FÒGLIE

Mentre completiamo questo numero di Fòglie i riflettori di tutto il mondo si stanno accendendo sulla Puglia e su Borgo Egnazia. Quest’anno la stagione estiva inizia dopo aver accolto uno degli eventi più importanti nel panorama internazionale: il G7.

«Come avete fatto? Come è arrivato il G7 in Puglia?». Non so rispondere a questa domanda. Posso però raccontare l’energia e l’impegno che guidano il nostro lavoro da più di 20 anni per raccontare la Puglia, per accogliere viaggiatori da tutto il mondo, per mettere la nostra regione sulla mappa delle rotte internazionali. Posso raccontare di tutte le persone che hanno creduto in questo progetto e che continuano a crederci, a partire da chi passeggiando tra le vie deserte di Savelletri e delle campagne intorno ha immaginato un campo da golf e una struttura incredibile nel mezzo «del nulla». Posso raccontare di come Masseria San Domenico ha ispirato uno stile di ospitalità di alto livello, di come il lavoro di questi anni ha contribuito attivamente alla crescita della nostra regione e di un sistema virtuoso capace di far crescere un territorio coinvolgendo la comunità locale.

Potrei raccontare tante altre cose, ma preferisco invitarvi a venirci a trovare per scoprire questa terra così generosa attraverso gli occhi di chi la vive, l’emozione di chi la saluta, il calore di chi accoglie.

Seguiteci in questo viaggio, e partite dalle pagine di Fòglie. Noi vi aspettiamo qui, dove tutto inizia.

As we work on this issue of Fòglie, the world’s spotlight is shining on Puglia and Borgo Egnazia. This year, the summer season will kick off after hosting one of the most significant events on the international stage: the G7.

“How did you do it? How did the G7 come to Puglia?”. This is not a question for me to answer, although it is one I am frequently asked. However, I could speak of the energy and dedication that has driven our work for over 20 years to promote Puglia as a destination, to welcome travellers from around the world, and to position our region on the map of international itineraries. I could speak of all the people who believed in this project and continue to do so, starting with those who, while strolling through the deserted streets of Savelletri and the surrounding countryside, envisioned a golf course and an extraordinary hospitality project in the middle of “nowhere”. I could speak of how Masseria San Domenico inspired a special style of high-level hospitality, of how the work of these years has actively contributed to the growth of Puglia as a destination and to the creation of a virtuous system capable of fostering the development of a region by involving the local community.

I could tell you many things, but I prefer to invite you to experience Puglia with us, to discover this generous land through the eyes of those who live here, the emotions of those who visit, and the warmth of those who host.

Join us on this journey, starting right from the pages of Fòglie. We await you here, where it all begins.

Buona lettura!

¬ Aldo Melpignano Co-Owner of Borgo Egnazia

Racconti di Puglia attraverso i luoghi, i riti, le persone e la cultura di questa terra Stories about Puglia through the places, traditions, people and culture of this land

06. A BRACCIA APERTE With Open Arms

14. PLANTS - L’ULIVO

The Olive Tree

16. EXPERIENCE - MI RITORNI IN MENTE

Old Memories Die Hard

18. CONVERSAZIONE IN PUGLIA

Conversation in Puglia

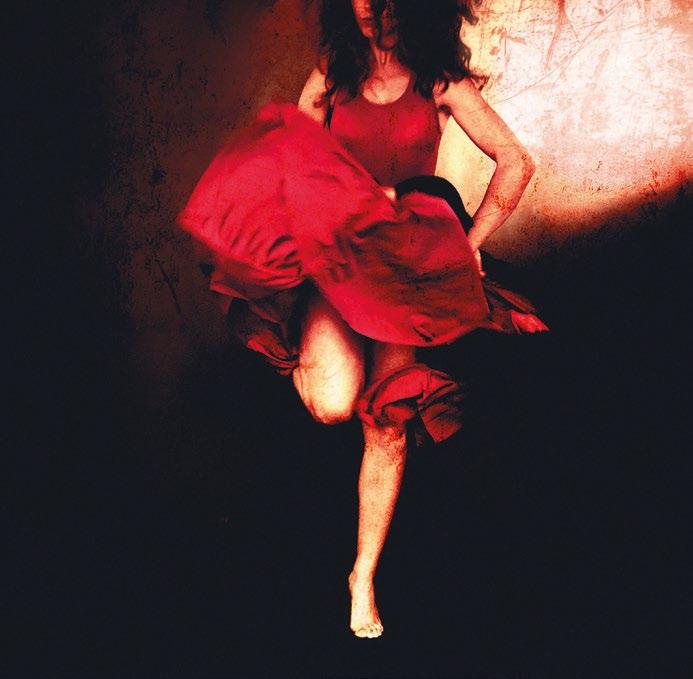

26. TALES - A FÈMN E TÀMBORR

The Lady with the Drum

28. PLACES - QUESTO NON È UN SOGNO

This is no Dream

30. PARLANO LE PIETRE

Let Stones Speak

38. EXPERIENCE - VA DOVE TI PORTA IL VENTO Go with the Wind

40. PLACES - IL PICCOLO EDEN DEI FRUTTI ANTICHI

A Little Eden for Ancient Fruits

42. PLACES - PRATICHE PER UN BUON TURISMO

A Model of Good Tourism

44. UNA DOMENICA SPECIALE

A Special Sunday

50. RECIPES - LA TIELLA BARESE Tiella Barese

52. TASTE - CRUDO DI MARE Raw Seafood

54. CIAK, LA PUGLIA! Lights, Camera, Puglia!

60. PEOPLE - ELOGIO ALLA LENTEZZA Praise to Slowness

62. PEOPLE - COSÌ BELLI CHE VIEN VOGLIA DI MANGIARLI They Look so Good, You’ll Want to Eat Them

64. PLACES - UN GIOCO SERIO Art is a Serious Game

66. MEDITERRANEO SOUND Mediterranean Sound

72. EVENTS - È TUTTA UNA FESTA! It’s All One Big Party!

74. WORDS - LA CRIANZA

Aldo e Camilla Melpignano con le loro figlie Emma e Maria.

Aldo e Camilla Melpignano con le loro figlie Emma e Maria.

¬ Raffaele Panizza

UNA STORIA DI FAMIGLIA, GLI AMICI, LE RADICI

E UN PO’ DI SANA DISOBBEDIENZA ALLE REGOLE.

È L’OSPITALITÀ IN STILE MELPIGNANO

A story of family, friends, roots and a little healthy rule-breaking: this is hospitality in Melpignano style

L’ospitalità è la forma più dolce di follia. Uno slancio in cui si prende il cuore, lo si impacchetta con un nastrino e lo si consegna all’altro, che lo ripone nel suo scrigno e può farne ciò che vuole. Può manifestarsi la mattina presto oppure al momento del dessert, quando una cameriera con gli occhi di attesa, tra le colonne bianche di un ristorante di Borgo Egnazia, si disinteressa soavemente di un rifiuto e con voce tuonante di femminilità dice «insisto». Servendo a tavola, tra cento deboli «no», un gelato al pistacchio sul quale verserà, «insisto…», una generosa lacrima di olio d’oliva.

Perché l’accoglienza, da queste parti, è una forma cortese e ostinata di disobbedienza. «In effetti, qualche licenza poetica sul cerimoniale a cinque stelle ce la prendiamo» dice Aldo Melpignano, che Borgo Egnazia l’ha costruito insieme ai genitori Sergio e Marisa e lo gestisce con la moglie Camilla Melpignano. Milanese. All’inizio scioccata e ora avvezza a questo mondo dove gli uomini sbraitano ma le donne decidono, fatto «di gentilezza e grazia». Incarnate da gesti e attitudini in contrasto con ciò che la vita sembra volerci insegnare: essere guardinghi, calcolare, dare per ricevere, rispettare tempi e gerarchie. E invece ecco: d’un tratto, senza essere dei santi, in nome dei valori e delle generazioni indomite, in Puglia si compie la sacra transustanziazione. L’anima diventa pane. Il sorriso diventa ancora una volta olio extravergine in cui disciogliere succo d’uva e intingere la mollica di grano arso. La memoria si apparecchia a tavola in abbondanza. L’ospitalità non ha antifurti: aprirsi, aprire, preparare senza sapere cosa sarà gradito e cosa no. È un progetto senza certezze, e per questo, per quanto mille volte tradita, non potrà mai essere delusa.

In Puglia ogni cosa sembra insegnartela. La terra rossa dei campi che rimane imperturbabilmente se stessa, ci sia pioggia o ci sia arsura, nutrita dai suoi sali minerali e indifferente alle mode e alle minacce dell’agricoltura irrispettosa che si pratica altrove. In tutta la Piana degli olivi secolari e fino al mare, all’ombra delle fronde trovano posto mille coltivazioni: le patate col loro fiore CONTINUA >

Hospitality is the kindest form of madness. You enthusiastically take your heart, wrap a ribbon around it and give it to someone else so they can take it for themselves and do what they want with it. It can be found in the morning or when it’s time for dessert among the white columns of a Borgo Egnazia restaurant and a waitress with expectant eyes takes no notice of a guest turning it down, saying “Oh no, I insist” in a voice dripping with feminine charm. Paying no heed to countless feeble protests, she’ll serve pistachio ice cream and – “I insist” – generously drizzle olive oil over it.

In this part of the world, hospitality is a polite, stubborn form of disobedience. “It’s fair to say we use a little poetic licence when it comes to five-star etiquette,” says Aldo Melpignano, who built Borgo Egnazia with his parents Sergio and Marisa, and now runs it with his wife Camilla Melpignano, who’s from Milan. She was astonished at first but now she’s grown accustomed to a place where the men might yell but the women make the decisions and “kindness and politeness” prevail. This is all embodied by deeds and behaviour that go against the lessons life seems to want to teach us: be cautious and calculating, give in order to receive, and stick to set times and hierarchies. We might not be saints, but as we act in the name of indomitable generations and values, a type of transubstantiation occurs in Puglia. Our souls take the form of bread. Smiles turn into extra virgin olive oil, waiting for grape juice to be poured into it and soft grano arso bread (made from toasted wheat) to be dipped in it. Tables are set with a multitude of memories. Hospitality means opening up and exposing yourself, with no safeguards: you prepare things without knowing what people will like and what they won’t. You can never know for sure how it’ll all go, so you might be let down endless times, but you can never really be disappointed.

This seems to be the lesson you can learn from every little thing. The red soil in the fields remains imperturbably unchanged through both rain and drought, nourished by its minerals and unconcerned by the fashions and threats of reckless agricultural methods employed elsewhere. Piana degli Olivi Secolari is a plain where age-old olive trees grow. All across it and down to the sea, numerous crops grow in the shade of their foliage:

>

«Quando c’era brutto tempo mi chiedeva: cosa si mangia se piove? E io lo sapevo già: la pasta dei panzerotti, senza lievito, col latte» – Mimina

“When the weather was bad, he’d ask: what should we eat when it rains? I knew the answer: panzerotti dough with milk and no yeast” – Mimina

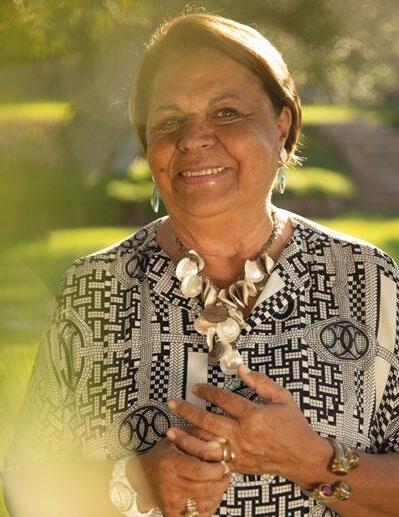

Nella pagina a fianco in alto, Marisa Melpignano. In basso a sinistra, la cuoca Mimina al San Domenico Golf.

On the opposite page, top right, Marisa Melpignano. Bottom left, Mimina at San Domenico Golf.

¬ Ph. Carlos Solito

¬ Ph. Carlos Solito

inatteso, i finocchi la cui pancia tonda spunta dal terreno, il sedano che profuma l’aria di pinzimonio e vellutata, il cavolo nero dalle foglie che sembrano mantelli di generale, la menta pronta per le frittate di pane e uova. Ogni cosa invita a cena l’altra. Ogni cosa è varietà. Sessantadue famiglie di olive. Novantadue cultivar autoctoni di uva. Solo di melanzane, ce ne sono dodici tipi. «E se le nespole cadono dall’albero, chi passa le raccoglie e le offre a un amico», dice Giuseppe Cupertino, molto più che sommelier a Borgo Egnazia. Un uomo che di vino pugliese sa tutto. Ma che non è ancora riuscito a convincere il padre Oronzo ad assaggiare una delle sue bottiglie pregiate: «Il tuo vino te lo bevi tu», gli risponde ogni volta, attaccato come una barbatella ai dieci ettari di uve minutulo e verdeca che coltiva,

imbottiglia, e regala a chi gli pare. «E non è un caso che il Negramaro sia il vino più richiesto al mondo, il più esportato: richiama uno stile di vita, un amore, una terra intera», dice Cupertino versando un calice di Chakra Rosso di Gioia del Colle.

Persino il maestrale che imperversa sulla costa è accolto come buonvento: i tronchi secolari sono tutti inclinati a sud, come a regalargli uno scivolo di fronde e lasciarlo soffiare in pace, e potenziarsi quasi. Quando tira fortissimo vengono innalzati subito gli aquiloni: lo scorso aprile, a guardarli in volo per il festival Zoo Skyline, sui prati di Savelletri si sono raccolte settantamila persone. E in questa follia dell’immaginazione sotto i suoi schiaffi è nato un campo da golf spettacolare, un links voluto dalla famiglia Melpignano

quando qui non c’era nulla, pochi ortaggi e il progetto (altrettanto matto) di realizzare un aeroporto sugli scogli, mentre oggi San Domenico Golf è parte dei circuiti internazionali e sfida la balistica dei giocatori come certi prati sulle Highlands scozzesi.

Rispetto alla Scozia, però, qui è tutto più aspro ma allo stesso tempo tutto più docile. E la consolazione dal vento arriva nelle ricette preparate da Mimina nel ristorante del Golf: gli ziti al forno con l’origano e la melanzana o l’introvabile sartù, un timballo di riso e polpette grandi come un cecio, mozzarella e parmigiano. «L’avvocato Melpignano amava il ragù cotto nel coccio, sui carboni ardenti. Così come nel coccio voleva il pollo, sfumato nel vin cotto che si ottiene dalla prima bollitura del mosto. E CONTINUA >

potatoes with their astonishing flowers, fennel with bulbous bellies protruding from the soil, celery filling the air with aromas that call to mind vegetable dips and soup, cavolo nero with leaves that look like generals’ cloaks, and mint for bread omelettes. Each is a culinary companion for another. Variety can be found in every one of them. There are 62 families of olives, 92 native grape cultivars and even 12 types of aubergines. “And when medlars fall from the tree, passers-by pick them up to give to friends,” says Giuseppe Cupertino, who is much more than just a sommelier at Borgo Egnazia. He knows everything about Puglian wine. However, he still hasn’t managed to convince his father Oronzo to drink one of the bottles from his superior selection. Oronzo makes his own wine from the Minutolo and Verdeca grapes he grows in his ten hectare-vineyards, then gives the

bottles out as presents. “It’s no surprise that Negroamaro’s the wine that’s most in demand worldwide: it calls to mind a lifestyle, love and its homeland as a whole,” says Cupertino as he pours a glass of Chakra Rosso from Gioia del Colle.

Even the Mistral that buffets the coast is welcomed: the trunks of the age-old trees all lean south, almost shaping themselves into leafy launchpads and letting it blow freely, or even get stronger. As soon as the wind gets up, people start flying kites: last April, 70,000 people flocked to the meadows near Savelletri to see them soaring during the Zoo Skyline festival. Where the wind whips the shore, a spectacular links golf course has been built thanks to the folly and fertile imagination of the Melpignano family. Where there was once nothing but a few vegetables growing and plans (that were just as

crazy) to build an airport by the seafront, you can now find San Domenico Golf. Part of international tours, it puts players to the test as much as courses in the Scottish Highlands.

Compared to Scotland, everything here’s more rugged yet more mellow at the same time. The wind will help work up an appetite for the comforting dishes made by Mimina at the golf course restaurant: baked ziti with oregano and aubergines or the elusive sartù, containing rice, mozzarella, Parmesan cheese and meatballs the size of chickpeas. “Mr Melpignano loved ragù cooked in an earthenware pot over hot coals. He also had his chicken cooked in an earthenware pot, in the vin cotto you get by boiling grape must once. When the weather was bad, he’d ask: what should you eat when it rains, Mimina? I knew the answer: CONTINUES >

«Quando il paniere va e viene, l’amicizia si mantiene». Da questa filosofia nasce l'usanza di donare cesti di ciliegie quando l’albero ne regala tante

"When the basket goes back and forth, friendship endures.” This saying in the local dialect refers to the way people give each other cherries when plenty grow on their trees

quando c’era brutto tempo mi diceva: cosa si mangia se piove, Mimina? E io lo sapevo già: la pasta dei panzerotti, senza lievito, col latte. Il pomodoro sì, ma soltanto i semi. E un po’ di parmigiano che si fonde».

Gesti imparati in famiglia e poi offerti a tutti. Come si fa con un papavero selvatico raccolto sul bordo del tratturo tra le campagne di Fasano: la corolla piegata all’ingiù per formare una gonnella, un filo nero di capelli per segnare il punto vita, gli stami a formare una collana e la stimma lasciata come testolina, per creare una bambolina che le bimbe regalavano alle amiche, in un gesto di amicizia mai dimenticato. Lo insegna Clara, che sa tramandare la magia delle cose ancestrali. Il lego per le costruzioni fatto col trifoglio tappezzante. I pupazzi costruiti con le pale carnose del fico d’India. I rosari coi noccioli d’olivo. «Quando il paniere va e viene, l’amicizia si mantiene», dice in dialetto, ricordando l’usanza di donare cesti di ciliegie quando l’albero ne regala tante. Nella sua Alberobello lavora per la memoria anche Mimmo, guida e oste e local friend di Borgo Egnazia, che ha trasformato uno dei suoi trulli in uno scrigno del passato: «Nelle campagne si rifugiavano gli sfollati dalle persecuzioni, e nei trulli abbandonati trovavano riparo i militari stanchi», dice, mostrando gli accendini americani e le pomate tedesche per i dolori, che ha trovato nei pozzi. «Qui ormai arrivano due milioni di visitatori l’anno, ma come dico io, essere carini coi turisti è fin troppo facile. È quando non hai nulla, e ugualmente dai, che il gesto ha davvero valore. E noi, con le braccia aperte, siamo sempre stati».

panzerotti dough with milk but no yeast. Tomatoes were OK, but only the seeds. And a little melted Parmesan.”

We learn these things at home and then share them with everyone. For example, when you pick a wild poppy growing by a tratturo (sheep track) in the Fasano countryside, you can make a doll by folding the petals down to make a skirt, wrapping a little black hair around the waist, shaping the stamens into a necklace and leaving the stigma as a head. Girls used to give them to each other, in unforgettable shows of friendship. It’s one of the things taught by Clara, who helps to pass down magical ancestral marvels. Clover can be used to make building blocks. The fleshy pads of prickly pears can be made into dolls. You can create rosaries with olive stones. “When the basket goes back and forth, friendship endures”, is a saying in the local dialect referring to the way people give each other cherries when plenty grow on their trees. Mimmo also keeps memories alive in his home town of Alberobello. A guide, host and local friend of Borgo Egnazia, he’s turned one of his trulli into a historical treasure trove: “Displaced people fleeing persecution sought refuge in the countryside and tired troops found shelter in abandoned trulli,” he says, showing American lighters and German pain-relieving ointments he’s found in wells. “We get two million visitors a year here now, but I always say there’s nothing easier than being nice to tourists. It’s when you have nothing but you still give that it really means something. And we’ve always been here with open arms.”

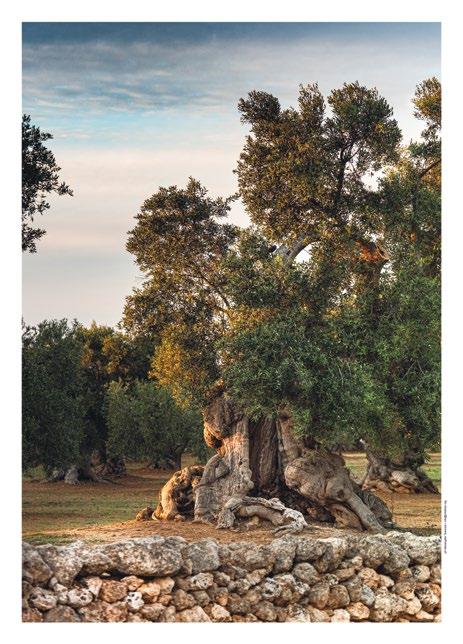

Around this tree, a symbol of peace and of Puglia, with its centuries-old and even millennia-old specimens, rituals, stories, and handmade objects have created with patience and passion

L’ulivo mi ricorda mio padre. Il senso di pace e libertà che provavo quando raccoglievamo insieme le olive è indelebile. Ogni anno, agli inizi di novembre, gli chiedevo: «Babbo, quando iniziamo la raccolta?» «Qualche altro giorno ancora, e si possono raccogliere», rispondeva.

E al momento giusto, stendevamo le reti sotto gli alberi, appoggiavamo lunghe scale di legno alle fronde, e cominciavamo la raccolta a mano, che durava quindici giorni. Lui ed io, da soli. Per ore, ascoltavamo il suono delle olive che cadevano, colpendo i pioli e i rami sottostanti prima di raggiungere il terreno. Non fiatavamo, per non perdere neanche una nota di quella sinfonia.

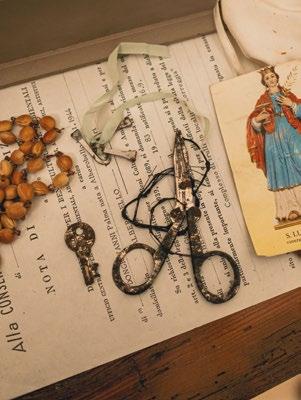

La passione di mio padre per gli ulivi non si limitava alla raccolta ma continuava tutto l’anno. Con i noccioli infilava coroncine di rosario, bracciali, collane, tende per porte e finestre. Ogni anno, ne faceva almeno una che poi donava a parenti e amici. Lo guardavo con ammirazione mentre limava e assemblava i noccioli. Mi trasmetteva un profondo senso di pace. Una volta ho contato quanti ce ne fossero in una delle sue tende: erano 15.000.

«Ma Babbo chi ti dà tutta questa pazienza?»

«È una cosa bella che mi ha insegnato nonno Giuseppe quando ero piccolo! Mi rilassa».

Nonno sapeva fare tante cose con l’ulivo, dai cesti realizzati con i polloni ai cucchiai in legno che si usavano per mescolare la purea di fave. Ricordi e manufatti che conservo gelosamente.

Solo ora comprendo quanto tutto ciò sia in grado di trasmettere un profondo senso di pace. Ripetere i gesti, le tecniche e le lavorazioni che vedevo fare a mio padre mi riporta alle mie radici, e mi emoziono pensando a quanti secoli abbiano attraversato queste usanze, tramandate di generazione in generazione. Di padre in figlia.

Olive trees remind me of my father. The sense of peace and freedom I felt when we gathered the olives together is unforgettable. Each year in early November, I would ask him, "Dad, when do we start harvesting?"

"A few more days and they can be picked," he would reply.

And at the right time, we would spread the nets under the trees, lean tall wooden ladders against the branches, and begin the hand-harvesting that lasted fifteen days. Just the two of us. For hours, we would listen to the sound of the olives as they fell, striking the ladder rungs and branches below before reaching the ground. We didn’t utter a word, so as not to miss a note of that symphony.

My father’s passion for olives was not limited to harvesting but continued throughout the year. With the pits, he made rosary crowns, bracelets, necklaces, and curtains for doors and windows. Every year he made at least one, which he then gave away to relatives and friends. I watched him with admiration as he filed and assembled the pits. He conveyed a deep sense of peace. Once, I counted how many there were in one of his curtains: there were 15,000.

“But Dad, where did you get all this patience from?”

“It's a beautiful thing that Grandpa Giuseppe taught me when I was a child! It's relaxing.”

Grandpa knew how to do many things with the olive tree, from baskets made from shoots to wooden spoons used to stir fava bean puree. Memories and artifacts that I jealously save.

Only now do I understand how much all this can convey a deep sense of peace. Repeating the gestures, techniques, and processes that I saw my father perform brings me back to my roots and moves me, thinking of how many centuries these customs have been passed down from generation to generation. From father to daughter.

Old Memories Die Hard

¬ Sara MagroAt Borgo Egnazia, a cultural association has been established that revives and breathes new life into ancient arts, bringing them into the present

Eh già, le tradizioni. A parole ci teniamo tutti, ma poi le contingenze, la quotidianità, la fretta ce le fanno spesso tralasciare. E ci dispiace. Quasi a tutti dispiace, perché nei confronti del passato e di quel che si faceva vige sempre una certa nostalgia, un desiderio di trattenerle e mantenerle. Conserviamo una coperta della nonna in un cassetto, le lettere d’amore, il suo abito da sposa ancora piegato nella scatola originale, con le scritte sbiadite. E ogni tanto tiriamo fuori quei cimeli, li raccontiamo e poi riponiamo tutto dov’era. Ma la tradizione non si può mettere al museo, bisogna farla vivere. Ci vuole un nuovo pensiero, un nuovo vocabolario e una nuova sede. Da queste riflessioni, nel 2023, è nata Clara, l’associazione di Borgo Egnazia che recupera e riporta in vita le arti antiche.

Ah, traditions. We all say we care about them, but then circumstances, everyday life, and haste often make us overlook them. And we regret it. Almost everyone regrets it, because there is always a certain nostalgia for the past and what was done, a desire to hold on to and keep the traditions alive. We keep a grandmother's blanket in a drawer, love letters, her wedding dress still folded in the original box with faded notes. And occasionally we take out these relics, talk about them, and then put everything back where it was. But tradition cannot be kept in a museum; it must be brought to life. It takes new thinking, a new vocabulary, and a new home. These considerations led in 2023 to the birth of Clara, the association of Borgo Egnazia that recovers and revives ancient arts.

Le radici per Borgo Egnazia coincidono con le fondamenta stesse della sua struttura. Non c’è pietra o idea che non sia stata ispirata dalla storia scritta sui libri o raccontata. Le case, le corti, i colori, le vestine, la cucina. Il borgo è cresciuto insieme alle sue feste, dove si insegue il profumo delle bombette, si fotografa il cestaio che intreccia polloni d’ulivo, si balla insieme ai musicisti come se si fosse cresciuti con la pizzica nel sangue. Ecco in quel momento, per una magia intangibile, diventiamo tutti pugliesi.

Non basta più esporsi davanti al forestiero o ai giovani con il proprio fardello di storia, bisogna far breccia nel presente. Come l’upcycling innovativo delle sorelle Canfora che trasformano vecchi corredi in splendidi vestiti di pizzo. O come fanno gli artigiani quando infilano noccioli di ulivo o legumi secchi per fare collane da portare con l’orgoglio di un gioiello prezioso. Le tradizioni vivono di condivisione, piacere e stupore quotidiano. Si devono respirare nell’aria, toccare sui muri, portare come stemmi di un casato nobile. Ma devono fare innamorare e ingolosire, come un tarallo friabile che oggi può avere persino ingredienti migliori di una volta. Il nome non cambia, la ricetta nemmeno, ma corrisponde al presente, si addenta e non si evoca. Difficile dimenticare il sapore di un panzerotto croccante e filante. Quel panetto morbido caldo come un ventre materno ha il potere di insinuarsi nella memoria e diventare l’oggetto di una caccia al tesoro mentale finché non lo si ritrova. Forse per questo la Puglia è diventata una meta dove andare ma soprattutto dove tutti vogliono tornare.

associazioneclara.org

I bauli delle nonne custodiscono i tesori più preziosi.

Grandmothers' trunks hide the most precious treasures.

The roots for Borgo Egnazia coincide with the very foundations of its structure. There is not a stone or an idea that was not inspired by the history written in books or passed down orally. The houses, the courtyards, the colours, the clothing, the cuisine. The village has grown together with its festivals where you can follow the scent of bombette - a typical Puglian meat dish -, photograph the basket weaver intertwining olive shoots, dance together with musicians as if you grew up with the pizzica in your blood. Here, in that moment, by some intangible magic, we all become Puglians.

It's no longer enough to present ourselves to foreigners or the young with our own history; we must break into the present. Like the innovative upcycling of the Canfora sisters who transform old linens into beautiful lace dresses. Or as artisans do when they string olive pits or dried legumes to make necklaces worn as proudly as precious jewels. Traditions thrive on sharing, pleasure, and everyday wonder. They must be breathed in the air, touched on the walls, worn like the crests of a noble house. But they must also enchant and tempt like a crumbly tarallo that today might even have better ingredients than before. The name doesn't change, and neither does the recipe, but a tarallo adapts to the present, is savoured, not just evoked. It’s hard to forget the taste of a crispy, melty panzerotto. That soft, warm dough, like a maternal belly, has the power to seep into your memory and become the object of a mental treasure hunt until it is found again. Perhaps that's why Puglia has become a destination not just to visit, but a place everyone wants to return to.

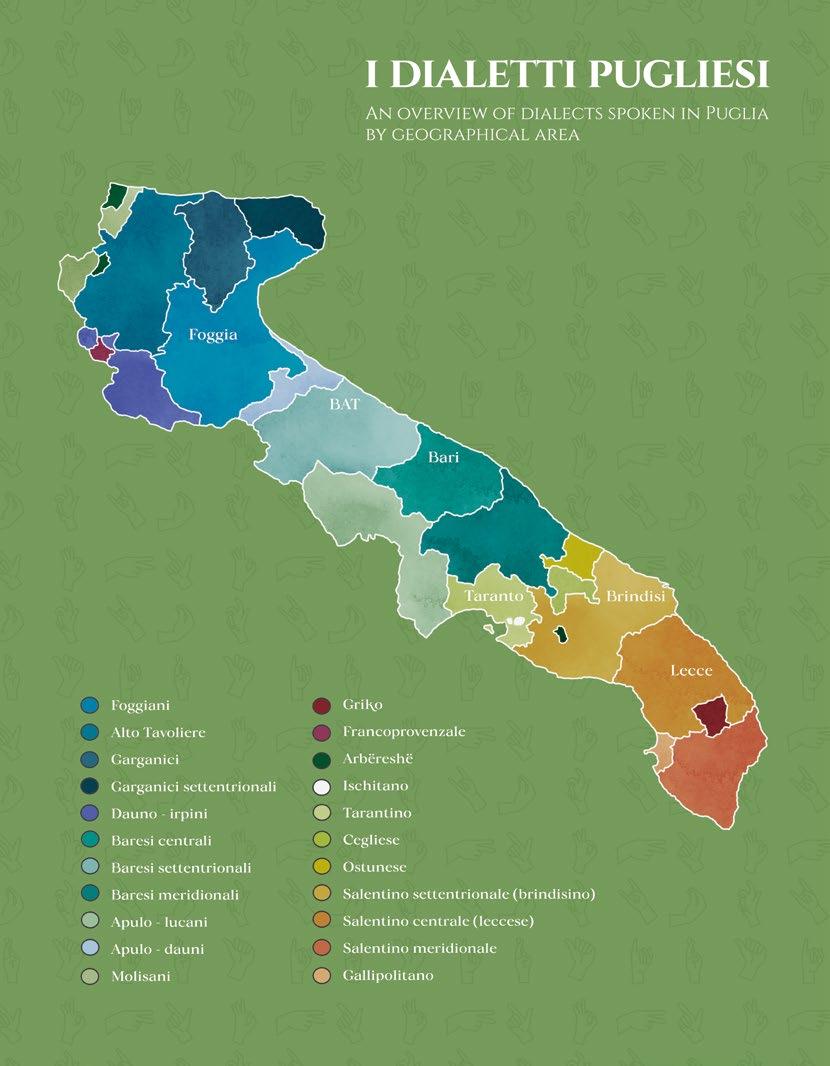

A OGNI MANCIATA DI CHILOMETRI

The story, words and pictures of a universally different language that changes every few kilometres

I dialetti, ed è doveroso l’uso del plurale, sono un patrimonio preziosissimo della Puglia e dell’Italia intera, riconosciuta come la nazione europea dove se ne contano di più. Analizzando i dialetti pugliesi, emergono alcune peculiarità fonetiche che, tra un sorriso e una risata, generano legittime domande. E qui proviamo a dare qualche risposta con l’autorevole aiuto del professore Marcello Aprile, ordinario di Linguistica italiana all’Università del Salento, esperto anche di dialettologia e minoranze linguistiche etniche e religiose.

È tutta una questione di aree ed è utile individuarle tracciando una linea immaginaria che passa poco sopra la città di Brindisi, attraversando Oria e Manduria. Possiamo subito distinguere il dialetto pugliese, convenzionalmente citato come «quello del Nord», da quello salentino. E qui si chiama in causa la ripartizione territoriale del Regno di Napoli: la Terra d’Otranto a Sud, la Terra di Bari a Nord, la Capitanata e poi il Gargano ancora più su. Che le dominazioni abbiano influito notevolmente sui dialetti pare un fatto scontato.

Su una mappa proviamo a individuare le aree accomunate da alcune peculiarità dialettali. Possiamo farlo, ma è pura convenzione, perché la realtà è molto più complessa e articolata: ogni singolo paese, se non addirittura frazione, ha un proprio dialetto con innumerevoli caratteristiche che lo rendono unico. È come se i nove chilometri che dividono, per esempio, Oria da Latiano fossero un viaggio compiuto dalle parole, che arrivano a destinazione vestite di nuovi suoni e a volte anche di inediti significati. Ogni centro italiano ha

CONTINUA >

Dialects – and use of the plural form is essential here – are an invaluable part of the heritage of Puglia and the whole of Italy, which is acknowledged to have more of them than any other European country. Analysis of Puglian dialects reveals a number of phonetic peculiarities that are not only amusing in some cases, but also raise interesting questions. Below, we’ll try to answer some of them with the authoritative help of Marcello Aprile, full professor of Italian Linguistics at the University of Salento, who is also an expert on dialectology and ethnic and religious linguistic minorities.

It’s all a matter of areas and it can be useful to mark them out by drawing an imaginary line running just above Brindisi, through Oria and Manduria. The first thing we can do is distinguish between the Puglian dialect – conventionally referred to as “the dialect of the North” – and the Salento dialect. It’s important to note here how the Kingdom of Naples was divided: Terra d’Otranto in the South, Terra di Bari in the North, Capitanata and then above that Gargano. It seems clear that the divisions by the rulers had a significant impact on the dialects.

On a map, we could try to pick out areas that share certain dialectal peculiarities. However, it would be a purely conventional exercise because things are actually much more complex and intricate: every single village – or even hamlet – has its own dialect, with countless characteristics that make it unique. For example, it’s as if the words themselves go on a journey over the 9 km between Oria and Latiano. When they arrive, they have new sounds and sometimes even brand new meanings. Every village, town and city in Italy has a dialect that varies slightly from that of its neighbours, with CONTINUES >

Il dialetto non è una storpiatura dell’italiano, ma un'evoluzione del latino parlato in una certa zona

Dialects are not mangled forms of Italian: they actually evolved from the Latin that was once spoken in different areas of the country

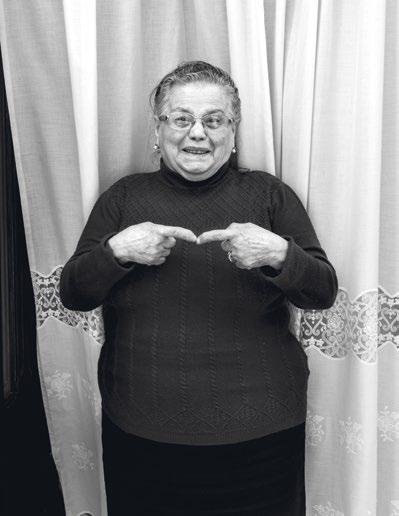

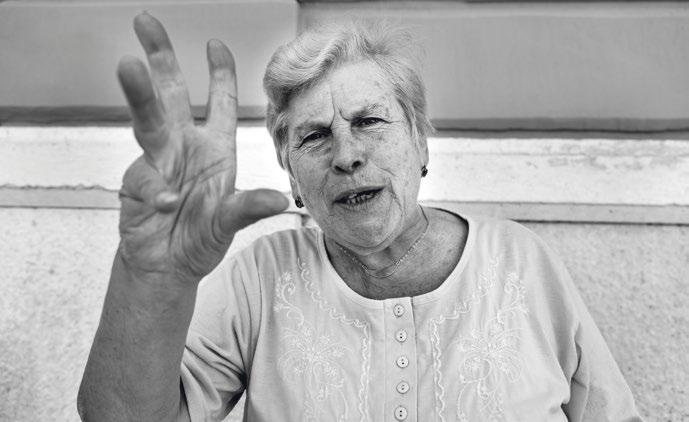

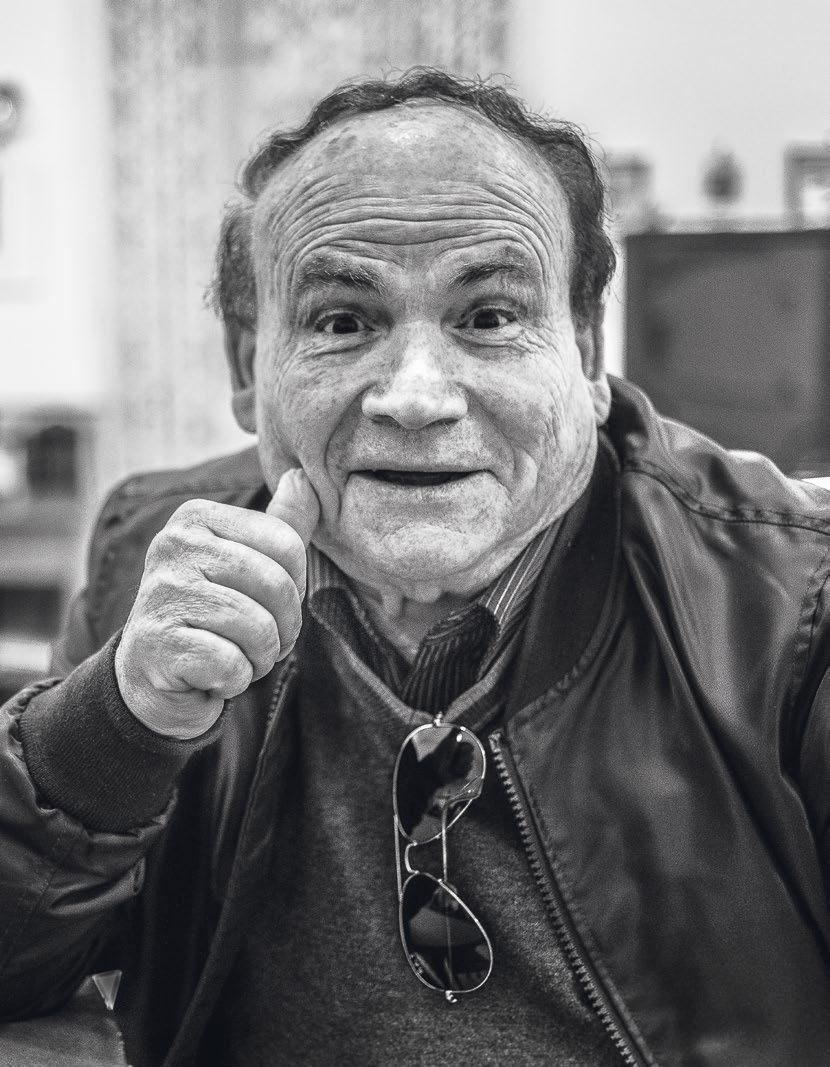

Ogni pugliese sa esprimere un ricco vocabolario dialettale in un solo gesto.

Every Puglian is capable of expressing a rich array of dialectal terms with a single gesture.

un dialetto leggermente diverso da quello dei vicini, per più nitide o impercettibili sfumature.

Si cade spesso nell’errore di pensare che il dialetto sia una storpiatura dell’italiano, ma il professor Aprile spiega come in realtà sia un’evoluzione del latino, parlato un tempo nelle diverse zone. Le origini del dialetto milanese andranno ricercate nel latino parlato in Lombardia duemila anni fa, così come il dialetto di Ancona sarà in relazione al latino parlato nelle Marche… e via discorrendo, per ogni città o paese. Anche il fiorentino nasce come evoluzione del latino con cui si conversava a Firenze, per poi diventare la nostra lingua, a seguito di fenomeni politici e culturali, tra cui in primis l’unificazione italiana.

Strettamente legata ai dialetti è la tematica delle minoranze linguistiche, tanto diverse eppure radicalmente affini al vernacolo. All’argomento, il professore Aprile riserva il comprensibile entusiasmo di chi affonda le proprie radici familiari nella comunità grika di Calimera, capace di evocare storie di popoli lontani. Emblema di un’atavica multiculturalità, la tutela delle minoranze linguistiche presenti sul territorio italiano è, va ricordato, prevista all’articolo 6 della nostra Costituzione.

Cotanto riconoscimento, in Puglia, trova espressione nel programma straordinario Matria. Le lingue di ieri, di oggi, di domani, dedicato alla tutela e alla valorizzazione delle

some differences that are clear and others that are barely perceptible.

People often make the mistake of thinking that dialects are mangled forms of Italian, but Professor Aprile explains that they actually evolved from the Latin that was once spoken in different areas. The origins of the Milanese dialect can be found in the Latin that was spoken in Lombardy 2000 years ago. The same applies to the dialect of Ancona and the Latin spoken in the Marche and so on, for every city, town and village. Italian itself comes from Florentine, which evolved from the Latin spoken in Florence and then became the national language due to various political and cultural factors, first and foremost the unification of Italy.

There are close ties between dialects and linguistic minorities, which are so different yet fundamentally akin to the vernacular. It’s a topic about which Professor Aprile is understandably enthusiastic, given his family’s roots in the Griko community of Calimera, which conjures up stories of distant peoples. As emblems of atavistic multiculturalism, it’s worth noting that the linguistic minorities in Italy are protected by Article 6 of the Italian Constitution.

In Puglia, this protection takes concrete form in a special initiative called ‘Matria. Le lingue di ieri, di oggi, di domani’, (Motherland: the languages of yesterday, today and tomorrow), which safeguards and promotes the area’s

> CONTINUES >

In un attimo ci si ritrova immersi in un codice linguistico indipendente e unico, dove le mani che si muovono servono per spiegare una parola o un’espressione

You can suddenly find yourself immersed in an independent, unique linguistic code, with hand movements being used to explain words or expressions

tre minoranze storico-linguistiche del territorio: la francoprovenzale, l’arbëreshë e la grika.

Territorialità, tono di voce, espressioni e cadenza sono caratteristiche identitarie dei nostri dialetti, tanto quanto, però, la gestualità, che merita un ulteriore approfondimento.

Parole e gesti sono interconnessi tra loro. La gestualità accompagna il linguaggio parlato, arrivando talvolta a sostituirlo, scandisce il ritmo di una conversazione e dà enfasi anche al non detto. Il movimento delle mani a corollario di un discorso è strumento proprio di innumerevoli culture, che curiosamente prescinde dalla lingua o l’età dei soggetti. In Puglia, per esperienza personale, è fortemente radicato l’uso dei gesti a corredo del linguaggio, una tendenza che diventa imprescindibile quando per comunicare si utilizza il dialetto.

three historical linguistic minorities: Franco-Provençal, Arbëreshë and Griko.

As well as territoriality, tone of voice, expressions and cadence, another equally important identifying feature of our dialects that deserves to be examined in more detail is use of gestures.

Words and gestures are interlinked. Gestures accompany spoken language and sometimes even replace it, while also setting the tempo of conversations and emphasising things, including some that go unsaid. Movement of the hands to complement speech is a tool used by countless cultures. Interestingly, this is true regardless of the age and the language of the speaker. From personal experience, I know that use of gestures alongside words is well established in Puglia. It’s essential when people talk in dialect.

There’s a dialect in every village and a gesture for every phrase in every dialect. You can suddenly find yourself immersed in an independent, unique linguistic code, with hand movements being used to explain words or expressions not only to foreigners from distant

Un dialetto per ogni paese, un gesto per ogni frase di quel dialetto. In un attimo ci si ritrova immersi in un codice linguistico indipendente e unico, dove le mani che CONTINUA > CONTINUES >

Dove le parole non arrivano, si ascolta con gli occhi.

When words are not enough, you listen with your eyes.

si muovono servono per spiegare una parola o un’espressione, non solo allo straniero che arriva da luoghi lontani, ma anche al conterraneo che vive in una provincia poco distante. Come le parole così i gesti sono convenzionalmente riconosciuti e passeggiando per le vie di Bari vecchia, come per quelle di Brindisi, non si sarà colti impreparati davanti a una mano chiusa a cono, che ondeggia verso l’alto, in risposta a uno sguardo furtivo.

Il dialetto ha mille sfumature, caratteristiche e inclinazioni, ha una sua autonomia e una storia affascinante, che non si limita all’indagine di questioni meramente geografiche, ma coinvolge aspetti legati all’essere umano e alla sua identità. Scoprire un dialetto dà la possibilità di valorizzare aspetti culturali importanti, imparare a parlarlo offre l’opportunità di preservarli.

lands, but also to compatriots from a different province just a short distance away. Like words, gestures are conventionally recognised, so when people are strolling around the streets of old Bari or Brindisi, they won’t be caught unprepared if they see a hand closed into a cone shape and swaying upwards in response to a furtive glance.

Dialects have countless nuances, characteristics and inclinations. They are independent and they have fascinating stories, which go beyond research into purely geographical matters and involve aspects associated with human beings and their identities. Discovering a dialect opens up the possibility of promoting important facets of culture. Learning to speak it presents the opportunity to preserve them.

Le foto in bianco e nero di questo reportage sono tratte da "Capissce a mmè?", un progetto sulla gestualità barese di Anna Simi. Dopo il debutto nel 2014 con una mostra a Bari, nel 2017, il suo racconto è diventato libro, ora tradotto anche in inglese (Claudio Grenzi Editore).

«Le tradizioni e la saggezza popolare sono un patrimonio nascosto e custodito tra i vicoli di Bari Vecchia, in passato zona off limit, dove atteggiamenti e gesti antichi sono sopravvissuti grazie ai racconti tramandati dai familiari», spiega la fotografa. «Il vero barese può comunicare senza parole, ed è questo che mi ha spinto a studiare i loro gesti, scoprendo storie e sfumature inaspettate». Con le sue foto, Simi ha documentato un vocabolario dialettale alternativo fatto di manualità e mimica facciale, compiendo una straordinaria indagine culturale ed etimologica approfondita sulla Bari popolare.

The black and white photographs featured in this article are from Capissce a mmè?, a project on hand gestures by Anna Simi. Her visual narration made its debut in 2014 with an exhibition in Bari and was published as a book in 2017, translated into English (Claudio Grenzi Editore).

“Traditions and folk wisdom are a heritage that has been hidden and safeguarded for years in the alleys of a once off-limits Bari Vecchia, the Old Town, where ancient mannerisms and gestures have survived through stories passed down by family members,” Simi explains. “Baresi” can communicate without words, and that’s what led me to explore their use of gestures, uncovering unexpected stories and nuances.” With her photographs, Simi has documented an alternative dialectal vocabulary made up of hand gestures and facial expressions, carrying out an extraordinary cultural and etymological investigation of the people of Bari.

The Lady with the Drum

¬ Alessia Bologna

C'ERA UNA VOLTA UNA DAMA CON IL TAMBURO... QUESTA LEGGENDA ANTICHISSIMA SI RACCONTA ANCORA COME SIMBOLO DI ETERNO AMORE

Once upon a time there was a lady with a drum... This ancient legend is still told as a symbol of eternal love

Quando gli spagnoli giunsero in Puglia, affidarono il feudo di Monopoli a uno dei loro più valorosi condottieri. L’uomo, di bell'aspetto e fiero, passeggiava tra vivaci vicoli, quando incontrò una giovane monopolitana che conquistò il suo cuore con un solo sguardo. I due, travolti dalla passione, si sposarono e fecero del maestoso Castello di Carlo V la loro dimora, un nido d'amore sospeso tra cielo e mare.

Il condottiero trascorreva molto tempo navigando lontano dalle rive e, nelle giornate burrascose, la moglie era solita suonare un tamburo che, con il suo richiamo, gli indicava la via di casa, assicurandone l’approdo.

Sembrava un giorno come tanti quando, come di consueto, il condottiero salpò. Aveva lasciato la costa da diversi giorni, quando la dama iniziò a suonare il tamburo, che con il suo serrato ritmo, invitava la nave a far ritorno. Le stanche mani della giovane continuarono a percuotere a lungo, alimentate dalla speranza di poter riabbracciare il marito.

Oggi, nel castello che fu un tempo dimora degli sposi, il suono del tamburo riecheggia nelle giornate di tempesta. È un richiamo per le navi che continua a risuonare, guidando le imbarcazioni in difficoltà verso il porto sicuro, un'eco di un amore che sfida l'eternità.

When the Spaniards arrived in Puglia, they entrusted the feud of Monopoli to one of their most valiant commanders. The proud, handsome man was walking through the lively alleys of the town when he met a young woman who captured his heart with a single glance. Overwhelmed by passion, the two married and made the majestic Castle of Charles V their home—a love nest suspended between sky and sea.

The commander spent much time sailing away from the shores, and on stormy days, his wife would play a drum whose call would guide him home, ensuring his safe landing.

It seemed like any other day when, as usual, the commander sailed out. He had been away from the coast for several days when the lady began to play the drum, its urgent rhythm beckoning the ship to return. The young woman's weary hands continued to beat for a long time, fuelled by the hope of embracing her husband again.

Today, in the castle that was once a home of lovers, the sound of the drum echoes on stormy days. It is a call for ships that continues to resonate, guiding vessels in distress towards a safe harbour, an echo of a love that transcends time.

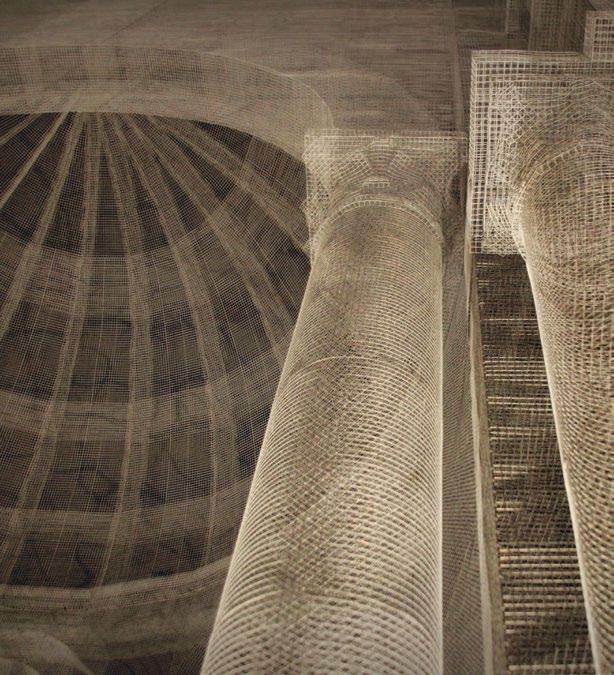

This is No Dream

¬ Oronzo Rubino ¬ Ph. Giacomo PepeLA BASILICA DI SIPONTO RINASCE GRAZIE A UN’OPERA D’ARTE CONTEMPORANEA CHE REINTERPRETA L’ARCHEOLOGIA E PROPONE UN MODELLO INNOVATIVO DI RESTAURO CLASSICO

The Basilica di Siponto has been resurrected by a contemporary artwork that reinterprets archaeology and introduces an innovative model of classical restoration

Da lontano sembra una proiezione in video-mapping creata con raggi laser e droni. Poi, avvicinandosi, ci si rende conto che non è realtà aumentata bensì un monumento maestoso e concreto. La Basilica di Siponto è lì davanti agli occhi, immagine tangibile di una chiesa paleocristiana di cui restano solo i ruderi. Un’opera emozionante dal titolo evocativo – Dove l’arte ricostruisce il tempo – realizzata nel 2016 da Edoardo Tresoldi all’interno del Parco archeologico di Siponto, piccola località vicina a Manfredonia che fino al XIII secolo era una delle più importanti diocesi pugliesi.

Sulle fondamenta della basilica, una superficie di 500 metri quadrati con abside al centro e mosaici sul pavimento, l’artista milanese ha montato una struttura alta 14 metri costituita da 4.500 metri di rete metallica, creando così un’impalcatura onirica nella quale i visitatori possono rivivere l’architettura del IV secolo, come se ancora esistesse. Un’innovativa rilettura dell’archeologia che unisce lo sviluppo del restauro classico e arte contemporanea.

Attraversare l’installazione lascia col fiato sospeso. La sensazione di meraviglia cresce al tramonto, soprattutto in estate, quando il cielo inizia a sfumarsi di rosa e arancione fino a diventare notte. In quel momento, si accendono i proiettori led sul pavimento, che mettono in evidenza la trasparenza tridimensionale dell’installazione e il contorno della basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore al suo fianco, una delle opere più importanti del romanico pugliese, ancora intatta nei suoi volumi essenziali. Impossibile non restarne catturati.

From afar, it may look like a video-mapping projection crafted with laser beams and drones. On closer inspection, it reveals itself not as augmented reality but as a majestic physical monument. The Basilica di Siponto stands before you, a tangible representation of an early Christian church of which only ruins remain. This awe-inspiring work of art, evocatively titled "Dove l’arte ricostruisce il tempo" (Where Art Rebuilds Time), was crafted in 2016 by Edoardo Tresoldi within the Archaeological Park of Siponto—a small town near Manfredonia that was one of Puglia’s most important dioceses until the 13th century.

On the basilica's foundations, covering an area of 500 square metres with a central apse and a mosaic floor, the Milanese artist erected a 14-metre-high structure made of 4,500 metres of wire mesh, creating a dreamlike scaffold where visitors can relive the fourth-century edifice as if it still stood. This innovative reinterpretation of archaeology melds the development of classical restoration with contemporary art.

Walking through the installation takes your breath away. The feeling of wonder intensifies at sunset, especially in summer, when the sky starts to blush pink and orange before nightfall. At that moment, LED projectors illuminate the floor, accentuating the installation's three-dimensional transparency and the outline of the adjacent Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore—one of the most significant works of Puglian Romanesque architecture, still intact in its essential forms. The experience is truly captivating.

¬ Elena Luraghi ¬ Ph. Cosimo Rubino & Simone Valenzano

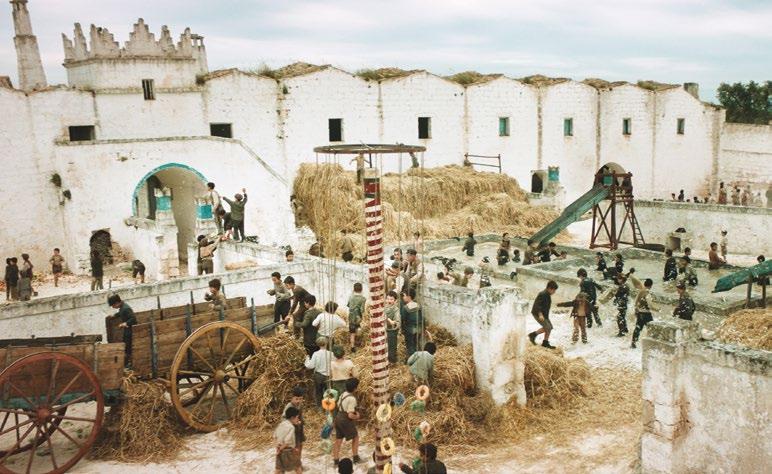

LA VITA RURALE, LE ARCHITETTURE COSTRUITE SUI BISOGNI DELLA QUOTIDIANITÀ, GLI INCONTRI E LE FESTE IN PIAZZA. ECCO COME È NATO UN PROGETTO INNOVATIVO E ORIGINALE GUARDANDO NEL PASSATO TRA MASSERIE, TRULLI E PICCOLI VILLAGGI

Rural life, architecture built to suit everyday needs, gatherings and parties in the piazza. An innovative, original project was inspired by a look back into the past, at masserie, trulli and small villages

A Borgo Egnazia, i muri in tufo

Borgo Egnazia, a place where pale stone walls meet the bright colours of the Puglian countryside.

chiaro risaltano sui colori accesi della campagna pugliese.Erano umili costruzioni rurali, i gioielli dell’architettura pugliese: una manciata di stanze vicino al fienile, il ricovero per gli animali, i depositi destinati al raccolto dei campi e i trappeti (i frantoi ipogei), cresciuti attorno alla villa nella quale viveva il proprietario terriero, secondo la regola un tempo diffusa della mezzadria.

Le masserie erano un mondo a sé, un sistema di comunità agricola che viveva in armonia con il clima, la luce, il sole, la terra: elementi fondamentali per lo sviluppo di quella magia architettonica composta da muri bianchi e cortili, porticati dalle volte in tufo o rivestite a calce, abbracciati da torri di avvistamento ed elementi difensivi realizzati a protezione dalle invasioni, soprattutto dopo gli attacchi turchi nella seconda metà del XV secolo.

Costruite con il tufo e la pietra calcarea, materiale facilmente reperibile nelle cave pugliesi, e sature di sole e di luce, le masserie affiancavano gli jazzi (i recinti in pietra a secco, ndr) agli spazi residenziali dalle geometrie elementari. Le proprietà più grandi potevano avere la cisterna per la raccolta dell’acqua e, a partire dal SetteOttocento, la chiesetta nella quale officiare messa alla domenica.

Al centro della tenuta, il cortile era allo stesso tempo aia per gli animali e spazio d’aggregazione sociale, in risposta al bisogno molto umano di vivere in comunità all’interno di un ambiente difeso e protetto. Qui si cuoceva il pane, si filava la lana, si ricamava, si macinavano lavoro e storie. E nelle sere d’estate i canti popolari della tradizione contadina si disperdevano in lontananza nella campagna, mescolandosi con il frinire dei grilli e delle cicale.

Alla vita rurale legata alla terra da coltivare si affiancava quella nel borgo di origine medievale: anche questo un mondo bianco, con le pareti delle case ammantate a calce e i vicoli stretti per proteggersi dal sole, arrotolati e attorcigliati attorno ad archi e scalinate protese verso il centro del paese, verso la piazza: un palcoscenico di vita, il luogo dove per secoli le persone hanno mescolato e condiviso storie private e tradizioni della comunità,

Humble rural buildings were the gems of Puglian architecture: a handful of rooms near the barn, a shelter for the animals, storehouses for the crops from the fields and trappeti (underground oil mills). All of this would take shape around the landowner’s manor house, under the once widespread sharecropping system.

Farms of this kind were known as masserie and they were a world of their own: a rural community living in harmony with the climate, light, sun and earth. These aspects played a key part in the development of enchanting architecture featuring white walls, courtyards and whitewashed or limestone vaulted porticoes, as well as watch towers and defensive works for protection against invasions, especially after Turkish attacks in the second half of the 15th century.

Bathed in light and sunshine, the masserie were built with the limestone that was easy to find in Puglian quarries. Dry stone walls known as jazzi stood alongside simply shaped homes. Some of the larger properties had cisterns for collecting water and – from the 18th and 19th centuries onwards – a small church for Sunday Mass.

The courtyard at the centre of each estate served as both a barnyard for the animals and a place for socialising, thus catering to the very human need to be part of a community in a defended, protected environment. It was a place where people baked bread, spun wool, embroidered, mulled over work and told stories. On summer evenings, the sound of traditional peasant folk songs drifted out over the countryside, blending with the chirps of crickets and cicadas.

As well as those who farmed the land in rural areas, there were people who lived in medieval villages: another white world, with whitewashed walls and narrow alleys to provide protection from the sun. They were wrapped around arches and steps stretching towards the piazza at the centre of the village: a stage in the theatre of life, where for centuries people gathered and shared private stories and community traditions, now remembered during celebrations in costume and folk festivals. No fewer than 13 of the most beautiful villages in Italy selected by the “Borghi Più Belli d’Italia” association are in Puglia. Trulli capital Alberobello CONTINUA >

Qui si cuoceva il pane, si filava la lana, si ricamava, si macinavano lavoro e storie

It was a place where people baked bread, spun wool, embroidered, mulled over work and told stories

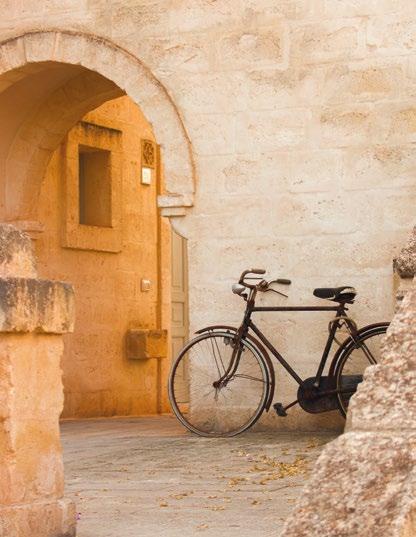

Pagina accanto, scorci poetici di Borgo Egnazia: archi, camini, l’orologio in Piazza e, per spostarsi, le biciclette.

On the opposite page, poetic glimpses of Borgo Egnazia: arches, chimneys, the clock in the Piazza and bicycles to get around.

ricordate oggi da feste in costume e sagre popolari. Fra i borghi più belli d’Italia, ben tredici sono pugliesi, e Alberobello, la capitale dei trulli, nel 1996 è stata dichiarata sito Unesco. È il fascino della storia modellata sui bisogni di una comunità: le case dalla pianta rotonda sono in pietra calcarea, raccolta nei campi e aggregata senza malta, come avveniva per muri a secco di campagna; il tetto conico dipinto di bianco veniva spesso chiuso da un elemento decorativo esoterico, considerato un porta fortuna.

Che si tratti di borghi o masserie, quella Puglia contadina, simbolo del legame tra l’uomo e la terra, è diventata un modello da imitare per molti hotel immersi nella natura. A Borgo Egnazia, la famiglia Melpignano ha saputo osare e si è spinta molto oltre. Anziché riprodurre filologicamente una copia del passato, grazie alla regia magistrale di Pino Brescia, pugliese doc, ha creato dal nulla una realtà che non è né un hotel, né un borgo, né una masseria, ma tutte queste cose insieme. È grazie al frutto di una lunga ricerca se questo luogo pluripremiato riesce ad esprimere un bisogno di bellezza che affonda le radici nella tradizione più vera, senza cadere nei cliché e trasportandola nella contemporaneità.

Dove fino a non molti anni fa c’era solo un campo vuoto coltivato a ortaggi, lentamente hanno preso forma le tre anime del progetto di Borgo Egnazia. L’edificio principale chiamato La Corte – lo spazio dell’accoglienza, dove arrivano gli ospiti – è un chiaro omaggio alle masserie: un mondo di tufo raccolto attorno al grande atrio centrale, che accoglie la reception con i divani e i camini per riscaldarsi nelle giornate più fredde, esattamente come avveniva in campagna, quando i contadini portavano in uno spazio analogo

Ogni dettaglio è ispirato ai materiali, alle forme e ai colori di un tipico paese pugliese.

Every detail is inspired by the materials, shapes and colours of a typical Puglian village.

was named a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1996. It embodies fascinating history shaped around a community’s needs. The round houses were made of limestone found in the fields and put together without mortar, like dry stone walls in the countryside. The conical roofs were painted white and often sealed at the top with an esoteric decorative piece that was thought to bring good luck.

The villages and farms of rustic Puglia symbolised the bond between people and the land and established a model that inspired many hotels in natural surroundings. At Borgo Egnazia, the Melpignano family made the bold choice to take things to a whole new level. Instead of slavishly producing a carbon copy of the past, under the masterful supervision of born and bred Puglian Pino Brescia, out of nothing they created something that is not a hotel, a village or a masseria, but all of these things at the same time. It’s thanks to extensive research that this multi-award-winning place satisfies a need for beauty built on genuine traditions, adding a contemporary touch and steering clear of all clichés.

Where not many years ago there was nothing but an empty field with vegetables growing in it, the three cornerstones of Borgo Egnazia have slowly taken shape. Known as La Corte, the main building where guests are greeted upon their arrival clearly pays tribute to old countryside houses. An abundance of limestone lines a large central lobby containing a reception with sofas and fireplaces where guests can warm up on cold days, just like the farmers who would bring the day’s harvest into a similar space and rest after a hard day’s work. As in the rest of the Borgo, in La Corte an intimate atmosphere is created by soft lights hidden in stones and

il raccolto del giorno, e riposavano dopo una giornata di lavoro. Sempre lì, nella Corte (e in generale in tutto il Borgo), le luci nascoste nelle pietre e nelle caditoie – i piccoli balconi forati che nelle masserie servivano per versare olio bollente sul nemico in caso d’attacco – dispensano atmosfere intime e soffuse. Ma c’è di più: accanto a quegli spazi di pietra chiara si incrociano idealmente i quattro elementi, appena intuiti e filtrati dal design contemporaneo che arreda elegantemente gli spazi. L’aria qui viene interpretata come l’occasione di vivere una nuova esperienza, simboleggiata dalla barriera fisica dell’arco, oltre il quale le macchine non possono proseguire. La reception è la terra: ci sono sacchi con semi, noci, mandorle, limoni… Il grande albero centrale, con le pagine dei libri al posto delle foglie, simboleggia il fuoco perché lì filtra dall’esterno la luce solare. Infine, l’acqua: quella delle piscine collegate al bar e al primo dei ristoranti, sotto un porticato che ricorda quello delle masserie dove le donne potevano lavorare proteggendosi dal sole.

I dettagli della storia ritornano nelle novantadue Casette del Borgo, ispirato a quello dei contadini, con le mura spesse in tufo, i pavimenti in pietra locale e le finestre piccole, per proteggersi dal caldo in estate e trattenere il calore in inverno. Hanno tutte le camere al primo piano, diverse e mai troppo grandi, come vuole la tradizione pugliese. Attorno, vicoli volutamente non ordinati, di dimensioni e pendenze diverse, conducono alla Piazza, che nel passato era un luogo di festa e d’incontro. Gli ospiti di Borgo Egnazia vi si intrattengono con aperitivi, cene e feste all’aperto sotto alla torre dell’orologio (l’unico segnatempo della struttura), che nei villaggi del passato scandiva le ore del riposo e del lavoro, mentre qui batte con discrezione lo scorrere felice del tempo.

L’omaggio alle forme architettoniche della storia è presente anche nelle Case, ispirate questa volta non alle masserie o alle dimore rurali, ma alle ville di vacanza dei ricchi proprietari terrieri. Abbracciate da giardini, patii, terrazze in tufo, hanno interni classici ed eleganti. E sono pensate per fare vivere agli ospiti le atmosfere di una vera casa.

box-machicolations – small balconies with holes in the bottom through which boiling oil could be poured onto attacking enemies. In addition, alongside these light stone spaces, subtle nods to the four elements shine through in the sophisticated, contemporary interior design scheme. Air is interpreted as a chance to enjoy a new experience and symbolised by the physical barrier formed by the arch, beyond which cars cannot go. With its bags of seeds, walnuts, almonds, lemons and more, the reception represents earth. There are pages from books instead of leaves on the large tree in the centre, which filters sunlight from outside and is thus a symbol of fire. Finally, there’s water: in the pools by the bar and the first of the restaurants, under a portico like at a masseria, where women could seek shelter from the sunshine as they worked.

Yet more historical details can be found in the Borgo’s 92 Casette, which are inspired by peasants’ homes with thick limestone walls, local stone flooring and small windows to keep heat out in the summer and keep it in during the winter. All of the rooms are on the first floor. They’re all different and not too big, in keeping with Puglian tradition. There’s a deliberate lack of uniformity in the narrow streets – with varying gradients and sizes – leading to the Piazza, which was a place for gatherings and celebrations in the past. Borgo Egnazia’s guests go there to enjoy outdoor aperitivi, dinners and parties under the clock tower (the only timekeeper in the whole place). In villages in the past, structures like this told people when to work and rest. Here, it discreetly marks time passing happily.

Tributes to historic architecture can also be found in the Case. Rather than masserie or rural dwellings, they’re inspired by the holiday villas of rich landowners. Surrounded by gardens, patios and limestone terraces, they have classic, refined interiors. And they’re designed to make guests feel like they’re in a real home.

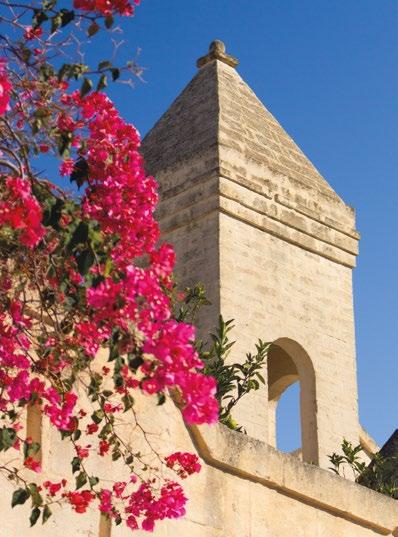

Nella pagina accanto, buganvillee, fichi d’India e altre piante mediterranee tra le Case del Borgo.

On the opposite page, bougainvillea, prickly pears and other Mediterranean plants among the Case in the Borgo.

Gli ospiti si ritrovano in Piazza per aperitivi, cene e feste all'aperto, sotto la torre dell'orologio, l'unico segnatempo del Borgo

Guests go to the Piazza to enjoy outdoor aperitivi, dinners and parties under the clock tower. It is the only timekeeper in the whole place

Go with the Wind

¬ Roberta GenghiMODELLA IL TERRITORIO, INFLUENZA LA PESCA E IL VINO, FORGIA IL CARATTERE E INDICA

DIPENDE SE TIRA SCIROCCO O MAESTRALE

It shapes the land, has an impact on wine and fishing, moulds people’s characters and dictates where the best seaside spots are, depending on whether it’s the Sirocco or the Mistral

«Hai sentito mamma?». In quei giorni noi sorelle lo sappiamo già. E lo sappiamo prima ancora di sentirla, nostra madre. Basta affacciarsi al balcone. Probabilmente nostra madre sarà a letto in attesa che l’ennesimo analgesico faccia effetto. I giorni sono quelli gelidi del Maestrale o quelli caldissimi dello Scirocco. In quei giorni, se sei una persona meteoropatica, ti fa male la chèp, la testa. E mia madre lo è. E noi siamo pugliesi. E il vento lo conosciamo bene, perché con il vento nasciamo, cresciamo e moriamo.

Nel cuore del Mediterraneo, circondata quasi interamente dal mare, esposta all’influenza del mare Adriatico e del mar Ionio, con i suoi quasi 900 chilometri di costa, la Puglia è tra le regioni più ventose d’Italia.

Tramontana, Grecale e Maestrale. E poi ancora Scirocco, più raramente Libeccio. Questi – spiega il

“Have you heard from mum?” On those days, my sister and I already know. And we know it before we even hear from our mother. We simply need to pop out onto the balcony. Our mother will probably be in bed waiting for the umpteenth painkiller to kick in. The days in question are the ones when the freezing Mistral or the scorching Sirocco blow. On those days, if you’re meteoropathic then your chèp – your head – will hurt. My mother’s meteoropathic. And we’re Puglian, so we know the wind well because it’s with us from the day we’re born till the day we die.

With nearly 900 km of coastline in the heart of the Mediterranean, Puglia is almost entirely surrounded by the sea and both the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea have an impact on it, so it’s one of the windiest regions in Italy.

As well as the Tramontane, Gregale and Mistral, there’s the Sirocco and – less frequently – the Libeccio. These are

colonnello Vitantonio Laricchia, massima autorità regionale in materia di clima e meteorologia – sono i venti predominanti. I primi tre sono freschi, provengono dai quadranti settentrionali, si spostano lungo la fascia costiera adriatica e proseguono verso il canale d’Otranto. Gli altri arrivano da Sud. In autunno e in primavera c’è lo Scirocco, che soffia sul Mediterraneo con raffiche potenti cariche di umidità. Raramente c’è il Libeccio: si presenta prima come una brezza, per poi rafforzarsi nella mattinata.

Se sei in Puglia in estate, decidi dove andare al mare in base al vento. Arriva dal Nord? Mari mossi o agitati sulla fascia adriatica, quindi si va sullo Ionio dove le coste sono sottovento. Tira Scirocco? Si va sull’Adriatico. Già, è un vero lusso avere due mari!

La presenza dei venti ha da sempre caratterizzato la regione, influenzandone e modellandone il territorio, condizionando la cultura locale, tra miti, leggende e tradizioni le cui tracce sono visibili ancora oggi nel dna pugliese.

È il vento a dare il nome a tanti vini del territorio, Monte del Vento, Vento Bianco, Vento Rosso. Portatore sano di escursioni termiche giorno-notte, contribuisce alla fissazione degli acidi e degli aromi, donando freschezza e aromaticità al vino. Vento significa evitare umidità e muffe. Ed è proprio in base al vento (e al sole) che si decide l’esposizione del filare.

E ancora è il vento che condiziona e influenza la pesca. «Dopo il Garbino (Libeccio, ndr), c’è il Maestrale fino: lo diceva sempre nonno Mimì (quello del famoso Trabucco da Mimì, a Peschici)», racconta il nipote Vincenzo. «Come ogni movimento del mare, il vento eccita i pesci. Ecco perché prima e dopo la tempesta si pesca bene».

I venti pugliesi raccontano tanto di chi siamo: sognatori, romantici, allegri, ospitali, e poi ancora orgogliosi, ipercritici, testardi, passionali, un po’ folli e un po’ geniali all’occorrenza.

Penso ad Angelo, il protagonista di Monteruga, il primo romanzo di Anna Puricella, a cui lo Scirocco toglie il sentimento e il respiro. «In dialetto salentino lo chiamano faùgnu», spiega la scrittrice. «È fastidioso, si appiccica alla pelle e fa sragionare».

«Quando c’è Scirocco le cose funzionano male, anche i pensieri si attaccano addosso, come sanguisughe», canta Paolo Benincasa. Mentre Mapi, che di mestiere fa la traduttrice, quando sbaglia le parole in un discorso o le scandisce male dice: «Oggi è Scirocco». Parla invece di un amico quando evoca il Maestrale. Amico perché spinge lontano le perturbazioni e porta ampie schiarite. È lui il vento forte del cambiamento: all’inizio la burrasca ci fa paura, ma in fondo lo sappiamo che andrà tutto bene.

the prevailing winds, explains Colonel Vitantonio Laricchia, the region’s leading climate and meteorology expert. The first three are cold and they come from a northerly direction, moving down the Adriatic coast and continuing towards the Strait of Otranto. The other winds come from the South. In autumn and spring there’s the Sirocco, which sends powerful gusts full of moisture over the Mediterranean. On the rare occasions when the Libeccio blows, it starts out as a breeze and then gets stronger over the course of the morning.

During the Puglian summer, you need to consider the wind when deciding where to spend a day by the sea. If it’s coming from the North, the Adriatic will be rough or choppy so the sheltered Ionian coast is the best bet. If the Sirocco’s blowing, head to the Adriatic. Having a choice of two different seas is a real luxury!

The various winds have always played a big part in the region. They have shaped and made their mark on the land and the local culture, giving rise to myths, legends and traditions whose traces can still be seen in the Puglian DNA today.

The Italian word for wind – Vento – appears in the names of many local wines, such as Monte del Vento, Vento Bianco and Vento Rosso. As sommelier, oenologist and blogger Gianpaolo Priore says with a smile, “the wind brings healthy temperature differences between the day and night, helps to firmly establish acids and aromas, and makes wine fresh and aromatic. It can also prevent moisture and mould. When deciding on the aspect of rows of vines, it’s the wind (and sun) that you take into account.”

The wind also has an impact on fishing. “The Garbino (Libeccio – ed.) is followed by a gentle Mistral: that’s what Grandad Mimì (from the famous Trabucco da Mimì in Peschici) always used to say,” reveals Vincenzo. “Like all movement in the sea, the wind stirs up the fish. That’s why the fishing’s good before and after storms.”

The Puglian winds say a lot about who we are: cheerful, hospitable and romantic dreamers, who are proud, hypercritical, headstrong and passionate. When the need arises, we can be a little crazy and a little inspired.

Take Angelo, the protagonist in Monteruga, which is Anna Puricella’s first novel. The Sirocco takes both his breath and his feelings away. “In the dialect of Salento, they call it faùgnu,” explains the writer. “It’s irksome. It sticks to your skin and stops you from thinking rationally.”

“Nothing works properly when the Sirocco blows. Even thoughts cling on like leeches,” sings Paolo Benincasa. Mapi’s an interpreter. When she gets the words in a speech wrong or doesn’t articulate them properly, she says: “The Sirocco’s blowing today.” In contrast, she thinks of the Mistral as a friend because it carries bad weather far away and leads to long sunny spells. It’s a strong wind of change: the gales might be a little scary at first, but deep down we know everything will be OK.

A Little Eden for Ancient Fruits

¬ Luca BergaminCOMPIE TRENT’ANNI IL PROGETTO DEL FOTOGRAFO MILANESE CHE SI È TRASFERITO A CISTERNINO PER PROTEGGERE NEL SUO GIARDINO PIANTE RARE E DIFENDERE LA BIODIVERSITÀ

The project of a Milanese photographer who moved to Cisternino to protect rare plants and defend biodiversity in his gardens turns thirty

Paolo Belloni by Flavio&Frank.

Paolo Belloni e il suo cane Lara formano una coppia inseparabile. Insieme accolgono eminenti professori di botanica, giovani studenti e appassionati di flora nel loro piccolo eden, i Giardini di Pomona, un conservatorio botanico fondato trent’anni fa, nel 1994, immerso tra i milioni di ulivi della Valle d’Itria nella campagna che da Cisternino arriva al Mare Adriatico. Paolo, fotografo milanese con la passione per la natura, ha scelto la Puglia per realizzare il suo progetto: proteggere, e in qualche caso salvare, le piante antiche da frutto per dare un concreto contributo alla biodiversità e trasmetterla alle generazioni future. Una sorta di Arca di Noè vegetale.

Nei dieci ettari dei Giardini di Pomona (il nome è dedicato alla dea pagana dei frutti, ndr) sono state messe a dimora oltre mille specie di alberi da frutto per sottrarle a una quasi sicura estinzione. Tra queste, seicento sono varietà di Ficus carica provenienti dalla Francia, dalla Bosnia, dal Portogallo, dall’Albania e da altri paesi, e insieme formano una delle più importanti collezioni del Mediterraneo. Paolo cura le piante con amore, ne raccoglie i frutti e li trasforma in deliziose conserve. Quando i fichi maturano,

Paolo and his dog, Lara, are an inseparable pair. Together, they welcome eminent botany professors, young students, and flora enthusiasts to their little Eden, the Pomona Gardens, a botanical conservatory founded thirty years ago, in 1994, nestled among the millions of olive trees of the Itria Valley in the countryside that stretches from Cisternino to the Adriatic Sea. Paolo, a Milanese photographer with a passion for nature, chose Puglia to bring his project to life: to protect, and in some cases preserve, ancient fruit plants, make a concrete contribution to biodiversity, and pass it on to future generations. A sort of botanical Noah’s Ark.

In the ten hectares of the Pomona Gardens (the name is inspired by the pagan goddess of fruit, ed.), more than a thousand species of fruit trees have been planted to save them from almost certain extinction. Among them, six hundred are varieties of Ficus carica (fig) from France, Bosnia, Portugal, Albania, and other countries, and together they form one of the most impressive collections in the Mediterranean. Paolo tends his trees with love, harvests the fruit, and turns it into delicious preserves. When the figs ripen, they are cut in half, opened,

vengono tagliati a metà, aperti e lasciati a essiccare su letti di fascine per qualche settimana. Quindi si richiudono inserendo tra le due parti una mandorla e si conservano fino all’inverno per gustarli come dolce ricordo dell’estate.

Scortati dalla scodinzolante Lara, si esplora il parco tra i trulli. Si attraversa l’area dei melograni, quella dei peri e dei meli, con specie rare come la Api Etoilé reintrodotta in Italia proprio grazie al progetto di Pomona. E sono già sbocciate le zagare profumate degli agrumi: limoni, aranci, pompelmi, mandarini, chinotti, esemplari originari della collezione di Cosimo III de’ Medici, e il robusto Poncirus trifoliata, un arancio spinoso che resiste al freddo e si presta agli innesti. La sfida è creare un ponte botanico tra il passato e il futuro, come dimostra il prezioso esemplare di Cachi di Nagasaki, cresciuto da una piantina resiliente che si è salvata dalla devastazione della bomba atomica sganciata dagli americani in Giappone il 9 agosto 1945. Quel cimelio botanico fu recuperato e curato come simbolo di speranza, ed è una grande emozione raggiungerlo al centro di un labirinto di lavanda, come simbolo dello sforzo per ritrovare la pace.

Tutto viene fatto come una volta. Si irriga a mano, si usa il cippato per evitare sprechi di acqua, si costruiscono muretti a secco per proteggere le piante dalla Tramontana. Così, rosmarini, timi, salvie, mente, issopi, artemisie ma anche citronella, ruta, melissa, canfora crescono sani e rigogliosi. L’aria è profumata e i sensi si inebriano.

Ma Paolo è sempre alla ricerca di semi e ramoscelli a cui dare una casa sicura. L’ultima sfida è coltivare i kiwi senza pelo e rendere nuovamente fertili i terreni, introducendo anche piante che richiedono pochissima acqua e resistono alla desertificazione. In questo spicchio di Puglia, tra ciliegi, mandorli, giuggiole ed erbe aromatiche, Paolo sta riuscendo a compiere un’impresa davvero titanica.

and left to dry on the traditional reed drying racks for a few weeks. Then they are closed again, inserting an almond between the two halves, and stored until winter to be enjoyed as a sweet reminder of summer.

Escorted by Lara, happily wagging her tail, visitors can explore the park among the typical Puglian trulli, surrounded by pomegranate, pear, and apple trees, including rare species such as the Api Etoile apple reintroduced to Italy thanks to the Pomona project. The fragrant orange blossoms of citrus fruits have already opened: lemons, oranges, grapefruits, mandarins, and chinottos, specimens that could originally be found in the collection of Cosimo III de' Medici, and the robust Poncirus trifoliata, a thorny orange tree that resists the cold and lends itself to grafting. The challenge is to create a botanical bridge between the past and the future, as shown by the precious specimen of Nagasaki persimmon, grown from a resilient seedling that survived the devastation of the atomic bomb dropped by the Americans in Japan on 9 August 1945. The botanical heirloom was rescued and cared for as a symbol of hope, and it is thrilling to come upon it in the middle of a lavender labyrinth as a symbol of the effort to restore peace.

Everything is done as it used to be. Irrigation is done by hand, wood chips are used to avoid wasting water, and dry-stone walls are built to protect the plants from the cold Tramontane wind. Thus, rosemary, thyme, sage, mint, hyssop, and artemisia, as well as citronella, rue, lemon balm, and camphor, grow healthy and lush. The air is scented, and the senses become inebriated.

But Paolo is always on the lookout for seeds and twigs to give them a safe home. The latest challenge is to cultivate hairless kiwis and make the soil fertile again by introducing plants that require very little water and resist desertification. In this slice of Puglia, among cherry trees, almond trees, jujubes, and aromatic herbs, Paolo is accomplishing a truly epic feat.

Model of Good Tourism

¬ Carmen Rolle ¬ Ph. Giuseppe LanotteTORRE GUACETO È UN MICROCOSMO INCANTEVOLE TRA TERRA E MARE. ENTRARE SI PUÒ, MA SENZA LASCIAR TRACCIA DEL PROPRIO PASSAGGIO. PER OSSERVARE GLI UCCELLI MIGRATORI, NUOTARE TRA I CORALLI E APPLAUDIRE LE TARTARUGHE GUARITE CHE TORNANO IN LIBERTÀ

Torre Guaceto is a mesmerising microcosm nestled between land and sea. You can enter, but gently, leaving no trace of your passage. It's a place to observe migratory birds, swim among coral beds, and applaud healed turtles as they return to freedom

La distesa di ulivi secolari, i canneti mossi dal vento, gli odori della macchia mediterranea. E il mare che si infrange, turchese, su sabbie e falesie dorate. Sono le spiagge di Torre Guaceto, da anni menzionate tra le più belle d’Italia. Fanno parte di un ambiente che è contemporaneamente area marina protetta e riserva naturale terrestre, unico caso insieme a Ventotene. Un sistema riconosciuto anche oltre i confini nazionali: durante l’ultimo Ocean Day, lo scorso 6 marzo 2024, questa area incontaminata tra Brindisi, Carovigno, Mesagne e San Vito dei Normanni si è aggiudicata il prestigioso Mpa Award della Commissione Europea, che premia le migliori aree marine del nostro continente. La tutela, però, non è mai abbastanza. Per conservare l’equilibrio di natura e attività umane è stato avviato il percorso per diventare Riserva della Biosfera Unesco. E da quest’estate, 60 volontari si alternano per una maggiore difesa dell’ambiente e degli animali.

In queste foto, Torre Guaceto, patrimonio Unesco e oasi Wwf.

In these photos, Torre Guaceto, both a Unesco World Heritage Site and a Wwf Oasis.

Amidst centuries-old olive trees, windswept reeds, and the wafting scents of the Mediterranean scrub, the turquoise sea crashes onto golden sands and cliffs. These are the beaches of Torre Guaceto, long hailed as some of Italy’s finest. They form part of an ecosystem that is both a marine protected area and a terrestrial nature reserve, a unique case in Italy along with the island of Ventotene. Internationally recognised, during the 2024 Ocean Days, from 4th to 8th March, this pristine area between Brindisi, Carovigno, Mesagne, and San Vito dei Normanni was given the prestigious MPA Award by the European Commission, celebrating the best marine areas across our continent. However, protection is never enough. So to preserve the balance of nature and human activities, the pathway for this area to become a Unesco Biosphere Reserve has been initiated. Starting this summer, sixty volunteers will be rotating to better defend both the environment and the wildlife.

Oggi la riserva tutela circa 3.000 ettari di territorio, più di 8 chilometri di costa, in un paesaggio che allinea campi coltivati e uliveti, macchia mediterranea e canneti, stagni e dune, scogli e baie sabbiose, con sentieri da percorrere in bici o a piedi, con le guide della Cooperativa Thalassia. Pedalando in silenzio tra aironi, falchi, folaghe e tante altre specie di uccelli migratori e no, si raggiunge la cinquecentesca torre aragonese che dà il nome alla riserva: dentro c’è un’imponente riproduzione di un’antica nave romana che serviva per il trasporto di olio e vino nel Mediterraneo.