EDGES OF CHANGE

A bottom-up urban design strategy to restore identity, balance, and connection in Moscow’s periphery.

A bottom-up urban design strategy to restore identity, balance, and connection in Moscow’s periphery.

A bottom-up urban design strategy to restore identity, balance, and connection in Moscow’s periphery.

Daria Agranovskaya

Master in Urbanism

2025

Committee

Iruma Rodríguez Hernández / mentor

Léa Soret

Alexandra Chechetkina

Amsterdam Hogeschool voor de Kunsten Academie van Bouwkunst

Special gratitude to my parents for the love and care they gave

Hope they will keep this book on the shelf.

CONTENTS

CONTEXT

2.1 Legacy of Mass Panel Housing

2.2 Key Urban Challenges

2.3 Moscow: Urban Structure and Development Dynamics

UNDERSTANDING

3.1 Origins of Mass Development and Its Spatial Distribution in Moscow

CITY PLAN AND STRATEGY

4.1 Current Top-Down Urban Strategy

4.2 Critique of Existing Strategies

4.3 My Design Position

INTERVIEWS

5.1 Resident Perspectives from the Target Areas

ANALYSIS

6.1 Urban and Social Dynamics in Spatial Planning

THE MOST COMPLEX AREAS

7.1 Three Districts and Their Key Characteristics

DESIGN APPROACH

8.1 Design Philosophy

8.2 Methodological Positioning

MOST VULNERABLE AREA

9.1 Northern Izmailovo: Challenges and Existing Qualities

9.2 References

FIRST STEP

10.1 Entry Points and Doorstep Activation

DESIGN

11.1 Design Strategies and Spatial Qualities

11.2 Phased Strategy for Quality Public Spaces

11.3 Adaptation of Design to Urban Conditions

DESIGN EXAMPLES

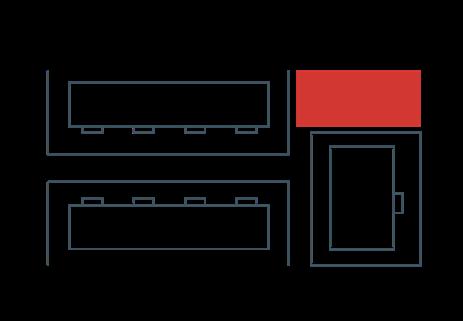

12.1 Pavilion Set as a Design Prototype

12.2 Multifunctional Neighborhood Spaces

USAGE SCENARIOS & REALISATION

13.1 Everyday Use Cases & Seasonal Adaptation

13.2 Stakeholder Involvement Over Time

13.3 Phased Implementation Plan

SIX URBAN QUESTIONS

14.1 Public–Private Transition

14.2 Financial Dependence

14.3 Functional Disbalance

14.4 Identity

14.5 Leisure Dependence

14.6 Transportation Dependence

CONCLUSIONS

15.1 Methodological Impact, Benefits, and Limitations

STEPS FOR THE FUTURE

16.1 Path to Implementation and Personal Vision

APPENDIX

17.1 Path to Implementation and Personal Vision

17.2 Image and Data Credits

17.3 Literature and Research Sources

This chapter introduces the historical and social foundations of Moscow’s mass housing legacy. It outlines how Soviet-era panel housing has shaped today’s urban environment and identifies the key challenges resulting from this development model.

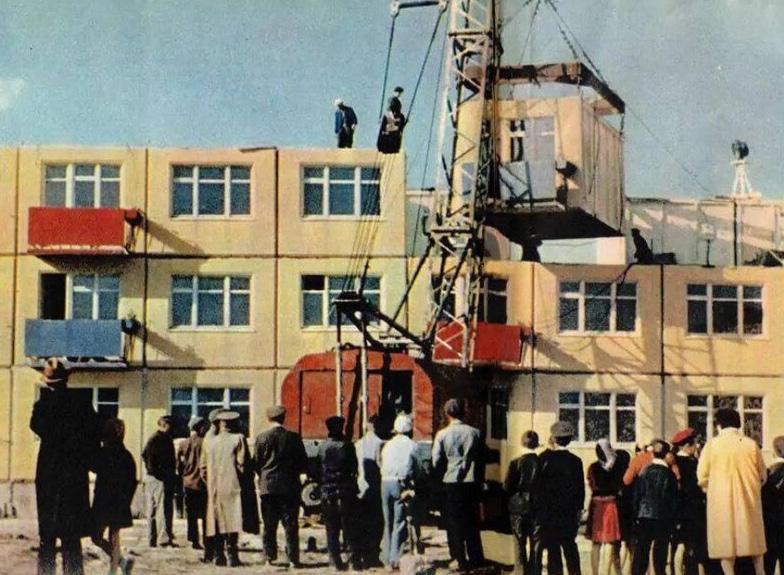

The legacy of mass housing construction in Russia — especially during the postwar decades — left a profound imprint on the urban landscape. From the 1960s through the 1980s, millions of square metres of prefabricated panel housing were built across the country in an effort to solve one of the most pressing challenges of the time: a nationwide housing shortage.

These developments took many forms — from standardised microrayons (microdistricts) to large-scale monofunctional residential blocks that often lacked the full programme originally envisioned in early Soviet planning. Whether part of an integrated urban scheme or not, what united these areas was the typology of panel construction and the functional singularity of their environments: housing was the dominant — and often the only — urban function present.

This form of urbanisation was born out of necessity and ambition. At the time, millions of families lived in overcrowded communal apartments or in poor-quality barracks. Mass housing promised privacy, hygiene, and dignity. It was an ambitious social project — made possible by the industrialisation of architecture.

However, the spatial consequences of this speed-oriented development gradually became evident. While central districts of cities retained a mix of urban functions and fine-grained street life, the peripheral areas built under the mass housing model grew into monofunctional zones, separated from economic, cultural, and social activity. Over time, this physical separation

fostered social isolation, mobility dependency, and a lack of local identity.

Today, these panel housing areas host the majority of Moscow’s population and remain a dominant feature in cities like Yekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, and others across Russia. Yet their urban potential remains largely untapped.

This research focuses on understanding the spatial and social conditions of these panel-dominated environments. Not all of them are microrayons by strict definition, but all share the DNA of mass, mono-functional, standardised development. The aim is not to romanticise or reject this legacy, but to question:

What kind of everyday urban life does this form of development enable — and what does it suppress?

Through this lens, I explore how targeted, socially aware spatial interventions can help reintegrate these areas into the broader urban fabric — not through demolition or total reinvention, but by working from within the spaces people already inhabit.

Sorrounded or restricted in the size by indstry 2

Financial and leisure centre dependence 3 Imbalance between commercial and residential

Not attracted to people outside of the district 5

Commuting dependence on public transportation & a high number of individual cars

Unclear transitionsPublic/private

Territory in ha

City center 105.4

Urban functional area 2820 Metropolitan area 18940

Territory in ha

City center 891

Urban functional area 3740 Metropolitan area 30370

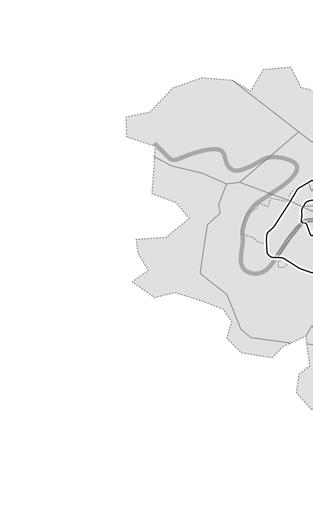

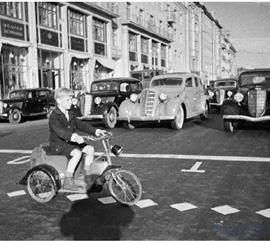

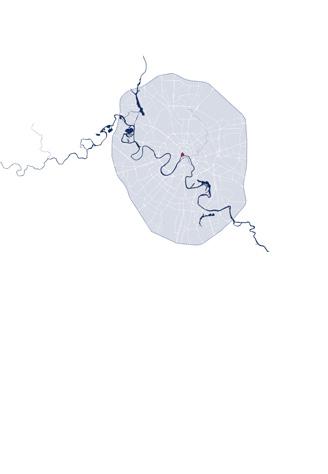

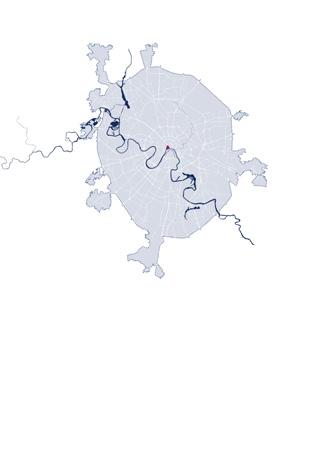

1806 - 1852 Kamer - Kollezhsky rampart

mil. people : 0.25 territory km² : 80 reason : natural protection

1917 Moscow Encircle Railway

mil. people : 1.1 territory km² : 230.7 reason : improve communication with neighboring cities

1910 - 1916 Moscow

1935 General plan of Moscow

mil. people : 3.6 territory km² : 320 reason : city growth

mil. people : 6.4 territory km² : 420 reason : improve communication on the outskirts

mil. people : 8.6 territory km² : 1010 reason : agglomeration growth along main diametral roads

mil. people : 12 territory km² : 2510 reason : economcal potential

A deep dive into the origins and logic behind mass urban development in Moscow. The chapter traces the spatial logic, historical reasoning, and urban positioning of mass housing, laying the groundwork for understanding the scope of the issue.

After the Russian Revolution, private property was abolished, and many middle- and upper-class apartments were converted into communal apartments (kommunalkas) where multiple families shared facilities.

1861 Serf Emancipation and Migration to big cities

Industrialization led to dense worker districts with overcrowded, low-quality housing (baraks). This environment heightened socio-economic divides and brought forth housing challenges that sparked the need for reform.

This distribution program promoted mass access to housing and equality among residents but also left lasting marks on Moscow’s urban neigbourhoods.

After the Soviet Union’s collapse, economy, phasing out state-subsidized become commodified, attracting and foreign investors.

1959

To overcam the greaat housing shortage and reduce the housing cost the mass construction of prefabricated units with minimal-cost apartment blocks (khrushchyovki) started.

collapse, Moscow shifted to a market state-subsidized rent and allowing housing to attracting investment from wealthy citizens

Privatization vouchers allowed citizens to acquire state assets

Property prices in Moscow began to rise significantly, with average prices doubling before the global financial crisis in 2008. This rapid increase created a widening gap between wealthy and low-income residents, making homeownership increasingly unattainable.

1998 Resettlement of communal apartments

The program for gradually resettling communal apartments has started. Resettlement will occur in priority order according to the national program.

Revival of Housing Cooperatives - as a potential solution to affordability issues, allowing residents to collectively manage and maintain their living spaces.

The renovation program for old emergency housing has started, including the demolition of buildings and the construction of new

2024 Increasing the key interest rate on loans to 19%

Leads to reduced demand for home purchases, increased rental demand, and slowed new development activity and potentially compromising quality as developers cut costs..

This change could also pave the way for a more stable and balanced housing with focus on adaptive reuse and energy efficiency, market in the long run.

Parameter

Density (people/ha)

Avg. distance to everyday infrastructure (meters)

Public space per resident (m²)

Social infrastructure availability (per 10,000)

Commercial vs. residential mix (ratio)

Avg. access time to public transport (min)

Urban environment quality (score 1-10)

Social cohesion index (score 1-10)

Building stock age (median, years)

Self-reported well-being (score 1-10)

Approximately 100-150 cities in Russia have a similar urban problem.

This is a problem in post—Soviet industrial centers, where the main housing stock is panel apartment buildings built in the 1960s and 1990s.

15 out of 16 million cities in Russia have a structural dependence on residential development and face similar problems.:

• The central part is compact and historical

• The majority of the population lives in neighborhoods with the same building patterns.

• Function imbalance (residential > commercial)

• Weak ties between residents

• Excessive dependence on the city center and public transport

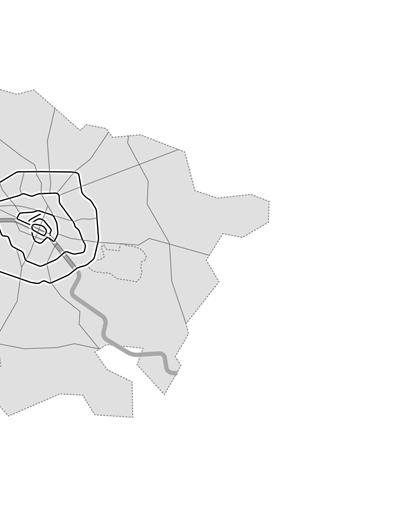

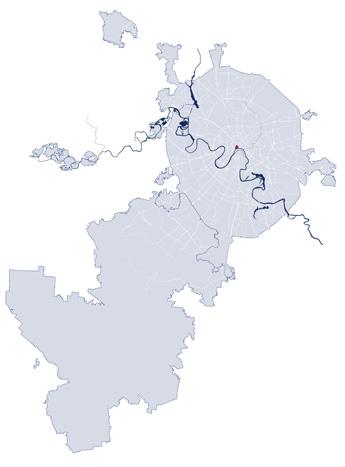

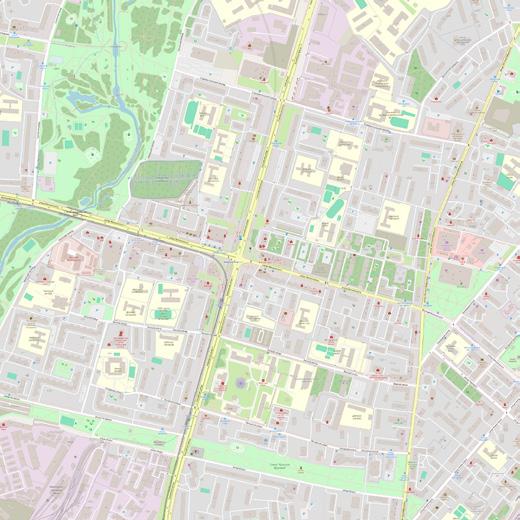

The Moscow agglomeration presents a layered urban landscape shaped by waves of expansion and diverse planning ideologies. From the dense historical fabric of the inner city to the large-scale panel housing estates at the periphery, districts across Moscow reflect varied spatial, social, and functional conditions.

As mass development spread throughout the second half of the 20th century, different settlement patterns began to emerge. Closer to the city centre, a fragmented gradient of mixeduse districts evolved—often combining older buildings with mid-century housing and scattered commercial activity. These areas, though still residential in nature, show higher levels of pedestrian infrastructure and accessibility to public transport, cultural services, and workplaces.

In contrast, the outer belt of the agglomeration is dominated by predominantly monofunctional residential districts. These areas—largely shaped by Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and post-Soviet development phases— were often planned as self-sufficient neighbourhoods but in reality remain functionally disconnected from the wider urban system. Here, everyday life is largely confined to long commutes, underutilised open spaces, and a limited local economy.

Despite their differences, all districts across the agglomeration are interconnected through a common metropolitan dynamic—where people, resources, and opportunities flow inwards toward the centre. Understanding these district typologies is essential to unpacking how current structures impact people’s lives, and how this fragmented geography amplifies the city’s structural challenges.

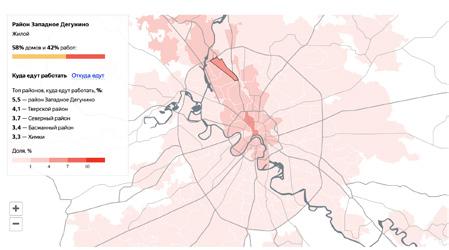

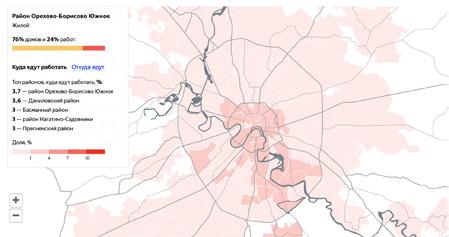

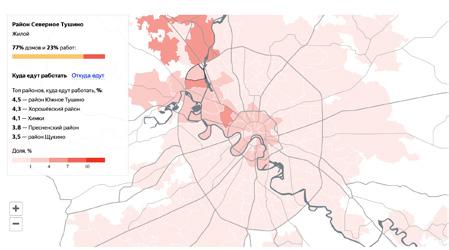

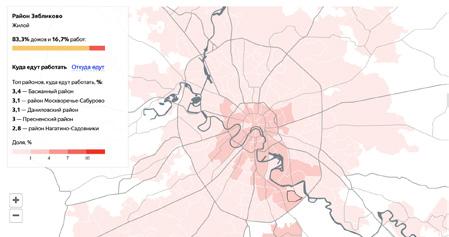

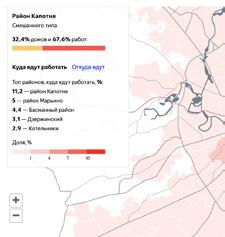

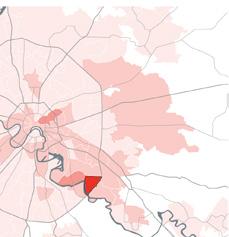

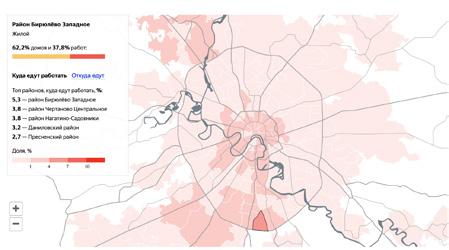

In districts where housing dominates and other functions are limited, daily mobility patterns tend to follow a strong centripetal logic. Most residents commute toward the city centre for work, services, and culture, creating a radial flow that reinforces dependence on central Moscow.

Only a small percentage of the population works beyond the city’s ring roads — typically in areas with specific

employment clusters such as industrial zones or airports (e.g., Northern Tushino or Kapotnya).

This movement pattern puts strain on public transportation systems and highlights the urgent need to diversify functions within residential areas to reduce long-distance commuting.

District - west Dergunino

58% work 42%

District - south Orehovo-Borisovo

76% work 24%

- northern Tushino

77% work 23%

District - Zyablikovo

83,3% work 16,7%

- Kuntsevo

- Kapotnya

32,4% work

District - Tepliy Stan

District - Kuzminki

District - west Birulevo

District - Ivanovskoye

7% territory

10 % living / 1 mln. people

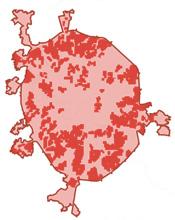

The city center of Moscow occupies only 7% of the total territory but accommodates around 10% of the population—approximately 1 million people. This area is characterized by compact urban density, mixed-use development, and a highly walkable street network. Public spaces, cultural institutions, and commercial functions are deeply integrated into the urban fabric, supporting spontaneous interactions and a high level of urban vibrancy.

Due to its accessibility and richness of amenities, the city center presents fewer challenges in terms of public-private transitions, functional balance, and leisure or transportation dependence. It operates as the economic, political, and cultural core, naturally drawing resources and activity toward itself.

93% territory

68 % living / 9 mln. people

Moscow’s microrayon-based outskirts cover approximately 93% of the city’s territory and house nearly 9 million people—68% of the population. These areas are predominantly composed of residential panel block structures with lower overall building density and limited functional diversity. Despite a higher gross population, net density remains fragmented due to expansive open spaces, road infrastructure, and non-walkable zones.

These peripheral districts face several structural challenges: unclear transitions between public and private space, strong dependence on the city center for services and employment, limited identity-forming landmarks, and imbalanced functional programming, often lacking accessible cultural or leisure infrastructure. Public mobility tends to rely heavily on a few metro lines and private vehicles, making daily commuting essential for access to urban life.

This chapter analyzes current governmental strategies for urban redevelopment, particularly the large-scale demolition and reconstruction plans. It critiques their top-down nature and misalignment with the social and spatial realities of the city.

The Moscow government is currently implementing one of the largest housing renovation programs in the city’s history, targeting the transformation of over 5,000 residential buildings, many of which are panel block houses built between the 1950s and 1980s. The strategy primarily focuses on the demolition of outdated housing in peripheral areas, replacing it with higher-density, modern residential developments.

This urban renewal is structured around a citywide planning framework developed through a competitive process involving major design offices. The selected concept aims to increase building height and density, introduce mixed-use development, and improve the quality of the urban environment. It promotes reorganized street layouts,

clearer pedestrian connections, and the inclusion of public and green spaces within new neighborhoods.

The program affects over 350,000 residents and spans across many outlying districts. New buildings constructed as part of this initiative are often up to 14–20 storeys tall—significantly higher than the 5-storey housing they replace. The city justifies this densification as a response to housing shortages and urban growth, planning to rehouse residents within the same area or adjacent plots.

While the plan aims to modernize infrastructure and improve housing standards, its implementation represents a radical spatial transformation of Moscow’s outer districts, reshaping both the physical structure and the social dynamics of these neighborhoods.

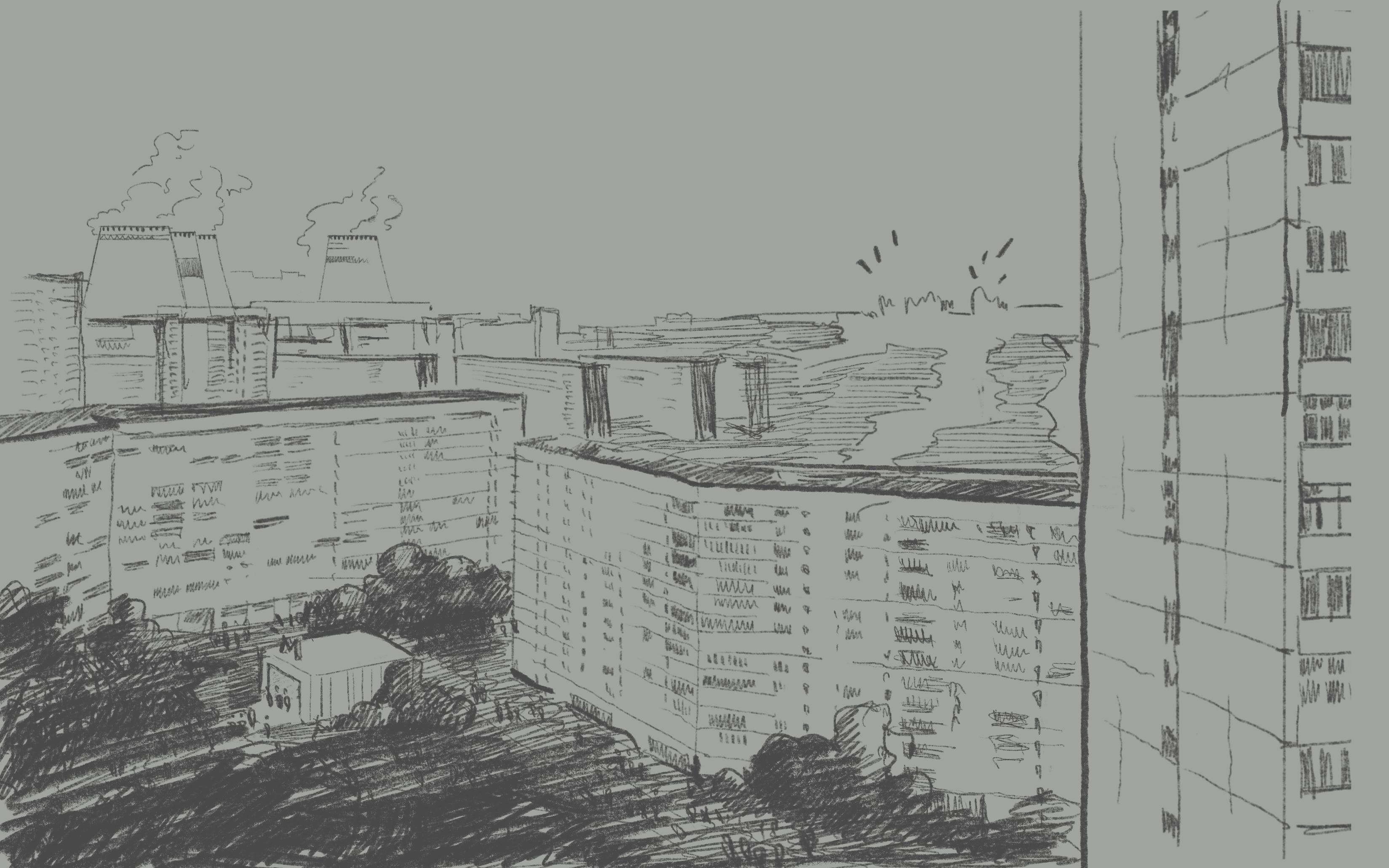

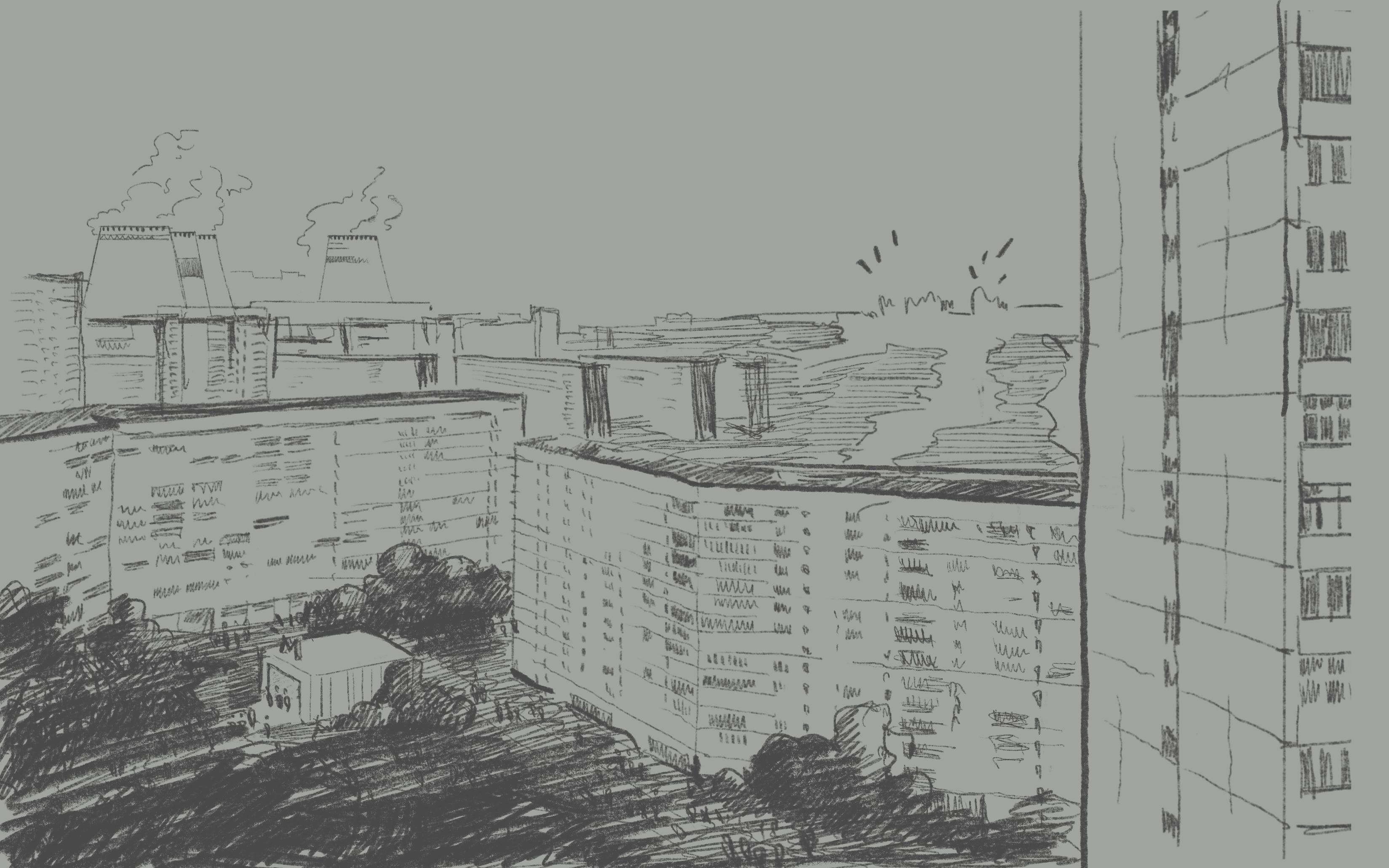

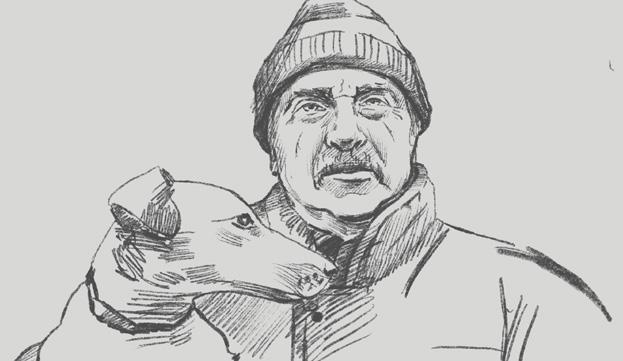

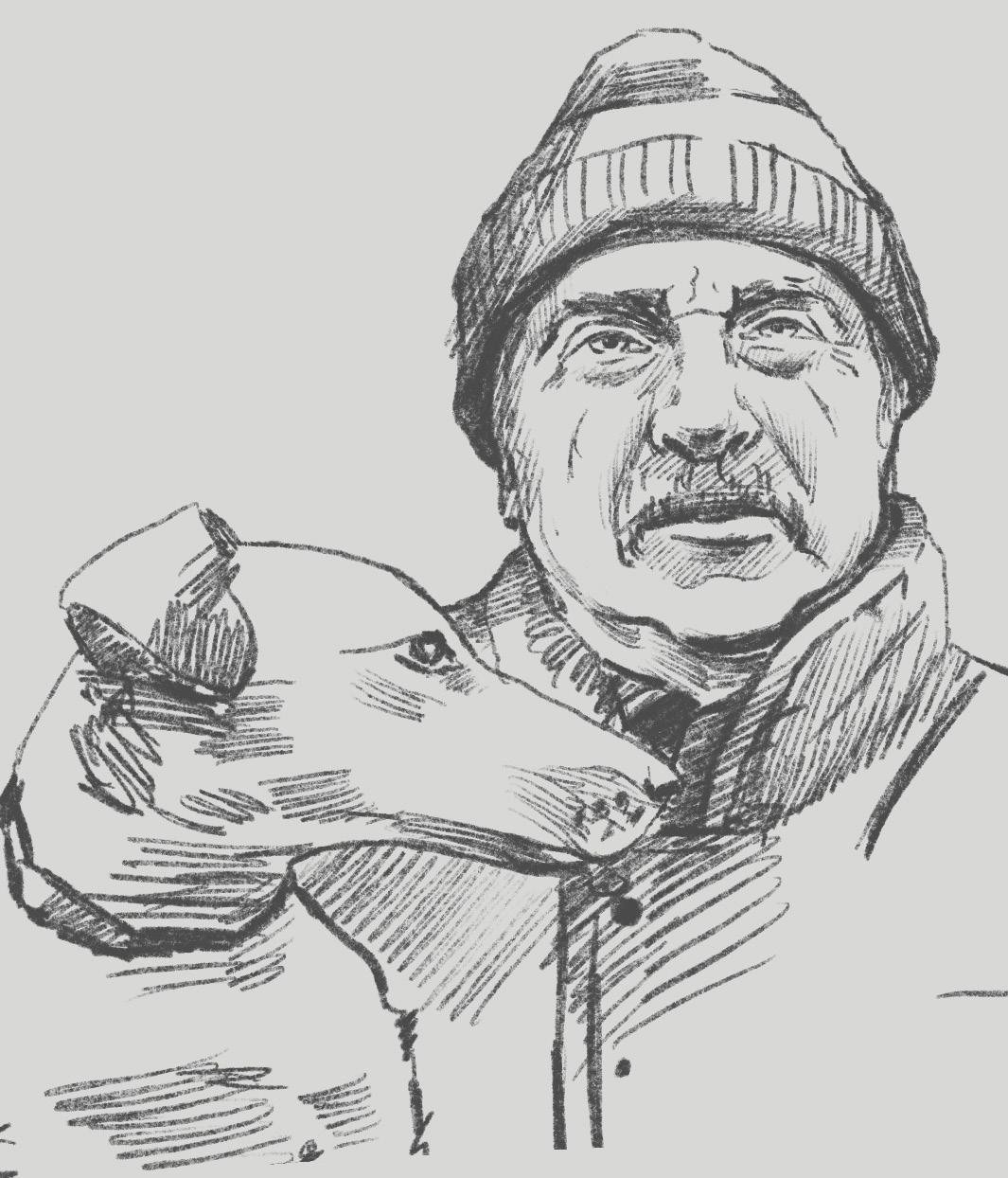

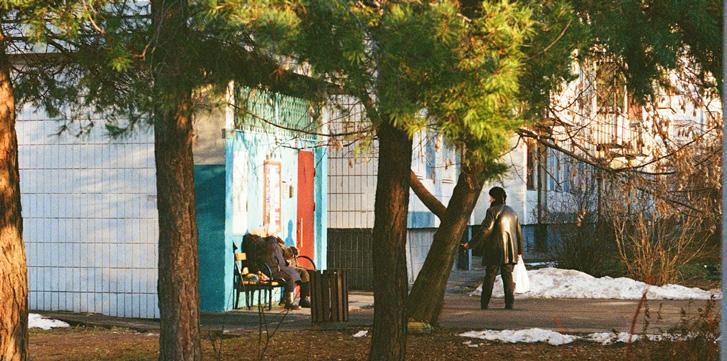

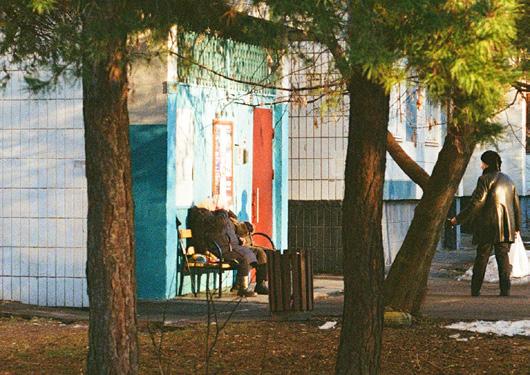

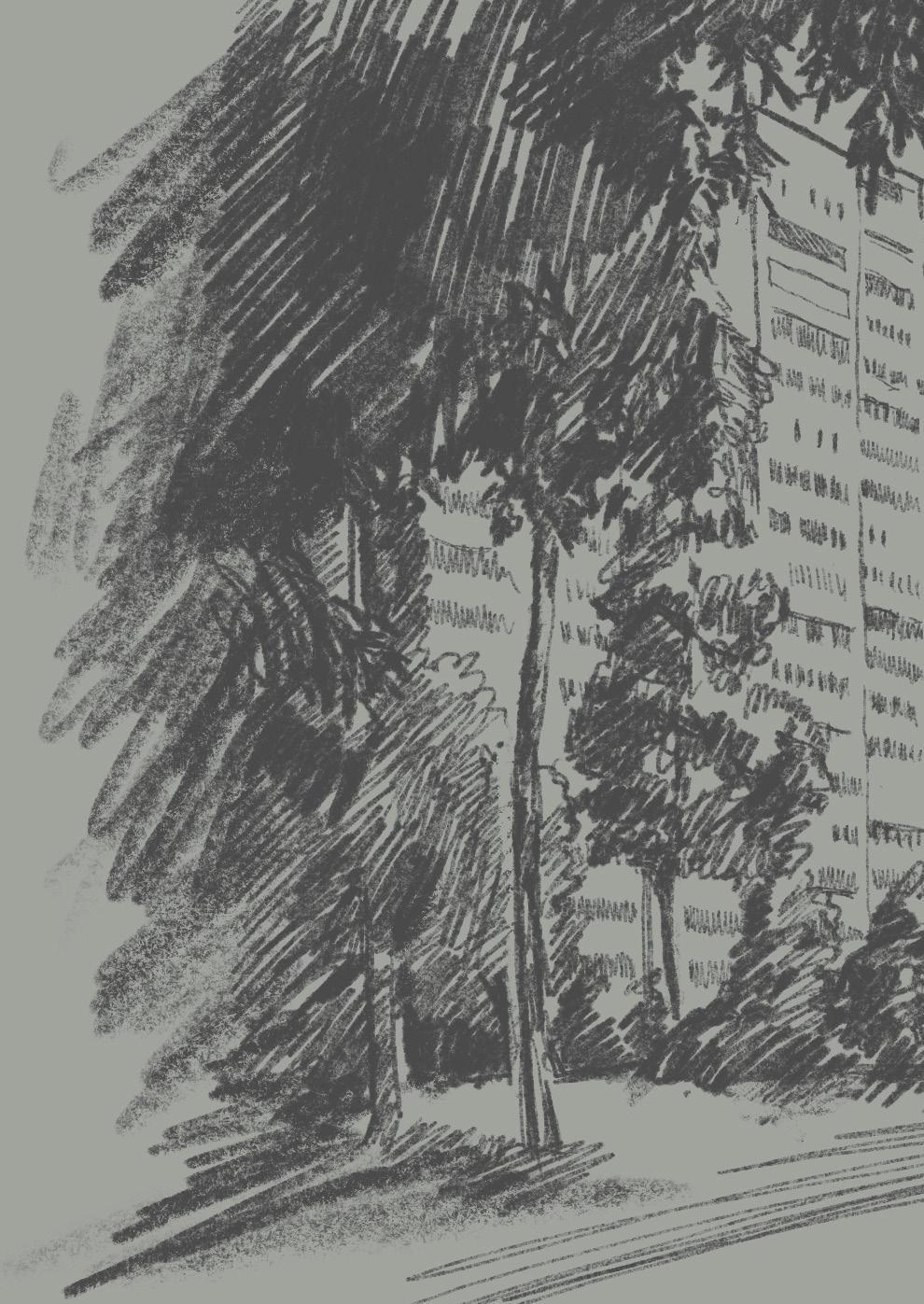

To truly understand the atmosphere and spatial dynamics of Moscow’s outskirt districts, my research began with on-site exploration. I visited Northern Izmailovo, Losinoostrovsky, and Southern Chertanovo—three distinct districts representing different typologies and histories.

Stepping out of the metro during my first visit, I found myself in a disorienting environment. Despite preparing maps and routes in advance, the oversized flyover rising to the third floor of surrounding buildings and a mass of people waiting to cross the road immediately erased any sense of orientation. In Northern Izmailovo, the environment felt like a scene from a Soviet-era film: compact five-story buildings with pale yellow façades, surrounded by a calm, intimate public space. Small but telling details—like ornamental cabbage pushing through the snow, a handmade chicken coop, or improvised bird feeders by the entrances—suggested a quiet attachment to place and a degree of informality in how space is used and shared.

In contrast, Losinoostrovsky felt more familiar—reminiscent of my own childhood neighborhood. The presence of Yauza Park offered a strong recreational backbone to the area. Even on a weekday in winter, the park was full of locals. Yet within the residential fabric itself, little reflected any particular identity; the space appeared highly utilitarian. A large Asian grocery complex bordering the main road indicated either proximity to industrial zones or low-rent availability. Nearby, I encountered a partially evacuated residential block— its lifeless atmosphere and visible protest slogans on surrounding walls underscored the social tension of impending redevelopment.

Southern Chertanovo revealed a different texture. I arrived around 13:00 and was met with a long queue at a bus stop, hinting at high dependency on public transport during peak hours. Although similar in building height to the previous districts, here I noticed small gestures of personalization: spontaneous gardens near building edges, hand-decorated entrances to basements, and ornamented yards that softened the standardized mass housing fabric. Yet the streets were nearly empty, save for elderly residents quietly sunbathing on benches. After walking for over a kilometer in search of a warm café without success, it became clear that the lack of accessible amenities discourages public life. The built environment, while residential, lacks the programmatic support to be socially vibrant.

This fieldwork experience revealed a critical truth: urban quality is not always visible in data. While quantitative indicators are essential, they often miss the micro-scale realities that shape daily life. The intangible social dynamics— routine behaviors, personal gestures, spatial memory—are vital components of neighborhood identity and resilience.

The current government-led redevelopment strategy proposes large-scale demolition of outdated housing and reconstruction with new, denser housing blocks. While this may bring technical upgrades and new infrastructure, the social consequences are often under-addressed. Forced relocation separates residents from their social networks and everyday routines. For older generations, such disruptions may result in increased vulnerability and loss of agency, as they are assigned new environments without the ability to choose them.

New developments, while promising mixed-use functionality, often fail to deliver sufficient amenities relative to the housing volume. As a result, residents in these newly built areas may still rely on neighboring districts, sustaining pressure on overloaded infrastructure. Moreover, without rethinking the spatial distribution of workplaces and services, existing transportation dependence on the city center remains unchanged.

From an urban design standpoint, this top-down transformation risks amplifying existing key challenges— functional imbalance, weak local identity, and social disconnect—rather than resolving them. The next section outlines how these challenges could be intensified by the current approach.

If the district undergoes redevelopment according to the government’s plan, several key spatial and social challenges are likely to intensify:

Privat–Public Transition: New highdensity developments often lack clear thresholds between private and public space, reducing informal resident control and weakening local community presence.

Functional Imbalance: Although mixed-use elements are formally included in plans, the ratio of residential to commercial and social functions remains low, reinforcing monofunctionality.

Financial Dependence: Limited opportunities for local entrepreneurship or informal economies within the new structures may increase residents’ economic reliance on other areas.

Identity Loss: Uniform redevelopment erases neighborhood-specific spatial and cultural elements, replacing them with standard solutions disconnected from local narratives.

Leisure Dependence: A lack of accessible and varied public spaces may push residents to seek leisure elsewhere, sustaining reliance on distant amenities.

Transportation Dependence: Without redistributing jobs and services across the city, new developments will continue to generate commuting flows toward the center, sustaining infrastructural pressure.

Overall, the current redevelopment model risks increasing density without improving self-sufficiency, further disconnecting residents from their surroundings.

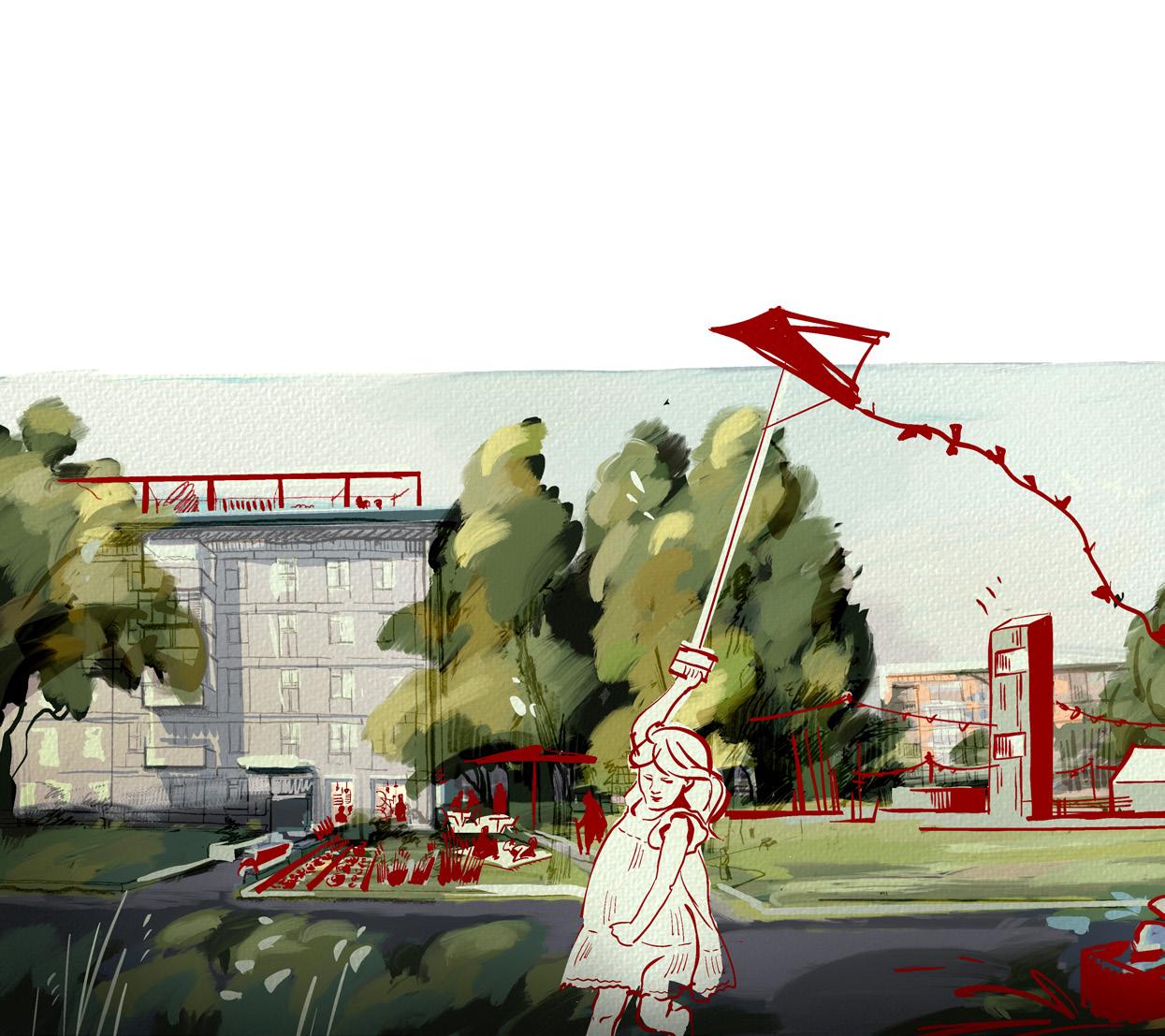

As a designer, my role is in revealing and strengthening the existing social potential of neighbourhoods through sensitive, context-driven interventions.

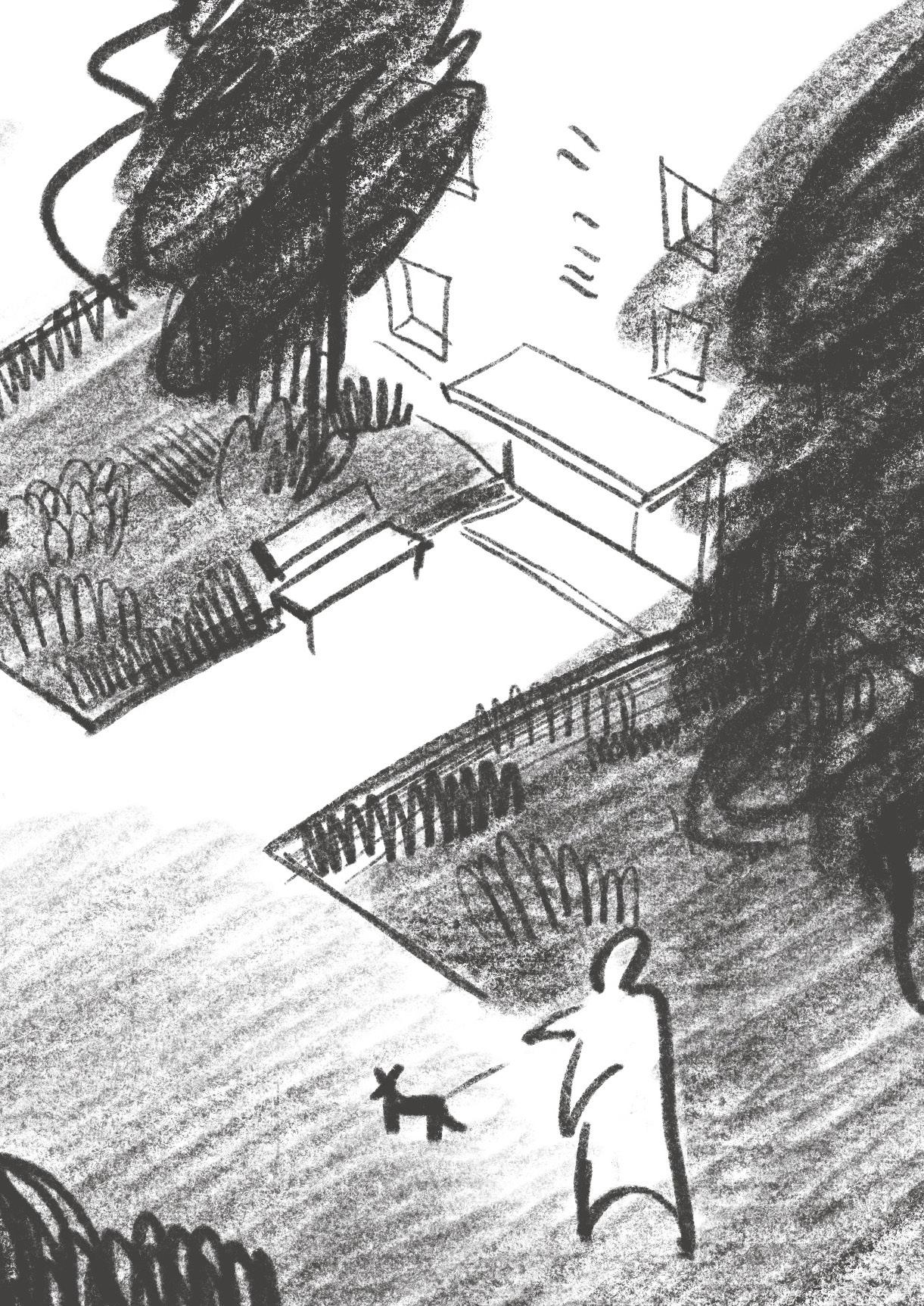

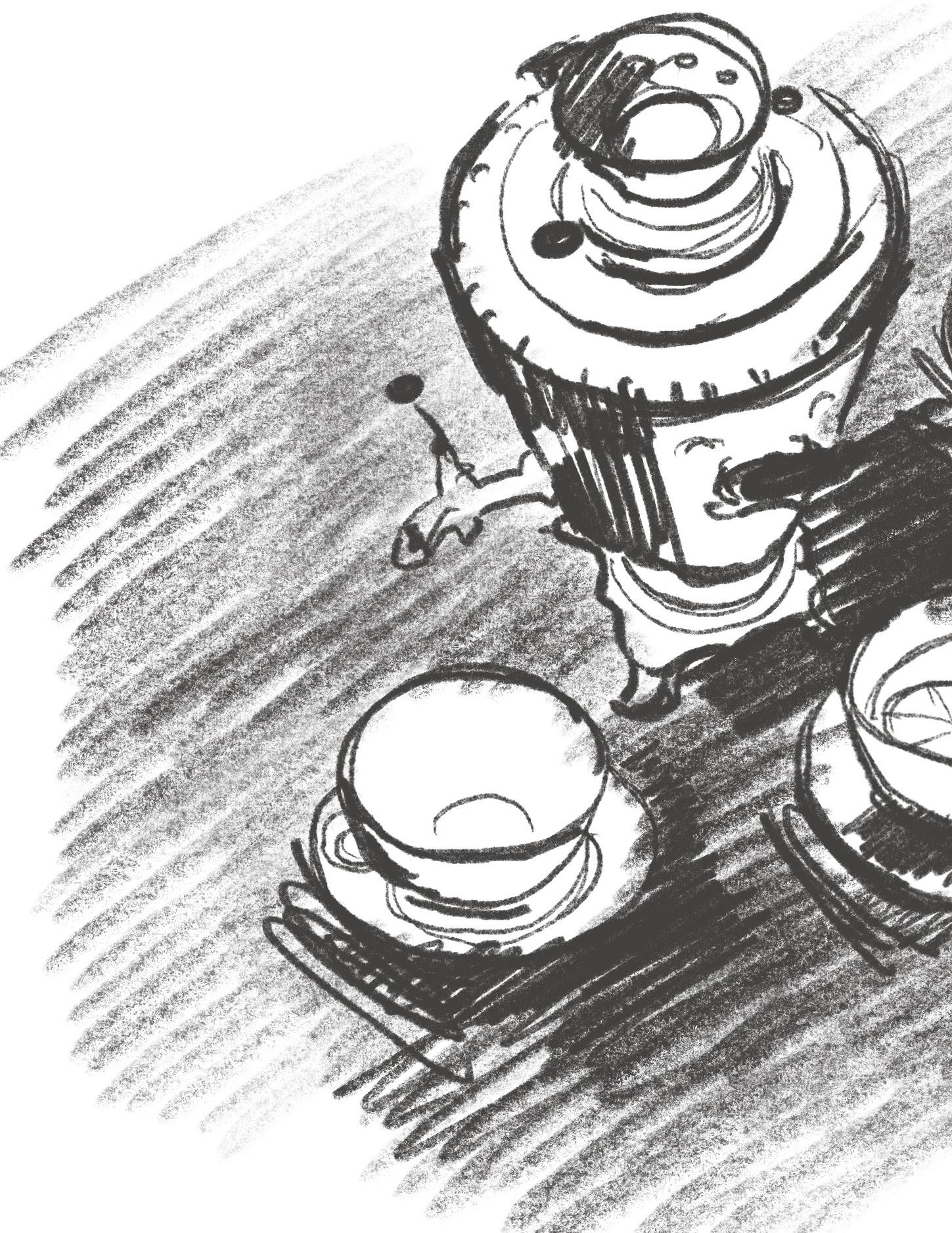

Social interactions and everyday traces of life are the foundation of my design approach. I am deeply inspired by the informal ways people inhabit their neighbourhoods — the benches they create out of old furniture, the plants they grow around entrances, the quiet moments of conversation, the way children carve out playful paths across courtyards. These small, often unnoticed gestures carry a powerful meaning. They reflect care, presence, and belonging.

In my work, I strive to honour and amplify these micro-realities. I believe design should not overwrite what already exists, but instead, make it visible, strengthen

it, and offer space for it to flourish. I see public space not as a fixed product but as a living framework — one that evolves with its users and embraces imperfection as part of its beauty.

By treating these subtle, human-made qualities as sources of knowledge rather than obstacles, I create spaces that feel emotionally grounded, familiar, and resilient. I design not just for people, but with them in mind — valuing the stories, routines, and social bonds that give each place its soul.

The outskirts of Moscow are often seen as problematic due to their residential density. But I see this concentration of people as an opportunity. While the city centre holds 70% of offices, culture, and tourism and only 30% of residents, the outskirts reverse this logic — with 75% living and just 25% public and commercial functions.

This imbalance leads to underused potential. A high number of residents means a wealth of energy, soft qualities, and social power already present in the neighbourhood. Instead of relocating people, we should build on this resource and support local life where it already exists.

70% Office / culture / tourism 30 % Living

25% Office / commerce / Public functions 75 % Living

Through first-hand interviews with residents of selected districts, this chapter reveals everyday experiences, emotional attachments, and the human-scale realities often overlooked in official planning processes.

“My neighbourhood is me, it’s an integral part of me and who I am.”

Q: What do you think about the neighbourhood today? What’s missing or bothering you?

A:

“I’ve been living here since I was a child — more than 60 years now. You get used to a place like this. But lately, things have changed. The buses, they don’t go like they used to. Sometimes I just can’t get to the doctor on time.

And the snow — no one clears it properly anymore. I walk with a cane, so I see every bump, every pile. They keep saying the renovation will fix things, but they’ve torn down two buildings and just left holes in the ground. You can’t build community in a construction fence.

Still, I love it here. I know every corner, every neighbour. I don’t want to leave.

You know what I would love? If someone took care of the entrance again. Like it was ours. A few plants, maybe a bench. Something simple that shows this place still matters. Because when people care, everything starts to feel different.”

Ответ: “Я живу здесь с детства — больше 60 лет. Привыкаешь к месту. Но в последнее время всё стало другим. Автобусы ходят плохо, не вовремя. Иногда даже до врача не могу добраться.

А снег… его как будто больше никто не чистит. Я хожу с тростью, поэтому замечаю каждую ямку. Говорят, реновация всё решит, но снесли два дома и оставили яму с забором. Теперь там куча мусора и

Age: 65

Profession: Retired doctor

Status: Lives alone in Northern Izmaylovo

Location of meeting: At the bus stop on 15th Parkovaya Street

Interview mood: Expressive, alert, critical but emotionally attached to place

Notable trait: Strong sense of belonging and long memory of place; informal community leader

“This city runs like a machine — what is my place in there?”

Name: Roman Age: 50

Profession: Shop assistant at a local Vkusvill store

Residence: Lives further out, near Chertanovo

Location of meeting: Storefront in Chertanovo (Vkusvill)

Interview mood: Calm but critical; observant and socially aware

Notable trait: Pragmatic thinker with a deep awareness of systemic imbalance

Q: You live on the outskirts and work in the city — how do you feel about this dynamic?

A:

“This city isn’t a city anymore. It’s a factory. People come in, work their shift, and leave. I see it in my shop every day — tired faces, rushing in and out, no time to rest, let alone to live.

Sure, the government builds things — theaters, cultural centers. But who are they really for? I have one in my area. You know how often I go? Maybe once a year. Tickets, transport, dinner — it’s not made for people like me.

And when they build houses, they forget everything else. No schools, no kindergartens. People move, but their kids still go to school two districts away. It’s all upside down.

If you ask me, real change doesn’t start with concrete. It starts with asking what people actually need.”

чувствуете себя в этой системе?

Ответ: “Это уже не город. Это фабрика. Люди

приходят, отрабатывают смену — и уходят.

Я это вижу каждый день в магазине: лица

уставшие, никто не задерживается, никто здесь по-настоящему не живёт.

Да, что-то строят. Театры, культурные центры. Но они не для нас. У меня в районе есть театр

“Retirement is a time to enjoy life, and I want to spend it with my family and close friends.”

Q: What do you like or miss in your neighbourhood?

A:

“You know what I miss? The kind of courtyard where people would gather. Now, there’s nowhere to meet unless you walk 20 minutes to the park. And not all of us can.

The sidewalks are icy. The cars come out of nowhere. I’ve slipped twice already this year.

There’s a center — it’s nice. But it only works if you make it there. What we really need is places nearby, with benches, a small roof maybe, and people.

Even a place to stretch in the morning would be wonderful. We’re not just sitting at home anymore. We want to live.”

чтобы можно было собраться, поговорить. А сейчас всё далеко

могут. Тротуары скользкие, машины выскакивают внезапно. Я дважды уже падала.

Центр есть, хороший, но до него надо дойти. Нам нужно что-то поближе. Скамейка, навес, люди рядом.

Я бы и поутру потянулась где-то. Мы не просто сидим дома. Мы жить хо

Name: Albina

Age: 70

Profession: Former textile factory worker (retired)

Location of meeting: Entrance to Longevity Center

Mood: Gentle but assertive

Notable trait: Honest, resilient, values community proximity

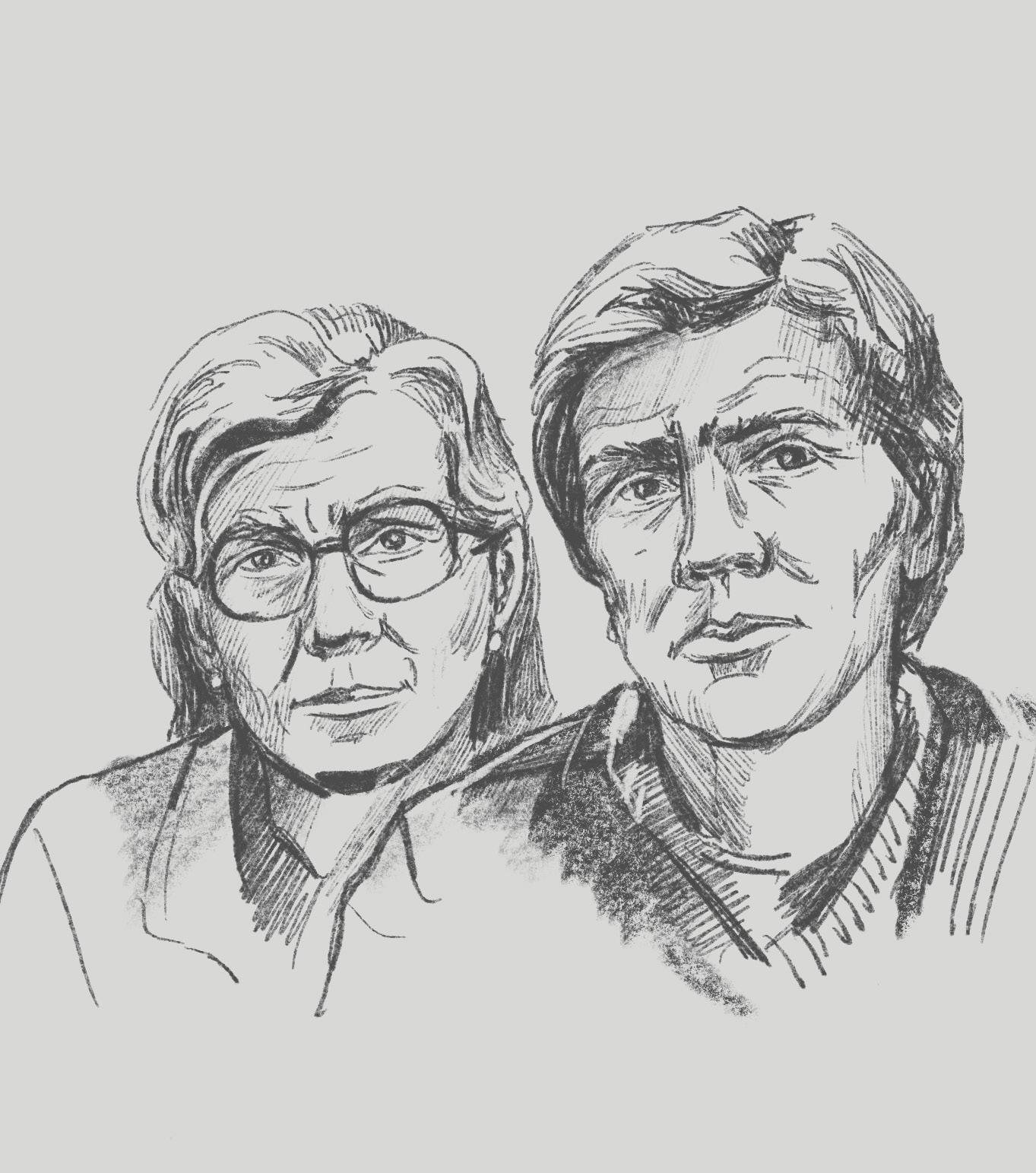

Olga and Sergey

“An active life improves life, you need to focus on this when developing territories.”

Names: Olga (social worker), Sergey (physiotherapist)

Ages: 46 & 47

Profession: Staff at Moscow Longevity Program

Residence: Northern Izmaylovo

Location of meeting: Reception of Longevity Center

Family: One adult daughter (IT specialist)

Interview mood: Caring, informed, community-oriented

Notable trait: Understand needs of elderly and spatial gaps for mobility

Q: What are your thoughts about the neighbourhood and how it supports daily life, especially for older residents?

A:

Olga:

“It’s a strange mix. The people are lovely — many have known each other for years. But the space doesn’t help us stay connected.

Sergey:

Most of our work is with the elderly. They’re active, they want to move, meet, learn — but where? There are few benches, almost no safe walking paths, and the lighting at night is just bad.

Olga:

We’ve seen what even a small space can do — when it’s well-lit, cared for, and has something to sit on. It brings people together without even trying.

Sergey:

The government invests in buildings. But if they invested in comfort and movement, the health budget would shrink too.”

людям?

Ольга: “Люди здесь хорошие, многие знают

друг друга годами. Но пространство не помогает сохранять эти связи.

Сергей: Мы работаем с пожилыми. Они хотят двигаться, общаться, учиться — но где? Скамеек мало, тропинок почти нет, а вечером темно.

Ольга: Мы видели, что может сделать даже

“There’s nothing interesting here.”

Name: Svetlana

Age: 26

Profession: Administrative assistant & certified fitness coach

Family: Lives near parents

Mood: Thoughtful, quiet, seeking balance

Q: How do you feel about living in your neighbourhood? What’s missing?

A:

“I grew up around here, and I still live close to my parents. I don’t mind the calm, but the area feels completely hollow. There’s nothing happening — no events, no cafés, no art, no outdoor markets. There’s nowhere to go unless you leave the district.

After work, I don’t need much — just a place where I could meet a friend, hear some live music, sit with a book in a cozy spot. But it just doesn’t exist here. Every weekend I end up in the centre because that’s where the life is. And it’s exhausting — you spend more time commuting than enjoying anything.

This neighbourhood feels like it’s only made for sleeping. Not for being. Not for discovering. And that’s sad, because there are so many people living here. So much potential.

I’d love to see something new — small public events, street food, performances, maybe pop-up exhibitions. Just something spontaneous and vibrant, not behind glass or behind fences.” Вопрос:

Чего не хватает?

Ответ: “Я выросла в этих местах, живу рядом с родителями. В целом мне нравится тишина, но сам район пустой. Тут просто ничего не происходит. Нет событий, нет

кафе, нету ярмарок, выставок или мест, где можно просто посидеть и вдохнуть жизнь.

После работы я не жду многого — просто

хочется иметь пространство, где можно встретиться с подругой, послушать музыку, почитать книжку на улице. Но

здесь этого нет. Каждый выходной я уезжаю в центр — потому что только там есть ощущения города. И это утомительно — на дорогу уходит больше времени, чем на сам отдых. Этот район

“I’m not sure that demolition is the solution.”

Q: What do you think about the renovation program and changes happening in your neighbourhood?

A:

“I know they say the new buildings are progress, and maybe for some they are. But when I look at them, so tall and so close, I’m not sure it’s made for people like me.

I live in a five-story building. It’s not perfect, but it hsve a “live”. The courtyard used to feel open. Now there’s a wall of glass and concrete rising next door. And who knows if the new people will care about this place?

They say we’ll all get new apartments one day. But I’m not convinced that means a better life. It just feels like something big is coming too close.

I’d rather see my building repaired, made more livable — not just replaced. Because once it’s gone, it’s not just bricks. It’s everything built around it.”

Вопрос:

район меняется?

Ответ: “Говорят, что новые дома — это прогресс. Может,

высотки рядом с нашей пятиэтажкой — не понимаю, для кого это строится.

Name: Oleg

Age: 55

Profession: Mechanic for municipal road equipment

Status: Married, father of two students

Residence: Northern Izmaylovo, 5-story apartment block

Interview mood: Reflective, practical, reserved but thoughtful

Notable trait: Thinks spatially, values small shared functions

Interview context: Met him walking his dog near the building courtyard

A spatial and sociological examination of the neighborhoods under study. This chapter identifies structural and social patterns across the urban fabric, including poverty, transport access, monofunctionality, and demographic trends.

To identify the core urban challenges, I began by thoroughly analysing interviews and resident comments collected onsite. This method allowed me to trace patterns and interconnections between lived experiences and the spatial context. Rather than relying solely on statistical data, this grounded, human-centred approach revealed nuanced challenges that are often overlooked. It ensures that the analysis reflects the real concerns and priorities of the people who live in these neighbourhoods.

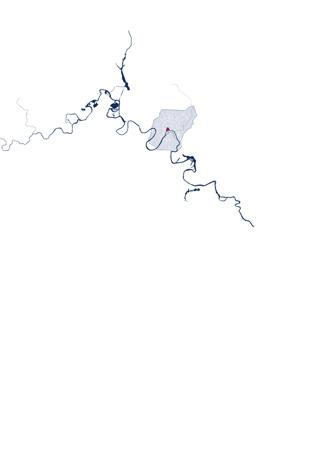

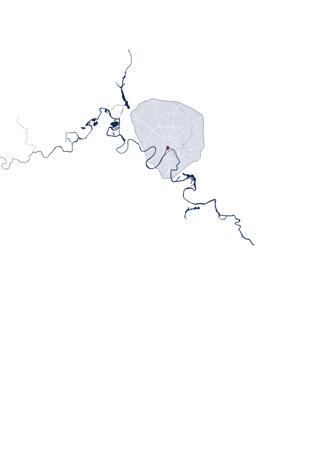

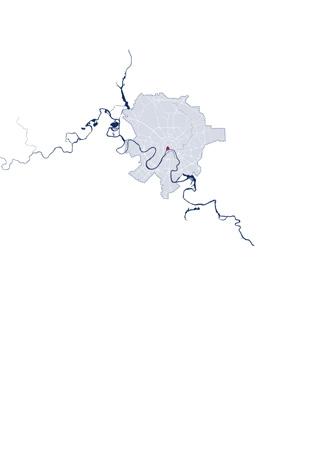

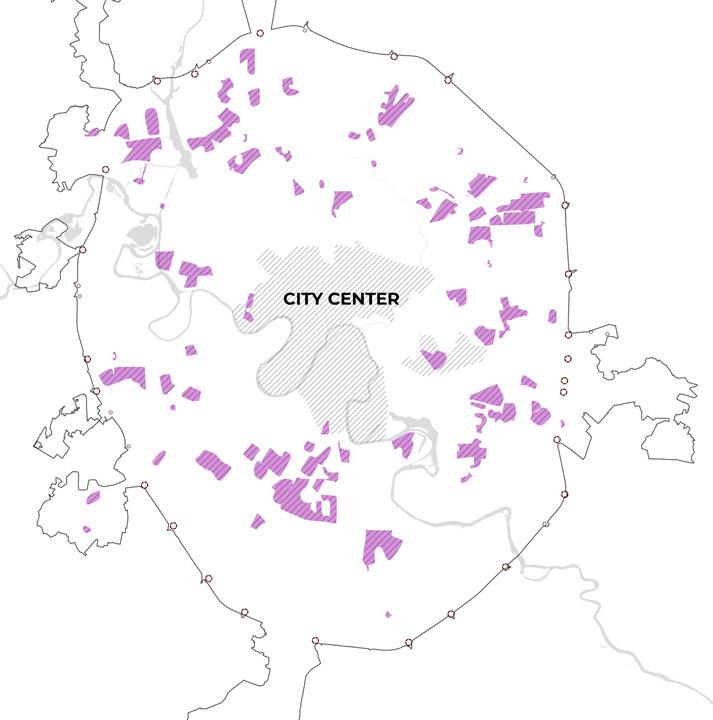

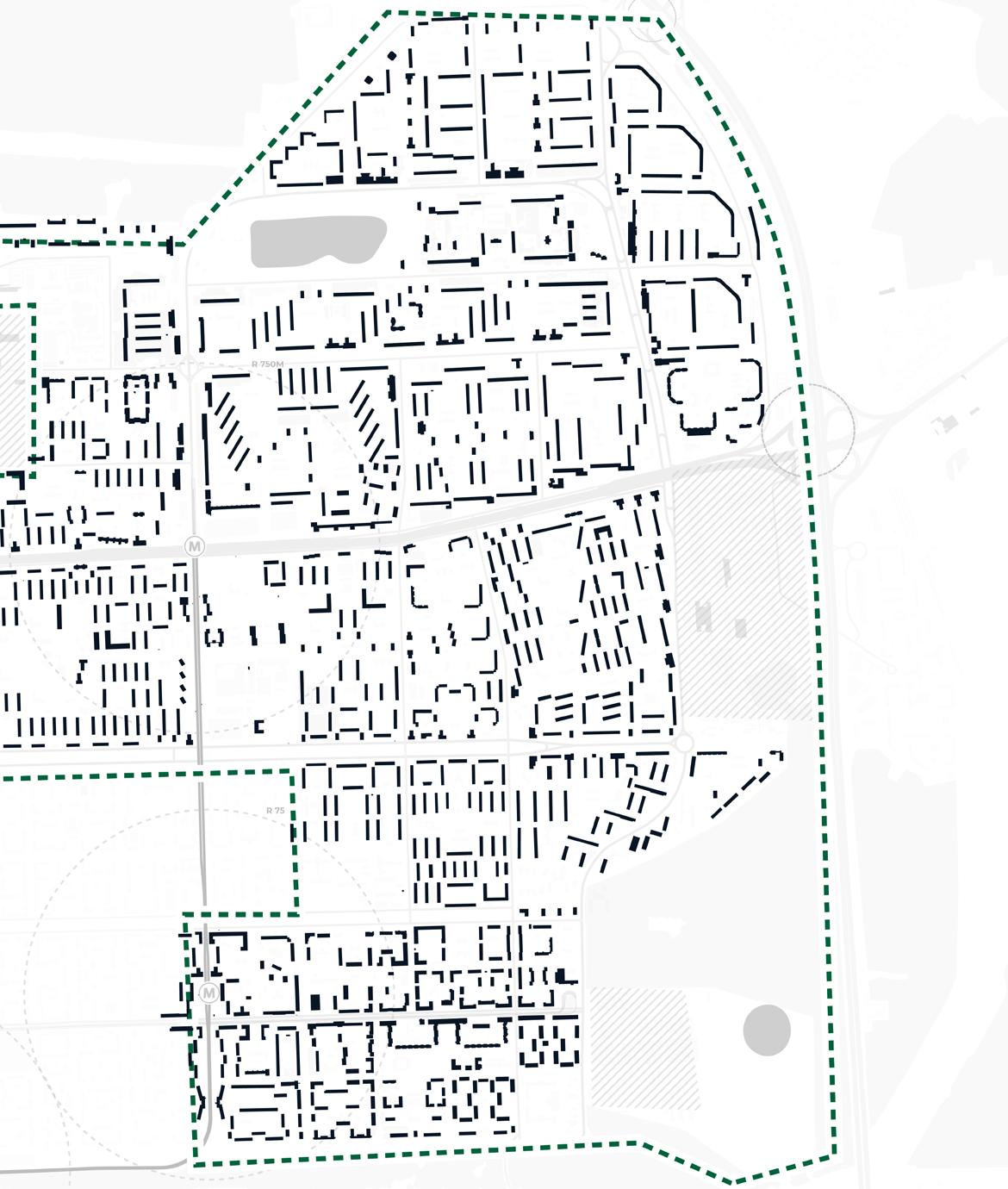

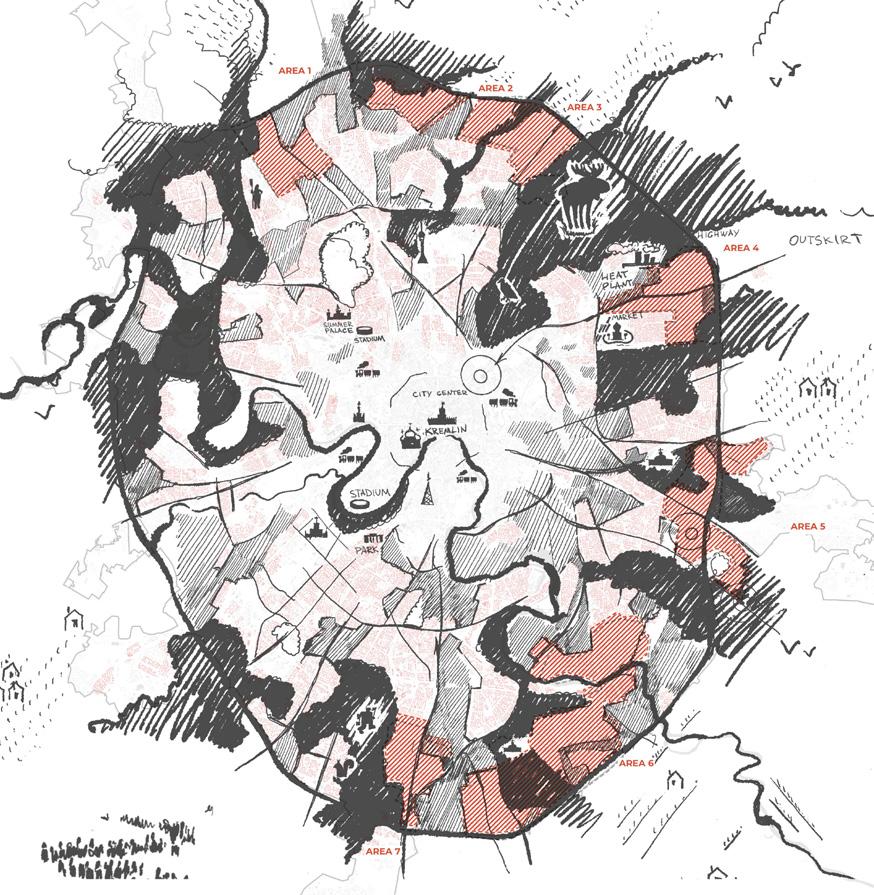

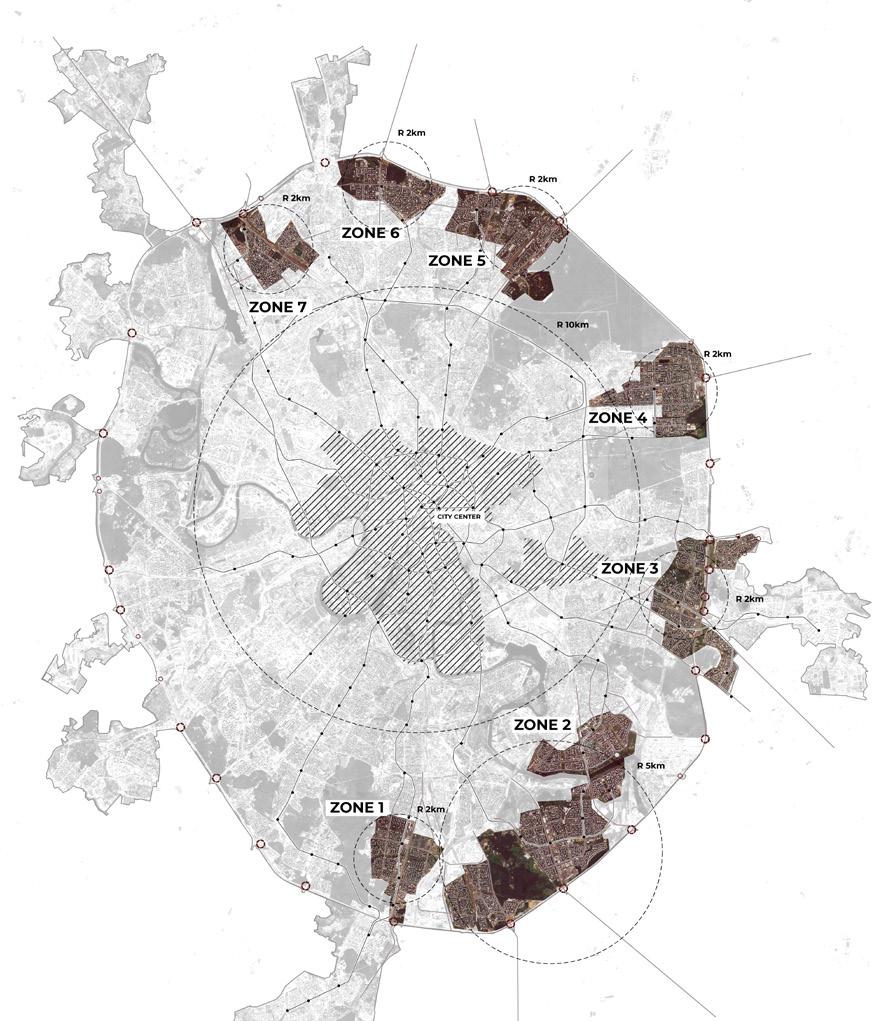

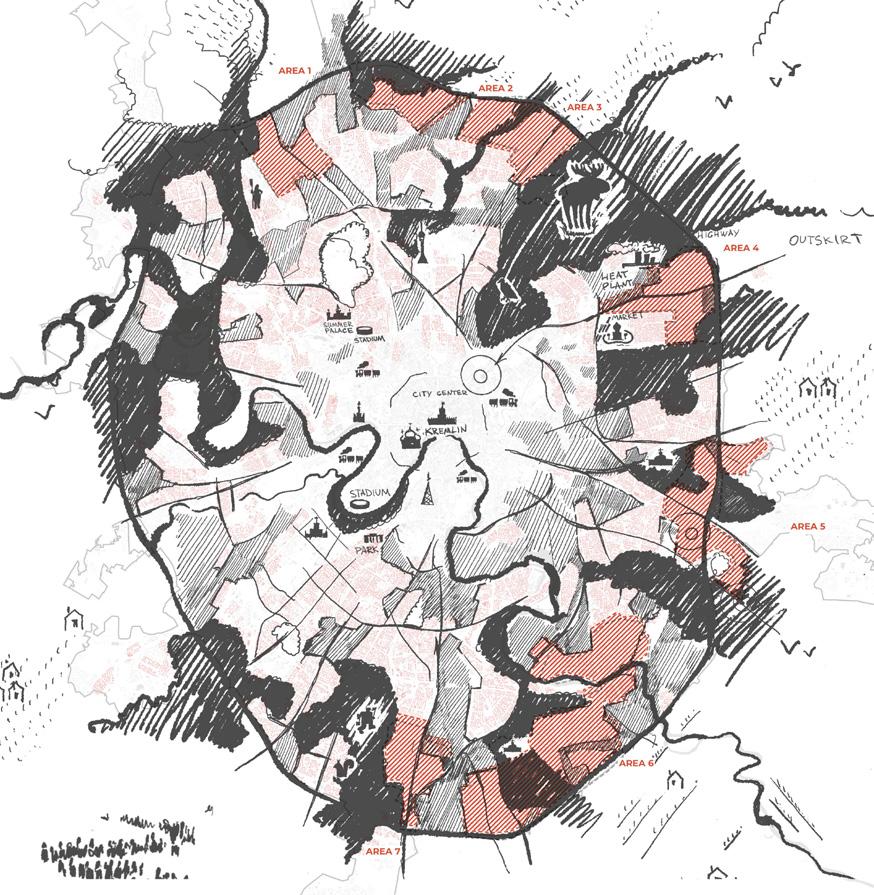

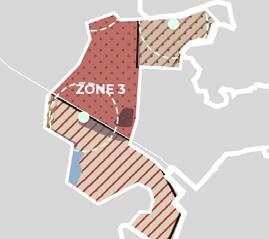

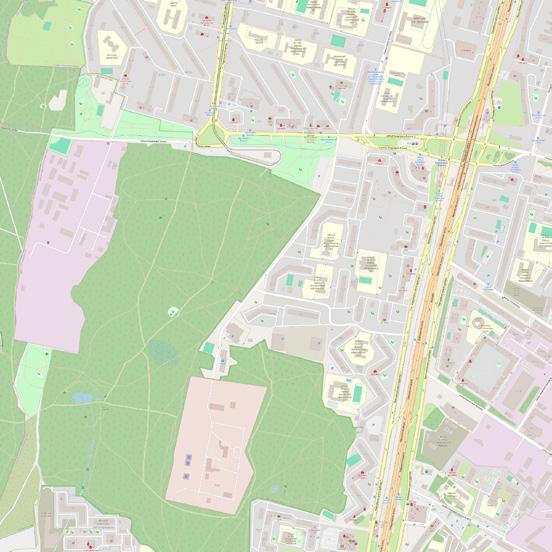

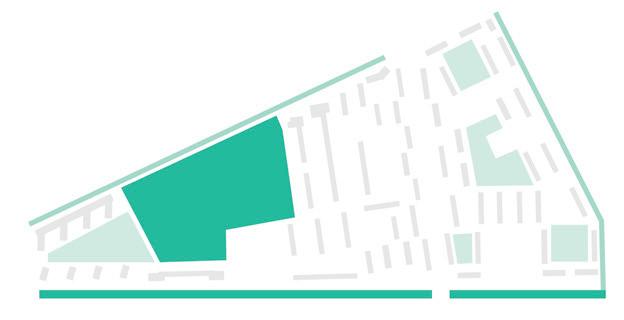

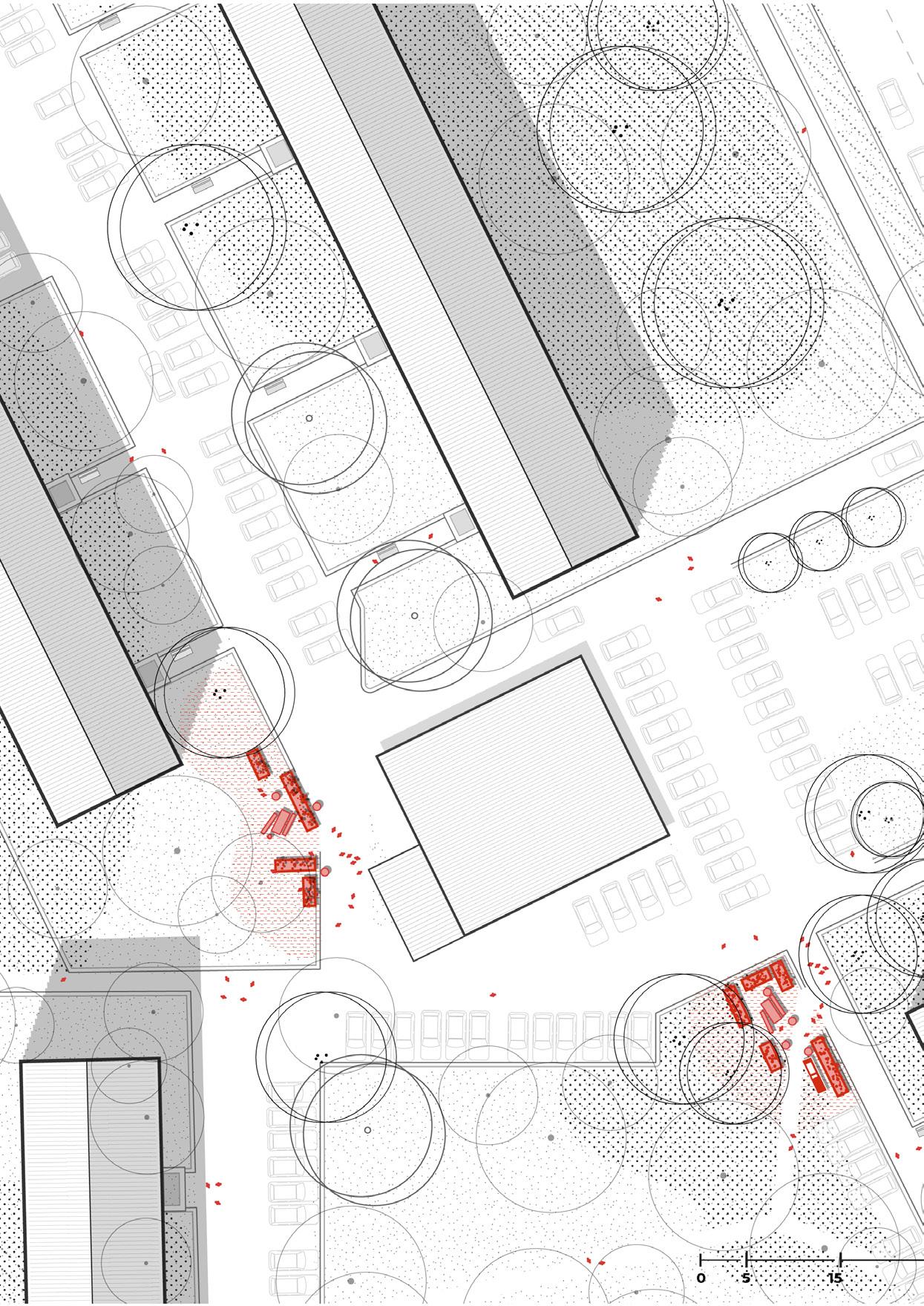

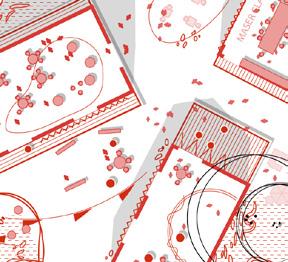

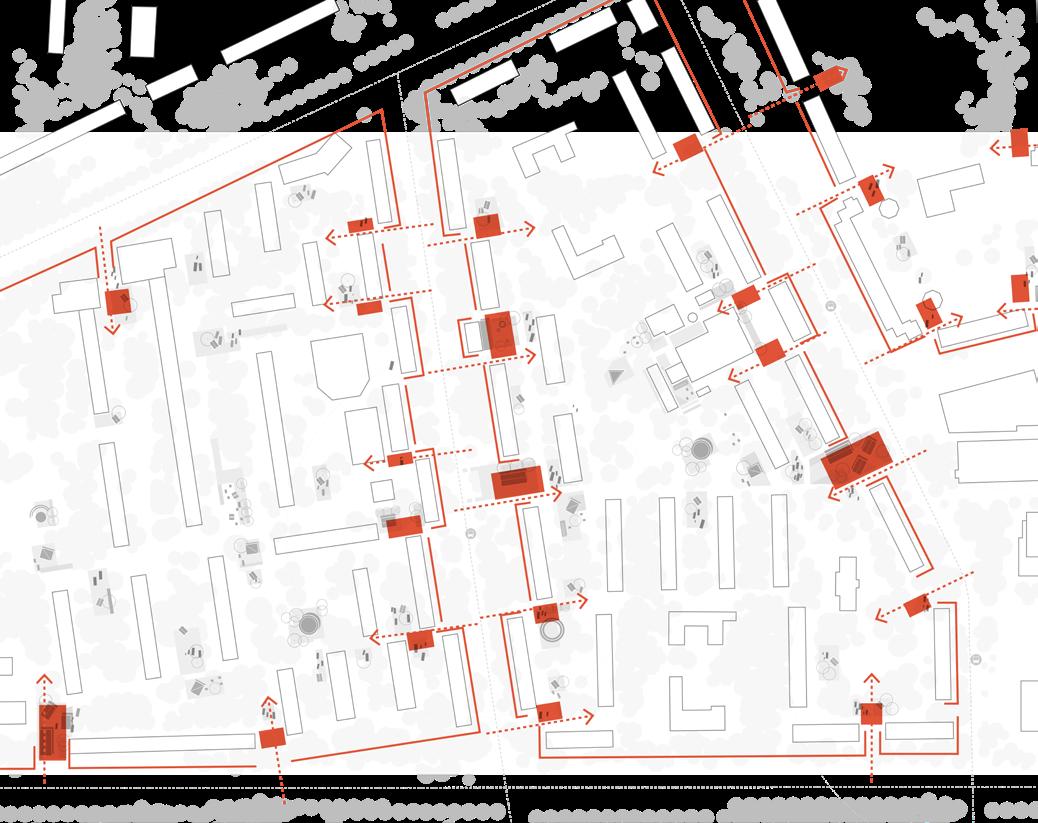

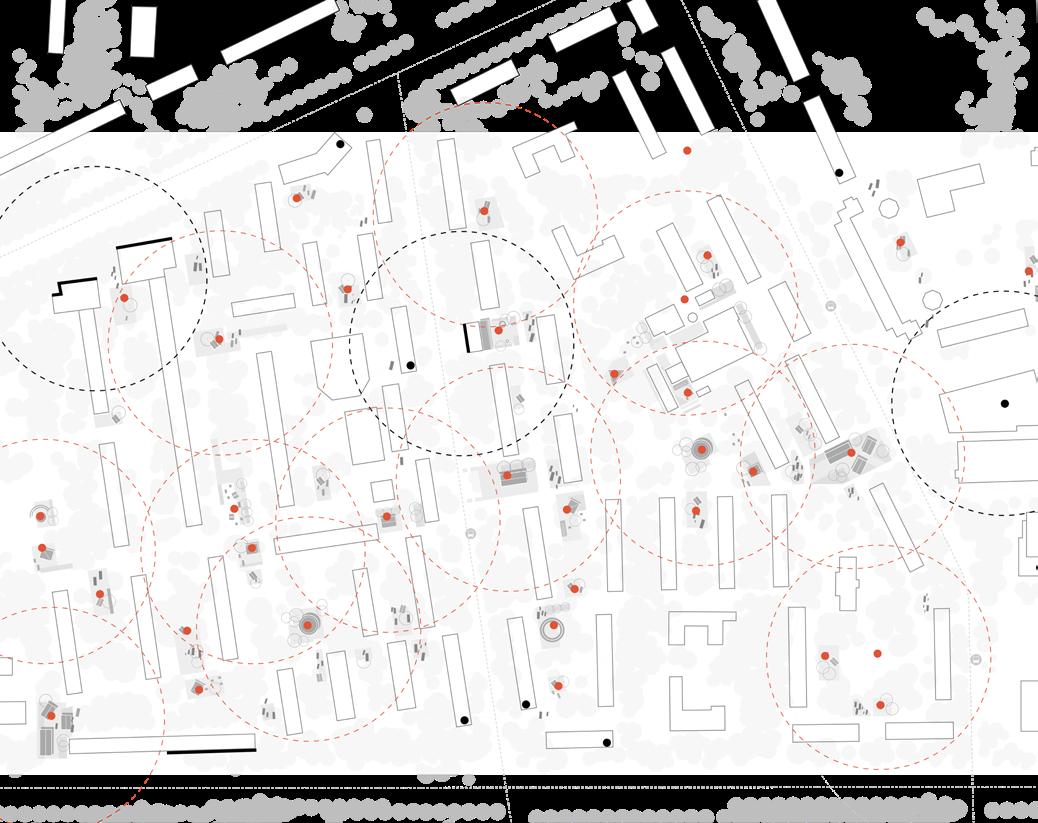

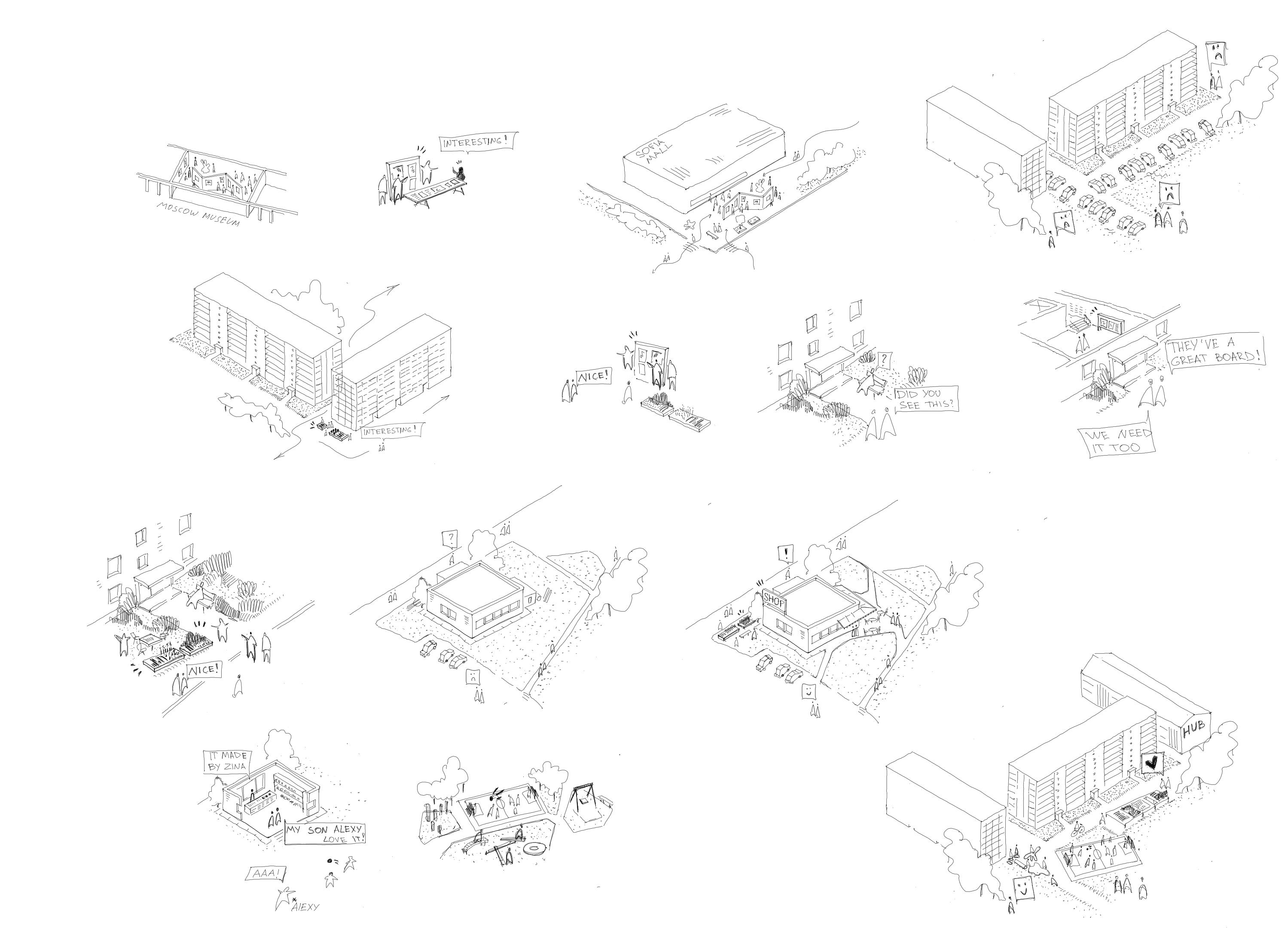

Through this analytical process, I developed a series of spatial maps that revealed how specific urban characteristics directly affect the everyday lives of residents. These maps helped me identify the most vulnerable areas across the city—places where multiple challenges overlap. Out of the seven zones I studied, I focused on those with the

highest concentration of social and spatial pressure. From there, I further subdivided these areas to zoom in on the most affected neighbourhoods, enabling a deeper, spatially grounded understanding of where design interventions are most needed.

Poverty level + level of education.

Areas close to the industry in highlighted and overlaps with map 1

Poverty level Cheapest housing

Cheapest housing - low quality environment East, South, and North outskirts. Far-reachable areas are the worst.

Skaterred around the industry and occupied the cheapest place

N.b. has the most residential functions (more than 70%) and travels more than 40 m to c.c.

East, South, and North

Unhealthy areas

Link to main highways and industry + intensely build residential intensively

Surrounded by c.c from right to south + blocking the outskirts, located along the river Segmentation in the north

Most residential and dense areas + most busy metro lines

East, South, and North

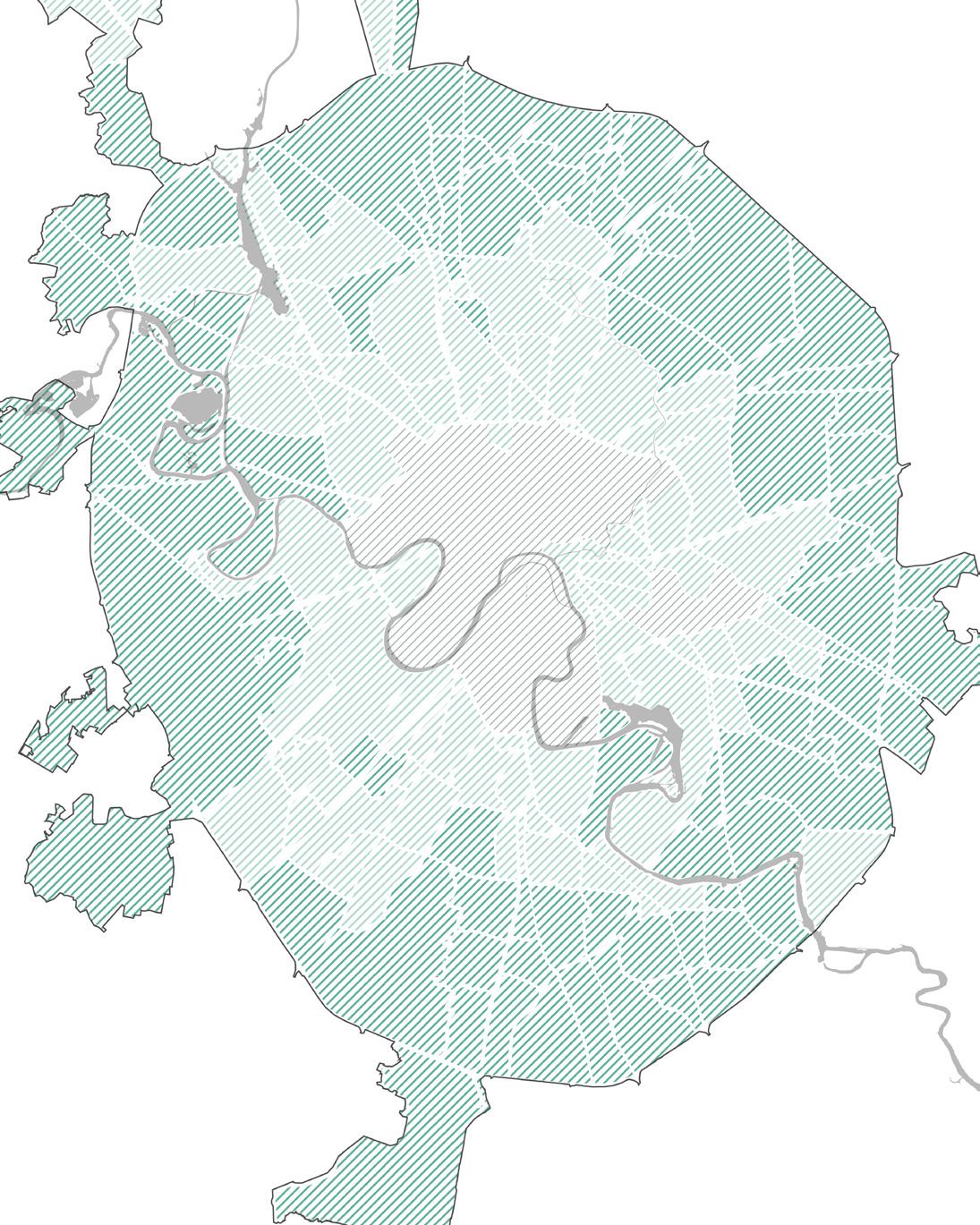

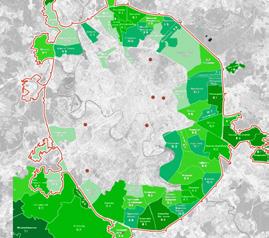

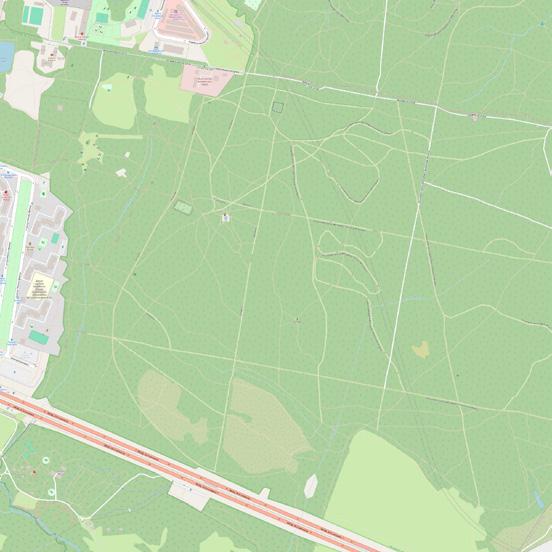

This soft map overlays Moscow’s green areas and central landmarks with the seven zones identified in the initial stage of research. It highlights the spatial inequality between the central core and the periphery— emphasising disparities in urban quality and accessibility.

Most of the analysed areas are located along the city’s outer edge, often bordered on one or two sides by vast natural landscapes. Through a synthesis of interview-based insights and urban spatial analysis, the map

reveals how these districts face intersecting pressures: high poverty rates, an aging population, affordable yet outdated housing stock, long commutes, high residential density, and predominantly monofunctional land use.

Each of the seven zones reflects a distinct mix of these challenges, yet they all share a fundamental structural imbalance—insufficient functional diversity, underdeveloped public infrastructure, and a strong dependence on the city centre.

The fewest challenges are present in this area, but it is strongly affected by the railway line running through it.

Multiple challenges exist in the area, though no significant overlaps between them are observed.

Several challenges are present, but there are no major overlaps between them.

The area shows a mosaic pattern of challenges, yet without strong overlaps between them.

The central zone has the highest concentration of overlapping challenges and is additionally impacted by industrial activity from the south.

The southern part of this area shows the greatest overlap of all research aspects.

The central part of this area demonstrates the most significant overlaps and is heavily affected by nearby industry in the northwest.

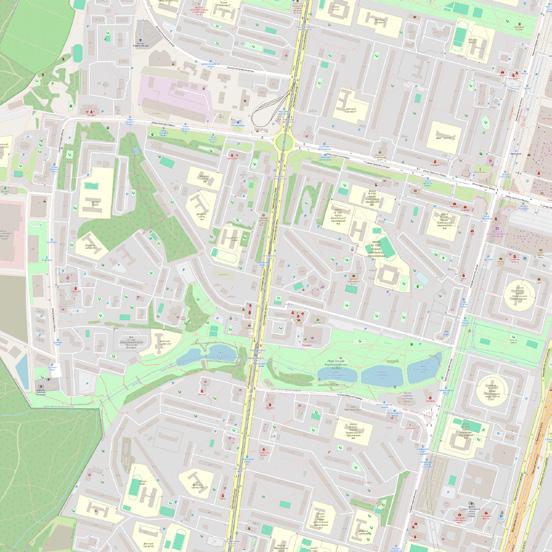

Here, the most vulnerable and structurally complex districts are identified. Three key areas are selected for further development based on the density of challenges and their spatial relationships within the city.

Area size 1465 ha

Population 327 000

Dencity 223 people/ha

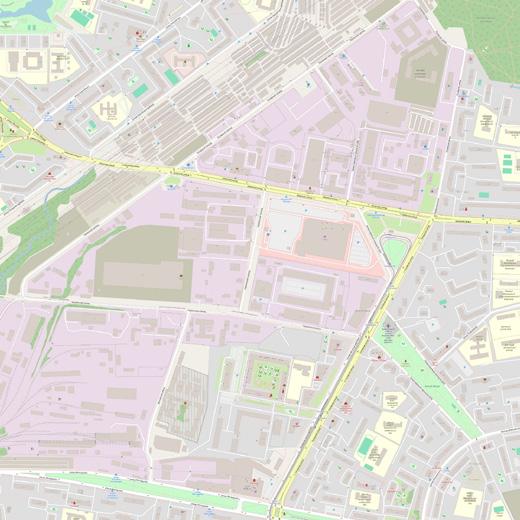

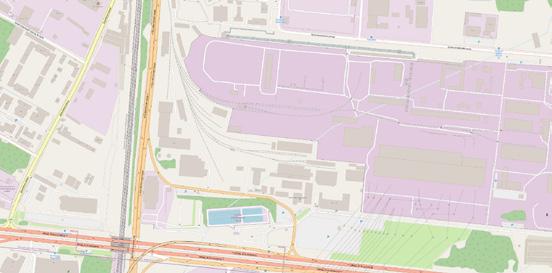

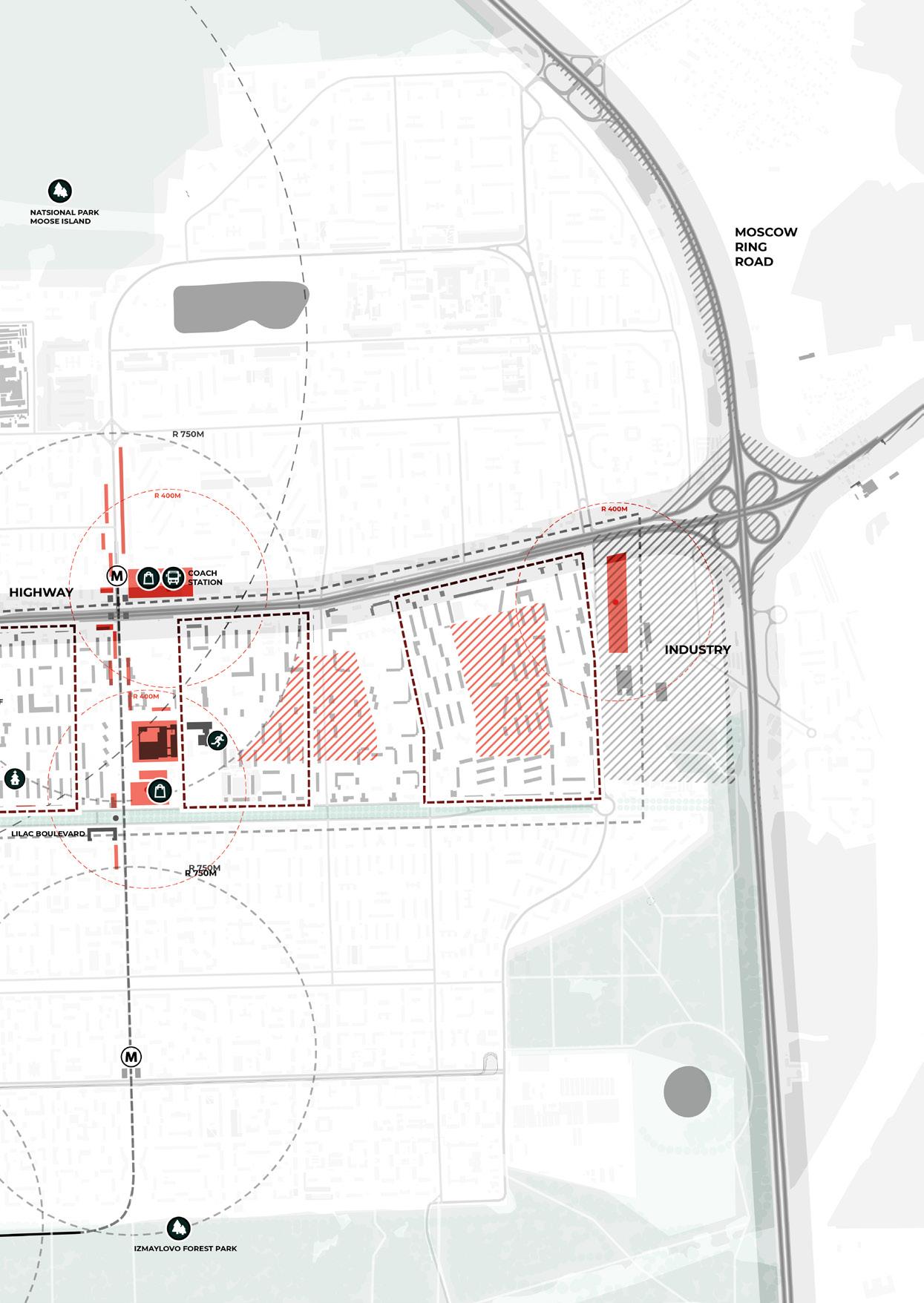

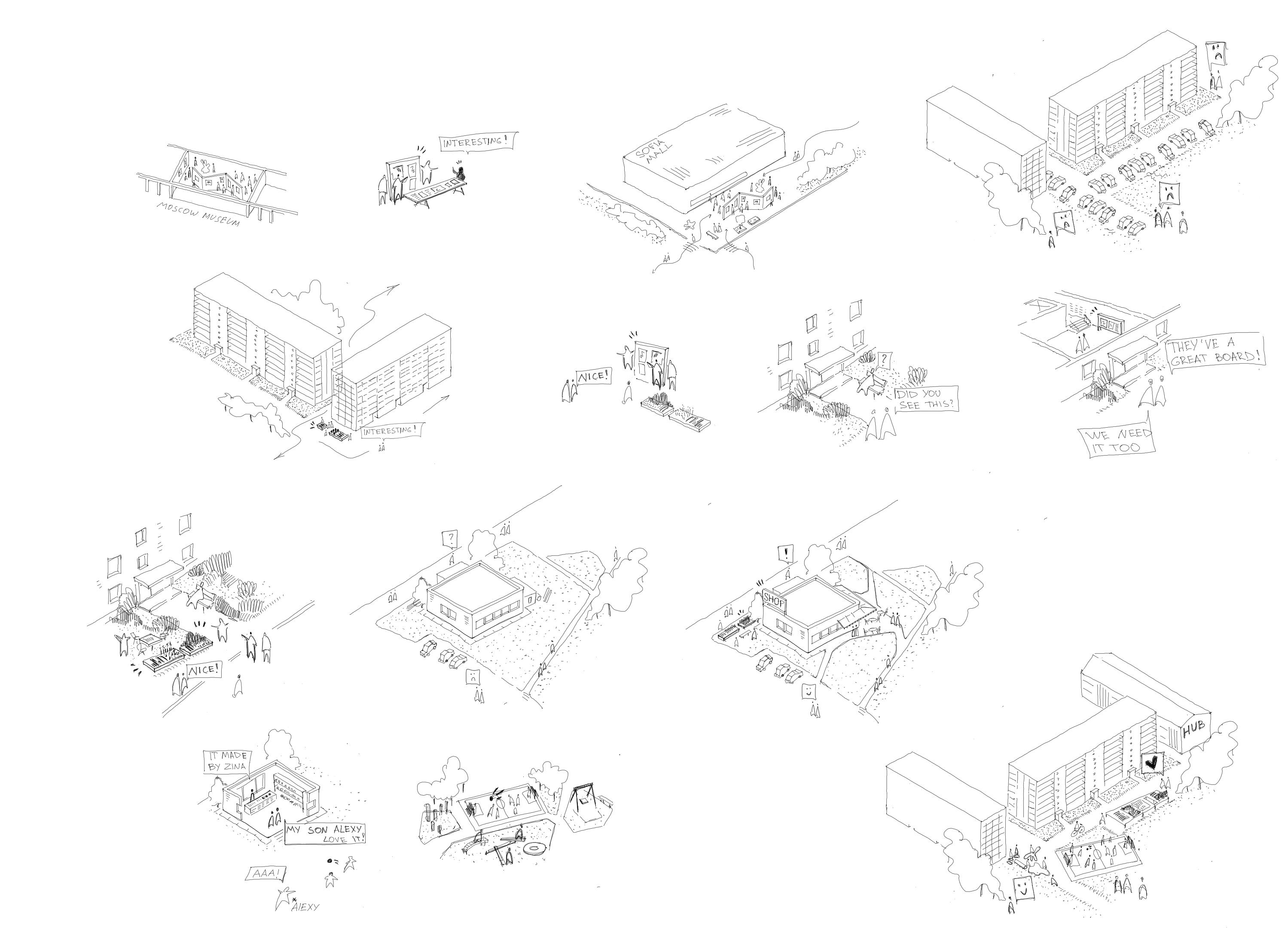

Northern and Eastern Izmaylovo and Golyanovo are peripheral residential districts in Eastern Moscow, primarily built in the 1950s–1970s during the Soviet mass housing expansion. Their urban structure is dominated by open block layouts and 5–9 storey panel slab apartment buildings, typical of the era. Northern Izmaylovo stands out as the most challenged area, with the poorest access to entertainment and social infrastructure, limited active public life. Public mobility is supported by two metro stations, but large parts of the area remain disconnected in terms

of daily services and cultural activity. Golyanovo also faces infrastructural deficits, while South Izmaylovo, closer to the metro and amenities, shows better access to bars, sports clubs, and local events. Local hubs include Shchyolkovo Mall and Pervomayskaya Street. A major cultural and green asset shared across the area is the 17th-century Izmaylovo Estate and Park, though its integration with everyday urban life remains limited. Overall, the districts suffer from monofunctionality, underused open spaces, and weak neighborhood identity.

Area size 1713 ha

Population 340 000

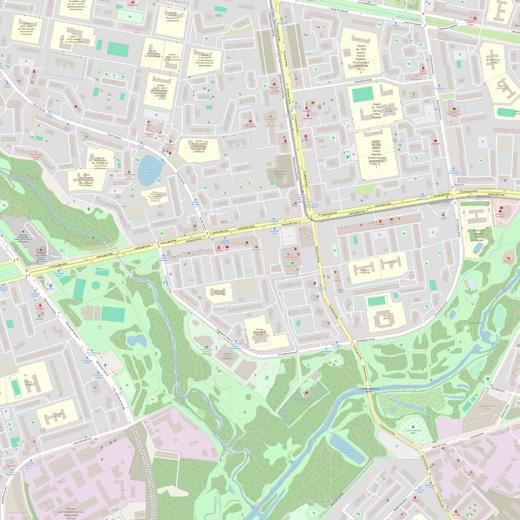

Dencity 198 people/ha

South and Central Chertanovo were primarily developed in the 1970s following the typical microdistrict model with open block structures and 9–12 storey slab apartment buildings. Despite a large population, the districts still suffer from insufficient functional infrastructure, particularly lacking a hospital and a metro station in south.

The availability of entertainment and leisure infrastructure is poor, with few shopping malls near metro stations acting as the only local attractors. Much of the urban fabric remains monofunctional.

The districts are bisected by the busy Varshavskoye Highway, contributing

to fragmentation and disconnection across neighbourhoods. While four metro stations serve the broader area, access is uneven.

A valuable asset — Bitsevsky Park — borders the district, yet its potential remains underused due to poor integration with surrounding public spaces.

South Chertanovo, in particular, demonstrates the lowest overall quality of urban environment among the observed districts, suffering from weak spatial structure, low functional diversity, and lack of identity. It highlights the urgent need for integrated spatial improvements aimed at balancing functions, activating public space, and re-establishing neighbourhood cohesion.

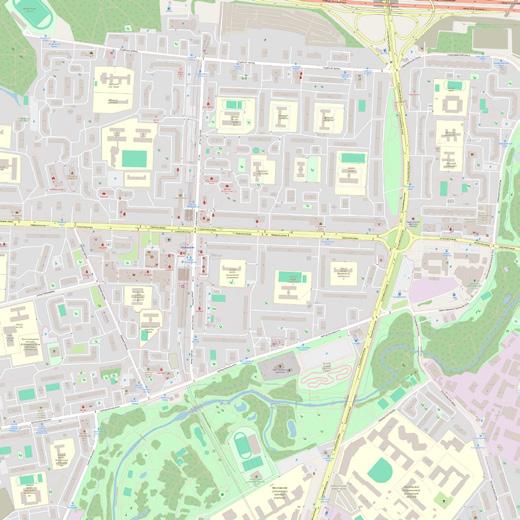

Area size 996 ha

Population 268 000

Dencity 269 people/ha

South and Central Chertanovo were primarily developed in the 1970s following the typical microdistrict model with open block structures and 9–12 storey slab apartment buildings. Despite a large population, the districts still suffer from insufficient functional infrastructure, particularly lacking a hospital and a dedicated metro station in the southern part.

The availability of entertainment and leisure infrastructure remains poor, with only a few shopping malls near metro stations acting as local attractors. Much of the urban fabric remains monofunctional, with limited places that

encourage informal social interaction or community gathering.

The districts are bisected by the busy Varshavskoye Highway, further contributing to fragmentation and disconnection within the area. Although well-connected with four metro stations inside and one nearby, the quality of everyday life is not equally distributed.

A notable asset is the proximity to Bitsevsky Park, which holds great potential as a natural anchor point. However, the underdeveloped internal structure and lack of strong public nodes limit its positive influence. The area remains in need of spatial strategies that can restore identity, balance functions, and strengthen community ties.

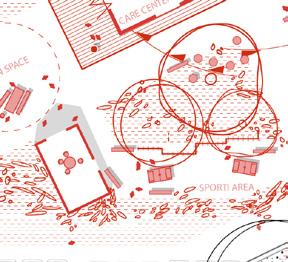

To define where my design can be most impactful in the field of urbanism—and to propose an alternative development approach to that of commercial developers—I developed a matrix of strategies. This matrix maps how key urban challenges manifest across different spatial scales, from XL (city level) to XS (building entrances and block level). Each scale demonstrates varying degrees of issues that affect residential quality, and each requires action from different stakeholders and authorities.

For instance, challenges such as «areas affected by industry» can only be addressed at the higher levels of city governance and through national industrial policy. As an urban designer, my role is to advocate for a responsible

transition toward cleaner, more sustainable production, integrated thoughtfully into the urban environment. However, as these decisions lie beyond the design scope, this challenge is acknowledged but not directly addressed in my interventions.

Instead, my focus lies on M (Northern Izmaylovo as a neighbourhood), S (a selected district within it), and XS (several building blocks and their entrances). At these levels, in collaboration with specific stakeholders, it becomes possible to initiate context-sensitive improvements and gradually address the most pressing issues in a tangible and scalable way.

The matrix outlines the main project actors and how their roles intersect with specific key challenges.

District planning & maintenence

City urban planning

Local cultural Institutions

Izmailovo museum

Local cultural Institutions

Izmailovo museum

N.Ismailovo Municipality

Independance comercial comapnies

Individual grosery store

Self-organised Moscow program

History walk in Moscow

Local enthiasts

Motivated person

Cultural agents History enthusiasts

Cultural agents

History enthusiasts

Cooperation of craftsmen

Groups from the Izmailovo Kremlin

Cooperation of craftsmen

Groups from the Izmailovo Kremlin

3/4/6

Independant artist

Person from area

Groups of residents

Ecological Movenment + Collaborative Design

Neighbours in the hous

Individual person

Independant artist

Person from area

Groups of residents

Ecological Movenment + Collaborative Design

Neighbours in the hous

Individual person

Tourism office Small office

Self-organised Moscow program

History walk in Moscow

Self-organised Moscow program

History walk in Moscow

Self-organised Moscow program

History walk in Moscow

Neighbours in the hous

Individual person

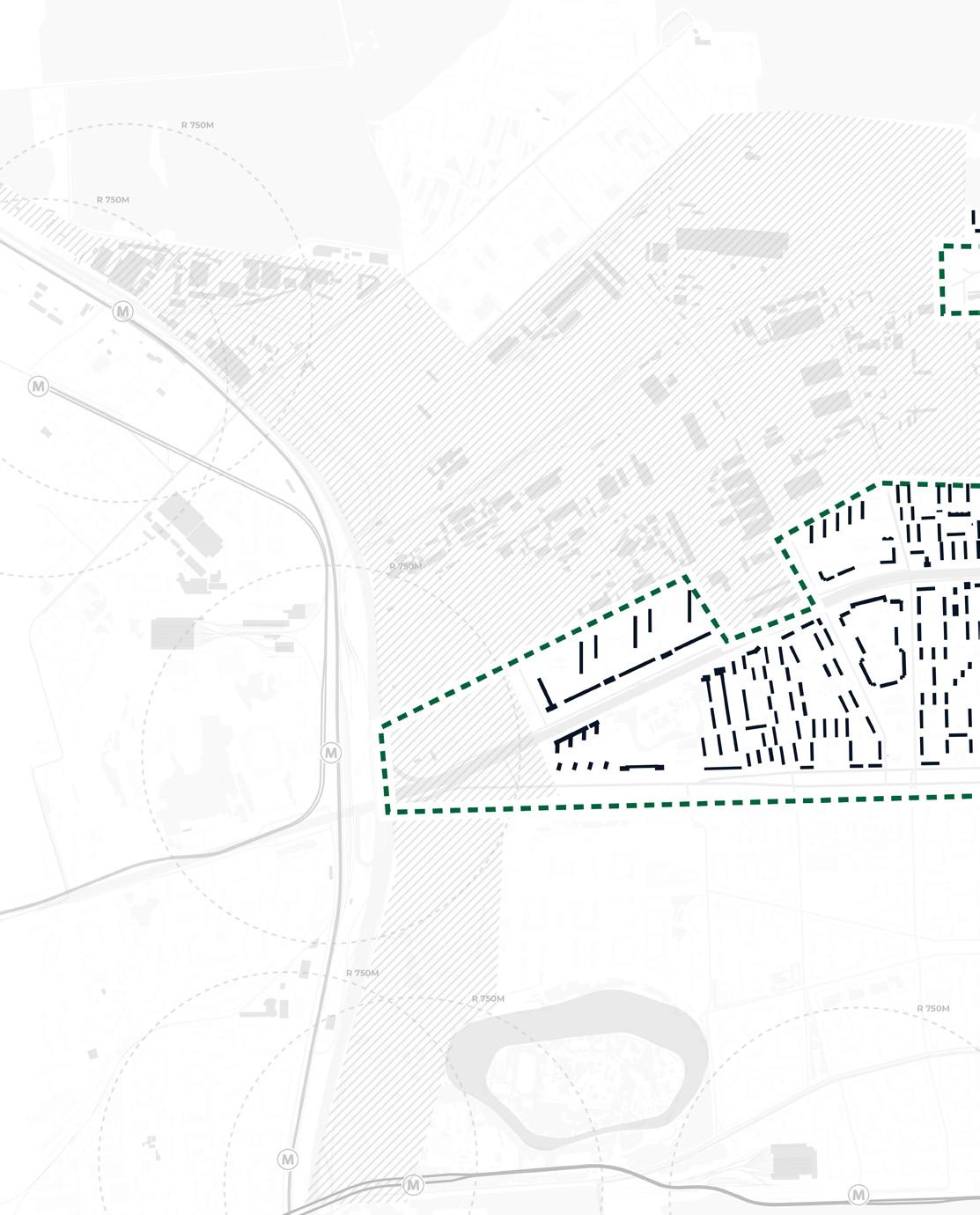

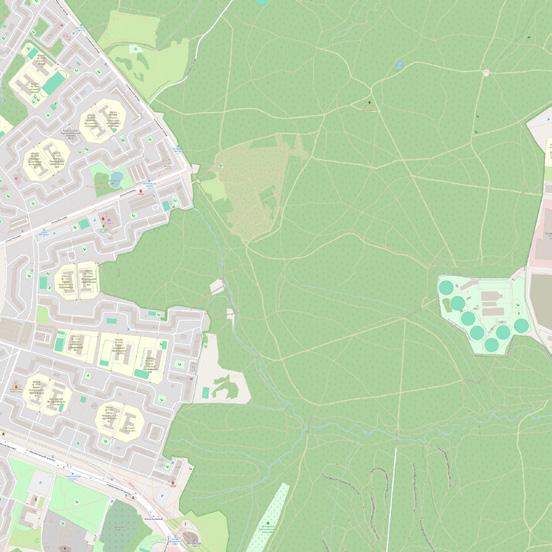

A focused analysis of the most disadvantaged territory— Northern Izmailovo. This chapter explains why the site is the starting point for design intervention, based on both its spatial disconnection and social vulnerability.

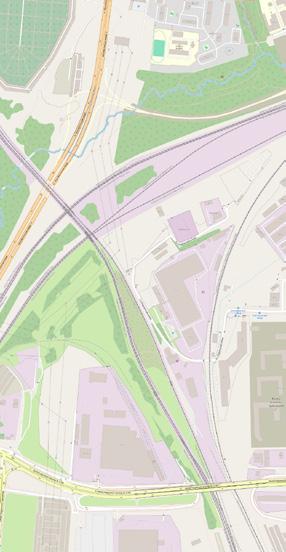

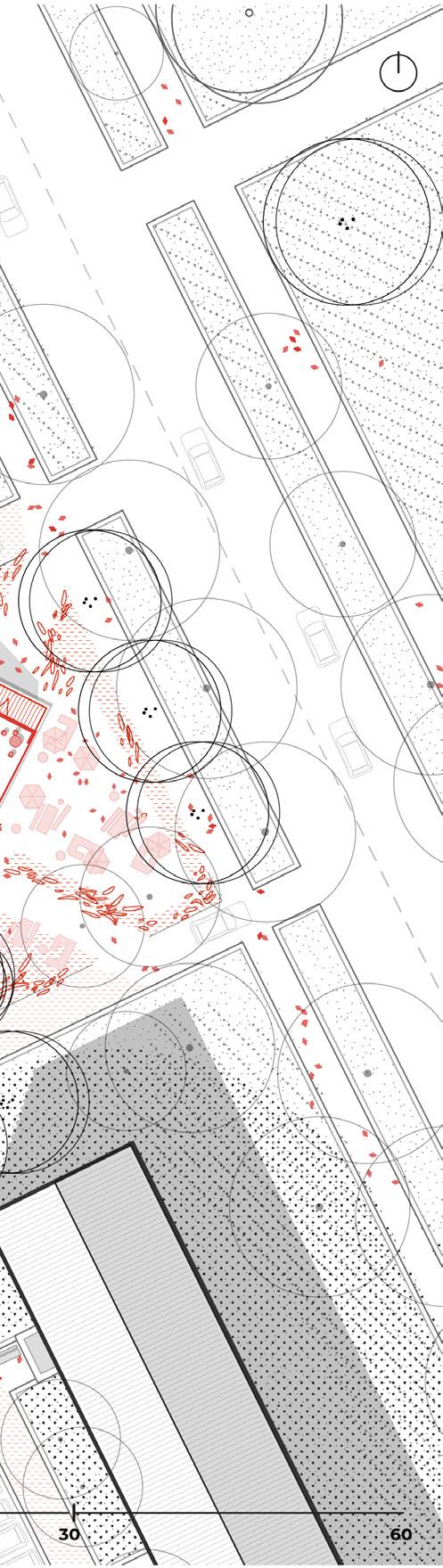

In the north of the territory, a large elevated road infrastructure runs through the area, generating constant noise and creating a significant physical and psychological barrier. To the south, all zones border a wide green boulevard that contributes to the identity of the sub-zones.

Sub are 2 and 3 benefit from stronger connectivity, including better proximity to metro stations and access to commercial amenities. These zones demonstrate relatively higher levels of functional balance and liveliness. In contrast, sub areas 1 and 4 experience

limited access to public transportation and an overall fragmented spatial structure.

However, Sub area 1 stands out as the most vulnerable—it lacks transit accessibility, suffers from spatial disconnection, and shows the clearest signs of social neglect and environmental discomfort. These layered issues make it the most urgent site for a pilot design strategy.

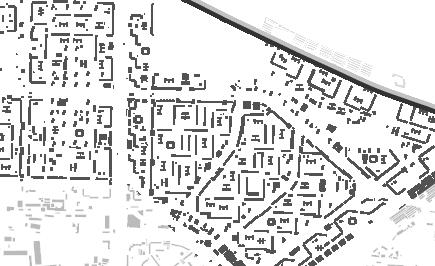

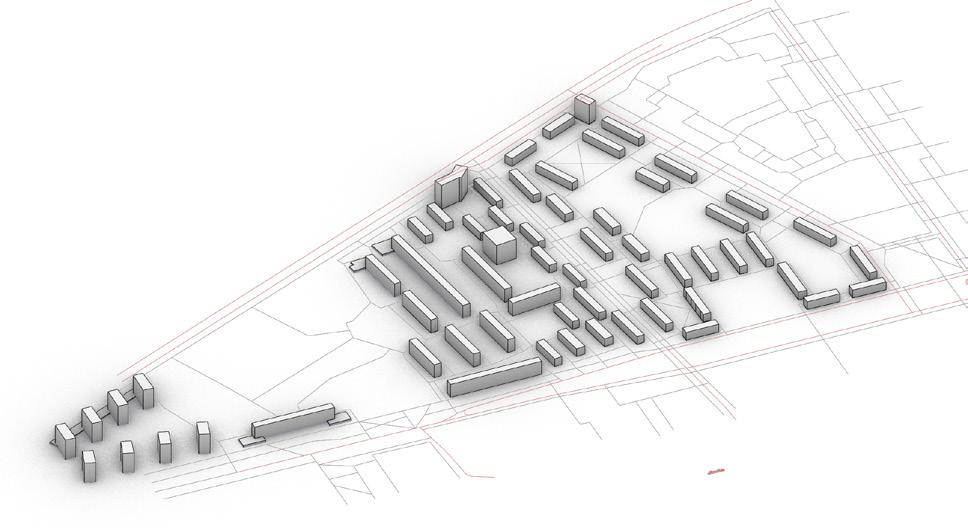

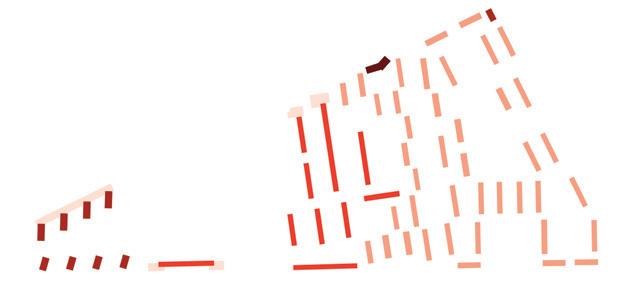

This northeastern district of Moscow covers 78 hectares and houses around 13,000 residents. With a gross density of 167 people/ha and a net density of 783 people/ha, it reveals a typical imbalance: large areas of undefined space contrast with dense pockets of living.

The area reflects widespread challenges of Moscow’s outskirts. Built between the 1950s and 1980s, it includes fivestory Khrushchev-era blocks, extended nine-story slabs, and scattered high-rise towers. While green space is present, it often lacks clear purpose or ownership.

Here, key urban vulnerabilities are visible in daily life. Unclear boundaries between private and public spaces lead to neglect. Financial and leisure

dependence on the city center forces long commutes. Functional imbalance— mostly housing, little commerce or culture—creates monotony. These spatial issues contribute to an un well present of local identity, weakening community bonds.

Yet within this structure lies potential. Recognizing these shortcomings as design opportunities allows us to shift the narrative—from forgotten periphery to a space of reactivation and community growth.

The area is composed of mostly low-rise buildings (up to 5 storeys), a few mid-rise blocks (6–9 storeys), and several high-rise towers (above 12 storeys) placed on the periphery.

The district features typical Soviet-era slab housing 50-60s, including linear panel blocks 70-80s and tower-type buildings 80s. The layout follows an open block structure with buildings spaced apart, forming the classic microdistrict pattern.

The district is framed by a highway to the north and a tree-lined pedestrian boulevard to the south. Two connector roads pass through the eastern part, linking the northern and southern edges, creating basic but effective mobility routes.

The southern boulevard doubles as a green spine for the area, offering walkable, shaded space. On the western edge lies the Lilac Garden — a local landmark tied to the district’s origins. Between the 1960s housing blocks, wide green courtyards offer relief and potential for local use.

The design should respond to local representations—this is the starting point of the process

tactical urbanism, citizen engagement

R-Urban Network is a citizen-led urban strategy developed in Paris suburbs. It creates a network of small-scale hubs— urban farms, recycling stations, cooperative spaces— directly within residential areas. These spaces promote local resilience, resource reuse, and civic engagement.

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

reconnection of fragmented areas, bottom-up initiative

Developed in Rotterdam, Luchtsingel is a crowd-funded pedestrian bridge that reconnects fragmented urban areas. Initiated by ZUS architects, it links underused spaces, creating new flows and sparking revitalization. The project showed how temporary, citizen-backed interventions can lead to lasting structural change.

soft activation of urban voids, mobility and community

A seasonal city program by the Moscow Municipality that installs open-air pavilions across the city. These pavilions promote traditional local goods and crafts, supporting small-scale producers while creating temporary meeting spots that animate public space during summer months

Portland, Oregon, USA

long-term strategy, self-sufficiency in the suburbs

Based in Portland, City Repair empowers communities to transform public spaces through participatory design. Through small-scale interventions—like street paintings, community benches, and shared kiosks—it turns intersections into gathering places, promoting a stronger sense of belonging and local ownership.

Brussels, Belgium

intimate neighborhood-scale intervention, soft infrastructure

A minimal public reading room placed in the middle of a housing district. Designed to be an open, inviting structure, it offers a quiet spot for rest, reflection, and informal gathering—helping build slow, steady relationships between residents through shared space and rituals.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

sustainability, green space engagement

An urban garden project in a socially mixed neighbourhood, located on a formerly vacant plot. Residents are invited to co-grow vegetables and herbs while joining communal activities. It enhances food awareness, promotes sustainability, and helps build trust among neighbours

highlight civic engagement but at different urban scales

This Brussels-based collective initiates urban projects focused on social equity and participation. Working with local communities, they transform neglected areas through temporary structures, events, and workshops. Their work demonstrates how artistic and civic actions can influence long-term urban policy and spatial justice

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

intergenerational program, cultural integration

Once a ferry company’s canteen, Tolhuistuin is now a vibrant cultural hub on the north side of Amsterdam. Its diverse programming—ranging from music and food to education and community events—fosters intergenerational exchange and brings together residents from across the city.

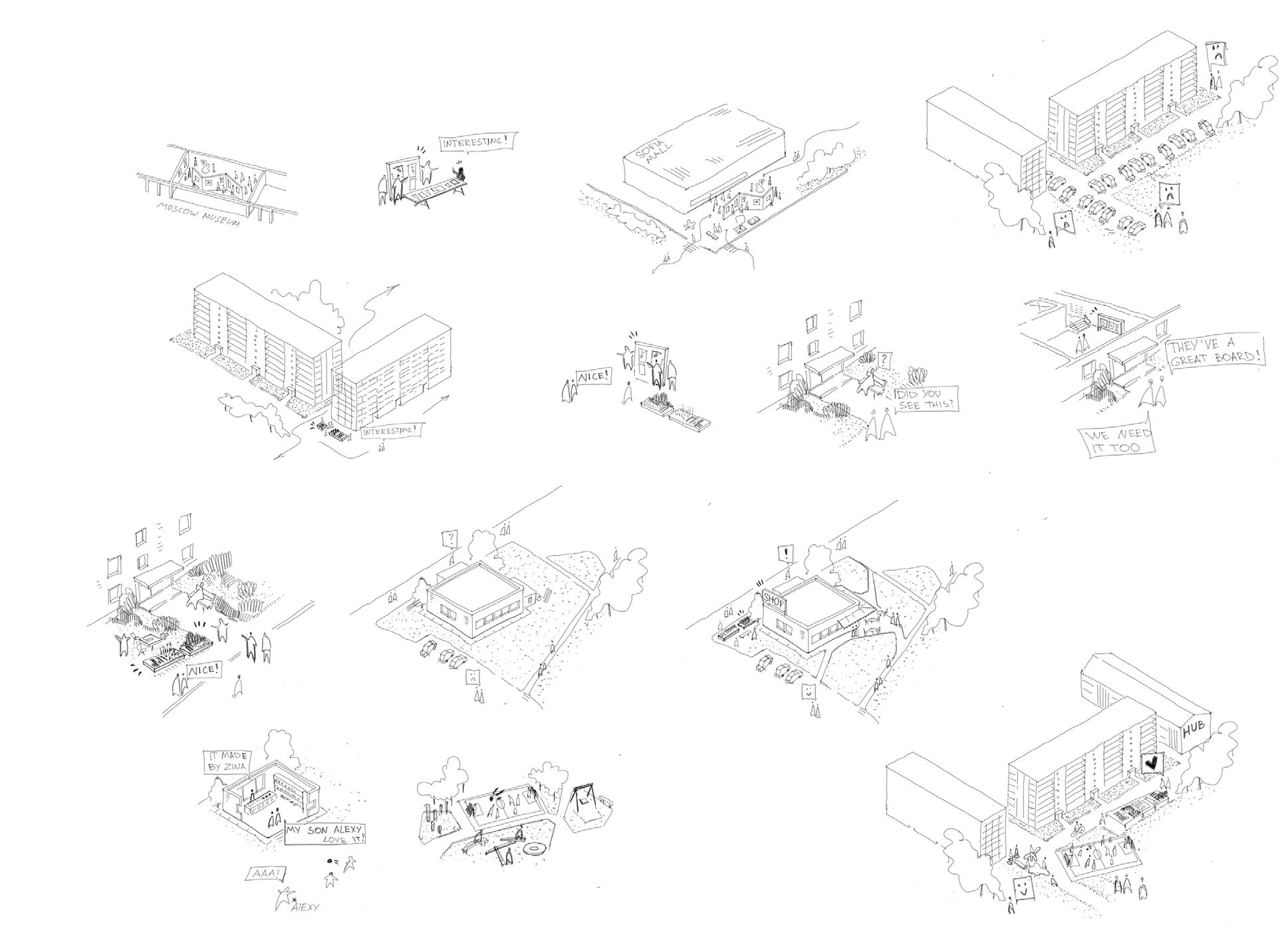

Small-scale interventions begin at the most intimate level—the doorstep. This chapter explores how minimal but targeted design elements in entrance zones can create momentum for larger change through everyday engagement.

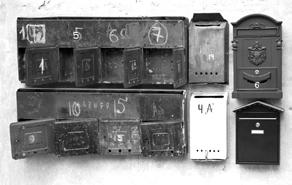

The entrance area represents the smallest, yet most meaningful, publicprivate threshold in residential life. It is a shared space that almost all residents pass through daily—connecting the wider city to their most personal environment. Precisely because of this, the entrance becomes a key location to observe and influence everyday life patterns.

Across age groups, this threshold space holds unique functions:

• Children play near the entrances, often within sight of older generations.

• Working-age residents pause here briefly after long commutes, smoking, chatting, or simply decompressing.

• Elderly residents gather on benches to rest, exchange news, or maintain informal social networks.

This daily convergence makes the entrance a central node of neighborhood life—a space of routine encounters, informal care, and quiet rituals. Therefore, in aiming to reshape urban strategies through a people-oriented lens, design interventions must begin here.

By closely observing these behaviors on site, it became clear that the entrance is not merely a physical passage, but a cultural and social space—one that has the power to reflect and reinforce communal identity. Starting here allows design to address broader urban challenges through the lens of lived experience.

Benches become temporary stages of daily rituals — quietly shared across generations, they anchor the rhythm of local life

Scattered informal elements — like makeshift objects or repurposed materials — act as symbolic traces of presence, marking the invisible boundaries of belonging.

- 20m

Tucked between faceless blocks, small playgrounds transform into liminal zones, where young people shape social memory through spontaneous, often unstructured encounters.

1

Up to 50 people use the one stairway

4

Up to 200 people use the four stairways

1 Floor in 1 Stairway

Four families and up till 10 people

Starting the design from the entrance areas is a strategic decision. These are the most frequently used public spaces—every resident crosses them daily on their way to and from home. By improving these transitional zones,

it is possible to reach and impact the largest number of people with minimal intervention. This approach ensures high engagement and visibility from the very beginning.

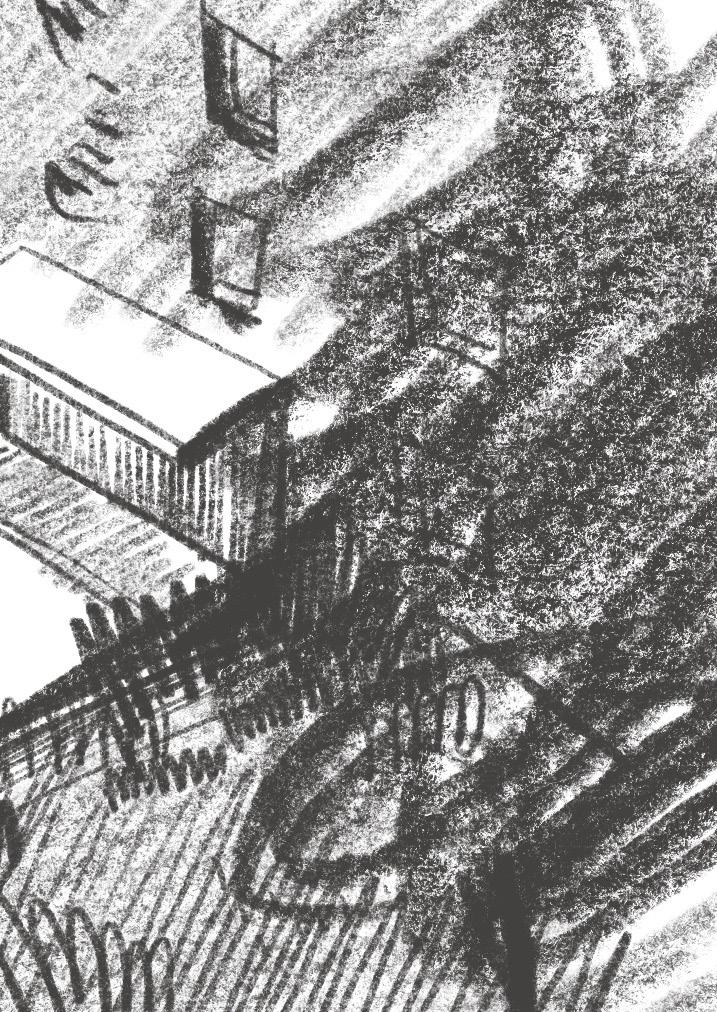

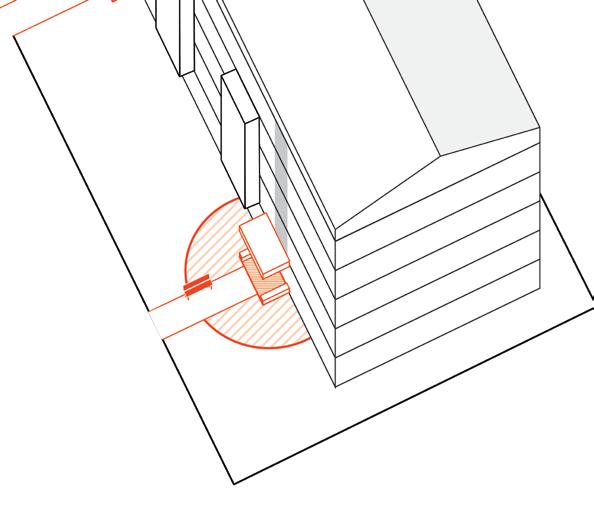

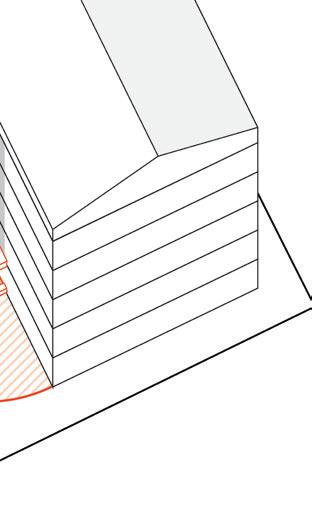

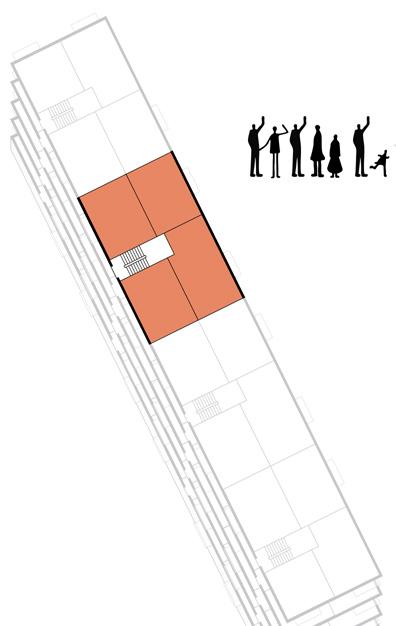

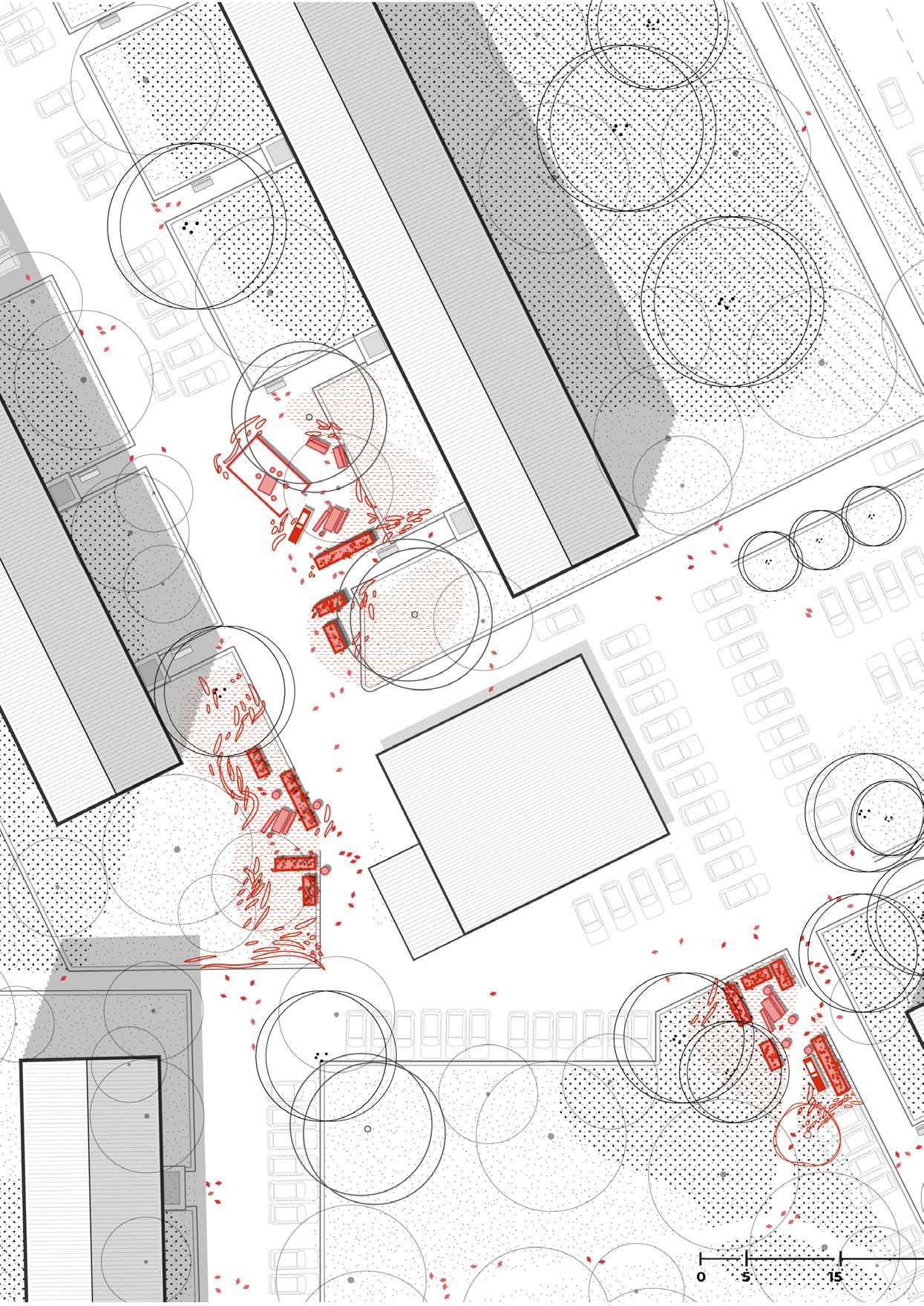

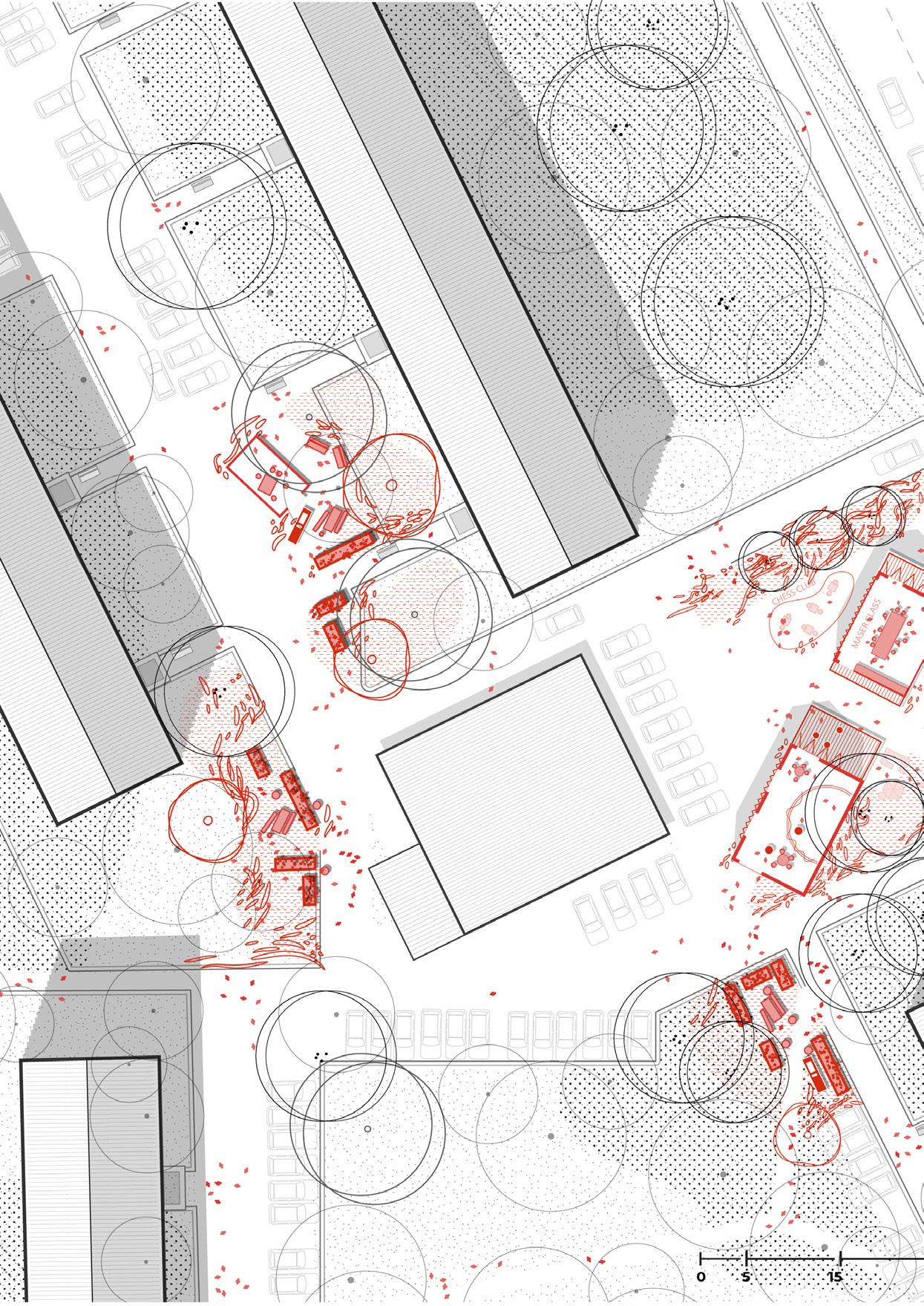

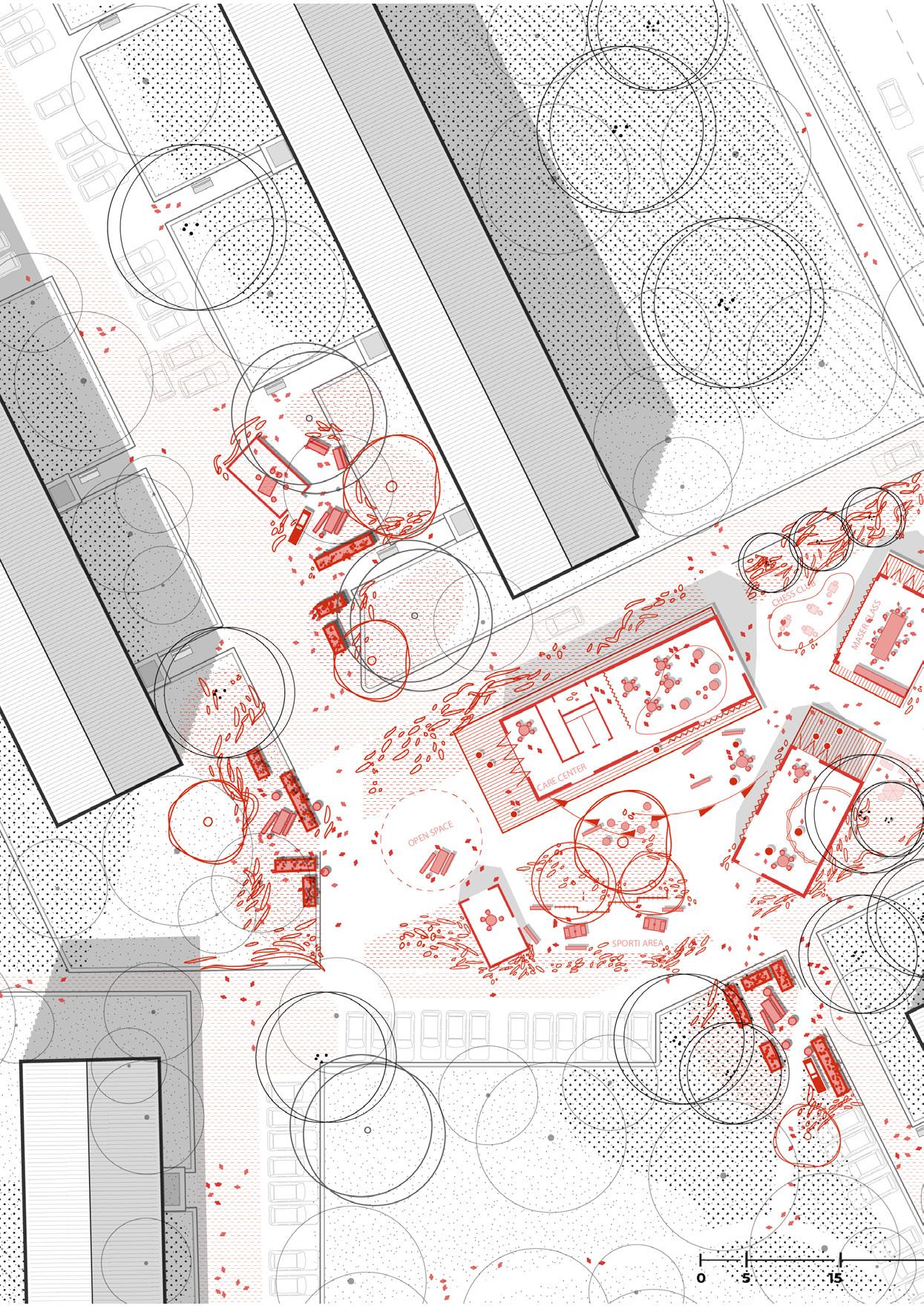

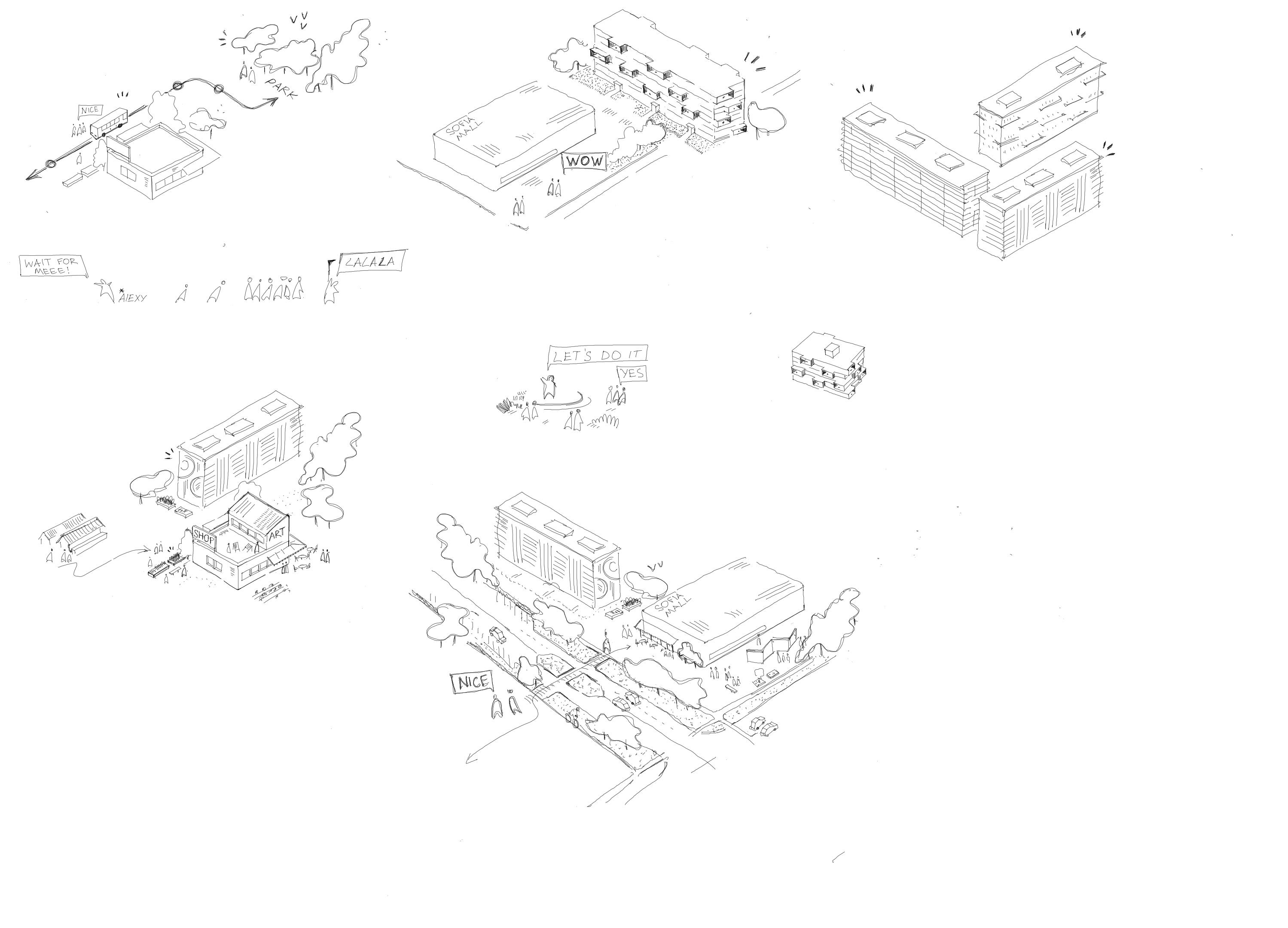

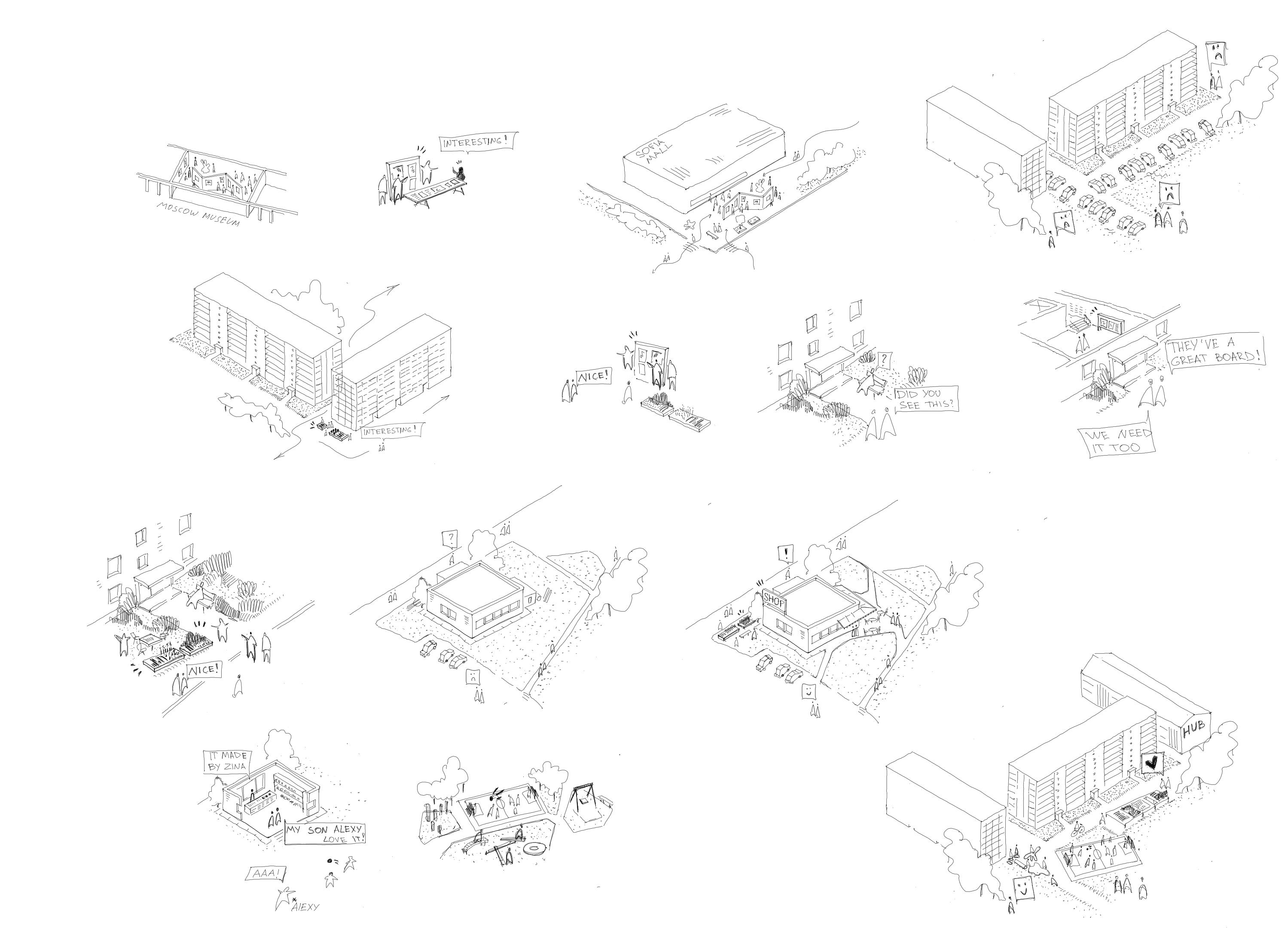

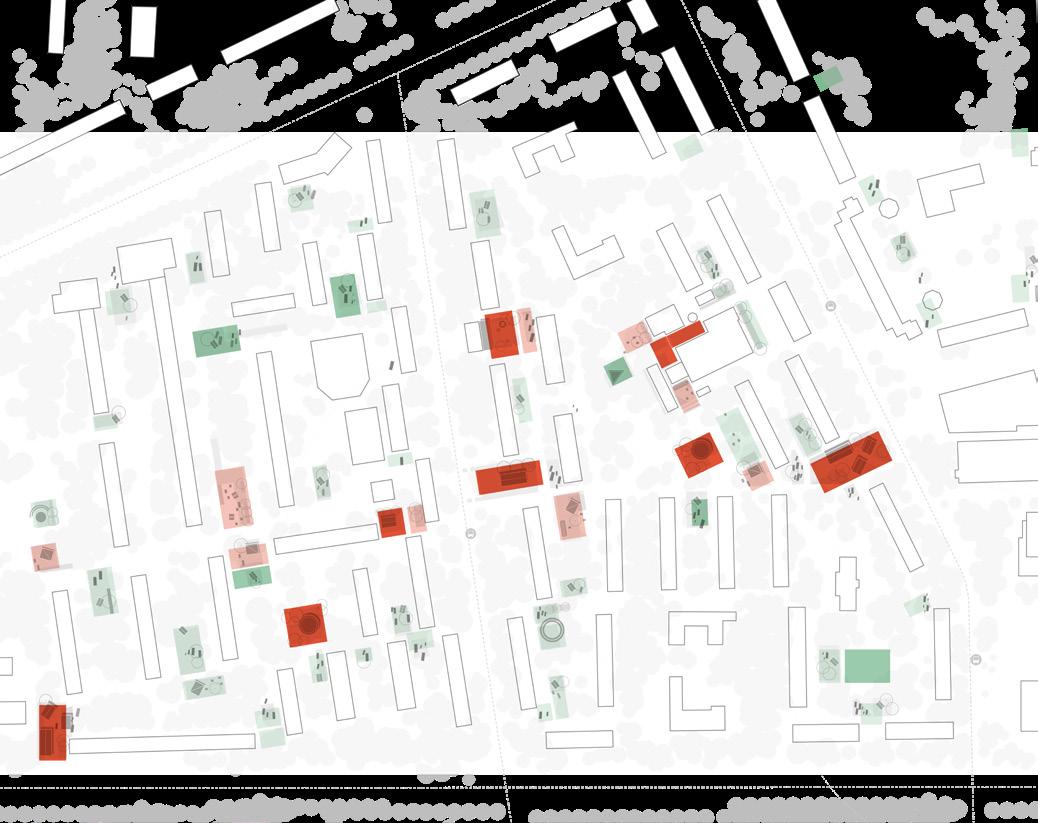

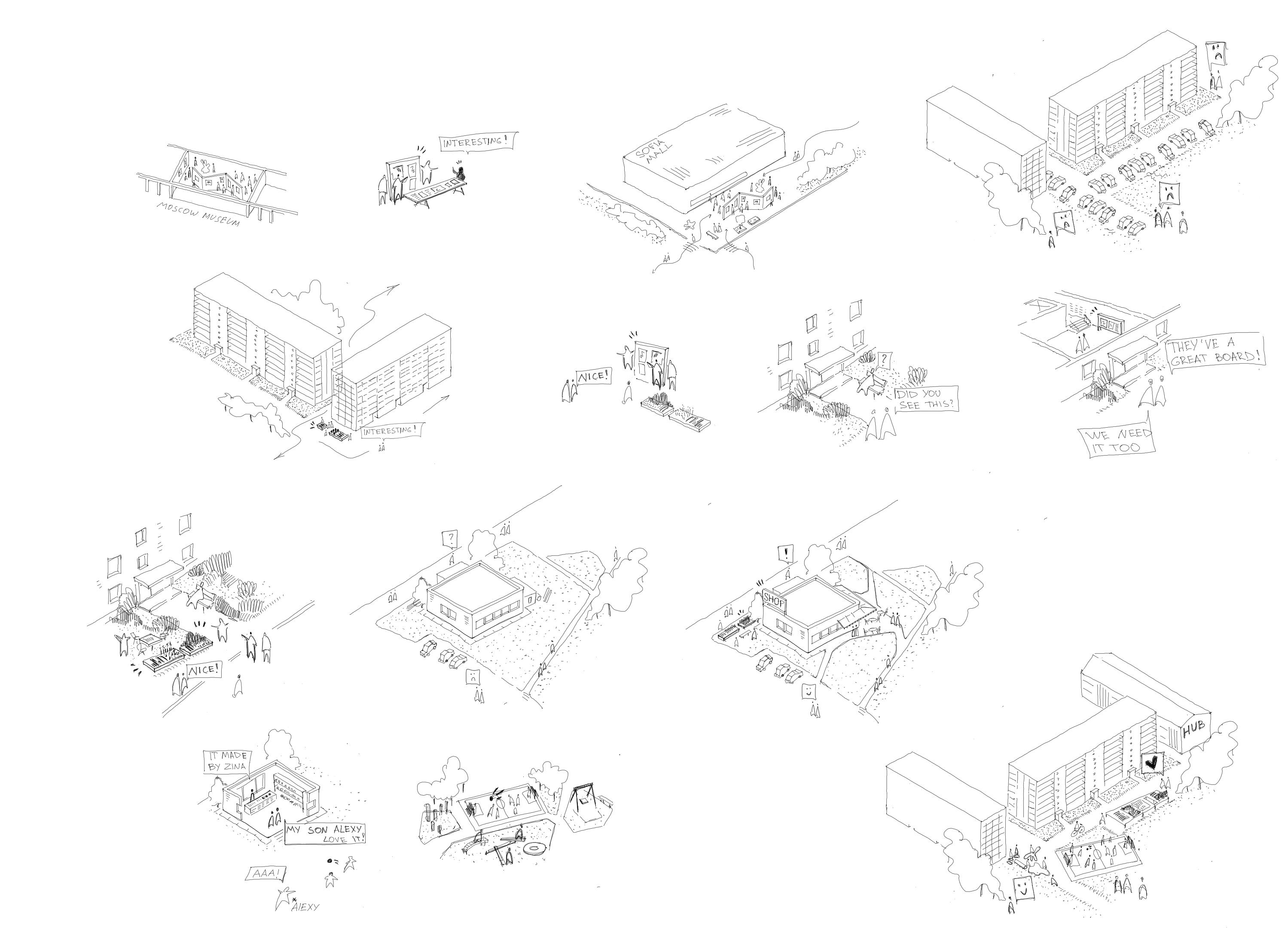

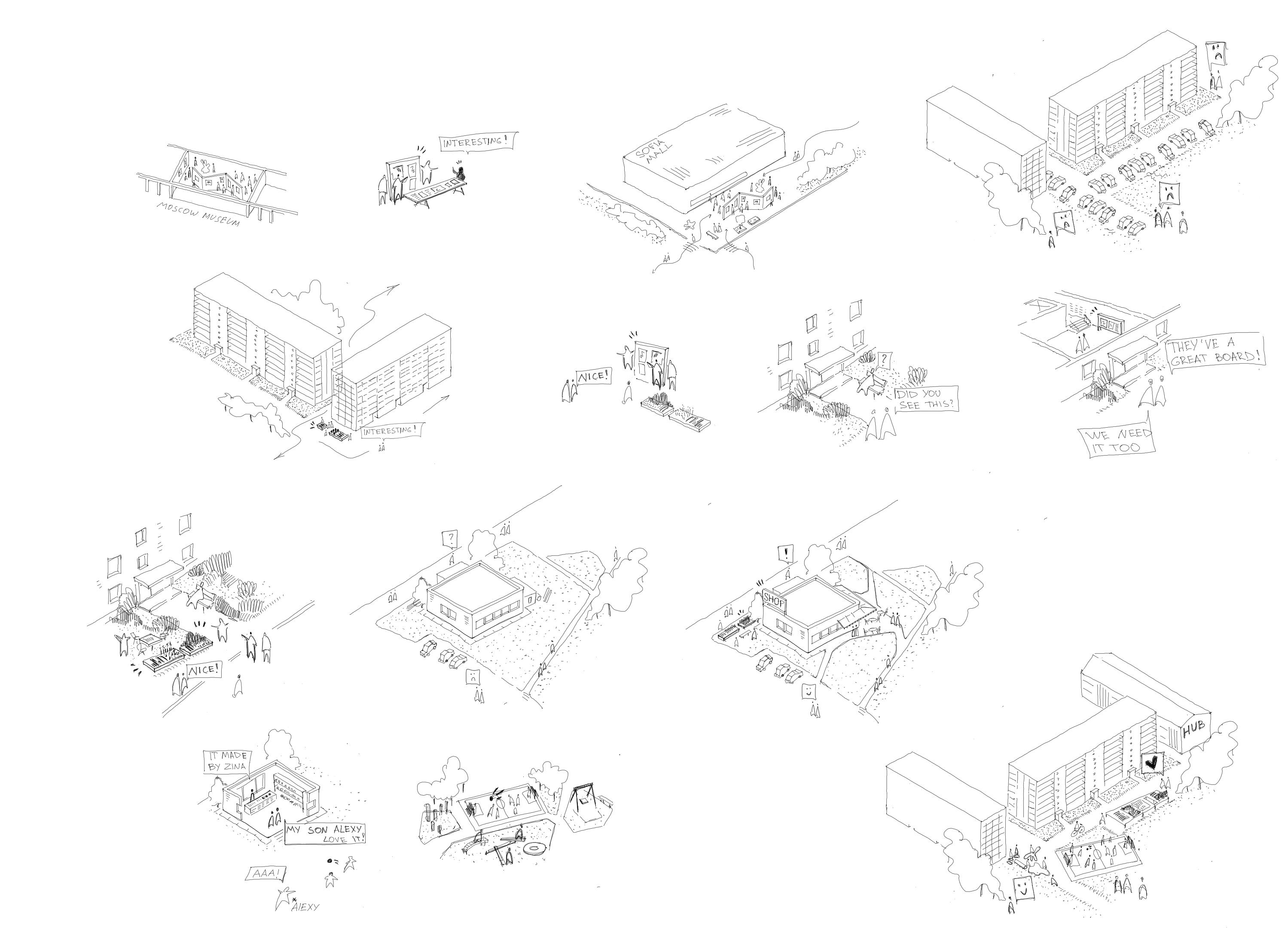

My design follows a phased spatial strategy, beginning at the smallest scale XS and gradually expanding. The first step targets the entrance areas— ‘doorsteps’—which are positioned visibly along the neighbourhood’s internal routes. These are the most frequently used public spaces, providing a highly accessible entry point for change.

As residents begin to interact with these improved thresholds, the intervention expands to the S scale, activating shared spaces between the blocks These in-between zones allow for community programs and informal interactions within a semi-public environment.

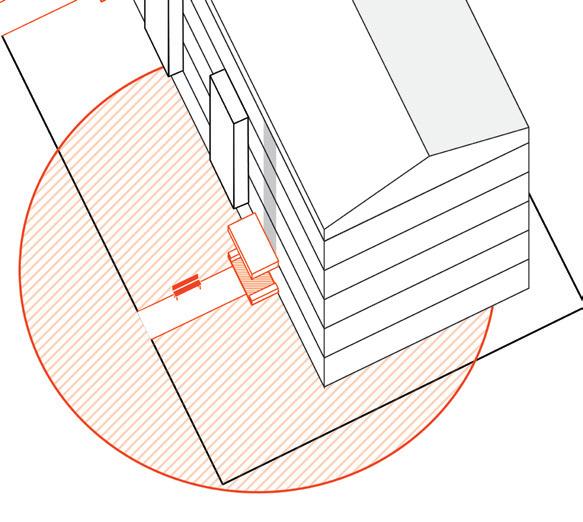

From there, the design evolves into M scale interventions—collective spaces—utilizing larger vacant areas between blocks. Positioned along the most used pedestrian paths, these spaces form new social fronts within the neighbourhood and strengthen spatial cohesion.

Eventually, the design reaches the L scale, integrating all previous stages into a dense and adaptive urban network. This final step supports flexible programming, new pedestrian flows, and long-term neighbourhood transformation. Each stage builds upon the previous one, ensuring continuity, responsiveness, and deepening impact over time.

Collective interventions

Habitation

An in-depth explanation of the design strategy across different scales. It shows how a series of contextual interventions—gardens, pavilions, public furniture— can incrementally reshape the quality of life and urban identity.

I’ve met here here yesterday

Let’s meet the plants!

The design starts at the doorstep—the smallest yet most meaningful shared space residents cross daily.

By placing informal urban gardens near building entrances and along main streets, I create visible, recognisable spaces that belong to the people who live there. These gardens mark the moment where private life meets public space.

Though small, these spaces host essential everyday interactions: a short rest after work, a quick chat with a neighbour, a child’s game. These micromoments form the social glue of the neighbourhood. The gardens act as soft triggers for engagement, making residents more aware and connected to their surroundings.

Starting here allows design to emerge from lived experience—grounded in daily use, not imposed from above. It’s the first step in reshaping collective space through quiet, continuous presence.

A set of urban gardening beds and sitting space is placed irregularly in the vacant areas between building entrances, integrated with the existing trees.

By strategically positioning the elements to be visible from main streets and entrances, they will symbolically mark the threshold between public and private space.

Do you want tea?

This sounds interesting! I can bring a cake

We are planning to celebrate my cousin’s birthday here

Let’s ask them in the house!

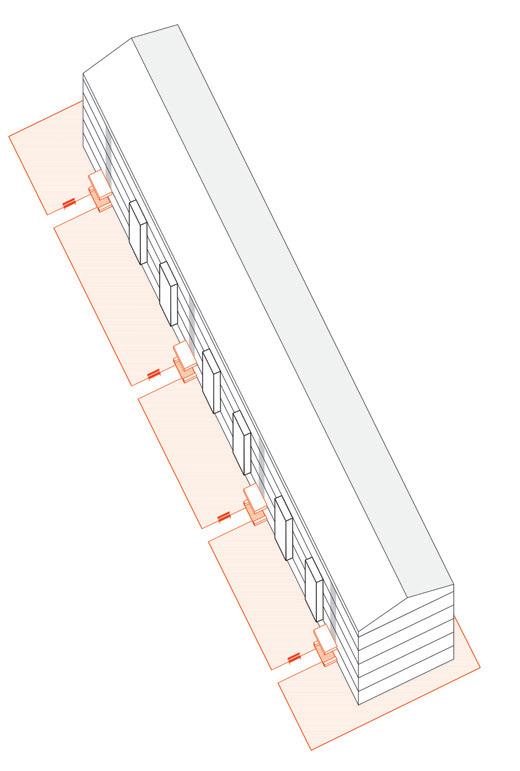

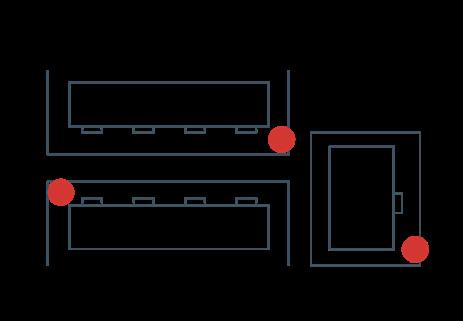

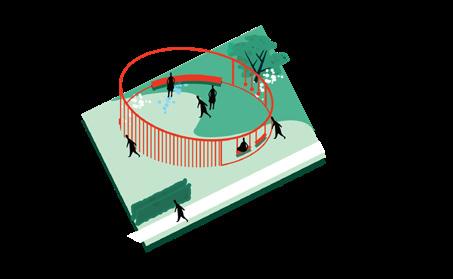

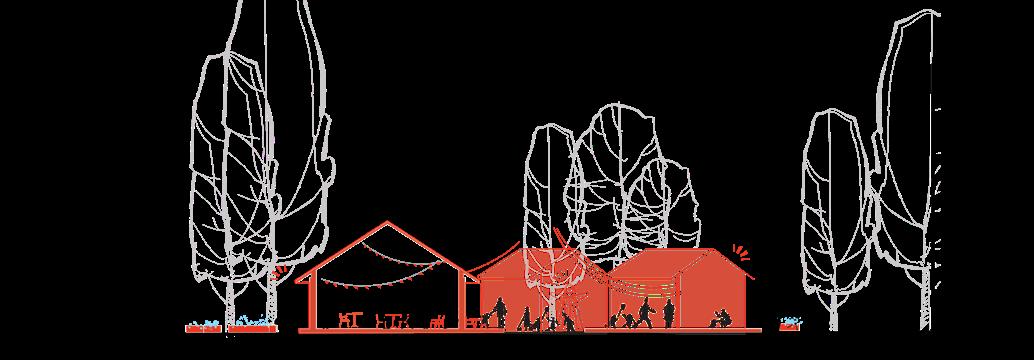

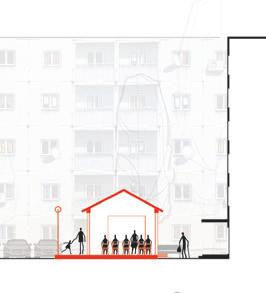

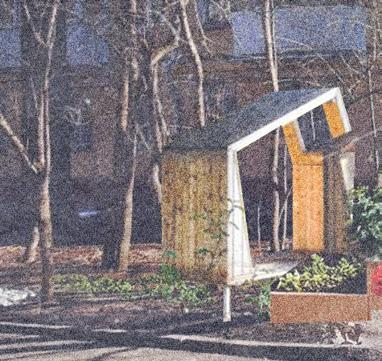

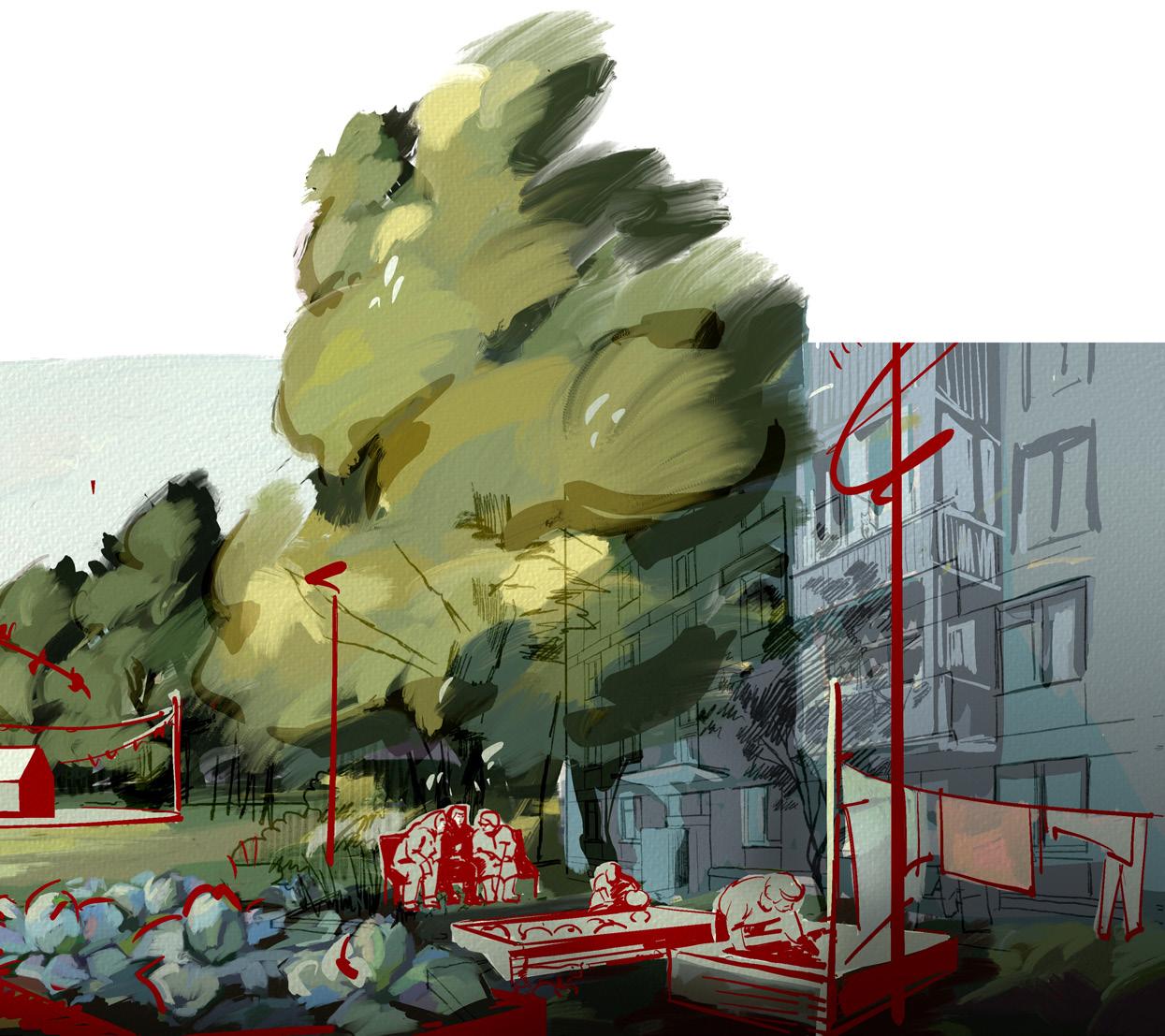

At the S scale, I continue the strategy of informal urban gardens but introduce a small communal pavilion designed to host gatherings of 10–15 residents. Constructed from natural materials, this structure evokes associations with summer cottages or garden houses— creating a sense of familiarity and comfort. It is equipped with basic utilities such as electricity and water and is naturally insulated for year-round use.

From an urban design perspective, the pavilion replaces a few parking spots, creating a livelier, greener, and more socially responsive environment. Its placement ensures passive social control—facing the inner courtyards and overlooked by residential windows— while maintaining respectful distance from ground-floor apartments to avoid noise or light obstruction. Surrounding vegetation and semicircular seating further enhance the space, offering an intimate and accessible setting for informal meetings and everyday use. The adjacent road is slightly narrowed, calming traffic and improving pedestrian comfort along the intervention zone.

Collective space

A small, summer house–like paviliontogether with seating elements, forms an informal gathering space for all residents.

Let’s meet by the pavilions

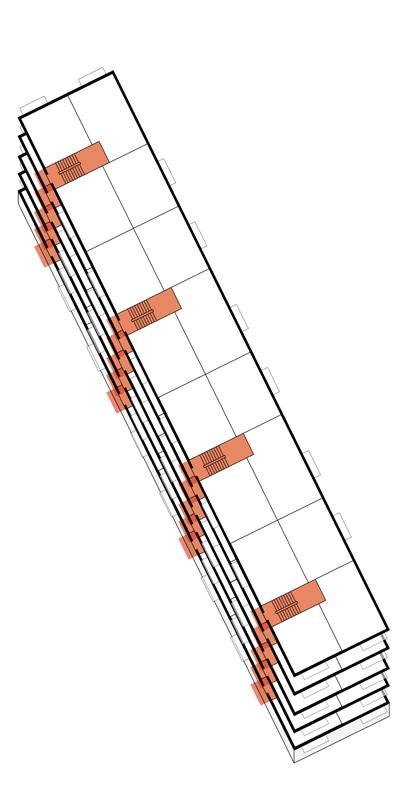

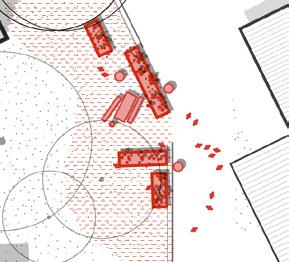

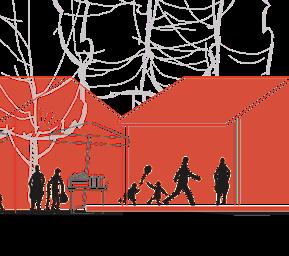

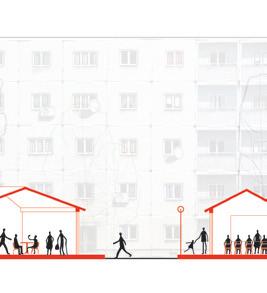

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.

These pavilions serve flexible community needs—hosting workshops, markets, coworking sessions, or care programs for elderly and children. Their function can shift depending on time of day or season, creating a dynamic local hub. Their angled placement ensures visibility from key walking routes and minimizes acoustic disturbance for nearby residents.

Located along the most frequented pedestrian paths, these structures are designed to activate overlooked spaces and provide adaptable rooms for both quiet and social activities—supporting stronger neighbourhood identity and accessibility for all users.

The position of the pavilions responds to the surrounding infrastructure and is designed to stand out among the standardized residential blocks.

The flexible nature of the pavilions allows residents and existing programs to activate them, fostering vibrant dynamics in the neighbourhood.

She told me this! No way!

I own them a book, lets go there

Which film are they showing tonight?

Something about cats

I made a honey beer, I’ll bring it tonight!

The adaptive design can naturally evolve into a larger structure—such as a main hall pavilion—or remain at a smaller scale if needed. The main pavilion enables a broader range of permanent uses while shaping the surrounding space into a more intimate and socially oriented environment.

The interior of the pavilion serves as an open, creative hub where multiple generations can meet. Its programmatic flow is designed to engage all age groups, while also accommodating larger community events and spontaneous interactions.

This pavilion supports long-term community growth by offering a dedicated place for work, gatherings, and informal rest. It helps address key local challenges by creating a multifunctional environment rooted in everyday life.

While the area benefits from existing lush greenery, there is a visible lack of lower-scale vegetation at eye level. To enhance the spatial quality, the design introduces small communal planting beds to soften the environment and improve microclimate and identity.

The layout ensures smooth functional transitions and a cohesive spatial flow. This encourages natural interaction between spaces, supports diverse daily use, and adapts flexibly to residents’ needs throughout the day.

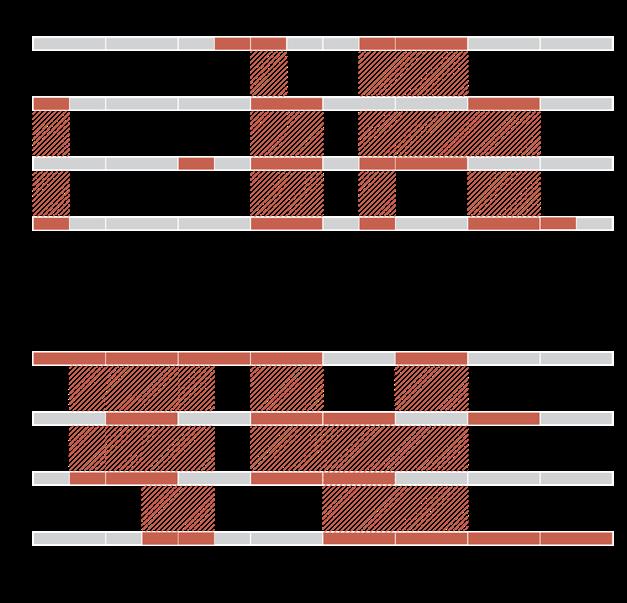

To design meaningfully for peripheral neighbourhoods like Zone 1, I analysed when and where people are present, active, or potentially open to interaction. Every neighbourhood follows a rhythm—what I call the “people’s clock.” Residents move between their homes, jobs, and social lives in a pattern that leaves clear spatial and temporal gaps. These gaps, if addressed with the right functions placed in strategic locations, can enrich the neighbourhood’s vitality. This method allowed me to develop a targeted functional program that aligns not only with spatial needs but also with lived daily routines.

Weekdays: Residents are mostly absent during working hours, returning around 18:00–20:00. Seniors and small children are more visible during the day, often without designated space to stay or interact.

Weekends: Activity patterns shift. By noon, older and middle-aged groups emerge for leisure, often accompanied by children. Young adults tend to appear later in the afternoon or evening, seeking social and cultural engagement. However, the existing infrastructure does not support these needs across age groups, especially for creative, playful, or eveningoriented spaces.

Functional program: strategic response to time-based needs and challenges

By introducing diverse, timesensitive, and communityoriented functions, we can begin to reverse patterns of fragmentation and activate underused urban space.

Urban gardens and communal green spaces

Encourage daily interaction and stewardship; reconnect people with their environment and promote informal communication among residents of different generations.

Addresses: social atomization, lack of identity, environmental neglect.

Semi-open market/food pavilion

Provides a vibrant meeting point for weekends, enhances local economy, and supports small business activities.

Addresses: lack of public life, economic stagnation, generational disconnect.

Micro-woodlands and calm zones

Offer restorative, inclusive spaces for all age groups; support mental well-being and enrich the spatial quality of the neighbourhood.

Addresses: environmental stress, absence of soft landscape, density overload.

Playgrounds and Covered sport fields

Promote active use by children and families throughout the day and encourage safe movement in public space.

Addresses: youth isolation, underutilised courtyards, lack of safety.

Social pavilions and creative hubs

Serve as adaptable spaces for workshops, meetings, or care services. They build local social infrastructure and foster new patterns of cooperation.

Addresses: weak institutions, limited social infrastructure, ageing population.

Nightly usable spaces (bar, music, evening programs)

Create safe and inclusive areas for young adults; offer visibility and agency to groups that are often excluded from suburban planning.

Addresses: absence of nightlife, invisibility of youth, reliance on the city centre for culture.

The introduction of new functions within Zone 1 will reshape both movement patterns and spatial perception in the neighbourhood. Currently, pedestrian flows are sparse and primarily radial— limited to functional routes connecting home to metro or transit points, with little incentive to stay or circulate locally.

By embedding diverse and strategically positioned functions—such as markets, social pavilions, gardens, and play areas— into the spatial gaps, the neighbourhood transforms from a transit corridor into a lived public environment. New desire

paths emerge, connecting entrances, open spaces, and programmatic nodes. These shifts encourage slower, more purposeful movement, foster casual interactions, and stimulate layered use throughout the day.

As a result, mobility becomes more organic and multidirectional, and the neighbourhood gains in legibility, accessibility, and identity. The increased foot traffic and social presence contribute to safer streets, stronger spatial coherence, and a richer urban atmosphere.

The design interventions are not limited to a fixed location or form. Instead, they are conceived as flexible frameworks that can adapt to the diverse urban environments found across Moscow’s outskirts. Whether inserted into a tight courtyard, an underused green space, a road edge, or a wide open field, each function—be it a pavilion, urban garden, or play area—can be tailored to the site’s physical, visual, and social context.

This adaptability ensures that the interventions respond to existing spatial hierarchies and resident routines while reinforcing human-scale qualities. By embedding design into different typologies of space—semi-private house fronts, connective thresholds, and overlooked inner courtyards—the project gains the potential to organically grow within the city fabric, supporting both everyday use and long-term transformation.

Green areas located near building entrances or on the rear side of the block.

A broad street with the potential to accommodate programmable public uses.

Small interstitial spaces situated between buildings within the urban fabric.

Open areas at the edge of the neighbourhood, adjacent to main roads.

Underutilized areas within the urban structure, such as parks or green zones with small playgrounds.

Large open plots within the urban fabric, typically near major roads and surrounded by highrise buildings.

interested to generations

flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

L Functional pavilion / local centers

interested to generations

flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

L Quiet garden

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

L Small amphitheater for performances

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

L Summer movie screen

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

interested to generations

flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

M Urban sports

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

M Community kitchen

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

M Craft/flea pop-up markets

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

interested to generations flexibility

attractiveness

interested

attractiveness

interested

attractiveness

interested

interested

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

interested to generations flexibility parameter attractiveness to others

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

XS Outdoor tables

interested to generations flexibility parameter

attractiveness to others

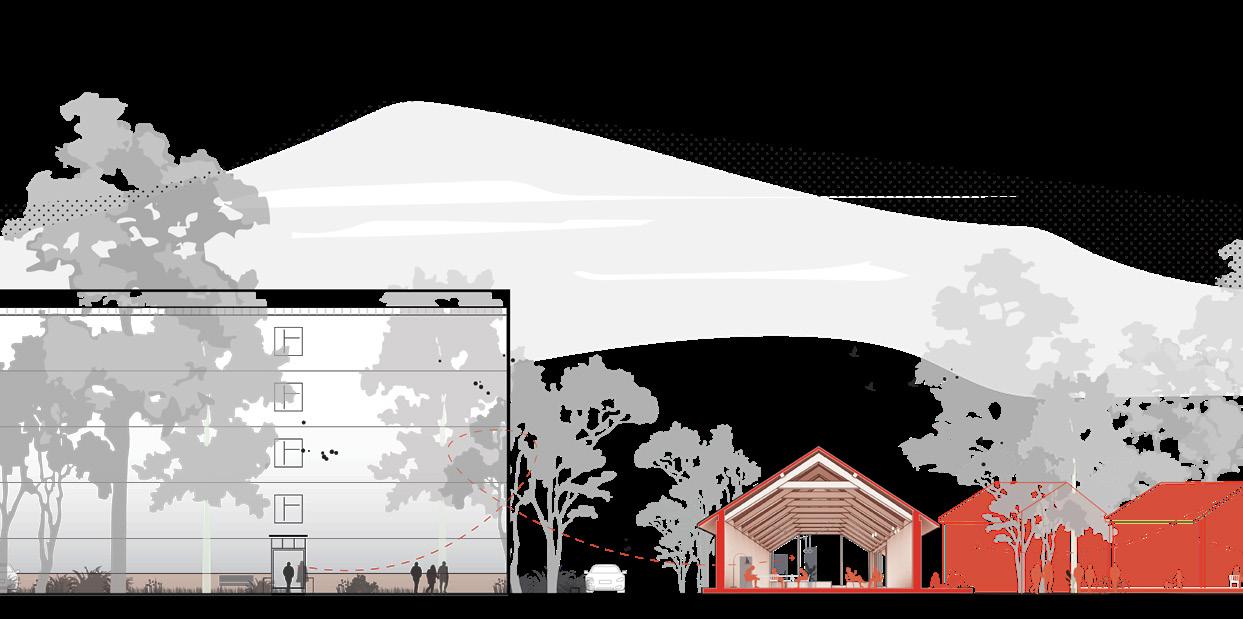

Integration of the programmed design within the urban context – between two blocks

A set of pavilions with multiple functions

The intervention is carefully integrated into the existing urban fabric, positioned between two residential blocks. This placement allows the design to activate underused space, enhance connectivity, and strengthen the sense of community. By situating the function in a transitional zone, it supports both visual permeability and accessibility while respecting the everyday patterns of residents.

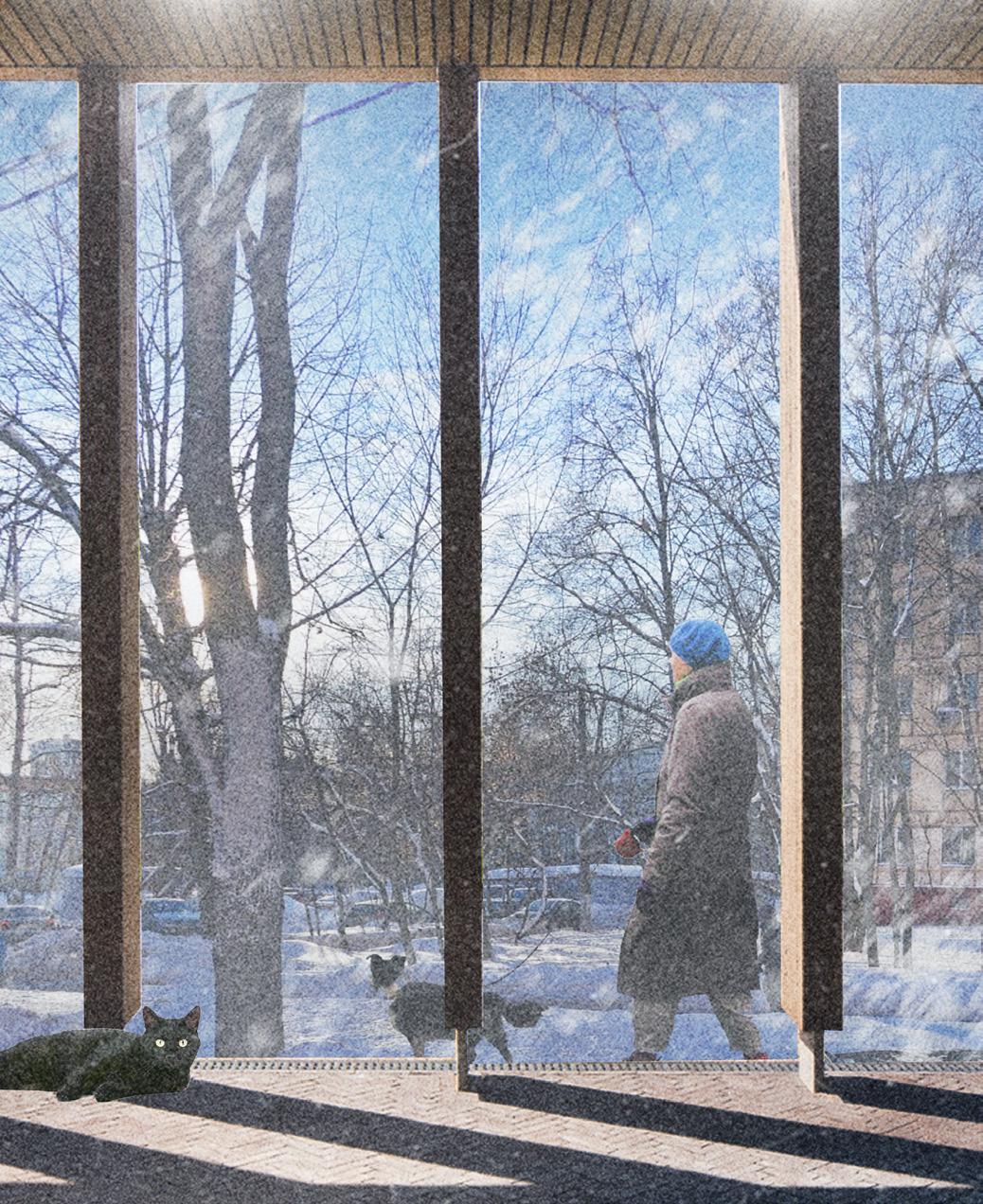

The pavilion invites people in through soft materials, natural textures, and layered transparency. Inside, residents gather around shared tables, relax in reading corners, or host creative sessions. From the outside, façades remain calm and welcoming, creating a sense of familiarity and openness. These everyday scenes define the new social core of the neighborhood.

Integration of the programmed design within the urban context – in the middle of the green space

Stand-alone pavilion in the middle of the green space

The intervention is embedded within the internal green areas of the neighbourhood, where informal paths, tree clusters, and scattered benches already suggest patterns of use. By introducing light structures or functional elements into this context, the design enhances the existing qualities without overwhelming them. It provides residents with accessible, sheltered, and sociable spaces while preserving the natural and calm character of the green zone.

This stand-alone pavilion is embedded in the internal green space of the block, away from the noise of the main roads. It becomes a quiet anchor point within the soft landscape, where everyday life naturally slows down.

From the inside, the pavilion offers a warm and flexible setting. It supports seasonal use — from cozy indoor gatherings in winter to opendoor workshops and shared meals in warmer months. The transparent openings keep the surrounding greenery always present, visually connecting the interior life with the everyday rhythm of the courtyard.

From the outside, the wooden structure blends with the trees and informal gardens. Neighbors passing by or watching from their windows recognize this space as a new heart of the courtyard — one that invites presence, sharing, and care.

Real-life usage projections for the proposed designs. The chapter outlines how spaces will function during different times of day, week, and season, showcasing their flexibility and responsiveness to community rhythms.

The design of the pavilions allows for flexible use depending on time of day, season, or social occasion. Their structure and positioning support a variety of spatial scenarios—from calm, intimate gatherings to full-scale community events. This adaptability ensures their continuous relevance and makes them a lasting part of the everyday urban rhythm.

In colder months, the pavilions offer a warm, enclosed space where residents can gather for film screenings or informal conversations. Use is concentrated indoors, with occasional interactions in the immediate surroundings.

On weekends, the pavilions function as semi-active anchors for the surrounding space. Residents use them for workshops, informal meetings, or café-like gatherings, while the shared open space between the pavilions supports relaxed pedestrian flows and small-scale social interaction.

During national celebrations or neighbourhood events, the pavilion and its surrounding area are activated to their full capacity. The open space hosts communal meals, performances, or markets, turning it into a vibrant social hub.

The implementation of this design follows a step-by-step approach that gradually increases in scale, complexity, and investment. Each phase introduces new spatial qualities and deeper forms of engagement, aligning with the needs

Stage 1

of residents and the evolving character of the neighbourhood. The process is designed to be collaborative, involving a range of local and city-level stakeholders appropriate to each stage.

Stage 2 Evaluation of the doorstep Doorstep

Stage 3 In between blocks

• Local School

Gpvernamental program “My District” • Design students

Local administrative district offices for monitoring and support

• Gov. “Active Citizen” platform collect feedback and promote co-decision

• Gov. “My street” improving pedestrian space

• Urban Competence Center

• Department of Urban Planning and Architecture of Moscow

• Philanthropic organisations

• Social services departments

• Private-public partnerships (PPP) with housing cooperatives or service providers

• Citywide capital renovation

• Developer-led improvement projects

• Green Moscow initiative for sustainable urban upgrades

Year 1 - 2

In the first phase, targeted micro-interventions are introduced at the scale of building entrances. These elements—such as small urban gardens and seating areas—create a sense of ownership and activate social life at the threshold between private and public space. They respond to the challenge of social fragmentation and environmental discomfort by initiating interaction and daily presence. A sense of community begins to form around visible, small-scale improvements.

Year 2 - 3

Through micro-interventions at building entrances— such as gardens and seating—social interaction is sparked at the threshold between public and private. As the design expands to interblock spaces, small pavilions made of natural materials provide shelter for communal meals, workshops, and events. These simple, visible changes reclaim car-dominated zones, support local initiatives, and foster a renewed sense of ownership and belonging.

Year 3 - 4

Larger-scale pavilions are introduced in key spatial voids, following pedestrian flows. These structures support diverse uses such as markets, workshops, and care programs. Their prominent placement along main circulation paths strengthens the spatial identity of the neighborhood and enhances its functional diversity. At this stage, the interventions begin to shift perception of the area, positioning it as a vibrant and evolving part of the city fabric.

Year 5 - 7

The interventions begin to shape new spatial logics across the district. Social and ecological networks become visible and interconnected. With increased pedestrian activity, shared use, and visible community involvement, the area moves toward a more resilient, inclusive, and attractive environment. Urban voids are transformed into active nodes. This phase supports long-term behavioral shifts—reduced isolation, enhanced walkability, and growing resident agency.

This analytical chapter demonstrates how the design addresses six key urban challenges: public-private balance, financial dependence, functional imbalance, identity, leisure dependency, and transport reliance. Each is supported by visual and spatial evidence.

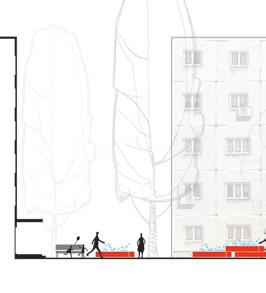

In many peripheral neighborhoods, the transition between public and private space is undefined, leading to neglected thresholds, underused entrances, and low social safety.

Through the implemented spatial interventions, the public-private boundary becomes legible and active. The presence of informal gardens, seating, and programmatic pavilions at key in-between spaces results in increased daily use, passive surveillance, and spontaneous community interaction. These zones no longer serve as leftover or anonymous edges but transform into shared micro-arenas of activity. Residents begin to recognize these spaces as part of their domain, maintaining them, spending time in them, and interacting with neighbors. The interventions prove that carefully articulated public-private thresholds contribute to spatial dignity, security, and a deeper sense of everyday community ownership.

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.

These pavilions serve flexible community needs—hosting workshops, markets, coworking sessions, or care programs for elderly and children. Their function can shift depending on time of day or season, creating a dynamic local hub. Their angled placement ensures visibility from key walking routes and minimizes acoustic disturbance for nearby residents.

Located along the most frequented pedestrian paths, these structures are designed to activate overlooked spaces and provide adaptable rooms for both quiet and social activities—supporting

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.

These pavilions serve flexible community needs—hosting workshops, markets, coworking sessions, or care programs for elderly and children. Their function can shift depending on time of day or season, creating a dynamic local hub. Their angled placement ensures visibility from key walking routes and minimizes acoustic disturbance for nearby residents.

Located along the most frequented pedestrian paths, these structures are designed to activate overlooked spaces and provide adaptable rooms for both quiet and social activities—supporting

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.

These pavilions serve flexible community needs—hosting workshops, markets, coworking sessions, or care programs for elderly and children. Their function can shift depending on time of day or season, creating a dynamic local hub. Their angled placement ensures visibility from key walking routes and minimizes acoustic disturbance for nearby residents.

Located along the most frequented pedestrian paths, these structures are designed to activate overlooked spaces and provide adaptable rooms for both quiet and social activities—supporting

Various changes in the space embracing the local identities

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.

These pavilions serve flexible community needs—hosting workshops, markets, coworking sessions, or care programs for elderly and children. Their function can shift depending on time of day or season, creating a dynamic local hub. Their angled placement ensures visibility from key walking routes and minimizes acoustic disturbance for nearby residents.

Located along the most frequented pedestrian paths, these structures are designed to activate overlooked spaces and provide adaptable rooms for both quiet and social activities—supporting

At this stage of the design, underused or vacant spaces within the neighbourhood are transformed through the strategic placement of accent pavilions. Structures placed at irregular angles to the existing buildings. Their distinct positioning helps form a new frontage and strengthen the transition between public and private space.