KIKANZU CAMBAMBA

Embracing informality and resilience in Luanda’s public space

Helena Fernandes De Raeymaeker

Colophon

Helena Fernandes De Raeymaeker

Master of Landscape Architecture Graduation Project under supervision of Marieke Timmermans (mentor), Aura Luz Melis and Philomene van der Vliet

Additional member examination committee: Jana Crepon and Remco van der Togt

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture, May 2025

Copyright © 2025: Helena De Raeymaeker

Behind the curtains of the modern city

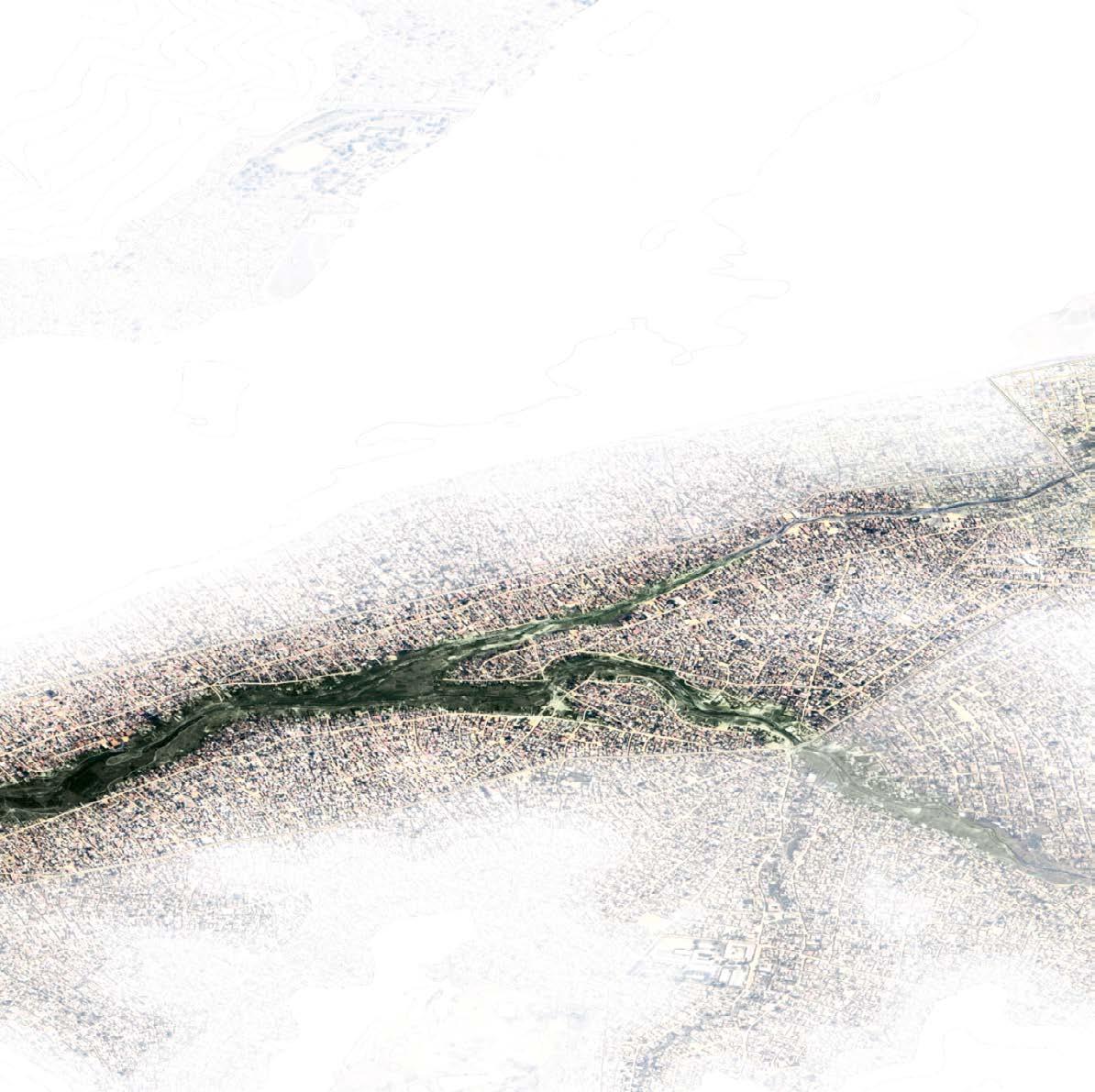

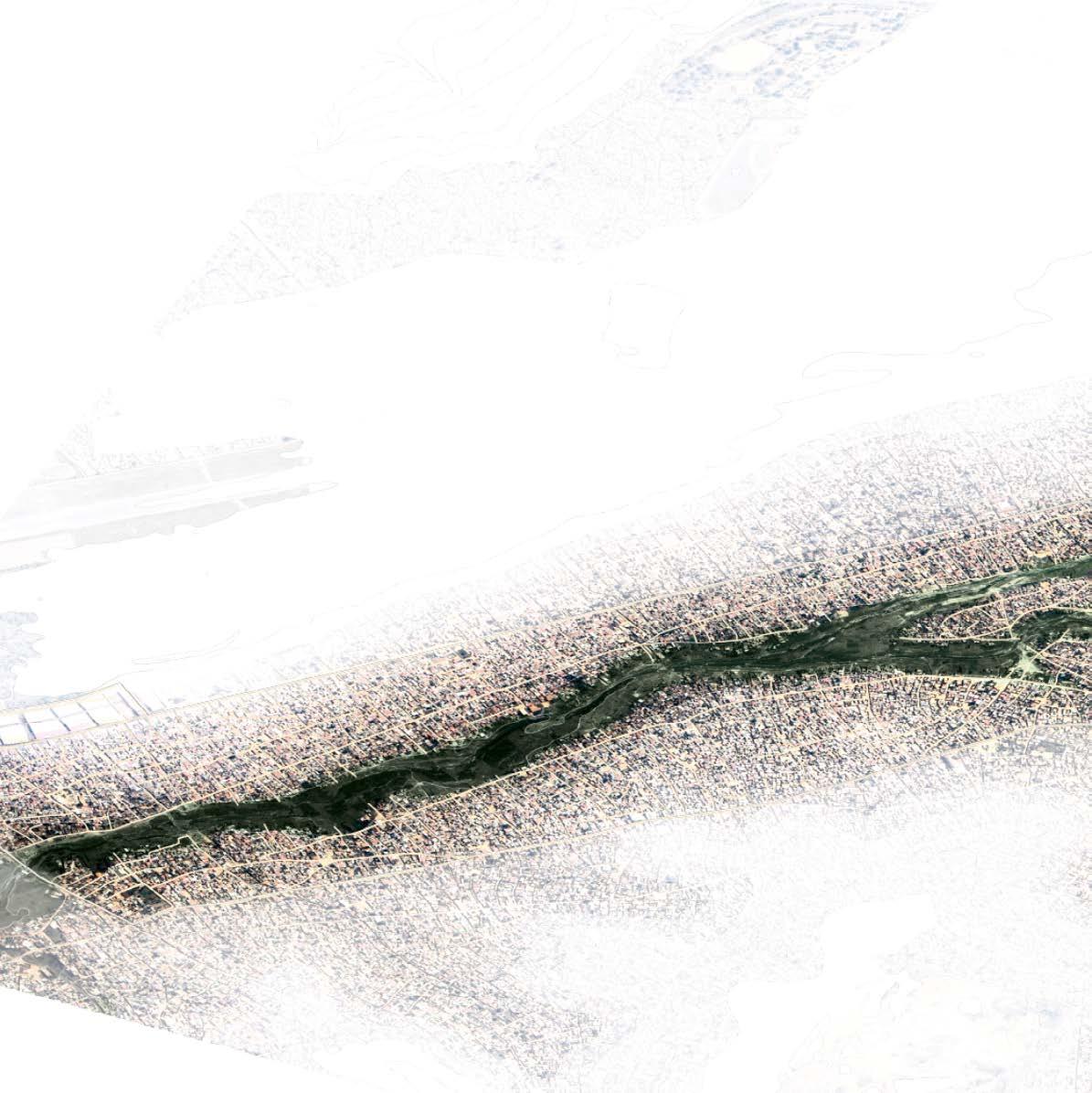

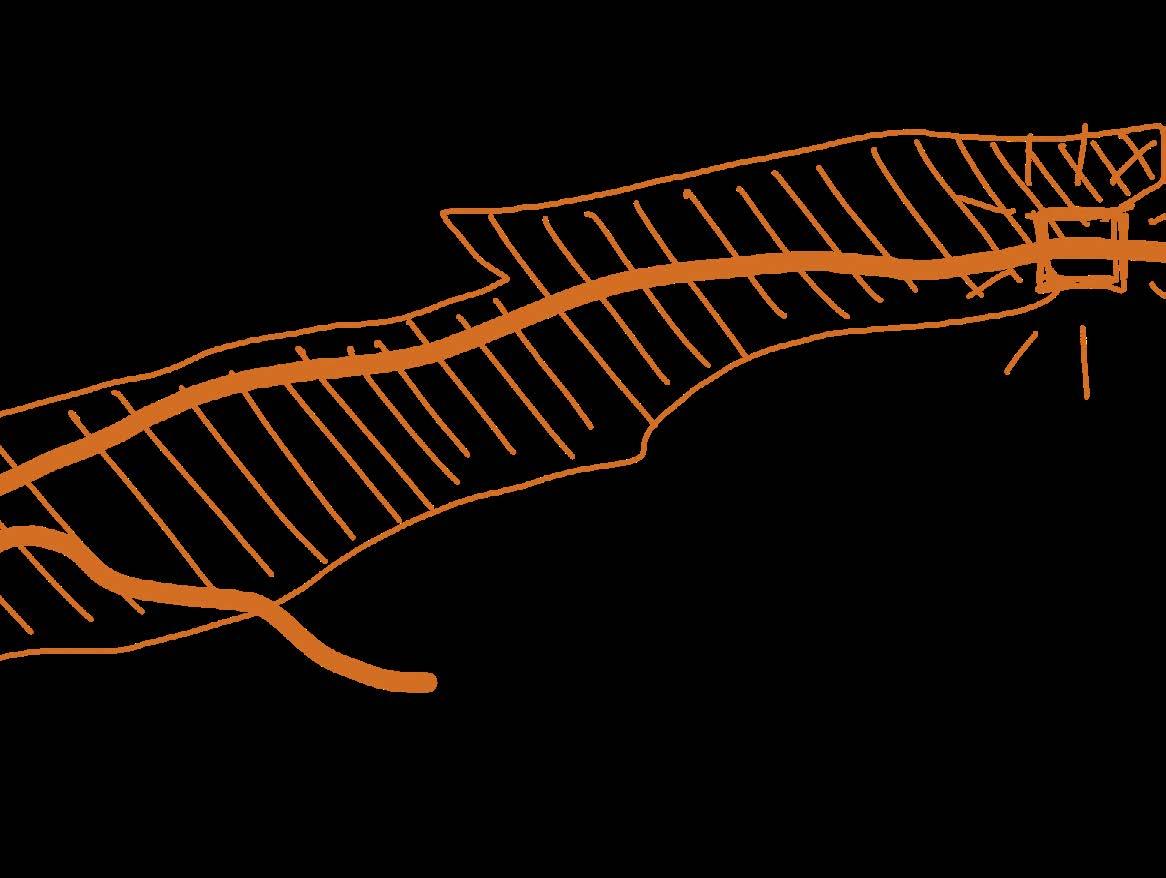

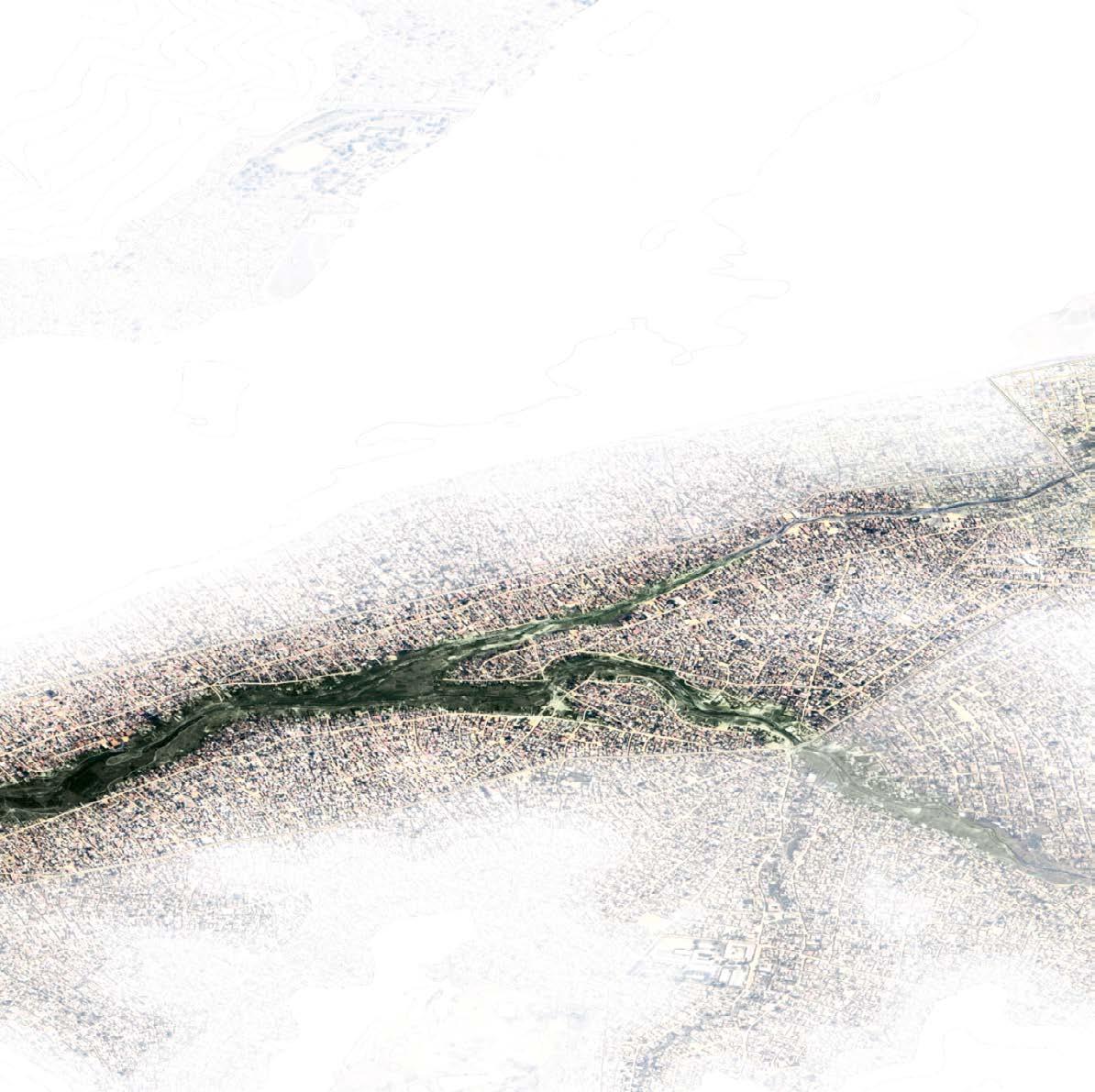

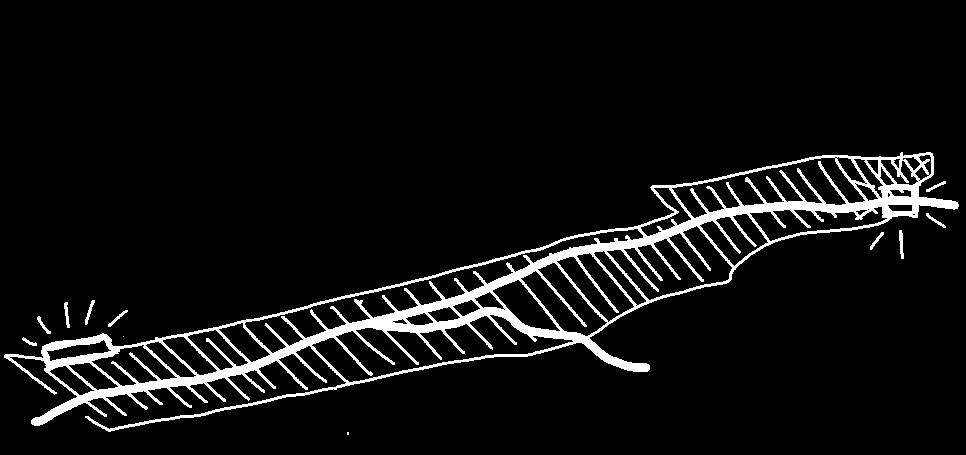

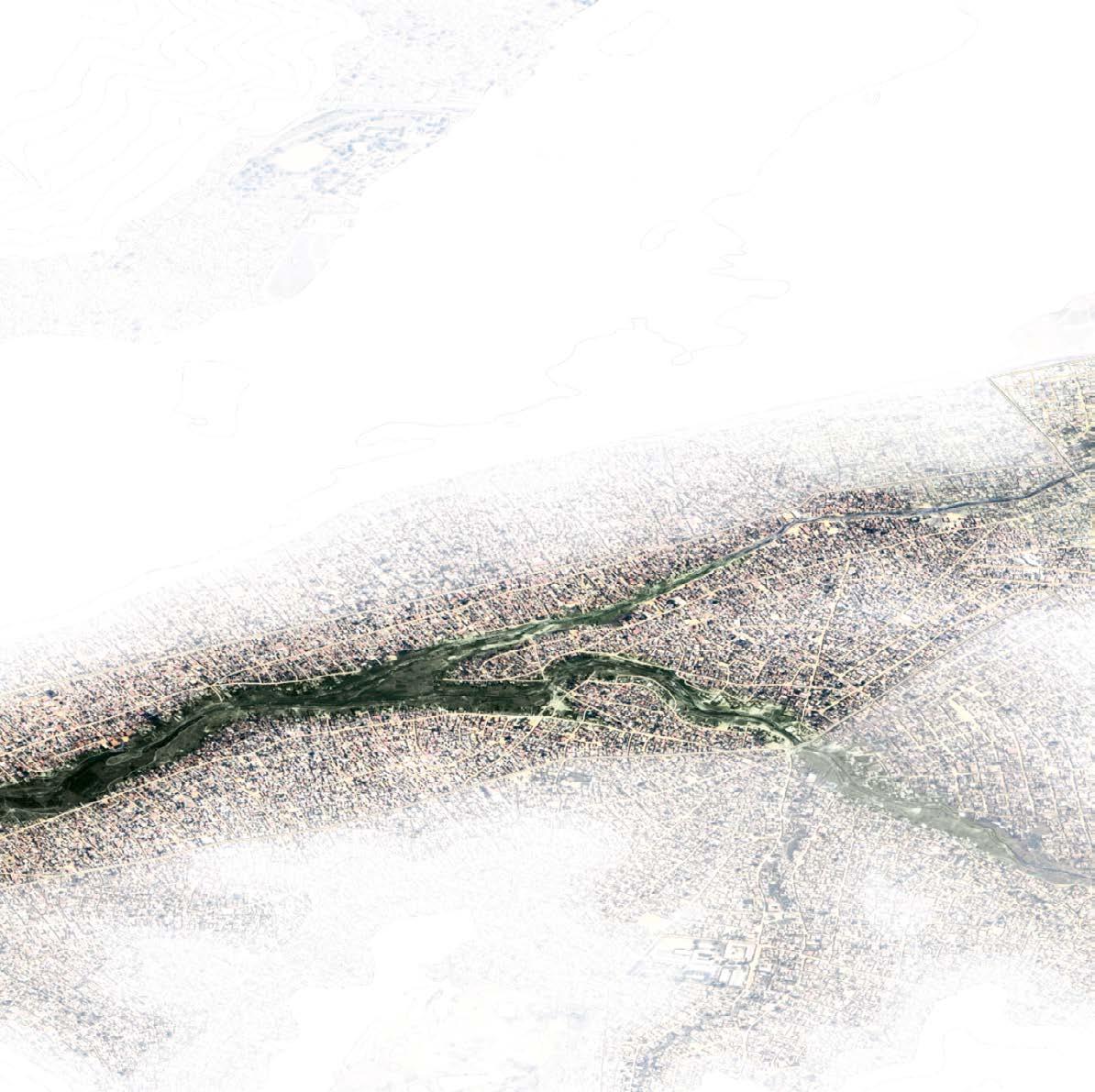

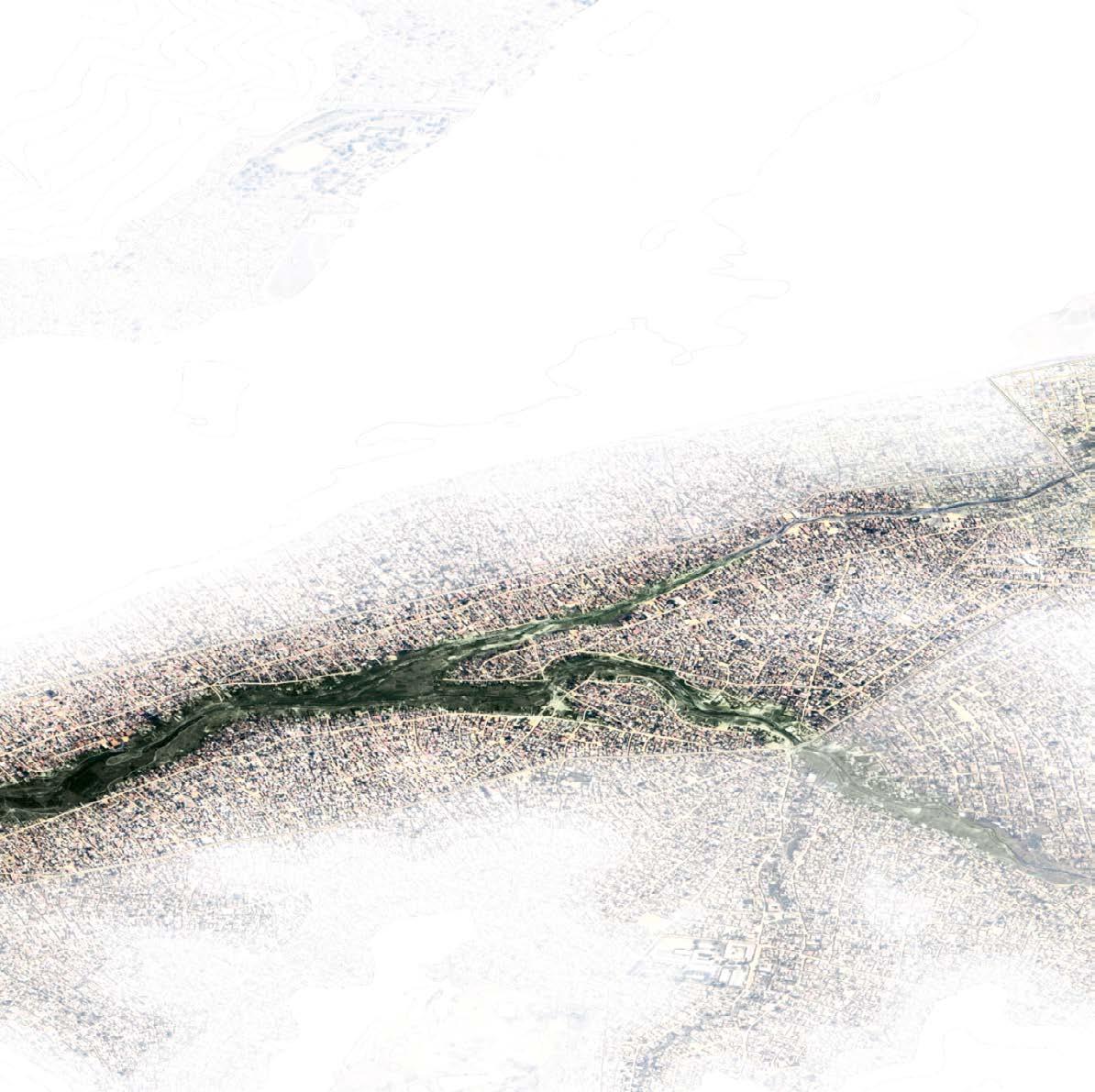

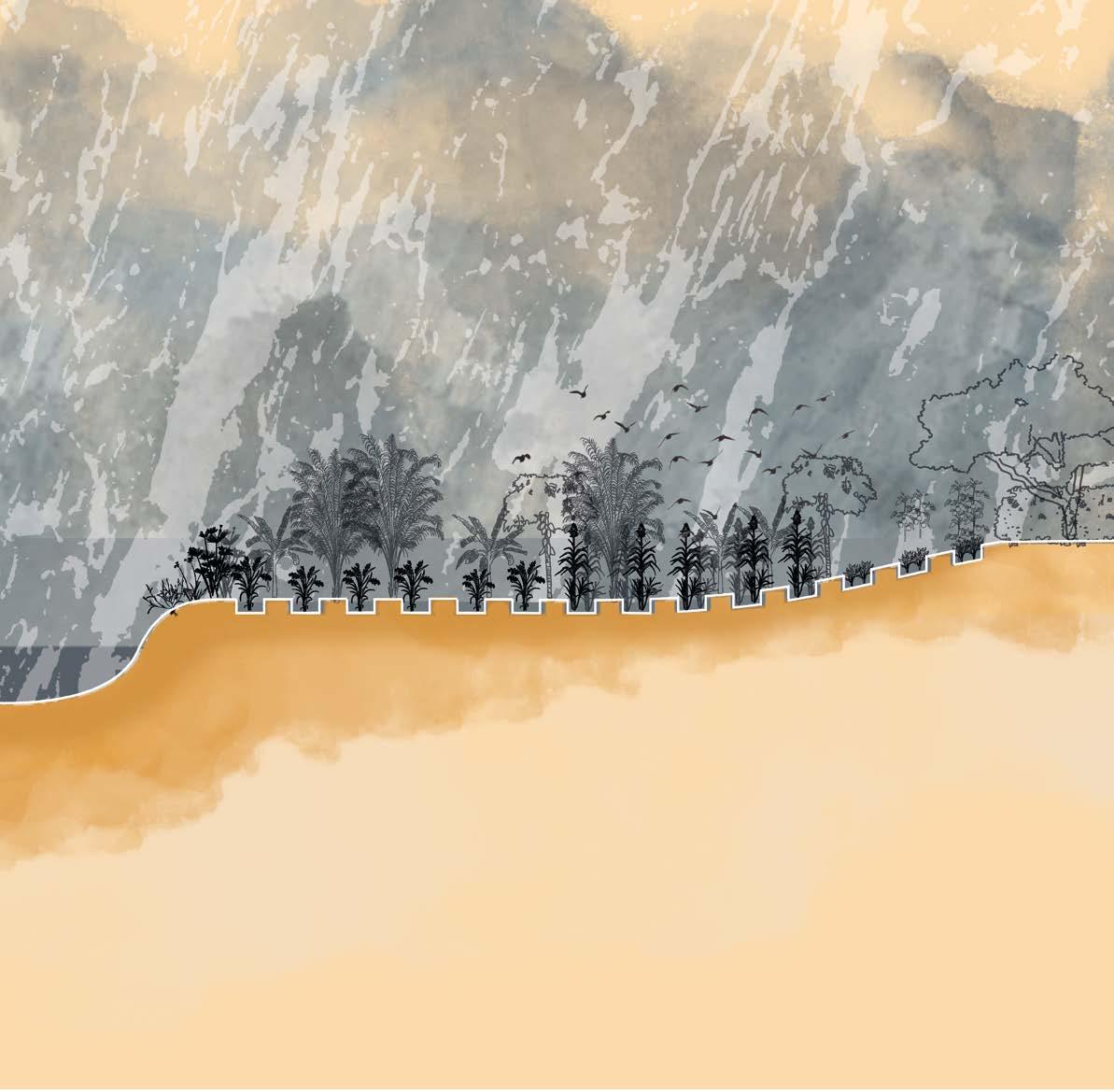

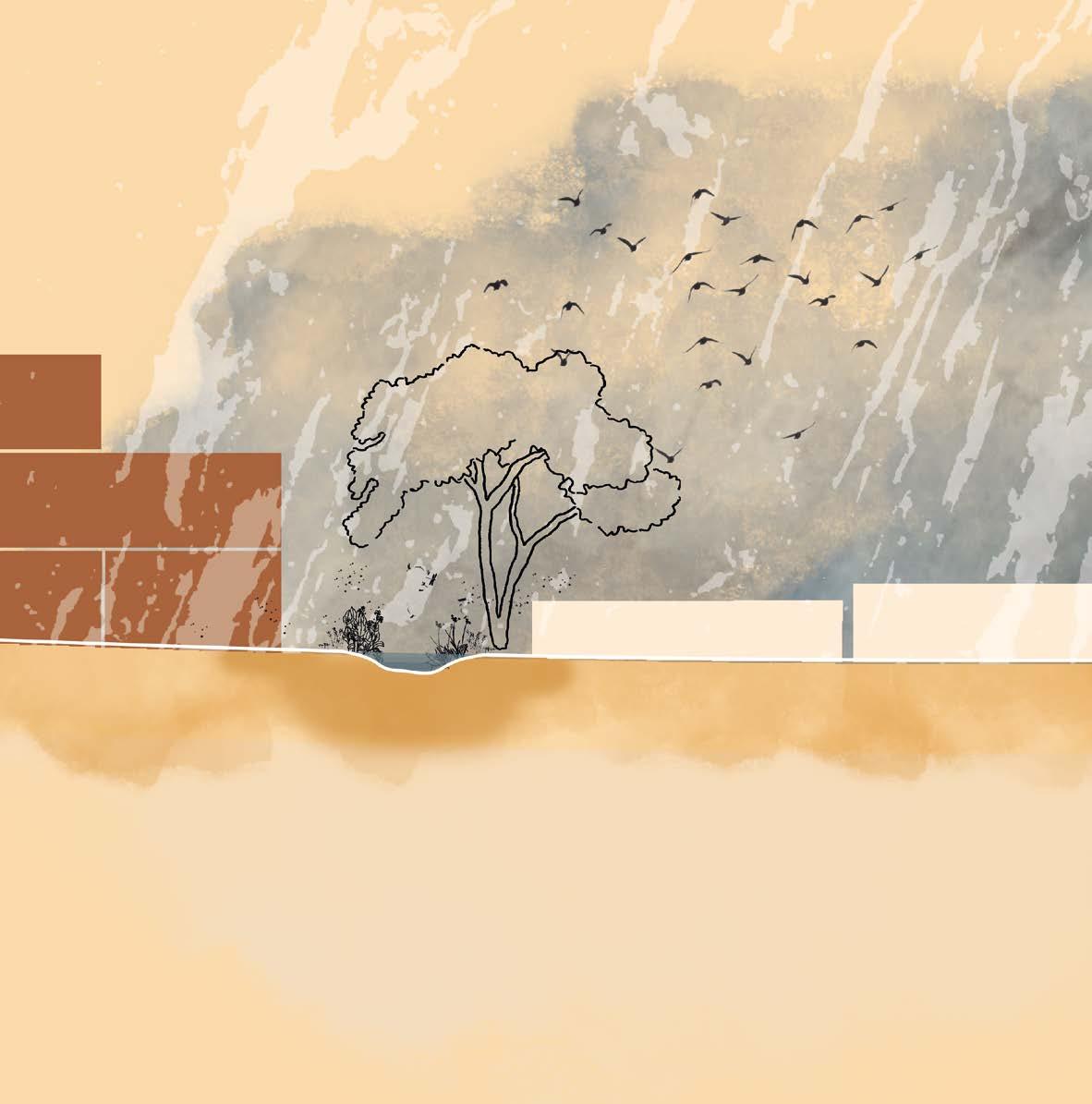

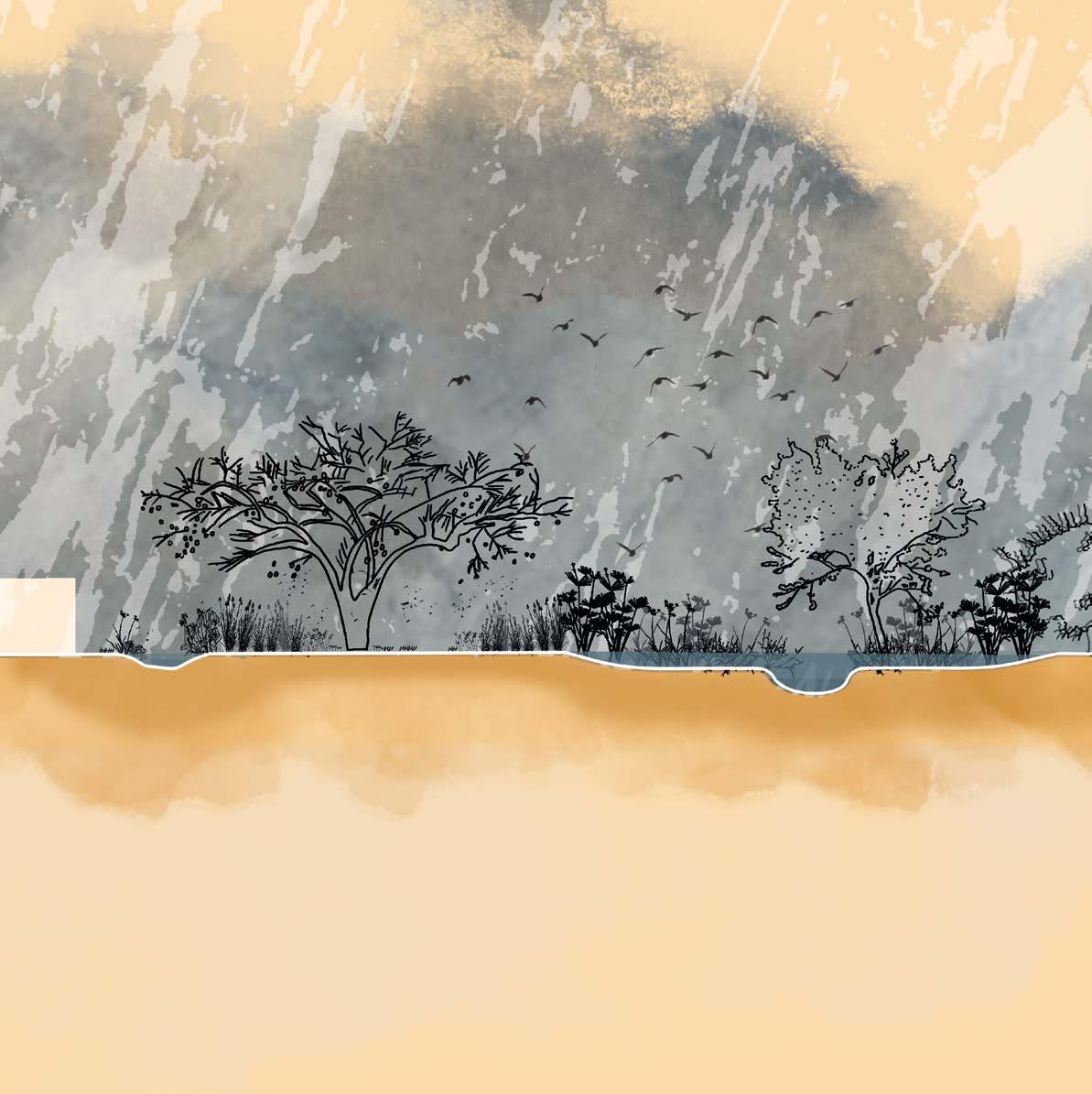

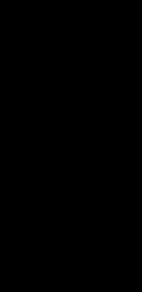

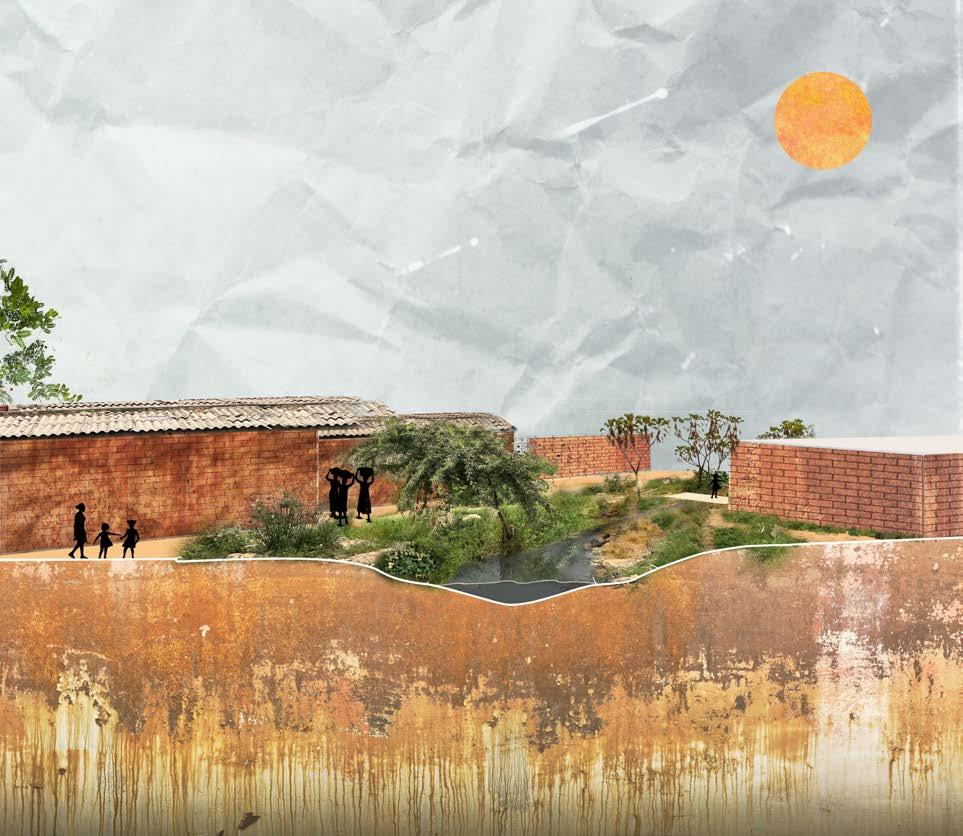

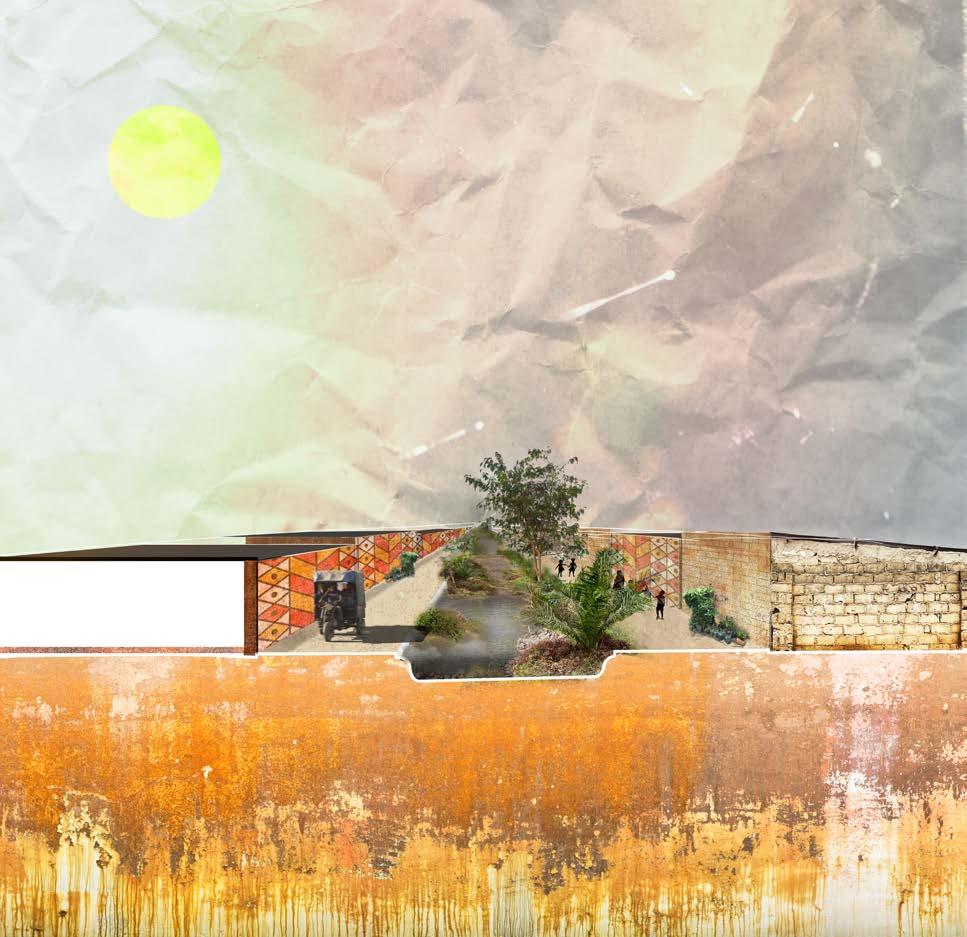

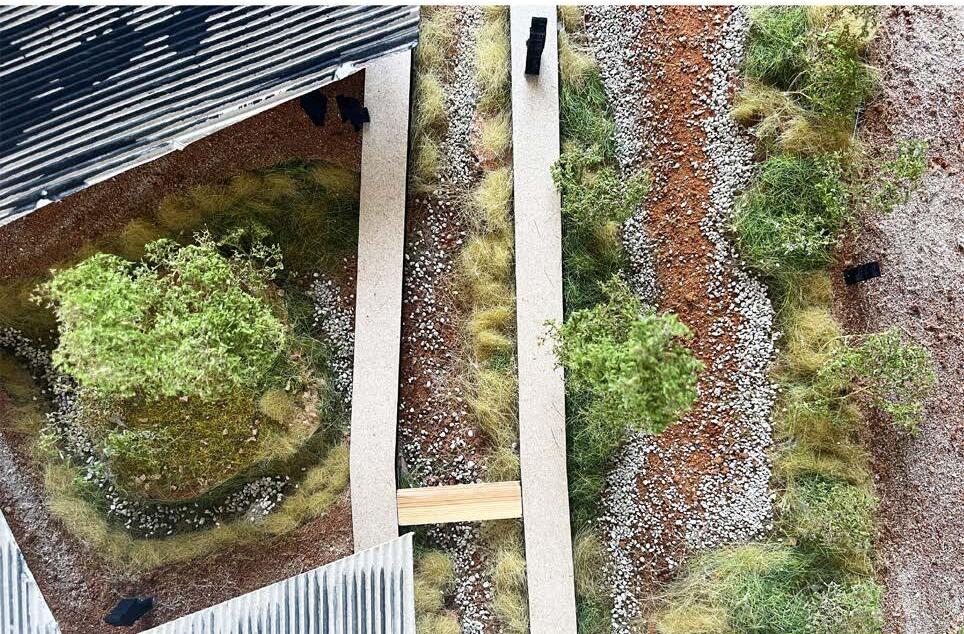

Scale V: the Cambamba river

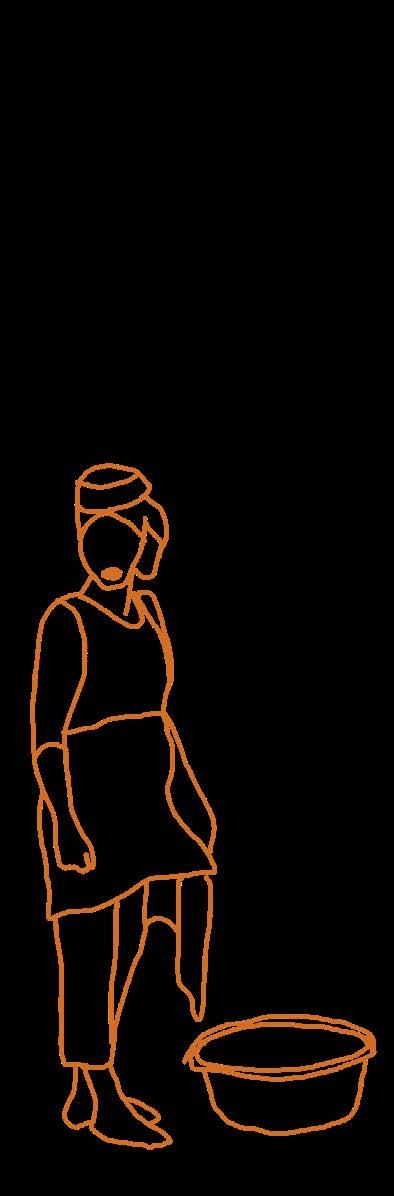

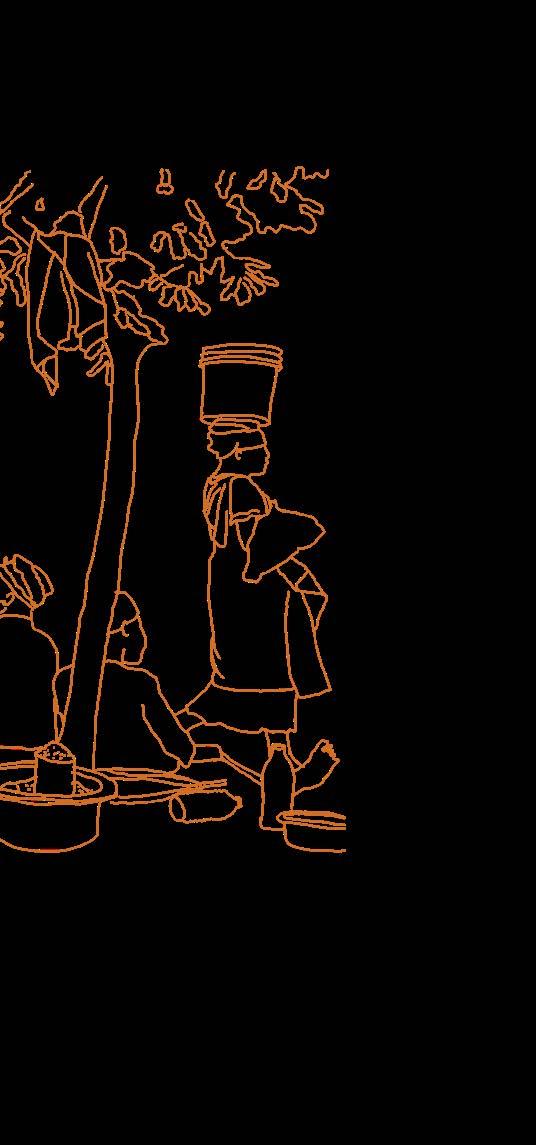

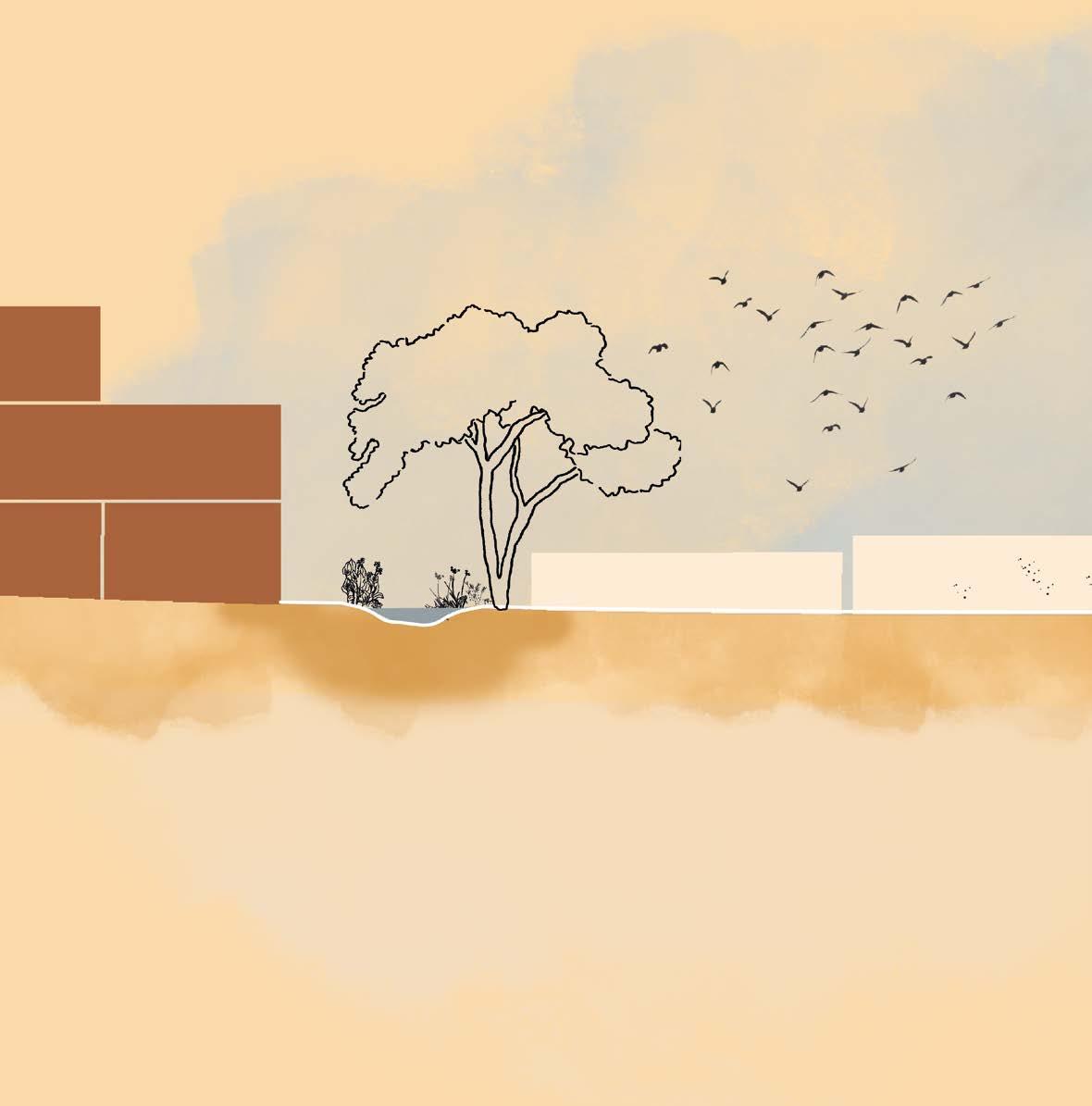

Scale VI: The guardians of the Cambamba

GLOSSARY

1º de maio – 1st of May

Cacimbo – dry season from May to September

Cambamba – a river that flows through Luanda

Candongueiro - the popular name for vehicles used to transport passengers in Angola, usually a blue and white painted van

Cantinton - the name of the formal market located at the western edge of the project area. It is where many zungueiras buy food in large quantities to sell it on the streets of Luanda

Centralidades - Housing projects with adequate basic sanitation, well-organized streets, and high-quality administrative services. Additionally, public safety is one of the advantages most appreciated by residents living in the centralities

Cubico – home, your own private place, it can be a small room or the whole house

Fiscal - an inspector responsible for imposing fines on street vendors

Kikanzu - Neighborhood; village; family

Kupapata - term originating from the Umbundu language, spoken in the southern part of Angola; a three-wheeled motor vehicle used as a taxi for

transport people and goods

Kwanza (kz) - the local currency and the name of the main river that flows south of Luanda. 1000 kz = 1 euro

Musseque – slum, favela, an area where construction is not regulated. 80 percent of the population of Luanda lives in such areas

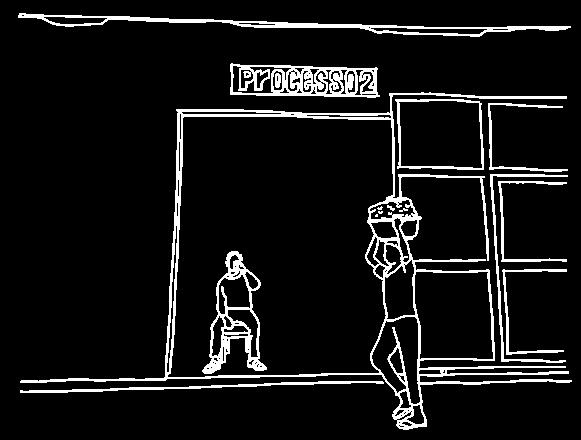

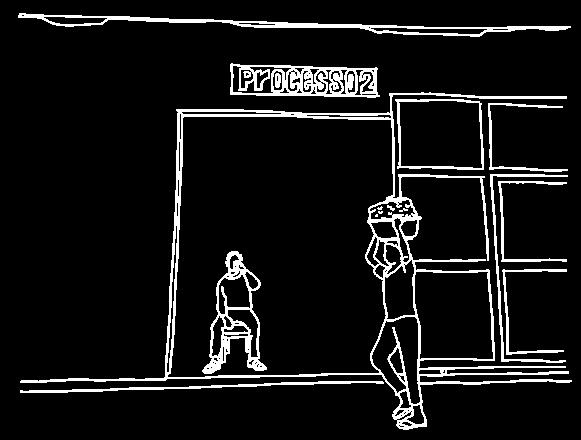

Processo - paid storage space for food

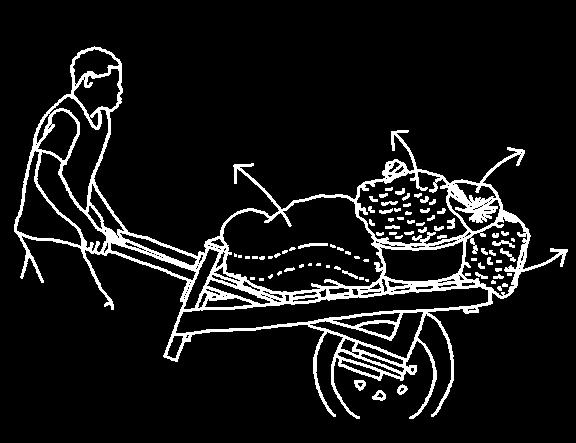

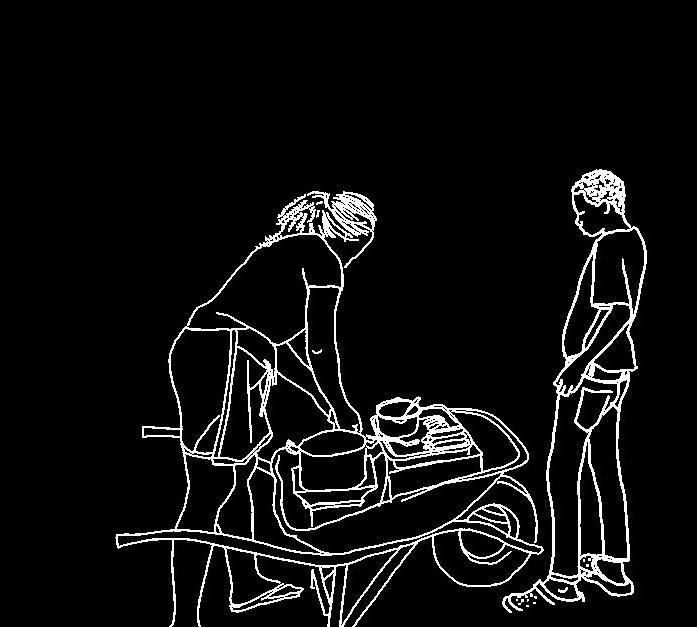

Trabalhador - the person in the market who transports large quantities of food using a wheelbarrow in exchange for payment

Vala – a channeled river with high concrete walls, usually filled with highly contaminated, dirty water and garbage

Xará - namesake; someone who shares their name with another person

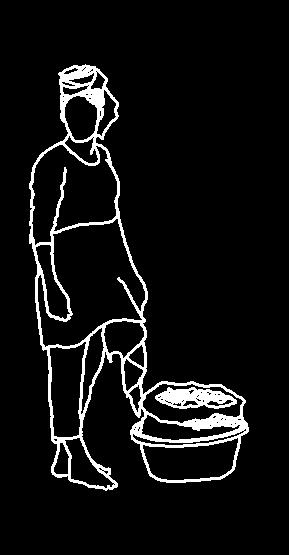

Zungueira – a female street vendor

(To my Angolan grandmother and grandfather…)

Para a vovó e o vovô...

Contrasts (2022) by Kim Praise

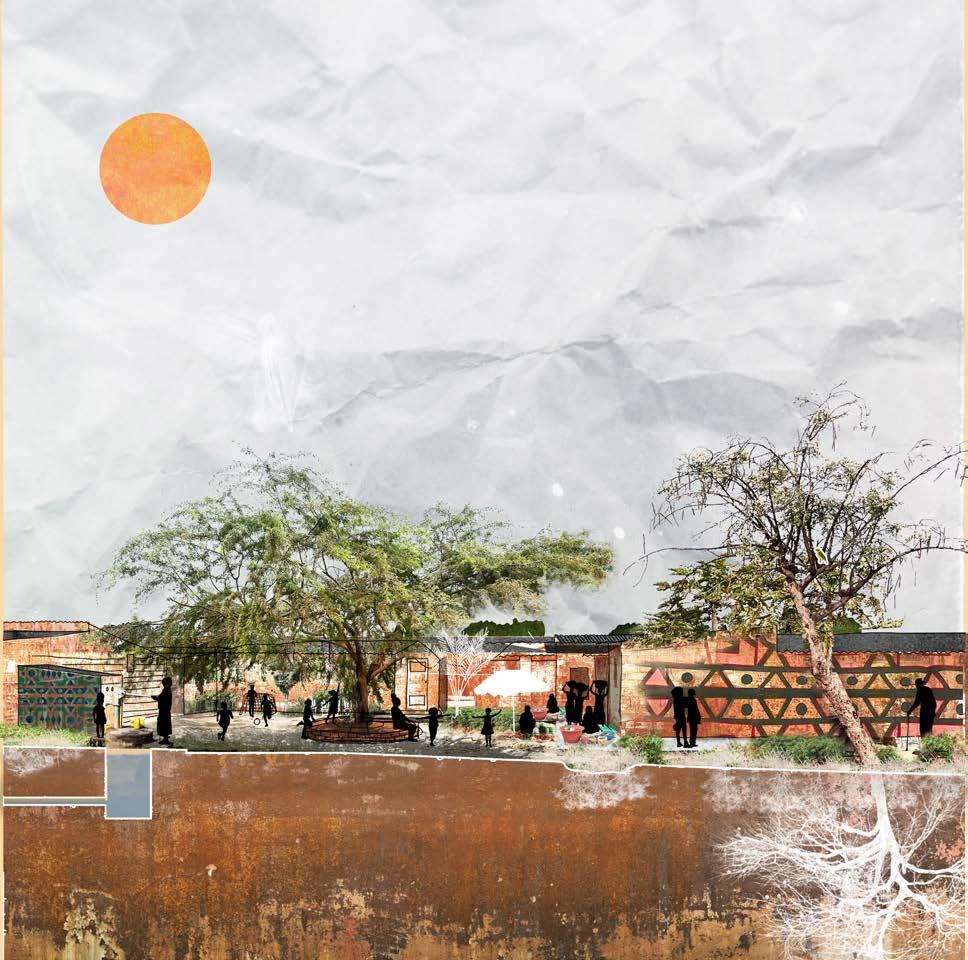

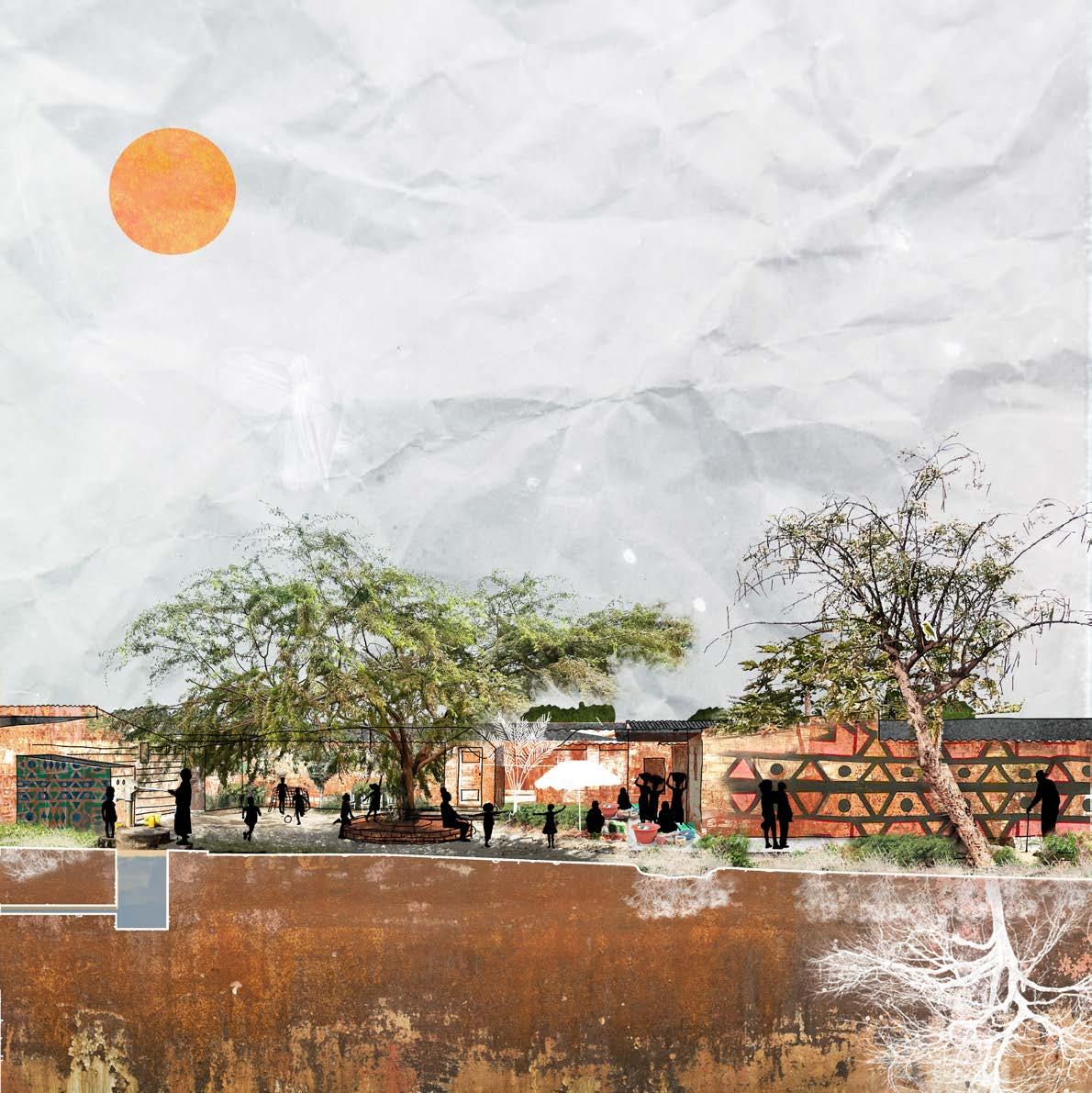

KIKANZU CAMBAMBA

During my first visit to Luanda I was amazed by the liveliness of the public space. City life is fascinating and very dynamic. Streets and squares in Luanda are so busy and intensively used that the road and the sidewalk become a shared space where people meet, children play, products are bought and sold, etc. In Luanda, public space is created organically rather than through formal planning. Especially zungueiras and children bring life, color and shape to these places. That is why this project focuses on them and on their most common living environment: the musseque.

The landscape of the musseque and therefore also the interactions and activities that take place there are the most vulnerable to the enormous consequences of our changing climate, namely flooding, water nuisance and heat stress. In Amsterdam, climate adaptation has become a core value for design and is already anchored in policy making, but in Luanda the urban area is growing so fast that planners cannot keep up with climate adaptive interventions.

The resilience that we as landscape architects strive for in urban landscapes is still invisible in Angola and this graduation project seeks to change that.

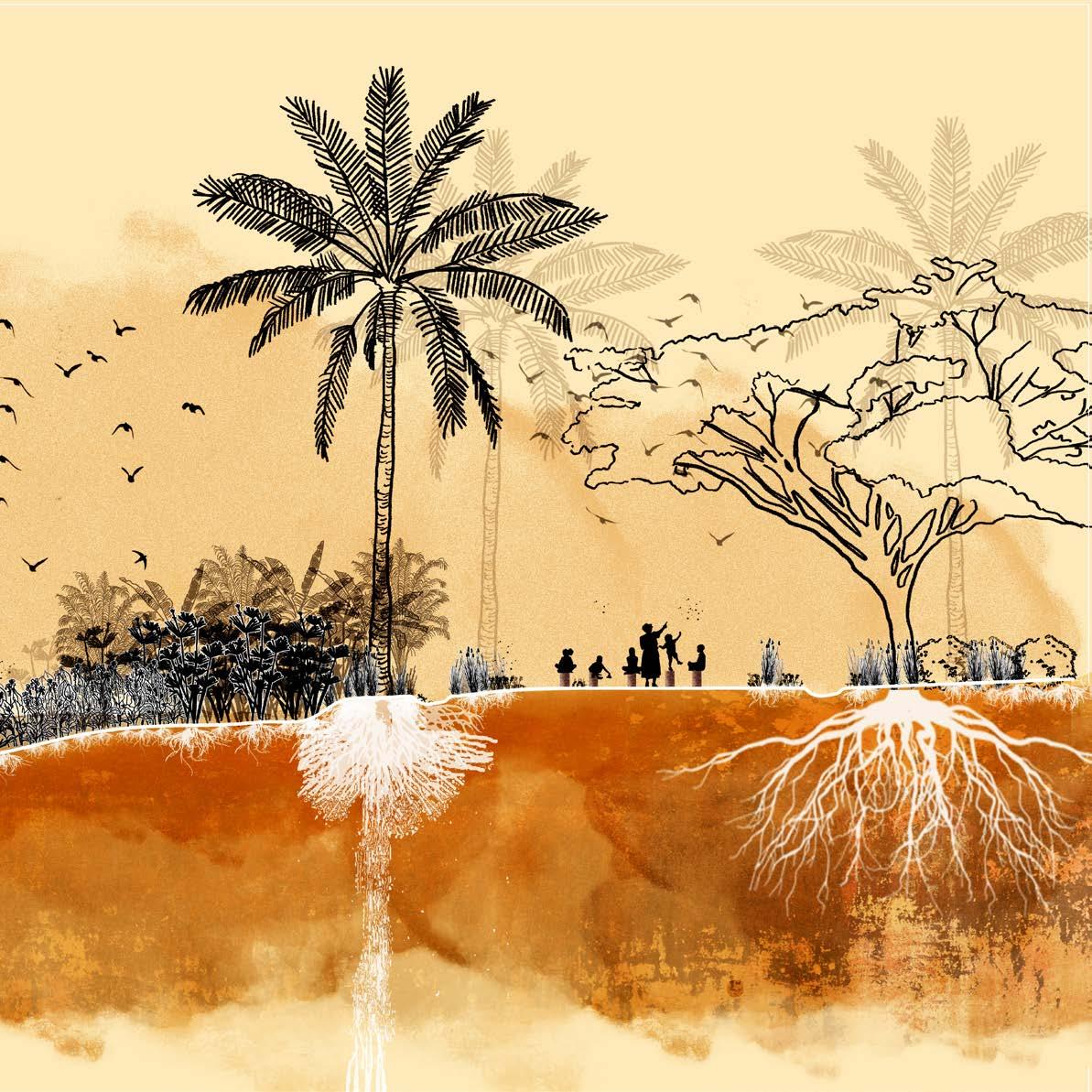

Looking at the natural conditions of the landscape around the Cambamba river in the Cassequel district, I see the richness of Angolan nature as a key to solutions for flooding, water nuisance and heat stress in the public space. The river becomes a source of life and change in this neighborhood.

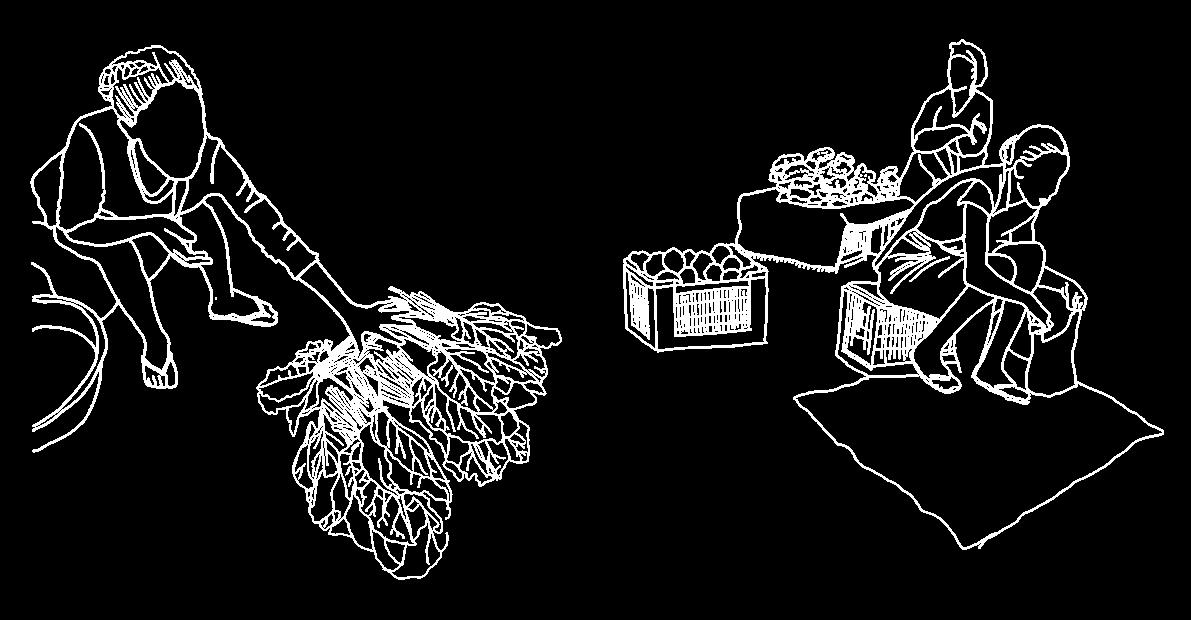

The design builds on the existing qualities of the place and strengthens what is already there: a resilient community. Schools, informal markets, green-blue streets and meeting places support a community that is able to adapt. People live close together, seek shelter under trees or canopies, sell goods, take care of their families and maintain a rich network of daily interactions.

The river functions as a connector – the lifeline and driving force behind change in Luanda’s urban environment.

CLIMATE URGENCY

The public space, people’s daily lives and the particular interactions and activities in the public space are the most vulnerable to the enormous effects of our changing climate.

Change is inherent to mankind and nature but public spaces all over the world are not always adapted to it. In the Netherlands Climate adaptation has become a core design value and is already embedded in policy making. In Luanda, however, this mindset has yet to become commonplace. Author AA. Title of article. Title of Newsletter. Year Month Day of publication;volume(issue):pages.

Cities are key to combating climate change and Rain destroys more than 700 homes. Jornal de Angola. 2023 April 1th

Luanda © Sam.Seyffert

An expanded assessment of risks from flooding in

image 2 to 6: J. Mendelsohn, S. Mendelsohn and N. Nakanyete (2010).

Luanda

All neighborhoods of Luanda and the public spaces now face enormous challenges (sewage, garbage, traffic, etc.). Rodrigues tells me that the one we are in now, Morro Bento, is on a hill surrounded by ditches, but without sewage. A missed opportunity to save this area from heavy rain.

When I asked if there are good parks or gardens, he laughed and said, “There are, but I wouldn’t call them parks. It’s just a bunch of plants in areas that haven’t been built yet. Some don’t even have benches. The Jardim do Amor (Garden of Love) is one of those places where people go to take wedding photos. It’s not pretty, but it is famous. This roundabout here was recently built and is beautifully planted in my opinion, but again: it’s not a park.’’

The streets are so full of vendors, fruits, and vegetables of all kinds that one can’t even see the sidewalk. Between the busy streets, we enter a narrow ally that leads us to even smaller alleys. Everything has a beige and gray hue, but I see some plants outside people’s homes here and there. Adingui and his wife let me into their house and show me where they sleep and store their food. Even though it is dark, the temperature is higher than outside the house. The climatic adaptation of these houses is very low, and locals constantly face the consequences of heavy rain inside their home. Adingui and his wife gestured how the water enters and washes everything away and how intensely they each time must throw the water away with buckets.

Unfortunately, a few meters away, what is supposed to be a waterway to the sea is a garbage dump site. Children also go there to find something they can play with and then climb back up. Among all the problems in public spaces, garbage and the lack of sewage systems are the biggest.

In addition to these problems there is a lack of vegetation that provides shade for the endless lines of people waiting for the buses, and few adequate or hygienic places for street vendors, or places for the many children I see to play. And they are, in fact, the future generation of this country. My two sisters are also part of this generation and the only places they can play safely is inside their complex, at school, or in paid places, like theme parks. Therefore, not all children have access to a clean, safe, and pleasant environment to play.

I wonder what Luanda will be like for them in a few years. Will the streets still be full of life, colors, and traffic noise? Will street vendors still be sitting on the streets or snaking between cars? And what food are they going to sell?

Excerpt from my Luandan diary

Scale I AFRICA

People navigate the the waterways of Makoko waterfront community in Lagos, Nigeria, May 15, 2018.

(AFP Photo)

African public space

In South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia extended drought has been leading to water shortage, which negatively impacts urban activities dependent on water and how people wash and prepare their food.3

In major coastal cities such as Luanda, Lagos, Dar es Salaam, Alexandria, Abidjan, Cape Town, and Casablanca, sea level rise, heavy rainfalls, and consequent flooding and erosion are rapidly destroying people’s homes and lives. Traditional practices and the use of public spaces are at stake in addition to the current socio-economic problems such as poverty, malnutrition, violence, and inequality.

There are two possible directions to consider for the future landscape of Luanda. One is to surrender to the effects of climate change such as flooding and embrace a new way of living with and in water. Take Makoko in Nigeria for example, where houses are built on stilts and people move around with canoes. However, this would only be possible through a cultural and behavioral shift which leads me to consider another direction. Is there a way to turn these fragile landscapes into healthy ones without losing the informal street culture that is so characteristic of this city?

With this project, a new landscape emerges – one that embraces culture and climate adaptation. When designing for Luanda’s public spaces, solutions should be thought to ensure that specially zungueiras and the younger generations are stimulated, and safe, and awareness for them comes from other age groups and social classes.

The formality that adapts public spaces to climate change and therefore safeguards the people and their activities in those spaces.

3 “South Africa drought: Cape Town faces water rationing,” BBC News, January 30, 2018 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-42896833

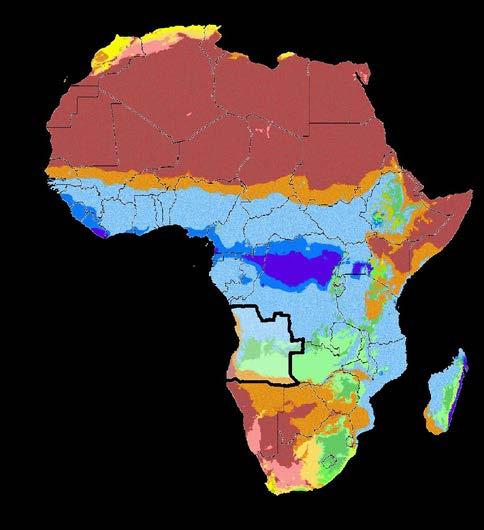

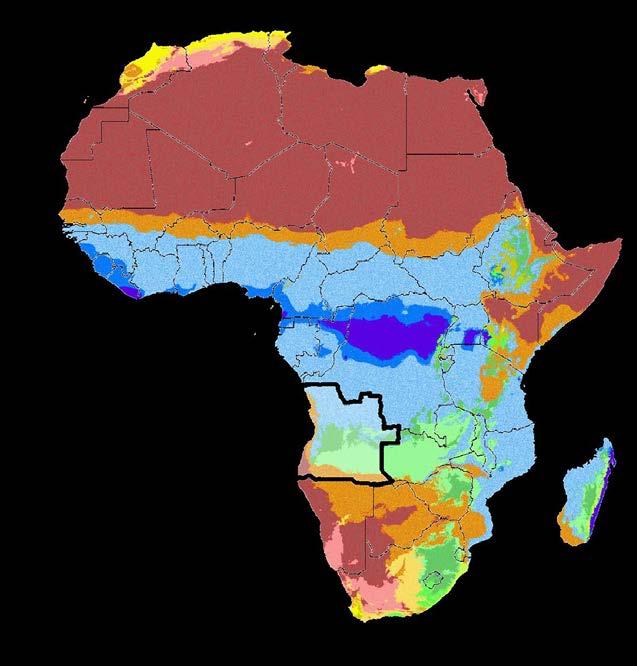

Adapting a place to the climate of its location begins with understanding the existing conditions. Africa, being a vast and diverse continent, cannot be perceived as a place with one climate. Angola, in particular, has its own specific climate and natural richness.

Angola has a variety of ecoregions 4 ranging from tropical savannah in the north to a hot, arid desert region in the south. The capital, Luanda, lies withina strip of grassland plains without closed forests, located near rivers and lakes. This long region extends along the coast and southward towards Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

Effects on African hot arid areas

- temperature rise - drought vs precipitation - desertification - extreme weather events - water shortage - impact on agriculture - ecosystem changes - social and economic impacts

4 an area defined by its environmental conditions, esp climate, landforms, and soil characteristics Collins English Dictionary. Copyright © HarperCollins Publishers

Tropical, rainforest (Af)

Tropical, monsoon (Am)

Tropical, savannah (Aw)

Arid, desert, hot (BWh)

Arid, desert, cold (BWk)

Arid, steppe, hot (BSh)

Arid, steppe, cold (BSk)

Temperate, dry summer, hot summer (Csa)

Temperate, dry summer, warm summer (Csb)

Temperate, dry summer, cold summer (Csc)

Temperate, dry winter, hot summer (Cwa)

Temperate, dry winter, warm summer (Cwb)

Temperate, dry winter, cold summer (Cwc)

Temperate, no dry season, hot summer (Cfa)

Temperate, no dry season, warm summer (Cfb)

Temperate, no dry season, cold summer (Cfc)

Cold, dry summer, warm summer (Dsb)

Cold, dry summer, cold summer (Dsc)

Cold, dry winter, cold summer (Dwc)

Cold, no dry season, cold summer (Dfc)

Polar, tundra (ET)

Polar, frost (EF)

SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN

LUANDA

Tropical, Tropical, Tropical, Arid, Arid, Arid, Arid, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Temperate, Cold, Cold, Cold, Cold, Polar, Polar,

TROPIC OF CAPRICORN 23º5’S

CAPRICORN 23º5’S

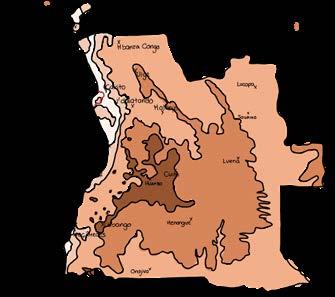

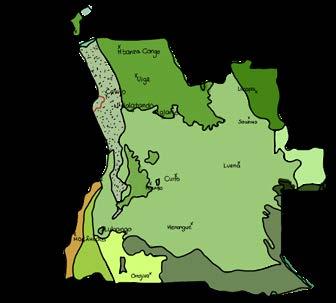

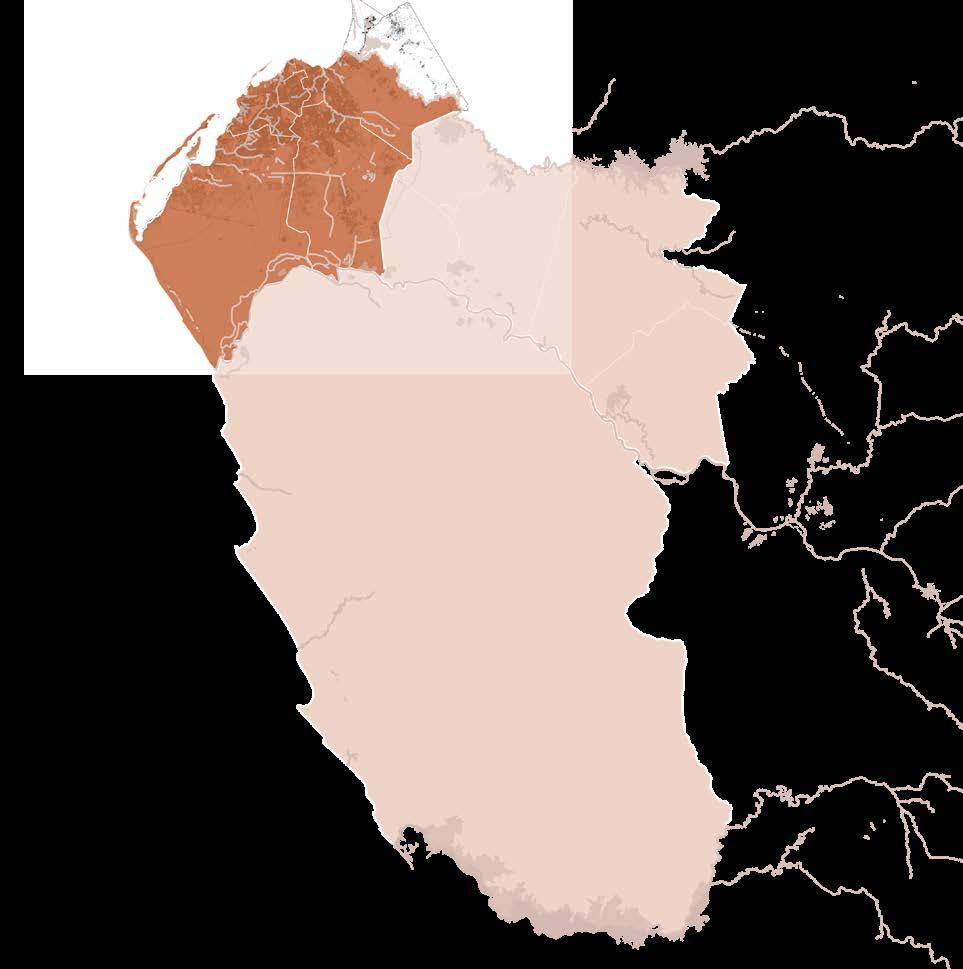

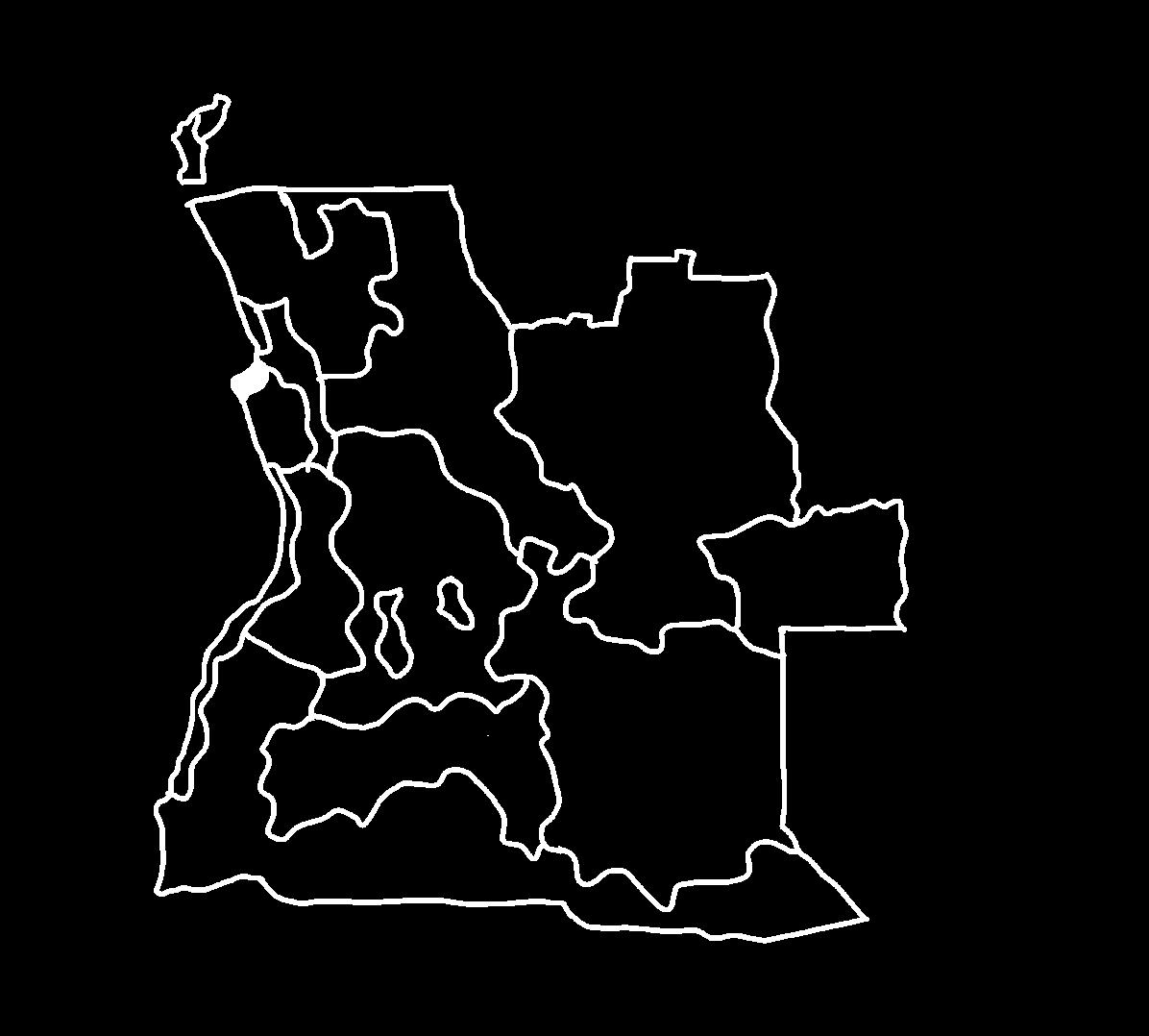

Scale II

ANGOLA

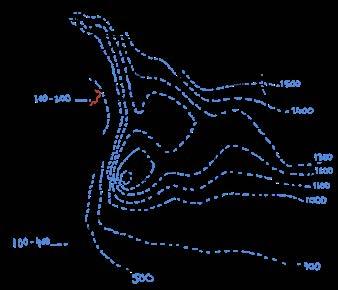

Topography

2620 (Moco mt.) - 2000

2000-1250m

250-1250m

70-250m

0-70m

Ecoregions

Central African Mangroves

Zambezian Cryptosepalum Dry Forest

Western Zambezian Grassland

Zambezian Baikiaea Woodland

Southern Congolian Forest-Savanna Mosaic

Angolan Montane ForestGrassland Mosaic

Western Congolian ForestSavanna Mosaic

Angolan Miombo Woodland

Angolan Scarp Savanna and Woodland Kaokoveld Desert

Namib Escarpment Woodlands

Angola Mopane Woodland

2. Giraffes in scarp savanna and woodland south of Luanda

1. Miradouro da Lua

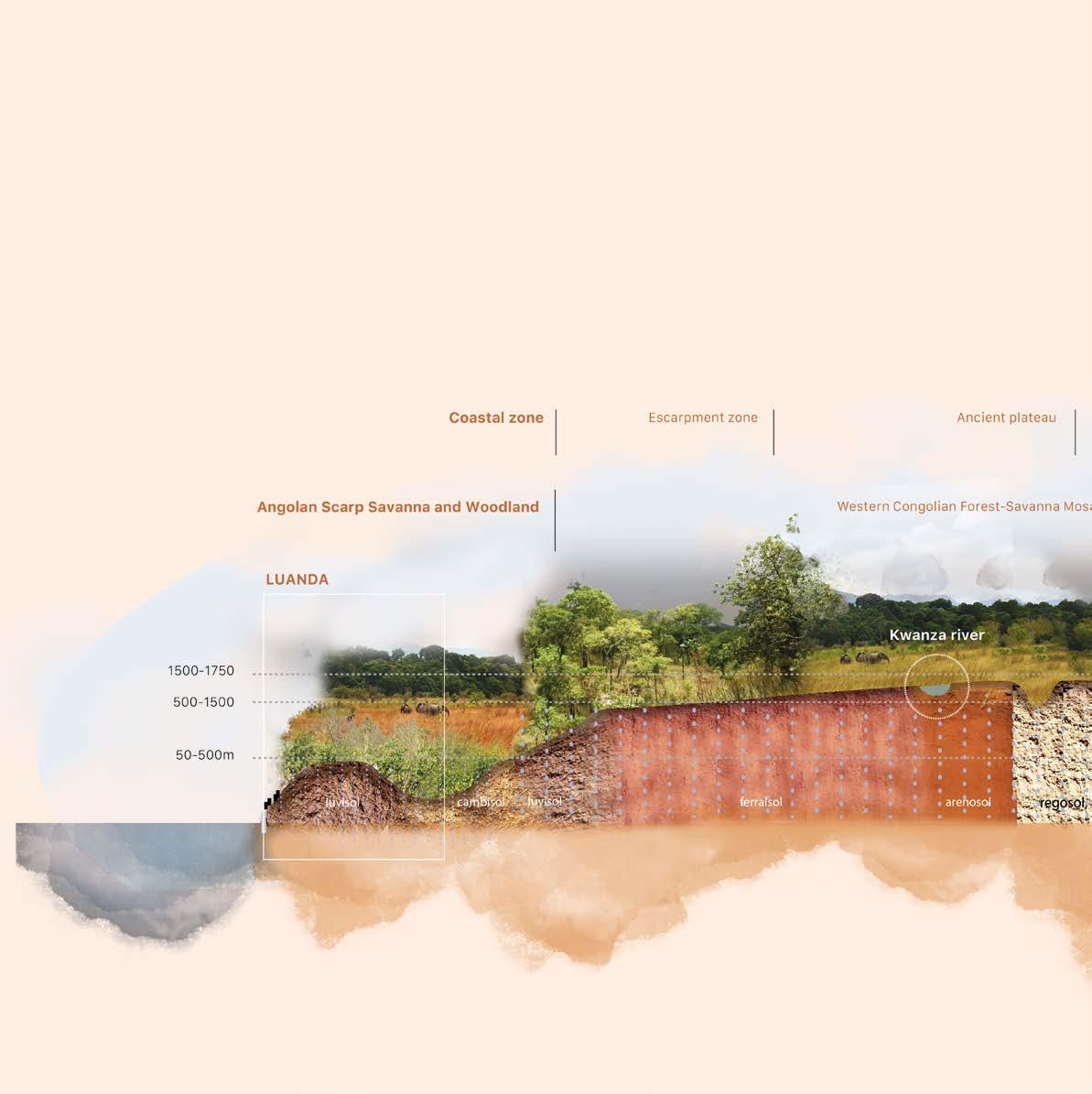

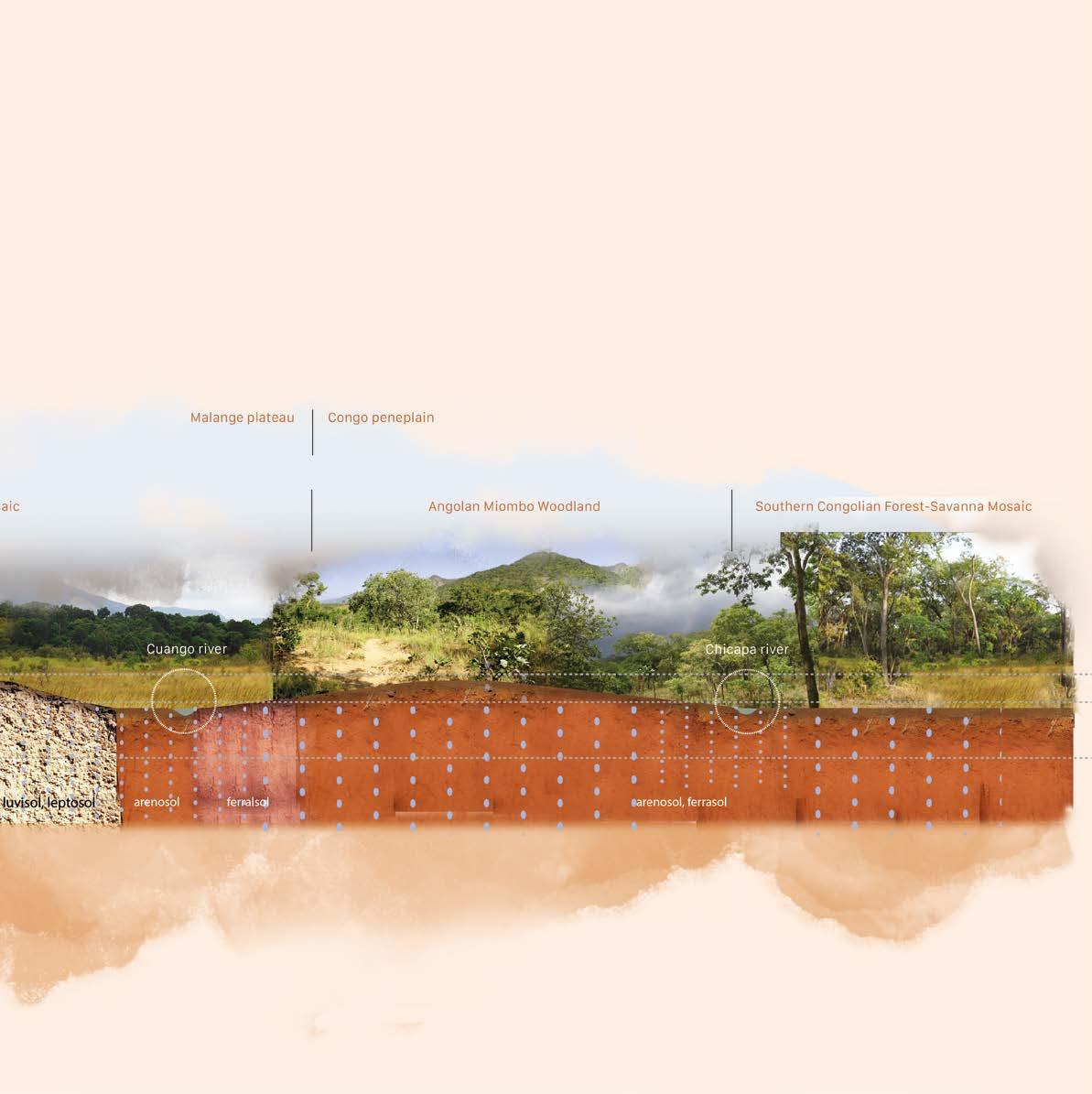

Soil types

luvisol (Luanda)*

luvisol Cambisol

*Luvisol - surface accumulation of humus overlying a layer of clay and iron; fertile soil

Geomorphological layers

coastal zone

escarpment zone

marginal mountain chain

ancient plateau

Annual rainfall

average rainfall of Luanda:

300-500 mm

5. flooded street in Morro Bento

3. luvisol soil

4. coastal zone with Atlantic Ocean in the horizon

6. Kwanza river, south of Luanda

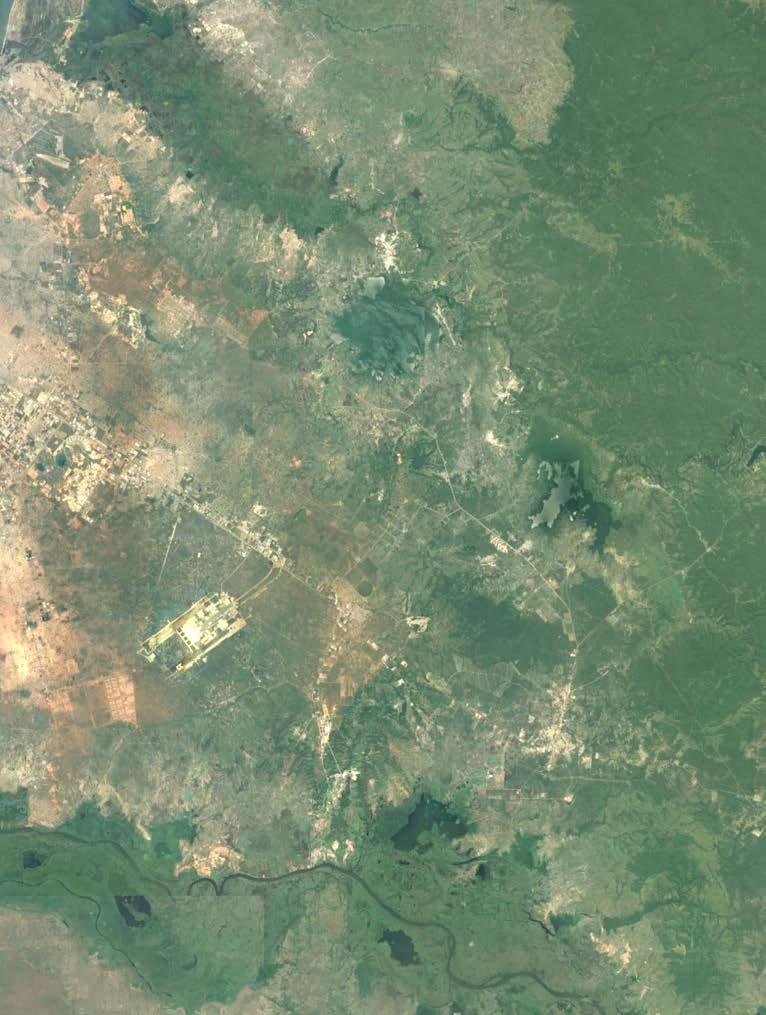

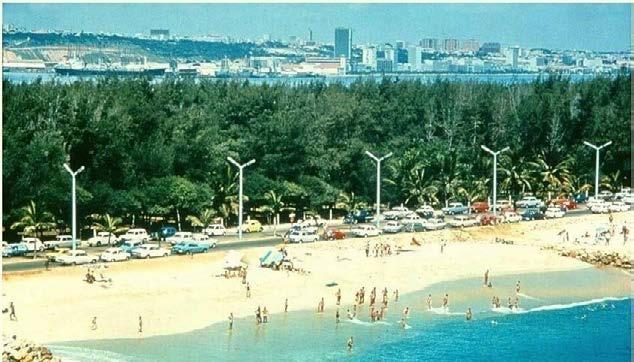

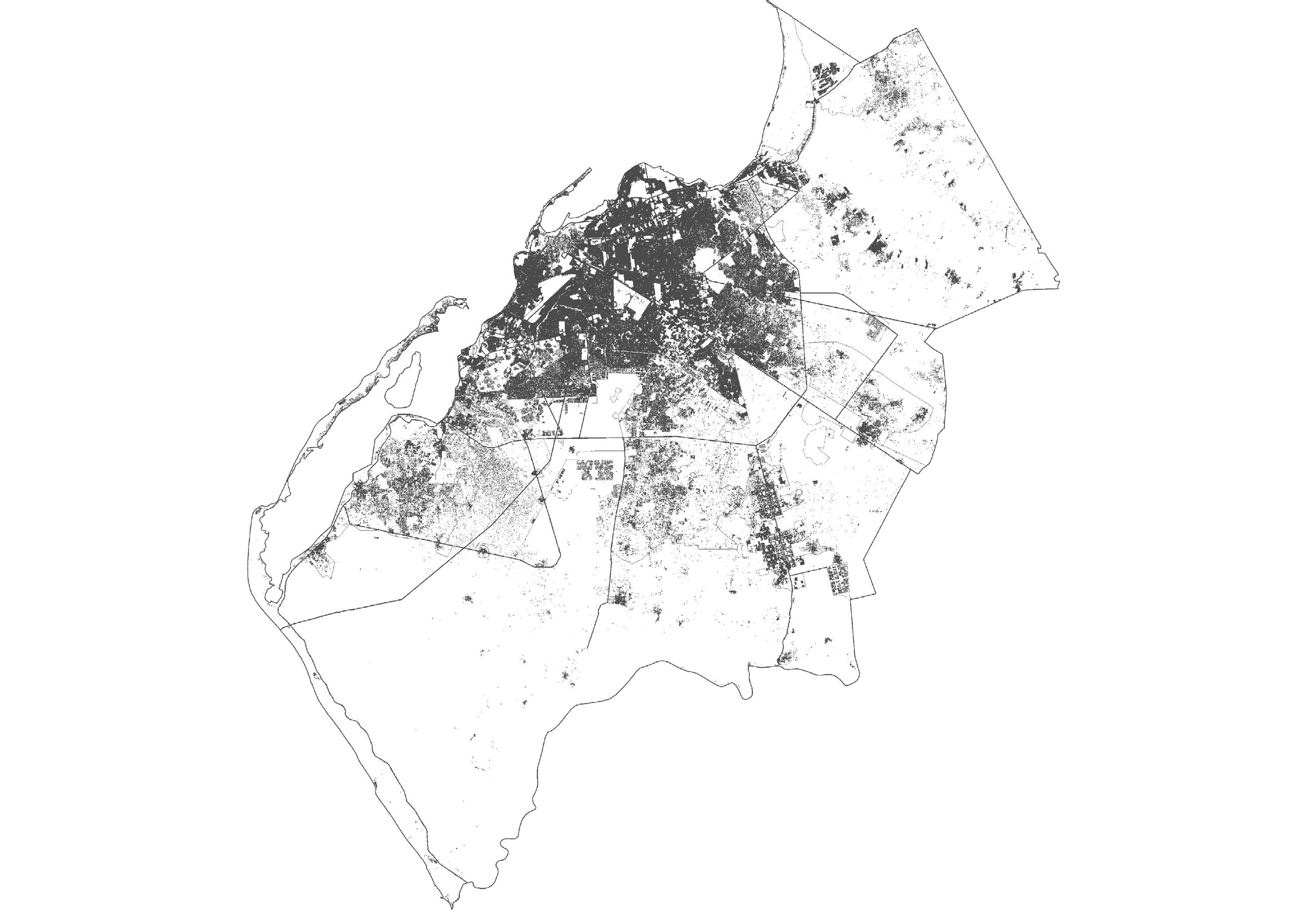

One would expect that the wealth of natural ecosystems/landscapes would be visible in Luanda, but due to urbanization, very little ecology and biodiversity can be seen in the capital. A series of historical events have strongly transformed Luanda from a harbor village to a sprawling metropolis of 6,9 million inhabitants. Today Luanda presents itself as a bare city where non-native vegetation is planted to imitate the ideals of Western urbanism.

road areas large urban areas cleared areas

Areas in Angola where substantial landscape changes have occurred in recent years

B. J. Huntley, V. Russo, F. Lages, N. Ferrand (2019). Biodiversity of Angola. Science & Conservation: A Modern Synthesis; page 135

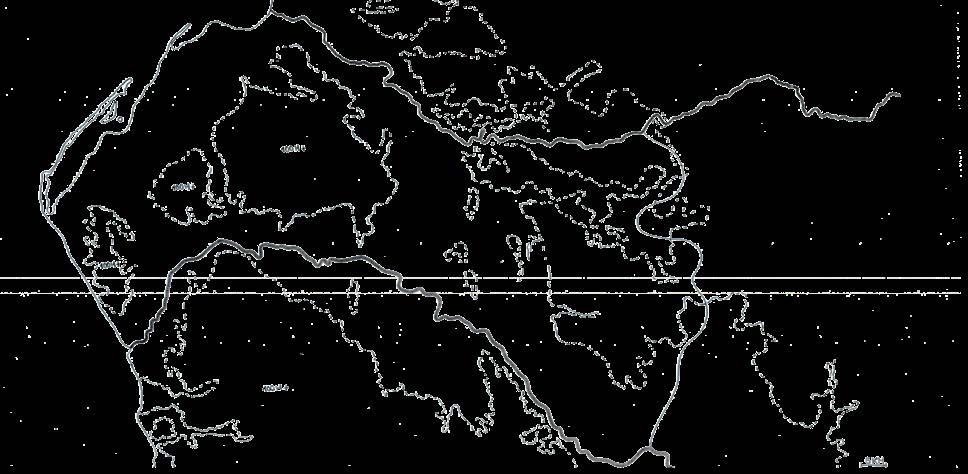

Horizontal section through Angola

A horizontal section through Angolan landscape at the latitude of Luanda shows us a beautiful gradient: from a patchwork of forest and savannahs, to woodlands covering the hills, taking us back to savannahs and woodlands the near the coast.

Scale III

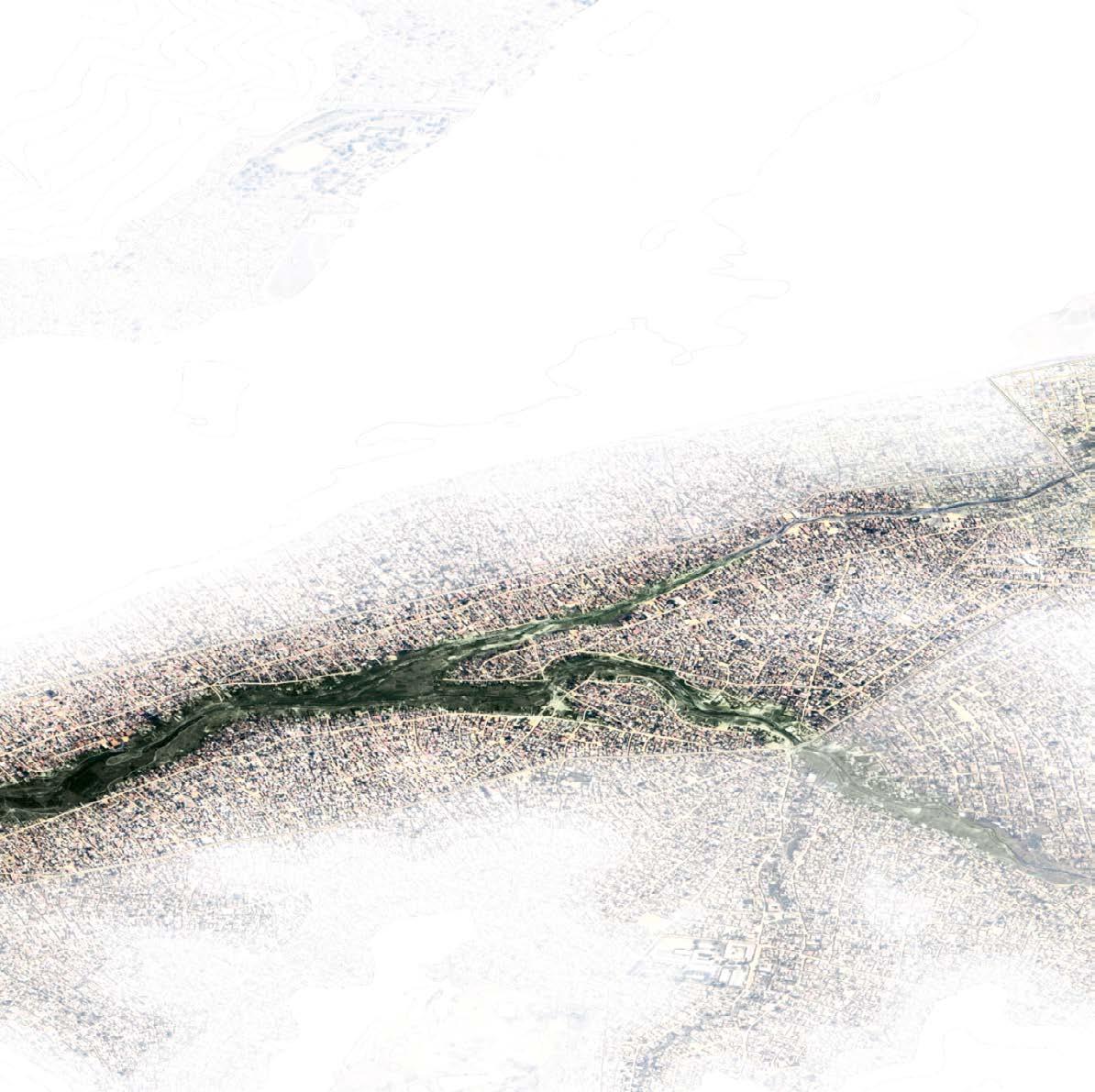

LUANDA

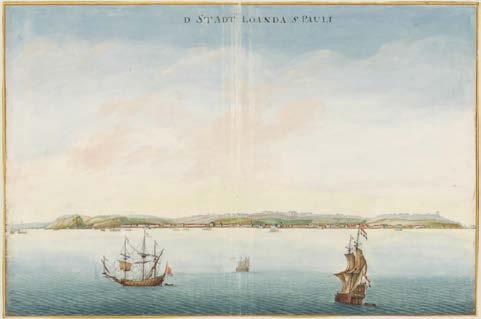

A heavy past: Why safeguarding Angola’s

culture is important

For centuries, the dignity, values and beliefs of the Angolan people were suppressed through slavery, colonization and war. I firmly believe that designing for the future of Luanda’s inhabitants should focus on safeguarding the indigenous culture, rather than applying European design principles that could lead to further degradation of habits and customs.

VI - Bantu and later the Congo kingdom occupied a territory from the Cameroon until the Kwanza bassin

1482 - First Portuguese ancor in the Kwanza river mouth

1575 - trading post São Paulo de Loanda. Slaves being taken to Brasil

XVIIPortuguese lost their independence to Spain - the Netherlands strikes. In 1640 Portugal reconquer independence again

XIX - the borders of Angola are defined. The natural resources of the country start being explored

2002 - End of civil war

1974 - The city of Luanda in 1974 had a capacity of only 400,000 residents

1975Independence of Angola. Agostinho Neto is the first president but soon after that the civil war starts

1961 - Colonial war between Portugal and Angola

source timeline: De Raeymaeker, J. (2012) À descoberta de Angola (Discovering Angola)

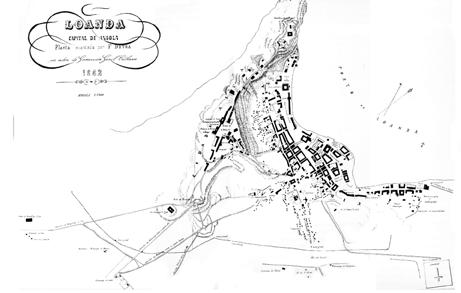

A city growing at a fast pace

D stadt Loanda S Pauli (ca 1665). Vingboons, Johannes (Nationaal Archief)

Gezicht op als voren van de zeezijde (ca 1665). Vingboons, Johannes (Nationaal Archief)

Luanda 1755. Pepetela (1990), Luandando. Pages 47-48

XX - More sistemic

Luanda 1862. Pepetela (1990), Luandando. Pages 70-71

Ilha, junto a entrada da floresta (Island, next to the entrance to the forest Facebook page: LuandaImagens dos velhos tempos

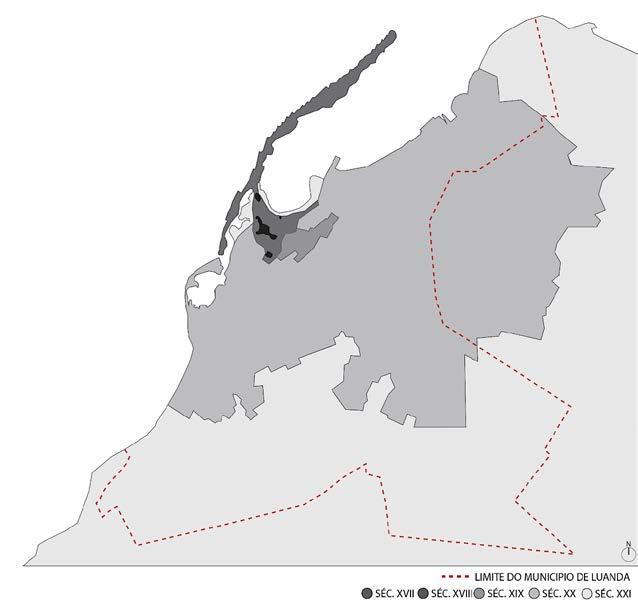

The growth of the city of Luanda

M. T. Pires (2014). Densificacão vs retracção: Que futuro para as reas autoconstruídas de Luanda? Repensar a transformação de um território urbano [Master’s thesis, Faculdade de Arquitetura de Lisboa)

First

time in Luanda (2014)

Luanda, a bare city

Angola = 25,7 mil inhabitants

Luanda = 6,9 mil inhabitants

We ruined the lung of Luanda. Bushy areas with manioc trees, agricultural areas have been destroyed for centralidades and neighborhoods. They were zones that fed the city.

interview with Vladimir Russo

Luanda’s inner city

Luanda’s urban area

A10 Amsterdam

Amsterdam’s city centre

Urban area of Amsterdam and sorroundings

lowest

Highest and

areas of Luanda

Rainwater runoff in Luanda

LANDSCAPE FIRST

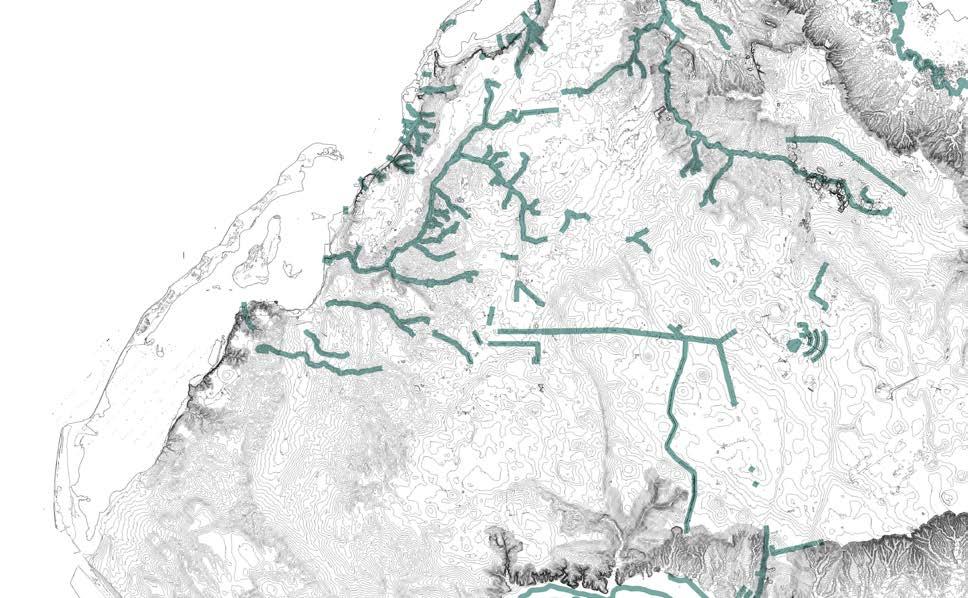

The metropolitan area of Luanda sprawls across terrain with elevation differences of up to 100 m.

The Dande basin defines the northern border of Luanda, whereas the Congo basin defines the southern border. These natural buffers that could collect excess rainwater from urban areas are too far away from the flanks of hilly areas where rainwater rapidly comes flushing down.

Additional waterways waterways will improve water inflitration in the highest areas avoiding less rainwater to runoff to lower areas

Slowing down water runoff vegetation on slopes stabilizes the soil preventing erosion and surface runoff

Water storage reservoirs prevent water from rapidly flowing into the inner city make it possible to store water during dry seasons

If the future of the city is conceived from the landscape, then each level of that landscape should serve a function in how the whole city manages (rain)water and mitigates flooding. Beginning from the highest level which can play a role in retaining water already in the higher parts, delaying excess water in the next level and retaining water for the dry season. Finally, the lowest level can protect the coast against sea level rise while also making room for rivers within the city itself.

Coastal protection protects populated areas against erosion caused by sea level rise and wind

Expanding river areas and creating buffers turning river areas into more vital environments and allowing the river to overflow its banks

A radical yet essential strategy for Luanda’s future

I can imagine that the Mundial neighborhood could potentially be embedded in an estuary landscape or that the Cassequel neighborhood could become the first climate-resilient neighborhood in Luanda? The informality of both these settlements poses a significant challenge in finding space for adaptive interventions. the Cassequel as a catalyst for climate resilience? the Mundial as the new Makoko?

Despite the intrinsic informality of those neighborhoods, I see opportunities even in the smallest alleys, where vegetation and rainwater can be used to temporarily store and reuse water, without the informal street culture being lost. This thought brought me to the musseques where I believe formality and informality together cloud shape a resilient way of living.

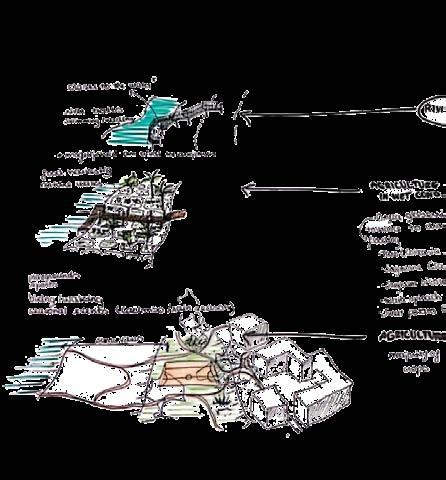

Enhance the spatial qualities of the musseque

street (shared space for pedestrians, cars & street vendors)

alley access to musseque (pedestrians only)

Make room for (rain)water Embrace Angola’s rich nature

buildings larger public spaces existing alley

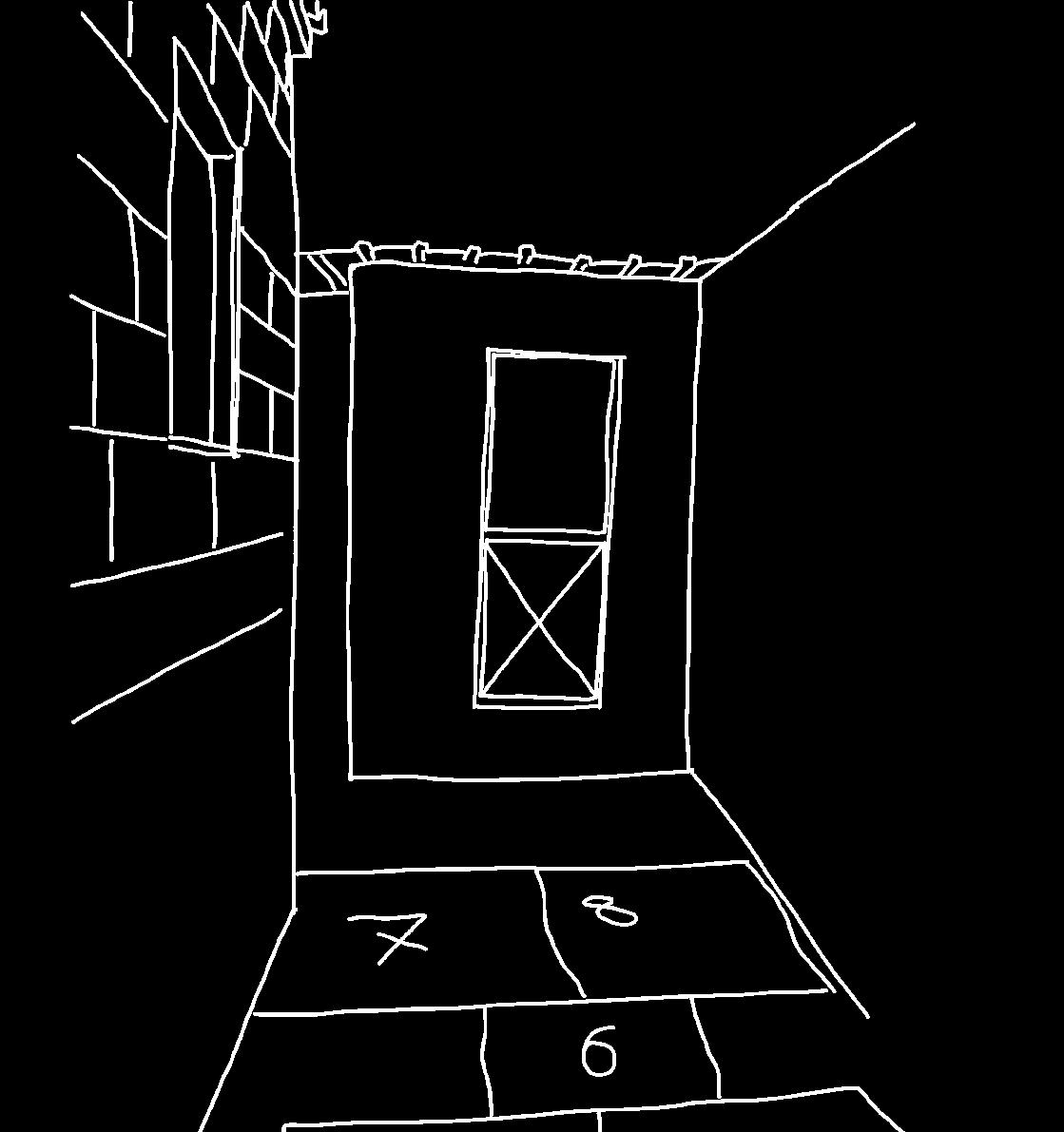

The public spaces within the Cassequel are quite narrow with the advantage that these spaces are cooler because of the amount of shadow. Vehicles can not enter the alleys so pedestrians are safer than along the road.

ornamental gardens

First ideas for resilience in an informal setting

sports

market place

playground

Scale IV MUSSEQUES

BEHIND THE CURTAINS OF THE MODERN CITY

The excuse (for the lack of planning in the development of Luanda) has always been the rural exodus. Because of war the amount of people looking for opportunities in cities grew so fast that the government was not able to plan, design and execute at the same pace. Infrastructure such as roads and sewage systems are still missing in cities such Benguela, Lobito or Baía Farta. People would build their houses where there was space and settle. Then, another relative would come to live there and an extension was made to the house in a space that is already quite limited. And then another one, and another one. This phenomenon of the so called musseques, has made it hard to physically enter them and make improvements.

Behind the curtain of the modern city, there are two urban phenomena: the musseques and the centralidades.

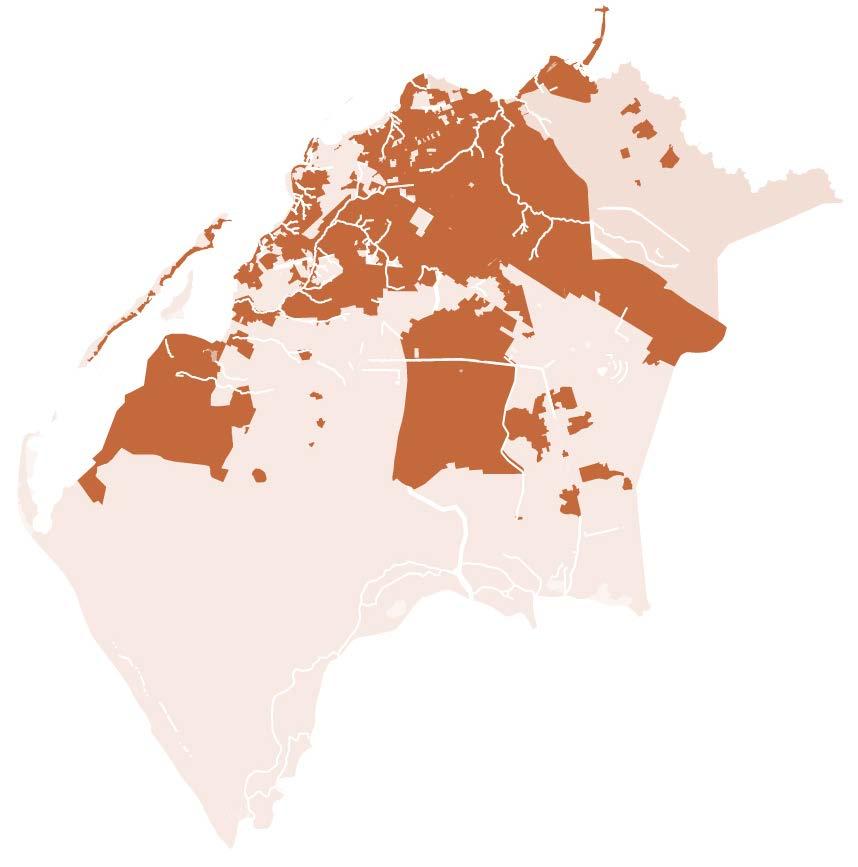

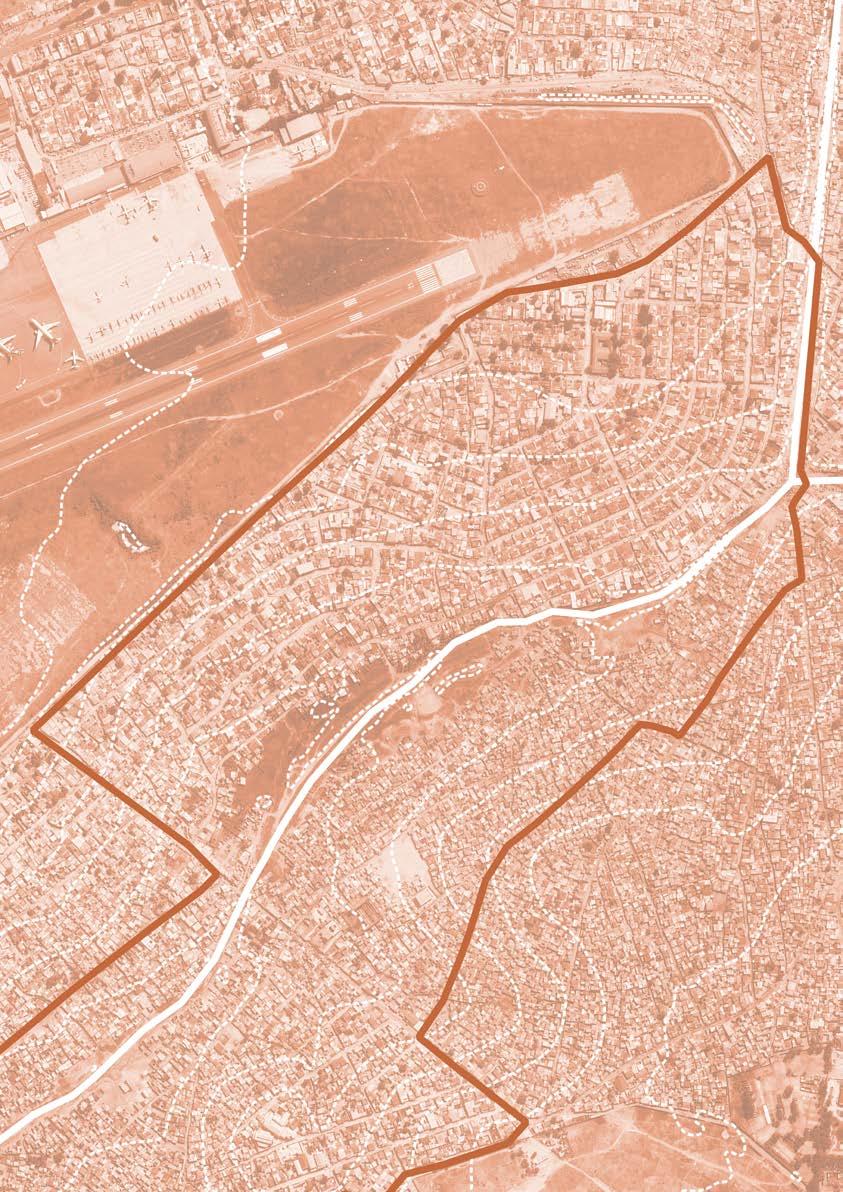

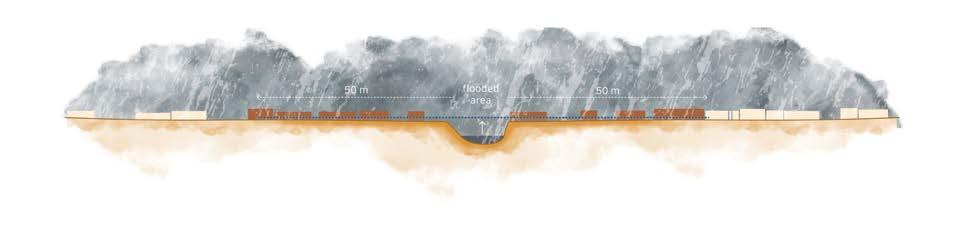

The musseques are mostly located either on slopes or in the lowest areas of Luanda and often near rivers. Therefore, these urban areas are most vulnerable to flooding and erosion. Flooding in these areas is predominantly caused by overflowing rivers and a dry, compacted soil through which water cannot infiltrate quickly.

Interview with Vladimir Russo

On thecontrary, the centralidade is a spatially organized housing area where people live in a safer environment and have access to a regulated supply of energy, water, and sewage system. It is a very hierarchical society, and huge contrasts are found in the way people live in Luanda. In the musseques where nearly 80% of the population lives, social problems and deficiencies remain the same or became worse.

According to the Census 2014, 87.2% of the private-owned urban housing stock of Angola result from self-construction, 57.2% of urban households have access to safe water, 81.8% have access to proper sanitation facilities, 50.9% have access to electricity and only 37.5% benefit from an adequate solid waste management system.5

5 https://unhabitat.org/angola

River Dry river

Areas <4 meters above sea level

Houses <4 meters above sea level

Areas within 20 meters of water to the river or waterline

Houses within 20 meters of water to the river or waterline

Areas with slopes greater than >15 degrees

Houses on slopes greater >15 degrees

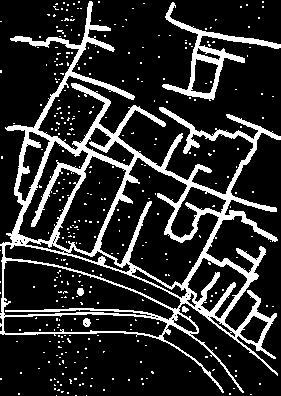

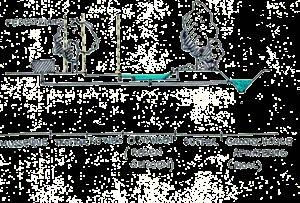

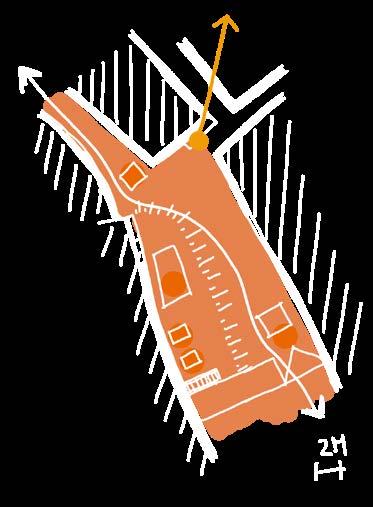

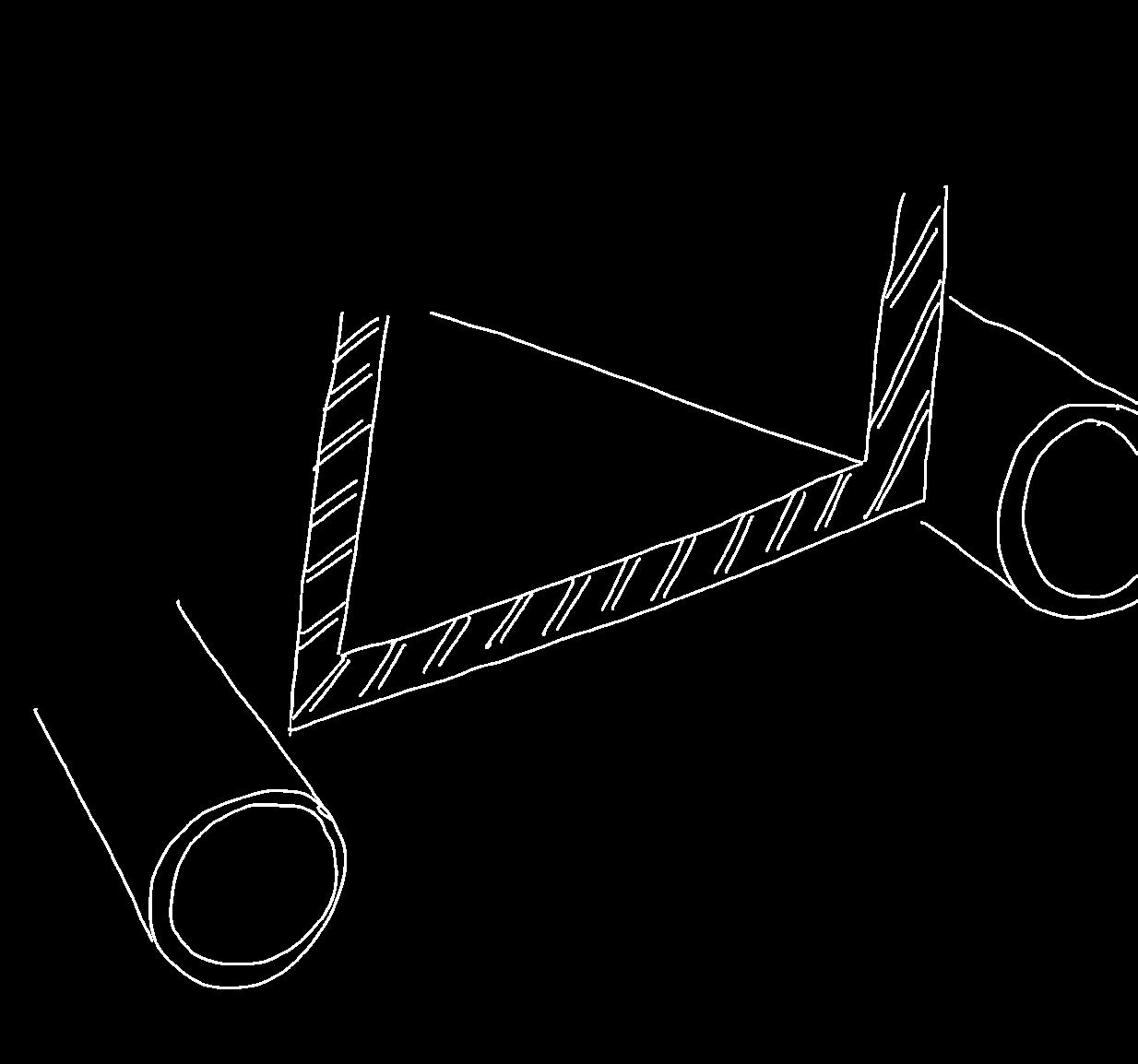

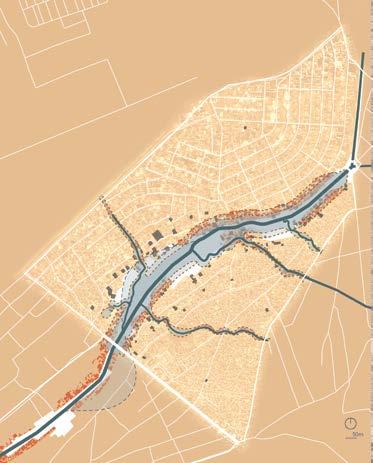

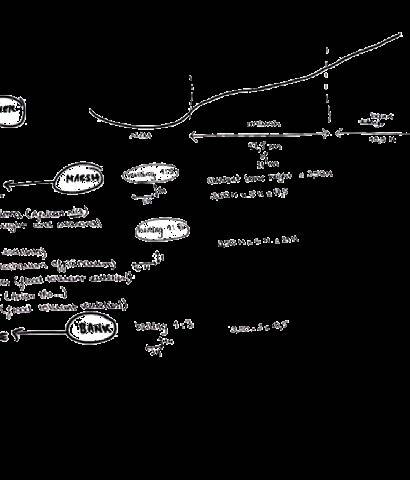

Scale V THE CAMBAMBA RIVER

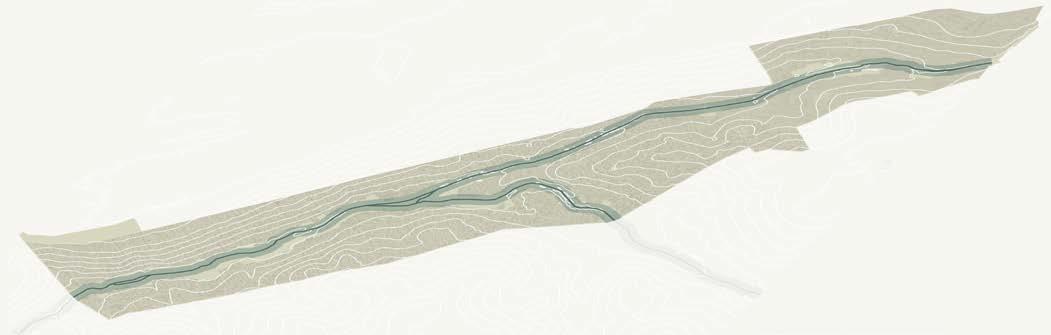

The influence of topography

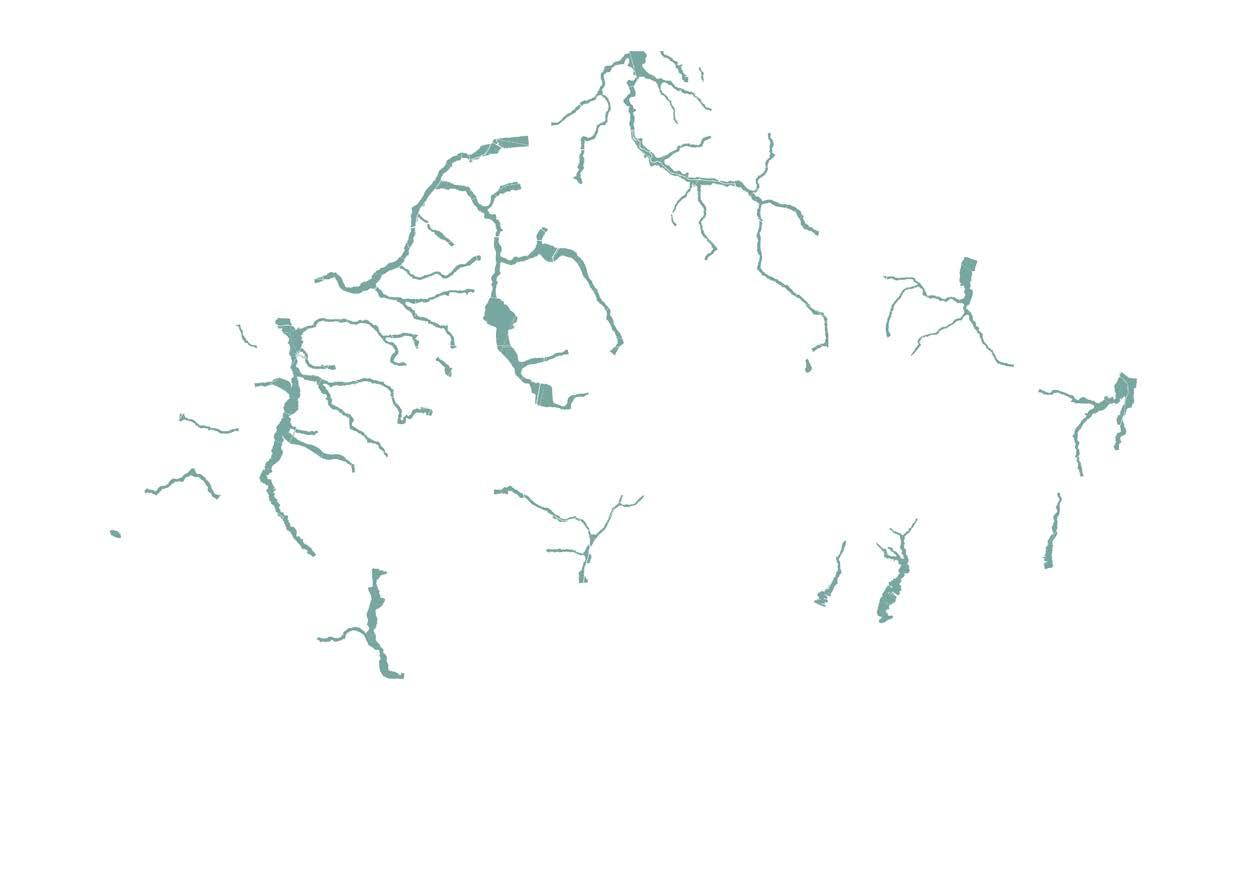

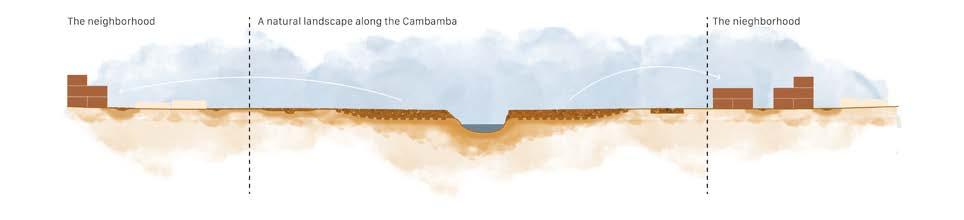

The Cambamba River basin crosses the most inhabited areas (most of them musseques) along its course.

It is not a river in the natural sense because it was dug by the Portuguese to facilitate and accelerate the drainage of rainwater through the long flat plateaus.

Professor Divaldo Domingos da Silva (hydraulic engineer at EPAL – Angolan public water company)

planned ETAR

1:100 years ood

ood point

musseque

district boundaries

channel direction of river ow Cambamba

alternative Cambamba (under construction)

ETAR (wastewater treatment)

planned ETAR

1:100 years ood

ood point

musseque

district boundaries

Zango social housing district

total length of the Cambamba

river = 64,90 km

alternative Cambamba = 19,39 km

Over time many houses have been built along or on the shores of the Cambamba. During the rainy season, rainwater flows down from the highest levels of the river. Water accumulates at the lowest areas of the river valley causing severe flooding in densely populated musseques like the Cassequel and the Malangino neighborhood. To prevent damage to the houses along the Cambamba, UTGSL is gradually channeling the river with high concrete walls. To create a vala, houses that were built to close to the river are demolished. People that live there are displaced to Zango, a social housing district 40 kilometers away from the center of Luanda. Social connections and a sense of community are broken by demolishing and

creating a different urban setting. That is why the climate resilience envisioned in this project must focus on enabling the inhabitants to continue their way of living in the neighborhood.

5km

baixo (low) Cambamba

medio (medium) Cambamba

alto (upper) Cambamba

5km

Blauwbrug

Amstelpark

VI

Scale

THE GUARDIANS OF THE CAMBAMBA

Stories of zungueiras and children in the landscape of the musseque

Luanda, 8th july 2024

Monday. 5:30 time of arrival in Luanda. The sun is not out yet, the weather is mild and not as hot as during the rainY season last time I came here. After I LEAVE the airport the sun is already out behind a densely clouded sky. Rush hour is starting and the sea of cars and people in between start to spread out through the city. I am trying to picture everything I had envisioned for this project but I rapidly get the feeling that everything I will see, hear, feel and learn while I AM here will change my perspective. I am very excited for my journey here and wonder what the outcome will be.

We go pick up my sister from school in Talatona, a neighborhood with brand new public spaces. Everything has to be irrigated, specially now that there is no rain. Some ditches were made in the planting beds to get the water flowing in between planting beds. What we can only dream of as a house plant grows enormously AND perfectly outside here in Luanda. sadly, not even these modern neighborhoods are free from the effects of climate change. A part of a wall has fallen out because of erosion caused by rainwater and now is the time of the year where these effects are very visible and dealt with.

The days are quite short comparing to the long summer days of Amsterdam and by the time the red sun accentuates the skies people are on their way home before it gets pitch dark.

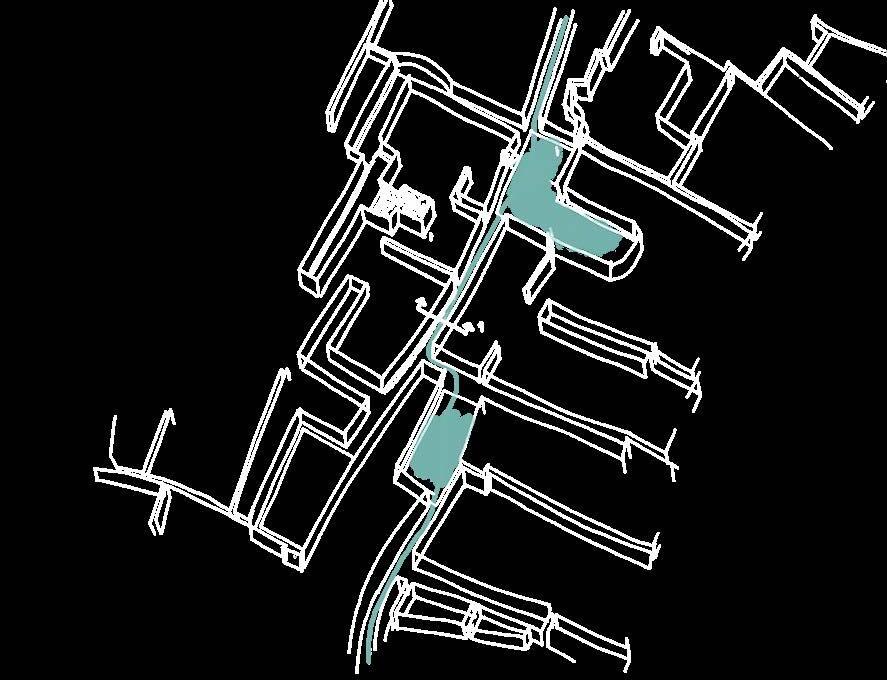

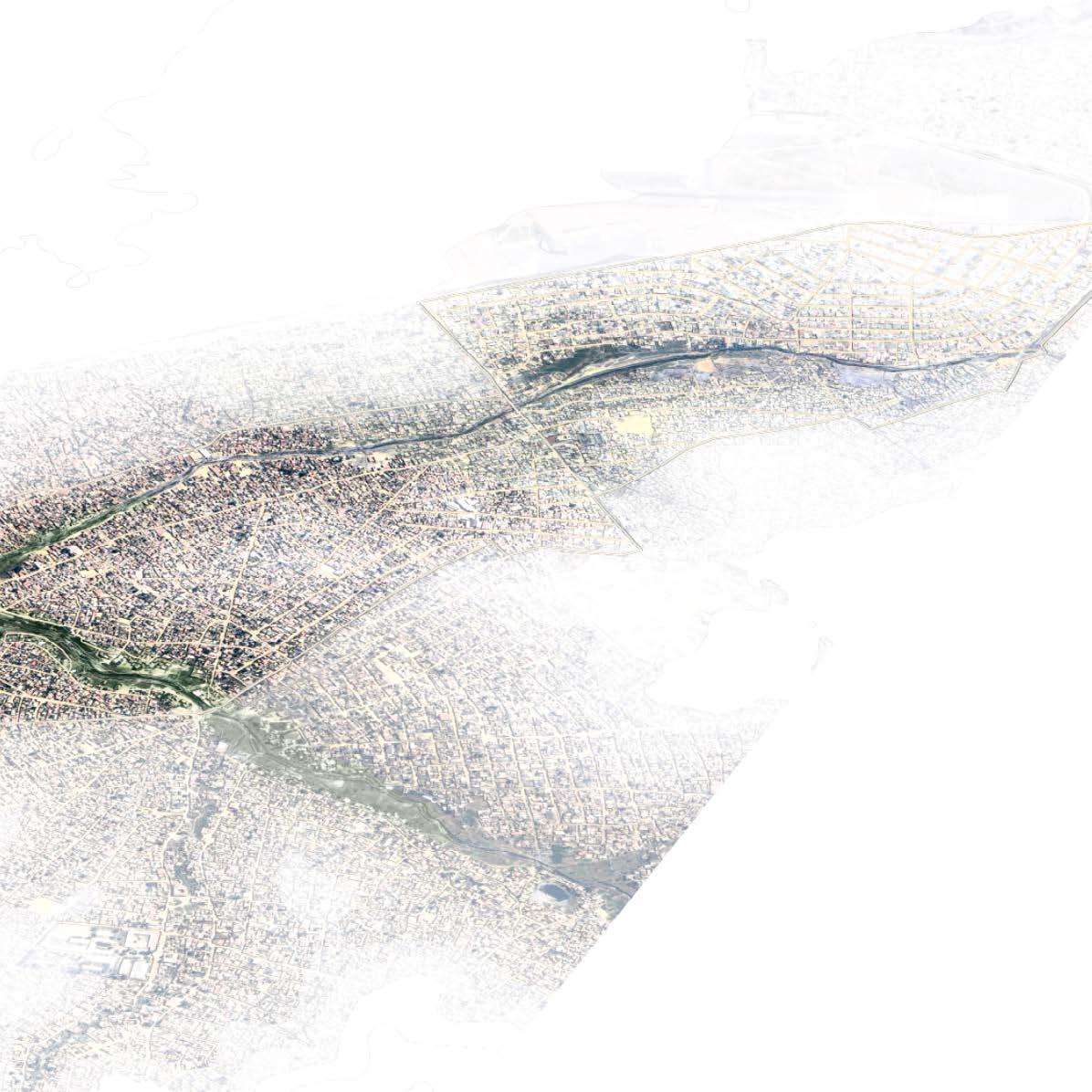

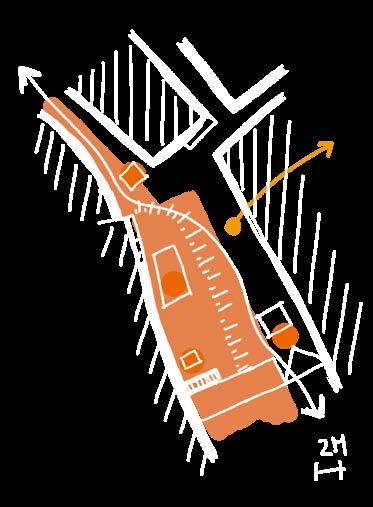

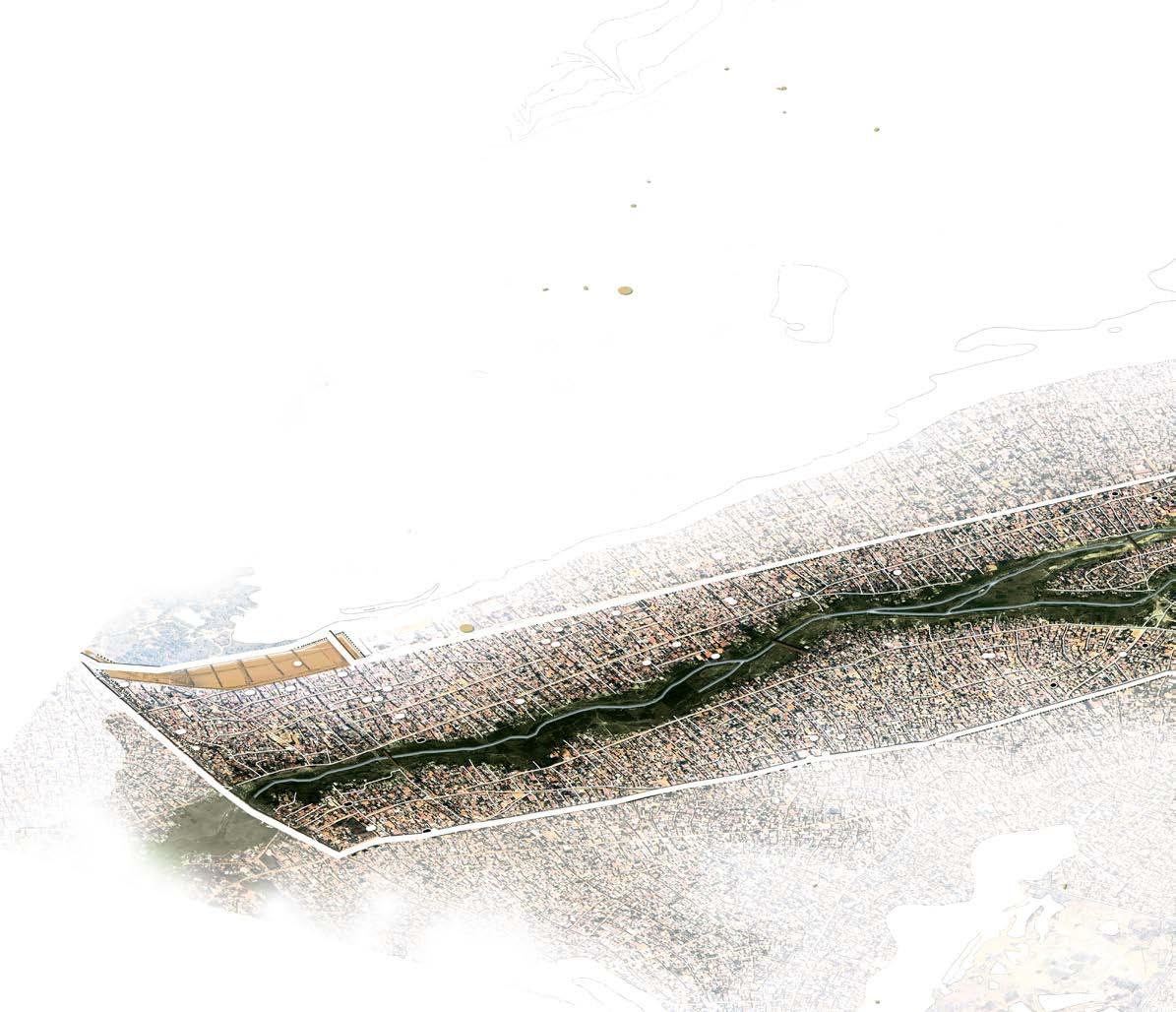

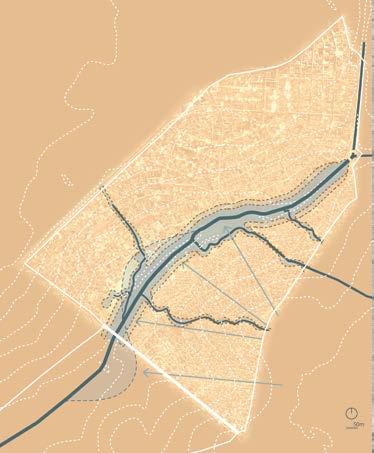

THE PROJECT AREA

THE AREA CHOSEN FOR THIS PROJECT FOLLOWS 5KM OF THE CAMBAMBA RIVER BEGINNING AT AN INFORMAL MARKET SQUARE AND ENDING AT THE CANTINTON MARKET.

THE MUSSEQUE

THE cantinton market

THE ZUNGUEIRA

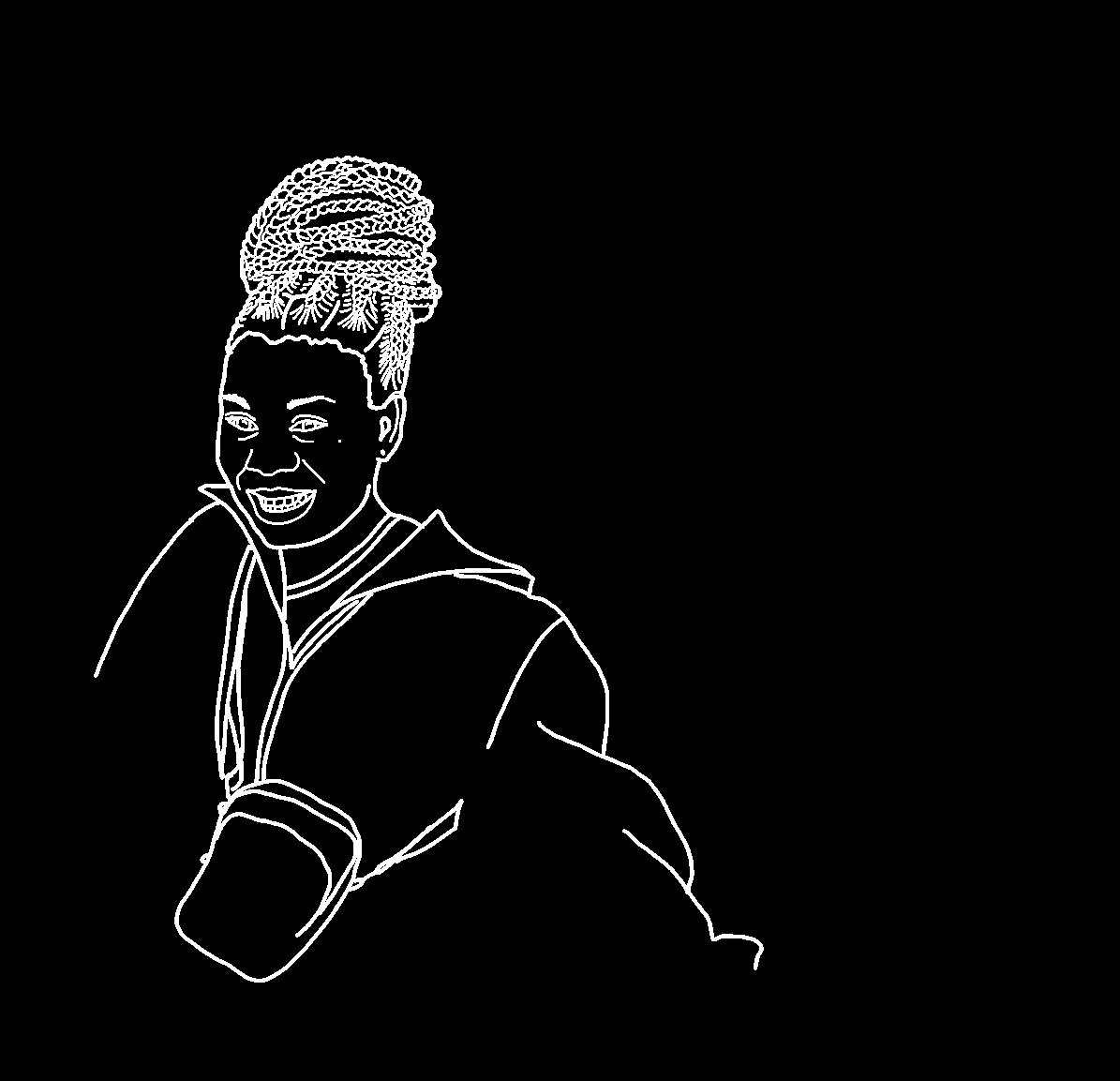

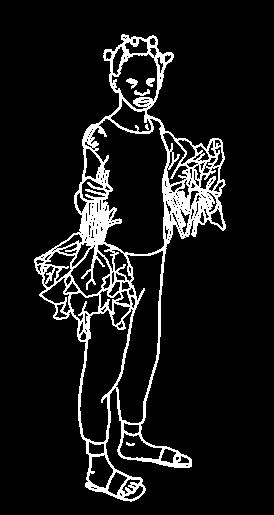

WHO IS A ZUNGUEIRA?

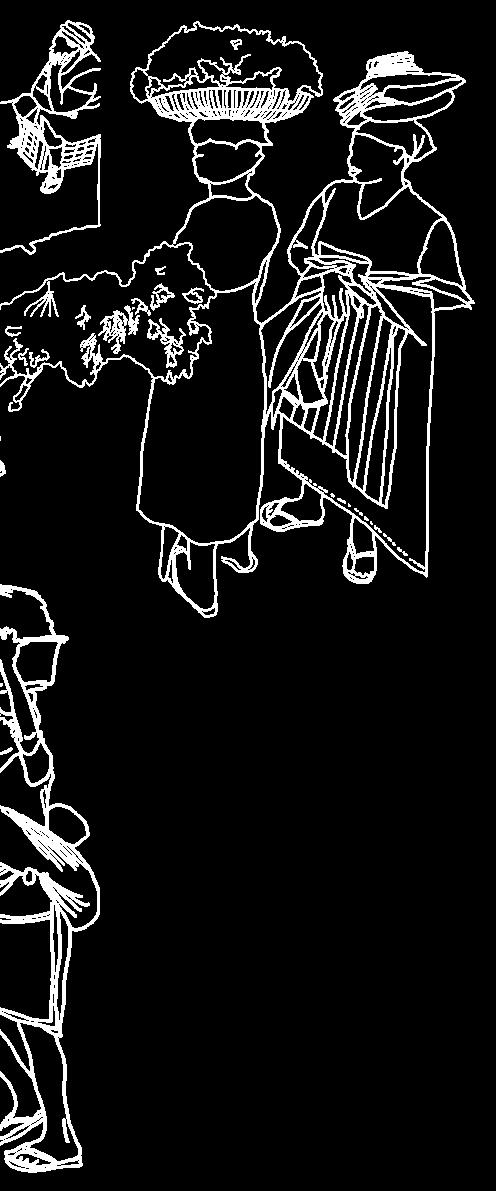

“Zungueira is the woman who walks the streets with a basket on her head and usually with a child on her back, wrapped in a cloth. The size and weight of the basket defy the laws of physics and human resistance. The women sell fish, fruit, books, newspapers, biscuits, in short everything that can be sold and carried in a basket. Many are sitting at the entrance to supermarkets, or in certain parts of the city.”

De Raeymaeker, J. (2012) À descoberta de Angola (Discovering Angola)

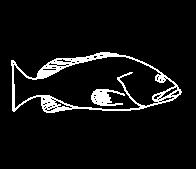

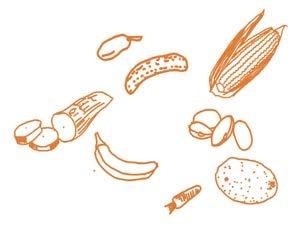

SUGAR CANE

FRUIT (PINNEAPLE, WATERMELON, ORANGE, BANANA, AVOCADO)

SOME OF THE THINGS THEY SELL

LEAFY GREENS (GIMBOA)

CASSAVE, SWEET POTATO & BEETROOT

HERBS (PARSLEY, CORIANDER) & lettuce

CLOTHING

MúCUA (BAOBAB TREE FRUIT)

FLOUR IN A BAG (CASSAVA, CORN)

TROPICAL forest CASSAVA, BANANA & PLANTAIN

transitional LOWLAND MAIZE, CASSAVA & BEANS

LUANDA MARKET GARDENING

COASTAL FISHING

savannah forest market oriented cassavA

maize & cassava

Central highlands MAIZE, BEANS, POTATO & VEGETABLES

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS AGROPASTORAL

SAVANNAH FOREST SUBSISTENCE CASSAVA

ZAMBEZe river area CASSAVA AND FISH

MID-EASTERN SAVANNAH FOREST AND CASSAVA

SOUTHERN CATTLE, MILLET & SORGHUM

map based on Angola Livelihood Zones, Fews Net (Famine Early Warning Systems Net)

CUCUMBER

BANANA

CASSAVA

WHERE DOES THE FOOD COME FROM?

ZUNGUE

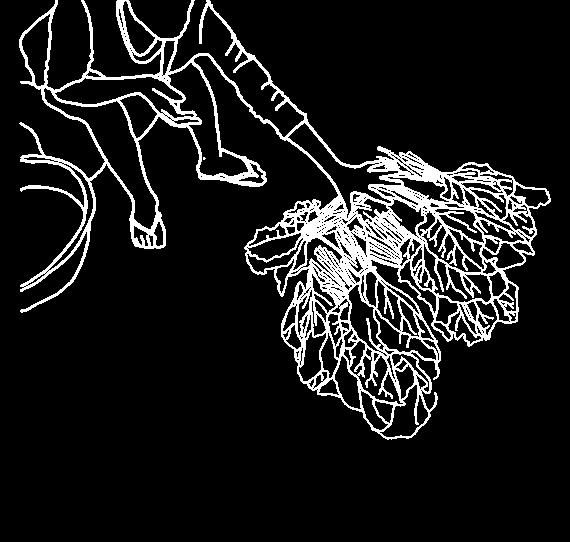

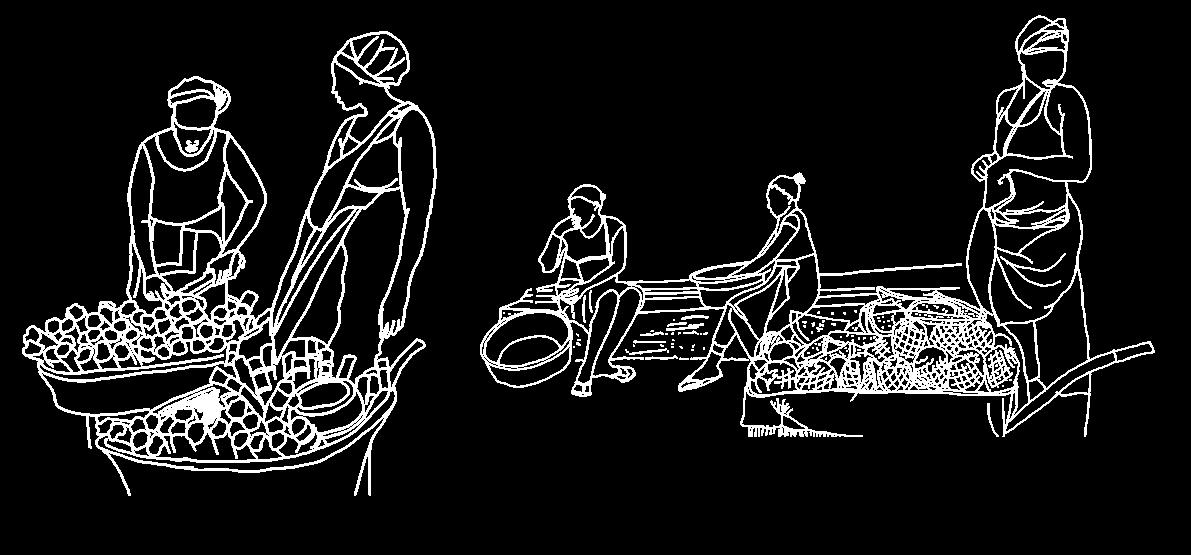

IRA THE TRABALHADOR CARRIES THE LARGER QUANTITIES OF FOOD

10 cabbages = 6000 kz tomatoes = 15.000 kz carrot/ cucumber tomatoes = 3000 kz

THE CANTINTON THE FORMAL

CANTINTON

THE STREETS THE INFORMAL MARKET

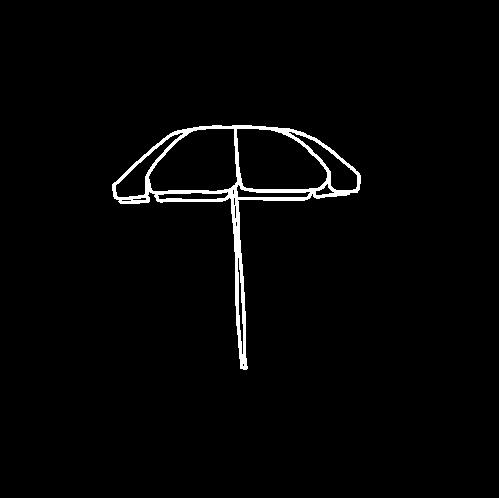

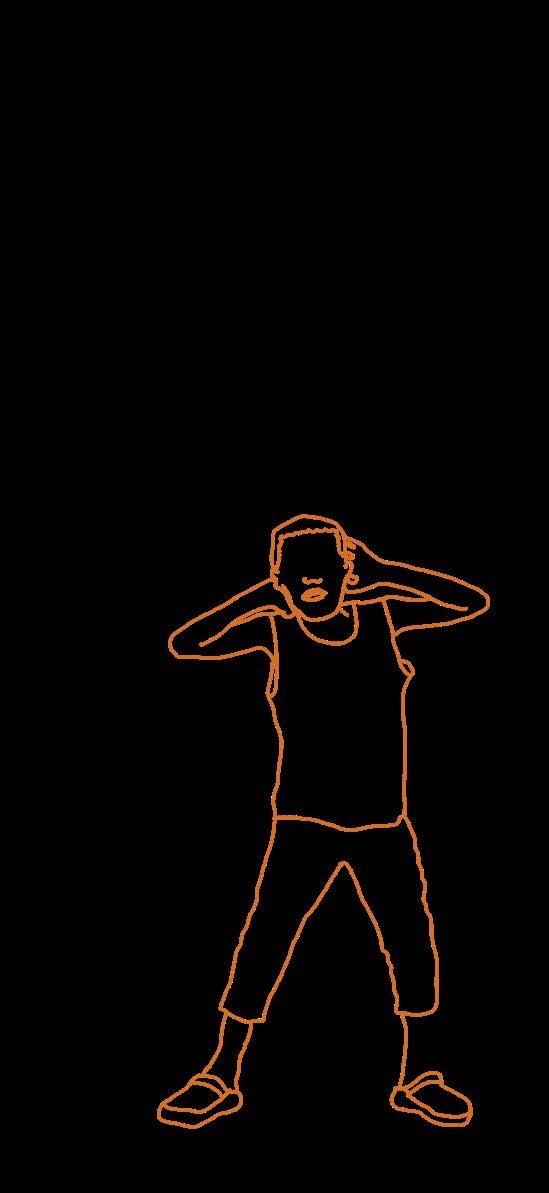

There are two main threats which a zungueira faces when selling on the street: weather conditions and the threatening presence of the fiscal.

The rainy season (from October to May) makes selling on the street an even more challenging livelihood. Zungueiras are exposed to the sun for several hours at a time. To protect themselves and their merchandise they use umbrellas or sit under one of the few trees in the streets.

After May, the cacimbo season starts and temperatures drop down to between 24º and 17 ºc. As a result, fruit and vegetables stay fresh for a few more days than usual.

However, zungueiras still must work for their living on windy and dusty streets.

While seasons come and go, the fiscal is permanently making sure no rules are broken. This means that zungueiras must constantly remain alert because being caught might either mean losing their source of income or having to pay a fine that is almost as high as their daily earnings.

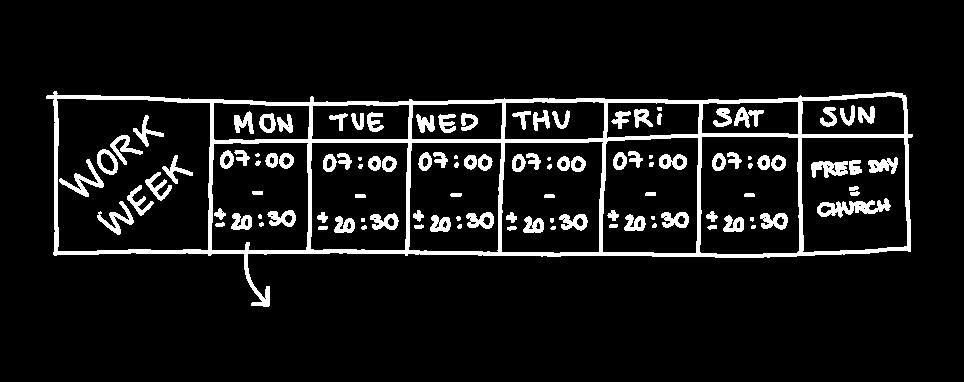

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF ZUNGUEIRA

XARÁ

1. buy food at the Cantinton

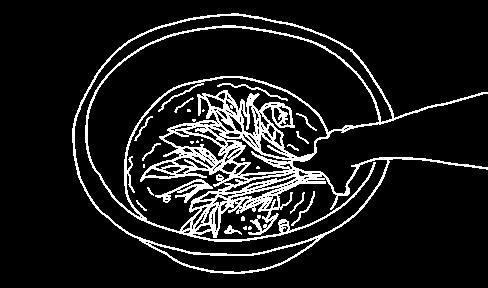

2. wash it WITH WATER FROM A HOUSEHOLD IN THE MUSSEQUE

3. sell it ON THE STREET

A BRIEF STORY OF XARA

My xará and me share the same name and age but our lives could not be more different. A day in her life is hard and always uncertain, yet she doesn’t let life defeat her. Four months ago, her father got severely ill during work in another province. Her mother, who is a fish zungueira, had to leave to take care of her husband, leaving her five children with 20.000 kz (20 euro).

Being the eldest, my xará was responsible for her siblings and for how this money should be spent. Since she did not know when her parents would come back home and how long the money would last to feed her siblings, she decided to use part of that money to buy food at the Cantinton market and sell it herself. Unfortunately, her father passed away after a few weeks. Now, just like her mother, she works long days as zungueira to support her family, having little time and energy to continue the studies that she had started to become a nurse.

RAMA (POTATO BRANCH) = 100 kz

TOMATE (roma tomatoes) = 4 FOR 200 KZ

BERINGELA (eggplant) =

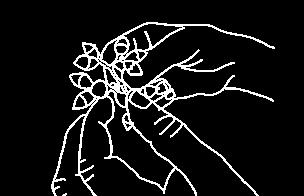

After months of being a zungueira, my xará already knows the zungueiras of this area. They welcomed her warmly and there is no competition amongst them. Instead, they help each other by trading vegetables or other products with one another. For example, this zungueira came to drop by some big onions and ‘gel cobra’. A small bit of this gel costs 100 kz and is used for making sleek hairstyles. The onions were sold out in no time.

onions

gelatinous FRUIT FOR ‘gel cobra’

WHO DOES SHE SELL IT TOO?

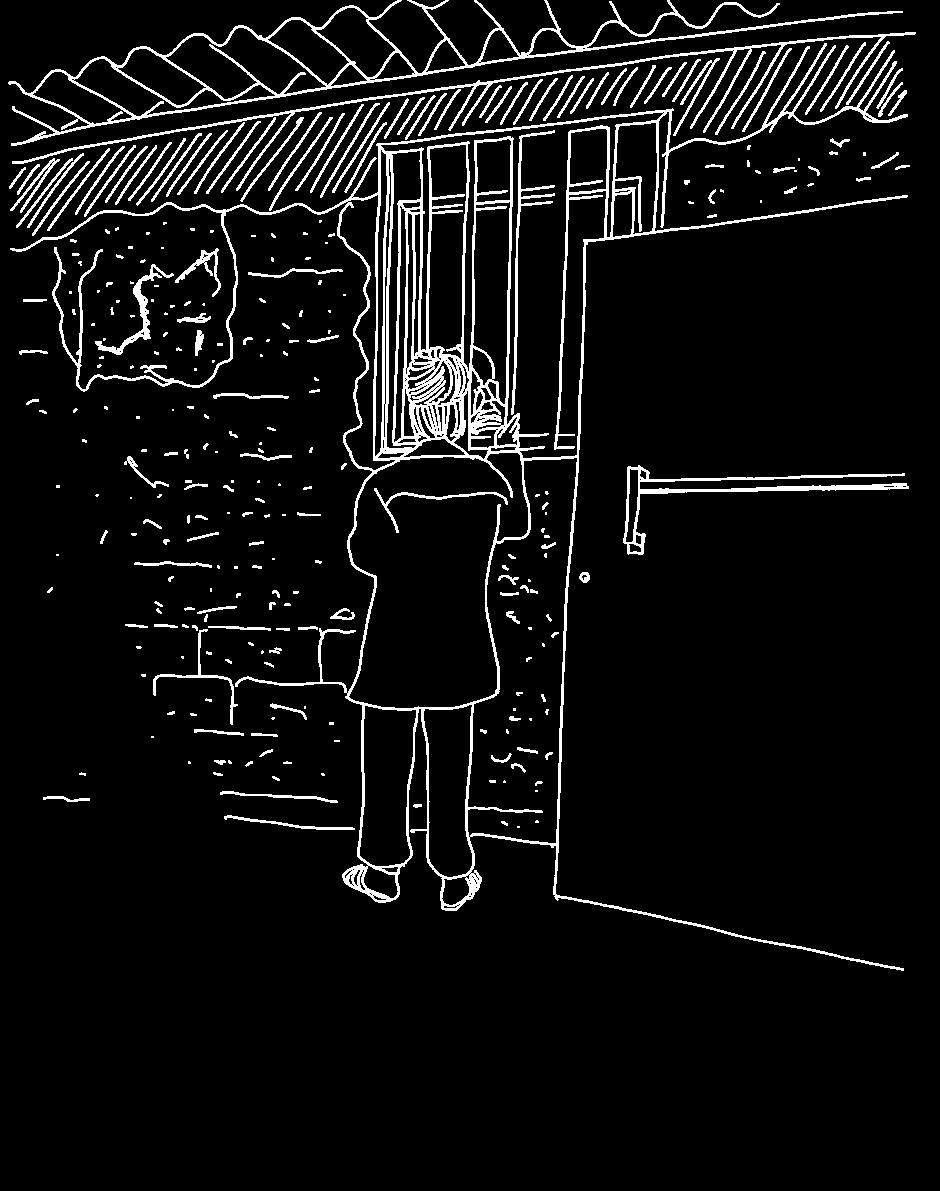

OF THE MUSSEQUE THAT PASS BY ... OR AT THEIR WINDOW

RESIDENTS

Selling fruit and vegetables in the neighbourhood has great advantages for her. Everybody can buy something on their way home to make lunch or dinner. Children also often pass by to buy a few ingredients that are missing for their parents to make a meal.

CHILD SELLING JEWELRY

SELLING COOKIES

ZUNGUEIRA SELLING HOT MEALs such as KIKUANGUA (CASSAVA FLOUR wrapped in banana leaves) & pincho (grilled meat)

ZUNGUEIRA

floorplan of the alley (MORNING)

MOTORCYCLE REPAIR

THE ALLEY WHERE XARA WORKS

zungueira

children sitting on concrete edge

floorplan of the alley (afternoon)

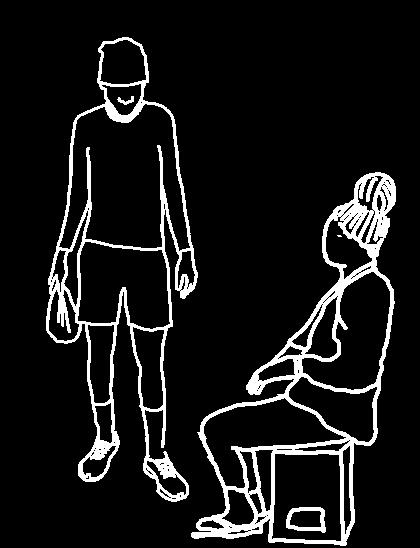

Some zungueiras sell on busy streets. There is more movement and therefore more chance of selling their products to a pedestrian or a driver. Others, like my xará, prefer to do so in an alley at the entrance of the musseque. Comparing to the other zungueiras they have less consumers, but they are less likely to be caught by a fiscal. This alley may be small, but it is full of life. While someone repairs a motorcycle, children gather and play on the only sunlit corner left at the end of the day. Beyond fruit and vegetables, a variety of other foods are sold here. There is even a girl selling jewellery.

main route zungueira spot

other uses of the public space shadow

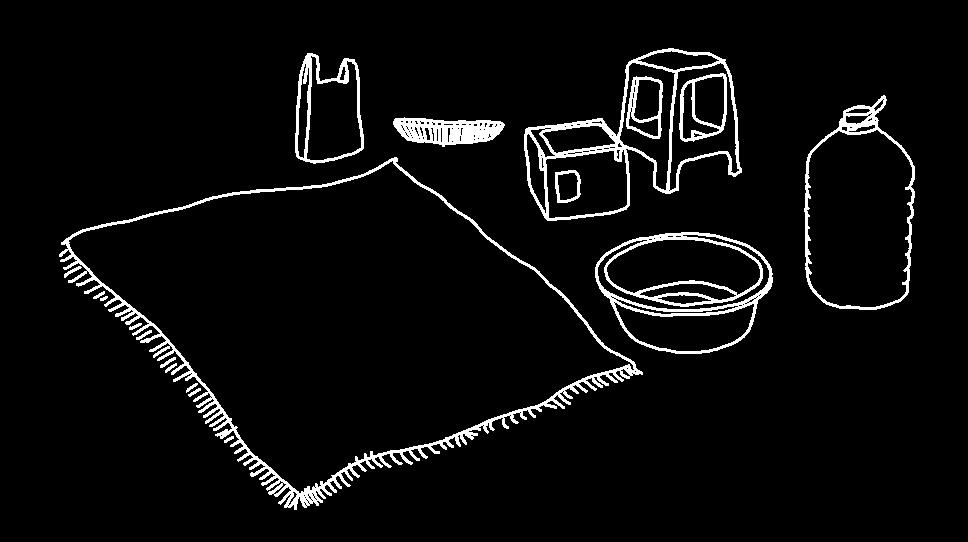

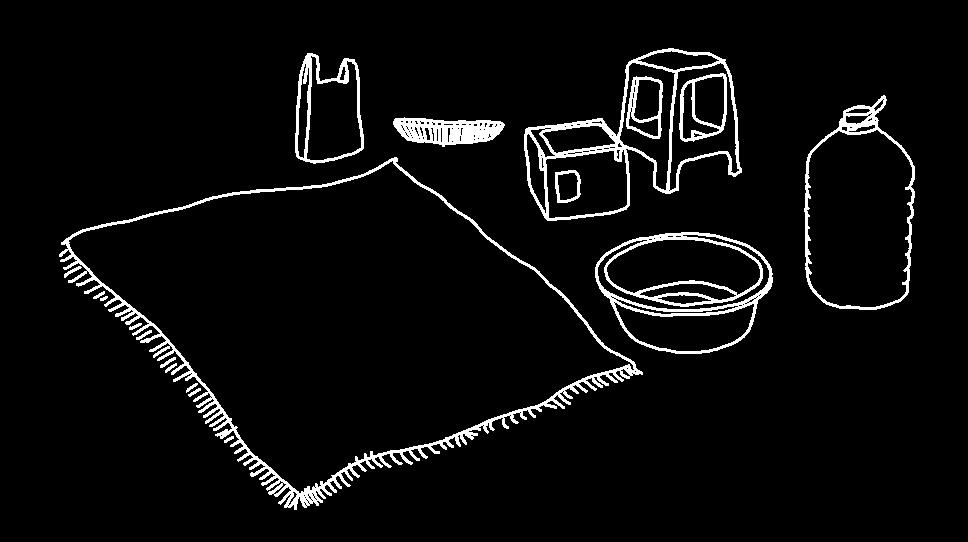

UMBRELLA

BIG OPEN PLASTIC BAG TO PUT FOOD ON

plastic bagS strainer

CRATE OR STOLL TO SIT

BOTTLE OR BARREL WITH WATER TO WASH FRUIT & VEGETABLES

big plastic bowl

WHAT SHE NEEDS WHERE DOES SHE STORE HER FOOD?

There are a few tools that she needs not only for herself but to store, wash and display her food. She does not live in this area so the Food is stored in the processo and she taps water from a household in the neighbourhood. However, none of these things are free.“EVERYTHING CAN BE BOUGHT HERE” SHE SAYS.

HOW SHE SPENDS HER TIME THERE

“theSE BRANCHES have to be beautiful and presentable otherwise the customer won’t take them”

WASHING VEGETABLES

EATING WHILE SITTING & WAITING

SORTING FOOD

DOING HAIRSTYLES

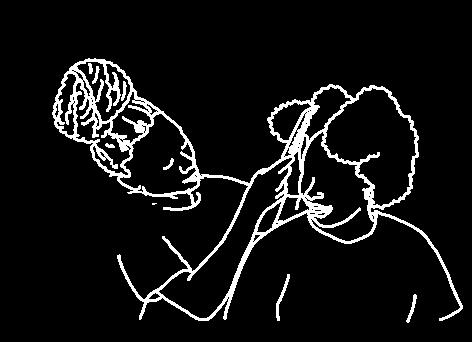

INTERACTING WITH PEOPLE FROM THE NEIGHBORHOOD

UMBRELLA

BIG OPEN PLASTIC BAG TO PUT FOOD ON

plastic bagS strainer

CRATE OR STOLL TO SIT

BOTTLE OR BARREL WITH WATER TO WASH FRUIT & VEGETABLES

big plastic bowl

WHAT DOES SHE NEED TO WORK & WHERE DOES SHE STORE HER FOOD?

There are a few essential tools that she needs not only for herself but to store, wash and display her food. Since she does not live in this area, the food is stored in the processo and she fetcheswater from a household in the neighbourhood. However, none of these things are free. “Everything can be bought here” she says.

“HOW WOULD YOUR IDEAL WORKING PLACE BE LIKE?”

‘‘I would like it to be inside the market. People buy less there, and the conditions are not even that better than on the street but at least there I don’t have to watch out for the fiscal. They also close the market so my things could be safely stored there. Another thing I would like is to live close to my working place. Now i must take the candongueiro to come here and to go home which also costs money.’’

THE REQUIREMENTS FOR A ZUNGUEIRA

- access to clean water and storage facilities

- a place close to her house

- trees for shade and for hanging things

- protection from the wind

- a place far from stagnant water or flooding-prone areas

- a sturdy object to sit on

- Sufficient space to display her merchandise (± 1m2 per zungueira)

- a place that is stimulating to counteract many hours of boredom and little activity

THE CHILDREN CHAPTER II

THE CHILDREN OF THE MUSSEQUE

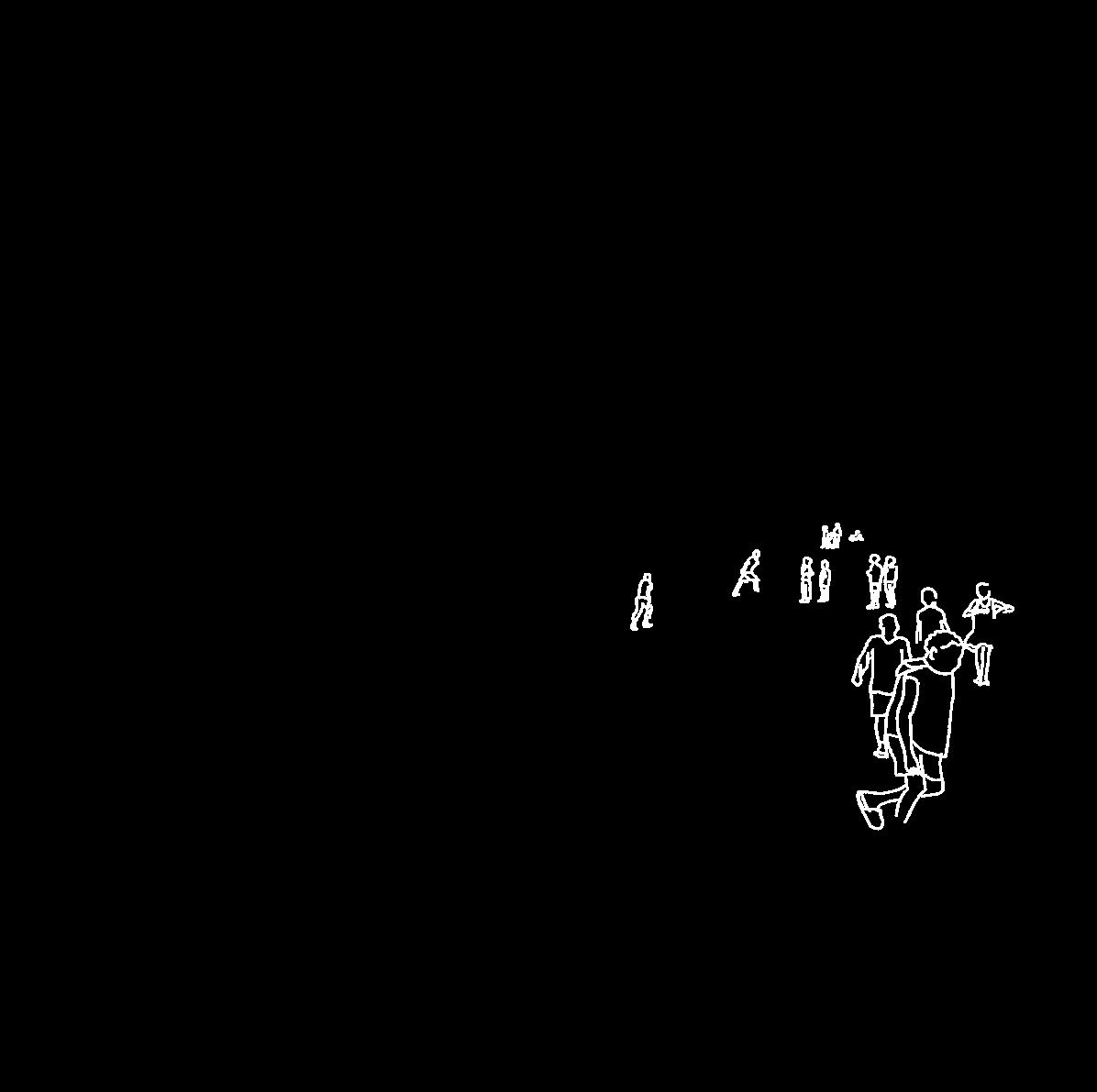

Public spaces are of great importance to the wellbeing of every citizen of Luanda, but their fragility disproportionately affects mainly two groups: zungueiras and children.

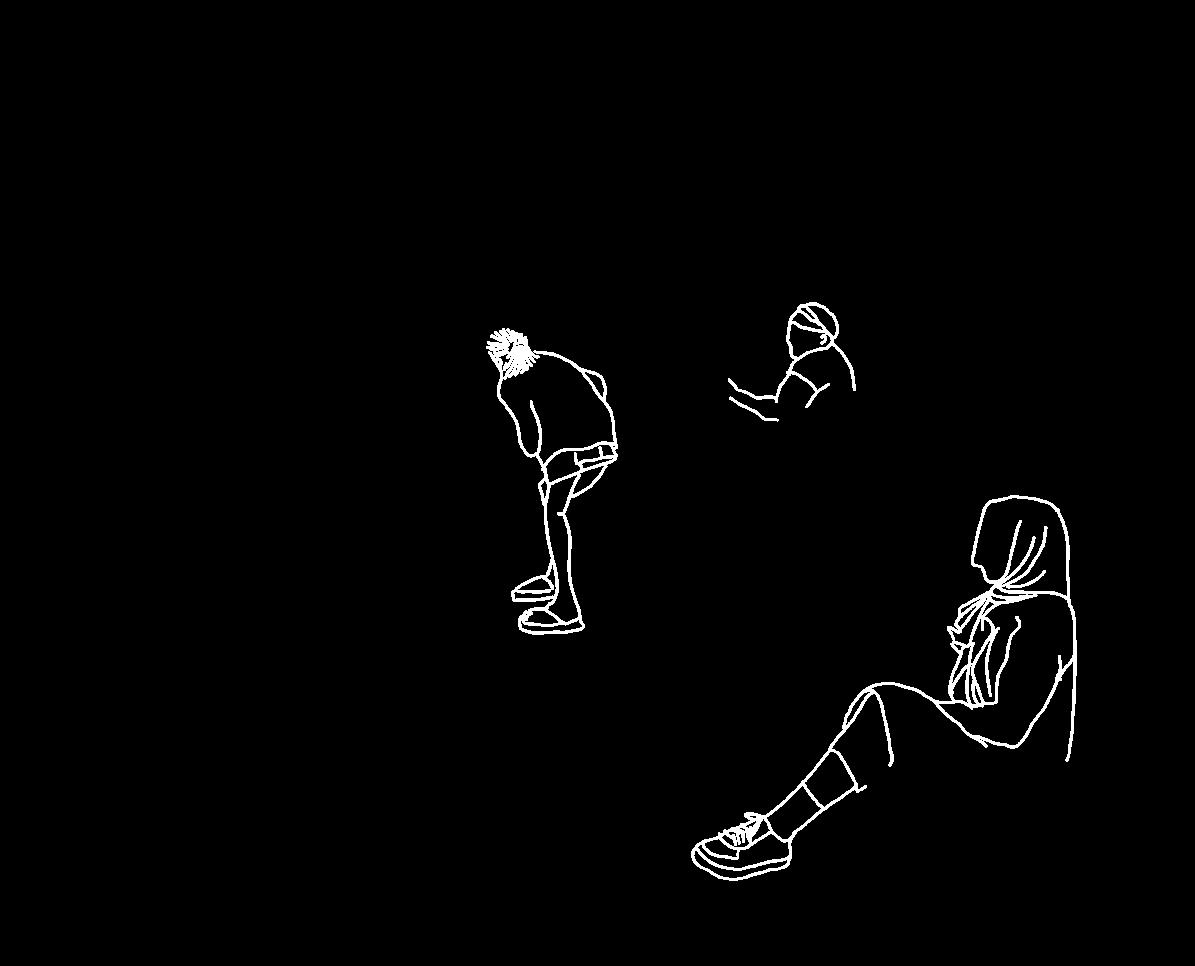

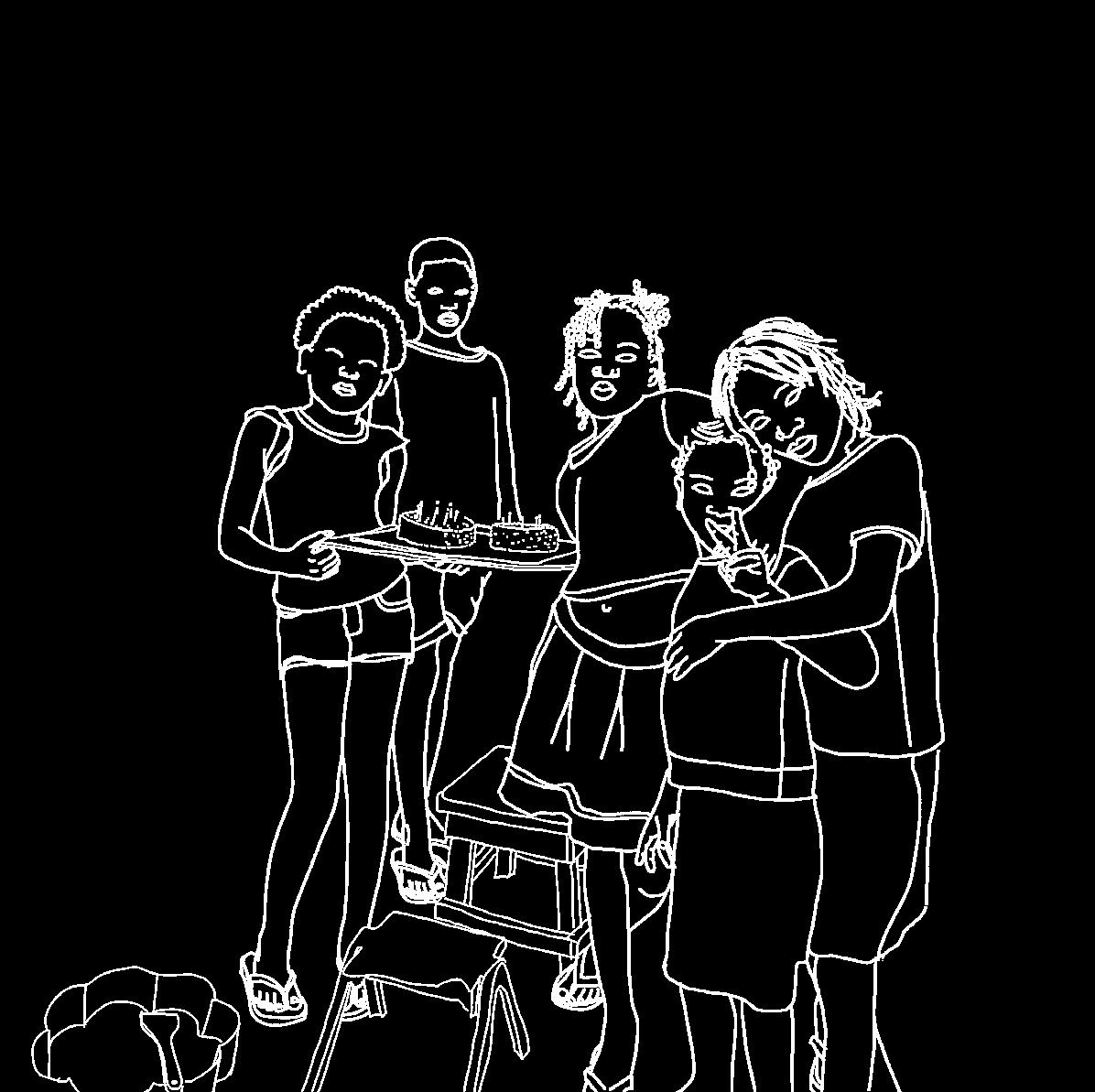

Notably, there are two national holidays to honor them: the 1st of May is the day that symbolizes the historical relevance of the struggles and achievements of the Angolan working class. On the 1st of June, children are celebrated. They constitute nearly 40% of Angola’s population and represent the future of the country. Many children are denied access to the basic conditions essential for their development - such as education, healthcare, water, and nutritious food – to say nothing of a safe space to play outside. Playing outside takes many forms and children are always very creative. Everything can become a toy and every place a new imaginative world. On a small corner I encounter a wonderful moment. A group of five children is sitting around a small table singing “happy birthday”. On the table there are two cakes with a few matches on top as if they were candles. I come closer, introduce myself and ask whose birthday they are celebrating. One of the girls, not shy at all, tells me they’re celebrating the birthday of two of them. Simply using a cake tin, sand and water they were able to make a beautiful cake which they are very proud of.

In one of the corners where the sun is still shining, two children play with each other. It doesn’t take long until one of them gets clumsy and bumps against a bucket of flour. Half of it falls on the ground and the child is quickly reprimanded with a slap in the face from the zungueira.

HOW THEY SPEND THEIR TIME

The youngest generation of the musseque is insightful and very autonomous. One would expect this chapter to be about children playing when not in school. Unfortunately, some of them do not go to school, instead they can be found on the market either selling food, working as a trabalhador, fighting over who gets to clean shoes the fastest or doing groceries for their family. Even the youngest ones are brought up in the market, carried on their mother’s backs.

WHERE DO THEY SPEND THEIR TIME?

VAST OPEN SPACES OF THE MUSSEQUES

Angolans know how to celebrate life on any day of the week but specially on Fridays. Public space may bring people together, but it is sport that really unites people, whether they live in a musseque or a compound, whether they have spent their lives studying or working. The vast open spaces offer a world of imagination for children to play in. A wall becomes an object to jump on and the river shores turn into an adventurous climbing route.

THE CAMBAMBA CHAPTER III THE CAMBAMBA

Luanda, 25th of july 2024

Today was overwhelming. I start the day by going to UTGSL. I’m finally going to check out the river area I want to make my design for. This cannot be done alone due to security reasons so the department director of UTGSL and a co-worker were so kind me to accompany me through this walk along a part of the Cambamba.

We start by visiting the first part, the Senado da Camara channel, a 7m deep concrete ditch where garbage flows along with the water. Parallel to that channel an underground channel leads wastewater to the sea.

The Senado da Camara channel and the Cazenga Cariango channels come together in a gigantic informal market. The TRIBUTARY of the cambamba is one big river of plastic. I have never seen so much garbage in one place, specially not a river. Everything happens around the river area but this ecosystem is broken. Flies, mosquitos, pigs, dogs, goats all coexist here with children that play in and with garbage. The reality many people told me about has become real. How does something as natural and as vital as a river become the biggest threat for the health and safety of the sorrounding inhabitants?

The waste thrown in the river blocks the water flow and water finds its way up until houses built informally on the river banks. Some reinforce the banks underneath their houses with rocks and concrete and some cannot anticipate extreme weather events and end up losing their home to the river. Here and there crops are grown and irrigated with the contaminated water from the river. Garbage is either thrown in the river or burnt on its banks. Alleys have become too small for trucks to come and clean all the waste.

Tavira shows me the beginning of a project for a parallel channel to collect wastewater. Since houses have to be demolished for this and there are no places available yet to reallocate people, this project is taking longer then expected which means that in the meantime new houses have already been built in the areas that were made vacant. This is how it goes in informal settlement areas.

Reality in this neighborhood is cruel and sad. People look at me like I’m an outsider, which I am. Back home, in Amsterdam, river areas are places people are actually proud of and that landscape architects really fight for. Also, if a garbage bin is full I have the privilege of walking to the next one knowing that all bins will be emptied soon. Could this also be the future of this neighborhood? People protect what they care about so starting from the

river and its significance is the first step towards this future.

After a few hours we walk through the main street of the neighborhood, which is now dry but during rain season is completely flooded due to the high ground water levels.

Later on I take the candongueiro home and take the time to observe people’s behavior, and really listen. The cobrador shouting the destination, the traffic, people getting in and out of the vehicle and the driver stopping along the way to buy oranges from a zungueira. Life is so different here and it takes me the rest of the evening to let that sink in.

CHILDREN CARRYING BOTTLES FILLED WITH RIVER WATER street vendors

The informal USE of the banks of the cambamba

Abandoned house with remaining waste water pipe

waste water DISCHARGE DIRECTLY INTO THE RIVER

waste water collector

the flooding of the cambamba is caused by obstructions in the river SUCH AS GARBAGE AND HOUSES BUILT ON THE BANKS

reinforcement of the banks with concrete

LOCAL Gardening in the musseque

ROOM TO FIND

PEACE OF MIND IN THE CHAOS

water finding its way through buildings

High DOOR THRESHOLD TO PREVENT WATER FROM COMING IN

small AND UNSAFE paths

Surface runoff shapes the landscape around the cambamba

FRUIT TREES PLANTED BY LOCALS ALONG THE BANKS

BANANA

small scale Urban agriculture BEHIND THE WALLS OF THE CHANNEL

TO A CHANNEL

EVEN IN THE NEW CHANNEL AREAS GARBAGE STARTS TO PILE UP. THESE AREAS ARE free from houses and therefore easier to reach. waste can therefore be collected and removed easily

SEPARATING RAINWATER & WASTE WATER

The macrodrainage pipes along the CHANNEL lead the wastewater provenient from the neighbourhood to the wastewater treatment plant

Yet in some places where cattle is held, animals are drinking contaminated water

THE SORROUNDING NEIGHBOURHOOD THE STREETS

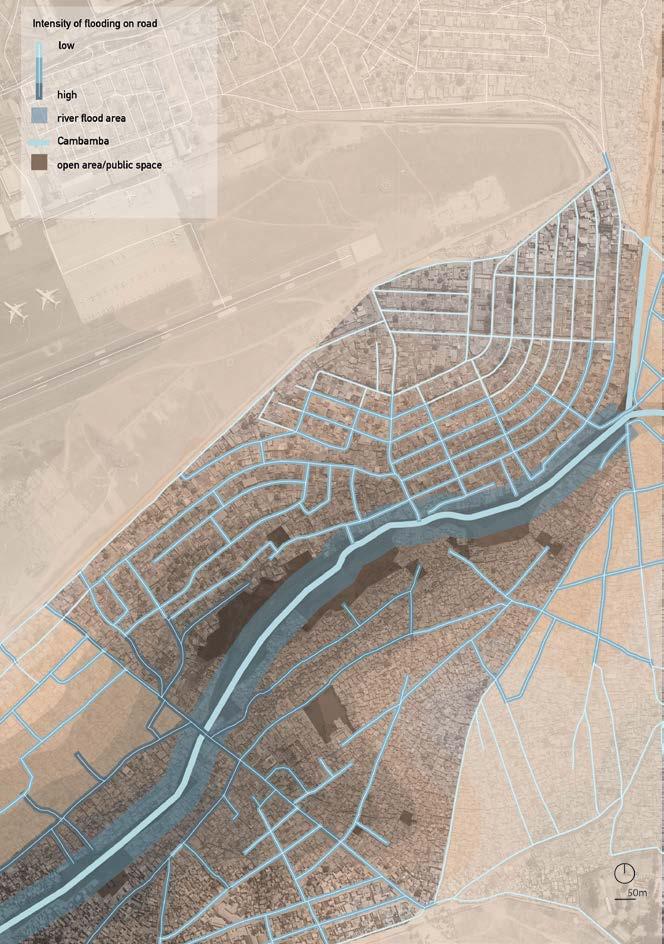

On top of floods caused by TWO MAIN obstacles (INFORMAL HOUSING AND TRASH) the groundwater levels also cause flooding in the neighbourhoods.

THE SORROUNDING NEIGHBOURHOOD THE ALLEYS

MAIN SOCIAL ISSUES IN THE SORROUNDING NEIGHBOURHOOD

- insecurity - unemployment - poverty - illness - addictions - criminality - low education

- community wanting to help in construction work

from left to right: IR. Henrique tavira (Director of UTGSL (the General Technical Unit for Sanitation in Luanda) AND THREE RESIDENTS OF THE MALANGINO NEIGHBOURHOOD

Luanda, march 2023

All neighborhoods of Luanda and the public spaces now face enormous challenges (sewage, garbage, traffic, etc.). Rodrigues tells me that the one we are in now, Morro Bento, is on a hill surrounded by ditches, but without sewage. A missed opportunity to save this area from heavy rains. When I asked if there are good parks or gardens, he laughed and said, “There are, but I wouldn’t call them parks. It’s just a bunch of plants or areas that haven’t been built yet. Some don’t even have benches. The Jardim do Amor (Garden of Love) is one of those places where people go to take wedding photos. It’s not pretty, but it is famous. This roundabout here was recently built and is beautifully planted in my opinion, but again: it’s not a park. The streets are so full of vendors, fruits, and vegetables of all kinds that one can’t even see the sidewalk. Between the busy streets, we enter a narrow ally that leads us to other small alleys. Everything has a beige and gray hue, but I see some plants outside people’s homes here and there. Adingui and his wife let me into their house and show me where they sleep and store their food. Even though it’s really dark, the temperature is higher than outside. The climatic adaptation of these houses is very low and they constantly face the consequences of heavy rains inside their home. Adingui and his wife gestured how the water enters and washes everything away and how intensely they have to throw the water away each time with buckets. Unfortunately, a few meters away, what is supposed to be a waterway to the sea is a garbage dump

site. Children also go there to find something they can play with and then climb back up. It is clear that among all the problems in public spaces, garbage and the lack of sewage systems are the biggest.

As a landscape architect, I see in addition to these problems a lack of vegetation that provides shade for the endless lines of people waiting for the official buses (unofficial buses stop wherever they can), and few adequate or hygienic places for street vendors, or places for the many children I see to play. And they are, in fact, the future generation of this country. My two half-sisters are also part of this generation and the only places they can play safely is inside their complex, at school, or in paid places, like theme parks. Therefore, not all children have access to a clean, safe, and pleasant environment to play. I wonder what Luanda will be like for them in a few years. Will the streets still be full of life, colors, and traffic noise? Will street vendors still be sitting on the streets or snaking between cars? And what food are they going to sell?

Total surface area

4.213.770 m2 (4km2)

CANTINTON MARKET

Flood area along the Cambamba

Flooded neighborhoods

Waste in and along the Cambamba

drone shot taken by UTGSL (the General Technical Unit for Sanitation in Luanda)

Berlage brug

De Hogesluis (Sarphatistraat)

1,5km

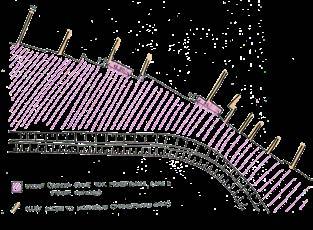

Replacing houses within the flood area

Managing rainwater flooding in the neighborhood

Creating a flood buffer for the Cambamba

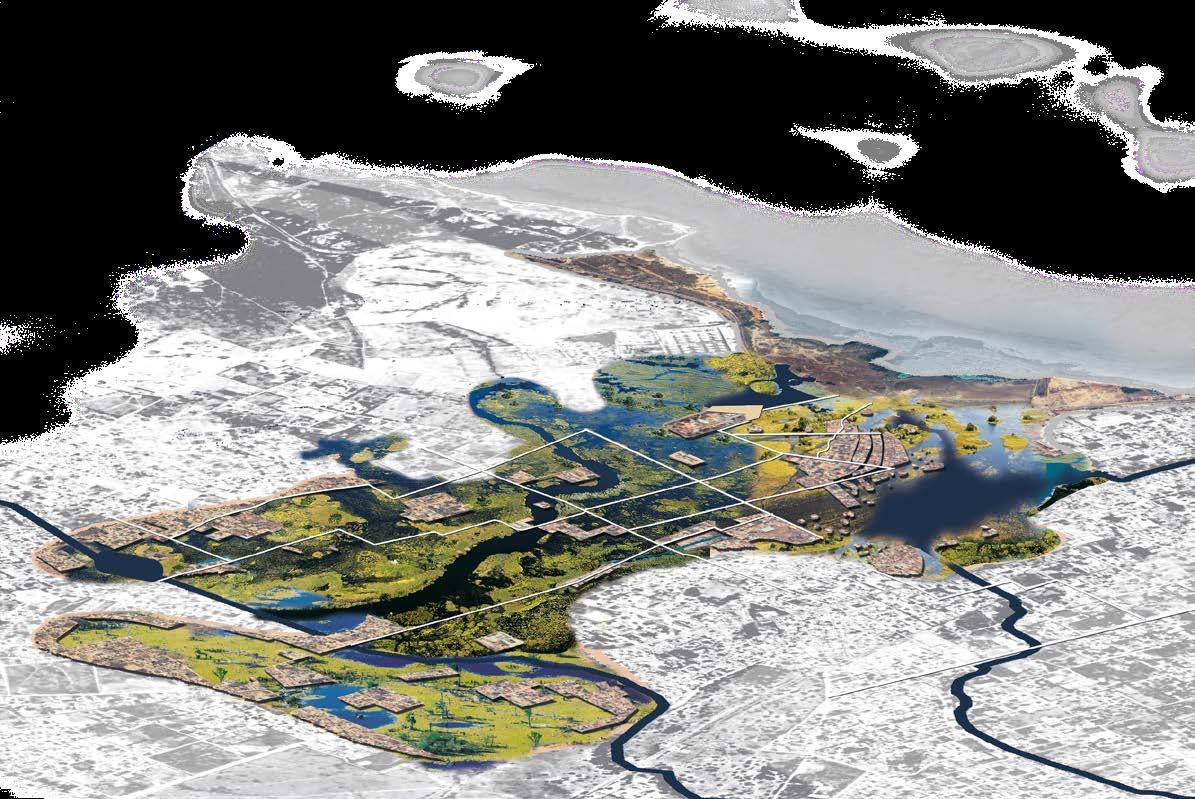

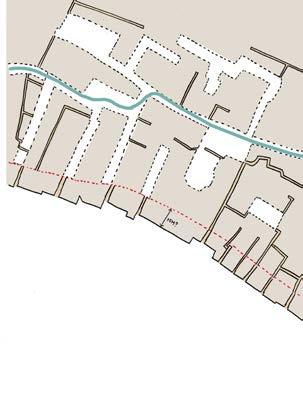

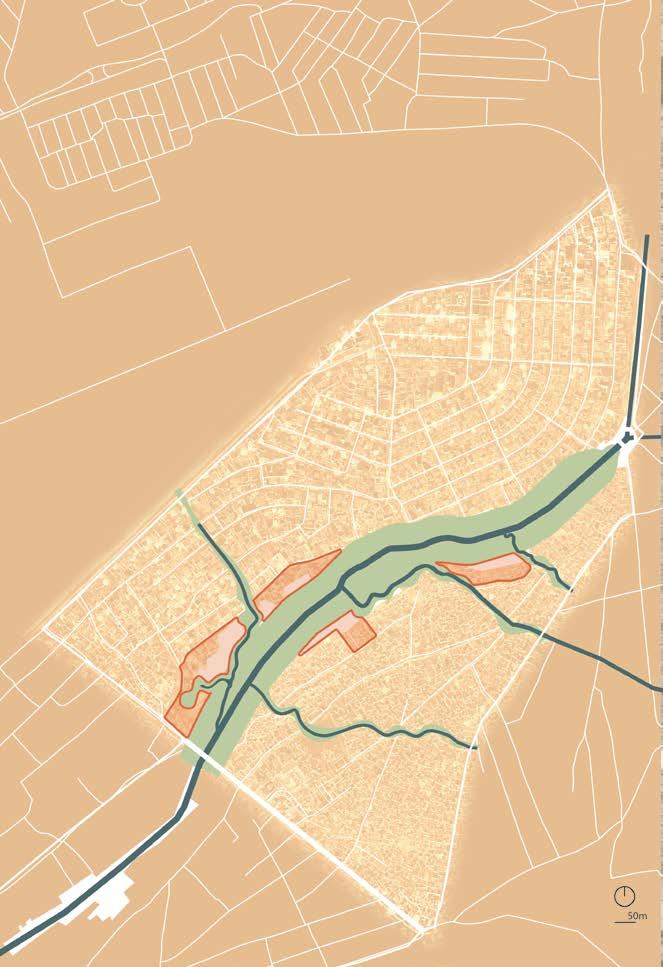

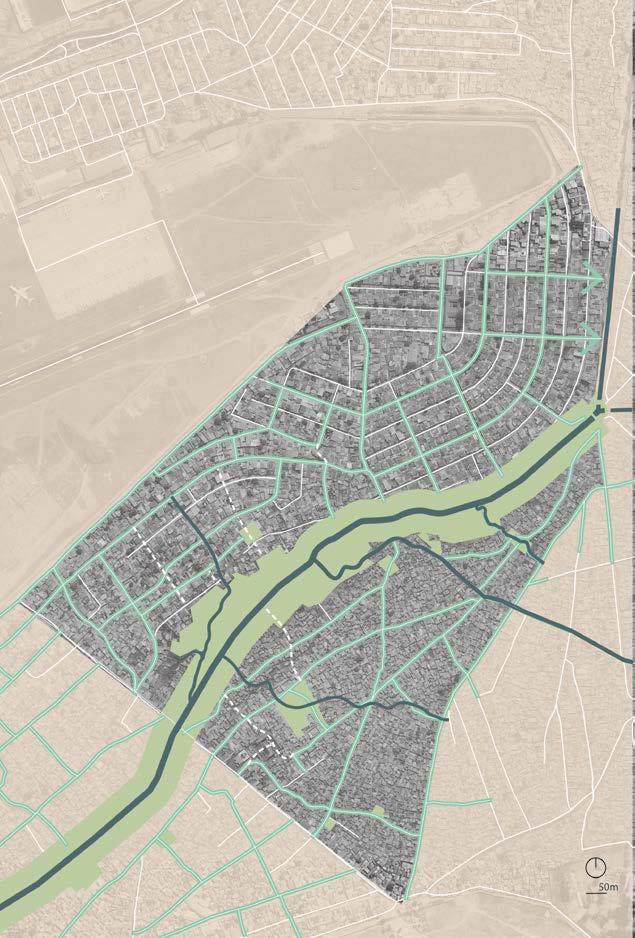

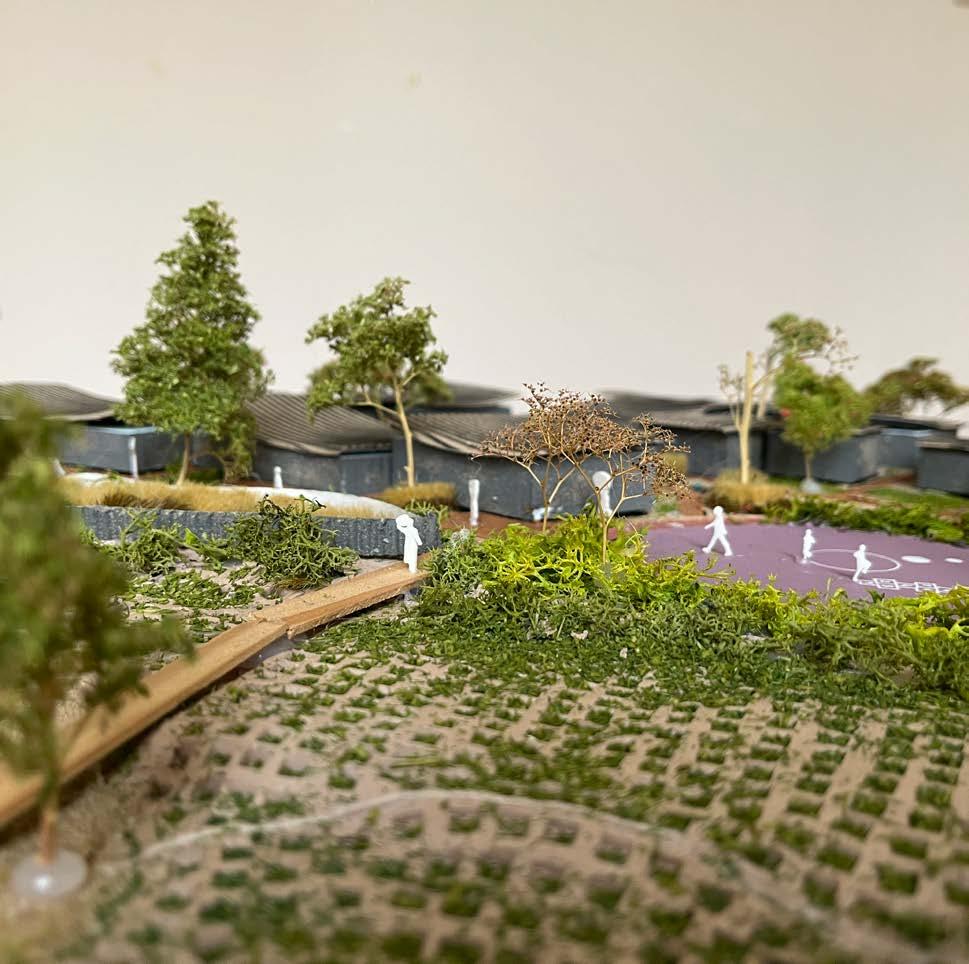

Having the opportunity to observe and most importantly tolearn from the people of the Cassequel was essential to understand this neighborhood and its needs. The project covers 1,5km of the Cambamba adjacent to the Malangino neighborhood and the Cassequel do Imbondeiro. Potentially it can become the catalyst for change along the entire Cambaba. Many problems of this area can be solved with spatial planning. However the solution begins with establishing a natural foundation that will foster the development of a climate-adapted landscape.

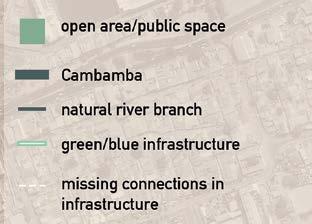

Restoring the landscape

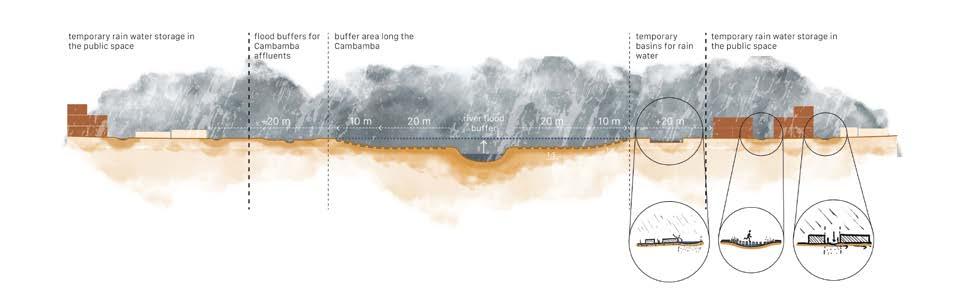

First, the river is restored to a natural state, giving it the space to expand within a buffer zone. In other words, houses and the most important infrastructure should be located outside a range of 100m from the Cambamba and its affluents.

A natural transition from river to neighborhood level is made through gentle slopes in the riparian zone. The soil that is excavated to do so will later be used to construct the new houses, replacing the demolished ones.

houses to be demolished abandoned house or ruin

open space

Cambamba

buffer area

extra buffer area

houses to be demolished

natural landscape

open space

Cambamba

Flood management within the neighborhood

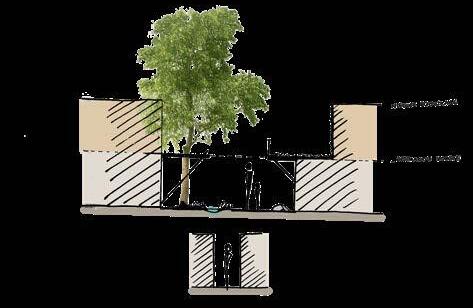

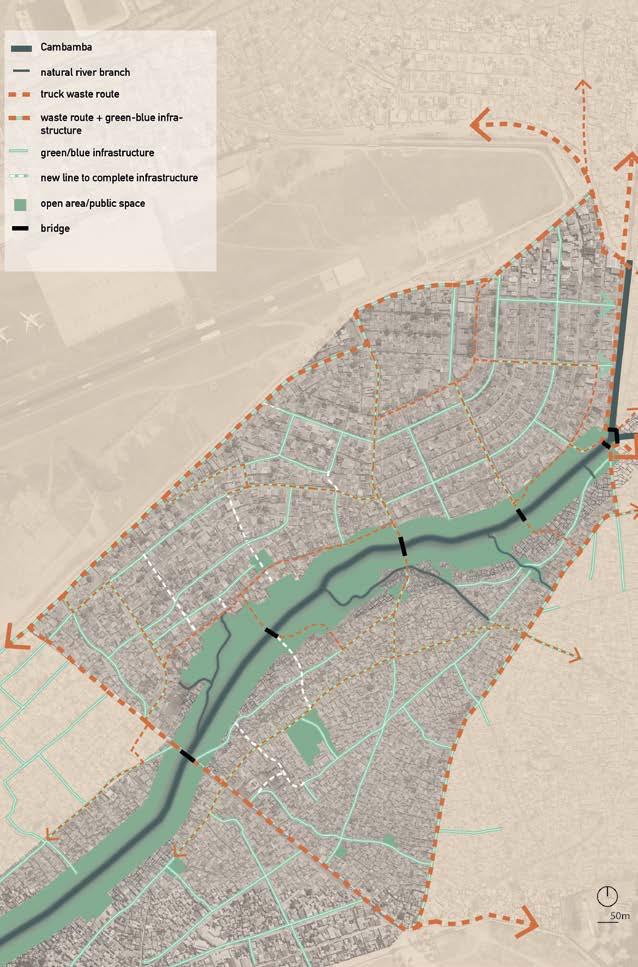

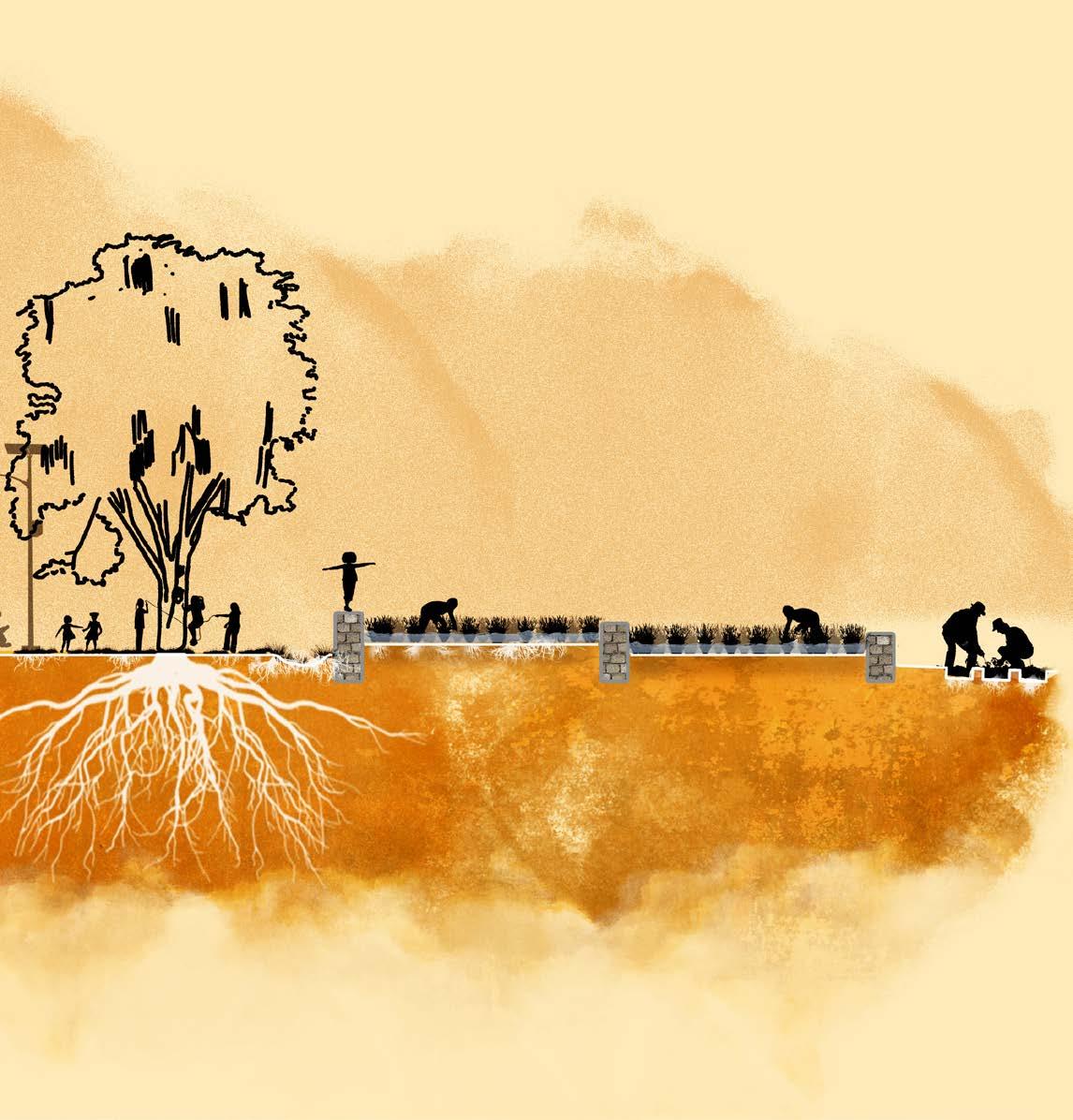

Besides the river, another major cause of water-related nuisance in the public spaces is the dry, compacted soil, which prevents water from infiltrating quickly.

Planting vegetation will help build-up the humus layer of the soil, thereby improving its capability to retain moisture during dry times.

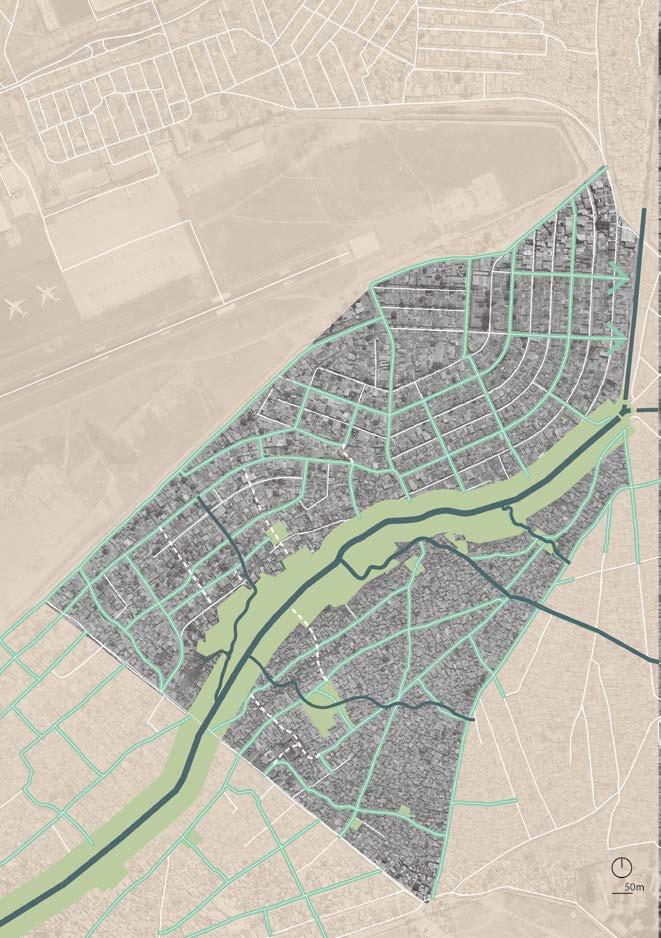

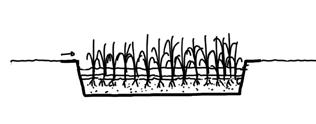

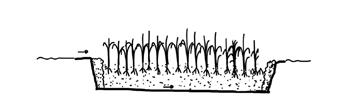

This is achieved through the creation of constructed wetlands in the streets and squares, giving these connections a climate-adaptive function in retaining and slowing down rainwater flow towards the river. At the same time, these connections bring people closer to the river landscape.

the topography

flooding on street level

new green-blue veins to improve water flow towards the river

Flow perpendicular to the river

Flow parallel to the river

contructed wetlands

Cambamba Cambamba

drone shot taken by UTGSL (the General Technical Unit for Sanitation in Luanda)

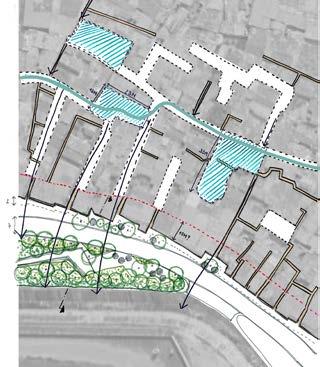

Waste management

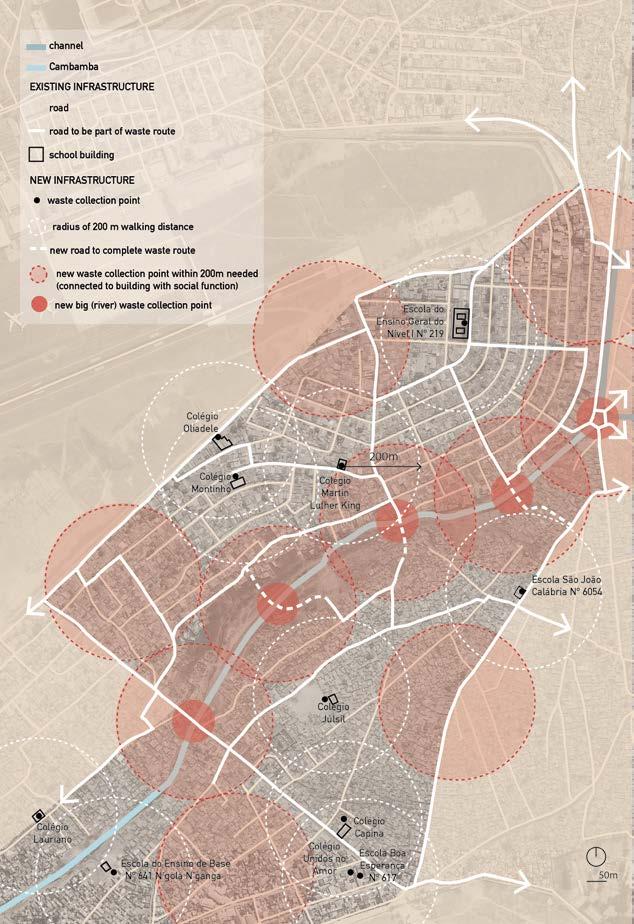

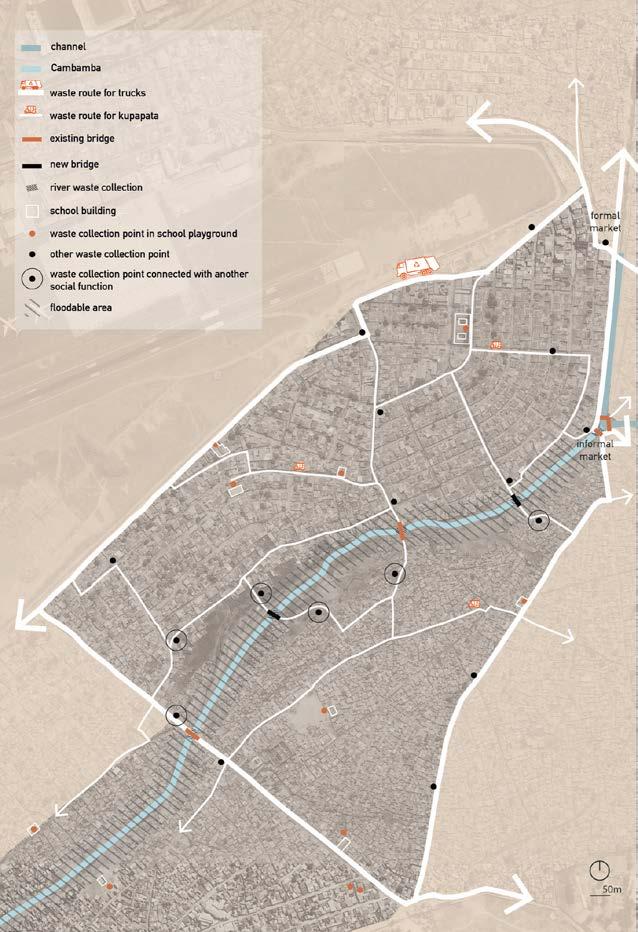

Currently, buildings on the shores and the dumping of waste in the river are the primary causes of severe flooding during the rainy season. Effective waste management starts with changing human habits and behavior. The greatest impact can be achieved by focusing on the youngest generations. Therefore, I propose that schools take on the central role, of becoming the main waste collection points of the neighborhood. However, some areas fall just outside an acceptable walking distance. To address this, additional waste collection points will be established, connected by routes along which kupapatas drive. Local waste collection is serviced by them. Then larger trucks pick up the waste. The river itself is provided with a waste barrier inspired by waste collection projects in Indonesia where similar river contamination is seen. using the existing infrastructure

filling in the gaps for a better system

Sungai Watch, a river waste barrier to stop the flow of plastic pollution from going into the ocean

garbage containers at waste collection point (to be spread throughout the neighborhood)

perscontainer for the bigger waste collection points

A local network for the river, the neighborhood and the community

A kupapata in Luanda

New path structure: A social and climate adaptive function

The new path structure enables the creation of a local network for transporting waste in and out of the neighborhood to garbage disposal sites. At the same time these paths also mimic the cooling function of the narrow alleys of the musseque but are enhanced with vegetation. Trees provide shade and riparian vegetation creates a rainwater buffer during the rainy season. New green veins, paths and bridges for slow traffic create new connections. Together, these connections bring the richness of the seasonal river landscape into the neighborhood and its inhabitants and viceversa.

VIII KIKANZU CAMBAMBA AT LAST

Scale

THE DESIGN

river

existing trees

new trees

school building

new market

informal open space

crop fields

running track (3 km)

waste route for trucks

waste route for kupapata

green blue street

green blue street + waste route (kupapata)

waste collection point

existing houses

new housing buildings

other services

bank vegetation

recreational green processos

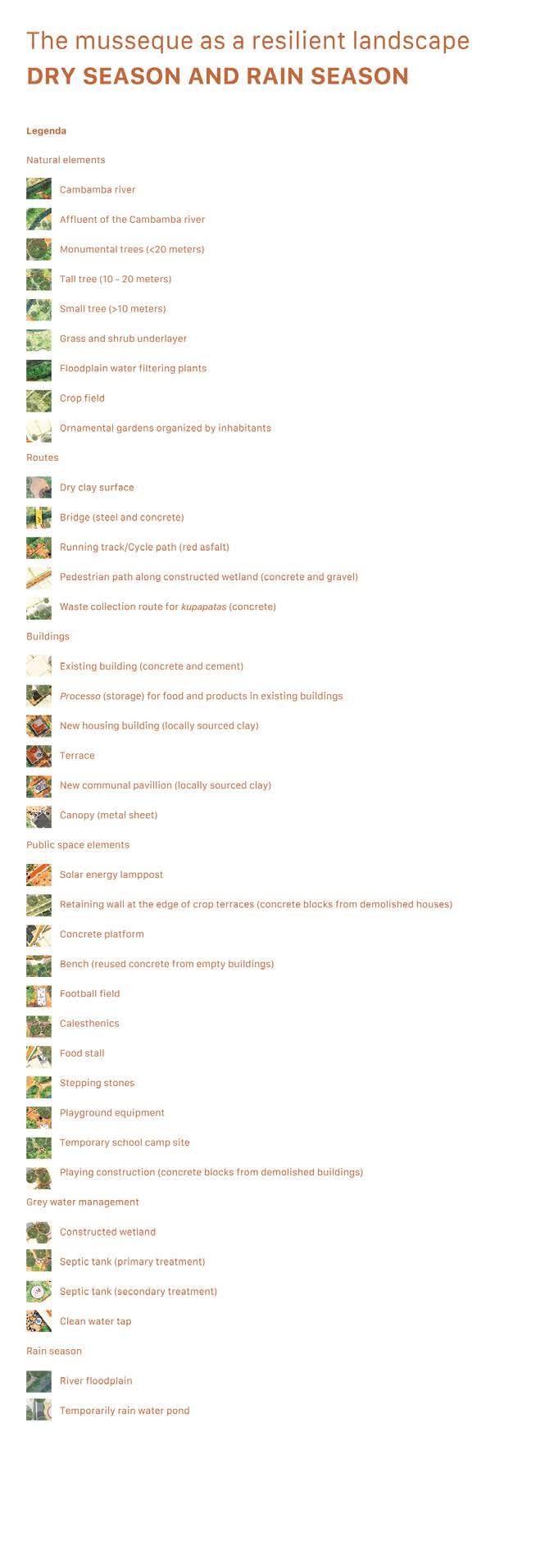

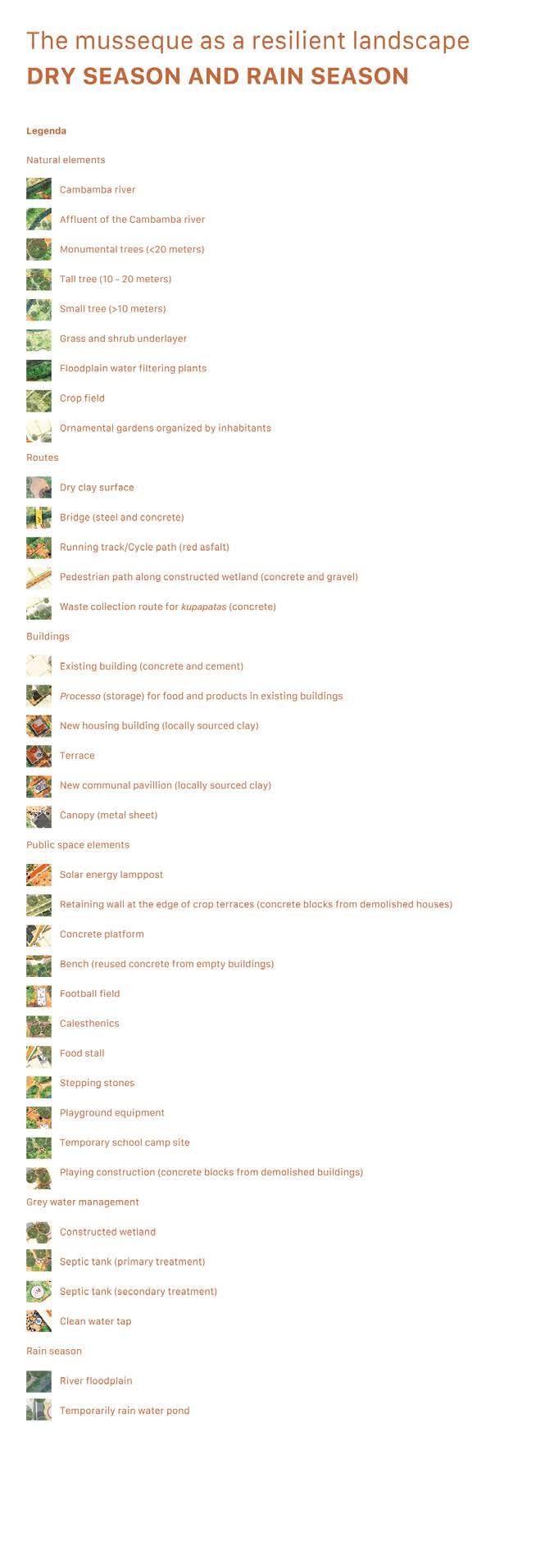

THE MUSSEQUE AS A RESILIENT LANDSCAPE

DRY VS RAINY SEASON

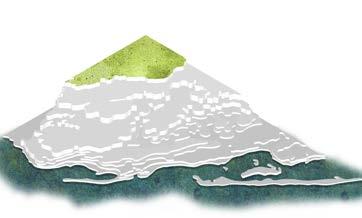

The Cambamba returns to life

a fertile river area for and by the residents of the musseque - dry season

Onion

Hyacinth Bean (Lablab purpureus) Brassica

Zucchini

Onion Tomatoes Okra Carrot

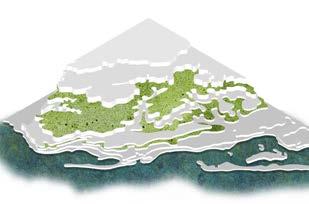

The Cambamba returns to life

a fertile river area for and by the residents of the musseque - rainy season

Oryza glaberrima (African rice)

Taro (Colocassia esculenta)

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum)

Sorghum Sorghum bicolor

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica)

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)

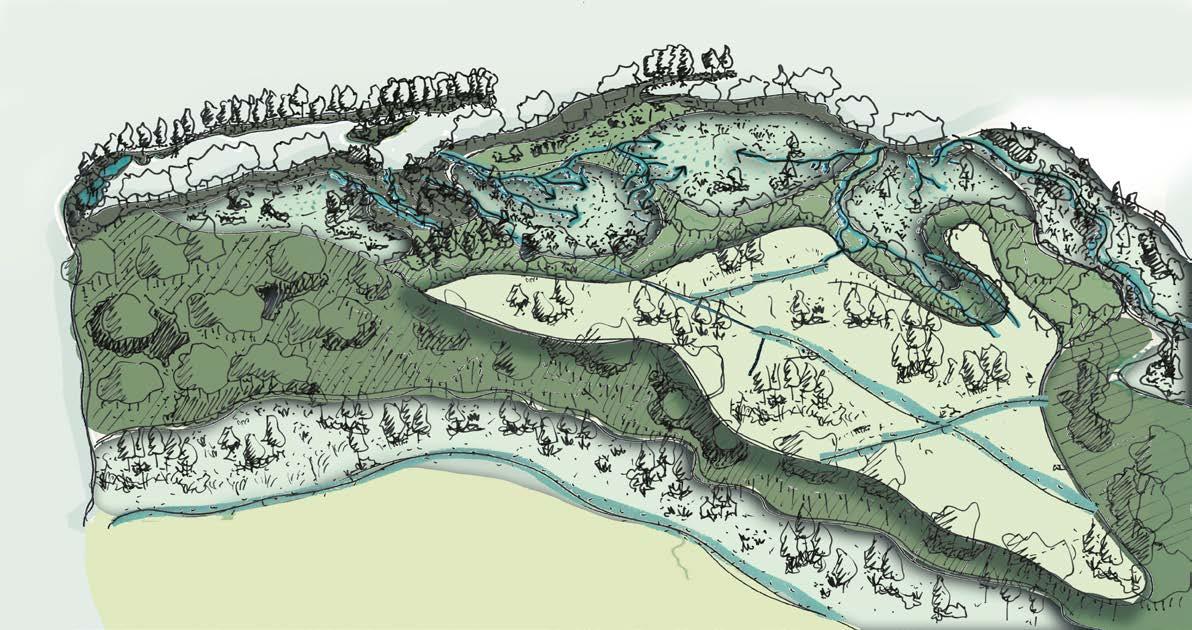

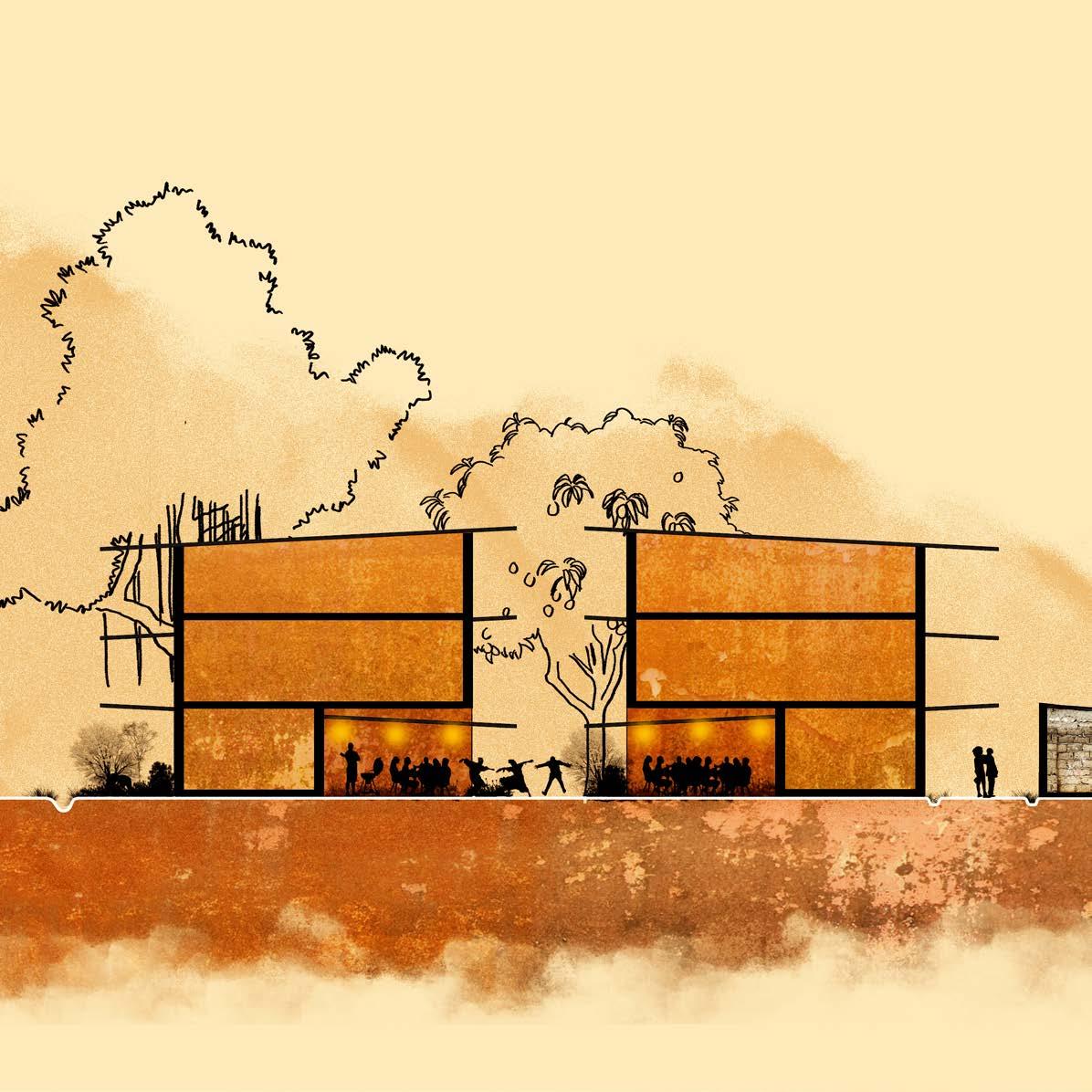

A River Returns to Life: The Cambamba Vision

Once, the Cambamba River was a lifeline — a natural artery running through Luanda. But over time, it became hidden/marginalized/lost its importance. Its banks became crowded with homes, its flow blocked by waste, and its waters polluted. Instead of nourishing the land and people, it became a threat — a source of disease, a danger during floods, and a lost opportunity for connection with nature. In the neighborhood that surrounds it, the Cassequel, life persists with remarkable resilience. Schools, medical centers, informal markets, and gathering spaces serve a community that knows how to adapt. People live close together, under the shade of trees or awnings, selling goods, caring for families, and maintaining a rich web of daily interactions. Yet, the river remains a forgotten neighbor. Now, a design reimagines the river not as a boundary, but as the backbone of a living landscape. A place where water can breathe again.

A Breathing Landscape

With this new vision, the Cambamba River regains space to flood, flow, and expand naturally. The floodplain is liberated from housing, and a waste management system prevents blockages, aiming to keep the river clean. Along this restored edge, new homes are built — not to dominate, but to harmonize with the river’s rhythm.

The riverbanks unfold as a mosaic of biotopes: agricultural fields, riparian systems, grasslands, and forest patches. The different landscapes, people and their activities adapt as the seasons come and go. Rain feeds the crops, and in turn, the people tend the soil — a mutual care between land and community. The neighborhood changes spatially, but its soul remains the same.

Vegetable and fruit intake

VEGETABLE AND FRUIT INTAKE

Self-sufficient production?

SELF-SUFFICIENT PRODUCTION?

VEGETABLES

residents = 43800 kg vegetables/year (480*250g*365 days)

- recommended yearley intake of vegetables and fruits = 400

- 450g/day = 164 kg/year

• recommended yearly intake of vegetables and fruits = 400g

• 450g/day = 164 kg/year

• CONCLUSION: 1/4 (1825 m2) of vegetables

- garden produce = 1-4kg/m2 (twice a year yeald with intensive use = 6kg/m2) - the climate of Angola is favorable

• garden produce = 1 - 4 kg/m2 (twice a year yeald with intensive use) = 6kg/m2

• the climate in Angola is favourable

- average 20kg - 5480kg = 1752

average 20kg • 5840 kg = 1752

10-15kg/tree years)

20-30kg/vine

20-30kg/tree

Available area for food production

AVAILABLE AREA FOR FOOD PRODUCTION

drone shot from the cambamba further south from project area source: UTGSL

= 35040 kg fruit/year (480*200g*365 days)

20kg fruit/plant

20kg fruit/plant

1752 fruit bearing plants individual balcony

1752 fruit bearing plants individual balcony food harvesting

allotment garden/household of 6 = 300m2

allotment garden/household of 6 = 300m2

10 allotment gardens crop area

drone shot taken by UTGSL (the General Technical Unit for Sanitation in Luanda)

Gradient of different biotopes

Rainy season

Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus)

Canna paniculata (Biri) Echinodorus macrophyllus

dragonflies & other insects

African cuckoo

Jungle rice (Echinochloa colona)

Variable flatsedge (Cyperus difformis)

Pink bauhinia (Bauhinia monandra)

small reptiles

Gradient of different biotopes

Floodplains and grey water filtering during dry season

Vetiver (Vetiveria

Wool grass (Anthephora pubescens)

Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon)

Egyptian grass (Dactyloctenium aegyptium)

Vetiver zizanioides)

Prickly chaff flower (Achyranthes aspera)

Natal orange (Strychnos spinosa)

Monkey guava (Diospyros mespiliformis)

The affluents of the Cambamba

Extending the richness of the river area to the musseque

The green-blue routes through the musseque

Water, Always

During the dry season, water is scarce. But here, even greywater is valued. A treatment system filters it through wetlands and tanks, providing clean water for drinking, washing vegetables and sustaining daily life. Public taps scattered across the neighborhood, complete this water cycle.

BIOPODS mycellium pods

The mushroom network eats away at heavy metals, heavy oils, pesticides and other toxins found in the water

CONSTRUCTED WETLAND tertiary treatment

SEPTIC TANK secondary treatment

WATER TANK filtered and clean water

SEPTIC TANK primary treatment

The Island of Awareness and Wonder

At the heart of it all lies the island — the catalyst. A place for gathering, for learning, for dreaming. Children learn about the value of water, trees, and soil. Elders find peace in the shade. The island becomes an outdoor classroom, a sanctuary for both people and wildlife — a shared space that reconnects everyone to the rhythms of nature.

Prosopis juliflora

Leucaena Leucocephala

Anthephora

Healthy community through movement and sport

Social and health-related problems such as drug or alcohol addiction also play a role in this neighborhood - and for many sports are a way out. In Luanda, streets in the musseques are too narrow for running, and the highways are dangerous. This design introduces a 3km running track, the red path, winding through riverbanks, fields, markets, homes old and new. Here not only athletes but also cyclists, wanderers, children find a place. Solar lighting and water points line the circuit, making it safe and accessible even at dusk or dawn. This track is more than infrastructure — it is a gift of space, health, and opportunity for young generations.

Growing with the Seasons

The design embraces the stark contrast between dry and wet seasons. From October to May, floodplains and constructed wetlands swell with water. Crops planted near the river are chosen for their resilience, while ditches guide water to irrigate savannah grasses and woodlands. A well-functioning ecosystem attracts the birds and dragonflies, natural predators of the mosquitoes that would otherwise breed in these waters.

Fruit-bearing trees and monumental native species accentuate the landscape, chosen for their dry- or wetsoil tolerance. Their shade and color, become seasonal gifts. Open and closed green spaces create a wild, adventurous world for children to explore — a natural playground filled with stories waiting to unfold.

African Palm-swift

snakes

Public Space as daily life

Shade trees, simple concrete plateaus, and small canopies create natural gathering points: by bridges, on corners, near markets. These places are more than pauses in the landscape — they are stages for daily life. Here street vendors sit, neighbors chat, elders watch children play. Football fields are slightly sunken, doubling as rainwater reservoirs. Playgrounds are built with repurposed materials from demolished buildings, turning memory into imagination — concrete blocks become benches, walls, or climbing structures.

New houses are arranged with facing terraces, creating semi-public zones where daily life happens in a shared space. This openness supports connection, allowing the neighborhood to breathe and grow together.

Agrostis

Cynodon

Dactyloc tenium

Leucaena Leucocephala

Prosopis juliflora

A Circular, Affordable Neighborhood

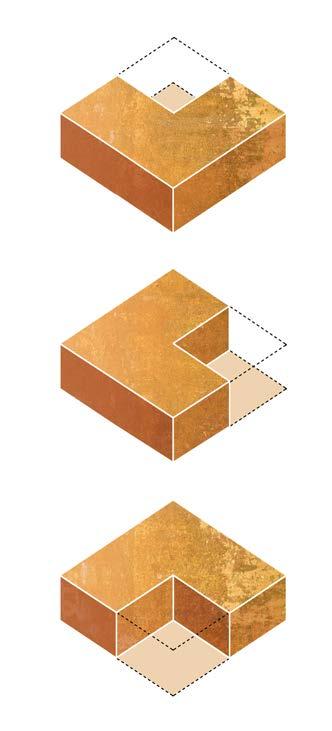

This transformation is rooted in affordability and reuse. Materials from old houses are given new life — as furniture, retaining walls, or play structures. Architecture remains modest, limited to one to three stories, preserving the character of the musseque.

Zungueiras can now grow the crops they sell, whether in backyards, open fields, or market gardens. Some buildings are repurposed as food storage hubs, their walls turned into canvases for local artists, creating visual landmarks and a sense of orientation.

House replacement

house 3

75m2

25 m2 open area

house 2

75m2

25 m2 open area

house 1

75m2

25 m2 open area

section BB’

0 5 10m

VEGETATION

Kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra)

- 23 m to 38 m

- hosts to a staggering array of both plant and animal species, including birds and frogs

- needs a lot of room

- monumental

Woman’s tongue (Albizia lebbeck)

- 18 to 30m

- Native

- tropical to subtropical sandy river beds and savannahs

African tulip tree (Spathodea campanulata)

- native

- sheltered from the wind

- commonly attract hummingbirds

- 7 to 25m

Siamese cassia (Senna siamea)

- often used as shade tree in cocoa, coffee and tea plantations - 18 m

African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis)

- up to 20m - native - rivers and forests

Lead tree (Leucaena leucocephala)

- 7–18 metres - makes the soil fertile

Rhodesian mahogany (Afzelia quanzensis)

- dry areas

- native

- thrives in dry regions with minimal moisture

- 20 m

Papaya (Carica papaya)

- attracts birds

- well known for the sweet and juicy fruits

- harvest all year round

- 6 to 10m

- grows well along walls or buildings

Mango tree (Mangifera indica)

- The timber can be used for furniture

- 10 to 20m

- its leaves and bark can be used as yellow dyes

Banana (Musa spp)

- 3m - marshlands, semi-marshlands, slopes

- arid areas

- 4 a 8m

- fruit is edible with a high level of sacharose - can be invasive

Mesquite (Prosopis juliflora)

Royal poinciana (Delonix regia)

- 8 to 12m

- orange/red flowers

Aroma (Dichrostachys cinerea)

- 2.5m to 7m

- pods rich in nutrients

- flowers can be a source of nectar for honey production - medicinal properties

Lipstick tree (Bixa orellana)

- 6 m to 10 m - red/pink - dye

- riparian systems

- Blossoms attract butterflies

- pink blossom

- 5 to 7m

- thrives with minimal water and exhibits drought tolerance

- 3 to 12m

- 5m to 20m

- native

- alluvial soil; bushy places near stream

Pink bauhinia (Bauhinia monandra)

Moringa (Moringa oleifera)

Sand false-marula (Lannea antiscorbutica)

Carrot-tree (Steganotaenia araliacea)

- dry spots

- native

- beautiful!

- 2 to 7m

- 5m

- river shores and temporarily flooded areas

Natal

orange (Strychnos spinosa) Maboque

- 1 to 9 m

- known locally as Maboque

- native

- exceptional drought tolerance and efficiently stores water

Piassava palm (Raphia vinifera)

Monkey guava (Diospyros mespiliformis)

- Adapted to its native savanna habitat, monkey guava exhibits excellent drought tolerance, thriving in dry conditions with minimal watering - 20m

Wool grass (Anthephora pubescens) Otjimbele

- native - 30 to 100cm

- Revegetation of degraded lands

- It is extremely drought tolerant, but intolerant of waterlogging and flooding

Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon)

- native - recognized for its resilience and adaptability

Egyptian grass (Dactyloctenium aegyptium)

- native

- shows up on barren land and grows quickly - drought resistance and optimal water retention

Vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides)

- 2 m

Prickly chaff flower (Achyranthes aspera)

- native - Prickly chaff flower grows wild in wasteland areas around the world

- Open dry places

Oryza glaberrima (African rice)

Taro (Colocassia esculenta)

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum)

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor)

Water spinach (asian variety)

Sweet potato

Hyacinth Bean (Lablab purpureus)

- soil-improving properties as a green manure

Pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan)

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)

Cabbage (Brassica)

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus)

Zucchini (Cucurbita pepo)

Onions (Allium

- 2,5m - riverbanks to water gardens - native

Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

cepa)

Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus)

Canna paniculata (Biri)

- 1,5 m

Echinodorus macrophyllus Chapéu de couro ?

- water gardens Brasil - 50cm

Jungle rice (Echinochloa colona)

- native - Waste places, cultivated fields

- Commonly found in wetlands and rice paddies

- 30 to 100 cm

Variable flatsedge (Cyperus difformis)

- growing as a weed in rice fields

- native

- 80 cm

- Freshwater, disturbed wetlands, shallow pools, floodplains

Barleria elegans (Barleria elegans)

- native - attract pollinators

- drought resilience and low maintenance requirements - floresta densa e savana arborizada. Geralmente em lugares secos

Justicia flava

- Open forest, dense forest and wooded savanna; riverbanks and disturbed sites

REFLECTION

Growing up in Portugal and pursuing my studies in landscape architecture in Belgium and the Netherlands broadened my understanding of the vital role this discipline plays in shaping public spaces that foster healthy societies.

In Europe, the integration of landscape architecture with urban planning has begun to reach the necessary scale to safeguard the unique qualities of public spaces in the face of emerging climate challenges. Strategies such as creating wadis and replacing pavement with vegetation are essential for mitigating flood risks, while the introduction of trees, green roofs, and vegetated façades helps cool and refresh the urban atmosphere. But how can formal structures be embedded in an unplanned setting of the Angolan public realm, where people and their activities are the ones shaping it? This project explores climate adaptation by centering everyday life in Luanda—how people use space, how they live, and the meanings they assign to their surroundings. It embraces the coexistence of formal structures with the informality of the musseques, blending both into a shared, dynamic ecosystem. Angola’s soil is rich, but its potential remains largely untapped. Despite the country’s fertile ground, most of the food consumed is imported. The knowledge of working the land has faded for many, and the richness of Angolan nature — its wild abundance, its quiet resilience — often goes unnoticed in daily life. And so, through design, the Cambamba River finds its place again — not as a boundary, but as a lifeline. The

community remains. The challenges persist. But now, they are met with a landscape that supports, invites, and inspires. A river that breathes. A neighborhood that lives outdoors. A future shaped by water, care, and imagination.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful for the time spent in Luanda and for the generosity of the people who welcomed me into their homes. Angolans are very charismatic, relaxed, and extremely funny, no matter what subject comes up in a conversation.

Research, interviews, and observations guided my understanding, but it was the people themselves who revealed the true essence of Luanda’s public space.

Above all, I want to thank my xará for welcoming me into her life and work, and for helping me grasp the true purpose behind this project.

To Adingui and Isidro, thank you for opening your homes and sharing the reality of the musseque with me.

To the residents of the musseque – young and old - your curiosity, honesty, and constant presence reminded me that I am a guest in this space. Your voices taught me that this design must be approached with care, humility, and deep respect for you and for your homes.

I am also deeply grateful to the following people, whose generous insights provided the knowledge I needed - technical, social, ecological, urban, geological, hydrological, architectural, and historical - to shape this work with depth and responsibility.

Arch. Amílcar Lutucuta - National Director of Land Management and Housing of the Ministry of Public Works, Urban Planning and Housing

Engr. Henrique Tavira - General Director of UTGSL (Unidade Técnica De Gestão De Saneamento De Luanda)

Arch. Diosseca Coelho – Architect and urbanist in UTGSL (Unidade Técnica De Gestão De Saneamento De Luanda)

Erica Tavares - Angola country coordinator at US Forest Service, Co-founder and Counsellor of EcoAngola, environmental biologist, African ecologist and consultant

Arch. Malwa Teixeira Pires

Arch. Belarmino Kiwla and the BS Architecture team

DO.LADO.B architects

Dr. Calunga Quissanga - Vice-governor of the province of Luanda for technical and infrastructure services

Dr. Silva Hossi - Deputy Director General of the IGCA Institute (Instituto Geográfico e Cadastral de Angola)

Dr. Gabriela Pires – Professor in geology at the

Agostinho Neto University

Dr. Divalo Domingos Silva – Enginneer at EPAL (Empresa Pública de Águas) and professor at the Agostinho Neto University

Dr. Gijs Simons – hydrologist in FutureWater (NL)

Sergio E.L. Ferreira – African Business Strategist

Vladimir Russo - technical Director of Holísticos (environmental consultancy) and executive director of the Kissama National Park Foundation

To my graduation committee, Marieke Timmermans, Aura Luz Melis and Philomene van der Vliet, thank you for your guidance and support throughout this journey.

Most importantly, this project would not have been possible without the support and care of my housemates, my colleagues and Dutch, Portuguese and Belgican friends. You all believed and encouraged me in this somewhat overwhelming journey.

To my family, and especially my parents - thank you for supporting me from far away in every way you could, and for passing on the values of Angolan culture that anchor this work. And to Sander, thank you for your time, your patience and support throughout this whole journey.

REFERENCES

De Raeymaeker, J. (2012) À descoberta de Angola (Discovering Angola)

Jornal de Angola (Angola’s national newspaper)

Planoluanda presentation of PDGL (Plano geral diretor geral de Luanda) (Luanda general master plan)

Steenbergen, C., Reh, W. (2011) Metropolitane landscapsarchitectuur (Stedelijke parken en landschappen)

M. T. Pires (2014). Densificacão vs retracção: Que futuro para as reas autoconstruídas de Luanda? Repensar a transformação de um território urbano [Master’s thesis, Faculdade de Arquitetura de Lisboa]

J. Mendelsohn, S. Mendelsohn and N. Nakanyete (2010). An expanded assessment of risks from flooding in Luanda

Development workshop (2016). Water Resource Management under Changing Climate in Angola‘s Coastal Settlements

G.J.P.T. Pires (2007) Caracterização Geológica e Geotécnica dos solos de Luanda para o Ordenamento do Território [Master’s thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Departamento de Geologia]

M.P.C. Pedro (2023) A flora e vegetação da bacia hidrográfica do Baixo Cuanza, Angola. [PhD thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências)

Lecture Climate Resilience in Action at Pakhuis de Zwijger, Amsterdam

De bron van alles, Blauwe Kamer Nr. 2 2024

B. J. Huntley, V. Russo, F. Lages, N. Ferrand (2019). Biodiversity of Angola. Science & Conservation: A Modern Synthesis

https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/especial-1-de-junho-muitascriancas-a-espera-de-um-futuro-mais-risonho/

https://www.a1v2.pt/portfolio/luanda-cidade-mundial-plano-director-geral/

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/rising-sea-levels-besieging-africas-boomingcoastal-cities

https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/is-eastern-africas-drought-the-worst-inrecent-history-and-are-worse-yet-to-come/

http://www.imogestin.co.ao/projecto/centralidades/

https://www.encyclo.nl/begrip/wadi

http://www.landscapearchitecture.org.uk/history-of-landscape-architecture-2/

“South Africa drought: Cape Town faces water rationing,” BBC News, January 30, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-42896833

Forecasting African Futures (podcast series Into Africa)

https://www.ecobrickexchange.org/views/active_projects?p=15 https://www. ecobrickexchange.org/views/home

https://www.calameo.com/read/005887431c5a16171faa7

https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/caputo-o-antigo-bairro-doseucaliptos/ floresta tempo colonial segundo reza a história

https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/viagem-ao-passado-emblematica-

zona-de-luanda-fundada-pela-comunidade-tocoista/pequena clareira de terra vermelha situada num extenso matagal habitado por animais selvagens

https://www.atlasofmutualheritage.nl/en/page/6849/luanda mapas antigos

https://www.historia.uff.br/impressoesrebeldes/revista/negreiros-rebeldes-e-aindependencia-do-brasil/

https://www.alamy.com/st-paul-de-loanda-luanda-angola-c1854-1883-artistunknown-image262762786.html

https://www.prints-online.com/angola-luanda-c1875-608452.html

https://pt.weatherspark.com/y/74193/Clima-caracter%C3%ADstico-em-LuandaAngola-durante-o-ano

https://humanspace.weblog.tudelft.nl/african-public-spaces/

https://www.gebiedsontwikkeling.nu/artikelen/designing-urban-microclimate/ https://www.verangola.net/va/pt/032018/ComercioIndustria/11292/Zungueirasde-Luanda-trabalham-quase-10-horas-por-dia-para-sustentar-a-casa.htm

https://ewspconsultancy.com/2020/11/07/case-study-angola-field-system/

https://dw.angonet.org/friday_debate/vulnerabilidade-resilia-ncia-ambiental-eadaptaa-o-dos-assentamentos-em-luanda/

https://valoreconomico.co.ao/artigo/luanda-ficou-um-edificio-bonito-massem-casa-de-banho-porque-os-hidraulicos-nao-sao-consultados

https://pt.slideshare.net/DevelopmentWorkshopAngola/ana-julante-e-webaquirimba-impactos-da-variao-climtica-sobre-inundaes-e-escoamento-pluvialem-luanda-19-julho-2013#17

http://www.ppa.pt/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2.-Manuel-Quintino.pdf

https://theconversation.com/lessons-from-semi-arid-regions-on-how-to-adaptto-climate-change-56936

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/video/2022/11/22/strengthening-climatechange-adaptation-and-resilience-in-flood-prone-dar-es-salaam

LMUP green lung, VE-R

Ilubirin wetlands, VE-R

RIO SECO: GREEN NETWORK, Building Society for Architecture / Belarmino Santos “Kiwla”

Nossa Ginga: Projecto de reativação do centro de Luanda. Do lado b - do lado ur[b] ano

City of 1000 tanks, Ooze

A House in Luanda, Taller architects for the Lisbon Architecture Triennale