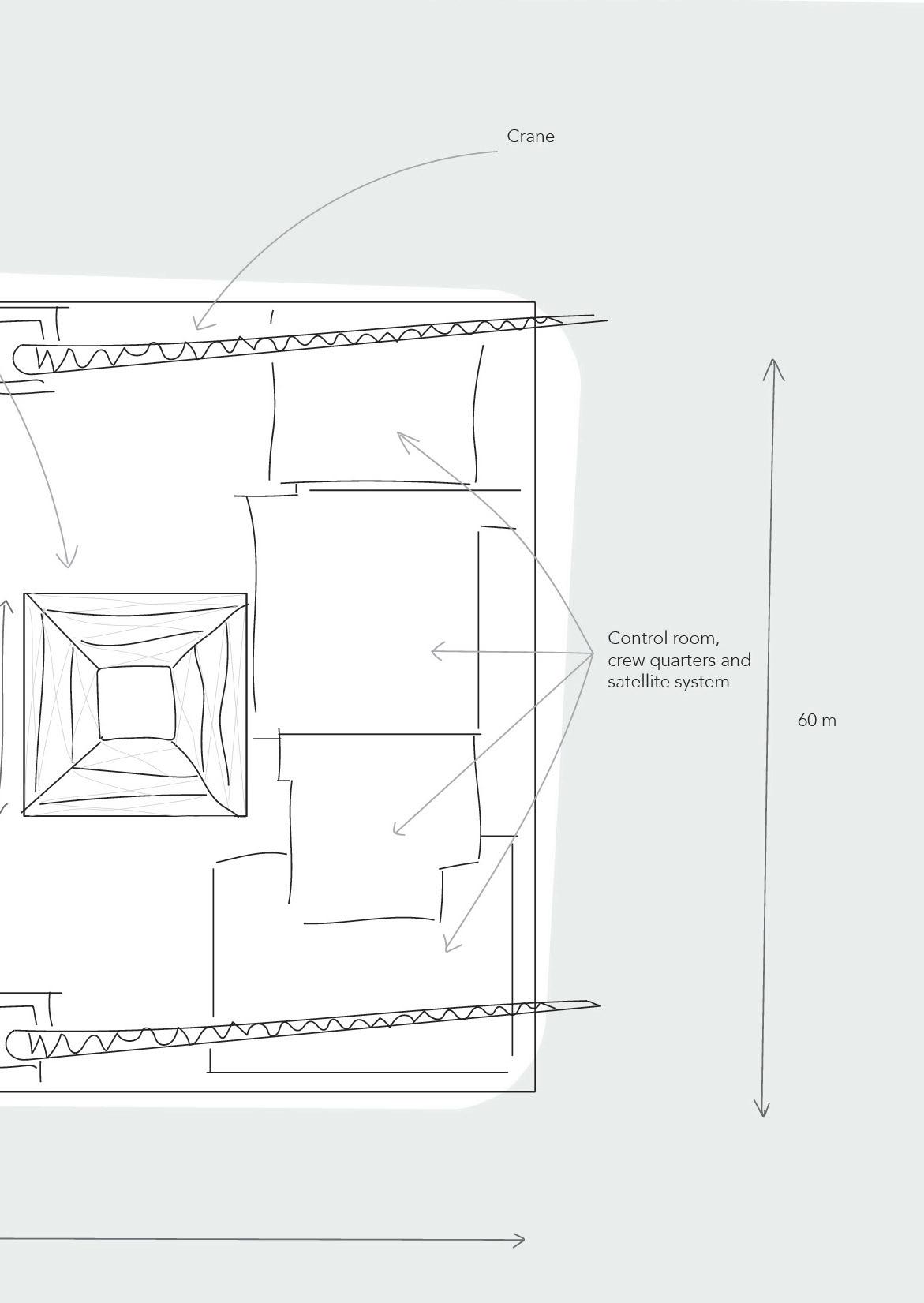

Img. 104. Top view semi-submersible rig

The Cromarty Firth region has had several identities during its history.

Since people first settled here, the area has always been agricultural. The landscape, with its relatively flat and gentle slopes created during the glacial period, make it suitable for farming. Traces of former crofting activities have also been found in this area. The smallscale communal agricultural system is deeply rooted in the Scottish culture, but this has been lost in this area due to agricultural scaling up.

Since the 19th century, there has been another shift in identity, driven by the oil and naval industries. This industrial character still dominates the character of the region, both on water and along the shorelines.. The parked oil rigs rise

above the waters of the Cromarty Firth. The emotional and natural connection are in the distance. These elements are currently not connected to each other and lay next to each other. The firth has become a harsh backwater.

To make the Firth the beating heart of the area again, relicts will be used to respect the local identity while moving towards a post-oil period. This new phase aims to balance social, intertidal and economical aspects of the firth bringing them more in touch with each other. The Cromarty Firth is gaining a new identity; physical and emotional ties are being restored by giving new life to relics from the surrounding landscape.

Img. 105. The identity of the Firth by the 3 themes. The economical site is currently overpowering and the different parts are not connected to each other. It is not a whole identity. The focal shift will focus more towards a coherent and connected area.

Landscape what now is known as the area of the Cromarty Firth was created by Giants

Sutors are the oldest feature of the landscape

Alness triving centre for trade and commerce

Shipping

Img. 106. Timeline of development along the Cromarty Firth

Img. 108. Collage of the industralised firth

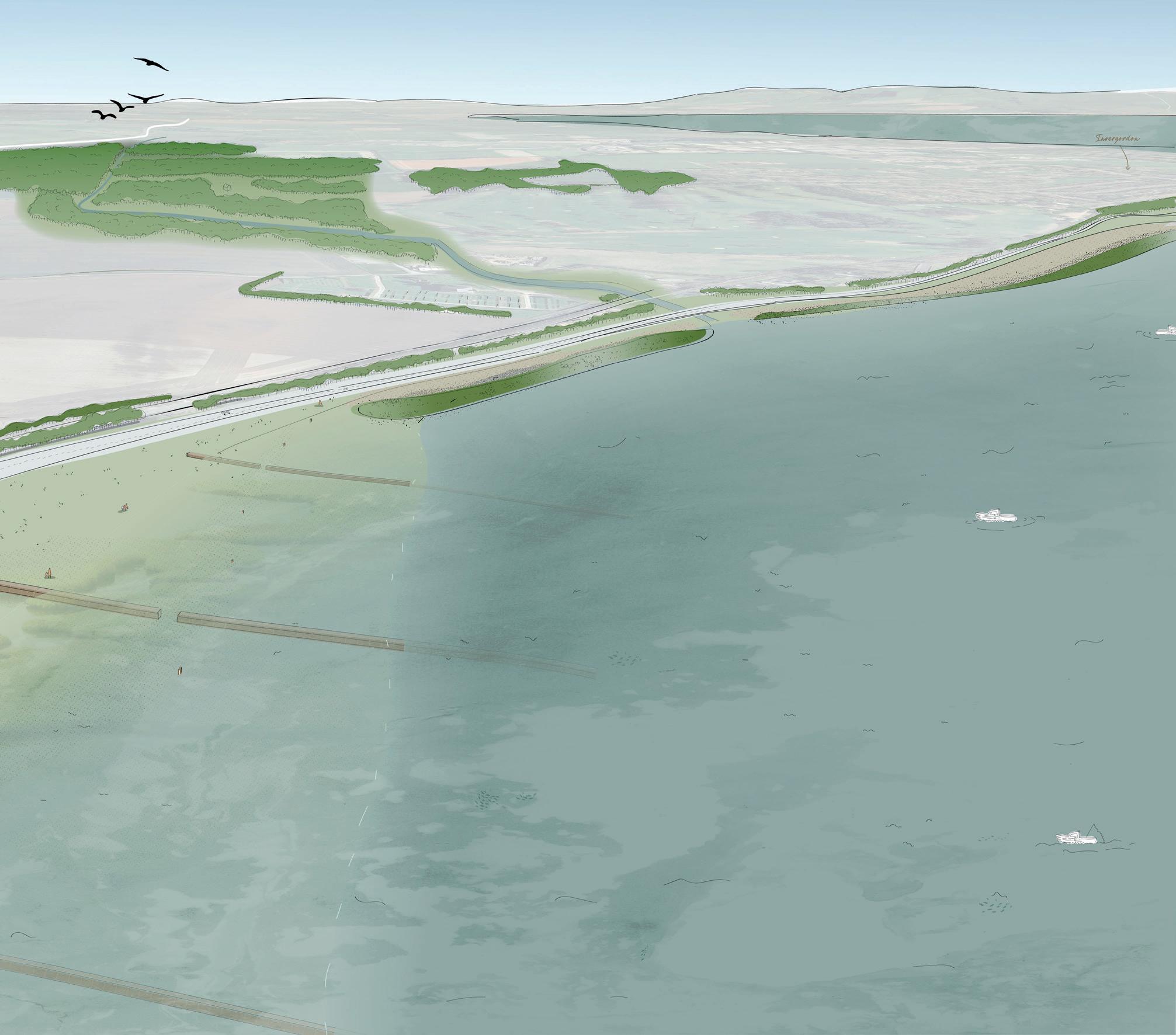

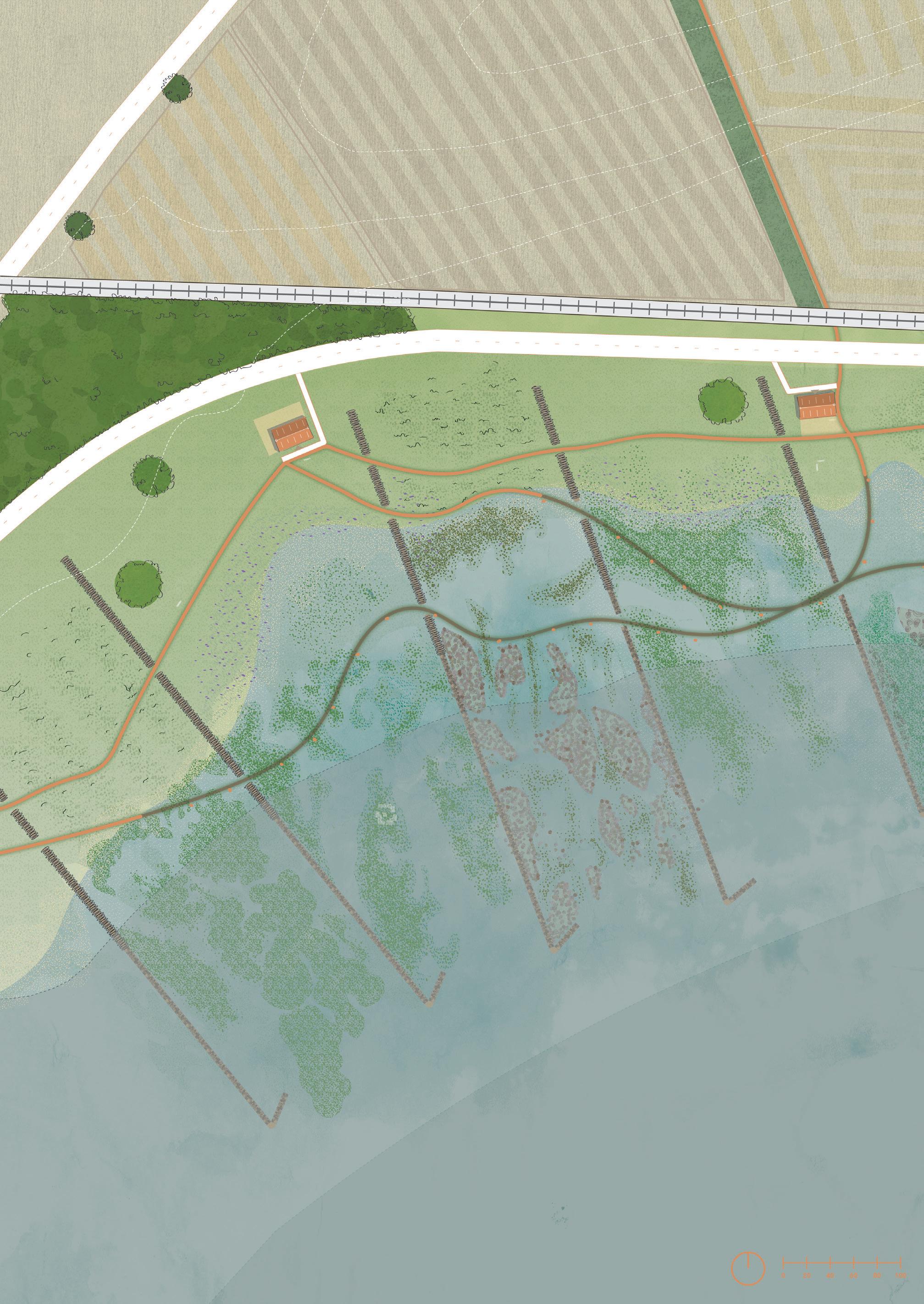

Where the water and the land meet, emotional and physical connections will be rewoven between people, the firth and the landscape itself.

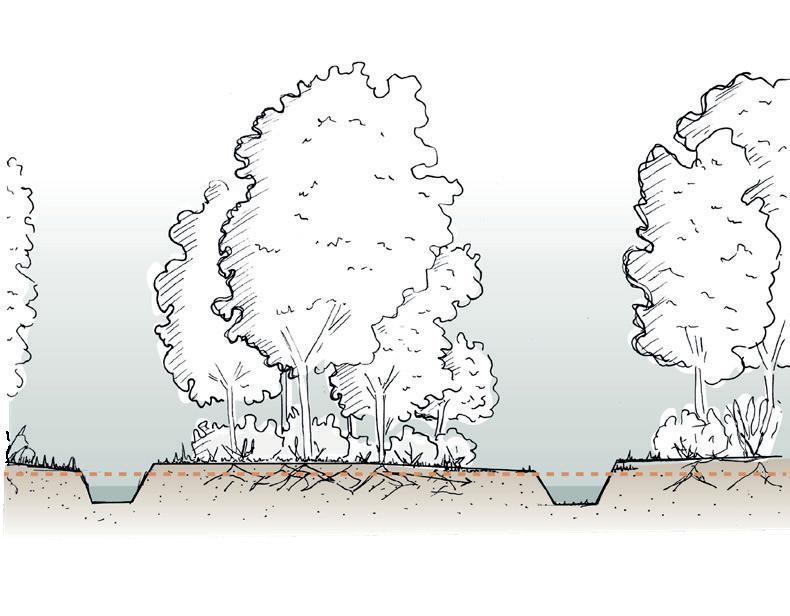

Crofting offers an ideal way to reconnect with the Cromarty Firth, as it is closely tied to the local conditions. The renewed approach honours the tradition while embracing the evolving relationship between people, land and water for a resilient future.

In this new coastal crofting approach, the water will become the central connector. While traditional crofting has always been land-focused, this concept reinterprets it. The Cromarty Firth will serve as the commons that connects everything, creating a dynamic environment with a variety of species and interactions.

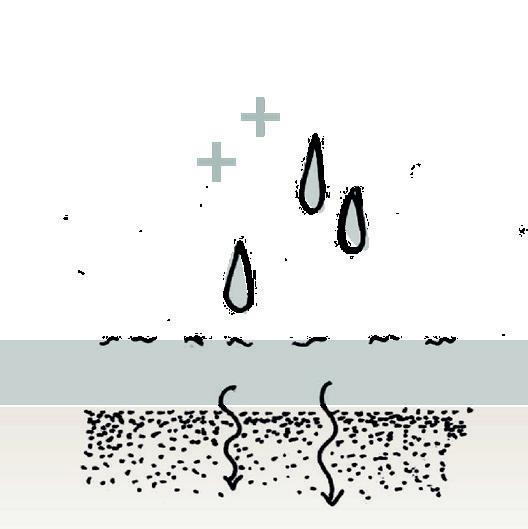

The crofts are not only designed to reconnect with the local landscape, but also to serve as guides to the Cromarty Firth’s water structures. Their strategic location provides additional advantages, addressing location-specific issues, such as preventing flooding in the event of a surplus of rainwater. Crofters will continue to live in the village, where they will further spread the emotional connection of the coastal crofting community.

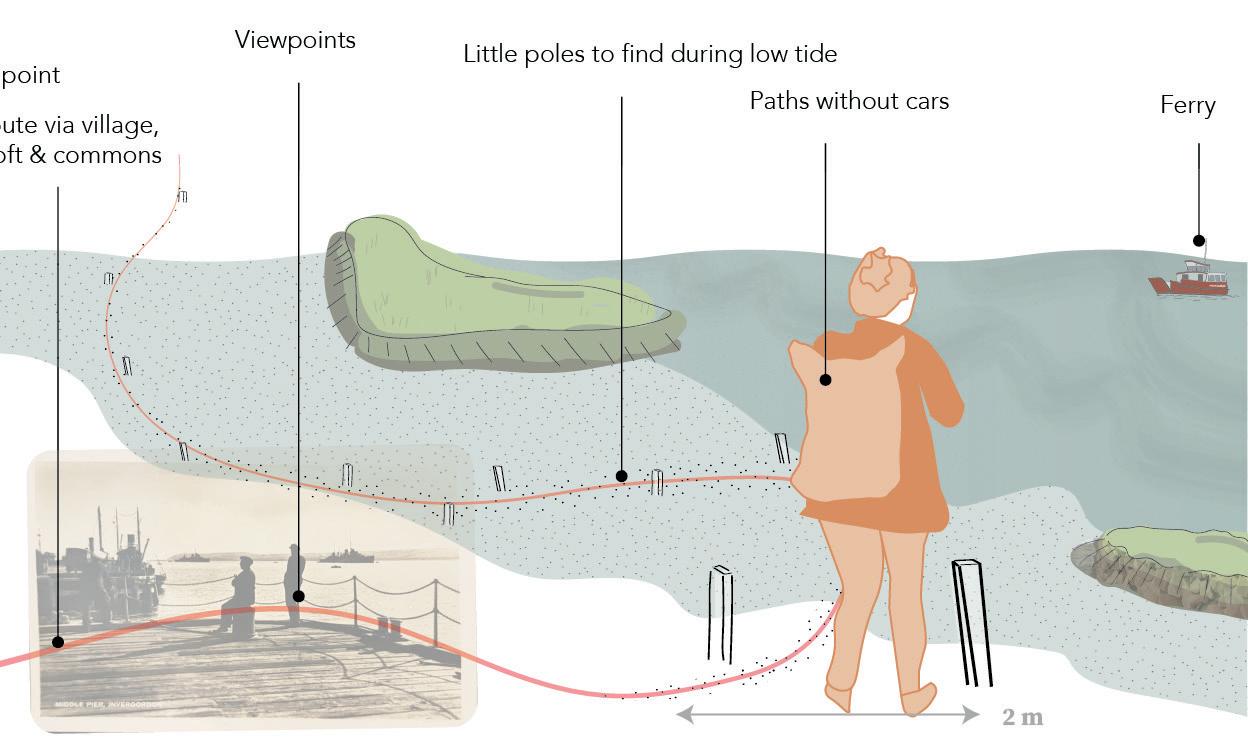

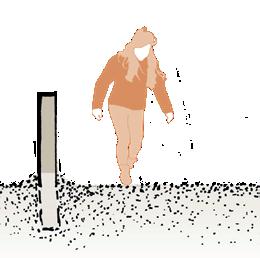

Beyond the solid base of crofts on land and commons on water, a connective element is introduced: a common line. The path structure will create a visible and emotional bond with the landscape. The following pages will provide a further elaboration of these three components.

Through this new relationship, the spatial and social relationship will be restored, and the firth will create the genius loci of the future.

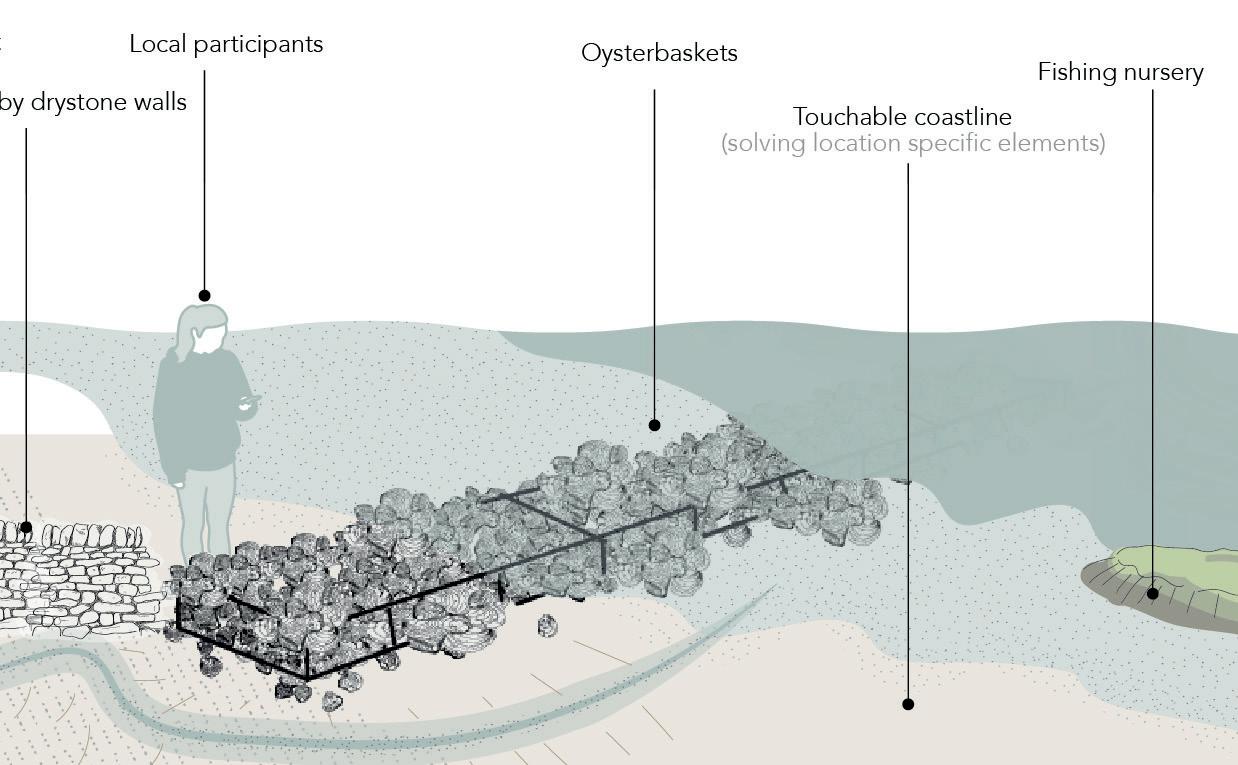

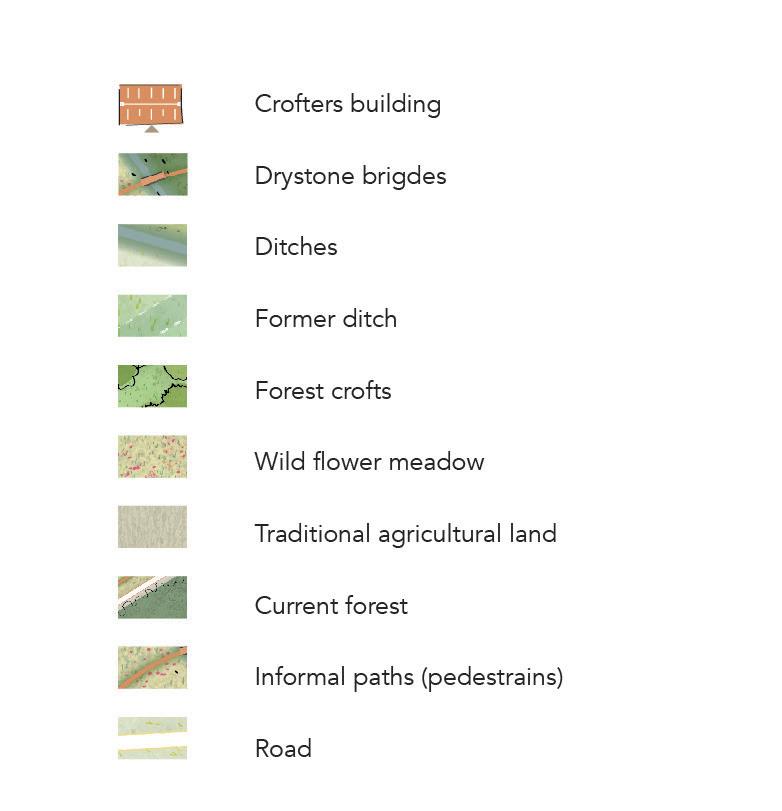

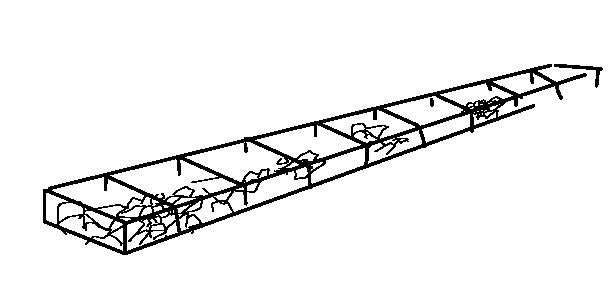

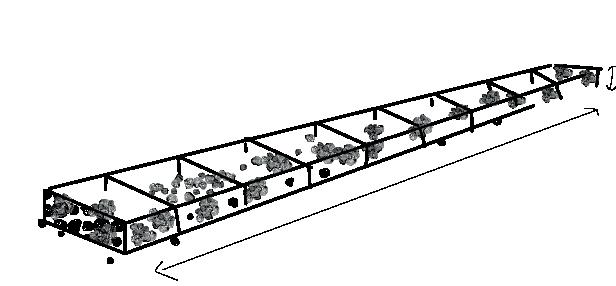

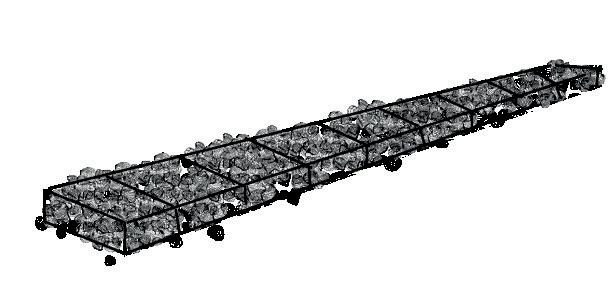

Each croft is unique and individual. They interact with the surroundings and serve as connectors to the firth. The rectangular plots provide space for crofters to cultivate their own paradise. Constructed elements, such as drystone walls and crofting neighbourhood buildings, create

readable elements alongside the diversity of the different crofts. Additionally, each crofting typology (river, coast, forest) incorporates croft specific elements that will be further elaborated in the detailed design zoom-ins.

Img. 112. Principle of Crofts

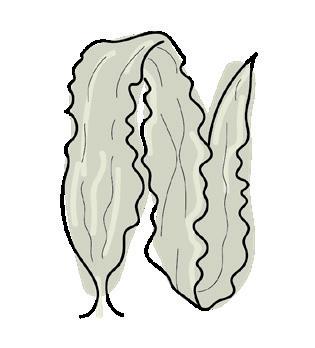

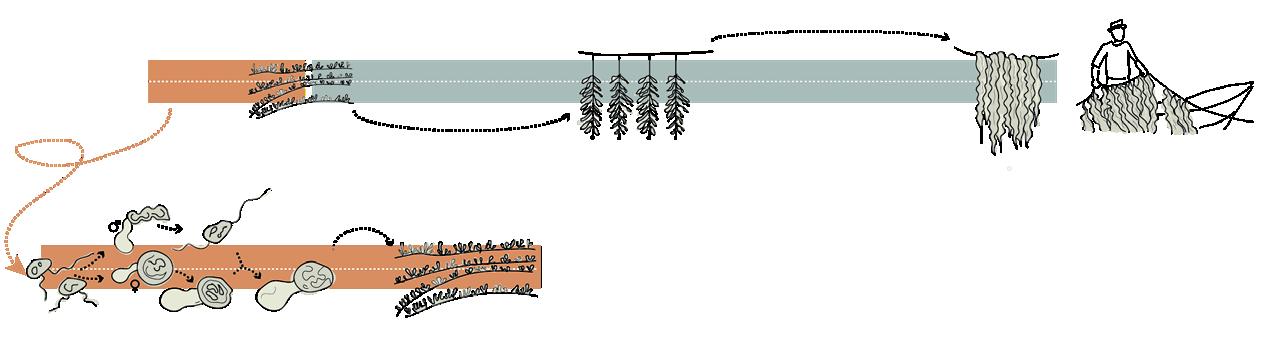

The commons serve as a meeting space where people can connect and interact. The commons take care of the crofts and the crofters feed the commons. Locally sourced common kelp provides natural fertiliser for the local crofts, reinforcing the cycle of mutual care. The crofts supply the local food market, providing community

well-being and self-sufficiency. By the water, the community has a shared place for gatherings and annual events that strengthen their connection to the Firth and the tradition it sustains.

Img. 113. Principle of common elements on land and water

The common routes link common locations with the variety of crofts. Offering the stroller the chance to explore the diversity and possibilities of this crofting landscape. From the heights of the hills, trough the villages and along the coastline, these paths weaves through the coastal crofting landscape and brings you anywhere.

Img. 114. Principle of common lines

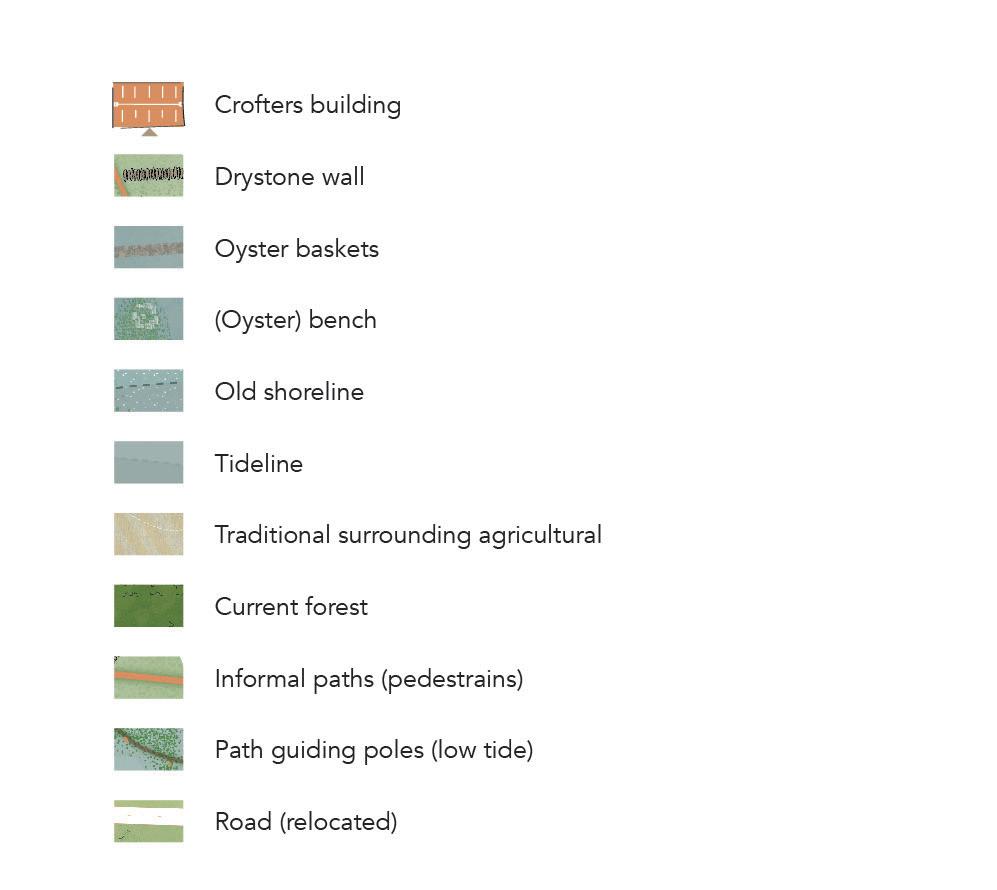

Zoning

Img. 115. Variation in crofting types reacting on specific context

Crofting

Common

Common path

Img. 116. Zoning plan of where is crofting and where is the common area

Decline in

Nutient outlet of distelleries

Rectilinear field and farms

Artificial harsh boarders/ coast protection

marine habitats

whole UK

Industrial boarder create a lost connection

Old part of town

Extended parts of town

Flooding risk

Artifical boarder Slow tidal speed area

Img. 117. Linking opportunities for additional connection for the new croft areas

Meadows

Rectilinear field and farms

Woodland

Saltmarsh

Village

Old part of town

Extended parts of town

Graveyard

Industry

Historical building

Traintrack

Road

River guiding forest

Wild flower meadows

River islands

Drystone/oyster wall

Water structure

River Croft

Forest Croft

Coastal Croft

Crofting neighbourhoodbuilding

Harbour

Tidal viewing structure

Common square

Ferryroute

Reused oil rigs

Walking network

Foreshore

Img. 118. Crofting landscape

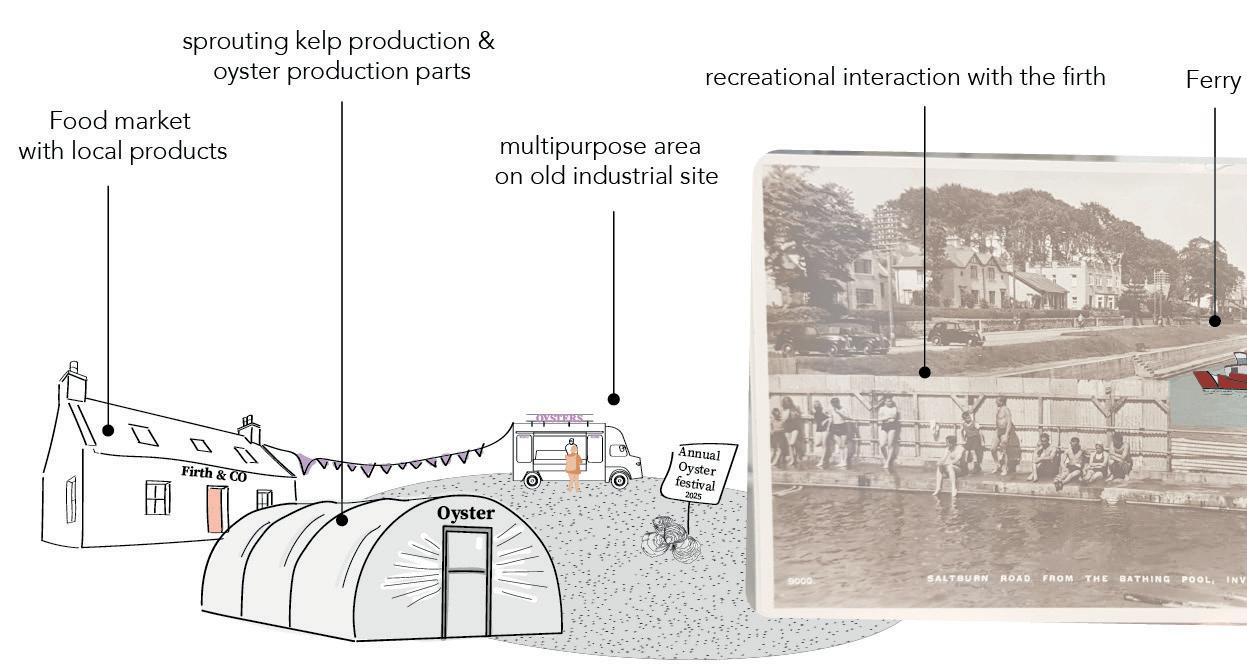

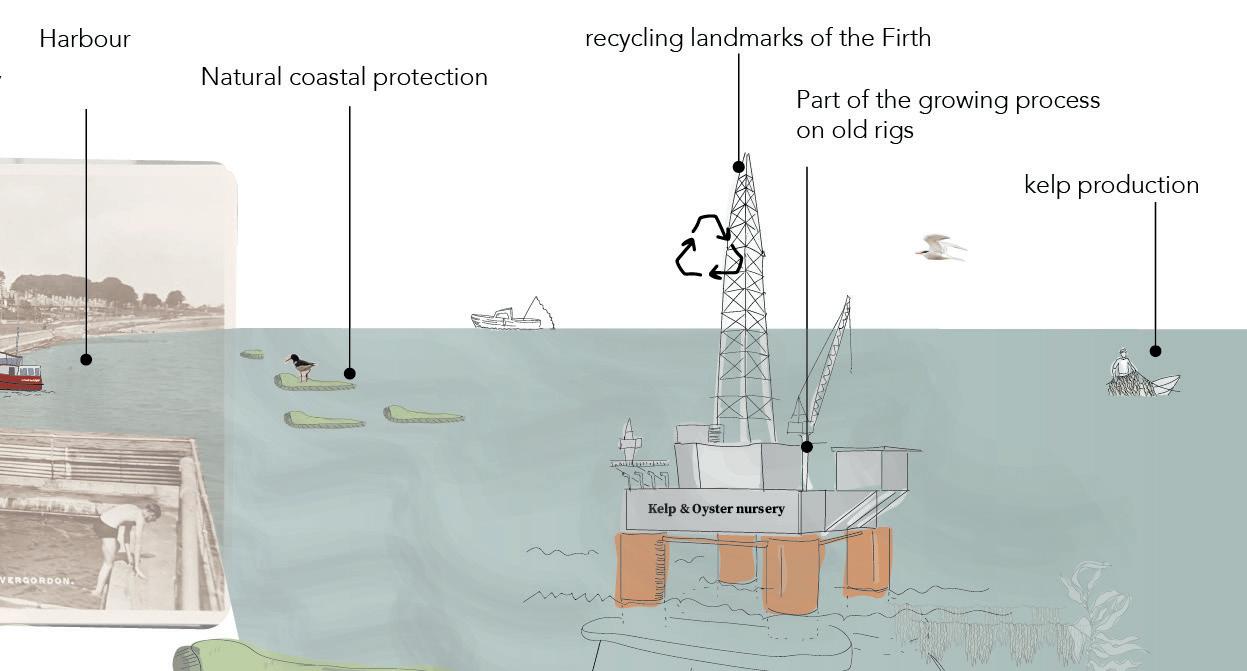

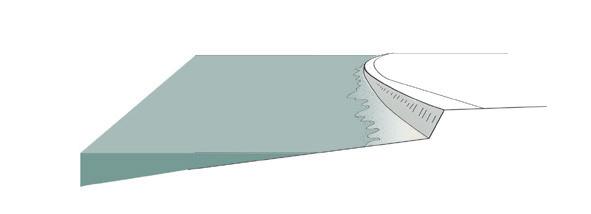

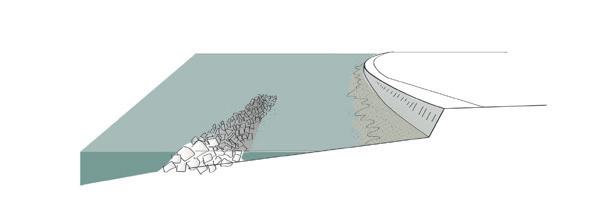

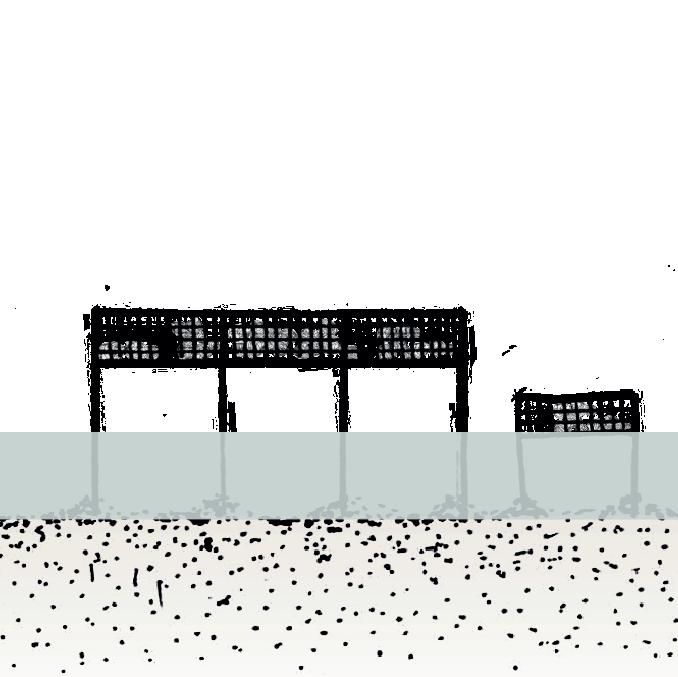

Once’s an industrial site, this area is now transformed into the central connecting common land. Relicts of the dismantled industrial site will be repurposed into new use. The water, ones constrained, is free to breathe again with the tides. Birdlife can forage on the naturalised shoreline and humans can finally see the water again.

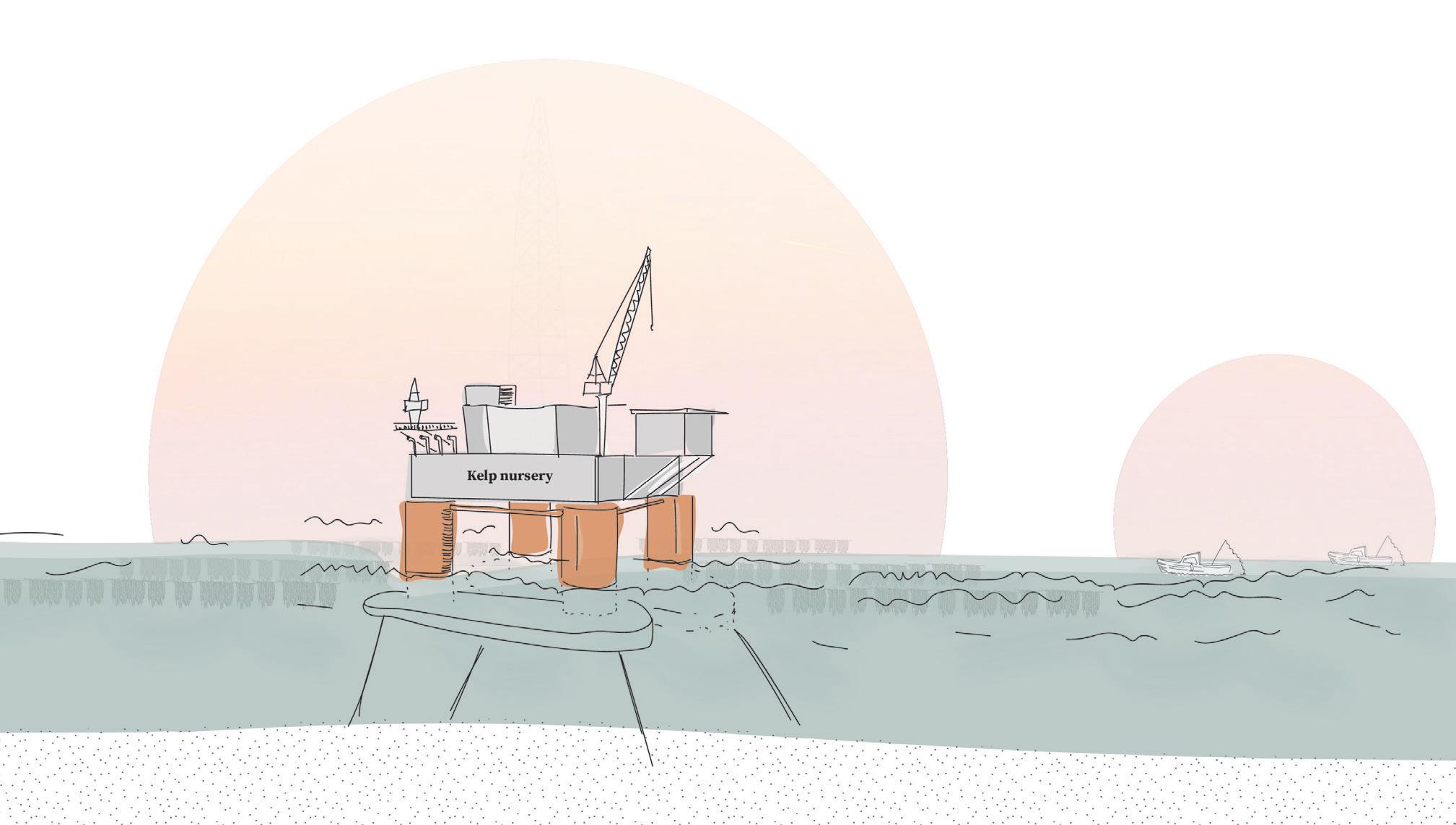

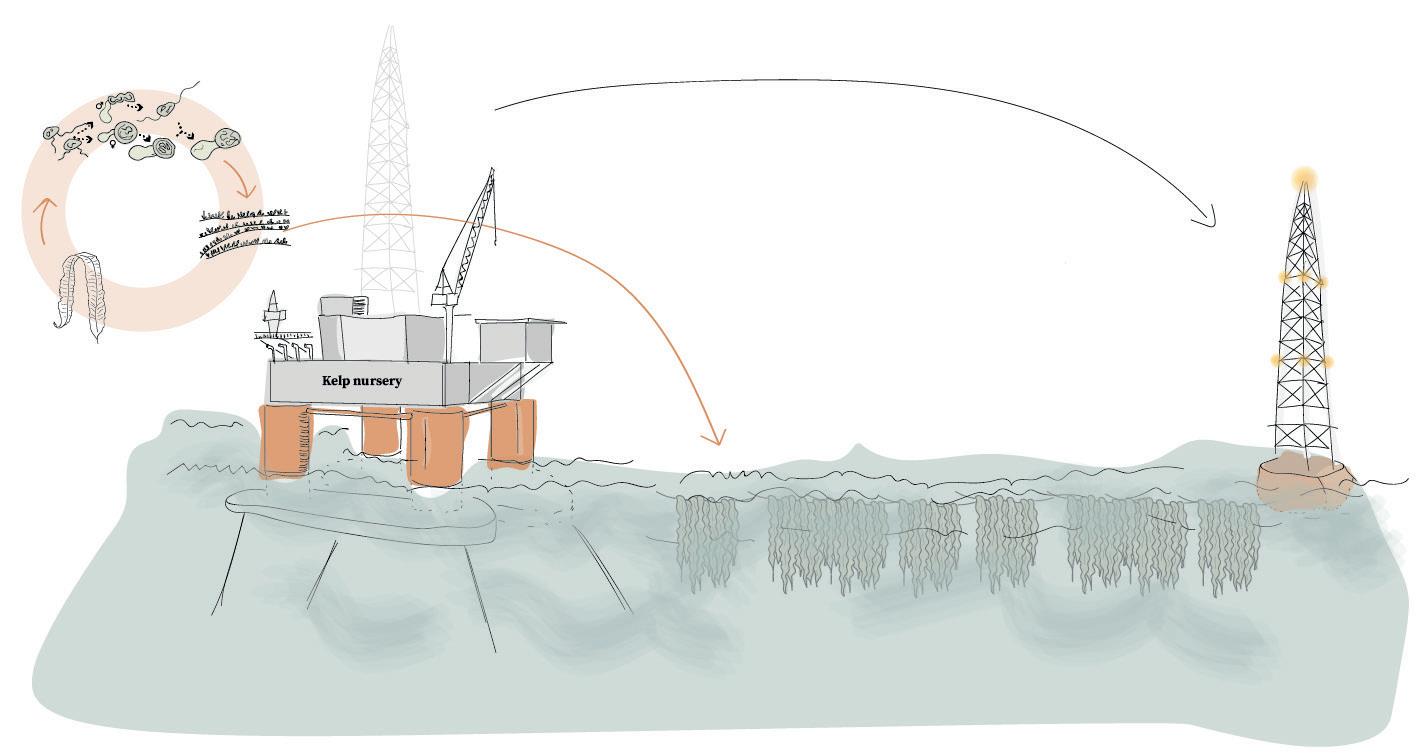

A central meeting place has emerged along the shoreline, with various references to the past. Oil relicts are being transformed into a food market, a square of helicopter deck remains, follies on the harbour site, and a kelp nursery on the firth. By breaking apart the industrial landscape, the commons are ones again reclaimed by the local community.

Img. 119. Creating the naturalised shoreline out of old harbour materials as a base

Ferry to Black Isle Farmers market with seasonal activities of the crofters

Kelp nursery on central reused oil rig

Common fishing

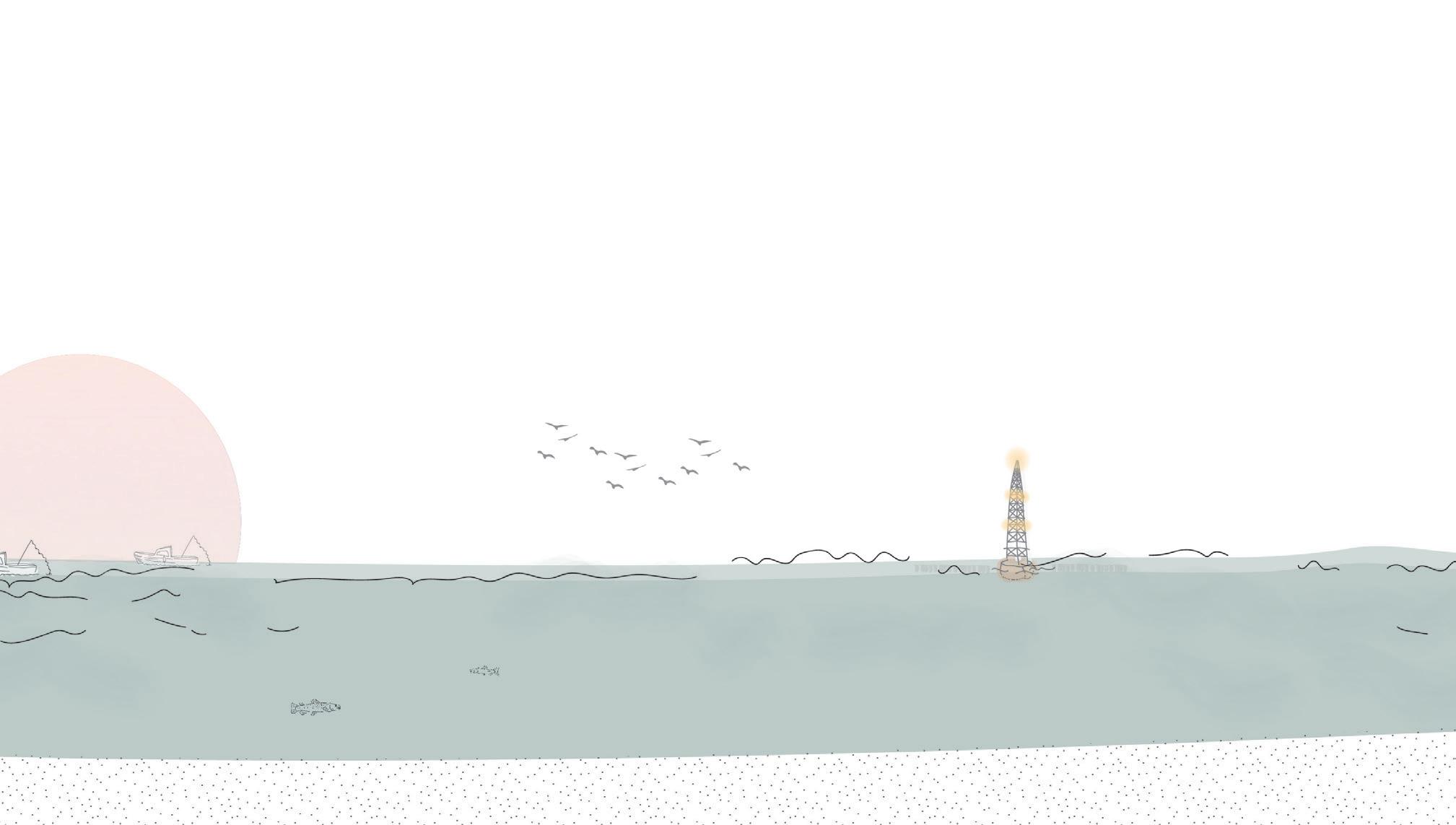

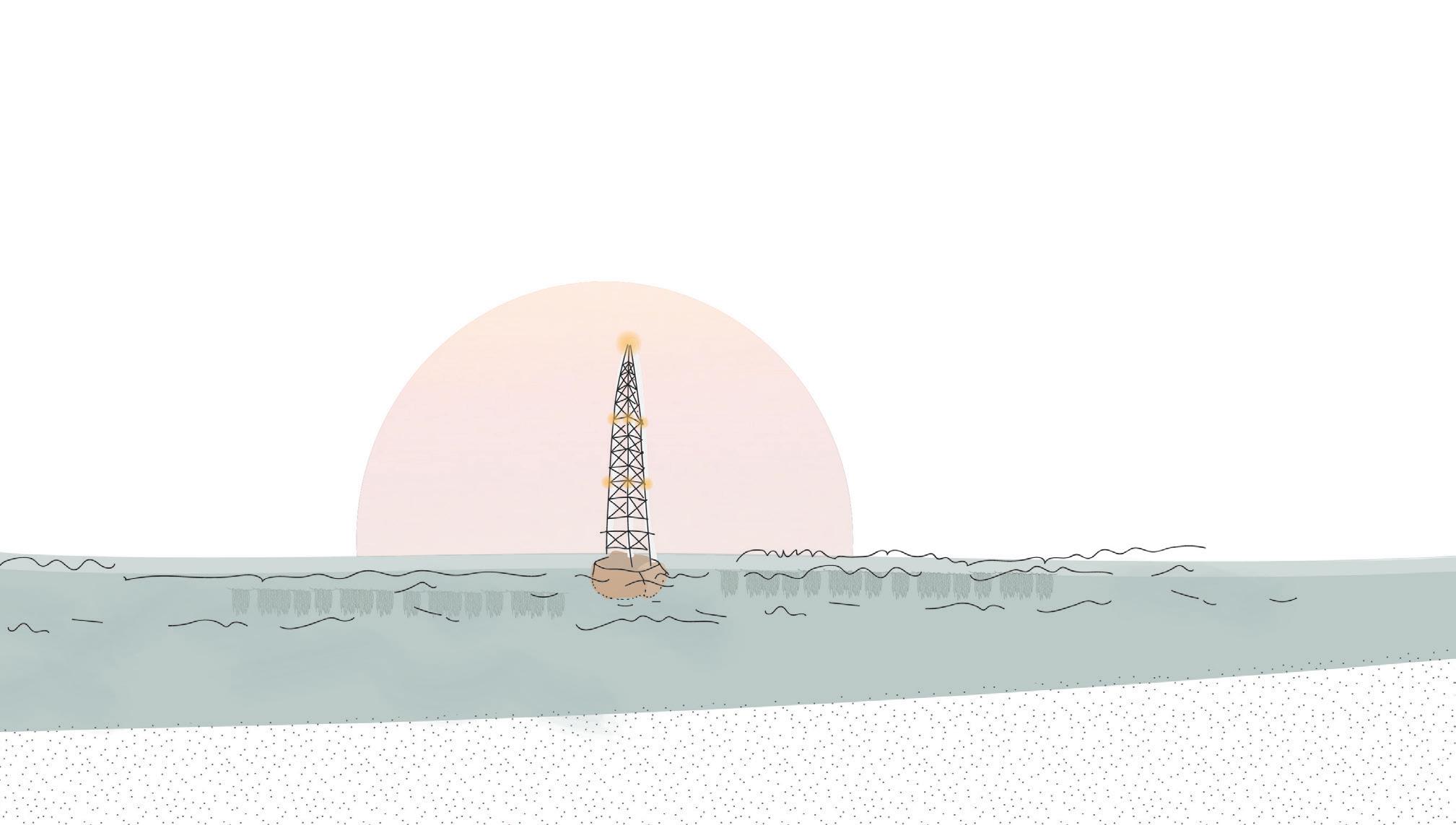

Kelp and landmark in one

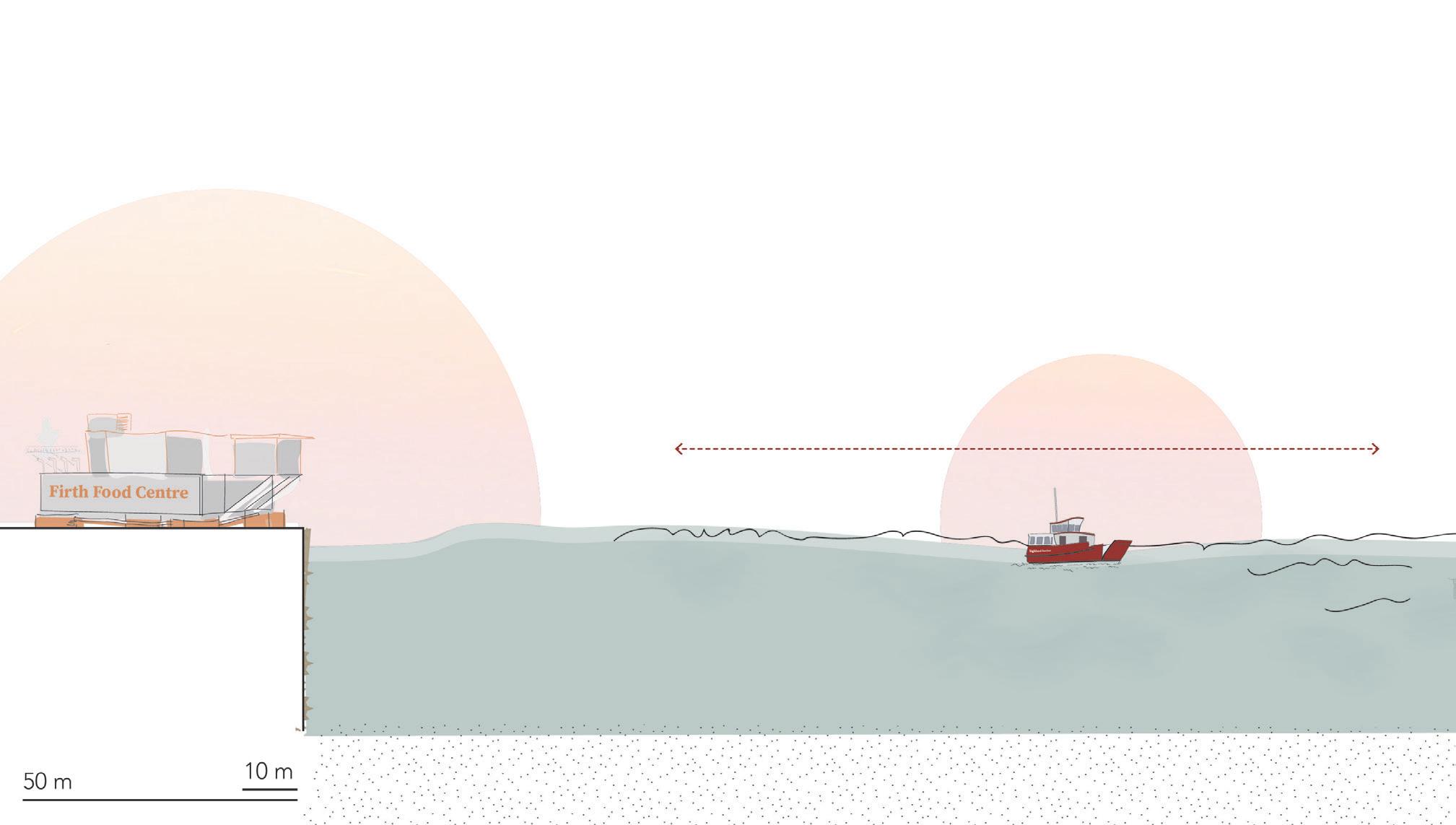

121. Cross section of common water area with the reused elements

drystone wall & oyster baskets

122. Cross section of common water area with the reused elements

Drill pipe rack: for kelp farming icons on water

Main deck becomes foodmarket

Helicopterpad as sqaure element

Img. 123. Reusing materials for the new common ground where meeting and food are central

as a folly

124. Visibility of the common kelp with reuse of a part of the industrial landmarks

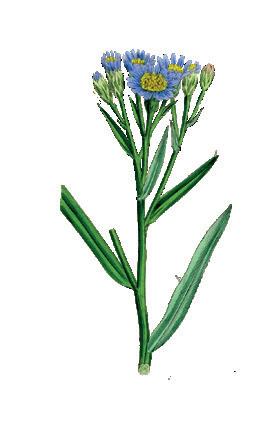

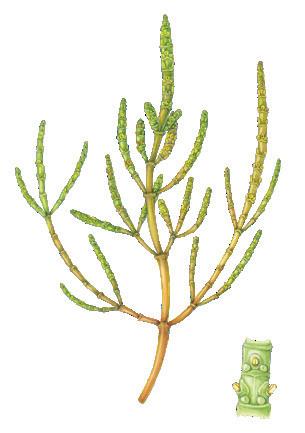

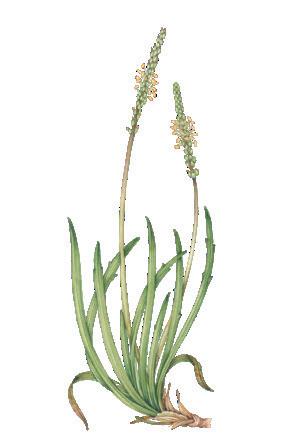

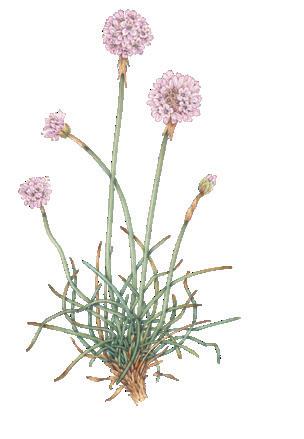

Species on land

Alder

Anus glutinoasa

Ash Fraxinus excelsior

Birch Betulaceae

Gorse Ulex europaeus

Elm, Wych

Ulmus glabra

Juniper Juniperus communis

Native oyster

Gametophyte rearing in greenhouse

Transportation of young sporophytes

Broodstock preperation

Collecting zoospores

Harvest period

Rearing of young seedling in greenhouse

Grow-out in floating raft mid-november to mid-july

<2 hr 7-10 days

Harvest period

Fishing period

Img. 125. The upper route parts give a view and visual connection to the firth day and night

Img. 126. Part of the route only gets visible durig low tide

The individual crofts will restore the sense of place while addressing local issues. Together, they create a unique landscape, unified by its variation. Socially, they are connected as a wider community, while fine-scale connections are being made within the local crofting neighbourhoods.

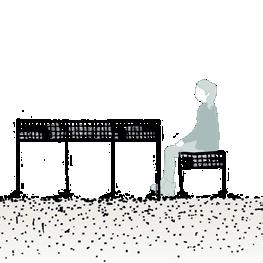

Each crofting neighbourhoods has their own crofters’ building. Providing a space where local crofters can meet each other in an accessible way, exchange information and materials, or store harvest. A neighbourhood exist of a small group of up to ten crofters that share this facility. Beyond this, there are no buildings on the crofts, as the crofters live in the villages nearby.

Different typologies reflect its individual relationship to the firth. Each type of croft (river, coast, forest) has a unique set of game rules, alongside the basics. Crofters will receive a guide as starting point, ensuring the variety in the whole crofting community and fitting to the local challenges and conditions.

The crofting system can response to the needs of the people of the Firth. After the first crucial adjustments to the landscape structure, the community may expand the crofting system further if desired. The system should be dynamic to maintain a mutual relation.

Img. 128. Possible expansion of crofts

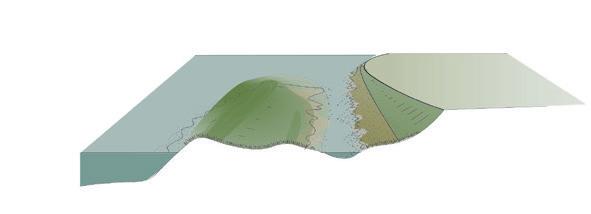

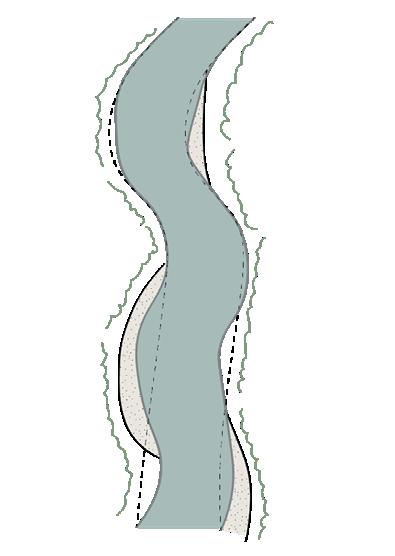

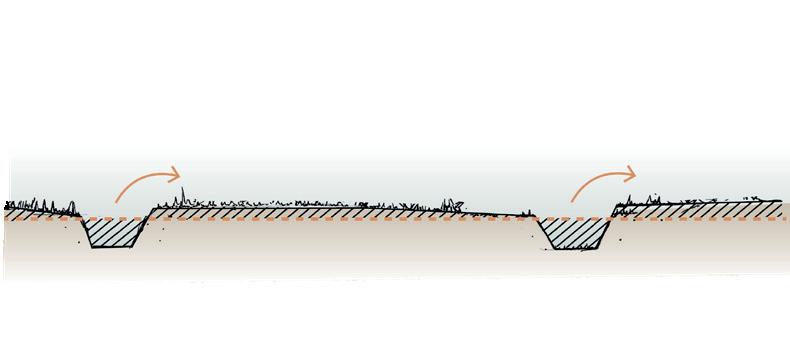

By giving space to the river, it can flow freely again. Restructuring the river allows river beds to emerge, providing essential flood zones during high peaks. This terrace land can be used by the crofters to regulate their croft variations. To enhance biodiversity, flower meadows are sown in the area, along with the river guiding forest on the opposite side of the riverbanks. The pedestrian bridge offers an extra crossing with the opportunity to witness the river entering the firth.

Design elements

D r y s tone wall

D r y s tone bridge

C o fting neighbourhood

Img. 130. Design elements river croft

I n for malpath

W i l d flower meadows

R i v er g u i dingforest

W a terbuffering

Jan

Feb

March April

May

June

July

Aug

Sept

Dec

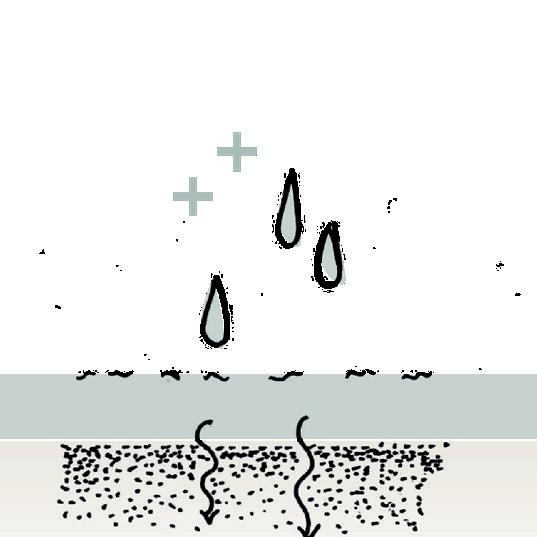

By establishing a water structure that directs the waterflow during flooding and protects the raised forest beds, the forest crofts form another link to the water entering the firth. The added elevation controls drainage.

The variation in the forest species between the ditches, alongside with the wildflower meadows, create an interesting landscape for both animals and humans.

Design elements

D r y s tone bridge

I n for malpath

C o fting neighbourhood

Img. 136. Design elements forest croft

W i l d flower meadows

R i v er g u i dingforest

W a terbuffering

Forest croft vegetation selection

Jan

Feb

March

April

May

June

July

Aug

Sept

Oct

Nov

Dec

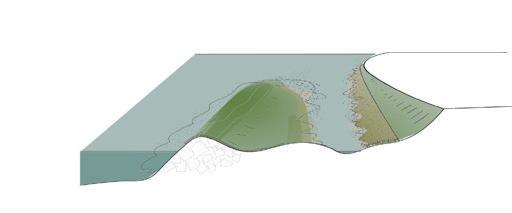

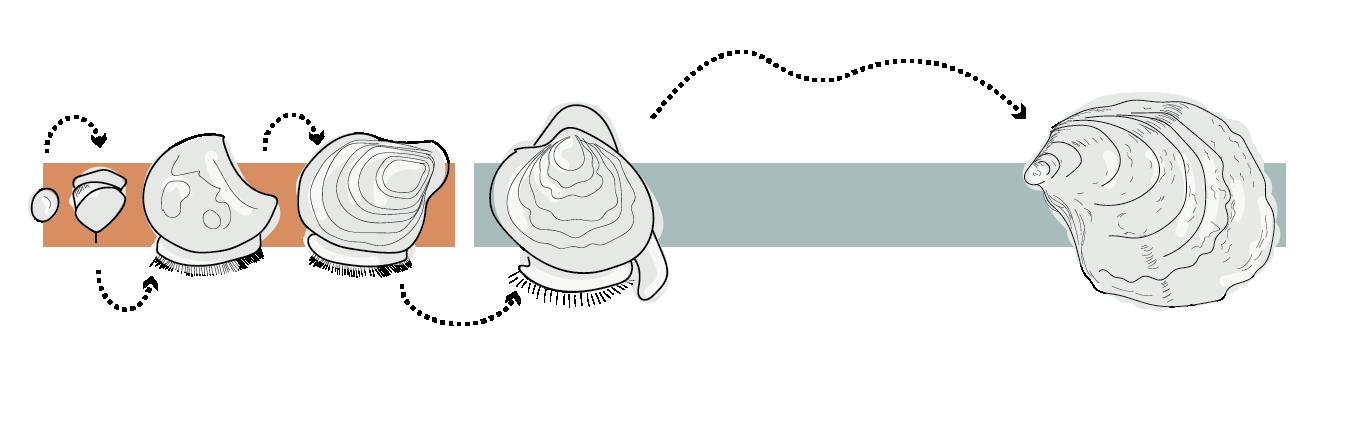

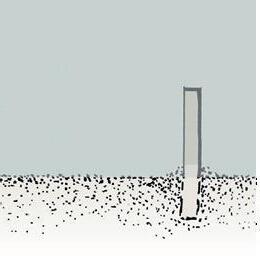

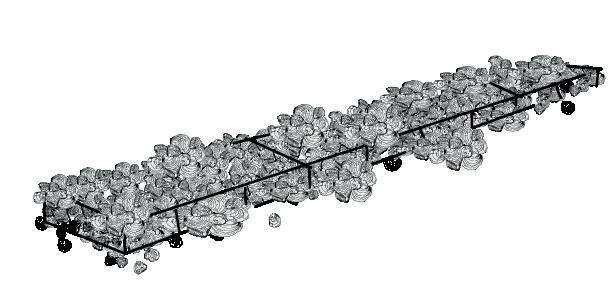

Harsh boarders are softened, creating space for the firth to breath. This intertidal space provides crofters the opportunity work with the rhythms of the tide. Drystone walls merge seamlessly into oyster baskets to grow native oysters. When the tide recedes, a whole world is revealed. An oyster bench offers a place to sit and gather, a common path that becomes visible, and the richness and beauty of the tidal ecosystem is unveiled. The high and low water continuously play with the elements, ensuring the interaction is different every time.

Wherever water needs breathing space and connection, this crofting typology could also be implemented.

Design elements

D r y s tone wall I n for malpath

D r y s tone wallturinginto oyster baskets

C o fting neighbourhood

Img. 142. Design elements coastal croft

P o les for aninformal low tide path

O y s ter benchintidal area

The mosaic of crofts brings a renewed emotional and physical dimension to the landscape of the Cromarty Firth. The coastal zone now extends further inland, blending land and water. As a result, the community is interacting, talking and connecting with each other. They are forging connections between one another and the landscape they inhabit.

First, my thanks go to my graduation committee members Yttje Feddes, Ziega van den Berk and Dingeman Deijs, who guided me throughout the process. Lisa McKenzie and Anaïs Chanon (the University of Edinburgh), thanks for the help in finding a new adventure in Scotland to graduate on.

Leonie and Pauline, thanks for being a part of my EMiLA story. For joining me on my fieldtrip, the feedback and the endless search for correct height lines and data. It was a true “scotventure”!

Also, a shout out to the people who I met on my site visits. From the librarian in Invergordon, who helped me to find local sources, to the volunteer at the Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project who told me all about growing oyster populations. To the B&B owner, the people in the pub, and people on the streets who shared their stories with me. All of your stories have shaped my journey and enriched my graduation.

Helena, thank you for the time spent studying together, supporting each other and your inexhaustible enthusiasm. You also did it!

I would also like to thank my informal committee of colleagues. Arthur, Saskia, Killian, Mischa, Heleen and Jeroen. Thank you for listening to my stories, your encouragement and questions.

Last but not least, my family and friends for their endless support.

Architecture Design Scotland. (n.d.). Climate Action Towns. Retrieved from Architecture Design Scotland: https://www.ads.org.uk/ resource/climate-action-towns

Ash, M. (1990). This Noble Harbour. A History of the Cromarty Firth. John Donald Publishers Ltd.

BBC. (2020, September 4). The Highland Clearances. Retrieved from BBC Bitesize: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ bitesize/topics/zxwxvcw/articles/ zr7pmfr

Crofting Commission. (2025). Retrieved from Crofting Commission: https://crofting.scotland.gov.uk/ about-us

Crofting Commission. (n.d.). What is Crofting? Retrieved 2024, from Crofting Commission: https:// crofting.scotland.gov.uk/what-iscrofting

Gillen, C. (1993). The Geology and landscape of Moray.

Haig, R. (Director). (2015 ). Crofting’s New Voices [Motion Picture].

NatureScot. (2019). Landscape character assesment- Ross & Cromarty landscape evolution and influences. NatureScot.

Ross and Cromarty Heritage Society. (2024). Invergordon Past and Present. Retrieved from Ross and Cromarty Heritage: https://www. rossandcromartyheritage.org/

home/easter-ross-communities/ invergordon/invergordon-history/ invergordon-past-and-present/

Scottish Government. (2011, March 16). Scotland’s Marine Atlas: Information for The National Marine Plan. Retrieved from https:// www.gov.scot/publications/ scotlands-marine-atlas-information-national-marine-plan/pages/27/

Scottish Government. (n.d.). Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation Retrieved from Scottish Government: https://www.gov.scot/ collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020/

The Geological society. (n.d.). The Great Glen Fault, Scotland. Retrieved March ’, from The Geological Society.

The National Trust for Shcotland . (n.d.). The crofting landscape. Retrieved from The National Trust for Scotland : https://www.nts.org.uk/ visit/places/balmacara-estate/ highlights/the-crofting-landscape?lang=en_gb

Visit Fort William. (2024). The Highland Clearance. Retrieved January 2024, from Visit Fort William: https://visitfortwilliam.co.uk/ pages/about-the-highland-clearances-during-political-change-inscotland-605f95da

Voices Over the Water. (2015). Highland

Clearance Timeline of Events. Retrieved Januari 2024, from https://voicesoverthewater.com/ about-the-film/highland-clearances-timeline/

Watson, F., & Dixon, P. (2018). A History of Scotland’s landscapes. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland.

Watson, F., & Dixon, P. (2018). Crofting. In F. Watson, & P. Dixon, A History of Scotland’s Landscape (pp. 209,219). Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland.

Data sources for maps

Historic Environment Scotland (HES)

National Library of Scotland

Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA)

Spatial data of Scottish Government

The James Hutton Institute

Images, text and drawings are made by Laura Kragten unless otherwise stated.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author.

Date: 26 May 2025 © Laura Kragten

Graduation book

European Master In Landscape Architure (EMiLA) Academy of Architecture 2025